User login

Multiple Yellow-Brown Papules on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Syringoma

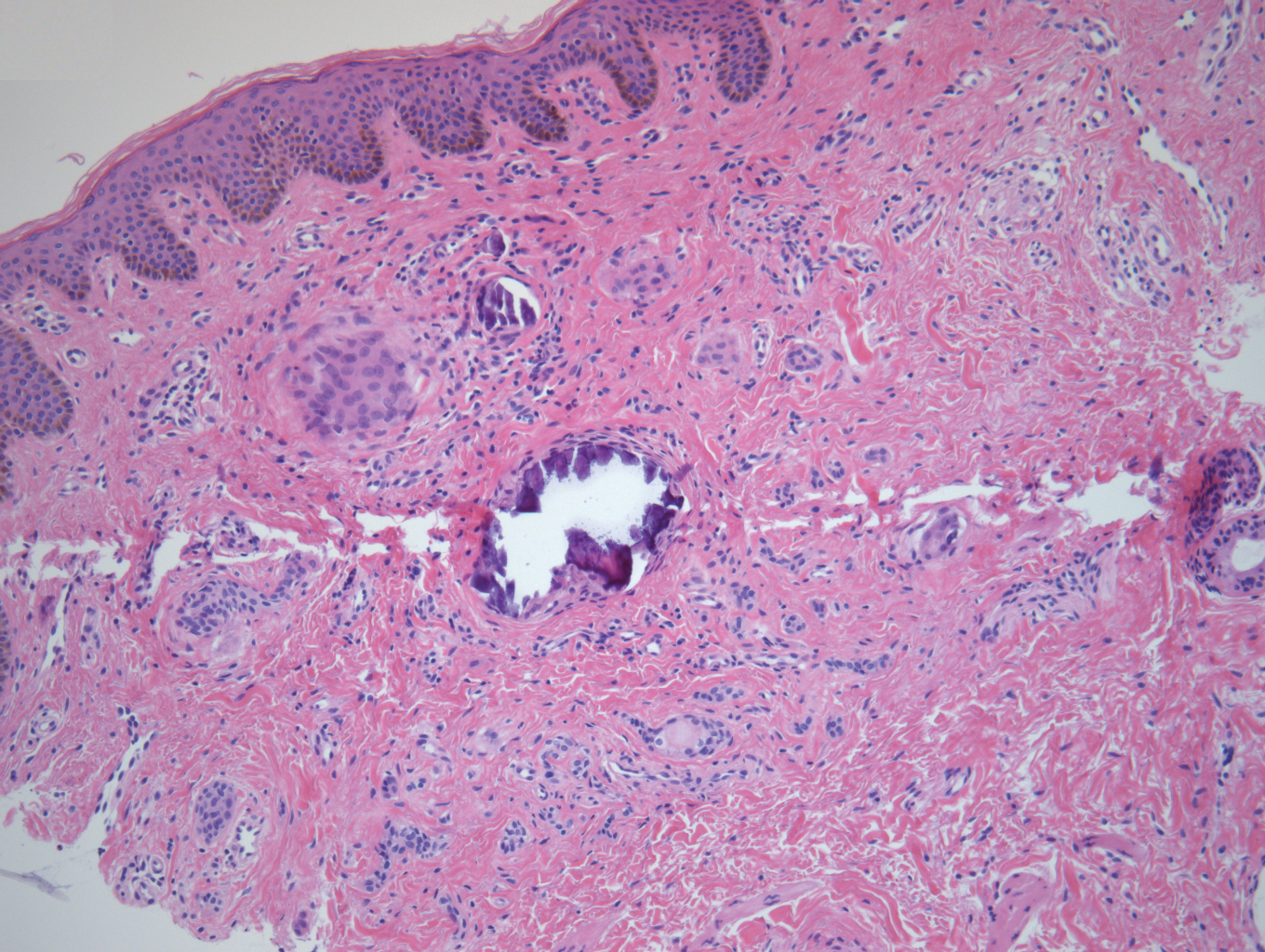

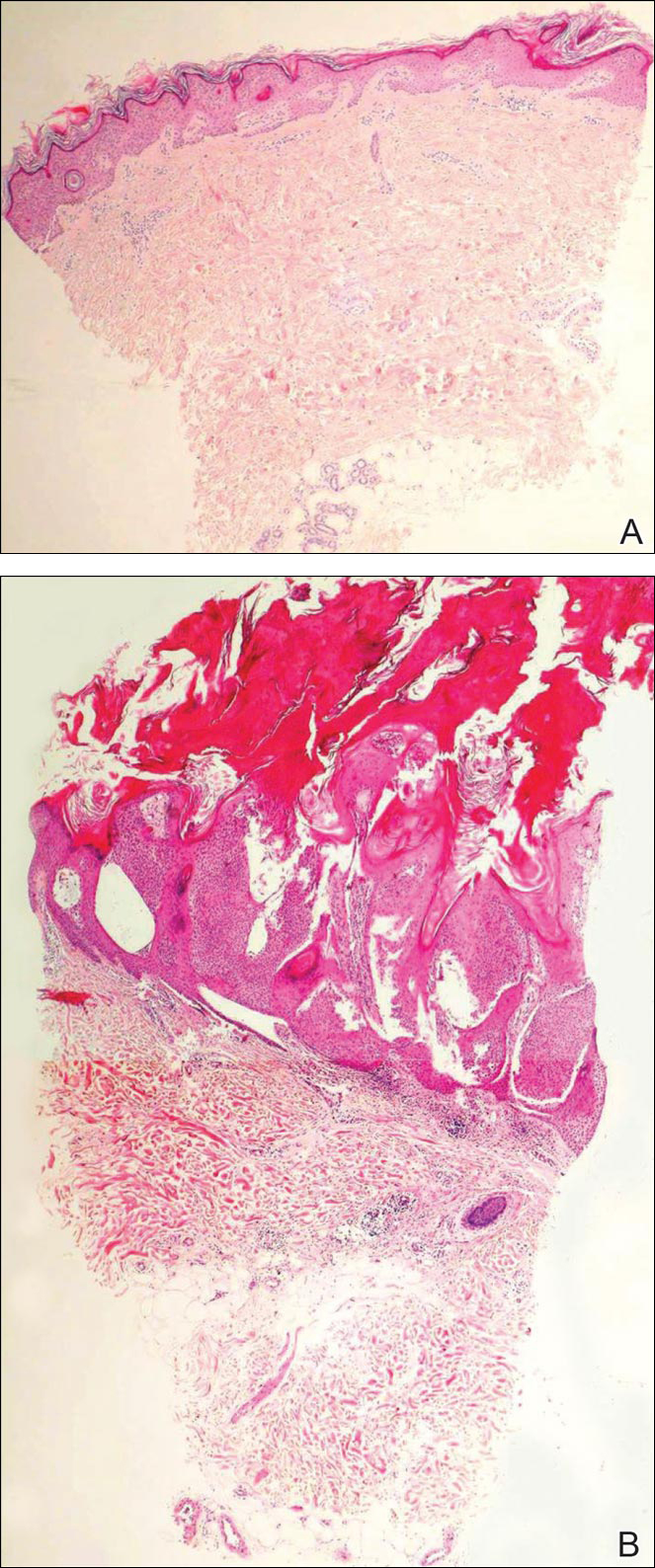

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the penis was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed many tadpole-shaped cords of epithelial cells and small ducts in the dermis (Figure). Based on clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of eruptive syringoma was made. The patient declined treatment.

Syringomas are common benign eccrine neoplasms. They present clinically as small flesh-colored to brownish papules symmetrically distributed on the face, neck, trunk, pubic area, arms, and legs.1-3 Classic syringoma occurs more frequently in young adult women.1 Eruptive syringoma is a rare variant, and the age of onset ranges from 3 to 50 years.1-13 Eruptive syringoma is the term for multiple lesions that occur synchronously in any part of the body.1,4,13 The term eruptive is not the opposite of localized and refers to the time of onset of the lesion. There may be both a generalized eruptive syringoma or a localized eruptive syringoma depending on the distribution of the lesions.1 The most common site for syringoma occurrence is the eyelid; penile syringoma is extremely rare. Several cases of penile syringoma have been reported, but eruptive penile syringoma is rare.3,5-10,12,13

Histopathology is essential for the diagnosis of syringoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows multiple small cystic ducts and epithelial cell nests in the dermis. Ductal structures sometimes appear tadpolelike or comma shaped depending on the section.1,2,7,12

The clinical differential diagnosis of syringoma includes sebaceous hyperplasia, verruca plana, molluscum contagiosum, bowenoid papulosis, condyloma acuminatum, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, milia, angiofibroma, epidermal cyst, calcinosis cutis, granuloma annulare, and sarcoidosis.3,8,12

Because syringoma is benign, treatment is not necessary unless there is a cosmetic problem.3,5,7,8,12 There is no satisfactory treatment of eruptive penile syringoma. Treatment options include topical tretinoin and adapalene, oral isotretinoin, cryotherapy, microelectrodesiccation with an epilating needle, dermabrasion, CO2 laser, and surgical excision.2,3,7,8,12

Adult patients with penile syringoma may be concerned about sexually transmitted diseases due to the appearance of the papules. If cosmesis is not an issue, clinicians should reassure the patient after a biopsy that the lesions are benign and self-limiting without recommending treatment.

- Ghanadan A, Khosravi M. Cutaneous syringoma: a clinicopathologic study of 34 new cases and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaro JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246.

- Baek JO, Jee HJ, Kim TK, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas spreading to the pubic area and lower abdomen. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:116-118.

- Pruzan DL, Esterly NB, Prose NS. Eruptive syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1119-1120.

