User login

Optimizing Patient Positioning During Dermatologic Surgery

Practice Gap

Practical patient positioning is a commonly overlooked method of tension control during excision and repair that allows for easier closure.1 Although positioning is a basic step in dermatologic surgery, it often is difficult and awkward for both the patient and physician. Here, we describe basic principles in patient positioning that increase tension across the surgical site during excision and reduce tension during closure. By reducing the amount of work required for excision and closure, procedures are completed more quickly, which increases efficiency. These techniques should be considered during dermatologic surgery at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities.

Technique: Upper Back Procedures

When removing lesions on the upper back, lying completely prone is uncomfortable for the patient and leaves the shoulders hyperextended.2 Instead, position the patient with the arms extended anteriorly, hugging a pillow, while lying prone or on one side (Figure 1). In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the upper back. In addition, this position is notably more comfortable for the patient. During closure, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the elbow resting at the hip and the ipsilateral arm lying parallel to the torso (Figure 2).

Following procedures on the upper back and shoulders, we typically recommend that the patient wear an arm sling on the ipsilateral side for 1 week. Doing so reliably limits mobility postoperatively and does not require the patient to constantly monitor their movement.

Technique: Lower Extremity Procedures

Anterior Lower Extremity

During excision of a lesion on the anterior lower extremity, we recommend that the patient be positioned with their knee bent and heel resting on the examination table. Ideally, the knee is flexed at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 3).3 In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the anterior lower extremity. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie supine with the knee fully extended and the leg resting on the surgical bed or a pillow.

Posterior Lower Extremity

During excision of lesions on the posterior lower extremity, the patient should be positioned lying prone, with the knee fully extended, resting on the surgical bed or a pillow, which facilitates excision of the lesion by increasing tension across the site. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the leg fully extended for support. The surgical leg should be flexed at the knee at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Despite being an important step, patient positioning is an often-overlooked component of dermatologic surgery. Positioning becomes even more important in areas of high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, where the risk of wound dehiscence and poor scar cosmesis is increased.1 Experienced dermatologic surgeons should utilize patient positioning, taking advantage of tension instead of working against it.

We have found that these 2 simple principles can aid in simplifying the excision and repair processes. Increasing tension across the surgical site during excision reduces the work required by the surgeon to reach the appropriate depth. Conversely, decreased tension across the surgical site decreases the work required for closure. These principles should be considered prior to the procedure; the patient should then be positioned in a way that maximizes tension across the surgical site during excision and minimizes tension across the surgical site during closure.

Incorporating these techniques, especially at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, not only increases efficiency but may also reduce the risk for wound dehiscence once the patient returns home and maintains their normal level of physical activity.

- Rohrer TE, Cook JL, Kaufman AJ. Flaps and Grafts in Dermatologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2007.

- Kantor J. Atlas of Suturing Techniques: Approaches to Surgical Wound, Laceration, and Cosmetic Repair. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Kiwanuka E, Cruz AP. Multistep approach for improved aesthetic and functional outcomes for lower extremity wound closure after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:704-707.

Practice Gap

Practical patient positioning is a commonly overlooked method of tension control during excision and repair that allows for easier closure.1 Although positioning is a basic step in dermatologic surgery, it often is difficult and awkward for both the patient and physician. Here, we describe basic principles in patient positioning that increase tension across the surgical site during excision and reduce tension during closure. By reducing the amount of work required for excision and closure, procedures are completed more quickly, which increases efficiency. These techniques should be considered during dermatologic surgery at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities.

Technique: Upper Back Procedures

When removing lesions on the upper back, lying completely prone is uncomfortable for the patient and leaves the shoulders hyperextended.2 Instead, position the patient with the arms extended anteriorly, hugging a pillow, while lying prone or on one side (Figure 1). In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the upper back. In addition, this position is notably more comfortable for the patient. During closure, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the elbow resting at the hip and the ipsilateral arm lying parallel to the torso (Figure 2).

Following procedures on the upper back and shoulders, we typically recommend that the patient wear an arm sling on the ipsilateral side for 1 week. Doing so reliably limits mobility postoperatively and does not require the patient to constantly monitor their movement.

