User login

Rupioid Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in a Patient With Skin of Color

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

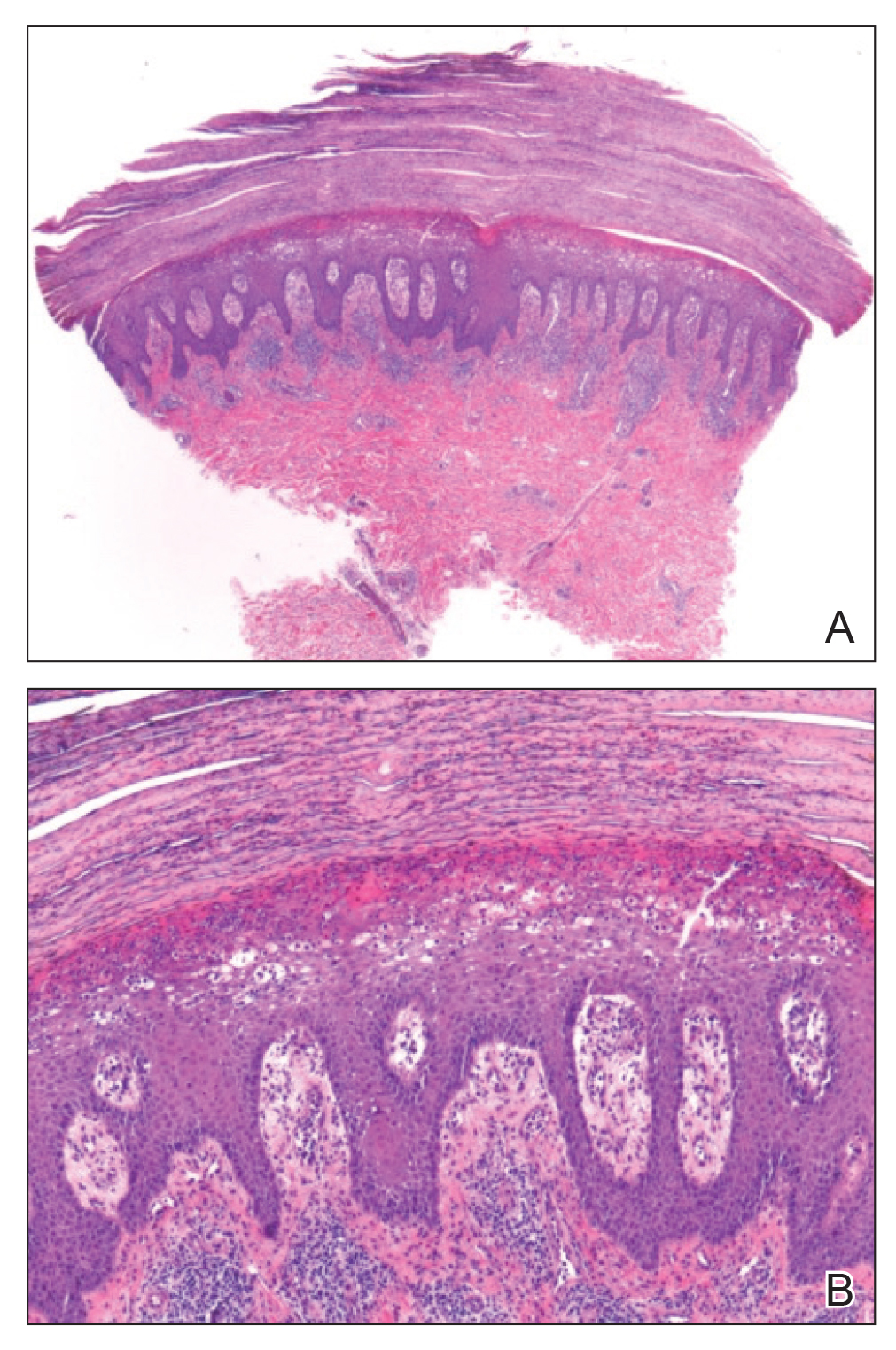

