User login

Management of the Biconcave (B2) Glenoid in Shoulder Arthroplasty: Technical Considerations

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has demonstrated excellent long-term clinical outcomes for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA).1-5 Glenohumeral OA is characterized by a broad spectrum of glenoid pathology. Both the morphology of the glenoid and humeral head subluxation are important preoperative factors to evaluate, as these have been shown to adversely impact shoulder arthroplasty outcomes.6,7

Walch and colleagues8 have previously classified glenoid morphology in cases of advanced glenohumeral arthritis based on the preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans of individuals undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (Figures 1A-1E). The biconcave (B2) glenoid is characterized by asymmetric posterior bone loss and a posterior translated humeral head that is seated in a biconcave glenoid. The degree and extent of bone loss in the B2 glenoid can be highly variable, ranging from the classic interpretation, in which 50% of the native glenoid fossa is preserved, to the more extreme case with little remaining native anterior glenoid. Scalise and colleagues9 have reported that determining the premorbid native glenoid version with a 3-dimensional (3D) glenoid vault model can aid in differentiating a pathologic B2 glenoid from a nonpathologic type C glenoid.

The B2 glenoid in particular has been associated with poor shoulder arthroplasty outcomes and component survivorship.6,10-12 There are many factors that are thought to contribute to this problem, such as glenoid component malposition, or undercorrection of the pathologic retroversion.6,13,14 Walch and colleagues10 reported that if the neoglenoid retroversion was greater than 27°, there was a 44% incidence of loosening and/or instability and 60% of the dislocations were observed when the humeral head subluxation was greater than 80%. Cases with severe posterior glenoid bone deficiency present a unique challenge to the surgeon, and the ability to accurately and securely place an implant in the correct anatomic position can be compromised. Standard TSA has proven excellent outcomes in the setting of typical glenohumeral OA, but in the B2 glenoid with significant posterior bone erosion, additional attention must be given to ensure adequate correction of the bony deformity, soft tissue balancing, and implant stability.

Several strategies that have been proposed to address extreme bone loss in the B2 glenoid will be discussed in this review. These include hemiarthroplasty, TSA with asymmetric reaming of the high side, TSA with bone grafting of the posterior glenoid bone loss, TSA with an augmented glenoid component, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). Importantly, while these techniques have been proposed for managing the B2 glenoid, currently there is no gold standard consensus for the treatment of this condition. The purpose of this review is to highlight important characteristics of the B2 glenoid morphology on clinical outcomes and discuss the current surgical management options for this condition.

Preoperative Planning

Being able to accurately determine the amount of retroversion is critical for preoperative planning. Friedman and colleagues15 initially described a method to measure glenoid retroversion; however, this is less accurate in B2 glenoids (Figures 2A, 2B). More recently, Rouleau and colleagues16 have validated and published methods to measure glenoid retroversion and subluxation in the B2 glenoid using 3 reference lines: the paleoglenoid (native glenoid surface), intermediate glenoid (line from anterior and posterior edge), and neoglenoid (eroded posterior surface) (Figure 2).

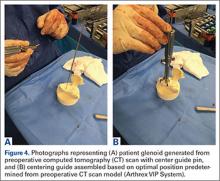

Preoperative evaluation starts with plain radiographs; however, additional imaging is needed, as the axillary view has shown to overestimate retroversion in 86% of patients (Figures 3A-3E).17 For a detailed evaluation of the glenoid retroversion and bone deficiency, CT scans with 3D reconstructions are useful.18,19 The surgical plan should be guided by the location and extent of glenoid bone loss. One tool that has been developed to help in predicting premorbid glenoid version, inclination, and position of the joint line is the 3D virtual glenoid vault model.9,20,21 This helps determine accurate premorbid glenoid anatomy and has been shown to assist in the selection of the optimal implant in an attempt to restore native glenoid anatomy, and avoid peg perforation.21 Patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) for shoulder arthroplasty is being used more frequently and has shown promise for more accurate glenoid component placement, particularly in the complex glenoid with severe bone deficiency. PSI involves creating a custom-fitted guide that is referenced to surface anatomy derived from the preoperative CT scan, which can then direct the surgeon toward optimal implant position with regard to glenoid component location, version and inclination (Figures 4A, 4B). Early reports show that PSI has resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of malpositioned glenoid implants, with the greatest benefit observed in patients with retroversion in excess of 16°.22

Surgical Management

Hemiarthroplasty

Shoulder hemiarthroplasty has been traditionally described as an option for younger, more active patients in whom longevity of the glenoid component is a concern, or in patients with inadequate glenoid bone stock to tolerate a glenoid component. While there are no reports of hemiarthroplasty specifically for patients with B2 glenoids, one study has examined the effect of glenoid morphology on the outcomes of hemiarthroplasty for shoulder osteoarthritis. Levine and colleagues7 reported inferior clinical outcomes after shoulder hemiarthroplasty in patients with eccentric posterior glenoid wear. Several authors have advocated a “ream-and-run” technique to create a concentric glenoid and re-center the humeral head while still maintaining the native glenoid.23,24 However, in a recent series of 162 ream-and-run procedures, Gilmer and colleagues25 reported that only 23% of patients with B2 glenoid geometry achieved a minimal clinically important change in patient-reported outcome scores and 14% required revision. Furthermore, Lynch and colleagues26 found that progressive medial erosion and recurrent posterior glenoid erosion occur in a significant percentage of patients at early follow-up. Given these recent findings, the use of hemiarthroplasty alone or a ream-and-run procedure for patients with B2 glenoid morphology should be approached with caution.

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

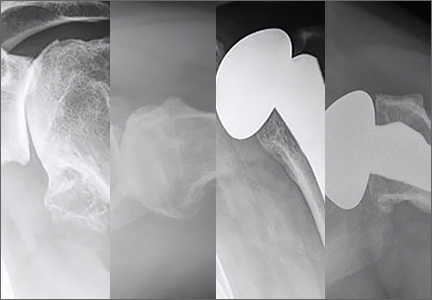

As with any TSA, the primary goals in treating patients with B2 glenoid defects are to provide the patient with a pain-free, stable, and functional shoulder (Figures 5A-5D). There are, however, a few challenges that are unique to TSA in the setting of B2 glenoid defects. Because the humeral head is often subluxated posteriorly into the defect, the anterior capsule and rotator cuff can tighten while the posterior aspect of the joint becomes lax. These soft tissues must be balanced during TSA in order to stabilize the shoulder and restore the appropriate length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff. The other primary concern is restoration of appropriate glenoid version and lateralization. To accomplish this, the most common techniques utilized are asymmetric reaming, bone graft augmentation, and glenoid component augmentation.27,28

Asymmetric Reaming. One of the more readily utilized techniques for addressing the B2 glenoid during TSA is eccentric or asymmetric reaming. During this process, the anterior glenoid is preferentially reamed while little to no bone is removed posteriorly. This technique is generally felt to be sufficient to treat posterior defects up to 5 mm to 8 mm or retroversion up to 15°.28 These upper limits have been confirmed in a number of cadaveric and simulated models.29-31

The success of this technique hinges on excellent glenoid exposure. With appropriate retractors in place, the anterior capsulolabral complex, including the biceps insertion, is resected to improve visualization. The inferior capsule must be resected carefully to ensure exposure and better motion postoperatively. On the other hand, it is imperative to protect the posterior capsulolabral attachments because of the increased risk of posterior instability in patients with B2 glenoids.

