User login

Things We Do for No Reason – The “48 Hour Rule-out” for Well-Appearing Febrile Infants

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 3-week-old, full-term term male febrile infant was evaluated in the emergency department (ED). On the day of admission, he was noted to feel warm to the touch and was found to have a rectal temperature of 101.3°F (38.3°C) at home.

In the ED, the patient was well appearing and had normal physical exam findings. His workup in the ED included a normal chest radiograph, complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (cell count, protein, and glucose), and urinalysis. Blood, CSF, and catheterized urine cultures were collected, and he was admitted to the hospital on parenteral antibiotics. His provider informed the parents that the infant would be observed in the hospital for 48 hours while monitoring the bacterial cultures. Is it necessary for the hospitalization of this child to last a full 48 hours?

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation and management of fever (T ≥ 38°C) is a common cause of emergency department visits and accounts for up to 20% of pediatric emergency visits.2

Why You Might Think Hospitalization for at Least 48 Hours is Necessary

The evaluation and management of fever in infants aged less than 90 days is challenging due to concern for occult serious bacterial infections. In particular, providers may be concerned that the physical exam lacks sensitivity.9

There is also a perceived risk of poor outcomes in young infants if a serious bacterial infection is missed. For these reasons, the evaluation and management of febrile infants has been characterized by practice variability in both outpatient10 and ED3 settings.

Commonly used febrile infant management protocols vary in approach and do not provide clear guidelines on the recommended duration of hospitalization and empiric antimicrobial treatment.11-14 Length of hospitalization was widely studied in infants between 1979 and 1999, and results showed that the majority of clinically important bacterial pathogens can be detected within 48 hours.15-17 Many textbooks and online references, based on this literature, continue to support 48 to 72 hours of observation and empiric antimicrobial treatment for febrile infants.18,19 A 2012 AAP Clinical Report advocated for limiting the antimicrobial treatment in low-risk infants suspected of early-onset sepsis to 48 hours.20

Why Shorten the Period of In-Hospital Observation to a Maximum of 36 Hours of Culture Incubation

Discharge of low-risk infants with negative enhanced urinalysis and negative bacterial cultures at 36 hours or earlier can reduce costs21 and potentially preventable harm (eg, intravenous catheter complications, nosocomial infections) without negatively impacting patient outcomes.22 Early discharge is also patient-centered, given the stress and indirect costs associated with hospitalization, including potential separation of a breastfeeding infant and mother, lost wages from time off work, or childcare for well siblings.23

Initial studies that evaluated the time-to-positivity (TTP) of bacterial cultures in febrile infants predate the use of continuous monitoring systems for blood cultures. Traditional bacterial culturing techniques require direct observation of broth turbidity and subsequent subculturing onto chocolate and sheep blood agar, typically occurring only once daily.24 Current commercially available continuous monitoring bacterial culture systems decrease TTP by immediately alerting laboratory technicians to bacterial growth through the detection of 14CO2 released by organisms utilizing radiolabeled glucose in growth media.24 In addition, many studies supporting the evaluation of febrile infants in the hospital for a 48-hour period include those in ICU settings,25 with medically complex histories,24 and aged < 28 days admitted in the NICU,15 where pathogens with longer incubation times are frequently seen.

In a recent single-center retrospective study, infant blood cultures with TTP longer than 36 hours are 7.8 times more likely to be identified as contaminant bacteria compared with cultures that tested positive in <36 hours.26 Even if bacterial cultures were unexpectedly positive after 36 hours, which occurs in less than 1.1% of all infants and 0.3% of low-risk infants,1 these patients do not have adverse outcomes. Infants who were deemed low risk based on established criteria and who had bacterial cultures positive for pathogenic bacteria were treated at that time and recovered uneventfully.7, 31

CSF and urine cultures are often reviewed only once or twice daily in most institutions, and this practice artificially prolongs the TTP for pathogenic bacteria. Small sample-sized studies have demonstrated the low detection rate of pathogens in CSF and urine cultures beyond 36 hours. Evans et al. found that in infants aged 0-28 days, 0.03% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures tested positive after 36 hours.26 In a retrospective study of infants aged 28-90 days in the ED setting, Kaplan et al. found that 0.9% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures were positive at >24 hours.1 For well-appearing infants who have reassuring initial CSF studies, the risk of meningitis is extremely low.7 Management criteria for febrile infants provide guidance for determining those infants with abnormal CSF results who may benefit from longer periods of observation.

Urinary tract infections are common serious bacterial infections in this age group. Enhanced urinalysis, in which cell count and Gram stain analysis are performed on uncentrifuged urine, shows 96% sensitivity of predicting urinary tract infection and can provide additional reassurance for well-appearing infants who are discharged prior to 48 hours.27

When a Longer Observation Period May Be Warranted

What You Should Do Instead: Limit Hospitalization to a Maximum of 36 Hours

For well-appearing febrile infants between 0–90 days of age hospitalized for observation and awaiting bacterial culture results, providers should consider discharge at 36 hours or less, rather than 48 hours, if blood, urine, and CSF cultures do not show bacterial growth. In a large health system, researchers implemented an evidence-based care process model for febrile infants to provide specific guidelines for laboratory testing, criteria for admission, and recommendation for discontinuation of empiric antibiotics and discharge after 36 hours in infants with negative bacterial cultures. These changes led to a 27% reduction in the length of hospital stay and 23% reduction in inpatient costs without any cases of missed bacteremia.21 The reduction in the in-hospital observation duration to 24 hours of culture incubation for well-appearing febrile infants has been advocated 32 and is a common practice for infants with appropriate follow up and parental assurance. This recommendation is supported by the following:

- Recent data showing the overwhelming majority of pathogens will be identified by blood culture <24 hours in infants aged 0-90 days32 with blood culture TTP in infants aged 0-30 days being either no different26 or potentially shorter32

- Studies showing that infants meeting low-risk clinical and laboratory profiles further reduce the likelihood of identifying serious bacterial infection after 24 hours to 0.3%.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Determine if febrile infants aged 0-90 days are at low risk for serious bacterial infection and obtain appropriate bacterial cultures.

- If hospitalized for observation, discharge low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days after 36 hours or less if bacterial cultures remain negative.

- If hospitalized for observation, consider reducing the length of inpatient observation for low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days with reliable follow-up to 24 hours or less when the culture results are negative.

CONCLUSION

Monitoring patients in the hospital for greater than 36 hours of bacterial culture incubation is unnecessary for patients similar to the 3 week-old full-term infant in the case presentation, who are at low risk for serious bacterial infection based on available scoring systems and have negative cultures. If patients are not deemed low risk, have an incomplete laboratory evaluation, or have had prior antibiotic treatment, longer observation in the hospital may be warranted. Close reassessment of the rare patients whose blood cultures return positive after 36 hours is necessary, but their outcomes are excellent, especially in well-appearing infants.7,33

What do you do?

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailingTWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work reported by any of the authors.

