User login

Retiform Purpura on the Buttocks in 6 Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients

To the Editor:

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

To the Editor:

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

To the Editor:

There is emerging evidence of skin findings in patients with COVID-19, including perniolike changes of the toes as well as urticarial and vesicular eruptions.1 Magro et al2 reported 3 cases of livedoid and purpuric skin eruptions in critically ill COVID-19 patients with evidence of thrombotic vasculopathy on skin biopsy, including a 32-year-old man with striking buttocks retiform purpura. Histopathologic analysis revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure-induced ischemic necrosis. Since that patient was first evaluated (March 2020), we identified 6 more cases of critically ill COVID-19 patients from a single academic hospital in New York City with essentially identical clinical findings. Herein, we report those 6 cases of critically ill and intubated patients with COVID-19 who developed retiform purpura on the buttocks only, approximately 11 to 21 days after onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

We provided consultation for 5 men and 1 woman (age range, 42–78 years) who were critically ill with COVID-19 and developed retiform purpura on the buttocks (Figures 1 and 2). All had an elevated D-dimer concentration: 2 patients, >700 ng/mL; 2 patients, >2000 ng/mL; 2 patients, >6000 ng/mL (reference, 229 ng/mL). Three patients experienced a peak D-dimer concentration on the day retiform purpura was reported.

Further evidence of coagulopathy in these patients included 1 patient with a newly diagnosed left popliteal deep vein thrombosis and 1 patient with a known history of protein C deficiency and deep vein thromboses. Five patients were receiving anticoagulation on the day the skin changes were documented; anticoagulation was contraindicated in the sixth patient because of oropharyngeal bleeding. Anticoagulation was continued at the treatment dosage (enoxaparin 80 mg twice daily) in 3 patients, and in 2 patients receiving a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin 40 mg daily), anticoagulation was escalated to treatment dose due to rising D-dimer levels and newly diagnosed retiform purpura. Skin biopsy was deferred for all patients due to positional and ventilatory restrictions. At that point in their care, 3 patients remained admitted on medicine floors, 2 were in the intensive care unit, and 1 had died.

Although the differential diagnosis for retiform purpura is broad and should be fully considered in any patient with this finding, based on the elevated D-dimer concentration, critical illness secondary to COVID-19, and striking similarity to earlier reported case of buttocks retiform purpura with thrombotic vasculopathy and pressure injury noted histopathologically,2 we suspect the buttocks retiform purpura in our 6 cases also represent a combination of cutaneous thrombosis and pressure injury. In addition to acral livedoid eruptions (also reported by Magro and colleagues2), we suspect that this cutaneous manifestation might be associated with a hypercoagulable state in some patients, especially in the setting of a rising D-dimer concentration. One study found that 31% of 184 patients with severe COVID-19 had thrombotic complications,3 a clinical picture that portends a poor prognosis.4

COVID-19 patients presenting with retiform purpura should be fully evaluated based on the broad differential for this morphology. We present 6 cases of buttocks retiform purpura in critically ill COVID-19 patients—all with strikingly similar morphologic findings, an elevated D-dimer concentration, and critical illness due to COVID-19—to alert clinicians to this constellation of findings and propose that this cutaneous manifestation could indicate an associated hypercoaguable state and should prompt a hematology consultation. Additionally, biopsy of this skin finding should be considered, especially if biopsy results might serve to guide management; however, obtaining a biopsy specimen can be technically difficult because of ventilatory requirements.

Given the magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic and the propensity of these patients to experience thrombotic events, recognition of this skin finding in COVID-19 is important and might allow timely intervention.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:e212-e213. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1-13. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145-147. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013

- Tang N, Li D, Wang X, et al. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:844-847. doi:10.1111/jth.14768

Practice Points

- Retiform purpura in a severely ill patient with COVID-19 and a markedly elevated D-dimer concentration might be a cutaneous sign of systemic coagulopathy.

- This constellation of findings should prompt consideration of skin biopsy and hematology consultation.

