User login

5 Points on Meniscal Allograft Transplantation

ABSTRACT

Meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes when performed in properly indicated patients. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Existing pathology in the knee needs to be carefully considered and issues such as malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may require a staged or concomitant procedure. Once an ideal candidate is identified, graft selection and preparation are critical steps to ensure a proper fit and long-term viability of the meniscus. When selecting the graft, accurate measurements must be taken, and this is most commonly performed using plain radiographs for this. Graft fixation can be accomplished by placing vertical mattress sutures and tying those down with the knee in full extension.

Continue to: Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population...

Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population. In the United States alone, approximately 700,000 meniscectomies are performed annually.1 Given discouraging long-term clinical results following subtotal meniscectomy in young patients, meniscal repair is preferred whenever possible.2 Despite short-term symptom relief if subtotal meniscectomy is required, some patients often go on to develop localized pain in the affected compartment, effusions, and eventual development of osteoarthritis. In such patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency, meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes.3-5 Three recently published systematic reviews describe the outcomes of MAT in thousands of patients, noting positive outcomes in regard to pain and function for the majority of patients.6-8 Specifically, in a review conducted by Elattar and colleagues7 consisting of 44 studies comprising 1136 grafts in 1068 patients, the authors reported clinical improvement in Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale score (44 to 77), visual analog scale (48 mm to 17 mm), and International Knee Documentation Committee (84% normal/nearly normal, 89% satisfaction), among other outcomes measures. Additionally, the complication (21.3%) and failure rates (10.6%) were considered acceptable by all authors. The purpose of this article is to review indications, operative preparation, critical aspects of surgical technique, and additional concomitant procedures commonly performed alongside MAT.

1. PATIENT SELECTION

When used with the proper indications, MAT offers improved functional outcomes and reduced pain for patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency who does not have (1) evidence of diffuse osteoarthritis (Outerbridge grade <2), including the absence of significant bony flattening or osteophytes in the involved compartment; (2) inflammatory arthritis; (3) active or previous joint infection; (4) mechanical axis malalignment; or (5) morbid obesity (Table). Long-leg weight-bearing anterior-posterior alignment radiographs are important in the work-up of any patient being considered for MAT, and consideration for concomitant or staged realignment high tibial osteotomy (HTO) or distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) should be given for patients in excessive varus or valgus, respectively. Although the decision to perform a realignment osteotomy is made on a patient-specific basis, if the weight-bearing line passes medial to the medial tibial spine or lateral to the lateral tibial spine, HTO or DFO, respectively, should be considered. Importantly, MAT is not typically recommended in the asymptomatic patient.9 Although some recent evidence suggests MAT may have chondroprotective effects on articular cartilage following meniscectomy, there is insufficient long-term outcome data to support the use of MAT as a prophylactic measure, especially given the fact that graft deterioration inevitably occurs at 7 to 10 years, with patients having to consider avoiding meniscus-dependent activities following transplant to protect their graft from traumatic failure.10,11

Table. Summary of Indications and Contraindications for Meniscal Allograft Transplant (MAT)

Indications | Contraindicationsa |

Patients younger than 50 years old with a chief complaint of pain limiting their desired activities | Diffuse femoral and/or tibial articular cartilage wear |

Body mass index <35 kg/m2 | Radiographic evidence of arthritis |

Previous meniscectomy (or non-viable meniscus state) with pain localized to the affected compartment | Inflammatory arthritis conditions |

Normal or correctable coronal and sagittal alignment | MAT performed as a prophylactic measure in the absence of appropriate symptoms is highly controversial |

Normal or correctable ligamentous stability |

|

Normal or correctable articular cartilage |

|

Willingness to comply with rehabilitation protocol |

|

Realistic post-surgical activity expectations |

|

aContraindications for MAT are controversial, as the available literature discussing contraindications is very limited. This list is based on the experience of the senior author.

Long-term prospective studies have shown high graft survival and predominantly positive functional results after MAT. Age indications have expanded, with 1 recent study reporting 6% reoperation rate and zero failures in a cohort of 37 adolescent MAT patients.12 High survival rates hold even among an athletic population, where rates of return to play after MAT have been reported to be >75% for those competing at a high school level or higher.13 In an active military population, <2% of patients progressed to revision MAT or total knee arthroplasty at minimum 2-year follow-up, but 22% of patients were unable to return to military duty owing to residual knee limitations.14 In this series, tobacco use correlated with failure, whereas MAT by high-volume, fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons decreased rates of failure.

2. GRAFT SELECTION

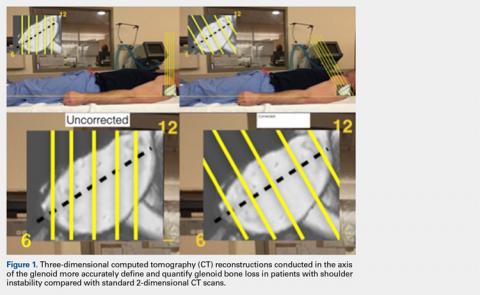

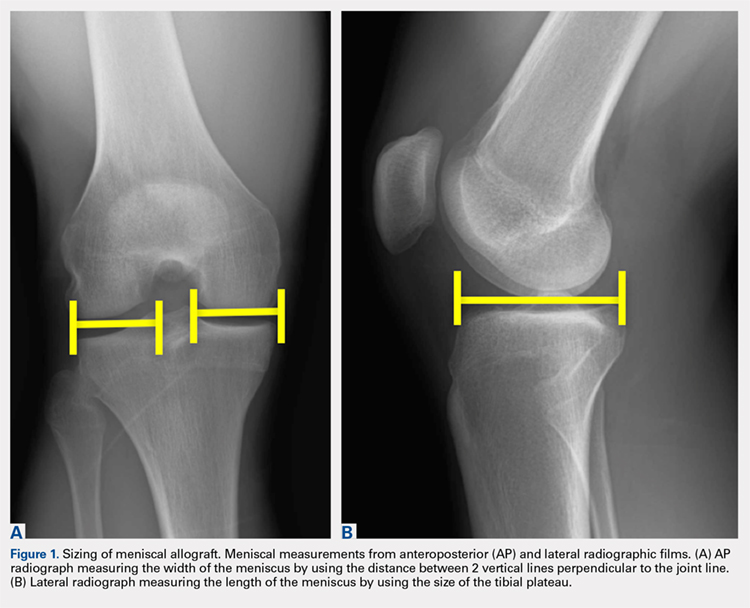

In preparation for MAT, accurate measurements must be taken for appropriate size matching. Several measurement techniques have been described, including using plain radiographs, 3D computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).15-18 There is limited data regarding the consequences of an improperly sized donor meniscus; however, an oversized lateral meniscus has been shown to increase the contact forces across the articular cartilage.19 Additionally, an undersized allograft may result in normal forces across the articular cartilage but greater forces across the meniscus.19

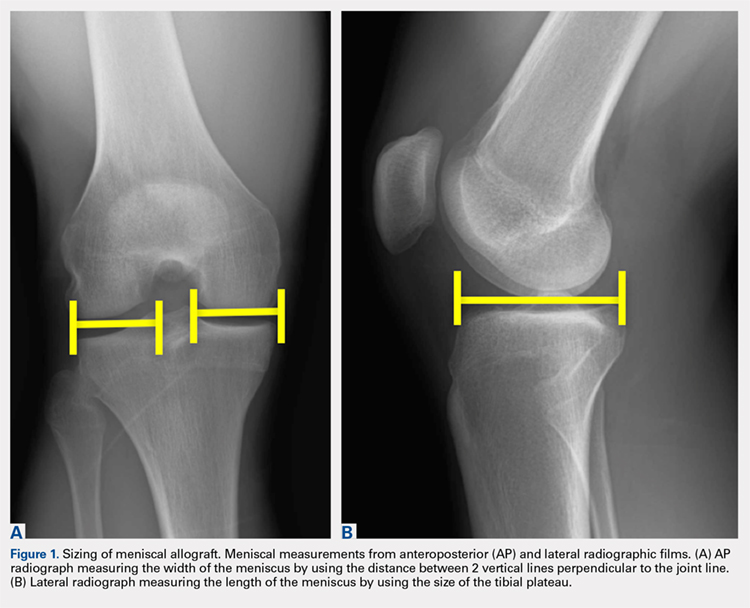

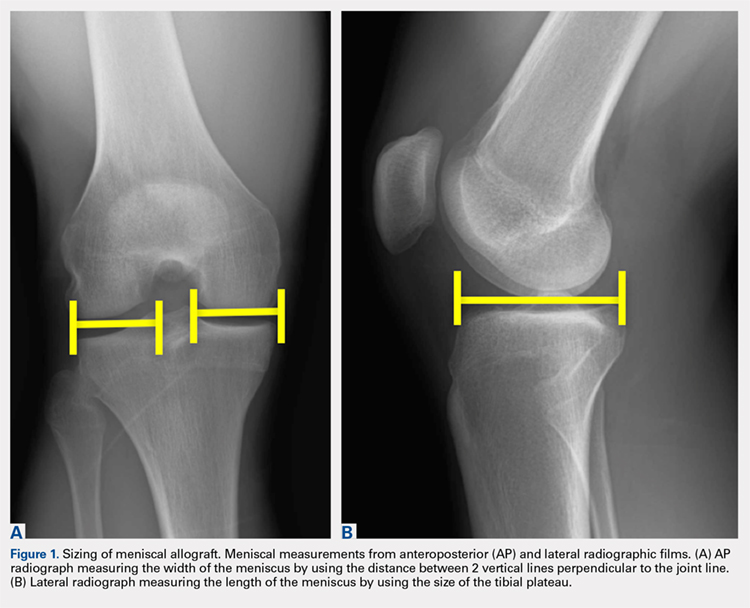

When sizing the recipient knee for MAT, accurate width and length measurements are critical. The most common technique used today includes measurements using anteroposterior and lateral radiographic images as described by Pollard and colleagues.15 The width of the meniscus is determined by the distance between 2 vertical lines perpendicular to the joint line, 1 of them tangential to the margin of the tibia metaphysis and the other between the medial and lateral tibial eminence in both knees (Figures 1A,1B). The length of the meniscus is measured on a lateral radiograph. A line is drawn at the level of the articular line between the anterior surface of the tibia above the tuberosity and a parallel line that is tangential to the posterior margin of the tibial plateau. Percent corrections are performed for these dimensions as described in previous publications.

