User login

“I Want What Kobe Had”: A Comprehensive Guide to Giving Your Patients the Biologic Solutions They Crave

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

The sun has finally set on Kobe Bryant’s magnificent career. After all the tributes and tearful goodbyes, he has finally played his last game and become a part of basketball history. Ever since his field trip to Germany for interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein (IRAP) treatments to his knee, and his subsequent return to high-level play, I’ve been under siege in the office by patients who “want what Kobe had.” I’ve had to explain, time and time again, that IRAP treatment is not available in the United States and that platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is the closest alternative treatment, convince them that PRP may be even better, and then let them know that it’s considered experimental and not covered by insurance.

In the last issue, we discussed the future of orthopedics, which in my opinion will rely heavily on the biologic therapies now considered experimental. In this issue, we will look into our crystal balls and imagine what that future might look like. To do so, we should first consider what we hope to accomplish through the incorporation of biologic therapies.

The regeneration of articular cartilage, acceleration of fracture and tissue healing, and faster incorporation of tendon grafts to bone have long been considered the Holy Grail of Orthopedics. In his best seller, The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown makes a compelling argument that the Holy Grail, the chalice thought to have held the blood of Christ, was in fact a mistranslated reference to his living descendants. Whenever I have a visitor or student in the operating room, I focus the scope on the synovial capillaries so they can see the individual red blood cells passing single-file through the vessels on their way to supply cells with the nutrients they need.

Perhaps, like in The Da Vinci Code, the solution to our greatest biologic challenges lies in the blood, already there, just waiting to be unlocked.

PRP has been utilized for everything from tendinopathy to arthropathy, with varied results in the literature. The lack of standardization of PRP preparations, which vary in inclusion of white cells and absolute platelet count, confounds these results even further. In this issue, we review its use in sports medicine and knee arthritis, taking a closer look at partial ulnar collateral ligament tears in baseball players.

In “Tips of the Trade,” we present a technique for “superior capsular reconstruction” that provides a novel solution for patients with pseudoparalysis from massive rotator cuff tears with little other options beside reverse total shoulder arthroplasty.

The one absolute statement I can make regarding biologics is that we currently have more questions than answers, and every hypothesis we prove simply begets more questions. More randomized controlled studies are needed in virtually every aspect of biologics, and we should all consider taking part. While the solutions our patients crave may not arrive during our careers, or even our lifetimes, the groundwork we do now will set the stage for future generations to enjoy biologically enhanced outcomes.

Stem-Based Repair of the Subscapularis in Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

Subscapularis integrity following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is important to maintaining glenohumeral joint stability and functional outcome. In recent years increased emphasis has been placed on the management of the subscapularis during TSA. Options for management of the subscapularis during TSA include tenotomy, release of the tendon from the bone (peel technique), or a lesser tuberosity osteotomy (LTO). Several studies have demonstrated that subscapularis integrity is often impaired with a traditional tenotomy approach.1,2 Based on these studies, a subscapularis peel or LTO approach have gained popularity.3 This technical article describes a subscapularis peel repair technique that is integrated into a press-fit anatomical short-stem during TSA.

Technique

The repair technique demonstrated in this article features the Univers Apex (Arthrex) humeral stem, but it can be adapted to other stems with features that allow for the incorporation of sutures.

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to gain access to the shoulder. The biceps tendon is released or tenotomized to gain access to the bicipital groove. The rotator interval is then opened beginning at the superior subscapularis by following the course of the anterior side of the proximal biceps and then directing the release toward the base of the coracoid in order to protect the supraspinatus tendon. Next, the subscapularis is sharply released from the lesser tuberosity. The tendon and capsule are released as a unit and a 3-sided release of the subscapularis is performed.

The humeral canal is opened with a reamer and broached to accommodate an appropriately sized press-fit component. A polyethylene glenoid component is placed and then attention is returned to the humerus.

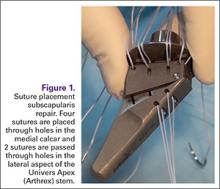

Prior to placement of the humeral stem, 6 No. 2 or No. 5 FiberWire (Arthrex) sutures are pre-placed through suture holes in the stem (Figure 1). Four sutures are passed by hand through the medial calcar component and 2 sutures are placed through holes in the lateral portion of the stem. A 2.0-mm or 2.5-mm drill is used to create 2 holes in the bicipital groove: 1 at the superior aspect of the lesser tuberosity, and 1 at the inferior aspect of the lesser tuberosity (Figure 2A). Prior to impacting the stem, the 4 lateral suture limbs (limbs A through D) are shuttled through the holes in the bicipital groove (Figure 2B). Then the stem is impacted and secured, the final humeral head is placed, the joint is reduced, and the subscapularis is repaired (Figure 2C).

