User login

Necrotic Papules in a Pediatric Patient

The Diagnosis: Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta

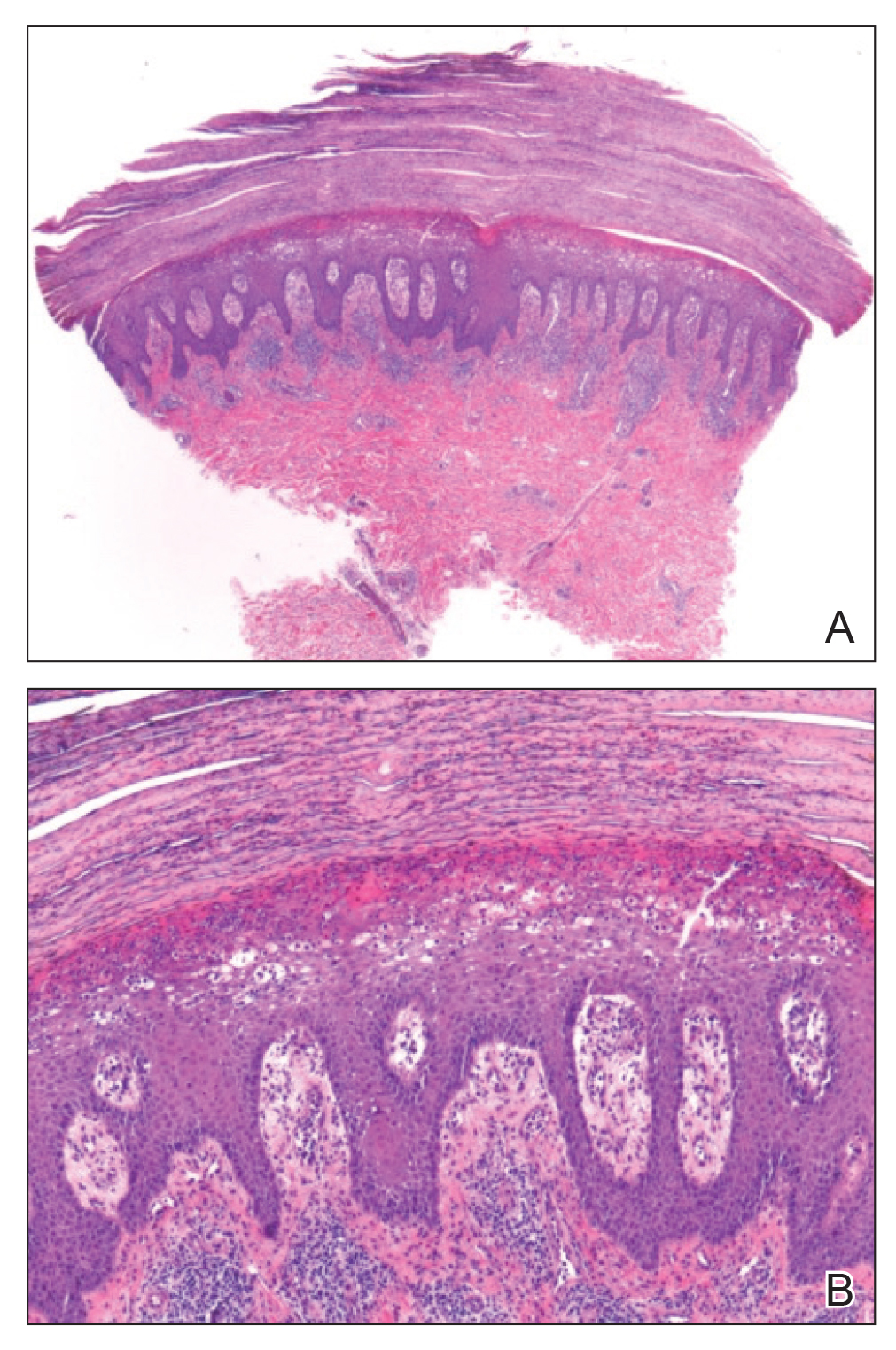

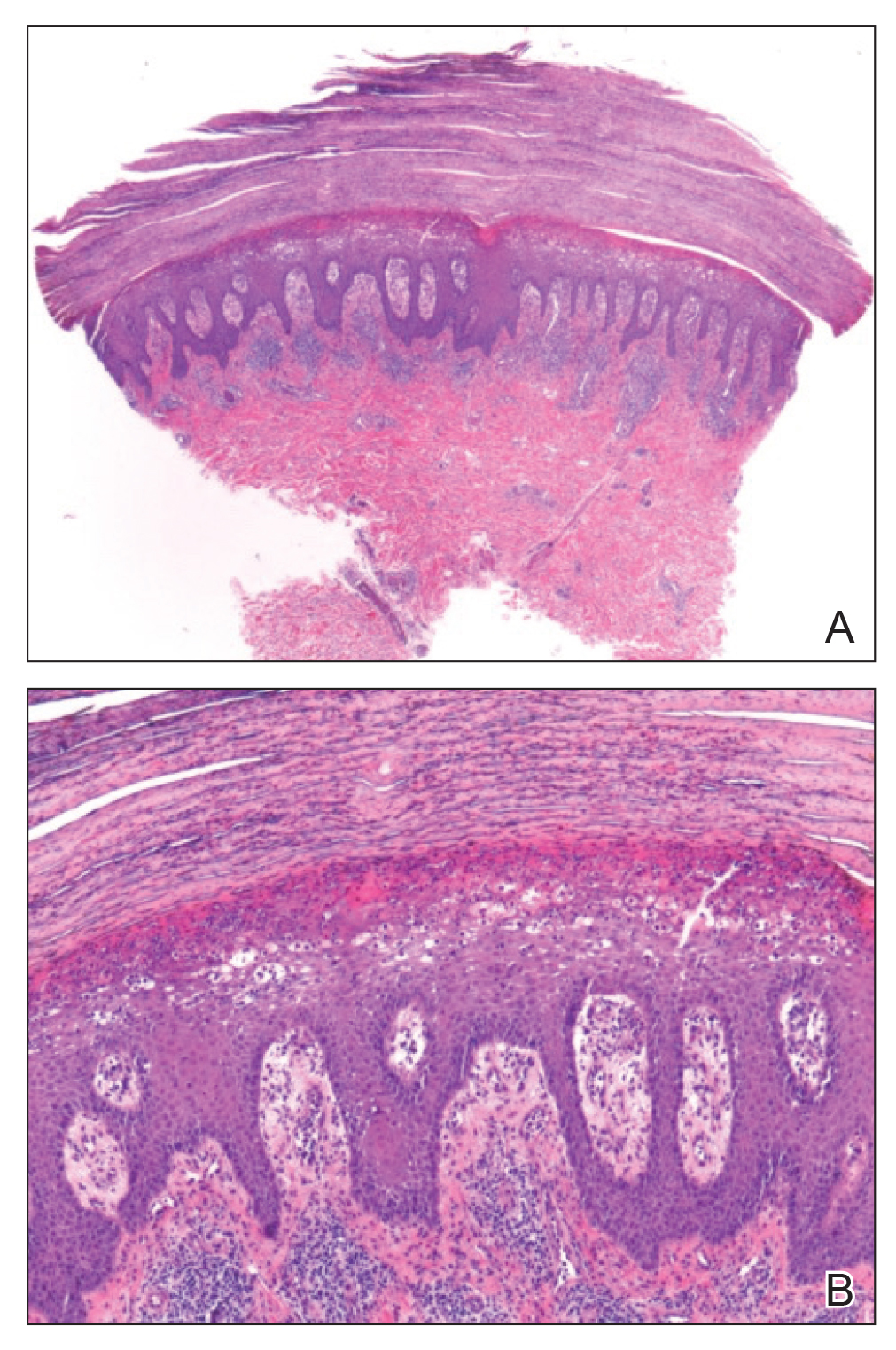

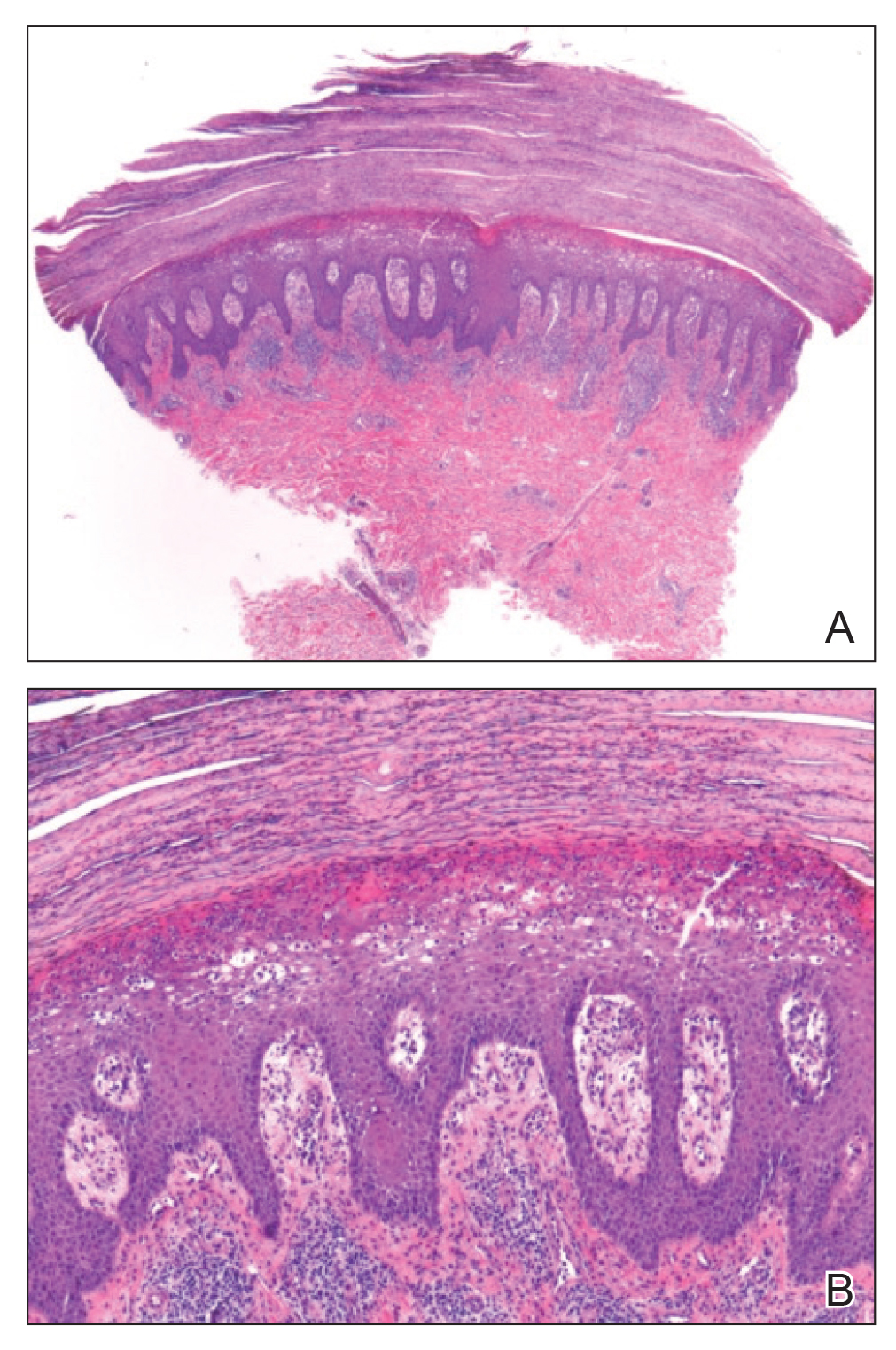

Sectioned punch biopsies were performed on the patient’s right arm. Histopathology showed acanthosis and parakeratosis in the epidermis, with vacuolar degeneration and dyskeratosis in the basal layer. Dermal changes included extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis as well as perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in both the papillary and reticular dermis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional biopsy using anti–human IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin conjugates showed no findings of immune deposition. Biopsy results were consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), and the patient was treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin, triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily, and phototherapy with narrowband UVB 3 times weekly. Rapid improvement was noted at 2-month follow-up.

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a form of pityriasis lichenoides, a group of inflammatory dermatoses that are characterized clinically by successive crops of morphologically diverse lesions. Epidemiologic studies have shown a slight male predominance. It primarily affects children and young adults, with peak ages of 8 and 32 years in pediatric and adult populations, respectively.1

The pathogenesis of PLEVA remains unclear. An abnormal immune response to Toxoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and other pathogens has been suggested based on serologic evidence of concurrent disease activity with the onset of lesions as well as cutaneous improvement in some patients after treatment of the infection.1 A T-cell lymphoproliferative etiology also has been considered based on histopathologic similarities between PLEVA and lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) as well as findings of clonality in T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in many patients.1,2 Some clinicians consider LyP and PLEVA as separate entities on one disease spectrum.

