User login

Glenoid Damage From Articular Protrusion of Metal Suture Anchor After Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

Complications with the use of anchor screws in shoulder surgery have been well-documented1,2 and can be divided into 3 categories: insertion (eg, incomplete seating, inadequate insertion, and migration), biologic (eg, large tacks producing synovitis and bone reaction), and, less commonly, mechanical (eg, intra- and extra-articular bone pull-out with migration) complications.

Prominent hardware, including suture anchors, as a cause of arthritis and joint damage has been well-documented in shoulder surgery.3,4 For example, anchors placed on the glenoid rim have been implicated in severe cartilage loss if they protrude above the level of the glenoid rim.3 However, to the authors’ knowledge, prominent anchor placement after rotator cuff repair has not been reported as a cause of arthritis unless the anchor dislodges into the glenohumeral joint. The authors present a case in which a suture anchor used for rotator cuff repair protruded through the humeral head, resulting in glenohumeral arthritis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented with complaints of persistent right shoulder pain for 5 months after a fall from a bicycle. She had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication without pain relief. On presentation, she had no atrophy or deformity, was neurologically intact for sensation and reflexes, and had full range of motion (ROM) but a painful arc. She had tenderness over the greater tuberosity and positive Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement signs. She had pain but no weakness to resisted abduction or to resisted external rotation with the arms at the sides.

Preoperative conventional radiographs of the shoulder were normal. A gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance arthrogram showed a high-grade articular partial tear of the supraspinatus, which was judged to be at least two-thirds of the tendon width. Because nonoperative methods had failed, the patient elected operative intervention for this tear.

Diagnostic arthroscopy (with the patient in a lateral decubitus position) showed a normal joint except for a high-grade, 8×8-mm, greater than 6 mm deep, partial tear of the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon. The subacromial space had moderate to severe bursal tissue inflammation but no full-thickness component to the rotator cuff tear. A bursectomy, coracoacromial ligament release, and partial anterolateral acromioplasty were performed.

A transtendinous technique was used to repair this high-grade tear. For an anatomically rigid repair, we used 3 suture anchors with a straight configuration because each metal anchor has only 1 suture. According to the standard arthroscopic transtendinous repair technique, the suture anchors were placed through the rotator cuff tendon (at the lateral articular margin at the medial extent of the footprint) after localization of the angle with a spinal needle. A shuttle relay was used to pass the sutures, and the knot was pulled into the subacromial space, cinching the rotator cuff on top of the suture anchors and reestablishing the contact of the tendon to the footprint. We used two 2.4-mm FASTak suture anchors (Arthrex, Naples, Florida) and one 3.5-mm Corkscrew suture anchor (Arthrex). This process was repeated for the remaining suture limbs. The placement of the suture anchors adequately reduced the articular part of the cuff to the footprint.

After surgery, the patient had no complications, and radiographs taken the next day suggested no abnormalities (Figure 1A). The shoulder was immobilized for 4 weeks after surgery, and passive, gentle ROM exercise was supervised by a physical therapist twice a week during this period. After the first 4 weeks, an active ROM program was begun. However, shortly after initiating motion in the shoulder, the patient complained of a recurrence of pain that she described as a sharp and grinding sensation.

The patient was reevaluated 8 weeks after surgery. Her pain was worsening, and she was having difficulty regaining ROM. Conventional radiographs showed the tip of the metal anchor protruding through the articular cartilage of the humeral head (Figure 1B). The patient was informed of the findings, and immediate surgery was performed to remove the anchor.

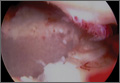

Arthroscopic examination showed extensive damage to the glenoid cartilage (Figure 1C) and an intra-articularly intact rotator cuff repair. The cartilage damage was located in the posterior and inferior half of the glenoid, which is related to the forward flexion of the arm; the depth of the cartilage defect was approximately 2 mm. Under the image intensifier, an empty suture anchor driver was inserted into the previous screw insertion hole, and the anchor was screwed back out and removed.

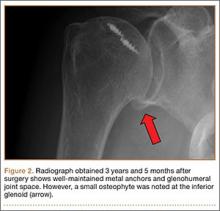

After surgery, the patient’s arm was placed in a sling, and an ROM program began 4 weeks later. The sensation of grinding was eliminated, and her pain gradually improved. Three years after surgery, she had no pain, no weakness, and full ROM without limitations (Figure 2).

