User login

Short-Term Storage of Platelet-Rich Plasma at Room Temperature Does Not Affect Growth Factor or Catabolic Cytokine Concentration

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to provide clinical recommendations about the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) that was subjected to short-term storage at room temperature. We determined bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations as indicators of platelet and white blood cell degranulation in blood and PRP. Additionally, this study sought to validate the use of manual, direct smear analysis as an alternative to automated methods for platelet quantification in PRP.

Blood was used to generate low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) or high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). Blood was either processed immediately or kept at room temperature for 2 or 4 hours prior to generation of PRP, which was then held at room temperature for 0, 1, 2, or 4 hours. Subsequently, bioactive transforming growth factor beta-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 were measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). Manual and automated platelet counts were performed on all blood and PRP samples.

There were no differences in growth factor or cytokine concentration when blood or Llo PRP or Lhi PRP was retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. Manual, direct smear analysis for platelet quantification was not different from the use of automated machine counting for PRP samples, but in the starting blood samples, manual platelet counts were significantly higher than those generated using automated technology.

When there is a delay of up to 4 hours in the generation of PRP from blood or in the application of PRP to the patient, bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations remain stable in both blood and PRP. A manual direct counting method is a simple, cost-effective, and valid method to measure the contents of the PRP product being delivered to the patient.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is used to promote healing in many areas of medicine, such as dental surgery,1,2 soft-tissue injury,3,4 orthopedic surgery,5,6 wound healing,7 and veterinary medicine.8,9 Despite its extensive use, there are still questions about the clinical efficacy of PRP.10-12 Due to biological heterogeneity between patients13,14 and differences between available manufacturing kits,13,15 PRP can be highly variable between patients. There are classification schemes to categorize the various types of PRP,16-18 which can be divided broadly into low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) and high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). PRP can be used as a point of care therapy, prepared and used immediately, or it can be used during a surgical procedure. In some institutions, blood is drawn by a phlebotomist, processed in the hospital laboratory, and then delivered to the operating room. In other instances, PRP is generated patient-side by the primary attending physician’s team, who draws the blood and processes it for immediate use.5,19 Delays at any step in these various scenarios could lead to the blood or the resultant PRP remaining at room temperature from minutes to several hours prior to administration to the patient. This variability in PRP protocols between clinical and surgical settings adds to concerns regarding the stability and efficacy of the biologic.

Continue to: When performing clinical or research...

When performing clinical or research studies using PRP, it is important to report the contents of the PRP delivered to the patient. By documenting the cellular content of the PRP delivered to the patient, the common questions of optimal platelet dose and the importance of leukocytes in PRP can begin to be answered. There are some known factors that contribute to PRP variability, such as patient biology and operator technique, but there are many other unknown factors. In some instances, there is a failure to generate PRP, defined as a lower platelet count in the PRP preparation than in the starting blood sample.13,14 To measure the platelet and cellular contents of the starting blood and PRP, samples can be submitted to a clinical pathology laboratory for a complete blood count, which adds cost to the patient above the typically unreimbursed cost of the PRP injection itself. An alternative method for measuring platelet concentrations is the use of direct smear analysis on glass slides. The use of direct smears to measure platelet concentration is well validated for blood,20,21 but the use of direct smears of PRP for determining platelet concentrations has not been previously validated. The use of manual platelet counts would provide an alternative to automated platelet counting for clinical and preclinical research studies to characterize the type of PRP administered to the patient.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if retention of blood or PRP at room temperature for various time intervals had an effect on final growth factor or catabolic cytokine concentration. Bioactive transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) were measured as representatives of growth factors and catabolic cytokines, respectively. The secondary aim was to identify if manual platelet counts were an accurate reflection of automated counts. The outcomes of these experiments should provide immediately relevant information for the clinical application of PRP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood Collection and Generation of PRP

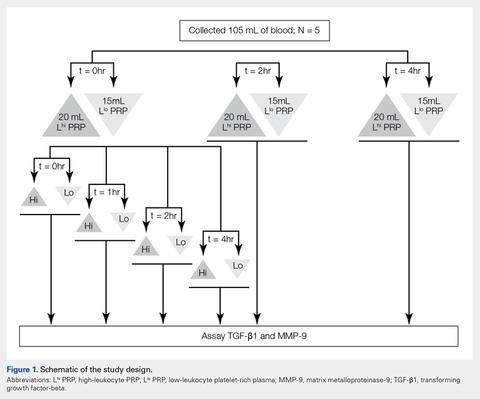

Under Institutional Review Board approval, blood (105 mL) was collected from healthy human volunteers (N = 5) into a syringe containing acid citrate dextrose anticoagulant to a final concentration of 10% acid citrate dextrose. Three 15-mL aliquots of blood were used to generate Llo PRP (Autologous Conditioned Plasma Double Syringe, Arthrex) and three 20-mL aliquots were used to generate Lhi PRP (SmartPReP 2, Harvest Technologies) (Figure 1).

Automated and Manual Counts

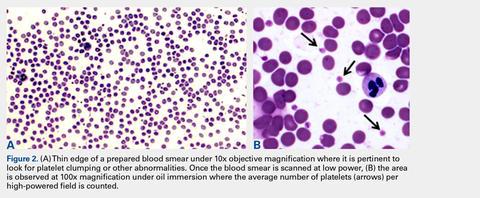

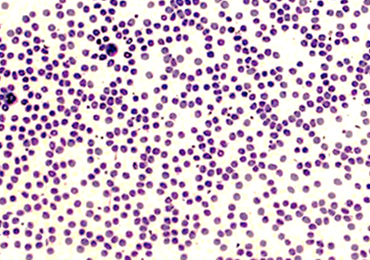

Automated complete blood counts were performed by a board certified clinical pathologist in the clinical pathology department of Cornell University on all blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples. A manual platelet count, using a modified Giemsa stain,22 was performed on smears of all blood and PRP samples (Video). Slides were scanned at 10x magnification to identify an area where many red blood cells were present while maintaining a clear field of view (Figure 2A). The magnification was then increased to 100x using oil immersion, and the total number of platelets was counted in 10 fields of view (Figure 2B).

Growth Factor and Catabolic Cytokine Measurements

Blood and PRP samples were thawed for ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) analysis. TGF-β1 concentration was determined using the TGF-β1 Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega Corporation), which measures biologically active TGF-β1. We chose TGF-β1 because it is commonly measured in PRP studies as an anabolic cytokine with multiple effects on tissue healing. The functions of TGF-β1 include stimulation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cell proliferation; regulation of endothelial, fibroblast, and osteoblast mitogenesis; coordination of collagen synthesis; promotion of endothelial chemotaxis and angiogenesis; activation of extracellular matrix synthesis in cartilage; and reduction of the catabolic activity of interluekin-1 and MMPs.23-25 In addition, TGF-β1 concentration strongly correlates with platelet concentration.26 MMP-9 concentration was determined using the MMP-9 Biotrak Activity Assay (GE Healthcare Biosciences) which measures both active and pro- forms of MMP-9. In PRP, MMP-9 was measured as an indicator of white blood cell (WBC) concentration.26 A catabolic cytokine capable of degrading collagen,13,27 MMP-9 has been linked to poor healing.28 For both assays, samples were measured in duplicate using a multiple detection plate reader (Tecan Safire).

Continue to: Statistical Analysis...

Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for the normal distribution to determine the appropriate statistical test. Manual and automated platelet counts were compared to each other in whole blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples using a paired t test. Bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations in blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP, were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunn’s all-pairwise comparison. Bioactive and pro-MMP-9 concentrations measured in the retained blood or PRP samples were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s all-pairwise comparison. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistix 9 software (Analytical Software). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Validation of PRP

PRP, as defined by an increase in platelet concentration in PRP compared with blood, was successfully generated in all samples by both systems. There was an average 1.98 ± 0.14-fold increase in platelet concentration in Llo PRP and an average 3.06 ± 0.24-fold increase in Lhi PRP. Platelet concentration was significantly higher in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.001). Compared to whole blood, WBC concentration was 0.47 ± 0.07-fold lower in Llo PRP and 1.98 ± 0.14-fold greater in Lhi PRP. Similar to platelets, WBCs were significantly greater in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.02).

