User login

Imiquimod-Induced Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus–like Changes

Drug-induced lupus accounts for up to 10% of lupus erythematosus cases. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a distinct clinical variant of lupus erythematosus that typically presents as annular, often scaly, erythematous plaques in photodistributed areas. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported in association with multiple systemic medications including docetaxel, terbinafine, leuprolide acetate, etanercept, and efalizumab1-5; however, the induction of SCLE by topical agents has not been widely reported. We report a case of local induction of lesions that clinically and histologically resembled SCLE in a 50-year-old woman following treatment with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with an adverse inflammatory reaction on the right side of the upper chest secondary to application of topical imiquimod. Prior to the current presentation the patient was diagnosed with a biopsy-proven superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on the sun-exposed area of the upper right breast, and topical imiquimod therapy was initiated. Several days after starting treatment, the patient began applying imiquimod on areas of clinically normal skin on the upper chest as advised by her dermatologist. After 7 to 10 days of application the patient reported intense erythema, pain, and crusting in the treated area on the right side of the upper chest. She also experienced systemic symptoms including fatigue, arthralgia, malaise, and fever.

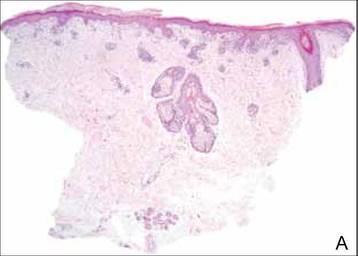

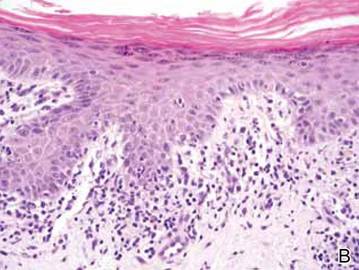

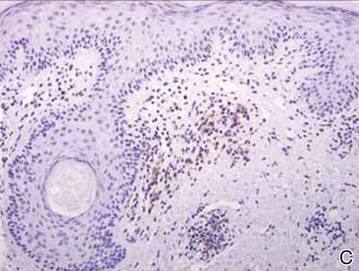

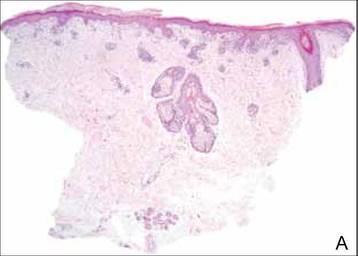

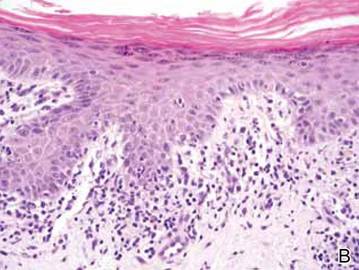

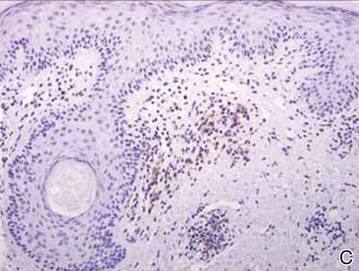

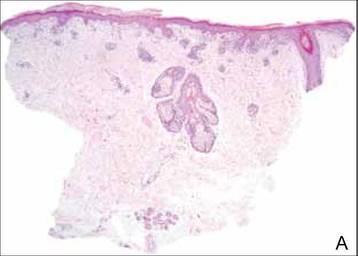

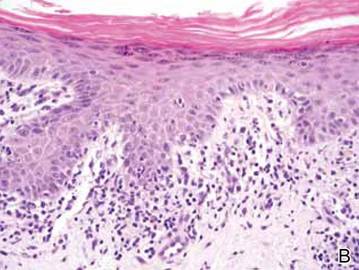

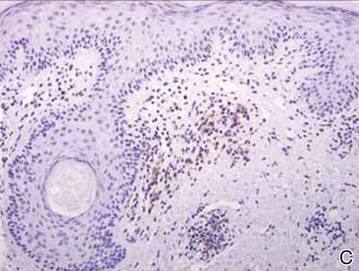

Clinical examination revealed erythematous to violaceous annular and polycyclic plaques on the upper chest (Figure 1). Erythema and scaling were noted at the site of the superficial BCC. A biopsy showed a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate with overlying vacuolar interface dermatitis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figures 2A and 2B). There was slightly increased dermal edema and mucin. Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) accompanying lymphocytes around dermal vessels and adnexa (Figure 2C). The patient’s family history was remarkable for SCLE in her daughter. Antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro (Sjögren syndrome antigen A), and anti-La (Sjögren syndrome antigen B) were negative. On follow-up examination 1 month after discontinuation of imiquimod, the patient’s skin lesions had completely cleared. Two years later, the patient continued to be free of skin lesions.

Figure 1. Annular plaques on the upper chest with overlying scale and focal central clearing.  | ||

Figure 2. Vacuolar interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with accompanying lymphocytes centered around dermal vessels and adnexa (C)(original magnification ×200). | ||

Comment

Imiquimod is a topical immunomodulator used for the treatment of genital warts and cutaneous malignancies. It exerts its effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-a, tumor necrosis factor a [TNF-α]) through activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 7, an intracytoplasmic receptor that is found on several cell types including pDCs and B cells. When the cell surface receptor is bound by activating ligands (eg, single-stranded RNA, imiquimod), downstream signaling is initiated, resulting in the production of large amounts of IFN-a and TNF-α.6,7 Both IFN-a and TNF-α are upregulated in patient serum and lesional skin in SCLE.8,9 Additionally, pDCs have been shown to accumulate in lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) in a distinct dermal pattern, as demonstrated by CD123 staining.9,10 This pattern is identical to the one seen in our case. Although pDCs also are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions, the pattern is distinct from CLE.10 These findings indicate that IFN-a produced by pDCs may play an integral role in the pathogenesis of CLE. Several observations implicating TLR signaling in the pathogenesis of lupus have been described. In a lupus-prone mouse model of lupus erythematosus, transgenic overexpression of TLR-7 resulted in increased severity of clinical disease and accelerated mortality. Antimalarials improve lupus erythematosus via blockade of TLR-7 and TLR-9 signaling.11

Imiquimod, which acts as an inducer of IFN-α expression through TLR-7 signaling, may have been an inciting factor in the development of SCLE-like lesions in this genetically predisposed patient. Histopathology of cutaneous malignancies treated with topical imiquimod typically does not show lupuslike features.12 It is possible that a subset of predisposed patients have increased numbers of pDCs primed in their skin or that they exhibit a more robust TLR-7 reaction to imiquimod, resulting in abundant IFN-a production. Other autoimmune diseases, such as pemphigus foliaceus and vitiligo, also have been reported to occur locally after the application of imiquimod,13,14 which suggests that a localized autoimmune reaction can be induced by activation of TLR-7; however, a case of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp improving after treatment with imiquimod has been reported.15

The use of imiquimod in patients with a personal or family history of lupus erythematosus or those with a personal history of an autoimmune blistering disorder should be undertaken with caution until more is known.

1. Chen M, Crowson AN, Woofter M, et al. Docetaxel (taxotere) induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 4 cases. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:818-820.

2. Farhi D, Viguier M, Cosnes A, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2006;212:59-65.

3. Wiechert A, Tüting T, Bieber T, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a leuprorelin-treated patient with prostate carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:231-233.

4. Bleumink GS, ter Borg EJ, Ramselaar CG, et al. Etanercept-induced subcutaneous lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:1317-1319.

5. Bentley DD, Graves JE, Smith DI, et al. Efalizumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S242-S243.

6. Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:823-835.

7. Hurwitz DJ, Pincus L, Kupper TS. Imiquimod: a topically applied link between innate and acquired immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1347-1350.

8. Zampieri S, Alaibac M, Iaccarino L, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha is expressed in refractory skin lesions from patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:545-548.

9. Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon-alpha/beta-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:237-243.

10. McNiff JM, Kaplan DH. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions in a pattern distinct from lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:452-456.

11. Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669-1672.