Discussion

Protrusion and migration of suture anchors in shoulder surgery has been documented extensively.3,4 Zuckerman and Matsen4 divided these complications into 4 groups: (1) incorrect placement, (2) migration after placement, (3) loosening, and (4) device breakage. These complications may be frequently related to surgical technique, and all these studies describe backward migration of the anchor out of the drill hole. In the current case, the anchor tip penetrated the articular surface of the humeral head, not because of anchor migration but because the anchor was inserted too far. To the authors’ knowledge, there is only 1 reported case of anchor protrusion through the humeral head; it involved a different type of anchor insertion system.5 In that case, there was only mild cartilage damage to the glenoid, and the patient recovered after removal of the anchors.

Several factors contributed to the improper insertion of the anchor in the current patient. First, repairing a high-grade articular side defect or partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion lesion can be technically challenging because rotator cuff tissue obscures the view when inserting the anchor. Second, the anchor was inserted too medially on the greater tuberosity, which made the distance from the tuberosity to the joint shorter. Wong and colleagues5 performed an analysis of the angle of insertion that would be safe using a PEEK PushLock SP system (Arthrex), but they emphasized that the angle depends on the configuration of the particular insertion system. The current case also shows that the surgeon should be cognizant of the fact that penetration of the humeral head by the anchor can occur if the surgeon is unaware of the distance from the anchor to the laser line on the insertion device or of the distance from the tuberosity to the articular surface of the humeral head.

The current case also shows that the type of anchor and delivery system may contribute to this complication. Double-loaded suture anchors can decrease the number of anchors needed for secure fixation. Bioabsorbable anchors can be used for this purpose, but they may be technically more difficult to use for repairing partial tears of the rotator cuff. Better visualization of the laser line on the anchor may be facilitated by using a probe from an anterior portal to hold the cuff up while the anchor is inserted.

This case has shown the importance of obtaining postoperative radiographic studies in patients who have metal anchors placed during shoulder surgery, especially if they complain of continued pain, new pain, crepitus, or grinding. When conventional radiography is insufficient for locating the anchor or its proximity to the joint line, computed tomography can be helpful.1

Conclusion

Removing failed suture anchors can be challenging, especially when they protrude into the joint on the humeral side.1,6 The best way to prevent this complication is through careful technique. The anchors should not be inserted beyond the depth of the laser line on the anchors, and every attempt should be made to make sure the laser line is visible at the time of anchor insertion. Postoperative radiographs should be considered for patients with metal anchors in the shoulder, especially if the patient continues to have symptoms or develops new symptoms in the shoulder after surgery.

1. Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS, McFarland EG. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part II: The prevention and treatment of complications. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(1):136-144.

2. McFarland EG, Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part I: Biology and biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1918-1923.

3. Rhee YG, Lee DH, Chun IH, Bae SC. Glenohumeral arthropathy after arthroscopic anterior shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(4):402-406.

4. Zuckerman JD, Matsen FA III. Complications about the glenohumeral joint related to the use of screws and staples. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(2):175-180.

5. Wong AS, Kokkalis ZT, Schmidt CC. Proper insertion angle is essential to prevent intra-articular protrusion of a knotless suture anchor in shoulder rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):286-290.

6. Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Zikria BA, Dai Z, Petersen SA. Techniques for suture anchor removal in shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1706-1710.

Complications with the use of anchor screws in shoulder surgery have been well-documented1,2 and can be divided into 3 categories: insertion (eg, incomplete seating, inadequate insertion, and migration), biologic (eg, large tacks producing synovitis and bone reaction), and, less commonly, mechanical (eg, intra- and extra-articular bone pull-out with migration) complications.

Prominent hardware, including suture anchors, as a cause of arthritis and joint damage has been well-documented in shoulder surgery.3,4 For example, anchors placed on the glenoid rim have been implicated in severe cartilage loss if they protrude above the level of the glenoid rim.3 However, to the authors’ knowledge, prominent anchor placement after rotator cuff repair has not been reported as a cause of arthritis unless the anchor dislodges into the glenohumeral joint. The authors present a case in which a suture anchor used for rotator cuff repair protruded through the humeral head, resulting in glenohumeral arthritis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented with complaints of persistent right shoulder pain for 5 months after a fall from a bicycle. She had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication without pain relief. On presentation, she had no atrophy or deformity, was neurologically intact for sensation and reflexes, and had full range of motion (ROM) but a painful arc. She had tenderness over the greater tuberosity and positive Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement signs. She had pain but no weakness to resisted abduction or to resisted external rotation with the arms at the sides.

Preoperative conventional radiographs of the shoulder were normal. A gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance arthrogram showed a high-grade articular partial tear of the supraspinatus, which was judged to be at least two-thirds of the tendon width. Because nonoperative methods had failed, the patient elected operative intervention for this tear.

