User login

Visiting Professor in Hospital Medicine

Hospital medicine is an emerging specialty comprised predominantly of early‐career faculty, often less than 5 years postresidency and predominately at instructor or assistant professor level.[1] Effective mentoring has been identified as a critical component of academic success.[2, 3] Published data suggest that most academic hospitalists do not have a mentor, and when they do, the majority of them spend less than 4 hours per year with their mentor.[2] The reasons for this are multifactorial but largely result from the lack of structure, opportunities, and local senior academic hospitalists.[1, 4] Early‐career faculty have difficulty establishing external mentoring relationships, and new models beyond the traditional intrainstitutional dyad are needed.[3, 4] The need for mentors and structured mentorship networks may be particularly high in hospital medicine.[5]

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was designed to promote cross‐institutional mentorship, share hospitalist innovations, and facilitate academic collaboration between hospitalist groups. We describe the design and early experience with this program across 5 academic hospital medicine programs.

PROGRAM DESIGN

Objectives

The program was designed to promote mentoring relationships between early‐career hospitalist faculty and a visiting professor from another academic hospital medicine group. The program sought to provide immediate career advice during the visits, but also create opportunities for long‐term mentorship and collaboration between institutions. Goals for each visiting professorship included: (1) follow‐up contact between early‐career faculty and visiting professor in the 6 months following the visit, (2) long‐term mentoring relationship with at least 1 early‐career faculty at the visited institution, and (3) identification of opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration to disseminate innovations.

Selection of Sites and Faculty

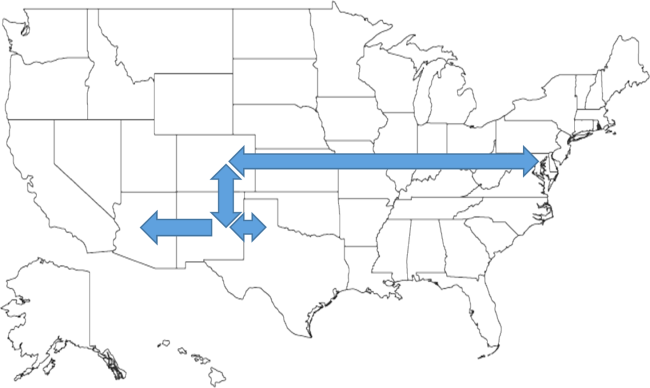

The first 2 academic medical centers (AMCs) for the visiting professorship exchange designed the program (University of Colorado and University of New Mexico). In subsequent years, each participating AMC was able to solicit additional sites for faculty exchange. This model can expand without requiring ongoing central direction. No criteria were set for selection of AMCs. Visiting professors in hospital medicine were explicitly targeted to be at midcareer stage of late assistant professor or early associate professor and within 1 to 2 years of promotion. It was felt that this group would gain the maximal career benefit from delivering an invited visit to an external AMC, yet have a sufficient track record to deliver effective mentoring advice to early‐career hospitalists. The hospitalist group sending the visiting professor would propose a few candidates, with the innovations they would be able to present, and the hosting site would select 1 for the visit. Early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were generally instructor to early assistant professors.

Visit Itinerary

The visit itinerary was set up as follows:

- Visiting professor delivers a formal 1‐hour presentation to hospitalist faculty, describing an innovation in clinical care, quality improvement, patient safety, or education.

- Individual meetings with 3 to 5 early‐career hospitalists to review faculty portfolios and provide career advice.

- Group lunch between the visiting professor and faculty with similar interests to promote cross‐institutional networking and spark potential collaborations.

- Meeting with hospital medicine program leadership.

- Visiting professor receives exposure to an innovation developed at the hosting institution.

- Dinner with the hosting faculty including the senior hospitalist coordinating the visit.

In advance of the visit, both early‐career faculty and visiting professors receive written materials describing the program, its objectives, and tips to prepare for the visit (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). The curricula vitae of early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were provided to the visiting professor. Visit costs were covered by the visiting professor's institution. Honoraria were not offered.

Program Evaluation

Within a month of each visit, a paper survey was administered to the visiting professor and the faculty with whom she/he met. In addition to demographic data including gender, self‐reported minority status, academic rank, years at rank, and total years in academic medicine, the survey asked faculty to rate on a 5‐point Likert scale their assessment of the usefulness of the visit to accomplish the 4 core goals of the program: (1) cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations in clinical medicine, education, or research; (2) advancing the respondent's academic career; (3) fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships; and (4) promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Free‐text responses for overall impression of program and suggestions for improvement were solicited.

At the time of this writing, 1 year has passed from the initial visits for the first 3 visiting professorships. A 1‐year follow‐up survey was administered assessing (1) total number of contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the visit, (2) whether a letter of recommendation resulted from the visit, (3) whether the respondent had seen evidence of spread of innovative ideas as a result of the program, (4) participation in a cross‐institutional collaboration as a result of the program, and (5) assessment of benefit in continuing the program in the next year. The respondents were also asked to rate the global utility of the program to their professional development on a 5‐point scale ranging from not at all useful to very useful (Thinking about what has happened to you since the visit a year ago, please rate the usefulness of the entire program to your professional life: overall usefulness for my professional development.). Domain‐specific utility in improving clinical, research, quality improvement, and administrative skills were also elicited (results not shown). Finally, suggestions to improve the program for the future were solicited. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the study of this faculty development program did not qualify as human subjects research, and subjects were therefore not asked to provide informed consent for participation.

RESULTS

To date, 5 academic medical centers have participated in the visiting professorship program, with 7 visiting professors interacting with 29 early‐career faculty. Of the 29 early‐career faculty, 72% (21/29) were at the rank of assistant professor, 17% (5/29) instructor, 7% (2/29) residents with plans to hire, and 3% (1/29) associate professor. The median was 2 years in academic medicine and 1 year at current academic rank. Forty‐one percent (12/29) were women and 7% (2/29) identified as ethnic minority. Of the 7 visiting professors, 57% (4/7) were assistant professor and 43% (3/7) were associate professors. The median was 5 years in academic medicine, 29% (2/7) were women, and none identified as ethnic minority.

Immediate postvisit survey response was obtained for all participating faculty. In the immediate postvisit survey, on a 5‐point Likert scale, the 29 early‐career faculty rated the visit: 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.2 for advancing my academic career, 4.2 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Ninety‐three percent (26/28 accounting for 1 nonresponse to this question) reported the visiting professorship had high potential to disseminate innovation (rated greater than 3 on the 5‐point Likert score). Eighty‐three percent (24/29) of the early‐career faculty rated the visit highly useful in advancing their career, 76% (22/29) responded that the visit was highly likely to foster external mentorship relationships, and 90% (26/29) reported the visit highly effective in promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. In the immediate postvisit survey, the 7 visiting professors rated the visit 4.9 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.3 for advancing my academic career, 4.0 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.3 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations.