Technique: Lower Extremity Procedures

Anterior Lower Extremity

During excision of a lesion on the anterior lower extremity, we recommend that the patient be positioned with their knee bent and heel resting on the examination table. Ideally, the knee is flexed at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 3).3 In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the anterior lower extremity. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie supine with the knee fully extended and the leg resting on the surgical bed or a pillow.

Posterior Lower Extremity

During excision of lesions on the posterior lower extremity, the patient should be positioned lying prone, with the knee fully extended, resting on the surgical bed or a pillow, which facilitates excision of the lesion by increasing tension across the site. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the leg fully extended for support. The surgical leg should be flexed at the knee at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Despite being an important step, patient positioning is an often-overlooked component of dermatologic surgery. Positioning becomes even more important in areas of high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, where the risk of wound dehiscence and poor scar cosmesis is increased.1 Experienced dermatologic surgeons should utilize patient positioning, taking advantage of tension instead of working against it.

We have found that these 2 simple principles can aid in simplifying the excision and repair processes. Increasing tension across the surgical site during excision reduces the work required by the surgeon to reach the appropriate depth. Conversely, decreased tension across the surgical site decreases the work required for closure. These principles should be considered prior to the procedure; the patient should then be positioned in a way that maximizes tension across the surgical site during excision and minimizes tension across the surgical site during closure.

Incorporating these techniques, especially at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, not only increases efficiency but may also reduce the risk for wound dehiscence once the patient returns home and maintains their normal level of physical activity.

Practice Gap

Practical patient positioning is a commonly overlooked method of tension control during excision and repair that allows for easier closure.1 Although positioning is a basic step in dermatologic surgery, it often is difficult and awkward for both the patient and physician. Here, we describe basic principles in patient positioning that increase tension across the surgical site during excision and reduce tension during closure. By reducing the amount of work required for excision and closure, procedures are completed more quickly, which increases efficiency. These techniques should be considered during dermatologic surgery at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities.

Technique: Upper Back Procedures

When removing lesions on the upper back, lying completely prone is uncomfortable for the patient and leaves the shoulders hyperextended.2 Instead, position the patient with the arms extended anteriorly, hugging a pillow, while lying prone or on one side (Figure 1). In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the upper back. In addition, this position is notably more comfortable for the patient. During closure, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the elbow resting at the hip and the ipsilateral arm lying parallel to the torso (Figure 2).

Following procedures on the upper back and shoulders, we typically recommend that the patient wear an arm sling on the ipsilateral side for 1 week. Doing so reliably limits mobility postoperatively and does not require the patient to constantly monitor their movement.

Technique: Lower Extremity Procedures

Anterior Lower Extremity

During excision of a lesion on the anterior lower extremity, we recommend that the patient be positioned with their knee bent and heel resting on the examination table. Ideally, the knee is flexed at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 3).3 In this position, excision of the lesion is facilitated by increased tension across the anterior lower extremity. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie supine with the knee fully extended and the leg resting on the surgical bed or a pillow.

Posterior Lower Extremity

During excision of lesions on the posterior lower extremity, the patient should be positioned lying prone, with the knee fully extended, resting on the surgical bed or a pillow, which facilitates excision of the lesion by increasing tension across the site. During closure of these lesions, the patient should lie on the side contralateral to the surgical site, with the leg fully extended for support. The surgical leg should be flexed at the knee at approximately a 45° angle (Figure 4).

Practice Implications

Despite being an important step, patient positioning is an often-overlooked component of dermatologic surgery. Positioning becomes even more important in areas of high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, where the risk of wound dehiscence and poor scar cosmesis is increased.1 Experienced dermatologic surgeons should utilize patient positioning, taking advantage of tension instead of working against it.

We have found that these 2 simple principles can aid in simplifying the excision and repair processes. Increasing tension across the surgical site during excision reduces the work required by the surgeon to reach the appropriate depth. Conversely, decreased tension across the surgical site decreases the work required for closure. These principles should be considered prior to the procedure; the patient should then be positioned in a way that maximizes tension across the surgical site during excision and minimizes tension across the surgical site during closure.

Incorporating these techniques, especially at sites that are subject to both high tension and repetitive motion, such as the upper back and lower extremities, not only increases efficiency but may also reduce the risk for wound dehiscence once the patient returns home and maintains their normal level of physical activity.

