User login

The Hospitalist Triage Role for Reducing Admission Delays: Impacts on Throughput, Quality, Interprofessional Practice, and Clinician Experience of Care

From the Division of Hospital Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Drs. Bartlett, Pizanis, Angeli, Lacy, and Rogers), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Dr. Scott), and University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque (Ms. Baca).

ABSTRACT

Background: Emergency department (ED) crowding is associated with deleterious consequences for patient care and throughput. Admission delays worsen ED crowding. Time to admission (TTA)—the time between an ED admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders—can be shortened through implementation of a triage hospitalist role. Limited research is available highlighting the impact of triage hospitalists on throughput, care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care.

Methods: A triage hospitalist role was piloted and implemented. Run charts were interpreted using accepted rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions. Statistical analysis was applied to interprofessional practice and clinician experience-of-care survey results.

Results: Following implementation, TTA decreased from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Emergency department crowding increased from baseline. The reduction in TTA was associated with decreased time from ED arrival to IM admission request, no change in critical care transfers during the initial 24 hours, and increased admissions to inpatient status. Additionally, decreased TTA was associated with no change in referring hospital transfer rates and no change in hospital medicine length of stay. Interprofessional practice attitudes improved among ED clinicians but not IM clinicians. Clinician experience-of-care results were mixed.

Conclusion: A triage hospitalist role is an effective approach for mitigating admission delays, with no evident adverse clinical consequences. A triage hospitalist alone was incapable of resolving ED crowding issues without a complementary focus on downstream bottlenecks.

Keywords: triage hospitalist, admission delay, quality improvement.

Excess time to admission (TTA), defined as the time between an emergency department (ED) admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders, contributes to ED crowding, which is associated with deleterious impacts on patient care and throughput. Prior research has correlated ED crowding with an increase in length of stay (LOS)1-3 and total inpatient cost,1 as well as increased inpatient mortality, higher left-without-being-seen rates,4 delays in clinically meaningful care,5,6 and poor patient and clinician satisfaction.6,7 While various solutions have been proposed to alleviate ED crowding,8 excess TTA is one aspect that IM can directly address.

Like many institutions, ours is challenged by ED crowding. Time to admission is a known bottleneck. Underlying factors that contribute to excess TTA include varied admission request volumes in relation to fixed admitting capacity; learner-focused admitting processes; and unreliable strategies for determining whether patients are eligible for ED observation, transfer to an alternative facility, or admission to an alternative primary service.

To address excess TTA, we piloted then implemented a triage hospitalist role, envisioned as responsible for evaluating ED admission requests to IM, making timely determinations of admission appropriateness, and distributing patients to admitting teams. This intervention was selected because of its strengths, including the ability to standardize admission processes, improve the proximity of clinical decision-makers to patient care to reduce delays, and decrease hierarchical imbalances experienced by trainees, and also because the institution expressed a willingness to mitigate its primary weakness (ie, ongoing financial support for sustainability) should it prove successful.

Previously, a triage hospitalist has been defined as “a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting.”9 Velásquez et al surveyed 10 academic medical centers and identified significant heterogeneity in the roles and responsibilities of a triage hospitalist.9 Limited research addresses the impact of this role on throughput. One report described the volume and source of requests evaluated by a triage hospitalist and the frequency with which the triage hospitalists’ assessment of admission appropriateness aligned with that of the referring clinicians.10 No prior research is available demonstrating the impact of this role on care quality, interprofessional practice, or clinician experience of care. This article is intended to address these gaps in the literature.

Methods

Setting

The University of New Mexico Hospital has 537 beds and is the only level-1 trauma and academic medical center in the state. On average, approximately 8000 patients register to be seen in the ED per month. Roughly 600 are admitted to IM per month. This study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, with low patient volumes in April 2020, overcapacity census starting in May 2020, and markedly high patient volumes in May/June 2020 and November/December 2020. All authors participated in project development, implementation, and analysis.

Preintervention IM Admission Process

When requesting IM admission, ED clinicians (resident, advanced practice provider [APP], or attending) contacted the IM triage person (typically an IM resident physician) by phone or in person. The IM triage person would then assess whether the patient needed critical care consultation (a unique and separate admission pathway), was eligible for ED observation or transfer to an outside hospital, or was clinically appropriate for IM subacute and floor admission. Pending admissions were evaluated in order of severity of illness or based on wait time if severity of illness was equal. Transfers from the intensive care unit (ICU) and referring hospitals were prioritized. Between 7:00

Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Key changes made during the pilot included scheduling an IM attending to serve as triage hospitalist for all IM admission requests from the ED between 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Data collected included request type (new vs overflow from night) and patient details (name, medical record number). Two time points were recorded: when the EDAR order was entered and when admission orders were entered. Process indicators, including whether the EDAR order was entered and the final triage decision (eg, discharge, IM), were recorded. General feedback was requested at the end of each shift.

Phased Implementation of Triage Hospitalist Role

Triage hospitalist role implementation was approved following the pilot, with additional salary support funded by the institution. A new performance measure (time from admission request to admission order, self-identified goal < 3 hours) was approved by all parties.

In January 2020, the role was scheduled from 7:00

In March 2020, to create a single communication pathway while simultaneously hardwiring our measurement strategy, the EDAR order was modified such that it would automatically prompt a 1-way communication to the triage hospitalist using the institution’s secure messaging software. The message included patient name, medical record number, location, ED attending, reason for admission, and consultation priority, as well as 2 questions prompting ED clinicians to reflect on the most common reasons for the triage hospitalist to recommend against IM admission (eligible for admission to other primary service, transfer to alternative hospital).

In July 2020, the triage hospitalist role was scheduled 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to meet an institutional request. The schedule was divided into a daytime 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Role

The primary outcome measure was TTA, defined as the time between EDAR (operationalized using EDAR order timestamp) and IM admission decision (operationalized using inpatient bed request order timestamp). Additional outcome measures included the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Electronic Clinical Quality Measure ED-2 (eCQM ED-2), defined as the median time from admit decision to departure from the ED for patients admitted to inpatient status.

Process measures included time between patient arrival to the ED (operationalized using ED registration timestamp) and EDAR and percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order. Balancing measures included time between bed request order (referred to as the IM admission order) and subsequent admission orders. While the IM admission order prompts an inpatient clinical encounter and inpatient bed assignment, subsequent admission orders are necessary for clinical care. Additional balancing measures included ICU transfer rate within the first 24 hours, referring facility transfer frequency to IM (an indicator of access for patients at outside hospitals), average hospital medicine LOS (operationalized using ED registration timestamp to discharge timestamp), and admission status (inpatient vs observation).

An anonymous preintervention (December 2019) and postintervention (August 2020) survey focusing on interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care was used to obtain feedback from ED and IM attendings, APPs, and trainees. Emergency department clinicians were asked questions pertaining to their IM colleagues and vice versa. A Likert 5-point scale was used to respond.

Data Analysis

The preintervention period was June 1, 2019, to October 31, 2019; the pilot period was November 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019; the staged implementation period was January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020; and the postintervention period was July 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020. Run charts for outcome, process, and balancing measures were interpreted using rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions.11 Statistical analysis using a t test assuming unequal variances with P < . 05 to indicate statistical significance was applied to experience-of-care results. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Triage Hospitalist Pilot Time Period

Seventy-four entries were recorded, 56 (75.7%) reflecting new admission requests. Average time between EDAR order and IM admission order was 40 minutes. The EDAR order was entered into the EMR without prompting in 22 (29.7%) cases. In 56 (75.7%) cases, the final triage decision was IM admission. Other dispositions included 3 discharges, 4 transfers, 3 alternative primary service admissions, 1 ED observation, and 7 triage deferrals pending additional workup or stabilization.

Feedback substantiated several benefits, including improved coordination among IM, ED, and consultant clinicians, as well as early admission of seriously ill patients. Feedback also confirmed several expected challenges, including evidence of communication lapses, difficulty with transfer coordinator integration, difficulty hardwiring elements of the verbal and bedside handoff, and perceived high cognitive load for the triage hospitalist. Several unexpected issues included whether ED APPs can request admission independently and how reconsultation is expected to occur if admission is initially deferred.

