User login

Teaching Effectiveness in HM

Hospital medicine (HM), which is the fastest growing medical specialty in the United States, includes more than 40,000 healthcare providers.[1] Hospitalists include practitioners from a variety of medical specialties, including internal medicine and pediatrics, and professional backgrounds such as physicians, nurse practitioners. and physician assistants.[2, 3] Originally defined as specialists of inpatient medicine, hospitalists must diagnose and manage a wide variety of clinical conditions, coordinate transitions of care, provide perioperative management to surgical patients, and contribute to quality improvement and hospital administration.[4, 5]

With the evolution of the HM, the need for effective continuing medical education (CME) has become increasingly important. Courses make up the largest percentage of CME activity types,[6] which also include regularly scheduled lecture series, internet materials, and journal‐related CME. Successful CME courses require educational content that matches the learning needs of its participants.[7] In 2006, the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) developed core competencies in HM to guide educators in identifying professional practice gaps for useful CME.[8] However, knowing a population's characteristics and learning needs is a key first step to recognizing a practice gap.[9] Understanding these components is important to ensuring that competencies in the field of HM remain relevant to address existing practice gaps.[10] Currently, little is known about the demographic characteristics of participants in HM CME.

Research on the characteristics of effective clinical teachers in medicine has revealed the importance of establishing a positive learning climate, asking questions, diagnosing learners needs, giving feedback, utilizing established teaching frameworks, and developing a personalized philosophy of teaching.[11] Within CME, research has generally demonstrated that courses lead to improvements in lower level outcomes,[12] such as satisfaction and learning, yet higher level outcomes such as behavior change and impacts on patients are inconsistent.[13, 14, 15] Additionally, we have shown that participant reflection on CME is enhanced by presenters who have prior teaching experience and higher teaching effectiveness scores, by the use of audience participation and by incorporating relevant content.[16, 17] Despite the existence of research on CME in general, we are not aware of prior studies regarding characteristics of effective CME in the field of HM.

To better understand and improve the quality of HM CME, we sought to describe the characteristics of participants at a large, national HM CME course, and to identify associations between characteristics of presentations and CME teaching effectiveness (CMETE) scores using a previously validated instrument.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This cross‐sectional study included all participants (n=368) and presenters (n=29) at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Medicine Managing Complex Patients (MCP) course in October 2014. MCP is a CME course designed for hospitalists (defined as those who spend most of their professional practice caring for hospitalized patients) and provides up to 24.5 American Medical Association Physician's Recognition Award category 1 credits. The course took place over 4 days and consisted of 32 didactic presentations, which comprised the context for data collection for this study. The structure of the course day consisted of early and late morning sessions, each made up of 3 to 5 presentations, followed by a question and answer session with presenters and a 15‐minute break. The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Independent Variables: Characteristics of Participants and Presentations

Demographic characteristics of participants were obtained through anonymous surveys attached to CME teaching effectiveness forms. Variables included participant sex, professional degree, self‐identified hospitalist, medical specialty, geographic practice location, age, years in practice/level of training, practice setting, American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, number of CME credits earned, and number of CME programs attended in the past year. These variables were selected in an effort to describe potentially relevant demographics of a national cohort of HM CME participants.

Presentation variables included use of clinical cases, audience response system (ARS), number of slides, defined goals/objectives, summary slide and presentation length in minutes, and are supported by previous CME effectiveness research.[16, 17, 18, 19]

Outcome Variable: CME Teaching Effectiveness Scores

The CMETE scores for this study were obtained from an instrument described in our previous research.[16] The instrument contains 7 items on 5‐point scales (range: strongly disagree to strongly agree) that address speaker clarity and organization, relevant content, use of case examples, effective slides, interactive learning methods (eg, audience response), use of supporting evidence, appropriate amount of content, and summary of key points. Additionally, the instrument includes 2 open‐ended questions: (1) What did the speaker do well? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples) and (2) What could the speaker improve on? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples). Validity evidence for CMETE scores included factor analysis demonstrating a unidimensional model for measuring presenter feedback, along with excellent internal consistency and inter‐rater reliability.[16]

Data Analysis

A CMETE score per presentation from each attendee was calculated as the average over the 7 instrument items. A composite presentation‐level CMETE score was then computed as the average overall score within each presentation. CMETE scores were summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs). The overall CMETE scores were compared by presentation characteristics using Kruskal‐Wallis tests. To illustrate the size of observed differences, Cohen effect sizes are presented as the average difference between groups divided by the common SD. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 32 presentations during the MCP conference in 2014. A total of 277 (75.2%) out of 368 participants completed the survey. This yielded 7947 CMETE evaluations for analysis, with an average of 28.7 per person (median: 31, interquartile range: 2732, range: 632).

Demographic characteristics of course participants are listed in Table 1. Participants (number, %), described themselves as hospitalists (181, 70.4%), ABIM certified with HM focus (48, 18.8%), physicians with MD or MBBS degrees (181, 70.4%), nurse practitioners or physician assistants (52; 20.2%), and in practice 20 years (73, 28%). The majority of participants (148, 58.3%) worked in private practice, whereas only 63 (24.8%) worked in academic settings.

| Variable | No. of Attendees (%), N=277 |

|---|---|

| |

| Sex | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Male | 124 (48.6%) |

| Female | 131 (51.4%) |

| Age | |

| Unknown | 17 |

| 2029 years | 11 (4.2%) |

| 3039 years | 83 (31.9%) |

| 4049 years | 61 (23.5%) |

| 5059 years | 56 (21.5%) |

| 6069 years | 38 (14.6%) |

| 70+ years | 11 (4.2%) |

| Professional degree | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| MD/MBBS | 181 (70.4%) |

| DO | 23 (8.9%) |

| NP | 28 (10.9%) |

| PA | 24 (9.3%) |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Unknown | 26 |

| Internal medicine | 149 (59.4%) |

| Family medicine | 47 (18.7%) |

| IM subspecialty | 14 (5.6%) |

| Other | 41 (16.3%) |

| Geographic location | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Western US | 48 (18.4%) |

| Northeastern US | 33 (12.6%) |

| Midwestern US | 98 (37.5%) |

| Southern US | 40 (15.3%) |

| Canada | 13 (5.0%) |

| Other | 29 (11.1%) |

| Years of practice/training | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Currently in training | 1 (0.4%) |

| Practice 04 years | 68 (26.1%) |

| Practice 59 years | 55 (21.1%) |

| Practice 1019 years | 64 (24.5%) |

| Practice 20+ years | 73 (28.0%) |

| Practice setting | |

| Unknown | 23 |

| Academic | 63 (24.8%) |

| Privateurban | 99 (39.0%) |

| Privaterural | 49 (19.3%) |

| Other | 43 (16.9%) |

| ABIM certification HM | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Yes | 48 (18.8%) |

| No | 207 (81.2%) |

| Hospitalist | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| Yes | 181 (70.4%) |

| No | 76 (29.6%) |

| CME credits claimed | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| 024 | 54 (21.0%) |