Detailed imaging such as CT scans with 3D reconstructions have improved our understanding of the degree of the deformities in all directions, which can better guide the reaming. PSI and planning software developed to improve the surgeon’s ability to place the glenoid component centrally in the best possible position after version correction can be even more helpful. We find that using a burr to provisionally lower the high side (anterior) provides a more en face view, which subsequently makes the eccentric reaming easier. As a guide, we will not ream more than 1 cm of anterior bone or attempt to correct more than ~20° of retroversion. The goal should be to create a glenoid surface that is more neutral and congruent to the posterior surface of the glenoid component while not overmedializing the component.

Although eccentric reaming may be one of the more straightforward methods for addressing posterior glenoid erosion, it is not without a number of potential downsides. When attempting to correct defects >10 mm or retroversion beyond 15°, excessive medialization of the implant can occur. Although increasing the thickness of the glenoid component can compensate for small amounts of medialization, excessive medialization can lead to a number of issues.27,28,32 As reaming progresses medially, the risk of keel penetration increases as the glenoid vault narrows.30,32 Further medialization decreases posterior cortical support for the implant, which increases the risk of component loosening and subsidence.33-35 The more medial the implant is placed, the smaller the surface of available bone for implant fixation. This often requires utilization of a smaller sized glenoid component that may result in component mismatch with the humeral implant. Finally, excessive medialization has the potential to under tension the rotator cuff, leading to decreased shoulder stability, strength, and function.

Bone Graft Augmentation. When posterior erosion becomes too excessive to address with eccentric reaming alone, defect augmentation is another option to consider (Figures 6A-6E). While technically more demanding, bone graft also provides the advantage of better re-creating the natural joint line and center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint.

For most defects, the resected humeral head provides the ideal source of graft. After initial reaming of the anterior glenoid, the defect must be sized and measured. We then recommend using a guided, cannulated system to place a central pin, lying perpendicular to the glenoid axis in neutral position. The anterior glenoid is then reamed enough to create a flat surface on which to attach the bone graft. The posterior surface is then gently burred to create a bleeding surface to enhance graft incorporation. The graft is then contoured to the defect and placed flush with the anterior glenoid. Cannulated screws are placed over guidewires to fix the graft. Using an arthroscopic cannula inserted posteriorly allows for easier placement of the guidewires and easier implantation of the screws. Although a reamer or burr can be used to contour the graft once it is fixed in place, this should be minimized to prevent loss of fixation. When the graft is fixed, we then cement the glenoid component into place.

Although good clinical results have been obtained with this technique, there is concern of incomplete graft healing and component loosening in the long term. Even in clinically asymptomatic and well functioning patients, some degree of radiographic lucency may be present in over 50% of cases.31,36,37 Glenoid Component Augmentation. To address the issues related to lucency and nonunion of bone graft augmentation, several augmented glenoid components have been developed. Augmented glenoid components have the benefit of filling posterior defects and stabilizing the shoulder without requiring excessive medialization (as often occurs with eccentric reaming) or union of a bone-to-bone interface (as is required in bone graft augmentation).38 Although many of the metal back designs experienced undesirably high failure rates and have since been recalled,39 more modern all-polyethylene components hold promise. The 2 most commonly utilized designs are the posterior step augment (DePuy) and the posterior wedge (Exactech). Although biomechanical analyses of both designs have demonstrated increased stability during loading in cadaveric and simulation models, the step augment (DePuy) has demonstrated increased stability and resistance to loosening.40,41 Although midterm results are not yet available for this newest generation of augmented components, short-term results with 2 to 3 years of follow-up have demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes.28

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

While most commonly indicated for patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, RSA has recently been advocated for older patients with osteoarthritis and B2 glenoids in the setting of an intact rotator cuff. The semi-constrained design of the RSA is a potential solution to the static posterior humeral head subluxation seen in patients with B2 glenoid geometry (Figure 6E).

Technically, RSA is often an easier solution than a TSA with bone grafting because there is usually enough glenoid bone stock for fixation. That said, we always get a CT scan with 3D reconstructions to better appreciate the anatomy. Note that in B2 glenoids, the bone loss is typically posterior and inferior. RSA in the setting of a B2 glenoid is one of the ideal indications to use PSI to ensure ideal placement of the central pin, which is the key to glenoid baseplate positioning. Even when using a RSA, eccentric reaming and/or bone grafting allow for more ideal component placement. Using the same eccentric reaming techniques described above, one should try to ream to place the baseplate at 10° of retroversion. In cases where retroversion cannot be corrected to 10°, graft can be taken from the humeral head, iliac crest, or allograft. A benefit to using bone graft with RSA as opposed to TSA is that the graft can be fashioned to the baseplate, impacted/compressed into the B2 glenoid, and then secured with a central compression screw and peripheral locking screws.

Mizuno and colleagues41 reported a retrospective series of 27 RSAs performed for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis and biconcave glenoid. At a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years, the authors noted significant improvement in Constant scores and shoulder motion with minimal complications. There was no recurrence of posterior instability observed by the time of final follow-up.41

RSA is a promising treatment for primary glenohumeral arthritis with posterior glenoid bone loss and static posterior subluxation in elderly or less active patients, but the longevity of these implants has yet to be established for younger, more active patients and requires further study.

Conclusion

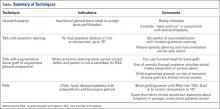

Reconstruction of the B2 glenoid presents a challenging clinical problem that has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. The high failure rate from glenoid component loosening and subsequent premature implant failure can be substantially decreased with accurate glenoid component positioning and appropriate correction of the pathologic glenoid retroversion. Careful preoperative planning is essential for accurate preparation and execution of the optimal surgical plan. There are many surgical strategies to address the B2 glenoid, but no consensus on the optimal method exists, as the technique should be uniquely customized to the individual’s pathology and surgeon preference (Table). Cases with mild deformity may be corrected with eccentric reaming and TSA, while the more severe deformities may require posterior glenoid bone grafting and/or augmented implants to restore native version. Finally, the RSA is a reliable option to restore stability and address bone deficiency for the severe B2 glenoid in an older, lower demand patient.

1. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

2. Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman GM, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1947-1956.

3. Matsen FA 3rd. Early effectiveness of shoulder arthroplasty for patients who have primary glenohumeral degenerative joint disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(2):260-264.

4. Fenlin JM Jr, Frieman BG. Indications, technique, and results of total shoulder arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1998;29(3):423-434.

5. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: Analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517.

6. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

7. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

8. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

9. Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J, Iannotti JP. The three-dimensional glenoid vault model can estimate normal glenoid version in osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(3):487-491.

10. Walch G, Moraga C, Young A, Castellanos-Rosas J. Results of anatomic nonconstrained prosthesis in primary osteoarthritis with biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1526-1533.

11. Kany J, Katz D. How to deal with glenoid type B2 or C? How to prevent mistakes in implantation of glenoid component? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23(4):379-385.

12. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598.

13. Iannotti JP, Greeson C, Downing D, Sabesan V, Bryan JA. Effect of glenoid deformity on glenoid component placement in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):48-55.

14. Ho JC, Sabesan VJ, Iannotti JP. Glenoid component retroversion is associated with osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e82.

15. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

16. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Defranco M, Walch G. Glenoid version: How to measure it? Validity of different methods in two-dimensional computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1230-1237.

17. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: Conventional radiographs versus computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

18. Budge MD, Lewis GS, Schaefer E, Coquia S, Flemming DJ, Armstrong AD. Comparison of standard two-dimensional and three-dimensional corrected glenoid version measurements. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):577-583.

19. Bokor DJ, O’Sullivan MD, Hazan GJ. Variability of measurement of glenoid version on computed tomography scan. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(6):595-598.

20. Ganapathi A, McCarron JA, Chen X, Iannotti JP. Predicting normal glenoid version from the pathologic scapula: A comparison of 4 methods in 2- and 3-dimensional models. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):234-244.

21. Ricchetti ET, Hendel MD, Collins DN, Iannotti JP. Is premorbid glenoid anatomy altered in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):2932-2939.

22. Hendel MD, Bryan JA, Barsoum WK, et al. Comparison of patient-specific instruments with standard surgical instruments in determining glenoid component position: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2167-2175.

23. Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ, Jackins SE. Can the ream and run procedure improve glenohumeral relationships and function for shoulders with the arthritic triad? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2088-2096.

24. Saltzman MD, Chamberlain AM, Mercer DM, Warme WJ, Bertelsen AL, Matsen FA 3rd. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming in patients 55 years old or less. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):609-615.

25. Gilmer BB, Comstock BA, Jette JL, Warme WJ, Jackins SE, Matsen FA. The prognosis for improvement in comfort and function after the ream-and-run arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis: An analysis of 176 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):e102.

26. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH Jr, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA 3rd. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292.

27. Donohue KW, Ricchetti ET, Iannotti JP. Surgical management of the biconcave (B2) glenoid. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(1):30-39.

28. Clavert P, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Glenoid resurfacing: What are the limits to asymmetric reaming for posterior erosion? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):843-848.

29. Gillespie R, Lyons R, Lazarus M. Eccentric reaming in total shoulder arthroplasty: A cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2009;32(1):21.

30. Neer CS 2nd, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

31. Nowak DD, Bahu MJ, Gardner TR, et al. Simulation of surgical glenoid resurfacing using three-dimensional computed tomography of the arthritic glenohumeral joint: The amount of glenoid retroversion that can be corrected. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):680-688.

32. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833.

33. Walch G, Young AA, Boileau P, Loew M, Gazielly D, Mole D. Patterns of loosening of polyethylene keeled glenoid components after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: Results of a multicenter study with more than five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):145-150.

34. Walch G, Young AA, Melis B, Gazielly D, Loew M, Boileau P. Results of a convex-back cemented keeled glenoid component in primary osteoarthritis: Multicenter study with a follow-up greater than 5 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):385-394.

35. Klika BJ, Wooten CW, Sperling JW, et al. Structural bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1066-1072.

36. Sabesan V, Callanan M, Sharma V, Iannotti JP. Correction of acquired glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis with a standard versus an augmented glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):964-973.

37. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

38. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157.

39. Iannotti JP, Lappin KE, Klotz CL, Reber EW, Swope SW. Liftoff resistance of augmented glenoid components during cyclic fatigue loading in the posterior-superior direction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1530-1536.

40. Knowles NK, Ferreira LM, Athwal GS. Augmented glenoid component designs for type B2 erosions: A computational comparison by volume of bone removal and quality of remaining bone. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):1218-1226.

41. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has demonstrated excellent long-term clinical outcomes for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA).1-5 Glenohumeral OA is characterized by a broad spectrum of glenoid pathology. Both the morphology of the glenoid and humeral head subluxation are important preoperative factors to evaluate, as these have been shown to adversely impact shoulder arthroplasty outcomes.6,7

Walch and colleagues8 have previously classified glenoid morphology in cases of advanced glenohumeral arthritis based on the preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans of individuals undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (Figures 1A-1E). The biconcave (B2) glenoid is characterized by asymmetric posterior bone loss and a posterior translated humeral head that is seated in a biconcave glenoid. The degree and extent of bone loss in the B2 glenoid can be highly variable, ranging from the classic interpretation, in which 50% of the native glenoid fossa is preserved, to the more extreme case with little remaining native anterior glenoid. Scalise and colleagues9 have reported that determining the premorbid native glenoid version with a 3-dimensional (3D) glenoid vault model can aid in differentiating a pathologic B2 glenoid from a nonpathologic type C glenoid.

The B2 glenoid in particular has been associated with poor shoulder arthroplasty outcomes and component survivorship.6,10-12 There are many factors that are thought to contribute to this problem, such as glenoid component malposition, or undercorrection of the pathologic retroversion.6,13,14 Walch and colleagues10 reported that if the neoglenoid retroversion was greater than 27°, there was a 44% incidence of loosening and/or instability and 60% of the dislocations were observed when the humeral head subluxation was greater than 80%. Cases with severe posterior glenoid bone deficiency present a unique challenge to the surgeon, and the ability to accurately and securely place an implant in the correct anatomic position can be compromised. Standard TSA has proven excellent outcomes in the setting of typical glenohumeral OA, but in the B2 glenoid with significant posterior bone erosion, additional attention must be given to ensure adequate correction of the bony deformity, soft tissue balancing, and implant stability.

Several strategies that have been proposed to address extreme bone loss in the B2 glenoid will be discussed in this review. These include hemiarthroplasty, TSA with asymmetric reaming of the high side, TSA with bone grafting of the posterior glenoid bone loss, TSA with an augmented glenoid component, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). Importantly, while these techniques have been proposed for managing the B2 glenoid, currently there is no gold standard consensus for the treatment of this condition. The purpose of this review is to highlight important characteristics of the B2 glenoid morphology on clinical outcomes and discuss the current surgical management options for this condition.

