User login

Bronchiolitis and Discharge Criteria

Although bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalization for US infants,[1] there is a lack of basic prospective data about the expected inpatient clinical course and ongoing uncertainty about when a hospitalized child is ready for discharge to home.[2] This lack of data about children's readiness for discharge may result in variable hospital length‐of‐stay (LOS).[3, 4, 5]

One specific source of variability in discharge readiness and LOS variability may be the lack of consensus about safe threshold oxygen saturation values for discharge in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis.[6, 7] In 2006, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network recommended a discharge room air oxygen (RAO2) saturation threshold of 95%.[8] The same year, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) bronchiolitis clinical practice guideline stated that oxygen is not needed for children with RAO2 saturations 90% who are feeding well and have minimal respiratory distress.[9] There is a need for prospective studies to help clinicians make evidenced‐based discharge decisions for this common condition.

We performed a prospective, multicenter, multiyear study[10, 11, 12] to examine the typical inpatient clinical course of and to develop hospital discharge guidelines for children age <2 years hospitalized with bronchiolitis. We hypothesized that children would not worsen clinically and would be safe to discharge home once their respiratory status improved and they were able to remain hydrated.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a prospective, multicenter cohort study for 3 consecutive years during the 2007 to 2010 winter seasons, as part of the Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC), a program of the Emergency Medicine Network (

All patients were treated at the discretion of the treating physician. Inclusion criteria were an attending physician's diagnosis of bronchiolitis, age <2 years, and the ability of the parent/guardian to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria were previous enrollment and transfer to a participating hospital >48 hours after the original admission time. Therefore, children with comorbid conditions were included in this study. All consent and data forms were translated into Spanish. The institutional review board at each of the 16 participating hospitals approved the study.

Of the 2207 enrolled children, we excluded 109 (5%) children with a hospital LOS <1 day due to inadequate time to capture the required data for the present analysis. Among the 2098 remaining children, 1916 (91%) had daily inpatient data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. Thus, the analytic cohort was comprised of 1916 children hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

Data Collection

Investigators conducted detailed structured interviews. Chart reviews were conducted to obtain preadmission and daily hospital clinical data including respiratory rates, daily respiratory rate trends, degree of retractions, oxygen saturation, daily oxygen saturation trends, medical management, and disposition. These data were manually reviewed, and site investigators were queried about missing data and discrepancies. A follow‐up telephone interview was conducted with families 1 week after discharge to examine relapse events at both 24 hours and 7 days.

We used the question: How long ago did the following symptoms [eg, difficulty breathing] begin [for the] current illness? to estimate the onset of the current illness. Pulse was categorized as low, normal, or high based on age‐related heart rate values.[13] Presence of apnea was recorded daily by site investigators.[14]

Nasopharyngeal Aspirate Collection and Virology Testing

As described previously, site teams used a standardized protocol to collect nasopharyngeal aspirates,[11] which were tested for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B; rhinovirus (RV); parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3; influenza virus types A and B; 2009 novel H1N1; human metapneumovirus; coronaviruses NL‐63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E; enterovirus, and adenovirus using polymerase chain reaction.[11, 15, 16, 17]

Defining Clinical Improvement and Worsening

Clinical improvement criteria were based on the 2006 AAP guidelines.[9] For respiratory rate and oxygen saturation, clinicians estimated average daily respiratory rate and oxygen saturation based on the recorded readings from the previous 24 hours. This estimation reflects the process clinicians use when rounding on their hospitalized patients, and thus may be more similar to standard clinical practice than a calculated mean. The respiratory rate criteria are adjusted for age.[18, 19] For daily estimated average oxygen saturation we used the AAP criteria of RAO2 saturation of 90%. Considering that oxygen saturation is the main determinant of LOS,[20] healthy infants age <6 months may have transient oxygen saturations of around 80%,[21] and that errors in estimation may occur, we included a lowest RAO2 of 88% in our improvement criteria. By combining the dichotomized estimated oxygen saturation (90% or not) with the lower limit of 88%, there was little room for erroneous conclusions. A child was considered clinically improved on the earliest date he/she met all of the following criteria: (1) none or mild retractions and improved or stable retractions compared with the previous inpatient day; (2) daily estimated average respiratory rate (RR) <60 breaths per minute for age <6 months, <55 breaths/minute for age 6 to 11 months, and <45 breaths/minute for age 12 months with a decreasing or stable trend over the course of the current day; (3) daily estimated average RAO2 saturation 90%, lowest RAO2 saturation 88%[21]; and (4) not receiving intravenous (IV) fluids or for children receiving IV fluids a clinician report of the child maintaining oral hydration. Children who reached the clinical improvement criteria were considered clinically worse if they required intensive care or had the inverse of 1 of the improvement criteria: moderate/severe retractions that were worse compared with the previous inpatient day, daily average RR 60 with an increasing trend over the current day, need for oxygen, or need for IV fluids.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Data are presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), means with standard deviations, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). To examine potential factors associated with clinical worsening after reaching clinical improvement, we used 2, Fisher exact, Student t test, and Kruskall‐Wallis tests, as appropriate.

Adjusted analyses used generalized linear mixed models with a logit link to identify independent risk factors for worsening after reaching clinical improvement. Fixed effects for patient‐level factors and a random site effect were used. Factors were tested for inclusion in the multivariable model if they were found to be associated with worsening in unadjusted analyses (P<0.20) or were considered clinically important. Results are reported as odds ratios with 95% CIs.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to evaluate these improvement criteria: (1) we excluded the lowest RAO2 saturation requirement of 88%, (2) we examined a 94% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[22] (3) we examined a 95% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[8] and (4) we examined children age <12 months with no history of wheeze.

RESULTS

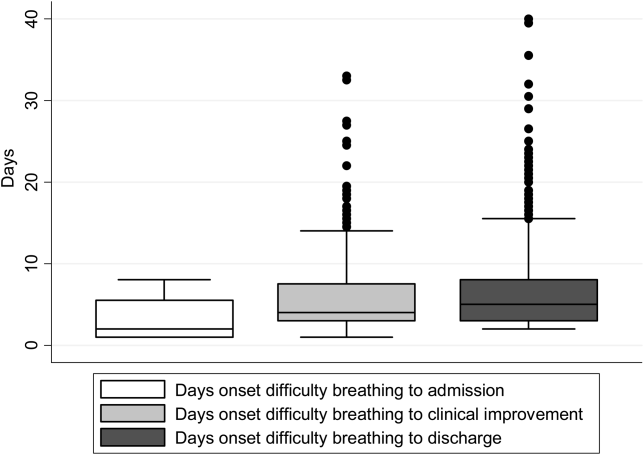

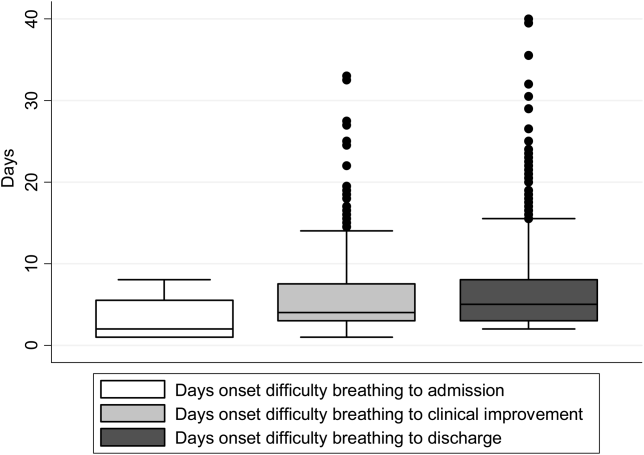

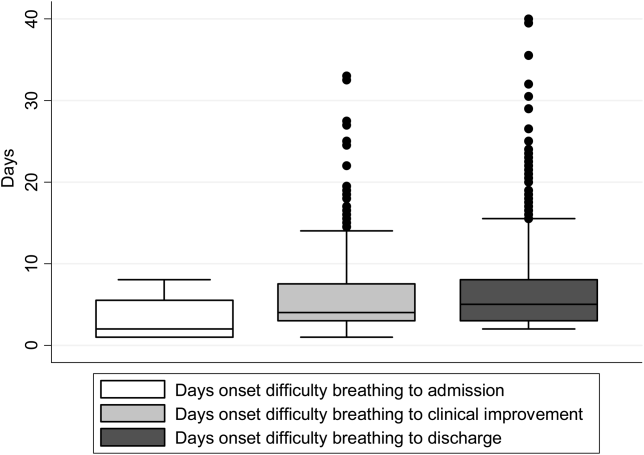

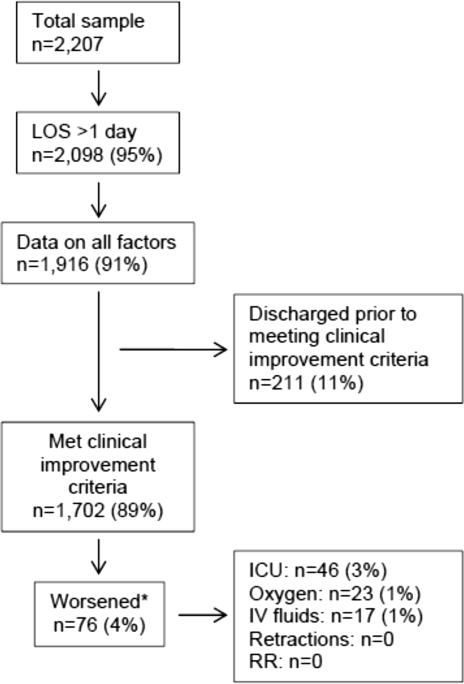

There were 1916 children hospitalized with bronchiolitis with data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. The median number of days from the beginning of difficulty breathing until admission was 2 days (IQR, 15.5 days; range, 18 days) and from the beginning of difficulty breathing until clinical improvement was 4 days (IQR, 37.5 days; range, 133 days) (Figure 1). The variance for days to admission was significantly less than the variance for days to clinical improvement (P<0.001).

