User login

The many variants of psoriasis

The “heartbreak of psoriasis,” coined by an advertiser in the 1960s, conveyed the notion that this disease was a cosmetic disorder mainly limited to skin involvement. John Updike’s article in the September 1985 issue of The New Yorker, “At War With My Skin,” detailed Mr. Updike’s feelings of isolation and stress related to his condition, helping to reframe the popular concept of psoriasis.1 Updike’s eloquent account describing his struggles to find effective treatment increased public awareness about psoriasis, which in fact affects other body systems as well.

The overall prevalence of psoriasis is 1.5% to 3.1% in the United States and United Kingdom.2,3 More than 6.5 million adults in the United States > 20 years of age are affected.3 The most commonly affected demographic group is non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Our expanding knowledge of pathogenesis

Studies of genetic linkage have identified genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with psoriasis.4 The interaction between environmental triggers and the innate and adaptive immune systems leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, and IL-17 are important cytokines associated with psoriatic inflammation.4 There are common pathways of inflammation in both psoriasis and cardiovascular disease resulting in oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction.4 Ninety percent of early-onset psoriasis is associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6.4 And alterations in the microbiome of the skin may contribute, as reduced microbial diversity has been found in psoriatic lesions.5

Comorbidities are common

Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for diabetes and major adverse cardiovascular events.6 Hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and lymphoma (particularly cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) are also associated with psoriasis.6 Psoriatic arthritis is frequently encountered with cutaneous psoriasis; however, it is often not recognized until late in the disease course.

There also appears to be an association among psoriasis, dietary factors, and celiac disease.7-9 Positive testing for IgA anti-endomysial antibodies and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies should prompt consideration of starting a gluten-free diet, which has been shown to improve psoriatic

The different types of psoriasis

The classic presentation of psoriasis involves stubborn plaques with silvery scale on extensor surfaces such as the elbows and knees. The severity of the disease corresponds with the amount of body surface area affected. While plaque-type psoriasis is the most common form, other patterns exist. Individuals may exhibit 1 dominant pattern or multiple psoriatic variants simultaneously. Most types of psoriasis have 3 characteristic features: erythema, skin thickening, and scales.

Certain history and physical clues can aid in diagnosing psoriasis; these include the Koebner phenomenon, the Auspitz sign, and the Woronoff ring. The Koebner phenomenon refers to the development of psoriatic lesions in an area of trauma (FIGURE 1), frequently resulting in a linear streak-like appearance. The Auspitz sign describes the pinpoint bleeding that may be encountered with the removal of a psoriatic plaque. The Woronoff ring is a pale blanching ring that may surround a psoriatic lesion.

Continue to: Chronic plaque-type psoriasis

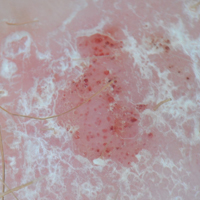

Chronic plaque-type psoriasis (Figures 2A and 2B), the most common variant, is characterized by sharply demarcated pink papules and plaques with a silvery scale in a symmetric distribution on the extensor surfaces, scalp, trunk, and lumbosacral areas.

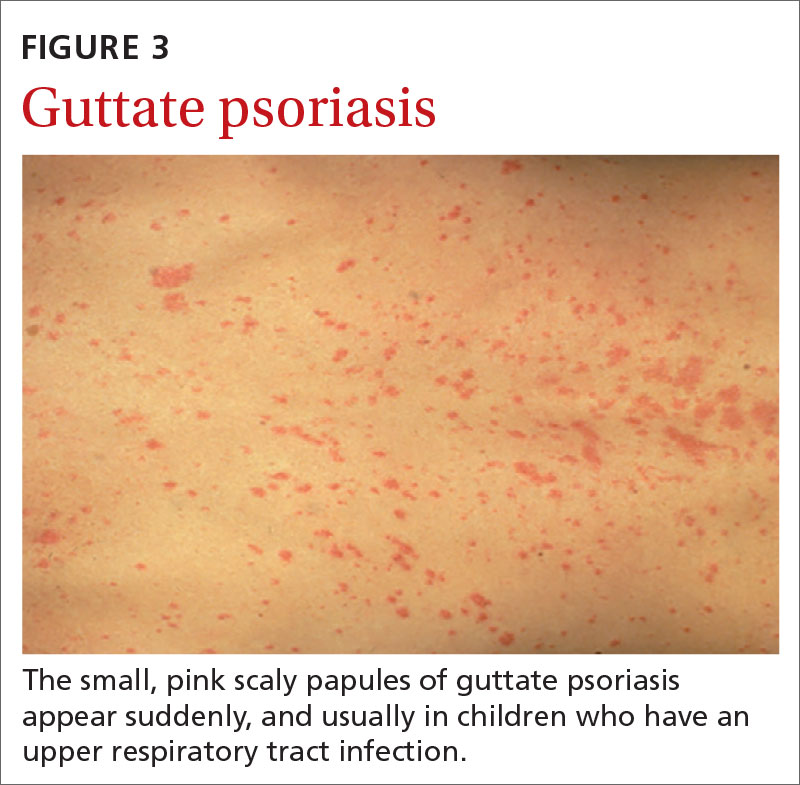

Guttate psoriasis (FIGURE 3) features small (often < 1 cm) pink scaly papules that appear suddenly. It is more commonly seen in children and is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, often with Streptococcus.10 If strep testing is positive, guttate psoriasis may improve after appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Erythrodermic psoriasis (FIGUREs 4A and 4B) involves at least 75% of the body with erythema and scaling.11 Erythroderma can be caused by many other conditions such as atopic dermatitis, a drug reaction, Sezary syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Treatments for other conditions in the differential diagnosis can potentially make psoriasis worse. Unfortunately, findings on a skin biopsy are often nonspecific, making careful clinical observation crucial to arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

Pustular psoriasis is characterized by bright erythema and sterile pustules. Pustular psoriasis can be triggered by pregnancy, sudden tapering of corticosteroids, hypocalcemia, and infection. Involvement of the palms and soles with severe desquamation can drastically impact daily functioning and quality of life.

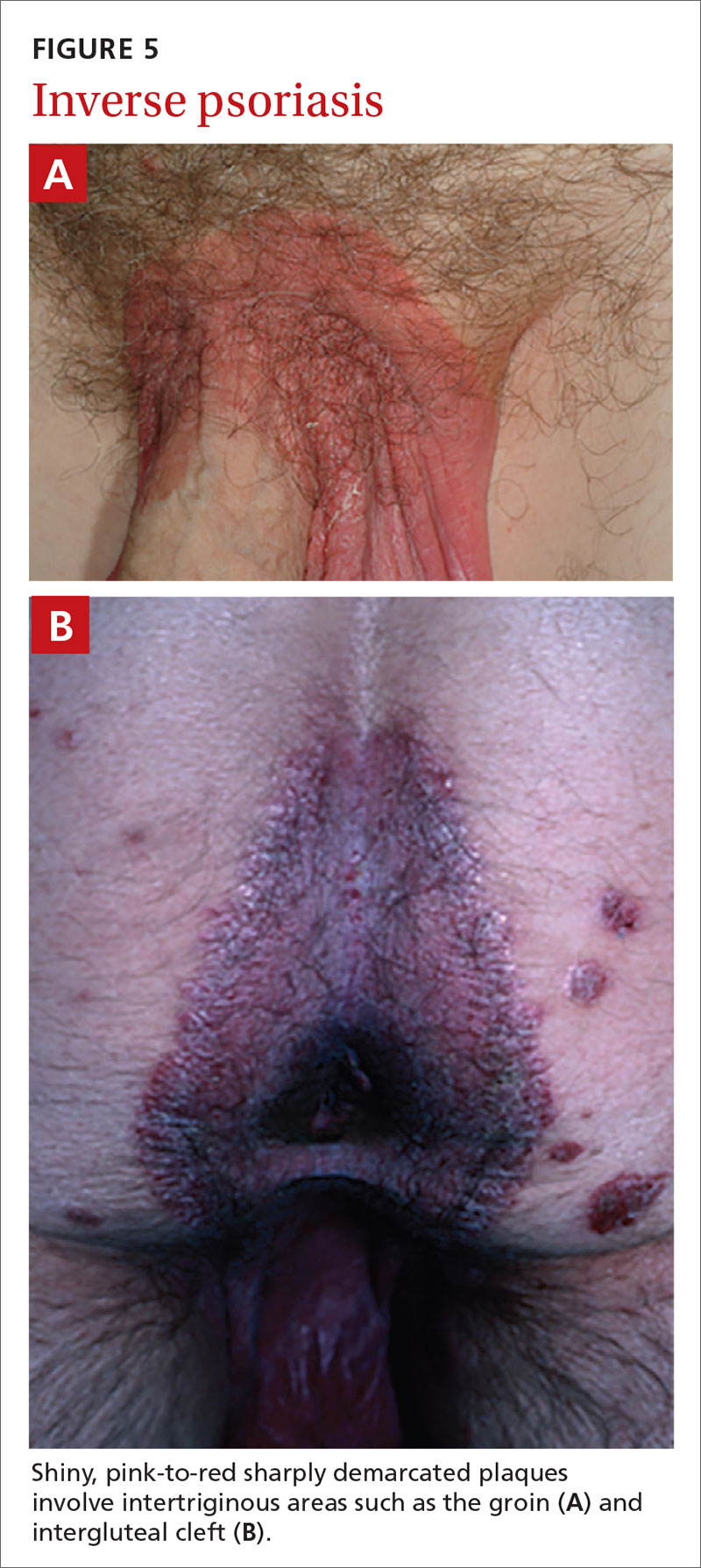

Inverse or flexural psoriasis (FIGUREs 5A and 5B) is characterized by shiny, pink-to-red sharply demarcated plaques involving intertriginous areas, typically the groin, inguinal crease, axilla, inframammary regions, and intergluteal cleft.

Continue to: Geographic tongue

Geographic tongue describes psoriasis of the tongue. The mucosa of the tongue has white plaques with a geographic border. Instead of scale, the moisture on the tongue causes areas of hyperkeratosis that appear white.

