User login

Itchy Red-Brown Spots on a Child

The Diagnosis: Maculopapular Cutaneous Mastocytosis (Urticaria Pigmentosa)

A stroke test revealed urtication at the exact traumatized site (Figure). A skin biopsy performed 2 years prior by another physician in the same hospital had revealed mast cell infiltration of virtually the entire dermis. The diagnosis was then firmly established as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (CM)(also known as urticaria pigmentosa) with both the pathology results and a confirmative stroke test, and no additional biopsy was attempted. Serum IgE and tryptase levels were within the reference range. General recommendations about the avoidance of trigger factors were given to the family, and a new-generation H1 blocker antihistaminic syrup was prescribed for flushing, itching, and urtication.

Mastocytosis is a canopy term for a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by clonal proliferation and accumulation of abnormal mast cells within the skin and visceral organs (ie, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract). Cutaneous mastocytosis, the skin-restricted variant, is by far the most common form of childhood mastocytosis (90% of mastocytosis cases in children)1 and generally appears within the first 2 years of life.1-7 Pediatric CM usually is a benign and transient disease with an excellent prognosis and a negligible risk for systemic involvement.2,3,5

The pathogenesis of CM in children is obscure1; however, somatic or germline gain-of-function mutations of the c-KIT proto-oncogene, which encodes KIT (ie, a tyrosine kinase membrane receptor for stem cell factor), may account for most pediatric CM phenotypes.1,3,6 Activating c-KIT mutations leads to constitutive activation of the KIT receptor (expressed on the surface membrane of mast cells) and instigates autonomous (stem cell factor– independent) clonal proliferation, enhanced survival, and accumulation of mast cells.2

Maculopapular CM is the most common clinical form of CM.2,4,5 In children, maculopapular CM usually presents with polymorphous red-brown lesions of varying sizes and types—macule, papule, plaque, or nodule—on the torso and extremities.1-5 The distribution may be widespread and rarely is almost universal, as in our patient.2 Darier sign typically is positive, with a wheal and flare developing upon stroking or rubbing 1 or several lesions.1-6 The lesions gradually involute and often spontaneously regress at the time of puberty.1-3,5-7

The clinical signs and symptoms of mastocytosis are not only related to mast cell infiltration but also to mast cell activation within the tissues. The release of intracellular mediators from activated mast cells may have local and/or systemic consequences.4,7 Erythema, edema, flushing, pruritus, urticaria, blistering, and dermatographism are among the local cutaneous symptoms of mast cell activation.2-4,7 Systemic symptoms are rare in childhood CM and consist of wheezing, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, reflux, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypotension, syncope, anaphylaxis, and cyanotic spells.1-7 An elevated serum tryptase level is an indicator of both mast cell burden and risk for mast cell activation in the skin.4,7

Treatment of pediatric CM is conservative and symptomatic.3 Prevention of mediator release may be accomplished through avoidance of trigger factors.1 Alleviation of mediator-related symptoms might be attained using H1 and H2 histamine receptor blockers, oral cromolyn sodium, leukotriene antagonists, and epinephrine autoinjectors.1-3,5 Short-term topical or oral corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors (eg, pimecrolimus, tacrolimus); phototherapy; psoralen plus UVA; omalizumab; and innovative agents such as topical miltefosine, nemolizumab (an IL-31 antagonist), kinase inhibitors such as midostaurin, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib and masitinib may be tried in refractory or extensive pediatric CM.1,2,5,6

Although several disorders in childhood may present with red-brown macules and papules, Darier sign is unique to cutaneous mastocytosis. A biopsy also will be helpful in establishing the definitive diagnosis.

Histiocytosis X (also referred to as Langerhans cell histiocytosis) is the most common proliferative histiocytic disorder. Cutaneous lesions are polymorphic and consist of seborrheic involvement of the scalp with yellow, scaly or crusted papules; eroded patches; pustules; vesicles; petechiae; purpura; or red to purplish papules on the groin, abdomen, back, or chest.8

LEOPARD syndrome (also known as Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines) is an acronym denoting lentigines (multiple), electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of the genitalia, retarded growth, and deafness (sensorineural). The disorder is caused by a genetic mutation involving the PTPN11 gene and currently is categorized under the canopy of RASopathies. Cutaneous findings consist of lentiginous and café-au-lait macules and patches.9

Neurofibromatosis is a genetic disorder with a plethora of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. The type 1 variant that constitutes more than 95% of cases is caused by mutations in the neurofibromin gene. The main cutaneous findings include café-au-lait macules, freckling in axillary and inguinal locations (Crowe sign), and neurofibromas. These lesions may present as macules, patches, papules, or nodules.10

Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare sporadic proliferative histiocyte disorder involving the skin and mucosa. The disorder may be a harbinger of diabetes insipidus. Cutaneous lesions consist of asymptomatic, symmetrical, discrete, erythematous to yellow-brown papules and nodules.11

- Sandru F, Petca RC, Costescu M, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood: update from the literature. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1474. doi:10.3390/jcm10071474

