User login

Neuroimaging in psychiatry: Potentials and pitfalls

Advances in neuroimaging over the past 25 years have allowed for an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the structural and functional brain abnormalities associated with psychiatric disease.1 It has been postulated that a better understanding of aberrant brain circuitry in psychiatric illness will be critical for transforming the diagnosis and treatment of these illnesses.2 In fact, in 2008, the National Institute of Mental Health launched the Research Domain Criteria project to reformulate psychiatric diagnosis based on biologic underpinnings.3

In the midst of these scientific advances and the increased availability of neuroimaging, some private clinics have begun to offer routine brain scans as part of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation.4-7 These clinics suggest that single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the brain can provide objective, reliable psychiatric diagnoses. Unfortunately, using SPECT for psychiatric diagnosis lacks empirical support and carries risks, including exposing patients to radioisotopes and detracting from empirically validated treatments.8 Nonetheless, given the current diagnostic challenges in psychiatry, it is understandable that patients, parents, and clinicians alike have reported high receptivity to the use of neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis and treatment planning.9

While neuroimaging is central to the search for improved understanding of the biologic foundations of mental illness, progress in identifying biomarkers has been disappointing. There are currently no neuroimaging biomarkers that can reliably distinguish patients from controls, and no empirical evidence supports the use of neuroimaging in diagnosing psychiatric conditions.10 The current standard of clinical care is to use neuroimaging to diagnose neurologic diseases that are masquerading as psychiatric disorders. However, given the rapid advances and availability of this technology, determining if and when neuroimaging is clinically indicated will likely soon become increasingly complex. Prior to the widespread availability of this technology, it is worth considering the potential advantages and pitfalls to the adoption of neuroimaging in psychiatry. In this article, we:

- outline arguments that support the use of neuroimaging in psychiatry, and some of the limitations

- discuss special considerations for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and forensic psychiatry

- suggest guidelines for best-practice models based on the current evidence.

Advantages of widespread use of neuroimaging in psychiatry

Currently, neuroimaging is used in psychiatry to rule out neurologic disorders such as seizures, tumors, or infectious illness that might be causing psychiatric symptoms. If neuroimaging were routinely used for this purpose, one theoretical advantage would be increased neurologic diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, increased adoption of neuroimaging may eventually help broaden the phenotype of neurologic disorders. In other words, psychiatric symptoms may be more common in neurologic disorders than we currently recognize. A second advantage might be that early and definitive exclusion of a structural neurologic disorder may help patients and families more readily accept a psychiatric diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

In the future, if biomarkers of psychiatric illness are discerned, using neuroimaging for diagnosis, assessment, and treatment planning may help increase objectivity and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness. Currently, psychiatric diagnoses are based on emotional and behavioral self-report and clinical observations. It is not uncommon for patients to receive different diagnoses and even conflicting recommendations from different clinicians. Tools that aid objective diagnosis will likely improve the reliability of the diagnosis and help in assessing treatment response. Also, concrete biomarkers that respond to treatment may help align psychiatric disorders with other medical illnesses, thereby decreasing stigma.

Cautions against routine neuroimaging

There are several potential pitfalls to the routine use of neuroimaging in psychiatry. First, clinical psychiatry is centered on clinical acumen and the doctor–patient relationship. Many psychiatric clinicians are not accustomed to using lab measures or tests to support the diagnostic process or treatment planning. Psychiatrists may be resistant to technologies that threaten clinical acumen, the power of the therapeutic relationship, and the value of getting to know patients over time.11 Overreliance on neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis also carries the risk of becoming overly reductionistic. This approach may overemphasize the biologic aspects of mental illness, while excluding social and psychological factors that may be responsive to treatment.

Second, the widespread use of neuroimaging is likely to result in many incidental findings. This is especially relevant because abnormality does not establish causality. Incidental findings may cause unnecessary anxiety for patients and families, particularly if there are minimal treatment options.

Continue to: Third, it remains unclear...

Third, it remains unclear whether widespread neuroimaging in psychiatry will be cost-effective. Unless imaging results are tied to effective treatments, neuroimaging is unlikely to result in cost savings. Presently, patients who can afford out-of-pocket care might be able to access neuroimaging. If neuroimaging were shown to improve clinical outcomes but remains costly, this unequal distribution of resources would create an ethical quandary.

Finally, neuroimaging is complex and almost certainly not as objective as one might hope. Interpreting images will require specialized knowledge and skills that are beyond those of currently certified general psychiatrists.12 Because there is a great deal of overlap in brain anomalies across psychiatric illnesses, it is unclear whether using neuroimaging for diagnostic purposes will eclipse a thorough clinical assessment. For example, the amygdala and insula show activation across a range of anxiety disorders. Abnormal amygdala activation has also been reported in depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and psychopathy.13

In addition, psychiatric comorbidity is common. It is unclear how much neuroimaging will add diagnostically when a patient presents with multiple psychiatric disorders. Comorbidity of psychiatric and neurologic disorders also is common. A neurologic illness that is detectable by structural neuroimaging does not necessarily exclude the presence of a psychiatric disorder. This poses yet another challenge to developing reliable, valid neuroimaging techniques for clinical use.