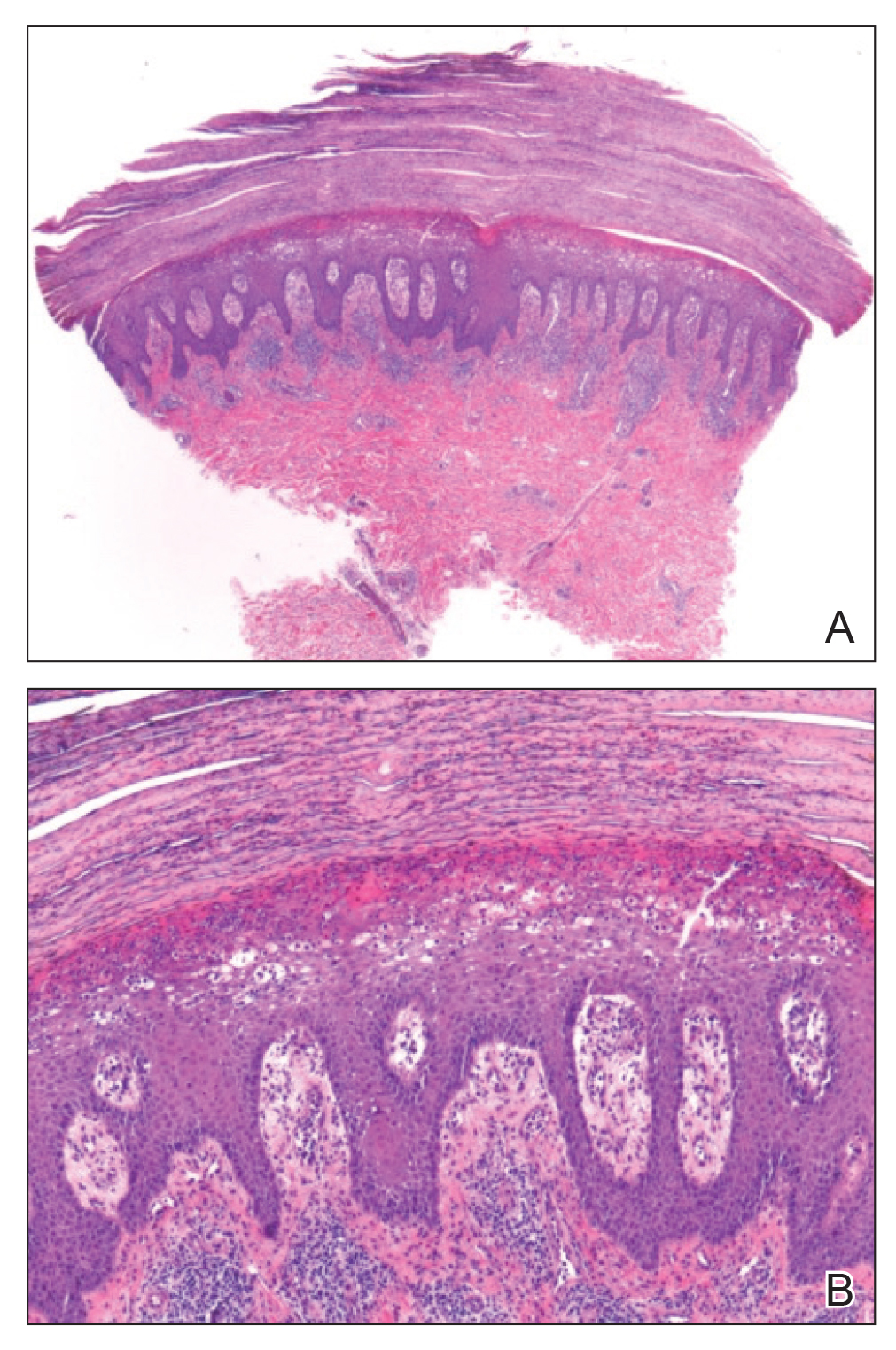

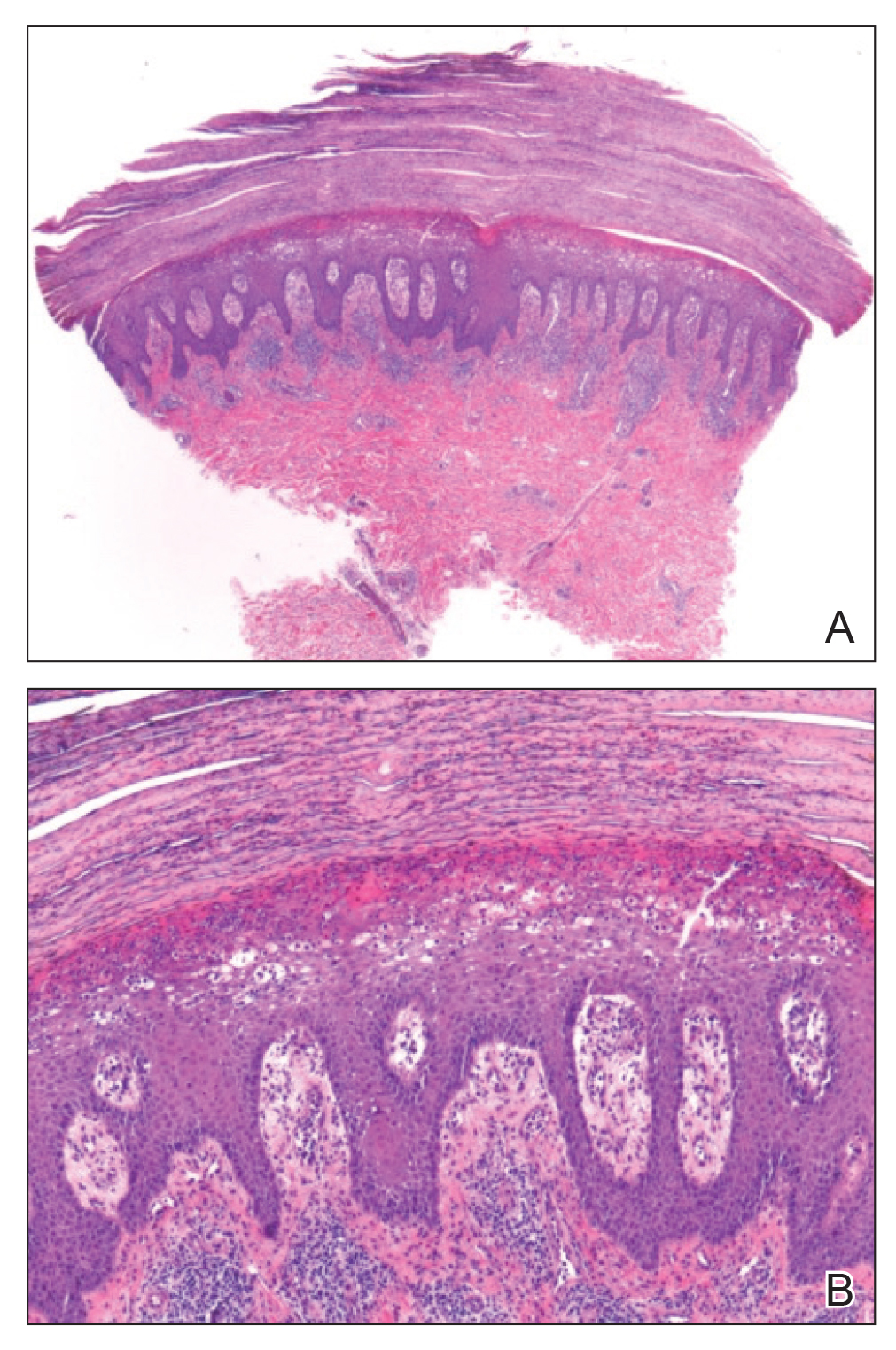

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

Practice Points

- Rupioid psoriasis in skin of color may present a diagnostic challenge for health care providers.

- Rupioid psoriasis may represent a psoriasis variant that is highly responsive to treatment.