- Lange M, Hartmann K, Carter MC, et al. Molecular background, clinical features and management of pediatric mastocytosis: status 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms22052586

- Castells M, Metcalfe DD, Escribano L. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis in children: practical recommendations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:259-270. doi:10.2165/11588890-000000000-00000

- Nedoszytko B, Arock M, Lyons JJ, et al. Clinical impact of inherited and acquired genetic variants in mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:411. doi:10.3390/ijms22010411

- Nemat K, Abraham S. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood. Allergol Select. 2022;6:1-10. doi:10.5414/ALX02304E

- Giona F. Pediatric mastocytosis: an update. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13:E2021069. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2021.069

- Brockow K, Plata-Nazar K, Lange M, et al. Mediator-related symptoms and anaphylaxis in children with mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2684. doi:10.3390/ijms22052684

- Grana N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Cancer Control. 2014;21: 328-334.

- García-Gil MF, Álvarez-Salafranca M, Valero-Torres A, et al. Melanoma in Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (LEOPARD syndrome): a new case. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:619-621.

- Ozarslan B, Russo T, Argenziano G, et al. Cutaneous findings in neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:463.

- Behra A, Sa DK, Naik R, et al. A rare case of persistent xanthoma disseminatum without any systemic involvement. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:239-241.

The Diagnosis: Maculopapular Cutaneous Mastocytosis (Urticaria Pigmentosa)

A stroke test revealed urtication at the exact traumatized site (Figure). A skin biopsy performed 2 years prior by another physician in the same hospital had revealed mast cell infiltration of virtually the entire dermis. The diagnosis was then firmly established as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (CM)(also known as urticaria pigmentosa) with both the pathology results and a confirmative stroke test, and no additional biopsy was attempted. Serum IgE and tryptase levels were within the reference range. General recommendations about the avoidance of trigger factors were given to the family, and a new-generation H1 blocker antihistaminic syrup was prescribed for flushing, itching, and urtication.

Mastocytosis is a canopy term for a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by clonal proliferation and accumulation of abnormal mast cells within the skin and visceral organs (ie, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract). Cutaneous mastocytosis, the skin-restricted variant, is by far the most common form of childhood mastocytosis (90% of mastocytosis cases in children)1 and generally appears within the first 2 years of life.1-7 Pediatric CM usually is a benign and transient disease with an excellent prognosis and a negligible risk for systemic involvement.2,3,5

The pathogenesis of CM in children is obscure1; however, somatic or germline gain-of-function mutations of the c-KIT proto-oncogene, which encodes KIT (ie, a tyrosine kinase membrane receptor for stem cell factor), may account for most pediatric CM phenotypes.1,3,6 Activating c-KIT mutations leads to constitutive activation of the KIT receptor (expressed on the surface membrane of mast cells) and instigates autonomous (stem cell factor– independent) clonal proliferation, enhanced survival, and accumulation of mast cells.2

Maculopapular CM is the most common clinical form of CM.2,4,5 In children, maculopapular CM usually presents with polymorphous red-brown lesions of varying sizes and types—macule, papule, plaque, or nodule—on the torso and extremities.1-5 The distribution may be widespread and rarely is almost universal, as in our patient.2 Darier sign typically is positive, with a wheal and flare developing upon stroking or rubbing 1 or several lesions.1-6 The lesions gradually involute and often spontaneously regress at the time of puberty.1-3,5-7

The clinical signs and symptoms of mastocytosis are not only related to mast cell infiltration but also to mast cell activation within the tissues. The release of intracellular mediators from activated mast cells may have local and/or systemic consequences.4,7 Erythema, edema, flushing, pruritus, urticaria, blistering, and dermatographism are among the local cutaneous symptoms of mast cell activation.2-4,7 Systemic symptoms are rare in childhood CM and consist of wheezing, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, reflux, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypotension, syncope, anaphylaxis, and cyanotic spells.1-7 An elevated serum tryptase level is an indicator of both mast cell burden and risk for mast cell activation in the skin.4,7

Treatment of pediatric CM is conservative and symptomatic.3 Prevention of mediator release may be accomplished through avoidance of trigger factors.1 Alleviation of mediator-related symptoms might be attained using H1 and H2 histamine receptor blockers, oral cromolyn sodium, leukotriene antagonists, and epinephrine autoinjectors.1-3,5 Short-term topical or oral corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors (eg, pimecrolimus, tacrolimus); phototherapy; psoralen plus UVA; omalizumab; and innovative agents such as topical miltefosine, nemolizumab (an IL-31 antagonist), kinase inhibitors such as midostaurin, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib and masitinib may be tried in refractory or extensive pediatric CM.1,2,5,6

Although several disorders in childhood may present with red-brown macules and papules, Darier sign is unique to cutaneous mastocytosis. A biopsy also will be helpful in establishing the definitive diagnosis.