Free‐text comments from both visiting professors and early‐career faculty were generally favorable (Table 1). Some comments offered constructive input on appropriate matching of faculty, previsit preparation, or desire for more time in sessions (Table 1).

| Visiting Professors (n = 7) | Early‐Career Faculty (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| I was very impressed with the degree of organization, preparation, and structure from [host institution]. The project is a great concept and may well lead to similar and even more developed ones in the future. It is very helpful to get the pulse on another program and to hear of some of the same struggles and successes of another hospitalist program. The potential for cross‐site mentor‐mentee relationships and collaborations is a win‐win for both programs. | I really enjoyed my individual meeting with [visiting professor]. She was helpful in reviewing current projects from another perspective and very helpful in making suggestions for future projects. Also enjoyed her Grand Rounds and plan to follow‐up on this issue for possible cross‐institutional collaboration. |

| Overall, this exchange is a great program. It is fun, promotes idea exchange, and is immensely helpful to the visiting professor for promotion. Every meeting I had with faculty at [host institution] was interesting and worthwhile. The primary challenge is maintaining mentorship ties and momentum after the visit. I personally e‐mailed every person I met and received many responses, including several explicit requests for ongoing advising and collaboration. | I think this is a great program. It definitely gives us the opportunity to meet people outside of the [host institution] community and foster relationships, mentorship, and possible collaborations with projects and programs. |

| I liked multidisciplinary rounding. Research club. Meeting with faculty and trying to find common areas of interest. | I think this is a fantastic program so far. [Visiting professor] was very energetic and interested in making the most of the day. She contacted me after the visit and offered to keep in touch in the future. Right now I can see the program as being most useful in establishing new mentor/mentee relationships. |

| Most of the faculty I met with see value in being involved in systems/quality improvement, but most do not express interest in specific projects. Areas needing improvement were identified by everyone I met with so developing projects around these areas should be doable. They might benefit from access to mentoring in quality improvement. | It was fantastic to meet with [visiting professor] and get a sense for his work and also brainstorm about how we might do similar work here in the future (eg, in high‐value care). It was also great to then see him 2 days later at [national conference]. I feel this is a great program to improve our connections cross‐institutionally and hopefully to spark some future collaborations. |

| Very worthwhile. Was really helpful to meet with various faculty and leadership to see similarities and differences between our institutions. Generated several ideas for collaborative activities already. Also really helpful to have a somewhat structured way to share my work at an outside institution, as well as to create opportunities for mentor‐mentee relationships outside my home institution. | Incredibly valuable to promote this kind of cross‐pollination for both collaboration and innovation. |

| Wonderful, inspiring, professionally advantageous. | |

| Good idea. Good way to help midcareer faculty with advancement. Offers promise for collaboration of research/workshops. | |

| Suggestions for Improvement | |

| Please have e‐mails of the folks we meet available immediately after the visit. It is hard to know if anyone felt enough of a connection to want mentorship from me. | I feel like I may be a bit early on to benefit as much as I could have. |

| Develop a mentorship program for quality improvement. As part of this exchange, consider treating visits as similar to a consultation. Have visitor with specific focus that they can offer help with. | Nice to have personal access to accomplished faculty from other institutions. Their perspective and career trajectory don't always align due to differences in institution culture, specifics of promotion process, and so on, but still a useful experience. |

| Share any possible more‐formal topics for discussion with leadership prior to the visit so can prepare ahead of time (eg, gather information they may have questions on). Otherwise it was great! | For early career faculty, more discussions prior in regard to what to expect. |

| A question is who should continue to push? Is it the prospective mentee, the mentee's institution, an so on? | Great idea. Would have loved to be involved in more aspects. More time for discussion would have been good. Did not get to discuss collaboration in person. |

| Great to get to talk to someone from totally different system. Wish we had more time to talk. | |

One‐year follow‐up was obtained for all but 1 early‐career faculty member receiving the follow‐up survey, and all 3 visiting professors. Of the 3 visiting professorships that occurred more than 1 year ago, 16 mentorship contacts occurred in total (phone, e‐mail, or in person) between 13 early‐career faculty and 3 visiting professors in the year after the initial visits (range, 04 contacts). Follow‐up contact occurred for 3 of 4 early‐career faculty from the first visiting professorship, 3 of 5 from the second visiting professorship, and 2 of 4 from the third visiting professorship. One early‐career faculty member from each host academic medical center had 3 or more additional contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the initial visit. Overall, 8/13 (62%) of early‐career faculty had at least 1 follow‐up mentoring discussion. On 1‐year follow‐up, overall utility for professional development was rated an average of 3.5 by early‐career faculty (with a trend of higher ratings of efficacy with increasing number of follow‐up contacts) and 4.7 by visiting professors. Half (8/16) of the involved faculty report having seen evidence of cross‐institutional dissemination of innovation. Ninety‐four percent (15/16) of participants at 1‐year follow‐up felt there was benefit to their institution in continuing the program for the next year.

Objective evidence of cross‐institutional scholarship, assessed by email query of both visiting professors and senior hospitalists coordinating the visits, includes 2 collaborative peer reviewed publications including mentors and mentees participating in the visiting professorship.[6, 7] Joint educational curriculum development on high‐value care between sites is planned. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has resulted in 1 external letter to support a visiting professor's promotion to date.

DISCUSSION

Hospital Medicine is a young, rapidly growing field, hence the number of experienced academic hospitalist mentors with expertise in successfully navigating an academic career is limited. A national study of hospitalist leaders found that 75% of clinician‐educators and 58% of research faculty feel that lack of mentorship is a major issue.[1] Mentorship for hospitalist clinician‐investigators is often delivered by nonhospitalists.[2, 8] There is little evidence of external mentorship for academic clinician‐educators in hospital medicine.[1] Without explicit programmatic support, many faculty may find this to be a barrier to career advancement. A study of successfully promoted hospitalists identified difficulty identifying external senior hospitalists to write letters in support of promotion as an obstacle.[9] Our study of the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program found that early‐career faculty rated the visit as useful in advancing their career and fostered external mentorship relationships. Subsequent experience suggests more than half of the early‐career faculty will maintain contact with the visiting professor over the year following the visit. Visiting professors rate the experience particularly highly in their own career advancement.

The hospitalist movement is built on a foundation of innovation. The focus of each presentation was on an innovation developed by the visiting professor, and each visit showcased an innovation of the visited institution. This is distinct from traditional Hospital Grand Rounds, which more often focus on basic science research or clinical pathophysiology/disease management based on subspecialty topics.[10] The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was judged by participants to be an effective means of spreading innovation.

Insights from experience with the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program include the importance of preliminary work prior to each visit. Program directors need to attend closely to the fit between the interests and career path of the visiting professor and those of the early‐career faculty. The innovations being shared should be aligned with organizational interests to maximize the chance of subsequent spread of the innovation and future collaboration. Providing faculty information about the objectives of the program in advance of the visit and arranging an exchange of curricula vitae between the early‐career faculty and the visiting professor allows participants to prepare for the in‐person coaching. Based on comments from participants, prompting contact from the visiting professor after the visit may be helpful to initiate the longitudinal relationship. We also found that early‐career faculty may not be aware of how to effectively use a mentoring relationship with an external faculty member. Training sessions for both mentors and mentees on effective mentorship relationships before visiting professorships might improve early‐career faculty confidence in initiating relationships and maximize value from mentor coaching.

A key issue is finding the right level of career maturity for the visiting professor. Our approach in selecting visiting professors was congruent with utilization of midcareer peer coaches employed by intrainstitutional hospital medicine mentoring programs.[11] The visiting professor should have sufficient experience and accomplishments to be able to effectively counsel junior faculty. However, it is important that the visiting professor also has sufficient time and interest to take on additional mentees and to be a full participant in shared scholarship projects emerging from the experience.