1. Kaplan RL, Harper MB, Baskin MN, Macone AB, Mandl KD. Time to detection of positive cultures in 28- to 90-day-old febrile infants. Pediatrics 2000;106(6):E74. PubMed

2. Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

3. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Williams DJ, et al. Association of clinical practice guidelines with emergency department management of febrile infants </=56 days of age. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358-365. PubMed

4. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2012;205:1-297. PubMed

5. Garcia S, Mintegi S, Gomez B, et al. Is 15 days an appropriate cut-off age for considering serious bacterial infection in the management of febrile infants? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):455-458. PubMed

6. Schwartz S, Raveh D, Toker O, Segal G, Godovitch N, Schlesinger Y. A week-by-week analysis of the low-risk criteria for serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(4):287-292. PubMed

7. Huppler AR, Eickhoff JC, Wald ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010;125(2):228-233. PubMed

8. Baskin MN. The prevalence of serious bacterial infections by age in febrile infants during the first 3 months of life. Pediatr Ann. 1993;22(8):462-466. PubMed

9. Nigrovic LE, Mahajan PV, Blumberg SM, et al. The Yale Observation Scale Score and the risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants. Pediatrics 2017;140(1):e20170695. PubMed

10. Bergman DA, Mayer ML, Pantell RH, Finch SA, Wasserman RC. Does clinical presentation explain practice variability in the treatment of febrile infants? Pediatrics 2006;117(3):787-795. PubMed

11. Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1437-1441. PubMed

12. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection--an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94(3):390-396. PubMed

13. Baskin MN, O’Rourke EJ, Fleisher GR. Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):22-27. PubMed

14. Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics 2001;108(2):311-316. PubMed

15. Pichichero ME, Todd JK. Detection of neonatal bacteremia. J Pediatr. 1979;94(6):958-960. PubMed

16. Hurst MK, Yoder BA. Detection of bacteremia in young infants: is 48 hours adequate? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(8):711-713. PubMed

17. Friedman J, Matlow A. Time to identification of positive bacterial cultures in infants under three months of age hospitalized to rule out sepsis. Paediatr Child Health 1999;4(5):331-334. PubMed

18. Kliegman R, Behrman RE, Nelson WE. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Edition 20 / ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

19. Fever in infants and children. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, 2016. (Accessed 27 Nov 2016, 2016, at https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/symptoms-in-infants-and-children/fever-in-infants-and-children.)

20. Polin RA, Committee on F, Newborn. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2012;129(5):1006-1015. PubMed

21. Byington CL, Reynolds CC, Korgenski K, et al. Costs and infant outcomes after implementation of a care process model for febrile infants. Pediatrics 2012;130(1):e16-e24. PubMed

22. DeAngelis C, Joffe A, Wilson M, Willis E. Iatrogenic risks and financial costs of hospitalizing febrile infants. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137(12):1146-1149. PubMed

23. Nizam M, Norzila MZ. Stress among parents with acutely ill children. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56(4):428-434. PubMed

24. Rowley AH, Wald ER. The incubation period necessary for detection of bacteremia in immunocompetent children with fever. Implications for the clinician. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986;25(10):485-489. PubMed

25. La Scolea LJ, Jr., Dryja D, Sullivan TD, Mosovich L, Ellerstein N, Neter E. Diagnosis of bacteremia in children by quantitative direct plating and a radiometric procedure. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13(3):478-482. PubMed

26. Evans RC, Fine BR. Time to detection of bacterial cultures in infants aged 0 to 90 days. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):97-102. PubMed

27. Herr SM, Wald ER, Pitetti RD, Choi SS. Enhanced urinalysis improves identification of febrile infants ages 60 days and younger at low risk for serious bacterial illness. Pediatrics 2001;108(4):866-871. PubMed

28. Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Macias CG, et al. Clinical prediction rule for identifying children with cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis at very low risk of bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2007;297(1):52-60. PubMed

29. Doby EH, Stockmann C, Korgenski EK, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in febrile infants 1-90 days with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(9):1024-1026. PubMed

30. Bhansali P, Wiedermann BL, Pastor W, McMillan J, Shah N. Management of hospitalized febrile neonates without CSF analysis: A study of US pediatric hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):528-533. PubMed

31. Kanegaye JT, Soliemanzadeh P, Bradley JS. Lumbar puncture in pediatric bacterial meningitis: defining the time interval for recovery of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens after parenteral antibiotic pretreatment. Pediatrics 2001;108(5):1169-1174. PubMed

32. Biondi EA, Mischler M, Jerardi KE, et al. Blood culture time to positivity in febrile infants with bacteremia. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):844-849. PubMed

33. Moher D HC, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A. Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Infants (0–3 Months). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 205. In: Center OE-bP, ed. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 3-week-old, full-term term male febrile infant was evaluated in the emergency department (ED). On the day of admission, he was noted to feel warm to the touch and was found to have a rectal temperature of 101.3°F (38.3°C) at home.

In the ED, the patient was well appearing and had normal physical exam findings. His workup in the ED included a normal chest radiograph, complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (cell count, protein, and glucose), and urinalysis. Blood, CSF, and catheterized urine cultures were collected, and he was admitted to the hospital on parenteral antibiotics. His provider informed the parents that the infant would be observed in the hospital for 48 hours while monitoring the bacterial cultures. Is it necessary for the hospitalization of this child to last a full 48 hours?

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation and management of fever (T ≥ 38°C) is a common cause of emergency department visits and accounts for up to 20% of pediatric emergency visits.2

Why You Might Think Hospitalization for at Least 48 Hours is Necessary

The evaluation and management of fever in infants aged less than 90 days is challenging due to concern for occult serious bacterial infections. In particular, providers may be concerned that the physical exam lacks sensitivity.9

There is also a perceived risk of poor outcomes in young infants if a serious bacterial infection is missed. For these reasons, the evaluation and management of febrile infants has been characterized by practice variability in both outpatient10 and ED3 settings.

Commonly used febrile infant management protocols vary in approach and do not provide clear guidelines on the recommended duration of hospitalization and empiric antimicrobial treatment.11-14 Length of hospitalization was widely studied in infants between 1979 and 1999, and results showed that the majority of clinically important bacterial pathogens can be detected within 48 hours.15-17 Many textbooks and online references, based on this literature, continue to support 48 to 72 hours of observation and empiric antimicrobial treatment for febrile infants.18,19 A 2012 AAP Clinical Report advocated for limiting the antimicrobial treatment in low-risk infants suspected of early-onset sepsis to 48 hours.20

Why Shorten the Period of In-Hospital Observation to a Maximum of 36 Hours of Culture Incubation

Discharge of low-risk infants with negative enhanced urinalysis and negative bacterial cultures at 36 hours or earlier can reduce costs21 and potentially preventable harm (eg, intravenous catheter complications, nosocomial infections) without negatively impacting patient outcomes.22 Early discharge is also patient-centered, given the stress and indirect costs associated with hospitalization, including potential separation of a breastfeeding infant and mother, lost wages from time off work, or childcare for well siblings.23

Initial studies that evaluated the time-to-positivity (TTP) of bacterial cultures in febrile infants predate the use of continuous monitoring systems for blood cultures. Traditional bacterial culturing techniques require direct observation of broth turbidity and subsequent subculturing onto chocolate and sheep blood agar, typically occurring only once daily.24 Current commercially available continuous monitoring bacterial culture systems decrease TTP by immediately alerting laboratory technicians to bacterial growth through the detection of 14CO2 released by organisms utilizing radiolabeled glucose in growth media.24 In addition, many studies supporting the evaluation of febrile infants in the hospital for a 48-hour period include those in ICU settings,25 with medically complex histories,24 and aged < 28 days admitted in the NICU,15 where pathogens with longer incubation times are frequently seen.

