User login

What's Your Diagnosis?

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

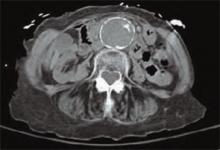

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.