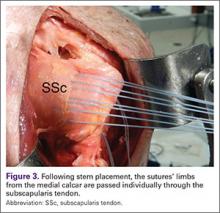

The 4 sutures passing through the medial calcar of the stem result in 8 suture limbs (limbs 1 through 8). Each limb is separately passed through the subscapularis tendon with a free needle, moving obliquely from inferior-medial to superior-lateral (Figure 3). Note: A variation is to pass 2 suture limbs at a time, but this technique has not been biomechanically investigated at the time of this writing.

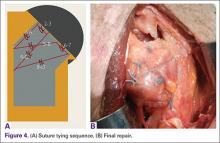

Prior to tying the sutures, it is helpful to place a stitch between the superolateral corner of the subscapularis and the anterior supraspinatus in order to facilitate reduction. The suture limbs are then tied with a specific sequence to create a suture-bridging construct with 2 additional medial mattress sutures as follows (Figures 4A, 4B):

1 to A

4 to C

5 to B

8 to D

2 to 3

6 to 7

In this technique, each suture limb is tied to a limb from another suture. When the last 2 pairs are tied (2 to 3 and 6 to 7), they are tensioned to remove any slack from the repair and equalize tension within all suture pairs. After the sutures are tied, the rotator interval may be closed with simple sutures if desired. The patient is immobilized in a sling for 4 to 6 weeks. Immediate passive forward flexion is allowed as well as external rotation to 30°. Strengthening is initiated at 8 weeks.

Discussion

The incidence of TSA has increased dramatically in the last decade and is projected to continue in the coming years.4 In the majority of cases, TSA leads to improvement in pain and function. However, failures continue to exist. In addition to glenoid loosening, prosthetic instability and rotator cuff insufficiency are the most common causes of failure.5 The latter 2 are intimately related since glenohumeral stability depends largely upon the rotator cuff. Therefore, optimization of outcome following TSA depends largely upon maintaining integrity of the rotator cuff. While the incidence of preoperative rotator cuff tears and fatty degeneration of the rotator are not modifiable, the management of the subscapularis is in the hands of the surgeon.

While subscapularis tenotomy has historically been used to access the glenohumeral joint during TSA, this approach is associated with an alarmingly high failure rate. Jackson and colleagues1 reported that 7 out of 15 (47%) of subscapularis tendons managed with tenotomy during TSA were completely torn on postoperative ultrasound. The patients with postoperative rupture had decreased internal rotation strength and DASH scores (4.6 intact vs. 25 ruptured; P = .04) compared to the patients with an intact tendon. Scalise and colleagues2 retrospectively compared a tenotomy approach to a LTO. They reported that 7 out of 15 subscapularis tenotomies were ruptured or attenuated postoperatively. By comparison, 18 out of 20 LTOs were healed. Regardless of approach, functional outcome was higher at 1 year postoperative when the subscapularis was intact.

The high failure rate with tendon-to-tendon healing following tenotomy has led to interest in a subscapularis peel to achieve tendon-to-bone healing or an LTO approach to achieve bone-to-bone healing. Lapner and colleagues3 compared a peel to an LTO in a randomized controlled trial of 87 patients. At 2 years postoperative, there was no difference in functional outcome between the 2 groups.

While both a peel and an LTO approach can be repaired with the technique described in this article, there are advantages to a peel approach. First, a peel approach may be considered more reproducible, particularly for surgeons who do a limited amount of shoulder arthroplasty. Whereas an LTO can vary in size, the subscapularis can nearly always be reproducibly peeled from the lesser tuberosity. Second, this technique uses a short stem, which relies upon proximal fixation. While this approach is bone-preserving, a large osteotomy has the potential to compromise fixation of the stem. Therefore, while one of us (PJD) uses a fleck LTO with a short stem, we advise a peel technique in most cases.

In summary, the subscapularis repair technique described here provides a reproducible and biomechanically sound approach to managing the subscapularis during TSA.

