User login

Hospitalized Medical Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Review of the Literature and a Roadmap for Improved Care

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a syndrome that occurs after exposure to a significant traumatic event and is characterized by persistent, debilitating symptoms that fall into four “diagnostic clusters” as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Version V (DSM-V). Patients may experience intrusive thoughts, avoidance of distressing stimuli, persistent negative mood, and hypervigilance, all of which last longer than 1 month.1

A national survey of United States households conducted during 2001-2003 estimated the 12-month prevalence of PTSD among adults to be 3.5%.2 Lifetime prevalence has been found to be between 6.8%3 and 7.8%.4 PTSD is more common in veterans. The prevalence of PTSD in veterans differs depending on the conflict in which the veteran participated. Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of approximately 30%,5,6 Gulf War veterans approximately 15%,7 and veterans of more recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq of approximately 21%.8 With the MISSION Act moving more veteran care into the private sector, non-VA inpatient providers will need to become better versed in PTSD.9

Patients with PTSD have more contact with the healthcare system, even for non–mental health problems,8,10-13 and a significantly higher burden of medical comorbities,14 such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease, gastritis and gastric ulcers, HIV, arthritis,15 and coronary heart disease.16 Veterans with PTSD are hospitalized three times more often than are those with no mental health diagnoses,8 and patients with psychiatric comorbidities have higher lengths of stay.17 More than 1.4 million hospitalizations occurring during 2002-2011 had either a primary or secondary associated diagnosis of PTSD, with total inflation-adjusted charges of 34.9 billion dollars.18 In the inpatient sample from this study, greater than half were admitted for a primary diagnosis of mental diseases and disorders (Major Diagnostic Category [MDC] 19). Following mental illness, the most common primary diagnoses for men were MDC 5 (Circulatory System, 12.1%), MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 9.2%), and MDC 4 (Respiratory System, 7.4%), while the most common categories for women were MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 5.8%), MDC 21 (Injuries, Poison, and Toxic Effect of Drugs, 4.9%), and MDC 6 (Digestive System, 4.5%).18

In both the inpatient and outpatient settings, a fundamental challenge to comprehensive PTSD management is correctly diagnosing this condition.19 Confounding the difficulties in diagnosis are numerous comorbidities. In addition to the physical comorbidities described above, more than 70% of patients with PTSD have another psychological comorbidity such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, or substance use disorder/dependency.20

Given that PTSD may be an underrecognized burden on the healthcare system, we sought to better understand how PTSD could affect hospitalized patients admitted for medical problems by conducting this narrative review. Additionally, three of the authors collaborated with the VA Employee Education Service to conduct a needs assessment of VA hospitalists in 2013. Respondents identified managing and educating patients and families about PTSD as a major educational need (unpublished data available upon request from the corresponding author). Therefore, our aims were to present a synthesis of existing literature, familiarize readers with the tenets of trauma-informed care as a framework to guide care for these patients, and generate ideas for changes that inpatient providers could implement now. We began by consulting a research librarian at the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who searched the following databases: PsycInfo, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PILOTS (a PTSD/trauma specific database). Search terms included hospital, hospitalized, and hospitalization, as well as traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress, and PTSD. Pertinent guidelines and the reference lists from included papers were examined. We focused on papers that described patients admitted for medical problems other than PTSD because those patients who are admitted for PTSD-related problems should be primarily managed by psychiatry (not hospitalists) with the primary focus of their hospitalization being their PTSD. We also excluded papers about patients developing PTSD secondary to hospitalization, which already has a well-developed literature.21-23

THE LITERATURE ABOUT PTSD IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

The literature is sparse describing frequency or type of problems encountered by hospitalized medical patients with PTSD. A recent small survey study reported that 40% of patients anticipated triggers for their PTSD symptoms in the hospital; such triggers included loud noises and being shaken awake.24 Two papers describe case vignettes of patients who had exacerbations of their PTSD while in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), although neither contain frequency or severity data.25,26 Approximately 8% of patients in VA ICUs have PTSD,27 and a published abstract suggests that they appear to require more sedation than do patients without PTSD.28 Another published case report describes a patient with recurrent PTSD symptoms (nightmares) after moving into a nursing home.29 These papers suggest other providers have recognized and are concerned about hospitalized patients with PTSD. At present, there are no data to quantify how often hospitalized patients have PTSD exacerbations or how troublesome such exacerbations are to these patients.

Given that there is little empiric literature to guide inpatient management of PTSD as a comorbidity in hospitalized medical patients, we extrapolate some information from the outpatient setting. PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by individual patients in the outpatient setting.30 Failure to have an associated diagnosis of PTSD may lead to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients by inpatient providers in the hospital setting. Additionally, the numerous psychological and physical comorbidities in PTSD can create unique challenges in properly managing any single problem in these patients.20 Armed with this knowledge, providers should be vigilant in the recognition, assessment, and treatment of PTSD.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF PTSD

Trauma-Informed Care: A Conceptual Model

Trauma-informed care is a mindful and sensitive approach to caring for patients who have suffered trauma.31 It requires understanding that many people have suffered trauma in their lives and that the trauma continues to impact many aspects of their lives.32 Trauma-informed care has many advocates and has been implemented across myriad health and social services settings.33 Its principles can be applied in both the inpatient and outpatient hospital settings. While it is an appropriate approach to patients with PTSD, it is not specific to PTSD. People who have suffered sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, child abuse, or other exposures would also be included in the group of people for whom trauma-informed care is a suitable approach. There are four key assumptions to a trauma-informed approach to care (the 4 R’s): (1) realization that trauma affects an individual’s coping strategies, relationships, and health; (2) recognition of the signs of trauma; (3) having an appropriate, planned response to patients identified as having suffered a trauma; and (4) resisting retraumatization in the care setting.31,32

General Approach to Treating Medical Patients With PTSD in the Inpatient Setting

Recognition

Consistent with a trauma-informed care approach, inpatient providers should be able to recognize patients who may have PTSD. First, careful review of the past medical history may show some patients already carry this diagnosis. Second, patients with PTSD often have other comorbidities that could offer a clue that PTSD could be present as well; for example, risk for PTSD is increased when mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are present.20 When PTSD is suspected, screening is a reasonable next step.

The Primary Care-PTSD-5 (PC-PTSD-5) is a validated screening tool used in the outpatient setting.34 It is easily administered and has good predictive validity (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] of 6.33 and LR– of 0.06). It begins with a question of whether the patient has ever experienced a trauma. A positive initial response triggers a series of five yes/no questions. Answering “yes” to three or more questions is a positive screen. A positive screen should result in consultation to psychiatry to conduct more formal evaluation and guide longer-term management.

Collaboration

Individual trauma-focused psychotherapy is the primary treatment of choice for PTSD with strong evidence supporting its practice.35 This treatment is administered by a psychiatrist or psychologist and will be limited in the inpatient medical setting. Current recommendations suggest pharmacotherapy only when individualized trauma-focused psychotherapy is not available, the patient declines it, or as an adjunct when psychotherapy alone is not effective.36 Therefore, inpatient providers may see patients who are prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, paroxetine, fluoxetine) or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine).36 In the past, PTSD-related nightmares were often treated with prazosin.37 However, a recent randomized controlled trial of prazosin in veterans with PTSD failed to show significant improvement in nightmares.38 Hence, current guidelines do not recommend prazosin as a first-line therapy.39 For hospitalized patients with PTSD symptoms refractory to the interventions outlined herein, particularly those patients with possible borderline personality traits (as suggested by severe anger and impulsivity), we strongly recommend partnering with psychiatry. Finally, given the high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in PTSD patients, awareness and treatment of comorbidities such as opioid and alcohol dependence must be concurrently addressed.