Histiocytosis X (also referred to as Langerhans cell histiocytosis) is the most common proliferative histiocytic disorder. Cutaneous lesions are polymorphic and consist of seborrheic involvement of the scalp with yellow, scaly or crusted papules; eroded patches; pustules; vesicles; petechiae; purpura; or red to purplish papules on the groin, abdomen, back, or chest.8

LEOPARD syndrome (also known as Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines) is an acronym denoting lentigines (multiple), electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of the genitalia, retarded growth, and deafness (sensorineural). The disorder is caused by a genetic mutation involving the PTPN11 gene and currently is categorized under the canopy of RASopathies. Cutaneous findings consist of lentiginous and café-au-lait macules and patches.9

Neurofibromatosis is a genetic disorder with a plethora of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. The type 1 variant that constitutes more than 95% of cases is caused by mutations in the neurofibromin gene. The main cutaneous findings include café-au-lait macules, freckling in axillary and inguinal locations (Crowe sign), and neurofibromas. These lesions may present as macules, patches, papules, or nodules.10

Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare sporadic proliferative histiocyte disorder involving the skin and mucosa. The disorder may be a harbinger of diabetes insipidus. Cutaneous lesions consist of asymptomatic, symmetrical, discrete, erythematous to yellow-brown papules and nodules.11

The Diagnosis: Maculopapular Cutaneous Mastocytosis (Urticaria Pigmentosa)

A stroke test revealed urtication at the exact traumatized site (Figure). A skin biopsy performed 2 years prior by another physician in the same hospital had revealed mast cell infiltration of virtually the entire dermis. The diagnosis was then firmly established as maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (CM)(also known as urticaria pigmentosa) with both the pathology results and a confirmative stroke test, and no additional biopsy was attempted. Serum IgE and tryptase levels were within the reference range. General recommendations about the avoidance of trigger factors were given to the family, and a new-generation H1 blocker antihistaminic syrup was prescribed for flushing, itching, and urtication.

Mastocytosis is a canopy term for a heterogeneous group of disorders caused by clonal proliferation and accumulation of abnormal mast cells within the skin and visceral organs (ie, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract). Cutaneous mastocytosis, the skin-restricted variant, is by far the most common form of childhood mastocytosis (90% of mastocytosis cases in children)1 and generally appears within the first 2 years of life.1-7 Pediatric CM usually is a benign and transient disease with an excellent prognosis and a negligible risk for systemic involvement.2,3,5

The pathogenesis of CM in children is obscure1; however, somatic or germline gain-of-function mutations of the c-KIT proto-oncogene, which encodes KIT (ie, a tyrosine kinase membrane receptor for stem cell factor), may account for most pediatric CM phenotypes.1,3,6 Activating c-KIT mutations leads to constitutive activation of the KIT receptor (expressed on the surface membrane of mast cells) and instigates autonomous (stem cell factor– independent) clonal proliferation, enhanced survival, and accumulation of mast cells.2

Maculopapular CM is the most common clinical form of CM.2,4,5 In children, maculopapular CM usually presents with polymorphous red-brown lesions of varying sizes and types—macule, papule, plaque, or nodule—on the torso and extremities.1-5 The distribution may be widespread and rarely is almost universal, as in our patient.2 Darier sign typically is positive, with a wheal and flare developing upon stroking or rubbing 1 or several lesions.1-6 The lesions gradually involute and often spontaneously regress at the time of puberty.1-3,5-7

The clinical signs and symptoms of mastocytosis are not only related to mast cell infiltration but also to mast cell activation within the tissues. The release of intracellular mediators from activated mast cells may have local and/or systemic consequences.4,7 Erythema, edema, flushing, pruritus, urticaria, blistering, and dermatographism are among the local cutaneous symptoms of mast cell activation.2-4,7 Systemic symptoms are rare in childhood CM and consist of wheezing, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, reflux, abdominal cramping, diarrhea, tachycardia, hypotension, syncope, anaphylaxis, and cyanotic spells.1-7 An elevated serum tryptase level is an indicator of both mast cell burden and risk for mast cell activation in the skin.4,7

Treatment of pediatric CM is conservative and symptomatic.3 Prevention of mediator release may be accomplished through avoidance of trigger factors.1 Alleviation of mediator-related symptoms might be attained using H1 and H2 histamine receptor blockers, oral cromolyn sodium, leukotriene antagonists, and epinephrine autoinjectors.1-3,5 Short-term topical or oral corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors (eg, pimecrolimus, tacrolimus); phototherapy; psoralen plus UVA; omalizumab; and innovative agents such as topical miltefosine, nemolizumab (an IL-31 antagonist), kinase inhibitors such as midostaurin, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as imatinib and masitinib may be tried in refractory or extensive pediatric CM.1,2,5,6

Although several disorders in childhood may present with red-brown macules and papules, Darier sign is unique to cutaneous mastocytosis. A biopsy also will be helpful in establishing the definitive diagnosis.