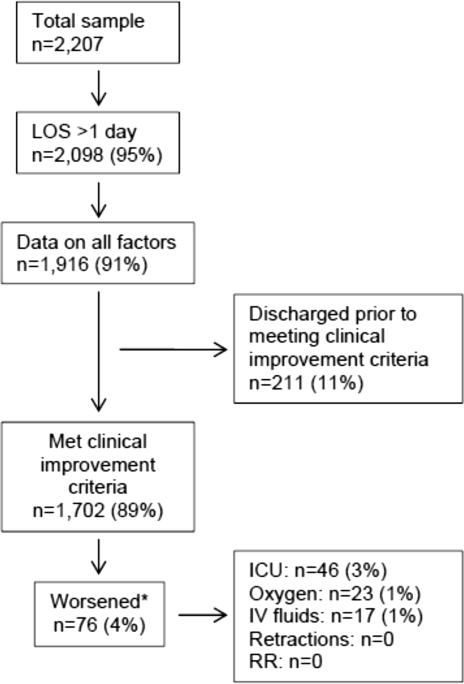

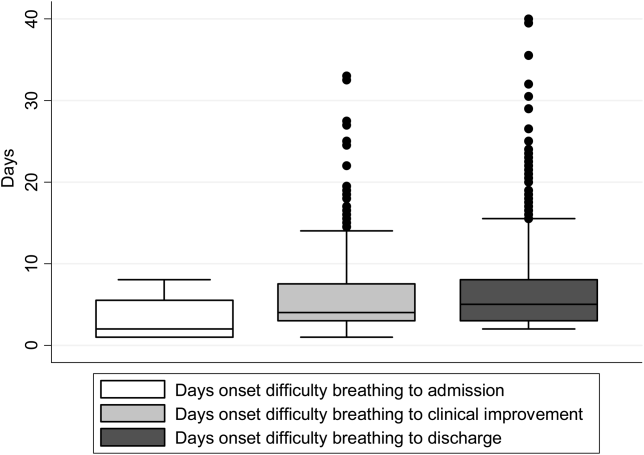

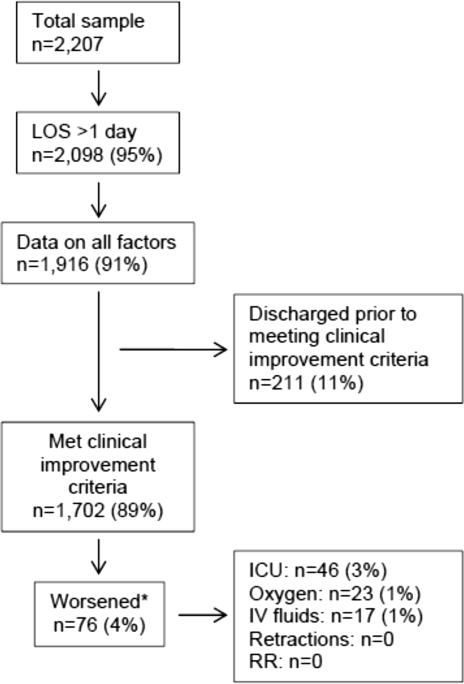

In this observational study, clinicians discharged 214 (11%) of the 1916 children before meeting the definition of clinical improvement. Thus, 1702 (89%; 95% CI: 87%‐90%) children reached the clinical improvement criteria, had a LOS >1 day, and had data on all factors (Figure 2).

Of the 1702 children who met the clinical improvement criteria, there were 76 children (4%; 95% CI: 3%5%) who worsened (Figure 2). The worsening occurred within a median of 1 day (IQR, 13 days) of clinical improvement. Forty‐six (3%) of the children required transfer to the ICU (1 required intubation, 1 required continuous positive airway pressure, and 4 had apnea), 23 (1%) required oxygen, and 17 (1%) required IV fluids. Eight percent of children met multiple criteria for worsening. A comparison between children who did and did not worsen is shown in Table 1. In general, children who worsened after improvement were younger and born earlier. These children also presented in more severe respiratory distress, had moderate or severe retractions, oxygen saturation <85% at hospitalization, inadequate oral intake, and apnea documented during the hospitalization. Neither viral etiology nor site of care influenced whether the children worsened after improving. However, stratified analysis of children based on initial location of admission (ie, ICU or ward) showed that among the children admitted to the ICU from the emergency department (ED), 89% met the improvement criteria and 19% clinically worsened. In contrast, among children admitted to the ward from the ED, 89% met the improvement criteria, and only 2% clinically worsened. Stratified multivariable models based on the initial location of admission from the ED (ie, ICU or ward) were not possible due to small sample sizes after stratification. None of these children had relapse events requiring rehospitalization within either 24 hours or 7 days of discharge.

| Did Not Worsen, n=1,626 | Worsened, n=76 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age <2 months, % | 29 | 57 | <0.001 |

| Month of birth, % | 0.02 | ||

| OctoberMarch | 61 | 75 | |

| AprilSeptember | 39 | 25 | |

| Sex, % | 0.51 | ||

| Male | 59 | 55 | |

| Female | 41 | 45 | |

| Race, % | 0.050 | ||

| White | 63 | 58 | |

| Black | 23 | 34 | |

| Other or missing | 14 | 8 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 37 | 22 | 0.01 |

| Insurance, % | 0.87 | ||

| Nonprivate | 68 | 67 | |

| Private | 32 | 33 | |

| Medical history | |||

| Gestational age <37 weeks, % | 23 | 39 | 0.002 |

| Birth weight, % | 0.52 | ||

| <5 lbs | 13 | 12 | |

| 5 lbs | 34 | 41 | |

| 7 lbs | 53 | 47 | |

| Mother's age, median (IQR) | 27 (2333) | 27 (2233) | 0.54 |

| Is or was breastfed, % | 61 | 51 | 0.10 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, % | 15 | 20 | 0.22 |

| Exposure to smoke, % | 13 | 20 | 0.11 |

| Family history of asthma, % | 0.89 | ||

| Neither parent | 68 | 64 | |

| Either mother or father | 27 | 30 | |

| Both parents | 4 | 4 | |

| Do not know/missing | 2 | 1 | |

| History of wheezing, % | 23 | 17 | 0.24 |

| History of eczema, % | 16 | 7 | 0.04 |

| History of intubation, % | 9 | 12 | 0.50 |

| Major, relevant, comorbid medical disorder, % | 20 | 24 | 0.46 |

| Current illness | |||

| When difficulty breathing began, preadmission, % | 0.63 | ||

| 1 day | 70 | 75 | |

| <1 day | 28 | 23 | |

| No difficulty preadmission | 2 | 3 | |

| Weight, lbs, median (IQR) | 12.3 (8.817.4) | 9.0 (6.613.2) | 0.001 |

| Temperature, F, median (IQR) | 99.5 (98.6100.6) | 99.4 (98.1100.4) | 0.06 |

| Pulse, beats per minute by age | 0.82 | ||

| Low | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Normal | 48 | 46 | |

| High | 51 | 54 | |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per minute, median (IQR) | 48 (4060) | 48 (3864) | 0.28 |

| Retractions, % | 0.001 | ||

| None | 22 | 25 | |

| Mild | 43 | 24 | |

| Moderate | 26 | 33 | |

| Severe | 4 | 12 | |

| Missing | 5 | 7 | |

| Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry or ABG, % | 0.001 | ||

| <85 | 4 | 12 | |

| 8587.9 | 3 | 4 | |

| 8889.9 | 5 | 0 | |

| 9093.9 | 18 | 11 | |

| 94 | 72 | 73 | |

| Oral intake, % | <0.001 | ||

| Adequate | 45 | 22 | |

| Inadequate | 42 | 63 | |

| Missing | 13 | 14 | |

| Presence of apnea, % | 7 | 24 | <0.001 |

| RSV‐A, % | 44 | 41 | 0.54 |

| RSV‐B, % | 30 | 25 | 0.36 |

| HRV, % | 24 | 24 | 0.88 |

| Chest x‐ray results during ED/preadmission visit | |||

| Atelectasis | 12 | 13 | 0.77 |

| Infiltrate | 13 | 11 | 0.50 |

| Hyperinflated | 18 | 21 | 0.47 |

| Peribronchial cuffing/thickening | 23 | 17 | 0.32 |

| Normal | 14 | 16 | 0.75 |

| White blood count, median (IQR) | 11.2 (8.714.4) | 11.9 (9.214.4) | 0.60 |

| Platelet count, median (IQR) | 395 (317490) | 430 (299537) | 0.56 |

| Sodium, median (IQR) | 138 (136140) | 137 (135138) | 0.19 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (14) | 4.5 (28) | <0.001 |

| One‐week follow‐up | |||

| Relapse within 24 hours of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 0.5 | 0 | 0.56 |

| Relapse within 7 days of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 1 | 0 | 0.35 |