Triage Hospitalist Implementation Time Period

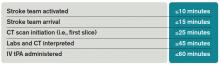

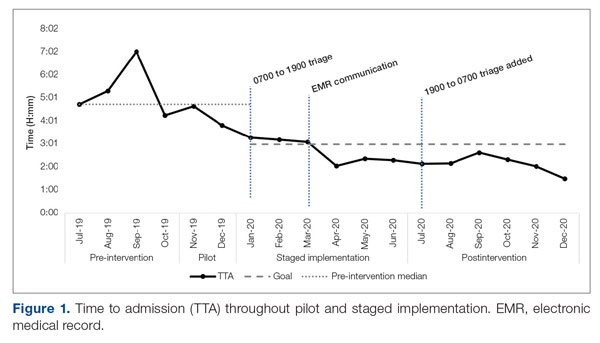

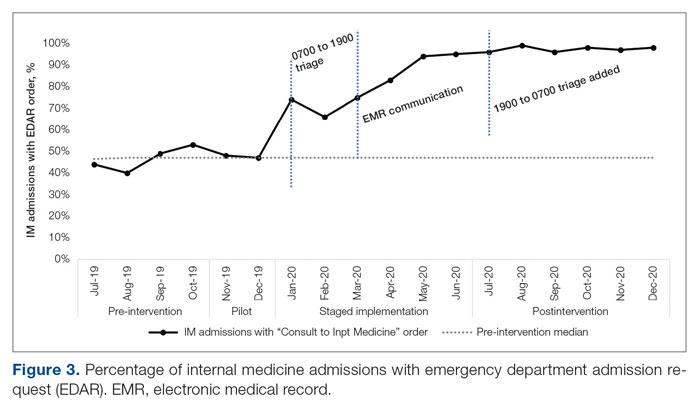

Time to admission decreased from a baseline pre-pilot average of 5 hours 19 minutes (median, 4 hours 45 minutes) to a postintervention average of 2 hours 8 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention (Figure 1).

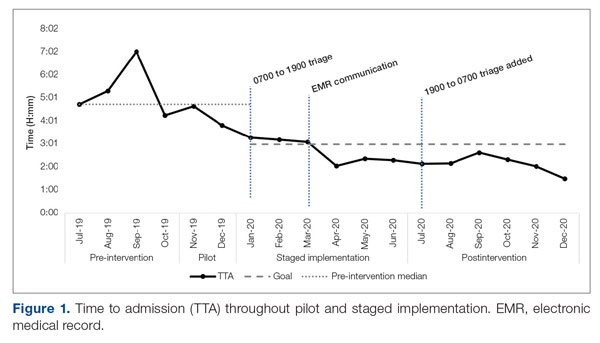

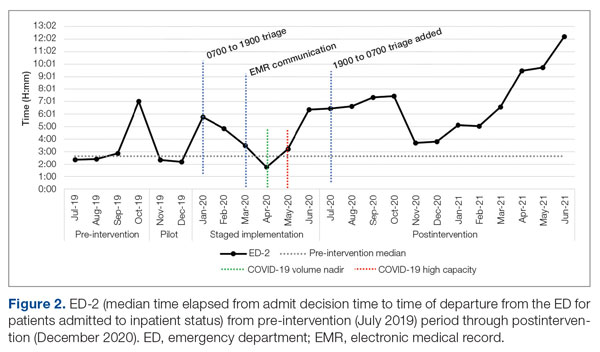

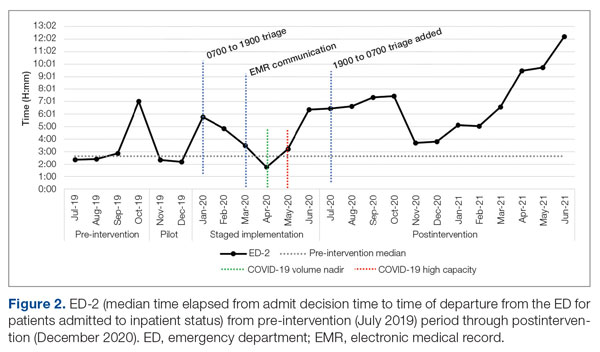

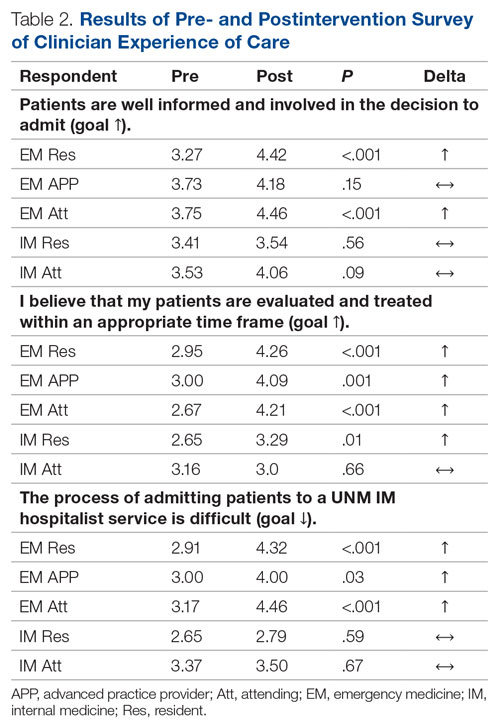

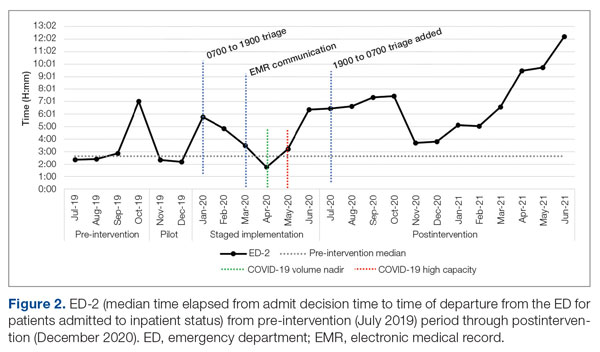

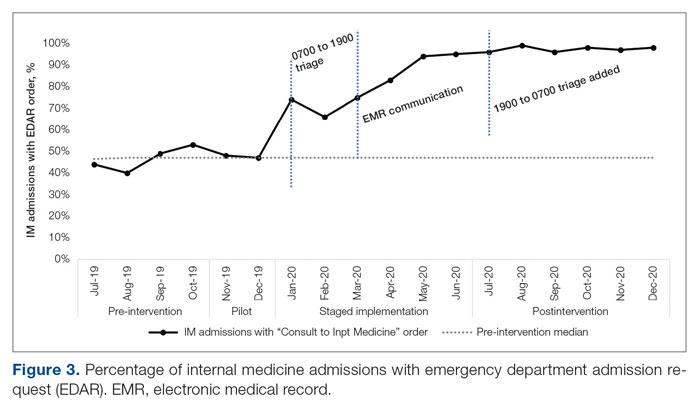

ED-2 increased from a baseline average of 3 hours 40 minutes (median, 2 hours 39 minutes), with a statistically significant upward shift starting in May 2020 (Figure 2). Time between patient arrival to the ED and EDAR order decreased from a baseline average of 8 hours 47 minutes (median, 8 hours 37 minutes) to a postintervention average of 5 hours 57 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention. Percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order increased from a baseline average of 47% (median, 47%) to 97%, with a statistically significant upward shift starting in January 2020 (Figure 3).

There was no change in observed average time between IM admission order and subsequent admission orders pre and post intervention (16 minutes vs 18 minutes). However, there was a statistically significant shift up to an average of 40 minutes from January through June 2020, which then resolved. The percentage of patients transferred to the ICU within 24 hours of admission to IM did not change (1.1% pre vs 1.4% post intervention). Frequency of patients transferred in from a referring facility also did not change (26/month vs 22/month). Average hospital medicine LOS did not change to a statistically significant degree (6.48 days vs 6.62 days). The percentage of inpatient admissions relative to short stays increased from a baseline of 74.0% (median, 73.6%) to a postintervention average of 82.4%, with a statistically significant shift upward starting March 2020.

Regarding interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care, 122 of 309 preintervention surveys (39.5% response rate) and 98 of 309 postintervention surveys (31.7% response rate) were completed. Pre- and postintervention responses were not linked.