Eruptions of PLEVA tend to favor the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions may begin as macules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter that quickly evolve into papules with fine scale that remains attached centrally. Ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts also may be noted as the lesions progress in stage. The rash may persist for weeks to years, and overlapping crops of macules and papules at varying stages of development may be seen in the same patient.1

Histopathologic findings of PLEVA include spongiosis, dyskeratosis, parakeratosis, and focal keratinocyte necrosis within the epidermis, as well as vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer. Lymphocyte and erythrocyte extravasation may extend into the epidermis. Dermal findings may include edema and wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending into the reticular dermis.1

Important differential diagnoses to consider include LyP, mycosis fungoides (MF), pemphigus foliaceus, and varicella. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a benign CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent course of recurrent, often self-resolving papules that occur most frequently on the trunk, arms, and legs of older patients. There are several histologic subtypes of LyP, but the most common (type A) may manifest with wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the dermis, similar to PLEVA. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies characteristically reveal clonality in LyP, and clonality has been reported in PLEVA. However, LyP demonstrates a higher cytologic grade and lacks the characteristic parakeratotic scale and superficial dermal microhemorrhage of PLEVA.3

Mycosis fungoides is a malignant lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent clinical course of persistent patches, plaques, or tumors of various sizes that often manifest in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin. Early stages of MF are difficult to detect histologically, but biopsies may show atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic, irregularly contoured nuclei arranged along the basal layer of the epidermis. Epidermal aggregates of atypical lymphocytes (also known as Pautrier microabscesses) are considered highly specific for MF. T-cell receptor and immunopathologic studies also are important adjuncts in the diagnosis of MF.4

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease caused by antibodies directed against desmoglein 1, which is found in the granular layer of the epidermis. It manifests with a subtle onset of scattered crusted lesions in the seborrheic areas, such as the scalp, face, chest, and upper back. Histopathologic findings of early blisters may include acantholysis and dyskeratosis in the stratum granulosum as well as vacuolization of the granular layer. The blisters may coalesce into superficial bullae containing fibrin and neutrophils. Immunofluorescence studies that demonstrate intraepidermal C3 and IgG deposition are key to the diagnosis of pemphigus.5

Varicella (also known as chickenpox) manifests with crops of vesicles on an erythematous base in a centripetal distribution favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. It often is preceded by prodromal fever, malaise, and myalgia. Histopathologic evaluation of varicella is uncommon but may reveal acantholysis, multinucleation, and nuclear margination of keratinocytes. Viral culture or nucleic acid amplification testing of lesions can be used to verify the diagnosis.6

Most cases of PLEVA resolve without intervention.7 Treatment is directed at speeding recovery, providing symptomatic relief, and limiting permanent sequelae. Topical steroids often are used to alleviate inflammation and pruritus. Systemic antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, and erythromycin have been used for their anti-inflammatory properties. Phototherapy of various wavelengths, including broadband and narrowband UVB as well as psoralen plus UVA, have led to improvements in affected patients. Refractory disease may warrant consideration of therapy with methotrexate, acitretin, dapsone, or cyclosporine.7

There have been rare reports of PLEVA evolving into its potentially lethal variant, febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, which is differentiated by the presence of systemic manifestations, including high fever, sore throat, diarrhea, central nervous system symptoms, abdominal pain, interstitial pneumonitis, splenomegaly, arthritis, sepsis, megaloblastic anemia, or conjunctival ulcers. The orogenital mucosa may be affected. Cutaneous lesions may rapidly progress to large, generalized, coalescent ulcers with necrotic crusts and vasculitic features on biopsy.8 Malignant transformation of PLEVA into LyP or MF rarely may occur and warrants continued follow-up of unresolved lesions.9

- Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:557-572. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.058

- Teklehaimanot F, Gade A, Rubenstein R. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73. doi:10.1111/jdv.15931

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057

- Lepe K, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. Pemphigus foliaceus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Ayoade F, Kumar S. Varicella zoster (chickenpox). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. A systematic review of treatments for pityriasis lichenoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2039-2049. doi:10.1111/jdv.15813

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738. doi:10.1111/ijd.13195

- Thomson KF, Whittaker SJ, Russell-Jones R, et al. Childhood cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in association with pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:1136-1152. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03232.x

The Diagnosis: Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta

Sectioned punch biopsies were performed on the patient’s right arm. Histopathology showed acanthosis and parakeratosis in the epidermis, with vacuolar degeneration and dyskeratosis in the basal layer. Dermal changes included extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis as well as perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in both the papillary and reticular dermis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional biopsy using anti–human IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin conjugates showed no findings of immune deposition. Biopsy results were consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), and the patient was treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin, triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily, and phototherapy with narrowband UVB 3 times weekly. Rapid improvement was noted at 2-month follow-up.

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a form of pityriasis lichenoides, a group of inflammatory dermatoses that are characterized clinically by successive crops of morphologically diverse lesions. Epidemiologic studies have shown a slight male predominance. It primarily affects children and young adults, with peak ages of 8 and 32 years in pediatric and adult populations, respectively.1

The pathogenesis of PLEVA remains unclear. An abnormal immune response to Toxoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and other pathogens has been suggested based on serologic evidence of concurrent disease activity with the onset of lesions as well as cutaneous improvement in some patients after treatment of the infection.1 A T-cell lymphoproliferative etiology also has been considered based on histopathologic similarities between PLEVA and lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) as well as findings of clonality in T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in many patients.1,2 Some clinicians consider LyP and PLEVA as separate entities on one disease spectrum.