Other techniques have been described to obtain accurate measurements of the recipient knee. For example, obtaining an MRI of the contralateral knee may provide a reproducible method of measuring both the width and length of the medial and lateral menisci.20 CT has been used to measure the lateral meniscus independently, and it has been shown to exhibit less error in the measure of the tibial plateau when compared with X-rays.18 Both CT and MRI are more expensive than simple radiographs, and CT exposes the patient to an increased amount of radiation. Current evidence does not support standard use of these advanced imaging modalities for meniscal sizing.

Continue to: GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT...

3. GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT

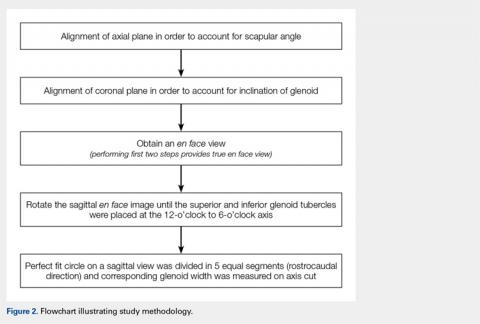

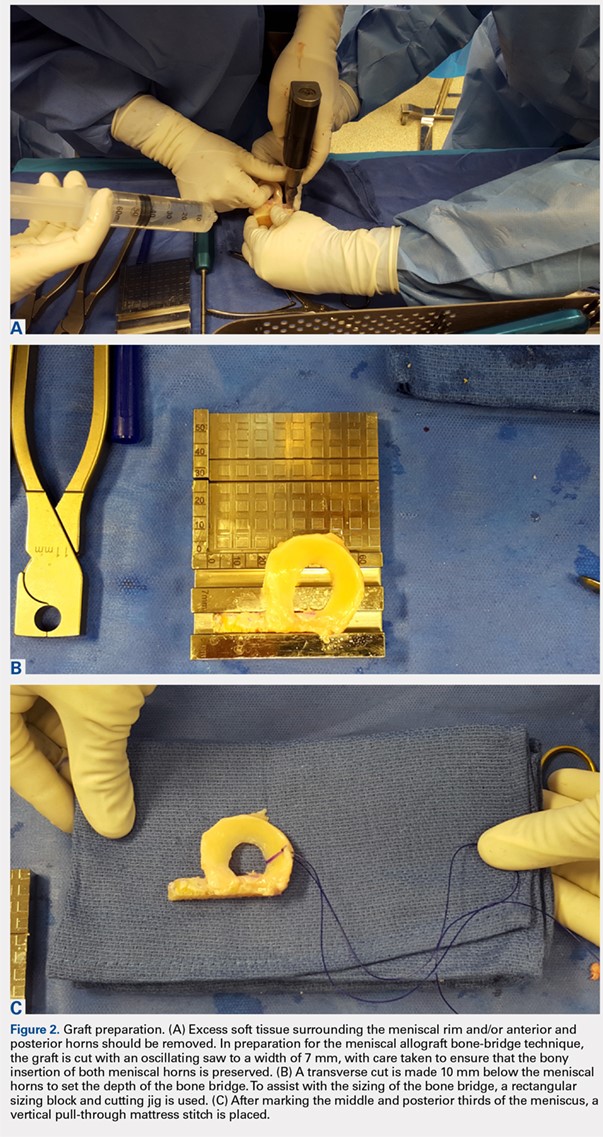

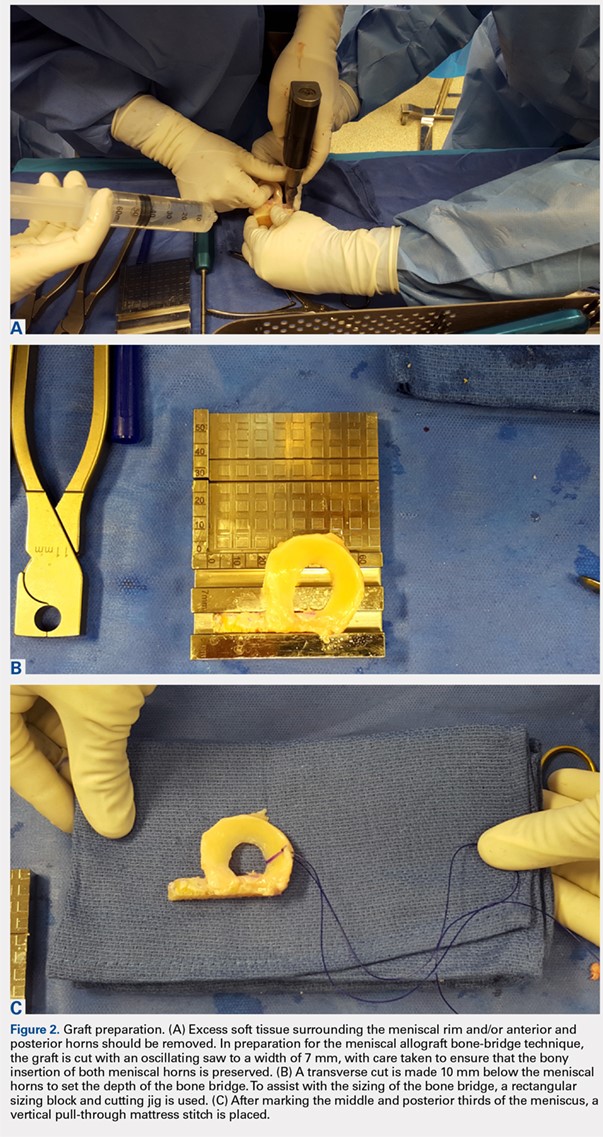

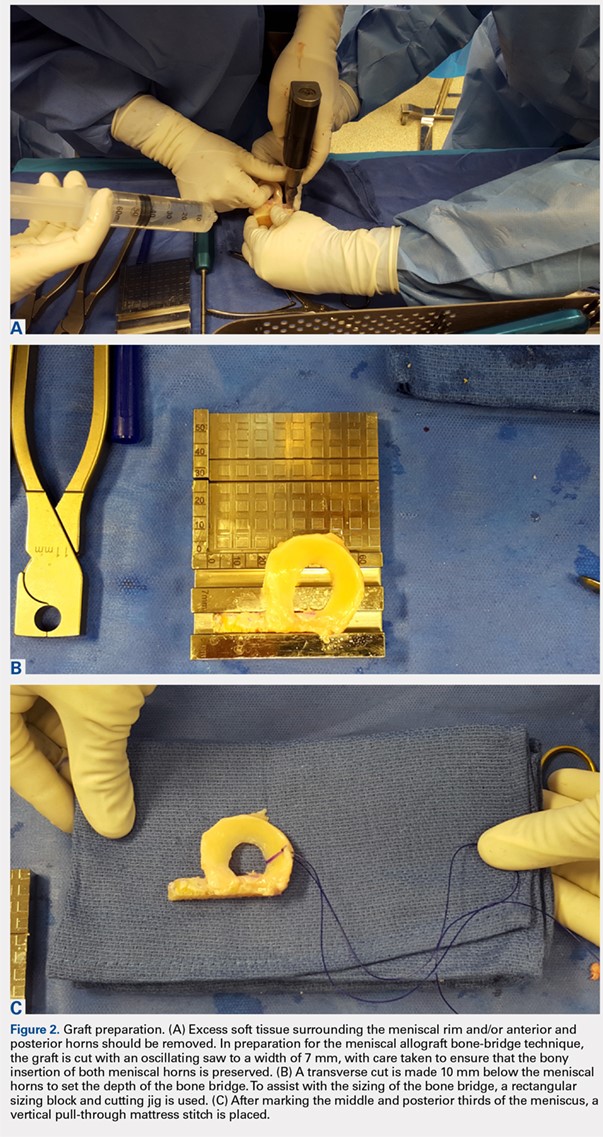

At the time of surgery, the meniscus allograft is thawed in sterile saline and prepared on the back table. This can be done before or after the diagnostic arthroscopy and bone-slot preparation. Excess soft tissue surrounding the meniscal rim and/or anterior and posterior horns should be removed. Several techniques for MAT have been described, but we generally prefer a bridge-in-slot technique for both medial and lateral MAT.21 To prepare the meniscus allograft for a bridge-in-slot technique, the graft is cut with an oscillating saw to a width of 7 mm, with care taken to ensure that the bony insertions of both meniscal horns are preserved. Next, a transverse cut is made 10 mm below the meniscal horns to set the depth of the bone bridge. To assist with the sizing of the bone bridge, a rectangular sizing block and cutting jig is used (Figures 2A-2C). After marking the middle and posterior thirds of the meniscus, a No. 2 non-absorbable suture is placed at the junction of the posterior and middle thirds of the meniscus. This completes preparation of the allograft prior to implantation.