| 2549 | 105 (40.9%) |

| 5074 | 61 (23.7%) |

| 7599 | 15 (5.8%) |

| 100+ | 22 (8.6%) |

| CME programs attended | |

| Unknown | 18 |

| 0 | 38 (14.7%) |

| 12 | 166 (64.1%) |

| 35 | 52 (20.1%) |

| 6+ | 3 (1.2%) |

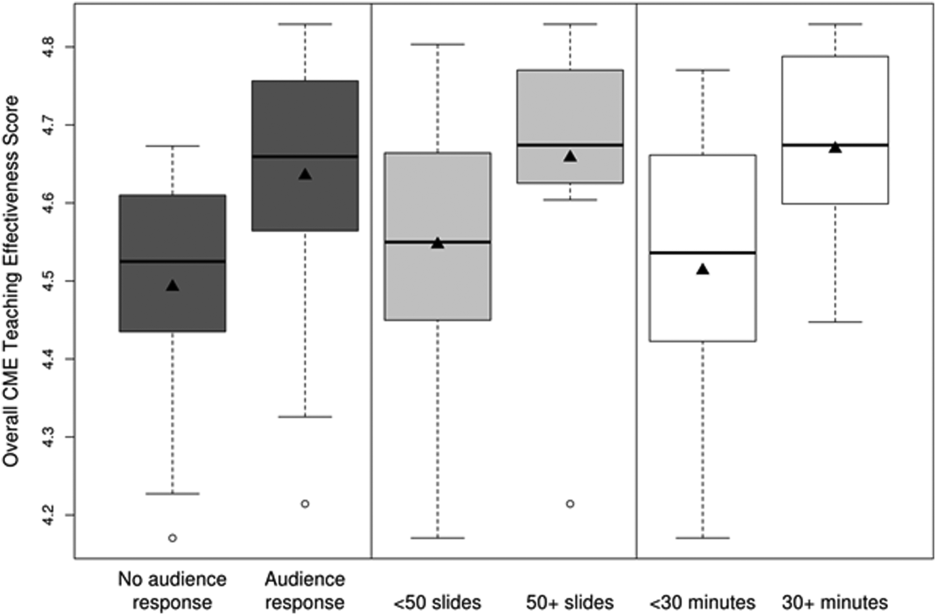

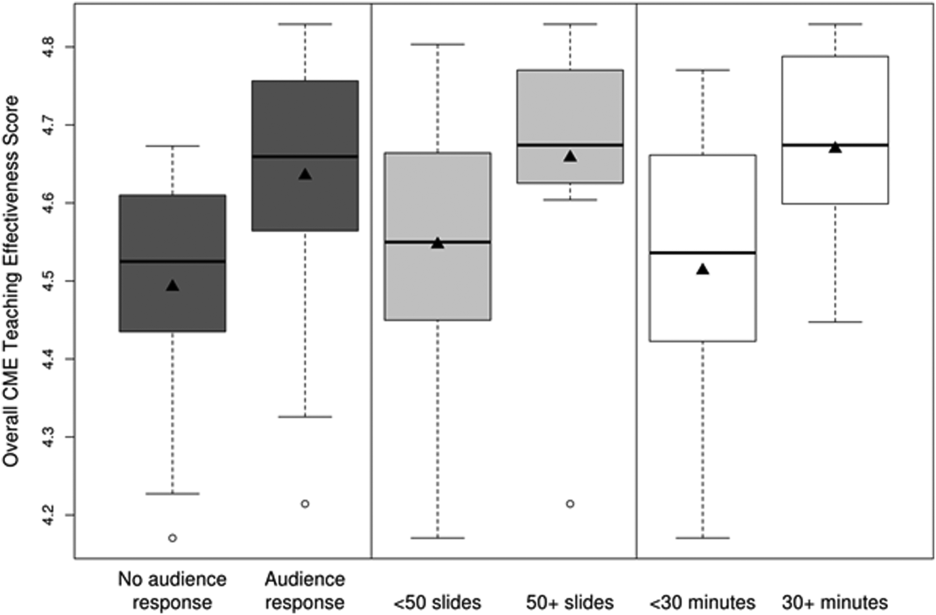

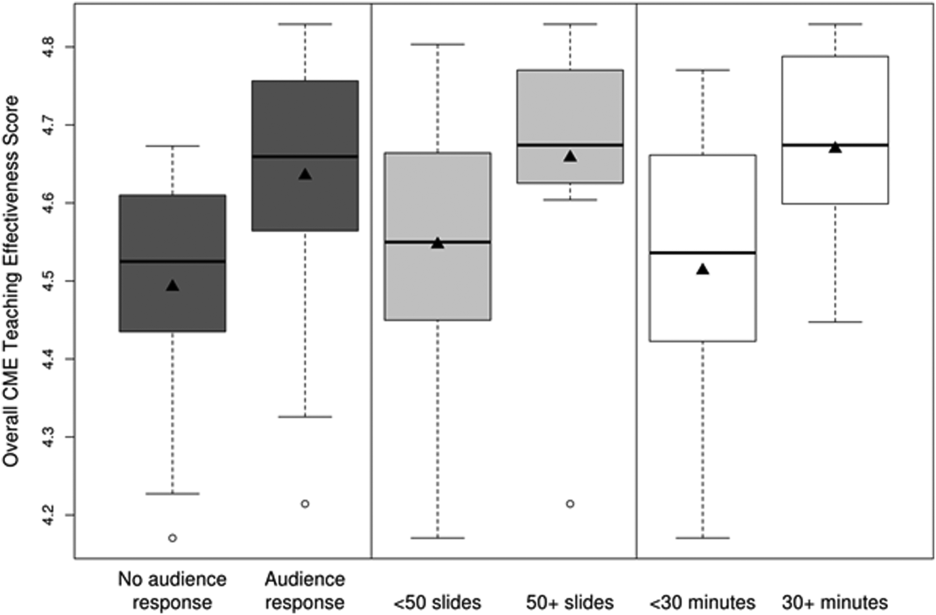

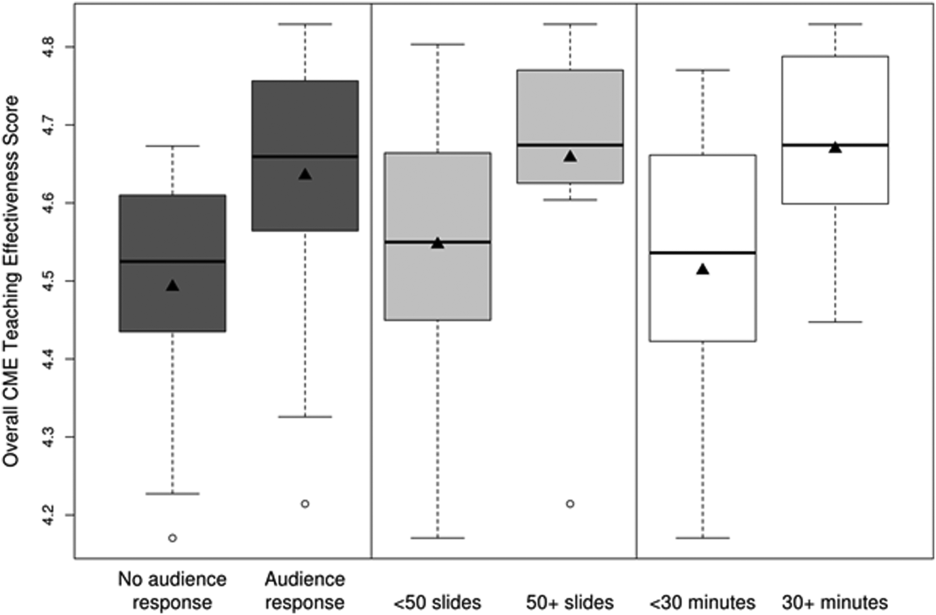

CMETE scores (mean [SD]) were significantly associated with the use of ARS (4.64 [0.16]) vs no ARS (4.49 [0.16]; P=0.01, Table 2, Figure 1), longer presentations (30 minutes: 4.67 [0.13] vs <30 minutes: 4.51 [0.18]; P=0.02), and larger number of slides (50: 4.66 [0.17] vs <50: 4.55 [0.17]; P=0.04). There were no significant associations between CMETE scores and use of clinical cases, defined goals, or summary slides.