Individualizing Care

It is essential for the healthcare team to identify ways to meet each patient’s immediate needs. Many of the ideas proposed below are not specific to PTSD; many require an interprofessional approach to care.40 From a trauma-informed care standpoint, this is akin to having a planned response for patients who have suffered trauma. Assessing the individual’s needs and incorporating therapeutic modalities such as reflective listening, broadening safe opportunities for control, and providing complementary and integrative medicine (IM) therapies may help manage symptoms and establish rapport.41 Through reflective listening, a collaborative approach can be established to identify background, triggers, and a safe approach for managing PTSD and its comorbid conditions. Ensuring frequent communication and allowing the patient to be at the center of decision-making establishes a safe environment and promotes positive rapport between the patient and healthcare team.36 Providing a sense of control by involving the patients in their healthcare decisions and in the structure of care delivery may benefit the patients’ well-being. Furthermore, incorporating IM encourages rest and relaxation in the chaotic hospital environment. Suggested IM interventions include deep breathing, aromatherapy, guided imagery, muscle relaxation, and music therapy.42,43

Key Inpatient Issues Affecting PTSD

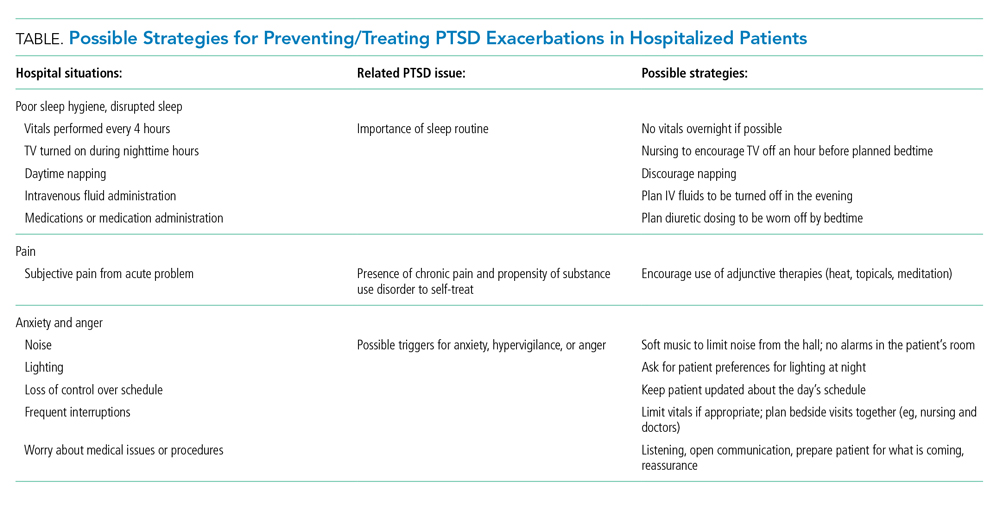

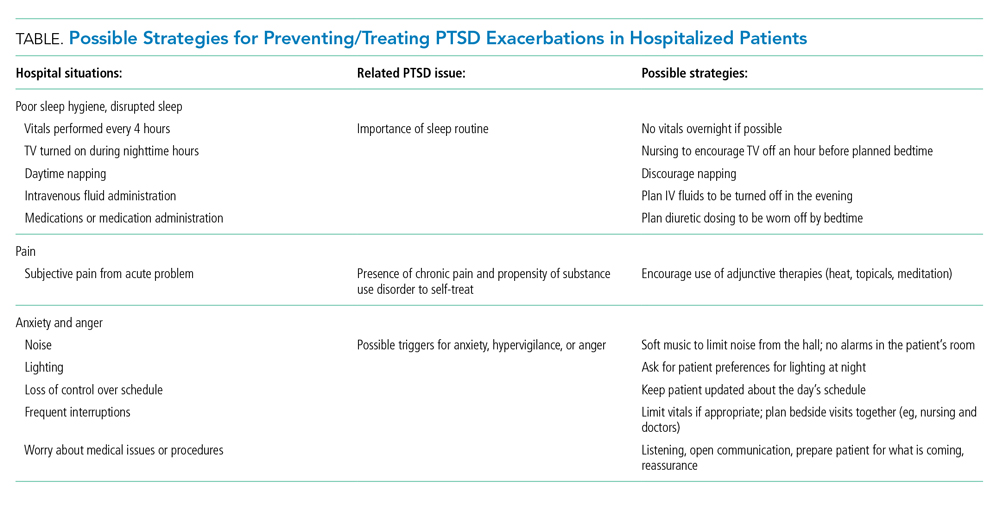

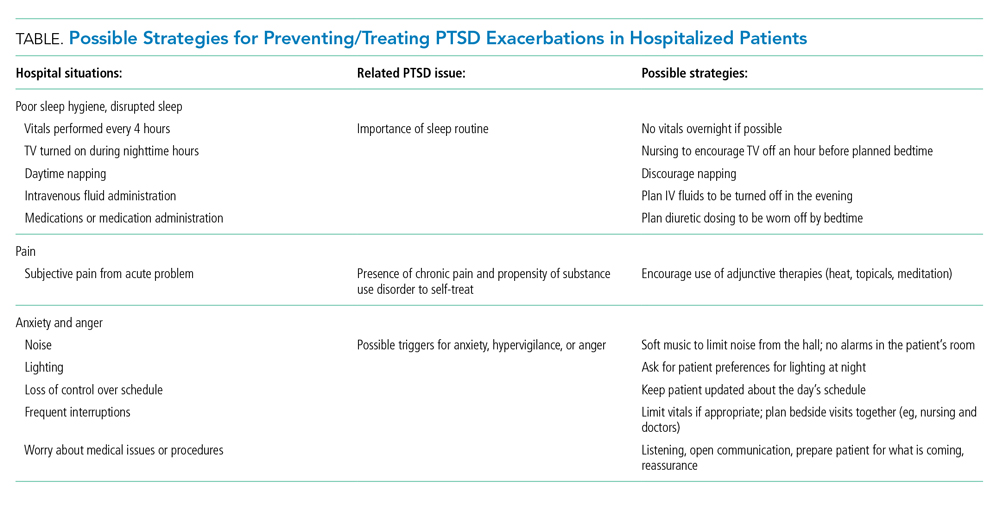

In the following sections, we outline common clinical situations that may exacerbate PTSD symptoms and propose some evidence-based responses (Table). In general, nonpharmacologic approaches are favored over pharmacologic approaches for patients with PTSD.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep problems are very common in patients with PTSD, with nightmares occurring in more than 70% of patients and insomnia in 80%.44 In PTSD, sleep problems are linked to poor physical health and other health outcomes45,46 and may exacerbate other PTSD symptoms.4

Treating the sleep problems that occur with PTSD is an important aspect of PTSD care. Usually administered in the outpatient setting, the treatment of choice is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).48 Sleep-specific CBT focuses, among other things, on strategies that encourage good sleep hygiene,49 which includes promoting regular sleep/wake-up times and specific bedtime routines, avoiding stimulation (eg, light, noise, TV) or excessive liquids before bed, refraining from daytime naps, and using relaxation techniques. Many of these recommendations seem at odds with hospital routines, which may contribute to decompensation of hospitalized patients with PTSD.