1. Jackson JD, Cil A, Smith J, Steinmann SP. Integrity and function of the subscapularis after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(7):1085-1090.

2. Scalise JJ, Ciccone J, Iannotti JP. Clinical, radiographic, and ultrasonographic comparison of subscapularis tenotomy and lesser tuberosity osteotomy for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(7):1627-1634.

3. Lapner PL, Sabri E, Rakhra K, Bell K, Athwal GS. Comparison of lesser tuberosity osteotomy to subscapularis peel in shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2239-2246.

4. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

5. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Shoulder Arthroplasty 2015 Annual Report. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/217645/Shoulder%20Arthroplasty. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Subscapularis integrity following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is important to maintaining glenohumeral joint stability and functional outcome. In recent years increased emphasis has been placed on the management of the subscapularis during TSA. Options for management of the subscapularis during TSA include tenotomy, release of the tendon from the bone (peel technique), or a lesser tuberosity osteotomy (LTO). Several studies have demonstrated that subscapularis integrity is often impaired with a traditional tenotomy approach.1,2 Based on these studies, a subscapularis peel or LTO approach have gained popularity.3 This technical article describes a subscapularis peel repair technique that is integrated into a press-fit anatomical short-stem during TSA.

Technique

The repair technique demonstrated in this article features the Univers Apex (Arthrex) humeral stem, but it can be adapted to other stems with features that allow for the incorporation of sutures.

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to gain access to the shoulder. The biceps tendon is released or tenotomized to gain access to the bicipital groove. The rotator interval is then opened beginning at the superior subscapularis by following the course of the anterior side of the proximal biceps and then directing the release toward the base of the coracoid in order to protect the supraspinatus tendon. Next, the subscapularis is sharply released from the lesser tuberosity. The tendon and capsule are released as a unit and a 3-sided release of the subscapularis is performed.

The humeral canal is opened with a reamer and broached to accommodate an appropriately sized press-fit component. A polyethylene glenoid component is placed and then attention is returned to the humerus.

Prior to placement of the humeral stem, 6 No. 2 or No. 5 FiberWire (Arthrex) sutures are pre-placed through suture holes in the stem (Figure 1). Four sutures are passed by hand through the medial calcar component and 2 sutures are placed through holes in the lateral portion of the stem. A 2.0-mm or 2.5-mm drill is used to create 2 holes in the bicipital groove: 1 at the superior aspect of the lesser tuberosity, and 1 at the inferior aspect of the lesser tuberosity (Figure 2A). Prior to impacting the stem, the 4 lateral suture limbs (limbs A through D) are shuttled through the holes in the bicipital groove (Figure 2B). Then the stem is impacted and secured, the final humeral head is placed, the joint is reduced, and the subscapularis is repaired (Figure 2C).

The 4 sutures passing through the medial calcar of the stem result in 8 suture limbs (limbs 1 through 8). Each limb is separately passed through the subscapularis tendon with a free needle, moving obliquely from inferior-medial to superior-lateral (Figure 3). Note: A variation is to pass 2 suture limbs at a time, but this technique has not been biomechanically investigated at the time of this writing.

Prior to tying the sutures, it is helpful to place a stitch between the superolateral corner of the subscapularis and the anterior supraspinatus in order to facilitate reduction. The suture limbs are then tied with a specific sequence to create a suture-bridging construct with 2 additional medial mattress sutures as follows (Figures 4A, 4B):

1 to A

4 to C

5 to B

8 to D

2 to 3

6 to 7

In this technique, each suture limb is tied to a limb from another suture. When the last 2 pairs are tied (2 to 3 and 6 to 7), they are tensioned to remove any slack from the repair and equalize tension within all suture pairs. After the sutures are tied, the rotator interval may be closed with simple sutures if desired. The patient is immobilized in a sling for 4 to 6 weeks. Immediate passive forward flexion is allowed as well as external rotation to 30°. Strengthening is initiated at 8 weeks.

Discussion

The incidence of TSA has increased dramatically in the last decade and is projected to continue in the coming years.4 In the majority of cases, TSA leads to improvement in pain and function. However, failures continue to exist. In addition to glenoid loosening, prosthetic instability and rotator cuff insufficiency are the most common causes of failure.5 The latter 2 are intimately related since glenohumeral stability depends largely upon the rotator cuff. Therefore, optimization of outcome following TSA depends largely upon maintaining integrity of the rotator cuff. While the incidence of preoperative rotator cuff tears and fatty degeneration of the rotator are not modifiable, the management of the subscapularis is in the hands of the surgeon.

