User login

Hindsight Is 20/20

A 38-year-old woman presented to her primary care clinic with 3 weeks of progressive numbness and tingling sensation, which began in both hands and then progressed to involv

As with all neurological complaints, localization of the process will often inform a more specific differential diagnosis. If both sensory and motor findings are present, both central and peripheral nerve processes deserve consideration. The onset of paresthesia in the hands, rapid progression to the trunk, and unilateral leg weakness would be inconsistent with a length-dependent peripheral neuropathy. The distribution of complaints and the sacral sparing suggests a myelopathic process involving the cervical region rather than a cauda equina or conus lesions. In an otherwise healthy person of this age and gender, an inflammatory demyelinating disease affecting the cord including multiple sclerosis (MS) would be a strong consideration, although metabolic, vascular, infectious, compressive, or neoplastic disease of the spinal cord could also present with similar subacute onset and pattern of deficits.

Her medical history included morbid obesity, dry eyes, depression, iron deficiency anemia requiring recurrent intravenous replenishment, and abnormal uterine bleeding. Her surgical history included gastric band placement 7 years earlier with removal 5 years later due to persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting. The gastric band removal was complicated by chronic abdominal pain. Her medications consisted of duloxetine, intermittent iron infusions, artificial tears, loratadine, and pregabalin. She was sexually active with her husband. She consumed alcohol occasionally but did not smoke tobacco or use illicit drugs.

On exam, her temperature was 36.6°C (97.8°F), blood pressure 132/84 mm Hg, and heart rate 85 beats per minute. Body mass index was 39.5 kg/m2. The cardiac, pulmonary, and skin examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft with diffuse tenderness to palpation without rebound or guarding. Examination of cranial nerves 2-12 was normal. Cognition, strength, proprioception, deep tendon reflexes, and light touch were all normal. Her gait was normal, and the Romberg test was negative.

The normal neurologic exam is reassuring but imperfectly sensitive and does not eliminate the possibility of underlying neuropathology. Bariatric surgery may result in an array of nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin E, B12, and copper, which can cause myelopathy and/or neuropathy. However, these abnormalities occur less frequently with gastric banding procedures. If her dry eyes are part of the sicca syndrome, an underlying autoimmune diathesis may be present. Her unexplained chronic abdominal pain prompts considering nonmenstrual causes of iron deficiency anemia, such as celiac disease. Bariatric surgery may contribute to iron deficiency through impaired iron absorption. Her stable weight and lack of diarrhea argue against Crohn’s or celiac disease. Iron deficiency predisposes individuals to pica, most commonly described with ice chip ingestion. If lead pica had occurred, abdominal and neurological symptoms could result. Nevertheless, the abdominal pain is nonspecific, and its occurrence after gastric band removal makes its link to her neurologic syndrome unclear. An initial evaluation would include basic metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, and copper levels.

A basic metabolic panel was normal. The white cell count was 5,710 per cubic millimeter, hemoglobin level 12.2 g per deciliter, mean corpuscular volume 85.2 fl, and platelet count 279,000 per cubic millimeter. The serum ferritin level was 18 ng per milliliter (normal range, 13-150), iron 28 µg per deciliter (normal range, 50-170), total iron-binding capacity 364 µg per deciliter (normal range, 250-450), and iron saturation 8% (normal range, 20-55). The vitamin B12 level was 621 pg per milliliter (normal range, 232-1,245) and thyroid-stimulating hormone level 1.87 units per milliliter (normal range, 0.50-4.50). Electrolyte and aminotransferase levels were within normal limits. CRP was 1.0 mg per deciliter (normal range, <0.5) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 33 millimeters per hour (normal range, 4-25). Hepatitis C and HIV antibodies were nonreactive.

The ongoing iron deficiency despite parenteral iron replacement raises the question of ongoing gastrointestinal or genitourinary blood loss. While the level of vitamin B12 in the serum may be misleadingly normal with cobalamin deficiency, a methylmalonic acid level is indicated to evaluate whether tissue stores are depleted. Copper levels are warranted given the prior bariatric surgery. The mild elevations of inflammatory markers are nonspecific but reduce the likelihood of a highly inflammatory process to account for the neurological and abdominal symptoms.

At her 3-month follow-up visit, she noted that the paresthesia had improved and was now limited to her bilateral lower extremities. During the same clinic visit, she experienced a 45-minute episode of ascending left upper extremity numbness. Her physical examination revealed normal strength and reflexes. She had diminished response to pinprick in both legs to the knees and in both hands to the wrists. Vibration sense was diminished in the bilateral lower extremities.

A glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 6.2%. Methylmalonic acid was 69 nmol per liter (normal range, 45-325). Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum were absent. Impaired glucose metabolism was the leading diagnosis for her polyneuropathy, and it was recommended that she undergo an oral glucose tolerance test. Electromyography was not performed.

The neurological symptoms are now chronic, and importantly, the patient has developed sensory deficits on neurological examination, suggesting worsening of the underlying process. While the paresthesia is now limited to a “stocking/glove” distribution consistent with distal sensory polyneuropathy, there should still be a concern for spinal cord pathology given that the HbA1c level of 6.2 would not explain her initial distribution of symptoms. Myelopathy may mimic peripheral nerve disease if, for example, there is involvement of the dorsal columns leading to sensory deficits of vibration and proprioception. Additionally, the transient episode of upper extremity numbness raises the question of sensory nerve root involvement (ie, sensory radiculopathy). Unexplained abdominal pain could possibly represent the involvement of other nerve roots innervating the abdominal wall. The patient’s episode of focal arm numbness recalls the lancinating radicular pain of tabes dorsalis; however, the negative specific treponemal antibody test excludes neurosyphilis.

The differential diagnosis going forward will be strongly conditioned by the localization of the neurological lesion(s). To differentiate between myelopathy, radiculopathy, and peripheral neuropathy, I would perform nerve conduction studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

The patient began taking a multivitamin, and after weeks her paresthesia had resolved. One month later, she developed an intermittent, throbbing left-sided headache and pain behind the left eye that was worsened with ocular movement. She then noted decreased visual acuity in her left eye that progressed the following month. She denied photophobia, flashers, or floaters.

In the emergency department, visual acuity was 20/25 in her right eye; in the left eye she was only able to count fingers. Extraocular movements of both eyes were normal as was her right pupillary reflex. Red desaturation and a relative afferent papillary defect were present in the left eye. Fundoscopic exam demonstrated left optic disc swelling. The remainder of her cranial nerves were normal. She had pronation of the left upper extremity and mild right finger-to-nose dysmetria. Muscle tone, strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes were normal.

The improvement in the sensory symptoms was unlikely to be related to the nutritional intervention and provides a clue to an underlying waxing and waning illness. That interpretation is supported by the subsequent development of new visual symptoms and signs, which point to optic nerve pathology. Optic neuropathy has a broad differential diagnosis that includes ischemic, metabolic, toxic, and compressive causes. Eye pain, swelling of the optic disc, and prominent impairment of color vision all point to the more specific syndrome of optic neuritis caused by infections (including both Treponema pallidum and Borrelia species), systemic autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome), and central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating diseases. Of these, inflammatory demyelinating processes would be the likeliest explanation of intermittent and improving neurologic findings.

With relapsing symptoms and findings that are separate in distribution and time, two diagnoses become most likely, and both of these are most often diagnosed in young women. MS is common, and optic neuritis occurs in more than 50% of patients over the course of illness. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare condition that can exist in isolation or be associated with other autoimmune illnesses. While these entities are difficult to differentiate clinically, neuroimaging that demonstrates extensive intracerebral demyelinating lesions and cerebrospinal fluid with oligoclonal bands favor MS, whereas extensive, predominant spinal cord involvement is suggestive of NMOSD. Approximately 70% of NMO patients harbor an antibody directed against the aquaporin-4 channel, and these antibodies are not seen in patients with MS. A milder NMO-like disorder has also been associated with antimyelin oligodendrocyte antibodies (MOG).

Testing for antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB) antibodies was negative. The level of C3 was 162 mg per deciliter (normal range 81-157) and C4 38 (normal range 13-39). T-spot testing for latent tuberculosis was negative.

There is no serological evidence of active systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome. The pretest probability of CNS tuberculosis was low in light of her presenting complaints, relatively protracted course, and overall clinical stability without antituberculous therapy. Tests for latent tuberculosis infection have significant limitations of both sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of active disease.

Optical coherence tomography showed optic disc edema in the left eye only. MRI of the head with contrast revealed abnormal signal intensity involving the posterior aspect of the pons, right middle cerebellar peduncle, anterior left temporal lobe, bilateral periventricular white matter, subcortical white matter of the frontal lobes bilaterally, and medulla with abnormal signal and enhancement of the left optic nerve (Figure, Panel A). MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated multifocal demyelinating lesions at C3, C4, C7, T4, T5, T7, and T8 (Figure, Panel B). The lesions were not longitudinally extensive. There was no significant postcontrast enhancement to suggest active demyelination.

The cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed glucose of 105 mg per deciliter and a total protein of 26.1 mg per deciliter. In the fourth tube, there were 20 red cells per cubic and four white cells with a differential of 62% neutrophils, 35% lymphocytes, and 3% monocytes. Epstein-Barr and herpes simplex virus DNA were negative. A Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test was negative. Multiple oligoclonal IgG bands were identified only in the cerebrospinal fluid. Aquaporin-4 IgG and MOG antibodies were negative.

In addition to the expected finding of enhancement of the optic nerve, MRI demonstrated numerous multifocal white matter lesions throughout the cerebrum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Many of the lesions were in “silent” areas, which is not directly attributable to specific symptoms, but several did correlate with the subtler deficits of weakness and dysmetria that were noted on examination. Although such lesions may be seen with a diverse group of systemic diseases including adrenal leukodystrophy, sarcoidosis, Behcet’s, cerebral lupus, and vasculitis, primary CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases are much more likely. The extensive distribution of demyelination argues against NMOSD. The negative aquaporin-4 and MOG assays support this conclusion. Not all multifocal CNS demyelination is caused by MS and can be seen in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, and adult polyglucosan body disease. Osmotic demyelination is increasingly being recognized as a process that can be more widespread rather than just being limited to the pons. Viral infections of the CNS such as the JC virus (PML) may also provoke multifocal demyelination. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is most often seen during childhood, usually after vaccination or after an infectious prodrome. The tempo of the progression of these other diseases tends to be much more rapid than this woman’s course, and often, the neurological deficits are more profound and debilitating. The clinical presentation of sensory-predominant myelopathy, followed by optic neuritis, absence of systemic inflammatory signs or laboratory markers, exclusion of other relevant diseases, multifocal white matter lesions on imaging, minimal pleocytosis, and presence of oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid, all point to a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS.

The patient was diagnosed with MS. She was admitted to the neurology service and treated with 1,000 mg IV methylprednisolone for 3 days with a prompt improvement in her vision. She was started on natalizumab without a relapse of symptoms over the past year.

COMMENTARY

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic demyelinating disease of the CNS.1 The diagnosis of MS has classically been based upon compatible clinical and radiographic evidence of pathology that is disseminated in space and time. Patients typically present with an initial clinically isolated syndrome—involving changes in vision, sensation, strength, mobility, or cognition—for which there is radiographic evidence of demyelination.2 A diagnosis of clinically definite MS is then often made based on a subsequent relapse of symptoms.3

An interval from initial symptoms has been central to the diagnosis of MS (“lesions disseminated in time”). However, recent evidence questions this diagnostic paradigm, and a more rapid diagnosis of MS has been recommended. This recommendation is reflected in the updated McDonald criteria, according to which, if a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.4 The importance of such early diagnosis has been supported by numerous studies that have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with early therapy.5-7

Despite the McDonald criteria, delays in definitive diagnosis are common in MS. Patients with MS in Spain were found to experience a 2-year delay from the first onset of symptoms to diagnosis.8 In this cohort, patients exhibited delays in presenting to a healthcare provider, as well as delays in diagnosis with an average time from seeing an initial provider to diagnosis of 6 months. When patients who were referred for a demyelinating episode were surveyed, over a third reported a prior suggestive event.9 The time from the first suggestive episode to referral to a neurologist for a recognized demyelinating event was 46 months. Other studies have shown that delays in diagnosis are especially common in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.10,11

Misapplication of an MS diagnosis also occurs frequently. In one case series, such misapplication was found most often in cases involving migraine, fibromyalgia, psychogenic disorders, and NMOSD.12 NMOSD is distinguished from MS by the presence of typical brain and spine findings on MRI.13 Antibodies to aquaporin-4 are highly specific and moderately sensitive for the disease.14 It is important to distinguish NMOSD from MS as certain disease-modifying drugs used for MS might actually exacerbate NMOSD.15 A lesion that traverses over three or more contiguous vertebral segments with predominant involvement of central gray matter (ie, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis) on MRI is the most distinct finding of NMOSD. In contrast, similar to our patient, short and often multiple lesions are demonstrated on spinal cord MRI in patients with MS. Sensitive and specific findings of brain MRI in patients with MS include the presence of lateral ventricle and inferior temporal lobe lesion, Dawson’s fingers, central vein sign, or an S-shaped U-fiber lesion. In NMOSD, brain MRI might reveal periependymal lesions surrounding the ventricular system.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges related to presentations of a waxing and waning neurological process. At the time of the second evaluation, the presentation was interpreted as a length-dependent polyneuropathy due to glucose intolerance. Our patient’s relatively normal HbA1c, subacute onset of neuropathic symptoms (ie, <4 weeks), sensory and motor complaints, and onset in the upper extremities suggested an alternative diagnosis to prediabetes. Once the patient presented with optic neuritis, the cause of the initial symptoms was obvious, but then, hindsight is 20/20.

TEACHING POINTS

- Early treatment of MS results in improved clinical outcomes.

- Delays in the definitive diagnosis of MS are common, especially in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.

- If a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis of MS can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rabih Geha, MD, and Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, for providing feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

1. Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:169-180. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra140148.

2. Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336-1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30959-X.

3. Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622-1636. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30481-1.

4. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

5. Comi G, Radaelli M, Soelberg Sørensen P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1347-1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32388-1.

6. Freedman MS, Comi G, De Stefano N, et al. Moving toward earlier treatment of multiple sclerosis: Findings from a decade of clinical trials and implications for clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(2):147-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2013.07.001.

7. Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536-541. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4905.

8. Fernández O, Fernández V, Arbizu T, et al. Characteristics of multiple sclerosis at onset and delay of diagnosis and treatment in Spain (the Novo Study). J Neurol. 257(9):1500-1507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5560-1.

9. Gout O, Lebrun-Frenay C, Labauge P, et al. Prior suggestive symptoms in one-third of patients consulting for a “first” demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82(3):323-325. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.166421.

10. Kingwell E, Leung A, Roger E, et al. Factors associated with delay to medical recognition in two Canadian multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Neurol Sci. 2010(1-2);292:57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.007.

11. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Comorbidity delays diagnosis and increases disability at diagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2009;72(2):117-124. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000333252.78173.5f.

12. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003152.

13. Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: An international update. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1165-1173. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001367.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177-189. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729.

15. Jacob A, Hutchinson M, Elsone L, et al. Does natalizumab therapy worsen neuromyelitis optica? Neurology. 2012;79(10):1065-1066. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826845fe.

A 38-year-old woman presented to her primary care clinic with 3 weeks of progressive numbness and tingling sensation, which began in both hands and then progressed to involv

As with all neurological complaints, localization of the process will often inform a more specific differential diagnosis. If both sensory and motor findings are present, both central and peripheral nerve processes deserve consideration. The onset of paresthesia in the hands, rapid progression to the trunk, and unilateral leg weakness would be inconsistent with a length-dependent peripheral neuropathy. The distribution of complaints and the sacral sparing suggests a myelopathic process involving the cervical region rather than a cauda equina or conus lesions. In an otherwise healthy person of this age and gender, an inflammatory demyelinating disease affecting the cord including multiple sclerosis (MS) would be a strong consideration, although metabolic, vascular, infectious, compressive, or neoplastic disease of the spinal cord could also present with similar subacute onset and pattern of deficits.

Her medical history included morbid obesity, dry eyes, depression, iron deficiency anemia requiring recurrent intravenous replenishment, and abnormal uterine bleeding. Her surgical history included gastric band placement 7 years earlier with removal 5 years later due to persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting. The gastric band removal was complicated by chronic abdominal pain. Her medications consisted of duloxetine, intermittent iron infusions, artificial tears, loratadine, and pregabalin. She was sexually active with her husband. She consumed alcohol occasionally but did not smoke tobacco or use illicit drugs.

On exam, her temperature was 36.6°C (97.8°F), blood pressure 132/84 mm Hg, and heart rate 85 beats per minute. Body mass index was 39.5 kg/m2. The cardiac, pulmonary, and skin examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft with diffuse tenderness to palpation without rebound or guarding. Examination of cranial nerves 2-12 was normal. Cognition, strength, proprioception, deep tendon reflexes, and light touch were all normal. Her gait was normal, and the Romberg test was negative.