Areas of controversy

First-episode psychosis. Current practice guidelines for neuroimaging in patients with FEP are inconsistent. The Canadian Choosing Wisely Guidelines recommend against routinely ordering neuroimaging in first-episode psychoses in the absence of signs or symptoms that suggest intracranial pathology.14 Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends ordering neuroimaging in patients for whom the clinical picture is unclear or when examination reveals abnormal findings.15 In contrast, the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis recommend that all patients with FEP receive brain MRI.16 Freudenreich et al17 describe 2 philosophies regarding the initial medical workup of FEP: (1) a comprehensive medical workup requires extensive testing, and (2) in their natural histories, most illnesses eventually declare themselves.

Despite this inconsistency, the overall evidence does not seem to support routine brain imaging for patients with FEP in the absence of neurologic or cognitive impairment. A systematic review of 16 studies assessing the clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in FEP found that there was “insufficient evidence to suggest that brain imaging should be routinely ordered for patients presenting with first-episode psychosis without associated neurological or cognitive impairment.”18

Continue to: Forensic psychiatry

Forensic psychiatry. Two academic disciplines—neuroethics and neurolaw—attempt to study how medications and neuroimaging could impact forensic psychiatry.19 And in this golden age of neuroscience, psychiatrists specializing in forensics may be increasingly asked to opine on brain scans. This requires specific thoughtfulness and attention because forensic psychiatrists must “distinguish neuroscience from neuro-nonsense.”20 These specialists will need to consider the Daubert standard, which resulted from the 1993 case Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.21 In this case, the US Supreme Court ruled that evidence must be “‘generally accepted’ as reliable in the relevant scientific community” to be admissible. According to the Daubert standard, “evidentiary reliability” is based on scientific validity.21

How should we use neuroimaging?

While neuroimaging is a quickly evolving research tool, empirical support for its clinical use remains limited. The hope is that future neuroimaging research will yield biomarker profiles for mental illness, identification of risk factors, and predictors of vulnerability and treatment response, which will allow for more targeted treatments.1

The current standard of clinical care for using neuroimaging in psychiatry is to diagnose neurologic diseases. Although there are no consensus guidelines for when to order imaging, it is reasonable to consider imaging when a patient has22:

- abrupt onset of symptoms

- change in level of consciousness

- deficits in neurologic or cognitive examination

- a history of head trauma (with loss of consciousness), whole-brain radiation, neurologic comorbidities, or cancer

- late onset of symptoms (age >50)

- atypical presentation of psychiatric illness.

1. Silbersweig DA, Rauch SL. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: a quarter century of progress. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25(5):195-197.

2. Insel TR, Wang PS. Rethinking mental illness. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1970-1971.

3. Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Endophenotypes: bridging genomic complexity and disorder heterogeneity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):988-989.

4. Cyranoski D. Neuroscience: thought experiment. Nature. 2011;469:148-149.

5. Amen Clinics. https://www.amenclinics.com/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

6. Pathfinder Brain SPECT Imaging. https://pathfinder.md/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

7. DrSpectScan. http://www.drspectscan.org/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

8. Adinoff B, Devous M. Scientifically unfounded claims in diagnosing and treating patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):598.

9. Borgelt EL, Buchman DZ, Illes J. Neuroimaging in mental health care: voices in translation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:293.

10. Linden DEJ. The challenges and promise of neuroimaging in psychiatry. Neuron. 2012;73(1):8-22.

11. Macqueen GM. Will there be a role for neuroimaging in clinical psychiatry? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35(5):291-293.

12. Boyce AC. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: evaluating the ethical consequences for patient care. Bioethics. 2009;23(6):349-359.

13. Farah MJ, Gillihan SJ. Diagnostic brain imaging in psychiatry: current uses and future prospects. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(6):464-471.

14. Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, et al. Thirteen things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Canada. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Psychiatry.pdf. Updated June 2017. Accessed October 22, 2019.

15. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

16. Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis. 2nd edition. The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. https://www.orygen.org.au/Campus/Expert-Network/Resources/Free/Clinical-Practice/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis.aspx?ext=. Updated 2016. Accessed October 22, 2019.

17. Freudenreich O, Schulz SC, Goff DC. Initial medical work-up of first-episode psychosis: a conceptual review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(1):10-18.

18. Forbes M, Stefler D, Velakoulis D, et al. The clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019:000486741984803. doi: 10.1177/0004867419848035.

19. Aggarwal N. Neuroimaging, culture, and forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(2):239-244

20. Choi O. What neuroscience can and cannot answer. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(3):278-285.

21. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 509 US 579 (1993).

22. Camprodon JA, Stern TA. Selecting neuroimaging techniques: a review for the clinician. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):PCC.12f01490. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12f01490.

Advances in neuroimaging over the past 25 years have allowed for an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the structural and functional brain abnormalities associated with psychiatric disease.1 It has been postulated that a better understanding of aberrant brain circuitry in psychiatric illness will be critical for transforming the diagnosis and treatment of these illnesses.2 In fact, in 2008, the National Institute of Mental Health launched the Research Domain Criteria project to reformulate psychiatric diagnosis based on biologic underpinnings.3

In the midst of these scientific advances and the increased availability of neuroimaging, some private clinics have begun to offer routine brain scans as part of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation.4-7 These clinics suggest that single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the brain can provide objective, reliable psychiatric diagnoses. Unfortunately, using SPECT for psychiatric diagnosis lacks empirical support and carries risks, including exposing patients to radioisotopes and detracting from empirically validated treatments.8 Nonetheless, given the current diagnostic challenges in psychiatry, it is understandable that patients, parents, and clinicians alike have reported high receptivity to the use of neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis and treatment planning.9