- Olson JM, Robles DT, Argenyi ZB, et al. Multiple penile syringomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2 suppl 1):S46-S47.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Huang C, Wang W, Wu B. Multiple brownish papules on the penile shaft. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:404.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:E21.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e206-207.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:e21.

- Dhossche JM, Brodell RT, Al Hmada Y, et al. Skin-colored papules of the penis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:145-146.

- Todd PS, Gordon SC, Rovner RL, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas in an adolescent: novel approach with serial microexcisions and suture-adhesive repair. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E57-E60.

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Syringoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the penis was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed many tadpole-shaped cords of epithelial cells and small ducts in the dermis (Figure). Based on clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of eruptive syringoma was made. The patient declined treatment.

Syringomas are common benign eccrine neoplasms. They present clinically as small flesh-colored to brownish papules symmetrically distributed on the face, neck, trunk, pubic area, arms, and legs.1-3 Classic syringoma occurs more frequently in young adult women.1 Eruptive syringoma is a rare variant, and the age of onset ranges from 3 to 50 years.1-13 Eruptive syringoma is the term for multiple lesions that occur synchronously in any part of the body.1,4,13 The term eruptive is not the opposite of localized and refers to the time of onset of the lesion. There may be both a generalized eruptive syringoma or a localized eruptive syringoma depending on the distribution of the lesions.1 The most common site for syringoma occurrence is the eyelid; penile syringoma is extremely rare. Several cases of penile syringoma have been reported, but eruptive penile syringoma is rare.3,5-10,12,13

Histopathology is essential for the diagnosis of syringoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows multiple small cystic ducts and epithelial cell nests in the dermis. Ductal structures sometimes appear tadpolelike or comma shaped depending on the section.1,2,7,12

The clinical differential diagnosis of syringoma includes sebaceous hyperplasia, verruca plana, molluscum contagiosum, bowenoid papulosis, condyloma acuminatum, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, milia, angiofibroma, epidermal cyst, calcinosis cutis, granuloma annulare, and sarcoidosis.3,8,12

Because syringoma is benign, treatment is not necessary unless there is a cosmetic problem.3,5,7,8,12 There is no satisfactory treatment of eruptive penile syringoma. Treatment options include topical tretinoin and adapalene, oral isotretinoin, cryotherapy, microelectrodesiccation with an epilating needle, dermabrasion, CO2 laser, and surgical excision.2,3,7,8,12

Adult patients with penile syringoma may be concerned about sexually transmitted diseases due to the appearance of the papules. If cosmesis is not an issue, clinicians should reassure the patient after a biopsy that the lesions are benign and self-limiting without recommending treatment.