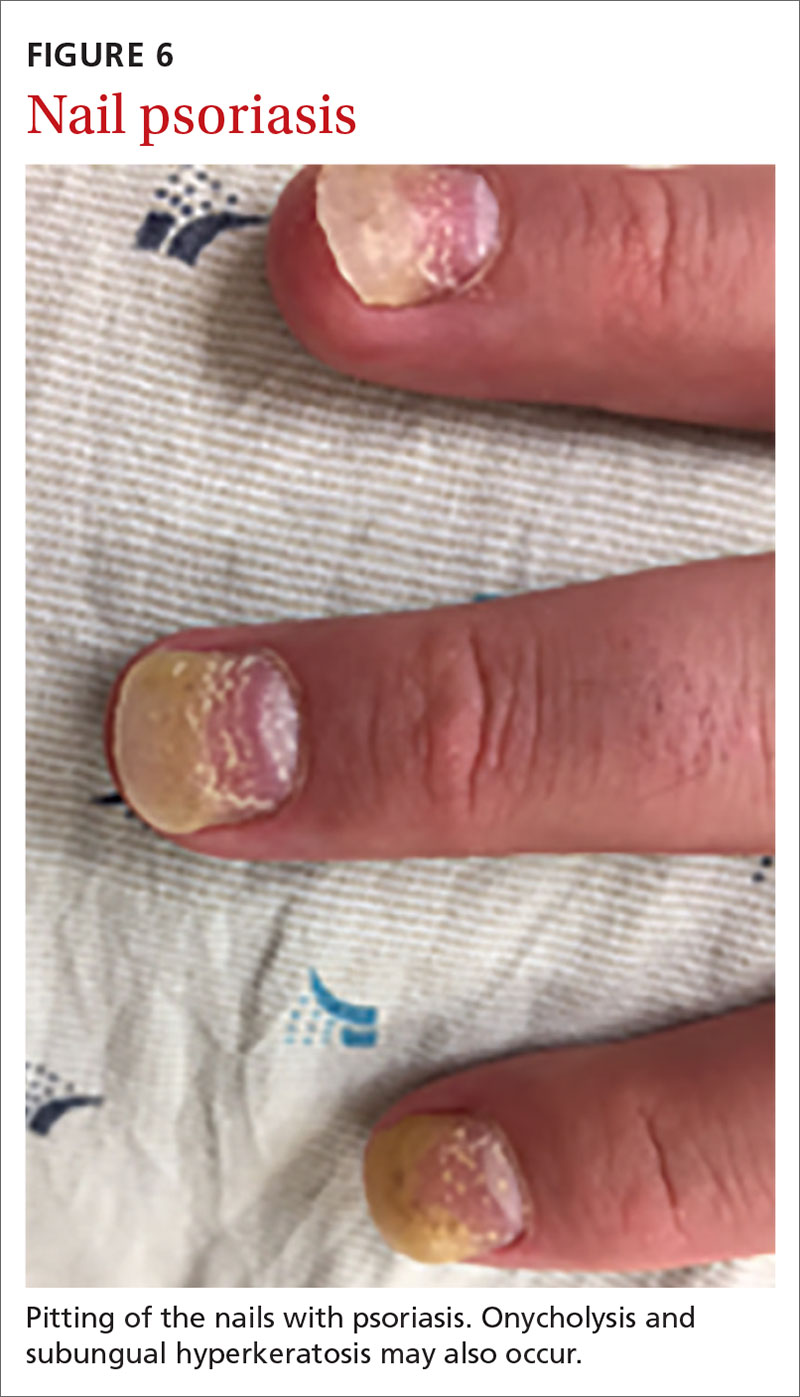

Nail psoriasis can manifest as nail pitting (FIGURE 6), oil staining, onycholysis (distal lifting of the nail), and subungual hyperkeratosis. Nail psoriasis is often quite distressing for patients and can be difficult to treat.

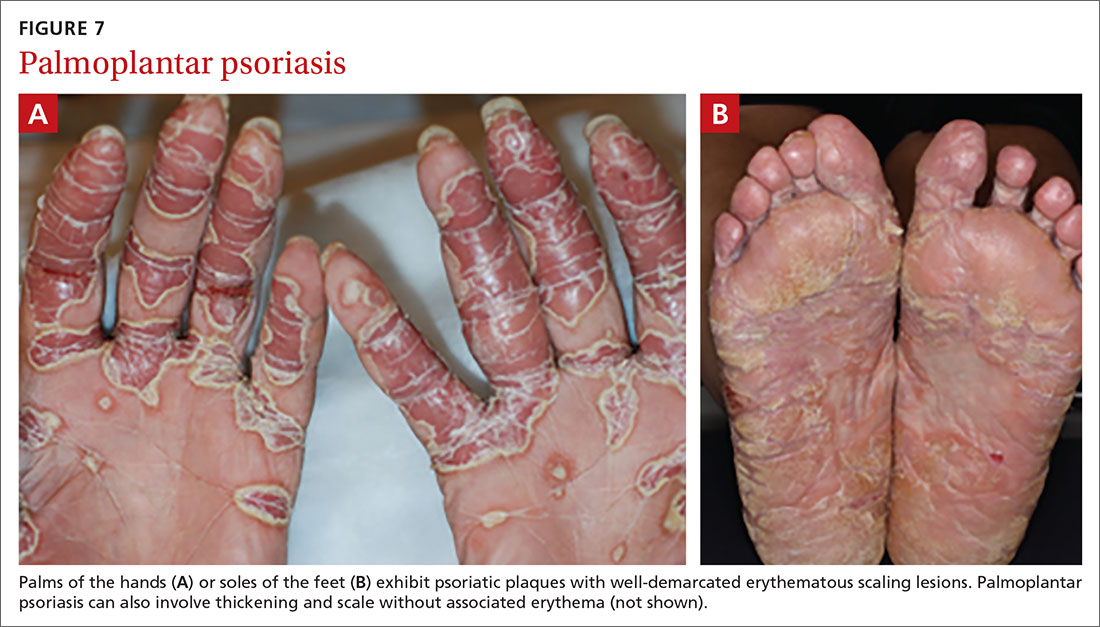

Palmoplantar psoriasis (FIGUREs 7A and 7B) can be painful due to the involvement of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Lesions will either be similar to other psoriatic plaques with well-demarcated erythematous scaling lesions or involve thickening and scale without associated erythema.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause significant joint damage and disability. Most affected individuals with psoriatic arthritis have a history of preceding skin disease.12 There are no specific lab tests for psoriasis; radiologic studies can show bulky syndesmophytes, central and marginal erosions, and periostitis. Patterns of joint involvement are variable. Psoriatic arthritis is more likely to affect the distal interphalangeal joints than rheumatoid arthritis and is more likely to affect the metacarpophalangeal joints than osteoarthritis.13

Psoriatic arthritis often progresses insidiously and is commonly described as causing discomfort rather than acute pain. Enthesitis, inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone, is often present. Joint destruction may lead to the telescoping “opera glass” digit (FIGURE 8).

Continue to: Drug-provoked psoriasis

Drug-provoked psoriasis is divided into 2 groups: drug-induced and drug-aggravated. Drug-induced psoriasis will improve after discontinuation of the causative drug and tends to occur in patients without a personal or family history of psoriasis. Drug-aggravated psoriasis continues to progress after the discontinuation of the offending drug and is more often seen in patients with a history of psoriasis.14 Drugs that most commonly provoke psoriasis are beta-blockers, lithium, and antimalarials.10 Other potentially aggravating agents include antibiotics, digoxin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10

Consider these skin disorders in the differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is usually clinical, and a skin biopsy is rarely needed. However, a range of other skin disorders should be kept in mind when considering the differential diagnosis.

Mycosis fungoides is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that forms erythematous plaques that may show wrinkling and epidermal atrophy in sun-protected sites. Onset usually occurs among the elderly.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by salmon-colored patches that may have small areas of normal skin (“islands of sparing”), hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff of the skin, usually involves the scalp and nasolabial areas and the T-zone of the face.

Continue to: Lichen planus

Lichen planus usually appears slightly more purple than psoriasis and typically involves the mouth, flexural surfaces of the wrists, genitals, and ankles.

Other conditions in the differential include pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which may be identified on skin biopsy. Inverse psoriasis can be difficult to differentiate from candida intertrigo, erythrasma, or tinea cruris.

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation can help differentiate psoriasis from candida or tinea. In psoriasis, a KOH test will be negative for fungal elements. Mycology culture on skin scrapings may be performed to rule out fungal infection. Erythrasma may exhibit a coral red appearance under Wood lamp examination.

If a lesion fails to respond to appropriate treatment, a careful drug history and biopsy can help clarify the diagnosis.

Document disease

It’s important to thoroughly document the extent and severity of the psoriasis and to monitor the impact of treatment. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is a commonly used method that calculates a score based on the area (extent) of involvement surrounding 4 major anatomical regions (head, upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities), as well as the degree of erythema, induration, and scaling of lesions. The average redness, thickness, and scaling are graded on a scale of 0 to 4 and the extent of involvement is calculated to form a total numerical score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).

Continue to: Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many options in the treatment arsenal

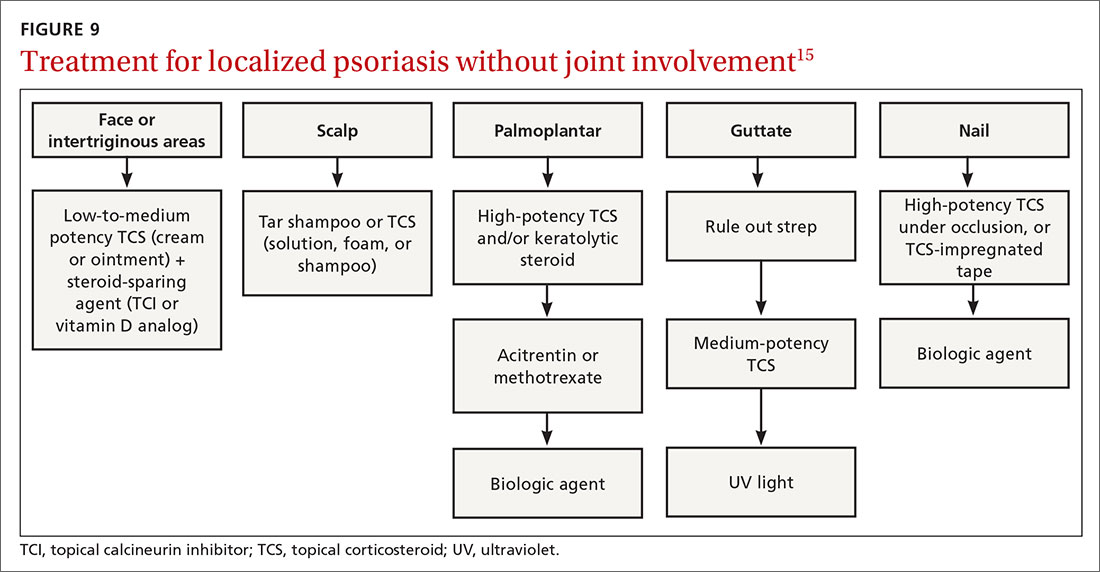

Many treatments can improve psoriasis.9,15-19 Most affected individuals discover that emollients and exposure to natural sunlight can be effective, as are soothing baths (balneotherapy) or topical coal tar application. More persistent disease requires prescription therapy. Individualize therapy according to the severity of disease, location of the lesions, involvement of joints, and comorbidities (FIGURE 9).15

If ≤ 10% of the body surface area is involved, treatment options generally are explored in a stepwise progression from safest and most affordable to more involved therapies as needed: moisturization and avoidance of repetitive trauma, topical corticosteroids (TCS), vitamin D analogs, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and vitamin A creams. Recalcitrant disease will likely require ultraviolet (UV) light treatment or a systemic agent.15

If > 10% of the body surface area is involved, but joints are not involved, consider UV light treatment or a combination of alcitretin and TCS. If the joints are involved, likely initial options would be methotrexate, cyclosporine, or TNF-α inhibitor. Additional options to consider are anti-IL-17 or anti-IL-23 agents.15

If there’s joint involvement. In individuals with mild peripheral arthritis involving fewer than 4 joints without evidence of joint damage on imaging, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment. If the peripheral arthritis persists, or if it is associated with moderate-to-severe erosions or with substantial functional limitations, initiate treatment with a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. If the disease remains active, consider biologic agents.

Case studies

Mild-to-moderate psoriasis

Patient A is a 19-year-old woman presenting for evaluation of a persistently dry, flaking scalp. She has had the itchy scalp for years, as well as several small “patches” across her elbows, legs, knees, and abdomen. Over-the-counter emollients have not helped. The patient also says she has had brittle nails on several of her fingers, which she keeps covered with thick polish.