On multivariable analysis (Table 2), independent risk factors for worsening after reaching the clinical improvement criteria were young age, preterm birth, and presenting to care with more severe bronchiolitis represented by severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea. To further evaluate the improvement criteria in the current analysis, multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted. The frequency of clinical worsening after reaching the improvement criteria was stable when we examined different RA02 criteria in sensitivity analyses: (1) excluding RA02 as a criterion for improvement: 90% met improvement criteria and 4% experienced clinical worsening, (2) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 94%: 62% met improvement criteria and 6% experienced clinical worsening, and (3) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 95%: 47% met improvement criteria and 5% experienced clinical worsening. Furthermore, stratifying by age <2 months and restricting to more stringent definitions of bronchiolitis (ie, age <1 year or age <1 year+no history of wheezing) also did not materially change the results (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article).

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age <2 months | 3.51 | 2.07‐5.94 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age <37 weeks | 1.94 | 1.13‐3.32 | 0.02 |

| Retractions | |||

| None | 1.30 | 0.80‐3.23 | 0.19 |

| Mild | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Moderate | 1.91 | 0.99‐3.71 | 0.06 |

| Severe | 5.55 | 2.1214.50 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 1.70 | 0.53‐5.42 | 0.37 |

| Oral intake | |||

| Adequate | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Inadequate | 2.54 | 1.39‐4.62 | 0.002 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.88 | 0.79‐4.44 | 0.15 |

| Presence of apnea | 2.87 | 1.45‐5.68 | 0.003 |

We compared the 214 children who were discharged prior to reaching clinical improvement with the 1702 children who reached the clinical improvement criteria. The 214 children were less likely to be age <2 months (22% vs 30%; P=0.02). These 2 groups (214 vs 1702) were similar with respect to severe retractions (2% vs 4%; P=0.13), median respiratory rate (48 vs 48; P=0.42), oxygen saturation <90% (15% vs 11%; P=0.07), inadequate oral intake (50% vs 43%; P=0.13), and rates of relapse events requiring rehospitalization within both 24 hours (0.6% vs 0.6%; P=0.88) and 7 days (1% vs 1%; P=0.90) of discharge.

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter, multiyear study of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, we found that children present to a hospital in a relatively narrow time frame, but their time to recovery in the hospital is highly variable. Nonetheless, 96% of children continued to improve once they had: (1) improving or stable retractions rated as none/mild, (2) a decreasing or stable RR by age, (3) estimated average RAO2 saturation 90% and lowest RAO2 saturation of 88%, and (4) were hydrated. The 4% of children who worsened after clinically improving were more likely to be age <2 months, born <37 weeks, and present with more severe distress (ie, severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea). Based on the low risk of worsening after clinical improvement, especially among children admitted to the regular ward (2%), we believe these 4 clinical criteria could be used as discharge criteria for this common pediatric illness with a predominantly monophasic clinical course.

Variability in hospital LOS for children with bronchiolitis exists in the United States[3] and internationally.[4, 5] Cheung and colleagues analyzed administrative data from over 75,000 children admitted for bronchiolitis in England between April 2007 and March 2010 and found sixfold variation in LOS between sites. They concluded that this LOS variability was due in part to providers' clinical decision making.[5] Srivastava and colleagues[23] addressed variable clinician decision making in bronchiolitis and 10 other common pediatric conditions by embedding discharge criteria developed by expert consensus into admission order sets. They found that for children with bronchiolitis, the embedded discharge criteria reduced the median LOS from 1.91 to 1.87 days. In contrast to the single‐center data presented by White and colleagues,[24] the prospective, multicenter MARC‐30 data provide a clear understanding of the normal clinical course for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, determine if children clinically worsen after clinical improvement, and provide data about discharge criteria for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Although there is a lack of rigorous published data, the lower tract symptoms of bronchiolitis (eg, cough, retractions) are said to peak on days 5 to 7 of illness and then gradually resolve.[25] In the present study, we found that the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until hospital admission is less variable than the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until either clinical improvement or discharge. Although 75% of children have clinically improved within 7.5 days of difficulty breathing based on the IQR results, the remaining 25% may have a more prolonged recovery in the hospital of up to 3 weeks. Interestingly, prolonged recovery times from bronchiolitis have also been noted in children presenting to the ED[26] and in an outpatient population.[27] It is unclear why 20% to 25% of children at different levels of severity of illness have prolonged recovery from bronchiolitis, but this group of children requires further investigation.

Given the variability of recovery times, clinicians may have difficulty knowing when a child is ready for hospital discharge. One of the main stumbling blocks for discharge readiness in children with bronchiolitis is the interpretation of the oxygen saturation value.[6, 8, 9, 20, 28] However, it should be considered that interpreting the oxygen saturation in a child who is clinically improving in the hospital setting is different than interpreting the oxygen saturation of a child in the ED or the clinic whose clinical course is less certain.[22] In the hospital setting, using the oxygen saturation value in in the AAP guideline,[9] 4% of children clinically worsened after they met the improvement criteria, a clinical pattern observed previously with supplemental oxygen.[28] This unpredictability may explain some of the variation in providers' clinical decision making.[5] The children who worsened, and therefore deserve more cautious discharge planning, were young (<2 months), premature (<37 weeks gestational age), and presented in more severe distress. Those children admitted to the ICU from the ED worsened more commonly than children admitted to the ward (19% vs 2%). Interestingly, the viral etiology of the child's bronchiolitis did not influence whether a child worsened after reaching the improvement criteria. Therefore, although children with RV bronchiolitis have a shorter hospital LOS than children with RSV bronchiolitis,[11] the pattern of recovery did not differ by viral etiology.

In addition to unsafe discharges, clinicians may be concerned about the possibility of readmissions. Although somewhat controversial, hospital readmission is being used as a quality of care metric.[29, 30, 31] One response to minimize readmissions would be for clinicians to observe children for longer than clinically indicated.[32] However, shorter LOS is not necessarily associated with increased readmission rates.[33] Given that the geometric mean of hospital charges per child with bronchiolitis increased from $6380 in 2000 to $8530 in 2009,[34] the potential for safely reducing hospital LOS by using the discharge criteria proposed in the current study instead of other criteria[8] may net substantial cost savings. Furthermore, reducing LOS would decrease the time children expose others to these respiratory viruses and possibly reduce medical errors.[35]

Our study has some potential limitations. Because the study participants were all hospitalized, these data do not inform admission or discharge decisions from either the ED or the clinic; but other data address those clinical scenarios.[22] Also, the 16 sites that participated in this study were large, urban teaching hospitals. Consequently, these results are not necessarily generalizable to smaller community hospitals. Although numerous data points were required to enter the analytic cohort, only 9% of the sample was excluded for missing data. There were 214 children who did not meet our improvement criteria by the time of discharge. Although the inability to include these children in the analysis may be seen as a limitation, this practice variability underscores the need for more data about discharging hospitalized children with bronchiolitis. Last, site teams reviewed medical records daily. More frequent recording of the clinical course would have yielded more granular data, but the current methodology replicates how data are generally presented during patient care rounds, when decisions about suitability for discharge are often considered.

CONCLUSION

We documented in this large multicenter study that most children hospitalized with bronchiolitis had a wide range of time to recovery, but the vast majority continued to improve once they reached the identified clinical criteria that predict a safe discharge to home. The children who worsened after clinical improvement were more likely to be younger, premature infants presenting in more severe distress. Although additional prospective validation of these hospital discharge criteria is warranted, these data may help clinicians make more evidence‐based discharge decisions for a common pediatric illness with high practice variation, both in the United States[3] and in other countries.[4, 5]

Acknowledgements

Collaborators in the MARC‐30 Study: Besh Barcega, MD, Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA; John Cheng, MD, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, GA; Dorothy Damore, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital‐Cornell, New York, NY; Carlos Delgado, MD, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, GA; Haitham Haddad, MD, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, Cleveland, OH; Paul Hain, MD, Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; Frank LoVecchio, DO, Maricopa Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ; Charles Macias, MD MPH, Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX; Jonathan Mansbach, MD, MPH, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA; Eugene Mowad, MD, Akron Children's Hospital, Akron, OH; Brian Pate, MD, Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO; Mark Riederer, MD, Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; M. Jason Sanders, MD, Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX; Alan R. Schroeder, MD, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA; Nikhil Shah, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital‐Cornell, New York, NY; Michelle Stevenson, MD, MS, Kosair Children's Hospital, Louisville, KY; Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, CA; Stephen Teach, MD, MPH, Children's National Medical Center, Washington, DC; Lisa Zaoutis, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants U01 AI‐67693 and K23 AI‐77801 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Drs. Mansbach and Piedra have provided consultation to Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Otherwise, no authors report any potential conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

- , , , , . Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):244–252.