Attention is then turned to back the arthroscopy. A standard posteromedial (medial meniscus) or posterolateral (lateral meniscus) accessory incision is made, and a Henning retractor is carefully placed in order to receive the sutures that will be placed through the meniscus allograft via a standard inside-out repair technique. First, a zone-specific cannula is used to place a nitinol wire out the accessory incision. The looped end of the wire is pulled out of the anterior arthrotomy incision that will be used to shuttle the meniscus allograft into the joint. In order to pass the meniscal allograft into the joint, the passing suture previously placed through the meniscus is shuttled through the nitinol wire, and the wire is then pulled out the accessory incision, advancing the meniscus through the anteiror arthrotomy. As the meniscus is introduced, the traction suture is then gently tensioned to get the allograft completely into the joint. Next, the bone bridge is seated into the previously created bone slot, as the soft tissue component is manually pushed beneath the ipsilateral femoral condyle. Under direct visualization, the soft tissue component is reduced with a probe using firm, constant traction. To aid in reduction, it may be useful to apply compartment-specific varus or valgus stress and to cycle the knee once the meniscal complex is reduced.

4. GRAFT FIXATION

Once the graft has been passed completely into the joint, with the bone bridge seated into the bone slot, the long end of an Army-Navy retractor is placed firmly through the arthrotomy on the meniscal bone bridge, maintaining a downward force to allow the bridge to remain slotted. To lever down on the posterior aspect of the graft, a freer elevator is used from anterosuperior to posteroinferior. The bone bridge is then secured using a bioabsorbable interference screw, placed central to the bone bridge opposing the block to the ipsilateral compartment. The remainder of the meniscus is secured with an inside-out repair technique, working from posterior to anterior through a standard medial or lateral meniscal repair approach. In total, approximately 6 to 10 vertical mattress sutures are placed, and these can be placed both superiorly and inferiorly on the meniscus. Posteriorly, an all-inside suture repair device may be helpful. Finally, the anterior aspect of the meniscus is repaired to the capsule in an open fashion prior to closing the arthrotomy. Sutures are tied with the leg in extension. The meniscal repair incision is closed in a standard fashion using layers.

5. CONCOMITANT PATHOLOGY AND MAT

The presence of concomitant knee pathology in the context of meniscus deficiency is a challenging problem that requires careful attention to all aspects of the underlying condition of the knee. In cases where MAT is indicated, issues of malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may also need to be addressed either concomitantly or in staged fashion. For example, medial meniscal deficiency in the setting of varus alignment can be addressed with a concomitant HTO, whereas lateral meniscal deficiency in the setting of valgus malalignment can be addressed with a concomitant DFO. In both cases, the osteotomy corrects an abnormal mechanical axis, offloading the diseased compartment. This accomplishes 2 goals, namely to preserve the new MAT graft and to protect underlying articular cartilage.22-24 The osteotomy is an important contributor to additional pain relief by offloading the compartment, and clinical studies have demonstrated that failure to address malalignment in the setting of surgical intervention for cartilage and meniscal insufficiency leads to inferior clinical outcomes and poor survival of transplanted tissue.25-28

Continue to: In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions...

In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions (Outerbridge grade 3 or 4), concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration should be considered. Depending on the size and location of the chondral lesion, options include marrow stimulation, autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, as well as chondral and/or osteochondral allograft transplantation. In a systematic review of concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration procedures, Harris and colleagues25 found that failure rates of the combined surgery were similar to those of either surgery in isolation.

Young athletes sustaining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears commonly also have meniscal pathology that must be addressed. Most cases are treated with meniscal repair or partial meniscectomy, but occasionally patients present with ACL tear and symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Specifically, MAT survival relies largely on a knee with ligamentous stability, whereas outcomes of ACL reconstruction are improved with intact and functional menisci.29 The surgical technique for MAT is modified slightly in the setting of performing a concomitant ACL reconstruction, with the ACL tibial tunnel drilled to avoid the meniscal bone slot if possible, followed by femoral tunnel creation. Femoral fixation of the ACL graft is accomplished after preparation of the meniscal slot. The meniscal graft is set into place (sutures are not yet tied), and tibial fixation of the ACL graft is performed next. We typically use an Achilles allograft for the ACL reconstruction, with the bone block used for femoral fixation to avoid bony impingement between the MAT bone bridge/block and the ACL graft. With the knee in full extension, the MAT sutures are tied at the conclusion of the surgical procedure. Concomitant MAT and ACL reconstruction has yielded positive long-term clinical outcomes, improved joint stability, and findings similar to historical results of ACL reconstruction or MAT performed in isolation.30,31

CONCLUSION

When used with the proper indications, MAT has demonstrated the ability to restore function and reduce pain. Successful meniscal transplant requires attention to the patient’s past medical and surgical history. Similarly, care must be taken to address any concomitant knee pathology, such as coronal realignment, ligament reconstruction, or cartilage restoration.

1. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;11(11):1-25.

2. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339. doi:10.1177/0363546513495641.

3. Saltzman BM, Bajaj S, Salata M, et al. Prospective long-term evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation procedure: a minimum of 7-year follow-up. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(2):165-175. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1313738.

4. van der Wal RJ, Thomassen BJ, van Arkel ER. Long-term clinical outcome of open meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2134-2139. doi:10.1177/0363546509336725.

5. Vundelinckx B, Vanlauwe J, Bellemans J. Long-term subjective, clinical, and radiographic outcome evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation in the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1592-1599. doi:10.1177/0363546514530092.

6. Hergan D, Thut D, Sherman O, Day MS. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):101-112. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.05.019.

7. Elattar M, Dhollander A, Verdonk R, Almqvist KF, Verdonk P. Twenty-six years of meniscal allograft transplantation: is it still experimental? A meta-analysis of 44 trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):147-157. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1351-6.

8. Verdonk R, Volpi P, Verdonk P, et al. Indications and limits of meniscal allografts. Injury. 2013;44(Suppl 1):S21-S27. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(13)70006-8.

9. Frank RM, Yanke A, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: letter to the editor. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):NP8-NP9. doi:10.1177/0363546515571065.

10. Aagaard H, Jørgensen U, Bojsen-Møller F. Immediate versus delayed meniscal allograft transplantation in sheep. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406(406):218-227. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000030066.92399.7f.

11. Jiang D, Ao YF, Gong X, Wang YJ, Zheng ZZ, Yu JK. Comparative study on immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: 4- to 6-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2329-2337. doi:10.1177/0363546514541653.

12. Riboh JC, Tilton AK, Cvetanovich GL, Campbell KA, Cole BJ. Meniscal allograft transplantation in the adolescent population. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):1133-1140.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.11.041.

13. Chalmers PN, Karas V, Sherman SL, Cole BJ. Return to high-level sport after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):539-544. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.027.

14. Waterman BR, Rensing N, Cameron KL, Owens BD, Pallis M. Survivorship of meniscal allograft transplantation in an athletic patient population. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1237-1242. doi:10.1177/0363546515626184.

15. Pollard ME, Kang Q, Berg EE. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):684-687. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(95)90110-8.

16. Haut TL, Hull ML, Howell SM. Use of roentgenography and magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal geometry determined with a three-dimensional coordinate digitizing system. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(2):228-237. doi:10.1002/jor.1100180210.

17. Van Thiel GS, Verma N, Yanke A, Basu S, Farr J, Cole B. Meniscal allograft size can be predicted by height, weight, and gender. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(7):722-727. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.01.004.

18. McConkey M, Lyon C, Bennett DL, et al. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation using 3-D CT reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(3):221-225. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1292651.

19. Dienst M, Greis PE, Ellis BJ, Bachus KN, Burks RT. Effect of lateral meniscal allograft sizing on contact mechanics of the lateral tibial plateau: an experimental study in human cadaveric knee joints. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(1):34-42. doi:10.1177/0363546506291404.

20. Yoon JR, Jeong HI, Seo MJ, et al. The use of contralateral knee magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal size during meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(10):1287-1293. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.009.

21. Lee AS, Kang RW, Kroin E, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Allograft meniscus transplantation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):106-114. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e318246f005.

22. Agneskirchner JD, Hurschler C, Wrann CD, Lobenhoffer P. The effects of valgus medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy on articular cartilage pressure of the knee: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(8):852-861. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.018.