While subscapularis tenotomy has historically been used to access the glenohumeral joint during TSA, this approach is associated with an alarmingly high failure rate. Jackson and colleagues1 reported that 7 out of 15 (47%) of subscapularis tendons managed with tenotomy during TSA were completely torn on postoperative ultrasound. The patients with postoperative rupture had decreased internal rotation strength and DASH scores (4.6 intact vs. 25 ruptured; P = .04) compared to the patients with an intact tendon. Scalise and colleagues2 retrospectively compared a tenotomy approach to a LTO. They reported that 7 out of 15 subscapularis tenotomies were ruptured or attenuated postoperatively. By comparison, 18 out of 20 LTOs were healed. Regardless of approach, functional outcome was higher at 1 year postoperative when the subscapularis was intact.

The high failure rate with tendon-to-tendon healing following tenotomy has led to interest in a subscapularis peel to achieve tendon-to-bone healing or an LTO approach to achieve bone-to-bone healing. Lapner and colleagues3 compared a peel to an LTO in a randomized controlled trial of 87 patients. At 2 years postoperative, there was no difference in functional outcome between the 2 groups.

While both a peel and an LTO approach can be repaired with the technique described in this article, there are advantages to a peel approach. First, a peel approach may be considered more reproducible, particularly for surgeons who do a limited amount of shoulder arthroplasty. Whereas an LTO can vary in size, the subscapularis can nearly always be reproducibly peeled from the lesser tuberosity. Second, this technique uses a short stem, which relies upon proximal fixation. While this approach is bone-preserving, a large osteotomy has the potential to compromise fixation of the stem. Therefore, while one of us (PJD) uses a fleck LTO with a short stem, we advise a peel technique in most cases.

In summary, the subscapularis repair technique described here provides a reproducible and biomechanically sound approach to managing the subscapularis during TSA.

Subscapularis integrity following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) is important to maintaining glenohumeral joint stability and functional outcome. In recent years increased emphasis has been placed on the management of the subscapularis during TSA. Options for management of the subscapularis during TSA include tenotomy, release of the tendon from the bone (peel technique), or a lesser tuberosity osteotomy (LTO). Several studies have demonstrated that subscapularis integrity is often impaired with a traditional tenotomy approach.1,2 Based on these studies, a subscapularis peel or LTO approach have gained popularity.3 This technical article describes a subscapularis peel repair technique that is integrated into a press-fit anatomical short-stem during TSA.

Technique

The repair technique demonstrated in this article features the Univers Apex (Arthrex) humeral stem, but it can be adapted to other stems with features that allow for the incorporation of sutures.

A standard deltopectoral approach is used to gain access to the shoulder. The biceps tendon is released or tenotomized to gain access to the bicipital groove. The rotator interval is then opened beginning at the superior subscapularis by following the course of the anterior side of the proximal biceps and then directing the release toward the base of the coracoid in order to protect the supraspinatus tendon. Next, the subscapularis is sharply released from the lesser tuberosity. The tendon and capsule are released as a unit and a 3-sided release of the subscapularis is performed.

The humeral canal is opened with a reamer and broached to accommodate an appropriately sized press-fit component. A polyethylene glenoid component is placed and then attention is returned to the humerus.

Prior to placement of the humeral stem, 6 No. 2 or No. 5 FiberWire (Arthrex) sutures are pre-placed through suture holes in the stem (Figure 1). Four sutures are passed by hand through the medial calcar component and 2 sutures are placed through holes in the lateral portion of the stem. A 2.0-mm or 2.5-mm drill is used to create 2 holes in the bicipital groove: 1 at the superior aspect of the lesser tuberosity, and 1 at the inferior aspect of the lesser tuberosity (Figure 2A). Prior to impacting the stem, the 4 lateral suture limbs (limbs A through D) are shuttled through the holes in the bicipital groove (Figure 2B). Then the stem is impacted and secured, the final humeral head is placed, the joint is reduced, and the subscapularis is repaired (Figure 2C).

The 4 sutures passing through the medial calcar of the stem result in 8 suture limbs (limbs 1 through 8). Each limb is separately passed through the subscapularis tendon with a free needle, moving obliquely from inferior-medial to superior-lateral (Figure 3). Note: A variation is to pass 2 suture limbs at a time, but this technique has not been biomechanically investigated at the time of this writing.