Histiocytosis X (also referred to as Langerhans cell histiocytosis) is the most common proliferative histiocytic disorder. Cutaneous lesions are polymorphic and consist of seborrheic involvement of the scalp with yellow, scaly or crusted papules; eroded patches; pustules; vesicles; petechiae; purpura; or red to purplish papules on the groin, abdomen, back, or chest.8

LEOPARD syndrome (also known as Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines) is an acronym denoting lentigines (multiple), electrocardiographic conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormalities of the genitalia, retarded growth, and deafness (sensorineural). The disorder is caused by a genetic mutation involving the PTPN11 gene and currently is categorized under the canopy of RASopathies. Cutaneous findings consist of lentiginous and café-au-lait macules and patches.9

Neurofibromatosis is a genetic disorder with a plethora of cutaneous and systemic manifestations. The type 1 variant that constitutes more than 95% of cases is caused by mutations in the neurofibromin gene. The main cutaneous findings include café-au-lait macules, freckling in axillary and inguinal locations (Crowe sign), and neurofibromas. These lesions may present as macules, patches, papules, or nodules.10

Xanthoma disseminatum is a rare sporadic proliferative histiocyte disorder involving the skin and mucosa. The disorder may be a harbinger of diabetes insipidus. Cutaneous lesions consist of asymptomatic, symmetrical, discrete, erythematous to yellow-brown papules and nodules.11

- Sandru F, Petca RC, Costescu M, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood: update from the literature. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1474. doi:10.3390/jcm10071474

- Lange M, Hartmann K, Carter MC, et al. Molecular background, clinical features and management of pediatric mastocytosis: status 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms22052586

- Castells M, Metcalfe DD, Escribano L. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis in children: practical recommendations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:259-270. doi:10.2165/11588890-000000000-00000

- Nedoszytko B, Arock M, Lyons JJ, et al. Clinical impact of inherited and acquired genetic variants in mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:411. doi:10.3390/ijms22010411

- Nemat K, Abraham S. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood. Allergol Select. 2022;6:1-10. doi:10.5414/ALX02304E

- Giona F. Pediatric mastocytosis: an update. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13:E2021069. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2021.069

- Brockow K, Plata-Nazar K, Lange M, et al. Mediator-related symptoms and anaphylaxis in children with mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2684. doi:10.3390/ijms22052684

- Grana N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Cancer Control. 2014;21: 328-334.

- García-Gil MF, Álvarez-Salafranca M, Valero-Torres A, et al. Melanoma in Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (LEOPARD syndrome): a new case. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:619-621.

- Ozarslan B, Russo T, Argenziano G, et al. Cutaneous findings in neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:463.

- Behra A, Sa DK, Naik R, et al. A rare case of persistent xanthoma disseminatum without any systemic involvement. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:239-241.

- Sandru F, Petca RC, Costescu M, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood: update from the literature. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1474. doi:10.3390/jcm10071474

- Lange M, Hartmann K, Carter MC, et al. Molecular background, clinical features and management of pediatric mastocytosis: status 2021. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2586. doi:10.3390/ijms22052586

- Castells M, Metcalfe DD, Escribano L. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis in children: practical recommendations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:259-270. doi:10.2165/11588890-000000000-00000

- Nedoszytko B, Arock M, Lyons JJ, et al. Clinical impact of inherited and acquired genetic variants in mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:411. doi:10.3390/ijms22010411

- Nemat K, Abraham S. Cutaneous mastocytosis in childhood. Allergol Select. 2022;6:1-10. doi:10.5414/ALX02304E

- Giona F. Pediatric mastocytosis: an update. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2021;13:E2021069. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2021.069

- Brockow K, Plata-Nazar K, Lange M, et al. Mediator-related symptoms and anaphylaxis in children with mastocytosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:2684. doi:10.3390/ijms22052684

- Grana N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Cancer Control. 2014;21: 328-334.

- García-Gil MF, Álvarez-Salafranca M, Valero-Torres A, et al. Melanoma in Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines (LEOPARD syndrome): a new case. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2020;111:619-621.

- Ozarslan B, Russo T, Argenziano G, et al. Cutaneous findings in neurofibromatosis type 1. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:463.

- Behra A, Sa DK, Naik R, et al. A rare case of persistent xanthoma disseminatum without any systemic involvement. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:239-241.

A 5-year-old boy presented with red-brown spots diffusely spread over the body that were present since birth. There were no subjective symptoms, except for rare instances of flushing, itching, and urtication following hot baths and abrasive scrubs. Dermatologic examination revealed widespread brown polymorphic macules and papules of varying sizes on the forehead, neck, torso, and extremities. Physical examination was otherwise normal.