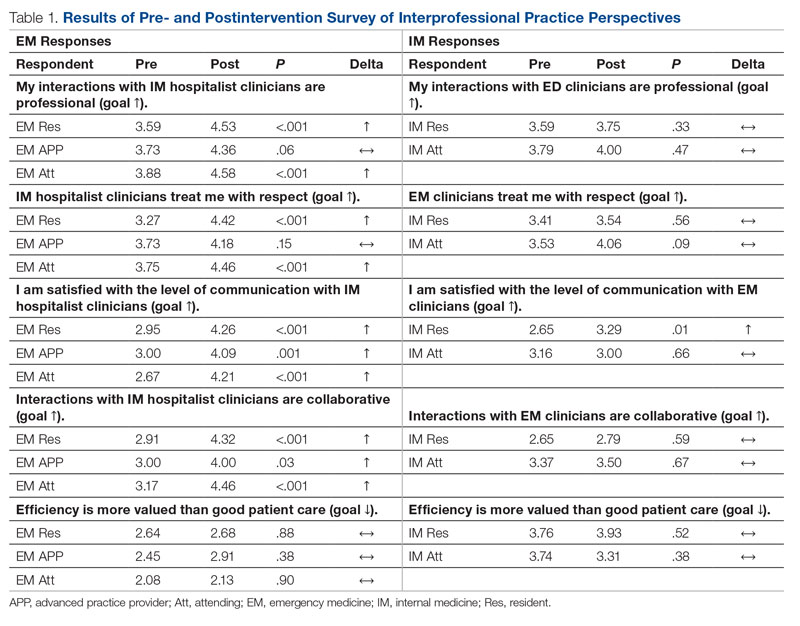

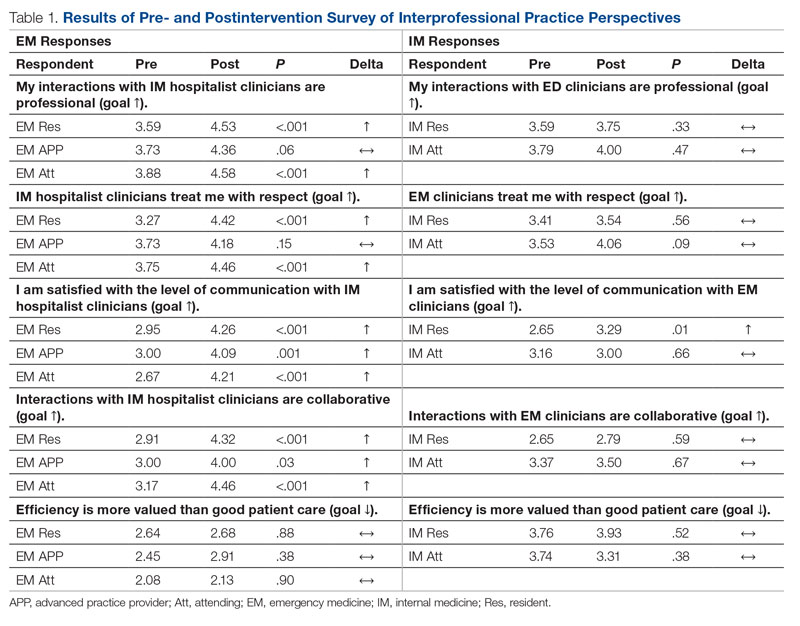

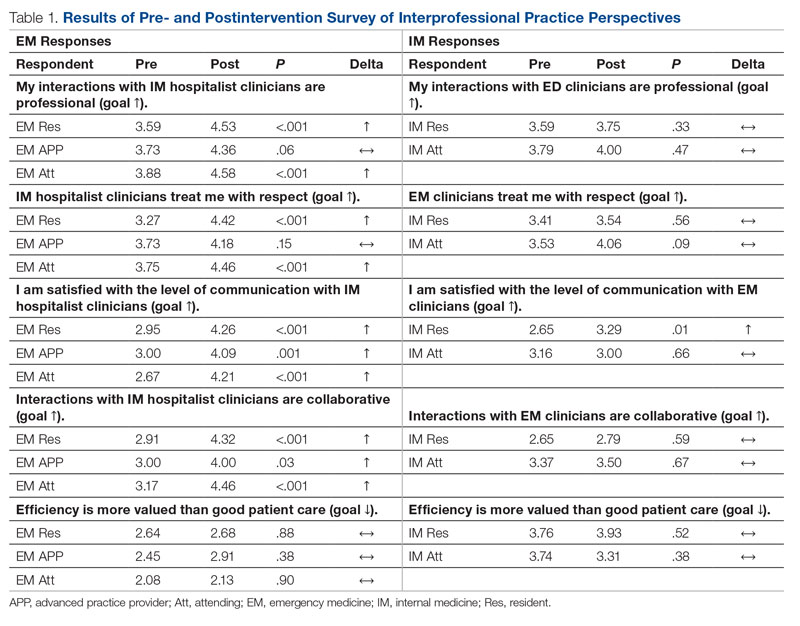

Regarding interprofessional practice, EM residents and EM attendings experienced statistically significant improvements in all interprofessional practice domains (Table 1). Emergency medicine APPs experienced statistically significant improvements post intervention with “I am satisfied with the level of communication with IM hospitalist clinicians” and “Interactions

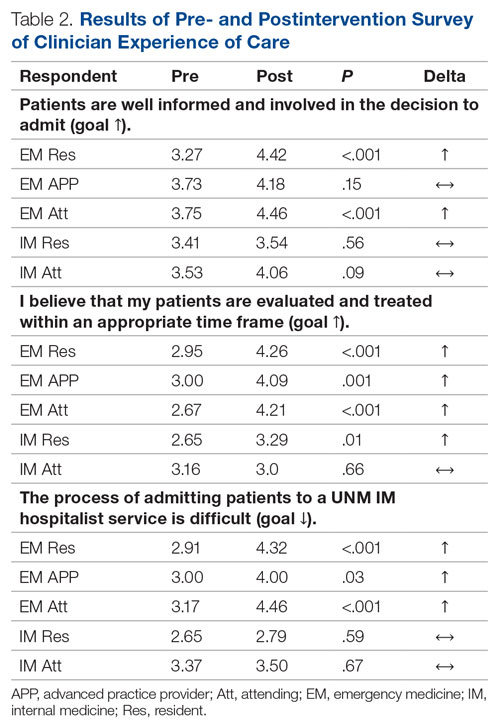

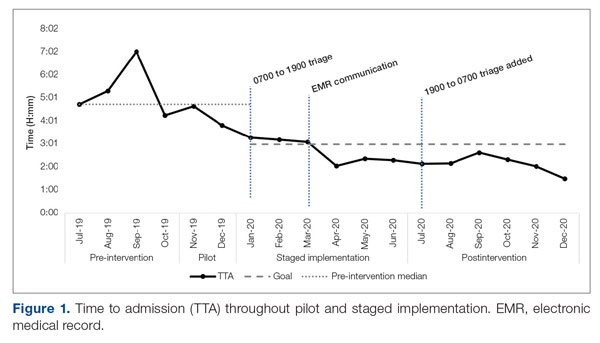

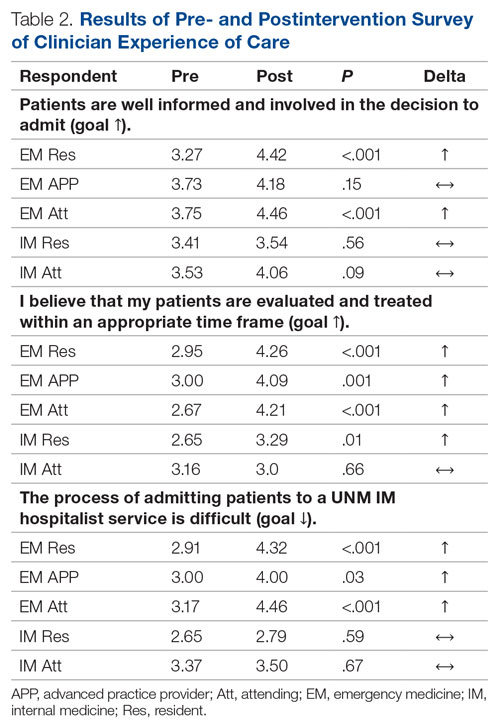

For clinician experience of care, EM residents (P < .001) and attendings (P < .001) experienced statistically significant improvements in “Patients are well informed and involved in the decision to admit,” whereas IM residents and attendings, as well as EM APPs, experienced nonstatistically significant improvements (Table 2). All groups except IM attendings experienced a statistically significant improvement (IM resident P = .011, EM resident P < .001, EM APP P = .001, EM attending P < .001) in “I believe that my patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Internal medicine attendings felt that this indicator worsened to a nonstatistically significant degree. Post intervention, EM groups experienced a statistically significant worsening in “The process of admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult,” while IM groups experienced a nonstatistically significant worsening.