12. Wolf IH, Kodama K, Cerroni L, et al. Nature of inflammatory infiltrate in superficial cutaneous malignancies during topical imiquimod treatment. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:237-241.

13. Lin R, Ladd DJ Jr, Powell DJ, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus induced by topical imiquimod treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:889-890.

14. Brown T, Zirvi M, Cotsarelis G, et al. Vitiligo-like hypopigmentation associated with imiquimod treatment of genital warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:715-716.

15. Gersden R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Successful treatment of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp with imiquimod. Dermatology. 2002;205:416-418.

Drug-induced lupus accounts for up to 10% of lupus erythematosus cases. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a distinct clinical variant of lupus erythematosus that typically presents as annular, often scaly, erythematous plaques in photodistributed areas. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported in association with multiple systemic medications including docetaxel, terbinafine, leuprolide acetate, etanercept, and efalizumab1-5; however, the induction of SCLE by topical agents has not been widely reported. We report a case of local induction of lesions that clinically and histologically resembled SCLE in a 50-year-old woman following treatment with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with an adverse inflammatory reaction on the right side of the upper chest secondary to application of topical imiquimod. Prior to the current presentation the patient was diagnosed with a biopsy-proven superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on the sun-exposed area of the upper right breast, and topical imiquimod therapy was initiated. Several days after starting treatment, the patient began applying imiquimod on areas of clinically normal skin on the upper chest as advised by her dermatologist. After 7 to 10 days of application the patient reported intense erythema, pain, and crusting in the treated area on the right side of the upper chest. She also experienced systemic symptoms including fatigue, arthralgia, malaise, and fever.

Clinical examination revealed erythematous to violaceous annular and polycyclic plaques on the upper chest (Figure 1). Erythema and scaling were noted at the site of the superficial BCC. A biopsy showed a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate with overlying vacuolar interface dermatitis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figures 2A and 2B). There was slightly increased dermal edema and mucin. Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) accompanying lymphocytes around dermal vessels and adnexa (Figure 2C). The patient’s family history was remarkable for SCLE in her daughter. Antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro (Sjögren syndrome antigen A), and anti-La (Sjögren syndrome antigen B) were negative. On follow-up examination 1 month after discontinuation of imiquimod, the patient’s skin lesions had completely cleared. Two years later, the patient continued to be free of skin lesions.

Figure 1. Annular plaques on the upper chest with overlying scale and focal central clearing.  | ||

Figure 2. Vacuolar interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with accompanying lymphocytes centered around dermal vessels and adnexa (C)(original magnification ×200). | ||

Comment

Imiquimod is a topical immunomodulator used for the treatment of genital warts and cutaneous malignancies. It exerts its effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-a, tumor necrosis factor a [TNF-α]) through activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 7, an intracytoplasmic receptor that is found on several cell types including pDCs and B cells. When the cell surface receptor is bound by activating ligands (eg, single-stranded RNA, imiquimod), downstream signaling is initiated, resulting in the production of large amounts of IFN-a and TNF-α.6,7 Both IFN-a and TNF-α are upregulated in patient serum and lesional skin in SCLE.8,9 Additionally, pDCs have been shown to accumulate in lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) in a distinct dermal pattern, as demonstrated by CD123 staining.9,10 This pattern is identical to the one seen in our case. Although pDCs also are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions, the pattern is distinct from CLE.10 These findings indicate that IFN-a produced by pDCs may play an integral role in the pathogenesis of CLE. Several observations implicating TLR signaling in the pathogenesis of lupus have been described. In a lupus-prone mouse model of lupus erythematosus, transgenic overexpression of TLR-7 resulted in increased severity of clinical disease and accelerated mortality. Antimalarials improve lupus erythematosus via blockade of TLR-7 and TLR-9 signaling.11

Imiquimod, which acts as an inducer of IFN-α expression through TLR-7 signaling, may have been an inciting factor in the development of SCLE-like lesions in this genetically predisposed patient. Histopathology of cutaneous malignancies treated with topical imiquimod typically does not show lupuslike features.12 It is possible that a subset of predisposed patients have increased numbers of pDCs primed in their skin or that they exhibit a more robust TLR-7 reaction to imiquimod, resulting in abundant IFN-a production. Other autoimmune diseases, such as pemphigus foliaceus and vitiligo, also have been reported to occur locally after the application of imiquimod,13,14 which suggests that a localized autoimmune reaction can be induced by activation of TLR-7; however, a case of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp improving after treatment with imiquimod has been reported.15

The use of imiquimod in patients with a personal or family history of lupus erythematosus or those with a personal history of an autoimmune blistering disorder should be undertaken with caution until more is known.

Drug-induced lupus accounts for up to 10% of lupus erythematosus cases. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is a distinct clinical variant of lupus erythematosus that typically presents as annular, often scaly, erythematous plaques in photodistributed areas. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported in association with multiple systemic medications including docetaxel, terbinafine, leuprolide acetate, etanercept, and efalizumab1-5; however, the induction of SCLE by topical agents has not been widely reported. We report a case of local induction of lesions that clinically and histologically resembled SCLE in a 50-year-old woman following treatment with topical imiquimod.

Case Report

A 50-year-old woman presented with an adverse inflammatory reaction on the right side of the upper chest secondary to application of topical imiquimod. Prior to the current presentation the patient was diagnosed with a biopsy-proven superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on the sun-exposed area of the upper right breast, and topical imiquimod therapy was initiated. Several days after starting treatment, the patient began applying imiquimod on areas of clinically normal skin on the upper chest as advised by her dermatologist. After 7 to 10 days of application the patient reported intense erythema, pain, and crusting in the treated area on the right side of the upper chest. She also experienced systemic symptoms including fatigue, arthralgia, malaise, and fever.

Clinical examination revealed erythematous to violaceous annular and polycyclic plaques on the upper chest (Figure 1). Erythema and scaling were noted at the site of the superficial BCC. A biopsy showed a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate with overlying vacuolar interface dermatitis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figures 2A and 2B). There was slightly increased dermal edema and mucin. Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) accompanying lymphocytes around dermal vessels and adnexa (Figure 2C). The patient’s family history was remarkable for SCLE in her daughter. Antinuclear antibody, anti-Ro (Sjögren syndrome antigen A), and anti-La (Sjögren syndrome antigen B) were negative. On follow-up examination 1 month after discontinuation of imiquimod, the patient’s skin lesions had completely cleared. Two years later, the patient continued to be free of skin lesions.

Figure 1. Annular plaques on the upper chest with overlying scale and focal central clearing.  | ||

Figure 2. Vacuolar interface dermatitis with a perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate (A)(H&E, original magnification ×40). Scattered necrotic keratinocytes were evident (B)(H&E, original magnification ×400). Anti-CD123 immunohistochemical staining revealed nodular aggregates of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with accompanying lymphocytes centered around dermal vessels and adnexa (C)(original magnification ×200). | ||

Comment

Imiquimod is a topical immunomodulator used for the treatment of genital warts and cutaneous malignancies. It exerts its effect via induction of proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IFN-a, tumor necrosis factor a [TNF-α]) through activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 7, an intracytoplasmic receptor that is found on several cell types including pDCs and B cells. When the cell surface receptor is bound by activating ligands (eg, single-stranded RNA, imiquimod), downstream signaling is initiated, resulting in the production of large amounts of IFN-a and TNF-α.6,7 Both IFN-a and TNF-α are upregulated in patient serum and lesional skin in SCLE.8,9 Additionally, pDCs have been shown to accumulate in lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) in a distinct dermal pattern, as demonstrated by CD123 staining.9,10 This pattern is identical to the one seen in our case. Although pDCs also are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions, the pattern is distinct from CLE.10 These findings indicate that IFN-a produced by pDCs may play an integral role in the pathogenesis of CLE. Several observations implicating TLR signaling in the pathogenesis of lupus have been described. In a lupus-prone mouse model of lupus erythematosus, transgenic overexpression of TLR-7 resulted in increased severity of clinical disease and accelerated mortality. Antimalarials improve lupus erythematosus via blockade of TLR-7 and TLR-9 signaling.11

Imiquimod, which acts as an inducer of IFN-α expression through TLR-7 signaling, may have been an inciting factor in the development of SCLE-like lesions in this genetically predisposed patient. Histopathology of cutaneous malignancies treated with topical imiquimod typically does not show lupuslike features.12 It is possible that a subset of predisposed patients have increased numbers of pDCs primed in their skin or that they exhibit a more robust TLR-7 reaction to imiquimod, resulting in abundant IFN-a production. Other autoimmune diseases, such as pemphigus foliaceus and vitiligo, also have been reported to occur locally after the application of imiquimod,13,14 which suggests that a localized autoimmune reaction can be induced by activation of TLR-7; however, a case of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp improving after treatment with imiquimod has been reported.15

The use of imiquimod in patients with a personal or family history of lupus erythematosus or those with a personal history of an autoimmune blistering disorder should be undertaken with caution until more is known.