Continue to: The condition exemplified...

The condition exemplified by Patient A can typically be managed with topical products.

Topical steroids may be classified by different delivery vehicles, active ingredients, and potencies. The National Psoriasis Foundation's Topical Steroids Potency Chart can provide guidance (visit www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/topicals/steroids/potency-chart and scroll down). Prescribing an appropriate amount is important; the standard 30-g prescription tube is generally required to cover the entire skin surface. Ointments have a greasy consistency (typically a petroleum base), which enhances potency and hydrates the skin. Creams and lotions are easier to rub on and spread. Gels are alcohol based and readily absorbed.16 Solutions, foams, and shampoos are particularly useful to treat psoriasis in hairy areas such as the scalp.

Corticosteroid potency ranges from Class I to Class VII, with the former being the most potent. While TCS products are typically effective with minimal systemic absorption, it is important to counsel patients on the risk of skin atrophy, impaired wound healing, and skin pigmentation changes with chronic use. With nail psoriasis, a potent topical steroid (including flurandrenolide [Cordran] tape) applied to the proximal nail fold has shown benefit.20

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs; eg, tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream) are anti-inflammatory agents often used in conjunction with topical steroids to minimize steroid use and associated adverse effects.15 A possible steroid-sparing regimen includes using a TCI Monday through Friday and a topical steroid on the weekend.

Topical vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene, calcipotriol, calcitriol) inhibit proliferation of keratinocytes and decrease the production of inflammatory mediators.15,17-19,21 Application of a vitamin D analog in combination with a high-potency TCS, systemic treatment, or phototherapy can provide greater efficacy, a more rapid onset of action, and less irritation than can the vitamin D analog used alone.21 If used in combination with UV light, apply topical vitamin D after the light therapy to prevent degradation.

Continue to: UV light therapy

UV light therapy is often used in cases refractory to topical therapy. Patients are typically prescribed 2 to 3 treatments per week with narrowband UVB (311-313 nm), the excimer laser (308 nm), or, less commonly, PUVA (UV treatment with psoralens). Treatment begins with a minimal erythema dose—the lowest dose to achieve minimal erythema of the skin before burning. When that is determined, exposure is increased as needed—depending on the response. If this is impractical or too time-consuming for the patient, an alternative recommendation would be increased exposure to natural sunlight or even use of a tanning booth. However, patients must then be cautioned about the increased risk of skin cancer.

Refractory/severe psoriasis

Patient B is a 35-year-old man with a longstanding history of psoriasis affecting his scalp and nails. Over the past 10 years, psoriatic lesions have also appeared and grown across his lower back, gluteal fold, legs, abdomen, and arms. He is now being evaluated by a rheumatologist for worsening symmetric joint pain that includes his lower back.

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis since the 1950s. Methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase and is typically given as an oral medication dosed once weekly with folic acid supplementation on the other 6 days.17 The most common adverse effects encountered with methotrexate are gastrointestinal upset and oral ulcers; however, routine monitoring for myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity is required.

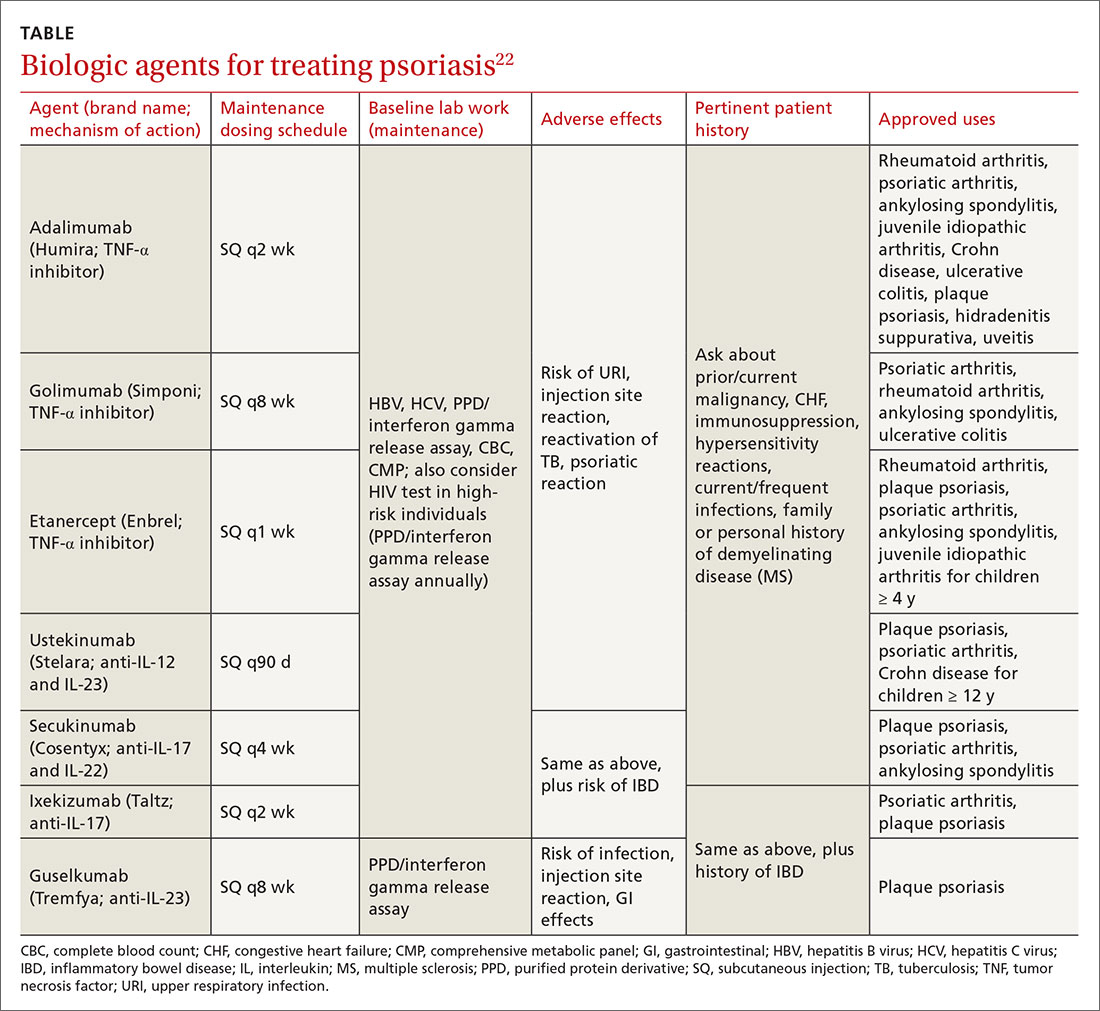

Biologic therapy. When conventional therapies fail, immune-targeted treatment with “biologics” may be initiated. As knowledge of signaling pathways and the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis has increased, so has the number of biologic agents, which are generally well tolerated and effective in managing plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Although their use, which requires monitoring, is handled primarily by specialists, familiarizing yourself with available agents can be helpful (TABLE).22

Nutritional modification and supplementation in treating skin disease still requires further investigation. Fish oil has shown benefit for cutaneous psoriasis in randomized controlled trials.7,8 Oral vitamin D supplementation requires further study, whereas selenium and B12 supplementation have not conferred consistent benefit.7 Given that several studies have demonstrated a relationship between body mass index and psoriatic disease severity, weight loss may be helpful in the management of psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis.8

Continue to: Other systemic agents

Other systemic agents—for individuals who cannot tolerate the biologic agents—include acitretin, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.15,17

Paradoxical psoriatic reactions

When a psoriatic condition develops during biologic drug therapy, it is known as a paradoxical psoriatic reaction. The onset of de novo psoriasis has been documented during TNF-α inhibitor therapy for individuals with underlying rheumatoid arthritis.23 Skin biopsy reveals the same findings as common plaque psoriasis.

Using immunosuppressive Tx? Screen for tuberculosis

Testing to exclude a diagnosis of latent or undiagnosed tuberculosis must be performed prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate or a biologic agent. Tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold test, and the T-SPOT.TB test are accepted screening modalities. Discordance between tuberculin skin tests and the interferon gamma release assays in latent TB highlights the need for further study using the available QuantiFERON-TB gold test and the T-SPOT.TB test.24

CORRESPONDENCE

Karl T. Clebak, MD, FAAFP, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; kclebak@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

1. Jackson R. John Updike on psoriasis. At war with my skin, from the journal of a leper. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:113-115.

2. Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537-1541.

3. Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003-2006 and 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:37-45.

4. Alexander H, Nestle FO. Pathogenesis and immunotherapy in cutaneous psoriasis: what can rheumatologists learn? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:71-78.

5. Fahlén A, Engstrand L, Baker BS, et al. Comparison of bacterial microbiota in skin biopsies from normal and psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:15-22.

6. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

7. Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part III: role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:561-569.

8. Debbaneh M, Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part I: impact of weight loss interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:133-140.

9. Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350-358.

10. Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606-615.

11. Singh RK, Lee KM, Ucmak D, et al. Erythrodermic psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Aukl). 2016;6:93-104.

12. Garg A, Gladman D. Recognizing psoriatic arthritis in the dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:733-748.

13. McGonagle D, Hermann KG, Tan AL. Differentiation between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: implications for pathogenesis and treatment in the biologic therapy era. Rheumatology. 2015;54:29-38.

14. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Drug-provoked psoriasis: is it drug induced or drug aggravated?: understanding pathophysiology and clinical relevance. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:32-38.

15. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:787-801.

16. Helm MF, Farah JB, Carvalho M, et al. Compounded topical medications for diseases of the skin: a long tradition still relevant today. N Am J Med Sci. 2017;10:116-118.

17. Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:626-633.

18. Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Kang S. Topical vitamin D3. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007:691-695.

19. Lebwohl M, Siskin SB, Epinette W, et al. A multicenter trial of calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment compared with either agent alone for the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:268-269.

20. Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis: a review of treatment options. Drugs. 2016;76:675-705.

21. Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

22. Rønholt K, Iversen L. Old and new biological therapies for psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:e2297.

23. Toussirot É, Aubin F. Paradoxical reactions under TNF-alpha blocking agents and other biologic agents given for chronic immune-mediated diseases: an analytical and comprehensive overview. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000239.

24. Connell TG, Ritz N, Paxton GA, et al. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold and T-SPOT.TB in children. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2624.

The “heartbreak of psoriasis,” coined by an advertiser in the 1960s, conveyed the notion that this disease was a cosmetic disorder mainly limited to skin involvement. John Updike’s article in the September 1985 issue of The New Yorker, “At War With My Skin,” detailed Mr. Updike’s feelings of isolation and stress related to his condition, helping to reframe the popular concept of psoriasis.1 Updike’s eloquent account describing his struggles to find effective treatment increased public awareness about psoriasis, which in fact affects other body systems as well.

The overall prevalence of psoriasis is 1.5% to 3.1% in the United States and United Kingdom.2,3 More than 6.5 million adults in the United States > 20 years of age are affected.3 The most commonly affected demographic group is non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Our expanding knowledge of pathogenesis

Studies of genetic linkage have identified genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with psoriasis.4 The interaction between environmental triggers and the innate and adaptive immune systems leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, and IL-17 are important cytokines associated with psoriatic inflammation.4 There are common pathways of inflammation in both psoriasis and cardiovascular disease resulting in oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction.4 Ninety percent of early-onset psoriasis is associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6.4 And alterations in the microbiome of the skin may contribute, as reduced microbial diversity has been found in psoriatic lesions.5

Comorbidities are common

Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for diabetes and major adverse cardiovascular events.6 Hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and lymphoma (particularly cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) are also associated with psoriasis.6 Psoriatic arthritis is frequently encountered with cutaneous psoriasis; however, it is often not recognized until late in the disease course.