Prior to tying the sutures, it is helpful to place a stitch between the superolateral corner of the subscapularis and the anterior supraspinatus in order to facilitate reduction. The suture limbs are then tied with a specific sequence to create a suture-bridging construct with 2 additional medial mattress sutures as follows (Figures 4A, 4B):

1 to A

4 to C

5 to B

8 to D

2 to 3

6 to 7

In this technique, each suture limb is tied to a limb from another suture. When the last 2 pairs are tied (2 to 3 and 6 to 7), they are tensioned to remove any slack from the repair and equalize tension within all suture pairs. After the sutures are tied, the rotator interval may be closed with simple sutures if desired. The patient is immobilized in a sling for 4 to 6 weeks. Immediate passive forward flexion is allowed as well as external rotation to 30°. Strengthening is initiated at 8 weeks.

Discussion

The incidence of TSA has increased dramatically in the last decade and is projected to continue in the coming years.4 In the majority of cases, TSA leads to improvement in pain and function. However, failures continue to exist. In addition to glenoid loosening, prosthetic instability and rotator cuff insufficiency are the most common causes of failure.5 The latter 2 are intimately related since glenohumeral stability depends largely upon the rotator cuff. Therefore, optimization of outcome following TSA depends largely upon maintaining integrity of the rotator cuff. While the incidence of preoperative rotator cuff tears and fatty degeneration of the rotator are not modifiable, the management of the subscapularis is in the hands of the surgeon.

While subscapularis tenotomy has historically been used to access the glenohumeral joint during TSA, this approach is associated with an alarmingly high failure rate. Jackson and colleagues1 reported that 7 out of 15 (47%) of subscapularis tendons managed with tenotomy during TSA were completely torn on postoperative ultrasound. The patients with postoperative rupture had decreased internal rotation strength and DASH scores (4.6 intact vs. 25 ruptured; P = .04) compared to the patients with an intact tendon. Scalise and colleagues2 retrospectively compared a tenotomy approach to a LTO. They reported that 7 out of 15 subscapularis tenotomies were ruptured or attenuated postoperatively. By comparison, 18 out of 20 LTOs were healed. Regardless of approach, functional outcome was higher at 1 year postoperative when the subscapularis was intact.

The high failure rate with tendon-to-tendon healing following tenotomy has led to interest in a subscapularis peel to achieve tendon-to-bone healing or an LTO approach to achieve bone-to-bone healing. Lapner and colleagues3 compared a peel to an LTO in a randomized controlled trial of 87 patients. At 2 years postoperative, there was no difference in functional outcome between the 2 groups.

While both a peel and an LTO approach can be repaired with the technique described in this article, there are advantages to a peel approach. First, a peel approach may be considered more reproducible, particularly for surgeons who do a limited amount of shoulder arthroplasty. Whereas an LTO can vary in size, the subscapularis can nearly always be reproducibly peeled from the lesser tuberosity. Second, this technique uses a short stem, which relies upon proximal fixation. While this approach is bone-preserving, a large osteotomy has the potential to compromise fixation of the stem. Therefore, while one of us (PJD) uses a fleck LTO with a short stem, we advise a peel technique in most cases.

In summary, the subscapularis repair technique described here provides a reproducible and biomechanically sound approach to managing the subscapularis during TSA.

1. Jackson JD, Cil A, Smith J, Steinmann SP. Integrity and function of the subscapularis after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(7):1085-1090.

2. Scalise JJ, Ciccone J, Iannotti JP. Clinical, radiographic, and ultrasonographic comparison of subscapularis tenotomy and lesser tuberosity osteotomy for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(7):1627-1634.

3. Lapner PL, Sabri E, Rakhra K, Bell K, Athwal GS. Comparison of lesser tuberosity osteotomy to subscapularis peel in shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2239-2246.

4. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

5. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Shoulder Arthroplasty 2015 Annual Report. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/217645/Shoulder%20Arthroplasty. Accessed April 7, 2016.

1. Jackson JD, Cil A, Smith J, Steinmann SP. Integrity and function of the subscapularis after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(7):1085-1090.

2. Scalise JJ, Ciccone J, Iannotti JP. Clinical, radiographic, and ultrasonographic comparison of subscapularis tenotomy and lesser tuberosity osteotomy for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(7):1627-1634.