Discussion

Implementation of the triage hospitalist role led to a significant reduction in average TTA, from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Performance has been sustained at 1 hour 42 minutes on average over the past 6 months. The triage hospitalist was successful at reducing TTA because of their focus on evaluating new admission and transfer requests, deferring other admission responsibilities to on-call admitting teams. Early admission led to no increase in ICU transfers or hospitalist LOS. To ensure that earlier admission reflected improved timeliness of care and that new sources of delay were not being created, we measured the time between IM admission and subsequent admission orders. A statistically significant increase to 40 minutes from January through June 2020 was attributable to the hospitalist acclimating to their new role and the need to standardize workflow. This delay subsequently resolved. An additional benefit of the triage hospitalist was an increase in the proportion of inpatient admissions compared with short stays.

ED-2, an indicator of ED crowding, increased from 3 hours 40 minutes, with a statistically significant upward shift starting May 2020. Increasing ED-2 associated with the triage hospitalist role makes intuitive sense. Patients are admitted 2 hours 40 minutes earlier in their hospital course while downstream bottlenecks preventing patient movement to an inpatient bed remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic complicates interpretation of ED-2 because the measure reflects institutional capacity to match demand for inpatient beds. Fewer ED registrations and lower hospital medicine census (and resulting inpatient bed availability) in April 2020 during the first COVID-19 surge coincided with an ED-2 nadir of 1 hour 46 minutes. The statistically significant upward shift from May onward reflects ongoing and unprecedented patient volumes. It remains difficult to tease apart the presumed lesser contribution of the triage hospitalist role and presumed larger contribution of high patient volumes on ED-2 increases.

An important complementary change was linkage between the EDAR order and our secure messaging software, creating a single source of admission and transfer requests, prompting early ED clinician consideration of factors that could result in alternative disposition, and ensuring a sustainable data source for TTA. The order did not replace direct communication and included guidance for how triage hospitalists should connect with their ED colleagues. Percentage of IM admissions with the EDAR order increased to 97%. Fallouts are attributed to admissions from non-ED sources (eg, referring facility, endoscopy suite transfers). This communication strategy has been expanded as the primary mechanism of initiating consultation requests between IM and all consulting services.

This intervention was successful from the perspective of ED clinicians. Improvements can be attributed to the simplified admission process, timely patient assessment, a perception that patients are better informed of the decision to admit, and the ability to communicate with the triage hospitalist. Emergency medicine APPs may not have experienced similar improvements due to ongoing perceptions of a hierarchical imbalance. Unfortunately, the small but not statistically significant worsening perspective among ED clinicians that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” and the statistically significant worsening perspective that “admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult” may be due to the triage hospitalist responsibility for identifying the roughly 25% of patients who are safe for an alternative disposition.

Internal medicine clinicians experienced no significant changes in attitudes. Underlying causes are likely multifactorial and a focus of ongoing work. Internal medicine residents experienced statistically significant improvements for “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians” and nonstatistically significant improvements for the other 3 domains, likely because the intervention enabled them to focus on clinical care rather than the administrative tasks and decision-making complexities inherent to the IM admission process. Internal medicine attendings reported a nonstatistically significant worsening in “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians,” which is possibly attributable to challenges connecting with ED attendings after being notified that a new admission is pending. Unfortunately, bedside handoff was not hardwired and is done sporadically. Independent of the data, we believe that the triage hospitalist role has facilitated closer ED-IM relationships by aligning clinical priorities, standardizing processes, improving communication, and reducing sources of hierarchical imbalance and conflict. We expected IM attendings and residents to experience some degree of resolution of the perception that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” because of the addition of a dedicated triage role. Our data also suggest that IM attendings are less likely to agree that “patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Both concerns may be linked to the triage hospitalist facing multiple admission and transfer sources with variable arrival rates and variable patient complexity, resulting in high cognitive load and the perception that individual tasks are not completed to the best of their abilities.

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of the triage hospitalist role on throughput, clinical care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care. In the cross-sectional survey of 10 academic medical centers, 8 had defined triage roles filled by IM attendings, while the remainder had IM attendings supervising trainees.9 A complete picture of the prevalence and varying approaches of triage hospitalists models is unknown. Howell et al12 reported on an approach that reduced admission delays without a resulting increase in mortality or LOS. Our approach differed in several ways, with greater involvement of the triage hospitalist in determining a final admission decision, incorporation of EMR communication, and presence of existing throughput challenges preventing patients from moving seamlessly to an inpatient unit.

Conclusion

We believe this effort was successful for several reasons, including adherence to quality improvement best practices, such as engagement of stakeholders early on, the use of data to inform decision-making, the application of technology to hardwire process, and alignment with institutional priorities. Spread of this intervention will be limited by the financial investment required to start and maintain a triage hospitalist role. A primary limitation of this study is the confounding effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on our analysis. Next steps include identification of clinicians wishing to specialize in triage and expanding triage to include non-IM primary services. Additional research to optimize the triage hospitalist experience of care, as well as to measure improvements in patient-centered outcomes, is necessary.

Corresponding author: Christopher Bartlett, MD, MPH; MSC10 5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; CSBartlett@salud.unm.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Huang Q, Thind A, Dreyer JF, et al. The impact of delays to admission from the emergency department on inpatient outcomes. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10:16. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-10-16

2. Liew D, Liew D, Kennedy MP. Emergency department length of stay independently predicts excess inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2003;179:524-526. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05676.x

3. Richardson DB. The access-block effect: relationship between delay to reaching an inpatient bed and inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2002;177:492-495. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04917.x

4. Polevoi SK, Quinn JV, Kramer KR. Factors associated with patients who leave without being seen. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:232-236. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.029

5. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x

6. Vieth TL, Rhodes KV. The effect of crowding on access and quality in an academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:787-794. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.026

7. Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: the impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50:327-340; discussion 341-342.

8. Emergency Department Crowding: High Impact Solutions. American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Medicine Practice Committee. 2016. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/crowding/empc_crowding-ip_092016.pdf

9. Velásquez ST, Wang ES, White AW, et al. Hospitalists as triagists: description of the triagist role across academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:87-90. doi:10.12788/jhm.3327

10. Amick A, Bann M. Characterizing the role of the “triagist”: reasons for triage discordance and impact on disposition. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2177-2179. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05887-y

11. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning for variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037895

12. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x

From the Division of Hospital Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Drs. Bartlett, Pizanis, Angeli, Lacy, and Rogers), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Dr. Scott), and University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque (Ms. Baca).

ABSTRACT

Background: Emergency department (ED) crowding is associated with deleterious consequences for patient care and throughput. Admission delays worsen ED crowding. Time to admission (TTA)—the time between an ED admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders—can be shortened through implementation of a triage hospitalist role. Limited research is available highlighting the impact of triage hospitalists on throughput, care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care.

Methods: A triage hospitalist role was piloted and implemented. Run charts were interpreted using accepted rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions. Statistical analysis was applied to interprofessional practice and clinician experience-of-care survey results.

Results: Following implementation, TTA decreased from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Emergency department crowding increased from baseline. The reduction in TTA was associated with decreased time from ED arrival to IM admission request, no change in critical care transfers during the initial 24 hours, and increased admissions to inpatient status. Additionally, decreased TTA was associated with no change in referring hospital transfer rates and no change in hospital medicine length of stay. Interprofessional practice attitudes improved among ED clinicians but not IM clinicians. Clinician experience-of-care results were mixed.

Conclusion: A triage hospitalist role is an effective approach for mitigating admission delays, with no evident adverse clinical consequences. A triage hospitalist alone was incapable of resolving ED crowding issues without a complementary focus on downstream bottlenecks.

Keywords: triage hospitalist, admission delay, quality improvement.