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in Blood Retained at Room Temperature

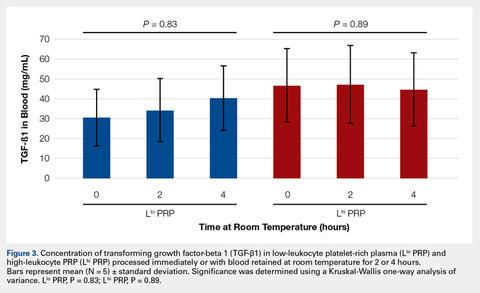

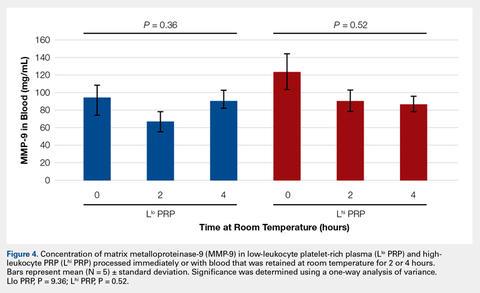

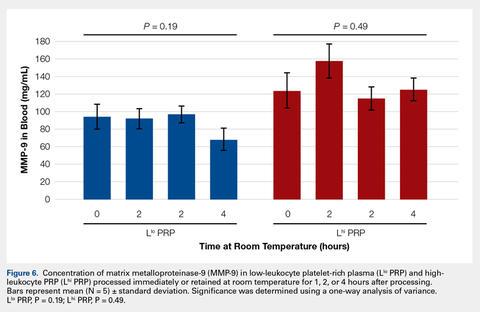

To reflect the clinical situation where blood would be drawn from a patient, but there would be a delay in processing the blood to generate PRP, blood samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. Neither bioactive TGF-β1 (Figure 3) nor bioactive/pro-MMP-9 concentrations (Figure 4) changed significantly over time when blood was retained at room temperature prior to centrifugation to generate PRP.

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in PRP Retained at Room Temperature

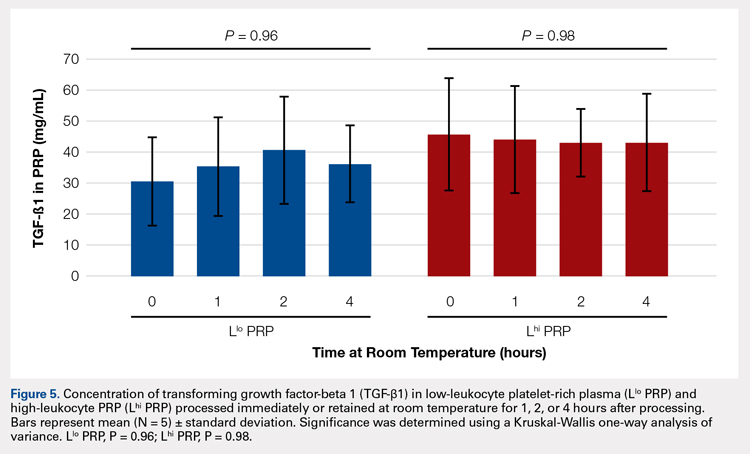

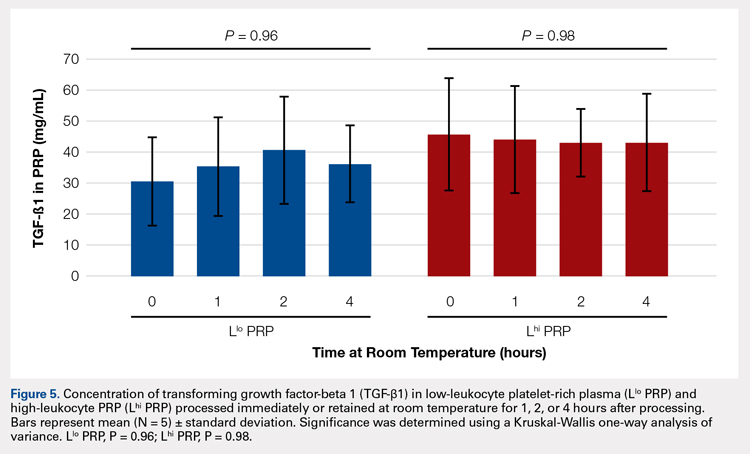

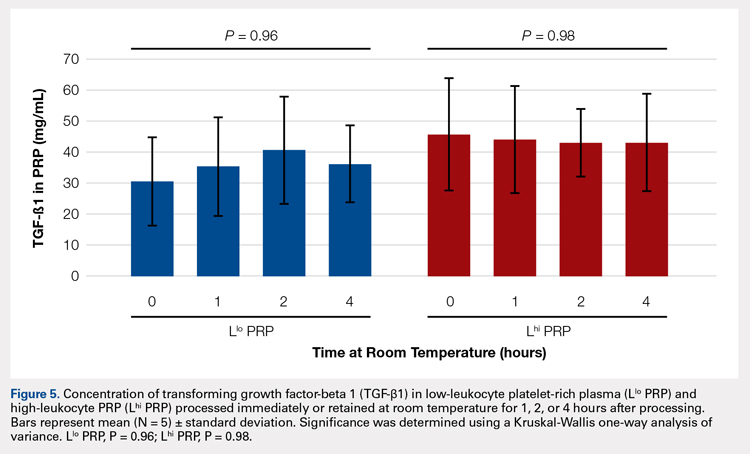

In order to mimic the clinical situation where PRP would be generated but might sit out prior to being administered to the patient, PRP samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. In these samples, bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations were not significantly different between PRP products analyzed immediately and those samples retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours (Figure 5).

Automatic vs Manual Platelet Count

Manual platelet counts were compared to automated platelet counts to determine if a manual platelet smear analysis could be a reliable method for analyzing PRP in clinical and pre-clinical studies. There was a significant difference between the automated and manual platelet counts in blood samples (Table) (P = 0.05, N = 5) with the manual platelet count having a higher average (99.1 thou/uL) platelet concentration than automated counts. Platelet clumping was identified in 2 automated counts, which falsely decreased platelet concentration by an unknown quantity. Manual platelet counts for both Llo PRP (n = 30) and Lhi PRP (n = 30) were not different from automated platelet counts. Platelet clumping was not reported on any manual platelet counts performed on PRP samples.

Table. Platelet Concentrations of Whole Blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP (N = 5)

| |||||

| Automated Count | Manual Count | P Value | ||

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range |

|

Blood | 111.8 ± 59.5 | 54-202 | 210.9 ± 59.4 | 144-297 | 0.05 |

Llo PRP | 421.4 ± 132.8 | 319-620 | 410.1 ± 94.2 | 318-543 | 0.61 |

Lhi PRP | 634.4 ± 88.8 | 517-766 | 635.4 ± 176.6 | 491-933 | 0.99 |

A paired t test was performed to compare results obtained from an automated platelet count and those obtained from a manual count.

Abbreviations: Lhi PRP, high-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; Llo PRP, low-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; SD, standard deviation.

Continue to:The primary aim of this study...

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to improve the clinical use of PRP by characterizing changes that might occur due to extended preparation times. Physicians commonly question the stability of blood or PRP if it is retained at room temperature prior to being administered to the patient. Clinical recommendations to optimize PRP preparation can be derived from a better understanding of the stability of platelets and WBCs, which contribute to the anabolic and catabolic cytokines in PRP.

The results of this study suggest that platelets and WBCs remain stable in blood and both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP for up to 4 hours. The use of bioactive ELISAs to measure TGF-β1 and MMP-9 allows for determination of stability of the PRP product retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. This provides a time buffer to allow for delays from either institutional logistics or unanticipated clinical delays, without adverse effects on the generation of the final PRP product. As with all biologics, there are many factors that contribute to variability, but a relatively short delay of up to 4 hours in either generation of PRP from blood or in administration of PRP to the patient does not appear to contribute to that variability. Similar studies have been performed on equine PRP and suggest that growth factor concentrations remain stable for up to 6 hours after preparation of PRP29 and in human PRP, which implies that although samples degrade over time, platelet integrity might be acceptable for clinical use for up to 5 days after preparation, particularly if stored in oxygen.30 In contrast to this study, neither of the previously published reports used assays to measure biological activity in the stored PRP. Regardless of the variability between the studies with respect to the type of PRP evaluated and the outcome measures used, all of the studies support the concept that PRP can be stored at room temperature for at least a few hours before clinical use.