While starting sleep-specific CBT in the hospital may not be realistic, we suggest the following goals and strategies as a starting place for promoting healthy sleep for hospitalized patients with PTSD. To begin, factors affecting sleep hygiene should be addressed. Inpatient providers could pay more attention to intravenous (IV) fluid orders, perhaps adjusting them to run only during the daytime hours. Medications can be scheduled at times conducive to maintaining home routines. Avoiding the administration of diuretics close to bedtime may decrease the likelihood of frequent nighttime wakening. Grouping patient care activities, such as bathing or wound care, during daytime hours may allow more opportunities for rest at night. Incorporating uninterrupted sleep protocols, such as quiet hours between 10

Second, providers need to ask about established home bedtime routines and facilitate implementation in the hospital. Through collaboration with patients, providers can incorporate an individualized plan of care for sleep early in hospitalization.50 Partnering with nurses is also essential to creating a sleep-friendly environment that can improve patient experiences.51 Breathing exercises, meditating, listening to music and praying are all examples of “bedtime wind down” strategies recommended in sleep-specific CBT.49 Many of these could be successfully implemented in the hospital and may benefit other hospitalized patients too.52 In patients with PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) reduces nightmares, and if inpatients are on CPAP at home, it should be continued in the hospital.53

Pain

If sleep disturbance is the hallmark of PTSD,47 chronic pain is its coconspirator.15 Uncontrolled pain can make it much more difficult to treat patients with PTSD, which in turn may lead to further decompensation from a mental health standpoint.54 SUDs such as alcohol or opioid dependencies are highly comorbid with PTSD45 and introduce a layer of complexity when managing painin these patients. Providers should be thoughtful when electing to treat acute or chronic pain with opioids and take particular care to establish realistic therapeutic goals if doing so. While patients with PTSD have a greater likelihood of having an SUD, undertreating pain risks exacerbating underlying PTSD symptoms.

Nonpharmacologic therapies, which include communicating, listening, and expressing compassion and understanding, should be utilized by inpatient providers as a first-line treatment in patients with PTSD who suffer from pain. Additionally, relaxation techniques, physical therapy, and physical activity55 can be offered. Pharmacologically, nonopioid medications such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs should always be considered first. Should the use of opioids be deemed necessary, inpatient providers should preferentially use oral over intravenous medications and consider establishing a fixed timeframe for short-term opioids, which should be limited to a few days. Providers should communicate clear expectations with their patients to maximize the desired effect of any specific treatment while minimizing the risk of medication side effects with the goal of agreeing on a short yet effective treatment course.

Anxiety and Anger

One of the most challenging situations for the inpatient provider is encountering a patient who is anxious, angry, or hypervigilant. Mismatch between actual and expected communication between the provider and the patient can lead to frustration and anxiety. A trauma-informed care approach would suggest that frequent and thorough communication with patients may prevent or ameliorate the stresses and anxieties of hospitalization that may manifest as anger because of retraumatization. Hospitalizations usually lead to disruption of normal routine (eg, unpredictable meal times or medication administration), interrupted sleep (eg, woken up for blood draws or provider evaluation), and lack of control of schedule (eg, unsure of exact time when a procedure may be occurring), any of which may trigger symptoms of anxiety and anger in patients with PTSD and lead to hypervigilance.

If situations involving patient anxiety do arise, employ compassion and communication. Extra time spent with the patient, while challenging in the hectic hospital environment, is critical, and nonpharmacological treatments should be the priority. Engaging patients by asking about their PTSD triggers24 may help prevent exacerbations. For example, some patients may specify how they prefer to be woken up to prevent startle reactions. PTSD triggers can be reduced via effective communication with the entire healthcare team. Some immediate yet effective strategies are listening, validation, and negotiation. Benzodiazepine or antipsychotic usage should be avoided.36 Inpatient social work and comanagement with psychiatry involvement may be helpful in more severe exacerbations. A small observational study of patients hospitalized for severe PTSD found an association between walking more during hospitalization and fewer PTSD symptoms,56 suggesting that staying active could be helpful for inpatients with PTSD who are able to safely ambulate.

SUMMARY

PTSD is a common comorbidity among hospitalized patients in the United States. Typical hospital routines may exacerbate symptoms of PTSD such as anxiety and anger. Inpatient providers can play an important role in making hospitalizations go more smoothly for these patients by using principles consistent with trauma-informed care. Specifically, partnering with patients to construct a plan that preserves their sleep routines and accounts for potential triggers for decompensation can improve the hospital experience for patients with PTSD. Some PTSD interventions require additional investment from the healthcare system to deploy, such as staff training in trauma-informed care and reflective listening techniques. Electronic health record–based protocols and order sets for patients with PTSD can leverage available resources. Further research should evaluate hospital outcomes that result from a more tailored approach to the care of patients with PTSD. More effective, patient-centered PTSD care could lower rates of leaving against medical advice and improve the inpatient experience for patients and providers alike.

1. DSM-5 Fact Sheet: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Psychological Association. 2013. Accessed 30 July 2019. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-PTSD.pdf

2. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

4. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

5. Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Schlenger WE, et al. The prevalence of lifetime and partial post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam theater veterans. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5(3):365-376. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050304

6. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al. Trauma And the Vietnam War Generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazel; 1990.

7. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a2feeb

8. Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3

9. VA MISSION Act. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2019. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://missionact.va.gov/

10. Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, Culpepper L. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):398-407. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070082

11. Kartha A, Brower V, Saitz R, Samet JH, Keane TM, Liebschutz J. The impact of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder on healthcare utilization among primary care patients. Med Care. 2008;46(4):388-393. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc5d2

12. Dobie DJ, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder screening status is associated with increased VA medical and surgical utilization in women. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S58-S64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00376.x

13. Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, Beckham JC. Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2081-2086. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081

14. Frayne SM, Chiu VY, Iqbal S, et al. Medical care needs of returning veterans with PTSD: their other burden. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):33-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1497-4

15. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Medical comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in US adults: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(8):697-707. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182303775

16. Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):970-978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.085

17. Bressi SK, Marcus SC, Solomon PL. The impact of psychiatric comorbidity on general hospital length of stay. Psychiatr Q. 2006;77(3):203-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-006-9007-x

18. Haviland MG, Banta JE, Sonne JL, Przekop P. Posttraumatic stress disorder-related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Men Dis. 2016;204(2):78-86. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000432

19. Frommberger U, Angenendt J, Berger M. Post-traumatic stress disorder--a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(5):59-65. https://doi.com/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0059

20. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(9):460-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900902

21. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):421-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006

22. Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1506-1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z

23. Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121-1129. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882

24. Fletcher KE, Collins J, Holzhauer B, Lewis F, Hendricks M. Medical patients with PTSD identify issues with hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1906-1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05480-y

25. Struble LM, Sullivan BJ, Hartman LS. Psychiatric disorders impacting critical illness. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2014;26(1):115-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2013.10.002

26. Baxter A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the intensive care unit patient: implications for staff and advanced practice critical care nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2004;23(4):145-150. http://doi.org/10.1097/00003465-200407000-00001

27. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Preexisting comorbid psychiatric conditions and mortality in nonsurgical intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(3):241-249. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2010967

28. Kebbe J, Lal A, El-Solh A, Jaoude P. Effects of PTSD on patient outcomes in the intensive care unit. Chest. 2015;148(4 Suppl):220A. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.2274366

29. Johnson KG, Rosen J. Re-emergence of posttraumatic stress disorder nightmares with nursing home admission: treatment with prazosin. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(2):130-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.007

30. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199907000-00005

31. Trauma-informed care. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Accessed July 30, 2019. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/healthier-pregnancy/preventive/trauma.html

32. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Department of Health & Human Services; 2014. HHS Publication No. SMA 14-4884. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

33. DeCandia CJ, Guarino K. Trauma-informed care: an ecological response. J Child Youth Care Work. 2015;24:7-32.

34. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The PRIMARY CARE PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

35. Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, Vythilingam M, Rasmusson AM, Hoge CW. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):792-806. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22511

36. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. 2017. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGClinicianSummaryFinal.pdf

37. Singh B, Hughes AJ, Mehta G, Erwin PJ, Parsaik AK. Efficacy of prazosin in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(4). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.16r01943

38. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507598

39. El-Solh AA. Management of nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: current perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:409-420. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S166089

40. What is ROVER? Treatment Services. VA. 2018. Accessed February 14, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/docs/ROVERBrochure.pdf

41. Moser DK, Chung ML, McKinley S, et al. Critical care nursing practice regarding patient anxiety assessment and management. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19(5):276-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0964-3397(03)00061-2

42. Bulechek G, Butcher H, Dochterman JM, Wagner C. Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), 6th Ed. Elsevier; 2013.