1. Chen M, Crowson AN, Woofter M, et al. Docetaxel (taxotere) induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 4 cases. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:818-820.

2. Farhi D, Viguier M, Cosnes A, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2006;212:59-65.

3. Wiechert A, Tüting T, Bieber T, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a leuprorelin-treated patient with prostate carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:231-233.

4. Bleumink GS, ter Borg EJ, Ramselaar CG, et al. Etanercept-induced subcutaneous lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:1317-1319.

5. Bentley DD, Graves JE, Smith DI, et al. Efalizumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S242-S243.

6. Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:823-835.

7. Hurwitz DJ, Pincus L, Kupper TS. Imiquimod: a topically applied link between innate and acquired immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1347-1350.

8. Zampieri S, Alaibac M, Iaccarino L, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha is expressed in refractory skin lesions from patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:545-548.

9. Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon-alpha/beta-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:237-243.

10. McNiff JM, Kaplan DH. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions in a pattern distinct from lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:452-456.

11. Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669-1672.

12. Wolf IH, Kodama K, Cerroni L, et al. Nature of inflammatory infiltrate in superficial cutaneous malignancies during topical imiquimod treatment. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:237-241.

13. Lin R, Ladd DJ Jr, Powell DJ, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus induced by topical imiquimod treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:889-890.

14. Brown T, Zirvi M, Cotsarelis G, et al. Vitiligo-like hypopigmentation associated with imiquimod treatment of genital warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:715-716.

15. Gersden R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Successful treatment of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp with imiquimod. Dermatology. 2002;205:416-418.

1. Chen M, Crowson AN, Woofter M, et al. Docetaxel (taxotere) induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: report of 4 cases. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:818-820.

2. Farhi D, Viguier M, Cosnes A, et al. Terbinafine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Dermatology. 2006;212:59-65.

3. Wiechert A, Tüting T, Bieber T, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a leuprorelin-treated patient with prostate carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:231-233.

4. Bleumink GS, ter Borg EJ, Ramselaar CG, et al. Etanercept-induced subcutaneous lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2001;40:1317-1319.

5. Bentley DD, Graves JE, Smith DI, et al. Efalizumab-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(suppl 5):S242-S243.

6. Marshak-Rothstein A. Toll-like receptors in systemic autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:823-835.

7. Hurwitz DJ, Pincus L, Kupper TS. Imiquimod: a topically applied link between innate and acquired immunity. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1347-1350.

8. Zampieri S, Alaibac M, Iaccarino L, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha is expressed in refractory skin lesions from patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:545-548.

9. Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon-alpha/beta-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:237-243.

10. McNiff JM, Kaplan DH. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions in a pattern distinct from lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:452-456.

11. Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, et al. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312:1669-1672.

12. Wolf IH, Kodama K, Cerroni L, et al. Nature of inflammatory infiltrate in superficial cutaneous malignancies during topical imiquimod treatment. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:237-241.

13. Lin R, Ladd DJ Jr, Powell DJ, et al. Localized pemphigus foliaceus induced by topical imiquimod treatment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:889-890.

14. Brown T, Zirvi M, Cotsarelis G, et al. Vitiligo-like hypopigmentation associated with imiquimod treatment of genital warts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:715-716.

15. Gersden R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Successful treatment of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus of the scalp with imiquimod. Dermatology. 2002;205:416-418.

Practice Points

- Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus has been reported in association with multiple systemic medications; however, association of this disorder with topical agents has not been widely reported.

- The use of topical imiquimod in patients with a personal or family history of lupus erythematosus should be undertaken with caution until more is known.

9 Tips to Help Prevent Derm Biopsy Mistakes

1. CHOOSE YOUR BIOPSY TYPE WISELY

Using the appropriate type of biopsy can have the greatest effect on a proper diagnosis. The decision of which biopsy type to use is not always easy. The most common biopsy types are shave, punch, excisional, and curettage. Several reference articles detail each type of biopsy commonly used in primary care and how to perform them.1,2

Each type of biopsy has inherent advantages and disadvantages. In general, the shave biopsy is most commonly used for lesions that are solitary and elevated and give the impression that a sufficient amount of tissue can be sampled with this technique. The punch biopsy is the best choice for most “rashes” (inflammatory skin disorders).2 Excisional biopsy is used to remove melanocytic neoplasms or larger lesions. And curettage, while still used by some clinicians for melanocytic lesions because of its speed and simplicity, should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes.

Each technique is described in greater detail in the tips that follow.

Continue for tip #2 >>

2. WHEN PERFORMING A SHAVE BIOPSY, AVOID OBTAINING A SAMPLE THAT'S TOO SUPERFICIAL

The advantage of the shave biopsy is that it is minimally invasive and quick to perform. If kept small without compromising the amount of sample retrieved, the scars left by shave biopsies have the potential to blend well. The major disadvantage associated with the shave biopsy is that occasionally, if the shave is not deep enough, an insufficient amount of tissue is obtained. This can make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Balancing the need to obtain adequate tissue with the desire to minimize scarring takes skill and experience. Taking a biopsy that is inadequate is a common occurrence. At times, the clinician’s clinical impression may be that a biopsy has obtained adequate tissue, when histologically only the superficial part of the skin surface has been sampled. This often is because of thickening of the superficial skin, whether as a manifestation of the anatomic site (eg, acral skin) or the disease process itself.

Unfortunately, this superficial skin often is nondiagnostic when unaccompanied by underlying epidermis and dermis. It is important to keep this in mind when you are obtaining a skin biopsy, especially when dealing with lesions that are very scaly or keratinized.

An equivocal biopsy wastes time, energy, and money, and it can negatively impact patient care.3 It can be difficult to balance practical aspects of the biopsy (ie, optimizing cosmetic outcomes, minimizing scarring and wound size) with the need to obtain sufficient tissue sampling (see Figure 1).

3. CHOOSE PUNCH OVER SHAVE BIOPSY FOR RASHES

In a punch biopsy, a disposable metal cylinder with a sharpened edge is used to “punch” out a piece of skin that can be examined under the microscope. Punch biopsy is the preferred technique for almost all inflammatory skin conditions (rashes) because the pathologist is able to examine both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis (see Figure 2).4

Pathologists use the pattern of inflammation, in conjunction with epidermal changes, to distinguish different types of inflammatory processes. For example, lichen planus is typically associated with superficial inflammation, while lupus is known to have prominent superficial and deep inflammation.

An inadequate punch biopsy sample can hinder histologic assessment of inflammatory skin disorders that involve both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis and can make arriving at a definitive diagnosis more challenging. The diameter of a punch cylinder ranges from 1 to 8 mm. Smaller punch biopsies often create diagnostic challenges because they provide so little sample. A punch biopsy size of 4 mm is commonly used for rashes.

An advantage of the punch biopsy is that patients are left with linear scars rather than the round, potentially dyspigmented (darker or lighter) scars that are often associated with shave biopsy. A well-sutured punch biopsy can be cosmetically elegant, particularly if closure is oriented along relaxed skin tension lines. For this reason, punch biopsies are well suited for cosmetically sensitive locations (eg, the face), although shave biopsies are also often performed on the face.