This study represents the experience of 5 mature academic hospitalist groups, and results may not be generalizable to dissimilar institutions or if only the most senior faculty are selected to perform visits. There is an inherent selection bias in the choice of both visiting professor and early‐career faculty. The small sample size of the faculty exposed to this program is a limitation to generalizability of the results of this evaluation. Whether this program will result in greater success in promotion of academic hospitalists cannot be assessed based on the follow‐up available. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has continued to be sustained with an additional academic medical center enrolled and 2 additional site visits planned. The costs of the program are low, largely air travel and a night of lodging, as well as nominal administrative logistical support. Perceived benefits by participants and academic medical centers make this modest investment worth considering for academic hospitalist groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program offers structure, opportunities, and access to senior mentors to advance the development of early‐career hospitalists while spreading innovation to distant sites. It is assessed by participants to facilitate external mentoring relationships and has the potential to advance the careers of both early‐career faculty as well as the visiting professors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5–9.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , . Mentoring faculty in academic medicine: a new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870.

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:240–246.

- , . The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1–2.

- , , , . Procedural skills for hospitalists. Hosp Med Clin. 2016;5:114–136.

- , , . Cedecea davisae' s role in a polymicrobial lung infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Case reports in infectious diseases. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:176864.

- , , , . Innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314–318.

- , , , , . Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:411–415.

- , , , , . A case study of medical grand rounds: are we using effective methods? Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1144–1151.

- , , , . Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161–166.

Hospital medicine is an emerging specialty comprised predominantly of early‐career faculty, often less than 5 years postresidency and predominately at instructor or assistant professor level.[1] Effective mentoring has been identified as a critical component of academic success.[2, 3] Published data suggest that most academic hospitalists do not have a mentor, and when they do, the majority of them spend less than 4 hours per year with their mentor.[2] The reasons for this are multifactorial but largely result from the lack of structure, opportunities, and local senior academic hospitalists.[1, 4] Early‐career faculty have difficulty establishing external mentoring relationships, and new models beyond the traditional intrainstitutional dyad are needed.[3, 4] The need for mentors and structured mentorship networks may be particularly high in hospital medicine.[5]

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was designed to promote cross‐institutional mentorship, share hospitalist innovations, and facilitate academic collaboration between hospitalist groups. We describe the design and early experience with this program across 5 academic hospital medicine programs.

PROGRAM DESIGN

Objectives

The program was designed to promote mentoring relationships between early‐career hospitalist faculty and a visiting professor from another academic hospital medicine group. The program sought to provide immediate career advice during the visits, but also create opportunities for long‐term mentorship and collaboration between institutions. Goals for each visiting professorship included: (1) follow‐up contact between early‐career faculty and visiting professor in the 6 months following the visit, (2) long‐term mentoring relationship with at least 1 early‐career faculty at the visited institution, and (3) identification of opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration to disseminate innovations.

Selection of Sites and Faculty

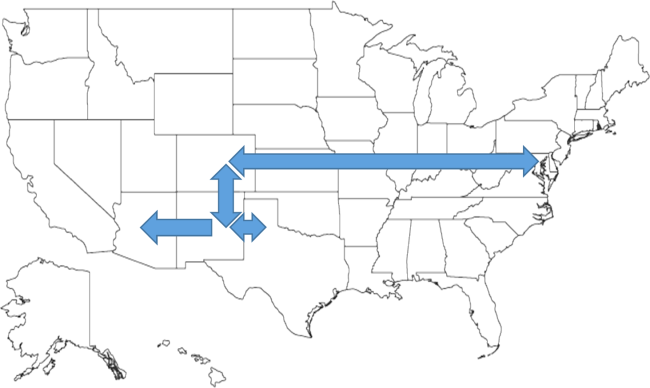

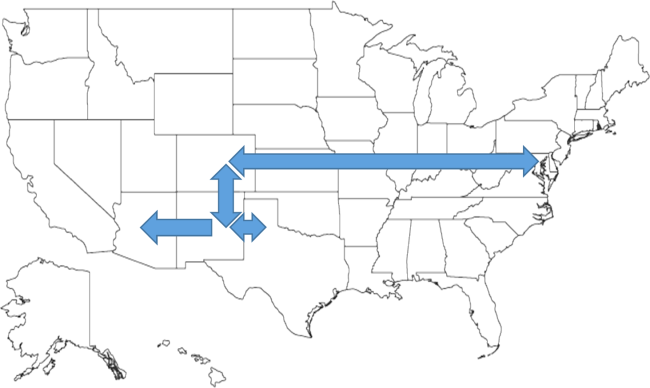

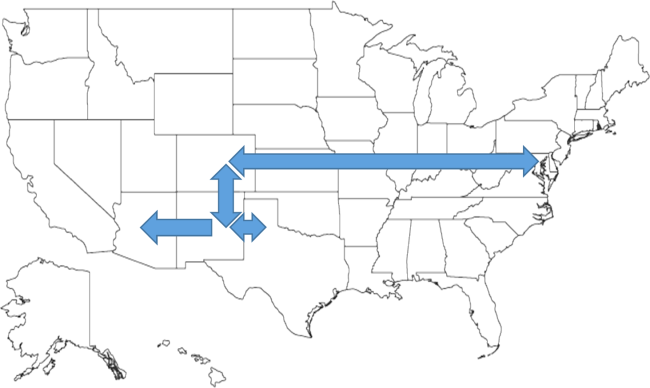

The first 2 academic medical centers (AMCs) for the visiting professorship exchange designed the program (University of Colorado and University of New Mexico). In subsequent years, each participating AMC was able to solicit additional sites for faculty exchange. This model can expand without requiring ongoing central direction. No criteria were set for selection of AMCs. Visiting professors in hospital medicine were explicitly targeted to be at midcareer stage of late assistant professor or early associate professor and within 1 to 2 years of promotion. It was felt that this group would gain the maximal career benefit from delivering an invited visit to an external AMC, yet have a sufficient track record to deliver effective mentoring advice to early‐career hospitalists. The hospitalist group sending the visiting professor would propose a few candidates, with the innovations they would be able to present, and the hosting site would select 1 for the visit. Early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were generally instructor to early assistant professors.

Visit Itinerary

The visit itinerary was set up as follows:

- Visiting professor delivers a formal 1‐hour presentation to hospitalist faculty, describing an innovation in clinical care, quality improvement, patient safety, or education.

- Individual meetings with 3 to 5 early‐career hospitalists to review faculty portfolios and provide career advice.

- Group lunch between the visiting professor and faculty with similar interests to promote cross‐institutional networking and spark potential collaborations.

- Meeting with hospital medicine program leadership.

- Visiting professor receives exposure to an innovation developed at the hosting institution.

- Dinner with the hosting faculty including the senior hospitalist coordinating the visit.

In advance of the visit, both early‐career faculty and visiting professors receive written materials describing the program, its objectives, and tips to prepare for the visit (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). The curricula vitae of early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were provided to the visiting professor. Visit costs were covered by the visiting professor's institution. Honoraria were not offered.

Program Evaluation

Within a month of each visit, a paper survey was administered to the visiting professor and the faculty with whom she/he met. In addition to demographic data including gender, self‐reported minority status, academic rank, years at rank, and total years in academic medicine, the survey asked faculty to rate on a 5‐point Likert scale their assessment of the usefulness of the visit to accomplish the 4 core goals of the program: (1) cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations in clinical medicine, education, or research; (2) advancing the respondent's academic career; (3) fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships; and (4) promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Free‐text responses for overall impression of program and suggestions for improvement were solicited.