In a recent single-center retrospective study, infant blood cultures with TTP longer than 36 hours are 7.8 times more likely to be identified as contaminant bacteria compared with cultures that tested positive in <36 hours.26 Even if bacterial cultures were unexpectedly positive after 36 hours, which occurs in less than 1.1% of all infants and 0.3% of low-risk infants,1 these patients do not have adverse outcomes. Infants who were deemed low risk based on established criteria and who had bacterial cultures positive for pathogenic bacteria were treated at that time and recovered uneventfully.7, 31

CSF and urine cultures are often reviewed only once or twice daily in most institutions, and this practice artificially prolongs the TTP for pathogenic bacteria. Small sample-sized studies have demonstrated the low detection rate of pathogens in CSF and urine cultures beyond 36 hours. Evans et al. found that in infants aged 0-28 days, 0.03% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures tested positive after 36 hours.26 In a retrospective study of infants aged 28-90 days in the ED setting, Kaplan et al. found that 0.9% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures were positive at >24 hours.1 For well-appearing infants who have reassuring initial CSF studies, the risk of meningitis is extremely low.7 Management criteria for febrile infants provide guidance for determining those infants with abnormal CSF results who may benefit from longer periods of observation.

Urinary tract infections are common serious bacterial infections in this age group. Enhanced urinalysis, in which cell count and Gram stain analysis are performed on uncentrifuged urine, shows 96% sensitivity of predicting urinary tract infection and can provide additional reassurance for well-appearing infants who are discharged prior to 48 hours.27

When a Longer Observation Period May Be Warranted

What You Should Do Instead: Limit Hospitalization to a Maximum of 36 Hours

For well-appearing febrile infants between 0–90 days of age hospitalized for observation and awaiting bacterial culture results, providers should consider discharge at 36 hours or less, rather than 48 hours, if blood, urine, and CSF cultures do not show bacterial growth. In a large health system, researchers implemented an evidence-based care process model for febrile infants to provide specific guidelines for laboratory testing, criteria for admission, and recommendation for discontinuation of empiric antibiotics and discharge after 36 hours in infants with negative bacterial cultures. These changes led to a 27% reduction in the length of hospital stay and 23% reduction in inpatient costs without any cases of missed bacteremia.21 The reduction in the in-hospital observation duration to 24 hours of culture incubation for well-appearing febrile infants has been advocated 32 and is a common practice for infants with appropriate follow up and parental assurance. This recommendation is supported by the following:

- Recent data showing the overwhelming majority of pathogens will be identified by blood culture <24 hours in infants aged 0-90 days32 with blood culture TTP in infants aged 0-30 days being either no different26 or potentially shorter32

- Studies showing that infants meeting low-risk clinical and laboratory profiles further reduce the likelihood of identifying serious bacterial infection after 24 hours to 0.3%.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Determine if febrile infants aged 0-90 days are at low risk for serious bacterial infection and obtain appropriate bacterial cultures.

- If hospitalized for observation, discharge low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days after 36 hours or less if bacterial cultures remain negative.

- If hospitalized for observation, consider reducing the length of inpatient observation for low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days with reliable follow-up to 24 hours or less when the culture results are negative.

CONCLUSION

Monitoring patients in the hospital for greater than 36 hours of bacterial culture incubation is unnecessary for patients similar to the 3 week-old full-term infant in the case presentation, who are at low risk for serious bacterial infection based on available scoring systems and have negative cultures. If patients are not deemed low risk, have an incomplete laboratory evaluation, or have had prior antibiotic treatment, longer observation in the hospital may be warranted. Close reassessment of the rare patients whose blood cultures return positive after 36 hours is necessary, but their outcomes are excellent, especially in well-appearing infants.7,33

What do you do?

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailingTWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work reported by any of the authors.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

CASE PRESENTATION

A 3-week-old, full-term term male febrile infant was evaluated in the emergency department (ED). On the day of admission, he was noted to feel warm to the touch and was found to have a rectal temperature of 101.3°F (38.3°C) at home.

In the ED, the patient was well appearing and had normal physical exam findings. His workup in the ED included a normal chest radiograph, complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (cell count, protein, and glucose), and urinalysis. Blood, CSF, and catheterized urine cultures were collected, and he was admitted to the hospital on parenteral antibiotics. His provider informed the parents that the infant would be observed in the hospital for 48 hours while monitoring the bacterial cultures. Is it necessary for the hospitalization of this child to last a full 48 hours?

INTRODUCTION

Evaluation and management of fever (T ≥ 38°C) is a common cause of emergency department visits and accounts for up to 20% of pediatric emergency visits.2

Why You Might Think Hospitalization for at Least 48 Hours is Necessary

The evaluation and management of fever in infants aged less than 90 days is challenging due to concern for occult serious bacterial infections. In particular, providers may be concerned that the physical exam lacks sensitivity.9

There is also a perceived risk of poor outcomes in young infants if a serious bacterial infection is missed. For these reasons, the evaluation and management of febrile infants has been characterized by practice variability in both outpatient10 and ED3 settings.

Commonly used febrile infant management protocols vary in approach and do not provide clear guidelines on the recommended duration of hospitalization and empiric antimicrobial treatment.11-14 Length of hospitalization was widely studied in infants between 1979 and 1999, and results showed that the majority of clinically important bacterial pathogens can be detected within 48 hours.15-17 Many textbooks and online references, based on this literature, continue to support 48 to 72 hours of observation and empiric antimicrobial treatment for febrile infants.18,19 A 2012 AAP Clinical Report advocated for limiting the antimicrobial treatment in low-risk infants suspected of early-onset sepsis to 48 hours.20

Why Shorten the Period of In-Hospital Observation to a Maximum of 36 Hours of Culture Incubation

Discharge of low-risk infants with negative enhanced urinalysis and negative bacterial cultures at 36 hours or earlier can reduce costs21 and potentially preventable harm (eg, intravenous catheter complications, nosocomial infections) without negatively impacting patient outcomes.22 Early discharge is also patient-centered, given the stress and indirect costs associated with hospitalization, including potential separation of a breastfeeding infant and mother, lost wages from time off work, or childcare for well siblings.23

Initial studies that evaluated the time-to-positivity (TTP) of bacterial cultures in febrile infants predate the use of continuous monitoring systems for blood cultures. Traditional bacterial culturing techniques require direct observation of broth turbidity and subsequent subculturing onto chocolate and sheep blood agar, typically occurring only once daily.24 Current commercially available continuous monitoring bacterial culture systems decrease TTP by immediately alerting laboratory technicians to bacterial growth through the detection of 14CO2 released by organisms utilizing radiolabeled glucose in growth media.24 In addition, many studies supporting the evaluation of febrile infants in the hospital for a 48-hour period include those in ICU settings,25 with medically complex histories,24 and aged < 28 days admitted in the NICU,15 where pathogens with longer incubation times are frequently seen.

In a recent single-center retrospective study, infant blood cultures with TTP longer than 36 hours are 7.8 times more likely to be identified as contaminant bacteria compared with cultures that tested positive in <36 hours.26 Even if bacterial cultures were unexpectedly positive after 36 hours, which occurs in less than 1.1% of all infants and 0.3% of low-risk infants,1 these patients do not have adverse outcomes. Infants who were deemed low risk based on established criteria and who had bacterial cultures positive for pathogenic bacteria were treated at that time and recovered uneventfully.7, 31

CSF and urine cultures are often reviewed only once or twice daily in most institutions, and this practice artificially prolongs the TTP for pathogenic bacteria. Small sample-sized studies have demonstrated the low detection rate of pathogens in CSF and urine cultures beyond 36 hours. Evans et al. found that in infants aged 0-28 days, 0.03% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures tested positive after 36 hours.26 In a retrospective study of infants aged 28-90 days in the ED setting, Kaplan et al. found that 0.9% of urine cultures and no CSF cultures were positive at >24 hours.1 For well-appearing infants who have reassuring initial CSF studies, the risk of meningitis is extremely low.7 Management criteria for febrile infants provide guidance for determining those infants with abnormal CSF results who may benefit from longer periods of observation.