There also appears to be an association among psoriasis, dietary factors, and celiac disease.7-9 Positive testing for IgA anti-endomysial antibodies and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies should prompt consideration of starting a gluten-free diet, which has been shown to improve psoriatic

The different types of psoriasis

The classic presentation of psoriasis involves stubborn plaques with silvery scale on extensor surfaces such as the elbows and knees. The severity of the disease corresponds with the amount of body surface area affected. While plaque-type psoriasis is the most common form, other patterns exist. Individuals may exhibit 1 dominant pattern or multiple psoriatic variants simultaneously. Most types of psoriasis have 3 characteristic features: erythema, skin thickening, and scales.

Certain history and physical clues can aid in diagnosing psoriasis; these include the Koebner phenomenon, the Auspitz sign, and the Woronoff ring. The Koebner phenomenon refers to the development of psoriatic lesions in an area of trauma (FIGURE 1), frequently resulting in a linear streak-like appearance. The Auspitz sign describes the pinpoint bleeding that may be encountered with the removal of a psoriatic plaque. The Woronoff ring is a pale blanching ring that may surround a psoriatic lesion.

Continue to: Chronic plaque-type psoriasis

Chronic plaque-type psoriasis (Figures 2A and 2B), the most common variant, is characterized by sharply demarcated pink papules and plaques with a silvery scale in a symmetric distribution on the extensor surfaces, scalp, trunk, and lumbosacral areas.

Guttate psoriasis (FIGURE 3) features small (often < 1 cm) pink scaly papules that appear suddenly. It is more commonly seen in children and is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, often with Streptococcus.10 If strep testing is positive, guttate psoriasis may improve after appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Erythrodermic psoriasis (FIGUREs 4A and 4B) involves at least 75% of the body with erythema and scaling.11 Erythroderma can be caused by many other conditions such as atopic dermatitis, a drug reaction, Sezary syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Treatments for other conditions in the differential diagnosis can potentially make psoriasis worse. Unfortunately, findings on a skin biopsy are often nonspecific, making careful clinical observation crucial to arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

Pustular psoriasis is characterized by bright erythema and sterile pustules. Pustular psoriasis can be triggered by pregnancy, sudden tapering of corticosteroids, hypocalcemia, and infection. Involvement of the palms and soles with severe desquamation can drastically impact daily functioning and quality of life.

Inverse or flexural psoriasis (FIGUREs 5A and 5B) is characterized by shiny, pink-to-red sharply demarcated plaques involving intertriginous areas, typically the groin, inguinal crease, axilla, inframammary regions, and intergluteal cleft.

Continue to: Geographic tongue

Geographic tongue describes psoriasis of the tongue. The mucosa of the tongue has white plaques with a geographic border. Instead of scale, the moisture on the tongue causes areas of hyperkeratosis that appear white.

Nail psoriasis can manifest as nail pitting (FIGURE 6), oil staining, onycholysis (distal lifting of the nail), and subungual hyperkeratosis. Nail psoriasis is often quite distressing for patients and can be difficult to treat.

Palmoplantar psoriasis (FIGUREs 7A and 7B) can be painful due to the involvement of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Lesions will either be similar to other psoriatic plaques with well-demarcated erythematous scaling lesions or involve thickening and scale without associated erythema.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause significant joint damage and disability. Most affected individuals with psoriatic arthritis have a history of preceding skin disease.12 There are no specific lab tests for psoriasis; radiologic studies can show bulky syndesmophytes, central and marginal erosions, and periostitis. Patterns of joint involvement are variable. Psoriatic arthritis is more likely to affect the distal interphalangeal joints than rheumatoid arthritis and is more likely to affect the metacarpophalangeal joints than osteoarthritis.13

Psoriatic arthritis often progresses insidiously and is commonly described as causing discomfort rather than acute pain. Enthesitis, inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone, is often present. Joint destruction may lead to the telescoping “opera glass” digit (FIGURE 8).

Continue to: Drug-provoked psoriasis

Drug-provoked psoriasis is divided into 2 groups: drug-induced and drug-aggravated. Drug-induced psoriasis will improve after discontinuation of the causative drug and tends to occur in patients without a personal or family history of psoriasis. Drug-aggravated psoriasis continues to progress after the discontinuation of the offending drug and is more often seen in patients with a history of psoriasis.14 Drugs that most commonly provoke psoriasis are beta-blockers, lithium, and antimalarials.10 Other potentially aggravating agents include antibiotics, digoxin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10

Consider these skin disorders in the differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is usually clinical, and a skin biopsy is rarely needed. However, a range of other skin disorders should be kept in mind when considering the differential diagnosis.

Mycosis fungoides is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that forms erythematous plaques that may show wrinkling and epidermal atrophy in sun-protected sites. Onset usually occurs among the elderly.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by salmon-colored patches that may have small areas of normal skin (“islands of sparing”), hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff of the skin, usually involves the scalp and nasolabial areas and the T-zone of the face.

Continue to: Lichen planus

Lichen planus usually appears slightly more purple than psoriasis and typically involves the mouth, flexural surfaces of the wrists, genitals, and ankles.

Other conditions in the differential include pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which may be identified on skin biopsy. Inverse psoriasis can be difficult to differentiate from candida intertrigo, erythrasma, or tinea cruris.

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation can help differentiate psoriasis from candida or tinea. In psoriasis, a KOH test will be negative for fungal elements. Mycology culture on skin scrapings may be performed to rule out fungal infection. Erythrasma may exhibit a coral red appearance under Wood lamp examination.

If a lesion fails to respond to appropriate treatment, a careful drug history and biopsy can help clarify the diagnosis.

Document disease

It’s important to thoroughly document the extent and severity of the psoriasis and to monitor the impact of treatment. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is a commonly used method that calculates a score based on the area (extent) of involvement surrounding 4 major anatomical regions (head, upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities), as well as the degree of erythema, induration, and scaling of lesions. The average redness, thickness, and scaling are graded on a scale of 0 to 4 and the extent of involvement is calculated to form a total numerical score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).

Continue to: Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many treatments can improve psoriasis.9,15-19 Most affected individuals discover that emollients and exposure to natural sunlight can be effective, as are soothing baths (balneotherapy) or topical coal tar application. More persistent disease requires prescription therapy. Individualize therapy according to the severity of disease, location of the lesions, involvement of joints, and comorbidities (FIGURE 9).15

If ≤ 10% of the body surface area is involved, treatment options generally are explored in a stepwise progression from safest and most affordable to more involved therapies as needed: moisturization and avoidance of repetitive trauma, topical corticosteroids (TCS), vitamin D analogs, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and vitamin A creams. Recalcitrant disease will likely require ultraviolet (UV) light treatment or a systemic agent.15

If > 10% of the body surface area is involved, but joints are not involved, consider UV light treatment or a combination of alcitretin and TCS. If the joints are involved, likely initial options would be methotrexate, cyclosporine, or TNF-α inhibitor. Additional options to consider are anti-IL-17 or anti-IL-23 agents.15

If there’s joint involvement. In individuals with mild peripheral arthritis involving fewer than 4 joints without evidence of joint damage on imaging, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment. If the peripheral arthritis persists, or if it is associated with moderate-to-severe erosions or with substantial functional limitations, initiate treatment with a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. If the disease remains active, consider biologic agents.

Case studies

Mild-to-moderate psoriasis

Patient A is a 19-year-old woman presenting for evaluation of a persistently dry, flaking scalp. She has had the itchy scalp for years, as well as several small “patches” across her elbows, legs, knees, and abdomen. Over-the-counter emollients have not helped. The patient also says she has had brittle nails on several of her fingers, which she keeps covered with thick polish.

Continue to: The condition exemplified...

The condition exemplified by Patient A can typically be managed with topical products.

Topical steroids may be classified by different delivery vehicles, active ingredients, and potencies. The National Psoriasis Foundation's Topical Steroids Potency Chart can provide guidance (visit www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/topicals/steroids/potency-chart and scroll down). Prescribing an appropriate amount is important; the standard 30-g prescription tube is generally required to cover the entire skin surface. Ointments have a greasy consistency (typically a petroleum base), which enhances potency and hydrates the skin. Creams and lotions are easier to rub on and spread. Gels are alcohol based and readily absorbed.16 Solutions, foams, and shampoos are particularly useful to treat psoriasis in hairy areas such as the scalp.

Corticosteroid potency ranges from Class I to Class VII, with the former being the most potent. While TCS products are typically effective with minimal systemic absorption, it is important to counsel patients on the risk of skin atrophy, impaired wound healing, and skin pigmentation changes with chronic use. With nail psoriasis, a potent topical steroid (including flurandrenolide [Cordran] tape) applied to the proximal nail fold has shown benefit.20

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs; eg, tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream) are anti-inflammatory agents often used in conjunction with topical steroids to minimize steroid use and associated adverse effects.15 A possible steroid-sparing regimen includes using a TCI Monday through Friday and a topical steroid on the weekend.

Topical vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene, calcipotriol, calcitriol) inhibit proliferation of keratinocytes and decrease the production of inflammatory mediators.15,17-19,21 Application of a vitamin D analog in combination with a high-potency TCS, systemic treatment, or phototherapy can provide greater efficacy, a more rapid onset of action, and less irritation than can the vitamin D analog used alone.21 If used in combination with UV light, apply topical vitamin D after the light therapy to prevent degradation.

Continue to: UV light therapy

UV light therapy is often used in cases refractory to topical therapy. Patients are typically prescribed 2 to 3 treatments per week with narrowband UVB (311-313 nm), the excimer laser (308 nm), or, less commonly, PUVA (UV treatment with psoralens). Treatment begins with a minimal erythema dose—the lowest dose to achieve minimal erythema of the skin before burning. When that is determined, exposure is increased as needed—depending on the response. If this is impractical or too time-consuming for the patient, an alternative recommendation would be increased exposure to natural sunlight or even use of a tanning booth. However, patients must then be cautioned about the increased risk of skin cancer.

Refractory/severe psoriasis

Patient B is a 35-year-old man with a longstanding history of psoriasis affecting his scalp and nails. Over the past 10 years, psoriatic lesions have also appeared and grown across his lower back, gluteal fold, legs, abdomen, and arms. He is now being evaluated by a rheumatologist for worsening symmetric joint pain that includes his lower back.

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis since the 1950s. Methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase and is typically given as an oral medication dosed once weekly with folic acid supplementation on the other 6 days.17 The most common adverse effects encountered with methotrexate are gastrointestinal upset and oral ulcers; however, routine monitoring for myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity is required.