Centrifugation of blood does not guarantee the generation of PRP.13,14 In some cases, platelet counts in PRP are similar to or even less than that in the starting whole blood sample. To determine whether a clinical outcome is attributed to PRP, it is vital to know the platelet concentration and, arguably, the WBC concentration in the blood used to generate PRP and in the PRP sample administered to the patient. The platelet concentration in blood and PRP samples can be quantified using automated or manual methods. The use of automated methods can add significant cost to a study or procedure. Manually evaluating a blood smear is an accepted, though more time consuming, method of analyzing cellular components of a blood sample. Depending on the standard operating procedure of the laboratory, manual smears are often done in conjunction with an automated count. This identifies abnormalities in cellular shape or size, or platelet clumping, which are not consistently recognized by automated methods. Manually evaluating a blood smear does take some training, but the material cost is very low, which has added value for clinical or preclinical research studies. Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that manual platelet counts in blood may be more accurate than the count generated from an automated counter because the automated platelet counts were falsely low due to platelet clumping. Platelet clumping can occur as early as 1 hour after blood collection, regardless of the type of anticoagulant used.31

LIMITATIONS

The sample size of this study was small. However, variability in PRP has been well documented in multiple other studies using slightly larger sample sizes.13,14,16 Another potential limitation of this study could be that only one growth factor, TGF-β1, and one catabolic cytokine, MMP-9, were used as surrogate measures to represent platelet and WBC stability, respectively. We chose TGF-β1 because it is correlated with platelet concentrations14,15,26 and MMP-9 because it is an indicator of catabolic factors in PRP that have been correlated with WBC concentrations.26

CONCLUSION

This study illustrated that growth factor and cytokine concentrations in both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP are stable for up to 4 hours. The clinical implications of these results suggest that if the generation or administration of PRP is delayed by up to 4 hours, the resultant PRP retains its bioactivity and is acceptable for clinical application. However, given the known variability of PRP generated due to patient and manufacturer variability,13,14 it is still important to ensure that the product is indeed PRP, with an increase in platelet number over the starting sample of blood. This validation can be performed with a simple and cost-effective manual smear analysis of blood and PRP. The results of this study provide information that can be immediately translated into clinical, surgical, and research practices.

1. Nikolidakis D, Jansen JA. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in oral surgery: Literature review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(3):249-258. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0062.

2. Sánchez AR, Sheridan PJ, Kupp LI. Is platelet-rich plasma the perfect enhancement factor? A current review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18(1):93-103.

3. Monto RR. Platelet rich plasma treatment for chronic achilles tendinosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(5):379-385. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0379.

4. Owens RF, Ginnetti J, Conti SF, Latona C. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes following platelet rich plasma injection for chronic midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy. Foot ankle Int. 2011;32(11):1032-1039. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.1032.

5. Sánchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, Andía I, Padilla S, Mujika I. Comparison of surgically repaired achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):245-251. doi:10.1177/0363546506294078.

6. Silva A, Sampaio R. Anatomic ACL reconstruction: does the platelet-rich plasma accelerate tendon healing? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(6):676-682. doi:10.1007/s00167-009-0762-8.

7. Fréchette JP, Martineau I, Gagnon G. Platelet-rich plasmas: growth factor content and roles in wound healing. J Dent Res. 2005;84(5):434-439. doi:10.1177/154405910508400507.

8. Bosch G, René van Weeren P, Barneveld A, van Schie HTM. Computerised analysis of standardised ultrasonographic images to monitor the repair of surgically created core lesions in equine superficial digital flexor tendons following treatment with intratendinous platelet rich plasma or placebo. Vet J. 2011;187(1):92-98. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.10.014.

9. Torricelli P, Fini M, Filardo G, et al. Regenerative medicine for the treatment of musculoskeletal overuse injuries in competition horses. Int Orthop. 2011;35(10):1569-1576. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1237-3.

10. Sampson S, Gerhardt M, Mandelbaum B. Platelet rich plasma injection grafts for musculoskeletal injuries: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(3-4):165-174. doi:10.1007/s12178-008-9032-5.

11. Sheth U, Simunovic N, Klein G, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma use for orthopaedic indications: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):298-307. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00154.

12. Vannini F, Di Matteo B, Filardo G, Kon E, Marcacci M, Giannini S. Platelet-rich plasma for foot and ankle pathologies: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;20(1):2-9. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2013.08.001.

13. Boswell SG, Cole BJ, Sundman EA, Karas V, Fortier LA. Platelet-rich plasma: a milieu of bioactive factors. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):429-439. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.018.

14. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308-316. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00430.

15. Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266-271. doi:10.1177/0363546510387517.

16. Arnoczky SP, Sheibani-Rad S, Shebani-Rad S. The basic science of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what clinicians need to know. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):180-185. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182999712.

17. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Bielecki T, Corso M Del, Inchingolo F, Sammartino G. Shedding light in the controversial terminology for platelet-rich products: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-leukocyte gel (PLG), preparation rich in growth factors (PRGF), classification and commercialism. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2010;95A(4):1280-1282. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32894.

18. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):158-167. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009.

19. Everts PA, Knape JT, Weibrich G, et al. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: a review. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38(2):174-187.

20. Malok M, Titchener EH, Bridgers C, Lee BY, Bamberg R. Comparison of two platelet count estimation methodologies for peripheral blood smears. Clin Lab Sci. 2007;20(3):154-160.

21. Gulati G, Uppal G, Florea AD, Gong J. Detection of platelet clumps on peripheral blood smears by CellaVision DM96 System and Microscopic Review. Lab Med. 2014;45(4):368-371. doi:10.1309/LM604RQVKVLRFXOR.

22. Gulati G, Song J, Florea AD, Gong J. Purpose and criteria for blood smear scan, blood smear examination, and blood smear review. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33(1):1-7. doi:10.3343/alm.2013.33.1.1.

23. Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Perspective article: Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(5):585-601. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x.

24. Crane D, Everts P. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) matrix grafts. Pract Pain Manag. 2008;8(1):12-26.

25. Fortier LA, Barker JU, Strauss EJ, McCarrel TM, Cole BJ. The role of growth factors in cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2706-2715. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1857-3.

26. Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2135-2140. doi:10.1177/0363546511417792.

27. Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93(3):411-422.

28. Watelet JB, Demetter P, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Cuvelier C, Bachert C. Neutrophil-derived metalloproteinase-9 predicts healing quality after sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):56-61. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000150674.30237.3f.

29. Hauschild G, Geburek F, Gosheger G, et al. Short term storage stability at room temperature of two different platelet-rich plasma preparations from equine donors and potential impact on growth factor concentrations. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12917-016-0920-4.

30. Moore GW, Maloney JC, Archer RA, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for tissue regeneration can be stored at room temperature for at least five days. Br J Biomed Sci. 2017;74(2):71-77. doi:10.1080/09674845.2016.1233792.

31. McShine RL, Sibinga S, Brozovic B. Differences between the effects of EDTA and citrate anticoagulants on platelet count and mean platelet volume. Clin Lab Haematol. 1990;12(3):277-285.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to provide clinical recommendations about the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) that was subjected to short-term storage at room temperature. We determined bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations as indicators of platelet and white blood cell degranulation in blood and PRP. Additionally, this study sought to validate the use of manual, direct smear analysis as an alternative to automated methods for platelet quantification in PRP.

Blood was used to generate low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) or high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). Blood was either processed immediately or kept at room temperature for 2 or 4 hours prior to generation of PRP, which was then held at room temperature for 0, 1, 2, or 4 hours. Subsequently, bioactive transforming growth factor beta-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 were measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). Manual and automated platelet counts were performed on all blood and PRP samples.

There were no differences in growth factor or cytokine concentration when blood or Llo PRP or Lhi PRP was retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. Manual, direct smear analysis for platelet quantification was not different from the use of automated machine counting for PRP samples, but in the starting blood samples, manual platelet counts were significantly higher than those generated using automated technology.