Preoperative Planning

Being able to accurately determine the amount of retroversion is critical for preoperative planning. Friedman and colleagues15 initially described a method to measure glenoid retroversion; however, this is less accurate in B2 glenoids (Figures 2A, 2B). More recently, Rouleau and colleagues16 have validated and published methods to measure glenoid retroversion and subluxation in the B2 glenoid using 3 reference lines: the paleoglenoid (native glenoid surface), intermediate glenoid (line from anterior and posterior edge), and neoglenoid (eroded posterior surface) (Figure 2).

Preoperative evaluation starts with plain radiographs; however, additional imaging is needed, as the axillary view has shown to overestimate retroversion in 86% of patients (Figures 3A-3E).17 For a detailed evaluation of the glenoid retroversion and bone deficiency, CT scans with 3D reconstructions are useful.18,19 The surgical plan should be guided by the location and extent of glenoid bone loss. One tool that has been developed to help in predicting premorbid glenoid version, inclination, and position of the joint line is the 3D virtual glenoid vault model.9,20,21 This helps determine accurate premorbid glenoid anatomy and has been shown to assist in the selection of the optimal implant in an attempt to restore native glenoid anatomy, and avoid peg perforation.21 Patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) for shoulder arthroplasty is being used more frequently and has shown promise for more accurate glenoid component placement, particularly in the complex glenoid with severe bone deficiency. PSI involves creating a custom-fitted guide that is referenced to surface anatomy derived from the preoperative CT scan, which can then direct the surgeon toward optimal implant position with regard to glenoid component location, version and inclination (Figures 4A, 4B). Early reports show that PSI has resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of malpositioned glenoid implants, with the greatest benefit observed in patients with retroversion in excess of 16°.22

Surgical Management

Hemiarthroplasty

Shoulder hemiarthroplasty has been traditionally described as an option for younger, more active patients in whom longevity of the glenoid component is a concern, or in patients with inadequate glenoid bone stock to tolerate a glenoid component. While there are no reports of hemiarthroplasty specifically for patients with B2 glenoids, one study has examined the effect of glenoid morphology on the outcomes of hemiarthroplasty for shoulder osteoarthritis. Levine and colleagues7 reported inferior clinical outcomes after shoulder hemiarthroplasty in patients with eccentric posterior glenoid wear. Several authors have advocated a “ream-and-run” technique to create a concentric glenoid and re-center the humeral head while still maintaining the native glenoid.23,24 However, in a recent series of 162 ream-and-run procedures, Gilmer and colleagues25 reported that only 23% of patients with B2 glenoid geometry achieved a minimal clinically important change in patient-reported outcome scores and 14% required revision. Furthermore, Lynch and colleagues26 found that progressive medial erosion and recurrent posterior glenoid erosion occur in a significant percentage of patients at early follow-up. Given these recent findings, the use of hemiarthroplasty alone or a ream-and-run procedure for patients with B2 glenoid morphology should be approached with caution.

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

As with any TSA, the primary goals in treating patients with B2 glenoid defects are to provide the patient with a pain-free, stable, and functional shoulder (Figures 5A-5D). There are, however, a few challenges that are unique to TSA in the setting of B2 glenoid defects. Because the humeral head is often subluxated posteriorly into the defect, the anterior capsule and rotator cuff can tighten while the posterior aspect of the joint becomes lax. These soft tissues must be balanced during TSA in order to stabilize the shoulder and restore the appropriate length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff. The other primary concern is restoration of appropriate glenoid version and lateralization. To accomplish this, the most common techniques utilized are asymmetric reaming, bone graft augmentation, and glenoid component augmentation.27,28

Asymmetric Reaming. One of the more readily utilized techniques for addressing the B2 glenoid during TSA is eccentric or asymmetric reaming. During this process, the anterior glenoid is preferentially reamed while little to no bone is removed posteriorly. This technique is generally felt to be sufficient to treat posterior defects up to 5 mm to 8 mm or retroversion up to 15°.28 These upper limits have been confirmed in a number of cadaveric and simulated models.29-31

The success of this technique hinges on excellent glenoid exposure. With appropriate retractors in place, the anterior capsulolabral complex, including the biceps insertion, is resected to improve visualization. The inferior capsule must be resected carefully to ensure exposure and better motion postoperatively. On the other hand, it is imperative to protect the posterior capsulolabral attachments because of the increased risk of posterior instability in patients with B2 glenoids.

Detailed imaging such as CT scans with 3D reconstructions have improved our understanding of the degree of the deformities in all directions, which can better guide the reaming. PSI and planning software developed to improve the surgeon’s ability to place the glenoid component centrally in the best possible position after version correction can be even more helpful. We find that using a burr to provisionally lower the high side (anterior) provides a more en face view, which subsequently makes the eccentric reaming easier. As a guide, we will not ream more than 1 cm of anterior bone or attempt to correct more than ~20° of retroversion. The goal should be to create a glenoid surface that is more neutral and congruent to the posterior surface of the glenoid component while not overmedializing the component.

Although eccentric reaming may be one of the more straightforward methods for addressing posterior glenoid erosion, it is not without a number of potential downsides. When attempting to correct defects >10 mm or retroversion beyond 15°, excessive medialization of the implant can occur. Although increasing the thickness of the glenoid component can compensate for small amounts of medialization, excessive medialization can lead to a number of issues.27,28,32 As reaming progresses medially, the risk of keel penetration increases as the glenoid vault narrows.30,32 Further medialization decreases posterior cortical support for the implant, which increases the risk of component loosening and subsidence.33-35 The more medial the implant is placed, the smaller the surface of available bone for implant fixation. This often requires utilization of a smaller sized glenoid component that may result in component mismatch with the humeral implant. Finally, excessive medialization has the potential to under tension the rotator cuff, leading to decreased shoulder stability, strength, and function.

Bone Graft Augmentation. When posterior erosion becomes too excessive to address with eccentric reaming alone, defect augmentation is another option to consider (Figures 6A-6E). While technically more demanding, bone graft also provides the advantage of better re-creating the natural joint line and center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint.

For most defects, the resected humeral head provides the ideal source of graft. After initial reaming of the anterior glenoid, the defect must be sized and measured. We then recommend using a guided, cannulated system to place a central pin, lying perpendicular to the glenoid axis in neutral position. The anterior glenoid is then reamed enough to create a flat surface on which to attach the bone graft. The posterior surface is then gently burred to create a bleeding surface to enhance graft incorporation. The graft is then contoured to the defect and placed flush with the anterior glenoid. Cannulated screws are placed over guidewires to fix the graft. Using an arthroscopic cannula inserted posteriorly allows for easier placement of the guidewires and easier implantation of the screws. Although a reamer or burr can be used to contour the graft once it is fixed in place, this should be minimized to prevent loss of fixation. When the graft is fixed, we then cement the glenoid component into place.