Secretan Syndrome: A Fluctuating Case of Factitious Lymphedema

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

Secretan syndrome (SS) represents a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema, usually affecting the dorsal aspect of the hand.1-3 It is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome whereby the patient self-inflicts and simulates lymphedema.1,2 Historically, many of the cases reported with the term Charcot’s oedème bleu are now believed to represent clinical variants of SS.4-6

Case Report

A 38-year-old Turkish woman presented with progressive swelling of the right hand of 2 years’ duration that had caused difficulty in manual work and reduction in manual dexterity. She previously had sought medical treatment for this condition by visiting several hospitals. According to her medical record, the following laboratory or radiologic tests had revealed negative or normal findings, except for obvious soft-tissue edema: bacterial and fungal cultures, plain radiography, Doppler ultrasonography, lymphoscintigraphy, magnetic resonance imaging, fine needle aspiration, and punch biopsy. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, compartment syndrome, filariasis, tuberculosis, and lymphatic and venous obstruction were all excluded by appropriate testing. Our patient was in good health prior to onset of this disorder, and her medical history was unremarkable. There was no family history of a similar condition.

Dermatologic examination revealed brawny, soft, pitting edema; erythema; and crusts affecting the dorsal aspect of the right hand and proximal parts of the fingers (Figure 1). The yellow discoloration of the skin and nails was attributed to potassium permanganate wet dressings. Under an elastic bandage at the wrist, which the patient unrolled herself, a sharp line of demarcation was evident, separating the lymphedematous and normal parts of the arm. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

The patient’s affect was discordant to the manifestation of the cutaneous findings. She wanted to show every physician in the department how swollen her hand was and seemed to be happy with this condition. Although she displayed no signs of disturbance when the affected extremity was touched or handled, she reported severe pain and tenderness as well as difficulty in housework. She noted that she normally resided in a city and that the swelling had started at the time she had relocated to a rural village to take care of her bedridden mother-in-law. She was under an intensive workload in the village, and the condition of the hand was impeding manual work.

Factitious lymphedema was considered, and hospitalization was recommended. The patient was then lost to follow-up; however, one of her relatives noted that the patient had returned to the city. When she presented again 1 year later, almost all physical signs had disappeared (Figure 2), and a psychiatric referral was recommended. A Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory test yielded an invalid result due to the patient’s exaggeration of her preexisting physical symptoms. Further psychiatric workup was rejected by the patient.

Almost a year after the psychiatric referral, the patient’s follow-up photographs revealed that the lymphedema recurred when she went to visit her mother-in-law in the rural village and that it was completely ameliorated when she returned to the city. Thus, a positive “mother-in-law provocation test” was accepted as final proof of the self-inflicted nature of the condition.

Comment

In 1901, Henri Francois Secretan, a Swiss physician, reported workmen who had persistent hard swellings on the dorsal aspect of the hands after minor work-related trauma for which they had compensation claims.7 In his original report, Secretan did not suggest self-inflicted trauma in the etiology of this disorder.5,8,9 In 1890, Jean Martin Charcot, a French neurologist, described oedème bleu, a term that is now believed to denote a condition similar to SS.4-6 Currently, SS is attributed to self-inflicted injury and is considered a form of factitious lymphedema.9 As in dermatitis artefacta, most patients with SS are young women, and male patients with the condition tend to be older.3,8

The mechanism used to provoke this factitious lymphedema might be of traumatic or obstructive nature. Secretan syndrome either is induced by intermittent or constant application of a tourniquet, ligature, cord, elastic bandage, scarf, kerchief, rubber band, or compress around the affected extremity, or by repetitive blunt trauma, force, or skin irritation.1,4,5,8-10 There was an underlying psychopathology in all reported cases.1,8,11 Factitious lymphedema is unconsciously motivated and consciously produced.4,12 The affected patient often is experiencing a serious emotional conflict and is unlikely to be a malingerer, although exaggeration of symptoms may occur, as in our patient.12 Psychiatric evaluation in SS may uncover neurosis, hysteria, frank psychosis, schizophrenia, masochism, depression, or an abnormal personality disorder.1,12

Patients with SS present with recurrent or chronic lymphedema, usually affecting the dominant hand.1 Involvement usually is unilateral; bilateral cases are rare.3,6 Secretan syndrome is not solely limited to the hands; it also may involve the upper and lower extremities, including the feet.3,11 There may be a clear line of demarcation, a ring, sulcus, distinct circumferential linear bands of erythema, discoloration, or ecchymoses, separating the normal and lymphedematous parts of the extremity.1,4,6,8-10,12 Patients usually attempt to hide the constricted areas from sight.1 Over time, flexion contractures may develop due to peritendinous fibrosis.6 Histopathology displays a hematoma with adhesions to the extensor tendons; a hematoma surrounded by a thickened scar; or changes similar to ganglion tissue with cystic areas of mucin, fibrosis, and myxoid degeneration.4,6

Factitious lymphedema can only be definitively diagnosed when the patient confesses or is caught self-inflicting the injury. Nevertheless, a diagnosis by exclusion is possible.4 Lymphangiography, lymphoscintigraphy, vascular Doppler ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging may be helpful in excluding congenital and acquired causes of lymphedema and venous obstruction.1,3,9,11 Magnetic resonance imaging may show soft tissue and tendon edema as well as diffuse peritendinous fibrosis extending to the fascia of the dorsal interosseous muscles.3,4