At the time of this writing, 1 year has passed from the initial visits for the first 3 visiting professorships. A 1‐year follow‐up survey was administered assessing (1) total number of contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the visit, (2) whether a letter of recommendation resulted from the visit, (3) whether the respondent had seen evidence of spread of innovative ideas as a result of the program, (4) participation in a cross‐institutional collaboration as a result of the program, and (5) assessment of benefit in continuing the program in the next year. The respondents were also asked to rate the global utility of the program to their professional development on a 5‐point scale ranging from not at all useful to very useful (Thinking about what has happened to you since the visit a year ago, please rate the usefulness of the entire program to your professional life: overall usefulness for my professional development.). Domain‐specific utility in improving clinical, research, quality improvement, and administrative skills were also elicited (results not shown). Finally, suggestions to improve the program for the future were solicited. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the study of this faculty development program did not qualify as human subjects research, and subjects were therefore not asked to provide informed consent for participation.

RESULTS

To date, 5 academic medical centers have participated in the visiting professorship program, with 7 visiting professors interacting with 29 early‐career faculty. Of the 29 early‐career faculty, 72% (21/29) were at the rank of assistant professor, 17% (5/29) instructor, 7% (2/29) residents with plans to hire, and 3% (1/29) associate professor. The median was 2 years in academic medicine and 1 year at current academic rank. Forty‐one percent (12/29) were women and 7% (2/29) identified as ethnic minority. Of the 7 visiting professors, 57% (4/7) were assistant professor and 43% (3/7) were associate professors. The median was 5 years in academic medicine, 29% (2/7) were women, and none identified as ethnic minority.

Immediate postvisit survey response was obtained for all participating faculty. In the immediate postvisit survey, on a 5‐point Likert scale, the 29 early‐career faculty rated the visit: 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.2 for advancing my academic career, 4.2 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Ninety‐three percent (26/28 accounting for 1 nonresponse to this question) reported the visiting professorship had high potential to disseminate innovation (rated greater than 3 on the 5‐point Likert score). Eighty‐three percent (24/29) of the early‐career faculty rated the visit highly useful in advancing their career, 76% (22/29) responded that the visit was highly likely to foster external mentorship relationships, and 90% (26/29) reported the visit highly effective in promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. In the immediate postvisit survey, the 7 visiting professors rated the visit 4.9 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.3 for advancing my academic career, 4.0 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.3 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations.

Free‐text comments from both visiting professors and early‐career faculty were generally favorable (Table 1). Some comments offered constructive input on appropriate matching of faculty, previsit preparation, or desire for more time in sessions (Table 1).

| Visiting Professors (n = 7) | Early‐Career Faculty (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| I was very impressed with the degree of organization, preparation, and structure from [host institution]. The project is a great concept and may well lead to similar and even more developed ones in the future. It is very helpful to get the pulse on another program and to hear of some of the same struggles and successes of another hospitalist program. The potential for cross‐site mentor‐mentee relationships and collaborations is a win‐win for both programs. | I really enjoyed my individual meeting with [visiting professor]. She was helpful in reviewing current projects from another perspective and very helpful in making suggestions for future projects. Also enjoyed her Grand Rounds and plan to follow‐up on this issue for possible cross‐institutional collaboration. |

| Overall, this exchange is a great program. It is fun, promotes idea exchange, and is immensely helpful to the visiting professor for promotion. Every meeting I had with faculty at [host institution] was interesting and worthwhile. The primary challenge is maintaining mentorship ties and momentum after the visit. I personally e‐mailed every person I met and received many responses, including several explicit requests for ongoing advising and collaboration. | I think this is a great program. It definitely gives us the opportunity to meet people outside of the [host institution] community and foster relationships, mentorship, and possible collaborations with projects and programs. |

| I liked multidisciplinary rounding. Research club. Meeting with faculty and trying to find common areas of interest. | I think this is a fantastic program so far. [Visiting professor] was very energetic and interested in making the most of the day. She contacted me after the visit and offered to keep in touch in the future. Right now I can see the program as being most useful in establishing new mentor/mentee relationships. |

| Most of the faculty I met with see value in being involved in systems/quality improvement, but most do not express interest in specific projects. Areas needing improvement were identified by everyone I met with so developing projects around these areas should be doable. They might benefit from access to mentoring in quality improvement. | It was fantastic to meet with [visiting professor] and get a sense for his work and also brainstorm about how we might do similar work here in the future (eg, in high‐value care). It was also great to then see him 2 days later at [national conference]. I feel this is a great program to improve our connections cross‐institutionally and hopefully to spark some future collaborations. |

| Very worthwhile. Was really helpful to meet with various faculty and leadership to see similarities and differences between our institutions. Generated several ideas for collaborative activities already. Also really helpful to have a somewhat structured way to share my work at an outside institution, as well as to create opportunities for mentor‐mentee relationships outside my home institution. | Incredibly valuable to promote this kind of cross‐pollination for both collaboration and innovation. |

| Wonderful, inspiring, professionally advantageous. | |

| Good idea. Good way to help midcareer faculty with advancement. Offers promise for collaboration of research/workshops. | |

| Suggestions for Improvement | |

| Please have e‐mails of the folks we meet available immediately after the visit. It is hard to know if anyone felt enough of a connection to want mentorship from me. | I feel like I may be a bit early on to benefit as much as I could have. |

| Develop a mentorship program for quality improvement. As part of this exchange, consider treating visits as similar to a consultation. Have visitor with specific focus that they can offer help with. | Nice to have personal access to accomplished faculty from other institutions. Their perspective and career trajectory don't always align due to differences in institution culture, specifics of promotion process, and so on, but still a useful experience. |

| Share any possible more‐formal topics for discussion with leadership prior to the visit so can prepare ahead of time (eg, gather information they may have questions on). Otherwise it was great! | For early career faculty, more discussions prior in regard to what to expect. |

| A question is who should continue to push? Is it the prospective mentee, the mentee's institution, an so on? | Great idea. Would have loved to be involved in more aspects. More time for discussion would have been good. Did not get to discuss collaboration in person. |

| Great to get to talk to someone from totally different system. Wish we had more time to talk. | |

One‐year follow‐up was obtained for all but 1 early‐career faculty member receiving the follow‐up survey, and all 3 visiting professors. Of the 3 visiting professorships that occurred more than 1 year ago, 16 mentorship contacts occurred in total (phone, e‐mail, or in person) between 13 early‐career faculty and 3 visiting professors in the year after the initial visits (range, 04 contacts). Follow‐up contact occurred for 3 of 4 early‐career faculty from the first visiting professorship, 3 of 5 from the second visiting professorship, and 2 of 4 from the third visiting professorship. One early‐career faculty member from each host academic medical center had 3 or more additional contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the initial visit. Overall, 8/13 (62%) of early‐career faculty had at least 1 follow‐up mentoring discussion. On 1‐year follow‐up, overall utility for professional development was rated an average of 3.5 by early‐career faculty (with a trend of higher ratings of efficacy with increasing number of follow‐up contacts) and 4.7 by visiting professors. Half (8/16) of the involved faculty report having seen evidence of cross‐institutional dissemination of innovation. Ninety‐four percent (15/16) of participants at 1‐year follow‐up felt there was benefit to their institution in continuing the program for the next year.

Objective evidence of cross‐institutional scholarship, assessed by email query of both visiting professors and senior hospitalists coordinating the visits, includes 2 collaborative peer reviewed publications including mentors and mentees participating in the visiting professorship.[6, 7] Joint educational curriculum development on high‐value care between sites is planned. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has resulted in 1 external letter to support a visiting professor's promotion to date.

