User login

Generalized Fixed Drug Eruptions Require Urgent Care: A Case Series

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

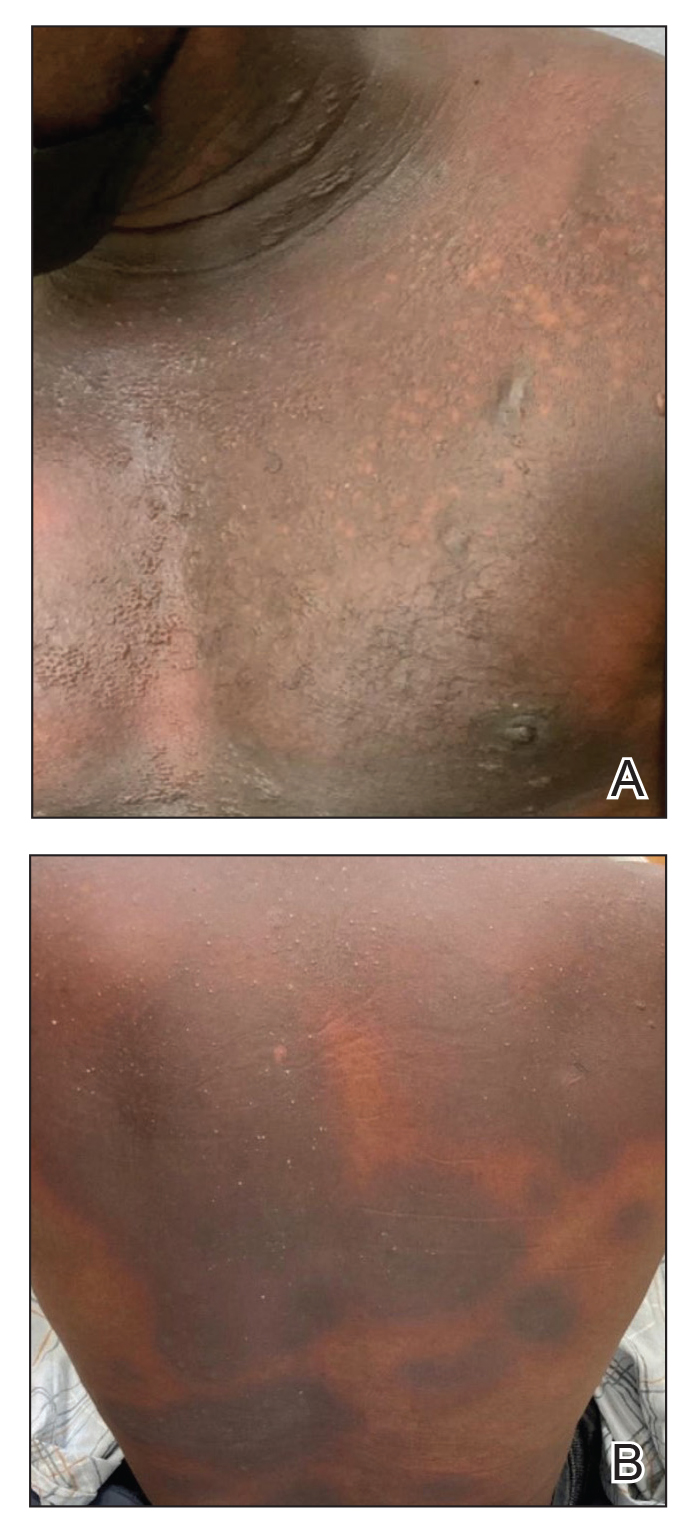

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

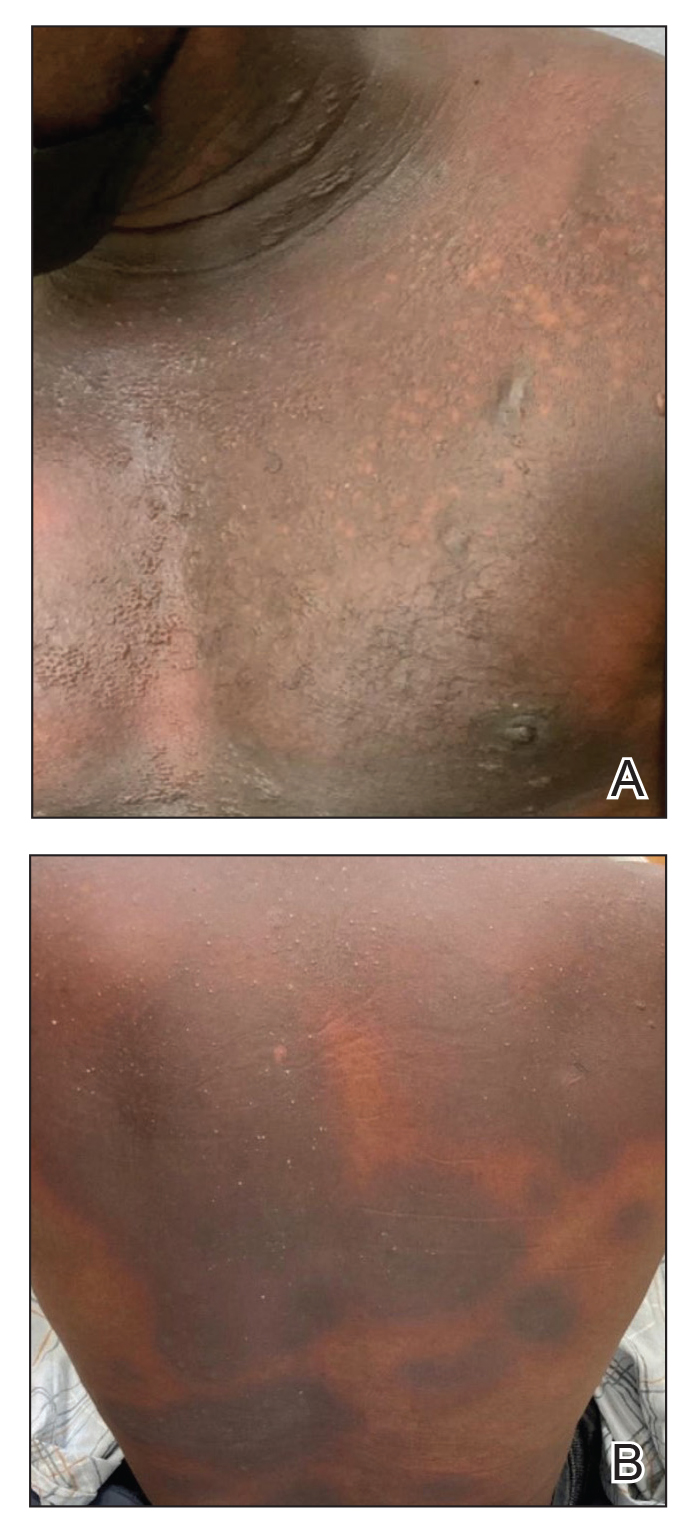

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

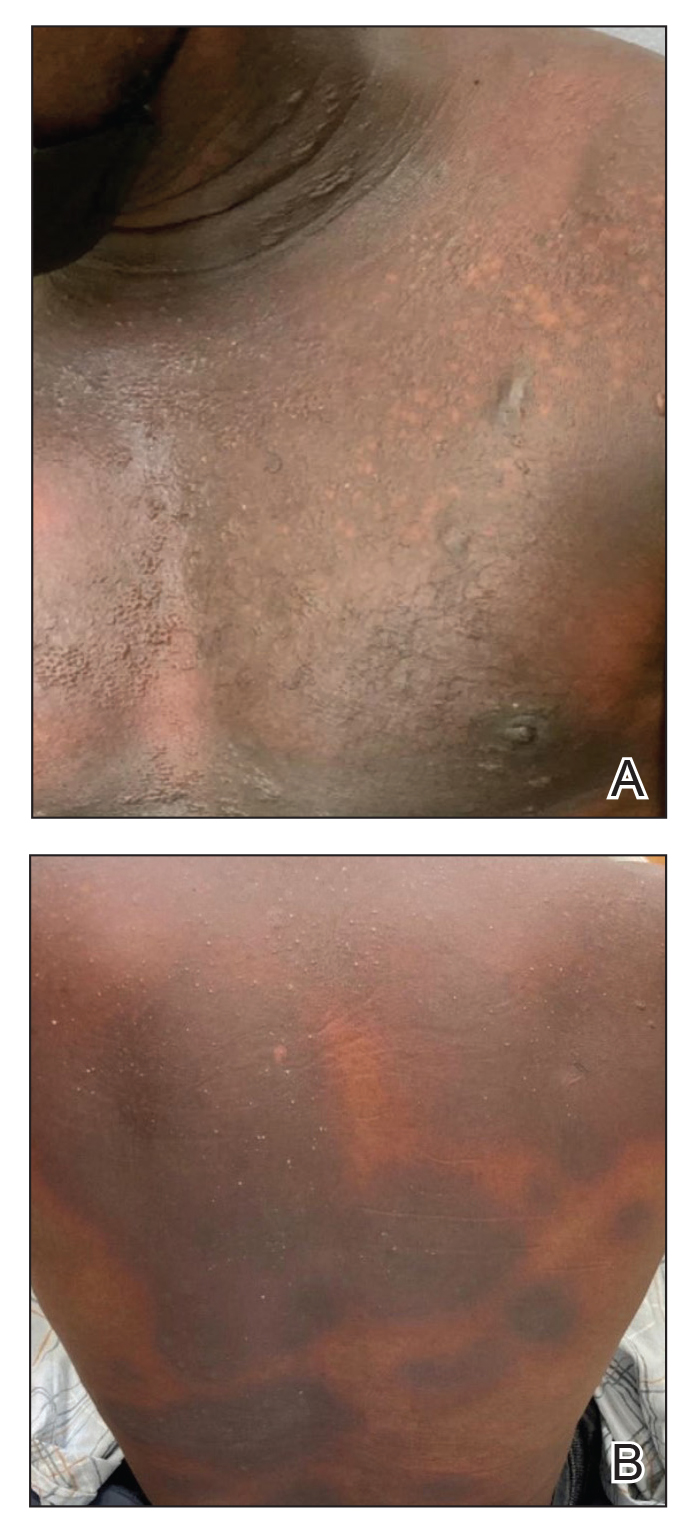

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

Recognizing cutaneous drug eruptions is important for treatment and prevention of recurrence. Fixed drug eruptions (FDEs) typically are harmless but can have major negative cosmetic consequences for patients. In its more severe forms, patients are at risk for widespread epithelial necrosis with accompanying complications. We report 1 patient with generalized FDE and 2 with generalized bullous FDE. We also discuss the recognition and treatment of the condition. Two patients previously had been diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Case Series

Patient 1—A 60-year-old woman presented to dermatology with a rash on the trunk and groin folds of 4 days’ duration. She had a history of SLE and cutaneous lupus treated with hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids. She had started sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim for a urinary tract infection with a rash appearing 1 day later. She reported burning skin pain with progression to blisters that “sloughed” off. She denied any known history of allergy to sulfa drugs. Prior to evaluation by dermatology, she visited an urgent care facility and was prescribed hydroxyzine and intramuscular corticosteroids. At presentation to dermatology 3 days after taking sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, she had annular flaccid bullae and superficial erosions with dusky borders on the right posterior thigh, right side of the chest, left inframammary fold, and right inguinal fold (Figure 1). She had no ocular, oral, or vaginal erosions. A diagnosis of generalized bullous FDE was favored over erythema multiforme or Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS)/toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Shave biopsies from lesions on the right posterior thigh and right inguinal fold demonstrated interface dermatitis with epidermal necrosis, pigment incontinence, and numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional skin was negative for immunoprotein deposition. These findings were consistent with the clinical impression of generalized bullous FDE. Prior to receiving the histopathology report, the patient was initiated on a regimen of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/d in the setting of normal renal function and followed until the eruption resolved completely. Cyclosporine was tapered at 2 weeks and discontinued at 3 weeks.

Patient 2—A 32-year-old woman presented for follow-up management of discoid lupus erythematosus. She had a history of systemic and cutaneous lupus, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, and mixed connective tissue disease managed with prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and belimumab. Physical examination revealed scarring alopecia with dyspigmentation and active inflammation consistent with uncontrolled cutaneous lupus. However, she also had oval-shaped hyperpigmented patches over the left breast, clavicle, and anterior chest consistent with a generalized FDE (Figure 2). The patient did not recall a history of similar lesions and could not identify a possible trigger. She was counseled on possible culprits and advised to avoid unnecessary medications. She had an unremarkable clinical course; therefore, no further intervention was necessary.