Excess time to admission (TTA), defined as the time between an emergency department (ED) admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders, contributes to ED crowding, which is associated with deleterious impacts on patient care and throughput. Prior research has correlated ED crowding with an increase in length of stay (LOS)1-3 and total inpatient cost,1 as well as increased inpatient mortality, higher left-without-being-seen rates,4 delays in clinically meaningful care,5,6 and poor patient and clinician satisfaction.6,7 While various solutions have been proposed to alleviate ED crowding,8 excess TTA is one aspect that IM can directly address.

Like many institutions, ours is challenged by ED crowding. Time to admission is a known bottleneck. Underlying factors that contribute to excess TTA include varied admission request volumes in relation to fixed admitting capacity; learner-focused admitting processes; and unreliable strategies for determining whether patients are eligible for ED observation, transfer to an alternative facility, or admission to an alternative primary service.

To address excess TTA, we piloted then implemented a triage hospitalist role, envisioned as responsible for evaluating ED admission requests to IM, making timely determinations of admission appropriateness, and distributing patients to admitting teams. This intervention was selected because of its strengths, including the ability to standardize admission processes, improve the proximity of clinical decision-makers to patient care to reduce delays, and decrease hierarchical imbalances experienced by trainees, and also because the institution expressed a willingness to mitigate its primary weakness (ie, ongoing financial support for sustainability) should it prove successful.

Previously, a triage hospitalist has been defined as “a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting.”9 Velásquez et al surveyed 10 academic medical centers and identified significant heterogeneity in the roles and responsibilities of a triage hospitalist.9 Limited research addresses the impact of this role on throughput. One report described the volume and source of requests evaluated by a triage hospitalist and the frequency with which the triage hospitalists’ assessment of admission appropriateness aligned with that of the referring clinicians.10 No prior research is available demonstrating the impact of this role on care quality, interprofessional practice, or clinician experience of care. This article is intended to address these gaps in the literature.

Methods

Setting

The University of New Mexico Hospital has 537 beds and is the only level-1 trauma and academic medical center in the state. On average, approximately 8000 patients register to be seen in the ED per month. Roughly 600 are admitted to IM per month. This study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, with low patient volumes in April 2020, overcapacity census starting in May 2020, and markedly high patient volumes in May/June 2020 and November/December 2020. All authors participated in project development, implementation, and analysis.

Preintervention IM Admission Process

When requesting IM admission, ED clinicians (resident, advanced practice provider [APP], or attending) contacted the IM triage person (typically an IM resident physician) by phone or in person. The IM triage person would then assess whether the patient needed critical care consultation (a unique and separate admission pathway), was eligible for ED observation or transfer to an outside hospital, or was clinically appropriate for IM subacute and floor admission. Pending admissions were evaluated in order of severity of illness or based on wait time if severity of illness was equal. Transfers from the intensive care unit (ICU) and referring hospitals were prioritized. Between 7:00

Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Key changes made during the pilot included scheduling an IM attending to serve as triage hospitalist for all IM admission requests from the ED between 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Data collected included request type (new vs overflow from night) and patient details (name, medical record number). Two time points were recorded: when the EDAR order was entered and when admission orders were entered. Process indicators, including whether the EDAR order was entered and the final triage decision (eg, discharge, IM), were recorded. General feedback was requested at the end of each shift.

Phased Implementation of Triage Hospitalist Role

Triage hospitalist role implementation was approved following the pilot, with additional salary support funded by the institution. A new performance measure (time from admission request to admission order, self-identified goal < 3 hours) was approved by all parties.

In January 2020, the role was scheduled from 7:00

In March 2020, to create a single communication pathway while simultaneously hardwiring our measurement strategy, the EDAR order was modified such that it would automatically prompt a 1-way communication to the triage hospitalist using the institution’s secure messaging software. The message included patient name, medical record number, location, ED attending, reason for admission, and consultation priority, as well as 2 questions prompting ED clinicians to reflect on the most common reasons for the triage hospitalist to recommend against IM admission (eligible for admission to other primary service, transfer to alternative hospital).

In July 2020, the triage hospitalist role was scheduled 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to meet an institutional request. The schedule was divided into a daytime 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Role

The primary outcome measure was TTA, defined as the time between EDAR (operationalized using EDAR order timestamp) and IM admission decision (operationalized using inpatient bed request order timestamp). Additional outcome measures included the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Electronic Clinical Quality Measure ED-2 (eCQM ED-2), defined as the median time from admit decision to departure from the ED for patients admitted to inpatient status.

Process measures included time between patient arrival to the ED (operationalized using ED registration timestamp) and EDAR and percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order. Balancing measures included time between bed request order (referred to as the IM admission order) and subsequent admission orders. While the IM admission order prompts an inpatient clinical encounter and inpatient bed assignment, subsequent admission orders are necessary for clinical care. Additional balancing measures included ICU transfer rate within the first 24 hours, referring facility transfer frequency to IM (an indicator of access for patients at outside hospitals), average hospital medicine LOS (operationalized using ED registration timestamp to discharge timestamp), and admission status (inpatient vs observation).

An anonymous preintervention (December 2019) and postintervention (August 2020) survey focusing on interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care was used to obtain feedback from ED and IM attendings, APPs, and trainees. Emergency department clinicians were asked questions pertaining to their IM colleagues and vice versa. A Likert 5-point scale was used to respond.

Data Analysis

The preintervention period was June 1, 2019, to October 31, 2019; the pilot period was November 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019; the staged implementation period was January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020; and the postintervention period was July 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020. Run charts for outcome, process, and balancing measures were interpreted using rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions.11 Statistical analysis using a t test assuming unequal variances with P < . 05 to indicate statistical significance was applied to experience-of-care results. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Triage Hospitalist Pilot Time Period

Seventy-four entries were recorded, 56 (75.7%) reflecting new admission requests. Average time between EDAR order and IM admission order was 40 minutes. The EDAR order was entered into the EMR without prompting in 22 (29.7%) cases. In 56 (75.7%) cases, the final triage decision was IM admission. Other dispositions included 3 discharges, 4 transfers, 3 alternative primary service admissions, 1 ED observation, and 7 triage deferrals pending additional workup or stabilization.

Feedback substantiated several benefits, including improved coordination among IM, ED, and consultant clinicians, as well as early admission of seriously ill patients. Feedback also confirmed several expected challenges, including evidence of communication lapses, difficulty with transfer coordinator integration, difficulty hardwiring elements of the verbal and bedside handoff, and perceived high cognitive load for the triage hospitalist. Several unexpected issues included whether ED APPs can request admission independently and how reconsultation is expected to occur if admission is initially deferred.

Triage Hospitalist Implementation Time Period

Time to admission decreased from a baseline pre-pilot average of 5 hours 19 minutes (median, 4 hours 45 minutes) to a postintervention average of 2 hours 8 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention (Figure 1).

ED-2 increased from a baseline average of 3 hours 40 minutes (median, 2 hours 39 minutes), with a statistically significant upward shift starting in May 2020 (Figure 2). Time between patient arrival to the ED and EDAR order decreased from a baseline average of 8 hours 47 minutes (median, 8 hours 37 minutes) to a postintervention average of 5 hours 57 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention. Percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order increased from a baseline average of 47% (median, 47%) to 97%, with a statistically significant upward shift starting in January 2020 (Figure 3).

There was no change in observed average time between IM admission order and subsequent admission orders pre and post intervention (16 minutes vs 18 minutes). However, there was a statistically significant shift up to an average of 40 minutes from January through June 2020, which then resolved. The percentage of patients transferred to the ICU within 24 hours of admission to IM did not change (1.1% pre vs 1.4% post intervention). Frequency of patients transferred in from a referring facility also did not change (26/month vs 22/month). Average hospital medicine LOS did not change to a statistically significant degree (6.48 days vs 6.62 days). The percentage of inpatient admissions relative to short stays increased from a baseline of 74.0% (median, 73.6%) to a postintervention average of 82.4%, with a statistically significant shift upward starting March 2020.

Regarding interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care, 122 of 309 preintervention surveys (39.5% response rate) and 98 of 309 postintervention surveys (31.7% response rate) were completed. Pre- and postintervention responses were not linked.