43. Blanaru M, Bloch B, Vadas L, et al. The effects of music relaxation and muscle relaxation techniques on sleep quality and emotional measures among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Ment Illn. 2012;4(2):e13. https://doi.org/10.4081/mi.2012.e13

44. Leskin GA, Woodward SH, Young HE, Sheikh JI. Effects of comorbid diagnoses on sleep disturbance in PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36(6):449-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00025-0

45. Vandrey R, Babson KA, Herrmann ES, Bonn-Miller MO. Interactions between disordered sleep, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):237-247. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.901300

46. Clum GA, Nishith P, Resick PA. Trauma-related sleep disturbance and self-reported physical health symptoms in treatment-seeking female rape victims. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(9):618-622. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200109000-00008

47. Germain A. Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: where are we now? Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):372-382. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040432

48. Ho FYY, Chan CS, Tang KNS. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep disturbances in treating posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:90-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.005

49. Thompson KE, Franklin CL, Hubbard K. PTSD sleep therapy group: training your mind and body for better sleep: Therapist Manual. A product of the Department of Veterans Affairs South Central (VISN 16) Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC). Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/Sleep_Therapy_Group_Therapist_Manual.pdf

50. Ye L, Keane K, Hutton Johnson S, Dykes PC. How do clinicians assess, communicate about, and manage patient sleep in the hospital? J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(6):342-347. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182942c8a

51. Arora VM, Machado N, Anderson SL, et al. Effectiveness of SIESTA on objective and subjective metrics of nighttime hospital sleep disruptors. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(1):38-41. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3091

52. Gagner-Tjellesen D, Yurkovich EE, Gragert M. Use of music therapy and other ITNIs in acute care. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2001;39(10):26-37.

53. Tamanna S, Parker JD, Lyons J, Ullah MI. The effect of continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) on nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):631-636. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.3786

54. Brennstuhl MJ, Tarquinio C, Montel S. Chronic pain and PTSD: evolving views on their comorbidity. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(4):295-304. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12093

55. Bosch J, Weaver TL, Neylan TC, Herbst E, McCaslin SE. Impact of engagement in exercise on sleep quality among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1745-e1750. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00385

56. Rosenbaum S, Vancampfort D, Tiedemann A, et al. Among inpatients, posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity is negatively associated with time spent walking. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(1):15-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000415

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a syndrome that occurs after exposure to a significant traumatic event and is characterized by persistent, debilitating symptoms that fall into four “diagnostic clusters” as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Version V (DSM-V). Patients may experience intrusive thoughts, avoidance of distressing stimuli, persistent negative mood, and hypervigilance, all of which last longer than 1 month.1

A national survey of United States households conducted during 2001-2003 estimated the 12-month prevalence of PTSD among adults to be 3.5%.2 Lifetime prevalence has been found to be between 6.8%3 and 7.8%.4 PTSD is more common in veterans. The prevalence of PTSD in veterans differs depending on the conflict in which the veteran participated. Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of approximately 30%,5,6 Gulf War veterans approximately 15%,7 and veterans of more recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq of approximately 21%.8 With the MISSION Act moving more veteran care into the private sector, non-VA inpatient providers will need to become better versed in PTSD.9

Patients with PTSD have more contact with the healthcare system, even for non–mental health problems,8,10-13 and a significantly higher burden of medical comorbities,14 such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease, gastritis and gastric ulcers, HIV, arthritis,15 and coronary heart disease.16 Veterans with PTSD are hospitalized three times more often than are those with no mental health diagnoses,8 and patients with psychiatric comorbidities have higher lengths of stay.17 More than 1.4 million hospitalizations occurring during 2002-2011 had either a primary or secondary associated diagnosis of PTSD, with total inflation-adjusted charges of 34.9 billion dollars.18 In the inpatient sample from this study, greater than half were admitted for a primary diagnosis of mental diseases and disorders (Major Diagnostic Category [MDC] 19). Following mental illness, the most common primary diagnoses for men were MDC 5 (Circulatory System, 12.1%), MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 9.2%), and MDC 4 (Respiratory System, 7.4%), while the most common categories for women were MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 5.8%), MDC 21 (Injuries, Poison, and Toxic Effect of Drugs, 4.9%), and MDC 6 (Digestive System, 4.5%).18

In both the inpatient and outpatient settings, a fundamental challenge to comprehensive PTSD management is correctly diagnosing this condition.19 Confounding the difficulties in diagnosis are numerous comorbidities. In addition to the physical comorbidities described above, more than 70% of patients with PTSD have another psychological comorbidity such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, or substance use disorder/dependency.20

Given that PTSD may be an underrecognized burden on the healthcare system, we sought to better understand how PTSD could affect hospitalized patients admitted for medical problems by conducting this narrative review. Additionally, three of the authors collaborated with the VA Employee Education Service to conduct a needs assessment of VA hospitalists in 2013. Respondents identified managing and educating patients and families about PTSD as a major educational need (unpublished data available upon request from the corresponding author). Therefore, our aims were to present a synthesis of existing literature, familiarize readers with the tenets of trauma-informed care as a framework to guide care for these patients, and generate ideas for changes that inpatient providers could implement now. We began by consulting a research librarian at the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who searched the following databases: PsycInfo, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PILOTS (a PTSD/trauma specific database). Search terms included hospital, hospitalized, and hospitalization, as well as traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress, and PTSD. Pertinent guidelines and the reference lists from included papers were examined. We focused on papers that described patients admitted for medical problems other than PTSD because those patients who are admitted for PTSD-related problems should be primarily managed by psychiatry (not hospitalists) with the primary focus of their hospitalization being their PTSD. We also excluded papers about patients developing PTSD secondary to hospitalization, which already has a well-developed literature.21-23

THE LITERATURE ABOUT PTSD IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

The literature is sparse describing frequency or type of problems encountered by hospitalized medical patients with PTSD. A recent small survey study reported that 40% of patients anticipated triggers for their PTSD symptoms in the hospital; such triggers included loud noises and being shaken awake.24 Two papers describe case vignettes of patients who had exacerbations of their PTSD while in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), although neither contain frequency or severity data.25,26 Approximately 8% of patients in VA ICUs have PTSD,27 and a published abstract suggests that they appear to require more sedation than do patients without PTSD.28 Another published case report describes a patient with recurrent PTSD symptoms (nightmares) after moving into a nursing home.29 These papers suggest other providers have recognized and are concerned about hospitalized patients with PTSD. At present, there are no data to quantify how often hospitalized patients have PTSD exacerbations or how troublesome such exacerbations are to these patients.