23. Loening AM, James IE, Levenston ME, et al. Injurious mechanical compression of bovine articular cartilage induces chondrocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381(2):205-212. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.1988.

24. Mina C, Garrett WE Jr, Pietrobon R, Glisson R, Higgins L. High tibial osteotomy for unloading osteochondral defects in the medial compartment of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):949-955. doi:10.1177/0363546508315471.

25. Harris JD, Cavo M, Brophy R, Siston R, Flanigan D. Biological knee reconstruction: a systematic review of combined meniscal allograft transplantation and cartilage repair or restoration. Arthroscopy: 2011;27(3):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.007.

26. Rue JP, Yanke AB, Busam ML, McNickle AG, Cole BJ. Prospective evaluation of concurrent meniscus transplantation and articular cartilage repair: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1770-1778. doi:10.1177/0363546508317122.

27. Kazi HA, Abdel-Rahman W, Brady PA, Cameron JC. Meniscal allograft with or without osteotomy: a 15-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):303-309. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-3291-z.

28. Verdonk PC, Verstraete KL, Almqvist KF, et al. Meniscal allograft transplantation: long-term clinical results with radiological and magnetic resonance imaging correlations. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):694-706. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0033-2.

29. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery. Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):446-452. doi:10.1177/03635465000280040201.

30. Graf KW Jr, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Long-term results after combined medial meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: minimum 8.5-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(2):129-140. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.032.

31. Binnet MS, Akan B, Kaya A. Lyophilised medial meniscus transplantations in ACL-deficient knees: a 19-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(1):109-113. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1556-3.

ABSTRACT

Meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes when performed in properly indicated patients. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Existing pathology in the knee needs to be carefully considered and issues such as malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may require a staged or concomitant procedure. Once an ideal candidate is identified, graft selection and preparation are critical steps to ensure a proper fit and long-term viability of the meniscus. When selecting the graft, accurate measurements must be taken, and this is most commonly performed using plain radiographs for this. Graft fixation can be accomplished by placing vertical mattress sutures and tying those down with the knee in full extension.

Continue to: Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population...

Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population. In the United States alone, approximately 700,000 meniscectomies are performed annually.1 Given discouraging long-term clinical results following subtotal meniscectomy in young patients, meniscal repair is preferred whenever possible.2 Despite short-term symptom relief if subtotal meniscectomy is required, some patients often go on to develop localized pain in the affected compartment, effusions, and eventual development of osteoarthritis. In such patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency, meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes.3-5 Three recently published systematic reviews describe the outcomes of MAT in thousands of patients, noting positive outcomes in regard to pain and function for the majority of patients.6-8 Specifically, in a review conducted by Elattar and colleagues7 consisting of 44 studies comprising 1136 grafts in 1068 patients, the authors reported clinical improvement in Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale score (44 to 77), visual analog scale (48 mm to 17 mm), and International Knee Documentation Committee (84% normal/nearly normal, 89% satisfaction), among other outcomes measures. Additionally, the complication (21.3%) and failure rates (10.6%) were considered acceptable by all authors. The purpose of this article is to review indications, operative preparation, critical aspects of surgical technique, and additional concomitant procedures commonly performed alongside MAT.

1. PATIENT SELECTION

When used with the proper indications, MAT offers improved functional outcomes and reduced pain for patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency who does not have (1) evidence of diffuse osteoarthritis (Outerbridge grade <2), including the absence of significant bony flattening or osteophytes in the involved compartment; (2) inflammatory arthritis; (3) active or previous joint infection; (4) mechanical axis malalignment; or (5) morbid obesity (Table). Long-leg weight-bearing anterior-posterior alignment radiographs are important in the work-up of any patient being considered for MAT, and consideration for concomitant or staged realignment high tibial osteotomy (HTO) or distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) should be given for patients in excessive varus or valgus, respectively. Although the decision to perform a realignment osteotomy is made on a patient-specific basis, if the weight-bearing line passes medial to the medial tibial spine or lateral to the lateral tibial spine, HTO or DFO, respectively, should be considered. Importantly, MAT is not typically recommended in the asymptomatic patient.9 Although some recent evidence suggests MAT may have chondroprotective effects on articular cartilage following meniscectomy, there is insufficient long-term outcome data to support the use of MAT as a prophylactic measure, especially given the fact that graft deterioration inevitably occurs at 7 to 10 years, with patients having to consider avoiding meniscus-dependent activities following transplant to protect their graft from traumatic failure.10,11

Table. Summary of Indications and Contraindications for Meniscal Allograft Transplant (MAT)

Indications | Contraindicationsa |

Patients younger than 50 years old with a chief complaint of pain limiting their desired activities | Diffuse femoral and/or tibial articular cartilage wear |

Body mass index <35 kg/m2 | Radiographic evidence of arthritis |

Previous meniscectomy (or non-viable meniscus state) with pain localized to the affected compartment | Inflammatory arthritis conditions |

Normal or correctable coronal and sagittal alignment | MAT performed as a prophylactic measure in the absence of appropriate symptoms is highly controversial |

Normal or correctable ligamentous stability |

|

Normal or correctable articular cartilage |

|

Willingness to comply with rehabilitation protocol |

|

Realistic post-surgical activity expectations |

|

aContraindications for MAT are controversial, as the available literature discussing contraindications is very limited. This list is based on the experience of the senior author.

Long-term prospective studies have shown high graft survival and predominantly positive functional results after MAT. Age indications have expanded, with 1 recent study reporting 6% reoperation rate and zero failures in a cohort of 37 adolescent MAT patients.12 High survival rates hold even among an athletic population, where rates of return to play after MAT have been reported to be >75% for those competing at a high school level or higher.13 In an active military population, <2% of patients progressed to revision MAT or total knee arthroplasty at minimum 2-year follow-up, but 22% of patients were unable to return to military duty owing to residual knee limitations.14 In this series, tobacco use correlated with failure, whereas MAT by high-volume, fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons decreased rates of failure.

2. GRAFT SELECTION

In preparation for MAT, accurate measurements must be taken for appropriate size matching. Several measurement techniques have been described, including using plain radiographs, 3D computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).15-18 There is limited data regarding the consequences of an improperly sized donor meniscus; however, an oversized lateral meniscus has been shown to increase the contact forces across the articular cartilage.19 Additionally, an undersized allograft may result in normal forces across the articular cartilage but greater forces across the meniscus.19

When sizing the recipient knee for MAT, accurate width and length measurements are critical. The most common technique used today includes measurements using anteroposterior and lateral radiographic images as described by Pollard and colleagues.15 The width of the meniscus is determined by the distance between 2 vertical lines perpendicular to the joint line, 1 of them tangential to the margin of the tibia metaphysis and the other between the medial and lateral tibial eminence in both knees (Figures 1A,1B). The length of the meniscus is measured on a lateral radiograph. A line is drawn at the level of the articular line between the anterior surface of the tibia above the tuberosity and a parallel line that is tangential to the posterior margin of the tibial plateau. Percent corrections are performed for these dimensions as described in previous publications.

Other techniques have been described to obtain accurate measurements of the recipient knee. For example, obtaining an MRI of the contralateral knee may provide a reproducible method of measuring both the width and length of the medial and lateral menisci.20 CT has been used to measure the lateral meniscus independently, and it has been shown to exhibit less error in the measure of the tibial plateau when compared with X-rays.18 Both CT and MRI are more expensive than simple radiographs, and CT exposes the patient to an increased amount of radiation. Current evidence does not support standard use of these advanced imaging modalities for meniscal sizing.

Continue to: GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT...

3. GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT

At the time of surgery, the meniscus allograft is thawed in sterile saline and prepared on the back table. This can be done before or after the diagnostic arthroscopy and bone-slot preparation. Excess soft tissue surrounding the meniscal rim and/or anterior and posterior horns should be removed. Several techniques for MAT have been described, but we generally prefer a bridge-in-slot technique for both medial and lateral MAT.21 To prepare the meniscus allograft for a bridge-in-slot technique, the graft is cut with an oscillating saw to a width of 7 mm, with care taken to ensure that the bony insertions of both meniscal horns are preserved. Next, a transverse cut is made 10 mm below the meniscal horns to set the depth of the bone bridge. To assist with the sizing of the bone bridge, a rectangular sizing block and cutting jig is used (Figures 2A-2C). After marking the middle and posterior thirds of the meniscus, a No. 2 non-absorbable suture is placed at the junction of the posterior and middle thirds of the meniscus. This completes preparation of the allograft prior to implantation.

Attention is then turned to back the arthroscopy. A standard posteromedial (medial meniscus) or posterolateral (lateral meniscus) accessory incision is made, and a Henning retractor is carefully placed in order to receive the sutures that will be placed through the meniscus allograft via a standard inside-out repair technique. First, a zone-specific cannula is used to place a nitinol wire out the accessory incision. The looped end of the wire is pulled out of the anterior arthrotomy incision that will be used to shuttle the meniscus allograft into the joint. In order to pass the meniscal allograft into the joint, the passing suture previously placed through the meniscus is shuttled through the nitinol wire, and the wire is then pulled out the accessory incision, advancing the meniscus through the anteiror arthrotomy. As the meniscus is introduced, the traction suture is then gently tensioned to get the allograft completely into the joint. Next, the bone bridge is seated into the previously created bone slot, as the soft tissue component is manually pushed beneath the ipsilateral femoral condyle. Under direct visualization, the soft tissue component is reduced with a probe using firm, constant traction. To aid in reduction, it may be useful to apply compartment-specific varus or valgus stress and to cycle the knee once the meniscal complex is reduced.