- Rohrer TE, Cook JL, Kaufman AJ. Flaps and Grafts in Dermatologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2007.

- Kantor J. Atlas of Suturing Techniques: Approaches to Surgical Wound, Laceration, and Cosmetic Repair. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Kiwanuka E, Cruz AP. Multistep approach for improved aesthetic and functional outcomes for lower extremity wound closure after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:704-707.

- Rohrer TE, Cook JL, Kaufman AJ. Flaps and Grafts in Dermatologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2007.

- Kantor J. Atlas of Suturing Techniques: Approaches to Surgical Wound, Laceration, and Cosmetic Repair. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016.

- Kiwanuka E, Cruz AP. Multistep approach for improved aesthetic and functional outcomes for lower extremity wound closure after Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:704-707.

Cutaneous Metastasis of a Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumor

Case Report

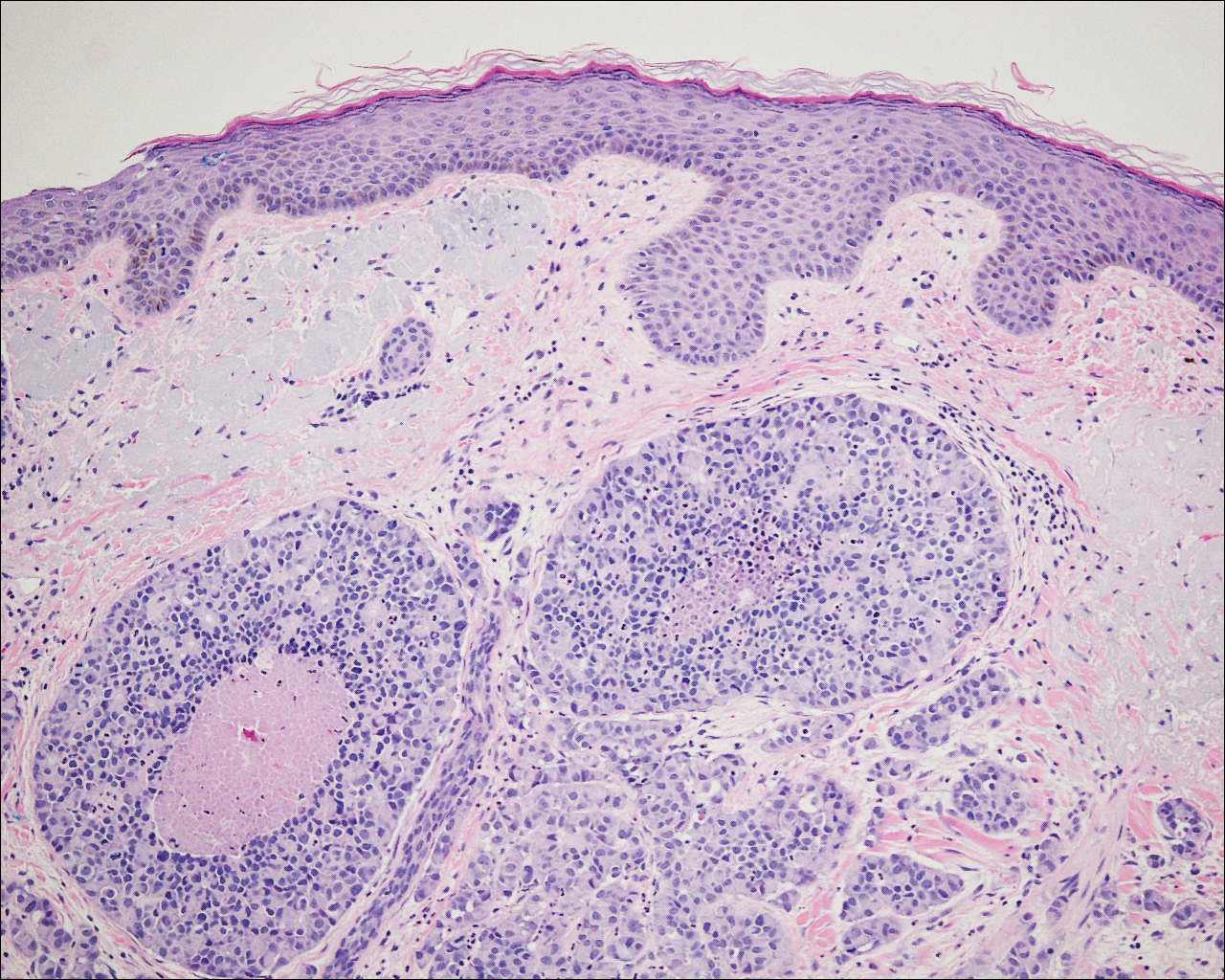

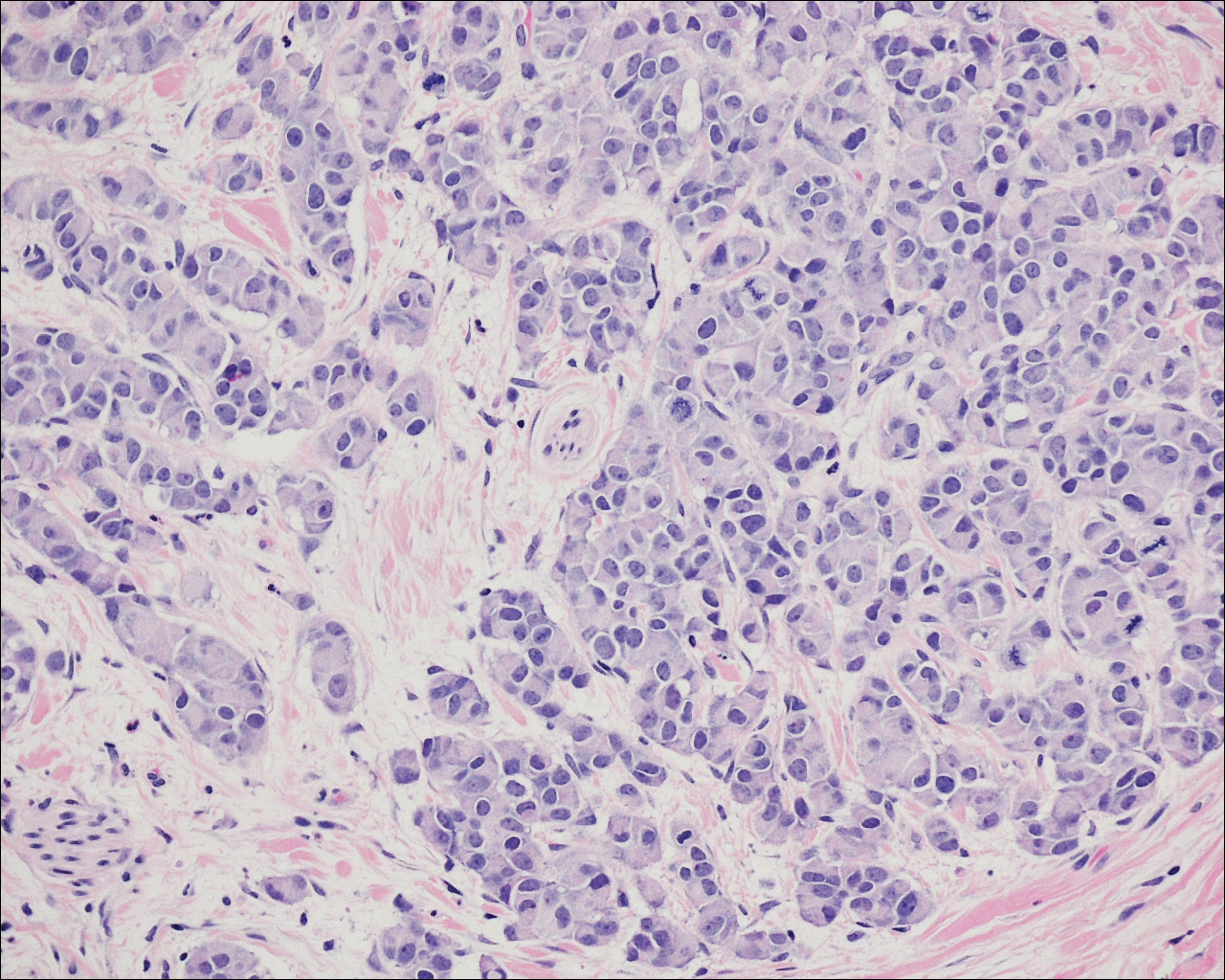

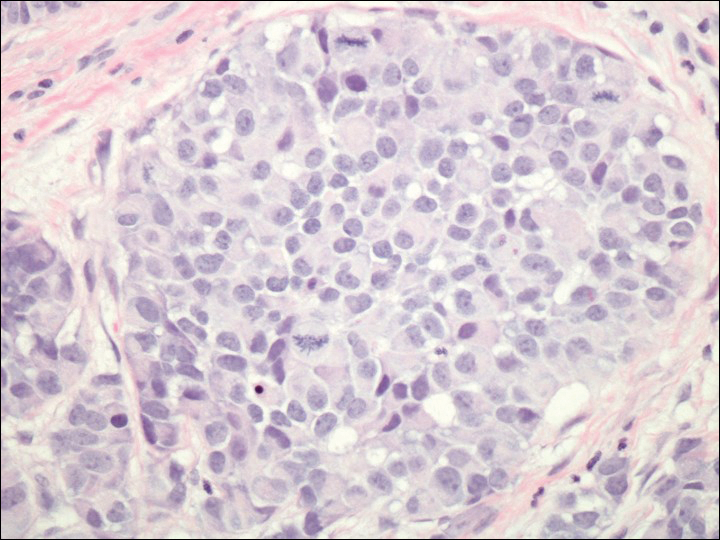