| Presentation Variable | No. (%) | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of clinical cases | ||||

| Yes | 28 (87.5%) | 4.60 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| No | 4 (12.5%) | 4.49 | 0.14 | |

| Audience response system | ||||

| Yes | 20 (62.5%) | 4.64 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| No | 12 (37.5%) | 4.49 | 0.16 | |

| No. of slides | ||||

| 50 | 10 (31.3%) | 4.66 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| <50 | 22 (68.8%) | 4.55 | 0.17 | |

| Defined goals/objectives | ||||

| Yes | 29 (90.6%) | 4.58 | 0.18 | 0.87 |

| No | 3 (9.4%) | 4.61 | 0.17 | |

| Summary slide | ||||

| Yes | 22 (68.8%) | 4.56 | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| No | 10 (31.3%) | 4.62 | 0.15 | |

| Presentation length | ||||

| 30 minutes | 14 (43.8%) | 4.67 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| <30 minutes | 18 (56.3%) | 4.51 | 0.18 |

The magnitude of score differences observed in this study are substantial when considered in terms of Cohen's effect sizes. For number of slides, the effect size is 0.65, for audience response the effect size is 0.94, and for presentation length the effect size is approximately 1. According to Cohen, effect sizes of 0.5 to 0.8 are moderate, and effect sizes >0.8 are large. Consequently, the effect sizes of our observed differences are moderate to large.[20, 21]

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure associations between validated teaching effectiveness scores and characteristics of presentations in HM CME. We found that the use of ARS and longer presentations were associated with significantly higher CMETE scores. Our findings have implications for HM CME course directors and presenters as they attempt to develop methods to improve the quality of CME.

CME participants in our study crossed a wide range of ages and experience, which is consistent with national surveys of hospitalists.[22, 23] Interestingly, however, nearly 1 in 3 participants trained in a specialty other than internal medicine. Additionally, the professional degrees of participants were diverse, with 20% of participants having trained as nurse practitioners or physician assistants. These findings are at odds with an early national survey of inpatient practitioners,[22] but consistent with recent literature that the diversity of training backgrounds among hospitalists is increasing as the field of HM evolves.[24] Hospital medicine CME providers will need to be cognizant of these demographic changes as they work to identify practice gaps and apply appropriate educational methods.

The use of an ARS allows for increased participation and engagement among lecture attendees, which in turn promotes active learning.[25, 26, 27] The association of higher teaching scores with the use of ARS is consistent with previous research in other CME settings such as clinical round tables and medical grand rounds.[17, 28] As it pertains to HM specifically, our findings also build upon a recent study by Sehgal et al., which reported on the novel use of bedside CME to enhance interactive learning and discussion among hospitalists, and which was viewed favorably by course participants.[29]

The reasons why longer presentations in our study were linked to higher CMETE scores are not entirely clear, as previous CME research has failed to demonstrate this relationship.[18] One possibility is that course participants prefer learning from presentations that provide granular, content‐rich information. Another possibility may be that characteristics of effective presenters who gave longer presentations and that were not measured in this study, such as presenter experience and expertise, were responsible for the observed increase in CMETE scores. Yet another possibility is that effective presentations were longer due to the use of ARS, which was also associated with better CMETE scores. This explanation may be plausible because the ARS requires additional slides and provides opportunities for audience interaction, which may lengthen the duration of any given presentation.

This study has several limitations. This was a single CME conference sponsored by a large academic medical center, which may limit generalizability, especially to smaller conferences in community settings. However, the audience was large and diverse in terms of participants experiences, practice settings, professional backgrounds, and geographic locations. Furthermore, the demographic characteristics of hospitalists at our course appear very similar to a recently reported national cross‐section of hospitalist groups.[30] Second, this is a cross‐sectional study without a comparison group. Nonetheless, a systematic review showed that most published education research studies involved single‐group designs without comparison groups.[31] Last, the outcomes of the study include attitudes and objectively measured presenter behaviors such as the use of ARS, but not patient‐related outcomes. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that the majority of medical education research does not present outcomes beyond knowledge,[31] and it has been noted that behavior‐related outcomes strike the ideal balance between feasibility and rigor.[32, 33] Finally, the instrument used in this study to measure teaching effectiveness is supported by prior validity evidence.[16]

In summary, we found that hospital medicine CME presentations, which are longer and use audience responses, are associated with greater teaching effectiveness ratings by CME course participants. These findings build upon previous CME research and suggest that CME course directors and presenters should strive to incorporate opportunities that promote audience engagement and participation. Additionally, this study adds to the existing validity of evidence for the CMETE assessment tool. We believe that future research should explore potential associations between teacher effectiveness and patient‐related outcomes, and determine whether course content that reflects the SHM core competencies improves CME teaching effectiveness scores.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013/2014 press kit. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Media_Center/Web/Media_Center/Media_Center.aspx?hkey=e26ceba7-ba93-4e50-8eb1-1ccc75d6f0fd. Accessed May 18, 2015.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist services: an evolving opportunity. Nurse Pract. 2008;33:9–10.

- , , , et al. The evolving role of the pediatric nurse practitioner in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:261–265.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Definition of a hospitalist and hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/About_SHM/Hospitalist_Definition/Web/About_SHM/Industry/Hospital_Medicine_Hospital_Definition.aspx. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. 2013 annual report data executive summary. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/630_2013_Annual_Report_20140715_0.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- . The anatomy of an outstanding CME meeting. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2:534–540.

- , , , , . How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:57–67.

- , , , , , . Perspective: a practical approach to defining professional practice gaps for continuing medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:582–585.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):148–156.

- , . Proposal for a collaborative approach to clinical teaching. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:339–344.

- , . Developing scholarly projects in education: a primer for medical teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29:210–218.

- , . A meta‐analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:6–15.

- , , . Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:1–15.

- , . Effectiveness of continuing medical education: updated synthesis of systematic reviews. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/652_20141104_Effectiveness_of_Continuing_Medical_Education_Cervero_and_Gaines.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2015.

- , , , et al. Improving participant feedback to continuing medical education presenters in internal medicine: a mixed‐methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:425–431.

- , , , et al. Measuring faculty reflection on medical grand rounds at Mayo Clinic: associations with teaching experience, clinical exposure, and presenter effectiveness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:277–284.

- , , , . Successful lecturing: a prospective study to validate attributes of the effective medical lecture. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:366–371.

- , , , , , . A standardized approach to assessing physician expectations and perceptions of continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:173–182.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- , , , . Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:343–349.

- , , , , . Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:28–36.

- , , , et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:615–620.

- , . A primer on audience response systems: current applications and future considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:77.