While neuroimaging is central to the search for improved understanding of the biologic foundations of mental illness, progress in identifying biomarkers has been disappointing. There are currently no neuroimaging biomarkers that can reliably distinguish patients from controls, and no empirical evidence supports the use of neuroimaging in diagnosing psychiatric conditions.10 The current standard of clinical care is to use neuroimaging to diagnose neurologic diseases that are masquerading as psychiatric disorders. However, given the rapid advances and availability of this technology, determining if and when neuroimaging is clinically indicated will likely soon become increasingly complex. Prior to the widespread availability of this technology, it is worth considering the potential advantages and pitfalls to the adoption of neuroimaging in psychiatry. In this article, we:

- outline arguments that support the use of neuroimaging in psychiatry, and some of the limitations

- discuss special considerations for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and forensic psychiatry

- suggest guidelines for best-practice models based on the current evidence.

Advantages of widespread use of neuroimaging in psychiatry

Currently, neuroimaging is used in psychiatry to rule out neurologic disorders such as seizures, tumors, or infectious illness that might be causing psychiatric symptoms. If neuroimaging were routinely used for this purpose, one theoretical advantage would be increased neurologic diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, increased adoption of neuroimaging may eventually help broaden the phenotype of neurologic disorders. In other words, psychiatric symptoms may be more common in neurologic disorders than we currently recognize. A second advantage might be that early and definitive exclusion of a structural neurologic disorder may help patients and families more readily accept a psychiatric diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

In the future, if biomarkers of psychiatric illness are discerned, using neuroimaging for diagnosis, assessment, and treatment planning may help increase objectivity and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness. Currently, psychiatric diagnoses are based on emotional and behavioral self-report and clinical observations. It is not uncommon for patients to receive different diagnoses and even conflicting recommendations from different clinicians. Tools that aid objective diagnosis will likely improve the reliability of the diagnosis and help in assessing treatment response. Also, concrete biomarkers that respond to treatment may help align psychiatric disorders with other medical illnesses, thereby decreasing stigma.

Cautions against routine neuroimaging

There are several potential pitfalls to the routine use of neuroimaging in psychiatry. First, clinical psychiatry is centered on clinical acumen and the doctor–patient relationship. Many psychiatric clinicians are not accustomed to using lab measures or tests to support the diagnostic process or treatment planning. Psychiatrists may be resistant to technologies that threaten clinical acumen, the power of the therapeutic relationship, and the value of getting to know patients over time.11 Overreliance on neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis also carries the risk of becoming overly reductionistic. This approach may overemphasize the biologic aspects of mental illness, while excluding social and psychological factors that may be responsive to treatment.

Second, the widespread use of neuroimaging is likely to result in many incidental findings. This is especially relevant because abnormality does not establish causality. Incidental findings may cause unnecessary anxiety for patients and families, particularly if there are minimal treatment options.

Continue to: Third, it remains unclear...

Third, it remains unclear whether widespread neuroimaging in psychiatry will be cost-effective. Unless imaging results are tied to effective treatments, neuroimaging is unlikely to result in cost savings. Presently, patients who can afford out-of-pocket care might be able to access neuroimaging. If neuroimaging were shown to improve clinical outcomes but remains costly, this unequal distribution of resources would create an ethical quandary.

Finally, neuroimaging is complex and almost certainly not as objective as one might hope. Interpreting images will require specialized knowledge and skills that are beyond those of currently certified general psychiatrists.12 Because there is a great deal of overlap in brain anomalies across psychiatric illnesses, it is unclear whether using neuroimaging for diagnostic purposes will eclipse a thorough clinical assessment. For example, the amygdala and insula show activation across a range of anxiety disorders. Abnormal amygdala activation has also been reported in depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and psychopathy.13

In addition, psychiatric comorbidity is common. It is unclear how much neuroimaging will add diagnostically when a patient presents with multiple psychiatric disorders. Comorbidity of psychiatric and neurologic disorders also is common. A neurologic illness that is detectable by structural neuroimaging does not necessarily exclude the presence of a psychiatric disorder. This poses yet another challenge to developing reliable, valid neuroimaging techniques for clinical use.

Areas of controversy

First-episode psychosis. Current practice guidelines for neuroimaging in patients with FEP are inconsistent. The Canadian Choosing Wisely Guidelines recommend against routinely ordering neuroimaging in first-episode psychoses in the absence of signs or symptoms that suggest intracranial pathology.14 Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends ordering neuroimaging in patients for whom the clinical picture is unclear or when examination reveals abnormal findings.15 In contrast, the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis recommend that all patients with FEP receive brain MRI.16 Freudenreich et al17 describe 2 philosophies regarding the initial medical workup of FEP: (1) a comprehensive medical workup requires extensive testing, and (2) in their natural histories, most illnesses eventually declare themselves.

Despite this inconsistency, the overall evidence does not seem to support routine brain imaging for patients with FEP in the absence of neurologic or cognitive impairment. A systematic review of 16 studies assessing the clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in FEP found that there was “insufficient evidence to suggest that brain imaging should be routinely ordered for patients presenting with first-episode psychosis without associated neurological or cognitive impairment.”18

Continue to: Forensic psychiatry

Forensic psychiatry. Two academic disciplines—neuroethics and neurolaw—attempt to study how medications and neuroimaging could impact forensic psychiatry.19 And in this golden age of neuroscience, psychiatrists specializing in forensics may be increasingly asked to opine on brain scans. This requires specific thoughtfulness and attention because forensic psychiatrists must “distinguish neuroscience from neuro-nonsense.”20 These specialists will need to consider the Daubert standard, which resulted from the 1993 case Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.21 In this case, the US Supreme Court ruled that evidence must be “‘generally accepted’ as reliable in the relevant scientific community” to be admissible. According to the Daubert standard, “evidentiary reliability” is based on scientific validity.21

How should we use neuroimaging?