Eruptions of PLEVA tend to favor the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions may begin as macules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter that quickly evolve into papules with fine scale that remains attached centrally. Ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts also may be noted as the lesions progress in stage. The rash may persist for weeks to years, and overlapping crops of macules and papules at varying stages of development may be seen in the same patient.1

Histopathologic findings of PLEVA include spongiosis, dyskeratosis, parakeratosis, and focal keratinocyte necrosis within the epidermis, as well as vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer. Lymphocyte and erythrocyte extravasation may extend into the epidermis. Dermal findings may include edema and wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending into the reticular dermis.1

Important differential diagnoses to consider include LyP, mycosis fungoides (MF), pemphigus foliaceus, and varicella. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a benign CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent course of recurrent, often self-resolving papules that occur most frequently on the trunk, arms, and legs of older patients. There are several histologic subtypes of LyP, but the most common (type A) may manifest with wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the dermis, similar to PLEVA. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies characteristically reveal clonality in LyP, and clonality has been reported in PLEVA. However, LyP demonstrates a higher cytologic grade and lacks the characteristic parakeratotic scale and superficial dermal microhemorrhage of PLEVA.3

Mycosis fungoides is a malignant lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent clinical course of persistent patches, plaques, or tumors of various sizes that often manifest in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin. Early stages of MF are difficult to detect histologically, but biopsies may show atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic, irregularly contoured nuclei arranged along the basal layer of the epidermis. Epidermal aggregates of atypical lymphocytes (also known as Pautrier microabscesses) are considered highly specific for MF. T-cell receptor and immunopathologic studies also are important adjuncts in the diagnosis of MF.4

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease caused by antibodies directed against desmoglein 1, which is found in the granular layer of the epidermis. It manifests with a subtle onset of scattered crusted lesions in the seborrheic areas, such as the scalp, face, chest, and upper back. Histopathologic findings of early blisters may include acantholysis and dyskeratosis in the stratum granulosum as well as vacuolization of the granular layer. The blisters may coalesce into superficial bullae containing fibrin and neutrophils. Immunofluorescence studies that demonstrate intraepidermal C3 and IgG deposition are key to the diagnosis of pemphigus.5

Varicella (also known as chickenpox) manifests with crops of vesicles on an erythematous base in a centripetal distribution favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. It often is preceded by prodromal fever, malaise, and myalgia. Histopathologic evaluation of varicella is uncommon but may reveal acantholysis, multinucleation, and nuclear margination of keratinocytes. Viral culture or nucleic acid amplification testing of lesions can be used to verify the diagnosis.6

Most cases of PLEVA resolve without intervention.7 Treatment is directed at speeding recovery, providing symptomatic relief, and limiting permanent sequelae. Topical steroids often are used to alleviate inflammation and pruritus. Systemic antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, and erythromycin have been used for their anti-inflammatory properties. Phototherapy of various wavelengths, including broadband and narrowband UVB as well as psoralen plus UVA, have led to improvements in affected patients. Refractory disease may warrant consideration of therapy with methotrexate, acitretin, dapsone, or cyclosporine.7

There have been rare reports of PLEVA evolving into its potentially lethal variant, febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, which is differentiated by the presence of systemic manifestations, including high fever, sore throat, diarrhea, central nervous system symptoms, abdominal pain, interstitial pneumonitis, splenomegaly, arthritis, sepsis, megaloblastic anemia, or conjunctival ulcers. The orogenital mucosa may be affected. Cutaneous lesions may rapidly progress to large, generalized, coalescent ulcers with necrotic crusts and vasculitic features on biopsy.8 Malignant transformation of PLEVA into LyP or MF rarely may occur and warrants continued follow-up of unresolved lesions.9

The Diagnosis: Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta

Sectioned punch biopsies were performed on the patient’s right arm. Histopathology showed acanthosis and parakeratosis in the epidermis, with vacuolar degeneration and dyskeratosis in the basal layer. Dermal changes included extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis as well as perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in both the papillary and reticular dermis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence of a perilesional biopsy using anti–human IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, and fibrin conjugates showed no findings of immune deposition. Biopsy results were consistent with pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), and the patient was treated with a 5-day course of oral azithromycin, triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily, and phototherapy with narrowband UVB 3 times weekly. Rapid improvement was noted at 2-month follow-up.

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta is a form of pityriasis lichenoides, a group of inflammatory dermatoses that are characterized clinically by successive crops of morphologically diverse lesions. Epidemiologic studies have shown a slight male predominance. It primarily affects children and young adults, with peak ages of 8 and 32 years in pediatric and adult populations, respectively.1

The pathogenesis of PLEVA remains unclear. An abnormal immune response to Toxoplasma, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, and other pathogens has been suggested based on serologic evidence of concurrent disease activity with the onset of lesions as well as cutaneous improvement in some patients after treatment of the infection.1 A T-cell lymphoproliferative etiology also has been considered based on histopathologic similarities between PLEVA and lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) as well as findings of clonality in T-cell receptor gene rearrangement in many patients.1,2 Some clinicians consider LyP and PLEVA as separate entities on one disease spectrum.

Eruptions of PLEVA tend to favor the trunk and proximal extremities. Lesions may begin as macules measuring 2 to 3 mm in diameter that quickly evolve into papules with fine scale that remains attached centrally. Ulcerations with hemorrhagic crusts also may be noted as the lesions progress in stage. The rash may persist for weeks to years, and overlapping crops of macules and papules at varying stages of development may be seen in the same patient.1

Histopathologic findings of PLEVA include spongiosis, dyskeratosis, parakeratosis, and focal keratinocyte necrosis within the epidermis, as well as vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer. Lymphocyte and erythrocyte extravasation may extend into the epidermis. Dermal findings may include edema and wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending into the reticular dermis.1

Important differential diagnoses to consider include LyP, mycosis fungoides (MF), pemphigus foliaceus, and varicella. Lymphomatoid papulosis is a benign CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent course of recurrent, often self-resolving papules that occur most frequently on the trunk, arms, and legs of older patients. There are several histologic subtypes of LyP, but the most common (type A) may manifest with wedge-shaped perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates in the dermis, similar to PLEVA. T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies characteristically reveal clonality in LyP, and clonality has been reported in PLEVA. However, LyP demonstrates a higher cytologic grade and lacks the characteristic parakeratotic scale and superficial dermal microhemorrhage of PLEVA.3

Mycosis fungoides is a malignant lymphoproliferative disorder that is characterized by an indolent clinical course of persistent patches, plaques, or tumors of various sizes that often manifest in non–sun-exposed areas of the skin. Early stages of MF are difficult to detect histologically, but biopsies may show atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic, irregularly contoured nuclei arranged along the basal layer of the epidermis. Epidermal aggregates of atypical lymphocytes (also known as Pautrier microabscesses) are considered highly specific for MF. T-cell receptor and immunopathologic studies also are important adjuncts in the diagnosis of MF.4