Next page: Tip #4 >>

4. CHOOSE AN EXCISIONAL BIOPSY FOR A MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASM, WHEN POSSIBLE

The purpose of an excisional biopsy (which typically includes a 1- to 3-mm rim of normal skin around the lesion) is to completely remove a lesion. Excisional biopsy generally is the preferred technique for clinically atypical melanocytic neoplasms (ie, lesions that are not definitively benign).4-8

When suspicion for melanoma is high, excisional biopsies should be performed with minimal undermining to preserve the accuracy of any future sentinel lymph node biopsy surgeries. Excisional biopsy is the most involved type of biopsy and has the largest potential for cosmetic disfigurement if not properly planned and performed. While guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology state that “narrow excisional biopsy that encompasses [the] entire breadth of lesion with clinically negative margins to ensure that the lesion is not transected” is preferred, they also acknowledge that partial sampling (incisional biopsy) is acceptable in select clinical circumstances,9 such as when a lesion is large or on a cosmetically sensitive site (eg, the face).10

While a larger punch biopsy (6 or 8 mm) or even deep shave/saucerization may function as an excisional biopsy for very small lesions, this approach can be problematic. For one thing, these techniques are more likely than an excisional biopsy to leave a portion of the lesion in situ. Another concern is that a shave biopsy of a melanocytic lesion can lead to error or difficulty in obtaining the correct diagnosis on later biopsy.11 For pathologists, small or incomplete samples make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.12 Among melanomas seen at a tertiary referral center, histopathologic misdiagnosis was more common with a punch or shave biopsy than with an excisional biopsy.9

It has been shown that partial biopsy for melanoma results in more residual disease at wide local excision and makes it more challenging to properly stage the lesion.13,14 If a shave biopsy is used to sample a suspected melanocytic neoplasm, it is imperative to document the specific site of the biopsy, indicate the size of the melanocytic lesion on the pathology requisition form, and ensure that all (or nearly all) of the clinically evident lesion is sampled. Detailing the location of the lesion in the chart is not only essential in evaluating the present lesion, but it will serve you well in the future. Without knowing the patient’s clinical history, benign nevi that recur after a prior biopsy can be difficult to histologically distinguish from melanoma (see Figure 3). For more on this, see tip #7.

5. BE CAREFUL WITH CURETTAGE

Curettage is a biopsy technique in which a curette—a surgical tool with a scoop, ring, or loop at the tip—is used in a scraping motion to retrieve tissue from the patient. This type of biopsy often produces a fragmented tissue sample. Its continued use reflects the speed and simplicity with which it can be done. However, curettage destroys the architecture of the tissue of the lesion, which can make it difficult to establish a proper diagnosis, and therefore it is best avoided when performing a biopsy of a melanocytic lesion (see Figure 4).

Continue for tip #6 >>

6. REMEMBER THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPER FIXATION AND PROCESSING

As obvious as it may sound, it is important to remember to promptly place sampled tissue in an adequate amount of formalin so that the tissue is submersed in it in the container.15 Failure to do so can result in improper fixation and will make it difficult to render an appropriate diagnosis. Conventionally, a 10:1 formalin-volume-to-tissue-volume ratio is recommended. If the “cold time”—the amount of time a tissue sample is out of formalin—is too long (> a few hours), an appropriate assessment can be impossible.

Appropriate fixation and fixation times are important because molecular testing is being increasingly used to make pathologic diagnoses.16 Additionally, aggressively manipulating a biopsy sample while extracting it or placing it in formalin can cause “crush” artifact, which can limit interpretability (see Figure 5).

7. PROPERLY PHOTOGRAPH AND DOCUMENT THE BIOPSY LOCATION

When performing a biopsy of a suspicious neoplasm, clinicians often remove all of the lesion’s superficial components, which means that at the patient’s follow-up appointment and subsequent treatments, only a well-healed biopsy site will remain. The biopsy site may be so well healed that it blends seamlessly into the surrounding skin and is nearly impossible for the clinician to identify. This problem is seen most often when patients present for surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.17

To properly record the site of a biopsy for future dermatologic exams, take pictures of the lesion at the time of biopsy. The photographs should clearly document the lesion in question and should be taken far enough from the site that surrounding lesions and/or other anatomic landmarks are also visible. Biangulation or triangulation (taking a series of two or three measurements, respectively, from the site of the lesion to nearby anatomic landmarks) can be used in conjunction with photographs.

When using measurements, be as specific and accurate as possible with anatomic terms. For example, measuring the distance from the “ear” is not helpful. It would be more helpful to measure the distance from the “tragus” or the “root of the helix.” Without a properly photographed and documented biopsy site, surgical treatment may need to be delayed until the location can be confirmed.

8. GIVE THE PATHOLOGIST A PERTINENT HISTORY

Providing the pathologist with a sufficient history, including the distribution and appearance of the lesion, and how long the patient has had it, can be essential in narrowing the diagnosis or making the differential diagnoses. Things like medication use or new exposures to perfumes, lotions, or plants can be especially helpful and are often overlooked when filling out the pathology requisition form.

When warranted, phone calls are helpful. You might, for example, call the pathologist and give him or her a more detailed physical examination description or additional pertinent history that was discovered after the requisition was filled out. Providing a good history can make the difference between a specific diagnosis and a broad differential.

Tip #9: Next page >>

9. KNOW WHEN TO REFER

There is no shame in asking for a second opinion when evaluating a skin lesion, especially with melanocytic neoplasms, where the stakes can be high, or skin eruptions that do not respond to conventional therapy. Remember, many cases are difficult, even for experts, and require a careful balance of clinical and histopathologic judgment.18

REFERENCES

1. Pickett H. Shave and punch biopsy for skin lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:995-1002.

2. Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Skin biopsy techniques for the internist. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:46-54.

3. Fernandez EM, Helm T, Ioffreda M, et al. The vanishing biopsy: the trend toward smaller specimens. Cutis. 2005;76:335-339.

4. Hieken TJ, Hernández-Irizarry R, Boll JM, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic biopsy for cutaneous melanoma: implications for surgical oncologists. Int J Surg Oncol. 2013;2013:196493.

5. Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, McCarthy SW, et al. Incomplete biopsy of melanocytic lesions can impair the accuracy of pathological diagnosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:71-75.

6. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Pitfalls and important issues in the pathologic diagnosis of melanocytic tumors. Ochsner J. 2010;10:66-74.

7. Swanson NA, Lee KK, Gorman A, et al. Biopsy techniques. Diagnosis of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:677-680.

8. Chang TT, Somach SC, Wagamon K, et al. The inadequacy of punch-excised melanocytic lesions: sampling through the block for the determination of “margins.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60: 990-993.

9. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

10. Pardasani AG, Leshin B, Hallman JR, et al. Fusiform incisional biopsy for pigmented skin lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:622-624.

11. King R, Hayzen BA, Page RN, et al. Recurrent nevus phenomenon: a clinicopathologic study of 357 cases and histologic comparison with melanoma with regression. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:611-617.

12. Mills JK, White I, Diggs B, et al. Effect of biopsy type on outcomes in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2013;205:585-590.

13. Stell VH, Norton HJ, Smith KS, et al. Method of biopsy and incidence of positive margins in primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:

893-898.

14. Egnatios GL, Dueck AC, Macdonald JB, et al. The impact of biopsy technique on upstaging, residual disease, and outcome in cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2011;202:771-778.

15. Ackerman AB, Boer A, Bennin B, et al. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Disease: An Algorithmic Method Based on Pattern Analysis. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2005.

16. Hewitt SM, Lewis FA, Cao Y, et al. Tissue handling and specimen preparation in surgical pathology: issues concerning the recovery of nucleic acids from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1929-1935.

17. Nemeth SA, Lawrence N. Site identification challenges in dermatologic surgery: a physician survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67: 262-268.

18. Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. A review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

1. CHOOSE YOUR BIOPSY TYPE WISELY

Using the appropriate type of biopsy can have the greatest effect on a proper diagnosis. The decision of which biopsy type to use is not always easy. The most common biopsy types are shave, punch, excisional, and curettage. Several reference articles detail each type of biopsy commonly used in primary care and how to perform them.1,2

Each type of biopsy has inherent advantages and disadvantages. In general, the shave biopsy is most commonly used for lesions that are solitary and elevated and give the impression that a sufficient amount of tissue can be sampled with this technique. The punch biopsy is the best choice for most “rashes” (inflammatory skin disorders).2 Excisional biopsy is used to remove melanocytic neoplasms or larger lesions. And curettage, while still used by some clinicians for melanocytic lesions because of its speed and simplicity, should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes.

Each technique is described in greater detail in the tips that follow.

Continue for tip #2 >>

2. WHEN PERFORMING A SHAVE BIOPSY, AVOID OBTAINING A SAMPLE THAT'S TOO SUPERFICIAL

The advantage of the shave biopsy is that it is minimally invasive and quick to perform. If kept small without compromising the amount of sample retrieved, the scars left by shave biopsies have the potential to blend well. The major disadvantage associated with the shave biopsy is that occasionally, if the shave is not deep enough, an insufficient amount of tissue is obtained. This can make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Balancing the need to obtain adequate tissue with the desire to minimize scarring takes skill and experience. Taking a biopsy that is inadequate is a common occurrence. At times, the clinician’s clinical impression may be that a biopsy has obtained adequate tissue, when histologically only the superficial part of the skin surface has been sampled. This often is because of thickening of the superficial skin, whether as a manifestation of the anatomic site (eg, acral skin) or the disease process itself.

Unfortunately, this superficial skin often is nondiagnostic when unaccompanied by underlying epidermis and dermis. It is important to keep this in mind when you are obtaining a skin biopsy, especially when dealing with lesions that are very scaly or keratinized.

An equivocal biopsy wastes time, energy, and money, and it can negatively impact patient care.3 It can be difficult to balance practical aspects of the biopsy (ie, optimizing cosmetic outcomes, minimizing scarring and wound size) with the need to obtain sufficient tissue sampling (see Figure 1).

3. CHOOSE PUNCH OVER SHAVE BIOPSY FOR RASHES

In a punch biopsy, a disposable metal cylinder with a sharpened edge is used to “punch” out a piece of skin that can be examined under the microscope. Punch biopsy is the preferred technique for almost all inflammatory skin conditions (rashes) because the pathologist is able to examine both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis (see Figure 2).4

Pathologists use the pattern of inflammation, in conjunction with epidermal changes, to distinguish different types of inflammatory processes. For example, lichen planus is typically associated with superficial inflammation, while lupus is known to have prominent superficial and deep inflammation.

An inadequate punch biopsy sample can hinder histologic assessment of inflammatory skin disorders that involve both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis and can make arriving at a definitive diagnosis more challenging. The diameter of a punch cylinder ranges from 1 to 8 mm. Smaller punch biopsies often create diagnostic challenges because they provide so little sample. A punch biopsy size of 4 mm is commonly used for rashes.

An advantage of the punch biopsy is that patients are left with linear scars rather than the round, potentially dyspigmented (darker or lighter) scars that are often associated with shave biopsy. A well-sutured punch biopsy can be cosmetically elegant, particularly if closure is oriented along relaxed skin tension lines. For this reason, punch biopsies are well suited for cosmetically sensitive locations (eg, the face), although shave biopsies are also often performed on the face.

Next page: Tip #4 >>

4. CHOOSE AN EXCISIONAL BIOPSY FOR A MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASM, WHEN POSSIBLE

The purpose of an excisional biopsy (which typically includes a 1- to 3-mm rim of normal skin around the lesion) is to completely remove a lesion. Excisional biopsy generally is the preferred technique for clinically atypical melanocytic neoplasms (ie, lesions that are not definitively benign).4-8

When suspicion for melanoma is high, excisional biopsies should be performed with minimal undermining to preserve the accuracy of any future sentinel lymph node biopsy surgeries. Excisional biopsy is the most involved type of biopsy and has the largest potential for cosmetic disfigurement if not properly planned and performed. While guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology state that “narrow excisional biopsy that encompasses [the] entire breadth of lesion with clinically negative margins to ensure that the lesion is not transected” is preferred, they also acknowledge that partial sampling (incisional biopsy) is acceptable in select clinical circumstances,9 such as when a lesion is large or on a cosmetically sensitive site (eg, the face).10

While a larger punch biopsy (6 or 8 mm) or even deep shave/saucerization may function as an excisional biopsy for very small lesions, this approach can be problematic. For one thing, these techniques are more likely than an excisional biopsy to leave a portion of the lesion in situ. Another concern is that a shave biopsy of a melanocytic lesion can lead to error or difficulty in obtaining the correct diagnosis on later biopsy.11 For pathologists, small or incomplete samples make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.12 Among melanomas seen at a tertiary referral center, histopathologic misdiagnosis was more common with a punch or shave biopsy than with an excisional biopsy.9

It has been shown that partial biopsy for melanoma results in more residual disease at wide local excision and makes it more challenging to properly stage the lesion.13,14 If a shave biopsy is used to sample a suspected melanocytic neoplasm, it is imperative to document the specific site of the biopsy, indicate the size of the melanocytic lesion on the pathology requisition form, and ensure that all (or nearly all) of the clinically evident lesion is sampled. Detailing the location of the lesion in the chart is not only essential in evaluating the present lesion, but it will serve you well in the future. Without knowing the patient’s clinical history, benign nevi that recur after a prior biopsy can be difficult to histologically distinguish from melanoma (see Figure 3). For more on this, see tip #7.

5. BE CAREFUL WITH CURETTAGE

Curettage is a biopsy technique in which a curette—a surgical tool with a scoop, ring, or loop at the tip—is used in a scraping motion to retrieve tissue from the patient. This type of biopsy often produces a fragmented tissue sample. Its continued use reflects the speed and simplicity with which it can be done. However, curettage destroys the architecture of the tissue of the lesion, which can make it difficult to establish a proper diagnosis, and therefore it is best avoided when performing a biopsy of a melanocytic lesion (see Figure 4).

Continue for tip #6 >>

6. REMEMBER THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPER FIXATION AND PROCESSING

As obvious as it may sound, it is important to remember to promptly place sampled tissue in an adequate amount of formalin so that the tissue is submersed in it in the container.15 Failure to do so can result in improper fixation and will make it difficult to render an appropriate diagnosis. Conventionally, a 10:1 formalin-volume-to-tissue-volume ratio is recommended. If the “cold time”—the amount of time a tissue sample is out of formalin—is too long (> a few hours), an appropriate assessment can be impossible.

Appropriate fixation and fixation times are important because molecular testing is being increasingly used to make pathologic diagnoses.16 Additionally, aggressively manipulating a biopsy sample while extracting it or placing it in formalin can cause “crush” artifact, which can limit interpretability (see Figure 5).

7. PROPERLY PHOTOGRAPH AND DOCUMENT THE BIOPSY LOCATION

When performing a biopsy of a suspicious neoplasm, clinicians often remove all of the lesion’s superficial components, which means that at the patient’s follow-up appointment and subsequent treatments, only a well-healed biopsy site will remain. The biopsy site may be so well healed that it blends seamlessly into the surrounding skin and is nearly impossible for the clinician to identify. This problem is seen most often when patients present for surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.17

To properly record the site of a biopsy for future dermatologic exams, take pictures of the lesion at the time of biopsy. The photographs should clearly document the lesion in question and should be taken far enough from the site that surrounding lesions and/or other anatomic landmarks are also visible. Biangulation or triangulation (taking a series of two or three measurements, respectively, from the site of the lesion to nearby anatomic landmarks) can be used in conjunction with photographs.

When using measurements, be as specific and accurate as possible with anatomic terms. For example, measuring the distance from the “ear” is not helpful. It would be more helpful to measure the distance from the “tragus” or the “root of the helix.” Without a properly photographed and documented biopsy site, surgical treatment may need to be delayed until the location can be confirmed.