- . “A hospital is no place to be sick” Samuel Goldwyn (1882–1974). Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(8):565–566.

- , , , , , Variation in inpatient diagnostic testing and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):878–884.

- , , , International variation in the management of infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus. International RSV Study Group. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(3):215–220.

- , , , , . Population variation in admission rates and duration of inpatient stay for bronchiolitis in England. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(1):57–59.

- , , , . Impact of pulse oximetry and oxygen therapy on length of stay in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(6):527–530.

- , , . Pulse oximetry in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):740–752.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Bronchiolitis in children (SIGN 91). In: NHS Quality Improvement Scotland. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; 2006.

- , , , et al. Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1774–1793.

- , , , et al. Prospective multicenter study of children with bronchiolitis requiring mechanical ventilation. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e492–e500.

- , , , et al. Prospective multicenter study of viral etiology and hospital length of stay in children with severe bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):700–706.

- , , , et al. Apnea in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1194–e1201.

- . Evaluation of the cardiovascular system: history and physical evaluation. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW III, Schor NF, Behrman RF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:1529–1536.

- , , , et al. Apnea in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1194–e1201.

- , , , et al. Respiratory viral infections in patients with chronic, obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect. 2005;50(4):322–330.

- , , , . Evaluation of real‐time PCR for diagnosis of Bordetella pertussis infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:62.

- , , , , . Evaluation of three real‐time PCR assays for detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in an outbreak investigation. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(9):3116–3118.

- , , , et al. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: a systematic review of observational studies. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1011–1018.

- , , , , , . Development of heart and respiratory rate percentile curves for hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1150–e1157.

- , . Effect of oxygen supplementation on length of stay for infants hospitalized with acute viral bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):470–475.

- , , , et al. Longitudinal assessment of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in healthy infants during the first 6 months of age. Collaborative Home Infant Monitoring Evaluation (CHIME) Study Group. J Pediatr. 1999;135(5):580–586.

- , , , et al. Prospective multicenter study of bronchiolitis: predicting safe discharges from the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):680–688.

- , , , et al. Delays in discharge in a tertiary care pediatric hospital. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):481–485.

- , , , et al. Using quality improvement to optimise paediatric discharge efficiency. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):428–436.

- , . Bronchiolitis in infants and children: treatment; outcome; and prevention. In: Torchia M, ed. UpToDate. Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands; Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013.

- , . Duration of illness in infants with bronchiolitis evaluated in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):285–290.

- , , . Duration of illness in ambulatory children diagnosed with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(10):997–1000.

- , , , et al. A clinical pathway for bronchiolitis is effective in reducing readmission rates. J Pediatr. 2005;147(5):622–626.

- , , , et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429–436.

- , , , et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380.

- , , , , , . Preventability of early readmissions at a children's hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171–e181.

- , . Hospital readmission: quality indicator or statistical inevitability? Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):569–570.

- , , , et al. Children's hospitals with shorter lengths of stay do not have higher readmission rates. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1034–1038.e1.

- , , , , . Trends in bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States, 2000–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):28–36.

- , , , . Preventable adverse events in infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):603–608.

Although bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalization for US infants,[1] there is a lack of basic prospective data about the expected inpatient clinical course and ongoing uncertainty about when a hospitalized child is ready for discharge to home.[2] This lack of data about children's readiness for discharge may result in variable hospital length‐of‐stay (LOS).[3, 4, 5]

One specific source of variability in discharge readiness and LOS variability may be the lack of consensus about safe threshold oxygen saturation values for discharge in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis.[6, 7] In 2006, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network recommended a discharge room air oxygen (RAO2) saturation threshold of 95%.[8] The same year, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) bronchiolitis clinical practice guideline stated that oxygen is not needed for children with RAO2 saturations 90% who are feeding well and have minimal respiratory distress.[9] There is a need for prospective studies to help clinicians make evidenced‐based discharge decisions for this common condition.

We performed a prospective, multicenter, multiyear study[10, 11, 12] to examine the typical inpatient clinical course of and to develop hospital discharge guidelines for children age <2 years hospitalized with bronchiolitis. We hypothesized that children would not worsen clinically and would be safe to discharge home once their respiratory status improved and they were able to remain hydrated.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a prospective, multicenter cohort study for 3 consecutive years during the 2007 to 2010 winter seasons, as part of the Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC), a program of the Emergency Medicine Network (

All patients were treated at the discretion of the treating physician. Inclusion criteria were an attending physician's diagnosis of bronchiolitis, age <2 years, and the ability of the parent/guardian to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria were previous enrollment and transfer to a participating hospital >48 hours after the original admission time. Therefore, children with comorbid conditions were included in this study. All consent and data forms were translated into Spanish. The institutional review board at each of the 16 participating hospitals approved the study.

Of the 2207 enrolled children, we excluded 109 (5%) children with a hospital LOS <1 day due to inadequate time to capture the required data for the present analysis. Among the 2098 remaining children, 1916 (91%) had daily inpatient data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. Thus, the analytic cohort was comprised of 1916 children hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

Data Collection

Investigators conducted detailed structured interviews. Chart reviews were conducted to obtain preadmission and daily hospital clinical data including respiratory rates, daily respiratory rate trends, degree of retractions, oxygen saturation, daily oxygen saturation trends, medical management, and disposition. These data were manually reviewed, and site investigators were queried about missing data and discrepancies. A follow‐up telephone interview was conducted with families 1 week after discharge to examine relapse events at both 24 hours and 7 days.

We used the question: How long ago did the following symptoms [eg, difficulty breathing] begin [for the] current illness? to estimate the onset of the current illness. Pulse was categorized as low, normal, or high based on age‐related heart rate values.[13] Presence of apnea was recorded daily by site investigators.[14]

Nasopharyngeal Aspirate Collection and Virology Testing

As described previously, site teams used a standardized protocol to collect nasopharyngeal aspirates,[11] which were tested for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B; rhinovirus (RV); parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3; influenza virus types A and B; 2009 novel H1N1; human metapneumovirus; coronaviruses NL‐63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E; enterovirus, and adenovirus using polymerase chain reaction.[11, 15, 16, 17]

Defining Clinical Improvement and Worsening

Clinical improvement criteria were based on the 2006 AAP guidelines.[9] For respiratory rate and oxygen saturation, clinicians estimated average daily respiratory rate and oxygen saturation based on the recorded readings from the previous 24 hours. This estimation reflects the process clinicians use when rounding on their hospitalized patients, and thus may be more similar to standard clinical practice than a calculated mean. The respiratory rate criteria are adjusted for age.[18, 19] For daily estimated average oxygen saturation we used the AAP criteria of RAO2 saturation of 90%. Considering that oxygen saturation is the main determinant of LOS,[20] healthy infants age <6 months may have transient oxygen saturations of around 80%,[21] and that errors in estimation may occur, we included a lowest RAO2 of 88% in our improvement criteria. By combining the dichotomized estimated oxygen saturation (90% or not) with the lower limit of 88%, there was little room for erroneous conclusions. A child was considered clinically improved on the earliest date he/she met all of the following criteria: (1) none or mild retractions and improved or stable retractions compared with the previous inpatient day; (2) daily estimated average respiratory rate (RR) <60 breaths per minute for age <6 months, <55 breaths/minute for age 6 to 11 months, and <45 breaths/minute for age 12 months with a decreasing or stable trend over the course of the current day; (3) daily estimated average RAO2 saturation 90%, lowest RAO2 saturation 88%[21]; and (4) not receiving intravenous (IV) fluids or for children receiving IV fluids a clinician report of the child maintaining oral hydration. Children who reached the clinical improvement criteria were considered clinically worse if they required intensive care or had the inverse of 1 of the improvement criteria: moderate/severe retractions that were worse compared with the previous inpatient day, daily average RR 60 with an increasing trend over the current day, need for oxygen, or need for IV fluids.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Data are presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), means with standard deviations, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). To examine potential factors associated with clinical worsening after reaching clinical improvement, we used 2, Fisher exact, Student t test, and Kruskall‐Wallis tests, as appropriate.