- , , . Continuing medical education: AMEE education guide no 35. Med Teach. 2008;30:652–666.

- . Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best‐practice tips. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6:9–20.

- , , . Evaluation of an audience response system for the continuing education of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:109–115.

- , , . Bringing continuing medical education to the bedside: the University of California, San Francisco Hospitalist Mini‐College. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:129–134.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2014.

- , , , , , . Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298:1002–1009.

- . Mind the gap: some reasons why medical education research is different from health services research. Med Educ. 2001;35:319–320.

- , . Reflections on experimental research in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:455–464.

Hospital medicine (HM), which is the fastest growing medical specialty in the United States, includes more than 40,000 healthcare providers.[1] Hospitalists include practitioners from a variety of medical specialties, including internal medicine and pediatrics, and professional backgrounds such as physicians, nurse practitioners. and physician assistants.[2, 3] Originally defined as specialists of inpatient medicine, hospitalists must diagnose and manage a wide variety of clinical conditions, coordinate transitions of care, provide perioperative management to surgical patients, and contribute to quality improvement and hospital administration.[4, 5]

With the evolution of the HM, the need for effective continuing medical education (CME) has become increasingly important. Courses make up the largest percentage of CME activity types,[6] which also include regularly scheduled lecture series, internet materials, and journal‐related CME. Successful CME courses require educational content that matches the learning needs of its participants.[7] In 2006, the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) developed core competencies in HM to guide educators in identifying professional practice gaps for useful CME.[8] However, knowing a population's characteristics and learning needs is a key first step to recognizing a practice gap.[9] Understanding these components is important to ensuring that competencies in the field of HM remain relevant to address existing practice gaps.[10] Currently, little is known about the demographic characteristics of participants in HM CME.

Research on the characteristics of effective clinical teachers in medicine has revealed the importance of establishing a positive learning climate, asking questions, diagnosing learners needs, giving feedback, utilizing established teaching frameworks, and developing a personalized philosophy of teaching.[11] Within CME, research has generally demonstrated that courses lead to improvements in lower level outcomes,[12] such as satisfaction and learning, yet higher level outcomes such as behavior change and impacts on patients are inconsistent.[13, 14, 15] Additionally, we have shown that participant reflection on CME is enhanced by presenters who have prior teaching experience and higher teaching effectiveness scores, by the use of audience participation and by incorporating relevant content.[16, 17] Despite the existence of research on CME in general, we are not aware of prior studies regarding characteristics of effective CME in the field of HM.

To better understand and improve the quality of HM CME, we sought to describe the characteristics of participants at a large, national HM CME course, and to identify associations between characteristics of presentations and CME teaching effectiveness (CMETE) scores using a previously validated instrument.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This cross‐sectional study included all participants (n=368) and presenters (n=29) at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Medicine Managing Complex Patients (MCP) course in October 2014. MCP is a CME course designed for hospitalists (defined as those who spend most of their professional practice caring for hospitalized patients) and provides up to 24.5 American Medical Association Physician's Recognition Award category 1 credits. The course took place over 4 days and consisted of 32 didactic presentations, which comprised the context for data collection for this study. The structure of the course day consisted of early and late morning sessions, each made up of 3 to 5 presentations, followed by a question and answer session with presenters and a 15‐minute break. The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Independent Variables: Characteristics of Participants and Presentations

Demographic characteristics of participants were obtained through anonymous surveys attached to CME teaching effectiveness forms. Variables included participant sex, professional degree, self‐identified hospitalist, medical specialty, geographic practice location, age, years in practice/level of training, practice setting, American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, number of CME credits earned, and number of CME programs attended in the past year. These variables were selected in an effort to describe potentially relevant demographics of a national cohort of HM CME participants.

Presentation variables included use of clinical cases, audience response system (ARS), number of slides, defined goals/objectives, summary slide and presentation length in minutes, and are supported by previous CME effectiveness research.[16, 17, 18, 19]

Outcome Variable: CME Teaching Effectiveness Scores

The CMETE scores for this study were obtained from an instrument described in our previous research.[16] The instrument contains 7 items on 5‐point scales (range: strongly disagree to strongly agree) that address speaker clarity and organization, relevant content, use of case examples, effective slides, interactive learning methods (eg, audience response), use of supporting evidence, appropriate amount of content, and summary of key points. Additionally, the instrument includes 2 open‐ended questions: (1) What did the speaker do well? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples) and (2) What could the speaker improve on? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples). Validity evidence for CMETE scores included factor analysis demonstrating a unidimensional model for measuring presenter feedback, along with excellent internal consistency and inter‐rater reliability.[16]

Data Analysis

A CMETE score per presentation from each attendee was calculated as the average over the 7 instrument items. A composite presentation‐level CMETE score was then computed as the average overall score within each presentation. CMETE scores were summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs). The overall CMETE scores were compared by presentation characteristics using Kruskal‐Wallis tests. To illustrate the size of observed differences, Cohen effect sizes are presented as the average difference between groups divided by the common SD. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 32 presentations during the MCP conference in 2014. A total of 277 (75.2%) out of 368 participants completed the survey. This yielded 7947 CMETE evaluations for analysis, with an average of 28.7 per person (median: 31, interquartile range: 2732, range: 632).

Demographic characteristics of course participants are listed in Table 1. Participants (number, %), described themselves as hospitalists (181, 70.4%), ABIM certified with HM focus (48, 18.8%), physicians with MD or MBBS degrees (181, 70.4%), nurse practitioners or physician assistants (52; 20.2%), and in practice 20 years (73, 28%). The majority of participants (148, 58.3%) worked in private practice, whereas only 63 (24.8%) worked in academic settings.

| Variable | No. of Attendees (%), N=277 |

|---|---|

| |

| Sex | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Male | 124 (48.6%) |

| Female | 131 (51.4%) |

| Age | |

| Unknown | 17 |

| 2029 years | 11 (4.2%) |

| 3039 years | 83 (31.9%) |

| 4049 years | 61 (23.5%) |

| 5059 years | 56 (21.5%) |

| 6069 years | 38 (14.6%) |

| 70+ years | 11 (4.2%) |

| Professional degree | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| MD/MBBS | 181 (70.4%) |

| DO | 23 (8.9%) |

| NP | 28 (10.9%) |

| PA | 24 (9.3%) |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Unknown | 26 |

| Internal medicine | 149 (59.4%) |

| Family medicine | 47 (18.7%) |

| IM subspecialty | 14 (5.6%) |

| Other | 41 (16.3%) |

| Geographic location | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Western US | 48 (18.4%) |

| Northeastern US | 33 (12.6%) |

| Midwestern US | 98 (37.5%) |

| Southern US | 40 (15.3%) |

| Canada | 13 (5.0%) |

| Other | 29 (11.1%) |

| Years of practice/training | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Currently in training | 1 (0.4%) |

| Practice 04 years | 68 (26.1%) |

| Practice 59 years | 55 (21.1%) |

| Practice 1019 years | 64 (24.5%) |

| Practice 20+ years | 73 (28.0%) |

| Practice setting | |

| Unknown | 23 |

| Academic | 63 (24.8%) |

| Privateurban | 99 (39.0%) |

| Privaterural | 49 (19.3%) |

| Other | 43 (16.9%) |

| ABIM certification HM | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Yes | 48 (18.8%) |

| No | 207 (81.2%) |

| Hospitalist | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| Yes | 181 (70.4%) |

| No | 76 (29.6%) |

| CME credits claimed | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| 024 | 54 (21.0%) |

| 2549 | 105 (40.9%) |

| 5074 | 61 (23.7%) |

| 7599 | 15 (5.8%) |

| 100+ | 22 (8.6%) |

| CME programs attended | |

| Unknown | 18 |

| 0 | 38 (14.7%) |

| 12 | 166 (64.1%) |

| 35 | 52 (20.1%) |

| 6+ | 3 (1.2%) |

CMETE scores (mean [SD]) were significantly associated with the use of ARS (4.64 [0.16]) vs no ARS (4.49 [0.16]; P=0.01, Table 2, Figure 1), longer presentations (30 minutes: 4.67 [0.13] vs <30 minutes: 4.51 [0.18]; P=0.02), and larger number of slides (50: 4.66 [0.17] vs <50: 4.55 [0.17]; P=0.04). There were no significant associations between CMETE scores and use of clinical cases, defined goals, or summary slides.