Punctate Depigmented Macules

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Punctate Vitiligo

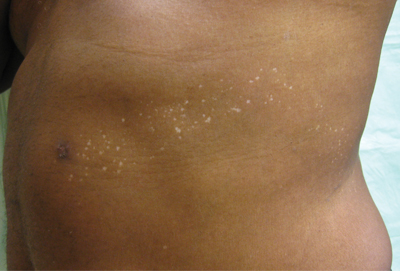

Based on the patient’s clinical appearance as well as the histologic findings, the diagnosis of vitiligo was made. Although vitiligo is certainly not uncommon and punctate vitiligo is a known clinical presentation,1 punctate vitiliginous depigmentation conforming to lines of Blaschko is unique. Follicular repigmentation in a patch of vitiligo potentially could lead to this “spotty” appearance, but our patient maintained that the band was never confluently depigmented and that small macules arose within normally pigmented skin. The patient’s adult age at onset makes this case even more unusual.

Follicular repigmentation in vitiligo is fairly well understood, as the perifollicular pigment is formed by upward migration of activated melanoblasts in the outer root sheath.2 Follicular depigmentation as well as selective or initial loss of melanocytes around hair follicles in early vitiligo has not been described. It is unclear if the seemingly folliculocentric nature of the patient’s vitiliginous macules was a false observation, coincidental, or actually related to selective melanocyte loss around follicles.

Blaschkoid distribution has been described in numerous skin disorders and is known to be based on genetic mosaicism.3 Most of these disorders are X-linked and/or congenital. However, many acquired skin conditions have been described exhibiting blaschkoid distribution, such as vitiligo, psoriasis, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides.4,5

Confettilike depigmentation has been described as an unusual clinical variant of vitiligo.1 It also has been reported after psoralen plus UVA therapy in patients with more classic vitiligo,6 numerous domestic chemicals,7 and in association with mycosis fungoides.8 In these cases, punctate lesions were disseminated, symmetric on extremities, or limited to areas exposed to chemicals.

1. Ortonne J-P. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:913-938.

2. Cui J, Shen LY, Wang GC. Role of hair follicles in the repigmentation of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:410-416.

3. Happle R. X-chromosome inactivation: role in skin disease expression. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;95:16-23.

4. Taieb A. Linear atopic dermatitis (“naevus atopicus”): a pathogenetic clue? Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:134-135.

5. Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:157-190.

6. Falabella R, Escobar CE, Carrascal E, et al. Leukoderma punctata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:485-494.

7. Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinico-aetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

8. Loquai C, Metza D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Punctate Vitiligo

Based on the patient’s clinical appearance as well as the histologic findings, the diagnosis of vitiligo was made. Although vitiligo is certainly not uncommon and punctate vitiligo is a known clinical presentation,1 punctate vitiliginous depigmentation conforming to lines of Blaschko is unique. Follicular repigmentation in a patch of vitiligo potentially could lead to this “spotty” appearance, but our patient maintained that the band was never confluently depigmented and that small macules arose within normally pigmented skin. The patient’s adult age at onset makes this case even more unusual.

Follicular repigmentation in vitiligo is fairly well understood, as the perifollicular pigment is formed by upward migration of activated melanoblasts in the outer root sheath.2 Follicular depigmentation as well as selective or initial loss of melanocytes around hair follicles in early vitiligo has not been described. It is unclear if the seemingly folliculocentric nature of the patient’s vitiliginous macules was a false observation, coincidental, or actually related to selective melanocyte loss around follicles.

Blaschkoid distribution has been described in numerous skin disorders and is known to be based on genetic mosaicism.3 Most of these disorders are X-linked and/or congenital. However, many acquired skin conditions have been described exhibiting blaschkoid distribution, such as vitiligo, psoriasis, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides.4,5

Confettilike depigmentation has been described as an unusual clinical variant of vitiligo.1 It also has been reported after psoralen plus UVA therapy in patients with more classic vitiligo,6 numerous domestic chemicals,7 and in association with mycosis fungoides.8 In these cases, punctate lesions were disseminated, symmetric on extremities, or limited to areas exposed to chemicals.