Adjusted analyses used generalized linear mixed models with a logit link to identify independent risk factors for worsening after reaching clinical improvement. Fixed effects for patient‐level factors and a random site effect were used. Factors were tested for inclusion in the multivariable model if they were found to be associated with worsening in unadjusted analyses (P<0.20) or were considered clinically important. Results are reported as odds ratios with 95% CIs.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to evaluate these improvement criteria: (1) we excluded the lowest RAO2 saturation requirement of 88%, (2) we examined a 94% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[22] (3) we examined a 95% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[8] and (4) we examined children age <12 months with no history of wheeze.

RESULTS

There were 1916 children hospitalized with bronchiolitis with data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. The median number of days from the beginning of difficulty breathing until admission was 2 days (IQR, 15.5 days; range, 18 days) and from the beginning of difficulty breathing until clinical improvement was 4 days (IQR, 37.5 days; range, 133 days) (Figure 1). The variance for days to admission was significantly less than the variance for days to clinical improvement (P<0.001).

In this observational study, clinicians discharged 214 (11%) of the 1916 children before meeting the definition of clinical improvement. Thus, 1702 (89%; 95% CI: 87%‐90%) children reached the clinical improvement criteria, had a LOS >1 day, and had data on all factors (Figure 2).

Of the 1702 children who met the clinical improvement criteria, there were 76 children (4%; 95% CI: 3%5%) who worsened (Figure 2). The worsening occurred within a median of 1 day (IQR, 13 days) of clinical improvement. Forty‐six (3%) of the children required transfer to the ICU (1 required intubation, 1 required continuous positive airway pressure, and 4 had apnea), 23 (1%) required oxygen, and 17 (1%) required IV fluids. Eight percent of children met multiple criteria for worsening. A comparison between children who did and did not worsen is shown in Table 1. In general, children who worsened after improvement were younger and born earlier. These children also presented in more severe respiratory distress, had moderate or severe retractions, oxygen saturation <85% at hospitalization, inadequate oral intake, and apnea documented during the hospitalization. Neither viral etiology nor site of care influenced whether the children worsened after improving. However, stratified analysis of children based on initial location of admission (ie, ICU or ward) showed that among the children admitted to the ICU from the emergency department (ED), 89% met the improvement criteria and 19% clinically worsened. In contrast, among children admitted to the ward from the ED, 89% met the improvement criteria, and only 2% clinically worsened. Stratified multivariable models based on the initial location of admission from the ED (ie, ICU or ward) were not possible due to small sample sizes after stratification. None of these children had relapse events requiring rehospitalization within either 24 hours or 7 days of discharge.

| Did Not Worsen, n=1,626 | Worsened, n=76 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age <2 months, % | 29 | 57 | <0.001 |

| Month of birth, % | 0.02 | ||

| OctoberMarch | 61 | 75 | |

| AprilSeptember | 39 | 25 | |

| Sex, % | 0.51 | ||

| Male | 59 | 55 | |

| Female | 41 | 45 | |

| Race, % | 0.050 | ||

| White | 63 | 58 | |

| Black | 23 | 34 | |

| Other or missing | 14 | 8 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 37 | 22 | 0.01 |

| Insurance, % | 0.87 | ||

| Nonprivate | 68 | 67 | |

| Private | 32 | 33 | |

| Medical history | |||

| Gestational age <37 weeks, % | 23 | 39 | 0.002 |

| Birth weight, % | 0.52 | ||

| <5 lbs | 13 | 12 | |

| 5 lbs | 34 | 41 | |

| 7 lbs | 53 | 47 | |

| Mother's age, median (IQR) | 27 (2333) | 27 (2233) | 0.54 |

| Is or was breastfed, % | 61 | 51 | 0.10 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, % | 15 | 20 | 0.22 |

| Exposure to smoke, % | 13 | 20 | 0.11 |

| Family history of asthma, % | 0.89 | ||

| Neither parent | 68 | 64 | |

| Either mother or father | 27 | 30 | |

| Both parents | 4 | 4 | |

| Do not know/missing | 2 | 1 | |

| History of wheezing, % | 23 | 17 | 0.24 |

| History of eczema, % | 16 | 7 | 0.04 |

| History of intubation, % | 9 | 12 | 0.50 |

| Major, relevant, comorbid medical disorder, % | 20 | 24 | 0.46 |

| Current illness | |||

| When difficulty breathing began, preadmission, % | 0.63 | ||

| 1 day | 70 | 75 | |

| <1 day | 28 | 23 | |

| No difficulty preadmission | 2 | 3 | |

| Weight, lbs, median (IQR) | 12.3 (8.817.4) | 9.0 (6.613.2) | 0.001 |

| Temperature, F, median (IQR) | 99.5 (98.6100.6) | 99.4 (98.1100.4) | 0.06 |

| Pulse, beats per minute by age | 0.82 | ||

| Low | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Normal | 48 | 46 | |

| High | 51 | 54 | |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per minute, median (IQR) | 48 (4060) | 48 (3864) | 0.28 |

| Retractions, % | 0.001 | ||

| None | 22 | 25 | |

| Mild | 43 | 24 | |

| Moderate | 26 | 33 | |

| Severe | 4 | 12 | |

| Missing | 5 | 7 | |

| Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry or ABG, % | 0.001 | ||

| <85 | 4 | 12 | |

| 8587.9 | 3 | 4 | |

| 8889.9 | 5 | 0 | |

| 9093.9 | 18 | 11 | |

| 94 | 72 | 73 | |

| Oral intake, % | <0.001 | ||

| Adequate | 45 | 22 | |

| Inadequate | 42 | 63 | |

| Missing | 13 | 14 | |

| Presence of apnea, % | 7 | 24 | <0.001 |

| RSV‐A, % | 44 | 41 | 0.54 |

| RSV‐B, % | 30 | 25 | 0.36 |

| HRV, % | 24 | 24 | 0.88 |

| Chest x‐ray results during ED/preadmission visit | |||

| Atelectasis | 12 | 13 | 0.77 |

| Infiltrate | 13 | 11 | 0.50 |

| Hyperinflated | 18 | 21 | 0.47 |

| Peribronchial cuffing/thickening | 23 | 17 | 0.32 |

| Normal | 14 | 16 | 0.75 |

| White blood count, median (IQR) | 11.2 (8.714.4) | 11.9 (9.214.4) | 0.60 |

| Platelet count, median (IQR) | 395 (317490) | 430 (299537) | 0.56 |

| Sodium, median (IQR) | 138 (136140) | 137 (135138) | 0.19 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (14) | 4.5 (28) | <0.001 |

| One‐week follow‐up | |||

| Relapse within 24 hours of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 0.5 | 0 | 0.56 |

| Relapse within 7 days of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 1 | 0 | 0.35 |

On multivariable analysis (Table 2), independent risk factors for worsening after reaching the clinical improvement criteria were young age, preterm birth, and presenting to care with more severe bronchiolitis represented by severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea. To further evaluate the improvement criteria in the current analysis, multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted. The frequency of clinical worsening after reaching the improvement criteria was stable when we examined different RA02 criteria in sensitivity analyses: (1) excluding RA02 as a criterion for improvement: 90% met improvement criteria and 4% experienced clinical worsening, (2) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 94%: 62% met improvement criteria and 6% experienced clinical worsening, and (3) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 95%: 47% met improvement criteria and 5% experienced clinical worsening. Furthermore, stratifying by age <2 months and restricting to more stringent definitions of bronchiolitis (ie, age <1 year or age <1 year+no history of wheezing) also did not materially change the results (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article).

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age <2 months | 3.51 | 2.07‐5.94 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age <37 weeks | 1.94 | 1.13‐3.32 | 0.02 |

| Retractions | |||

| None | 1.30 | 0.80‐3.23 | 0.19 |

| Mild | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Moderate | 1.91 | 0.99‐3.71 | 0.06 |

| Severe | 5.55 | 2.1214.50 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 1.70 | 0.53‐5.42 | 0.37 |

| Oral intake | |||

| Adequate | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Inadequate | 2.54 | 1.39‐4.62 | 0.002 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.88 | 0.79‐4.44 | 0.15 |

| Presence of apnea | 2.87 | 1.45‐5.68 | 0.003 |

We compared the 214 children who were discharged prior to reaching clinical improvement with the 1702 children who reached the clinical improvement criteria. The 214 children were less likely to be age <2 months (22% vs 30%; P=0.02). These 2 groups (214 vs 1702) were similar with respect to severe retractions (2% vs 4%; P=0.13), median respiratory rate (48 vs 48; P=0.42), oxygen saturation <90% (15% vs 11%; P=0.07), inadequate oral intake (50% vs 43%; P=0.13), and rates of relapse events requiring rehospitalization within both 24 hours (0.6% vs 0.6%; P=0.88) and 7 days (1% vs 1%; P=0.90) of discharge.