Given that there is little empiric literature to guide inpatient management of PTSD as a comorbidity in hospitalized medical patients, we extrapolate some information from the outpatient setting. PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by individual patients in the outpatient setting.30 Failure to have an associated diagnosis of PTSD may lead to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients by inpatient providers in the hospital setting. Additionally, the numerous psychological and physical comorbidities in PTSD can create unique challenges in properly managing any single problem in these patients.20 Armed with this knowledge, providers should be vigilant in the recognition, assessment, and treatment of PTSD.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF PTSD

Trauma-Informed Care: A Conceptual Model

Trauma-informed care is a mindful and sensitive approach to caring for patients who have suffered trauma.31 It requires understanding that many people have suffered trauma in their lives and that the trauma continues to impact many aspects of their lives.32 Trauma-informed care has many advocates and has been implemented across myriad health and social services settings.33 Its principles can be applied in both the inpatient and outpatient hospital settings. While it is an appropriate approach to patients with PTSD, it is not specific to PTSD. People who have suffered sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, child abuse, or other exposures would also be included in the group of people for whom trauma-informed care is a suitable approach. There are four key assumptions to a trauma-informed approach to care (the 4 R’s): (1) realization that trauma affects an individual’s coping strategies, relationships, and health; (2) recognition of the signs of trauma; (3) having an appropriate, planned response to patients identified as having suffered a trauma; and (4) resisting retraumatization in the care setting.31,32

General Approach to Treating Medical Patients With PTSD in the Inpatient Setting

Recognition

Consistent with a trauma-informed care approach, inpatient providers should be able to recognize patients who may have PTSD. First, careful review of the past medical history may show some patients already carry this diagnosis. Second, patients with PTSD often have other comorbidities that could offer a clue that PTSD could be present as well; for example, risk for PTSD is increased when mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are present.20 When PTSD is suspected, screening is a reasonable next step.

The Primary Care-PTSD-5 (PC-PTSD-5) is a validated screening tool used in the outpatient setting.34 It is easily administered and has good predictive validity (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] of 6.33 and LR– of 0.06). It begins with a question of whether the patient has ever experienced a trauma. A positive initial response triggers a series of five yes/no questions. Answering “yes” to three or more questions is a positive screen. A positive screen should result in consultation to psychiatry to conduct more formal evaluation and guide longer-term management.

Collaboration

Individual trauma-focused psychotherapy is the primary treatment of choice for PTSD with strong evidence supporting its practice.35 This treatment is administered by a psychiatrist or psychologist and will be limited in the inpatient medical setting. Current recommendations suggest pharmacotherapy only when individualized trauma-focused psychotherapy is not available, the patient declines it, or as an adjunct when psychotherapy alone is not effective.36 Therefore, inpatient providers may see patients who are prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, paroxetine, fluoxetine) or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine).36 In the past, PTSD-related nightmares were often treated with prazosin.37 However, a recent randomized controlled trial of prazosin in veterans with PTSD failed to show significant improvement in nightmares.38 Hence, current guidelines do not recommend prazosin as a first-line therapy.39 For hospitalized patients with PTSD symptoms refractory to the interventions outlined herein, particularly those patients with possible borderline personality traits (as suggested by severe anger and impulsivity), we strongly recommend partnering with psychiatry. Finally, given the high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in PTSD patients, awareness and treatment of comorbidities such as opioid and alcohol dependence must be concurrently addressed.

Individualizing Care

It is essential for the healthcare team to identify ways to meet each patient’s immediate needs. Many of the ideas proposed below are not specific to PTSD; many require an interprofessional approach to care.40 From a trauma-informed care standpoint, this is akin to having a planned response for patients who have suffered trauma. Assessing the individual’s needs and incorporating therapeutic modalities such as reflective listening, broadening safe opportunities for control, and providing complementary and integrative medicine (IM) therapies may help manage symptoms and establish rapport.41 Through reflective listening, a collaborative approach can be established to identify background, triggers, and a safe approach for managing PTSD and its comorbid conditions. Ensuring frequent communication and allowing the patient to be at the center of decision-making establishes a safe environment and promotes positive rapport between the patient and healthcare team.36 Providing a sense of control by involving the patients in their healthcare decisions and in the structure of care delivery may benefit the patients’ well-being. Furthermore, incorporating IM encourages rest and relaxation in the chaotic hospital environment. Suggested IM interventions include deep breathing, aromatherapy, guided imagery, muscle relaxation, and music therapy.42,43

Key Inpatient Issues Affecting PTSD

In the following sections, we outline common clinical situations that may exacerbate PTSD symptoms and propose some evidence-based responses (Table). In general, nonpharmacologic approaches are favored over pharmacologic approaches for patients with PTSD.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep problems are very common in patients with PTSD, with nightmares occurring in more than 70% of patients and insomnia in 80%.44 In PTSD, sleep problems are linked to poor physical health and other health outcomes45,46 and may exacerbate other PTSD symptoms.4

Treating the sleep problems that occur with PTSD is an important aspect of PTSD care. Usually administered in the outpatient setting, the treatment of choice is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).48 Sleep-specific CBT focuses, among other things, on strategies that encourage good sleep hygiene,49 which includes promoting regular sleep/wake-up times and specific bedtime routines, avoiding stimulation (eg, light, noise, TV) or excessive liquids before bed, refraining from daytime naps, and using relaxation techniques. Many of these recommendations seem at odds with hospital routines, which may contribute to decompensation of hospitalized patients with PTSD.

While starting sleep-specific CBT in the hospital may not be realistic, we suggest the following goals and strategies as a starting place for promoting healthy sleep for hospitalized patients with PTSD. To begin, factors affecting sleep hygiene should be addressed. Inpatient providers could pay more attention to intravenous (IV) fluid orders, perhaps adjusting them to run only during the daytime hours. Medications can be scheduled at times conducive to maintaining home routines. Avoiding the administration of diuretics close to bedtime may decrease the likelihood of frequent nighttime wakening. Grouping patient care activities, such as bathing or wound care, during daytime hours may allow more opportunities for rest at night. Incorporating uninterrupted sleep protocols, such as quiet hours between 10

Second, providers need to ask about established home bedtime routines and facilitate implementation in the hospital. Through collaboration with patients, providers can incorporate an individualized plan of care for sleep early in hospitalization.50 Partnering with nurses is also essential to creating a sleep-friendly environment that can improve patient experiences.51 Breathing exercises, meditating, listening to music and praying are all examples of “bedtime wind down” strategies recommended in sleep-specific CBT.49 Many of these could be successfully implemented in the hospital and may benefit other hospitalized patients too.52 In patients with PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) reduces nightmares, and if inpatients are on CPAP at home, it should be continued in the hospital.53

Pain

If sleep disturbance is the hallmark of PTSD,47 chronic pain is its coconspirator.15 Uncontrolled pain can make it much more difficult to treat patients with PTSD, which in turn may lead to further decompensation from a mental health standpoint.54 SUDs such as alcohol or opioid dependencies are highly comorbid with PTSD45 and introduce a layer of complexity when managing painin these patients. Providers should be thoughtful when electing to treat acute or chronic pain with opioids and take particular care to establish realistic therapeutic goals if doing so. While patients with PTSD have a greater likelihood of having an SUD, undertreating pain risks exacerbating underlying PTSD symptoms.