Comparison of Dermatologist Ratings on Health Care–Specific and General Consumer Websites

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

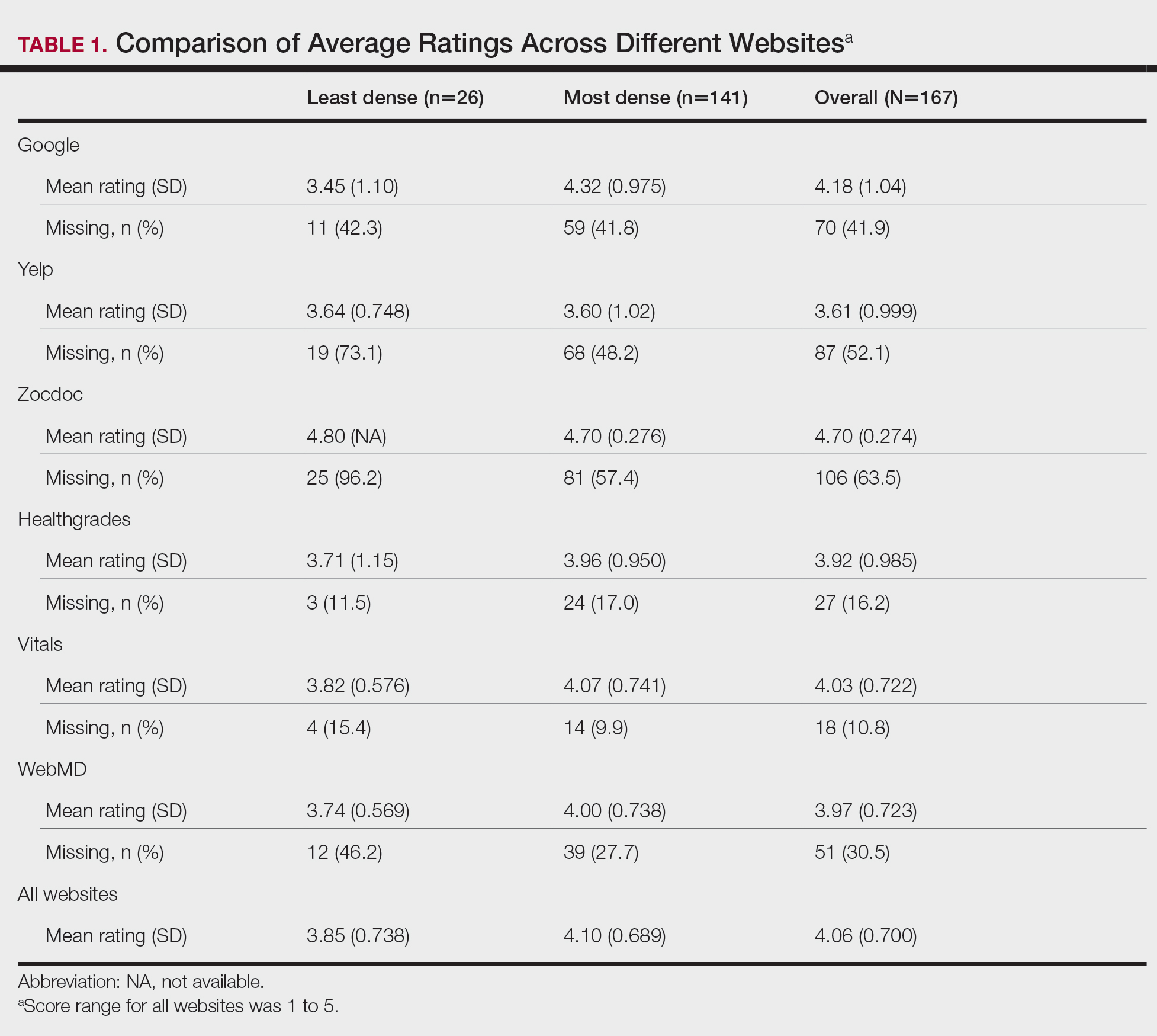

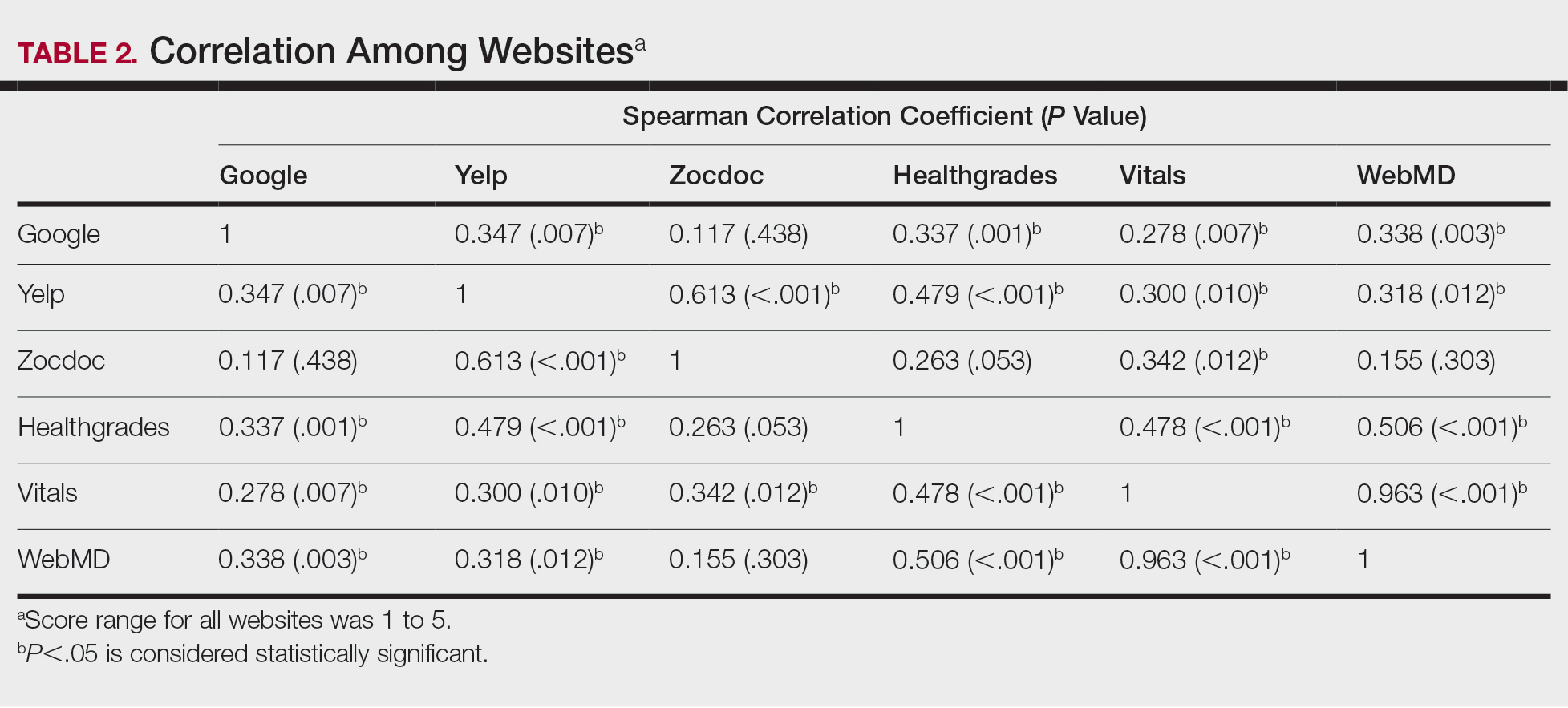