Pemphigus foliaceus is an autoimmune blistering disease caused by antibodies directed against desmoglein 1, which is found in the granular layer of the epidermis. It manifests with a subtle onset of scattered crusted lesions in the seborrheic areas, such as the scalp, face, chest, and upper back. Histopathologic findings of early blisters may include acantholysis and dyskeratosis in the stratum granulosum as well as vacuolization of the granular layer. The blisters may coalesce into superficial bullae containing fibrin and neutrophils. Immunofluorescence studies that demonstrate intraepidermal C3 and IgG deposition are key to the diagnosis of pemphigus.5

Varicella (also known as chickenpox) manifests with crops of vesicles on an erythematous base in a centripetal distribution favoring the trunk and proximal extremities. It often is preceded by prodromal fever, malaise, and myalgia. Histopathologic evaluation of varicella is uncommon but may reveal acantholysis, multinucleation, and nuclear margination of keratinocytes. Viral culture or nucleic acid amplification testing of lesions can be used to verify the diagnosis.6

Most cases of PLEVA resolve without intervention.7 Treatment is directed at speeding recovery, providing symptomatic relief, and limiting permanent sequelae. Topical steroids often are used to alleviate inflammation and pruritus. Systemic antibiotics such as doxycycline, minocycline, and erythromycin have been used for their anti-inflammatory properties. Phototherapy of various wavelengths, including broadband and narrowband UVB as well as psoralen plus UVA, have led to improvements in affected patients. Refractory disease may warrant consideration of therapy with methotrexate, acitretin, dapsone, or cyclosporine.7

There have been rare reports of PLEVA evolving into its potentially lethal variant, febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease, which is differentiated by the presence of systemic manifestations, including high fever, sore throat, diarrhea, central nervous system symptoms, abdominal pain, interstitial pneumonitis, splenomegaly, arthritis, sepsis, megaloblastic anemia, or conjunctival ulcers. The orogenital mucosa may be affected. Cutaneous lesions may rapidly progress to large, generalized, coalescent ulcers with necrotic crusts and vasculitic features on biopsy.8 Malignant transformation of PLEVA into LyP or MF rarely may occur and warrants continued follow-up of unresolved lesions.9

- Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:557-572. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.058

- Teklehaimanot F, Gade A, Rubenstein R. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73. doi:10.1111/jdv.15931

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057

- Lepe K, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. Pemphigus foliaceus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Ayoade F, Kumar S. Varicella zoster (chickenpox). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. A systematic review of treatments for pityriasis lichenoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2039-2049. doi:10.1111/jdv.15813

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738. doi:10.1111/ijd.13195

- Thomson KF, Whittaker SJ, Russell-Jones R, et al. Childhood cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in association with pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:1136-1152. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03232.x

- Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:557-572. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.07.058

- Teklehaimanot F, Gade A, Rubenstein R. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73. doi:10.1111/jdv.15931

- Pimpinelli N, Olsen EA, Santucci M, et al. Defining early mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1053-1063. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057

- Lepe K, Yarrarapu SNS, Zito PM. Pemphigus foliaceus. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Ayoade F, Kumar S. Varicella zoster (chickenpox). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. A systematic review of treatments for pityriasis lichenoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:2039-2049. doi:10.1111/jdv.15813

- Nofal A, Assaf M, Alakad R, et al. Febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha-Habermann disease: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:729-738. doi:10.1111/ijd.13195

- Thomson KF, Whittaker SJ, Russell-Jones R, et al. Childhood cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in association with pityriasis lichenoides chronica. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:1136-1152. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03232.x

A 7-year-old boy was referred to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a diffuse pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration. The rash began as scant erythematous papules on the face, and crops of similar lesions later erupted on the trunk, arms, and legs. He was treated previously by a pediatrician for scabies with topical permethrin followed by 2 doses of oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg without improvement. Physical examination revealed innumerable erythematous macules and papules with centrally adherent scaling distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs, as well as scant necrotic papules with a hemorrhagic crust and a peripheral rim of scale.

Wound Healing on the Dorsal Hands: An Intrapatient Comparison of Primary Closure, Purse-String Closure, and Secondary Intention

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

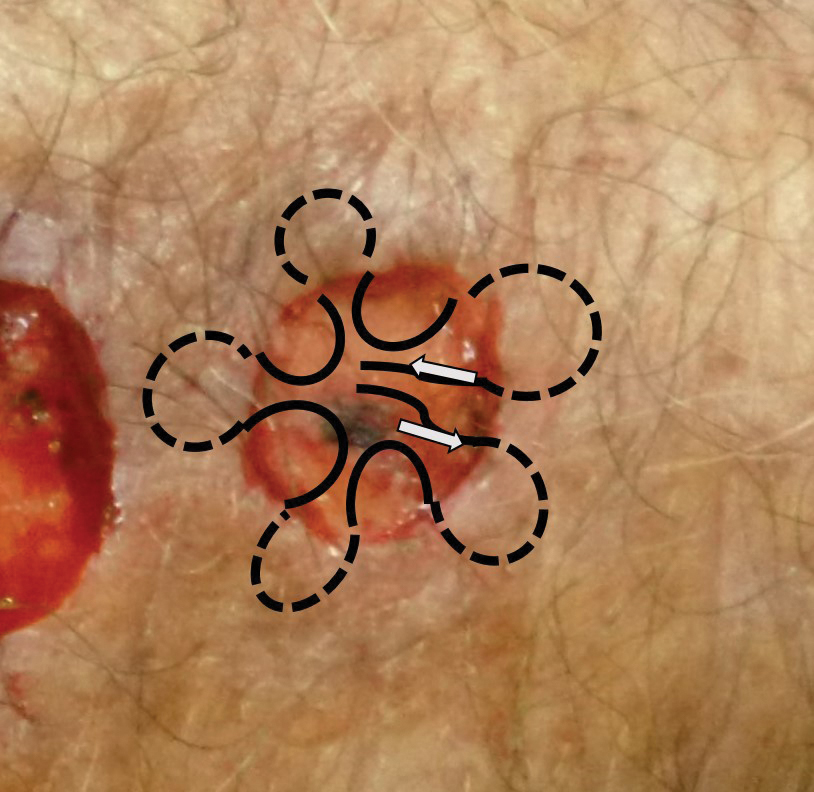

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

Practice Gap

Many cutaneous surgery wounds can be closed primarily; however, in certain cases, other repair options might be appropriate and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis with input from the patient. Defects on the dorsal aspect of the hands—where nonmelanoma skin cancer is common and reserve tissue is limited—often heal by secondary intention with good cosmetic and functional results. Patients often express a desire to reduce the time spent in the surgical suite and restrictions on postoperative activity, making secondary intention healing more appealing. An additional advantage is obviation of the need to remove additional tissue in the form of Burow triangles, which would lead to a longer wound. The major disadvantage of secondary intention healing is longer time to wound maturity; we often minimize this disadvantage with purse-string closure to decrease the size of the wound defect, which can be done quickly and without removing additional tissue.