Factitious lymphedema should be suspected in all patients with recurrent or chronic unilateral lymphedema without an explicable or apparent predisposing factor.4,11,12 Patients with SS typically visit several hospitals or institutions; see many physicians; and willingly accept, request, and undergo unnecessary extensive, invasive, and costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and prolonged hospitalizations.1,2,5,12 The disorder promptly responds to immobilization and elevation of the limb.2,4 Plaster casts may prove useful in prevention of compression and thus amelioration of the lymphedema.1,4,6 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, direct confrontation should be avoided and ideally the patient should be referred for psychiatric evaluation.1,2,4,5,8,12 If the patient admits self-inflicting behavior, psychotherapy and/or behavior modification therapy along with psychotropic medications may be helpful to relieve emotional and behavioral symptoms.12 Unfortunately, if the patient denies a self-inflicting role in the occurrence of lymphedema and persists in self-injurious behavior, psychotherapy or psychotropic medications will be futile.9

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

1. Miyamoto Y, Hamanaka T, Yokoyama S, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the upper limb. Kawasaki Med J. 1979;5:39-45.

2. de Oliveira RK, Bayer LR, Lauxen D, et al. Factitious lesions of the hand. Rev Bras Ortop. 2013;48:381-386.

3. Hahm MH, Yi JH. A case report of Secretan’s disease in both hands. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2013;68:511-514.

4. Eldridge MP, Grunert BK, Matloub HS. Streamlined classification of psychopathological hand disorders: a literature review. Hand (NY). 2008;3:118-128.

5. Ostlere LS, Harris D, Denton C, et al. Boxing-glove hand: an unusual presentation of dermatitis artefacta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:120-122.

6. Winkelmann RK, Barker SM. Factitial traumatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:988-994.

7. Secretan H. Oederne dur et hyperplasie traumatique du metacarpe dorsal. RevMed Suisse Romande. 1901;21:409-416.

8. Barth JH, Pegum JS. The case of the speckled band: acquired lymphedema due to constriction bands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:296-297.

9. Birman MV, Lee DH. Factitious disorders of the upper extremity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:78-85.

10. Nwaejike N, Archbold H, Wilson DS. Factitious lymphoedema as a psychiatric condition mimicking reflex sympathetic dystrophy: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:216.

11. De Fátima Guerreiro Godoy M, Pereira De Godoy JM. Factitious lymphedema of the arm: case report and review of publications. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;51:337-339.

12. Abhari SAA, Alimalayeri N, Abhari SSA, et al. Factitious lymphedema of the hand. Iran J Psychiatry. 2006;1:166-168.

Practice Points

- Secretan syndrome is a recurrent or chronic form of factitious lymphedema that usually affects the dorsal aspect of the hand; it is accepted as a subtype of Munchausen syndrome.

- Secretan syndrome usually is induced by compression of the extremity by tourniquets, ligatures, cords, or similar equipment.

- This unconsciously motivated and consciously produced lymphedema is an expression of underlying psychiatric disease.

Transient Reactive Papulotranslucent Acrokeratoderma: A Report of 3 Cases Showing Excellent Response to Topical Calcipotriene