While neuroimaging is a quickly evolving research tool, empirical support for its clinical use remains limited. The hope is that future neuroimaging research will yield biomarker profiles for mental illness, identification of risk factors, and predictors of vulnerability and treatment response, which will allow for more targeted treatments.1

The current standard of clinical care for using neuroimaging in psychiatry is to diagnose neurologic diseases. Although there are no consensus guidelines for when to order imaging, it is reasonable to consider imaging when a patient has22:

- abrupt onset of symptoms

- change in level of consciousness

- deficits in neurologic or cognitive examination

- a history of head trauma (with loss of consciousness), whole-brain radiation, neurologic comorbidities, or cancer

- late onset of symptoms (age >50)

- atypical presentation of psychiatric illness.

Advances in neuroimaging over the past 25 years have allowed for an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the structural and functional brain abnormalities associated with psychiatric disease.1 It has been postulated that a better understanding of aberrant brain circuitry in psychiatric illness will be critical for transforming the diagnosis and treatment of these illnesses.2 In fact, in 2008, the National Institute of Mental Health launched the Research Domain Criteria project to reformulate psychiatric diagnosis based on biologic underpinnings.3

In the midst of these scientific advances and the increased availability of neuroimaging, some private clinics have begun to offer routine brain scans as part of a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation.4-7 These clinics suggest that single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the brain can provide objective, reliable psychiatric diagnoses. Unfortunately, using SPECT for psychiatric diagnosis lacks empirical support and carries risks, including exposing patients to radioisotopes and detracting from empirically validated treatments.8 Nonetheless, given the current diagnostic challenges in psychiatry, it is understandable that patients, parents, and clinicians alike have reported high receptivity to the use of neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis and treatment planning.9

While neuroimaging is central to the search for improved understanding of the biologic foundations of mental illness, progress in identifying biomarkers has been disappointing. There are currently no neuroimaging biomarkers that can reliably distinguish patients from controls, and no empirical evidence supports the use of neuroimaging in diagnosing psychiatric conditions.10 The current standard of clinical care is to use neuroimaging to diagnose neurologic diseases that are masquerading as psychiatric disorders. However, given the rapid advances and availability of this technology, determining if and when neuroimaging is clinically indicated will likely soon become increasingly complex. Prior to the widespread availability of this technology, it is worth considering the potential advantages and pitfalls to the adoption of neuroimaging in psychiatry. In this article, we:

- outline arguments that support the use of neuroimaging in psychiatry, and some of the limitations

- discuss special considerations for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) and forensic psychiatry

- suggest guidelines for best-practice models based on the current evidence.

Advantages of widespread use of neuroimaging in psychiatry

Currently, neuroimaging is used in psychiatry to rule out neurologic disorders such as seizures, tumors, or infectious illness that might be causing psychiatric symptoms. If neuroimaging were routinely used for this purpose, one theoretical advantage would be increased neurologic diagnostic accuracy. Furthermore, increased adoption of neuroimaging may eventually help broaden the phenotype of neurologic disorders. In other words, psychiatric symptoms may be more common in neurologic disorders than we currently recognize. A second advantage might be that early and definitive exclusion of a structural neurologic disorder may help patients and families more readily accept a psychiatric diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

In the future, if biomarkers of psychiatric illness are discerned, using neuroimaging for diagnosis, assessment, and treatment planning may help increase objectivity and reduce the stigma associated with mental illness. Currently, psychiatric diagnoses are based on emotional and behavioral self-report and clinical observations. It is not uncommon for patients to receive different diagnoses and even conflicting recommendations from different clinicians. Tools that aid objective diagnosis will likely improve the reliability of the diagnosis and help in assessing treatment response. Also, concrete biomarkers that respond to treatment may help align psychiatric disorders with other medical illnesses, thereby decreasing stigma.

Cautions against routine neuroimaging

There are several potential pitfalls to the routine use of neuroimaging in psychiatry. First, clinical psychiatry is centered on clinical acumen and the doctor–patient relationship. Many psychiatric clinicians are not accustomed to using lab measures or tests to support the diagnostic process or treatment planning. Psychiatrists may be resistant to technologies that threaten clinical acumen, the power of the therapeutic relationship, and the value of getting to know patients over time.11 Overreliance on neuroimaging for psychiatric diagnosis also carries the risk of becoming overly reductionistic. This approach may overemphasize the biologic aspects of mental illness, while excluding social and psychological factors that may be responsive to treatment.

Second, the widespread use of neuroimaging is likely to result in many incidental findings. This is especially relevant because abnormality does not establish causality. Incidental findings may cause unnecessary anxiety for patients and families, particularly if there are minimal treatment options.

Continue to: Third, it remains unclear...

Third, it remains unclear whether widespread neuroimaging in psychiatry will be cost-effective. Unless imaging results are tied to effective treatments, neuroimaging is unlikely to result in cost savings. Presently, patients who can afford out-of-pocket care might be able to access neuroimaging. If neuroimaging were shown to improve clinical outcomes but remains costly, this unequal distribution of resources would create an ethical quandary.