3. Lapner PL, Sabri E, Rakhra K, Bell K, Athwal GS. Comparison of lesser tuberosity osteotomy to subscapularis peel in shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(24):2239-2246.

4. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

5. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Shoulder Arthroplasty 2015 Annual Report. https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/documents/10180/217645/Shoulder%20Arthroplasty. Accessed April 7, 2016.

Transitions (The Future of Orthopedics)

A transition is underway at AJO. As we discuss the future of the “new journal,” I often think about the future of orthopedics. I’ve decided my vision of the future is centered on 3 components. First, there will be a change in our training paradigm from an apprenticeship model to standardized training, where core competencies must be demonstrated for certification. Second, robots and computers will improve our diagnostic accuracy and will allow us to perform surgery with improved component positioning, while biologics and genetic analysis will accelerate nature’s ability to heal, and perhaps regenerate, injured tissue. Finally, computerized algorithms and technologically improved surgical outcomes will allow us to deliver high-quality healthcare at a lower cost, producing the value our current health systems are striving for, and leveling the playing field between high-volume centers and rural institutions forced to offer complete service lines.

In this issue, we examine robotic-assisted arthroplasty and its role in modern healthcare. I think the best argument for robots in the operating room might come from the airline industry. I’m sitting on a plane as I write this, without once thinking about how much experience my pilot has in the cockpit. I know our pilot has demonstrated the core competencies required to safely operate the plane, trained on emergency simulations, and logged the necessary hours before being handed the controls. I also know that the instrumentation is so good that the plane can essentially fly itself, making pilot skill and experience less relevant. In short, technology has, in all but rare circumstances, made our pilots virtually interchangeable.

Unfortunately, none of the above is true in orthopedics. Our residents are not required to demonstrate their skills before any licensing authority, simulator training is not available in all programs, and we’ve limited resident work hours. Yet it’s that same interchangeability that most healthcare models assume. No one argues that high-volume centers have better results when it comes to arthroplasty, but only a small percentage of total joints are currently performed at these centers. Surgeon training remains a virtual apprenticeship, lacking standardization, and resulting in a wide variation in skill and experience. Surgical residencies are not awarded based on dexterity, and work hour restrictions, Relative Value Unit-based academic contracts, patient expectations, and staffing pressures can lead to reduced hands-on experience for trainees. The results: an entire generation of surgeons with decreased repetitions in the operating room when compared to their predecessors.

That’s why I believe we are on the cusp of a transition in the operating room, and that computer-assisted surgery is here to stay. While studies exist showing robots have tighter control over virtually every identifiable metric, little data currently exists supporting enhanced long-term outcomes. But as long as component malposition remains a leading cause of early failure, there will be a place for technologies that enhance accuracy of component placement. At odds with the drive for increased technology is the necessity of cost containment, leading us to question the value of robotic-assisted surgery, and whether the improved metrics are clinically important and the additional potential complications are worth the risk.

In the articles in this issue, we will take a critical look at the benefits and drawbacks of robotic surgery. As you read, think about the future of orthopedics and how you will implement new technology into your practice. A transition is coming, and I invite each of you to consider leading it.

A transition is underway at AJO. As we discuss the future of the “new journal,” I often think about the future of orthopedics. I’ve decided my vision of the future is centered on 3 components. First, there will be a change in our training paradigm from an apprenticeship model to standardized training, where core competencies must be demonstrated for certification. Second, robots and computers will improve our diagnostic accuracy and will allow us to perform surgery with improved component positioning, while biologics and genetic analysis will accelerate nature’s ability to heal, and perhaps regenerate, injured tissue. Finally, computerized algorithms and technologically improved surgical outcomes will allow us to deliver high-quality healthcare at a lower cost, producing the value our current health systems are striving for, and leveling the playing field between high-volume centers and rural institutions forced to offer complete service lines.

In this issue, we examine robotic-assisted arthroplasty and its role in modern healthcare. I think the best argument for robots in the operating room might come from the airline industry. I’m sitting on a plane as I write this, without once thinking about how much experience my pilot has in the cockpit. I know our pilot has demonstrated the core competencies required to safely operate the plane, trained on emergency simulations, and logged the necessary hours before being handed the controls. I also know that the instrumentation is so good that the plane can essentially fly itself, making pilot skill and experience less relevant. In short, technology has, in all but rare circumstances, made our pilots virtually interchangeable.