8. GIVE THE PATHOLOGIST A PERTINENT HISTORY

Providing the pathologist with a sufficient history, including the distribution and appearance of the lesion, and how long the patient has had it, can be essential in narrowing the diagnosis or making the differential diagnoses. Things like medication use or new exposures to perfumes, lotions, or plants can be especially helpful and are often overlooked when filling out the pathology requisition form.

When warranted, phone calls are helpful. You might, for example, call the pathologist and give him or her a more detailed physical examination description or additional pertinent history that was discovered after the requisition was filled out. Providing a good history can make the difference between a specific diagnosis and a broad differential.

Tip #9: Next page >>

9. KNOW WHEN TO REFER

There is no shame in asking for a second opinion when evaluating a skin lesion, especially with melanocytic neoplasms, where the stakes can be high, or skin eruptions that do not respond to conventional therapy. Remember, many cases are difficult, even for experts, and require a careful balance of clinical and histopathologic judgment.18

REFERENCES

1. Pickett H. Shave and punch biopsy for skin lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:995-1002.

2. Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Skin biopsy techniques for the internist. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:46-54.

3. Fernandez EM, Helm T, Ioffreda M, et al. The vanishing biopsy: the trend toward smaller specimens. Cutis. 2005;76:335-339.

4. Hieken TJ, Hernández-Irizarry R, Boll JM, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic biopsy for cutaneous melanoma: implications for surgical oncologists. Int J Surg Oncol. 2013;2013:196493.

5. Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, McCarthy SW, et al. Incomplete biopsy of melanocytic lesions can impair the accuracy of pathological diagnosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:71-75.

6. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Pitfalls and important issues in the pathologic diagnosis of melanocytic tumors. Ochsner J. 2010;10:66-74.

7. Swanson NA, Lee KK, Gorman A, et al. Biopsy techniques. Diagnosis of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:677-680.

8. Chang TT, Somach SC, Wagamon K, et al. The inadequacy of punch-excised melanocytic lesions: sampling through the block for the determination of “margins.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60: 990-993.

9. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

10. Pardasani AG, Leshin B, Hallman JR, et al. Fusiform incisional biopsy for pigmented skin lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:622-624.

11. King R, Hayzen BA, Page RN, et al. Recurrent nevus phenomenon: a clinicopathologic study of 357 cases and histologic comparison with melanoma with regression. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:611-617.

12. Mills JK, White I, Diggs B, et al. Effect of biopsy type on outcomes in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2013;205:585-590.

13. Stell VH, Norton HJ, Smith KS, et al. Method of biopsy and incidence of positive margins in primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:

893-898.

14. Egnatios GL, Dueck AC, Macdonald JB, et al. The impact of biopsy technique on upstaging, residual disease, and outcome in cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2011;202:771-778.

15. Ackerman AB, Boer A, Bennin B, et al. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Disease: An Algorithmic Method Based on Pattern Analysis. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2005.

16. Hewitt SM, Lewis FA, Cao Y, et al. Tissue handling and specimen preparation in surgical pathology: issues concerning the recovery of nucleic acids from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1929-1935.

17. Nemeth SA, Lawrence N. Site identification challenges in dermatologic surgery: a physician survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67: 262-268.

18. Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. A review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

1. CHOOSE YOUR BIOPSY TYPE WISELY

Using the appropriate type of biopsy can have the greatest effect on a proper diagnosis. The decision of which biopsy type to use is not always easy. The most common biopsy types are shave, punch, excisional, and curettage. Several reference articles detail each type of biopsy commonly used in primary care and how to perform them.1,2

Each type of biopsy has inherent advantages and disadvantages. In general, the shave biopsy is most commonly used for lesions that are solitary and elevated and give the impression that a sufficient amount of tissue can be sampled with this technique. The punch biopsy is the best choice for most “rashes” (inflammatory skin disorders).2 Excisional biopsy is used to remove melanocytic neoplasms or larger lesions. And curettage, while still used by some clinicians for melanocytic lesions because of its speed and simplicity, should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes.

Each technique is described in greater detail in the tips that follow.

Continue for tip #2 >>

2. WHEN PERFORMING A SHAVE BIOPSY, AVOID OBTAINING A SAMPLE THAT'S TOO SUPERFICIAL

The advantage of the shave biopsy is that it is minimally invasive and quick to perform. If kept small without compromising the amount of sample retrieved, the scars left by shave biopsies have the potential to blend well. The major disadvantage associated with the shave biopsy is that occasionally, if the shave is not deep enough, an insufficient amount of tissue is obtained. This can make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Balancing the need to obtain adequate tissue with the desire to minimize scarring takes skill and experience. Taking a biopsy that is inadequate is a common occurrence. At times, the clinician’s clinical impression may be that a biopsy has obtained adequate tissue, when histologically only the superficial part of the skin surface has been sampled. This often is because of thickening of the superficial skin, whether as a manifestation of the anatomic site (eg, acral skin) or the disease process itself.

Unfortunately, this superficial skin often is nondiagnostic when unaccompanied by underlying epidermis and dermis. It is important to keep this in mind when you are obtaining a skin biopsy, especially when dealing with lesions that are very scaly or keratinized.

An equivocal biopsy wastes time, energy, and money, and it can negatively impact patient care.3 It can be difficult to balance practical aspects of the biopsy (ie, optimizing cosmetic outcomes, minimizing scarring and wound size) with the need to obtain sufficient tissue sampling (see Figure 1).

3. CHOOSE PUNCH OVER SHAVE BIOPSY FOR RASHES

In a punch biopsy, a disposable metal cylinder with a sharpened edge is used to “punch” out a piece of skin that can be examined under the microscope. Punch biopsy is the preferred technique for almost all inflammatory skin conditions (rashes) because the pathologist is able to examine both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis (see Figure 2).4

Pathologists use the pattern of inflammation, in conjunction with epidermal changes, to distinguish different types of inflammatory processes. For example, lichen planus is typically associated with superficial inflammation, while lupus is known to have prominent superficial and deep inflammation.

An inadequate punch biopsy sample can hinder histologic assessment of inflammatory skin disorders that involve both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis and can make arriving at a definitive diagnosis more challenging. The diameter of a punch cylinder ranges from 1 to 8 mm. Smaller punch biopsies often create diagnostic challenges because they provide so little sample. A punch biopsy size of 4 mm is commonly used for rashes.

An advantage of the punch biopsy is that patients are left with linear scars rather than the round, potentially dyspigmented (darker or lighter) scars that are often associated with shave biopsy. A well-sutured punch biopsy can be cosmetically elegant, particularly if closure is oriented along relaxed skin tension lines. For this reason, punch biopsies are well suited for cosmetically sensitive locations (eg, the face), although shave biopsies are also often performed on the face.

Next page: Tip #4 >>

4. CHOOSE AN EXCISIONAL BIOPSY FOR A MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASM, WHEN POSSIBLE

The purpose of an excisional biopsy (which typically includes a 1- to 3-mm rim of normal skin around the lesion) is to completely remove a lesion. Excisional biopsy generally is the preferred technique for clinically atypical melanocytic neoplasms (ie, lesions that are not definitively benign).4-8

When suspicion for melanoma is high, excisional biopsies should be performed with minimal undermining to preserve the accuracy of any future sentinel lymph node biopsy surgeries. Excisional biopsy is the most involved type of biopsy and has the largest potential for cosmetic disfigurement if not properly planned and performed. While guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology state that “narrow excisional biopsy that encompasses [the] entire breadth of lesion with clinically negative margins to ensure that the lesion is not transected” is preferred, they also acknowledge that partial sampling (incisional biopsy) is acceptable in select clinical circumstances,9 such as when a lesion is large or on a cosmetically sensitive site (eg, the face).10

While a larger punch biopsy (6 or 8 mm) or even deep shave/saucerization may function as an excisional biopsy for very small lesions, this approach can be problematic. For one thing, these techniques are more likely than an excisional biopsy to leave a portion of the lesion in situ. Another concern is that a shave biopsy of a melanocytic lesion can lead to error or difficulty in obtaining the correct diagnosis on later biopsy.11 For pathologists, small or incomplete samples make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.12 Among melanomas seen at a tertiary referral center, histopathologic misdiagnosis was more common with a punch or shave biopsy than with an excisional biopsy.9

It has been shown that partial biopsy for melanoma results in more residual disease at wide local excision and makes it more challenging to properly stage the lesion.13,14 If a shave biopsy is used to sample a suspected melanocytic neoplasm, it is imperative to document the specific site of the biopsy, indicate the size of the melanocytic lesion on the pathology requisition form, and ensure that all (or nearly all) of the clinically evident lesion is sampled. Detailing the location of the lesion in the chart is not only essential in evaluating the present lesion, but it will serve you well in the future. Without knowing the patient’s clinical history, benign nevi that recur after a prior biopsy can be difficult to histologically distinguish from melanoma (see Figure 3). For more on this, see tip #7.