Finally, neuroimaging is complex and almost certainly not as objective as one might hope. Interpreting images will require specialized knowledge and skills that are beyond those of currently certified general psychiatrists.12 Because there is a great deal of overlap in brain anomalies across psychiatric illnesses, it is unclear whether using neuroimaging for diagnostic purposes will eclipse a thorough clinical assessment. For example, the amygdala and insula show activation across a range of anxiety disorders. Abnormal amygdala activation has also been reported in depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and psychopathy.13

In addition, psychiatric comorbidity is common. It is unclear how much neuroimaging will add diagnostically when a patient presents with multiple psychiatric disorders. Comorbidity of psychiatric and neurologic disorders also is common. A neurologic illness that is detectable by structural neuroimaging does not necessarily exclude the presence of a psychiatric disorder. This poses yet another challenge to developing reliable, valid neuroimaging techniques for clinical use.

Areas of controversy

First-episode psychosis. Current practice guidelines for neuroimaging in patients with FEP are inconsistent. The Canadian Choosing Wisely Guidelines recommend against routinely ordering neuroimaging in first-episode psychoses in the absence of signs or symptoms that suggest intracranial pathology.14 Similarly, the American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia recommends ordering neuroimaging in patients for whom the clinical picture is unclear or when examination reveals abnormal findings.15 In contrast, the Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis recommend that all patients with FEP receive brain MRI.16 Freudenreich et al17 describe 2 philosophies regarding the initial medical workup of FEP: (1) a comprehensive medical workup requires extensive testing, and (2) in their natural histories, most illnesses eventually declare themselves.

Despite this inconsistency, the overall evidence does not seem to support routine brain imaging for patients with FEP in the absence of neurologic or cognitive impairment. A systematic review of 16 studies assessing the clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in FEP found that there was “insufficient evidence to suggest that brain imaging should be routinely ordered for patients presenting with first-episode psychosis without associated neurological or cognitive impairment.”18

Continue to: Forensic psychiatry

Forensic psychiatry. Two academic disciplines—neuroethics and neurolaw—attempt to study how medications and neuroimaging could impact forensic psychiatry.19 And in this golden age of neuroscience, psychiatrists specializing in forensics may be increasingly asked to opine on brain scans. This requires specific thoughtfulness and attention because forensic psychiatrists must “distinguish neuroscience from neuro-nonsense.”20 These specialists will need to consider the Daubert standard, which resulted from the 1993 case Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.21 In this case, the US Supreme Court ruled that evidence must be “‘generally accepted’ as reliable in the relevant scientific community” to be admissible. According to the Daubert standard, “evidentiary reliability” is based on scientific validity.21

How should we use neuroimaging?

While neuroimaging is a quickly evolving research tool, empirical support for its clinical use remains limited. The hope is that future neuroimaging research will yield biomarker profiles for mental illness, identification of risk factors, and predictors of vulnerability and treatment response, which will allow for more targeted treatments.1

The current standard of clinical care for using neuroimaging in psychiatry is to diagnose neurologic diseases. Although there are no consensus guidelines for when to order imaging, it is reasonable to consider imaging when a patient has22:

- abrupt onset of symptoms

- change in level of consciousness

- deficits in neurologic or cognitive examination

- a history of head trauma (with loss of consciousness), whole-brain radiation, neurologic comorbidities, or cancer

- late onset of symptoms (age >50)

- atypical presentation of psychiatric illness.

1. Silbersweig DA, Rauch SL. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: a quarter century of progress. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25(5):195-197.

2. Insel TR, Wang PS. Rethinking mental illness. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1970-1971.

3. Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Endophenotypes: bridging genomic complexity and disorder heterogeneity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):988-989.

4. Cyranoski D. Neuroscience: thought experiment. Nature. 2011;469:148-149.

5. Amen Clinics. https://www.amenclinics.com/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

6. Pathfinder Brain SPECT Imaging. https://pathfinder.md/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

7. DrSpectScan. http://www.drspectscan.org/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

8. Adinoff B, Devous M. Scientifically unfounded claims in diagnosing and treating patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):598.

9. Borgelt EL, Buchman DZ, Illes J. Neuroimaging in mental health care: voices in translation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:293.

10. Linden DEJ. The challenges and promise of neuroimaging in psychiatry. Neuron. 2012;73(1):8-22.

11. Macqueen GM. Will there be a role for neuroimaging in clinical psychiatry? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35(5):291-293.

12. Boyce AC. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: evaluating the ethical consequences for patient care. Bioethics. 2009;23(6):349-359.

13. Farah MJ, Gillihan SJ. Diagnostic brain imaging in psychiatry: current uses and future prospects. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(6):464-471.

14. Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, et al. Thirteen things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Canada. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Psychiatry.pdf. Updated June 2017. Accessed October 22, 2019.

15. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

16. Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis. 2nd edition. The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. https://www.orygen.org.au/Campus/Expert-Network/Resources/Free/Clinical-Practice/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis.aspx?ext=. Updated 2016. Accessed October 22, 2019.

17. Freudenreich O, Schulz SC, Goff DC. Initial medical work-up of first-episode psychosis: a conceptual review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(1):10-18.

18. Forbes M, Stefler D, Velakoulis D, et al. The clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019:000486741984803. doi: 10.1177/0004867419848035.

