User login

Linearly Curved, Blackish Macule on the Wrist

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

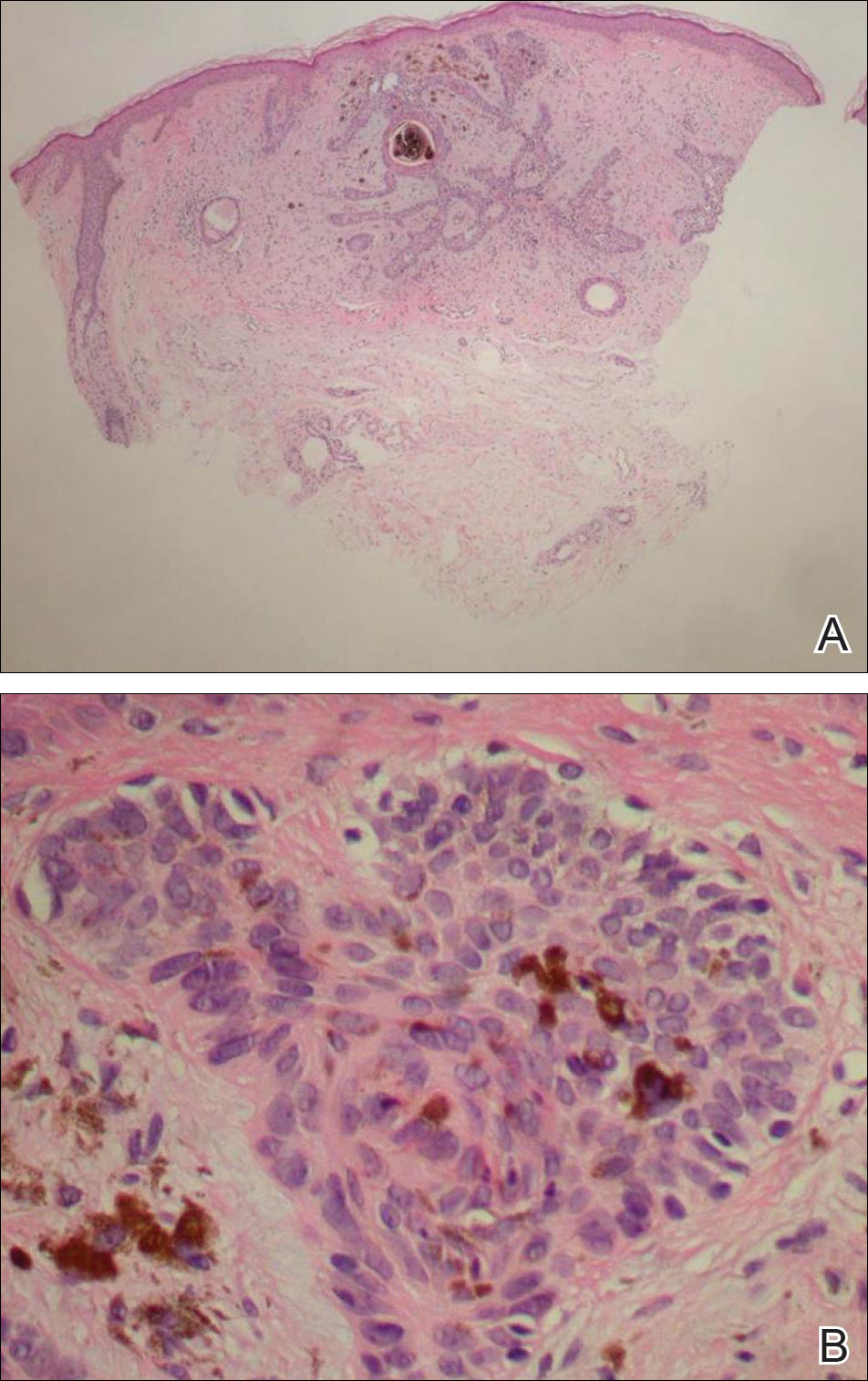

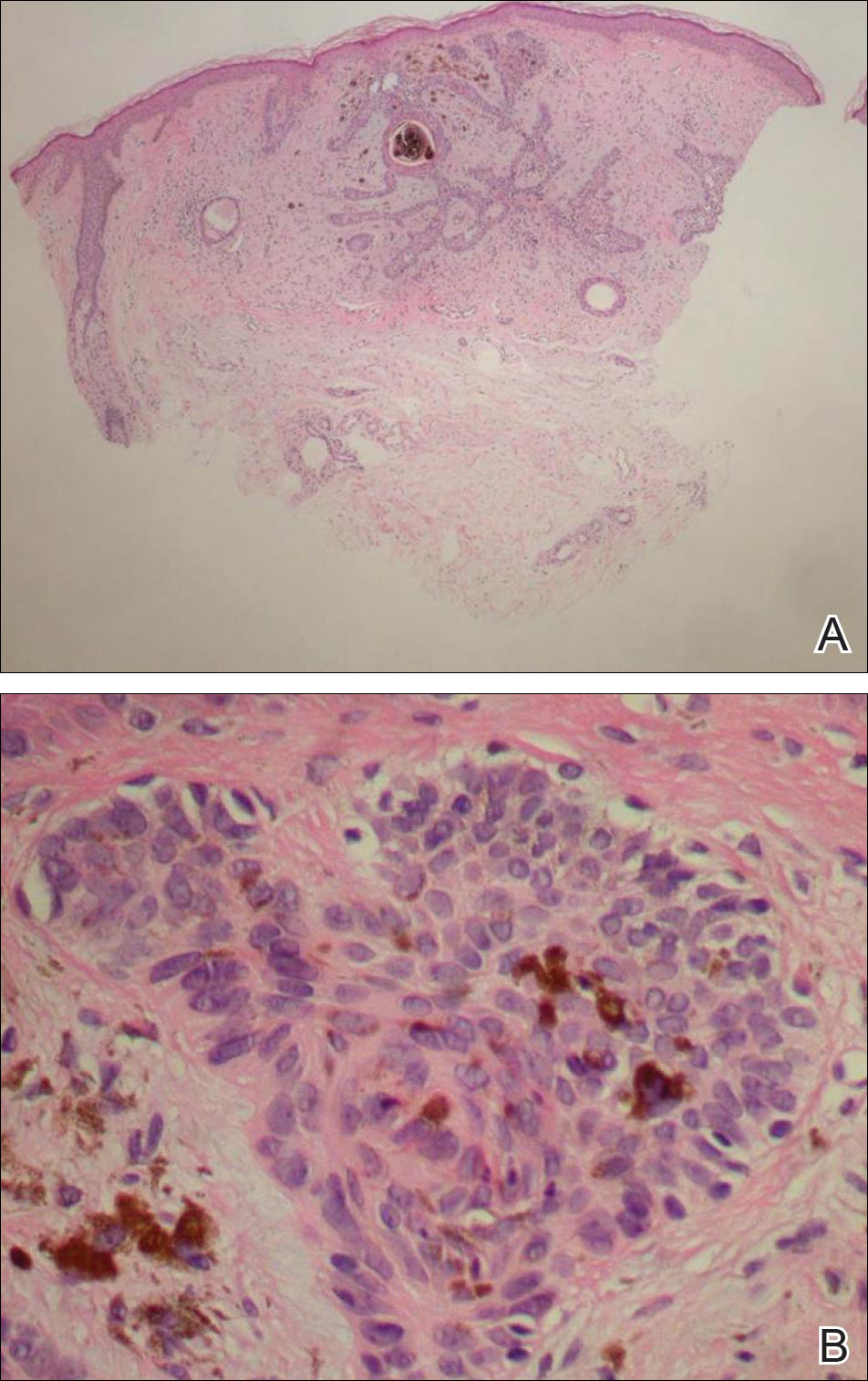

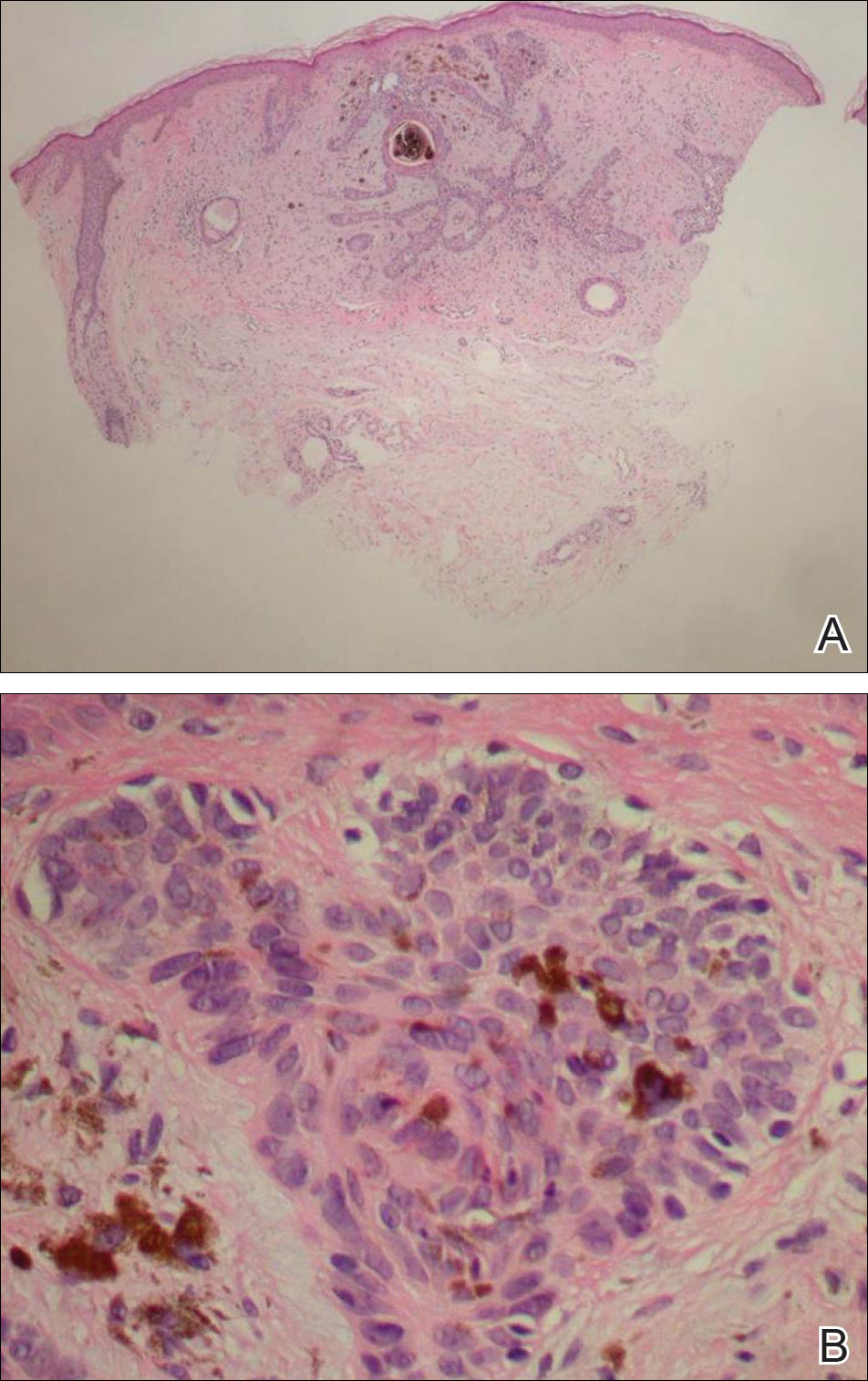

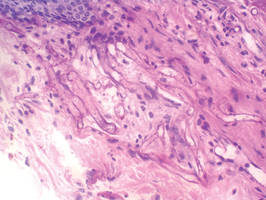

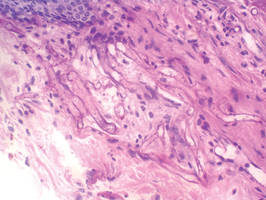

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Rhino-orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis

A 56-year-old woman presented with painful, erythematous to violaceous patches with necrosis of the left eye and periorbital area of 1 day’s duration. She reported headaches and periorbital pain in the 3 weeks prior to presentation. She was being treated for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and end-stage renal disease. The patient denied prior trauma to the area.