The Technique

An elderly man had 3 nonmelanoma skin cancers—all on the dorsal aspect of the left hand—that were treated on the same day, leaving 3 similar wound defects after Mohs micrographic surgery. The wound defects (distal to proximal) measured 12 mm, 12 mm, and 10 mm in diameter (Figure 1) and were repaired by primary closure, secondary intention, and purse-string circumferential closure, respectively. Purse-string closure1 was performed with a 4-0 polyglactin 901 suture and left to heal without external sutures (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the 3 types of repairs immediately following closure. All wounds healed with excellent and essentially equivalent cosmetic results, with excellent patient satisfaction at 6-month follow-up (Figure 4).

Practical Implications

Our case illustrates different modalities of wound repair during precisely the same time frame and essentially on the same location. Skin of the dorsal hand often is tight; depending on the size of the defect, large primary closure can be tedious to perform, can lead to increased wound tension and risk of dehiscence, and can be uncomfortable for the patient during healing. However, primary closure typically will lead to faster healing.

Secondary intention healing and purse-string closure require less surgery and therefore cost less; these modalities yield similar cosmesis and satisfaction. In the appropriate context, secondary intention has been highlighted as a suitable alternative to primary closure2-4; in our experience (and that of others5), patient satisfaction is not diminished with healing by secondary intention. Purse-string closure also can minimize wound size and healing time.

For small shallow wounds on the dorsal hand, dermatologic surgeons should have confidence that secondary intention healing, with or without wound reduction using purse-string repair, likely will lead to acceptable cosmetic and functional results. Of course, repair should be tailored to the circumstances and wishes of the individual patient.

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

- Peled IJ, Zagher U, Wexler MR. Purse-string suture for reduction and closure of skin defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:465-469. doi:10.1097/00000637-198505000-00012

- Zitelli JA. Secondary intention healing: an alternative to surgical repair. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2:92-106. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(84)90031-2

- Fazio MJ, Zitelli JA. Principles of reconstruction following excision of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13:601-616. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(95)00099-2

- Bosley R, Leithauser L, Turner M, et al. The efficacy of second-intention healing in the management of defects on the dorsal surface of the hands and fingers after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:647-653. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02258.x

- Stebbins WG, Gusev J, Higgins HW 2nd, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with second intention healing versus primary surgical closure. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:865-867.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.019

Rupioid Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis in a Patient With Skin of Color

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

To the Editor:

A 49-year-old black woman presented with multiple hyperkeratotic papules that progressed over the last 2 months to circular plaques with central thick black crust resembling eschar. She first noticed these lesions as firm, small, black papules on the legs and continued to develop new lesions that eventually evolved into large, coin-shaped, hyperkeratotic plaques. Her medical history was notable for stage III non-Hodgkin follicular lymphoma in remission after treatment with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone 7 months earlier, and chronic hepatitis B infection being treated with entecavir. Her family history was not remarkable for psoriasis or inflammatory arthritis.

She initially was seen by internal medicine and was started on topical triamcinolone with no improvement of the lesions. At presentation to dermatology, physical examination revealed firm, small, black, hyperkeratotic papules (Figure 1A) and circular plaques with a rim of erythema and central thick, smooth, black crust resembling eschar (Figure 1B). No other skin changes were noted at the time. The bilateral metacarpophalangeal, bilateral proximal interphalangeal, left wrist, and bilateral ankle joints were remarkable for tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. She noted concomitant arthralgia and stiffness but denied fever. She had no other systemic symptoms including night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, malaise, sun sensitivity, oral ulcers, or hair loss. A radiograph of the hand was negative for erosive changes but showed mild periarticular osteopenia and fusiform soft tissue swelling of the third digit. Given the central appearance of eschar in the larger lesions, the initial differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, invasive fungal infection, vasculitis, and recurrent lymphoma.

A 4-mm punch biopsy specimen of a representative lesion on the right leg revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum and spinosum, elongation of the rete ridges, and superficial vascular ectasia, which favored a diagnosis of psoriasis (Figure 2). A periodic acid-Schiff stain was negative for fungal hyphae. Fungal culture, bacterial tissue culture, and acid-fast bacilli smear were negative. Absence of deep dermal inflammation precluded a diagnosis of Sweet syndrome. Further notable laboratory studies included negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis C antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

At follow-up 2 weeks later, the initial lesions were still present, and she had developed new widespread, well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silver scale along the scalp, back, chest, and abdomen that were more typical of psoriasis. Oil spots were noted on several fingernails and toenails. Based on the clinicopathologic findings, nail changes, and asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, a diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) was established. Treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to active lesions was started. Initiation of systemic therapy with a steroid-sparing agent was deferred in anticipation of care coordination with rheumatology, hepatology, and hematology/oncology due to the patient's history of follicular lymphoma and chronic hepatitis B. Although attempts were made to avoid systemic corticosteroids due to the risk for a psoriasis flare upon discontinuation, because of the severity of arthralgia she was started on oral prednisone 20 mg daily by rheumatology with plans for a slow taper once an alternative systemic agent was started.1

At 10-week follow-up, the patient had marked improvement of psoriatic plaques with no active lesions while only on prednisone 20 mg daily. In consultation with her care team, she subsequently was started on methotrexate 10 mg weekly for 2 weeks followed by titration to 15 mg weekly. Plans were to start a prednisone taper after a month of methotrexate to allow her new treatment time for therapeutic effect. Notably, the patient chose to discontinue prednisone 2 weeks into methotrexate therapy after only two 10-mg doses of methotrexate weekly and well before therapeutic levels were achieved. Despite stopping prednisone early and without a taper, she did not experience a relapse in psoriatic skin lesions. Three months following initiation of methotrexate, she sustained resolution of the cutaneous lesions with only residual postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder with multiple clinical presentations. There are several variants of psoriasis that are classified by their morphologic appearance including chronic plaque, guttate, erythrodermic, and pustular, with more than 90% of cases representing the plaque variant. Less common clinical presentations of psoriasis include rupioid, ostraceous, inverse, elephantine, and HIV associated.2 Rupioid psoriasis is a rare variant that presents with cone-shaped, limpetlike lesions.3,4 Similar to the limited epidemiological and clinical data pertaining to psoriasis in nonwhite racial groups, there also is a paucity of documented reports of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color.