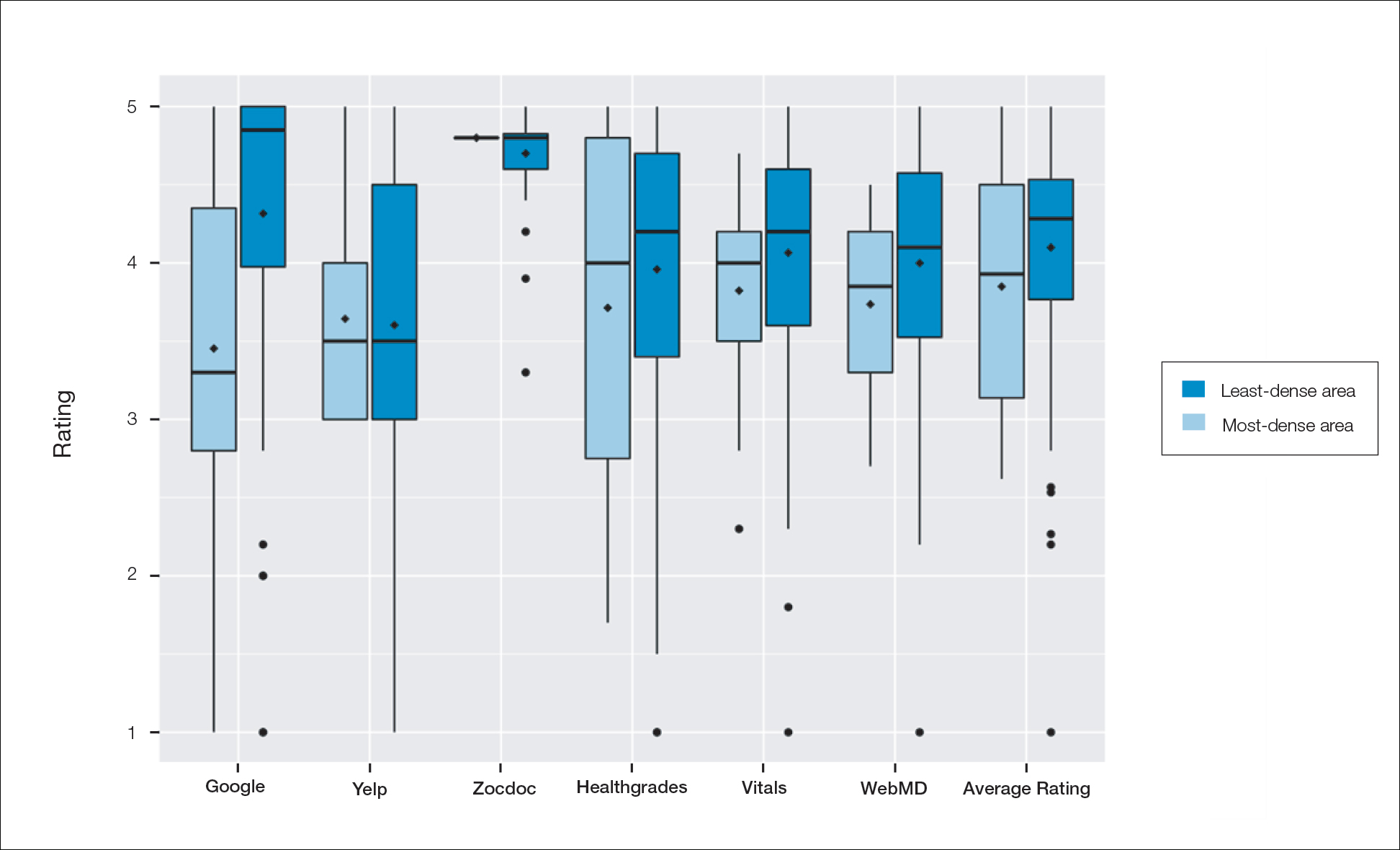

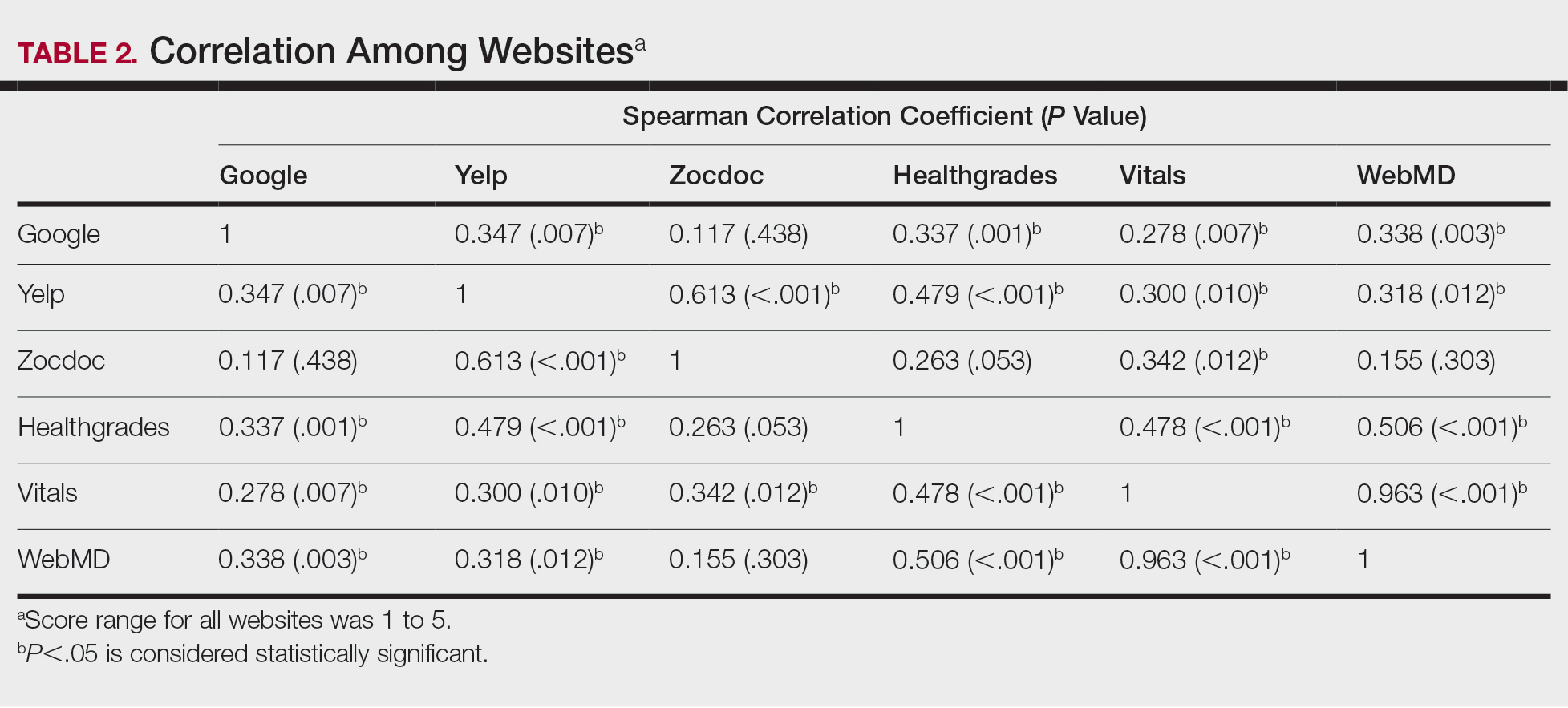

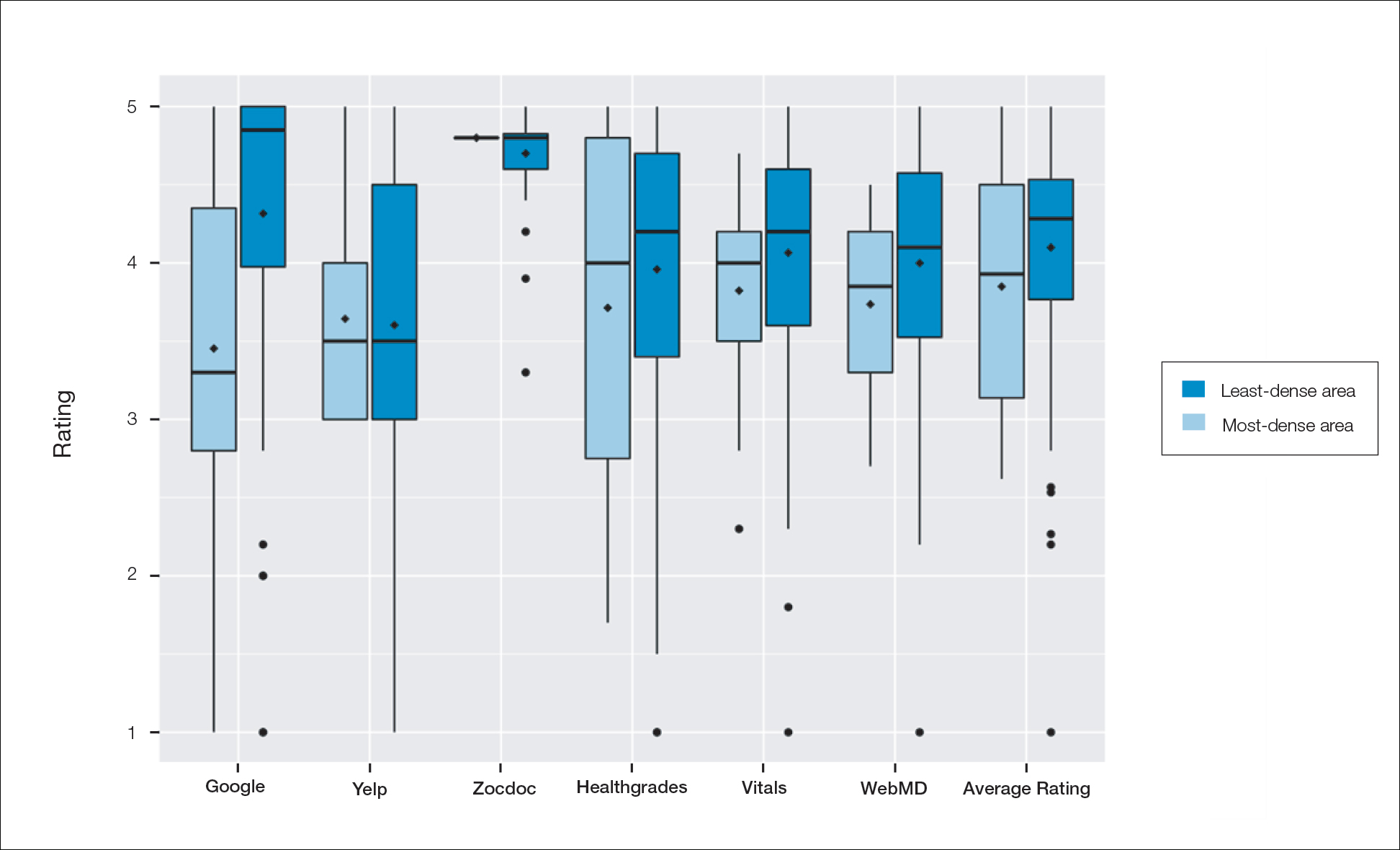

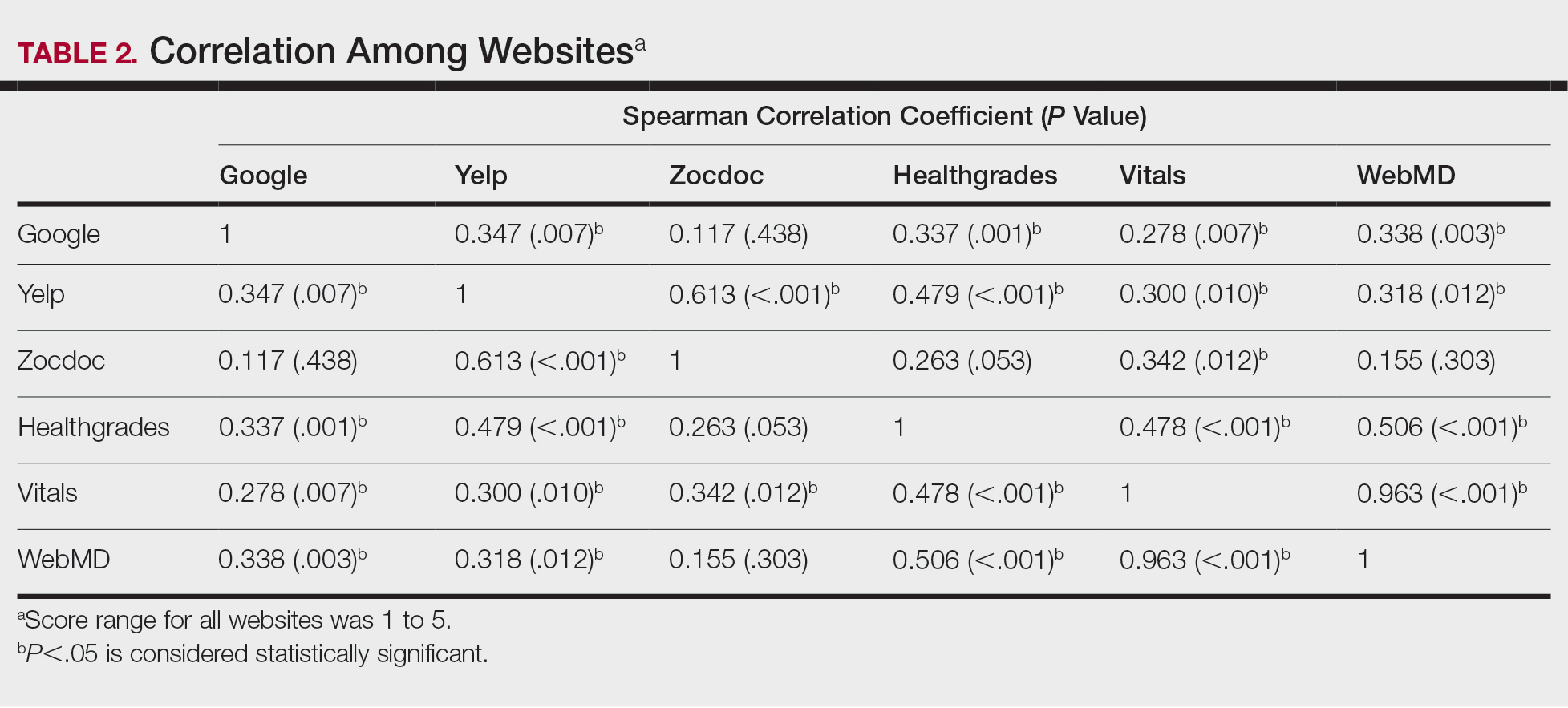

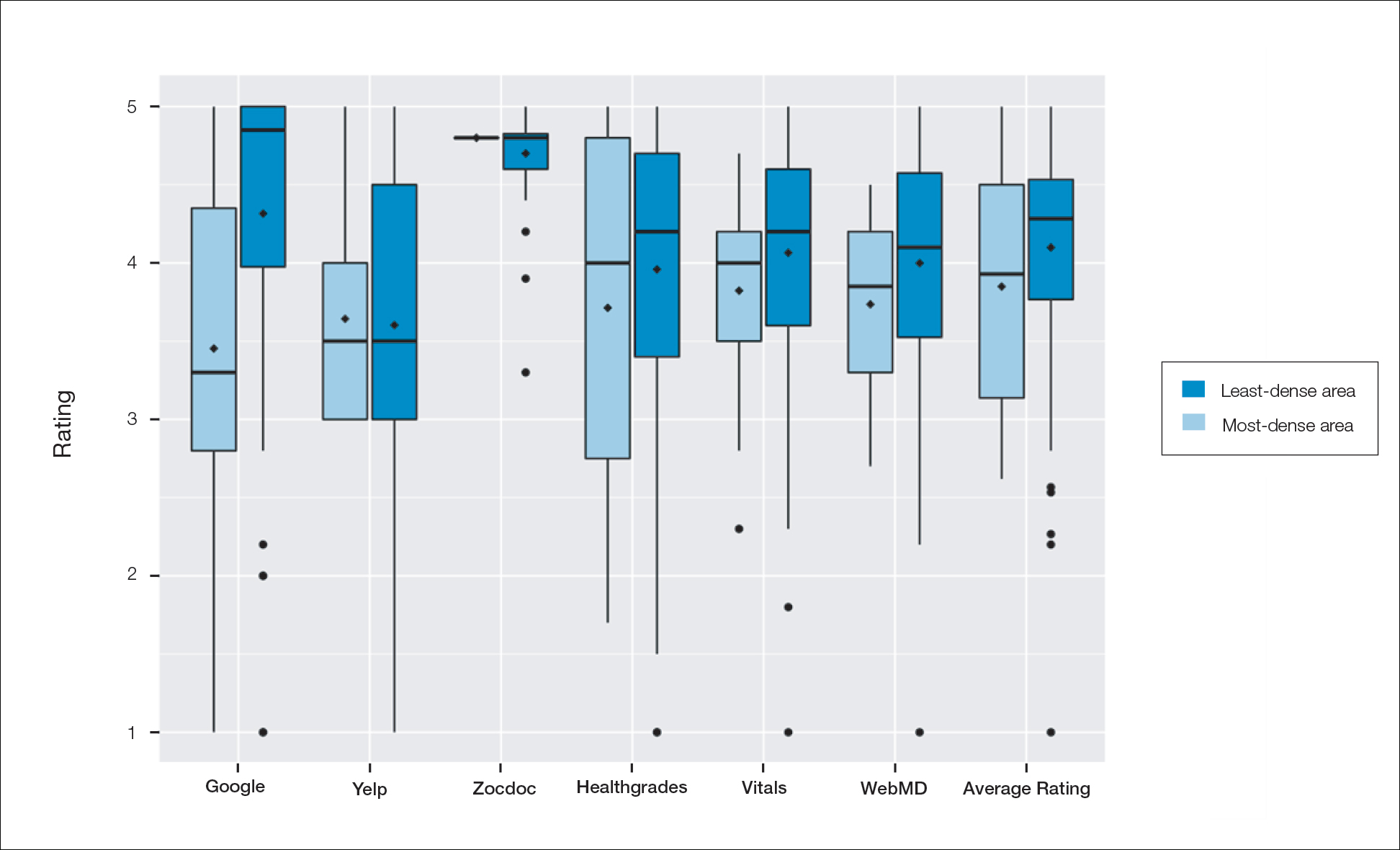

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

Health care–specific (eg, Healthgrades, Zocdoc, Vitals, WebMD) and general consumer websites (eg, Google, Yelp) are popular platforms for patients to find physicians, schedule appointments, and review physician experiences. Patients find ratings on these websites more trustworthy than standardized surveys distributed by hospitals, but many physicians do not trust the reviews on these sites. For example, in a survey of both physicians (n=828) and patients (n=494), 36% of physicians trusted online reviews compared to 57% of patients.1 The objective of this study was to determine if health care–specific or general consumer websites more accurately reflect overall patient sentiment. This knowledge can help physicians who are seeking to improve the patient experience understand which websites have more accurate and trustworthy reviews.