Although good clinical results have been obtained with this technique, there is concern of incomplete graft healing and component loosening in the long term. Even in clinically asymptomatic and well functioning patients, some degree of radiographic lucency may be present in over 50% of cases.31,36,37 Glenoid Component Augmentation. To address the issues related to lucency and nonunion of bone graft augmentation, several augmented glenoid components have been developed. Augmented glenoid components have the benefit of filling posterior defects and stabilizing the shoulder without requiring excessive medialization (as often occurs with eccentric reaming) or union of a bone-to-bone interface (as is required in bone graft augmentation).38 Although many of the metal back designs experienced undesirably high failure rates and have since been recalled,39 more modern all-polyethylene components hold promise. The 2 most commonly utilized designs are the posterior step augment (DePuy) and the posterior wedge (Exactech). Although biomechanical analyses of both designs have demonstrated increased stability during loading in cadaveric and simulation models, the step augment (DePuy) has demonstrated increased stability and resistance to loosening.40,41 Although midterm results are not yet available for this newest generation of augmented components, short-term results with 2 to 3 years of follow-up have demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes.28

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

While most commonly indicated for patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, RSA has recently been advocated for older patients with osteoarthritis and B2 glenoids in the setting of an intact rotator cuff. The semi-constrained design of the RSA is a potential solution to the static posterior humeral head subluxation seen in patients with B2 glenoid geometry (Figure 6E).

Technically, RSA is often an easier solution than a TSA with bone grafting because there is usually enough glenoid bone stock for fixation. That said, we always get a CT scan with 3D reconstructions to better appreciate the anatomy. Note that in B2 glenoids, the bone loss is typically posterior and inferior. RSA in the setting of a B2 glenoid is one of the ideal indications to use PSI to ensure ideal placement of the central pin, which is the key to glenoid baseplate positioning. Even when using a RSA, eccentric reaming and/or bone grafting allow for more ideal component placement. Using the same eccentric reaming techniques described above, one should try to ream to place the baseplate at 10° of retroversion. In cases where retroversion cannot be corrected to 10°, graft can be taken from the humeral head, iliac crest, or allograft. A benefit to using bone graft with RSA as opposed to TSA is that the graft can be fashioned to the baseplate, impacted/compressed into the B2 glenoid, and then secured with a central compression screw and peripheral locking screws.

Mizuno and colleagues41 reported a retrospective series of 27 RSAs performed for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis and biconcave glenoid. At a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years, the authors noted significant improvement in Constant scores and shoulder motion with minimal complications. There was no recurrence of posterior instability observed by the time of final follow-up.41

RSA is a promising treatment for primary glenohumeral arthritis with posterior glenoid bone loss and static posterior subluxation in elderly or less active patients, but the longevity of these implants has yet to be established for younger, more active patients and requires further study.

Conclusion

Reconstruction of the B2 glenoid presents a challenging clinical problem that has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. The high failure rate from glenoid component loosening and subsequent premature implant failure can be substantially decreased with accurate glenoid component positioning and appropriate correction of the pathologic glenoid retroversion. Careful preoperative planning is essential for accurate preparation and execution of the optimal surgical plan. There are many surgical strategies to address the B2 glenoid, but no consensus on the optimal method exists, as the technique should be uniquely customized to the individual’s pathology and surgeon preference (Table). Cases with mild deformity may be corrected with eccentric reaming and TSA, while the more severe deformities may require posterior glenoid bone grafting and/or augmented implants to restore native version. Finally, the RSA is a reliable option to restore stability and address bone deficiency for the severe B2 glenoid in an older, lower demand patient.

Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) has demonstrated excellent long-term clinical outcomes for the treatment of advanced glenohumeral osteoarthritis (OA).1-5 Glenohumeral OA is characterized by a broad spectrum of glenoid pathology. Both the morphology of the glenoid and humeral head subluxation are important preoperative factors to evaluate, as these have been shown to adversely impact shoulder arthroplasty outcomes.6,7

Walch and colleagues8 have previously classified glenoid morphology in cases of advanced glenohumeral arthritis based on the preoperative computed tomography (CT) scans of individuals undergoing shoulder arthroplasty (Figures 1A-1E). The biconcave (B2) glenoid is characterized by asymmetric posterior bone loss and a posterior translated humeral head that is seated in a biconcave glenoid. The degree and extent of bone loss in the B2 glenoid can be highly variable, ranging from the classic interpretation, in which 50% of the native glenoid fossa is preserved, to the more extreme case with little remaining native anterior glenoid. Scalise and colleagues9 have reported that determining the premorbid native glenoid version with a 3-dimensional (3D) glenoid vault model can aid in differentiating a pathologic B2 glenoid from a nonpathologic type C glenoid.

The B2 glenoid in particular has been associated with poor shoulder arthroplasty outcomes and component survivorship.6,10-12 There are many factors that are thought to contribute to this problem, such as glenoid component malposition, or undercorrection of the pathologic retroversion.6,13,14 Walch and colleagues10 reported that if the neoglenoid retroversion was greater than 27°, there was a 44% incidence of loosening and/or instability and 60% of the dislocations were observed when the humeral head subluxation was greater than 80%. Cases with severe posterior glenoid bone deficiency present a unique challenge to the surgeon, and the ability to accurately and securely place an implant in the correct anatomic position can be compromised. Standard TSA has proven excellent outcomes in the setting of typical glenohumeral OA, but in the B2 glenoid with significant posterior bone erosion, additional attention must be given to ensure adequate correction of the bony deformity, soft tissue balancing, and implant stability.

Several strategies that have been proposed to address extreme bone loss in the B2 glenoid will be discussed in this review. These include hemiarthroplasty, TSA with asymmetric reaming of the high side, TSA with bone grafting of the posterior glenoid bone loss, TSA with an augmented glenoid component, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). Importantly, while these techniques have been proposed for managing the B2 glenoid, currently there is no gold standard consensus for the treatment of this condition. The purpose of this review is to highlight important characteristics of the B2 glenoid morphology on clinical outcomes and discuss the current surgical management options for this condition.

Preoperative Planning

Being able to accurately determine the amount of retroversion is critical for preoperative planning. Friedman and colleagues15 initially described a method to measure glenoid retroversion; however, this is less accurate in B2 glenoids (Figures 2A, 2B). More recently, Rouleau and colleagues16 have validated and published methods to measure glenoid retroversion and subluxation in the B2 glenoid using 3 reference lines: the paleoglenoid (native glenoid surface), intermediate glenoid (line from anterior and posterior edge), and neoglenoid (eroded posterior surface) (Figure 2).