Rupioid comes from the Greek word rhupos, meaning dirt or filth, and is used to describe well-demarcated lesions with thick, yellow, dirty-appearing, adherent crusts resembling oyster shells with a surrounding rim of erythema.5 Rupioid psoriasis initially was reported in 1948 and remains an uncommon and infrequently reported variant.6 The majority of reported cases have been associated with arthropathy, similar to our patient.3,4 Rupioid lesions also have been observed in an array of other diseases, such as secondary syphilis, crusted scabies, disseminated histoplasmosis, HIV, reactive arthritis, and aminoaciduria.7-11

Diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis can be confirmed with a skin biopsy, which demonstrates characteristic histopathologic findings of psoriasis.3 Laboratory analysis should be performed to rule out other causes of rupioid lesions, and PsA should be differentiated from rheumatoid arthritis if arthropathy is present. In our case, serum rapid plasma reagin, anti-HIV antibody, rheumatoid factor, and fungal cultures were negative. Usin0)g clinical findings, histopathology, laboratory analyses, and radiograph findings, the diagnosis of rupioid psoriasis with PsA was confirmed in our patient.

Psoriasis was not originally suspected in our patient due to the noncharacteristic lesions with smooth black crust--similar appearing to eschar--and the patient's complicated medical history. Variations in the presentation of psoriasis among white individuals and those with skin of color have been reported in the literature.12,13 Psoriatic lesions in darker skin tones may appear more violaceous or hyperpigmented with more conspicuous erythema and thicker plaques. Our patient lacked the classic rupioid appearance of concentric circular layers of dirty, yellow, oysterlike scale, and instead had thick, lamellate, black crust. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms rupioid, coral reef psoriasis, rupioides, and rhupus revealed no other cases of rupioid psoriasis reported in black patients and no cases detailing the variations of rupioid lesions in skin of color. A case of rupioid psoriasis has been reported in a Hispanic patient, but the described psoriatic lesions were more characteristic of the dirty-appearing, conic plaques previously reported.14 Our case highlights a unique example of the variable presentations of cutaneous disorders in skin of color and black patients.

Our patient's case of rupioid psoriasis with PsA presented unique challenges for systemic treatment due to her multiple comorbidities. Rupioid psoriasis most often is treated with combination topical and systemic therapy, with agents such as methotrexate and cyclosporine having prior success.3,4 This variant of psoriasis is highly responsive to treatment, and marked improvement of lesions has been achieved with topical steroids alone with proper adherence.15 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% while a systemic agent was debated for her PsA. Although she did not have improvement with topical therapy alone, she experienced rapid resolution of the skin lesions after initiation of low-dose prednisone 20 mg daily. Interestingly, our patient did not experience a flare of the skin lesions upon discontinuation of systemic steroids despite the lack of an appropriate taper and methotrexate not having reached therapeutic levels.

The clinical nuances of rupioid psoriasis in skin of color have not yet been described and remain an important diagnostic consideration. Our patient achieved remission of skin lesions with sequential treatment of topical clobetasol, a low-dose systemic steroid, and methotrexate. Based on available reports, rupioid psoriasis may represent a variant of psoriasis that is highly responsive to treatment.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

- Mrowietz U, Domm S. Systemic steroids in the treatment of psoriasis: what is fact, what is fiction? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1022-1025.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, eds. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012.

- Wang JL, Yang JH. Rupioid psoriasis associated with arthropathy. J Dermatol. 1997;24:46-49.

- Murakami T, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H. Rupioid psoriasis with arthropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:409-412.

- Chung HJ, Marley-Kemp D, Keller M. Rupioid psoriasis and other skin diseases with rupioid manifestations. Cutis. 2014;94:119-121.

- Salamon M, Omulecki A, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, et al. Psoriasisrupioides: a rare variant of a common disease. Cutis. 2011;88:135-137.

- Krase IZ, Cavanaugh K, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. A case of rupioid syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:141-143.

- Garofalo V, Saraceno R, Milana M, et al. Crusted scabies in a liver transplant patient mimicking rupioid psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26:495-496.

- Corti M, Villafane MF, Palmieri O, et al. Rupioid histoplasmosis: first case reported in an AIDS patient in Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2010;52:279-280.

- Sehgal VN, Koranne RV, Shyam Prasad AL. Unusual manifestations of Reiter's disease in a child. Dermatologica. 1985;170:77-79.

- Haim S, Gilhar A, Cohen A. Cutaneous manifestations associated with aminoaciduria. report of two cases. Dermatologica. 1978;156:244-250.

- McMichael AJ, Vachiramon V, Guzman-Sanchez DA, et al. Psoriasis in African-Americans: a caregivers' survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:478-482.

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Posligua A, Maldonado C, Gonzalez MG. Rupioid psoriasis preceded by varicella presenting as Koebner phenomenon. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5 suppl 1):AB268.

- Feldman SR, Feldman S, Brown K, et al. "Coral reef" psoriasis: a marker of resistance to topical treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:257-258.

Practice Points

- Rupioid psoriasis in skin of color may present a diagnostic challenge for health care providers.

- Rupioid psoriasis may represent a psoriasis variant that is highly responsive to treatment.

9 Tips to Help Prevent Derm Biopsy Mistakes

1. CHOOSE YOUR BIOPSY TYPE WISELY

Using the appropriate type of biopsy can have the greatest effect on a proper diagnosis. The decision of which biopsy type to use is not always easy. The most common biopsy types are shave, punch, excisional, and curettage. Several reference articles detail each type of biopsy commonly used in primary care and how to perform them.1,2

Each type of biopsy has inherent advantages and disadvantages. In general, the shave biopsy is most commonly used for lesions that are solitary and elevated and give the impression that a sufficient amount of tissue can be sampled with this technique. The punch biopsy is the best choice for most “rashes” (inflammatory skin disorders).2 Excisional biopsy is used to remove melanocytic neoplasms or larger lesions. And curettage, while still used by some clinicians for melanocytic lesions because of its speed and simplicity, should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes.