When there is a delay of up to 4 hours in the generation of PRP from blood or in the application of PRP to the patient, bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations remain stable in both blood and PRP. A manual direct counting method is a simple, cost-effective, and valid method to measure the contents of the PRP product being delivered to the patient.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is used to promote healing in many areas of medicine, such as dental surgery,1,2 soft-tissue injury,3,4 orthopedic surgery,5,6 wound healing,7 and veterinary medicine.8,9 Despite its extensive use, there are still questions about the clinical efficacy of PRP.10-12 Due to biological heterogeneity between patients13,14 and differences between available manufacturing kits,13,15 PRP can be highly variable between patients. There are classification schemes to categorize the various types of PRP,16-18 which can be divided broadly into low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) and high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). PRP can be used as a point of care therapy, prepared and used immediately, or it can be used during a surgical procedure. In some institutions, blood is drawn by a phlebotomist, processed in the hospital laboratory, and then delivered to the operating room. In other instances, PRP is generated patient-side by the primary attending physician’s team, who draws the blood and processes it for immediate use.5,19 Delays at any step in these various scenarios could lead to the blood or the resultant PRP remaining at room temperature from minutes to several hours prior to administration to the patient. This variability in PRP protocols between clinical and surgical settings adds to concerns regarding the stability and efficacy of the biologic.

Continue to: When performing clinical or research...

When performing clinical or research studies using PRP, it is important to report the contents of the PRP delivered to the patient. By documenting the cellular content of the PRP delivered to the patient, the common questions of optimal platelet dose and the importance of leukocytes in PRP can begin to be answered. There are some known factors that contribute to PRP variability, such as patient biology and operator technique, but there are many other unknown factors. In some instances, there is a failure to generate PRP, defined as a lower platelet count in the PRP preparation than in the starting blood sample.13,14 To measure the platelet and cellular contents of the starting blood and PRP, samples can be submitted to a clinical pathology laboratory for a complete blood count, which adds cost to the patient above the typically unreimbursed cost of the PRP injection itself. An alternative method for measuring platelet concentrations is the use of direct smear analysis on glass slides. The use of direct smears to measure platelet concentration is well validated for blood,20,21 but the use of direct smears of PRP for determining platelet concentrations has not been previously validated. The use of manual platelet counts would provide an alternative to automated platelet counting for clinical and preclinical research studies to characterize the type of PRP administered to the patient.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if retention of blood or PRP at room temperature for various time intervals had an effect on final growth factor or catabolic cytokine concentration. Bioactive transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) were measured as representatives of growth factors and catabolic cytokines, respectively. The secondary aim was to identify if manual platelet counts were an accurate reflection of automated counts. The outcomes of these experiments should provide immediately relevant information for the clinical application of PRP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood Collection and Generation of PRP

Under Institutional Review Board approval, blood (105 mL) was collected from healthy human volunteers (N = 5) into a syringe containing acid citrate dextrose anticoagulant to a final concentration of 10% acid citrate dextrose. Three 15-mL aliquots of blood were used to generate Llo PRP (Autologous Conditioned Plasma Double Syringe, Arthrex) and three 20-mL aliquots were used to generate Lhi PRP (SmartPReP 2, Harvest Technologies) (Figure 1).

Automated and Manual Counts

Automated complete blood counts were performed by a board certified clinical pathologist in the clinical pathology department of Cornell University on all blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples. A manual platelet count, using a modified Giemsa stain,22 was performed on smears of all blood and PRP samples (Video). Slides were scanned at 10x magnification to identify an area where many red blood cells were present while maintaining a clear field of view (Figure 2A). The magnification was then increased to 100x using oil immersion, and the total number of platelets was counted in 10 fields of view (Figure 2B).

Growth Factor and Catabolic Cytokine Measurements

Blood and PRP samples were thawed for ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) analysis. TGF-β1 concentration was determined using the TGF-β1 Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega Corporation), which measures biologically active TGF-β1. We chose TGF-β1 because it is commonly measured in PRP studies as an anabolic cytokine with multiple effects on tissue healing. The functions of TGF-β1 include stimulation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cell proliferation; regulation of endothelial, fibroblast, and osteoblast mitogenesis; coordination of collagen synthesis; promotion of endothelial chemotaxis and angiogenesis; activation of extracellular matrix synthesis in cartilage; and reduction of the catabolic activity of interluekin-1 and MMPs.23-25 In addition, TGF-β1 concentration strongly correlates with platelet concentration.26 MMP-9 concentration was determined using the MMP-9 Biotrak Activity Assay (GE Healthcare Biosciences) which measures both active and pro- forms of MMP-9. In PRP, MMP-9 was measured as an indicator of white blood cell (WBC) concentration.26 A catabolic cytokine capable of degrading collagen,13,27 MMP-9 has been linked to poor healing.28 For both assays, samples were measured in duplicate using a multiple detection plate reader (Tecan Safire).

Continue to: Statistical Analysis...

Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for the normal distribution to determine the appropriate statistical test. Manual and automated platelet counts were compared to each other in whole blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples using a paired t test. Bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations in blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP, were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunn’s all-pairwise comparison. Bioactive and pro-MMP-9 concentrations measured in the retained blood or PRP samples were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s all-pairwise comparison. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistix 9 software (Analytical Software). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Validation of PRP

PRP, as defined by an increase in platelet concentration in PRP compared with blood, was successfully generated in all samples by both systems. There was an average 1.98 ± 0.14-fold increase in platelet concentration in Llo PRP and an average 3.06 ± 0.24-fold increase in Lhi PRP. Platelet concentration was significantly higher in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.001). Compared to whole blood, WBC concentration was 0.47 ± 0.07-fold lower in Llo PRP and 1.98 ± 0.14-fold greater in Lhi PRP. Similar to platelets, WBCs were significantly greater in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.02).

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in Blood Retained at Room Temperature

To reflect the clinical situation where blood would be drawn from a patient, but there would be a delay in processing the blood to generate PRP, blood samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. Neither bioactive TGF-β1 (Figure 3) nor bioactive/pro-MMP-9 concentrations (Figure 4) changed significantly over time when blood was retained at room temperature prior to centrifugation to generate PRP.

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in PRP Retained at Room Temperature

In order to mimic the clinical situation where PRP would be generated but might sit out prior to being administered to the patient, PRP samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. In these samples, bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations were not significantly different between PRP products analyzed immediately and those samples retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours (Figure 5).

Automatic vs Manual Platelet Count

Manual platelet counts were compared to automated platelet counts to determine if a manual platelet smear analysis could be a reliable method for analyzing PRP in clinical and pre-clinical studies. There was a significant difference between the automated and manual platelet counts in blood samples (Table) (P = 0.05, N = 5) with the manual platelet count having a higher average (99.1 thou/uL) platelet concentration than automated counts. Platelet clumping was identified in 2 automated counts, which falsely decreased platelet concentration by an unknown quantity. Manual platelet counts for both Llo PRP (n = 30) and Lhi PRP (n = 30) were not different from automated platelet counts. Platelet clumping was not reported on any manual platelet counts performed on PRP samples.

Table. Platelet Concentrations of Whole Blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP (N = 5)

| |||||

| Automated Count | Manual Count | P Value | ||

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range |

|

Blood | 111.8 ± 59.5 | 54-202 | 210.9 ± 59.4 | 144-297 | 0.05 |

Llo PRP | 421.4 ± 132.8 | 319-620 | 410.1 ± 94.2 | 318-543 | 0.61 |

Lhi PRP | 634.4 ± 88.8 | 517-766 | 635.4 ± 176.6 | 491-933 | 0.99 |

A paired t test was performed to compare results obtained from an automated platelet count and those obtained from a manual count.

Abbreviations: Lhi PRP, high-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; Llo PRP, low-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; SD, standard deviation.

Continue to:The primary aim of this study...

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to improve the clinical use of PRP by characterizing changes that might occur due to extended preparation times. Physicians commonly question the stability of blood or PRP if it is retained at room temperature prior to being administered to the patient. Clinical recommendations to optimize PRP preparation can be derived from a better understanding of the stability of platelets and WBCs, which contribute to the anabolic and catabolic cytokines in PRP.

The results of this study suggest that platelets and WBCs remain stable in blood and both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP for up to 4 hours. The use of bioactive ELISAs to measure TGF-β1 and MMP-9 allows for determination of stability of the PRP product retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. This provides a time buffer to allow for delays from either institutional logistics or unanticipated clinical delays, without adverse effects on the generation of the final PRP product. As with all biologics, there are many factors that contribute to variability, but a relatively short delay of up to 4 hours in either generation of PRP from blood or in administration of PRP to the patient does not appear to contribute to that variability. Similar studies have been performed on equine PRP and suggest that growth factor concentrations remain stable for up to 6 hours after preparation of PRP29 and in human PRP, which implies that although samples degrade over time, platelet integrity might be acceptable for clinical use for up to 5 days after preparation, particularly if stored in oxygen.30 In contrast to this study, neither of the previously published reports used assays to measure biological activity in the stored PRP. Regardless of the variability between the studies with respect to the type of PRP evaluated and the outcome measures used, all of the studies support the concept that PRP can be stored at room temperature for at least a few hours before clinical use.