Methods

A list of dermatologists from the top 10 most and least dermatologist–dense areas in the United States was compiled to examine different physician populations.2 Equal numbers of male and female dermatologists were randomly selected from the most dense areas. All physicians were included from the least dense areas because of limited sample size. Ratings were collected from websites most likely to appear on the first page of a Google search for a physician name, as these are most likely to be seen by patients. Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the study population; mean and median physician rating (using a scale of 1–5); SD; and minimum, maximum, and interquartile ranges. Spearman correlation coefficients were generated to examine the strength of association between ratings from website pairs. P<.05 was considered statistically significant, with analyses performed in R (3.6.2) for Windows (the R Foundation).

Results

A total of 167 representative physicians were included in this analysis; 141 from the most dense areas, and 26 from the least dense areas. The lowest average ratings for the entire sample and most dermatologist–dense areas were found on Yelp (3.61 and 3.60, respectively), and the lowest ratings in the least dermatologist–dense areas were found on Google (3.45)(Table 1). Correlation coefficient values were lowest for Zocdoc and Healthgrades (0.263) and highest for Vitals and WebMD (0.963)(Table 2). The health care–specific sites were closer to the overall average (4.06) than the general consumer sites (eFigure).

Comment

Although dermatologist ratings on each site had a broad range, we found that patients typically expressed negative interactions on general consumer websites rather than health care–specific websites. When comparing the ratings of the same group of dermatologists across different sites, ratings on health care–specific sites had a higher degree of correlation, with physician ratings more similar between 2 health care–specific sites and less similar between a health care–specific and a general consumer website. This pattern was consistent in both dermatologist-dense and dermatologist-poor areas, despite patients having varying levels of access to dermatologic care and medical resources and potentially different regional preferences of consumer websites. Taken together, these findings imply that health care–specific websites more consistently reflect overall patient sentiment.

Although one 2016 study comparing reviews of dermatology practices on Zocdoc and Yelp also demonstrated lower average ratings on Yelp,3 our study suggests that this trend is not isolated to these 2 sites but can be seen when comparing many health care–specific sites vs general consumer sites.

Our study compared ratings of dermatologists among popular websites to understand those that are most representative of patient attitudes toward physicians. These findings are important because online reviews reflect the entire patient experience, not just the patient-physician interaction, which may explain why physician scores on standardized questionnaires, such as Press Ganey surveys, do not correlate well with their online reviews.4 In a study comparing 98 physicians with negative online ratings to 82 physicians in similar departments with positive ratings, there was no significant difference in scores on patient-physician interaction questions on the Press Ganey survey.5 However, physicians who received negative online reviews scored lower on Press Ganey questions related to nonphysician interactions (eg, office cleanliness, interactions with staff).

The current study was subject to several limitations. Our analysis included all physicians in our random selection without accounting for those physicians with a greater online presence who might be more cognizant of these ratings and try to manipulate them through a reputation-management company or public relations consultant.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that consumer websites are not primarily used by disgruntled patients wishing to express grievances; instead, on average, most physicians received positive reviews. Furthermore, health care–specific websites show a higher degree of concordance than and may more accurately reflect overall patient attitudes toward their physicians than general consumer sites. Reviews from these health care–specific sites may be more helpful than general consumer websites in allowing physicians to understand patient sentiment and improve patient experiences.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38:e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52

- Waqas B, Cooley V, Lipner SR. Association of sex, location, and experience with online patient ratings of dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:954-955.

- Smith RJ, Lipoff JB. Evaluation of dermatology practice online reviews: lessons from qualitative analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:153-157. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3950

- Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, et al. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1-6.

- Widmer RJ, Maurer MJ, Nayar VR, et al. Online physician reviews do not reflect patient satisfaction survey responses. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93:453-457.

Practice Points

- Online physician-rating websites are commonly used by patients to find physicians and review experiences.

- Health care–specific sites may more accurately reflect patient sentiment than general consumer sites.

- Dermatologists can use health care–specific sites to understand patient sentiment and learn how to improve patient experiences.