DISCUSSION

Hospital Medicine is a young, rapidly growing field, hence the number of experienced academic hospitalist mentors with expertise in successfully navigating an academic career is limited. A national study of hospitalist leaders found that 75% of clinician‐educators and 58% of research faculty feel that lack of mentorship is a major issue.[1] Mentorship for hospitalist clinician‐investigators is often delivered by nonhospitalists.[2, 8] There is little evidence of external mentorship for academic clinician‐educators in hospital medicine.[1] Without explicit programmatic support, many faculty may find this to be a barrier to career advancement. A study of successfully promoted hospitalists identified difficulty identifying external senior hospitalists to write letters in support of promotion as an obstacle.[9] Our study of the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program found that early‐career faculty rated the visit as useful in advancing their career and fostered external mentorship relationships. Subsequent experience suggests more than half of the early‐career faculty will maintain contact with the visiting professor over the year following the visit. Visiting professors rate the experience particularly highly in their own career advancement.

The hospitalist movement is built on a foundation of innovation. The focus of each presentation was on an innovation developed by the visiting professor, and each visit showcased an innovation of the visited institution. This is distinct from traditional Hospital Grand Rounds, which more often focus on basic science research or clinical pathophysiology/disease management based on subspecialty topics.[10] The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was judged by participants to be an effective means of spreading innovation.

Insights from experience with the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program include the importance of preliminary work prior to each visit. Program directors need to attend closely to the fit between the interests and career path of the visiting professor and those of the early‐career faculty. The innovations being shared should be aligned with organizational interests to maximize the chance of subsequent spread of the innovation and future collaboration. Providing faculty information about the objectives of the program in advance of the visit and arranging an exchange of curricula vitae between the early‐career faculty and the visiting professor allows participants to prepare for the in‐person coaching. Based on comments from participants, prompting contact from the visiting professor after the visit may be helpful to initiate the longitudinal relationship. We also found that early‐career faculty may not be aware of how to effectively use a mentoring relationship with an external faculty member. Training sessions for both mentors and mentees on effective mentorship relationships before visiting professorships might improve early‐career faculty confidence in initiating relationships and maximize value from mentor coaching.

A key issue is finding the right level of career maturity for the visiting professor. Our approach in selecting visiting professors was congruent with utilization of midcareer peer coaches employed by intrainstitutional hospital medicine mentoring programs.[11] The visiting professor should have sufficient experience and accomplishments to be able to effectively counsel junior faculty. However, it is important that the visiting professor also has sufficient time and interest to take on additional mentees and to be a full participant in shared scholarship projects emerging from the experience.

This study represents the experience of 5 mature academic hospitalist groups, and results may not be generalizable to dissimilar institutions or if only the most senior faculty are selected to perform visits. There is an inherent selection bias in the choice of both visiting professor and early‐career faculty. The small sample size of the faculty exposed to this program is a limitation to generalizability of the results of this evaluation. Whether this program will result in greater success in promotion of academic hospitalists cannot be assessed based on the follow‐up available. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has continued to be sustained with an additional academic medical center enrolled and 2 additional site visits planned. The costs of the program are low, largely air travel and a night of lodging, as well as nominal administrative logistical support. Perceived benefits by participants and academic medical centers make this modest investment worth considering for academic hospitalist groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program offers structure, opportunities, and access to senior mentors to advance the development of early‐career hospitalists while spreading innovation to distant sites. It is assessed by participants to facilitate external mentoring relationships and has the potential to advance the careers of both early‐career faculty as well as the visiting professors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Hospital medicine is an emerging specialty comprised predominantly of early‐career faculty, often less than 5 years postresidency and predominately at instructor or assistant professor level.[1] Effective mentoring has been identified as a critical component of academic success.[2, 3] Published data suggest that most academic hospitalists do not have a mentor, and when they do, the majority of them spend less than 4 hours per year with their mentor.[2] The reasons for this are multifactorial but largely result from the lack of structure, opportunities, and local senior academic hospitalists.[1, 4] Early‐career faculty have difficulty establishing external mentoring relationships, and new models beyond the traditional intrainstitutional dyad are needed.[3, 4] The need for mentors and structured mentorship networks may be particularly high in hospital medicine.[5]

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was designed to promote cross‐institutional mentorship, share hospitalist innovations, and facilitate academic collaboration between hospitalist groups. We describe the design and early experience with this program across 5 academic hospital medicine programs.

PROGRAM DESIGN

Objectives

The program was designed to promote mentoring relationships between early‐career hospitalist faculty and a visiting professor from another academic hospital medicine group. The program sought to provide immediate career advice during the visits, but also create opportunities for long‐term mentorship and collaboration between institutions. Goals for each visiting professorship included: (1) follow‐up contact between early‐career faculty and visiting professor in the 6 months following the visit, (2) long‐term mentoring relationship with at least 1 early‐career faculty at the visited institution, and (3) identification of opportunities for interinstitutional collaboration to disseminate innovations.

Selection of Sites and Faculty

The first 2 academic medical centers (AMCs) for the visiting professorship exchange designed the program (University of Colorado and University of New Mexico). In subsequent years, each participating AMC was able to solicit additional sites for faculty exchange. This model can expand without requiring ongoing central direction. No criteria were set for selection of AMCs. Visiting professors in hospital medicine were explicitly targeted to be at midcareer stage of late assistant professor or early associate professor and within 1 to 2 years of promotion. It was felt that this group would gain the maximal career benefit from delivering an invited visit to an external AMC, yet have a sufficient track record to deliver effective mentoring advice to early‐career hospitalists. The hospitalist group sending the visiting professor would propose a few candidates, with the innovations they would be able to present, and the hosting site would select 1 for the visit. Early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were generally instructor to early assistant professors.

Visit Itinerary

The visit itinerary was set up as follows:

- Visiting professor delivers a formal 1‐hour presentation to hospitalist faculty, describing an innovation in clinical care, quality improvement, patient safety, or education.

- Individual meetings with 3 to 5 early‐career hospitalists to review faculty portfolios and provide career advice.

- Group lunch between the visiting professor and faculty with similar interests to promote cross‐institutional networking and spark potential collaborations.

- Meeting with hospital medicine program leadership.

- Visiting professor receives exposure to an innovation developed at the hosting institution.

- Dinner with the hosting faculty including the senior hospitalist coordinating the visit.

In advance of the visit, both early‐career faculty and visiting professors receive written materials describing the program, its objectives, and tips to prepare for the visit (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). The curricula vitae of early‐career faculty at the hosting institution were provided to the visiting professor. Visit costs were covered by the visiting professor's institution. Honoraria were not offered.

Program Evaluation

Within a month of each visit, a paper survey was administered to the visiting professor and the faculty with whom she/he met. In addition to demographic data including gender, self‐reported minority status, academic rank, years at rank, and total years in academic medicine, the survey asked faculty to rate on a 5‐point Likert scale their assessment of the usefulness of the visit to accomplish the 4 core goals of the program: (1) cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations in clinical medicine, education, or research; (2) advancing the respondent's academic career; (3) fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships; and (4) promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Free‐text responses for overall impression of program and suggestions for improvement were solicited.

At the time of this writing, 1 year has passed from the initial visits for the first 3 visiting professorships. A 1‐year follow‐up survey was administered assessing (1) total number of contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the visit, (2) whether a letter of recommendation resulted from the visit, (3) whether the respondent had seen evidence of spread of innovative ideas as a result of the program, (4) participation in a cross‐institutional collaboration as a result of the program, and (5) assessment of benefit in continuing the program in the next year. The respondents were also asked to rate the global utility of the program to their professional development on a 5‐point scale ranging from not at all useful to very useful (Thinking about what has happened to you since the visit a year ago, please rate the usefulness of the entire program to your professional life: overall usefulness for my professional development.). Domain‐specific utility in improving clinical, research, quality improvement, and administrative skills were also elicited (results not shown). Finally, suggestions to improve the program for the future were solicited. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the study of this faculty development program did not qualify as human subjects research, and subjects were therefore not asked to provide informed consent for participation.