Preoperative evaluation starts with plain radiographs; however, additional imaging is needed, as the axillary view has shown to overestimate retroversion in 86% of patients (Figures 3A-3E).17 For a detailed evaluation of the glenoid retroversion and bone deficiency, CT scans with 3D reconstructions are useful.18,19 The surgical plan should be guided by the location and extent of glenoid bone loss. One tool that has been developed to help in predicting premorbid glenoid version, inclination, and position of the joint line is the 3D virtual glenoid vault model.9,20,21 This helps determine accurate premorbid glenoid anatomy and has been shown to assist in the selection of the optimal implant in an attempt to restore native glenoid anatomy, and avoid peg perforation.21 Patient-specific instrumentation (PSI) for shoulder arthroplasty is being used more frequently and has shown promise for more accurate glenoid component placement, particularly in the complex glenoid with severe bone deficiency. PSI involves creating a custom-fitted guide that is referenced to surface anatomy derived from the preoperative CT scan, which can then direct the surgeon toward optimal implant position with regard to glenoid component location, version and inclination (Figures 4A, 4B). Early reports show that PSI has resulted in a significant reduction in the frequency of malpositioned glenoid implants, with the greatest benefit observed in patients with retroversion in excess of 16°.22

Surgical Management

Hemiarthroplasty

Shoulder hemiarthroplasty has been traditionally described as an option for younger, more active patients in whom longevity of the glenoid component is a concern, or in patients with inadequate glenoid bone stock to tolerate a glenoid component. While there are no reports of hemiarthroplasty specifically for patients with B2 glenoids, one study has examined the effect of glenoid morphology on the outcomes of hemiarthroplasty for shoulder osteoarthritis. Levine and colleagues7 reported inferior clinical outcomes after shoulder hemiarthroplasty in patients with eccentric posterior glenoid wear. Several authors have advocated a “ream-and-run” technique to create a concentric glenoid and re-center the humeral head while still maintaining the native glenoid.23,24 However, in a recent series of 162 ream-and-run procedures, Gilmer and colleagues25 reported that only 23% of patients with B2 glenoid geometry achieved a minimal clinically important change in patient-reported outcome scores and 14% required revision. Furthermore, Lynch and colleagues26 found that progressive medial erosion and recurrent posterior glenoid erosion occur in a significant percentage of patients at early follow-up. Given these recent findings, the use of hemiarthroplasty alone or a ream-and-run procedure for patients with B2 glenoid morphology should be approached with caution.

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

As with any TSA, the primary goals in treating patients with B2 glenoid defects are to provide the patient with a pain-free, stable, and functional shoulder (Figures 5A-5D). There are, however, a few challenges that are unique to TSA in the setting of B2 glenoid defects. Because the humeral head is often subluxated posteriorly into the defect, the anterior capsule and rotator cuff can tighten while the posterior aspect of the joint becomes lax. These soft tissues must be balanced during TSA in order to stabilize the shoulder and restore the appropriate length-tension relationship of the rotator cuff. The other primary concern is restoration of appropriate glenoid version and lateralization. To accomplish this, the most common techniques utilized are asymmetric reaming, bone graft augmentation, and glenoid component augmentation.27,28

Asymmetric Reaming. One of the more readily utilized techniques for addressing the B2 glenoid during TSA is eccentric or asymmetric reaming. During this process, the anterior glenoid is preferentially reamed while little to no bone is removed posteriorly. This technique is generally felt to be sufficient to treat posterior defects up to 5 mm to 8 mm or retroversion up to 15°.28 These upper limits have been confirmed in a number of cadaveric and simulated models.29-31

The success of this technique hinges on excellent glenoid exposure. With appropriate retractors in place, the anterior capsulolabral complex, including the biceps insertion, is resected to improve visualization. The inferior capsule must be resected carefully to ensure exposure and better motion postoperatively. On the other hand, it is imperative to protect the posterior capsulolabral attachments because of the increased risk of posterior instability in patients with B2 glenoids.

Detailed imaging such as CT scans with 3D reconstructions have improved our understanding of the degree of the deformities in all directions, which can better guide the reaming. PSI and planning software developed to improve the surgeon’s ability to place the glenoid component centrally in the best possible position after version correction can be even more helpful. We find that using a burr to provisionally lower the high side (anterior) provides a more en face view, which subsequently makes the eccentric reaming easier. As a guide, we will not ream more than 1 cm of anterior bone or attempt to correct more than ~20° of retroversion. The goal should be to create a glenoid surface that is more neutral and congruent to the posterior surface of the glenoid component while not overmedializing the component.

Although eccentric reaming may be one of the more straightforward methods for addressing posterior glenoid erosion, it is not without a number of potential downsides. When attempting to correct defects >10 mm or retroversion beyond 15°, excessive medialization of the implant can occur. Although increasing the thickness of the glenoid component can compensate for small amounts of medialization, excessive medialization can lead to a number of issues.27,28,32 As reaming progresses medially, the risk of keel penetration increases as the glenoid vault narrows.30,32 Further medialization decreases posterior cortical support for the implant, which increases the risk of component loosening and subsidence.33-35 The more medial the implant is placed, the smaller the surface of available bone for implant fixation. This often requires utilization of a smaller sized glenoid component that may result in component mismatch with the humeral implant. Finally, excessive medialization has the potential to under tension the rotator cuff, leading to decreased shoulder stability, strength, and function.

Bone Graft Augmentation. When posterior erosion becomes too excessive to address with eccentric reaming alone, defect augmentation is another option to consider (Figures 6A-6E). While technically more demanding, bone graft also provides the advantage of better re-creating the natural joint line and center of rotation of the glenohumeral joint.

For most defects, the resected humeral head provides the ideal source of graft. After initial reaming of the anterior glenoid, the defect must be sized and measured. We then recommend using a guided, cannulated system to place a central pin, lying perpendicular to the glenoid axis in neutral position. The anterior glenoid is then reamed enough to create a flat surface on which to attach the bone graft. The posterior surface is then gently burred to create a bleeding surface to enhance graft incorporation. The graft is then contoured to the defect and placed flush with the anterior glenoid. Cannulated screws are placed over guidewires to fix the graft. Using an arthroscopic cannula inserted posteriorly allows for easier placement of the guidewires and easier implantation of the screws. Although a reamer or burr can be used to contour the graft once it is fixed in place, this should be minimized to prevent loss of fixation. When the graft is fixed, we then cement the glenoid component into place.