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter, multiyear study of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, we found that children present to a hospital in a relatively narrow time frame, but their time to recovery in the hospital is highly variable. Nonetheless, 96% of children continued to improve once they had: (1) improving or stable retractions rated as none/mild, (2) a decreasing or stable RR by age, (3) estimated average RAO2 saturation 90% and lowest RAO2 saturation of 88%, and (4) were hydrated. The 4% of children who worsened after clinically improving were more likely to be age <2 months, born <37 weeks, and present with more severe distress (ie, severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea). Based on the low risk of worsening after clinical improvement, especially among children admitted to the regular ward (2%), we believe these 4 clinical criteria could be used as discharge criteria for this common pediatric illness with a predominantly monophasic clinical course.

Variability in hospital LOS for children with bronchiolitis exists in the United States[3] and internationally.[4, 5] Cheung and colleagues analyzed administrative data from over 75,000 children admitted for bronchiolitis in England between April 2007 and March 2010 and found sixfold variation in LOS between sites. They concluded that this LOS variability was due in part to providers' clinical decision making.[5] Srivastava and colleagues[23] addressed variable clinician decision making in bronchiolitis and 10 other common pediatric conditions by embedding discharge criteria developed by expert consensus into admission order sets. They found that for children with bronchiolitis, the embedded discharge criteria reduced the median LOS from 1.91 to 1.87 days. In contrast to the single‐center data presented by White and colleagues,[24] the prospective, multicenter MARC‐30 data provide a clear understanding of the normal clinical course for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, determine if children clinically worsen after clinical improvement, and provide data about discharge criteria for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Although there is a lack of rigorous published data, the lower tract symptoms of bronchiolitis (eg, cough, retractions) are said to peak on days 5 to 7 of illness and then gradually resolve.[25] In the present study, we found that the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until hospital admission is less variable than the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until either clinical improvement or discharge. Although 75% of children have clinically improved within 7.5 days of difficulty breathing based on the IQR results, the remaining 25% may have a more prolonged recovery in the hospital of up to 3 weeks. Interestingly, prolonged recovery times from bronchiolitis have also been noted in children presenting to the ED[26] and in an outpatient population.[27] It is unclear why 20% to 25% of children at different levels of severity of illness have prolonged recovery from bronchiolitis, but this group of children requires further investigation.

Given the variability of recovery times, clinicians may have difficulty knowing when a child is ready for hospital discharge. One of the main stumbling blocks for discharge readiness in children with bronchiolitis is the interpretation of the oxygen saturation value.[6, 8, 9, 20, 28] However, it should be considered that interpreting the oxygen saturation in a child who is clinically improving in the hospital setting is different than interpreting the oxygen saturation of a child in the ED or the clinic whose clinical course is less certain.[22] In the hospital setting, using the oxygen saturation value in in the AAP guideline,[9] 4% of children clinically worsened after they met the improvement criteria, a clinical pattern observed previously with supplemental oxygen.[28] This unpredictability may explain some of the variation in providers' clinical decision making.[5] The children who worsened, and therefore deserve more cautious discharge planning, were young (<2 months), premature (<37 weeks gestational age), and presented in more severe distress. Those children admitted to the ICU from the ED worsened more commonly than children admitted to the ward (19% vs 2%). Interestingly, the viral etiology of the child's bronchiolitis did not influence whether a child worsened after reaching the improvement criteria. Therefore, although children with RV bronchiolitis have a shorter hospital LOS than children with RSV bronchiolitis,[11] the pattern of recovery did not differ by viral etiology.

In addition to unsafe discharges, clinicians may be concerned about the possibility of readmissions. Although somewhat controversial, hospital readmission is being used as a quality of care metric.[29, 30, 31] One response to minimize readmissions would be for clinicians to observe children for longer than clinically indicated.[32] However, shorter LOS is not necessarily associated with increased readmission rates.[33] Given that the geometric mean of hospital charges per child with bronchiolitis increased from $6380 in 2000 to $8530 in 2009,[34] the potential for safely reducing hospital LOS by using the discharge criteria proposed in the current study instead of other criteria[8] may net substantial cost savings. Furthermore, reducing LOS would decrease the time children expose others to these respiratory viruses and possibly reduce medical errors.[35]

Our study has some potential limitations. Because the study participants were all hospitalized, these data do not inform admission or discharge decisions from either the ED or the clinic; but other data address those clinical scenarios.[22] Also, the 16 sites that participated in this study were large, urban teaching hospitals. Consequently, these results are not necessarily generalizable to smaller community hospitals. Although numerous data points were required to enter the analytic cohort, only 9% of the sample was excluded for missing data. There were 214 children who did not meet our improvement criteria by the time of discharge. Although the inability to include these children in the analysis may be seen as a limitation, this practice variability underscores the need for more data about discharging hospitalized children with bronchiolitis. Last, site teams reviewed medical records daily. More frequent recording of the clinical course would have yielded more granular data, but the current methodology replicates how data are generally presented during patient care rounds, when decisions about suitability for discharge are often considered.

CONCLUSION

We documented in this large multicenter study that most children hospitalized with bronchiolitis had a wide range of time to recovery, but the vast majority continued to improve once they reached the identified clinical criteria that predict a safe discharge to home. The children who worsened after clinical improvement were more likely to be younger, premature infants presenting in more severe distress. Although additional prospective validation of these hospital discharge criteria is warranted, these data may help clinicians make more evidence‐based discharge decisions for a common pediatric illness with high practice variation, both in the United States[3] and in other countries.[4, 5]

Acknowledgements

Collaborators in the MARC‐30 Study: Besh Barcega, MD, Loma Linda University Children's Hospital, Loma Linda, CA; John Cheng, MD, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, GA; Dorothy Damore, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital‐Cornell, New York, NY; Carlos Delgado, MD, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta at Egleston, Atlanta, GA; Haitham Haddad, MD, Rainbow Babies & Children's Hospital, Cleveland, OH; Paul Hain, MD, Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; Frank LoVecchio, DO, Maricopa Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ; Charles Macias, MD MPH, Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX; Jonathan Mansbach, MD, MPH, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA; Eugene Mowad, MD, Akron Children's Hospital, Akron, OH; Brian Pate, MD, Children's Mercy Hospital, Kansas City, MO; Mark Riederer, MD, Monroe Carell Jr. Children's Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN; M. Jason Sanders, MD, Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX; Alan R. Schroeder, MD, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, San Jose, CA; Nikhil Shah, MD, New York Presbyterian Hospital‐Cornell, New York, NY; Michelle Stevenson, MD, MS, Kosair Children's Hospital, Louisville, KY; Erin Stucky Fisher, MD, Rady Children's Hospital, San Diego, CA; Stephen Teach, MD, MPH, Children's National Medical Center, Washington, DC; Lisa Zaoutis, MD, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants U01 AI‐67693 and K23 AI‐77801 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. Drs. Mansbach and Piedra have provided consultation to Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. Otherwise, no authors report any potential conflicts of interest, including relevant financial interests, activities, relationships, and affiliations.

Although bronchiolitis is the leading cause of hospitalization for US infants,[1] there is a lack of basic prospective data about the expected inpatient clinical course and ongoing uncertainty about when a hospitalized child is ready for discharge to home.[2] This lack of data about children's readiness for discharge may result in variable hospital length‐of‐stay (LOS).[3, 4, 5]

One specific source of variability in discharge readiness and LOS variability may be the lack of consensus about safe threshold oxygen saturation values for discharge in children hospitalized with bronchiolitis.[6, 7] In 2006, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network recommended a discharge room air oxygen (RAO2) saturation threshold of 95%.[8] The same year, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) bronchiolitis clinical practice guideline stated that oxygen is not needed for children with RAO2 saturations 90% who are feeding well and have minimal respiratory distress.[9] There is a need for prospective studies to help clinicians make evidenced‐based discharge decisions for this common condition.

We performed a prospective, multicenter, multiyear study[10, 11, 12] to examine the typical inpatient clinical course of and to develop hospital discharge guidelines for children age <2 years hospitalized with bronchiolitis. We hypothesized that children would not worsen clinically and would be safe to discharge home once their respiratory status improved and they were able to remain hydrated.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

We conducted a prospective, multicenter cohort study for 3 consecutive years during the 2007 to 2010 winter seasons, as part of the Multicenter Airway Research Collaboration (MARC), a program of the Emergency Medicine Network (

All patients were treated at the discretion of the treating physician. Inclusion criteria were an attending physician's diagnosis of bronchiolitis, age <2 years, and the ability of the parent/guardian to give informed consent. The exclusion criteria were previous enrollment and transfer to a participating hospital >48 hours after the original admission time. Therefore, children with comorbid conditions were included in this study. All consent and data forms were translated into Spanish. The institutional review board at each of the 16 participating hospitals approved the study.