RESULTS

To date, 5 academic medical centers have participated in the visiting professorship program, with 7 visiting professors interacting with 29 early‐career faculty. Of the 29 early‐career faculty, 72% (21/29) were at the rank of assistant professor, 17% (5/29) instructor, 7% (2/29) residents with plans to hire, and 3% (1/29) associate professor. The median was 2 years in academic medicine and 1 year at current academic rank. Forty‐one percent (12/29) were women and 7% (2/29) identified as ethnic minority. Of the 7 visiting professors, 57% (4/7) were assistant professor and 43% (3/7) were associate professors. The median was 5 years in academic medicine, 29% (2/7) were women, and none identified as ethnic minority.

Immediate postvisit survey response was obtained for all participating faculty. In the immediate postvisit survey, on a 5‐point Likert scale, the 29 early‐career faculty rated the visit: 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.2 for advancing my academic career, 4.2 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.4 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. Ninety‐three percent (26/28 accounting for 1 nonresponse to this question) reported the visiting professorship had high potential to disseminate innovation (rated greater than 3 on the 5‐point Likert score). Eighty‐three percent (24/29) of the early‐career faculty rated the visit highly useful in advancing their career, 76% (22/29) responded that the visit was highly likely to foster external mentorship relationships, and 90% (26/29) reported the visit highly effective in promoting cross‐institutional collaborations. In the immediate postvisit survey, the 7 visiting professors rated the visit 4.9 for promoting cross‐institutional dissemination of innovations, 4.3 for advancing my academic career, 4.0 for fostering cross‐institutional mentor‐mentee relationships, and 4.3 for promoting cross‐institutional collaborations.

Free‐text comments from both visiting professors and early‐career faculty were generally favorable (Table 1). Some comments offered constructive input on appropriate matching of faculty, previsit preparation, or desire for more time in sessions (Table 1).

| Visiting Professors (n = 7) | Early‐Career Faculty (n = 29) |

|---|---|

| I was very impressed with the degree of organization, preparation, and structure from [host institution]. The project is a great concept and may well lead to similar and even more developed ones in the future. It is very helpful to get the pulse on another program and to hear of some of the same struggles and successes of another hospitalist program. The potential for cross‐site mentor‐mentee relationships and collaborations is a win‐win for both programs. | I really enjoyed my individual meeting with [visiting professor]. She was helpful in reviewing current projects from another perspective and very helpful in making suggestions for future projects. Also enjoyed her Grand Rounds and plan to follow‐up on this issue for possible cross‐institutional collaboration. |

| Overall, this exchange is a great program. It is fun, promotes idea exchange, and is immensely helpful to the visiting professor for promotion. Every meeting I had with faculty at [host institution] was interesting and worthwhile. The primary challenge is maintaining mentorship ties and momentum after the visit. I personally e‐mailed every person I met and received many responses, including several explicit requests for ongoing advising and collaboration. | I think this is a great program. It definitely gives us the opportunity to meet people outside of the [host institution] community and foster relationships, mentorship, and possible collaborations with projects and programs. |

| I liked multidisciplinary rounding. Research club. Meeting with faculty and trying to find common areas of interest. | I think this is a fantastic program so far. [Visiting professor] was very energetic and interested in making the most of the day. She contacted me after the visit and offered to keep in touch in the future. Right now I can see the program as being most useful in establishing new mentor/mentee relationships. |

| Most of the faculty I met with see value in being involved in systems/quality improvement, but most do not express interest in specific projects. Areas needing improvement were identified by everyone I met with so developing projects around these areas should be doable. They might benefit from access to mentoring in quality improvement. | It was fantastic to meet with [visiting professor] and get a sense for his work and also brainstorm about how we might do similar work here in the future (eg, in high‐value care). It was also great to then see him 2 days later at [national conference]. I feel this is a great program to improve our connections cross‐institutionally and hopefully to spark some future collaborations. |

| Very worthwhile. Was really helpful to meet with various faculty and leadership to see similarities and differences between our institutions. Generated several ideas for collaborative activities already. Also really helpful to have a somewhat structured way to share my work at an outside institution, as well as to create opportunities for mentor‐mentee relationships outside my home institution. | Incredibly valuable to promote this kind of cross‐pollination for both collaboration and innovation. |

| Wonderful, inspiring, professionally advantageous. | |

| Good idea. Good way to help midcareer faculty with advancement. Offers promise for collaboration of research/workshops. | |

| Suggestions for Improvement | |

| Please have e‐mails of the folks we meet available immediately after the visit. It is hard to know if anyone felt enough of a connection to want mentorship from me. | I feel like I may be a bit early on to benefit as much as I could have. |

| Develop a mentorship program for quality improvement. As part of this exchange, consider treating visits as similar to a consultation. Have visitor with specific focus that they can offer help with. | Nice to have personal access to accomplished faculty from other institutions. Their perspective and career trajectory don't always align due to differences in institution culture, specifics of promotion process, and so on, but still a useful experience. |

| Share any possible more‐formal topics for discussion with leadership prior to the visit so can prepare ahead of time (eg, gather information they may have questions on). Otherwise it was great! | For early career faculty, more discussions prior in regard to what to expect. |

| A question is who should continue to push? Is it the prospective mentee, the mentee's institution, an so on? | Great idea. Would have loved to be involved in more aspects. More time for discussion would have been good. Did not get to discuss collaboration in person. |

| Great to get to talk to someone from totally different system. Wish we had more time to talk. | |

One‐year follow‐up was obtained for all but 1 early‐career faculty member receiving the follow‐up survey, and all 3 visiting professors. Of the 3 visiting professorships that occurred more than 1 year ago, 16 mentorship contacts occurred in total (phone, e‐mail, or in person) between 13 early‐career faculty and 3 visiting professors in the year after the initial visits (range, 04 contacts). Follow‐up contact occurred for 3 of 4 early‐career faculty from the first visiting professorship, 3 of 5 from the second visiting professorship, and 2 of 4 from the third visiting professorship. One early‐career faculty member from each host academic medical center had 3 or more additional contacts with the visiting professor in the year following the initial visit. Overall, 8/13 (62%) of early‐career faculty had at least 1 follow‐up mentoring discussion. On 1‐year follow‐up, overall utility for professional development was rated an average of 3.5 by early‐career faculty (with a trend of higher ratings of efficacy with increasing number of follow‐up contacts) and 4.7 by visiting professors. Half (8/16) of the involved faculty report having seen evidence of cross‐institutional dissemination of innovation. Ninety‐four percent (15/16) of participants at 1‐year follow‐up felt there was benefit to their institution in continuing the program for the next year.

Objective evidence of cross‐institutional scholarship, assessed by email query of both visiting professors and senior hospitalists coordinating the visits, includes 2 collaborative peer reviewed publications including mentors and mentees participating in the visiting professorship.[6, 7] Joint educational curriculum development on high‐value care between sites is planned. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has resulted in 1 external letter to support a visiting professor's promotion to date.