| Presentation Variable | No. (%) | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of clinical cases | ||||

| Yes | 28 (87.5%) | 4.60 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| No | 4 (12.5%) | 4.49 | 0.14 | |

| Audience response system | ||||

| Yes | 20 (62.5%) | 4.64 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| No | 12 (37.5%) | 4.49 | 0.16 | |

| No. of slides | ||||

| 50 | 10 (31.3%) | 4.66 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| <50 | 22 (68.8%) | 4.55 | 0.17 | |

| Defined goals/objectives | ||||

| Yes | 29 (90.6%) | 4.58 | 0.18 | 0.87 |

| No | 3 (9.4%) | 4.61 | 0.17 | |

| Summary slide | ||||

| Yes | 22 (68.8%) | 4.56 | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| No | 10 (31.3%) | 4.62 | 0.15 | |

| Presentation length | ||||

| 30 minutes | 14 (43.8%) | 4.67 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| <30 minutes | 18 (56.3%) | 4.51 | 0.18 |

The magnitude of score differences observed in this study are substantial when considered in terms of Cohen's effect sizes. For number of slides, the effect size is 0.65, for audience response the effect size is 0.94, and for presentation length the effect size is approximately 1. According to Cohen, effect sizes of 0.5 to 0.8 are moderate, and effect sizes >0.8 are large. Consequently, the effect sizes of our observed differences are moderate to large.[20, 21]

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure associations between validated teaching effectiveness scores and characteristics of presentations in HM CME. We found that the use of ARS and longer presentations were associated with significantly higher CMETE scores. Our findings have implications for HM CME course directors and presenters as they attempt to develop methods to improve the quality of CME.

CME participants in our study crossed a wide range of ages and experience, which is consistent with national surveys of hospitalists.[22, 23] Interestingly, however, nearly 1 in 3 participants trained in a specialty other than internal medicine. Additionally, the professional degrees of participants were diverse, with 20% of participants having trained as nurse practitioners or physician assistants. These findings are at odds with an early national survey of inpatient practitioners,[22] but consistent with recent literature that the diversity of training backgrounds among hospitalists is increasing as the field of HM evolves.[24] Hospital medicine CME providers will need to be cognizant of these demographic changes as they work to identify practice gaps and apply appropriate educational methods.

The use of an ARS allows for increased participation and engagement among lecture attendees, which in turn promotes active learning.[25, 26, 27] The association of higher teaching scores with the use of ARS is consistent with previous research in other CME settings such as clinical round tables and medical grand rounds.[17, 28] As it pertains to HM specifically, our findings also build upon a recent study by Sehgal et al., which reported on the novel use of bedside CME to enhance interactive learning and discussion among hospitalists, and which was viewed favorably by course participants.[29]

The reasons why longer presentations in our study were linked to higher CMETE scores are not entirely clear, as previous CME research has failed to demonstrate this relationship.[18] One possibility is that course participants prefer learning from presentations that provide granular, content‐rich information. Another possibility may be that characteristics of effective presenters who gave longer presentations and that were not measured in this study, such as presenter experience and expertise, were responsible for the observed increase in CMETE scores. Yet another possibility is that effective presentations were longer due to the use of ARS, which was also associated with better CMETE scores. This explanation may be plausible because the ARS requires additional slides and provides opportunities for audience interaction, which may lengthen the duration of any given presentation.

This study has several limitations. This was a single CME conference sponsored by a large academic medical center, which may limit generalizability, especially to smaller conferences in community settings. However, the audience was large and diverse in terms of participants experiences, practice settings, professional backgrounds, and geographic locations. Furthermore, the demographic characteristics of hospitalists at our course appear very similar to a recently reported national cross‐section of hospitalist groups.[30] Second, this is a cross‐sectional study without a comparison group. Nonetheless, a systematic review showed that most published education research studies involved single‐group designs without comparison groups.[31] Last, the outcomes of the study include attitudes and objectively measured presenter behaviors such as the use of ARS, but not patient‐related outcomes. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that the majority of medical education research does not present outcomes beyond knowledge,[31] and it has been noted that behavior‐related outcomes strike the ideal balance between feasibility and rigor.[32, 33] Finally, the instrument used in this study to measure teaching effectiveness is supported by prior validity evidence.[16]

In summary, we found that hospital medicine CME presentations, which are longer and use audience responses, are associated with greater teaching effectiveness ratings by CME course participants. These findings build upon previous CME research and suggest that CME course directors and presenters should strive to incorporate opportunities that promote audience engagement and participation. Additionally, this study adds to the existing validity of evidence for the CMETE assessment tool. We believe that future research should explore potential associations between teacher effectiveness and patient‐related outcomes, and determine whether course content that reflects the SHM core competencies improves CME teaching effectiveness scores.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Hospital medicine (HM), which is the fastest growing medical specialty in the United States, includes more than 40,000 healthcare providers.[1] Hospitalists include practitioners from a variety of medical specialties, including internal medicine and pediatrics, and professional backgrounds such as physicians, nurse practitioners. and physician assistants.[2, 3] Originally defined as specialists of inpatient medicine, hospitalists must diagnose and manage a wide variety of clinical conditions, coordinate transitions of care, provide perioperative management to surgical patients, and contribute to quality improvement and hospital administration.[4, 5]

With the evolution of the HM, the need for effective continuing medical education (CME) has become increasingly important. Courses make up the largest percentage of CME activity types,[6] which also include regularly scheduled lecture series, internet materials, and journal‐related CME. Successful CME courses require educational content that matches the learning needs of its participants.[7] In 2006, the Society for Hospital Medicine (SHM) developed core competencies in HM to guide educators in identifying professional practice gaps for useful CME.[8] However, knowing a population's characteristics and learning needs is a key first step to recognizing a practice gap.[9] Understanding these components is important to ensuring that competencies in the field of HM remain relevant to address existing practice gaps.[10] Currently, little is known about the demographic characteristics of participants in HM CME.