4. GRAFT FIXATION

Once the graft has been passed completely into the joint, with the bone bridge seated into the bone slot, the long end of an Army-Navy retractor is placed firmly through the arthrotomy on the meniscal bone bridge, maintaining a downward force to allow the bridge to remain slotted. To lever down on the posterior aspect of the graft, a freer elevator is used from anterosuperior to posteroinferior. The bone bridge is then secured using a bioabsorbable interference screw, placed central to the bone bridge opposing the block to the ipsilateral compartment. The remainder of the meniscus is secured with an inside-out repair technique, working from posterior to anterior through a standard medial or lateral meniscal repair approach. In total, approximately 6 to 10 vertical mattress sutures are placed, and these can be placed both superiorly and inferiorly on the meniscus. Posteriorly, an all-inside suture repair device may be helpful. Finally, the anterior aspect of the meniscus is repaired to the capsule in an open fashion prior to closing the arthrotomy. Sutures are tied with the leg in extension. The meniscal repair incision is closed in a standard fashion using layers.

5. CONCOMITANT PATHOLOGY AND MAT

The presence of concomitant knee pathology in the context of meniscus deficiency is a challenging problem that requires careful attention to all aspects of the underlying condition of the knee. In cases where MAT is indicated, issues of malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may also need to be addressed either concomitantly or in staged fashion. For example, medial meniscal deficiency in the setting of varus alignment can be addressed with a concomitant HTO, whereas lateral meniscal deficiency in the setting of valgus malalignment can be addressed with a concomitant DFO. In both cases, the osteotomy corrects an abnormal mechanical axis, offloading the diseased compartment. This accomplishes 2 goals, namely to preserve the new MAT graft and to protect underlying articular cartilage.22-24 The osteotomy is an important contributor to additional pain relief by offloading the compartment, and clinical studies have demonstrated that failure to address malalignment in the setting of surgical intervention for cartilage and meniscal insufficiency leads to inferior clinical outcomes and poor survival of transplanted tissue.25-28

Continue to: In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions...

In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions (Outerbridge grade 3 or 4), concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration should be considered. Depending on the size and location of the chondral lesion, options include marrow stimulation, autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, as well as chondral and/or osteochondral allograft transplantation. In a systematic review of concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration procedures, Harris and colleagues25 found that failure rates of the combined surgery were similar to those of either surgery in isolation.

Young athletes sustaining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears commonly also have meniscal pathology that must be addressed. Most cases are treated with meniscal repair or partial meniscectomy, but occasionally patients present with ACL tear and symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Specifically, MAT survival relies largely on a knee with ligamentous stability, whereas outcomes of ACL reconstruction are improved with intact and functional menisci.29 The surgical technique for MAT is modified slightly in the setting of performing a concomitant ACL reconstruction, with the ACL tibial tunnel drilled to avoid the meniscal bone slot if possible, followed by femoral tunnel creation. Femoral fixation of the ACL graft is accomplished after preparation of the meniscal slot. The meniscal graft is set into place (sutures are not yet tied), and tibial fixation of the ACL graft is performed next. We typically use an Achilles allograft for the ACL reconstruction, with the bone block used for femoral fixation to avoid bony impingement between the MAT bone bridge/block and the ACL graft. With the knee in full extension, the MAT sutures are tied at the conclusion of the surgical procedure. Concomitant MAT and ACL reconstruction has yielded positive long-term clinical outcomes, improved joint stability, and findings similar to historical results of ACL reconstruction or MAT performed in isolation.30,31

CONCLUSION

When used with the proper indications, MAT has demonstrated the ability to restore function and reduce pain. Successful meniscal transplant requires attention to the patient’s past medical and surgical history. Similarly, care must be taken to address any concomitant knee pathology, such as coronal realignment, ligament reconstruction, or cartilage restoration.

ABSTRACT

Meniscus allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes when performed in properly indicated patients. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Existing pathology in the knee needs to be carefully considered and issues such as malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may require a staged or concomitant procedure. Once an ideal candidate is identified, graft selection and preparation are critical steps to ensure a proper fit and long-term viability of the meniscus. When selecting the graft, accurate measurements must be taken, and this is most commonly performed using plain radiographs for this. Graft fixation can be accomplished by placing vertical mattress sutures and tying those down with the knee in full extension.

Continue to: Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population...

Meniscus tears are common in the young, athletic patient population. In the United States alone, approximately 700,000 meniscectomies are performed annually.1 Given discouraging long-term clinical results following subtotal meniscectomy in young patients, meniscal repair is preferred whenever possible.2 Despite short-term symptom relief if subtotal meniscectomy is required, some patients often go on to develop localized pain in the affected compartment, effusions, and eventual development of osteoarthritis. In such patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency, meniscal allograft transplantation (MAT) has yielded excellent long-term functional outcomes.3-5 Three recently published systematic reviews describe the outcomes of MAT in thousands of patients, noting positive outcomes in regard to pain and function for the majority of patients.6-8 Specifically, in a review conducted by Elattar and colleagues7 consisting of 44 studies comprising 1136 grafts in 1068 patients, the authors reported clinical improvement in Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale score (44 to 77), visual analog scale (48 mm to 17 mm), and International Knee Documentation Committee (84% normal/nearly normal, 89% satisfaction), among other outcomes measures. Additionally, the complication (21.3%) and failure rates (10.6%) were considered acceptable by all authors. The purpose of this article is to review indications, operative preparation, critical aspects of surgical technique, and additional concomitant procedures commonly performed alongside MAT.

1. PATIENT SELECTION

When used with the proper indications, MAT offers improved functional outcomes and reduced pain for patients with symptomatic meniscal deficiency. When evaluating a patient for potential MAT, it is imperative to evaluate past medical history and past surgical procedures. The ideal MAT candidate is a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency who does not have (1) evidence of diffuse osteoarthritis (Outerbridge grade <2), including the absence of significant bony flattening or osteophytes in the involved compartment; (2) inflammatory arthritis; (3) active or previous joint infection; (4) mechanical axis malalignment; or (5) morbid obesity (Table). Long-leg weight-bearing anterior-posterior alignment radiographs are important in the work-up of any patient being considered for MAT, and consideration for concomitant or staged realignment high tibial osteotomy (HTO) or distal femoral osteotomy (DFO) should be given for patients in excessive varus or valgus, respectively. Although the decision to perform a realignment osteotomy is made on a patient-specific basis, if the weight-bearing line passes medial to the medial tibial spine or lateral to the lateral tibial spine, HTO or DFO, respectively, should be considered. Importantly, MAT is not typically recommended in the asymptomatic patient.9 Although some recent evidence suggests MAT may have chondroprotective effects on articular cartilage following meniscectomy, there is insufficient long-term outcome data to support the use of MAT as a prophylactic measure, especially given the fact that graft deterioration inevitably occurs at 7 to 10 years, with patients having to consider avoiding meniscus-dependent activities following transplant to protect their graft from traumatic failure.10,11

Table. Summary of Indications and Contraindications for Meniscal Allograft Transplant (MAT)

Indications | Contraindicationsa |

Patients younger than 50 years old with a chief complaint of pain limiting their desired activities | Diffuse femoral and/or tibial articular cartilage wear |

Body mass index <35 kg/m2 | Radiographic evidence of arthritis |

Previous meniscectomy (or non-viable meniscus state) with pain localized to the affected compartment | Inflammatory arthritis conditions |

Normal or correctable coronal and sagittal alignment | MAT performed as a prophylactic measure in the absence of appropriate symptoms is highly controversial |

Normal or correctable ligamentous stability |

|

Normal or correctable articular cartilage |

|

Willingness to comply with rehabilitation protocol |

|

Realistic post-surgical activity expectations |

|

aContraindications for MAT are controversial, as the available literature discussing contraindications is very limited. This list is based on the experience of the senior author.

Long-term prospective studies have shown high graft survival and predominantly positive functional results after MAT. Age indications have expanded, with 1 recent study reporting 6% reoperation rate and zero failures in a cohort of 37 adolescent MAT patients.12 High survival rates hold even among an athletic population, where rates of return to play after MAT have been reported to be >75% for those competing at a high school level or higher.13 In an active military population, <2% of patients progressed to revision MAT or total knee arthroplasty at minimum 2-year follow-up, but 22% of patients were unable to return to military duty owing to residual knee limitations.14 In this series, tobacco use correlated with failure, whereas MAT by high-volume, fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons decreased rates of failure.