DISCUSSION

Hospital Medicine is a young, rapidly growing field, hence the number of experienced academic hospitalist mentors with expertise in successfully navigating an academic career is limited. A national study of hospitalist leaders found that 75% of clinician‐educators and 58% of research faculty feel that lack of mentorship is a major issue.[1] Mentorship for hospitalist clinician‐investigators is often delivered by nonhospitalists.[2, 8] There is little evidence of external mentorship for academic clinician‐educators in hospital medicine.[1] Without explicit programmatic support, many faculty may find this to be a barrier to career advancement. A study of successfully promoted hospitalists identified difficulty identifying external senior hospitalists to write letters in support of promotion as an obstacle.[9] Our study of the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program found that early‐career faculty rated the visit as useful in advancing their career and fostered external mentorship relationships. Subsequent experience suggests more than half of the early‐career faculty will maintain contact with the visiting professor over the year following the visit. Visiting professors rate the experience particularly highly in their own career advancement.

The hospitalist movement is built on a foundation of innovation. The focus of each presentation was on an innovation developed by the visiting professor, and each visit showcased an innovation of the visited institution. This is distinct from traditional Hospital Grand Rounds, which more often focus on basic science research or clinical pathophysiology/disease management based on subspecialty topics.[10] The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program was judged by participants to be an effective means of spreading innovation.

Insights from experience with the Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program include the importance of preliminary work prior to each visit. Program directors need to attend closely to the fit between the interests and career path of the visiting professor and those of the early‐career faculty. The innovations being shared should be aligned with organizational interests to maximize the chance of subsequent spread of the innovation and future collaboration. Providing faculty information about the objectives of the program in advance of the visit and arranging an exchange of curricula vitae between the early‐career faculty and the visiting professor allows participants to prepare for the in‐person coaching. Based on comments from participants, prompting contact from the visiting professor after the visit may be helpful to initiate the longitudinal relationship. We also found that early‐career faculty may not be aware of how to effectively use a mentoring relationship with an external faculty member. Training sessions for both mentors and mentees on effective mentorship relationships before visiting professorships might improve early‐career faculty confidence in initiating relationships and maximize value from mentor coaching.

A key issue is finding the right level of career maturity for the visiting professor. Our approach in selecting visiting professors was congruent with utilization of midcareer peer coaches employed by intrainstitutional hospital medicine mentoring programs.[11] The visiting professor should have sufficient experience and accomplishments to be able to effectively counsel junior faculty. However, it is important that the visiting professor also has sufficient time and interest to take on additional mentees and to be a full participant in shared scholarship projects emerging from the experience.

This study represents the experience of 5 mature academic hospitalist groups, and results may not be generalizable to dissimilar institutions or if only the most senior faculty are selected to perform visits. There is an inherent selection bias in the choice of both visiting professor and early‐career faculty. The small sample size of the faculty exposed to this program is a limitation to generalizability of the results of this evaluation. Whether this program will result in greater success in promotion of academic hospitalists cannot be assessed based on the follow‐up available. The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program has continued to be sustained with an additional academic medical center enrolled and 2 additional site visits planned. The costs of the program are low, largely air travel and a night of lodging, as well as nominal administrative logistical support. Perceived benefits by participants and academic medical centers make this modest investment worth considering for academic hospitalist groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The Visiting Professorship in Hospital Medicine Program offers structure, opportunities, and access to senior mentors to advance the development of early‐career hospitalists while spreading innovation to distant sites. It is assessed by participants to facilitate external mentoring relationships and has the potential to advance the careers of both early‐career faculty as well as the visiting professors.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5–9.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , . Mentoring faculty in academic medicine: a new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870.

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:240–246.

- , . The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1–2.

- , , , . Procedural skills for hospitalists. Hosp Med Clin. 2016;5:114–136.

- , , . Cedecea davisae' s role in a polymicrobial lung infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Case reports in infectious diseases. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:176864.

- , , , . Innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314–318.

- , , , , . Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:411–415.

- , , , , . A case study of medical grand rounds: are we using effective methods? Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1144–1151.

- , , , . Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161–166.

- , , , . Survey of US academic hospitalist leaders about mentorship and academic activities in hospitalist groups. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:5–9.

- , , , , , . Mentorship, productivity, and promotion among academic hospitalists. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):23–27.

- , . Mentoring faculty in academic medicine: a new paradigm? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):866–870.

- , , , , , . Challenges and opportunities in academic hospital medicine: report from the Academic Hospital Medicine Summit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:240–246.

- , . The need for mentors in the odyssey of the academic hospitalist. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:1–2.

- , , , . Procedural skills for hospitalists. Hosp Med Clin. 2016;5:114–136.

- , , . Cedecea davisae' s role in a polymicrobial lung infection in a cystic fibrosis patient. Case reports in infectious diseases. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2012;2012:176864.

- , , , . Innovative approach to supporting hospitalist physicians towards academic success. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:314–318.

- , , , , . Tried and true: a survey of successfully promoted academic hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:411–415.

- , , , , . A case study of medical grand rounds: are we using effective methods? Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1144–1151.

- , , , . Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161–166.

SC Insulin Order Sets and Protocols

Inpatient glycemic control and hypoglycemia are issues with well deserved increased attention in recent years. Prominent guidelines and technical reviews have been published,13 and a recent, randomized controlled trial demonstrated the superiority of basal bolus insulin regimens compared to sliding‐scale regimens.4 Effective glycemic control for inpatients has remained elusive in most medical centers. Recent reports57 detail clinical inertia and the continued widespread use of sliding‐scale subcutaneous insulin regimens, as opposed to the anticipatory, physiologic basal‐nutrition‐correction dose insulin regimens endorsed by these reviews.

Inpatient glycemic control faces a number of barriers, including fears of inducing hypoglycemia, uneven knowledge and training among staff, and competing institutional and patient priorities. These barriers occur in the background of an inherently complex inpatient environment that poses unique challenges in maintaining safe glycemic control. Patients frequently move across a variety of care teams and geographic locations during a single inpatient stay, giving rise to multiple opportunities for failed communication, incomplete handoffs, and inconsistent treatment. In addition, insulin requirements may change dramatically due to variations in the stress of illness, exposure to medications that effect glucose levels, and varied forms of nutritional intake with frequent interruption. Although insulin is recognized as one of the medications most likely to be associated with adverse events in the hospital, many hospitals do not have protocols or order sets in place to standardize its use.

A Call to Action consensus conference,8, 9 hosted by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), brought together many thought leaders and organizations, including representation from the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), to address these barriers and to outline components necessary for successful implementation of a program to improve inpatient glycemic control in the face of these difficulties. Institutional insulin management protocols and standardized insulin order sets (supported by appropriate educational efforts) were identified as key interventions. It may be tempting to quickly deploy a generic insulin order set in an effort to improve care. This often results in mediocre results, due to inadequate incorporation of standardization and guidance into the order set and other documentation tools, and uneven use of the order set.

The SHM Glycemic Control Task Force (GCTF) recommends the following steps for developing and implementing successful protocols and order sets addressing the needs of the noncritical care inpatient with diabetes/hyperglycemia.

-

Form a steering committee for this work, and assess the current processes of care.

-

Identify best practices and preferred regimens to manage diabetes and hyperglycemia in the hospital.

-

Integrate best practices and preferred institutional choices into an inpatient glycemic control protocol. Crystallize your protocol into a one page summary.

-

Place guidance from your protocol into the flow of work, by integrating it into standardized subcutaneous insulin order sets and other documentation and treatment tools.

-

Monitor the use of your order sets and protocol. Intervene actively on nonadherents to your protocol and those with poor glycemic control, and revise your protocol/order sets as needed.