Nonpharmacologic therapies, which include communicating, listening, and expressing compassion and understanding, should be utilized by inpatient providers as a first-line treatment in patients with PTSD who suffer from pain. Additionally, relaxation techniques, physical therapy, and physical activity55 can be offered. Pharmacologically, nonopioid medications such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs should always be considered first. Should the use of opioids be deemed necessary, inpatient providers should preferentially use oral over intravenous medications and consider establishing a fixed timeframe for short-term opioids, which should be limited to a few days. Providers should communicate clear expectations with their patients to maximize the desired effect of any specific treatment while minimizing the risk of medication side effects with the goal of agreeing on a short yet effective treatment course.

Anxiety and Anger

One of the most challenging situations for the inpatient provider is encountering a patient who is anxious, angry, or hypervigilant. Mismatch between actual and expected communication between the provider and the patient can lead to frustration and anxiety. A trauma-informed care approach would suggest that frequent and thorough communication with patients may prevent or ameliorate the stresses and anxieties of hospitalization that may manifest as anger because of retraumatization. Hospitalizations usually lead to disruption of normal routine (eg, unpredictable meal times or medication administration), interrupted sleep (eg, woken up for blood draws or provider evaluation), and lack of control of schedule (eg, unsure of exact time when a procedure may be occurring), any of which may trigger symptoms of anxiety and anger in patients with PTSD and lead to hypervigilance.

If situations involving patient anxiety do arise, employ compassion and communication. Extra time spent with the patient, while challenging in the hectic hospital environment, is critical, and nonpharmacological treatments should be the priority. Engaging patients by asking about their PTSD triggers24 may help prevent exacerbations. For example, some patients may specify how they prefer to be woken up to prevent startle reactions. PTSD triggers can be reduced via effective communication with the entire healthcare team. Some immediate yet effective strategies are listening, validation, and negotiation. Benzodiazepine or antipsychotic usage should be avoided.36 Inpatient social work and comanagement with psychiatry involvement may be helpful in more severe exacerbations. A small observational study of patients hospitalized for severe PTSD found an association between walking more during hospitalization and fewer PTSD symptoms,56 suggesting that staying active could be helpful for inpatients with PTSD who are able to safely ambulate.

SUMMARY

PTSD is a common comorbidity among hospitalized patients in the United States. Typical hospital routines may exacerbate symptoms of PTSD such as anxiety and anger. Inpatient providers can play an important role in making hospitalizations go more smoothly for these patients by using principles consistent with trauma-informed care. Specifically, partnering with patients to construct a plan that preserves their sleep routines and accounts for potential triggers for decompensation can improve the hospital experience for patients with PTSD. Some PTSD interventions require additional investment from the healthcare system to deploy, such as staff training in trauma-informed care and reflective listening techniques. Electronic health record–based protocols and order sets for patients with PTSD can leverage available resources. Further research should evaluate hospital outcomes that result from a more tailored approach to the care of patients with PTSD. More effective, patient-centered PTSD care could lower rates of leaving against medical advice and improve the inpatient experience for patients and providers alike.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a syndrome that occurs after exposure to a significant traumatic event and is characterized by persistent, debilitating symptoms that fall into four “diagnostic clusters” as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Version V (DSM-V). Patients may experience intrusive thoughts, avoidance of distressing stimuli, persistent negative mood, and hypervigilance, all of which last longer than 1 month.1

A national survey of United States households conducted during 2001-2003 estimated the 12-month prevalence of PTSD among adults to be 3.5%.2 Lifetime prevalence has been found to be between 6.8%3 and 7.8%.4 PTSD is more common in veterans. The prevalence of PTSD in veterans differs depending on the conflict in which the veteran participated. Vietnam veterans have an estimated lifetime prevalence of approximately 30%,5,6 Gulf War veterans approximately 15%,7 and veterans of more recent conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq of approximately 21%.8 With the MISSION Act moving more veteran care into the private sector, non-VA inpatient providers will need to become better versed in PTSD.9

Patients with PTSD have more contact with the healthcare system, even for non–mental health problems,8,10-13 and a significantly higher burden of medical comorbities,14 such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease, gastritis and gastric ulcers, HIV, arthritis,15 and coronary heart disease.16 Veterans with PTSD are hospitalized three times more often than are those with no mental health diagnoses,8 and patients with psychiatric comorbidities have higher lengths of stay.17 More than 1.4 million hospitalizations occurring during 2002-2011 had either a primary or secondary associated diagnosis of PTSD, with total inflation-adjusted charges of 34.9 billion dollars.18 In the inpatient sample from this study, greater than half were admitted for a primary diagnosis of mental diseases and disorders (Major Diagnostic Category [MDC] 19). Following mental illness, the most common primary diagnoses for men were MDC 5 (Circulatory System, 12.1%), MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 9.2%), and MDC 4 (Respiratory System, 7.4%), while the most common categories for women were MDC 20 (Alcohol/Drug Use or Induced Mental Disorder, 5.8%), MDC 21 (Injuries, Poison, and Toxic Effect of Drugs, 4.9%), and MDC 6 (Digestive System, 4.5%).18

In both the inpatient and outpatient settings, a fundamental challenge to comprehensive PTSD management is correctly diagnosing this condition.19 Confounding the difficulties in diagnosis are numerous comorbidities. In addition to the physical comorbidities described above, more than 70% of patients with PTSD have another psychological comorbidity such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, or substance use disorder/dependency.20

Given that PTSD may be an underrecognized burden on the healthcare system, we sought to better understand how PTSD could affect hospitalized patients admitted for medical problems by conducting this narrative review. Additionally, three of the authors collaborated with the VA Employee Education Service to conduct a needs assessment of VA hospitalists in 2013. Respondents identified managing and educating patients and families about PTSD as a major educational need (unpublished data available upon request from the corresponding author). Therefore, our aims were to present a synthesis of existing literature, familiarize readers with the tenets of trauma-informed care as a framework to guide care for these patients, and generate ideas for changes that inpatient providers could implement now. We began by consulting a research librarian at the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who searched the following databases: PsycInfo, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PILOTS (a PTSD/trauma specific database). Search terms included hospital, hospitalized, and hospitalization, as well as traumatic stress, posttraumatic stress, and PTSD. Pertinent guidelines and the reference lists from included papers were examined. We focused on papers that described patients admitted for medical problems other than PTSD because those patients who are admitted for PTSD-related problems should be primarily managed by psychiatry (not hospitalists) with the primary focus of their hospitalization being their PTSD. We also excluded papers about patients developing PTSD secondary to hospitalization, which already has a well-developed literature.21-23

THE LITERATURE ABOUT PTSD IN HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS

The literature is sparse describing frequency or type of problems encountered by hospitalized medical patients with PTSD. A recent small survey study reported that 40% of patients anticipated triggers for their PTSD symptoms in the hospital; such triggers included loud noises and being shaken awake.24 Two papers describe case vignettes of patients who had exacerbations of their PTSD while in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), although neither contain frequency or severity data.25,26 Approximately 8% of patients in VA ICUs have PTSD,27 and a published abstract suggests that they appear to require more sedation than do patients without PTSD.28 Another published case report describes a patient with recurrent PTSD symptoms (nightmares) after moving into a nursing home.29 These papers suggest other providers have recognized and are concerned about hospitalized patients with PTSD. At present, there are no data to quantify how often hospitalized patients have PTSD exacerbations or how troublesome such exacerbations are to these patients.