5. BE CAREFUL WITH CURETTAGE

Curettage is a biopsy technique in which a curette—a surgical tool with a scoop, ring, or loop at the tip—is used in a scraping motion to retrieve tissue from the patient. This type of biopsy often produces a fragmented tissue sample. Its continued use reflects the speed and simplicity with which it can be done. However, curettage destroys the architecture of the tissue of the lesion, which can make it difficult to establish a proper diagnosis, and therefore it is best avoided when performing a biopsy of a melanocytic lesion (see Figure 4).

Continue for tip #6 >>

6. REMEMBER THE IMPORTANCE OF PROPER FIXATION AND PROCESSING

As obvious as it may sound, it is important to remember to promptly place sampled tissue in an adequate amount of formalin so that the tissue is submersed in it in the container.15 Failure to do so can result in improper fixation and will make it difficult to render an appropriate diagnosis. Conventionally, a 10:1 formalin-volume-to-tissue-volume ratio is recommended. If the “cold time”—the amount of time a tissue sample is out of formalin—is too long (> a few hours), an appropriate assessment can be impossible.

Appropriate fixation and fixation times are important because molecular testing is being increasingly used to make pathologic diagnoses.16 Additionally, aggressively manipulating a biopsy sample while extracting it or placing it in formalin can cause “crush” artifact, which can limit interpretability (see Figure 5).

7. PROPERLY PHOTOGRAPH AND DOCUMENT THE BIOPSY LOCATION

When performing a biopsy of a suspicious neoplasm, clinicians often remove all of the lesion’s superficial components, which means that at the patient’s follow-up appointment and subsequent treatments, only a well-healed biopsy site will remain. The biopsy site may be so well healed that it blends seamlessly into the surrounding skin and is nearly impossible for the clinician to identify. This problem is seen most often when patients present for surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.17

To properly record the site of a biopsy for future dermatologic exams, take pictures of the lesion at the time of biopsy. The photographs should clearly document the lesion in question and should be taken far enough from the site that surrounding lesions and/or other anatomic landmarks are also visible. Biangulation or triangulation (taking a series of two or three measurements, respectively, from the site of the lesion to nearby anatomic landmarks) can be used in conjunction with photographs.

When using measurements, be as specific and accurate as possible with anatomic terms. For example, measuring the distance from the “ear” is not helpful. It would be more helpful to measure the distance from the “tragus” or the “root of the helix.” Without a properly photographed and documented biopsy site, surgical treatment may need to be delayed until the location can be confirmed.

8. GIVE THE PATHOLOGIST A PERTINENT HISTORY

Providing the pathologist with a sufficient history, including the distribution and appearance of the lesion, and how long the patient has had it, can be essential in narrowing the diagnosis or making the differential diagnoses. Things like medication use or new exposures to perfumes, lotions, or plants can be especially helpful and are often overlooked when filling out the pathology requisition form.

When warranted, phone calls are helpful. You might, for example, call the pathologist and give him or her a more detailed physical examination description or additional pertinent history that was discovered after the requisition was filled out. Providing a good history can make the difference between a specific diagnosis and a broad differential.

Tip #9: Next page >>

9. KNOW WHEN TO REFER

There is no shame in asking for a second opinion when evaluating a skin lesion, especially with melanocytic neoplasms, where the stakes can be high, or skin eruptions that do not respond to conventional therapy. Remember, many cases are difficult, even for experts, and require a careful balance of clinical and histopathologic judgment.18

REFERENCES

1. Pickett H. Shave and punch biopsy for skin lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:995-1002.

2. Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Skin biopsy techniques for the internist. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:46-54.

3. Fernandez EM, Helm T, Ioffreda M, et al. The vanishing biopsy: the trend toward smaller specimens. Cutis. 2005;76:335-339.

4. Hieken TJ, Hernández-Irizarry R, Boll JM, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic biopsy for cutaneous melanoma: implications for surgical oncologists. Int J Surg Oncol. 2013;2013:196493.

5. Scolyer RA, Thompson JF, McCarthy SW, et al. Incomplete biopsy of melanocytic lesions can impair the accuracy of pathological diagnosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2006;47:71-75.

6. McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Pitfalls and important issues in the pathologic diagnosis of melanocytic tumors. Ochsner J. 2010;10:66-74.

7. Swanson NA, Lee KK, Gorman A, et al. Biopsy techniques. Diagnosis of melanoma. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:677-680.

8. Chang TT, Somach SC, Wagamon K, et al. The inadequacy of punch-excised melanocytic lesions: sampling through the block for the determination of “margins.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60: 990-993.

9. Bichakjian CK, Halpern AC, Johnson TM, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1032-1047.

10. Pardasani AG, Leshin B, Hallman JR, et al. Fusiform incisional biopsy for pigmented skin lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:622-624.

11. King R, Hayzen BA, Page RN, et al. Recurrent nevus phenomenon: a clinicopathologic study of 357 cases and histologic comparison with melanoma with regression. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:611-617.

12. Mills JK, White I, Diggs B, et al. Effect of biopsy type on outcomes in the treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2013;205:585-590.

13. Stell VH, Norton HJ, Smith KS, et al. Method of biopsy and incidence of positive margins in primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:

893-898.

14. Egnatios GL, Dueck AC, Macdonald JB, et al. The impact of biopsy technique on upstaging, residual disease, and outcome in cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg. 2011;202:771-778.

15. Ackerman AB, Boer A, Bennin B, et al. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Disease: An Algorithmic Method Based on Pattern Analysis. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2005.

16. Hewitt SM, Lewis FA, Cao Y, et al. Tissue handling and specimen preparation in surgical pathology: issues concerning the recovery of nucleic acids from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1929-1935.

17. Nemeth SA, Lawrence N. Site identification challenges in dermatologic surgery: a physician survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67: 262-268.

18. Federman DG, Concato J, Kirsner RS. Comparison of dermatologic diagnoses by primary care practitioners and dermatologists. A review of the literature. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:170-172.

9 tips to help prevent derm biopsy mistakes

› Use an excisional biopsy for a melanocytic neoplasm. C

› Choose a punch biopsy over a shave biopsy for rashes. B

› Properly photograph and document the location of all lesions before biopsy. A

› Provide the pathologist with a sufficient history, including the distribution and appearance of the lesion, and how long the patient has had it. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Most physicians do a satisfactory job in choosing when and how to do a skin biopsy, but there is always room for improvement. The 9 pointers we provide here are based on standard of care practices and literature when available, and also on our collective experiences as a pathologist/dermatologist (JM), dermatopathologist (DZ), primary care physician (BR), and dermatologist/Mohs surgeon (EB).

1. Choose your biopsy type wisely.

Using the appropriate type of biopsy can have the greatest effect on a proper diagnosis. The decision of which biopsy type to use is not always easy. The most common biopsy types are shave, punch, excisional, and curettage. Several reference articles detail each type of biopsy commonly used in primary care and how to perform them.1,2 (For a series of how-to videos that illustrate how to perform some of these biopsies, visit The Journal of Family Practice Multimedia Library at http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Each type of biopsy has inherent advantages and disadvantages. In general, the shave biopsy is most commonly used for lesions that are solitary, elevated, and give the impression that a sufficient amount of tissue can be sampled using this technique. The punch biopsy is the biopsy of choice for most “rashes” (inflammatory skin disorders).2 Excisional biopsy is used to remove melanocytic neoplasms or larger lesions. And curettage, while still used by some clinicians for melanocytic lesions because of its speed and simplicity, should almost never be used for diagnostic purposes. Each of these techniques is described in greater detail in the tips that follow.