Centrifugation of blood does not guarantee the generation of PRP.13,14 In some cases, platelet counts in PRP are similar to or even less than that in the starting whole blood sample. To determine whether a clinical outcome is attributed to PRP, it is vital to know the platelet concentration and, arguably, the WBC concentration in the blood used to generate PRP and in the PRP sample administered to the patient. The platelet concentration in blood and PRP samples can be quantified using automated or manual methods. The use of automated methods can add significant cost to a study or procedure. Manually evaluating a blood smear is an accepted, though more time consuming, method of analyzing cellular components of a blood sample. Depending on the standard operating procedure of the laboratory, manual smears are often done in conjunction with an automated count. This identifies abnormalities in cellular shape or size, or platelet clumping, which are not consistently recognized by automated methods. Manually evaluating a blood smear does take some training, but the material cost is very low, which has added value for clinical or preclinical research studies. Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that manual platelet counts in blood may be more accurate than the count generated from an automated counter because the automated platelet counts were falsely low due to platelet clumping. Platelet clumping can occur as early as 1 hour after blood collection, regardless of the type of anticoagulant used.31

LIMITATIONS

The sample size of this study was small. However, variability in PRP has been well documented in multiple other studies using slightly larger sample sizes.13,14,16 Another potential limitation of this study could be that only one growth factor, TGF-β1, and one catabolic cytokine, MMP-9, were used as surrogate measures to represent platelet and WBC stability, respectively. We chose TGF-β1 because it is correlated with platelet concentrations14,15,26 and MMP-9 because it is an indicator of catabolic factors in PRP that have been correlated with WBC concentrations.26

CONCLUSION

This study illustrated that growth factor and cytokine concentrations in both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP are stable for up to 4 hours. The clinical implications of these results suggest that if the generation or administration of PRP is delayed by up to 4 hours, the resultant PRP retains its bioactivity and is acceptable for clinical application. However, given the known variability of PRP generated due to patient and manufacturer variability,13,14 it is still important to ensure that the product is indeed PRP, with an increase in platelet number over the starting sample of blood. This validation can be performed with a simple and cost-effective manual smear analysis of blood and PRP. The results of this study provide information that can be immediately translated into clinical, surgical, and research practices.

ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to provide clinical recommendations about the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) that was subjected to short-term storage at room temperature. We determined bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations as indicators of platelet and white blood cell degranulation in blood and PRP. Additionally, this study sought to validate the use of manual, direct smear analysis as an alternative to automated methods for platelet quantification in PRP.

Blood was used to generate low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) or high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). Blood was either processed immediately or kept at room temperature for 2 or 4 hours prior to generation of PRP, which was then held at room temperature for 0, 1, 2, or 4 hours. Subsequently, bioactive transforming growth factor beta-1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 were measured by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). Manual and automated platelet counts were performed on all blood and PRP samples.

There were no differences in growth factor or cytokine concentration when blood or Llo PRP or Lhi PRP was retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. Manual, direct smear analysis for platelet quantification was not different from the use of automated machine counting for PRP samples, but in the starting blood samples, manual platelet counts were significantly higher than those generated using automated technology.

When there is a delay of up to 4 hours in the generation of PRP from blood or in the application of PRP to the patient, bioactive growth factor and cytokine concentrations remain stable in both blood and PRP. A manual direct counting method is a simple, cost-effective, and valid method to measure the contents of the PRP product being delivered to the patient.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is used to promote healing in many areas of medicine, such as dental surgery,1,2 soft-tissue injury,3,4 orthopedic surgery,5,6 wound healing,7 and veterinary medicine.8,9 Despite its extensive use, there are still questions about the clinical efficacy of PRP.10-12 Due to biological heterogeneity between patients13,14 and differences between available manufacturing kits,13,15 PRP can be highly variable between patients. There are classification schemes to categorize the various types of PRP,16-18 which can be divided broadly into low-leukocyte PRP (Llo PRP) and high-leukocyte PRP (Lhi PRP). PRP can be used as a point of care therapy, prepared and used immediately, or it can be used during a surgical procedure. In some institutions, blood is drawn by a phlebotomist, processed in the hospital laboratory, and then delivered to the operating room. In other instances, PRP is generated patient-side by the primary attending physician’s team, who draws the blood and processes it for immediate use.5,19 Delays at any step in these various scenarios could lead to the blood or the resultant PRP remaining at room temperature from minutes to several hours prior to administration to the patient. This variability in PRP protocols between clinical and surgical settings adds to concerns regarding the stability and efficacy of the biologic.

Continue to: When performing clinical or research...

When performing clinical or research studies using PRP, it is important to report the contents of the PRP delivered to the patient. By documenting the cellular content of the PRP delivered to the patient, the common questions of optimal platelet dose and the importance of leukocytes in PRP can begin to be answered. There are some known factors that contribute to PRP variability, such as patient biology and operator technique, but there are many other unknown factors. In some instances, there is a failure to generate PRP, defined as a lower platelet count in the PRP preparation than in the starting blood sample.13,14 To measure the platelet and cellular contents of the starting blood and PRP, samples can be submitted to a clinical pathology laboratory for a complete blood count, which adds cost to the patient above the typically unreimbursed cost of the PRP injection itself. An alternative method for measuring platelet concentrations is the use of direct smear analysis on glass slides. The use of direct smears to measure platelet concentration is well validated for blood,20,21 but the use of direct smears of PRP for determining platelet concentrations has not been previously validated. The use of manual platelet counts would provide an alternative to automated platelet counting for clinical and preclinical research studies to characterize the type of PRP administered to the patient.

The primary aim of this study was to determine if retention of blood or PRP at room temperature for various time intervals had an effect on final growth factor or catabolic cytokine concentration. Bioactive transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) were measured as representatives of growth factors and catabolic cytokines, respectively. The secondary aim was to identify if manual platelet counts were an accurate reflection of automated counts. The outcomes of these experiments should provide immediately relevant information for the clinical application of PRP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood Collection and Generation of PRP

Under Institutional Review Board approval, blood (105 mL) was collected from healthy human volunteers (N = 5) into a syringe containing acid citrate dextrose anticoagulant to a final concentration of 10% acid citrate dextrose. Three 15-mL aliquots of blood were used to generate Llo PRP (Autologous Conditioned Plasma Double Syringe, Arthrex) and three 20-mL aliquots were used to generate Lhi PRP (SmartPReP 2, Harvest Technologies) (Figure 1).

Automated and Manual Counts

Automated complete blood counts were performed by a board certified clinical pathologist in the clinical pathology department of Cornell University on all blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples. A manual platelet count, using a modified Giemsa stain,22 was performed on smears of all blood and PRP samples (Video). Slides were scanned at 10x magnification to identify an area where many red blood cells were present while maintaining a clear field of view (Figure 2A). The magnification was then increased to 100x using oil immersion, and the total number of platelets was counted in 10 fields of view (Figure 2B).

Growth Factor and Catabolic Cytokine Measurements

Blood and PRP samples were thawed for ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) analysis. TGF-β1 concentration was determined using the TGF-β1 Emax ImmunoAssay System (Promega Corporation), which measures biologically active TGF-β1. We chose TGF-β1 because it is commonly measured in PRP studies as an anabolic cytokine with multiple effects on tissue healing. The functions of TGF-β1 include stimulation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cell proliferation; regulation of endothelial, fibroblast, and osteoblast mitogenesis; coordination of collagen synthesis; promotion of endothelial chemotaxis and angiogenesis; activation of extracellular matrix synthesis in cartilage; and reduction of the catabolic activity of interluekin-1 and MMPs.23-25 In addition, TGF-β1 concentration strongly correlates with platelet concentration.26 MMP-9 concentration was determined using the MMP-9 Biotrak Activity Assay (GE Healthcare Biosciences) which measures both active and pro- forms of MMP-9. In PRP, MMP-9 was measured as an indicator of white blood cell (WBC) concentration.26 A catabolic cytokine capable of degrading collagen,13,27 MMP-9 has been linked to poor healing.28 For both assays, samples were measured in duplicate using a multiple detection plate reader (Tecan Safire).