The normal neurologic exam is reassuring but imperfectly sensitive and does not eliminate the possibility of underlying neuropathology. Bariatric surgery may result in an array of nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin E, B12, and copper, which can cause myelopathy and/or neuropathy. However, these abnormalities occur less frequently with gastric banding procedures. If her dry eyes are part of the sicca syndrome, an underlying autoimmune diathesis may be present. Her unexplained chronic abdominal pain prompts considering nonmenstrual causes of iron deficiency anemia, such as celiac disease. Bariatric surgery may contribute to iron deficiency through impaired iron absorption. Her stable weight and lack of diarrhea argue against Crohn’s or celiac disease. Iron deficiency predisposes individuals to pica, most commonly described with ice chip ingestion. If lead pica had occurred, abdominal and neurological symptoms could result. Nevertheless, the abdominal pain is nonspecific, and its occurrence after gastric band removal makes its link to her neurologic syndrome unclear. An initial evaluation would include basic metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, and copper levels.

A basic metabolic panel was normal. The white cell count was 5,710 per cubic millimeter, hemoglobin level 12.2 g per deciliter, mean corpuscular volume 85.2 fl, and platelet count 279,000 per cubic millimeter. The serum ferritin level was 18 ng per milliliter (normal range, 13-150), iron 28 µg per deciliter (normal range, 50-170), total iron-binding capacity 364 µg per deciliter (normal range, 250-450), and iron saturation 8% (normal range, 20-55). The vitamin B12 level was 621 pg per milliliter (normal range, 232-1,245) and thyroid-stimulating hormone level 1.87 units per milliliter (normal range, 0.50-4.50). Electrolyte and aminotransferase levels were within normal limits. CRP was 1.0 mg per deciliter (normal range, <0.5) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 33 millimeters per hour (normal range, 4-25). Hepatitis C and HIV antibodies were nonreactive.

The ongoing iron deficiency despite parenteral iron replacement raises the question of ongoing gastrointestinal or genitourinary blood loss. While the level of vitamin B12 in the serum may be misleadingly normal with cobalamin deficiency, a methylmalonic acid level is indicated to evaluate whether tissue stores are depleted. Copper levels are warranted given the prior bariatric surgery. The mild elevations of inflammatory markers are nonspecific but reduce the likelihood of a highly inflammatory process to account for the neurological and abdominal symptoms.

At her 3-month follow-up visit, she noted that the paresthesia had improved and was now limited to her bilateral lower extremities. During the same clinic visit, she experienced a 45-minute episode of ascending left upper extremity numbness. Her physical examination revealed normal strength and reflexes. She had diminished response to pinprick in both legs to the knees and in both hands to the wrists. Vibration sense was diminished in the bilateral lower extremities.

A glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 6.2%. Methylmalonic acid was 69 nmol per liter (normal range, 45-325). Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum were absent. Impaired glucose metabolism was the leading diagnosis for her polyneuropathy, and it was recommended that she undergo an oral glucose tolerance test. Electromyography was not performed.

The neurological symptoms are now chronic, and importantly, the patient has developed sensory deficits on neurological examination, suggesting worsening of the underlying process. While the paresthesia is now limited to a “stocking/glove” distribution consistent with distal sensory polyneuropathy, there should still be a concern for spinal cord pathology given that the HbA1c level of 6.2 would not explain her initial distribution of symptoms. Myelopathy may mimic peripheral nerve disease if, for example, there is involvement of the dorsal columns leading to sensory deficits of vibration and proprioception. Additionally, the transient episode of upper extremity numbness raises the question of sensory nerve root involvement (ie, sensory radiculopathy). Unexplained abdominal pain could possibly represent the involvement of other nerve roots innervating the abdominal wall. The patient’s episode of focal arm numbness recalls the lancinating radicular pain of tabes dorsalis; however, the negative specific treponemal antibody test excludes neurosyphilis.

The differential diagnosis going forward will be strongly conditioned by the localization of the neurological lesion(s). To differentiate between myelopathy, radiculopathy, and peripheral neuropathy, I would perform nerve conduction studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

The patient began taking a multivitamin, and after weeks her paresthesia had resolved. One month later, she developed an intermittent, throbbing left-sided headache and pain behind the left eye that was worsened with ocular movement. She then noted decreased visual acuity in her left eye that progressed the following month. She denied photophobia, flashers, or floaters.

In the emergency department, visual acuity was 20/25 in her right eye; in the left eye she was only able to count fingers. Extraocular movements of both eyes were normal as was her right pupillary reflex. Red desaturation and a relative afferent papillary defect were present in the left eye. Fundoscopic exam demonstrated left optic disc swelling. The remainder of her cranial nerves were normal. She had pronation of the left upper extremity and mild right finger-to-nose dysmetria. Muscle tone, strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes were normal.

The improvement in the sensory symptoms was unlikely to be related to the nutritional intervention and provides a clue to an underlying waxing and waning illness. That interpretation is supported by the subsequent development of new visual symptoms and signs, which point to optic nerve pathology. Optic neuropathy has a broad differential diagnosis that includes ischemic, metabolic, toxic, and compressive causes. Eye pain, swelling of the optic disc, and prominent impairment of color vision all point to the more specific syndrome of optic neuritis caused by infections (including both Treponema pallidum and Borrelia species), systemic autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome), and central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating diseases. Of these, inflammatory demyelinating processes would be the likeliest explanation of intermittent and improving neurologic findings.

With relapsing symptoms and findings that are separate in distribution and time, two diagnoses become most likely, and both of these are most often diagnosed in young women. MS is common, and optic neuritis occurs in more than 50% of patients over the course of illness. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare condition that can exist in isolation or be associated with other autoimmune illnesses. While these entities are difficult to differentiate clinically, neuroimaging that demonstrates extensive intracerebral demyelinating lesions and cerebrospinal fluid with oligoclonal bands favor MS, whereas extensive, predominant spinal cord involvement is suggestive of NMOSD. Approximately 70% of NMO patients harbor an antibody directed against the aquaporin-4 channel, and these antibodies are not seen in patients with MS. A milder NMO-like disorder has also been associated with antimyelin oligodendrocyte antibodies (MOG).

Testing for antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB) antibodies was negative. The level of C3 was 162 mg per deciliter (normal range 81-157) and C4 38 (normal range 13-39). T-spot testing for latent tuberculosis was negative.

There is no serological evidence of active systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome. The pretest probability of CNS tuberculosis was low in light of her presenting complaints, relatively protracted course, and overall clinical stability without antituberculous therapy. Tests for latent tuberculosis infection have significant limitations of both sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of active disease.

Optical coherence tomography showed optic disc edema in the left eye only. MRI of the head with contrast revealed abnormal signal intensity involving the posterior aspect of the pons, right middle cerebellar peduncle, anterior left temporal lobe, bilateral periventricular white matter, subcortical white matter of the frontal lobes bilaterally, and medulla with abnormal signal and enhancement of the left optic nerve (Figure, Panel A). MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated multifocal demyelinating lesions at C3, C4, C7, T4, T5, T7, and T8 (Figure, Panel B). The lesions were not longitudinally extensive. There was no significant postcontrast enhancement to suggest active demyelination.

The cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed glucose of 105 mg per deciliter and a total protein of 26.1 mg per deciliter. In the fourth tube, there were 20 red cells per cubic and four white cells with a differential of 62% neutrophils, 35% lymphocytes, and 3% monocytes. Epstein-Barr and herpes simplex virus DNA were negative. A Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test was negative. Multiple oligoclonal IgG bands were identified only in the cerebrospinal fluid. Aquaporin-4 IgG and MOG antibodies were negative.

In addition to the expected finding of enhancement of the optic nerve, MRI demonstrated numerous multifocal white matter lesions throughout the cerebrum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Many of the lesions were in “silent” areas, which is not directly attributable to specific symptoms, but several did correlate with the subtler deficits of weakness and dysmetria that were noted on examination. Although such lesions may be seen with a diverse group of systemic diseases including adrenal leukodystrophy, sarcoidosis, Behcet’s, cerebral lupus, and vasculitis, primary CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases are much more likely. The extensive distribution of demyelination argues against NMOSD. The negative aquaporin-4 and MOG assays support this conclusion. Not all multifocal CNS demyelination is caused by MS and can be seen in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, and adult polyglucosan body disease. Osmotic demyelination is increasingly being recognized as a process that can be more widespread rather than just being limited to the pons. Viral infections of the CNS such as the JC virus (PML) may also provoke multifocal demyelination. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is most often seen during childhood, usually after vaccination or after an infectious prodrome. The tempo of the progression of these other diseases tends to be much more rapid than this woman’s course, and often, the neurological deficits are more profound and debilitating. The clinical presentation of sensory-predominant myelopathy, followed by optic neuritis, absence of systemic inflammatory signs or laboratory markers, exclusion of other relevant diseases, multifocal white matter lesions on imaging, minimal pleocytosis, and presence of oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid, all point to a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS.

The patient was diagnosed with MS. She was admitted to the neurology service and treated with 1,000 mg IV methylprednisolone for 3 days with a prompt improvement in her vision. She was started on natalizumab without a relapse of symptoms over the past year.