Regarding interprofessional practice, EM residents and EM attendings experienced statistically significant improvements in all interprofessional practice domains (Table 1). Emergency medicine APPs experienced statistically significant improvements post intervention with “I am satisfied with the level of communication with IM hospitalist clinicians” and “Interactions

For clinician experience of care, EM residents (P < .001) and attendings (P < .001) experienced statistically significant improvements in “Patients are well informed and involved in the decision to admit,” whereas IM residents and attendings, as well as EM APPs, experienced nonstatistically significant improvements (Table 2). All groups except IM attendings experienced a statistically significant improvement (IM resident P = .011, EM resident P < .001, EM APP P = .001, EM attending P < .001) in “I believe that my patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Internal medicine attendings felt that this indicator worsened to a nonstatistically significant degree. Post intervention, EM groups experienced a statistically significant worsening in “The process of admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult,” while IM groups experienced a nonstatistically significant worsening.

Discussion

Implementation of the triage hospitalist role led to a significant reduction in average TTA, from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Performance has been sustained at 1 hour 42 minutes on average over the past 6 months. The triage hospitalist was successful at reducing TTA because of their focus on evaluating new admission and transfer requests, deferring other admission responsibilities to on-call admitting teams. Early admission led to no increase in ICU transfers or hospitalist LOS. To ensure that earlier admission reflected improved timeliness of care and that new sources of delay were not being created, we measured the time between IM admission and subsequent admission orders. A statistically significant increase to 40 minutes from January through June 2020 was attributable to the hospitalist acclimating to their new role and the need to standardize workflow. This delay subsequently resolved. An additional benefit of the triage hospitalist was an increase in the proportion of inpatient admissions compared with short stays.

ED-2, an indicator of ED crowding, increased from 3 hours 40 minutes, with a statistically significant upward shift starting May 2020. Increasing ED-2 associated with the triage hospitalist role makes intuitive sense. Patients are admitted 2 hours 40 minutes earlier in their hospital course while downstream bottlenecks preventing patient movement to an inpatient bed remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic complicates interpretation of ED-2 because the measure reflects institutional capacity to match demand for inpatient beds. Fewer ED registrations and lower hospital medicine census (and resulting inpatient bed availability) in April 2020 during the first COVID-19 surge coincided with an ED-2 nadir of 1 hour 46 minutes. The statistically significant upward shift from May onward reflects ongoing and unprecedented patient volumes. It remains difficult to tease apart the presumed lesser contribution of the triage hospitalist role and presumed larger contribution of high patient volumes on ED-2 increases.

An important complementary change was linkage between the EDAR order and our secure messaging software, creating a single source of admission and transfer requests, prompting early ED clinician consideration of factors that could result in alternative disposition, and ensuring a sustainable data source for TTA. The order did not replace direct communication and included guidance for how triage hospitalists should connect with their ED colleagues. Percentage of IM admissions with the EDAR order increased to 97%. Fallouts are attributed to admissions from non-ED sources (eg, referring facility, endoscopy suite transfers). This communication strategy has been expanded as the primary mechanism of initiating consultation requests between IM and all consulting services.

This intervention was successful from the perspective of ED clinicians. Improvements can be attributed to the simplified admission process, timely patient assessment, a perception that patients are better informed of the decision to admit, and the ability to communicate with the triage hospitalist. Emergency medicine APPs may not have experienced similar improvements due to ongoing perceptions of a hierarchical imbalance. Unfortunately, the small but not statistically significant worsening perspective among ED clinicians that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” and the statistically significant worsening perspective that “admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult” may be due to the triage hospitalist responsibility for identifying the roughly 25% of patients who are safe for an alternative disposition.

Internal medicine clinicians experienced no significant changes in attitudes. Underlying causes are likely multifactorial and a focus of ongoing work. Internal medicine residents experienced statistically significant improvements for “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians” and nonstatistically significant improvements for the other 3 domains, likely because the intervention enabled them to focus on clinical care rather than the administrative tasks and decision-making complexities inherent to the IM admission process. Internal medicine attendings reported a nonstatistically significant worsening in “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians,” which is possibly attributable to challenges connecting with ED attendings after being notified that a new admission is pending. Unfortunately, bedside handoff was not hardwired and is done sporadically. Independent of the data, we believe that the triage hospitalist role has facilitated closer ED-IM relationships by aligning clinical priorities, standardizing processes, improving communication, and reducing sources of hierarchical imbalance and conflict. We expected IM attendings and residents to experience some degree of resolution of the perception that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” because of the addition of a dedicated triage role. Our data also suggest that IM attendings are less likely to agree that “patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Both concerns may be linked to the triage hospitalist facing multiple admission and transfer sources with variable arrival rates and variable patient complexity, resulting in high cognitive load and the perception that individual tasks are not completed to the best of their abilities.

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of the triage hospitalist role on throughput, clinical care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care. In the cross-sectional survey of 10 academic medical centers, 8 had defined triage roles filled by IM attendings, while the remainder had IM attendings supervising trainees.9 A complete picture of the prevalence and varying approaches of triage hospitalists models is unknown. Howell et al12 reported on an approach that reduced admission delays without a resulting increase in mortality or LOS. Our approach differed in several ways, with greater involvement of the triage hospitalist in determining a final admission decision, incorporation of EMR communication, and presence of existing throughput challenges preventing patients from moving seamlessly to an inpatient unit.

Conclusion

We believe this effort was successful for several reasons, including adherence to quality improvement best practices, such as engagement of stakeholders early on, the use of data to inform decision-making, the application of technology to hardwire process, and alignment with institutional priorities. Spread of this intervention will be limited by the financial investment required to start and maintain a triage hospitalist role. A primary limitation of this study is the confounding effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on our analysis. Next steps include identification of clinicians wishing to specialize in triage and expanding triage to include non-IM primary services. Additional research to optimize the triage hospitalist experience of care, as well as to measure improvements in patient-centered outcomes, is necessary.

Corresponding author: Christopher Bartlett, MD, MPH; MSC10 5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; CSBartlett@salud.unm.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Division of Hospital Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Drs. Bartlett, Pizanis, Angeli, Lacy, and Rogers), Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico Hospital, Albuquerque (Dr. Scott), and University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque (Ms. Baca).

ABSTRACT

Background: Emergency department (ED) crowding is associated with deleterious consequences for patient care and throughput. Admission delays worsen ED crowding. Time to admission (TTA)—the time between an ED admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders—can be shortened through implementation of a triage hospitalist role. Limited research is available highlighting the impact of triage hospitalists on throughput, care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care.

Methods: A triage hospitalist role was piloted and implemented. Run charts were interpreted using accepted rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions. Statistical analysis was applied to interprofessional practice and clinician experience-of-care survey results.

Results: Following implementation, TTA decreased from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Emergency department crowding increased from baseline. The reduction in TTA was associated with decreased time from ED arrival to IM admission request, no change in critical care transfers during the initial 24 hours, and increased admissions to inpatient status. Additionally, decreased TTA was associated with no change in referring hospital transfer rates and no change in hospital medicine length of stay. Interprofessional practice attitudes improved among ED clinicians but not IM clinicians. Clinician experience-of-care results were mixed.

Conclusion: A triage hospitalist role is an effective approach for mitigating admission delays, with no evident adverse clinical consequences. A triage hospitalist alone was incapable of resolving ED crowding issues without a complementary focus on downstream bottlenecks.

Keywords: triage hospitalist, admission delay, quality improvement.

Excess time to admission (TTA), defined as the time between an emergency department (ED) admission request and internal medicine (IM) admission orders, contributes to ED crowding, which is associated with deleterious impacts on patient care and throughput. Prior research has correlated ED crowding with an increase in length of stay (LOS)1-3 and total inpatient cost,1 as well as increased inpatient mortality, higher left-without-being-seen rates,4 delays in clinically meaningful care,5,6 and poor patient and clinician satisfaction.6,7 While various solutions have been proposed to alleviate ED crowding,8 excess TTA is one aspect that IM can directly address.

Like many institutions, ours is challenged by ED crowding. Time to admission is a known bottleneck. Underlying factors that contribute to excess TTA include varied admission request volumes in relation to fixed admitting capacity; learner-focused admitting processes; and unreliable strategies for determining whether patients are eligible for ED observation, transfer to an alternative facility, or admission to an alternative primary service.