2. When performing a shave biopsy, avoid obtaining a sample that's too superficial.

The advantage of the shave biopsy is that it is minimally invasive and quick to perform. If kept small while not compromising the amount of sample retrieved, the scars left by shave biopsies have the potential to blend well. The major disadvantage of the shave biopsy is that occasionally, if the shave is not deep enough, an insufficient amount of tissue is obtained, which can make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Balancing the need to obtain adequate tissue while minimizing scarring takes skill and experience. Taking a biopsy that is inadequate is a common occurrence. At times, the physician’s clinical impression may be that a biopsy has obtained adequate tissue, but histologically only the superficial part of the skin surface has been sampled. This often is because of thickening of the superficial skin, whether as a manifestation of the anatomic site (eg, acral skin) or the disease process itself.

Unfortunately, this superficial skin often is nondiagnostic when unaccompanied by underlying epidermis and dermis. It is important to keep this in mind when obtaining a skin biopsy, especially when dealing with lesions that are very scaly or keratinized. An equivocal biopsy wastes time, energy, and money, and can negatively impact patient care.3 It can be difficult to balance practical aspects of the biopsy (ie, optimizing cosmetic outcomes, minimizing scarring and wound size) with the need to obtain sufficient tissue sampling (FIGURE 1).

3. Choose punch over shave biopsy for rashes.

In a punch biopsy, a disposable metal cylinder with a sharpened edge is used to “punch” out a piece of skin that can be examined under the microscope. Punch biopsy is the preferred technique for almost all inflammatory skin conditions (rashes) because the pathologist is able to examine both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis4 (FIGURE 2).

Pathologists use the pattern of inflammation, in conjunction with epidermal changes, to distinguish different types of inflammatory processes. For example, lichen planus is typically associated with superficial inflammation, while lupus is known to have prominent superficial and deep inflammation.

An inadequate punch biopsy sample can hinder histological assessment of inflammatory skin disorders that involve both the superficial and deep portions of the dermis and can make arriving at a definitive diagnosis more challenging. The diameter of a punch cylinder ranges from 1 to 8 mm. Smaller punch biopsies often create diagnostic challenges because they provide so little sample. A punch biopsy size of 4 mm is commonly used for rashes.

An advantage of the punch biopsy is that patients are left with linear scars rather than round, potentially dyspigmented (darker or lighter) scars that are often associated with shave biopsy. A well-sutured punch biopsy can be cosmetically elegant, particularly if closure is oriented along relaxed skin tension lines. For this reason, punch biopsies are well suited for cosmetically sensitive locations such as the face, although shave biopsies are also often performed on the face.

4. Choose an excisional biopsy for a melanocytic neoplasm, when possible.

The purpose of an excisional biopsy (which typically includes a 1 to 3 mm rim of normal skin around the lesion) is to completely remove a lesion. The excisional biopsy generally is the preferred technique for clinically atypical melanocytic neoplasms (lesions that are not definitively benign).4-8

When suspicion for melanoma is high, excisional biopsies should be performed with minimal undermining to preserve the accuracy of any future sentinel lymph node biopsy surgeries. Excisional biopsy is the most involved type of biopsy and has the largest potential for cosmetic disfigurement if not properly planned and performed. While guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology state that “narrow excisional biopsy that encompasses [the] entire breadth of lesion with clinically negative margins to ensure that the lesion is not transected” is preferred, they also acknowledge that partial sampling (incisional biopsy) is acceptable in select clinical circumstances,9 such as when a lesion is large or on a cosmetically sensitive site such as the face.10

While a larger punch biopsy (6 or 8 mm) or even deep shave/saucerization may function as an excisional biopsy for very small lesions, this approach can be problematic. For one thing, these biopsies are more likely than an excisional biopsy to leave a portion of the lesion in situ. Another concern is that a shave biopsy of a melanocytic lesion can lead to error or difficulty in obtaining the correct diagnosis on later biopsy.11 For pathologists, smaller or incomplete samples make it challenging to establish an accurate diagnosis.12 Among melanomas seen at a tertiary referral center, histopathological misdiagnosis was more common with a punch or shave biopsy than with an excisional biopsy.9

It has been shown that partial biopsy for melanoma results in more residual disease at wide local excision and makes it more challenging to properly stage the lesion.13,14 If a shave biopsy is used to sample a suspected melanocytic neoplasm, it is imperative to document the specific site of the biopsy, indicate the size of the melanocytic lesion on the pathology requisition form, and ensure that all (or nearly all) of the clinically evident lesion is sampled. Detailing the location of the lesion in the chart is not only essential in evaluating the present lesion, but it will serve you well in the future. Without knowing the patient’s clinical history, benign nevi that recur after a prior biopsy can be difficult to histologically distinguish from melanoma (FIGURE 3). For more on this, see tip #7.

5. Be careful with curettage.

6. Remember the importance of proper fixation and processing.

As obvious as it may sound, it is important to remember to promptly place sampled tissue in an adequate amount of formalin so that the tissue is submersed in it in the container.15 Failure to do so can result in improper fixation and will make it difficult to render an appropriate diagnosis. Conventionally, a 10:1 formalin volume to tissue volume ratio is recommended. If the “cold time”—the amount of time a tissue sample is out of formalin—is long enough (greater than a few hours), an appropriate assessment can be impossible.

Appropriate fixation and fixation times are important because molecular testing is being increasingly used to make pathological diagnoses.16 Additionally, aggressively manipulating a biopsy sample while extracting it or placing it in formalin can cause “crush” artifact, which can limit interpretability (FIGURE 5).

7. Properly photograph and document the biopsy location.

When performing a biopsy of a suspicious neoplasm, physicians often remove all of the lesion’s superficial components, which means that at the patient’s follow-up appointment and subsequent treatments, only a well-healed biopsy site will remain. The biopsy site may be so well healed that it blends seamlessly into the surrounding skin and is nearly impossible for the physician to identify. This problem is seen most often when patients present for surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.17

To properly record the site of a biopsy for future dermatologic exams, take pictures of the lesion at the time of biopsy. The photographs should clearly document the lesion in question, and should be taken far enough from the site that surrounding lesions and/ or other anatomic landmarks are also visible. Biangulation or triangulation (taking a series of 2 or 3 measurements, respectively, from the site of the lesion to nearby anatomic landmarks) can be used in conjunction with photographs.

When using measurements, be as specific and accurate as possible with anatomic terms. For example, measuring the distance from the “ear” is not helpful. It would be more helpful to measure the distance from the “tragus” or the “root of the helix.” Without a properly photographed and documented biopsy site, surgical treatment may need to be delayed until the location can be confirmed.

8. Give the pathologist a pertinent history.

Providing the pathologist with a sufficient history, including the distribution and appearance of the lesion, and how long the patient has had it, can be essential in narrowing the diagnosis or making the differential diagnoses. Things like medication use or new exposures to perfumes, lotions, or plants can be especially helpful and are often overlooked when filling out the pathology requisition form.

When warranted, phone calls are helpful. You might, for example, call the pathologist and give him or her a more detailed physical examination description or additional pertinent history that was discovered after the requisition was filled out. Providing a good history can make the difference between a specific diagnosis and a broad differential.

9. Know when to refer.

There is no shame in asking for a second opinion when it comes to evaluating a skin issue, especially in regards to melanocytic neoplasms, where the stakes can be high, or skin eruptions that do not respond to conventional therapy. Remember, many cases are difficult, even for experts, and require a careful balance of clinical and histopathological judgment.18

CORRESPONDENCE

Jayson Miedema, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 410 Market Street, Suite 400, Chapel Hill, NC 27516; jmiedema@unch.unc.edu

1. Pickett H. Shave and punch biopsy for skin lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:995-1002.

2. Alguire PC, Mathes BM. Skin biopsy techniques for the internist. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:46-54.