Urinary tract infections are common serious bacterial infections in this age group. Enhanced urinalysis, in which cell count and Gram stain analysis are performed on uncentrifuged urine, shows 96% sensitivity of predicting urinary tract infection and can provide additional reassurance for well-appearing infants who are discharged prior to 48 hours.27

When a Longer Observation Period May Be Warranted

What You Should Do Instead: Limit Hospitalization to a Maximum of 36 Hours

For well-appearing febrile infants between 0–90 days of age hospitalized for observation and awaiting bacterial culture results, providers should consider discharge at 36 hours or less, rather than 48 hours, if blood, urine, and CSF cultures do not show bacterial growth. In a large health system, researchers implemented an evidence-based care process model for febrile infants to provide specific guidelines for laboratory testing, criteria for admission, and recommendation for discontinuation of empiric antibiotics and discharge after 36 hours in infants with negative bacterial cultures. These changes led to a 27% reduction in the length of hospital stay and 23% reduction in inpatient costs without any cases of missed bacteremia.21 The reduction in the in-hospital observation duration to 24 hours of culture incubation for well-appearing febrile infants has been advocated 32 and is a common practice for infants with appropriate follow up and parental assurance. This recommendation is supported by the following:

- Recent data showing the overwhelming majority of pathogens will be identified by blood culture <24 hours in infants aged 0-90 days32 with blood culture TTP in infants aged 0-30 days being either no different26 or potentially shorter32

- Studies showing that infants meeting low-risk clinical and laboratory profiles further reduce the likelihood of identifying serious bacterial infection after 24 hours to 0.3%.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Determine if febrile infants aged 0-90 days are at low risk for serious bacterial infection and obtain appropriate bacterial cultures.

- If hospitalized for observation, discharge low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days after 36 hours or less if bacterial cultures remain negative.

- If hospitalized for observation, consider reducing the length of inpatient observation for low-risk febrile infants aged 0–90 days with reliable follow-up to 24 hours or less when the culture results are negative.

CONCLUSION

Monitoring patients in the hospital for greater than 36 hours of bacterial culture incubation is unnecessary for patients similar to the 3 week-old full-term infant in the case presentation, who are at low risk for serious bacterial infection based on available scoring systems and have negative cultures. If patients are not deemed low risk, have an incomplete laboratory evaluation, or have had prior antibiotic treatment, longer observation in the hospital may be warranted. Close reassessment of the rare patients whose blood cultures return positive after 36 hours is necessary, but their outcomes are excellent, especially in well-appearing infants.7,33

What do you do?

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason”? Let us know what you do in your practice and propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics. Please join in the conversation online at Twitter (#TWDFNR)/Facebook and don’t forget to “Like It” on Facebook or retweet it on Twitter. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailingTWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work reported by any of the authors.

1. Kaplan RL, Harper MB, Baskin MN, Macone AB, Mandl KD. Time to detection of positive cultures in 28- to 90-day-old febrile infants. Pediatrics 2000;106(6):E74. PubMed

2. Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

3. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Williams DJ, et al. Association of clinical practice guidelines with emergency department management of febrile infants </=56 days of age. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358-365. PubMed

4. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2012;205:1-297. PubMed

5. Garcia S, Mintegi S, Gomez B, et al. Is 15 days an appropriate cut-off age for considering serious bacterial infection in the management of febrile infants? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):455-458. PubMed

6. Schwartz S, Raveh D, Toker O, Segal G, Godovitch N, Schlesinger Y. A week-by-week analysis of the low-risk criteria for serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(4):287-292. PubMed

7. Huppler AR, Eickhoff JC, Wald ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010;125(2):228-233. PubMed

8. Baskin MN. The prevalence of serious bacterial infections by age in febrile infants during the first 3 months of life. Pediatr Ann. 1993;22(8):462-466. PubMed

9. Nigrovic LE, Mahajan PV, Blumberg SM, et al. The Yale Observation Scale Score and the risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants. Pediatrics 2017;140(1):e20170695. PubMed

10. Bergman DA, Mayer ML, Pantell RH, Finch SA, Wasserman RC. Does clinical presentation explain practice variability in the treatment of febrile infants? Pediatrics 2006;117(3):787-795. PubMed

11. Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1437-1441. PubMed

12. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection--an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94(3):390-396. PubMed

13. Baskin MN, O’Rourke EJ, Fleisher GR. Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):22-27. PubMed

14. Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics 2001;108(2):311-316. PubMed

15. Pichichero ME, Todd JK. Detection of neonatal bacteremia. J Pediatr. 1979;94(6):958-960. PubMed

16. Hurst MK, Yoder BA. Detection of bacteremia in young infants: is 48 hours adequate? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(8):711-713. PubMed

17. Friedman J, Matlow A. Time to identification of positive bacterial cultures in infants under three months of age hospitalized to rule out sepsis. Paediatr Child Health 1999;4(5):331-334. PubMed

18. Kliegman R, Behrman RE, Nelson WE. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Edition 20 / ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

19. Fever in infants and children. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, 2016. (Accessed 27 Nov 2016, 2016, at https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/symptoms-in-infants-and-children/fever-in-infants-and-children.)

20. Polin RA, Committee on F, Newborn. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2012;129(5):1006-1015. PubMed

21. Byington CL, Reynolds CC, Korgenski K, et al. Costs and infant outcomes after implementation of a care process model for febrile infants. Pediatrics 2012;130(1):e16-e24. PubMed

22. DeAngelis C, Joffe A, Wilson M, Willis E. Iatrogenic risks and financial costs of hospitalizing febrile infants. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137(12):1146-1149. PubMed

23. Nizam M, Norzila MZ. Stress among parents with acutely ill children. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56(4):428-434. PubMed

24. Rowley AH, Wald ER. The incubation period necessary for detection of bacteremia in immunocompetent children with fever. Implications for the clinician. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986;25(10):485-489. PubMed

25. La Scolea LJ, Jr., Dryja D, Sullivan TD, Mosovich L, Ellerstein N, Neter E. Diagnosis of bacteremia in children by quantitative direct plating and a radiometric procedure. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13(3):478-482. PubMed

26. Evans RC, Fine BR. Time to detection of bacterial cultures in infants aged 0 to 90 days. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):97-102. PubMed

27. Herr SM, Wald ER, Pitetti RD, Choi SS. Enhanced urinalysis improves identification of febrile infants ages 60 days and younger at low risk for serious bacterial illness. Pediatrics 2001;108(4):866-871. PubMed

28. Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Macias CG, et al. Clinical prediction rule for identifying children with cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis at very low risk of bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2007;297(1):52-60. PubMed

29. Doby EH, Stockmann C, Korgenski EK, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in febrile infants 1-90 days with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(9):1024-1026. PubMed

30. Bhansali P, Wiedermann BL, Pastor W, McMillan J, Shah N. Management of hospitalized febrile neonates without CSF analysis: A study of US pediatric hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):528-533. PubMed

31. Kanegaye JT, Soliemanzadeh P, Bradley JS. Lumbar puncture in pediatric bacterial meningitis: defining the time interval for recovery of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens after parenteral antibiotic pretreatment. Pediatrics 2001;108(5):1169-1174. PubMed

32. Biondi EA, Mischler M, Jerardi KE, et al. Blood culture time to positivity in febrile infants with bacteremia. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):844-849. PubMed

33. Moher D HC, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A. Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Infants (0–3 Months). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 205. In: Center OE-bP, ed. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. PubMed