Patient 3—A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a painful rash on the chest and back of 2 days’ duration that began 1 hour after taking naproxen (dosage unknown) for back pain. He had no notable medical history. The patient stated that the rash had slowly worsened and started to develop blisters. He visited an urgent care facility 1 day prior to the current presentation and was started on a 5-day course of prednisone 40 mg daily; the first 2 doses did not help. He denied any mucosal involvement apart from a tender lesion on the penis. He reported a history of an allergic reaction to penicillin. Physical examination revealed extensive dusky violaceous annular plaques with erythematous borders across the anterior and posterior trunk (Figure 3). Multiple flaccid bullae developed within these plaques, involving 15% of the body surface area. He was diagnosed with generalized bullous FDE based on the clinical history and histopathology. He was admitted to the burn intensive care unit and treated with cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d with subsequent resolution of the eruption.

Comment

Presentation of FDEs—A fixed drug eruption manifests with 1 or more well-demarcated, red or violaceous, annular patches that resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation; it occasionally may manifest with bullae. Initial eruptions may occur up to 2 weeks following medication exposure, but recurrent eruptions usually happen within minutes to hours later. They often are in the same location as prior lesions. A fixed drug eruption can be solitary, scattered, or generalized; a generalized FDE typically demonstrates multiple bilateral lesions that may itch, burn, or cause no symptoms. Patients can experience an FDE at any age, though the median age is reported as 35 to 60 years of age.1 A fixed drug eruption usually occurs after ingestion of oral medications, though there have been a few reports with iodinated contrast.2 Well-known culprits include antibiotics (eg, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, tetracyclines, penicillins/cephalosporins, quinolones, dapsone), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (eg, paracetamol), barbiturates, antimalarials, and anticonvulsants. It also can occur with vaccines or with certain foods (fixed food eruption).3,4 Clinicians may try an oral drug challenge to identify the cause of an FDE, but in patients with a history of a generalized FDE, the risk for developing an increasingly severe reaction with repeated exposure to the medication is too high.5

Histopathology—Patch testing at the site of prior eruption with suspected drug culprits may be useful.6 Histopathology of FDE typically demonstrates vacuolar changes at the dermoepidermal junction with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate. Early lesions often show a predominance of eosinophils. Subepidermal clefting is a feature of the bullous variant. In an active lesion, there are large numbers of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing natural killer cell–associated molecules.7 The pathologic mechanism is not well understood, though it has been hypothesized that memory CD8+ cells are maintained in specific regions of the epidermis by IL-15 produced in the microenvironment and are activated upon rechallenge.7Considerations in Generalized Bullous FDE—Generalized FDE is defined in the literature as an FDE with involvement of 3 of 6 body areas: head, neck, trunk, upper limbs, lower limbs, and genital area. It may cover more or less than 10% of the body surface area.8-10 Although an isolated FDE frequently is asymptomatic and may not be cause for alarm, recurring drug eruptions increase the risk for development of generalized bullous FDE. Generalized bullous FDE is a rare subset. It is frequently misdiagnosed, and data on its incidence are uncertain.11 Of note, several pathologies causing bullous lesions may be in the differential diagnosis, including bullous pemphigoid; pemphigus vulgaris; bullous SLE; or bullae from cutaneous lupus, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, erythema multiforme, or SJS/TEN.12 When matched for body surface area involvement with SJS/TEN, generalized bullous FDE shares nearly identical mortality rates10; therefore, these patients should be treated with the same level of urgency and admitted to a critical care or burn unit, as they are at serious risk for infection and other complications.13

Clinical history and presentation along with histopathologic findings help to narrow down the differential diagnosis. Clinically, generalized bullous FDE does not affect the surrounding skin and manifests sooner after drug exposure (1–24 hours) with less mucosal involvement than SJS/TEN.9 Additionally, SJS/TEN patients frequently have generalized malaise and/or fever, while generalized bullous FDE patients do not. Finally, patients with generalized bullous FDE may report a history of a cutaneous eruption similar in morphology or in the same location.