Of the 2207 enrolled children, we excluded 109 (5%) children with a hospital LOS <1 day due to inadequate time to capture the required data for the present analysis. Among the 2098 remaining children, 1916 (91%) had daily inpatient data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. Thus, the analytic cohort was comprised of 1916 children hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

Data Collection

Investigators conducted detailed structured interviews. Chart reviews were conducted to obtain preadmission and daily hospital clinical data including respiratory rates, daily respiratory rate trends, degree of retractions, oxygen saturation, daily oxygen saturation trends, medical management, and disposition. These data were manually reviewed, and site investigators were queried about missing data and discrepancies. A follow‐up telephone interview was conducted with families 1 week after discharge to examine relapse events at both 24 hours and 7 days.

We used the question: How long ago did the following symptoms [eg, difficulty breathing] begin [for the] current illness? to estimate the onset of the current illness. Pulse was categorized as low, normal, or high based on age‐related heart rate values.[13] Presence of apnea was recorded daily by site investigators.[14]

Nasopharyngeal Aspirate Collection and Virology Testing

As described previously, site teams used a standardized protocol to collect nasopharyngeal aspirates,[11] which were tested for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) types A and B; rhinovirus (RV); parainfluenza virus types 1, 2, and 3; influenza virus types A and B; 2009 novel H1N1; human metapneumovirus; coronaviruses NL‐63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E; enterovirus, and adenovirus using polymerase chain reaction.[11, 15, 16, 17]

Defining Clinical Improvement and Worsening

Clinical improvement criteria were based on the 2006 AAP guidelines.[9] For respiratory rate and oxygen saturation, clinicians estimated average daily respiratory rate and oxygen saturation based on the recorded readings from the previous 24 hours. This estimation reflects the process clinicians use when rounding on their hospitalized patients, and thus may be more similar to standard clinical practice than a calculated mean. The respiratory rate criteria are adjusted for age.[18, 19] For daily estimated average oxygen saturation we used the AAP criteria of RAO2 saturation of 90%. Considering that oxygen saturation is the main determinant of LOS,[20] healthy infants age <6 months may have transient oxygen saturations of around 80%,[21] and that errors in estimation may occur, we included a lowest RAO2 of 88% in our improvement criteria. By combining the dichotomized estimated oxygen saturation (90% or not) with the lower limit of 88%, there was little room for erroneous conclusions. A child was considered clinically improved on the earliest date he/she met all of the following criteria: (1) none or mild retractions and improved or stable retractions compared with the previous inpatient day; (2) daily estimated average respiratory rate (RR) <60 breaths per minute for age <6 months, <55 breaths/minute for age 6 to 11 months, and <45 breaths/minute for age 12 months with a decreasing or stable trend over the course of the current day; (3) daily estimated average RAO2 saturation 90%, lowest RAO2 saturation 88%[21]; and (4) not receiving intravenous (IV) fluids or for children receiving IV fluids a clinician report of the child maintaining oral hydration. Children who reached the clinical improvement criteria were considered clinically worse if they required intensive care or had the inverse of 1 of the improvement criteria: moderate/severe retractions that were worse compared with the previous inpatient day, daily average RR 60 with an increasing trend over the current day, need for oxygen, or need for IV fluids.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Data are presented as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), means with standard deviations, and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). To examine potential factors associated with clinical worsening after reaching clinical improvement, we used 2, Fisher exact, Student t test, and Kruskall‐Wallis tests, as appropriate.

Adjusted analyses used generalized linear mixed models with a logit link to identify independent risk factors for worsening after reaching clinical improvement. Fixed effects for patient‐level factors and a random site effect were used. Factors were tested for inclusion in the multivariable model if they were found to be associated with worsening in unadjusted analyses (P<0.20) or were considered clinically important. Results are reported as odds ratios with 95% CIs.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to evaluate these improvement criteria: (1) we excluded the lowest RAO2 saturation requirement of 88%, (2) we examined a 94% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[22] (3) we examined a 95% daily estimated average RAO2 saturation threshold,[8] and (4) we examined children age <12 months with no history of wheeze.

RESULTS

There were 1916 children hospitalized with bronchiolitis with data on all factors used to define clinical improvement and clinical worsening. The median number of days from the beginning of difficulty breathing until admission was 2 days (IQR, 15.5 days; range, 18 days) and from the beginning of difficulty breathing until clinical improvement was 4 days (IQR, 37.5 days; range, 133 days) (Figure 1). The variance for days to admission was significantly less than the variance for days to clinical improvement (P<0.001).

In this observational study, clinicians discharged 214 (11%) of the 1916 children before meeting the definition of clinical improvement. Thus, 1702 (89%; 95% CI: 87%‐90%) children reached the clinical improvement criteria, had a LOS >1 day, and had data on all factors (Figure 2).

Of the 1702 children who met the clinical improvement criteria, there were 76 children (4%; 95% CI: 3%5%) who worsened (Figure 2). The worsening occurred within a median of 1 day (IQR, 13 days) of clinical improvement. Forty‐six (3%) of the children required transfer to the ICU (1 required intubation, 1 required continuous positive airway pressure, and 4 had apnea), 23 (1%) required oxygen, and 17 (1%) required IV fluids. Eight percent of children met multiple criteria for worsening. A comparison between children who did and did not worsen is shown in Table 1. In general, children who worsened after improvement were younger and born earlier. These children also presented in more severe respiratory distress, had moderate or severe retractions, oxygen saturation <85% at hospitalization, inadequate oral intake, and apnea documented during the hospitalization. Neither viral etiology nor site of care influenced whether the children worsened after improving. However, stratified analysis of children based on initial location of admission (ie, ICU or ward) showed that among the children admitted to the ICU from the emergency department (ED), 89% met the improvement criteria and 19% clinically worsened. In contrast, among children admitted to the ward from the ED, 89% met the improvement criteria, and only 2% clinically worsened. Stratified multivariable models based on the initial location of admission from the ED (ie, ICU or ward) were not possible due to small sample sizes after stratification. None of these children had relapse events requiring rehospitalization within either 24 hours or 7 days of discharge.

| Did Not Worsen, n=1,626 | Worsened, n=76 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age <2 months, % | 29 | 57 | <0.001 |

| Month of birth, % | 0.02 | ||

| OctoberMarch | 61 | 75 | |

| AprilSeptember | 39 | 25 | |

| Sex, % | 0.51 | ||

| Male | 59 | 55 | |

| Female | 41 | 45 | |

| Race, % | 0.050 | ||

| White | 63 | 58 | |

| Black | 23 | 34 | |

| Other or missing | 14 | 8 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, % | 37 | 22 | 0.01 |

| Insurance, % | 0.87 | ||

| Nonprivate | 68 | 67 | |

| Private | 32 | 33 | |

| Medical history | |||

| Gestational age <37 weeks, % | 23 | 39 | 0.002 |

| Birth weight, % | 0.52 | ||

| <5 lbs | 13 | 12 | |

| 5 lbs | 34 | 41 | |

| 7 lbs | 53 | 47 | |

| Mother's age, median (IQR) | 27 (2333) | 27 (2233) | 0.54 |

| Is or was breastfed, % | 61 | 51 | 0.10 |

| Smoked during pregnancy, % | 15 | 20 | 0.22 |

| Exposure to smoke, % | 13 | 20 | 0.11 |

| Family history of asthma, % | 0.89 | ||

| Neither parent | 68 | 64 | |

| Either mother or father | 27 | 30 | |

| Both parents | 4 | 4 | |

| Do not know/missing | 2 | 1 | |

| History of wheezing, % | 23 | 17 | 0.24 |

| History of eczema, % | 16 | 7 | 0.04 |

| History of intubation, % | 9 | 12 | 0.50 |

| Major, relevant, comorbid medical disorder, % | 20 | 24 | 0.46 |

| Current illness | |||

| When difficulty breathing began, preadmission, % | 0.63 | ||

| 1 day | 70 | 75 | |

| <1 day | 28 | 23 | |

| No difficulty preadmission | 2 | 3 | |

| Weight, lbs, median (IQR) | 12.3 (8.817.4) | 9.0 (6.613.2) | 0.001 |

| Temperature, F, median (IQR) | 99.5 (98.6100.6) | 99.4 (98.1100.4) | 0.06 |

| Pulse, beats per minute by age | 0.82 | ||

| Low | 0.3 | 0 | |

| Normal | 48 | 46 | |

| High | 51 | 54 | |

| Respiratory rate, breaths per minute, median (IQR) | 48 (4060) | 48 (3864) | 0.28 |

| Retractions, % | 0.001 | ||

| None | 22 | 25 | |

| Mild | 43 | 24 | |

| Moderate | 26 | 33 | |

| Severe | 4 | 12 | |

| Missing | 5 | 7 | |

| Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry or ABG, % | 0.001 | ||

| <85 | 4 | 12 | |

| 8587.9 | 3 | 4 | |

| 8889.9 | 5 | 0 | |

| 9093.9 | 18 | 11 | |

| 94 | 72 | 73 | |

| Oral intake, % | <0.001 | ||

| Adequate | 45 | 22 | |

| Inadequate | 42 | 63 | |

| Missing | 13 | 14 | |

| Presence of apnea, % | 7 | 24 | <0.001 |

| RSV‐A, % | 44 | 41 | 0.54 |

| RSV‐B, % | 30 | 25 | 0.36 |

| HRV, % | 24 | 24 | 0.88 |

| Chest x‐ray results during ED/preadmission visit | |||

| Atelectasis | 12 | 13 | 0.77 |

| Infiltrate | 13 | 11 | 0.50 |

| Hyperinflated | 18 | 21 | 0.47 |

| Peribronchial cuffing/thickening | 23 | 17 | 0.32 |

| Normal | 14 | 16 | 0.75 |

| White blood count, median (IQR) | 11.2 (8.714.4) | 11.9 (9.214.4) | 0.60 |

| Platelet count, median (IQR) | 395 (317490) | 430 (299537) | 0.56 |

| Sodium, median (IQR) | 138 (136140) | 137 (135138) | 0.19 |

| Hospital length of stay, median (IQR) | 2 (14) | 4.5 (28) | <0.001 |

| One‐week follow‐up | |||

| Relapse within 24 hours of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 0.5 | 0 | 0.56 |

| Relapse within 7 days of hospital discharge requiring hospital admission, % | 1 | 0 | 0.35 |