19. Aggarwal N. Neuroimaging, culture, and forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(2):239-244

20. Choi O. What neuroscience can and cannot answer. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(3):278-285.

21. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 509 US 579 (1993).

22. Camprodon JA, Stern TA. Selecting neuroimaging techniques: a review for the clinician. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):PCC.12f01490. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12f01490.

1. Silbersweig DA, Rauch SL. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: a quarter century of progress. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25(5):195-197.

2. Insel TR, Wang PS. Rethinking mental illness. JAMA. 2010;303(19):1970-1971.

3. Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Endophenotypes: bridging genomic complexity and disorder heterogeneity. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(11):988-989.

4. Cyranoski D. Neuroscience: thought experiment. Nature. 2011;469:148-149.

5. Amen Clinics. https://www.amenclinics.com/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

6. Pathfinder Brain SPECT Imaging. https://pathfinder.md/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

7. DrSpectScan. http://www.drspectscan.org/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

8. Adinoff B, Devous M. Scientifically unfounded claims in diagnosing and treating patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):598.

9. Borgelt EL, Buchman DZ, Illes J. Neuroimaging in mental health care: voices in translation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:293.

10. Linden DEJ. The challenges and promise of neuroimaging in psychiatry. Neuron. 2012;73(1):8-22.

11. Macqueen GM. Will there be a role for neuroimaging in clinical psychiatry? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35(5):291-293.

12. Boyce AC. Neuroimaging in psychiatry: evaluating the ethical consequences for patient care. Bioethics. 2009;23(6):349-359.

13. Farah MJ, Gillihan SJ. Diagnostic brain imaging in psychiatry: current uses and future prospects. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(6):464-471.

14. Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, et al. Thirteen things physicians and patients should question. Choosing Wisely Canada. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Psychiatry.pdf. Updated June 2017. Accessed October 22, 2019.

15. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al; Work Group on Schizophrenia. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

16. Australian Clinical Guidelines for Early Psychosis. 2nd edition. The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health. https://www.orygen.org.au/Campus/Expert-Network/Resources/Free/Clinical-Practice/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis/Australian-Clinical-Guidelines-for-Early-Psychosis.aspx?ext=. Updated 2016. Accessed October 22, 2019.

17. Freudenreich O, Schulz SC, Goff DC. Initial medical work-up of first-episode psychosis: a conceptual review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(1):10-18.

18. Forbes M, Stefler D, Velakoulis D, et al. The clinical utility of structural neuroimaging in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2019:000486741984803. doi: 10.1177/0004867419848035.

19. Aggarwal N. Neuroimaging, culture, and forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(2):239-244

20. Choi O. What neuroscience can and cannot answer. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45(3):278-285.

21. Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 509 US 579 (1993).

22. Camprodon JA, Stern TA. Selecting neuroimaging techniques: a review for the clinician. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(4):PCC.12f01490. doi: 10.4088/PCC.12f01490.

‘Miracle cures’ in psychiatry?

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

For a patient with a major mental illness, the road to wellness is long and uncertain. The medications commonly used to treat mood and thought disorders can take weeks to months to start providing benefits, and they carry significant risks for adverse effects, such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and movement disorders. Patients often have to take psychotropic medications for the rest of their lives. In addition to these downsides, there is no guarantee that these medications will provide complete or even partial relief.2,3

Recently, there has been growing excitement about new treatments that might be “miracle cures” for patients with mental illness, particularly for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Two of these treatments—ketamine-related compounds, and hallucinogenic drugs—seem to promise therapeutic effects that are vastly different from those of other psychiatric medications: They appear to improve patients’ symptoms very quickly, and their effects may persist long after these drugs have been cleared from the body.

Intravenous ketamine is an older generic drug used in anesthesia; recently, it has been used off-label for TRD and other mental illnesses. On March 5, 2019, the FDA approved an intranasal formulation of esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—for TRD.4 Hallucinogens have also been tested in small studies and have seemingly significant effects in alleviating depression in patients with terminal illnesses5 and reducing smoking behavior in patients with tobacco use disorder.6,7

These miracle cures are becoming increasingly available to patients and continue to gain credibility among clinicians and researchers. How should we evaluate the usefulness of these new treatments? And how should we talk to our patients about them? To answer these questions, this article:

- explores our duty to our patients, ourselves, and our colleagues

- describes the dilemma

- discusses ways to evaluate claims made about these new miracle cures.

Duty: Protecting and helping our patients

The physician–patient relationship is a fiduciary relationship. According to both common law and medical ethics, a physician who enters into a treatment relationship with a patient creates a bond of special trust and confidence. Such a relationship requires a physician to act in good faith and in the patient’s best interests.8 As physicians, we have a duty to evaluate the safety and efficacy of new treatments that are available for our patients, whether or not they are FDA-approved.

We should also protect our patients from the adverse consequences of relatively untested drugs. For example, ketamine and hallucinogens both produce dissociative effects, and may carry high risks for patients who have a predisposition to psychosis.9 We should protect our patients from any false hopes that might lead them to abandon their current treatment regimens due to adverse effects and imperfect results. At the same time, we also have a duty to acknowledge our patients’ suffering and to recognize that they might be desperate for new treatment options. We should remain open-minded about new treatments, and acknowledge that they might work. Finally, we have a duty to be mindful of any financial benefits that we may derive from the development, marketing, and administration of these medications.