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

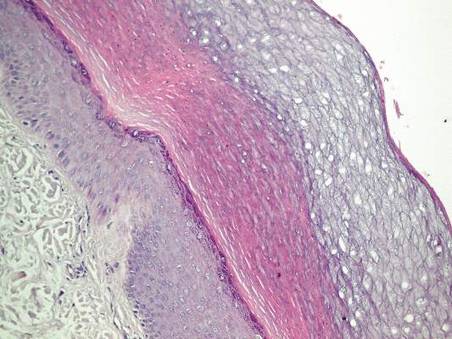

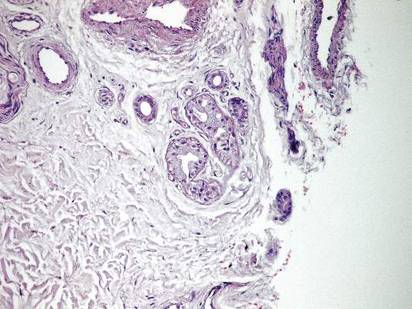

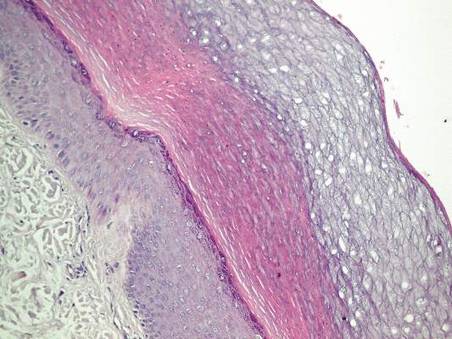

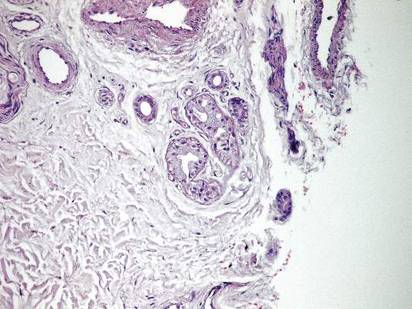

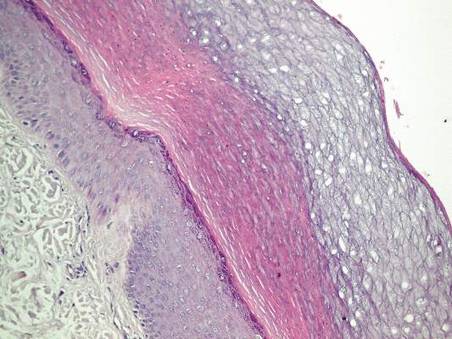

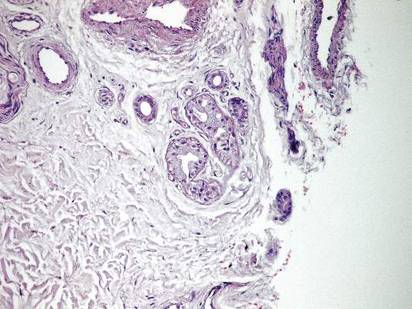

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|  | ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|  | ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

1. Erkek E. Unilateral transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:564-566.

2. English JC 3rd, McCollough ML. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:686-687.

3. Lowes MA, Khaira GS, Holt D. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma associated with cystic fibrosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:172-174.

4. MacCormack MA, Wiss K, Malhotra R. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: report of two teenage cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:124-126.

5. Yoon TY, Kim KR, Lee JY, et al. Aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma: unusual prominence on the dorsal aspect of fingers [published online ahead of print May 22, 2008]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:486-488.

6. Yan AC, Aasi SZ, Alms WJ, et al. Aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:696-699.

7. Diba VC, Cormack GC, Burrows NP. Botulinum toxin is helpful in aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:394-395.

8. Saray Y, Seckin D. Familial aquagenic acrokeratoderma: case reports and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:906-909.

9. Yalcin B, Artuz F, Toy GG, et al. Acquired aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:654-656.

10. Neri I, Bianchi F, Patrizi A. Transient aquagenic palmar hyperwrinkling: the first instance reported in a young boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:39-42.

11. Katz KA, Yan AC, Turner ML. Aquagenic wrinkling of the palms in patients with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the delta F508 CFTR mutation. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:621-624.

12. Kabashima K, Shimauchi T, Kobayashi M, et al. Aberrant aquaporin 5 expression in the sweat gland in aquagenic wrinkling of the palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(suppl 1):S28-S32.

13. Lehmann B, Querings K, Reichrath J. Vitamin D and skin: new aspects for dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13:11-15.

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|  | ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|  | ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

To the Editor:

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma (TRPA) is a rare disorder that also has been described using the terms aquagenic syringeal acrokeratoderma, aquagenic palmoplantar keratoderma, aquagenic acrokeratoderma, aquagenic papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma, and aquagenic wrinkling of the palms.1 It was initially described in 1996 by English and McCollough,2 and since then fewer than 100 cases have been reported.1-12

A 38-year-old man presented with prominent palmar hyperhidrosis with whitish papules on the palms of 10 days’ duration. The lesions were exacerbated following exposure to water but were asymptomatic aside from their unsightly cosmetic appearance. Dermatologic examination revealed translucent, whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases (Figure 1) that were intensified following a 5-minute water immersion test.

Histopathologic examination of a punch biopsy specimen from the right palm revealed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and slight hypergranulosis in the epidermis (Figure 2). Subtle eccrine glandular hyperplasia was evident in the dermis (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. A therapeutic trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated and resulted in dramatic clearance of the lesions within 2 weeks (Figure 4). At 1-month follow-up, the patient was virtually free of all symptoms and no disease recurrence was noted at 5-year follow-up.

|  | ||

Figure 1. Whitish, pebbly papules confined to the central palmar creases in a 38-year-old man. | Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis was noted in the epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). | ||

|  | ||

| Figure 3. Luminal dilatation in the eccrine glands with a prominence of glandular epithelial cells, which displayed abundant cytoplasm with a granular appearance (H&E, original magnification ×100). | Figure 4. Remarkable response to calcipotriene ointment 0.005%. The white punctuate scar indicates the previous punch biopsy site. |

A 25-year-old woman presented with whitish plaques on the palms of 7 days’ duration. She reported frequent use of household cleansers in the month prior to presentation. The lesions were associated with prominent hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and a tingling sensation in the palms. Dermatologic examination revealed confluent, macerated, white, pavement stone–like papules with prominent puncta around the palmar flexures on both palms. Lesions were exacerbated after a 5-minute water immersion test (Figure 5).

The patient refused skin biopsy, and conservative treatment with a barrier cream and limited water exposure were of no benefit. Based on the clinical findings and results of the water immersion test, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Due to the excellent outcome experienced in treating the previous patient, a trial of calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily was initiated, and the patient reported complete resolution of signs and symptoms within the initial 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was terminated at 1-month follow-up.