Histopathologically, generalized bullous FDE may be similar to FDE with the addition of a subepidermal blister. Generalized bullous FDE patients have greater eosinophil infiltration and dermal melanophages than patients with SJS/TEN.9 Cellular infiltrates in generalized bullous FDE include more dermal CD41 cells, such as Foxp31 regulatory T cells; fewer intraepidermal CD561 cells; and fewer intraepidermal cells with granulysin.9 Occasionally, generalized bullous FDE causes full-thickness necrosis. In those cases, generalized bullous FDE cannot reliably be distinguished from other conditions with epidermal necrolysis on histopathology.13

FDE Diagnostics—A cytotoxin produced by

Management—Avoidance of the inciting drug often is sufficient for patients with an FDE, as demonstrated in patient 2 in our case series. Clinicians also should counsel patients on avoidance of potential cross-reacting drugs. Symptomatic treatment for itch or pain is appropriate and may include antihistamines or topical steroids. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may exacerbate or be causative of FDE. For generalized bullous FDE, cyclosporine is favored in the literature15,16 and was used to successfully treat both patients 1 and 3 in our case series. A short course of systemic corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin also may be considered. Mild cases of generalized bullous FDE may be treated with close outpatient follow-up (patient 1), while severe cases require inpatient or even critical care monitoring with aggressive medical management to prevent the progression of skin desquamation (patient 3). Patients with severe oral lesions may require inpatient support for fluid maintenance.

Lupus History—Two patients in our case series had a history of lupus. Lupus itself can cause primary bullous lesions. Similar to FDE, bullous SLE can involve sun-exposed and nonexposed areas of the skin as well as the mucous membranes with a predilection for the lower vermilion lip.17 In bullous SLE, tense subepidermal blisters with a neutrophil-rich infiltrate form due to circulating antibodies to type VII collagen. These blisters have an erythematous or urticated base, most commonly on the face, upper trunk, and proximal extremities.18 In both SLE with skin manifestations and lupus limited to the skin, bullae may form due to extensive vacuolar degeneration. Similar to TEN, they can form rapidly in a widespread distribution.17 However, there is limited mucosal involvement, no clear drug association, and a better prognosis. Bullae caused by lupus will frequently demonstrate deposition of immunoproteins IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement component 3 at the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin on direct immunofluorescence. However, negative direct immunofluorescence does not rule out lupus.12 At the same time, patients with lupus frequently have comorbidities requiring multiple medications; the need for these medications may predispose patients to higher rates of cutaneous drug eruptions.19 To our knowledge, there is no known association between FDE and lupus.

Conclusion

Patients with acute eruptions following the initiation of a new prescription or over-the-counter medication require urgent evaluation. Generalized bullous FDE requires timely diagnosis and intervention. Patients with lupus have an increased risk for cutaneous drug eruptions due to polypharmacy. Further investigation is necessary to determine if there is a pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of FDE in lupus patients.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

- Anderson HJ, Lee JB. A review of fixed drug eruption with a special focus on generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:925.

- Gavin M, Sharp L, Walker K, et al. Contrast-induced generalized bullous fixed drug eruption resembling Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:601-602.

- Kabir S, Feit EJ, Heilman ER. Generalized fixed drug eruption following Pfizer-BioNtech COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:E6684.

- Choi S, Kim SH, Hwang JH, et al. Rapidly progressing generalized bullous fixed drug eruption after the first dose of COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccination. J Dermatol. 2023;50:1190-1193.

- Mahboob A, Haroon TS. Drugs causing fixed eruptions: a study of 450 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:833-838.

- Shiohara T. Fixed drug eruption: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;9:316-321.

- Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Shiohara T. In vivo dynamics of intraepidermal CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells during the evolution of fixed drug eruption. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:1230-1238.

- Lee CH, Chen YC, Cho YT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption: a retrospective study in a single referral center in northern Taiwan. Dermatologica Sinica. 2012;30:11-15.

- Cho YT, Lin JW, Chen YC, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption is distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis by immunohistopathological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:539-548.

- Lipowicz S, Sekula P, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, et al. Prognosis of generalized bullous fixed drug eruption: comparison with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:726-732.

- Patel S, John AM, Handler MZ, et al. Fixed drug eruptions: an update, emphasizing the potentially lethal generalized bullous fixed drug eruption. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:393-399.

- Ranario JS, Smith JL. Bullous lesions in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:44-49.

- Perron E, Viarnaud A, Marciano L, et al. Clinical and histological features of fixed drug eruption: a single-centre series of 73 cases with comparison between bullous and non-bullous forms. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:372-380.

- Chen CB, Kuo KL, Wang CW, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1327-1337.e3.

- Beniwal R, Gupta LK, Khare AK, et al. Cyclosporine in generalized bullous-fixed drug eruption. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:432-433.