Diagnostic arthroscopy (with the patient in a lateral decubitus position) showed a normal joint except for a high-grade, 8×8-mm, greater than 6 mm deep, partial tear of the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon. The subacromial space had moderate to severe bursal tissue inflammation but no full-thickness component to the rotator cuff tear. A bursectomy, coracoacromial ligament release, and partial anterolateral acromioplasty were performed.

A transtendinous technique was used to repair this high-grade tear. For an anatomically rigid repair, we used 3 suture anchors with a straight configuration because each metal anchor has only 1 suture. According to the standard arthroscopic transtendinous repair technique, the suture anchors were placed through the rotator cuff tendon (at the lateral articular margin at the medial extent of the footprint) after localization of the angle with a spinal needle. A shuttle relay was used to pass the sutures, and the knot was pulled into the subacromial space, cinching the rotator cuff on top of the suture anchors and reestablishing the contact of the tendon to the footprint. We used two 2.4-mm FASTak suture anchors (Arthrex, Naples, Florida) and one 3.5-mm Corkscrew suture anchor (Arthrex). This process was repeated for the remaining suture limbs. The placement of the suture anchors adequately reduced the articular part of the cuff to the footprint.

After surgery, the patient had no complications, and radiographs taken the next day suggested no abnormalities (Figure 1A). The shoulder was immobilized for 4 weeks after surgery, and passive, gentle ROM exercise was supervised by a physical therapist twice a week during this period. After the first 4 weeks, an active ROM program was begun. However, shortly after initiating motion in the shoulder, the patient complained of a recurrence of pain that she described as a sharp and grinding sensation.

The patient was reevaluated 8 weeks after surgery. Her pain was worsening, and she was having difficulty regaining ROM. Conventional radiographs showed the tip of the metal anchor protruding through the articular cartilage of the humeral head (Figure 1B). The patient was informed of the findings, and immediate surgery was performed to remove the anchor.

Arthroscopic examination showed extensive damage to the glenoid cartilage (Figure 1C) and an intra-articularly intact rotator cuff repair. The cartilage damage was located in the posterior and inferior half of the glenoid, which is related to the forward flexion of the arm; the depth of the cartilage defect was approximately 2 mm. Under the image intensifier, an empty suture anchor driver was inserted into the previous screw insertion hole, and the anchor was screwed back out and removed.

After surgery, the patient’s arm was placed in a sling, and an ROM program began 4 weeks later. The sensation of grinding was eliminated, and her pain gradually improved. Three years after surgery, she had no pain, no weakness, and full ROM without limitations (Figure 2).

Discussion

Protrusion and migration of suture anchors in shoulder surgery has been documented extensively.3,4 Zuckerman and Matsen4 divided these complications into 4 groups: (1) incorrect placement, (2) migration after placement, (3) loosening, and (4) device breakage. These complications may be frequently related to surgical technique, and all these studies describe backward migration of the anchor out of the drill hole. In the current case, the anchor tip penetrated the articular surface of the humeral head, not because of anchor migration but because the anchor was inserted too far. To the authors’ knowledge, there is only 1 reported case of anchor protrusion through the humeral head; it involved a different type of anchor insertion system.5 In that case, there was only mild cartilage damage to the glenoid, and the patient recovered after removal of the anchors.

Several factors contributed to the improper insertion of the anchor in the current patient. First, repairing a high-grade articular side defect or partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion lesion can be technically challenging because rotator cuff tissue obscures the view when inserting the anchor. Second, the anchor was inserted too medially on the greater tuberosity, which made the distance from the tuberosity to the joint shorter. Wong and colleagues5 performed an analysis of the angle of insertion that would be safe using a PEEK PushLock SP system (Arthrex), but they emphasized that the angle depends on the configuration of the particular insertion system. The current case also shows that the surgeon should be cognizant of the fact that penetration of the humeral head by the anchor can occur if the surgeon is unaware of the distance from the anchor to the laser line on the insertion device or of the distance from the tuberosity to the articular surface of the humeral head.

The current case also shows that the type of anchor and delivery system may contribute to this complication. Double-loaded suture anchors can decrease the number of anchors needed for secure fixation. Bioabsorbable anchors can be used for this purpose, but they may be technically more difficult to use for repairing partial tears of the rotator cuff. Better visualization of the laser line on the anchor may be facilitated by using a probe from an anterior portal to hold the cuff up while the anchor is inserted.