IDENTIFYING AND INCORPORATING KEY CONCEPTS AND BEST PRACTICES

A protocol is a document that endorses specific monitoring and treatment strategies in a given institution. This potentially extensive document should provide guidance for transitions, special situations (like steroids and total parenteral nutrition [TPN]) and should outline preferred insulin regimens for all of the most common nutritional situations. One of the most difficult parts of creating a protocol is the assimilation of all of the important information on which to base decisions. Your protocol and order set will be promoting a set of clinical practices. Fortunately, the current best practice for noncritical care hyperglycemic patients has been summarized by several authoritative sources,13, 811 including references from the SHM Glycemic Task Force published in this supplement.4, 12

Table 1 summarizes the key concepts that should be emphasized in a protocol for subcutaneous insulin management in the hospital. We recommend embedding guidance from your protocol into order sets, the medication administration record, and educational materials. Although the details contained in a protocol and order set might vary from one institution to another, the key concepts should not. The remainder of this article provides practical information about how these concepts and guidance for how preferred insulin regimens should be included in these tools. Appendices 1 and 2 give examples of an institutional one‐page summary protocol and subcutaneous insulin order set, respectively.

| 1. Establish a target range for blood glucose levels. |

| 2. Standardize monitoring of glucose levels and assessment of long‐term control (HbA1c). |

| 3. Incorporate nutritional management. |

| 4. Prompt clinicians to consider discontinuing oral antihyperglycemic medications. |

| 5. Prescribe physiologic (basal‐nutrition‐correction) insulin regimens. |

| a. Choose a total daily dose (TDD). |

| b. Divide the TDD into physiologic components of insulin therapy and provide basal and nutritional/correction separately. |

| c. Choose and dose a basal insulin. |

| d. Choose and dose a nutritional (prandial) insulin |

|

i. Match exactly to nutritional intake (see Table 2). |

| ii. Include standing orders to allow nurses to hold nutritional insulin for nutritional interruptions and to modify nutritional insulin depending on the actual nutritional intake. |

| e. Add correction insulin |

| i. Match to an estimate of the patients insulin sensitivity using prefabricated scales. |

| ii. Use the same insulin as nutritional insulin. |

| 6. Miscellaneous |

| a. Manage hypoglycemia in a standardized fashion and adjust regimen to prevent recurrences. |

| b. Provide diabetes education and appropriate consultation. |

| c. Coordinate glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration. |

| d. Tailor discharge treatment regimens to the patient's individual circumstances and arrange for proper follow‐up. |

Standardize the Monitoring of Blood Glucose Values and Glucosylated Hemoglobin

Guidance for the coordination of glucose testing, nutrition delivery, and insulin administration, should be integrated into your protocols, and order sets. For noncritical care areas, the minimal frequency for blood glucose monitoring for patients who are eating is before meals and at bedtime. For the patient designated nothing by mouth (NPO) or the patient on continuous tube feeding, the type of nutritional/correction insulin used should drive the minimum frequency (every 4‐6 hours if rapid acting analog insulins [RAA‐I] are used, and every 6 hours if regular insulin is used). Directions for administering scheduled RAA‐I immediately before or immediately after nutrition delivery should be incorporated into protocols, order sets, and medication administration records. Unfortunately, having this guidance in the order sets and protocols does not automatically translate into its being carried out in the real world. Wide variability in the coordination of glucose monitoring, nutritional delivery, and insulin administration is common, so monitoring the process to make sure the protocol is followed is important.

Obtaining a glucosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level is important in gauging how well the patient's outpatient regimen is maintaining glycemic control, distinguishing stress hyperglycemia from established diabetes, and guiding the inpatient approach to glycemic control. ADA guidelines2, 3 endorse obtaining HbA1c levels of inpatients if these levels are not already available from the month prior to admission.

Establish a Target Range for Blood Glucose in NonCritical Care Areas

It is important to adopt a glycemic target that is institution‐wide, for critical care areas and noncritical care areas alike. Your glycemic target need not be identical to the ADA/AACE glycemic targets, but should be similar to them.

Examples of institutional glycemic targets for noncritical care areas:

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL, maximum random glucose <180 mg/dL (ADA/AACE consensus target)

-

90‐150 mg/dL (a target used in some hospitals)

-

Preprandial target 90‐130 mg/dL for most patients, 100‐150 mg/dL if there are hypoglycemia risk factors, and <180 mg/dL if comfort‐care or end‐of‐life care (a more refined target, allowing for customization based on patient characteristics).

Your multidisciplinary glycemic control steering committee should pick the glycemic target it can most successfully implement and disseminate. It is fine to start with a conservative target and then ratchet down the goals as the environment becomes more accepting of the concept of tighter control of blood glucose in the hospital.

Although the choice of glycemic target is somewhat arbitrary, establishing an institutional glycemic target is critical to motivate clinical action. Your committee should design interventions, for instances when a patient's glycemic target is consistently not being met, including an assignment of responsibility.

Prompt Clinicians to Consider Discontinuing Oral Agents

Oral antihyperglycemic agents, in general, are difficult to quickly titrate to effect, and have side effects that limit their use in the hospital. In contrast, insulin acts rapidly and can be used in virtually all patients and clinical situations, making it the treatment of choice for treatment of hyperglycemia in the hospital.3, 11, 12 In certain circumstances, it may be entirely appropriate to continue a well‐controlled patient on his or her prior outpatient oral regimen. It is often also reasonable to resume oral agents in some patients when preparing for hospital discharge.

Incorporate Nutritional Management

Because diet is so integral to the management of diabetes and hyperglycemia, diet orders should be embedded in all diabetes or insulin‐related order sets. Diets with the same amount of carbohydrate with each meal should be the default rule for patients with diabetes. Nutritionist consultation should be considered and easy to access for patients with malnutrition, obesity, and other common conditions of the inpatient with diabetes.

Access Diabetes Education and Appropriate Consultation

Diabetes education should be offered to all hyperglycemic patients with normal mental status, complete with written materials, a listing of community resources, and survival skills. Consultation with physicians in internal medicine or endocrinology for difficult‐to‐control cases, or for cases in which the primary physician of record is not familiar with (or not adherent to) principles of inpatient glycemic management, should be very easy to obtain, or perhaps mandated, depending on your institution‐specific environment.

Prescribe Physiologic (Basal‐Nutritional‐Correction Dose) Insulin Regimens

Physiologic insulin use is the backbone of the recommended best practice for diabetes and hyperglycemia management in the hospital. The principles of such regimens are summarized elsewhere in this supplement.12 These principles will not be reiterated in detail here, but the major concepts that should be integrated into the protocols and order sets will be highlighted.

Choose a Total Daily Dose

Clinicians need guidance on how much subcutaneous insulin they should give a patient. These doses are well known from clinical experience and the published literature. The fear of hypoglycemia usually results in substantial underdosing of insulin, or total avoidance of scheduled insulin on admission. Your team should provide guidance for how much insulin to start a patient on when it is unclear from past experience how much insulin the patient needs. Waiting a few days to see how much insulin is required via sliding‐scale‐only regimens is a bad practice that should be discouraged for patients whose glucose values are substantially above the glycemic target. The total daily dose (TDD) can be estimated in several different ways (as demonstrated in Appendix 1 and 2), and protocols should make this step very clear for clinicians. Providing a specific location on the order set to declare the TDD may help ensure this step gets done more reliably. Some institutions with computer physician order entry (CPOE) provide assistance with calculating the TDD and the allocation of basal and nutritional components, based on data the ordering physician inputs into the system.

Select and Dose a Basal Insulin