Each technique is described in greater detail in the tips that follow.

Continue for tip #2 >>

2. WHEN PERFORMING A SHAVE BIOPSY, AVOID OBTAINING A SAMPLE THAT'S TOO SUPERFICIAL

The advantage of the shave biopsy is that it is minimally invasive and quick to perform. If kept small without compromising the amount of sample retrieved, the scars left by shave biopsies have the potential to blend well. The major disadvantage associated with the shave biopsy is that occasionally, if the shave is not deep enough, an insufficient amount of tissue is obtained. This can make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Balancing the need to obtain adequate tissue with the desire to minimize scarring takes skill and experience. Taking a biopsy that is inadequate is a common occurrence. At times, the clinician’s clinical impression may be that a biopsy has obtained adequate tissue, when histologically only the superficial part of the skin surface has been sampled. This often is because of thickening of the superficial skin, whether as a manifestation of the anatomic site (eg, acral skin) or the disease process itself.

Unfortunately, this superficial skin often is nondiagnostic when unaccompanied by underlying epidermis and dermis. It is important to keep this in mind when you are obtaining a skin biopsy, especially when dealing with lesions that are very scaly or keratinized.

An equivocal biopsy wastes time, energy, and money, and it can negatively impact patient care.3 It can be difficult to balance practical aspects of the biopsy (ie, optimizing cosmetic outcomes, minimizing scarring and wound size) with the need to obtain sufficient tissue sampling (see Figure 1).

3. CHOOSE PUNCH OVER SHAVE BIOPSY FOR RASHES

In a punch biopsy, a disposable metal cylinder with a sharpened edge is used to “punch” out a piece of skin that can be examined under the microscope. Punch biopsy is the preferred technique for almost all inflammatory skin conditions (rashes) because the pathologist is able to examine both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis (see Figure 2).4

Pathologists use the pattern of inflammation, in conjunction with epidermal changes, to distinguish different types of inflammatory processes. For example, lichen planus is typically associated with superficial inflammation, while lupus is known to have prominent superficial and deep inflammation.

An inadequate punch biopsy sample can hinder histologic assessment of inflammatory skin disorders that involve both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis and can make arriving at a definitive diagnosis more challenging. The diameter of a punch cylinder ranges from 1 to 8 mm. Smaller punch biopsies often create diagnostic challenges because they provide so little sample. A punch biopsy size of 4 mm is commonly used for rashes.

An advantage of the punch biopsy is that patients are left with linear scars rather than the round, potentially dyspigmented (darker or lighter) scars that are often associated with shave biopsy. A well-sutured punch biopsy can be cosmetically elegant, particularly if closure is oriented along relaxed skin tension lines. For this reason, punch biopsies are well suited for cosmetically sensitive locations (eg, the face), although shave biopsies are also often performed on the face.

Next page: Tip #4 >>

4. CHOOSE AN EXCISIONAL BIOPSY FOR A MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASM, WHEN POSSIBLE

The purpose of an excisional biopsy (which typically includes a 1- to 3-mm rim of normal skin around the lesion) is to completely remove a lesion. Excisional biopsy generally is the preferred technique for clinically atypical melanocytic neoplasms (ie, lesions that are not definitively benign).4-8

When suspicion for melanoma is high, excisional biopsies should be performed with minimal undermining to preserve the accuracy of any future sentinel lymph node biopsy surgeries. Excisional biopsy is the most involved type of biopsy and has the largest potential for cosmetic disfigurement if not properly planned and performed. While guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology state that “narrow excisional biopsy that encompasses [the] entire breadth of lesion with clinically negative margins to ensure that the lesion is not transected” is preferred, they also acknowledge that partial sampling (incisional biopsy) is acceptable in select clinical circumstances,9 such as when a lesion is large or on a cosmetically sensitive site (eg, the face).10

While a larger punch biopsy (6 or 8 mm) or even deep shave/saucerization may function as an excisional biopsy for very small lesions, this approach can be problematic. For one thing, these techniques are more likely than an excisional biopsy to leave a portion of the lesion in situ. Another concern is that a shave biopsy of a melanocytic lesion can lead to error or difficulty in obtaining the correct diagnosis on later biopsy.11 For pathologists, small or incomplete samples make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.12 Among melanomas seen at a tertiary referral center, histopathologic misdiagnosis was more common with a punch or shave biopsy than with an excisional biopsy.9

It has been shown that partial biopsy for melanoma results in more residual disease at wide local excision and makes it more challenging to properly stage the lesion.13,14 If a shave biopsy is used to sample a suspected melanocytic neoplasm, it is imperative to document the specific site of the biopsy, indicate the size of the melanocytic lesion on the pathology requisition form, and ensure that all (or nearly all) of the clinically evident lesion is sampled. Detailing the location of the lesion in the chart is not only essential in evaluating the present lesion, but it will serve you well in the future. Without knowing the patient’s clinical history, benign nevi that recur after a prior biopsy can be difficult to histologically distinguish from melanoma (see Figure 3). For more on this, see tip #7.

5. BE CAREFUL WITH CURETTAGE

Curettage is a biopsy technique in which a curette—a surgical tool with a scoop, ring, or loop at the tip—is used in a scraping motion to retrieve tissue from the patient. This type of biopsy often produces a fragmented tissue sample. Its continued use reflects the speed and simplicity with which it can be done. However, curettage destroys the architecture of the tissue of the lesion, which can make it difficult to establish a proper diagnosis, and therefore it is best avoided when performing a biopsy of a melanocytic lesion (see Figure 4).

Continue for tip #6 >>

6. REMEMBER THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPER FIXATION AND PROCESSING

As obvious as it may sound, it is important to remember to promptly place sampled tissue in an adequate amount of formalin so that the tissue is submersed in it in the container.15 Failure to do so can result in improper fixation and will make it difficult to render an appropriate diagnosis. Conventionally, a 10:1 formalin-volume-to-tissue-volume ratio is recommended. If the “cold time”—the amount of time a tissue sample is out of formalin—is too long (> a few hours), an appropriate assessment can be impossible.