Research on the characteristics of effective clinical teachers in medicine has revealed the importance of establishing a positive learning climate, asking questions, diagnosing learners needs, giving feedback, utilizing established teaching frameworks, and developing a personalized philosophy of teaching.[11] Within CME, research has generally demonstrated that courses lead to improvements in lower level outcomes,[12] such as satisfaction and learning, yet higher level outcomes such as behavior change and impacts on patients are inconsistent.[13, 14, 15] Additionally, we have shown that participant reflection on CME is enhanced by presenters who have prior teaching experience and higher teaching effectiveness scores, by the use of audience participation and by incorporating relevant content.[16, 17] Despite the existence of research on CME in general, we are not aware of prior studies regarding characteristics of effective CME in the field of HM.

To better understand and improve the quality of HM CME, we sought to describe the characteristics of participants at a large, national HM CME course, and to identify associations between characteristics of presentations and CME teaching effectiveness (CMETE) scores using a previously validated instrument.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

This cross‐sectional study included all participants (n=368) and presenters (n=29) at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Medicine Managing Complex Patients (MCP) course in October 2014. MCP is a CME course designed for hospitalists (defined as those who spend most of their professional practice caring for hospitalized patients) and provides up to 24.5 American Medical Association Physician's Recognition Award category 1 credits. The course took place over 4 days and consisted of 32 didactic presentations, which comprised the context for data collection for this study. The structure of the course day consisted of early and late morning sessions, each made up of 3 to 5 presentations, followed by a question and answer session with presenters and a 15‐minute break. The study was deemed exempt by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Independent Variables: Characteristics of Participants and Presentations

Demographic characteristics of participants were obtained through anonymous surveys attached to CME teaching effectiveness forms. Variables included participant sex, professional degree, self‐identified hospitalist, medical specialty, geographic practice location, age, years in practice/level of training, practice setting, American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) certification of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, number of CME credits earned, and number of CME programs attended in the past year. These variables were selected in an effort to describe potentially relevant demographics of a national cohort of HM CME participants.

Presentation variables included use of clinical cases, audience response system (ARS), number of slides, defined goals/objectives, summary slide and presentation length in minutes, and are supported by previous CME effectiveness research.[16, 17, 18, 19]

Outcome Variable: CME Teaching Effectiveness Scores

The CMETE scores for this study were obtained from an instrument described in our previous research.[16] The instrument contains 7 items on 5‐point scales (range: strongly disagree to strongly agree) that address speaker clarity and organization, relevant content, use of case examples, effective slides, interactive learning methods (eg, audience response), use of supporting evidence, appropriate amount of content, and summary of key points. Additionally, the instrument includes 2 open‐ended questions: (1) What did the speaker do well? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples) and (2) What could the speaker improve on? (Please describe specific behaviors and examples). Validity evidence for CMETE scores included factor analysis demonstrating a unidimensional model for measuring presenter feedback, along with excellent internal consistency and inter‐rater reliability.[16]

Data Analysis

A CMETE score per presentation from each attendee was calculated as the average over the 7 instrument items. A composite presentation‐level CMETE score was then computed as the average overall score within each presentation. CMETE scores were summarized using means and standard deviations (SDs). The overall CMETE scores were compared by presentation characteristics using Kruskal‐Wallis tests. To illustrate the size of observed differences, Cohen effect sizes are presented as the average difference between groups divided by the common SD. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 32 presentations during the MCP conference in 2014. A total of 277 (75.2%) out of 368 participants completed the survey. This yielded 7947 CMETE evaluations for analysis, with an average of 28.7 per person (median: 31, interquartile range: 2732, range: 632).

Demographic characteristics of course participants are listed in Table 1. Participants (number, %), described themselves as hospitalists (181, 70.4%), ABIM certified with HM focus (48, 18.8%), physicians with MD or MBBS degrees (181, 70.4%), nurse practitioners or physician assistants (52; 20.2%), and in practice 20 years (73, 28%). The majority of participants (148, 58.3%) worked in private practice, whereas only 63 (24.8%) worked in academic settings.

| Variable | No. of Attendees (%), N=277 |

|---|---|

| |

| Sex | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Male | 124 (48.6%) |

| Female | 131 (51.4%) |

| Age | |

| Unknown | 17 |

| 2029 years | 11 (4.2%) |

| 3039 years | 83 (31.9%) |

| 4049 years | 61 (23.5%) |

| 5059 years | 56 (21.5%) |

| 6069 years | 38 (14.6%) |

| 70+ years | 11 (4.2%) |

| Professional degree | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| MD/MBBS | 181 (70.4%) |

| DO | 23 (8.9%) |

| NP | 28 (10.9%) |

| PA | 24 (9.3%) |

| Other | 1 (0.4%) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Unknown | 26 |

| Internal medicine | 149 (59.4%) |

| Family medicine | 47 (18.7%) |

| IM subspecialty | 14 (5.6%) |

| Other | 41 (16.3%) |

| Geographic location | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Western US | 48 (18.4%) |

| Northeastern US | 33 (12.6%) |

| Midwestern US | 98 (37.5%) |

| Southern US | 40 (15.3%) |

| Canada | 13 (5.0%) |

| Other | 29 (11.1%) |

| Years of practice/training | |

| Unknown | 16 |

| Currently in training | 1 (0.4%) |

| Practice 04 years | 68 (26.1%) |

| Practice 59 years | 55 (21.1%) |

| Practice 1019 years | 64 (24.5%) |

| Practice 20+ years | 73 (28.0%) |

| Practice setting | |

| Unknown | 23 |

| Academic | 63 (24.8%) |

| Privateurban | 99 (39.0%) |

| Privaterural | 49 (19.3%) |

| Other | 43 (16.9%) |

| ABIM certification HM | |

| Unknown | 22 |

| Yes | 48 (18.8%) |

| No | 207 (81.2%) |

| Hospitalist | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| Yes | 181 (70.4%) |

| No | 76 (29.6%) |

| CME credits claimed | |

| Unknown | 20 |

| 024 | 54 (21.0%) |

| 2549 | 105 (40.9%) |

| 5074 | 61 (23.7%) |

| 7599 | 15 (5.8%) |

| 100+ | 22 (8.6%) |

| CME programs attended | |

| Unknown | 18 |

| 0 | 38 (14.7%) |

| 12 | 166 (64.1%) |

| 35 | 52 (20.1%) |

| 6+ | 3 (1.2%) |

CMETE scores (mean [SD]) were significantly associated with the use of ARS (4.64 [0.16]) vs no ARS (4.49 [0.16]; P=0.01, Table 2, Figure 1), longer presentations (30 minutes: 4.67 [0.13] vs <30 minutes: 4.51 [0.18]; P=0.02), and larger number of slides (50: 4.66 [0.17] vs <50: 4.55 [0.17]; P=0.04). There were no significant associations between CMETE scores and use of clinical cases, defined goals, or summary slides.

| Presentation Variable | No. (%) | Mean Score | Standard Deviation | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of clinical cases | ||||

| Yes | 28 (87.5%) | 4.60 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| No | 4 (12.5%) | 4.49 | 0.14 | |

| Audience response system | ||||

| Yes | 20 (62.5%) | 4.64 | 0.16 | 0.01 |

| No | 12 (37.5%) | 4.49 | 0.16 | |

| No. of slides | ||||

| 50 | 10 (31.3%) | 4.66 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| <50 | 22 (68.8%) | 4.55 | 0.17 | |

| Defined goals/objectives | ||||

| Yes | 29 (90.6%) | 4.58 | 0.18 | 0.87 |

| No | 3 (9.4%) | 4.61 | 0.17 | |

| Summary slide | ||||

| Yes | 22 (68.8%) | 4.56 | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| No | 10 (31.3%) | 4.62 | 0.15 | |

| Presentation length | ||||

| 30 minutes | 14 (43.8%) | 4.67 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| <30 minutes | 18 (56.3%) | 4.51 | 0.18 |

The magnitude of score differences observed in this study are substantial when considered in terms of Cohen's effect sizes. For number of slides, the effect size is 0.65, for audience response the effect size is 0.94, and for presentation length the effect size is approximately 1. According to Cohen, effect sizes of 0.5 to 0.8 are moderate, and effect sizes >0.8 are large. Consequently, the effect sizes of our observed differences are moderate to large.[20, 21]

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure associations between validated teaching effectiveness scores and characteristics of presentations in HM CME. We found that the use of ARS and longer presentations were associated with significantly higher CMETE scores. Our findings have implications for HM CME course directors and presenters as they attempt to develop methods to improve the quality of CME.