The Diagnosis: Eruptive Syringoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the penis was performed. Histopathologic examination revealed many tadpole-shaped cords of epithelial cells and small ducts in the dermis (Figure). Based on clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of eruptive syringoma was made. The patient declined treatment.

Syringomas are common benign eccrine neoplasms. They present clinically as small flesh-colored to brownish papules symmetrically distributed on the face, neck, trunk, pubic area, arms, and legs.1-3 Classic syringoma occurs more frequently in young adult women.1 Eruptive syringoma is a rare variant, and the age of onset ranges from 3 to 50 years.1-13 Eruptive syringoma is the term for multiple lesions that occur synchronously in any part of the body.1,4,13 The term eruptive is not the opposite of localized and refers to the time of onset of the lesion. There may be both a generalized eruptive syringoma or a localized eruptive syringoma depending on the distribution of the lesions.1 The most common site for syringoma occurrence is the eyelid; penile syringoma is extremely rare. Several cases of penile syringoma have been reported, but eruptive penile syringoma is rare.3,5-10,12,13

Histopathology is essential for the diagnosis of syringoma. Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows multiple small cystic ducts and epithelial cell nests in the dermis. Ductal structures sometimes appear tadpolelike or comma shaped depending on the section.1,2,7,12

The clinical differential diagnosis of syringoma includes sebaceous hyperplasia, verruca plana, molluscum contagiosum, bowenoid papulosis, condyloma acuminatum, lichen planus, lichen nitidus, milia, angiofibroma, epidermal cyst, calcinosis cutis, granuloma annulare, and sarcoidosis.3,8,12

Because syringoma is benign, treatment is not necessary unless there is a cosmetic problem.3,5,7,8,12 There is no satisfactory treatment of eruptive penile syringoma. Treatment options include topical tretinoin and adapalene, oral isotretinoin, cryotherapy, microelectrodesiccation with an epilating needle, dermabrasion, CO2 laser, and surgical excision.2,3,7,8,12

Adult patients with penile syringoma may be concerned about sexually transmitted diseases due to the appearance of the papules. If cosmesis is not an issue, clinicians should reassure the patient after a biopsy that the lesions are benign and self-limiting without recommending treatment.

- Ghanadan A, Khosravi M. Cutaneous syringoma: a clinicopathologic study of 34 new cases and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaro JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246.

- Baek JO, Jee HJ, Kim TK, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas spreading to the pubic area and lower abdomen. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:116-118.

- Pruzan DL, Esterly NB, Prose NS. Eruptive syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1119-1120.

- Olson JM, Robles DT, Argenyi ZB, et al. Multiple penile syringomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2 suppl 1):S46-S47.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Huang C, Wang W, Wu B. Multiple brownish papules on the penile shaft. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:404.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:E21.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e206-207.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:e21.

- Dhossche JM, Brodell RT, Al Hmada Y, et al. Skin-colored papules of the penis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:145-146.

- Todd PS, Gordon SC, Rovner RL, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas in an adolescent: novel approach with serial microexcisions and suture-adhesive repair. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E57-E60.

- Ghanadan A, Khosravi M. Cutaneous syringoma: a clinicopathologic study of 34 new cases and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Soler-Carrillo J, Estrach T, Mascaro JM. Eruptive syringoma: 27 new cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:242-246.

- Baek JO, Jee HJ, Kim TK, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas spreading to the pubic area and lower abdomen. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:116-118.

- Pruzan DL, Esterly NB, Prose NS. Eruptive syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1119-1120.

- Olson JM, Robles DT, Argenyi ZB, et al. Multiple penile syringomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2 suppl 1):S46-S47.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Huang C, Wang W, Wu B. Multiple brownish papules on the penile shaft. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:404.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:E21.

- Mitkov M, Balagula Y, Taube JM, et al. Plaque-like syringoma with involvement of deep reticular dermis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e206-207.

- Vaca EE, Mundinger GS, Zelken JA, et al. Surgical excision of multiple penile syringomas with scrotal flap reconstruction. Eplasty. 2014;14:e21.

- Dhossche JM, Brodell RT, Al Hmada Y, et al. Skin-colored papules of the penis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:145-146.

- Todd PS, Gordon SC, Rovner RL, et al. Eruptive penile syringomas in an adolescent: novel approach with serial microexcisions and suture-adhesive repair. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E57-E60.

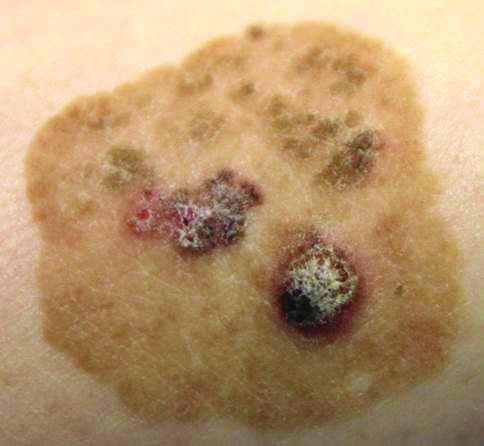

A 12-year-old boy presented with multiple asymptomatic, 0.1-cm, yellow-brown papules on the penile shaft of several years' duration. The lesions appeared suddenly. The patient had no history of trauma, injection, or an underlying disorder.