Biologic therapy. When conventional therapies fail, immune-targeted treatment with “biologics” may be initiated. As knowledge of signaling pathways and the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis has increased, so has the number of biologic agents, which are generally well tolerated and effective in managing plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Although their use, which requires monitoring, is handled primarily by specialists, familiarizing yourself with available agents can be helpful (TABLE).22

Nutritional modification and supplementation in treating skin disease still requires further investigation. Fish oil has shown benefit for cutaneous psoriasis in randomized controlled trials.7,8 Oral vitamin D supplementation requires further study, whereas selenium and B12 supplementation have not conferred consistent benefit.7 Given that several studies have demonstrated a relationship between body mass index and psoriatic disease severity, weight loss may be helpful in the management of psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis.8

Continue to: Other systemic agents

Other systemic agents—for individuals who cannot tolerate the biologic agents—include acitretin, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.15,17

Paradoxical psoriatic reactions

When a psoriatic condition develops during biologic drug therapy, it is known as a paradoxical psoriatic reaction. The onset of de novo psoriasis has been documented during TNF-α inhibitor therapy for individuals with underlying rheumatoid arthritis.23 Skin biopsy reveals the same findings as common plaque psoriasis.

Using immunosuppressive Tx? Screen for tuberculosis

Testing to exclude a diagnosis of latent or undiagnosed tuberculosis must be performed prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate or a biologic agent. Tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold test, and the T-SPOT.TB test are accepted screening modalities. Discordance between tuberculin skin tests and the interferon gamma release assays in latent TB highlights the need for further study using the available QuantiFERON-TB gold test and the T-SPOT.TB test.24

CORRESPONDENCE

Karl T. Clebak, MD, FAAFP, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; kclebak@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

The “heartbreak of psoriasis,” coined by an advertiser in the 1960s, conveyed the notion that this disease was a cosmetic disorder mainly limited to skin involvement. John Updike’s article in the September 1985 issue of The New Yorker, “At War With My Skin,” detailed Mr. Updike’s feelings of isolation and stress related to his condition, helping to reframe the popular concept of psoriasis.1 Updike’s eloquent account describing his struggles to find effective treatment increased public awareness about psoriasis, which in fact affects other body systems as well.

The overall prevalence of psoriasis is 1.5% to 3.1% in the United States and United Kingdom.2,3 More than 6.5 million adults in the United States > 20 years of age are affected.3 The most commonly affected demographic group is non-Hispanic Caucasians.

Our expanding knowledge of pathogenesis

Studies of genetic linkage have identified genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with psoriasis.4 The interaction between environmental triggers and the innate and adaptive immune systems leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL) 23, and IL-17 are important cytokines associated with psoriatic inflammation.4 There are common pathways of inflammation in both psoriasis and cardiovascular disease resulting in oxidative stress and endothelial cell dysfunction.4 Ninety percent of early-onset psoriasis is associated with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6.4 And alterations in the microbiome of the skin may contribute, as reduced microbial diversity has been found in psoriatic lesions.5

Comorbidities are common

Psoriasis is an independent risk factor for diabetes and major adverse cardiovascular events.6 Hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and lymphoma (particularly cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) are also associated with psoriasis.6 Psoriatic arthritis is frequently encountered with cutaneous psoriasis; however, it is often not recognized until late in the disease course.

There also appears to be an association among psoriasis, dietary factors, and celiac disease.7-9 Positive testing for IgA anti-endomysial antibodies and IgA tissue transglutaminase antibodies should prompt consideration of starting a gluten-free diet, which has been shown to improve psoriatic

The different types of psoriasis

The classic presentation of psoriasis involves stubborn plaques with silvery scale on extensor surfaces such as the elbows and knees. The severity of the disease corresponds with the amount of body surface area affected. While plaque-type psoriasis is the most common form, other patterns exist. Individuals may exhibit 1 dominant pattern or multiple psoriatic variants simultaneously. Most types of psoriasis have 3 characteristic features: erythema, skin thickening, and scales.

Certain history and physical clues can aid in diagnosing psoriasis; these include the Koebner phenomenon, the Auspitz sign, and the Woronoff ring. The Koebner phenomenon refers to the development of psoriatic lesions in an area of trauma (FIGURE 1), frequently resulting in a linear streak-like appearance. The Auspitz sign describes the pinpoint bleeding that may be encountered with the removal of a psoriatic plaque. The Woronoff ring is a pale blanching ring that may surround a psoriatic lesion.

Continue to: Chronic plaque-type psoriasis

Chronic plaque-type psoriasis (Figures 2A and 2B), the most common variant, is characterized by sharply demarcated pink papules and plaques with a silvery scale in a symmetric distribution on the extensor surfaces, scalp, trunk, and lumbosacral areas.

Guttate psoriasis (FIGURE 3) features small (often < 1 cm) pink scaly papules that appear suddenly. It is more commonly seen in children and is usually preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection, often with Streptococcus.10 If strep testing is positive, guttate psoriasis may improve after appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Erythrodermic psoriasis (FIGUREs 4A and 4B) involves at least 75% of the body with erythema and scaling.11 Erythroderma can be caused by many other conditions such as atopic dermatitis, a drug reaction, Sezary syndrome, seborrheic dermatitis, and pityriasis rubra pilaris. Treatments for other conditions in the differential diagnosis can potentially make psoriasis worse. Unfortunately, findings on a skin biopsy are often nonspecific, making careful clinical observation crucial to arriving at an accurate diagnosis.

Pustular psoriasis is characterized by bright erythema and sterile pustules. Pustular psoriasis can be triggered by pregnancy, sudden tapering of corticosteroids, hypocalcemia, and infection. Involvement of the palms and soles with severe desquamation can drastically impact daily functioning and quality of life.

Inverse or flexural psoriasis (FIGUREs 5A and 5B) is characterized by shiny, pink-to-red sharply demarcated plaques involving intertriginous areas, typically the groin, inguinal crease, axilla, inframammary regions, and intergluteal cleft.

Continue to: Geographic tongue

Geographic tongue describes psoriasis of the tongue. The mucosa of the tongue has white plaques with a geographic border. Instead of scale, the moisture on the tongue causes areas of hyperkeratosis that appear white.

Nail psoriasis can manifest as nail pitting (FIGURE 6), oil staining, onycholysis (distal lifting of the nail), and subungual hyperkeratosis. Nail psoriasis is often quite distressing for patients and can be difficult to treat.

Palmoplantar psoriasis (FIGUREs 7A and 7B) can be painful due to the involvement of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Lesions will either be similar to other psoriatic plaques with well-demarcated erythematous scaling lesions or involve thickening and scale without associated erythema.

Psoriatic arthritis can cause significant joint damage and disability. Most affected individuals with psoriatic arthritis have a history of preceding skin disease.12 There are no specific lab tests for psoriasis; radiologic studies can show bulky syndesmophytes, central and marginal erosions, and periostitis. Patterns of joint involvement are variable. Psoriatic arthritis is more likely to affect the distal interphalangeal joints than rheumatoid arthritis and is more likely to affect the metacarpophalangeal joints than osteoarthritis.13

Psoriatic arthritis often progresses insidiously and is commonly described as causing discomfort rather than acute pain. Enthesitis, inflammation at the site where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone, is often present. Joint destruction may lead to the telescoping “opera glass” digit (FIGURE 8).

Continue to: Drug-provoked psoriasis

Drug-provoked psoriasis is divided into 2 groups: drug-induced and drug-aggravated. Drug-induced psoriasis will improve after discontinuation of the causative drug and tends to occur in patients without a personal or family history of psoriasis. Drug-aggravated psoriasis continues to progress after the discontinuation of the offending drug and is more often seen in patients with a history of psoriasis.14 Drugs that most commonly provoke psoriasis are beta-blockers, lithium, and antimalarials.10 Other potentially aggravating agents include antibiotics, digoxin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10

Consider these skin disorders in the differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of psoriasis is usually clinical, and a skin biopsy is rarely needed. However, a range of other skin disorders should be kept in mind when considering the differential diagnosis.

Mycosis fungoides is a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that forms erythematous plaques that may show wrinkling and epidermal atrophy in sun-protected sites. Onset usually occurs among the elderly.

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is characterized by salmon-colored patches that may have small areas of normal skin (“islands of sparing”), hyperkeratotic follicular papules, and hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles.

Seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff of the skin, usually involves the scalp and nasolabial areas and the T-zone of the face.

Continue to: Lichen planus

Lichen planus usually appears slightly more purple than psoriasis and typically involves the mouth, flexural surfaces of the wrists, genitals, and ankles.

Other conditions in the differential include pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which may be identified on skin biopsy. Inverse psoriasis can be difficult to differentiate from candida intertrigo, erythrasma, or tinea cruris.

A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation can help differentiate psoriasis from candida or tinea. In psoriasis, a KOH test will be negative for fungal elements. Mycology culture on skin scrapings may be performed to rule out fungal infection. Erythrasma may exhibit a coral red appearance under Wood lamp examination.

If a lesion fails to respond to appropriate treatment, a careful drug history and biopsy can help clarify the diagnosis.

Document disease

It’s important to thoroughly document the extent and severity of the psoriasis and to monitor the impact of treatment. The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index is a commonly used method that calculates a score based on the area (extent) of involvement surrounding 4 major anatomical regions (head, upper extremities, trunk, and lower extremities), as well as the degree of erythema, induration, and scaling of lesions. The average redness, thickness, and scaling are graded on a scale of 0 to 4 and the extent of involvement is calculated to form a total numerical score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 72 (maximal disease).

Continue to: Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many options in the treatment arsenal

Many treatments can improve psoriasis.9,15-19 Most affected individuals discover that emollients and exposure to natural sunlight can be effective, as are soothing baths (balneotherapy) or topical coal tar application. More persistent disease requires prescription therapy. Individualize therapy according to the severity of disease, location of the lesions, involvement of joints, and comorbidities (FIGURE 9).15

If ≤ 10% of the body surface area is involved, treatment options generally are explored in a stepwise progression from safest and most affordable to more involved therapies as needed: moisturization and avoidance of repetitive trauma, topical corticosteroids (TCS), vitamin D analogs, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and vitamin A creams. Recalcitrant disease will likely require ultraviolet (UV) light treatment or a systemic agent.15

If > 10% of the body surface area is involved, but joints are not involved, consider UV light treatment or a combination of alcitretin and TCS. If the joints are involved, likely initial options would be methotrexate, cyclosporine, or TNF-α inhibitor. Additional options to consider are anti-IL-17 or anti-IL-23 agents.15

If there’s joint involvement. In individuals with mild peripheral arthritis involving fewer than 4 joints without evidence of joint damage on imaging, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment. If the peripheral arthritis persists, or if it is associated with moderate-to-severe erosions or with substantial functional limitations, initiate treatment with a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. If the disease remains active, consider biologic agents.

Case studies

Mild-to-moderate psoriasis

Patient A is a 19-year-old woman presenting for evaluation of a persistently dry, flaking scalp. She has had the itchy scalp for years, as well as several small “patches” across her elbows, legs, knees, and abdomen. Over-the-counter emollients have not helped. The patient also says she has had brittle nails on several of her fingers, which she keeps covered with thick polish.

Continue to: The condition exemplified...

The condition exemplified by Patient A can typically be managed with topical products.

Topical steroids may be classified by different delivery vehicles, active ingredients, and potencies. The National Psoriasis Foundation's Topical Steroids Potency Chart can provide guidance (visit www.psoriasis.org/about-psoriasis/treatments/topicals/steroids/potency-chart and scroll down). Prescribing an appropriate amount is important; the standard 30-g prescription tube is generally required to cover the entire skin surface. Ointments have a greasy consistency (typically a petroleum base), which enhances potency and hydrates the skin. Creams and lotions are easier to rub on and spread. Gels are alcohol based and readily absorbed.16 Solutions, foams, and shampoos are particularly useful to treat psoriasis in hairy areas such as the scalp.