1. Kaplan RL, Harper MB, Baskin MN, Macone AB, Mandl KD. Time to detection of positive cultures in 28- to 90-day-old febrile infants. Pediatrics 2000;106(6):E74. PubMed

2. Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

3. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Williams DJ, et al. Association of clinical practice guidelines with emergency department management of febrile infants </=56 days of age. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358-365. PubMed

4. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2012;205:1-297. PubMed

5. Garcia S, Mintegi S, Gomez B, et al. Is 15 days an appropriate cut-off age for considering serious bacterial infection in the management of febrile infants? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(5):455-458. PubMed

6. Schwartz S, Raveh D, Toker O, Segal G, Godovitch N, Schlesinger Y. A week-by-week analysis of the low-risk criteria for serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(4):287-292. PubMed

7. Huppler AR, Eickhoff JC, Wald ER. Performance of low-risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics 2010;125(2):228-233. PubMed

8. Baskin MN. The prevalence of serious bacterial infections by age in febrile infants during the first 3 months of life. Pediatr Ann. 1993;22(8):462-466. PubMed

9. Nigrovic LE, Mahajan PV, Blumberg SM, et al. The Yale Observation Scale Score and the risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants. Pediatrics 2017;140(1):e20170695. PubMed

10. Bergman DA, Mayer ML, Pantell RH, Finch SA, Wasserman RC. Does clinical presentation explain practice variability in the treatment of febrile infants? Pediatrics 2006;117(3):787-795. PubMed

11. Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1437-1441. PubMed

12. Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection--an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics 1994;94(3):390-396. PubMed

13. Baskin MN, O’Rourke EJ, Fleisher GR. Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. J Pediatr. 1992;120(1):22-27. PubMed

14. Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics 2001;108(2):311-316. PubMed

15. Pichichero ME, Todd JK. Detection of neonatal bacteremia. J Pediatr. 1979;94(6):958-960. PubMed

16. Hurst MK, Yoder BA. Detection of bacteremia in young infants: is 48 hours adequate? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14(8):711-713. PubMed

17. Friedman J, Matlow A. Time to identification of positive bacterial cultures in infants under three months of age hospitalized to rule out sepsis. Paediatr Child Health 1999;4(5):331-334. PubMed

18. Kliegman R, Behrman RE, Nelson WE. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. Edition 20 / ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

19. Fever in infants and children. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp, 2016. (Accessed 27 Nov 2016, 2016, at https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/symptoms-in-infants-and-children/fever-in-infants-and-children.)

20. Polin RA, Committee on F, Newborn. Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics 2012;129(5):1006-1015. PubMed

21. Byington CL, Reynolds CC, Korgenski K, et al. Costs and infant outcomes after implementation of a care process model for febrile infants. Pediatrics 2012;130(1):e16-e24. PubMed

22. DeAngelis C, Joffe A, Wilson M, Willis E. Iatrogenic risks and financial costs of hospitalizing febrile infants. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137(12):1146-1149. PubMed

23. Nizam M, Norzila MZ. Stress among parents with acutely ill children. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56(4):428-434. PubMed

24. Rowley AH, Wald ER. The incubation period necessary for detection of bacteremia in immunocompetent children with fever. Implications for the clinician. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1986;25(10):485-489. PubMed

25. La Scolea LJ, Jr., Dryja D, Sullivan TD, Mosovich L, Ellerstein N, Neter E. Diagnosis of bacteremia in children by quantitative direct plating and a radiometric procedure. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;13(3):478-482. PubMed

26. Evans RC, Fine BR. Time to detection of bacterial cultures in infants aged 0 to 90 days. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(2):97-102. PubMed

27. Herr SM, Wald ER, Pitetti RD, Choi SS. Enhanced urinalysis improves identification of febrile infants ages 60 days and younger at low risk for serious bacterial illness. Pediatrics 2001;108(4):866-871. PubMed

28. Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Macias CG, et al. Clinical prediction rule for identifying children with cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis at very low risk of bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2007;297(1):52-60. PubMed

29. Doby EH, Stockmann C, Korgenski EK, Blaschke AJ, Byington CL. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in febrile infants 1-90 days with urinary tract infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32(9):1024-1026. PubMed

30. Bhansali P, Wiedermann BL, Pastor W, McMillan J, Shah N. Management of hospitalized febrile neonates without CSF analysis: A study of US pediatric hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):528-533. PubMed

31. Kanegaye JT, Soliemanzadeh P, Bradley JS. Lumbar puncture in pediatric bacterial meningitis: defining the time interval for recovery of cerebrospinal fluid pathogens after parenteral antibiotic pretreatment. Pediatrics 2001;108(5):1169-1174. PubMed

32. Biondi EA, Mischler M, Jerardi KE, et al. Blood culture time to positivity in febrile infants with bacteremia. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):844-849. PubMed

33. Moher D HC, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A. Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Infants (0–3 Months). Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 205. In: Center OE-bP, ed. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Visiting Professor in Hospital Medicine

Hospital medicine is an emerging specialty comprised predominantly of early‐career faculty, often less than 5 years postresidency and predominately at instructor or assistant professor level.[1] Effective mentoring has been identified as a critical component of academic success.[2, 3] Published data suggest that most academic hospitalists do not have a mentor, and when they do, the majority of them spend less than 4 hours per year with their mentor.[2] The reasons for this are multifactorial but largely result from the lack of structure, opportunities, and local senior academic hospitalists.[1, 4] Early‐career faculty have difficulty establishing external mentoring relationships, and new models beyond the traditional intrainstitutional dyad are needed.[3, 4] The need for mentors and structured mentorship networks may be particularly high in hospital medicine.[5]