The Diagnosis: Rhino-orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis

Cutaneous examination revealed a dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center involving the left eye and periorbital area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included herpes zoster, cellulitis, and fungal infection. We obtained patient consent for a punch biopsy. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the orbit and head showed involvement of the periorbital soft tissues; the ethmoidal, sphenoidal, and maxillary sinuses; and the left medial temporal lobe. The patient was started on an empirical antifungal treatment of amphotericin B deoxycholate 50 mg daily but died 4 days later due to multiorgan failure.

|

| Figure 1. A dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center on the left eye and periorbital area. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (periodic acid–Schiff, original magnification ×400). |

Mucormycosis is a rare but fatal infection that may rapidly progress.1 Risk factors include defects in host defense such as malignancy, immunodeficiency from bone marrow or solid organ transplantation, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, abnormal metabolic states, and deferoxamine use.1,2 Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis usually starts with eye or facial pain and unilateral facial swelling.3,4 Visual impairment, fever, and mental status changes may follow.1,3,4 Skin findings may progress from erythema to violaceous color changes and lastly to a black necrotic eschar resulting from tissue infarction.5

Radiologic imaging may be helpful but rarely is diagnostic in mucormycosis, and reliable serologic tests are lacking.1 Therefore, suspicion of mucormycosis based on clinical and histopathologic factors followed by immediate initiation of empirical antifungal treatment is critical. The key factors in treating mucormycosis include early diagnosis, correction of underlying risk factors, prompt antifungal therapy, and surgical debridement.1 Amphotericin B deoxycholate and its lipid derivatives (eg, amphotericin B lipid complex, liposomal amphotericin B) are the standard antifungal agents used in the treatment of mucormycosis.6,7 Posaconazole is an extended-spectrum triazole with in vitro activity against Mucorales. Posaconazole may be useful as salvage therapy; however, strong clinical evidence to support its role as a primary therapeutic agent is lacking in the literature.6,7 Blood vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis can result in poor penetration of antifungal agents to the infection site; therefore, surgical debridement also may be critical for complete eradication of the disease.6 Confirmative diagnosis of mucormycosis can be made based on histopathologic findings.

Our case highlights the importance of clinician awareness of the typical presentation of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis to ensure prompt diagnosis and initiation of immediate treatment of this possibly fatal infection.

1. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:556-569.

2. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1140-1143.

3. Peterson KL, Wang M, Canalis RF, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: evolution of the disease and treatment options. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:855-862.

4. Khor BS, Lee MH, Leu HS, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:266-269.

5. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Sambatakou H, et al. Mucormycosis: ten-year experience at a tertiary-care center in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:753-756.

6. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS. Recent advances in the treatment of mucormycosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:423-429.

7. Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, Sule O, et al. Posaconazole for the treatment of mucormycosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:465-473.

A 56-year-old woman presented with painful, erythematous to violaceous patches with necrosis of the left eye and periorbital area of 1 day’s duration. She reported headaches and periorbital pain in the 3 weeks prior to presentation. She was being treated for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and end-stage renal disease. The patient denied prior trauma to the area.

The Diagnosis: Rhino-orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis

Cutaneous examination revealed a dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center involving the left eye and periorbital area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included herpes zoster, cellulitis, and fungal infection. We obtained patient consent for a punch biopsy. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the orbit and head showed involvement of the periorbital soft tissues; the ethmoidal, sphenoidal, and maxillary sinuses; and the left medial temporal lobe. The patient was started on an empirical antifungal treatment of amphotericin B deoxycholate 50 mg daily but died 4 days later due to multiorgan failure.

|

| Figure 1. A dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center on the left eye and periorbital area. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (periodic acid–Schiff, original magnification ×400). |

Mucormycosis is a rare but fatal infection that may rapidly progress.1 Risk factors include defects in host defense such as malignancy, immunodeficiency from bone marrow or solid organ transplantation, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, abnormal metabolic states, and deferoxamine use.1,2 Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis usually starts with eye or facial pain and unilateral facial swelling.3,4 Visual impairment, fever, and mental status changes may follow.1,3,4 Skin findings may progress from erythema to violaceous color changes and lastly to a black necrotic eschar resulting from tissue infarction.5

Radiologic imaging may be helpful but rarely is diagnostic in mucormycosis, and reliable serologic tests are lacking.1 Therefore, suspicion of mucormycosis based on clinical and histopathologic factors followed by immediate initiation of empirical antifungal treatment is critical. The key factors in treating mucormycosis include early diagnosis, correction of underlying risk factors, prompt antifungal therapy, and surgical debridement.1 Amphotericin B deoxycholate and its lipid derivatives (eg, amphotericin B lipid complex, liposomal amphotericin B) are the standard antifungal agents used in the treatment of mucormycosis.6,7 Posaconazole is an extended-spectrum triazole with in vitro activity against Mucorales. Posaconazole may be useful as salvage therapy; however, strong clinical evidence to support its role as a primary therapeutic agent is lacking in the literature.6,7 Blood vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis can result in poor penetration of antifungal agents to the infection site; therefore, surgical debridement also may be critical for complete eradication of the disease.6 Confirmative diagnosis of mucormycosis can be made based on histopathologic findings.