This case has shown the importance of obtaining postoperative radiographic studies in patients who have metal anchors placed during shoulder surgery, especially if they complain of continued pain, new pain, crepitus, or grinding. When conventional radiography is insufficient for locating the anchor or its proximity to the joint line, computed tomography can be helpful.1

Conclusion

Removing failed suture anchors can be challenging, especially when they protrude into the joint on the humeral side.1,6 The best way to prevent this complication is through careful technique. The anchors should not be inserted beyond the depth of the laser line on the anchors, and every attempt should be made to make sure the laser line is visible at the time of anchor insertion. Postoperative radiographs should be considered for patients with metal anchors in the shoulder, especially if the patient continues to have symptoms or develops new symptoms in the shoulder after surgery.

Complications with the use of anchor screws in shoulder surgery have been well-documented1,2 and can be divided into 3 categories: insertion (eg, incomplete seating, inadequate insertion, and migration), biologic (eg, large tacks producing synovitis and bone reaction), and, less commonly, mechanical (eg, intra- and extra-articular bone pull-out with migration) complications.

Prominent hardware, including suture anchors, as a cause of arthritis and joint damage has been well-documented in shoulder surgery.3,4 For example, anchors placed on the glenoid rim have been implicated in severe cartilage loss if they protrude above the level of the glenoid rim.3 However, to the authors’ knowledge, prominent anchor placement after rotator cuff repair has not been reported as a cause of arthritis unless the anchor dislodges into the glenohumeral joint. The authors present a case in which a suture anchor used for rotator cuff repair protruded through the humeral head, resulting in glenohumeral arthritis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 61-year-old woman presented with complaints of persistent right shoulder pain for 5 months after a fall from a bicycle. She had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication without pain relief. On presentation, she had no atrophy or deformity, was neurologically intact for sensation and reflexes, and had full range of motion (ROM) but a painful arc. She had tenderness over the greater tuberosity and positive Neer and Hawkins-Kennedy impingement signs. She had pain but no weakness to resisted abduction or to resisted external rotation with the arms at the sides.

Preoperative conventional radiographs of the shoulder were normal. A gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance arthrogram showed a high-grade articular partial tear of the supraspinatus, which was judged to be at least two-thirds of the tendon width. Because nonoperative methods had failed, the patient elected operative intervention for this tear.

Diagnostic arthroscopy (with the patient in a lateral decubitus position) showed a normal joint except for a high-grade, 8×8-mm, greater than 6 mm deep, partial tear of the articular side of the supraspinatus tendon. The subacromial space had moderate to severe bursal tissue inflammation but no full-thickness component to the rotator cuff tear. A bursectomy, coracoacromial ligament release, and partial anterolateral acromioplasty were performed.

A transtendinous technique was used to repair this high-grade tear. For an anatomically rigid repair, we used 3 suture anchors with a straight configuration because each metal anchor has only 1 suture. According to the standard arthroscopic transtendinous repair technique, the suture anchors were placed through the rotator cuff tendon (at the lateral articular margin at the medial extent of the footprint) after localization of the angle with a spinal needle. A shuttle relay was used to pass the sutures, and the knot was pulled into the subacromial space, cinching the rotator cuff on top of the suture anchors and reestablishing the contact of the tendon to the footprint. We used two 2.4-mm FASTak suture anchors (Arthrex, Naples, Florida) and one 3.5-mm Corkscrew suture anchor (Arthrex). This process was repeated for the remaining suture limbs. The placement of the suture anchors adequately reduced the articular part of the cuff to the footprint.

After surgery, the patient had no complications, and radiographs taken the next day suggested no abnormalities (Figure 1A). The shoulder was immobilized for 4 weeks after surgery, and passive, gentle ROM exercise was supervised by a physical therapist twice a week during this period. After the first 4 weeks, an active ROM program was begun. However, shortly after initiating motion in the shoulder, the patient complained of a recurrence of pain that she described as a sharp and grinding sensation.

The patient was reevaluated 8 weeks after surgery. Her pain was worsening, and she was having difficulty regaining ROM. Conventional radiographs showed the tip of the metal anchor protruding through the articular cartilage of the humeral head (Figure 1B). The patient was informed of the findings, and immediate surgery was performed to remove the anchor.

Arthroscopic examination showed extensive damage to the glenoid cartilage (Figure 1C) and an intra-articularly intact rotator cuff repair. The cartilage damage was located in the posterior and inferior half of the glenoid, which is related to the forward flexion of the arm; the depth of the cartilage defect was approximately 2 mm. Under the image intensifier, an empty suture anchor driver was inserted into the previous screw insertion hole, and the anchor was screwed back out and removed.