CME participants in our study crossed a wide range of ages and experience, which is consistent with national surveys of hospitalists.[22, 23] Interestingly, however, nearly 1 in 3 participants trained in a specialty other than internal medicine. Additionally, the professional degrees of participants were diverse, with 20% of participants having trained as nurse practitioners or physician assistants. These findings are at odds with an early national survey of inpatient practitioners,[22] but consistent with recent literature that the diversity of training backgrounds among hospitalists is increasing as the field of HM evolves.[24] Hospital medicine CME providers will need to be cognizant of these demographic changes as they work to identify practice gaps and apply appropriate educational methods.

The use of an ARS allows for increased participation and engagement among lecture attendees, which in turn promotes active learning.[25, 26, 27] The association of higher teaching scores with the use of ARS is consistent with previous research in other CME settings such as clinical round tables and medical grand rounds.[17, 28] As it pertains to HM specifically, our findings also build upon a recent study by Sehgal et al., which reported on the novel use of bedside CME to enhance interactive learning and discussion among hospitalists, and which was viewed favorably by course participants.[29]

The reasons why longer presentations in our study were linked to higher CMETE scores are not entirely clear, as previous CME research has failed to demonstrate this relationship.[18] One possibility is that course participants prefer learning from presentations that provide granular, content‐rich information. Another possibility may be that characteristics of effective presenters who gave longer presentations and that were not measured in this study, such as presenter experience and expertise, were responsible for the observed increase in CMETE scores. Yet another possibility is that effective presentations were longer due to the use of ARS, which was also associated with better CMETE scores. This explanation may be plausible because the ARS requires additional slides and provides opportunities for audience interaction, which may lengthen the duration of any given presentation.

This study has several limitations. This was a single CME conference sponsored by a large academic medical center, which may limit generalizability, especially to smaller conferences in community settings. However, the audience was large and diverse in terms of participants experiences, practice settings, professional backgrounds, and geographic locations. Furthermore, the demographic characteristics of hospitalists at our course appear very similar to a recently reported national cross‐section of hospitalist groups.[30] Second, this is a cross‐sectional study without a comparison group. Nonetheless, a systematic review showed that most published education research studies involved single‐group designs without comparison groups.[31] Last, the outcomes of the study include attitudes and objectively measured presenter behaviors such as the use of ARS, but not patient‐related outcomes. Nonetheless, evidence indicates that the majority of medical education research does not present outcomes beyond knowledge,[31] and it has been noted that behavior‐related outcomes strike the ideal balance between feasibility and rigor.[32, 33] Finally, the instrument used in this study to measure teaching effectiveness is supported by prior validity evidence.[16]

In summary, we found that hospital medicine CME presentations, which are longer and use audience responses, are associated with greater teaching effectiveness ratings by CME course participants. These findings build upon previous CME research and suggest that CME course directors and presenters should strive to incorporate opportunities that promote audience engagement and participation. Additionally, this study adds to the existing validity of evidence for the CMETE assessment tool. We believe that future research should explore potential associations between teacher effectiveness and patient‐related outcomes, and determine whether course content that reflects the SHM core competencies improves CME teaching effectiveness scores.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013/2014 press kit. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Media_Center/Web/Media_Center/Media_Center.aspx?hkey=e26ceba7-ba93-4e50-8eb1-1ccc75d6f0fd. Accessed May 18, 2015.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist services: an evolving opportunity. Nurse Pract. 2008;33:9–10.

- , , , et al. The evolving role of the pediatric nurse practitioner in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:261–265.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Definition of a hospitalist and hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/About_SHM/Hospitalist_Definition/Web/About_SHM/Industry/Hospital_Medicine_Hospital_Definition.aspx. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. 2013 annual report data executive summary. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/630_2013_Annual_Report_20140715_0.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- . The anatomy of an outstanding CME meeting. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2:534–540.

- , , , , . How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:57–67.

- , , , , , . Perspective: a practical approach to defining professional practice gaps for continuing medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:582–585.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):148–156.

- , . Proposal for a collaborative approach to clinical teaching. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:339–344.

- , . Developing scholarly projects in education: a primer for medical teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29:210–218.

- , . A meta‐analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:6–15.

- , , . Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:1–15.

- , . Effectiveness of continuing medical education: updated synthesis of systematic reviews. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/652_20141104_Effectiveness_of_Continuing_Medical_Education_Cervero_and_Gaines.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2015.

- , , , et al. Improving participant feedback to continuing medical education presenters in internal medicine: a mixed‐methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:425–431.

- , , , et al. Measuring faculty reflection on medical grand rounds at Mayo Clinic: associations with teaching experience, clinical exposure, and presenter effectiveness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:277–284.

- , , , . Successful lecturing: a prospective study to validate attributes of the effective medical lecture. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:366–371.

- , , , , , . A standardized approach to assessing physician expectations and perceptions of continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:173–182.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- , , , . Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:343–349.

- , , , , . Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:28–36.

- , , , et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:615–620.

- , . A primer on audience response systems: current applications and future considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:77.

- , , . Continuing medical education: AMEE education guide no 35. Med Teach. 2008;30:652–666.

- . Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best‐practice tips. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6:9–20.

- , , . Evaluation of an audience response system for the continuing education of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:109–115.

- , , . Bringing continuing medical education to the bedside: the University of California, San Francisco Hospitalist Mini‐College. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:129–134.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2014.

- , , , , , . Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298:1002–1009.

- . Mind the gap: some reasons why medical education research is different from health services research. Med Educ. 2001;35:319–320.

- , . Reflections on experimental research in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:455–464.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013/2014 press kit. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Media_Center/Web/Media_Center/Media_Center.aspx?hkey=e26ceba7-ba93-4e50-8eb1-1ccc75d6f0fd. Accessed May 18, 2015.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist services: an evolving opportunity. Nurse Pract. 2008;33:9–10.

- , , , et al. The evolving role of the pediatric nurse practitioner in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:261–265.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Definition of a hospitalist and hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/About_SHM/Hospitalist_Definition/Web/About_SHM/Industry/Hospital_Medicine_Hospital_Definition.aspx. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. 2013 annual report data executive summary. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/630_2013_Annual_Report_20140715_0.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2015.

- . The anatomy of an outstanding CME meeting. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2:534–540.

- , , , , . How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: a framework for curriculum development. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:57–67.

- , , , , , . Perspective: a practical approach to defining professional practice gaps for continuing medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87:582–585.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(suppl 1):148–156.