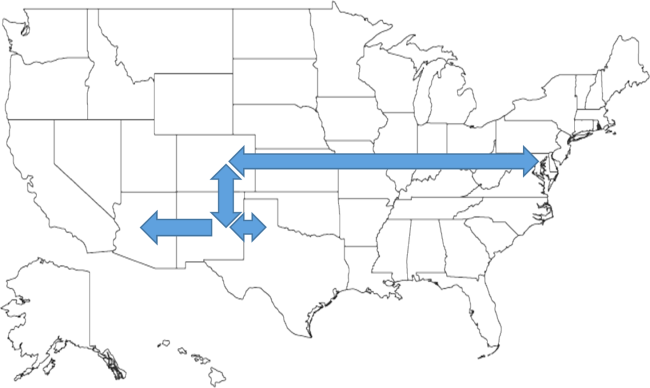

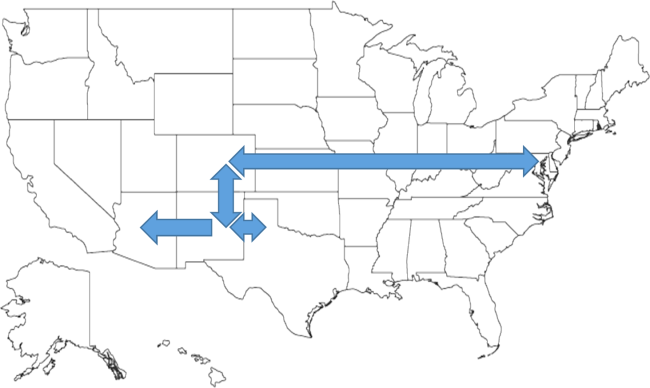

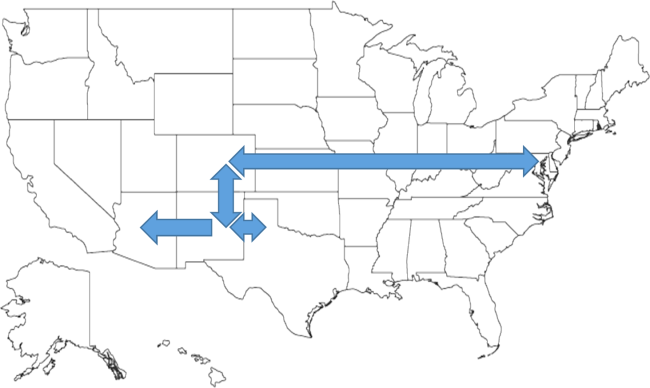

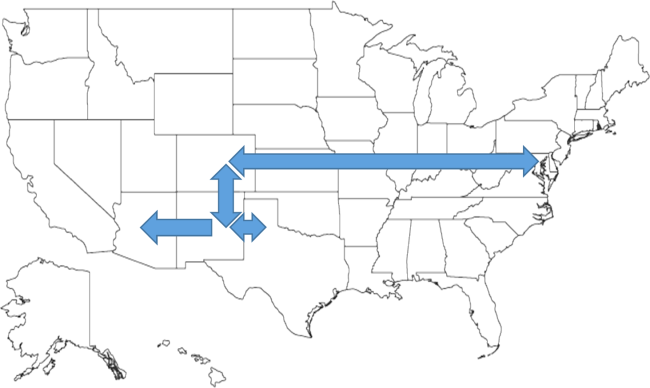

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was designed to promote cross‐institutional mentorship, share hospitalist innovations, and facilitate academic collaboration between hospitalist groups. We describe the design and early experience with this program across 5 academic hospital medicine programs.

PROGRAM DESIGN

Objectives

The program was designed to promote mentoring relationships between early‐career hospitalist faculty and a visiting professor from another academic hospital medicine group. The program sought to provide immediate career advice during the visits, but also create opportunities for long‐term mentorship and collaboration between institutions. Goals for each visiting professorship included: (1) follow‐up contact between early‐career faculty and visiting professor in the 6 months following the visit, (2) long‐term mentoring relationship with at least 1 early‐career faculty at the visited institution, and (3) identification of opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration to disseminate innovations.

Selection of Sites and Faculty

The first 2 academic medical centers (AMCs) for the visiting professorship exchange designed the program (University of Colorado and University of New Mexico). In subsequent years, each participating AMC was able to solicit additional sites for faculty exchange. This model can expand without requiring ongoing central direction. No criteria were set for selection of AMCs. Visiting professors in hospital medicine were explicitly targeted to be at midcareer stage of late assistant professor or early associate professor and within 1 to 2 years of promotion. It was felt that this group would gain the maximal career benefit from delivering an invited visit to an external AMC, yet have a sufficient track record to deliver effective mentoring advice to early‐career hospitalists. The hospitalist group sending the visiting professor would propose a few candidates, with the innovations they would be able to present, and the hosting site would select 1 for the visit. Early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were generally instructor to early assistant professors.

Visit Itinerary

The visit itinerary was set up as follows:

- Visiting professor delivers a formal 1‐hour presentation to hospitalist faculty, describing an innovation in clinical care, quality improvement, patient safety, or education.

- Individual meetings with 3 to 5 early‐career hospitalists to review faculty portfolios and provide career advice.

- Group lunch between the visiting professor and faculty with similar interests to promote cross‐institutional networking and spark potential collaborations.

- Meeting with hospital medicine program leadership.

- Visiting professor receives exposure to an innovation developed at the hosting institution.

- Dinner with the hosting faculty including the senior hospitalist coordinating the visit.

In advance of the visit, both early‐career faculty and visiting professors receive written materials describing the program, its objectives, and tips to prepare for the visit (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). The curricula vitae of early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were provided to the visiting professor. Visit costs were covered by the visiting professor's institution. Honoraria were not offered.

Program Evaluation

Within a month of each visit, a paper survey was administered to the visiting professor and the faculty with whom she/he met. In addition to demographic data including gender, self‐reported minority status, academic rank, years at rank, and total years in academic medicine, the survey asked faculty to rate on a 5‐point Likert scale their assessment of the usefulness of the visit to accomplish the 4 core goals of the program: (1) cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations in clinical medicine, education, or research; (2) advancing the respondent's academic career; (3) fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships; and (4) promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Free‐text responses for overall impression of program and suggestions for improvement were solicited.

At the time of this writing, 1 year has passed from the initial visits for the first 3 visiting professorships. A 1‐year follow‐up survey was administered assessing (1) total number of contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the visit, (2) whether a letter of recommendation resulted from the visit, (3) whether the respondent had seen evidence of spread of innovative ideas as a result of the program, (4) participation in a cross‐institutional collaboration as a result of the program, and (5) assessment of benefit in continuing the program in the next year. The respondents were also asked to rate the global utility of the program to their professional development on a 5‐point scale ranging from not at all useful to very useful (Thinking about what has happened to you since the visit a year ago, please rate the usefulness of the entire program to your professional life: overall usefulness for my professional development.). Domain‐specific utility in improving clinical, research, quality improvement, and administrative skills were also elicited (results not shown). Finally, suggestions to improve the program for the future were solicited. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the study of this faculty development program did not qualify as human subjects research, and subjects were therefore not asked to provide informed consent for participation.

RESULTS

To date, 5 academic medical centers have participated in the visiting professorship program, with 7 visiting professors interacting with 29 early‐career faculty. Of the 29 early‐career faculty, 72% (21/29) were at the rank of assistant professor, 17% (5/29) instructor, 7% (2/29) residents with plans to hire, and 3% (1/29) associate professor. The median was 2 years in academic medicine and 1 year at current academic rank. Forty‐one percent (12/29) were women and 7% (2/29) identified as ethnic minority. Of the 7 visiting professors, 57% (4/7) were assistant professor and 43% (3/7) were associate professors. The median was 5 years in academic medicine, 29% (2/7) were women, and none identified as ethnic minority.

Immediate postvisit survey response was obtained for all participating faculty. In the immediate postvisit survey, on a 5‐point Likert scale, the 29 early‐career faculty rated the visit: 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.2 for advancing my academic career, 4.2 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Ninety‐three percent (26/28 accounting for 1 nonresponse to this question) reported the visiting professorship had high potential to disseminate innovation (rated greater than 3 on the 5‐point Likert score). Eighty‐three percent (24/29) of the early‐career faculty rated the visit highly useful in advancing their career, 76% (22/29) responded that the visit was highly likely to foster external mentorship relationships, and 90% (26/29) reported the visit highly effective in promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. In the immediate postvisit survey, the 7 visiting professors rated the visit 4.9 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.3 for advancing my academic career, 4.0 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.3 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations.