COMMENTARY

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic demyelinating disease of the CNS.1 The diagnosis of MS has classically been based upon compatible clinical and radiographic evidence of pathology that is disseminated in space and time. Patients typically present with an initial clinically isolated syndrome—involving changes in vision, sensation, strength, mobility, or cognition—for which there is radiographic evidence of demyelination.2 A diagnosis of clinically definite MS is then often made based on a subsequent relapse of symptoms.3

An interval from initial symptoms has been central to the diagnosis of MS (“lesions disseminated in time”). However, recent evidence questions this diagnostic paradigm, and a more rapid diagnosis of MS has been recommended. This recommendation is reflected in the updated McDonald criteria, according to which, if a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.4 The importance of such early diagnosis has been supported by numerous studies that have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with early therapy.5-7

Despite the McDonald criteria, delays in definitive diagnosis are common in MS. Patients with MS in Spain were found to experience a 2-year delay from the first onset of symptoms to diagnosis.8 In this cohort, patients exhibited delays in presenting to a healthcare provider, as well as delays in diagnosis with an average time from seeing an initial provider to diagnosis of 6 months. When patients who were referred for a demyelinating episode were surveyed, over a third reported a prior suggestive event.9 The time from the first suggestive episode to referral to a neurologist for a recognized demyelinating event was 46 months. Other studies have shown that delays in diagnosis are especially common in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.10,11

Misapplication of an MS diagnosis also occurs frequently. In one case series, such misapplication was found most often in cases involving migraine, fibromyalgia, psychogenic disorders, and NMOSD.12 NMOSD is distinguished from MS by the presence of typical brain and spine findings on MRI.13 Antibodies to aquaporin-4 are highly specific and moderately sensitive for the disease.14 It is important to distinguish NMOSD from MS as certain disease-modifying drugs used for MS might actually exacerbate NMOSD.15 A lesion that traverses over three or more contiguous vertebral segments with predominant involvement of central gray matter (ie, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis) on MRI is the most distinct finding of NMOSD. In contrast, similar to our patient, short and often multiple lesions are demonstrated on spinal cord MRI in patients with MS. Sensitive and specific findings of brain MRI in patients with MS include the presence of lateral ventricle and inferior temporal lobe lesion, Dawson’s fingers, central vein sign, or an S-shaped U-fiber lesion. In NMOSD, brain MRI might reveal periependymal lesions surrounding the ventricular system.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges related to presentations of a waxing and waning neurological process. At the time of the second evaluation, the presentation was interpreted as a length-dependent polyneuropathy due to glucose intolerance. Our patient’s relatively normal HbA1c, subacute onset of neuropathic symptoms (ie, <4 weeks), sensory and motor complaints, and onset in the upper extremities suggested an alternative diagnosis to prediabetes. Once the patient presented with optic neuritis, the cause of the initial symptoms was obvious, but then, hindsight is 20/20.

TEACHING POINTS

- Early treatment of MS results in improved clinical outcomes.

- Delays in the definitive diagnosis of MS are common, especially in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.

- If a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis of MS can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rabih Geha, MD, and Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, for providing feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

A 38-year-old woman presented to her primary care clinic with 3 weeks of progressive numbness and tingling sensation, which began in both hands and then progressed to involv

As with all neurological complaints, localization of the process will often inform a more specific differential diagnosis. If both sensory and motor findings are present, both central and peripheral nerve processes deserve consideration. The onset of paresthesia in the hands, rapid progression to the trunk, and unilateral leg weakness would be inconsistent with a length-dependent peripheral neuropathy. The distribution of complaints and the sacral sparing suggests a myelopathic process involving the cervical region rather than a cauda equina or conus lesions. In an otherwise healthy person of this age and gender, an inflammatory demyelinating disease affecting the cord including multiple sclerosis (MS) would be a strong consideration, although metabolic, vascular, infectious, compressive, or neoplastic disease of the spinal cord could also present with similar subacute onset and pattern of deficits.

Her medical history included morbid obesity, dry eyes, depression, iron deficiency anemia requiring recurrent intravenous replenishment, and abnormal uterine bleeding. Her surgical history included gastric band placement 7 years earlier with removal 5 years later due to persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease, dysphagia, nausea, and vomiting. The gastric band removal was complicated by chronic abdominal pain. Her medications consisted of duloxetine, intermittent iron infusions, artificial tears, loratadine, and pregabalin. She was sexually active with her husband. She consumed alcohol occasionally but did not smoke tobacco or use illicit drugs.

On exam, her temperature was 36.6°C (97.8°F), blood pressure 132/84 mm Hg, and heart rate 85 beats per minute. Body mass index was 39.5 kg/m2. The cardiac, pulmonary, and skin examinations were normal. The abdomen was soft with diffuse tenderness to palpation without rebound or guarding. Examination of cranial nerves 2-12 was normal. Cognition, strength, proprioception, deep tendon reflexes, and light touch were all normal. Her gait was normal, and the Romberg test was negative.

The normal neurologic exam is reassuring but imperfectly sensitive and does not eliminate the possibility of underlying neuropathology. Bariatric surgery may result in an array of nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin E, B12, and copper, which can cause myelopathy and/or neuropathy. However, these abnormalities occur less frequently with gastric banding procedures. If her dry eyes are part of the sicca syndrome, an underlying autoimmune diathesis may be present. Her unexplained chronic abdominal pain prompts considering nonmenstrual causes of iron deficiency anemia, such as celiac disease. Bariatric surgery may contribute to iron deficiency through impaired iron absorption. Her stable weight and lack of diarrhea argue against Crohn’s or celiac disease. Iron deficiency predisposes individuals to pica, most commonly described with ice chip ingestion. If lead pica had occurred, abdominal and neurological symptoms could result. Nevertheless, the abdominal pain is nonspecific, and its occurrence after gastric band removal makes its link to her neurologic syndrome unclear. An initial evaluation would include basic metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein (CRP), thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, and copper levels.

A basic metabolic panel was normal. The white cell count was 5,710 per cubic millimeter, hemoglobin level 12.2 g per deciliter, mean corpuscular volume 85.2 fl, and platelet count 279,000 per cubic millimeter. The serum ferritin level was 18 ng per milliliter (normal range, 13-150), iron 28 µg per deciliter (normal range, 50-170), total iron-binding capacity 364 µg per deciliter (normal range, 250-450), and iron saturation 8% (normal range, 20-55). The vitamin B12 level was 621 pg per milliliter (normal range, 232-1,245) and thyroid-stimulating hormone level 1.87 units per milliliter (normal range, 0.50-4.50). Electrolyte and aminotransferase levels were within normal limits. CRP was 1.0 mg per deciliter (normal range, <0.5) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate 33 millimeters per hour (normal range, 4-25). Hepatitis C and HIV antibodies were nonreactive.

The ongoing iron deficiency despite parenteral iron replacement raises the question of ongoing gastrointestinal or genitourinary blood loss. While the level of vitamin B12 in the serum may be misleadingly normal with cobalamin deficiency, a methylmalonic acid level is indicated to evaluate whether tissue stores are depleted. Copper levels are warranted given the prior bariatric surgery. The mild elevations of inflammatory markers are nonspecific but reduce the likelihood of a highly inflammatory process to account for the neurological and abdominal symptoms.

At her 3-month follow-up visit, she noted that the paresthesia had improved and was now limited to her bilateral lower extremities. During the same clinic visit, she experienced a 45-minute episode of ascending left upper extremity numbness. Her physical examination revealed normal strength and reflexes. She had diminished response to pinprick in both legs to the knees and in both hands to the wrists. Vibration sense was diminished in the bilateral lower extremities.

A glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 6.2%. Methylmalonic acid was 69 nmol per liter (normal range, 45-325). Antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum were absent. Impaired glucose metabolism was the leading diagnosis for her polyneuropathy, and it was recommended that she undergo an oral glucose tolerance test. Electromyography was not performed.

The neurological symptoms are now chronic, and importantly, the patient has developed sensory deficits on neurological examination, suggesting worsening of the underlying process. While the paresthesia is now limited to a “stocking/glove” distribution consistent with distal sensory polyneuropathy, there should still be a concern for spinal cord pathology given that the HbA1c level of 6.2 would not explain her initial distribution of symptoms. Myelopathy may mimic peripheral nerve disease if, for example, there is involvement of the dorsal columns leading to sensory deficits of vibration and proprioception. Additionally, the transient episode of upper extremity numbness raises the question of sensory nerve root involvement (ie, sensory radiculopathy). Unexplained abdominal pain could possibly represent the involvement of other nerve roots innervating the abdominal wall. The patient’s episode of focal arm numbness recalls the lancinating radicular pain of tabes dorsalis; however, the negative specific treponemal antibody test excludes neurosyphilis.

The differential diagnosis going forward will be strongly conditioned by the localization of the neurological lesion(s). To differentiate between myelopathy, radiculopathy, and peripheral neuropathy, I would perform nerve conduction studies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spinal cord, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.