On multivariable analysis (Table 2), independent risk factors for worsening after reaching the clinical improvement criteria were young age, preterm birth, and presenting to care with more severe bronchiolitis represented by severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea. To further evaluate the improvement criteria in the current analysis, multiple sensitivity analyses were conducted. The frequency of clinical worsening after reaching the improvement criteria was stable when we examined different RA02 criteria in sensitivity analyses: (1) excluding RA02 as a criterion for improvement: 90% met improvement criteria and 4% experienced clinical worsening, (2) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 94%: 62% met improvement criteria and 6% experienced clinical worsening, and (3) changing the average RA02 threshold for clinical improvement to 95%: 47% met improvement criteria and 5% experienced clinical worsening. Furthermore, stratifying by age <2 months and restricting to more stringent definitions of bronchiolitis (ie, age <1 year or age <1 year+no history of wheezing) also did not materially change the results (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article).

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age <2 months | 3.51 | 2.07‐5.94 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age <37 weeks | 1.94 | 1.13‐3.32 | 0.02 |

| Retractions | |||

| None | 1.30 | 0.80‐3.23 | 0.19 |

| Mild | 1.0 | Reference | |

| Moderate | 1.91 | 0.99‐3.71 | 0.06 |

| Severe | 5.55 | 2.1214.50 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 1.70 | 0.53‐5.42 | 0.37 |

| Oral intake | |||

| Adequate | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Inadequate | 2.54 | 1.39‐4.62 | 0.002 |

| Unknown/missing | 1.88 | 0.79‐4.44 | 0.15 |

| Presence of apnea | 2.87 | 1.45‐5.68 | 0.003 |

We compared the 214 children who were discharged prior to reaching clinical improvement with the 1702 children who reached the clinical improvement criteria. The 214 children were less likely to be age <2 months (22% vs 30%; P=0.02). These 2 groups (214 vs 1702) were similar with respect to severe retractions (2% vs 4%; P=0.13), median respiratory rate (48 vs 48; P=0.42), oxygen saturation <90% (15% vs 11%; P=0.07), inadequate oral intake (50% vs 43%; P=0.13), and rates of relapse events requiring rehospitalization within both 24 hours (0.6% vs 0.6%; P=0.88) and 7 days (1% vs 1%; P=0.90) of discharge.

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter, multiyear study of children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, we found that children present to a hospital in a relatively narrow time frame, but their time to recovery in the hospital is highly variable. Nonetheless, 96% of children continued to improve once they had: (1) improving or stable retractions rated as none/mild, (2) a decreasing or stable RR by age, (3) estimated average RAO2 saturation 90% and lowest RAO2 saturation of 88%, and (4) were hydrated. The 4% of children who worsened after clinically improving were more likely to be age <2 months, born <37 weeks, and present with more severe distress (ie, severe retractions, inadequate oral intake, or apnea). Based on the low risk of worsening after clinical improvement, especially among children admitted to the regular ward (2%), we believe these 4 clinical criteria could be used as discharge criteria for this common pediatric illness with a predominantly monophasic clinical course.

Variability in hospital LOS for children with bronchiolitis exists in the United States[3] and internationally.[4, 5] Cheung and colleagues analyzed administrative data from over 75,000 children admitted for bronchiolitis in England between April 2007 and March 2010 and found sixfold variation in LOS between sites. They concluded that this LOS variability was due in part to providers' clinical decision making.[5] Srivastava and colleagues[23] addressed variable clinician decision making in bronchiolitis and 10 other common pediatric conditions by embedding discharge criteria developed by expert consensus into admission order sets. They found that for children with bronchiolitis, the embedded discharge criteria reduced the median LOS from 1.91 to 1.87 days. In contrast to the single‐center data presented by White and colleagues,[24] the prospective, multicenter MARC‐30 data provide a clear understanding of the normal clinical course for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis, determine if children clinically worsen after clinical improvement, and provide data about discharge criteria for children hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Although there is a lack of rigorous published data, the lower tract symptoms of bronchiolitis (eg, cough, retractions) are said to peak on days 5 to 7 of illness and then gradually resolve.[25] In the present study, we found that the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until hospital admission is less variable than the time from the onset of difficulty breathing until either clinical improvement or discharge. Although 75% of children have clinically improved within 7.5 days of difficulty breathing based on the IQR results, the remaining 25% may have a more prolonged recovery in the hospital of up to 3 weeks. Interestingly, prolonged recovery times from bronchiolitis have also been noted in children presenting to the ED[26] and in an outpatient population.[27] It is unclear why 20% to 25% of children at different levels of severity of illness have prolonged recovery from bronchiolitis, but this group of children requires further investigation.

Given the variability of recovery times, clinicians may have difficulty knowing when a child is ready for hospital discharge. One of the main stumbling blocks for discharge readiness in children with bronchiolitis is the interpretation of the oxygen saturation value.[6, 8, 9, 20, 28] However, it should be considered that interpreting the oxygen saturation in a child who is clinically improving in the hospital setting is different than interpreting the oxygen saturation of a child in the ED or the clinic whose clinical course is less certain.[22] In the hospital setting, using the oxygen saturation value in in the AAP guideline,[9] 4% of children clinically worsened after they met the improvement criteria, a clinical pattern observed previously with supplemental oxygen.[28] This unpredictability may explain some of the variation in providers' clinical decision making.[5] The children who worsened, and therefore deserve more cautious discharge planning, were young (<2 months), premature (<37 weeks gestational age), and presented in more severe distress. Those children admitted to the ICU from the ED worsened more commonly than children admitted to the ward (19% vs 2%). Interestingly, the viral etiology of the child's bronchiolitis did not influence whether a child worsened after reaching the improvement criteria. Therefore, although children with RV bronchiolitis have a shorter hospital LOS than children with RSV bronchiolitis,[11] the pattern of recovery did not differ by viral etiology.

In addition to unsafe discharges, clinicians may be concerned about the possibility of readmissions. Although somewhat controversial, hospital readmission is being used as a quality of care metric.[29, 30, 31] One response to minimize readmissions would be for clinicians to observe children for longer than clinically indicated.[32] However, shorter LOS is not necessarily associated with increased readmission rates.[33] Given that the geometric mean of hospital charges per child with bronchiolitis increased from $6380 in 2000 to $8530 in 2009,[34] the potential for safely reducing hospital LOS by using the discharge criteria proposed in the current study instead of other criteria[8] may net substantial cost savings. Furthermore, reducing LOS would decrease the time children expose others to these respiratory viruses and possibly reduce medical errors.[35]

Our study has some potential limitations. Because the study participants were all hospitalized, these data do not inform admission or discharge decisions from either the ED or the clinic; but other data address those clinical scenarios.[22] Also, the 16 sites that participated in this study were large, urban teaching hospitals. Consequently, these results are not necessarily generalizable to smaller community hospitals. Although numerous data points were required to enter the analytic cohort, only 9% of the sample was excluded for missing data. There were 214 children who did not meet our improvement criteria by the time of discharge. Although the inability to include these children in the analysis may be seen as a limitation, this practice variability underscores the need for more data about discharging hospitalized children with bronchiolitis. Last, site teams reviewed medical records daily. More frequent recording of the clinical course would have yielded more granular data, but the current methodology replicates how data are generally presented during patient care rounds, when decisions about suitability for discharge are often considered.

CONCLUSION

We documented in this large multicenter study that most children hospitalized with bronchiolitis had a wide range of time to recovery, but the vast majority continued to improve once they reached the identified clinical criteria that predict a safe discharge to home. The children who worsened after clinical improvement were more likely to be younger, premature infants presenting in more severe distress. Although additional prospective validation of these hospital discharge criteria is warranted, these data may help clinicians make more evidence‐based discharge decisions for a common pediatric illness with high practice variation, both in the United States[3] and in other countries.[4, 5]

Acknowledgements