Corticosteroid potency ranges from Class I to Class VII, with the former being the most potent. While TCS products are typically effective with minimal systemic absorption, it is important to counsel patients on the risk of skin atrophy, impaired wound healing, and skin pigmentation changes with chronic use. With nail psoriasis, a potent topical steroid (including flurandrenolide [Cordran] tape) applied to the proximal nail fold has shown benefit.20

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs; eg, tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream) are anti-inflammatory agents often used in conjunction with topical steroids to minimize steroid use and associated adverse effects.15 A possible steroid-sparing regimen includes using a TCI Monday through Friday and a topical steroid on the weekend.

Topical vitamin D analogs (calcipotriene, calcipotriol, calcitriol) inhibit proliferation of keratinocytes and decrease the production of inflammatory mediators.15,17-19,21 Application of a vitamin D analog in combination with a high-potency TCS, systemic treatment, or phototherapy can provide greater efficacy, a more rapid onset of action, and less irritation than can the vitamin D analog used alone.21 If used in combination with UV light, apply topical vitamin D after the light therapy to prevent degradation.

Continue to: UV light therapy

UV light therapy is often used in cases refractory to topical therapy. Patients are typically prescribed 2 to 3 treatments per week with narrowband UVB (311-313 nm), the excimer laser (308 nm), or, less commonly, PUVA (UV treatment with psoralens). Treatment begins with a minimal erythema dose—the lowest dose to achieve minimal erythema of the skin before burning. When that is determined, exposure is increased as needed—depending on the response. If this is impractical or too time-consuming for the patient, an alternative recommendation would be increased exposure to natural sunlight or even use of a tanning booth. However, patients must then be cautioned about the increased risk of skin cancer.

Refractory/severe psoriasis

Patient B is a 35-year-old man with a longstanding history of psoriasis affecting his scalp and nails. Over the past 10 years, psoriatic lesions have also appeared and grown across his lower back, gluteal fold, legs, abdomen, and arms. He is now being evaluated by a rheumatologist for worsening symmetric joint pain that includes his lower back.

Methotrexate has been used to treat psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis since the 1950s. Methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase and is typically given as an oral medication dosed once weekly with folic acid supplementation on the other 6 days.17 The most common adverse effects encountered with methotrexate are gastrointestinal upset and oral ulcers; however, routine monitoring for myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity is required.

Biologic therapy. When conventional therapies fail, immune-targeted treatment with “biologics” may be initiated. As knowledge of signaling pathways and the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis has increased, so has the number of biologic agents, which are generally well tolerated and effective in managing plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Although their use, which requires monitoring, is handled primarily by specialists, familiarizing yourself with available agents can be helpful (TABLE).22

Nutritional modification and supplementation in treating skin disease still requires further investigation. Fish oil has shown benefit for cutaneous psoriasis in randomized controlled trials.7,8 Oral vitamin D supplementation requires further study, whereas selenium and B12 supplementation have not conferred consistent benefit.7 Given that several studies have demonstrated a relationship between body mass index and psoriatic disease severity, weight loss may be helpful in the management of psoriasis as well as psoriatic arthritis.8

Continue to: Other systemic agents

Other systemic agents—for individuals who cannot tolerate the biologic agents—include acitretin, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine.15,17

Paradoxical psoriatic reactions

When a psoriatic condition develops during biologic drug therapy, it is known as a paradoxical psoriatic reaction. The onset of de novo psoriasis has been documented during TNF-α inhibitor therapy for individuals with underlying rheumatoid arthritis.23 Skin biopsy reveals the same findings as common plaque psoriasis.

Using immunosuppressive Tx? Screen for tuberculosis

Testing to exclude a diagnosis of latent or undiagnosed tuberculosis must be performed prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate or a biologic agent. Tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold test, and the T-SPOT.TB test are accepted screening modalities. Discordance between tuberculin skin tests and the interferon gamma release assays in latent TB highlights the need for further study using the available QuantiFERON-TB gold test and the T-SPOT.TB test.24

CORRESPONDENCE

Karl T. Clebak, MD, FAAFP, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; kclebak@pennstatehealth.psu.edu.

1. Jackson R. John Updike on psoriasis. At war with my skin, from the journal of a leper. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:113-115.

2. Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537-1541.

3. Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003-2006 and 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:37-45.

4. Alexander H, Nestle FO. Pathogenesis and immunotherapy in cutaneous psoriasis: what can rheumatologists learn? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:71-78.

5. Fahlén A, Engstrand L, Baker BS, et al. Comparison of bacterial microbiota in skin biopsies from normal and psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:15-22.

6. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

7. Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part III: role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:561-569.

8. Debbaneh M, Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part I: impact of weight loss interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:133-140.

9. Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350-358.

10. Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606-615.

11. Singh RK, Lee KM, Ucmak D, et al. Erythrodermic psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Aukl). 2016;6:93-104.

12. Garg A, Gladman D. Recognizing psoriatic arthritis in the dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:733-748.

13. McGonagle D, Hermann KG, Tan AL. Differentiation between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: implications for pathogenesis and treatment in the biologic therapy era. Rheumatology. 2015;54:29-38.

14. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Drug-provoked psoriasis: is it drug induced or drug aggravated?: understanding pathophysiology and clinical relevance. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:32-38.

15. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:787-801.

16. Helm MF, Farah JB, Carvalho M, et al. Compounded topical medications for diseases of the skin: a long tradition still relevant today. N Am J Med Sci. 2017;10:116-118.

17. Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:626-633.

18. Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Kang S. Topical vitamin D3. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007:691-695.

19. Lebwohl M, Siskin SB, Epinette W, et al. A multicenter trial of calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment compared with either agent alone for the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:268-269.

20. Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis: a review of treatment options. Drugs. 2016;76:675-705.

21. Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

22. Rønholt K, Iversen L. Old and new biological therapies for psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:e2297.

23. Toussirot É, Aubin F. Paradoxical reactions under TNF-alpha blocking agents and other biologic agents given for chronic immune-mediated diseases: an analytical and comprehensive overview. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000239.

24. Connell TG, Ritz N, Paxton GA, et al. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold and T-SPOT.TB in children. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2624.

1. Jackson R. John Updike on psoriasis. At war with my skin, from the journal of a leper. J Cutan Med Surg. 2000;4:113-115.

2. Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and treatment of psoriasis in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1537-1541.

3. Helmick CG, Lee-Han H, Hirsch SC, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the U.S.: 2003-2006 and 2009-2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:37-45.

4. Alexander H, Nestle FO. Pathogenesis and immunotherapy in cutaneous psoriasis: what can rheumatologists learn? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017;29:71-78.

5. Fahlén A, Engstrand L, Baker BS, et al. Comparison of bacterial microbiota in skin biopsies from normal and psoriatic skin. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:15-22.

6. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377-390.

7. Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part III: role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:561-569.

8. Debbaneh M, Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part I: impact of weight loss interventions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:133-140.

9. Bhatia BK, Millsop JW, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis, part II: celiac disease and role of a gluten-free diet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:350-358.

10. Fry L, Baker BS. Triggering psoriasis: the role of infections and medications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:606-615.

11. Singh RK, Lee KM, Ucmak D, et al. Erythrodermic psoriasis: pathophysiology and current treatment perspectives. Psoriasis (Aukl). 2016;6:93-104.

12. Garg A, Gladman D. Recognizing psoriatic arthritis in the dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:733-748.

13. McGonagle D, Hermann KG, Tan AL. Differentiation between osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis: implications for pathogenesis and treatment in the biologic therapy era. Rheumatology. 2015;54:29-38.

14. Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Drug-provoked psoriasis: is it drug induced or drug aggravated?: understanding pathophysiology and clinical relevance. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:32-38.

15. Kupetsky EA, Keller M. Psoriasis vulgaris: an evidence-based guide for primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:787-801.

16. Helm MF, Farah JB, Carvalho M, et al. Compounded topical medications for diseases of the skin: a long tradition still relevant today. N Am J Med Sci. 2017;10:116-118.

17. Weigle N, McBane S. Psoriasis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:626-633.

18. Helfrich YR, Sachs DL, Kang S. Topical vitamin D3. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2007:691-695.

19. Lebwohl M, Siskin SB, Epinette W, et al. A multicenter trial of calcipotriene ointment and halobetasol ointment compared with either agent alone for the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:268-269.

20. Pasch MC. Nail psoriasis: a review of treatment options. Drugs. 2016;76:675-705.

21. Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

22. Rønholt K, Iversen L. Old and new biological therapies for psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:e2297.

23. Toussirot É, Aubin F. Paradoxical reactions under TNF-alpha blocking agents and other biologic agents given for chronic immune-mediated diseases: an analytical and comprehensive overview. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000239.

24. Connell TG, Ritz N, Paxton GA, et al. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold and T-SPOT.TB in children. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2624.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider guttate psoriasis if small (often < 1 cm) pink scaly papules appear suddenly, particularly in a child who has an upper respiratory tract infection. C

› Document extent of disease using a tool such as the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, which calculates a score based on the area (extent) of involvement surrounding 4 major anatomical regions. C

› Consider prescribing UV light treatment or a combination of alcitretin and topical corticosteroid if > 10% of the body surface area is involved but joints are not affected. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