The patient began taking a multivitamin, and after weeks her paresthesia had resolved. One month later, she developed an intermittent, throbbing left-sided headache and pain behind the left eye that was worsened with ocular movement. She then noted decreased visual acuity in her left eye that progressed the following month. She denied photophobia, flashers, or floaters.

In the emergency department, visual acuity was 20/25 in her right eye; in the left eye she was only able to count fingers. Extraocular movements of both eyes were normal as was her right pupillary reflex. Red desaturation and a relative afferent papillary defect were present in the left eye. Fundoscopic exam demonstrated left optic disc swelling. The remainder of her cranial nerves were normal. She had pronation of the left upper extremity and mild right finger-to-nose dysmetria. Muscle tone, strength, sensation, and deep tendon reflexes were normal.

The improvement in the sensory symptoms was unlikely to be related to the nutritional intervention and provides a clue to an underlying waxing and waning illness. That interpretation is supported by the subsequent development of new visual symptoms and signs, which point to optic nerve pathology. Optic neuropathy has a broad differential diagnosis that includes ischemic, metabolic, toxic, and compressive causes. Eye pain, swelling of the optic disc, and prominent impairment of color vision all point to the more specific syndrome of optic neuritis caused by infections (including both Treponema pallidum and Borrelia species), systemic autoimmune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome), and central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating diseases. Of these, inflammatory demyelinating processes would be the likeliest explanation of intermittent and improving neurologic findings.

With relapsing symptoms and findings that are separate in distribution and time, two diagnoses become most likely, and both of these are most often diagnosed in young women. MS is common, and optic neuritis occurs in more than 50% of patients over the course of illness. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare condition that can exist in isolation or be associated with other autoimmune illnesses. While these entities are difficult to differentiate clinically, neuroimaging that demonstrates extensive intracerebral demyelinating lesions and cerebrospinal fluid with oligoclonal bands favor MS, whereas extensive, predominant spinal cord involvement is suggestive of NMOSD. Approximately 70% of NMO patients harbor an antibody directed against the aquaporin-4 channel, and these antibodies are not seen in patients with MS. A milder NMO-like disorder has also been associated with antimyelin oligodendrocyte antibodies (MOG).

Testing for antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB) antibodies was negative. The level of C3 was 162 mg per deciliter (normal range 81-157) and C4 38 (normal range 13-39). T-spot testing for latent tuberculosis was negative.

There is no serological evidence of active systemic lupus erythematosus or Sjogren’s syndrome. The pretest probability of CNS tuberculosis was low in light of her presenting complaints, relatively protracted course, and overall clinical stability without antituberculous therapy. Tests for latent tuberculosis infection have significant limitations of both sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of active disease.

Optical coherence tomography showed optic disc edema in the left eye only. MRI of the head with contrast revealed abnormal signal intensity involving the posterior aspect of the pons, right middle cerebellar peduncle, anterior left temporal lobe, bilateral periventricular white matter, subcortical white matter of the frontal lobes bilaterally, and medulla with abnormal signal and enhancement of the left optic nerve (Figure, Panel A). MRI of the cervical and thoracic spine demonstrated multifocal demyelinating lesions at C3, C4, C7, T4, T5, T7, and T8 (Figure, Panel B). The lesions were not longitudinally extensive. There was no significant postcontrast enhancement to suggest active demyelination.

The cerebrospinal fluid analysis revealed glucose of 105 mg per deciliter and a total protein of 26.1 mg per deciliter. In the fourth tube, there were 20 red cells per cubic and four white cells with a differential of 62% neutrophils, 35% lymphocytes, and 3% monocytes. Epstein-Barr and herpes simplex virus DNA were negative. A Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test was negative. Multiple oligoclonal IgG bands were identified only in the cerebrospinal fluid. Aquaporin-4 IgG and MOG antibodies were negative.

In addition to the expected finding of enhancement of the optic nerve, MRI demonstrated numerous multifocal white matter lesions throughout the cerebrum, brainstem, and spinal cord. Many of the lesions were in “silent” areas, which is not directly attributable to specific symptoms, but several did correlate with the subtler deficits of weakness and dysmetria that were noted on examination. Although such lesions may be seen with a diverse group of systemic diseases including adrenal leukodystrophy, sarcoidosis, Behcet’s, cerebral lupus, and vasculitis, primary CNS inflammatory demyelinating diseases are much more likely. The extensive distribution of demyelination argues against NMOSD. The negative aquaporin-4 and MOG assays support this conclusion. Not all multifocal CNS demyelination is caused by MS and can be seen in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy, and adult polyglucosan body disease. Osmotic demyelination is increasingly being recognized as a process that can be more widespread rather than just being limited to the pons. Viral infections of the CNS such as the JC virus (PML) may also provoke multifocal demyelination. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is most often seen during childhood, usually after vaccination or after an infectious prodrome. The tempo of the progression of these other diseases tends to be much more rapid than this woman’s course, and often, the neurological deficits are more profound and debilitating. The clinical presentation of sensory-predominant myelopathy, followed by optic neuritis, absence of systemic inflammatory signs or laboratory markers, exclusion of other relevant diseases, multifocal white matter lesions on imaging, minimal pleocytosis, and presence of oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid, all point to a diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS.

The patient was diagnosed with MS. She was admitted to the neurology service and treated with 1,000 mg IV methylprednisolone for 3 days with a prompt improvement in her vision. She was started on natalizumab without a relapse of symptoms over the past year.

COMMENTARY

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic demyelinating disease of the CNS.1 The diagnosis of MS has classically been based upon compatible clinical and radiographic evidence of pathology that is disseminated in space and time. Patients typically present with an initial clinically isolated syndrome—involving changes in vision, sensation, strength, mobility, or cognition—for which there is radiographic evidence of demyelination.2 A diagnosis of clinically definite MS is then often made based on a subsequent relapse of symptoms.3

An interval from initial symptoms has been central to the diagnosis of MS (“lesions disseminated in time”). However, recent evidence questions this diagnostic paradigm, and a more rapid diagnosis of MS has been recommended. This recommendation is reflected in the updated McDonald criteria, according to which, if a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.4 The importance of such early diagnosis has been supported by numerous studies that have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with early therapy.5-7

Despite the McDonald criteria, delays in definitive diagnosis are common in MS. Patients with MS in Spain were found to experience a 2-year delay from the first onset of symptoms to diagnosis.8 In this cohort, patients exhibited delays in presenting to a healthcare provider, as well as delays in diagnosis with an average time from seeing an initial provider to diagnosis of 6 months. When patients who were referred for a demyelinating episode were surveyed, over a third reported a prior suggestive event.9 The time from the first suggestive episode to referral to a neurologist for a recognized demyelinating event was 46 months. Other studies have shown that delays in diagnosis are especially common in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.10,11

Misapplication of an MS diagnosis also occurs frequently. In one case series, such misapplication was found most often in cases involving migraine, fibromyalgia, psychogenic disorders, and NMOSD.12 NMOSD is distinguished from MS by the presence of typical brain and spine findings on MRI.13 Antibodies to aquaporin-4 are highly specific and moderately sensitive for the disease.14 It is important to distinguish NMOSD from MS as certain disease-modifying drugs used for MS might actually exacerbate NMOSD.15 A lesion that traverses over three or more contiguous vertebral segments with predominant involvement of central gray matter (ie, longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis) on MRI is the most distinct finding of NMOSD. In contrast, similar to our patient, short and often multiple lesions are demonstrated on spinal cord MRI in patients with MS. Sensitive and specific findings of brain MRI in patients with MS include the presence of lateral ventricle and inferior temporal lobe lesion, Dawson’s fingers, central vein sign, or an S-shaped U-fiber lesion. In NMOSD, brain MRI might reveal periependymal lesions surrounding the ventricular system.

This case highlights the diagnostic challenges related to presentations of a waxing and waning neurological process. At the time of the second evaluation, the presentation was interpreted as a length-dependent polyneuropathy due to glucose intolerance. Our patient’s relatively normal HbA1c, subacute onset of neuropathic symptoms (ie, <4 weeks), sensory and motor complaints, and onset in the upper extremities suggested an alternative diagnosis to prediabetes. Once the patient presented with optic neuritis, the cause of the initial symptoms was obvious, but then, hindsight is 20/20.

TEACHING POINTS

- Early treatment of MS results in improved clinical outcomes.

- Delays in the definitive diagnosis of MS are common, especially in younger patients, those with primary progressive MS, and those with comorbid disease.

- If a clinical presentation is supported by the presence of oligoclonal bands in the cerebrospinal fluid, a diagnosis of MS can be made on the basis of radiographic evidence of dissemination of disease in space, without evidence of dissemination in time.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rabih Geha, MD, and Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD, for providing feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript.

1. Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:169-180. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra140148.

2. Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336-1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30959-X.

3. Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622-1636. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30481-1.

4. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

5. Comi G, Radaelli M, Soelberg Sørensen P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1347-1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32388-1.

6. Freedman MS, Comi G, De Stefano N, et al. Moving toward earlier treatment of multiple sclerosis: Findings from a decade of clinical trials and implications for clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(2):147-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2013.07.001.

7. Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536-541. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4905.

8. Fernández O, Fernández V, Arbizu T, et al. Characteristics of multiple sclerosis at onset and delay of diagnosis and treatment in Spain (the Novo Study). J Neurol. 257(9):1500-1507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5560-1.

9. Gout O, Lebrun-Frenay C, Labauge P, et al. Prior suggestive symptoms in one-third of patients consulting for a “first” demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82(3):323-325. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.166421.

10. Kingwell E, Leung A, Roger E, et al. Factors associated with delay to medical recognition in two Canadian multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Neurol Sci. 2010(1-2);292:57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.007.

11. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Comorbidity delays diagnosis and increases disability at diagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2009;72(2):117-124. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000333252.78173.5f.

12. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003152.

13. Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: An international update. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1165-1173. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001367.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177-189. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729.

15. Jacob A, Hutchinson M, Elsone L, et al. Does natalizumab therapy worsen neuromyelitis optica? Neurology. 2012;79(10):1065-1066. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826845fe.

1. Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:169-180. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra140148.

2. Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1336-1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30959-X.

3. Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622-1636. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30481-1.

4. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2.

5. Comi G, Radaelli M, Soelberg Sørensen P. Evolving concepts in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2017;389(10076):1347-1356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32388-1.

6. Freedman MS, Comi G, De Stefano N, et al. Moving toward earlier treatment of multiple sclerosis: Findings from a decade of clinical trials and implications for clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(2):147-155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2013.07.001.

7. Harding K, Williams O, Willis M, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536-541. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4905.

8. Fernández O, Fernández V, Arbizu T, et al. Characteristics of multiple sclerosis at onset and delay of diagnosis and treatment in Spain (the Novo Study). J Neurol. 257(9):1500-1507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-010-5560-1.

9. Gout O, Lebrun-Frenay C, Labauge P, et al. Prior suggestive symptoms in one-third of patients consulting for a “first” demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82(3):323-325. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2008.166421.

10. Kingwell E, Leung A, Roger E, et al. Factors associated with delay to medical recognition in two Canadian multiple sclerosis cohorts. J Neurol Sci. 2010(1-2);292:57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2010.02.007.

11. Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, Tyry T, Campagnolo D, Vollmer T. Comorbidity delays diagnosis and increases disability at diagnosis in MS. Neurology. 2009;72(2):117-124. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000333252.78173.5f.

12. Solomon AJ, Bourdette DN, Cross AH, et al. The contemporary spectrum of multiple sclerosis misdiagnosis: A multicenter study. Neurology. 2016;87(13):1393-1399. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003152.

13. Kim HJ, Paul F, Lana-Peixoto MA, et al. MRI characteristics of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: An international update. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1165-1173. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001367.

14. Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177-189. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001729.

15. Jacob A, Hutchinson M, Elsone L, et al. Does natalizumab therapy worsen neuromyelitis optica? Neurology. 2012;79(10):1065-1066. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826845fe.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Cut to the Quick

A 41‐year‐old woman with dwarfism was referred for evaluation of an isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 792 U/L (normal value, 3195 U/L) and a gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 729 U/L (normal value, 737 U/L), found incidentally on routine laboratory screening. She denied any fevers, chills, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

The presence of an isolated ALP elevation, presumably of hepatobiliary origin given the increase in GGT, in a relatively young woman immediately calls to mind the diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis, and I would specifically inquire about pruritus, which occurs commonly in this setting. The absence of abdominal pain argues against the diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Other processes that could result in this asymptomatic presentation include infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and other causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The absence of systemic symptoms makes disseminated infection or malignancy with hepatic involvement less likely. I would query whether underlying dwarfism can be associated with metabolic abnormalities that cause infiltrative liver disease, functional or anatomical hepatobiliary abnormalities, or malignancy.

The patient's medical history was notable for chronic constipation, allergic rhinitis, and basal‐cell carcinoma. She had reconstructive surgeries of the left hip and knee 28 years ago without complications. She underwent a right total hip replacement for hip dysplasia 6 months prior, which was complicated by a postoperative joint infection with Enterobacter cloacae. The hardware was retained, and she was treated with incision and drainage and a prolonged fluoroquinolone course. Furthermore, she had a history of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), which manifested at the age of 20 years. A bone‐marrow biopsy at that time showed no evidence of hematologic malignancy. For her ITP, she had initially received intravenous immunoglobulin (Ig) and cyclosporine without sustained benefit. She underwent a splenectomy at the age of 26 years and was treated intermittently with rituximab over 11 years prior to admission. Her medications included cetirizine. Her parents were nonconsanguineous, of European and Southeast Asian ancestry, and healthy. She was in a long‐term monogamous relationship. The patient had been employed as an educator.

The history of immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia raises the possibility that the present illness may be part of a broader autoimmune diathesis. Other causes of secondary ITP, such as drug‐induced reactions, hematologic malignancies, and viral infections, are unlikely, as her ITP has been persistent for more than 20 years. She has not evolved into a common phenotypic pattern of autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus after the appearance of ITP, nor does she endorse a history of thromboembolic complications that would suggest antiphospholipid syndrome.