After surgery, the patient’s arm was placed in a sling, and an ROM program began 4 weeks later. The sensation of grinding was eliminated, and her pain gradually improved. Three years after surgery, she had no pain, no weakness, and full ROM without limitations (Figure 2).

Discussion

Protrusion and migration of suture anchors in shoulder surgery has been documented extensively.3,4 Zuckerman and Matsen4 divided these complications into 4 groups: (1) incorrect placement, (2) migration after placement, (3) loosening, and (4) device breakage. These complications may be frequently related to surgical technique, and all these studies describe backward migration of the anchor out of the drill hole. In the current case, the anchor tip penetrated the articular surface of the humeral head, not because of anchor migration but because the anchor was inserted too far. To the authors’ knowledge, there is only 1 reported case of anchor protrusion through the humeral head; it involved a different type of anchor insertion system.5 In that case, there was only mild cartilage damage to the glenoid, and the patient recovered after removal of the anchors.

Several factors contributed to the improper insertion of the anchor in the current patient. First, repairing a high-grade articular side defect or partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion lesion can be technically challenging because rotator cuff tissue obscures the view when inserting the anchor. Second, the anchor was inserted too medially on the greater tuberosity, which made the distance from the tuberosity to the joint shorter. Wong and colleagues5 performed an analysis of the angle of insertion that would be safe using a PEEK PushLock SP system (Arthrex), but they emphasized that the angle depends on the configuration of the particular insertion system. The current case also shows that the surgeon should be cognizant of the fact that penetration of the humeral head by the anchor can occur if the surgeon is unaware of the distance from the anchor to the laser line on the insertion device or of the distance from the tuberosity to the articular surface of the humeral head.

The current case also shows that the type of anchor and delivery system may contribute to this complication. Double-loaded suture anchors can decrease the number of anchors needed for secure fixation. Bioabsorbable anchors can be used for this purpose, but they may be technically more difficult to use for repairing partial tears of the rotator cuff. Better visualization of the laser line on the anchor may be facilitated by using a probe from an anterior portal to hold the cuff up while the anchor is inserted.

This case has shown the importance of obtaining postoperative radiographic studies in patients who have metal anchors placed during shoulder surgery, especially if they complain of continued pain, new pain, crepitus, or grinding. When conventional radiography is insufficient for locating the anchor or its proximity to the joint line, computed tomography can be helpful.1

Conclusion

Removing failed suture anchors can be challenging, especially when they protrude into the joint on the humeral side.1,6 The best way to prevent this complication is through careful technique. The anchors should not be inserted beyond the depth of the laser line on the anchors, and every attempt should be made to make sure the laser line is visible at the time of anchor insertion. Postoperative radiographs should be considered for patients with metal anchors in the shoulder, especially if the patient continues to have symptoms or develops new symptoms in the shoulder after surgery.

1. Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS, McFarland EG. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part II: The prevention and treatment of complications. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(1):136-144.

2. McFarland EG, Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part I: Biology and biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1918-1923.

3. Rhee YG, Lee DH, Chun IH, Bae SC. Glenohumeral arthropathy after arthroscopic anterior shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(4):402-406.

4. Zuckerman JD, Matsen FA III. Complications about the glenohumeral joint related to the use of screws and staples. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(2):175-180.

5. Wong AS, Kokkalis ZT, Schmidt CC. Proper insertion angle is essential to prevent intra-articular protrusion of a knotless suture anchor in shoulder rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):286-290.

6. Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Zikria BA, Dai Z, Petersen SA. Techniques for suture anchor removal in shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1706-1710.

1. Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS, McFarland EG. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part II: The prevention and treatment of complications. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(1):136-144.

2. McFarland EG, Park HB, Keyurapan E, Gill HS, Selhi HS. Suture anchors and tacks for shoulder surgery. Part I: Biology and biomechanics. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1918-1923.

3. Rhee YG, Lee DH, Chun IH, Bae SC. Glenohumeral arthropathy after arthroscopic anterior shoulder stabilization. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(4):402-406.

4. Zuckerman JD, Matsen FA III. Complications about the glenohumeral joint related to the use of screws and staples. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(2):175-180.

5. Wong AS, Kokkalis ZT, Schmidt CC. Proper insertion angle is essential to prevent intra-articular protrusion of a knotless suture anchor in shoulder rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(2):286-290.

6. Grutter PW, McFarland EG, Zikria BA, Dai Z, Petersen SA. Techniques for suture anchor removal in shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1706-1710.