- , . Proposal for a collaborative approach to clinical teaching. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:339–344.

- , . Developing scholarly projects in education: a primer for medical teachers. Med Teach. 2007;29:210–218.

- , . A meta‐analysis of continuing medical education effectiveness. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:6–15.

- , , . Achieving desired results and improved outcomes: integrating planning and assessment throughout learning activities. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29:1–15.

- , . Effectiveness of continuing medical education: updated synthesis of systematic reviews. Available at: http://www.accme.org/sites/default/files/652_20141104_Effectiveness_of_Continuing_Medical_Education_Cervero_and_Gaines.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2015.

- , , , et al. Improving participant feedback to continuing medical education presenters in internal medicine: a mixed‐methods study. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:425–431.

- , , , et al. Measuring faculty reflection on medical grand rounds at Mayo Clinic: associations with teaching experience, clinical exposure, and presenter effectiveness. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:277–284.

- , , , . Successful lecturing: a prospective study to validate attributes of the effective medical lecture. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:366–371.

- , , , , , . A standardized approach to assessing physician expectations and perceptions of continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2007;27:173–182.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1977.

- . Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- , , , . Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:343–349.

- , , , , . Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:28–36.

- , , , et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:615–620.

- , . A primer on audience response systems: current applications and future considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:77.

- , , . Continuing medical education: AMEE education guide no 35. Med Teach. 2008;30:652–666.

- . Clickers in the large classroom: current research and best‐practice tips. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2007;6:9–20.

- , , . Evaluation of an audience response system for the continuing education of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:109–115.

- , , . Bringing continuing medical education to the bedside: the University of California, San Francisco Hospitalist Mini‐College. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:129–134.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2014.

- , , , , , . Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298:1002–1009.

- . Mind the gap: some reasons why medical education research is different from health services research. Med Educ. 2001;35:319–320.

- , . Reflections on experimental research in medical education. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2010;15:455–464.

© 2015 Society of Hospital Medicine

What's Your Diagnosis?

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.

An 84-year-old white female, a former smoker with a medical history significant for coronary artery disease, chronic renal insufficiency, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, presented to our hospital with two weeks of progressively worsening lower-back pain.

A detailed review of systems was negative for other symptoms. The patient was normotensive with stable vital signs. A physical examination found a 4 cm nontender, pulsatile mass above umbilicus, but a neurovascular exam of her lower extremities was normal. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated serum creatinine of 4.8 mg/dL (0.8-1.2 mg/dL). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast was performed. (See figure 1, below). TH

What should be your next appropriate

a) Obtain additional imaging studies

b) Initiate intravenous beta-blocker therapy to keep systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg

c) Initiate intravenous heparin therapy

d) Observation

e) Perform surgery emergently

Discussion

The answer is “d”: Observation. A CT scan of the abdomen without contrast shows a calcified abdominal aorta with aneurysmal dilatation measuring 4.4 cm in greatest diameter. No dissection or aneurysmal rupture is seen.

The abdominal aorta is the most common site for an arterial aneurysm, occurring below the origin of renal vessels in majority of cases. A diameter greater than 3.0 cm is considered aneurysmal.1 The prevalence increases markedly in individuals older than 60.2 Known risk factors include age, smoking, gender, atherosclerosis, hypertension, and family history of abdominal aneurysm.

The vast majority of the individuals with abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. Abdominal or back pain is the most common complain in symptomatic patients. Often, patients have a ruptured aneurysm on presentation, along with pain in the abdomen, back or groin, hypotension with a tender, pulsatile abdominal mass seen on physical examination. In addition to history and examination, several imaging modalities are utilized for diagnosis. Most aneurysms are picked up incidentally on imaging studies performed for other purposes. Abdominal ultrasonography, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance angiography and angiography are all used for diagnosis.

The size of the aneurysm is important when making management decisions. Risk of rupture increases dramatically for aneurysm diameter greater than 5-5.5 cm.3 Elective repair is generally indicated for asymptomatic aneurysms this size because mortality for emergency repair in case of rupture is extremely high. For asymptomatic aneurysms between 3.0-5.5 cm in diameter, the choice between surgery and surveillance depends on the patient’s preference, co-morbidities, presence of risk factors and the risk of surgery. For surveillance, monitor with ultrasound or CT scan every six to 24 months.1 Smoking cessation and treatment of hypertension and hyperlipidemia are important in medical management. Surgical repair is done either by the traditional transabdominal route or retroperitoneal approach. Endovascular stent grafts have also been introduced more recently. Symptomatic aneurysms require repair, regardless of the diameter.

Our patient had several risk factors, including age, smoking, hypertension, and atherosclerosis for developing an abdominal aortic aneurysm. After discussion of findings and management options, patient did not elect to undergo surgical repair. Smoking cessation, continued medical therapy for risk factors and surveillance was advised on discharge. TH

Drs. Aijaz and Newman practice at the Department of Medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medical Education, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

References

- Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006 Mar 21;113(11):e463-654.

- Singh K, Bønaa KH, Jacobsen BK, Bjørk L, Solberg S. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 1;154(3): 236-244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 8;348(19):1895-1901.

The Hospital as College

The hospital is the only proper college in which to rear a true disciple of Aesculapius.—John Abernethy (1764-1831), surgeon and teacher

With this quote Sir William Osler began his address, “The Hospital as a College?” to the Academy of Medicine in New York in 1903. His second quote for this report was from the famed physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in 1867:

“The most essential part of a student’s instruction is obtained, as I believe, not in the lecture room, but at the bedside. Nothing seen there is lost: the rhythms of disease are learned by frequent repetition: its unforeseen occurrence stamp themselves indelibly on the memory. Before the student is aware of what he had acquired he has learned the aspects and causes and probable issue of the disease he has seen with his teacher and the proper mode of dealing with them, as far as his master knows.”

In his report Osler was celebrating a quarter century’s success in education. He demanded a better general education for students, a lengthened period for professional study, and the substitution of theoretical by practical learning. He wanted the student not to learn only from dissecting the sympathetic nervous system but to learn to “take a blood pressure observation” with a kymograph (an instrument used to record the temporal variations of any physiological or muscular process; it consists essentially of a revolving drum, bearing a record sheet on which a stylus travels).

Osler observed that there should be no teaching without a patient for a text: “The whole of medicine is in observation” that the teacher’s art is educating the student’s finger to feel and eyes to see. Give the student good methods and a proper point of view, and experience will do the rest.

Osler expressed confidence that students would keep the hospital physician from slovenliness and improve the care of patients. He was also concerned that “we ask too much of the resident physicians, whose number has not increased in proportion to the enormous amount of work thrust upon them.” Students were the answer, the proto-scut-monkey.

The practicality of working out of a teaching hospital was outlined at length in Osler’s report. The student’s third year should begin with a systematic physical diagnosis course, first in history taking, then in writing reports. Concurrently, a physical examination course should be given several days a week with individual cases assigned to students to follow, and instruction is accessing the literature. Next comes clinical microscopy—an essential in an era where there was often no lab to call upon. In general, medical clinic occurs one day a week when interesting cases are brought from the wards. Of note, committees were appointed to report on every case of pneumonia.

In revamping medical education Osler brought the third-year students to the outpatient clinic and the fourth-year students to the wards. What implication does this have for us as hospitalists?