Dilemma: The need for new treatments

This is not the first time that novel treatments in mental health have seemed to hold incredible promise. In the late 1800s, Sigmund Freud began to regularly use a compound that led him to feel “the normal euphoria of a healthy person.” He wrote that this substance produced:

…exhilaration and lasting euphoria, which does not differ in any way from the normal euphoria of a healthy person. The feeling of excitement which accompanies stimulus by alcohol is completely lacking; the characteristic urge for immediate activity which alcohol produces is also absent. One senses an increase of self-control and feels more vigorous and more capable of work; on the other hand, if one works, one misses that heightening of the mental powers which alcohol, tea, or coffee induce. One is simply normal, and soon finds it difficult to believe that one is under the influence of any drug at all.1

Continue to: The compound Freud was describing...

The compound Freud was describing is cocaine, which we now know is an addictive and dangerous drug that can in fact worsen depression.10 Another treatment regarded as a miracle cure in its time involved placing patients with schizophrenia into an insulin-induced coma to treat their symptoms; this therapy was used from 1933 to 1960.11 We now recognize that this practice is unacceptably dangerous.

The past is filled with cautionary tales of the enthusiastic adoption of treatments for mental illness that later turned out to be ineffective, counterproductive, dangerous, or inhumane. Yet, the long, arduous journeys our patients go through continue to weigh heavily on us. We would love to offer our patients newer, more efficacious, and longer-lasting treatments with fewer adverse effects.

Discussion: How to best evaluate miracle cures

To help quickly assess a new treatment, the following 5 categories can help guide and organize our thought process.

1. Evidence

What type of evidence do we have that a new treatment is safe and effective? Psychiatric research may be even more susceptible to a placebo effect than other medical research, particularly for illnesses with subjective symptoms, such as depression.12 Double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies, such as the IV ketamine trial conducted by Singh et al,13 are the gold standard for separating a substance’s actual biologic effect from a placebo effect. Studies that do not include a control group should not be regarded as providing scientific evidence of efficacy.

2. Mechanism

If a new compound appears to have a beneficial effect on mental health, it is important to consider the potential mechanism underlying this effect to determine if it is biologically plausible. A compound that is claimed to be a panacea for every symptom of every mental illness should be heavily scrutinized. For example, based on available research, ketamine’s long-lasting effects seem to come from 2 mechanisms14,15:

- Activation of endogenous opioid receptors, which is also responsible for the euphoria induced by heroin and oxycodone.

- Blockade of N-methyl-

D -aspartate receptors. N-methyl-D -aspartate receptor activation is a key mechanism by which learning and memory function in the brain, and blocking these receptors may increase brain plasticity.

Continue to: Therefore, it seems plausible...

Therefore, it seems plausible that ketamine could produce both short- and long-term improvements in mood. Hallucinogenic drugs are thought to profoundly alter brain function through several mechanisms, including activating serotonin receptors, enhancing brain plasticity, and increasing brain connectivity.16

3. Reinforcement

Psychiatric medications that are acutely reinforcing have significant potential for abuse. Antidepressants and mood stabilizers are not acutely rewarding. They don’t make patients feel good right away. Medications such as stimulants and opioids do, and must be used with extreme care because of their abuse potential. The problem with acutely reinforcing medications is that in the long run, they can worsen depression by decreasing the brain’s ability to produce endogenous opioids.17

4.

A mental disorder is unlikely to have a single solution. Rather than regarding a new treatment as capable of rapidly alleviating every symptom of a patient’s illness, it should be viewed as a tool that can be helpful when used in combination with other treatments and lifestyle practices. In an interview with the web site STAT, Cristina Cusin, MD, co-director of the Intravenous Ketamine Clinic for Depression at Massachusetts General Hospital, said, “You don’t treat an advanced disease with just an infusion and a ‘see you next time.’ If [doctors] replace your knee but [you] don’t do physical therapy, you don’t walk again.”18 To sustain the benefits of a novel medication, patients with serious mental illnesses need to maintain strong social supports, see a mental health care provider regularly, and abstain from illicit drug and alcohol use.

5. Context matters

For a medication to obtain approval to treat a specific indication, the FDA usually require 2 trials that demonstrate efficacy. Off-label use of generic medications such as ketamine may have benefits, but it is unlikely that a generic drug would be put through a costly FDA-approval process.19

When learning about new medications, remember that patients might assume that these agents have undergone a thorough review process for safety and effectiveness. When our patients request such treatments—whether FDA-approved or off-label—it is our responsibility as physicians to educate them about the benefits, risks, effectiveness, and limitations of these treatments, as well as to evaluate the appropriateness of a treatment for a specific patient’s symptoms.

Continue to: Tempering excitement with caution

Tempering excitement with caution

Our patients are not the only ones desperate for a miracle cure. As psychiatrists, many of us are desperate, too. New compounds may ultimately change the way we treat mental illness. However, we have an obligation to temper our excitement with caution by remembering past mistakes, and systematically evaluating new miracle cures to determine if they are safe and effective.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

1. Freud S. Cocaine papers. In: Freud S, Byck R. Sigmund Freud collection (Library of Congress). New York, NY: Stonehill; 1975;7.

2. Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):201-204.

3. Demjaha A, Lappin JM, Stahl D, et al. Antipsychotic treatment resistance in first-episode psychosis: prevalence, subtypes and predictors. Psychol Med. 2017;47(11):1981-1989.