Given that there is little empiric literature to guide inpatient management of PTSD as a comorbidity in hospitalized medical patients, we extrapolate some information from the outpatient setting. PTSD is often underdiagnosed and underreported by individual patients in the outpatient setting.30 Failure to have an associated diagnosis of PTSD may lead to underrecognition and undertreatment of these patients by inpatient providers in the hospital setting. Additionally, the numerous psychological and physical comorbidities in PTSD can create unique challenges in properly managing any single problem in these patients.20 Armed with this knowledge, providers should be vigilant in the recognition, assessment, and treatment of PTSD.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF PTSD

Trauma-Informed Care: A Conceptual Model

Trauma-informed care is a mindful and sensitive approach to caring for patients who have suffered trauma.31 It requires understanding that many people have suffered trauma in their lives and that the trauma continues to impact many aspects of their lives.32 Trauma-informed care has many advocates and has been implemented across myriad health and social services settings.33 Its principles can be applied in both the inpatient and outpatient hospital settings. While it is an appropriate approach to patients with PTSD, it is not specific to PTSD. People who have suffered sexual trauma, intimate partner violence, child abuse, or other exposures would also be included in the group of people for whom trauma-informed care is a suitable approach. There are four key assumptions to a trauma-informed approach to care (the 4 R’s): (1) realization that trauma affects an individual’s coping strategies, relationships, and health; (2) recognition of the signs of trauma; (3) having an appropriate, planned response to patients identified as having suffered a trauma; and (4) resisting retraumatization in the care setting.31,32

General Approach to Treating Medical Patients With PTSD in the Inpatient Setting

Recognition

Consistent with a trauma-informed care approach, inpatient providers should be able to recognize patients who may have PTSD. First, careful review of the past medical history may show some patients already carry this diagnosis. Second, patients with PTSD often have other comorbidities that could offer a clue that PTSD could be present as well; for example, risk for PTSD is increased when mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders are present.20 When PTSD is suspected, screening is a reasonable next step.

The Primary Care-PTSD-5 (PC-PTSD-5) is a validated screening tool used in the outpatient setting.34 It is easily administered and has good predictive validity (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] of 6.33 and LR– of 0.06). It begins with a question of whether the patient has ever experienced a trauma. A positive initial response triggers a series of five yes/no questions. Answering “yes” to three or more questions is a positive screen. A positive screen should result in consultation to psychiatry to conduct more formal evaluation and guide longer-term management.

Collaboration

Individual trauma-focused psychotherapy is the primary treatment of choice for PTSD with strong evidence supporting its practice.35 This treatment is administered by a psychiatrist or psychologist and will be limited in the inpatient medical setting. Current recommendations suggest pharmacotherapy only when individualized trauma-focused psychotherapy is not available, the patient declines it, or as an adjunct when psychotherapy alone is not effective.36 Therefore, inpatient providers may see patients who are prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, paroxetine, fluoxetine) or serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (eg, venlafaxine).36 In the past, PTSD-related nightmares were often treated with prazosin.37 However, a recent randomized controlled trial of prazosin in veterans with PTSD failed to show significant improvement in nightmares.38 Hence, current guidelines do not recommend prazosin as a first-line therapy.39 For hospitalized patients with PTSD symptoms refractory to the interventions outlined herein, particularly those patients with possible borderline personality traits (as suggested by severe anger and impulsivity), we strongly recommend partnering with psychiatry. Finally, given the high prevalence of substance use disorders (SUDs) in PTSD patients, awareness and treatment of comorbidities such as opioid and alcohol dependence must be concurrently addressed.

Individualizing Care

It is essential for the healthcare team to identify ways to meet each patient’s immediate needs. Many of the ideas proposed below are not specific to PTSD; many require an interprofessional approach to care.40 From a trauma-informed care standpoint, this is akin to having a planned response for patients who have suffered trauma. Assessing the individual’s needs and incorporating therapeutic modalities such as reflective listening, broadening safe opportunities for control, and providing complementary and integrative medicine (IM) therapies may help manage symptoms and establish rapport.41 Through reflective listening, a collaborative approach can be established to identify background, triggers, and a safe approach for managing PTSD and its comorbid conditions. Ensuring frequent communication and allowing the patient to be at the center of decision-making establishes a safe environment and promotes positive rapport between the patient and healthcare team.36 Providing a sense of control by involving the patients in their healthcare decisions and in the structure of care delivery may benefit the patients’ well-being. Furthermore, incorporating IM encourages rest and relaxation in the chaotic hospital environment. Suggested IM interventions include deep breathing, aromatherapy, guided imagery, muscle relaxation, and music therapy.42,43

Key Inpatient Issues Affecting PTSD

In the following sections, we outline common clinical situations that may exacerbate PTSD symptoms and propose some evidence-based responses (Table). In general, nonpharmacologic approaches are favored over pharmacologic approaches for patients with PTSD.

Sleep Hygiene

Sleep problems are very common in patients with PTSD, with nightmares occurring in more than 70% of patients and insomnia in 80%.44 In PTSD, sleep problems are linked to poor physical health and other health outcomes45,46 and may exacerbate other PTSD symptoms.4

Treating the sleep problems that occur with PTSD is an important aspect of PTSD care. Usually administered in the outpatient setting, the treatment of choice is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).48 Sleep-specific CBT focuses, among other things, on strategies that encourage good sleep hygiene,49 which includes promoting regular sleep/wake-up times and specific bedtime routines, avoiding stimulation (eg, light, noise, TV) or excessive liquids before bed, refraining from daytime naps, and using relaxation techniques. Many of these recommendations seem at odds with hospital routines, which may contribute to decompensation of hospitalized patients with PTSD.

While starting sleep-specific CBT in the hospital may not be realistic, we suggest the following goals and strategies as a starting place for promoting healthy sleep for hospitalized patients with PTSD. To begin, factors affecting sleep hygiene should be addressed. Inpatient providers could pay more attention to intravenous (IV) fluid orders, perhaps adjusting them to run only during the daytime hours. Medications can be scheduled at times conducive to maintaining home routines. Avoiding the administration of diuretics close to bedtime may decrease the likelihood of frequent nighttime wakening. Grouping patient care activities, such as bathing or wound care, during daytime hours may allow more opportunities for rest at night. Incorporating uninterrupted sleep protocols, such as quiet hours between 10

Second, providers need to ask about established home bedtime routines and facilitate implementation in the hospital. Through collaboration with patients, providers can incorporate an individualized plan of care for sleep early in hospitalization.50 Partnering with nurses is also essential to creating a sleep-friendly environment that can improve patient experiences.51 Breathing exercises, meditating, listening to music and praying are all examples of “bedtime wind down” strategies recommended in sleep-specific CBT.49 Many of these could be successfully implemented in the hospital and may benefit other hospitalized patients too.52 In patients with PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) reduces nightmares, and if inpatients are on CPAP at home, it should be continued in the hospital.53

Pain

If sleep disturbance is the hallmark of PTSD,47 chronic pain is its coconspirator.15 Uncontrolled pain can make it much more difficult to treat patients with PTSD, which in turn may lead to further decompensation from a mental health standpoint.54 SUDs such as alcohol or opioid dependencies are highly comorbid with PTSD45 and introduce a layer of complexity when managing painin these patients. Providers should be thoughtful when electing to treat acute or chronic pain with opioids and take particular care to establish realistic therapeutic goals if doing so. While patients with PTSD have a greater likelihood of having an SUD, undertreating pain risks exacerbating underlying PTSD symptoms.

Nonpharmacologic therapies, which include communicating, listening, and expressing compassion and understanding, should be utilized by inpatient providers as a first-line treatment in patients with PTSD who suffer from pain. Additionally, relaxation techniques, physical therapy, and physical activity55 can be offered. Pharmacologically, nonopioid medications such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs should always be considered first. Should the use of opioids be deemed necessary, inpatient providers should preferentially use oral over intravenous medications and consider establishing a fixed timeframe for short-term opioids, which should be limited to a few days. Providers should communicate clear expectations with their patients to maximize the desired effect of any specific treatment while minimizing the risk of medication side effects with the goal of agreeing on a short yet effective treatment course.