Unfortunately, none of the above is true in orthopedics. Our residents are not required to demonstrate their skills before any licensing authority, simulator training is not available in all programs, and we’ve limited resident work hours. Yet it’s that same interchangeability that most healthcare models assume. No one argues that high-volume centers have better results when it comes to arthroplasty, but only a small percentage of total joints are currently performed at these centers. Surgeon training remains a virtual apprenticeship, lacking standardization, and resulting in a wide variation in skill and experience. Surgical residencies are not awarded based on dexterity, and work hour restrictions, Relative Value Unit-based academic contracts, patient expectations, and staffing pressures can lead to reduced hands-on experience for trainees. The results: an entire generation of surgeons with decreased repetitions in the operating room when compared to their predecessors.

That’s why I believe we are on the cusp of a transition in the operating room, and that computer-assisted surgery is here to stay. While studies exist showing robots have tighter control over virtually every identifiable metric, little data currently exists supporting enhanced long-term outcomes. But as long as component malposition remains a leading cause of early failure, there will be a place for technologies that enhance accuracy of component placement. At odds with the drive for increased technology is the necessity of cost containment, leading us to question the value of robotic-assisted surgery, and whether the improved metrics are clinically important and the additional potential complications are worth the risk.

In the articles in this issue, we will take a critical look at the benefits and drawbacks of robotic surgery. As you read, think about the future of orthopedics and how you will implement new technology into your practice. A transition is coming, and I invite each of you to consider leading it.

A transition is underway at AJO. As we discuss the future of the “new journal,” I often think about the future of orthopedics. I’ve decided my vision of the future is centered on 3 components. First, there will be a change in our training paradigm from an apprenticeship model to standardized training, where core competencies must be demonstrated for certification. Second, robots and computers will improve our diagnostic accuracy and will allow us to perform surgery with improved component positioning, while biologics and genetic analysis will accelerate nature’s ability to heal, and perhaps regenerate, injured tissue. Finally, computerized algorithms and technologically improved surgical outcomes will allow us to deliver high-quality healthcare at a lower cost, producing the value our current health systems are striving for, and leveling the playing field between high-volume centers and rural institutions forced to offer complete service lines.

In this issue, we examine robotic-assisted arthroplasty and its role in modern healthcare. I think the best argument for robots in the operating room might come from the airline industry. I’m sitting on a plane as I write this, without once thinking about how much experience my pilot has in the cockpit. I know our pilot has demonstrated the core competencies required to safely operate the plane, trained on emergency simulations, and logged the necessary hours before being handed the controls. I also know that the instrumentation is so good that the plane can essentially fly itself, making pilot skill and experience less relevant. In short, technology has, in all but rare circumstances, made our pilots virtually interchangeable.

Unfortunately, none of the above is true in orthopedics. Our residents are not required to demonstrate their skills before any licensing authority, simulator training is not available in all programs, and we’ve limited resident work hours. Yet it’s that same interchangeability that most healthcare models assume. No one argues that high-volume centers have better results when it comes to arthroplasty, but only a small percentage of total joints are currently performed at these centers. Surgeon training remains a virtual apprenticeship, lacking standardization, and resulting in a wide variation in skill and experience. Surgical residencies are not awarded based on dexterity, and work hour restrictions, Relative Value Unit-based academic contracts, patient expectations, and staffing pressures can lead to reduced hands-on experience for trainees. The results: an entire generation of surgeons with decreased repetitions in the operating room when compared to their predecessors.

That’s why I believe we are on the cusp of a transition in the operating room, and that computer-assisted surgery is here to stay. While studies exist showing robots have tighter control over virtually every identifiable metric, little data currently exists supporting enhanced long-term outcomes. But as long as component malposition remains a leading cause of early failure, there will be a place for technologies that enhance accuracy of component placement. At odds with the drive for increased technology is the necessity of cost containment, leading us to question the value of robotic-assisted surgery, and whether the improved metrics are clinically important and the additional potential complications are worth the risk.

In the articles in this issue, we will take a critical look at the benefits and drawbacks of robotic surgery. As you read, think about the future of orthopedics and how you will implement new technology into your practice. A transition is coming, and I invite each of you to consider leading it.

Make Room on Your Shelves

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.