4. Carey B. Fast-acting depression drug, newly approved, could help millions. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/05/health/depression-treatment-ketamine-fda.html. Published March 5, 2019. Accessed July 26, 2019.

5. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

6. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:55-60.

7. Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev 2014;7(3):157-164.

8. Simon RI. Clinical psychiatry and the law. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1992.

9. Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, et al. Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25(4):455-467.

10. Perrine SA, Sheikh IS, Nwaneshiudu CA, et al. Withdrawal from chronic administration of cocaine decreases delta opioid receptor signaling and increases anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54(2):355-364.

11. Doroshow DB. Performing a cure for schizophrenia: insulin coma therapy on the wards. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2007;62(2):213-243.

12. Khan A, Kolts RL, Rapaport MH, et al. Magnitude of placebo response and drug-placebo differences across psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(5):743-749.

13. Singh JB, Fedgchin M, Daly EJ, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-frequency study of intravenous ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):816-826.

14. Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, et al. Attenuation of antidepressant effects of ketamine by opioid receptor antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1205-1215.

15. Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22(2):238-249.

16. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

17. Martins SS, Fenton MC, Keyes KM, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders and their association with non-medical prescription opioid use and prescription opioid-use disorder: longitudinal evidence from the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2012;42(6):1261-1272.

18. Thielking M. Ketamine gives hope to patients with severe depression. But some clinics stray from the science and hype its benefits. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2018/09/24/ketamine-clinics-severe-depression-treatment/. Published September 24, 2018. Accessed July 26, 2019.

19. Stafford RS. Regulating off-label drug use--rethinking the role of the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1427-1429.

Mobile apps and mental health: Using technology to quantify real-time clinical risk

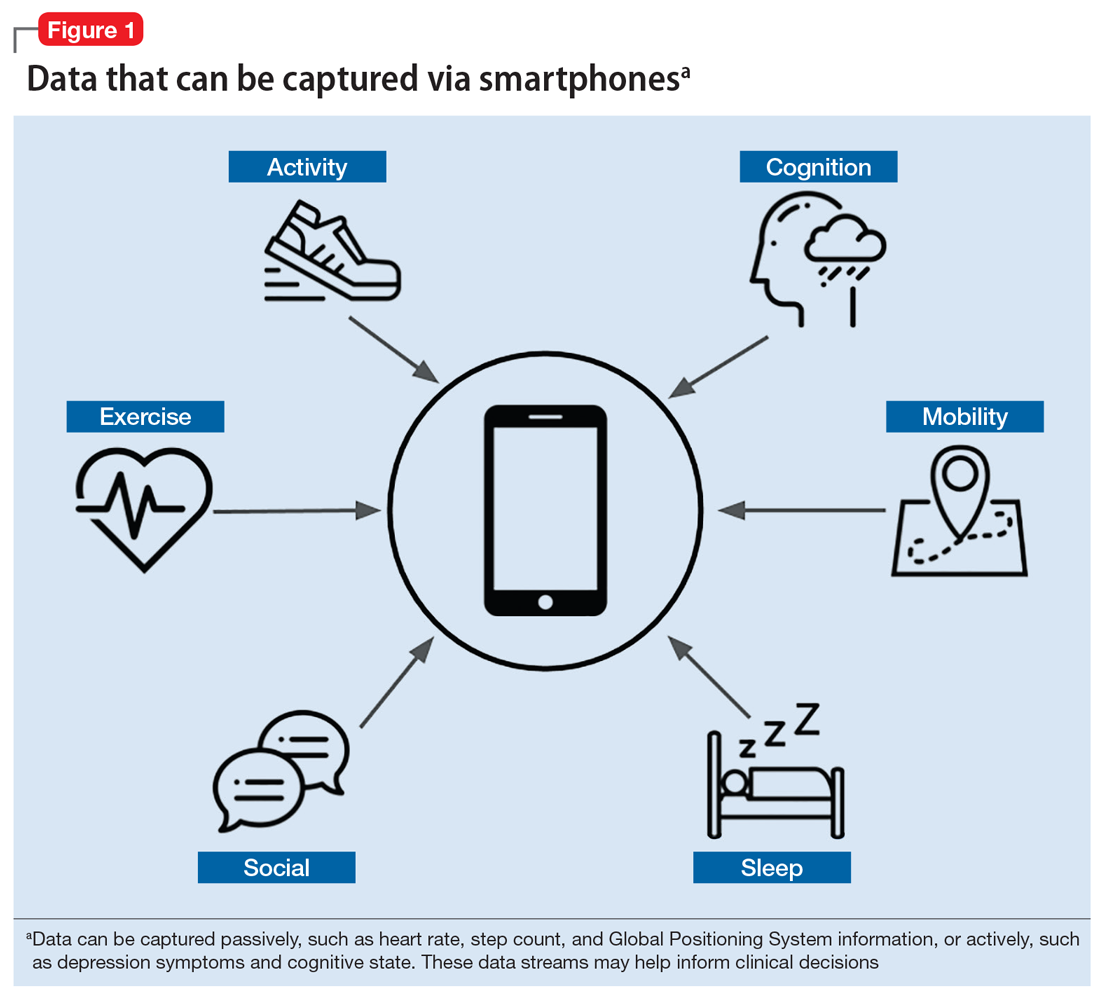

In today’s global society, smartphones are ubiquitous, used by >2.5 billion people.1 They provide limitless availability of on-demand services and resources, unparalleled computing power by size, and the ability to connect with anyone in the world.