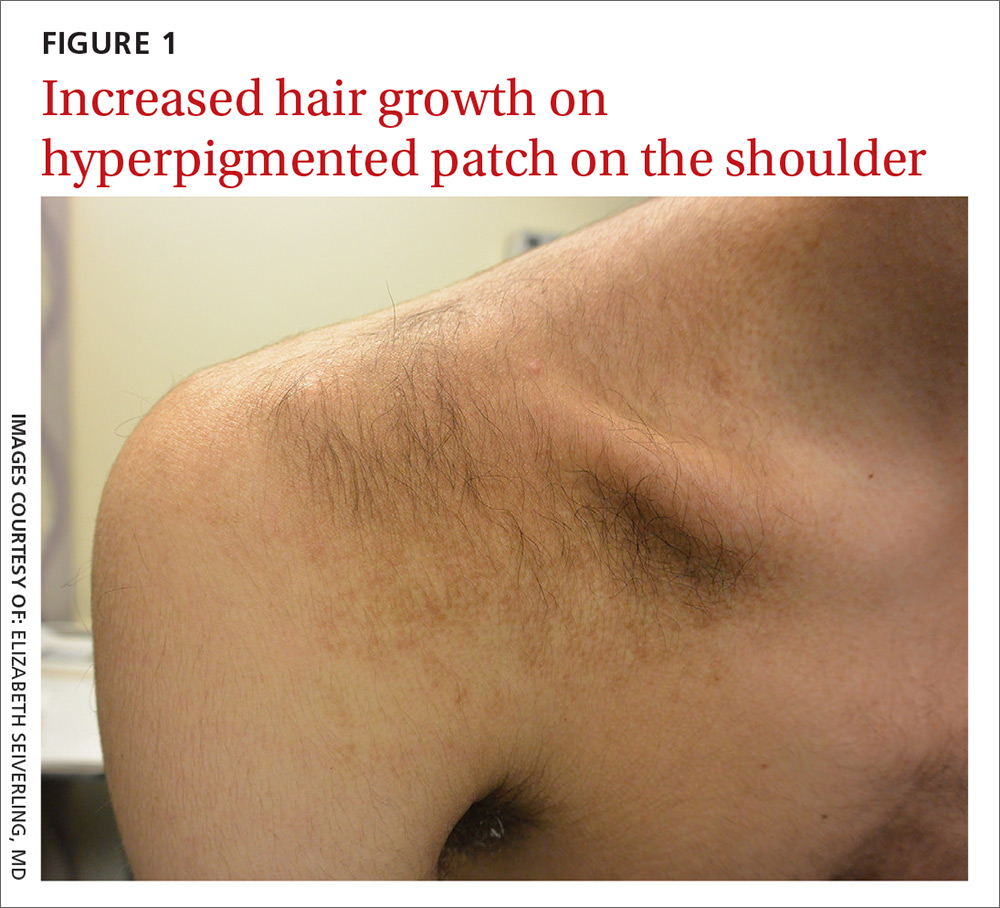

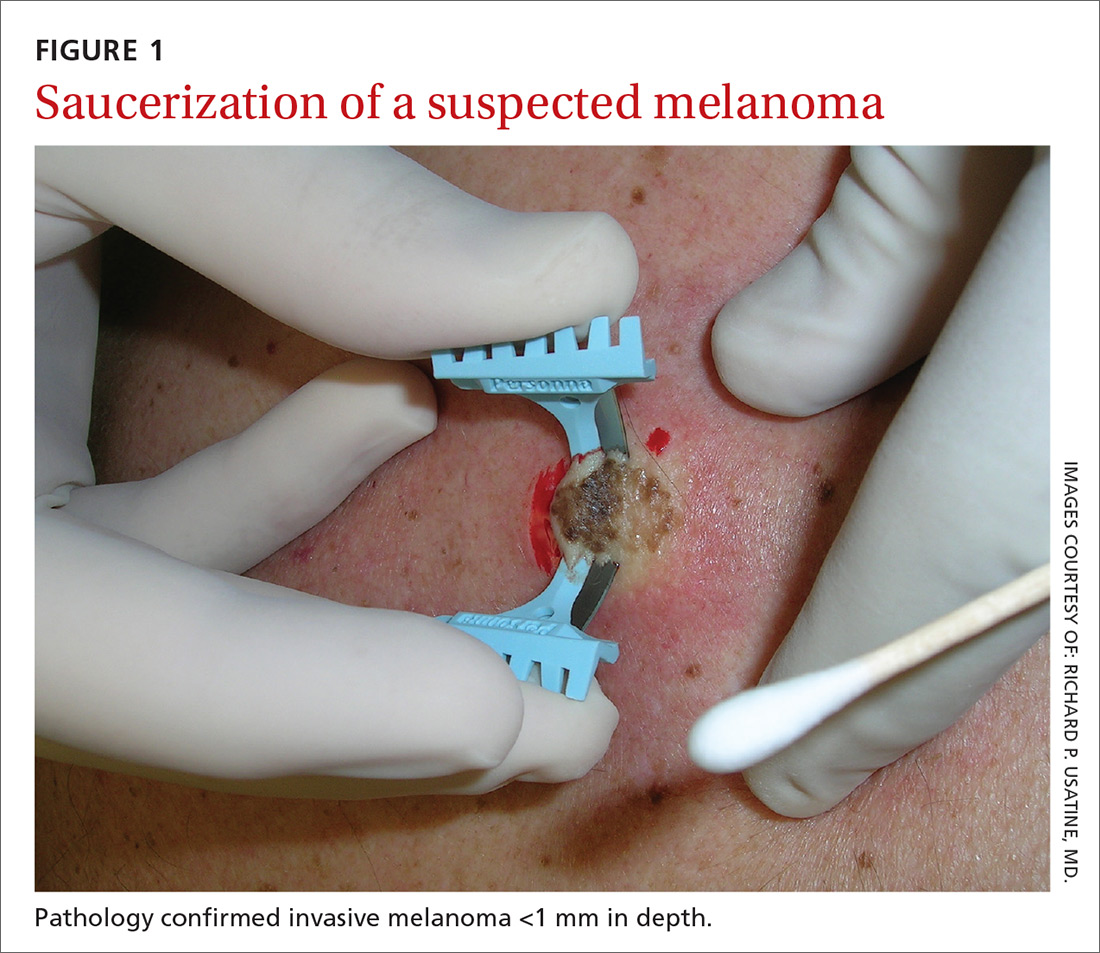

Progressive discoloration over the right shoulder

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

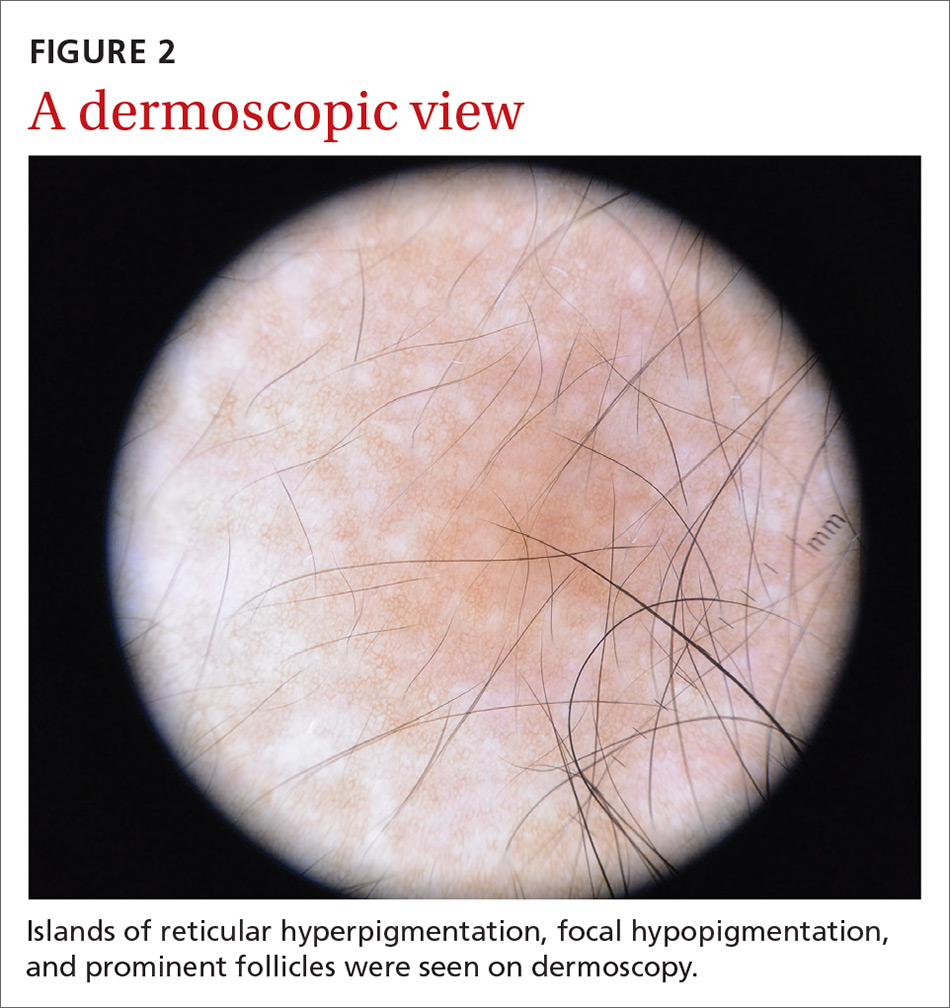

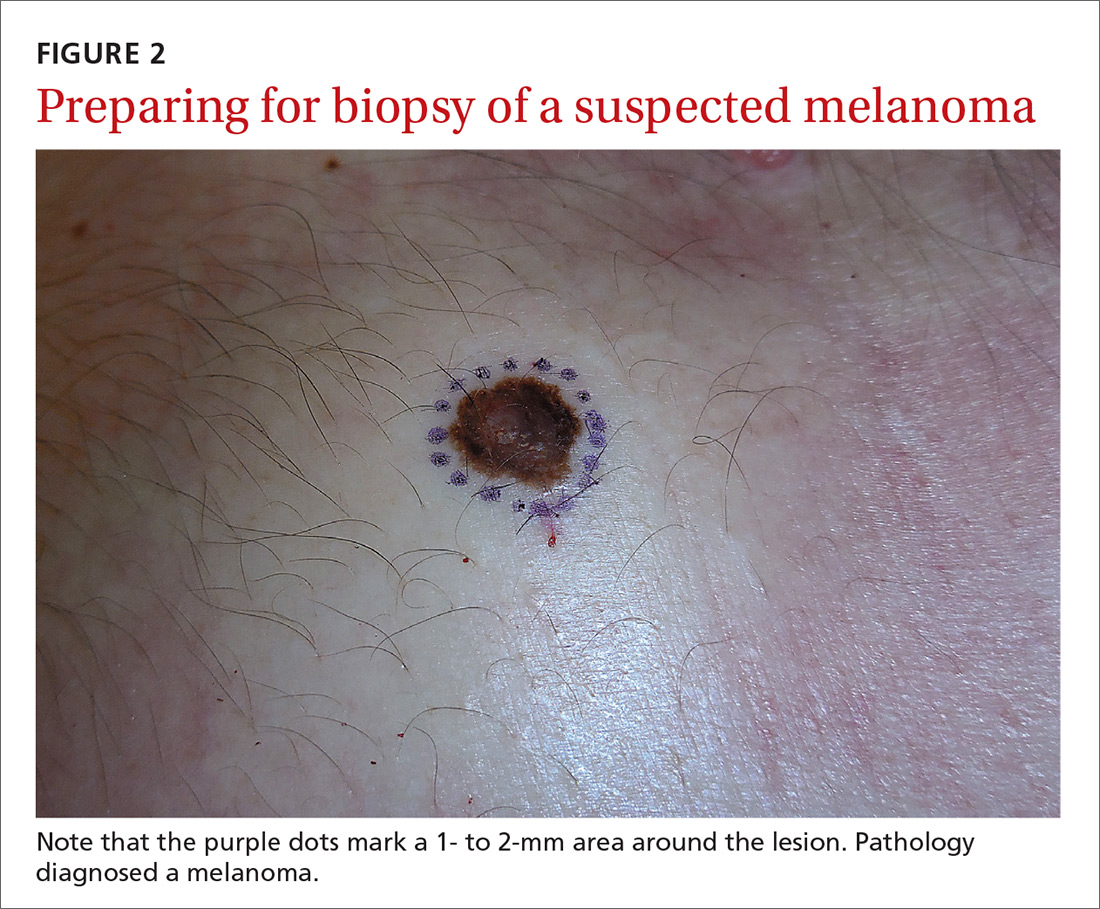

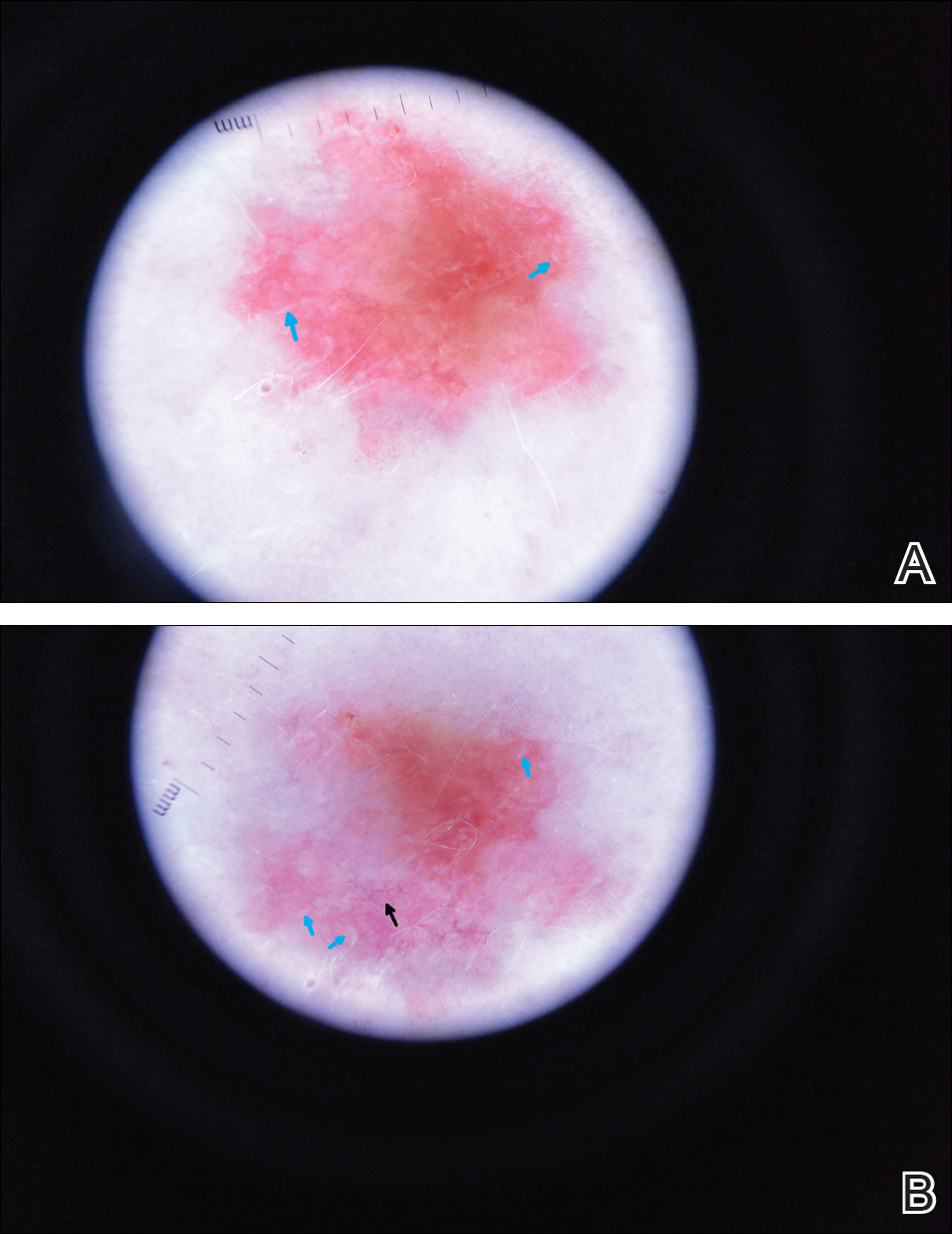

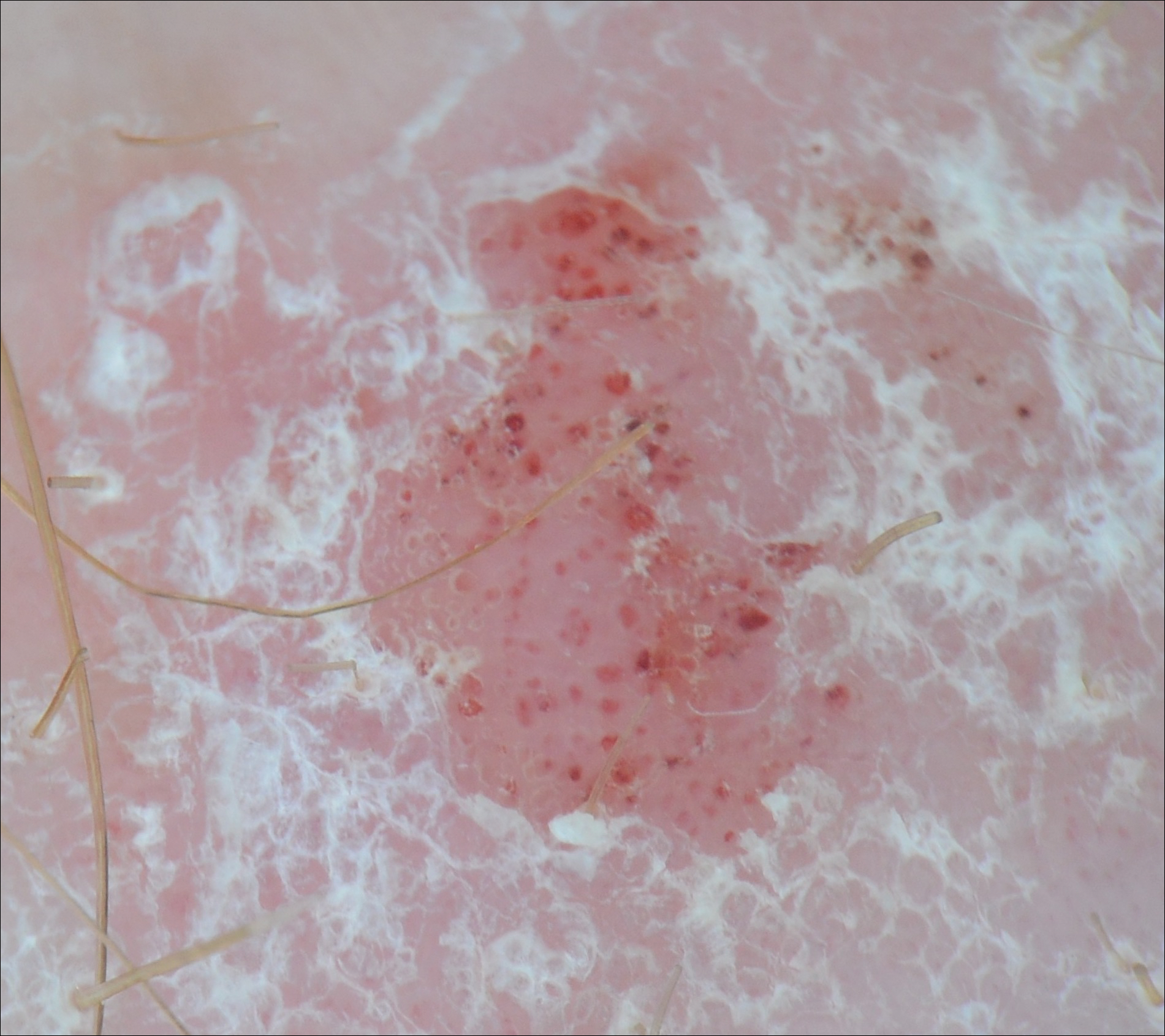

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; Mhelm2@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

1. Rabinovitz HS, Barnhill RL. Benign melanocytic neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2012;112:1853-1854.

2. Person JR, Longcope C. Becker’s nevus: an androgen-mediated hyperplasia with increased androgen receptors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:235-238.

3. Cosendey FE, Martinez NS, Bernhard GA, et al. Becker nevus syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:379-384.

4. Ingordo V, Iannazzone SS, Cusano F, et al. Dermoscopic features of congenital melanocytic nevus and Becker nevus in an adult male population: an analysis with 10-fold magnification. Dermatology. 2006;212:354-360.

5. Luk DC, Lam SY, Cheung PC, et al. Dermoscopy for common skin problems in Chinese children using a novel Hong Kong-made dermoscope. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20:495-503.

6. Balaraman B, Friedman PM. Hypertrichotic Becker’s nevi treated with combination 1,550nm non-ablative fractional photothermolysis and laser hair removal. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:350-353.

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.

Localized post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs following a traumatic event, such as a burn, or a prior dermatosis, such as zoster. Careful history-taking can uncover an antecedent inflammatory condition. Post-inflammatory pigment changes do not typically result in hypertrichosis.

Café-au-lait macules can manifest as isolated areas of discoloration. These macules can be an important indicator of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder in which tumors grow in the nervous system. Melanocytic hamartomas of the iris (Lisch nodules), axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign), or multiple cutaneous neurofibromas serve as additional clues to neurofibromatosis. In ambiguous cases, a skin biopsy can help differentiate a café au lait macule from Becker melanosis.

To treat or not to treat?

No treatment other than reassurance is needed in most cases of Becker melanosis, as it is a benign condition. Protecting the area from sunlight can minimize darkening and contrast with the surrounding skin. Electrolysis and laser therapy can be used to treat the associated hypertrichosis; laser therapy can also reduce the hyperpigmentation. Nonablative fractional resurfacing accompanied by laser hair removal is also reported to be of value.6