2. GRAFT SELECTION

In preparation for MAT, accurate measurements must be taken for appropriate size matching. Several measurement techniques have been described, including using plain radiographs, 3D computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).15-18 There is limited data regarding the consequences of an improperly sized donor meniscus; however, an oversized lateral meniscus has been shown to increase the contact forces across the articular cartilage.19 Additionally, an undersized allograft may result in normal forces across the articular cartilage but greater forces across the meniscus.19

When sizing the recipient knee for MAT, accurate width and length measurements are critical. The most common technique used today includes measurements using anteroposterior and lateral radiographic images as described by Pollard and colleagues.15 The width of the meniscus is determined by the distance between 2 vertical lines perpendicular to the joint line, 1 of them tangential to the margin of the tibia metaphysis and the other between the medial and lateral tibial eminence in both knees (Figures 1A,1B). The length of the meniscus is measured on a lateral radiograph. A line is drawn at the level of the articular line between the anterior surface of the tibia above the tuberosity and a parallel line that is tangential to the posterior margin of the tibial plateau. Percent corrections are performed for these dimensions as described in previous publications.

Other techniques have been described to obtain accurate measurements of the recipient knee. For example, obtaining an MRI of the contralateral knee may provide a reproducible method of measuring both the width and length of the medial and lateral menisci.20 CT has been used to measure the lateral meniscus independently, and it has been shown to exhibit less error in the measure of the tibial plateau when compared with X-rays.18 Both CT and MRI are more expensive than simple radiographs, and CT exposes the patient to an increased amount of radiation. Current evidence does not support standard use of these advanced imaging modalities for meniscal sizing.

Continue to: GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT...

3. GRAFT PREPARATION AND PLACEMENT

At the time of surgery, the meniscus allograft is thawed in sterile saline and prepared on the back table. This can be done before or after the diagnostic arthroscopy and bone-slot preparation. Excess soft tissue surrounding the meniscal rim and/or anterior and posterior horns should be removed. Several techniques for MAT have been described, but we generally prefer a bridge-in-slot technique for both medial and lateral MAT.21 To prepare the meniscus allograft for a bridge-in-slot technique, the graft is cut with an oscillating saw to a width of 7 mm, with care taken to ensure that the bony insertions of both meniscal horns are preserved. Next, a transverse cut is made 10 mm below the meniscal horns to set the depth of the bone bridge. To assist with the sizing of the bone bridge, a rectangular sizing block and cutting jig is used (Figures 2A-2C). After marking the middle and posterior thirds of the meniscus, a No. 2 non-absorbable suture is placed at the junction of the posterior and middle thirds of the meniscus. This completes preparation of the allograft prior to implantation.

Attention is then turned to back the arthroscopy. A standard posteromedial (medial meniscus) or posterolateral (lateral meniscus) accessory incision is made, and a Henning retractor is carefully placed in order to receive the sutures that will be placed through the meniscus allograft via a standard inside-out repair technique. First, a zone-specific cannula is used to place a nitinol wire out the accessory incision. The looped end of the wire is pulled out of the anterior arthrotomy incision that will be used to shuttle the meniscus allograft into the joint. In order to pass the meniscal allograft into the joint, the passing suture previously placed through the meniscus is shuttled through the nitinol wire, and the wire is then pulled out the accessory incision, advancing the meniscus through the anteiror arthrotomy. As the meniscus is introduced, the traction suture is then gently tensioned to get the allograft completely into the joint. Next, the bone bridge is seated into the previously created bone slot, as the soft tissue component is manually pushed beneath the ipsilateral femoral condyle. Under direct visualization, the soft tissue component is reduced with a probe using firm, constant traction. To aid in reduction, it may be useful to apply compartment-specific varus or valgus stress and to cycle the knee once the meniscal complex is reduced.

4. GRAFT FIXATION

Once the graft has been passed completely into the joint, with the bone bridge seated into the bone slot, the long end of an Army-Navy retractor is placed firmly through the arthrotomy on the meniscal bone bridge, maintaining a downward force to allow the bridge to remain slotted. To lever down on the posterior aspect of the graft, a freer elevator is used from anterosuperior to posteroinferior. The bone bridge is then secured using a bioabsorbable interference screw, placed central to the bone bridge opposing the block to the ipsilateral compartment. The remainder of the meniscus is secured with an inside-out repair technique, working from posterior to anterior through a standard medial or lateral meniscal repair approach. In total, approximately 6 to 10 vertical mattress sutures are placed, and these can be placed both superiorly and inferiorly on the meniscus. Posteriorly, an all-inside suture repair device may be helpful. Finally, the anterior aspect of the meniscus is repaired to the capsule in an open fashion prior to closing the arthrotomy. Sutures are tied with the leg in extension. The meniscal repair incision is closed in a standard fashion using layers.

5. CONCOMITANT PATHOLOGY AND MAT

The presence of concomitant knee pathology in the context of meniscus deficiency is a challenging problem that requires careful attention to all aspects of the underlying condition of the knee. In cases where MAT is indicated, issues of malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may also need to be addressed either concomitantly or in staged fashion. For example, medial meniscal deficiency in the setting of varus alignment can be addressed with a concomitant HTO, whereas lateral meniscal deficiency in the setting of valgus malalignment can be addressed with a concomitant DFO. In both cases, the osteotomy corrects an abnormal mechanical axis, offloading the diseased compartment. This accomplishes 2 goals, namely to preserve the new MAT graft and to protect underlying articular cartilage.22-24 The osteotomy is an important contributor to additional pain relief by offloading the compartment, and clinical studies have demonstrated that failure to address malalignment in the setting of surgical intervention for cartilage and meniscal insufficiency leads to inferior clinical outcomes and poor survival of transplanted tissue.25-28

Continue to: In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions...

In a meniscus-deficient patient with chondral lesions (Outerbridge grade 3 or 4), concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration should be considered. Depending on the size and location of the chondral lesion, options include marrow stimulation, autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, as well as chondral and/or osteochondral allograft transplantation. In a systematic review of concomitant MAT and cartilage restoration procedures, Harris and colleagues25 found that failure rates of the combined surgery were similar to those of either surgery in isolation.

Young athletes sustaining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears commonly also have meniscal pathology that must be addressed. Most cases are treated with meniscal repair or partial meniscectomy, but occasionally patients present with ACL tear and symptomatic meniscal deficiency. Specifically, MAT survival relies largely on a knee with ligamentous stability, whereas outcomes of ACL reconstruction are improved with intact and functional menisci.29 The surgical technique for MAT is modified slightly in the setting of performing a concomitant ACL reconstruction, with the ACL tibial tunnel drilled to avoid the meniscal bone slot if possible, followed by femoral tunnel creation. Femoral fixation of the ACL graft is accomplished after preparation of the meniscal slot. The meniscal graft is set into place (sutures are not yet tied), and tibial fixation of the ACL graft is performed next. We typically use an Achilles allograft for the ACL reconstruction, with the bone block used for femoral fixation to avoid bony impingement between the MAT bone bridge/block and the ACL graft. With the knee in full extension, the MAT sutures are tied at the conclusion of the surgical procedure. Concomitant MAT and ACL reconstruction has yielded positive long-term clinical outcomes, improved joint stability, and findings similar to historical results of ACL reconstruction or MAT performed in isolation.30,31

CONCLUSION

When used with the proper indications, MAT has demonstrated the ability to restore function and reduce pain. Successful meniscal transplant requires attention to the patient’s past medical and surgical history. Similarly, care must be taken to address any concomitant knee pathology, such as coronal realignment, ligament reconstruction, or cartilage restoration.

1. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;11(11):1-25.

2. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339. doi:10.1177/0363546513495641.

3. Saltzman BM, Bajaj S, Salata M, et al. Prospective long-term evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation procedure: a minimum of 7-year follow-up. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(2):165-175. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1313738.

4. van der Wal RJ, Thomassen BJ, van Arkel ER. Long-term clinical outcome of open meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2134-2139. doi:10.1177/0363546509336725.

5. Vundelinckx B, Vanlauwe J, Bellemans J. Long-term subjective, clinical, and radiographic outcome evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation in the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1592-1599. doi:10.1177/0363546514530092.

6. Hergan D, Thut D, Sherman O, Day MS. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):101-112. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.05.019.

7. Elattar M, Dhollander A, Verdonk R, Almqvist KF, Verdonk P. Twenty-six years of meniscal allograft transplantation: is it still experimental? A meta-analysis of 44 trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):147-157. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1351-6.

8. Verdonk R, Volpi P, Verdonk P, et al. Indications and limits of meniscal allografts. Injury. 2013;44(Suppl 1):S21-S27. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(13)70006-8.

9. Frank RM, Yanke A, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: letter to the editor. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):NP8-NP9. doi:10.1177/0363546515571065.

10. Aagaard H, Jørgensen U, Bojsen-Møller F. Immediate versus delayed meniscal allograft transplantation in sheep. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406(406):218-227. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000030066.92399.7f.

11. Jiang D, Ao YF, Gong X, Wang YJ, Zheng ZZ, Yu JK. Comparative study on immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: 4- to 6-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2329-2337. doi:10.1177/0363546514541653.

12. Riboh JC, Tilton AK, Cvetanovich GL, Campbell KA, Cole BJ. Meniscal allograft transplantation in the adolescent population. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):1133-1140.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.11.041.

13. Chalmers PN, Karas V, Sherman SL, Cole BJ. Return to high-level sport after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):539-544. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.027.