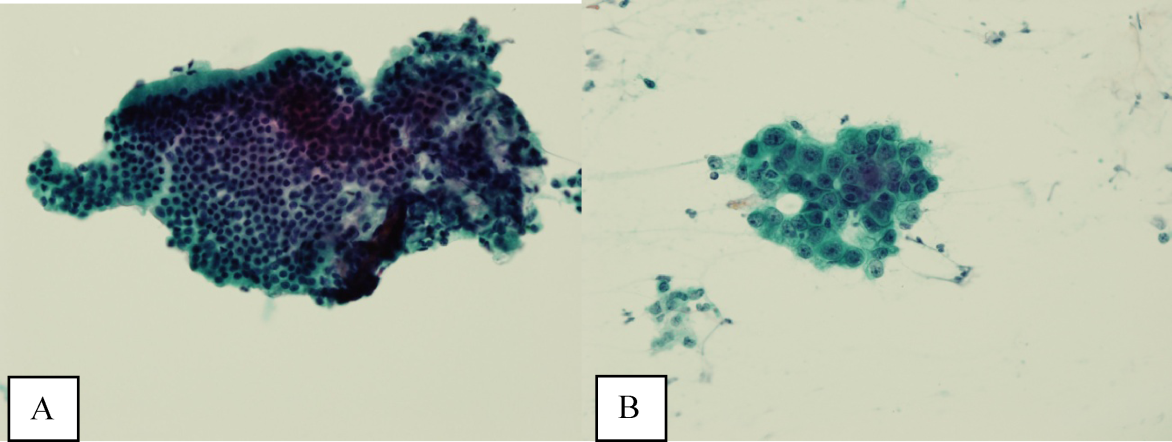

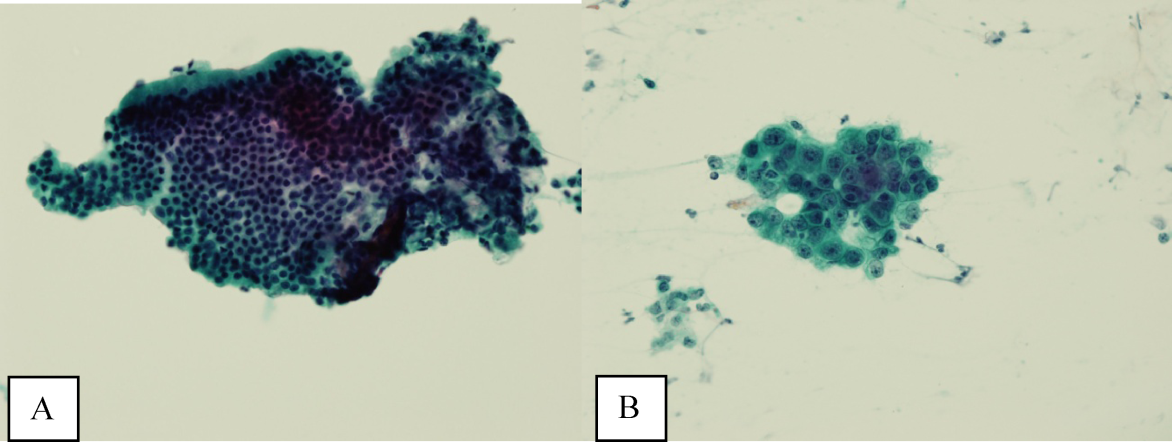

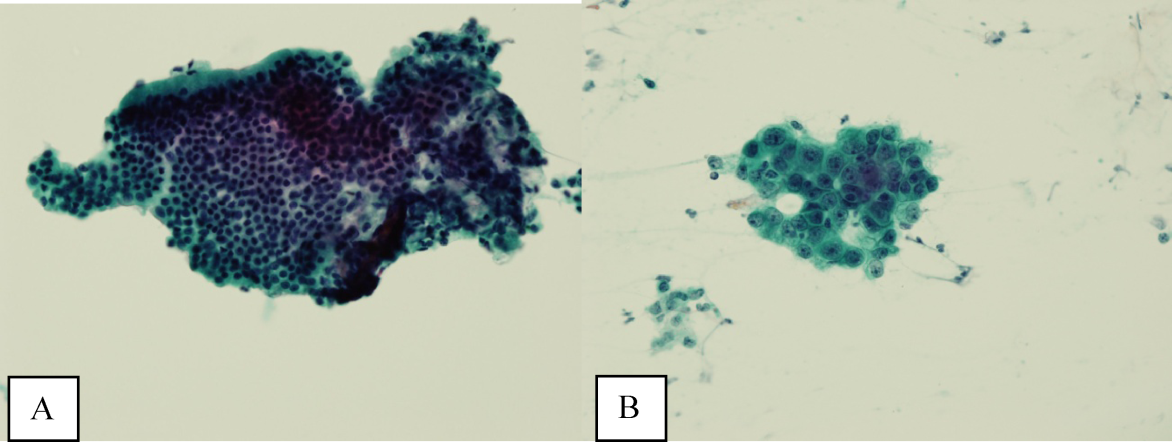

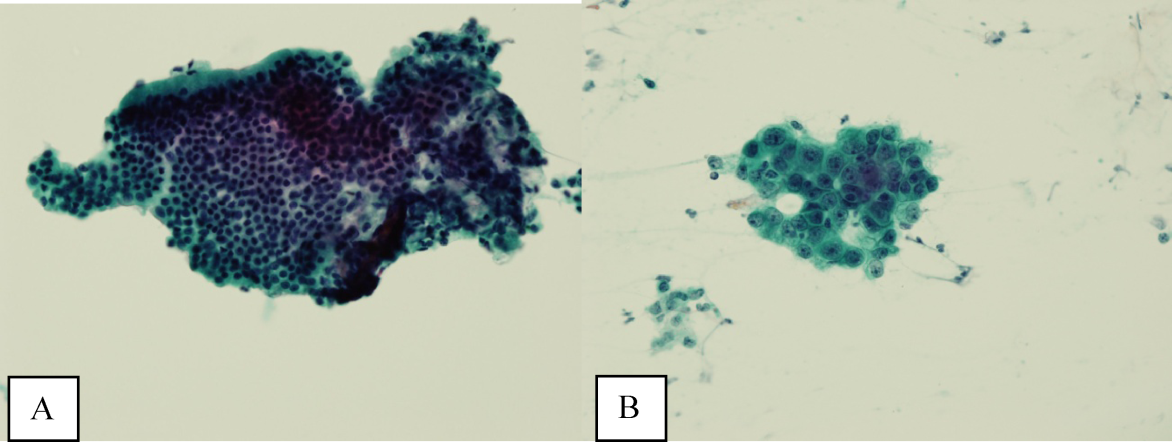

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated narrowing of the extrahepatic biliary duct in the region of the pancreas without evidence of a mass lesion. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis similarly showed mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with narrowing of the extrahepatic duct in the region of the pancreas without apparent pancreatic mass. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) confirmed a stricture in the distal common bile duct and dilatation of the common bile duct. Cytology brushings obtained during ERCP showed groups of overlapping, enlarged cells with pleomorphic irregular nuclei, one or more prominent nucleoli, and focal nuclear molding, leading to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 1).

The absence of jaundice and pruritus indicates incomplete biliary obstruction. Commonbile duct strictures are most commonly seen after manipulation of the biliary tree. Neoplasms including pancreatic cancer, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, and cholangiocarcinoma may cause compression and obstruction of the common bile duct, as well as stricture formation mediated by a desmoplastic reaction to the tumor. Occasionally, metastatic malignancy or lymphoma may involve the porta hepatis and cause extrinsic compression of the common bile duct. Other etiologies of strictures include sclerosing cholangitis and opportunistic infections such as Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, and microsporidiosis, which are not supported by this patient's history.