Our patient was satisfied with reassurance of the benign nature of the condition and did not elect treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Matthew F. Helm, MD, 500 University Drive, Suite 4300, Department of Dermatology, HU14, UPC II, Hershey, PA 17033-2360; Mhelm2@pennstatehealth.psu.edu

A 15-year-old Caucasian boy presented for evaluation of an asymptomatic brown patch on his right shoulder. While the patient’s mother first noticed the patch when he was 5 years old, the discolored area had recently been expanding in size and had developed hypertrichosis. The patient was otherwise healthy; he took no medications and denied any symptoms or history of trauma to the area. None of his siblings were similarly affected.

A physical examination revealed a well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch with an irregularly shaped border and an increased number of terminal hairs (FIGURE 1). The affected area was not indurated, and there were no muscular or skeletal abnormalities on inspection. Examination of the patch under a dermatoscope revealed islands of reticular (lattice-like) hyperpigmentation, focal hypopigmentation, and prominent follicles (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

DIAGNOSIS: Becker melanosis

Becker melanosis (also called Becker’s nevus or Becker’s pigmentary hamartoma) is an organoid hamartoma that is most common among males.1 This benign area of hyperpigmentation typically manifests as a circumscribed patch with an irregular border on the upper trunk, shoulders, or upper arms of young men. Becker melanosis is usually acquired and typically comes to medical attention around the time of puberty, although there may be a history of discoloration (as was true in this case).

A diagnosis that’s usually made clinically

Androgenic origin. Because of the male predominance and association with hypertrichosis (and for that matter, acne), androgens have been thought to play a role in the development of Becker melanosis.2 The condition affects about 1 in 200 young men.1 To date, no specific gene defect has been identified.

Underlying hypoplasia of the breast or musculoskeletal abnormalities are uncommonly associated with Becker melanosis. When these abnormalities are present, the condition is known as Becker’s nevus syndrome.3

Look for the pattern. Becker melanosis is associated with homogenous brown patches with perifollicular hypopigmentation, sometimes with a faint reticular pattern.4,5 The diagnosis can usually be made clinically, but a skin biopsy can be helpful to confirm questionable cases. Dermoscopy can also assist in diagnosis. In this case, our patient’s presentation was typical, and additional studies were not needed.

Other causes of hyperpigmentation

The differential diagnosis includes other localized disorders associated with hyperpigmentation (TABLE1,3,4).

Continue to: Morphea

Morphea represents a thickening of collagen bundles in the skin. Although morphea can affect the shoulder and trunk, as Becker melanosis does, lesions of morphea feel firm to the touch and are not associated with hypertrichosis.