Free‐text comments from both visiting professors and early‐career faculty were generally favorable (Table 1). Some comments offered constructive input on appropriate matching of faculty, previsit preparation, or desire for more time in sessions (Table 1).

| Visiting Professors (n = 7) | Early‐Career Faculty (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| I was very impressed with the degree of organization, preparation, and structure from [host institution]. The project is a great concept and may well lead to similar and even more developed ones in the future. It is very helpful to get the pulse on another program and to hear of some of the same struggles and successes of another hospitalist program. The potential for cross‐site mentor‐mentee relationships and collaborations is a win‐win for both programs. | I really enjoyed my individual meeting with [visiting professor]. She was helpful in reviewing current projects from another perspective and very helpful in making suggestions for future projects. Also enjoyed her Grand Rounds and plan to follow‐up on this issue for possible cross‐institutional collaboration. |

| Overall, this exchange is a great program. It is fun, promotes idea exchange, and is immensely helpful to the visiting professor for promotion. Every meeting I had with faculty at [host institution] was interesting and worthwhile. The primary challenge is maintaining mentorship ties and momentum after the visit. I personally e‐mailed every person I met and received many responses, including several explicit requests for ongoing advising and collaboration. | I think this is a great program. It definitely gives us the opportunity to meet people outside of the [host institution] community and foster relationships, mentorship, and possible collaborations with projects and programs. |

| I liked multidisciplinary rounding. Research club. Meeting with faculty and trying to find common areas of interest. | I think this is a fantastic program so far. [Visiting professor] was very energetic and interested in making the most of the day. She contacted me after the visit and offered to keep in touch in the future. Right now I can see the program as being most useful in establishing new mentor/mentee relationships. |

| Most of the faculty I met with see value in being involved in systems/quality improvement, but most do not express interest in specific projects. Areas needing improvement were identified by everyone I met with so developing projects around these areas should be doable. They might benefit from access to mentoring in quality improvement. | It was fantastic to meet with [visiting professor] and get a sense for his work and also brainstorm about how we might do similar work here in the future (eg, in high‐value care). It was also great to then see him 2 days later at [national conference]. I feel this is a great program to improve our connections cross‐institutionally and hopefully to spark some future collaborations. |

| Very worthwhile. Was really helpful to meet with various faculty and leadership to see similarities and differences between our institutions. Generated several ideas for collaborative activities already. Also really helpful to have a somewhat structured way to share my work at an outside institution, as well as to create opportunities for mentor‐mentee relationships outside my home institution. | Incredibly valuable to promote this kind of cross‐pollination for both collaboration and innovation. |

| Wonderful, inspiring, professionally advantageous. | |

| Good idea. Good way to help midcareer faculty with advancement. Offers promise for collaboration of research/workshops. | |

| Suggestions for Improvement | |

| Please have e‐mails of the folks we meet available immediately after the visit. It is hard to know if anyone felt enough of a connection to want mentorship from me. | I feel like I may be a bit early on to benefit as much as I could have. |

| Develop a mentorship program for quality improvement. As part of this exchange, consider treating visits as similar to a consultation. Have visitor with specific focus that they can offer help with. | Nice to have personal access to accomplished faculty from other institutions. Their perspective and career trajectory don't always align due to differences in institution culture, specifics of promotion process, and so on, but still a useful experience. |

| Share any possible more‐formal topics for discussion with leadership prior to the visit so can prepare ahead of time (eg, gather information they may have questions on). Otherwise it was great! | For early career faculty, more discussions prior in regard to what to expect. |

| A question is who should continue to push? Is it the prospective mentee, the mentee's institution, an so on? | Great idea. Would have loved to be involved in more aspects. More time for discussion would have been good. Did not get to discuss collaboration in person. |

| Great to get to talk to someone from totally different system. Wish we had more time to talk. | |

One‐year follow‐up was obtained for all but 1 early‐career faculty member receiving the follow‐up survey, and all 3 visiting professors. Of the 3 visiting professorships that occurred more than 1 year ago, 16 mentorship contacts occurred in total (phone, e‐mail, or in person) between 13 early‐career faculty and 3 visiting professors in the year after the initial visits (range, 04 contacts). Follow‐up contact occurred for 3 of 4 early‐career faculty from the first visiting professorship, 3 of 5 from the second visiting professorship, and 2 of 4 from the third visiting professorship. One early‐career faculty member from each host academic medical center had 3 or more additional contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the initial visit. Overall, 8/13 (62%) of early‐career faculty had at least 1 follow‐up mentoring discussion. On 1‐year follow‐up, overall utility for professional development was rated an average of 3.5 by early‐career faculty (with a trend of higher ratings of efficacy with increasing number of follow‐up contacts) and 4.7 by visiting professors. Half (8/16) of the involved faculty report having seen evidence of cross‐institutional dissemination of innovation. Ninety‐four percent (15/16) of participants at 1‐year follow‐up felt there was benefit to their institution in continuing the program for the next year.

Objective evidence of cross‐institutional scholarship, assessed by email query of both visiting professors and senior hospitalists coordinating the visits, includes 2 collaborative peer reviewed publications including mentors and mentees participating in the visiting professorship.[6, 7] Joint educational curriculum development on high‐value care between sites is planned. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has resulted in 1 external letter to support a visiting professor's promotion to date.

DISCUSSION

Hospital Medicine is a young, rapidly growing field, hence the number of experienced academic hospitalist mentors with expertise in successfully navigating an academic career is limited. A national study of hospitalist leaders found that 75% of clinician‐educators and 58% of research faculty feel that lack of mentorship is a major issue.[1] Mentorship for hospitalist clinician‐investigators is often delivered by nonhospitalists.[2, 8] There is little evidence of external mentorship for academic clinician‐educators in hospital medicine.[1] Without explicit programmatic support, many faculty may find this to be a barrier to career advancement. A study of successfully promoted hospitalists identified difficulty identifying external senior hospitalists to write letters in support of promotion as an obstacle.[9] Our study of the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program found that early‐career faculty rated the visit as useful in advancing their career and fostered external mentorship relationships. Subsequent experience suggests more than half of the early‐career faculty will maintain contact with the visiting professor over the year following the visit. Visiting professors rate the experience particularly highly in their own career advancement.

The hospitalist movement is built on a foundation of innovation. The focus of each presentation was on an innovation developed by the visiting professor, and each visit showcased an innovation of the visited institution. This is distinct from traditional Hospital Grand Rounds, which more often focus on basic science research or clinical pathophysiology/disease management based on subspecialty topics.[10] The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was judged by participants to be an effective means of spreading innovation.

Insights from experience with the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program include the importance of preliminary work prior to each visit. Program directors need to attend closely to the fit between the interests and career path of the visiting professor and those of the early‐career faculty. The innovations being shared should be aligned with organizational interests to maximize the chance of subsequent spread of the innovation and future collaboration. Providing faculty information about the objectives of the program in advance of the visit and arranging an exchange of curricula vitae between the early‐career faculty and the visiting professor allows participants to prepare for the in‐person coaching. Based on comments from participants, prompting contact from the visiting professor after the visit may be helpful to initiate the longitudinal relationship. We also found that early‐career faculty may not be aware of how to effectively use a mentoring relationship with an external faculty member. Training sessions for both mentors and mentees on effective mentorship relationships before visiting professorships might improve early‐career faculty confidence in initiating relationships and maximize value from mentor coaching.

A key issue is finding the right level of career maturity for the visiting professor. Our approach in selecting visiting professors was congruent with utilization of midcareer peer coaches employed by intrainstitutional hospital medicine mentoring programs.[11] The visiting professor should have sufficient experience and accomplishments to be able to effectively counsel junior faculty. However, it is important that the visiting professor also has sufficient time and interest to take on additional mentees and to be a full participant in shared scholarship projects emerging from the experience.

This study represents the experience of 5 mature academic hospitalist groups, and results may not be generalizable to dissimilar institutions or if only the most senior faculty are selected to perform visits. There is an inherent selection bias in the choice of both visiting professor and early‐career faculty. The small sample size of the faculty exposed to this program is a limitation to generalizability of the results of this evaluation. Whether this program will result in greater success in promotion of academic hospitalists cannot be assessed based on the follow‐up available. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has continued to be sustained with an additional academic medical center enrolled and 2 additional site visits planned. The costs of the program are low, largely air travel and a night of lodging, as well as nominal administrative logistical support. Perceived benefits by participants and academic medical centers make this modest investment worth considering for academic hospitalist groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program offers structure, opportunities, and access to senior mentors to advance the development of early‐career hospitalists while spreading innovation to distant sites. It is assessed by participants to facilitate external mentoring relationships and has the potential to advance the careers of both early‐career faculty as well as the visiting professors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5–9.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , . Mentoring faculty in academic medicine: a new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870.