The Diagnosis: Blaschkoid Punctate Vitiligo

Based on the patient’s clinical appearance as well as the histologic findings, the diagnosis of vitiligo was made. Although vitiligo is certainly not uncommon and punctate vitiligo is a known clinical presentation,1 punctate vitiliginous depigmentation conforming to lines of Blaschko is unique. Follicular repigmentation in a patch of vitiligo potentially could lead to this “spotty” appearance, but our patient maintained that the band was never confluently depigmented and that small macules arose within normally pigmented skin. The patient’s adult age at onset makes this case even more unusual.

Follicular repigmentation in vitiligo is fairly well understood, as the perifollicular pigment is formed by upward migration of activated melanoblasts in the outer root sheath.2 Follicular depigmentation as well as selective or initial loss of melanocytes around hair follicles in early vitiligo has not been described. It is unclear if the seemingly folliculocentric nature of the patient’s vitiliginous macules was a false observation, coincidental, or actually related to selective melanocyte loss around follicles.

Blaschkoid distribution has been described in numerous skin disorders and is known to be based on genetic mosaicism.3 Most of these disorders are X-linked and/or congenital. However, many acquired skin conditions have been described exhibiting blaschkoid distribution, such as vitiligo, psoriasis, lichen planus, atopic dermatitis, and mycosis fungoides.4,5

Confettilike depigmentation has been described as an unusual clinical variant of vitiligo.1 It also has been reported after psoralen plus UVA therapy in patients with more classic vitiligo,6 numerous domestic chemicals,7 and in association with mycosis fungoides.8 In these cases, punctate lesions were disseminated, symmetric on extremities, or limited to areas exposed to chemicals.

1. Ortonne J-P. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:913-938.

2. Cui J, Shen LY, Wang GC. Role of hair follicles in the repigmentation of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:410-416.

3. Happle R. X-chromosome inactivation: role in skin disease expression. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;95:16-23.

4. Taieb A. Linear atopic dermatitis (“naevus atopicus”): a pathogenetic clue? Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:134-135.

5. Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:157-190.

6. Falabella R, Escobar CE, Carrascal E, et al. Leukoderma punctata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:485-494.

7. Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinico-aetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

8. Loquai C, Metza D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

1. Ortonne J-P. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2003:913-938.

2. Cui J, Shen LY, Wang GC. Role of hair follicles in the repigmentation of vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:410-416.

3. Happle R. X-chromosome inactivation: role in skin disease expression. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006;95:16-23.

4. Taieb A. Linear atopic dermatitis (“naevus atopicus”): a pathogenetic clue? Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:134-135.

5. Bolognia JL, Orlow SJ, Glick SA. Lines of Blaschko. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:157-190.

6. Falabella R, Escobar CE, Carrascal E, et al. Leukoderma punctata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:485-494.

7. Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay S. Chemical leucoderma: a clinico-aetiological study of 864 cases in the perspective of a developing country. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:40-47.

8. Loquai C, Metza D, Nashan D, et al. Confetti-like lesions with hyperkeratosis: a novel ultraviolet-induced hypomelanotic disorder? Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:190-193.

An otherwise healthy 54-year-old black man presented with a 10-year history of spotty pigmentary loss in a band on the left side of the abdomen, flank, and back. He denied a history of rash or inflammation in the area and had not experienced confluent depigmentation. He reported that initially he had only a few “white dots,” and over the next 5 to 7 years, he developed more of them confined within the same area. On presentation, he stated new areas of depigmentation had not developed in several years. The band was completely asymptomatic and had not been treated with any prescription or over-the-counter medications. On examination he had multiple 2- to 3-mm confettilike depigmented macules that seemed to be centered around follicles in a band with blaschkoid distribution extending across the left side of the abdomen, flank, and back. The band did not cross the midline and similar lesions were not present elsewhere. A punch biopsy of one of the depigmented macules revealed a markedly diminished number of melanocytes along the junction as well as a decrease in melanin, which was confirmed by Melan-A and Fontana stains, respectively.