Continue to: Statistical Analysis...

Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for the normal distribution to determine the appropriate statistical test. Manual and automated platelet counts were compared to each other in whole blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP samples using a paired t test. Bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations in blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP, were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunn’s all-pairwise comparison. Bioactive and pro-MMP-9 concentrations measured in the retained blood or PRP samples were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s all-pairwise comparison. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistix 9 software (Analytical Software). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Validation of PRP

PRP, as defined by an increase in platelet concentration in PRP compared with blood, was successfully generated in all samples by both systems. There was an average 1.98 ± 0.14-fold increase in platelet concentration in Llo PRP and an average 3.06 ± 0.24-fold increase in Lhi PRP. Platelet concentration was significantly higher in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.001). Compared to whole blood, WBC concentration was 0.47 ± 0.07-fold lower in Llo PRP and 1.98 ± 0.14-fold greater in Lhi PRP. Similar to platelets, WBCs were significantly greater in Lhi PRP than in Llo PRP (P = 0.02).

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in Blood Retained at Room Temperature

To reflect the clinical situation where blood would be drawn from a patient, but there would be a delay in processing the blood to generate PRP, blood samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. Neither bioactive TGF-β1 (Figure 3) nor bioactive/pro-MMP-9 concentrations (Figure 4) changed significantly over time when blood was retained at room temperature prior to centrifugation to generate PRP.

Bioactive TGF-β1 and MMP-9 Concentration in PRP Retained at Room Temperature

In order to mimic the clinical situation where PRP would be generated but might sit out prior to being administered to the patient, PRP samples were retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours prior to analysis. In these samples, bioactive TGF-β1 concentrations were not significantly different between PRP products analyzed immediately and those samples retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours (Figure 5).

Automatic vs Manual Platelet Count

Manual platelet counts were compared to automated platelet counts to determine if a manual platelet smear analysis could be a reliable method for analyzing PRP in clinical and pre-clinical studies. There was a significant difference between the automated and manual platelet counts in blood samples (Table) (P = 0.05, N = 5) with the manual platelet count having a higher average (99.1 thou/uL) platelet concentration than automated counts. Platelet clumping was identified in 2 automated counts, which falsely decreased platelet concentration by an unknown quantity. Manual platelet counts for both Llo PRP (n = 30) and Lhi PRP (n = 30) were not different from automated platelet counts. Platelet clumping was not reported on any manual platelet counts performed on PRP samples.

Table. Platelet Concentrations of Whole Blood, Llo PRP, and Lhi PRP (N = 5)

| |||||

| Automated Count | Manual Count | P Value | ||

| Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | Range |

|

Blood | 111.8 ± 59.5 | 54-202 | 210.9 ± 59.4 | 144-297 | 0.05 |

Llo PRP | 421.4 ± 132.8 | 319-620 | 410.1 ± 94.2 | 318-543 | 0.61 |

Lhi PRP | 634.4 ± 88.8 | 517-766 | 635.4 ± 176.6 | 491-933 | 0.99 |

A paired t test was performed to compare results obtained from an automated platelet count and those obtained from a manual count.

Abbreviations: Lhi PRP, high-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; Llo PRP, low-leukocyte platelet-rich plasma; SD, standard deviation.

Continue to:The primary aim of this study...

DISCUSSION

The primary aim of this study was to improve the clinical use of PRP by characterizing changes that might occur due to extended preparation times. Physicians commonly question the stability of blood or PRP if it is retained at room temperature prior to being administered to the patient. Clinical recommendations to optimize PRP preparation can be derived from a better understanding of the stability of platelets and WBCs, which contribute to the anabolic and catabolic cytokines in PRP.

The results of this study suggest that platelets and WBCs remain stable in blood and both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP for up to 4 hours. The use of bioactive ELISAs to measure TGF-β1 and MMP-9 allows for determination of stability of the PRP product retained at room temperature for up to 4 hours. This provides a time buffer to allow for delays from either institutional logistics or unanticipated clinical delays, without adverse effects on the generation of the final PRP product. As with all biologics, there are many factors that contribute to variability, but a relatively short delay of up to 4 hours in either generation of PRP from blood or in administration of PRP to the patient does not appear to contribute to that variability. Similar studies have been performed on equine PRP and suggest that growth factor concentrations remain stable for up to 6 hours after preparation of PRP29 and in human PRP, which implies that although samples degrade over time, platelet integrity might be acceptable for clinical use for up to 5 days after preparation, particularly if stored in oxygen.30 In contrast to this study, neither of the previously published reports used assays to measure biological activity in the stored PRP. Regardless of the variability between the studies with respect to the type of PRP evaluated and the outcome measures used, all of the studies support the concept that PRP can be stored at room temperature for at least a few hours before clinical use.

Centrifugation of blood does not guarantee the generation of PRP.13,14 In some cases, platelet counts in PRP are similar to or even less than that in the starting whole blood sample. To determine whether a clinical outcome is attributed to PRP, it is vital to know the platelet concentration and, arguably, the WBC concentration in the blood used to generate PRP and in the PRP sample administered to the patient. The platelet concentration in blood and PRP samples can be quantified using automated or manual methods. The use of automated methods can add significant cost to a study or procedure. Manually evaluating a blood smear is an accepted, though more time consuming, method of analyzing cellular components of a blood sample. Depending on the standard operating procedure of the laboratory, manual smears are often done in conjunction with an automated count. This identifies abnormalities in cellular shape or size, or platelet clumping, which are not consistently recognized by automated methods. Manually evaluating a blood smear does take some training, but the material cost is very low, which has added value for clinical or preclinical research studies. Interestingly, the results of this study indicate that manual platelet counts in blood may be more accurate than the count generated from an automated counter because the automated platelet counts were falsely low due to platelet clumping. Platelet clumping can occur as early as 1 hour after blood collection, regardless of the type of anticoagulant used.31

LIMITATIONS

The sample size of this study was small. However, variability in PRP has been well documented in multiple other studies using slightly larger sample sizes.13,14,16 Another potential limitation of this study could be that only one growth factor, TGF-β1, and one catabolic cytokine, MMP-9, were used as surrogate measures to represent platelet and WBC stability, respectively. We chose TGF-β1 because it is correlated with platelet concentrations14,15,26 and MMP-9 because it is an indicator of catabolic factors in PRP that have been correlated with WBC concentrations.26

CONCLUSION

This study illustrated that growth factor and cytokine concentrations in both Llo PRP and Lhi PRP are stable for up to 4 hours. The clinical implications of these results suggest that if the generation or administration of PRP is delayed by up to 4 hours, the resultant PRP retains its bioactivity and is acceptable for clinical application. However, given the known variability of PRP generated due to patient and manufacturer variability,13,14 it is still important to ensure that the product is indeed PRP, with an increase in platelet number over the starting sample of blood. This validation can be performed with a simple and cost-effective manual smear analysis of blood and PRP. The results of this study provide information that can be immediately translated into clinical, surgical, and research practices.

1. Nikolidakis D, Jansen JA. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in oral surgery: Literature review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(3):249-258. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0062.

2. Sánchez AR, Sheridan PJ, Kupp LI. Is platelet-rich plasma the perfect enhancement factor? A current review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18(1):93-103.

3. Monto RR. Platelet rich plasma treatment for chronic achilles tendinosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(5):379-385. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0379.

4. Owens RF, Ginnetti J, Conti SF, Latona C. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes following platelet rich plasma injection for chronic midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy. Foot ankle Int. 2011;32(11):1032-1039. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.1032.

5. Sánchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, Andía I, Padilla S, Mujika I. Comparison of surgically repaired achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):245-251. doi:10.1177/0363546506294078.

6. Silva A, Sampaio R. Anatomic ACL reconstruction: does the platelet-rich plasma accelerate tendon healing? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(6):676-682. doi:10.1007/s00167-009-0762-8.

7. Fréchette JP, Martineau I, Gagnon G. Platelet-rich plasmas: growth factor content and roles in wound healing. J Dent Res. 2005;84(5):434-439. doi:10.1177/154405910508400507.

8. Bosch G, René van Weeren P, Barneveld A, van Schie HTM. Computerised analysis of standardised ultrasonographic images to monitor the repair of surgically created core lesions in equine superficial digital flexor tendons following treatment with intratendinous platelet rich plasma or placebo. Vet J. 2011;187(1):92-98. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.10.014.