14. Waterman BR, Rensing N, Cameron KL, Owens BD, Pallis M. Survivorship of meniscal allograft transplantation in an athletic patient population. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1237-1242. doi:10.1177/0363546515626184.

15. Pollard ME, Kang Q, Berg EE. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):684-687. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(95)90110-8.

16. Haut TL, Hull ML, Howell SM. Use of roentgenography and magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal geometry determined with a three-dimensional coordinate digitizing system. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(2):228-237. doi:10.1002/jor.1100180210.

17. Van Thiel GS, Verma N, Yanke A, Basu S, Farr J, Cole B. Meniscal allograft size can be predicted by height, weight, and gender. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(7):722-727. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.01.004.

18. McConkey M, Lyon C, Bennett DL, et al. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation using 3-D CT reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(3):221-225. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1292651.

19. Dienst M, Greis PE, Ellis BJ, Bachus KN, Burks RT. Effect of lateral meniscal allograft sizing on contact mechanics of the lateral tibial plateau: an experimental study in human cadaveric knee joints. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(1):34-42. doi:10.1177/0363546506291404.

20. Yoon JR, Jeong HI, Seo MJ, et al. The use of contralateral knee magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal size during meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(10):1287-1293. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.009.

21. Lee AS, Kang RW, Kroin E, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Allograft meniscus transplantation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):106-114. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e318246f005.

22. Agneskirchner JD, Hurschler C, Wrann CD, Lobenhoffer P. The effects of valgus medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy on articular cartilage pressure of the knee: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(8):852-861. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.018.

23. Loening AM, James IE, Levenston ME, et al. Injurious mechanical compression of bovine articular cartilage induces chondrocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381(2):205-212. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.1988.

24. Mina C, Garrett WE Jr, Pietrobon R, Glisson R, Higgins L. High tibial osteotomy for unloading osteochondral defects in the medial compartment of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):949-955. doi:10.1177/0363546508315471.

25. Harris JD, Cavo M, Brophy R, Siston R, Flanigan D. Biological knee reconstruction: a systematic review of combined meniscal allograft transplantation and cartilage repair or restoration. Arthroscopy: 2011;27(3):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.007.

26. Rue JP, Yanke AB, Busam ML, McNickle AG, Cole BJ. Prospective evaluation of concurrent meniscus transplantation and articular cartilage repair: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1770-1778. doi:10.1177/0363546508317122.

27. Kazi HA, Abdel-Rahman W, Brady PA, Cameron JC. Meniscal allograft with or without osteotomy: a 15-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):303-309. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-3291-z.

28. Verdonk PC, Verstraete KL, Almqvist KF, et al. Meniscal allograft transplantation: long-term clinical results with radiological and magnetic resonance imaging correlations. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):694-706. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0033-2.

29. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery. Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):446-452. doi:10.1177/03635465000280040201.

30. Graf KW Jr, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Long-term results after combined medial meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: minimum 8.5-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(2):129-140. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.032.

31. Binnet MS, Akan B, Kaya A. Lyophilised medial meniscus transplantations in ACL-deficient knees: a 19-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(1):109-113. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1556-3.

1. Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2009;11(11):1-25.

2. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005-2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339. doi:10.1177/0363546513495641.

3. Saltzman BM, Bajaj S, Salata M, et al. Prospective long-term evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation procedure: a minimum of 7-year follow-up. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(2):165-175. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1313738.

4. van der Wal RJ, Thomassen BJ, van Arkel ER. Long-term clinical outcome of open meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2134-2139. doi:10.1177/0363546509336725.

5. Vundelinckx B, Vanlauwe J, Bellemans J. Long-term subjective, clinical, and radiographic outcome evaluation of meniscal allograft transplantation in the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1592-1599. doi:10.1177/0363546514530092.

6. Hergan D, Thut D, Sherman O, Day MS. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(1):101-112. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.05.019.

7. Elattar M, Dhollander A, Verdonk R, Almqvist KF, Verdonk P. Twenty-six years of meniscal allograft transplantation: is it still experimental? A meta-analysis of 44 trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(2):147-157. doi:10.1007/s00167-010-1351-6.

8. Verdonk R, Volpi P, Verdonk P, et al. Indications and limits of meniscal allografts. Injury. 2013;44(Suppl 1):S21-S27. doi:10.1016/S0020-1383(13)70006-8.

9. Frank RM, Yanke A, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: letter to the editor. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):NP8-NP9. doi:10.1177/0363546515571065.

10. Aagaard H, Jørgensen U, Bojsen-Møller F. Immediate versus delayed meniscal allograft transplantation in sheep. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406(406):218-227. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000030066.92399.7f.

11. Jiang D, Ao YF, Gong X, Wang YJ, Zheng ZZ, Yu JK. Comparative study on immediate versus delayed meniscus allograft transplantation: 4- to 6-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(10):2329-2337. doi:10.1177/0363546514541653.

12. Riboh JC, Tilton AK, Cvetanovich GL, Campbell KA, Cole BJ. Meniscal allograft transplantation in the adolescent population. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(6):1133-1140.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2015.11.041.

13. Chalmers PN, Karas V, Sherman SL, Cole BJ. Return to high-level sport after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):539-544. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.027.

14. Waterman BR, Rensing N, Cameron KL, Owens BD, Pallis M. Survivorship of meniscal allograft transplantation in an athletic patient population. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1237-1242. doi:10.1177/0363546515626184.

15. Pollard ME, Kang Q, Berg EE. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):684-687. doi:10.1016/0749-8063(95)90110-8.

16. Haut TL, Hull ML, Howell SM. Use of roentgenography and magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal geometry determined with a three-dimensional coordinate digitizing system. J Orthop Res. 2000;18(2):228-237. doi:10.1002/jor.1100180210.

17. Van Thiel GS, Verma N, Yanke A, Basu S, Farr J, Cole B. Meniscal allograft size can be predicted by height, weight, and gender. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(7):722-727. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2009.01.004.

18. McConkey M, Lyon C, Bennett DL, et al. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation using 3-D CT reconstruction. J Knee Surg. 2012;25(3):221-225. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1292651.

19. Dienst M, Greis PE, Ellis BJ, Bachus KN, Burks RT. Effect of lateral meniscal allograft sizing on contact mechanics of the lateral tibial plateau: an experimental study in human cadaveric knee joints. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(1):34-42. doi:10.1177/0363546506291404.

20. Yoon JR, Jeong HI, Seo MJ, et al. The use of contralateral knee magnetic resonance imaging to predict meniscal size during meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(10):1287-1293. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2014.05.009.

21. Lee AS, Kang RW, Kroin E, Verma NN, Cole BJ. Allograft meniscus transplantation. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012;20(2):106-114. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e318246f005.

22. Agneskirchner JD, Hurschler C, Wrann CD, Lobenhoffer P. The effects of valgus medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy on articular cartilage pressure of the knee: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(8):852-861. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.05.018.

23. Loening AM, James IE, Levenston ME, et al. Injurious mechanical compression of bovine articular cartilage induces chondrocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381(2):205-212. doi:10.1006/abbi.2000.1988.

24. Mina C, Garrett WE Jr, Pietrobon R, Glisson R, Higgins L. High tibial osteotomy for unloading osteochondral defects in the medial compartment of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):949-955. doi:10.1177/0363546508315471.

25. Harris JD, Cavo M, Brophy R, Siston R, Flanigan D. Biological knee reconstruction: a systematic review of combined meniscal allograft transplantation and cartilage repair or restoration. Arthroscopy: 2011;27(3):409-418. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.08.007.

26. Rue JP, Yanke AB, Busam ML, McNickle AG, Cole BJ. Prospective evaluation of concurrent meniscus transplantation and articular cartilage repair: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1770-1778. doi:10.1177/0363546508317122.

27. Kazi HA, Abdel-Rahman W, Brady PA, Cameron JC. Meniscal allograft with or without osteotomy: a 15-year follow-up study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(1):303-309. doi:10.1007/s00167-014-3291-z.

28. Verdonk PC, Verstraete KL, Almqvist KF, et al. Meniscal allograft transplantation: long-term clinical results with radiological and magnetic resonance imaging correlations. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(8):694-706. doi:10.1007/s00167-005-0033-2.

29. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery. Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):446-452. doi:10.1177/03635465000280040201.

30. Graf KW Jr, Sekiya JK, Wojtys EM; Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Long-term results after combined medial meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: minimum 8.5-year follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(2):129-140. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.032.

31. Binnet MS, Akan B, Kaya A. Lyophilised medial meniscus transplantations in ACL-deficient knees: a 19-year follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(1):109-113. doi:10.1007/s00167-011-1556-3.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Patient selection is critical for obtaining long-term functional outcome improvements and reduced pain, with the ideal MAT candidate being a chronologically and physiologically young patient (<50 years) with symptomatic meniscal deficiency.

- Existing pathology in the knee needs to be carefully considered and issues such as malalignment, cartilage defects, and/or ligamentous instability may require a staged or concomitant procedure.

- Accurate graft width and length measurements are vital, and the most common technique used today includes measuring the meniscus on anteroposterior and lateral radiographic images.