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:240–246.

- , . The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1–2.

- , , , . Procedural skills for hospitalists. Hosp Med Clin. 2016;5:114–136.

- , , . Cedecea davisae' s role in a polymicrobial lung infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Case reports in infectious diseases. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:176864.

- , , , . Innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314–318.

- , , , , . Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:411–415.

- , , , , . A case study of medical grand rounds: are we using effective methods? Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1144–1151.

- , , , . Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161–166.

Hospital medicine is an emerging specialty comprised predominantly of early‐career faculty, often less than 5 years postresidency and predominately at instructor or assistant professor level.[1] Effective mentoring has been identified as a critical component of academic success.[2, 3] Published data suggest that most academic hospitalists do not have a mentor, and when they do, the majority of them spend less than 4 hours per year with their mentor.[2] The reasons for this are multifactorial but largely result from the lack of structure, opportunities, and local senior academic hospitalists.[1, 4] Early‐career faculty have difficulty establishing external mentoring relationships, and new models beyond the traditional intrainstitutional dyad are needed.[3, 4] The need for mentors and structured mentorship networks may be particularly high in hospital medicine.[5]

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was designed to promote cross‐institutional mentorship, share hospitalist innovations, and facilitate academic collaboration between hospitalist groups. We describe the design and early experience with this program across 5 academic hospital medicine programs.

PROGRAM DESIGN

Objectives

The program was designed to promote mentoring relationships between early‐career hospitalist faculty and a visiting professor from another academic hospital medicine group. The program sought to provide immediate career advice during the visits, but also create opportunities for long‐term mentorship and collaboration between institutions. Goals for each visiting professorship included: (1) follow‐up contact between early‐career faculty and visiting professor in the 6 months following the visit, (2) long‐term mentoring relationship with at least 1 early‐career faculty at the visited institution, and (3) identification of opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration to disseminate innovations.

Selection of Sites and Faculty

The first 2 academic medical centers (AMCs) for the visiting professorship exchange designed the program (University of Colorado and University of New Mexico). In subsequent years, each participating AMC was able to solicit additional sites for faculty exchange. This model can expand without requiring ongoing central direction. No criteria were set for selection of AMCs. Visiting professors in hospital medicine were explicitly targeted to be at midcareer stage of late assistant professor or early associate professor and within 1 to 2 years of promotion. It was felt that this group would gain the maximal career benefit from delivering an invited visit to an external AMC, yet have a sufficient track record to deliver effective mentoring advice to early‐career hospitalists. The hospitalist group sending the visiting professor would propose a few candidates, with the innovations they would be able to present, and the hosting site would select 1 for the visit. Early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were generally instructor to early assistant professors.

Visit Itinerary

The visit itinerary was set up as follows:

- Visiting professor delivers a formal 1‐hour presentation to hospitalist faculty, describing an innovation in clinical care, quality improvement, patient safety, or education.

- Individual meetings with 3 to 5 early‐career hospitalists to review faculty portfolios and provide career advice.

- Group lunch between the visiting professor and faculty with similar interests to promote cross‐institutional networking and spark potential collaborations.

- Meeting with hospital medicine program leadership.

- Visiting professor receives exposure to an innovation developed at the hosting institution.

- Dinner with the hosting faculty including the senior hospitalist coordinating the visit.

In advance of the visit, both early‐career faculty and visiting professors receive written materials describing the program, its objectives, and tips to prepare for the visit (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). The curricula vitae of early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were provided to the visiting professor. Visit costs were covered by the visiting professor's institution. Honoraria were not offered.

Program Evaluation

Within a month of each visit, a paper survey was administered to the visiting professor and the faculty with whom she/he met. In addition to demographic data including gender, self‐reported minority status, academic rank, years at rank, and total years in academic medicine, the survey asked faculty to rate on a 5‐point Likert scale their assessment of the usefulness of the visit to accomplish the 4 core goals of the program: (1) cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations in clinical medicine, education, or research; (2) advancing the respondent's academic career; (3) fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships; and (4) promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Free‐text responses for overall impression of program and suggestions for improvement were solicited.

At the time of this writing, 1 year has passed from the initial visits for the first 3 visiting professorships. A 1‐year follow‐up survey was administered assessing (1) total number of contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the visit, (2) whether a letter of recommendation resulted from the visit, (3) whether the respondent had seen evidence of spread of innovative ideas as a result of the program, (4) participation in a cross‐institutional collaboration as a result of the program, and (5) assessment of benefit in continuing the program in the next year. The respondents were also asked to rate the global utility of the program to their professional development on a 5‐point scale ranging from not at all useful to very useful (Thinking about what has happened to you since the visit a year ago, please rate the usefulness of the entire program to your professional life: overall usefulness for my professional development.). Domain‐specific utility in improving clinical, research, quality improvement, and administrative skills were also elicited (results not shown). Finally, suggestions to improve the program for the future were solicited. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the study of this faculty development program did not qualify as human subjects research, and subjects were therefore not asked to provide informed consent for participation.

RESULTS

To date, 5 academic medical centers have participated in the visiting professorship program, with 7 visiting professors interacting with 29 early‐career faculty. Of the 29 early‐career faculty, 72% (21/29) were at the rank of assistant professor, 17% (5/29) instructor, 7% (2/29) residents with plans to hire, and 3% (1/29) associate professor. The median was 2 years in academic medicine and 1 year at current academic rank. Forty‐one percent (12/29) were women and 7% (2/29) identified as ethnic minority. Of the 7 visiting professors, 57% (4/7) were assistant professor and 43% (3/7) were associate professors. The median was 5 years in academic medicine, 29% (2/7) were women, and none identified as ethnic minority.

Immediate postvisit survey response was obtained for all participating faculty. In the immediate postvisit survey, on a 5‐point Likert scale, the 29 early‐career faculty rated the visit: 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.2 for advancing my academic career, 4.2 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Ninety‐three percent (26/28 accounting for 1 nonresponse to this question) reported the visiting professorship had high potential to disseminate innovation (rated greater than 3 on the 5‐point Likert score). Eighty‐three percent (24/29) of the early‐career faculty rated the visit highly useful in advancing their career, 76% (22/29) responded that the visit was highly likely to foster external mentorship relationships, and 90% (26/29) reported the visit highly effective in promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. In the immediate postvisit survey, the 7 visiting professors rated the visit 4.9 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.3 for advancing my academic career, 4.0 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.3 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations.

Free‐text comments from both visiting professors and early‐career faculty were generally favorable (Table 1). Some comments offered constructive input on appropriate matching of faculty, previsit preparation, or desire for more time in sessions (Table 1).

| Visiting Professors (n = 7) | Early‐Career Faculty (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| I was very impressed with the degree of organization, preparation, and structure from [host institution]. The project is a great concept and may well lead to similar and even more developed ones in the future. It is very helpful to get the pulse on another program and to hear of some of the same struggles and successes of another hospitalist program. The potential for cross‐site mentor‐mentee relationships and collaborations is a win‐win for both programs. | I really enjoyed my individual meeting with [visiting professor]. She was helpful in reviewing current projects from another perspective and very helpful in making suggestions for future projects. Also enjoyed her Grand Rounds and plan to follow‐up on this issue for possible cross‐institutional collaboration. |