Although good clinical results have been obtained with this technique, there is concern of incomplete graft healing and component loosening in the long term. Even in clinically asymptomatic and well functioning patients, some degree of radiographic lucency may be present in over 50% of cases.31,36,37 Glenoid Component Augmentation. To address the issues related to lucency and nonunion of bone graft augmentation, several augmented glenoid components have been developed. Augmented glenoid components have the benefit of filling posterior defects and stabilizing the shoulder without requiring excessive medialization (as often occurs with eccentric reaming) or union of a bone-to-bone interface (as is required in bone graft augmentation).38 Although many of the metal back designs experienced undesirably high failure rates and have since been recalled,39 more modern all-polyethylene components hold promise. The 2 most commonly utilized designs are the posterior step augment (DePuy) and the posterior wedge (Exactech). Although biomechanical analyses of both designs have demonstrated increased stability during loading in cadaveric and simulation models, the step augment (DePuy) has demonstrated increased stability and resistance to loosening.40,41 Although midterm results are not yet available for this newest generation of augmented components, short-term results with 2 to 3 years of follow-up have demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes.28

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

While most commonly indicated for patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, RSA has recently been advocated for older patients with osteoarthritis and B2 glenoids in the setting of an intact rotator cuff. The semi-constrained design of the RSA is a potential solution to the static posterior humeral head subluxation seen in patients with B2 glenoid geometry (Figure 6E).

Technically, RSA is often an easier solution than a TSA with bone grafting because there is usually enough glenoid bone stock for fixation. That said, we always get a CT scan with 3D reconstructions to better appreciate the anatomy. Note that in B2 glenoids, the bone loss is typically posterior and inferior. RSA in the setting of a B2 glenoid is one of the ideal indications to use PSI to ensure ideal placement of the central pin, which is the key to glenoid baseplate positioning. Even when using a RSA, eccentric reaming and/or bone grafting allow for more ideal component placement. Using the same eccentric reaming techniques described above, one should try to ream to place the baseplate at 10° of retroversion. In cases where retroversion cannot be corrected to 10°, graft can be taken from the humeral head, iliac crest, or allograft. A benefit to using bone graft with RSA as opposed to TSA is that the graft can be fashioned to the baseplate, impacted/compressed into the B2 glenoid, and then secured with a central compression screw and peripheral locking screws.

Mizuno and colleagues41 reported a retrospective series of 27 RSAs performed for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis and biconcave glenoid. At a mean follow-up of nearly 5 years, the authors noted significant improvement in Constant scores and shoulder motion with minimal complications. There was no recurrence of posterior instability observed by the time of final follow-up.41

RSA is a promising treatment for primary glenohumeral arthritis with posterior glenoid bone loss and static posterior subluxation in elderly or less active patients, but the longevity of these implants has yet to be established for younger, more active patients and requires further study.

Conclusion

Reconstruction of the B2 glenoid presents a challenging clinical problem that has been associated with poor clinical outcomes and implant survivorship. The high failure rate from glenoid component loosening and subsequent premature implant failure can be substantially decreased with accurate glenoid component positioning and appropriate correction of the pathologic glenoid retroversion. Careful preoperative planning is essential for accurate preparation and execution of the optimal surgical plan. There are many surgical strategies to address the B2 glenoid, but no consensus on the optimal method exists, as the technique should be uniquely customized to the individual’s pathology and surgeon preference (Table). Cases with mild deformity may be corrected with eccentric reaming and TSA, while the more severe deformities may require posterior glenoid bone grafting and/or augmented implants to restore native version. Finally, the RSA is a reliable option to restore stability and address bone deficiency for the severe B2 glenoid in an older, lower demand patient.

1. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

2. Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman GM, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1947-1956.

3. Matsen FA 3rd. Early effectiveness of shoulder arthroplasty for patients who have primary glenohumeral degenerative joint disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(2):260-264.

4. Fenlin JM Jr, Frieman BG. Indications, technique, and results of total shoulder arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1998;29(3):423-434.

5. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: Analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517.

6. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

7. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

8. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

9. Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J, Iannotti JP. The three-dimensional glenoid vault model can estimate normal glenoid version in osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(3):487-491.

10. Walch G, Moraga C, Young A, Castellanos-Rosas J. Results of anatomic nonconstrained prosthesis in primary osteoarthritis with biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1526-1533.

11. Kany J, Katz D. How to deal with glenoid type B2 or C? How to prevent mistakes in implantation of glenoid component? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23(4):379-385.

12. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598.

13. Iannotti JP, Greeson C, Downing D, Sabesan V, Bryan JA. Effect of glenoid deformity on glenoid component placement in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):48-55.

14. Ho JC, Sabesan VJ, Iannotti JP. Glenoid component retroversion is associated with osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e82.

15. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

16. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Defranco M, Walch G. Glenoid version: How to measure it? Validity of different methods in two-dimensional computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1230-1237.

17. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: Conventional radiographs versus computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

18. Budge MD, Lewis GS, Schaefer E, Coquia S, Flemming DJ, Armstrong AD. Comparison of standard two-dimensional and three-dimensional corrected glenoid version measurements. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):577-583.

19. Bokor DJ, O’Sullivan MD, Hazan GJ. Variability of measurement of glenoid version on computed tomography scan. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(6):595-598.

20. Ganapathi A, McCarron JA, Chen X, Iannotti JP. Predicting normal glenoid version from the pathologic scapula: A comparison of 4 methods in 2- and 3-dimensional models. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):234-244.

21. Ricchetti ET, Hendel MD, Collins DN, Iannotti JP. Is premorbid glenoid anatomy altered in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):2932-2939.

22. Hendel MD, Bryan JA, Barsoum WK, et al. Comparison of patient-specific instruments with standard surgical instruments in determining glenoid component position: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2167-2175.

23. Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ, Jackins SE. Can the ream and run procedure improve glenohumeral relationships and function for shoulders with the arthritic triad? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2088-2096.

24. Saltzman MD, Chamberlain AM, Mercer DM, Warme WJ, Bertelsen AL, Matsen FA 3rd. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming in patients 55 years old or less. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):609-615.

25. Gilmer BB, Comstock BA, Jette JL, Warme WJ, Jackins SE, Matsen FA. The prognosis for improvement in comfort and function after the ream-and-run arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis: An analysis of 176 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):e102.

26. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH Jr, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA 3rd. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292.

27. Donohue KW, Ricchetti ET, Iannotti JP. Surgical management of the biconcave (B2) glenoid. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(1):30-39.

28. Clavert P, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Glenoid resurfacing: What are the limits to asymmetric reaming for posterior erosion? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):843-848.

29. Gillespie R, Lyons R, Lazarus M. Eccentric reaming in total shoulder arthroplasty: A cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2009;32(1):21.

30. Neer CS 2nd, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

31. Nowak DD, Bahu MJ, Gardner TR, et al. Simulation of surgical glenoid resurfacing using three-dimensional computed tomography of the arthritic glenohumeral joint: The amount of glenoid retroversion that can be corrected. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):680-688.

32. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833.

33. Walch G, Young AA, Boileau P, Loew M, Gazielly D, Mole D. Patterns of loosening of polyethylene keeled glenoid components after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: Results of a multicenter study with more than five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):145-150.

34. Walch G, Young AA, Melis B, Gazielly D, Loew M, Boileau P. Results of a convex-back cemented keeled glenoid component in primary osteoarthritis: Multicenter study with a follow-up greater than 5 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):385-394.

35. Klika BJ, Wooten CW, Sperling JW, et al. Structural bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1066-1072.

36. Sabesan V, Callanan M, Sharma V, Iannotti JP. Correction of acquired glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis with a standard versus an augmented glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):964-973.

37. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

38. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157.

39. Iannotti JP, Lappin KE, Klotz CL, Reber EW, Swope SW. Liftoff resistance of augmented glenoid components during cyclic fatigue loading in the posterior-superior direction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1530-1536.

40. Knowles NK, Ferreira LM, Athwal GS. Augmented glenoid component designs for type B2 erosions: A computational comparison by volume of bone removal and quality of remaining bone. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):1218-1226.

41. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.

1. Barrett WP, Franklin JL, Jackins SE, Wyss CR, Matsen FA 3rd. Total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(6):865-872.

2. Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, Gartsman GM, Guyatt G, Kirkley A. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(9):1947-1956.

3. Matsen FA 3rd. Early effectiveness of shoulder arthroplasty for patients who have primary glenohumeral degenerative joint disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(2):260-264.

4. Fenlin JM Jr, Frieman BG. Indications, technique, and results of total shoulder arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1998;29(3):423-434.

5. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: Analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(11):1513-1517.

6. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):251-258.

7. Levine WN, Djurasovic M, Glasson JM, Pollock RG, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Hemiarthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Results correlated to degree of glenoid wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(5):449-454.

8. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

9. Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J, Iannotti JP. The three-dimensional glenoid vault model can estimate normal glenoid version in osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(3):487-491.

10. Walch G, Moraga C, Young A, Castellanos-Rosas J. Results of anatomic nonconstrained prosthesis in primary osteoarthritis with biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1526-1533.

11. Kany J, Katz D. How to deal with glenoid type B2 or C? How to prevent mistakes in implantation of glenoid component? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013;23(4):379-385.

12. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598.

13. Iannotti JP, Greeson C, Downing D, Sabesan V, Bryan JA. Effect of glenoid deformity on glenoid component placement in primary shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):48-55.

14. Ho JC, Sabesan VJ, Iannotti JP. Glenoid component retroversion is associated with osteolysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):e82.

15. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

16. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Defranco M, Walch G. Glenoid version: How to measure it? Validity of different methods in two-dimensional computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(8):1230-1237.

17. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: Conventional radiographs versus computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

18. Budge MD, Lewis GS, Schaefer E, Coquia S, Flemming DJ, Armstrong AD. Comparison of standard two-dimensional and three-dimensional corrected glenoid version measurements. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):577-583.

19. Bokor DJ, O’Sullivan MD, Hazan GJ. Variability of measurement of glenoid version on computed tomography scan. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8(6):595-598.

20. Ganapathi A, McCarron JA, Chen X, Iannotti JP. Predicting normal glenoid version from the pathologic scapula: A comparison of 4 methods in 2- and 3-dimensional models. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(2):234-244.

21. Ricchetti ET, Hendel MD, Collins DN, Iannotti JP. Is premorbid glenoid anatomy altered in patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):2932-2939.

22. Hendel MD, Bryan JA, Barsoum WK, et al. Comparison of patient-specific instruments with standard surgical instruments in determining glenoid component position: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2167-2175.

23. Matsen FA 3rd, Warme WJ, Jackins SE. Can the ream and run procedure improve glenohumeral relationships and function for shoulders with the arthritic triad? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2088-2096.

24. Saltzman MD, Chamberlain AM, Mercer DM, Warme WJ, Bertelsen AL, Matsen FA 3rd. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming in patients 55 years old or less. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):609-615.

25. Gilmer BB, Comstock BA, Jette JL, Warme WJ, Jackins SE, Matsen FA. The prognosis for improvement in comfort and function after the ream-and-run arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis: An analysis of 176 consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(14):e102.

26. Lynch JR, Franta AK, Montgomery WH Jr, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA 3rd. Self-assessed outcome at two to four years after shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(6):1284-1292.

27. Donohue KW, Ricchetti ET, Iannotti JP. Surgical management of the biconcave (B2) glenoid. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2016;9(1):30-39.

28. Clavert P, Millett PJ, Warner JJ. Glenoid resurfacing: What are the limits to asymmetric reaming for posterior erosion? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(6):843-848.

29. Gillespie R, Lyons R, Lazarus M. Eccentric reaming in total shoulder arthroplasty: A cadaveric study. Orthopedics. 2009;32(1):21.

30. Neer CS 2nd, Morrison DS. Glenoid bone-grafting in total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1154-1162.

31. Nowak DD, Bahu MJ, Gardner TR, et al. Simulation of surgical glenoid resurfacing using three-dimensional computed tomography of the arthritic glenohumeral joint: The amount of glenoid retroversion that can be corrected. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):680-688.

32. Strauss EJ, Roche C, Flurin PH, Wright T, Zuckerman JD. The glenoid in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(5):819-833.

33. Walch G, Young AA, Boileau P, Loew M, Gazielly D, Mole D. Patterns of loosening of polyethylene keeled glenoid components after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: Results of a multicenter study with more than five years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):145-150.

34. Walch G, Young AA, Melis B, Gazielly D, Loew M, Boileau P. Results of a convex-back cemented keeled glenoid component in primary osteoarthritis: Multicenter study with a follow-up greater than 5 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(3):385-394.

35. Klika BJ, Wooten CW, Sperling JW, et al. Structural bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):1066-1072.

36. Sabesan V, Callanan M, Sharma V, Iannotti JP. Correction of acquired glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis with a standard versus an augmented glenoid component. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):964-973.

37. Steinmann SP, Cofield RH. Bone grafting for glenoid deficiency in total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(5):361-367.

38. Cil A, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Nonstandard glenoid components for bone deficiencies in shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(7):e149-e157.

39. Iannotti JP, Lappin KE, Klotz CL, Reber EW, Swope SW. Liftoff resistance of augmented glenoid components during cyclic fatigue loading in the posterior-superior direction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1530-1536.

40. Knowles NK, Ferreira LM, Athwal GS. Augmented glenoid component designs for type B2 erosions: A computational comparison by volume of bone removal and quality of remaining bone. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(8):1218-1226.

41. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis in patients with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.