- Vargas Mora P, García S, Valenzuela F, et al. Generalized bullous fixed drug eruption successfully treated with cyclosporine. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13492.

- Montagnon CM, Tolkachjov SN, Murrell DF, et al. Subepithelial autoimmune blistering dermatoses: clinical features and diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1-14.

- Sebaratnam DF, Murrell DF. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Clin. 2011;29:649-653.

- Zonzits E, Aberer W, Tappeiner G. Drug eruptions from mesna. After cyclophosphamide treatment of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:80-82.

Practice Points

- Although localized fixed drug eruption (FDE) is a relatively benign diagnosis, generalized bullous FDE requires urgent management and may necessitate intensive burn care.

- Patients with lupus are at increased risk for drug eruptions due to polypharmacy, and there is a wide differential for bullous eruptions in these patients.

Botanical Briefs: Fig Phytophotodermatitis (Ficus carica)

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

Plant Parts and Nomenclature

Ficus carica (common fig) is a deciduous shrub or small tree with smooth gray bark that can grow up to 10 m in height (Figure 1). It is characterized by many spreading branches, but the trunk rarely grows beyond a diameter of 7 in. Its hairy leaves are coarse on the upper side and soft underneath with 3 to 7 deep lobes that can extend up to 25 cm in length or width; the leaves grow individually, alternating along the sides of the branches. Fig trees often can be seen adorning yards, gardens, and parks, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Ficus carica should not be confused with Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), a common ornamental tree that also is used to provide shade in hot climates, though both can cause phototoxic skin eruptions.

The common fig tree originated in the Mediterranean and western Asia1 and has been cultivated by humans since the second and third millennia

Ficus carica is a member of the Moraceae family (derived from the Latin name for the mulberry tree), which includes 53 genera and approximately 1400 species, of which about 850 belong to the genus Ficus (the Latin name for a fig tree). The term carica likely comes from the Latin word carricare (to load) to describe a tree loaded with figs. Family members include trees, shrubs, lianas, and herbs that usually contain laticifers with a milky latex.

Traditional Uses

For centuries, components of the fig tree have been used in herbal teas and pastes to treat ailments ranging from sore throats to diarrhea, though there is no evidence to support their efficacy.4 Ancient Indians and Egyptians used plants such as the common fig tree containing furocoumarins to induce hyperpigmentation in vitiligo.5

Phototoxic Components

The leaves and sap of the common fig tree contain psoralens, which are members of the furocoumarin group of chemical compounds and are the source of its phototoxicity. The fruit does not contain psoralens.6-9 The tree also produces proteolytic enzymes such as protease, amylase, ficin, triterpenoids, and lipodiastase that enhance its phototoxic effects.8 Exposure to UV light between 320 and 400 nm following contact with these phototoxic components triggers a reaction in the skin over the course of 1 to 3 days.5 The psoralens bind in epidermal cells, cross-link the DNA, and cause cell-membrane destruction, leading to edema and necrosis.10 The delay in symptoms may be attributed to the time needed to synthesize acute-phase reaction proteins such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-1.11 In spring and summer months, an increased concentration of psoralens in the leaves and sap contribute to an increased incidence of phytophotodermatitis.9 Humidity and sweat also increase the percutaneous absorption of psoralens.12,13

Allergens

Fig trees produce a latex protein that can cause cross-reactive hypersensitivity reactions in those allergic to F benjamina latex and rubber latex.6 The latex proteins in fig trees can act as airborne respiratory allergens. Ingestion of figs can produce anaphylactic reactions in those sensitized to rubber latex and F benjamina latex.7 Other plant families associated with phototoxic reactions include Rutaceae (lemon, lime, bitter orange), Apiaceae (formerly Umbelliferae)(carrot, parsnip, parsley, dill, celery, hogweed), and Fabaceae (prairie turnip).

Cutaneous Manifestations

Most cases of fig phytophotodermatitis begin with burning, pain, and/or itching within hours of sunlight exposure in areas of the skin that encountered components of the fig tree, often in a linear pattern. The affected areas become erythematous and edematous with formation of bullae and unilocular vesicles over the course of 1 to 3 days.12,14,15 Lesions may extend beyond the region of contact with the fig tree as they spread across the skin due to sweat or friction, and pain may linger even after the lesions resolve.12,13,16 Adults who handle fig trees (eg, pruning) are susceptible to phototoxic reactions, especially those using chain saws or other mechanisms that result in spray exposure, as the photosensitizing sap permeates the wood and bark of the entire tree.17 Similarly, children who handle fig leaves or sap during outdoor play can develop bullous eruptions. Severe cases have resulted in hospital admission after prolonged exposure.16 Additionally, irritant dermatitis may arise from contact with the trichomes or “hairs” on various parts of the plant.