Brown Papules and a Plaque on the Calf

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

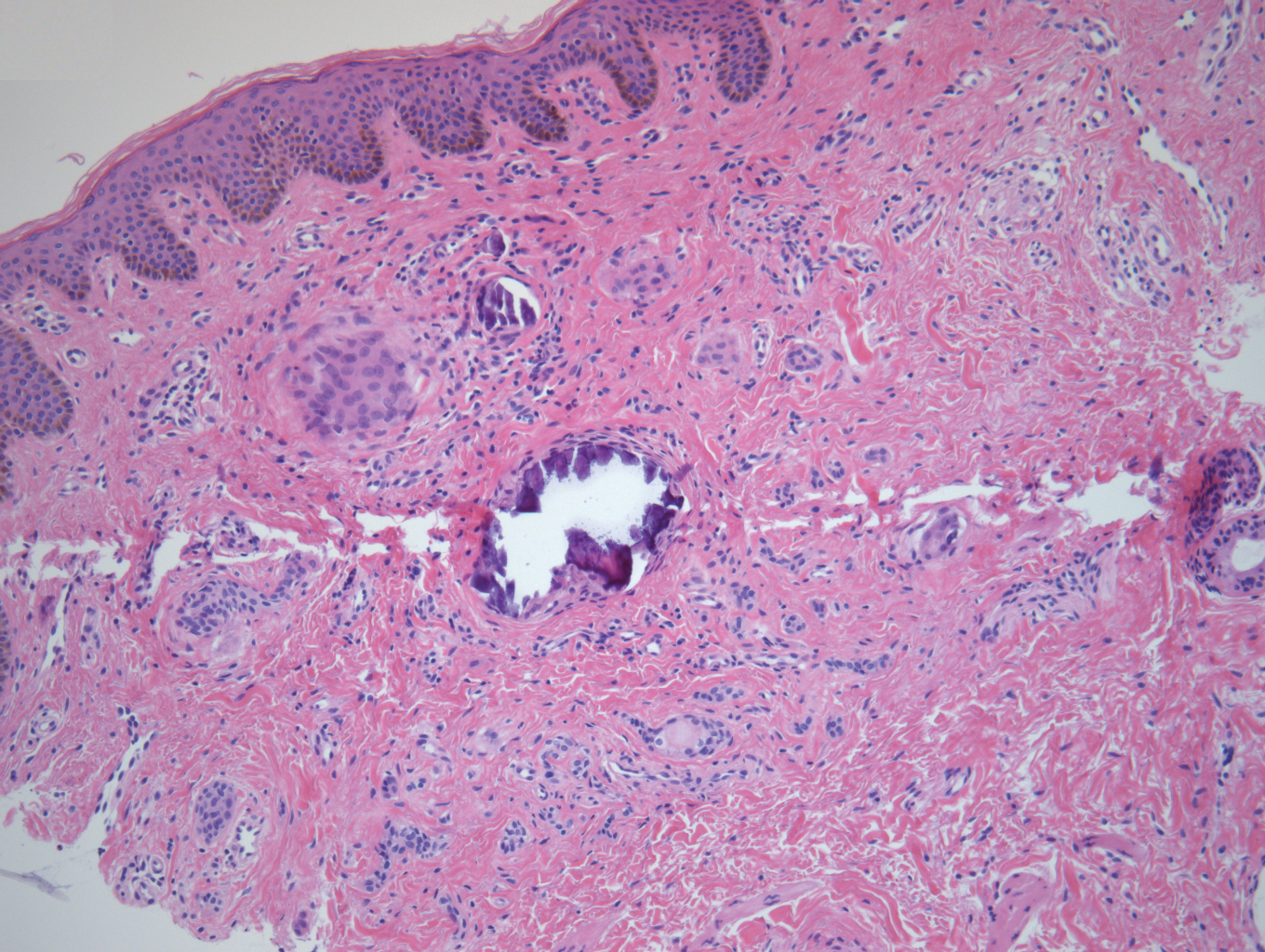

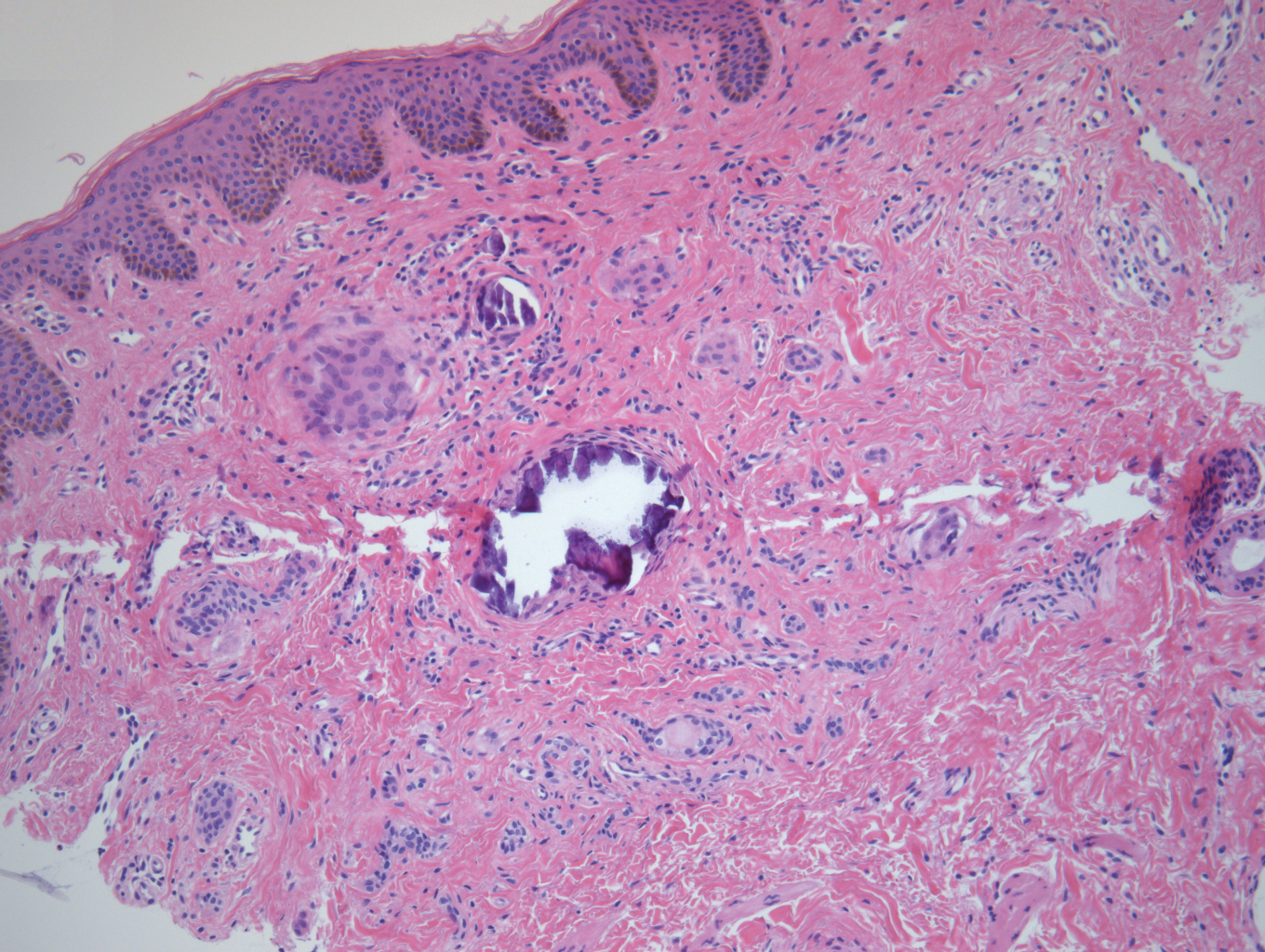

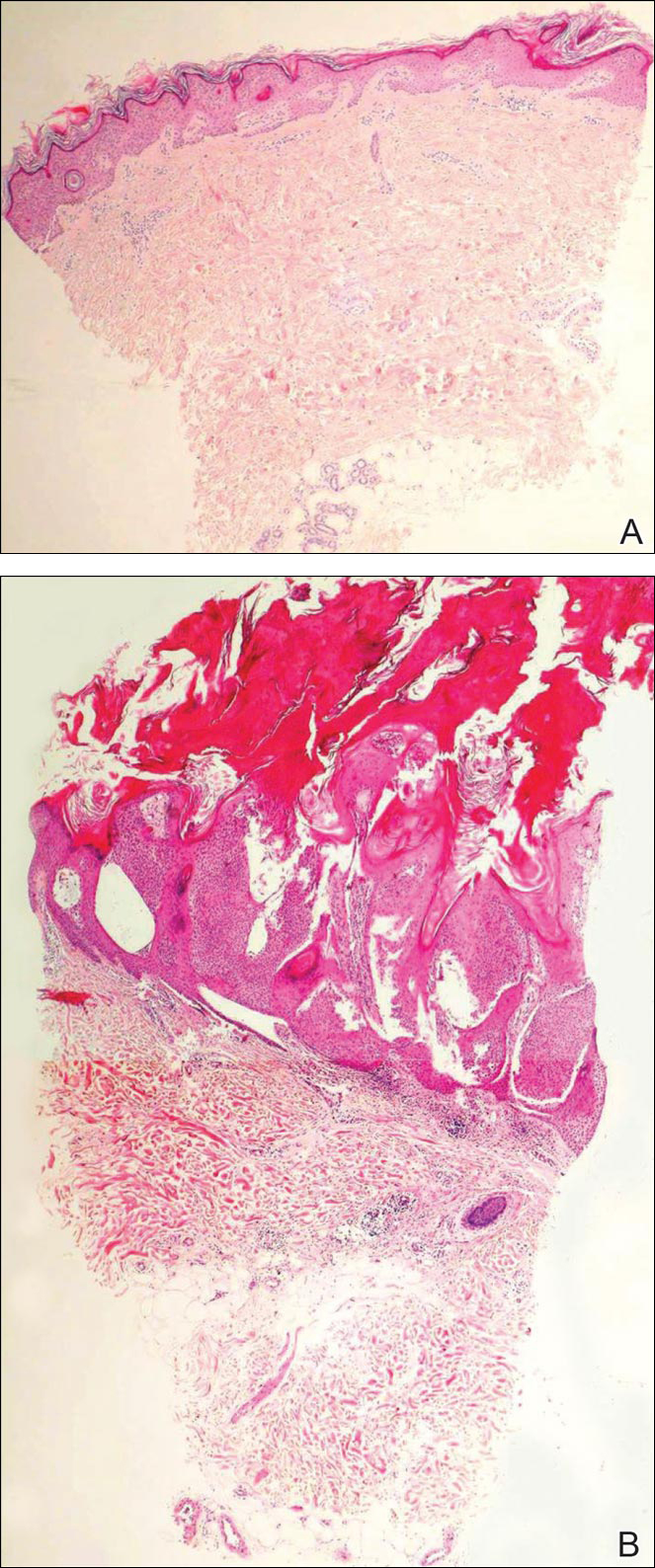

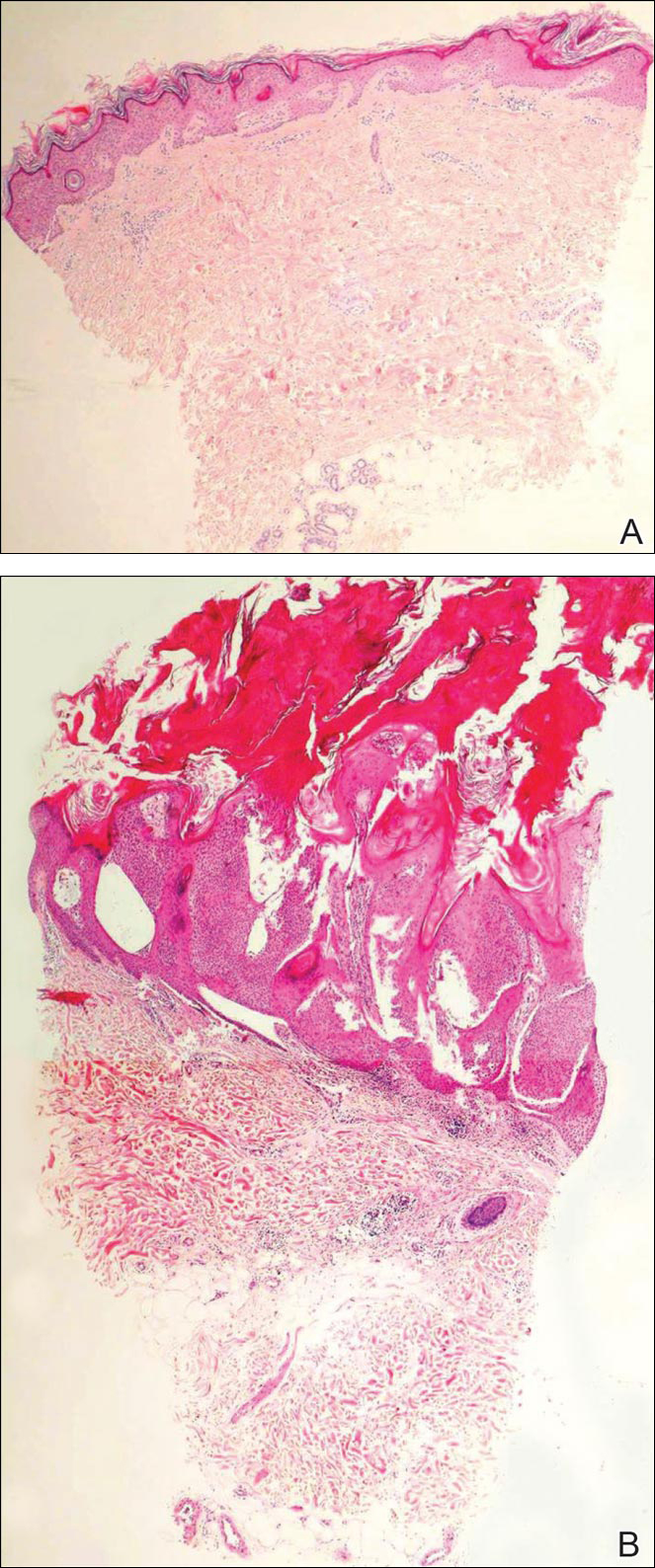

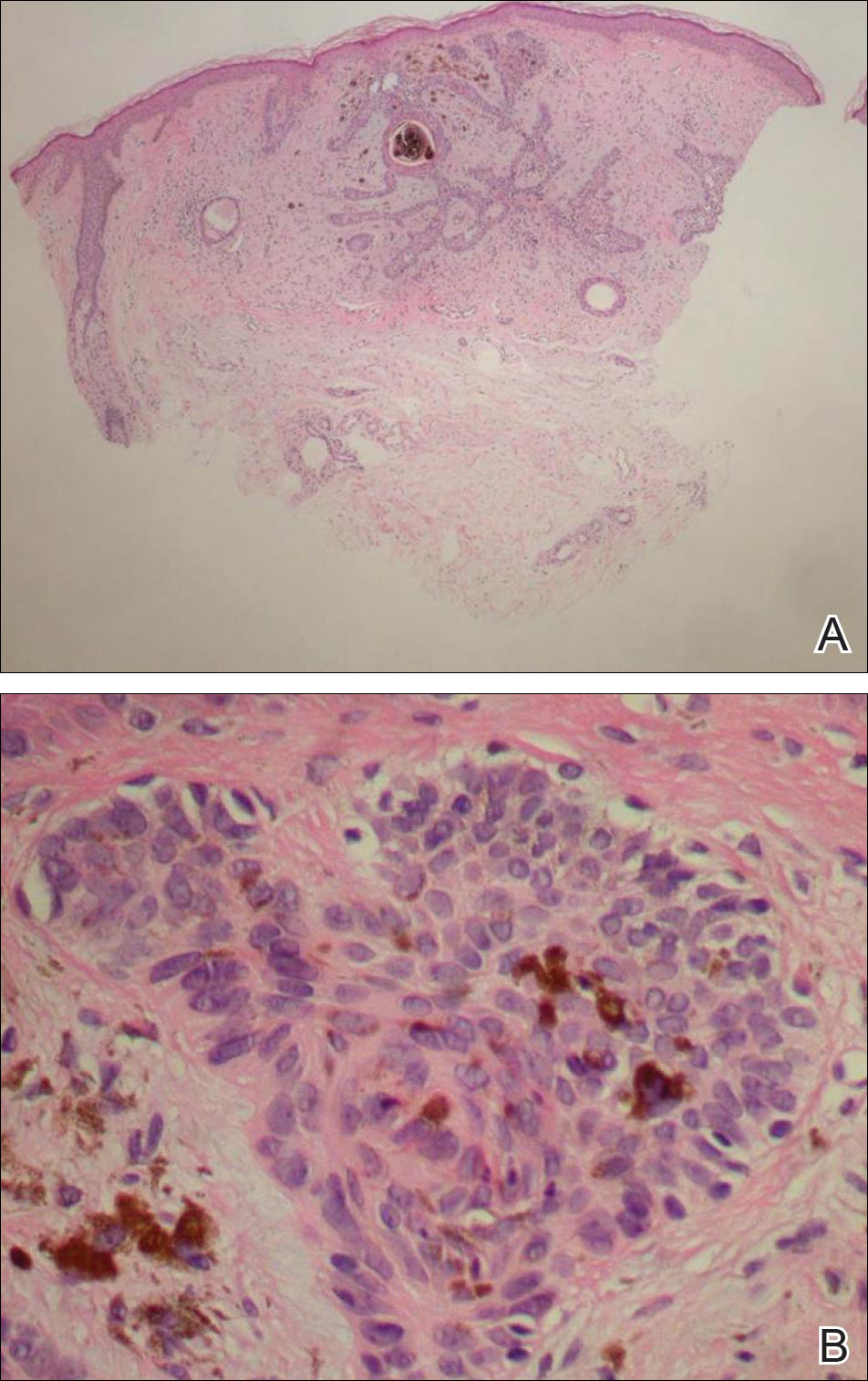

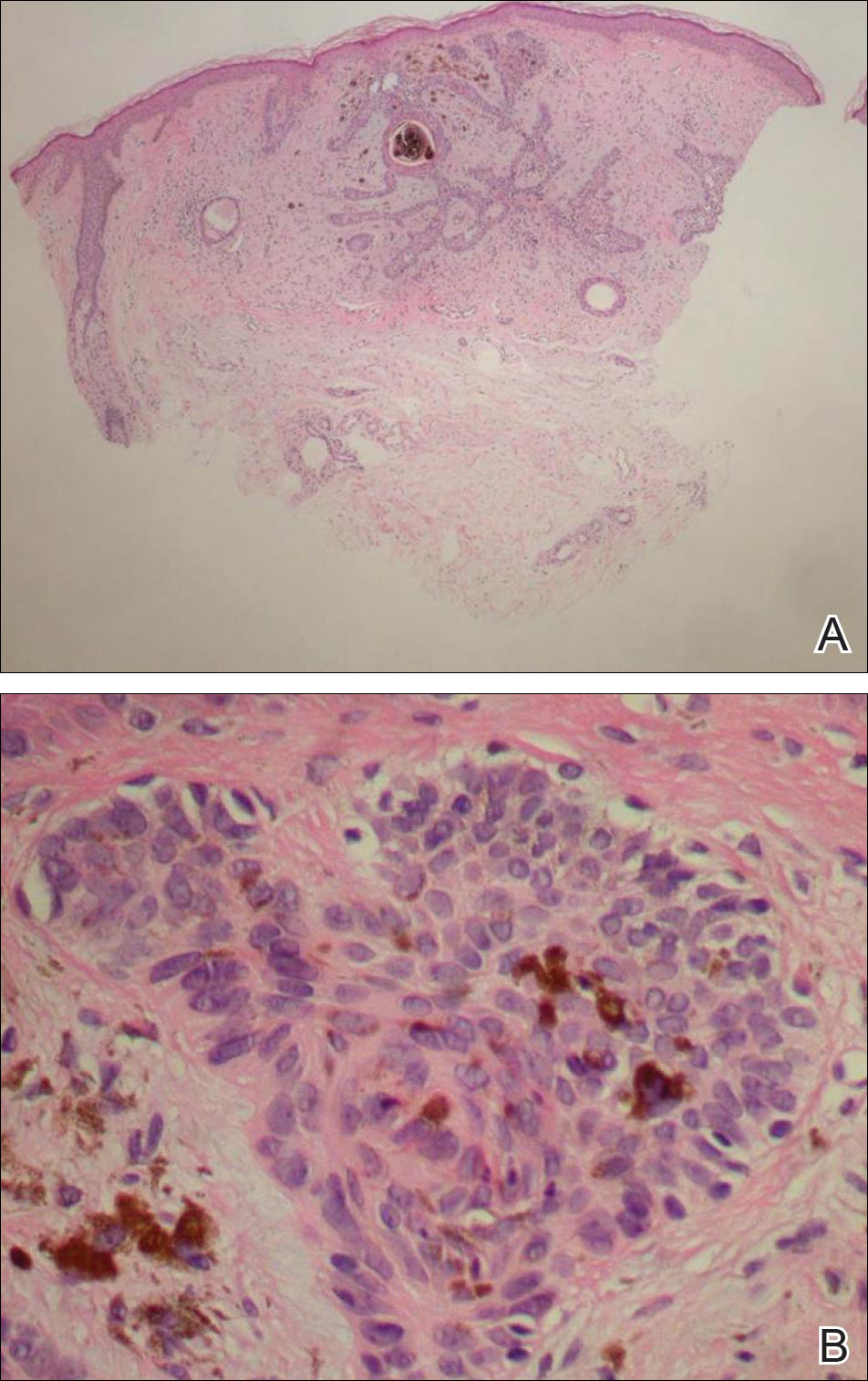

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

The Diagnosis: Irritated Seborrheic Keratosis

Biopsies of one of the protruding papules and the underlying plaque were performed. The specimen from the papule showed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, papillomatosis, and a flattened dermoepidermal junction with demarcated horizontal margin, which demonstrated apparent upward growth of the epidermis. Moderate lymphocytic infiltration in the upper dermis also was observed (Figure, A). The histologic findings of the plaque showed