To address excess TTA, we piloted then implemented a triage hospitalist role, envisioned as responsible for evaluating ED admission requests to IM, making timely determinations of admission appropriateness, and distributing patients to admitting teams. This intervention was selected because of its strengths, including the ability to standardize admission processes, improve the proximity of clinical decision-makers to patient care to reduce delays, and decrease hierarchical imbalances experienced by trainees, and also because the institution expressed a willingness to mitigate its primary weakness (ie, ongoing financial support for sustainability) should it prove successful.

Previously, a triage hospitalist has been defined as “a physician who assesses patients for admission, actively supporting the transition of the patient from the outpatient to the inpatient setting.”9 Velásquez et al surveyed 10 academic medical centers and identified significant heterogeneity in the roles and responsibilities of a triage hospitalist.9 Limited research addresses the impact of this role on throughput. One report described the volume and source of requests evaluated by a triage hospitalist and the frequency with which the triage hospitalists’ assessment of admission appropriateness aligned with that of the referring clinicians.10 No prior research is available demonstrating the impact of this role on care quality, interprofessional practice, or clinician experience of care. This article is intended to address these gaps in the literature.

Methods

Setting

The University of New Mexico Hospital has 537 beds and is the only level-1 trauma and academic medical center in the state. On average, approximately 8000 patients register to be seen in the ED per month. Roughly 600 are admitted to IM per month. This study coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, with low patient volumes in April 2020, overcapacity census starting in May 2020, and markedly high patient volumes in May/June 2020 and November/December 2020. All authors participated in project development, implementation, and analysis.

Preintervention IM Admission Process

When requesting IM admission, ED clinicians (resident, advanced practice provider [APP], or attending) contacted the IM triage person (typically an IM resident physician) by phone or in person. The IM triage person would then assess whether the patient needed critical care consultation (a unique and separate admission pathway), was eligible for ED observation or transfer to an outside hospital, or was clinically appropriate for IM subacute and floor admission. Pending admissions were evaluated in order of severity of illness or based on wait time if severity of illness was equal. Transfers from the intensive care unit (ICU) and referring hospitals were prioritized. Between 7:00

Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Key changes made during the pilot included scheduling an IM attending to serve as triage hospitalist for all IM admission requests from the ED between 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Pilot

Data collected included request type (new vs overflow from night) and patient details (name, medical record number). Two time points were recorded: when the EDAR order was entered and when admission orders were entered. Process indicators, including whether the EDAR order was entered and the final triage decision (eg, discharge, IM), were recorded. General feedback was requested at the end of each shift.

Phased Implementation of Triage Hospitalist Role

Triage hospitalist role implementation was approved following the pilot, with additional salary support funded by the institution. A new performance measure (time from admission request to admission order, self-identified goal < 3 hours) was approved by all parties.

In January 2020, the role was scheduled from 7:00

In March 2020, to create a single communication pathway while simultaneously hardwiring our measurement strategy, the EDAR order was modified such that it would automatically prompt a 1-way communication to the triage hospitalist using the institution’s secure messaging software. The message included patient name, medical record number, location, ED attending, reason for admission, and consultation priority, as well as 2 questions prompting ED clinicians to reflect on the most common reasons for the triage hospitalist to recommend against IM admission (eligible for admission to other primary service, transfer to alternative hospital).

In July 2020, the triage hospitalist role was scheduled 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to meet an institutional request. The schedule was divided into a daytime 7:00

Measures for Triage Hospitalist Role

The primary outcome measure was TTA, defined as the time between EDAR (operationalized using EDAR order timestamp) and IM admission decision (operationalized using inpatient bed request order timestamp). Additional outcome measures included the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Electronic Clinical Quality Measure ED-2 (eCQM ED-2), defined as the median time from admit decision to departure from the ED for patients admitted to inpatient status.

Process measures included time between patient arrival to the ED (operationalized using ED registration timestamp) and EDAR and percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order. Balancing measures included time between bed request order (referred to as the IM admission order) and subsequent admission orders. While the IM admission order prompts an inpatient clinical encounter and inpatient bed assignment, subsequent admission orders are necessary for clinical care. Additional balancing measures included ICU transfer rate within the first 24 hours, referring facility transfer frequency to IM (an indicator of access for patients at outside hospitals), average hospital medicine LOS (operationalized using ED registration timestamp to discharge timestamp), and admission status (inpatient vs observation).

An anonymous preintervention (December 2019) and postintervention (August 2020) survey focusing on interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care was used to obtain feedback from ED and IM attendings, APPs, and trainees. Emergency department clinicians were asked questions pertaining to their IM colleagues and vice versa. A Likert 5-point scale was used to respond.

Data Analysis

The preintervention period was June 1, 2019, to October 31, 2019; the pilot period was November 1, 2019, to December 31, 2019; the staged implementation period was January 1, 2020, to June 30, 2020; and the postintervention period was July 1, 2020, to December 31, 2020. Run charts for outcome, process, and balancing measures were interpreted using rules for deriving statistically significant conclusions.11 Statistical analysis using a t test assuming unequal variances with P < . 05 to indicate statistical significance was applied to experience-of-care results. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Triage Hospitalist Pilot Time Period

Seventy-four entries were recorded, 56 (75.7%) reflecting new admission requests. Average time between EDAR order and IM admission order was 40 minutes. The EDAR order was entered into the EMR without prompting in 22 (29.7%) cases. In 56 (75.7%) cases, the final triage decision was IM admission. Other dispositions included 3 discharges, 4 transfers, 3 alternative primary service admissions, 1 ED observation, and 7 triage deferrals pending additional workup or stabilization.

Feedback substantiated several benefits, including improved coordination among IM, ED, and consultant clinicians, as well as early admission of seriously ill patients. Feedback also confirmed several expected challenges, including evidence of communication lapses, difficulty with transfer coordinator integration, difficulty hardwiring elements of the verbal and bedside handoff, and perceived high cognitive load for the triage hospitalist. Several unexpected issues included whether ED APPs can request admission independently and how reconsultation is expected to occur if admission is initially deferred.

Triage Hospitalist Implementation Time Period

Time to admission decreased from a baseline pre-pilot average of 5 hours 19 minutes (median, 4 hours 45 minutes) to a postintervention average of 2 hours 8 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention (Figure 1).

ED-2 increased from a baseline average of 3 hours 40 minutes (median, 2 hours 39 minutes), with a statistically significant upward shift starting in May 2020 (Figure 2). Time between patient arrival to the ED and EDAR order decreased from a baseline average of 8 hours 47 minutes (median, 8 hours 37 minutes) to a postintervention average of 5 hours 57 minutes, with a statistically significant downward shift post intervention. Percentage of IM admissions with an EDAR order increased from a baseline average of 47% (median, 47%) to 97%, with a statistically significant upward shift starting in January 2020 (Figure 3).

There was no change in observed average time between IM admission order and subsequent admission orders pre and post intervention (16 minutes vs 18 minutes). However, there was a statistically significant shift up to an average of 40 minutes from January through June 2020, which then resolved. The percentage of patients transferred to the ICU within 24 hours of admission to IM did not change (1.1% pre vs 1.4% post intervention). Frequency of patients transferred in from a referring facility also did not change (26/month vs 22/month). Average hospital medicine LOS did not change to a statistically significant degree (6.48 days vs 6.62 days). The percentage of inpatient admissions relative to short stays increased from a baseline of 74.0% (median, 73.6%) to a postintervention average of 82.4%, with a statistically significant shift upward starting March 2020.

Regarding interprofessional practice and clinician experience of care, 122 of 309 preintervention surveys (39.5% response rate) and 98 of 309 postintervention surveys (31.7% response rate) were completed. Pre- and postintervention responses were not linked.

Regarding interprofessional practice, EM residents and EM attendings experienced statistically significant improvements in all interprofessional practice domains (Table 1). Emergency medicine APPs experienced statistically significant improvements post intervention with “I am satisfied with the level of communication with IM hospitalist clinicians” and “Interactions

For clinician experience of care, EM residents (P < .001) and attendings (P < .001) experienced statistically significant improvements in “Patients are well informed and involved in the decision to admit,” whereas IM residents and attendings, as well as EM APPs, experienced nonstatistically significant improvements (Table 2). All groups except IM attendings experienced a statistically significant improvement (IM resident P = .011, EM resident P < .001, EM APP P = .001, EM attending P < .001) in “I believe that my patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Internal medicine attendings felt that this indicator worsened to a nonstatistically significant degree. Post intervention, EM groups experienced a statistically significant worsening in “The process of admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult,” while IM groups experienced a nonstatistically significant worsening.