9. Torricelli P, Fini M, Filardo G, et al. Regenerative medicine for the treatment of musculoskeletal overuse injuries in competition horses. Int Orthop. 2011;35(10):1569-1576. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1237-3.

10. Sampson S, Gerhardt M, Mandelbaum B. Platelet rich plasma injection grafts for musculoskeletal injuries: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(3-4):165-174. doi:10.1007/s12178-008-9032-5.

11. Sheth U, Simunovic N, Klein G, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma use for orthopaedic indications: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):298-307. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00154.

12. Vannini F, Di Matteo B, Filardo G, Kon E, Marcacci M, Giannini S. Platelet-rich plasma for foot and ankle pathologies: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;20(1):2-9. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2013.08.001.

13. Boswell SG, Cole BJ, Sundman EA, Karas V, Fortier LA. Platelet-rich plasma: a milieu of bioactive factors. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):429-439. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.018.

14. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308-316. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00430.

15. Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266-271. doi:10.1177/0363546510387517.

16. Arnoczky SP, Sheibani-Rad S, Shebani-Rad S. The basic science of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what clinicians need to know. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):180-185. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182999712.

17. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Bielecki T, Corso M Del, Inchingolo F, Sammartino G. Shedding light in the controversial terminology for platelet-rich products: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-leukocyte gel (PLG), preparation rich in growth factors (PRGF), classification and commercialism. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2010;95A(4):1280-1282. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32894.

18. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):158-167. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009.

19. Everts PA, Knape JT, Weibrich G, et al. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: a review. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38(2):174-187.

20. Malok M, Titchener EH, Bridgers C, Lee BY, Bamberg R. Comparison of two platelet count estimation methodologies for peripheral blood smears. Clin Lab Sci. 2007;20(3):154-160.

21. Gulati G, Uppal G, Florea AD, Gong J. Detection of platelet clumps on peripheral blood smears by CellaVision DM96 System and Microscopic Review. Lab Med. 2014;45(4):368-371. doi:10.1309/LM604RQVKVLRFXOR.

22. Gulati G, Song J, Florea AD, Gong J. Purpose and criteria for blood smear scan, blood smear examination, and blood smear review. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33(1):1-7. doi:10.3343/alm.2013.33.1.1.

23. Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Perspective article: Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(5):585-601. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x.

24. Crane D, Everts P. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) matrix grafts. Pract Pain Manag. 2008;8(1):12-26.

25. Fortier LA, Barker JU, Strauss EJ, McCarrel TM, Cole BJ. The role of growth factors in cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2706-2715. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1857-3.

26. Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2135-2140. doi:10.1177/0363546511417792.

27. Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93(3):411-422.

28. Watelet JB, Demetter P, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Cuvelier C, Bachert C. Neutrophil-derived metalloproteinase-9 predicts healing quality after sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):56-61. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000150674.30237.3f.

29. Hauschild G, Geburek F, Gosheger G, et al. Short term storage stability at room temperature of two different platelet-rich plasma preparations from equine donors and potential impact on growth factor concentrations. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12917-016-0920-4.

30. Moore GW, Maloney JC, Archer RA, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for tissue regeneration can be stored at room temperature for at least five days. Br J Biomed Sci. 2017;74(2):71-77. doi:10.1080/09674845.2016.1233792.

31. McShine RL, Sibinga S, Brozovic B. Differences between the effects of EDTA and citrate anticoagulants on platelet count and mean platelet volume. Clin Lab Haematol. 1990;12(3):277-285.

1. Nikolidakis D, Jansen JA. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in oral surgery: Literature review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(3):249-258. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0062.

2. Sánchez AR, Sheridan PJ, Kupp LI. Is platelet-rich plasma the perfect enhancement factor? A current review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2003;18(1):93-103.

3. Monto RR. Platelet rich plasma treatment for chronic achilles tendinosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(5):379-385. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0379.

4. Owens RF, Ginnetti J, Conti SF, Latona C. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging outcomes following platelet rich plasma injection for chronic midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy. Foot ankle Int. 2011;32(11):1032-1039. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.1032.

5. Sánchez M, Anitua E, Azofra J, Andía I, Padilla S, Mujika I. Comparison of surgically repaired achilles tendon tears using platelet-rich fibrin matrices. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):245-251. doi:10.1177/0363546506294078.

6. Silva A, Sampaio R. Anatomic ACL reconstruction: does the platelet-rich plasma accelerate tendon healing? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(6):676-682. doi:10.1007/s00167-009-0762-8.

7. Fréchette JP, Martineau I, Gagnon G. Platelet-rich plasmas: growth factor content and roles in wound healing. J Dent Res. 2005;84(5):434-439. doi:10.1177/154405910508400507.

8. Bosch G, René van Weeren P, Barneveld A, van Schie HTM. Computerised analysis of standardised ultrasonographic images to monitor the repair of surgically created core lesions in equine superficial digital flexor tendons following treatment with intratendinous platelet rich plasma or placebo. Vet J. 2011;187(1):92-98. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.10.014.

9. Torricelli P, Fini M, Filardo G, et al. Regenerative medicine for the treatment of musculoskeletal overuse injuries in competition horses. Int Orthop. 2011;35(10):1569-1576. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1237-3.

10. Sampson S, Gerhardt M, Mandelbaum B. Platelet rich plasma injection grafts for musculoskeletal injuries: a review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1(3-4):165-174. doi:10.1007/s12178-008-9032-5.

11. Sheth U, Simunovic N, Klein G, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma use for orthopaedic indications: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):298-307. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00154.

12. Vannini F, Di Matteo B, Filardo G, Kon E, Marcacci M, Giannini S. Platelet-rich plasma for foot and ankle pathologies: a systematic review. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;20(1):2-9. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2013.08.001.

13. Boswell SG, Cole BJ, Sundman EA, Karas V, Fortier LA. Platelet-rich plasma: a milieu of bioactive factors. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(3):429-439. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2011.10.018.

14. Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MBR, Chowaniec DM, et al. Platelet-rich plasma differs according to preparation method and human variability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(4):308-316. doi:10.2106/JBJS.K.00430.

15. Castillo TN, Pouliot MA, Kim HJ, Dragoo JL. Comparison of growth factor and platelet concentration from commercial platelet-rich plasma separation systems. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):266-271. doi:10.1177/0363546510387517.

16. Arnoczky SP, Sheibani-Rad S, Shebani-Rad S. The basic science of platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what clinicians need to know. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2013;21(4):180-185. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182999712.

17. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Bielecki T, Corso M Del, Inchingolo F, Sammartino G. Shedding light in the controversial terminology for platelet-rich products: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), platelet-leukocyte gel (PLG), preparation rich in growth factors (PRGF), classification and commercialism. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2010;95A(4):1280-1282. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.32894.

18. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27(3):158-167. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009.

19. Everts PA, Knape JT, Weibrich G, et al. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: a review. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38(2):174-187.

20. Malok M, Titchener EH, Bridgers C, Lee BY, Bamberg R. Comparison of two platelet count estimation methodologies for peripheral blood smears. Clin Lab Sci. 2007;20(3):154-160.

21. Gulati G, Uppal G, Florea AD, Gong J. Detection of platelet clumps on peripheral blood smears by CellaVision DM96 System and Microscopic Review. Lab Med. 2014;45(4):368-371. doi:10.1309/LM604RQVKVLRFXOR.

22. Gulati G, Song J, Florea AD, Gong J. Purpose and criteria for blood smear scan, blood smear examination, and blood smear review. Ann Lab Med. 2013;33(1):1-7. doi:10.3343/alm.2013.33.1.1.

23. Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Perspective article: Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(5):585-601. doi:10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x.

24. Crane D, Everts P. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) matrix grafts. Pract Pain Manag. 2008;8(1):12-26.

25. Fortier LA, Barker JU, Strauss EJ, McCarrel TM, Cole BJ. The role of growth factors in cartilage repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2706-2715. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1857-3.

26. Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(10):2135-2140. doi:10.1177/0363546511417792.

27. Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, et al. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93(3):411-422.

28. Watelet JB, Demetter P, Claeys C, Van Cauwenberge P, Cuvelier C, Bachert C. Neutrophil-derived metalloproteinase-9 predicts healing quality after sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(1):56-61. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000150674.30237.3f.