Patients who use natural remedies containing components of the fig tree without the supervision of a medical provider put themselves at risk for unsafe or unwanted adverse effects, such as phytophotodermatitis.12,15,16,18 An entire family presented with burns after they applied fig leaf extract to the skin prior to tanning outside in the sun.19 A 42-year-old woman acquired a severe burn covering 81% of the body surface after topically applying fig leaf tea to the skin as a tanning agent.20 A subset of patients ingesting or applying fig tree components for conditions such as vitiligo, dermatitis, onychomycosis, and motor retardation developed similar cutaneous reactions.13,14,21,22 Lesions resembling finger marks can raise concerns for potential abuse or neglect in children.22

The differential diagnosis for fig phytophotodermatitis includes sunburn, chemical burns, drug-related photosensitivity, infectious lesions (eg, herpes simplex, bullous impetigo, Lyme disease, superficial lymphangitis), connective tissue disease (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus), contact dermatitis, and nonaccidental trauma.12,15,18 Compared to sunburn, phytophotodermatitis tends to increase in severity over days following exposure and heals with dramatic hyperpigmentation, which also prompts visits to dermatology.12

Treatment

Treatment of fig phytophotodermatitis chiefly is symptomatic, including analgesia, appropriate wound care, and infection prophylaxis. Topical and systemic corticosteroids may aid in the resolution of moderate to severe reactions.15,23,24 Even severe injuries over small areas or mild injuries to a high percentage of the total body surface area may require treatment in a burn unit. Patients should be encouraged to use mineral-based sunscreens on the affected areas to reduce the risk for hyperpigmentation. Individuals who regularly handle fig trees should use contact barriers including gloves and protective clothing (eg, long-sleeved shirts, long pants).

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

- Ikegami H, Nogata H, Hirashima K, et al. Analysis of genetic diversity among European and Asian fig varieties (Ficus carica L.) using ISSR, RAPD, and SSR markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2009;56:201-209.

- Zohary D, Spiegel-Roy P. Beginnings of fruit growing in the Old World. Science. 1975;187:319-327.

- Young R. Young’s Analytical Concordance. Thomas Nelson; 1982.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Bioassay of natural and synthetic furocoumarins (psoralens). J Invest Dermatol. 1959;32:509-518.

- Focke M, Hemmer W, Wöhrl S, et al. Cross-reactivity between Ficus benjamina latex and fig fruit in patients with clinical fig allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:971-977.

- Hemmer W, Focke M, Götz M, et al. Sensitization to Ficus benjamina: relationship to natural rubber latex allergy and identification of foods implicated in the Ficus-fruit syndrome. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:1251-1258.

- Bonamonte D, Foti C, Lionetti N, et al. Photoallergic contact dermatitis to 8-methoxypsoralen in Ficus carica. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:343-348.

- Zaynoun ST, Aftimos BG, Abi Ali L, et al. Ficus carica; isolation and quantification of the photoactive components. Contact Dermatitis. 1984;11:21-25.

- Tessman JW, Isaacs ST, Hearst JE. Photochemistry of the furan-side 8-methoxypsoralen-thymidine monoadduct inside the DNA helix. conversion to diadduct and to pyrone-side monoadduct. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1669-1676.

- Geary P. Burns related to the use of psoralens as a tanning agent. Burns. 1996;22:636-637.

- Redgrave N, Solomon J. Severe phytophotodermatitis from fig sap: a little known phenomenon. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:E238745.

- Ozdamar E, Ozbek S, Akin S. An unusual cause of burn injury: fig leaf decoction used as a remedy for a dermatitis of unknown etiology. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:229-233; discussion 228.

- Berakha GJ, Lefkovits G. Psoralen phototherapy and phototoxicity. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:458-461.

- Papazoglou A, Mantadakis E. Fig tree leaves phytophotodermatitis. J Pediatr. 2021;239:244-245.

- Imen MS, Ahmadabadi A, Tavousi SH, et al. The curious cases of burn by fig tree leaves. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:71-73.