acanthosis, several pseudohorn cysts, hyperpigmentation of the basal layer, and a horizontal demarcation of the dermoepidermal junction (Figure, B).

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign epidermal tumor of the skin with variable appearance.1 It usually begins with well-circumscribed, dull, flat, tan or brown patches that then grow into waxy verrucous papules.1 There are many clinicopathologic variants of SK such as common SK, stucco keratosis, and dermatosis papulosa nigra in clinical variation, as well as acanthotic, hyperkeratotic, clonal, reticulated, irritated, and melanoacanthoma subtypes based on histological variation.2,3

Seborrheic keratosis is a tumor of keratinocytic origin. Although genetics, sun exposure,4 and human papillomavirus infection5 are thought to be causative factors, the precise etiology of SK is unknown.1

The histology of SK shows monotonous basaloid tumor cells without atypia. It generally is comprised of focal acanthosis and papillomatosis with a sharp flat base. Intraepithelial horn pseudocysts are notable features of SK and increased melanin often is seen.2,6

Irritated SK is a histologic variant of SK that has been mechanically or chemically irritated or is involved in immunologic responses. Histologically, the dermis underlying an SK lesion filled with a dense lymphocytic infiltration is characteristic.1,2

For symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable lesions, complete removal of the lesion is the preferred treatment. Cryotherapy, electrodesiccation followed by curettage, curettage followed by desiccation, laser ablation, and surgical excision are effective treatments.1

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

- Valencia DT, Nicholas RS, Ken KL, et al. Benign epithelial tumors, hamartomas, and hyperplasias. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2012:1319-1336.

- Kirkharn N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:791-850.

- Rajesh G, Thappa DM, Jaisankar TJ, et al. Spectrum of seborrheic keratoses in South Indians: a clinical and dermoscopic study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:483-488.

- Yeatman JM, Kilkenny M, Marks R. The prevalence of seborrhoeic keratoses in an Australian population: does exposure to sunlight play a part in their frequency? Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:411-414.

- Li YH, Chen G, Dong XP, et al. Detection of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus DNA in nongenital seborrhoeic keratosis. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1060-1065.

- Brinster NK, Liu V, Diwan AH, et al. Dermatopathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2011.