Discussion

Implementation of the triage hospitalist role led to a significant reduction in average TTA, from 5 hours 19 minutes to 2 hours 8 minutes. Performance has been sustained at 1 hour 42 minutes on average over the past 6 months. The triage hospitalist was successful at reducing TTA because of their focus on evaluating new admission and transfer requests, deferring other admission responsibilities to on-call admitting teams. Early admission led to no increase in ICU transfers or hospitalist LOS. To ensure that earlier admission reflected improved timeliness of care and that new sources of delay were not being created, we measured the time between IM admission and subsequent admission orders. A statistically significant increase to 40 minutes from January through June 2020 was attributable to the hospitalist acclimating to their new role and the need to standardize workflow. This delay subsequently resolved. An additional benefit of the triage hospitalist was an increase in the proportion of inpatient admissions compared with short stays.

ED-2, an indicator of ED crowding, increased from 3 hours 40 minutes, with a statistically significant upward shift starting May 2020. Increasing ED-2 associated with the triage hospitalist role makes intuitive sense. Patients are admitted 2 hours 40 minutes earlier in their hospital course while downstream bottlenecks preventing patient movement to an inpatient bed remained unchanged. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic complicates interpretation of ED-2 because the measure reflects institutional capacity to match demand for inpatient beds. Fewer ED registrations and lower hospital medicine census (and resulting inpatient bed availability) in April 2020 during the first COVID-19 surge coincided with an ED-2 nadir of 1 hour 46 minutes. The statistically significant upward shift from May onward reflects ongoing and unprecedented patient volumes. It remains difficult to tease apart the presumed lesser contribution of the triage hospitalist role and presumed larger contribution of high patient volumes on ED-2 increases.

An important complementary change was linkage between the EDAR order and our secure messaging software, creating a single source of admission and transfer requests, prompting early ED clinician consideration of factors that could result in alternative disposition, and ensuring a sustainable data source for TTA. The order did not replace direct communication and included guidance for how triage hospitalists should connect with their ED colleagues. Percentage of IM admissions with the EDAR order increased to 97%. Fallouts are attributed to admissions from non-ED sources (eg, referring facility, endoscopy suite transfers). This communication strategy has been expanded as the primary mechanism of initiating consultation requests between IM and all consulting services.

This intervention was successful from the perspective of ED clinicians. Improvements can be attributed to the simplified admission process, timely patient assessment, a perception that patients are better informed of the decision to admit, and the ability to communicate with the triage hospitalist. Emergency medicine APPs may not have experienced similar improvements due to ongoing perceptions of a hierarchical imbalance. Unfortunately, the small but not statistically significant worsening perspective among ED clinicians that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” and the statistically significant worsening perspective that “admitting patients to a UNM IM hospitalist service is difficult” may be due to the triage hospitalist responsibility for identifying the roughly 25% of patients who are safe for an alternative disposition.

Internal medicine clinicians experienced no significant changes in attitudes. Underlying causes are likely multifactorial and a focus of ongoing work. Internal medicine residents experienced statistically significant improvements for “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians” and nonstatistically significant improvements for the other 3 domains, likely because the intervention enabled them to focus on clinical care rather than the administrative tasks and decision-making complexities inherent to the IM admission process. Internal medicine attendings reported a nonstatistically significant worsening in “I am satisfied with the level of communication with EM clinicians,” which is possibly attributable to challenges connecting with ED attendings after being notified that a new admission is pending. Unfortunately, bedside handoff was not hardwired and is done sporadically. Independent of the data, we believe that the triage hospitalist role has facilitated closer ED-IM relationships by aligning clinical priorities, standardizing processes, improving communication, and reducing sources of hierarchical imbalance and conflict. We expected IM attendings and residents to experience some degree of resolution of the perception that “efficiency is more valued than good patient care” because of the addition of a dedicated triage role. Our data also suggest that IM attendings are less likely to agree that “patients are evaluated and treated within an appropriate time frame.” Both concerns may be linked to the triage hospitalist facing multiple admission and transfer sources with variable arrival rates and variable patient complexity, resulting in high cognitive load and the perception that individual tasks are not completed to the best of their abilities.

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of the triage hospitalist role on throughput, clinical care quality, interprofessional practice, and clinician experience of care. In the cross-sectional survey of 10 academic medical centers, 8 had defined triage roles filled by IM attendings, while the remainder had IM attendings supervising trainees.9 A complete picture of the prevalence and varying approaches of triage hospitalists models is unknown. Howell et al12 reported on an approach that reduced admission delays without a resulting increase in mortality or LOS. Our approach differed in several ways, with greater involvement of the triage hospitalist in determining a final admission decision, incorporation of EMR communication, and presence of existing throughput challenges preventing patients from moving seamlessly to an inpatient unit.

Conclusion

We believe this effort was successful for several reasons, including adherence to quality improvement best practices, such as engagement of stakeholders early on, the use of data to inform decision-making, the application of technology to hardwire process, and alignment with institutional priorities. Spread of this intervention will be limited by the financial investment required to start and maintain a triage hospitalist role. A primary limitation of this study is the confounding effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on our analysis. Next steps include identification of clinicians wishing to specialize in triage and expanding triage to include non-IM primary services. Additional research to optimize the triage hospitalist experience of care, as well as to measure improvements in patient-centered outcomes, is necessary.

Corresponding author: Christopher Bartlett, MD, MPH; MSC10 5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; CSBartlett@salud.unm.edu

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Huang Q, Thind A, Dreyer JF, et al. The impact of delays to admission from the emergency department on inpatient outcomes. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10:16. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-10-16

2. Liew D, Liew D, Kennedy MP. Emergency department length of stay independently predicts excess inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2003;179:524-526. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05676.x

3. Richardson DB. The access-block effect: relationship between delay to reaching an inpatient bed and inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2002;177:492-495. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04917.x

4. Polevoi SK, Quinn JV, Kramer KR. Factors associated with patients who leave without being seen. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:232-236. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.029

5. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x

6. Vieth TL, Rhodes KV. The effect of crowding on access and quality in an academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:787-794. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.026

7. Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: the impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50:327-340; discussion 341-342.

8. Emergency Department Crowding: High Impact Solutions. American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Medicine Practice Committee. 2016. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/crowding/empc_crowding-ip_092016.pdf

9. Velásquez ST, Wang ES, White AW, et al. Hospitalists as triagists: description of the triagist role across academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:87-90. doi:10.12788/jhm.3327

10. Amick A, Bann M. Characterizing the role of the “triagist”: reasons for triage discordance and impact on disposition. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2177-2179. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05887-y

11. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning for variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037895

12. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x

1. Huang Q, Thind A, Dreyer JF, et al. The impact of delays to admission from the emergency department on inpatient outcomes. BMC Emerg Med. 2010;10:16. doi:10.1186/1471-227X-10-16

2. Liew D, Liew D, Kennedy MP. Emergency department length of stay independently predicts excess inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2003;179:524-526. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05676.x

3. Richardson DB. The access-block effect: relationship between delay to reaching an inpatient bed and inpatient length of stay. Med J Aust. 2002;177:492-495. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04917.x

4. Polevoi SK, Quinn JV, Kramer KR. Factors associated with patients who leave without being seen. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:232-236. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.029

5. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x

6. Vieth TL, Rhodes KV. The effect of crowding on access and quality in an academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:787-794. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.026

7. Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: the impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50:327-340; discussion 341-342.

8. Emergency Department Crowding: High Impact Solutions. American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Medicine Practice Committee. 2016. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/crowding/empc_crowding-ip_092016.pdf

9. Velásquez ST, Wang ES, White AW, et al. Hospitalists as triagists: description of the triagist role across academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:87-90. doi:10.12788/jhm.3327

10. Amick A, Bann M. Characterizing the role of the “triagist”: reasons for triage discordance and impact on disposition. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2177-2179. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05887-y

11. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning for variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037895

12. Howell EE, Bessman ES, Rubin HR. Hospitalists and an innovative emergency department admission process. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:266-268. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30431.x

What Is the Best Approach to a Cavitary Lung Lesion?

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.