Our case highlights the importance of clinician awareness of the typical presentation of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis to ensure prompt diagnosis and initiation of immediate treatment of this possibly fatal infection.

A 56-year-old woman presented with painful, erythematous to violaceous patches with necrosis of the left eye and periorbital area of 1 day’s duration. She reported headaches and periorbital pain in the 3 weeks prior to presentation. She was being treated for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and end-stage renal disease. The patient denied prior trauma to the area.

The Diagnosis: Rhino-orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis

Cutaneous examination revealed a dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center involving the left eye and periorbital area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included herpes zoster, cellulitis, and fungal infection. We obtained patient consent for a punch biopsy. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (Figure 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the orbit and head showed involvement of the periorbital soft tissues; the ethmoidal, sphenoidal, and maxillary sinuses; and the left medial temporal lobe. The patient was started on an empirical antifungal treatment of amphotericin B deoxycholate 50 mg daily but died 4 days later due to multiorgan failure.

|

| Figure 1. A dusky, erythematous to violaceous patch with a necrotic center on the left eye and periorbital area. |

|

| Figure 2. Histopathologic examination revealed irregularly shaped, broad, nonseptate hyphae with right-angle branching (periodic acid–Schiff, original magnification ×400). |

Mucormycosis is a rare but fatal infection that may rapidly progress.1 Risk factors include defects in host defense such as malignancy, immunodeficiency from bone marrow or solid organ transplantation, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, abnormal metabolic states, and deferoxamine use.1,2 Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis usually starts with eye or facial pain and unilateral facial swelling.3,4 Visual impairment, fever, and mental status changes may follow.1,3,4 Skin findings may progress from erythema to violaceous color changes and lastly to a black necrotic eschar resulting from tissue infarction.5

Radiologic imaging may be helpful but rarely is diagnostic in mucormycosis, and reliable serologic tests are lacking.1 Therefore, suspicion of mucormycosis based on clinical and histopathologic factors followed by immediate initiation of empirical antifungal treatment is critical. The key factors in treating mucormycosis include early diagnosis, correction of underlying risk factors, prompt antifungal therapy, and surgical debridement.1 Amphotericin B deoxycholate and its lipid derivatives (eg, amphotericin B lipid complex, liposomal amphotericin B) are the standard antifungal agents used in the treatment of mucormycosis.6,7 Posaconazole is an extended-spectrum triazole with in vitro activity against Mucorales. Posaconazole may be useful as salvage therapy; however, strong clinical evidence to support its role as a primary therapeutic agent is lacking in the literature.6,7 Blood vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis can result in poor penetration of antifungal agents to the infection site; therefore, surgical debridement also may be critical for complete eradication of the disease.6 Confirmative diagnosis of mucormycosis can be made based on histopathologic findings.

Our case highlights the importance of clinician awareness of the typical presentation of rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis to ensure prompt diagnosis and initiation of immediate treatment of this possibly fatal infection.

1. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:556-569.

2. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1140-1143.

3. Peterson KL, Wang M, Canalis RF, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: evolution of the disease and treatment options. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:855-862.

4. Khor BS, Lee MH, Leu HS, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:266-269.

5. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Sambatakou H, et al. Mucormycosis: ten-year experience at a tertiary-care center in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:753-756.

6. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS. Recent advances in the treatment of mucormycosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:423-429.

7. Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, Sule O, et al. Posaconazole for the treatment of mucormycosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:465-473.

1. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr, Ibrahim A. Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:556-569.

2. McNulty JS. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: predisposing factors. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1140-1143.

3. Peterson KL, Wang M, Canalis RF, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis: evolution of the disease and treatment options. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:855-862.

4. Khor BS, Lee MH, Leu HS, et al. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:266-269.

5. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Sambatakou H, et al. Mucormycosis: ten-year experience at a tertiary-care center in Greece. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:753-756.

6. Spellberg B, Ibrahim AS. Recent advances in the treatment of mucormycosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:423-429.

7. Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, Sule O, et al. Posaconazole for the treatment of mucormycosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2011;38:465-473.