Linearly Curved, Blackish Macule on the Wrist

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

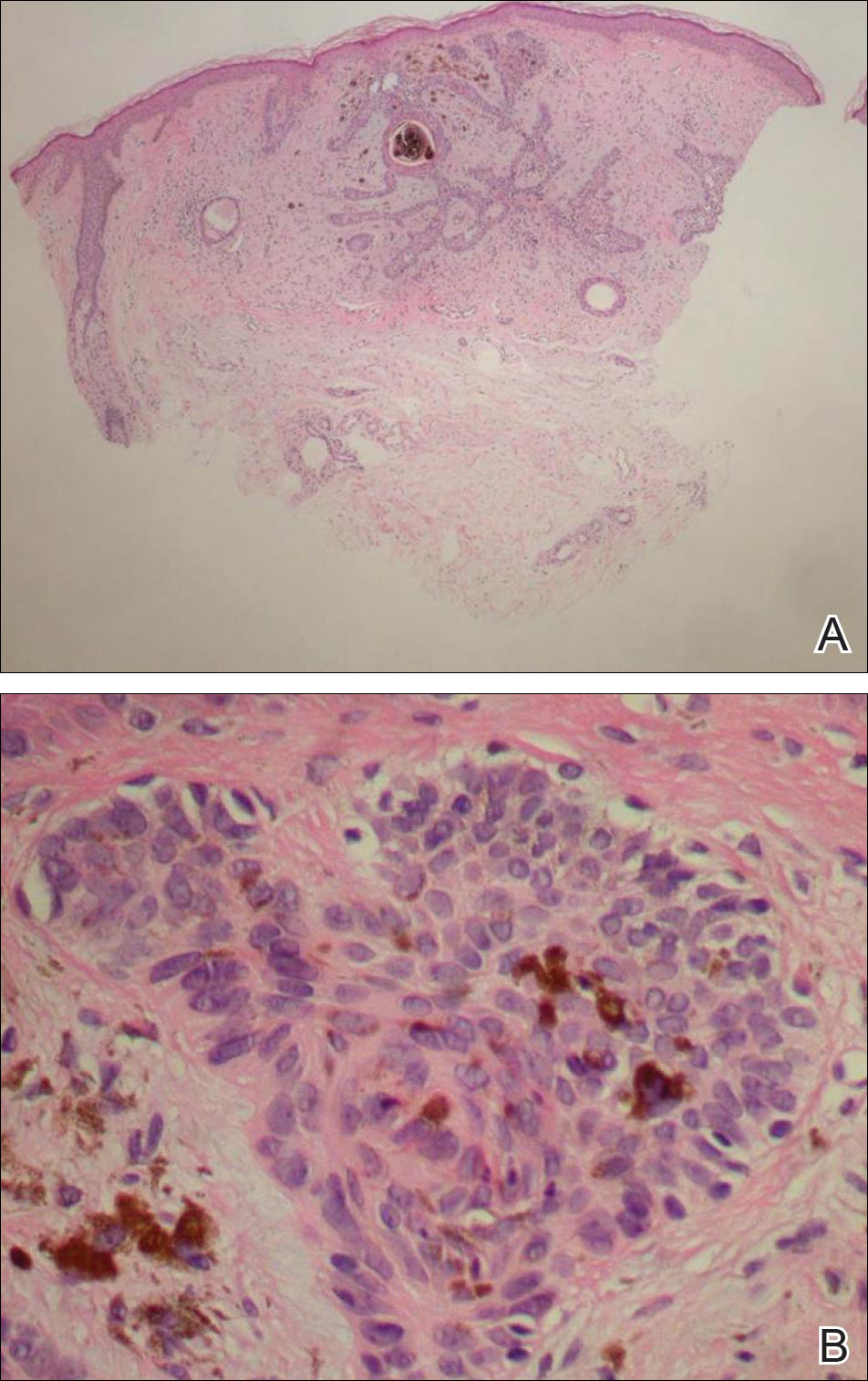

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

Linear Basal Cell Carcinoma

On examination, the lesion was suspected to be a nevocellular nevus, foreign body granuloma, or venous lake; however, a skin biopsy specimen from the lesion on the left wrist revealed a tumor mass of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading arrangement, and scattered pigment granules (Figure 1). Tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein staining. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The lesion was removed by simple excision with primary closure of the wound. The surgical margins were free of tumor cells. The lesion had not recurred at 6-month follow-up. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Basal cell carcinoma presents with diverse clinical features, and several morphologic and histologic variants have been reported.1 Linear BCC was described as a distinct clinical entity in 1985 by Lewis2 in a 73-year-old man with a 20-mm linear pigmented lesion on the left cheek. Linear BCC often is not recognized or categorized as such by clinicians, as some may think that linear BCC is not a distinct entity but rather is one of the diverse clinical features of BCC.3 Linear BCC is believed to have specific clinical and histologic features and can be regarded as a distinct entity.4 Mavrikakis et al5 objectively defined linear BCC as a lesion that appeared to extend preferentially in one direction, resulting in a lesion with relatively straight borders and a length much greater than the width (3:1 ratio). Our patient presented with a linearly curved lesion, which is a rare feature of BCC.

Linear BCC occurs in equal proportions in men and women aged 40 to 87 years. More than 92% of reported patients were older than 60 years.6 The most common site for linear BCC is the periocular area, with the majority of lesions occurring on the cheek or lower eyelid. The second most common site is the neck, followed by the trunk, lower face, and inguinal skin fold.3,5

The mechanism of linearity has been speculated. The majority of the reported cases of linear BCC have no history of trauma.7 However, focal trauma has been assumed to be a risk factor for the development of linear BCC, so the possibility that the Köbner phenomenon may be related to its linear pattern has been proposed.8 The Köbner phenomenon can be implicated in our case, as there was a history of surgery, which resulted in a scar.

Menzies9 described dermoscopic features of pigmented BCC and stated that the diagnosis of pigmented BCC required the presence of 1 or more of the following 6 positive features: large blue-gray ovoid nests; multiple blue-gray globules; maple leaf–like areas; spoke wheel areas; ulceration; and arborizing treelike vessels. In our case, there were multiple blue-gray globules and a streak that resembled ginseng (Figure 2).

Linear BCC is an uncommon morphological variant that requires clinical recognition. Our case was unique because of the ginsenglike streak on dermoscopy and possible association with a prior trauma.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.

- Sexton M, Jones DB, Maloney ME. Histologic pattern analysis of basal cell carcinoma. study of a series of 1,039 consecutive neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(6, pt 1):1118-1126.

- Lewis JE. Linear basal cell epithelioma. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:124-125.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Selva D, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:419-423.

- Jellouli A, Triki S, Zghal M, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:648-650.

- Mavrikakis I, Malhotra R, Barlow R, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: a distinct clinical entity in the periocular region [published online January 10, 2006]. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:338-342.

- Lim KK, Randle HW, Roenigk RK, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma: report of seventeen cases and review of the presentation and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:63-67.

- Iga N, Sakurai K, Fujii H, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma at the external genitalia. J Dermatol. 2014;41:275-276.

- Peschen M, Lo JS, Snow SN, et al. Linear basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1993;51:287-289.

- Menzies SW. Dermoscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Clin Dermatol. 2002;20:268-269.