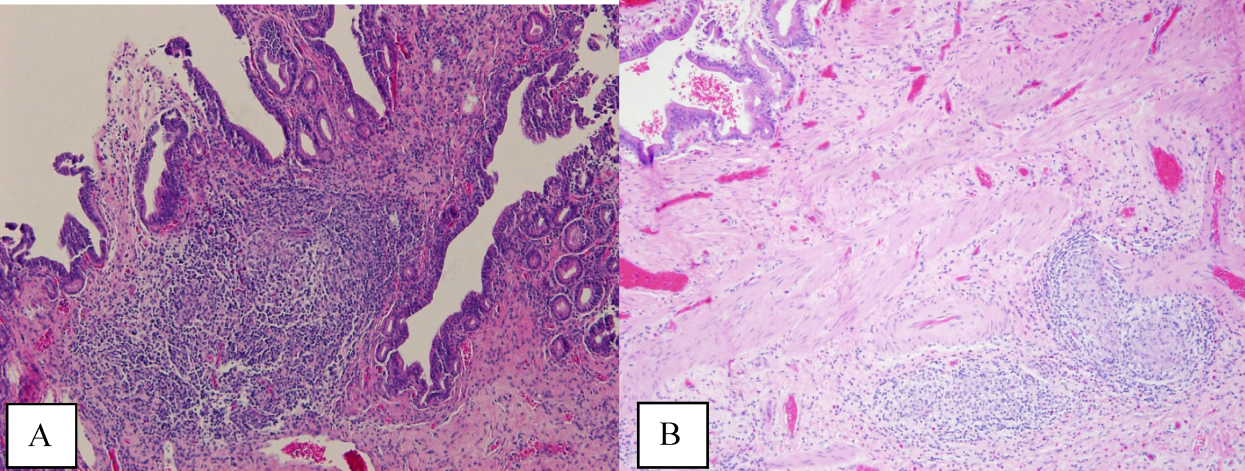

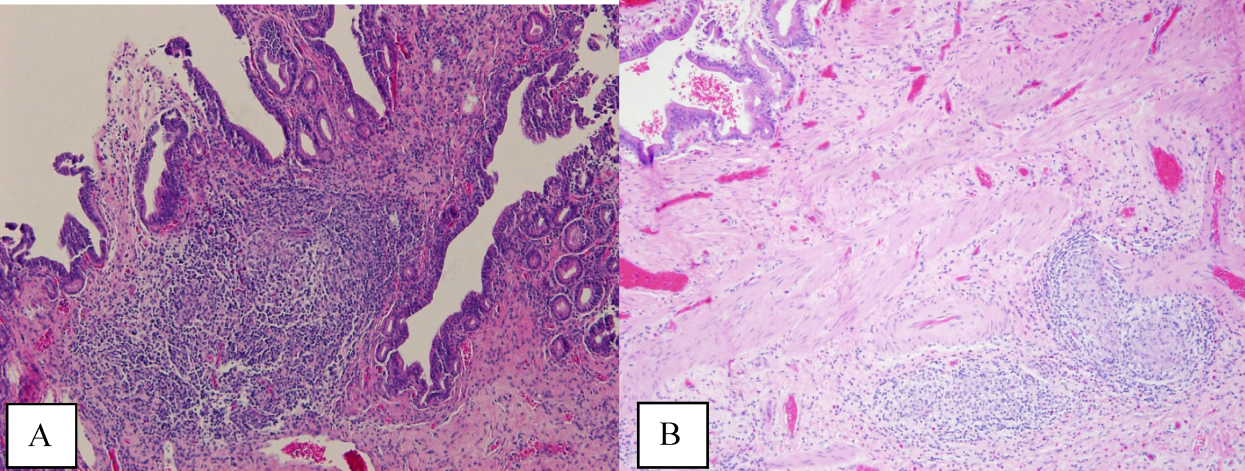

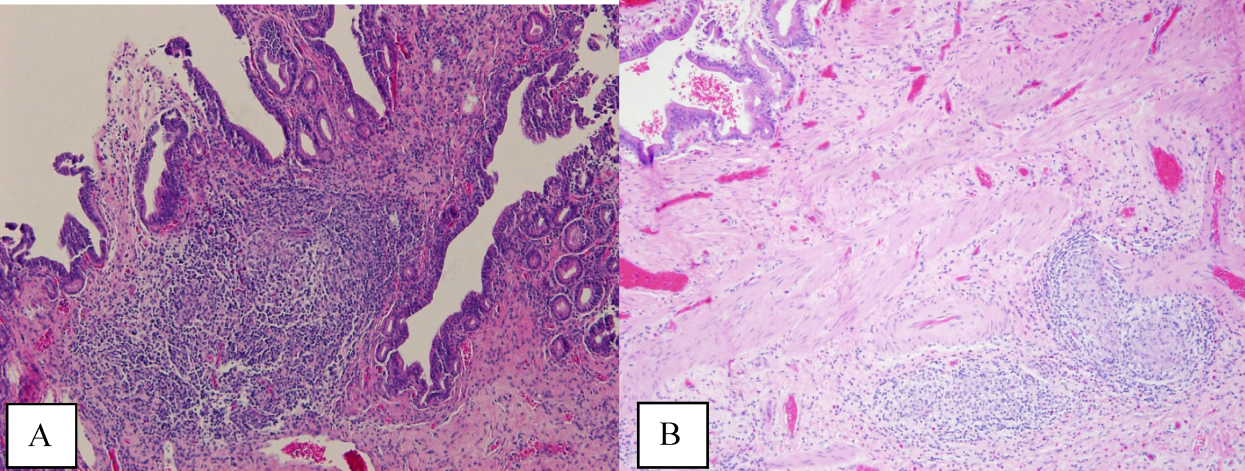

The atypical cells seen on ERCP brushings were interpreted as evidence of cholangiocarcinoma. The patient underwent a pylorus‐sparing Whipple procedure. Examination of the surgical pathology specimens revealed diffuse non‐necrotizing granulomatous inflammation involving the bile duct and gallbladder (Figure 2). There was focal atypia of the bile‐duct epithelial cells, but no evidence of malignancy. There were non‐necrotizing granulomas in numerous lymph nodes, some with significant sclerosis; stains and cultures for acid‐fast bacilli and fungi were negative, and stains for IgG4 and CD1a for Langerhans‐cell histiocytosis were negative.

Granulomatous inflammation may be caused by a variety of intracellular infections, environmental and occupational exposures, and drug hypersensitivity, or may be associated with malignancy such as lymphoma. In the absence of an alternative explanation, the presence of non‐necrotizing granulomas in multiple organs suggests the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, even if classic intrathoracic involvement is not present. Hepatic involvement with sarcoidosis is common but rarely symptomatic, whereas biliary disease is distinctly uncommon. Interestingly, there is an association between both primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis with sarcoidosis. The pathologic findings could indicate an autoimmune process that has led to widespread granulomas with this unusual distribution. Disseminated infections such as mycobacterial or fungal diseases seem much less plausible in this woman, who had no prior systemic complaints. The atypical cells seen on the ERCP brushings were almost certainly caused by inflammation and a fibroproliferative response rather than malignancy.

On further questioning, the patient endorsed a history of multiple childhood ear infections that required bilateral myringotomy tubes, and multiple episodes of sinusitis, but both problems improved in adulthood. She had experienced 2 episodes of dermatomal zoster in her lifetime. She also noted frequent vaginal yeast infections. She denied any history of pneumonias or thrush. In her second decade of life, she developed allergic rhinitis and eczema. She denied any chemical or environmental exposures. She had had negative tuberculin skin tests as part of her occupational screening and denied any recent travel.

The additional history of recurrent upper‐respiratory infections early in life and subsequent episodes of dermatomal zoster and candidal infections increases the likelihood that this patient has a primary immunodeficiency. A combined cellular and humoral immunodeficiency would predispose to both bacterial sinopulmonary infections, generally a result of Ig isotype or IgG subclass deficiencies, and recurrent zoster and candidal infection. Any evaluation of her Igs at this time may be confounded by her receipt of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, which may decrease serum Ig levels.

The relatively benign course in terms of infection is consistent with the heterogeneous immunodeficiencies classified as combined immunodeficiency (CID), a less‐penetrant phenotype of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Autoimmunity is a frequent manifestation of CID and CVID, and affected patients have an increased risk of lymphoma and other malignancies. Granulomatous disease may also be a manifestation of both CID and CVID.

Postoperatively, she developed progressive abdominal distension and pain. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed colonic dilatation consistent with Ogilvie pseudo‐obstruction. On postoperative day 9, she developed fevers. On physical examination, her temperature was 38.5C, the blood pressure was 104/56 mm Hg, and the heart rate was 131 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. Her height was 105 cm. She had diffuse alopecia without scarring. She did not have a malar rash or oral ulcerations. Both lungs were clear to auscultation. A cardiac examination showed tachycardia with a regular rhythm, normal heart sounds, and no murmurs. Her musculoskeletal exam was notable for short limbs and phalanges, without synovitis. Bilateral hip exam demonstrated internal and external range of motion without abnormalities. No rashes were present. Her abdominal exam revealed diffuse tenderness with postoperative drains in place. She had nonbloody loose stools.

Although autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis can rarely manifest with fevers, evaluation of postoperative fever in this patient should focus first on common processes that also occur in immunocompetent patients. Since she has had a splenectomy and we are now suspicious of an underlying immunodeficiency, appropriate cultures should be obtained and broad‐spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated without delay. The presence of nonscarring alopecia could either represent autoimmune alopecia, if the onset was recent, or it could be part of this patient's underlying skeletal dysplasia syndrome.

Piperacillin/tazobactam and oral metronidazole were started for presumed intra‐abdominal infection. The white cell count was 20,500/mm3 with 96% neutrophils, 1.4% lymphocytes with an absolute lymphocyte count 0.33 109/L (normal value, >1.0 109/L), and 2.6% monocytes. The hematocrit was 27.8% with a mean corpuscular volume of 95 fL. The platelet count was 323,000/mm3. Serum aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels were normal, and ALP was 904 U/L. The serum albumin was 1.2 g/dL (normal value, 3.54.8 g/dL) and prealbumin was 6 mg/dL (normal value, 2037 mg/dL).

Blood cultures returned positive for E. cloacae. Clostridium difficile toxin assay was negative. Piperacillin/tazobactam was switched to meroperem, and metronidazole was discontinued. She continued to have fevers, and on postoperative day 16, repeat blood cultures and urine cultures grew Candida albicans; caspofungin was initiated.

In addition to the neutrophilic leukocytosis in response to gram‐negative bacteremia, there is marked lymphopenia. Although sepsis may cause transient declines in the total lymphocyte count, I do not believe that this entirely accounts for such severe lymphopenia. The albumin is also profoundly low. Her catabolic postsurgical state might explain part of this abnormality, but taken together with her prior gastrointestinal symptoms, these findings could be consistent with intestinal malabsorption or a protein‐losing enteropathy, which can also be associated with primary immunodeficiency.

Serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme was 32 U/L (normal value, 967 U/L). A CT of the chest was performed and did not reveal mediastinal lymphadenopathy, nodules, or consolidations. Antinuclear, antismooth muscle, and antimitochondrial antibodies were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody was negative. Serum quantitative Igs, including IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE, were undetectable.

Serum lymphocyte subset analysis revealed a CD3 T‐cell count of 101 106/L (normal value, >690 106/L), CD4 T cells 46 106/L (normal value, >410 106/L), CD8 T cells 55 106/L (normal value, >190 106/L), CD19 B cells undetectable at <2 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L), CD16 CD56 NK cells 134 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L). T‐cell lymphocyte proliferation assay showed a completely absent response to candida and tetanus antigens, and a very low response to mitogens.

The immunologic evaluation is confounded by her critical illness and by the prior administration of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody. Despite these caveats, the results of these studies are profoundly abnormal and suggest a combined B‐cell and T‐cell immunodeficiency that is more severe from a laboratory standpoint than her history prior to surgery has suggested. Low T lymphocyte numbers, with or without functional abnormalities, are a hallmark of CID and can be also be seen in CVID. The extremely low Ig levels in the presence of severe infections warrant replacement with intravenous Ig.

Combined immunodeficiency and CVID may be associated with a number of mutations; elucidating the genetics and molecular mechanism of immunodeficiency may be important in identifying patients whose immunodeficiency may be cured by stem‐cell transplantation.

Intravenous Ig was administered. Her serum was sent for sequencing of the RMRP gene, mutations of which are found in patients who have cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH), a rare autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia characterized by short‐limbed dwarfism; fine, sparse hair; and variable degrees of immunodeficiency. She was found to have 2 RMRP mutations, a 126 CT transition and a 218 AC transversion.

The patient developed multiple abdominal abscesses, which were drained and grew vancomycin‐resistant enterococcus (VRE) and C. albicans. Blood cultures also turned positive for VRE. A colonoscopy was performed because of radiographic evidence suggestive of colitis. Biopsies taken from the colonoscopy were negative for cytomegalovirus or other infections, but did reveal rare non‐necrotizing granulomas. The patient developed progressive multiorgan failure requiring mechanical ventilation and continuous venovenous hemofiltration. On postoperative day 36, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she expired the next day. A unifying diagnosis of CHH‐related immunodeficiency and disseminated granulomatous disease, complicated by postoperative sepsis, was made. An autopsy was declined.

COMMENTARY