- Rouaiguia-Bouakkaz S, Amira-Guebailia H, Rivière C, et al. Identification and quantification of furanocoumarins in stem bark and wood of eight Algerian varieties of Ficus carica by RP-HPLC-DAD and RP-HPLC-DAD-MS. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8:485-486.

- Oliveira AA, Morais J, Pires O, et al. Fig tree induced phytophotodermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:E233392.

- Bassioukas K, Stergiopoulou C, Hatzis J. Erythrodermic phytophotodermatitis after application of aqueous fig-leaf extract as an artificial suntan promoter and sunbathing. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:94-95.

- Sforza M, Andjelkov K, Zaccheddu R. Severe burn on 81% of body surface after sun tanning. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2013;19:383-384.

- Son JH, Jin H, You HS, et al. Five cases of phytophotodermatitis caused by fig leaves and relevant literature review. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:86-90.

- Abali AE, Aka M, Aydogan C, et al. Burns or phytophotodermatitis, abuse or neglect: confusing aspects of skin lesions caused by the superstitious use of fig leaves. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:E309-E312.

- Picard C, Morice C, Moreau A, et al. Phytophotodermatitis in children: a difficult diagnosis mimicking other dermatitis. 2017;5:1-3.

- Enjolras O, Soupre V, Picard A. Uncommon benign infantile vascular tumors. Adv Dermatol. 2008;24:105-124.

Practice Points

- Exposure to the components of the common fig tree (Ficus carica) can induce phytophotodermatitis.

- Notable postinflammatory hyperpigmentation typically occurs in the healing stage of fig phytophotodermatitis.

Asymptomatic Erythematous Plaque in an Outdoorsman

The Diagnosis: Erythema Migrans

The patient was clinically diagnosed with erythema migrans. He did not recall a tick bite but spent a lot of time outdoors. He was treated with 10 days of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with complete resolution of the rash.

Lyme disease is a spirochete infection caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species complex and transmitted by the Ixodidae tick family. It is the most common tick-borne disease in the United States and mostly is reported in the northeastern and upper midwestern states during the warmer seasons, but it is prevalent worldwide. In geographic areas where Lyme disease is common, the incidence is approximately 40 cases per 100,000 individuals.1 Our patient resided in coastal South Carolina. Lyme disease is more commonly reported in White individuals. The skin lesions may be more difficult to discern and diagnose in patients with darker skin types, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.2,3

Patients may be diagnosed with early localized, early disseminated, or late Lyme disease. Erythema migrans is the early localized form of the disease and is classically described as an erythematous targetlike plaque with raised borders arising at the site of the tick bite 1 to 2 weeks later.4 However, many patients simply have a homogeneous erythematous plaque with raised advancing borders ranging in size from 5 to 68 cm.5 In a 2022 study of 69 patients with suspected Lyme disease, only 35 (50.7%) were determined to truly have acute Lyme disease.6 Of them, only 2 (5.7%) had the classic ringwithin- a-ring pattern. Most plaques were uniform, pink, oval-shaped lesions with well-demarcated borders.6

The rash may present with a burning sensation, or patients may experience no symptoms at all, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and progression to late disease. Patients may develop malaise, fever, headache, body aches, or joint pain. Early disseminated disease manifests similarly. Patients with disseminated disease also may develop more serious complications, including lymphadenopathy; cranial nerve palsies; ocular involvement; meningitis; or cardiac abnormalities such as myocarditis, pericarditis, or arrhythmia. Late disease most often causes arthritis of the large joints, though it also can have cardiac or neurologic manifestations. Some patients with chronic disease—the majority of whom were diagnosed in Europe—may develop acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans with edematous blue-red plaques that become atrophic and hyperpigmented fibrotic plaques over the course of years.

Allergic contact dermatitis to a plant more likely would cause itchy or painful, oozy, weepy, vesicular lesions arranged in a linear pattern. A dermatophyte infection likely would cause a scaly eruption. Although our patient presented with a sharply demarcated, raised, erythematous lesion, the distribution did not follow normal clothing lines and would be unusual for a photosensitive drug eruption. Cellulitis likely would be associated with tenderness or warmth to the touch. Finally, southern tick-associated rash illness, which is associated with Amblyomma americanum (lone star tick) bites, may appear with a similar rash but few systemic symptoms. It also can be treated with tetracycline antibiotics.7