Anxiety and Anger

One of the most challenging situations for the inpatient provider is encountering a patient who is anxious, angry, or hypervigilant. Mismatch between actual and expected communication between the provider and the patient can lead to frustration and anxiety. A trauma-informed care approach would suggest that frequent and thorough communication with patients may prevent or ameliorate the stresses and anxieties of hospitalization that may manifest as anger because of retraumatization. Hospitalizations usually lead to disruption of normal routine (eg, unpredictable meal times or medication administration), interrupted sleep (eg, woken up for blood draws or provider evaluation), and lack of control of schedule (eg, unsure of exact time when a procedure may be occurring), any of which may trigger symptoms of anxiety and anger in patients with PTSD and lead to hypervigilance.

If situations involving patient anxiety do arise, employ compassion and communication. Extra time spent with the patient, while challenging in the hectic hospital environment, is critical, and nonpharmacological treatments should be the priority. Engaging patients by asking about their PTSD triggers24 may help prevent exacerbations. For example, some patients may specify how they prefer to be woken up to prevent startle reactions. PTSD triggers can be reduced via effective communication with the entire healthcare team. Some immediate yet effective strategies are listening, validation, and negotiation. Benzodiazepine or antipsychotic usage should be avoided.36 Inpatient social work and comanagement with psychiatry involvement may be helpful in more severe exacerbations. A small observational study of patients hospitalized for severe PTSD found an association between walking more during hospitalization and fewer PTSD symptoms,56 suggesting that staying active could be helpful for inpatients with PTSD who are able to safely ambulate.

SUMMARY

PTSD is a common comorbidity among hospitalized patients in the United States. Typical hospital routines may exacerbate symptoms of PTSD such as anxiety and anger. Inpatient providers can play an important role in making hospitalizations go more smoothly for these patients by using principles consistent with trauma-informed care. Specifically, partnering with patients to construct a plan that preserves their sleep routines and accounts for potential triggers for decompensation can improve the hospital experience for patients with PTSD. Some PTSD interventions require additional investment from the healthcare system to deploy, such as staff training in trauma-informed care and reflective listening techniques. Electronic health record–based protocols and order sets for patients with PTSD can leverage available resources. Further research should evaluate hospital outcomes that result from a more tailored approach to the care of patients with PTSD. More effective, patient-centered PTSD care could lower rates of leaving against medical advice and improve the inpatient experience for patients and providers alike.

1. DSM-5 Fact Sheet: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. American Psychological Association. 2013. Accessed 30 July 2019. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/DSM/APA_DSM-5-PTSD.pdf

2. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

3. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

4. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

5. Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Schlenger WE, et al. The prevalence of lifetime and partial post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam theater veterans. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5(3):365-376. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050304

6. Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al. Trauma And the Vietnam War Generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazel; 1990.

7. Kang HK, Li B, Mahan CM, Eisen SA, Engel CC. Health of US veterans of 1991 Gulf War: a follow-up survey in 10 years. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51(4):401-410. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181a2feeb

8. Cohen BE, Gima K, Bertenthal D, Kim S, Marmar CR, Seal KH. Mental health diagnoses and utilization of VA non-mental health medical services among returning Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(1):18-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1117-3

9. VA MISSION Act. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2019. Accessed February 2, 2020. https://missionact.va.gov/

10. Fogarty CT, Sharma S, Chetty VK, Culpepper L. Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):398-407. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070082

11. Kartha A, Brower V, Saitz R, Samet JH, Keane TM, Liebschutz J. The impact of trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder on healthcare utilization among primary care patients. Med Care. 2008;46(4):388-393. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc5d2

12. Dobie DJ, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder screening status is associated with increased VA medical and surgical utilization in women. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 3):S58-S64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00376.x

13. Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, Beckham JC. Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2081-2086. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081

14. Frayne SM, Chiu VY, Iqbal S, et al. Medical care needs of returning veterans with PTSD: their other burden. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):33-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1497-4

15. Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Medical comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in US adults: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosom Med. 2011;73(8):697-707. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182303775

16. Vaccarino V, Goldberg J, Rooks C, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and incidence of coronary heart disease: a twin study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(11):970-978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.085

17. Bressi SK, Marcus SC, Solomon PL. The impact of psychiatric comorbidity on general hospital length of stay. Psychiatr Q. 2006;77(3):203-209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-006-9007-x

18. Haviland MG, Banta JE, Sonne JL, Przekop P. Posttraumatic stress disorder-related hospitalizations in the United States (2002-2011): Rates, co-occurring illnesses, suicidal ideation/self-harm, and hospital charges. J Nerv Men Dis. 2016;204(2):78-86. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000432

19. Frommberger U, Angenendt J, Berger M. Post-traumatic stress disorder--a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(5):59-65. https://doi.com/10.3238/arztebl.2014.0059

20. Sareen J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(9):460-467. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900902

21. Davydow DS, Gifford JM, Desai SV, Needham DM, Bienvenu OJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder in general intensive care unit survivors: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):421-434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.006

22. Griffiths J, Fortune G, Barber V, Young JD. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1506-1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z

23. Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):1121-1129. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882

24. Fletcher KE, Collins J, Holzhauer B, Lewis F, Hendricks M. Medical patients with PTSD identify issues with hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(6):1906-1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05480-y

25. Struble LM, Sullivan BJ, Hartman LS. Psychiatric disorders impacting critical illness. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2014;26(1):115-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2013.10.002

26. Baxter A. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the intensive care unit patient: implications for staff and advanced practice critical care nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2004;23(4):145-150. http://doi.org/10.1097/00003465-200407000-00001

27. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Preexisting comorbid psychiatric conditions and mortality in nonsurgical intensive care patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19(3):241-249. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2010967

28. Kebbe J, Lal A, El-Solh A, Jaoude P. Effects of PTSD on patient outcomes in the intensive care unit. Chest. 2015;148(4 Suppl):220A. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.2274366

29. Johnson KG, Rosen J. Re-emergence of posttraumatic stress disorder nightmares with nursing home admission: treatment with prazosin. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(2):130-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.007

30. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI. Is posttraumatic stress disorder underdiagnosed in routine clinical settings? J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187(7):420-428. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199907000-00005

31. Trauma-informed care. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015. Accessed July 30, 2019. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/healthier-pregnancy/preventive/trauma.html

32. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Department of Health & Human Services; 2014. HHS Publication No. SMA 14-4884. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

33. DeCandia CJ, Guarino K. Trauma-informed care: an ecological response. J Child Youth Care Work. 2015;24:7-32.

34. Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The PRIMARY CARE PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

35. Lee DJ, Schnitzlein CW, Wolf JP, Vythilingam M, Rasmusson AM, Hoge CW. Psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis to determine first-line treatments. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(9):792-806. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22511

36. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. 2017. Accessed July 22, 2019. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGClinicianSummaryFinal.pdf

37. Singh B, Hughes AJ, Mehta G, Erwin PJ, Parsaik AK. Efficacy of prazosin in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(4). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.16r01943

38. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507-517. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507598

39. El-Solh AA. Management of nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: current perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:409-420. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S166089

40. What is ROVER? Treatment Services. VA. 2018. Accessed February 14, 2020. https://www.houston.va.gov/docs/ROVERBrochure.pdf

41. Moser DK, Chung ML, McKinley S, et al. Critical care nursing practice regarding patient anxiety assessment and management. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19(5):276-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0964-3397(03)00061-2