As orthopedic surgeons, we’ve made a commitment to lifelong learning. I can’t think of a single surgery that I perform the same way I did when I was in training. With rapidly evolving technology, continuously advancing procedures, and ever-increasing documentation requirements, it’s hard to stay on top of it all. We know your time is precious and that you have less of it than ever before. What little time you have that is not dedicated to work is reserved for your family or your hobbies. There’s no time to read every orthopedic journal, many filled with articles that have no practical value to your practice. That’s why we’ve created the new AJO. Our goal, as an editorial staff, is to provide a journal where every article, column, and feature contains information that directly benefits your practice, your patients, or your bottom line, and keeps you informed of the latest techniques, procedures, and products. We will help surgeons “work smarter, not harder,” implement new technologies into their practices, and find creative revenue streams that are both legal and compliant.

We’ve assembled a team of talented editors to accomplish this task, and will introduce them throughout the coming year. In this issue, you will meet our Deputy Editors-in-Chief and some of our new Associate Editors who’ve collaborated to bring you the “new AJO”.

At this year’s Academy, the AJO launched an extensive rebranding. We have a new look, a new logo, and a new creative directive. The journal will now feature new columns, invited articles, and innovative surgical techniques. We will publish 5 issues for the remainder of 2016. Our March/April issue is a special edition dedicated to baseball. In time for Spring Training/Opening Day, this issue includes articles from Major League Baseball’s physicians and trainers, a “Codes to Know” segment, “Tips of the Trade,” and a “Tools of the Trade” feature. “The Baseball Issue” will set the tone for what readers can expect from the “new AJO”.

Our first feature article, written by Jed Kuhn, takes a philosophical look at the evolution of the throwing shoulder, and invites the reader to help unlock some of the great shoulder anatomy mysteries by viewing them from a time when throwing was an activity of daily living. In ancient times, if you couldn’t throw, you couldn’t eat. We know that children who play baseball remodel their shoulder to allow for increased external rotation. Read Dr. Kuhn’s article and imagine when a shoulder optimized for throwing was a competitive advantage for survival.

Our second feature article is written by Stan Conte, a legend of the game and longtime trainer for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dr. Conte studied injury trends in baseball over the past 18 seasons and provides an analysis of the staggering cost of placing players on the disabled list.

A baseball issue could not be complete without an article on Tommy John surgery. In this issue, AJO shares a revolutionary new technique for treating players with MUCL tears by author Jeffrey Dugas. Named the “Internal Brace”, Dr. Dugas shares his technique for augmenting the injured MUCL and we are proud to bring it to you first.

A recurring feature in the new AJO will be a section we refer to as “Codes to Know.” In partnership with Karen Zupko, AJO will present little-known coding secrets and proper coding techniques to help you get reimbursed appropriately for your work. This month, in the first article of a 3-part series, Alan Hirahara teaches us how to properly code for a diagnostic ultrasound examination of the shoulder. The article includes templates available for download to assist you with proper documentation. Parts 2 and 3 will provide a tutorial on the proper technique for examinations and injections.

While shoulder and elbow injuries get more attention, Major League Baseball’s Injury Panel has produced a look at the staggering amount of knee injuries over the 2011-2014 seasons, inspiring us to feature the knee in our 2 “Trade” Columns.

The “Tips of the Trade” column will continue, featuring this month a guide to identifying and treating meniscal root tears. A new segment, referred to as “Tools of the Trade,” reviews the latest products for all-inside meniscal repair. Our “Tools” section will feature announcements and reviews of the hottest new products, with a buying guide and surgical pearls from the surgeons who know them best.

While we are discussing the lower extremity, we should point out that we plan to do the “leg work” for you. Each AJO issue will have handouts that can be downloaded from our website and utilized in your practice. Read Robin West’s article entitled “Interval Throwing and Hitting Programs in Baseball: Biomechanics and Rehabilitation,” and download Return to Throwing and Hitting programs your patients and therapists can use.

Finally, I’d like to thank our previous Editor-in-Chief Dr. Peter McCann for his stewardship the last 10 years and recognize him for his dedication to the journal.

Thank you for reading AJO and for continuing to do so in the future. I know that collectively, we can turn AJO into a product worthy of its title. We know our past reputation. We are no longer that journal. Spend some time to get to know the “new AJO”, and make some room on your shelves, because the information between the covers will provide a template to implement new technologies and revenue streams into your practice and help fulfill your commitment to learning.