29. Hauschild G, Geburek F, Gosheger G, et al. Short term storage stability at room temperature of two different platelet-rich plasma preparations from equine donors and potential impact on growth factor concentrations. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13(1):7. doi:10.1186/s12917-016-0920-4.

30. Moore GW, Maloney JC, Archer RA, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for tissue regeneration can be stored at room temperature for at least five days. Br J Biomed Sci. 2017;74(2):71-77. doi:10.1080/09674845.2016.1233792.

31. McShine RL, Sibinga S, Brozovic B. Differences between the effects of EDTA and citrate anticoagulants on platelet count and mean platelet volume. Clin Lab Haematol. 1990;12(3):277-285.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Blood can be stored at room temperature for up to 4 hours before making PRP without loss in activity.

- PRP can be stored at room temperature for up to 4 hours before administration to a patient without loss in activity.

- Manual, direct smear analysis is as accurate as automated counting for measuring platelet concentration in PRP.

Biceps Tenodesis: An Evolution of Treatment

Take-Home Points

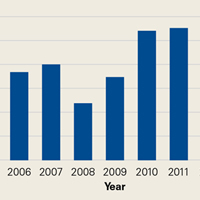

- The LHB tendon has been shown to be a significant pain generator in the shoulder.

- At our institution, the number of LHB tenodeses significantly increased from 2004 to 2014.

- The age of patients who underwent a LHB tenodesis did not change significantly over the study period.

- Furthermore, the percentage of shoulder procedures that involved a LHB tenodesis significantly increased over the study period.

- Biceps tenodesis has become a more common procedure to treat shoulder pathology.

Although the exact function of the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon is not completely understood, it is accepted that the LHB tendon can be a significant source of pain within the shoulder.1-4 Patients with symptoms related to biceps pathology often present with anterior shoulder pain that worsens with flexion and supination of the affected elbow and wrist.5 Although the sensitivity and specificity of physical examination maneuvers have been called into question, special tests have been developed to aid in the diagnosis of tendonitis of the LHB. These tests include the Speed, Yergason, bear hug, and uppercut tests as well as the O’Brien test (cross-body adduction).6,7 Recent studies have found LHB pathology in 45% of patients who undergo rotator cuff repair and in 63% of patients with a subscapularis tear.8,9

Pathology of the LHB tendon, including superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears, can be treated in many ways.5,10,11 Options include SLAP repair, biceps tenodesis, débridement, and biceps tenotomy.11,12 Results of SLAP repairs have been less than optimal, but biceps tenodesis has been effective, and avoids the issue of cramping as can be seen with biceps tenotomy and débridement.10,12,13 Surgical methods for biceps tenodesis include open subpectoral and all-arthroscopic.11,12 Both methods have had good, reliable outcomes, but the all-arthroscopic technique is relatively new.11,12,14We conducted a study to determine LHB tenodesis trends, including patient age at time of surgery. We used surgical data from fellowship-trained sports or shoulder/elbow orthopedic surgeons at a busy subspecialty-based shoulder orthopedic practice. We hypothesized that the rate of LHB tenodesis would increase significantly over time and that there would be no significant change in the age of patients who underwent LHB tenodesis.

Methods

Our Institutional Review Board exempted this study. To determine the number of LHB tenodesis procedures performed at our institution, overall and in comparison with other common arthroscopic shoulder procedures, we queried the surgical database of 4 fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons (shoulder/elbow, Drs. Nicholson and Cole; sports, Drs. Romeo and Verma) for the period January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2014. We used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 23430 to determine the number of LHB tenodesis cases, as the surgeons primarily perform an open subpectoral biceps tenodesis. Patient age at time of surgery and the date of surgery were recorded. All patients who underwent LHB tenodesis between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2014 were included. Number of procedures performed each year by each surgeon was recorded, as were concomitant procedures performed at the same time as the LHB tenodesis. To get the denominator (and reference point) for the number of arthroscopic shoulder surgeries performed by these 4 surgeons during the study period, and thereby determine the rate of LHB tenodesis, we selected the most common shoulder arthroscopy CPT codes used in our practice: 23430, 29806, 29807, 29822, 29823, 29825, 29826, and 29827. For a patient who underwent multiple procedures on the same day (multiple CPT codes entered on the same day), only one code was counted for that day. If 23430 was among the codes, it was included, and the case was placed in the numerator; if 23430 was not among the codes, the case was placed in the denominator.

The Arthroscopy Association of North America provides descriptions for the CPT codes: 23430 (tenodesis of long tendon of biceps), 29806 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; capsulorrhaphy), 29807 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; repair of SLAP lesion), 29822 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; débridement, limited), 29823 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; débridement, extensive), 29825 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with lysis and resection of adhesions, with or without manipulation), 29826 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; decompression of subacromial space with partial acromioplasty, with or without coracoacromial release), and 29827 (arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with rotator cuff repair).

For analysis, we divided the data into total number of arthroscopic shoulder procedures performed by each surgeon each year and number of LHB tenodesis procedures performed by each surgeon each year. Total number of patients who had an arthroscopic procedure was used to create a denominator, and number of LHB tenodesis procedures showed the percentage of arthroscopic shoulder surgery patients who underwent LHB tenodesis. (All patients who undergo biceps tenodesis also have, at the least, diagnostic shoulder arthroscopy with or without tenotomy; if the tendon is ruptured, tenotomy is unnecessary.)

Descriptive statistics were calculated as means (SDs) for continuous variables and as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Linear regression analysis was used to determine whether the number of LHB tenodesis procedures changed during the study period and whether patient age changed over time. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

Of the 7640 patients who underwent arthroscopic shoulder procedures between 2004 and 2014, 2125 had LHB tenodesis (CPT code 23430).

Discussion

Tenodesis has become a common treatment option for several pathologic shoulder conditions involving the LHB tendon.5 We set out to determine trends in LHB tenodesis at a subspecialty-focused shoulder orthopedic practice and hypothesized that the rate of LHB tenodesis would increase significantly over time and that there would be no significant change in the age of patients who underwent LHB tenodesis. Our hypotheses were confirmed: The number of LHB tenodesis cases increased significantly without a significant change in patient age.

Treatment options for LHB pathology and SLAP tears include simple tenotomy, débridement, open biceps tenodesis, and arthroscopic tenodesis.11,12,15

Recent evidence has called into question the results of SLAP repairs and suggested biceps tenodesis may be a better treatment option for SLAP tears.10,13,21 Studies have found excellent outcomes with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis in the treatment of SLAP tears, and others have found better restoration of pitchers’ thoracic rotation with open subpectoral biceps tenodesis than with SLAP repair.13,14 Similarly, comparison studies have largely favored biceps tenodesis over SLAP repair, particularly in patients older than 35 years to 40 years.22 Given these results, it is not surprising that, querying the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgeons (ABOS) part II database for isolated SLAP lesions treated between 2002 and 2011, Patterson and colleagues23 found the percentage of SLAP repairs decreased from 69.3% to 44.8% (P < .0001), whereas the percentage of biceps tenodesis procedures increased from 1.9% to 18.8% (P < .0001), indicating the realization of improved outcomes with LHB tenodesis in the treatment of SLAP tears. On the other hand, in the ABOS part II database for the period 2003 to 2008, Weber and colleagues24 found that, despite a decrease in the percentage of SLAP repairs, total number of SLAP repairs increased from 9.4% to 10.1% (P = .0163). According to our study results, the number of SLAP repairs is decreasing over time, whereas the number of LHB tenodesis procedures is continuing to rise. The practice patterns seen in our study correlate with those in previous studies of the treatment of SLAP tears: good results in tenodesis groups and poor results in SLAP repair groups.10,13Werner and colleagues25 recently used the large PearlDiver database, which includes information from both private payers and Medicare, to determine overall LHB tenodesis trends in the United States for the period 2008 to 2011. Over those years, the incidence of LHB tenodesis increased 1.7-fold, and the rate of arthroscopic LHB tenodesis increased significantly more than the rate of open LHB tenodesis. These results are similar to ours in that the number of LHB tenodesis cases increased significantly over time. However, as the overwhelming majority of patients in our practice undergo open biceps tenodesis, the faster rate of growth in the arthroscopic cohort relative to the open cohort cannot be assessed. Additional randomized studies comparing biceps tenodesis, both open and arthroscopic, with SLAP repair are needed to properly determine the superiority of LHB tenodesis over SLAP repair.