- When preparing the graft for the bone-bridge technique, the bone is fashioned to create a bone bridge 10 mm in depth by approximately 7 mm in width, incorporating the anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus.

- Graft fixation can be accomplished by placing vertical mattress sutures and tying those down with the knee in full extension.

Reasons for Readmission Following Primary Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

ABSTRACT

An increasing interest focuses on the rates and risk factors for hospital readmission. However, little is known regarding the readmission following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). This study aims to determine the rates, risk factors, and reasons for hospital readmission following primary TSA. Patients undergoing TSA (anatomic or reverse) as part of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program in 2011 to 2013 were identified. The rate of unplanned readmission to the hospital within 30 postoperative days was characterized. Using multivariate regression, demographic and comorbidity factors were tested for independent association with readmission. Finally, the reasons for readmission were characterized. A total of 3627 patients were identified. Among the admitted patients, 93 (2.56%) were readmitted within 30 days of surgery. The independent risk factors for readmission included old age (for age 60-69 years, relative risk [RR] = 1.6; for age 70-79 years, RR = 2.3; for age ≥80 years, RR = 23.1; P = .042), male sex (RR = 1.6, P = .025), anemia (RR = 1.9, P = .005), and dependent functional status (RR = 2.8, P = .012). The reasons for readmission were available for 84 of the 93 readmitted patients. The most common reasons for readmission comprised pneumonia (14 cases, 16.7%), dislocation (7 cases, 8.3%), pulmonary embolism (7 cases, 8.3%), and surgical site infection (6 cases, 7.1%). Unplanned readmission occurs following about 1 in 40 cases of TSA. The most common causes of readmission include pneumonia, dislocation, pulmonary embolism, and surgical site infection. Patients with old age, male sex, anemia, and dependent functional status are at higher risk for readmission and should be counseled and monitored accordingly.

Continue to: Total shoulder arthroplasty...

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is performed with increasing frequency in the United States and is considered to be cost-effective.1-4 Following the procedure, patients generally achieve shoulder function and pain relief.5-8 Despite the success of the procedure, the growing literature on TSA has also reported rates of complications between 3.6% and 25% of the treated patients.9-16

In recent years, an increasing interest has focused on the rates and risk factors for unplanned hospital readmissions; these variables may not only reflect the quality of patient care but also result in considerable costs to the healthcare system. For instance, among Medicare patients, readmissions within 30 days of discharge occur in almost 20% of cases, costing $17.4 billion per year.17 Readmission rates increasingly factor into hospital performance metrics and reimbursement, including the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act that reduces Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services payments to hospitals with high 30-day readmission rates.18

To date, only a few studies have evaluated readmission following TSA, with 30- to 90-day readmission rates ranging from 4.5% to 7.3%.19-23 These studies comprised single institution series20,22 and analyses of administrative databases.19,21,23 Most studies have shown that readmission occurs more often for medical than surgical reasons, with surgical reasons most commonly including infection and dislocation.19-23 However, only limited analyses have been conducted regarding risk factors for readmission.21,23 To date and to our knowledge, no study has investigated reasons for readmission following TSA using nationwide data.

This study aims to determine the rates, risk factors, and reasons for hospital readmission following primary TSA in the United States using the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database.

METHODS

DATA SOURCE

The NSQIP database was utilized to address the study purpose. NSQIP is a nationwide prospective surgical registry established by the American College of Surgeons and reports data from academic and community hospitals across the United States.24 Patients undertaking surgery at these centers are followed by the surgical clinical reviewers at the participating NSQIP sites prospectively for 30 days following the procedure to record complications including readmission. Preoperative and surgical data, such as demographics, medical comorbid diseases, and operative time, are also included. Previous studies have analyzed the complications of various orthopedic surgeries using the NSQIP data.14,16,25-30

DATA COLLECTION

We retrospectively identified from NSQIP the patients who underwent primary TSA (anatomic or reverse) in 2013 to 2014. The timeframe 2013 to 2014 was used because NSQIP only began recording reasons for readmission in 2013. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code for TSA (23472); preoperative diagnosis according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 714.0, 715.11, 715.31, 715.91, 715.21, 715.89, 716.xx 718.xx, 719.xx, 726.x, 727.xx, and 733.41 (where x is a wild card digit); and no missing demographic, comorbidity, or outcome data. Anatomic and reverse TSA were analyzed together because they share the same CPT code, and the NSQIP database prevents searching by the ICD-9 procedure code.

The rate of unplanned readmission to the hospital within 30 postoperative days was characterized. The reasons for readmission in this 30-day period were only available in 2013 and were determined using the ICD-9 diagnosis codes. Patient demographics were recorded for use in identifying potential risk factors for readmission; the demographic data included sex, age, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities, including end-stage renal disease, dyspnea on exertion, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Continue to: Statistical analysis...

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp). First, using bivariate and multivariate regression, demographic and comorbidity factors were tested for independent association with readmission to the hospital within 30 days of surgery. Second, among the readmitted patients, the reasons for readmission were tabulated. Of note, the reasons for readmission were only documented for the procedures performed in 2013. All tests were 2-tailed and conducted at an α level of 0.05.

RESTULTS

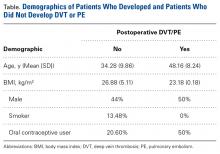

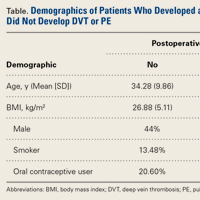

A total of 3627 TSA patients were identified. The mean age (± standard deviation) was 69.4 ± 9.5 years, 55.8% of patients were female, and mean BMI was 30.1 ± 7.0 years. Table 1 provides the additional demographic data. Of the 3627 included patients, 93 (2.56%) were readmitted within 30 days of surgery. The 95% confidence interval for the estimated rate of readmission reached 2.05% to 3.08%.

Table 1. Patient Population

| Number | Percent |

Total | 3627 | 100.0% |

Age |

|

|

18-59 | 539 | 14.9% |

60-69 | 1235 | 34.1% |

70-79 | 1317 | 36.3% |

≥80 | 536 | 14.8% |

Sex |

|

|

Male | 1603 | 44.2% |

Female | 2024 | 55.8% |

Body mass index |

|

|

Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 650 | 17.9% |

Overweight (25-30 kg/m2) | 1147 | 31.6% |

Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 1830 | 50.5% |

Functional status |

|

|

Independent | 3544 | 97.7% |

Dependent | 83 | 2.3% |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

|

No | 3022 | 83.3% |

Yes | 605 | 16.7% |

Dyspnea on exertion |

|

|

No | 3393 | 93.6% |

Yes | 234 | 6.5% |

Hypertension |

|

|

No | 1192 | 32.9% |

Yes | 2435 | 67.1% |

COPD |

|

|

No | 3384 | 93.3% |

Yes | 243 | 6.7% |

Current smoker |

|

|

No | 3249 | 89.6% |

Yes | 378 | 10.4% |

Anemia |

|

|

No | 3051 | 84.1% |

Yes | 576 | 15.9% |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

In the bivariate analyses (Table 2), the following factors were positively associated readmission: older age (60-69 years, relative risk [RR] = 1.6; 70-79 years, RR = 2.2; ≥80 years, RR = 3.3; P = .011), dependent functional status (RR = 2.9, P = .008), and anemia (RR = 2.2, P < .001).

Table 2. Bivariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Readmission

| Rate | RR | 95% CI | P-value |

Age |

|

|

| 0.011 |

18-59 | 1.30% | Ref. | - |

|

60-69 | 2.02% | 1.6 | 0.7-3.6 |

|

70-79 | 2.89% | 2.2 | 1.0-4.9 |

|

≥80 | 4.29% | 3.3 | 1.4-7.6 |

|

Sex |

|

|

| 0.099 |

Female | 2.17% | Ref. | - |

|

Male | 3.06% | 1.4 | 0.9-2.1 |

|

Body mass index |

|

|

| 0.764 |

Normal (<25 kg/m2) | 2.92% | Ref. | - |

|

Overweight (25-30 kg/m2) | 2.35% | 0.8 | 0.5-1.4 |

|

Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 2.57% | 0.9 | 0.5-1.5 |

|

Functional status |

|

|

| 0.008 |

Independent | 2.45% | Ref. | - |

|

Dependent | 7.23% | 2.9 | 1.3-6.5 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

|

|

| 0.483 |

No | 2.48% | Ref. | - |

|

Yes | 2.98% | 1.2 | 0.7-2.0 |

|

Dyspnea on exertion |

|

|

| 0.393 |

No | 2.51% | Ref. | - |

|

Yes | 3.42% | 1.4 | 0.7-2.8 |

|

Hypertension |

|

|

| 0.145 |

No | 2.01% | Ref. | - |

|

Yes | 2.83% | 1.4 | 0.9-2.2 |

|

COPD |

|

|

| 0.457 |

No | 2.51% | Ref. | - |

|

Yes | 3.29% | 1.3 | 0.6-2.7 |

|

Current smoker |

|

|

| 0.116 |

No | 2.71% | Ref. | - |

|

Yes | 1.32% | 0.5 | 0.2-1.2 |

|

Anemia |

|

|

| <0.001 |