A 6-year-old boy presented with swollen, itchy palms of 2 months’ duration that the patient described as “wet” and “white.” Due to a recent epidemic of bird flu, the patient’s mother had advised him to use liquid cleansers and antiseptic gels on the hands for the past 2 months, which is when the symptoms on the palms started to develop. On dermatologic examination, whitish, cobblestonelike papules were noted near the palmar creases in association with profuse hyperhidrosis (Figure 6). Based on the clinical findings, a diagnosis of TRPA was made. Biopsy was not attempted and the patient was treated with calcipotriene ointment 0.005% twice daily. At 1-month follow-up, complete clearance of the lesions was noted.

Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma is an acquired and sporadic disorder that can occur in both sexes.2,4,6,8-11 Onset generally occurs during adolescence or young adulthood.1,3,8,9 Clinically, TRPA is characterized by edema and wrinkling of the palms following 5 to 10 minutes of contact with water that typically resolves within 1 hour after cessation of exposure.2,3,6-8,10 The “hand-in-the-bucket” sign refers to accentuation of physical findings upon immersion of the hand in water.6,10,11 Patients frequently report itching, burning, or tingling sensations in the affected areas.2,4,6,7,9,11 Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma usually affects the palms in a diffuse, bilateral, and symmetrical pattern,2,4,6-10 but cases showing involvement of the soles,6,7 marginal distribution of lesions,3 unilateral involvement,1 and prominence on the dorsal fingers5 also have been reported. The natural disease course involves reactive episodes and quiescent intervals.2,7,9 Spontaneous resolution of TRPA has been reported.4,6,8

The histological characteristics described in previous reports involve compact orthohyperkeratosis with dilated acrosyringia,2-6,9,11 hyperkeratosis and hypergranulosis in the epidermis,4,8,12 and eccrine glandular hyperplasia.5,12 Alternatively, the skin may appear completely normal on histology.1,7

Originally, it was proposed that TRPA is a variant of punctate keratoderma or hereditary papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma.2,3 However, its position within the keratoderma spectrum is unclear and the etiopathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Some investigators believe that transient structural and functional alterations in the epidermal milieu prompt epidermal swelling and compensatory dilation of eccrine ducts.3,4,7,8,10 Other reports implicate the inherent structural weakness of eccrine duct walls3,4,11 or aberrations in eccrine glands.5,12 Whether the fundamental pathology lies within the epidermis, eccrine ducts, or the eccrine glands remains to be determined. Nevertheless, reports of TRPA in the setting of cystic fibrosis and its carrier state3,11 as well as the presence of hyperhidrosis in most affected patients and the accumulation of lesions along the palmar creases may implicate oversaturation of the epidermis (due to salt retention or abnormal water absorption by the stratum corneum) as the pivotal event in TRPA pathogenesis.1,10 Once the disease is expressed in susceptible individuals, episodes might be provoked by external factors such as friction, occlusion, sweating, liquid cleansers, antiseptic gels, gloves, topical preparations, and oral medications (eg, salicylic acid, cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors).1,4

Treatment alternatives such as hydrophilic petrolatum and glycerin, ammonium lactate, salicylic acid (with or without urea), aluminum chloride hexahydrate, and topical corticosteroids are limited by unsuccessful or temporary outcomes.1,4,6,8-10 Botulinum toxin injections were effective in a patient with TRPA associated with hyperhidrosis.7 In the cases reported here, topical calcipotriene accomplished dramatic clearance of the lesions within the initial weeks of therapy. Spontaneous resolution was unlikely in these cases, as conservative therapies had not alleviated the signs and symptoms in any of the patients. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that improvement of the skin barrier function associated with other ingredients in the calcipotriene ointment (eg, petrolatum, mineral oil, α-tocopherol) may have led to the resolution of the lesions.

Calcipotriene has demonstrated efficacy in treating cutaneous disorders characterized by epidermal hyperproliferation and impaired terminal differentiation. Immunohistochemical and molecular biological evidence has indicated that topical calcipotriene exerts more pronounced inhibitory effects on epidermal proliferation than on dermal inflammation. It has been proposed that the bioavailability of calcipotriene in the dermal compartment may be markedly reduced compared to its availability in the epidermal compartment13; therefore it can be deduced that its penetration into the dermis is low in the thick skin of palms and its effect on eccrine sweat glands is negligible. Based on these factors, the clinical benefit of calcipotriene in TRPA could be ascribed directly to its antiproliferative and prodifferentiating effects on epidermal keratinocytes. We believe the primary pathology of TRPA lies in the epidermis and that changes in eccrine ducts and glands are secondary to the epidermal changes.

It is difficult to conduct large-scale studies of TRPA due to its rare presentation. Based on our encouraging preliminary observations in 3 patients, we recommend further therapeutic trials of topical calcipotriene in the treatment of TRPA.

1. Erkek E. Unilateral transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma in a child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:564-566.

2. English JC 3rd, McCollough ML. Transient reactive papulotranslucent acrokeratoderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:686-687.