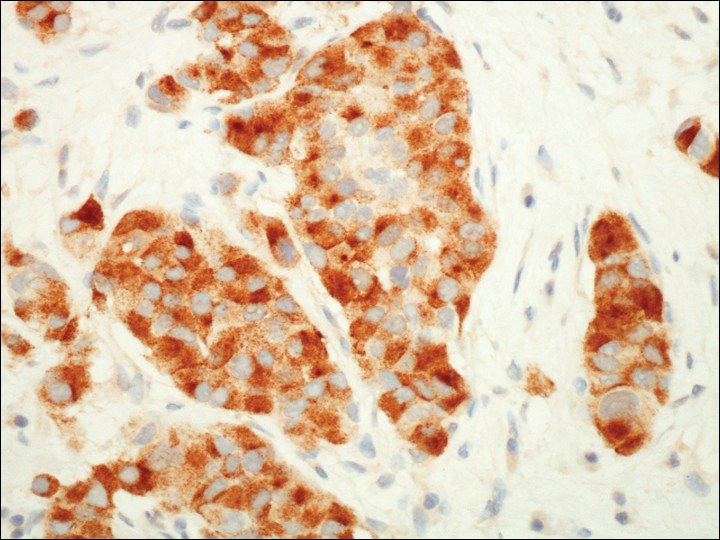

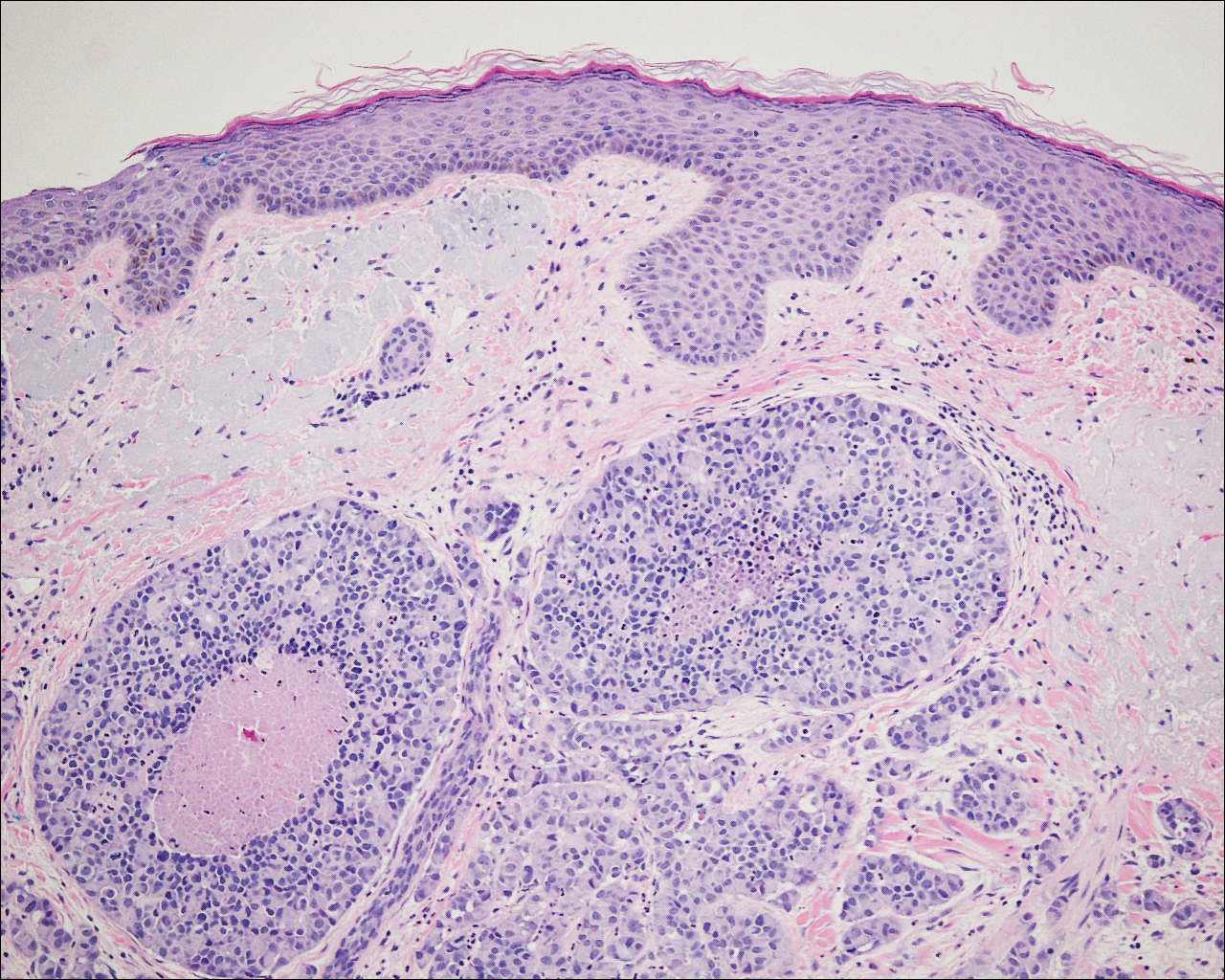

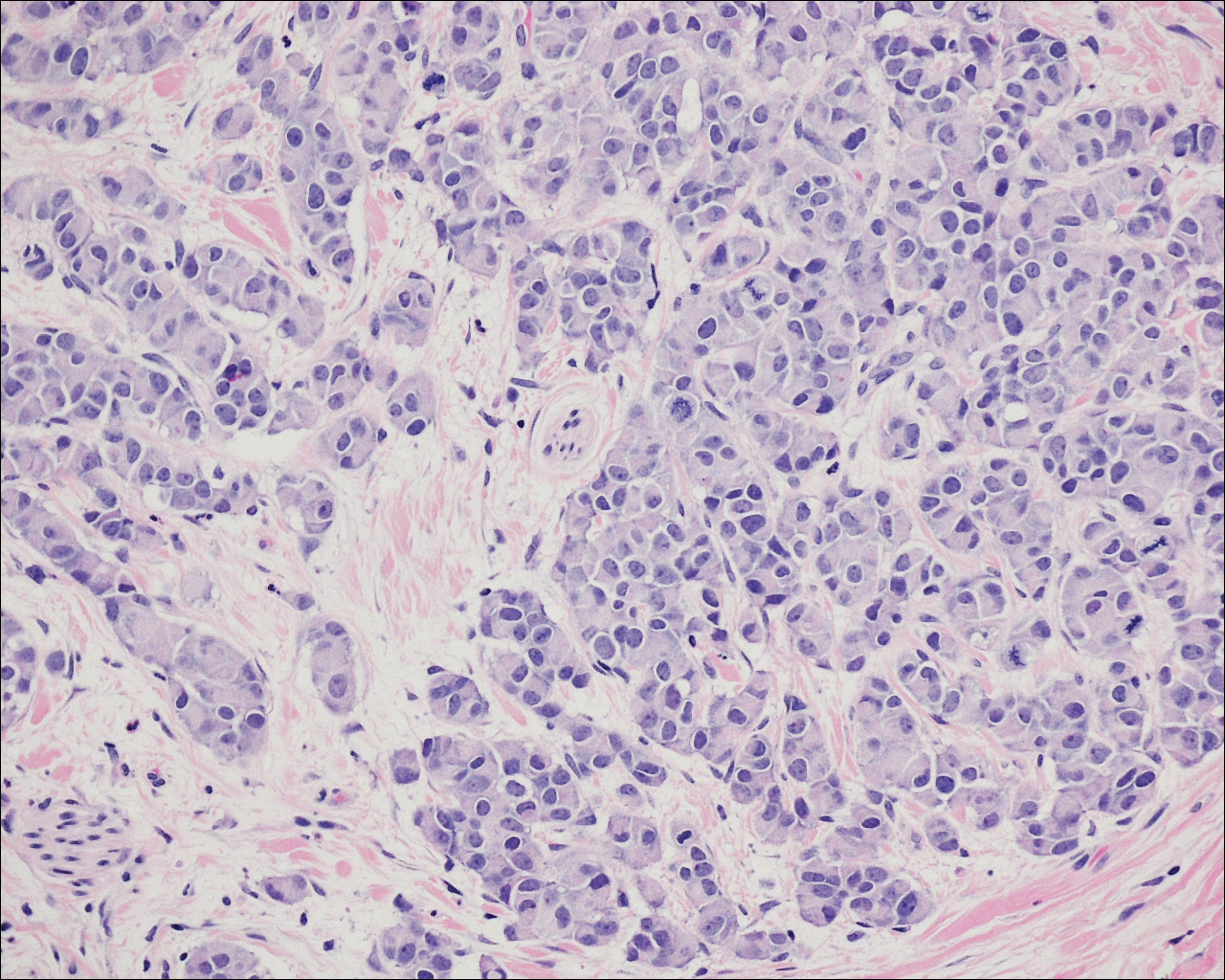

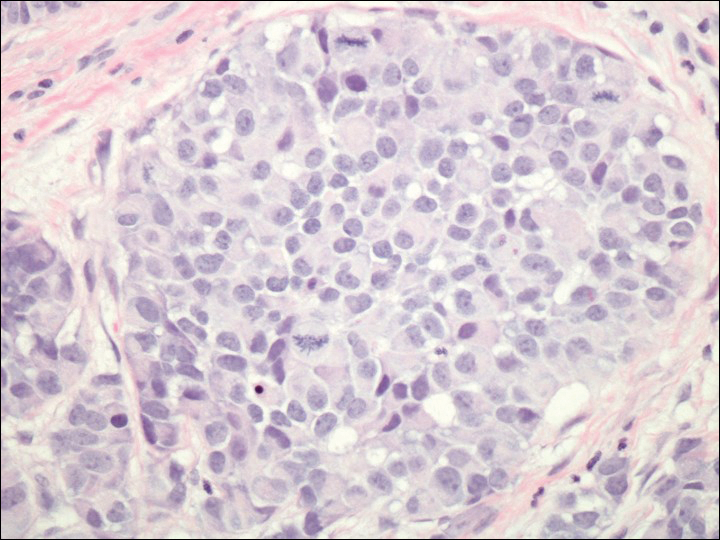

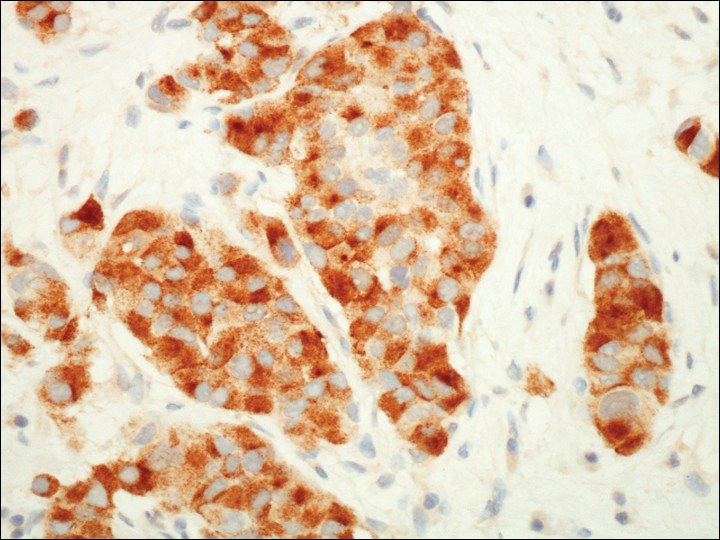

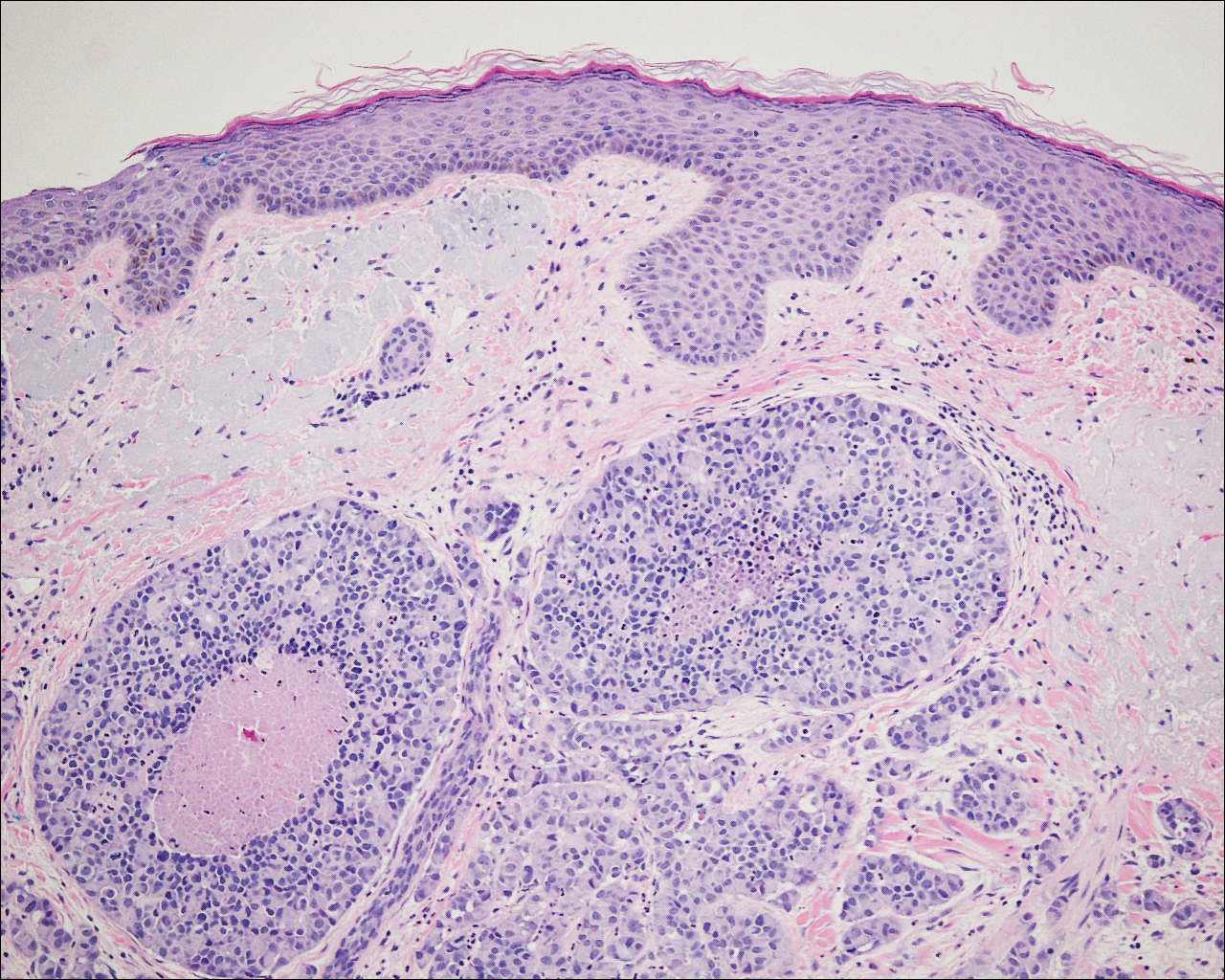

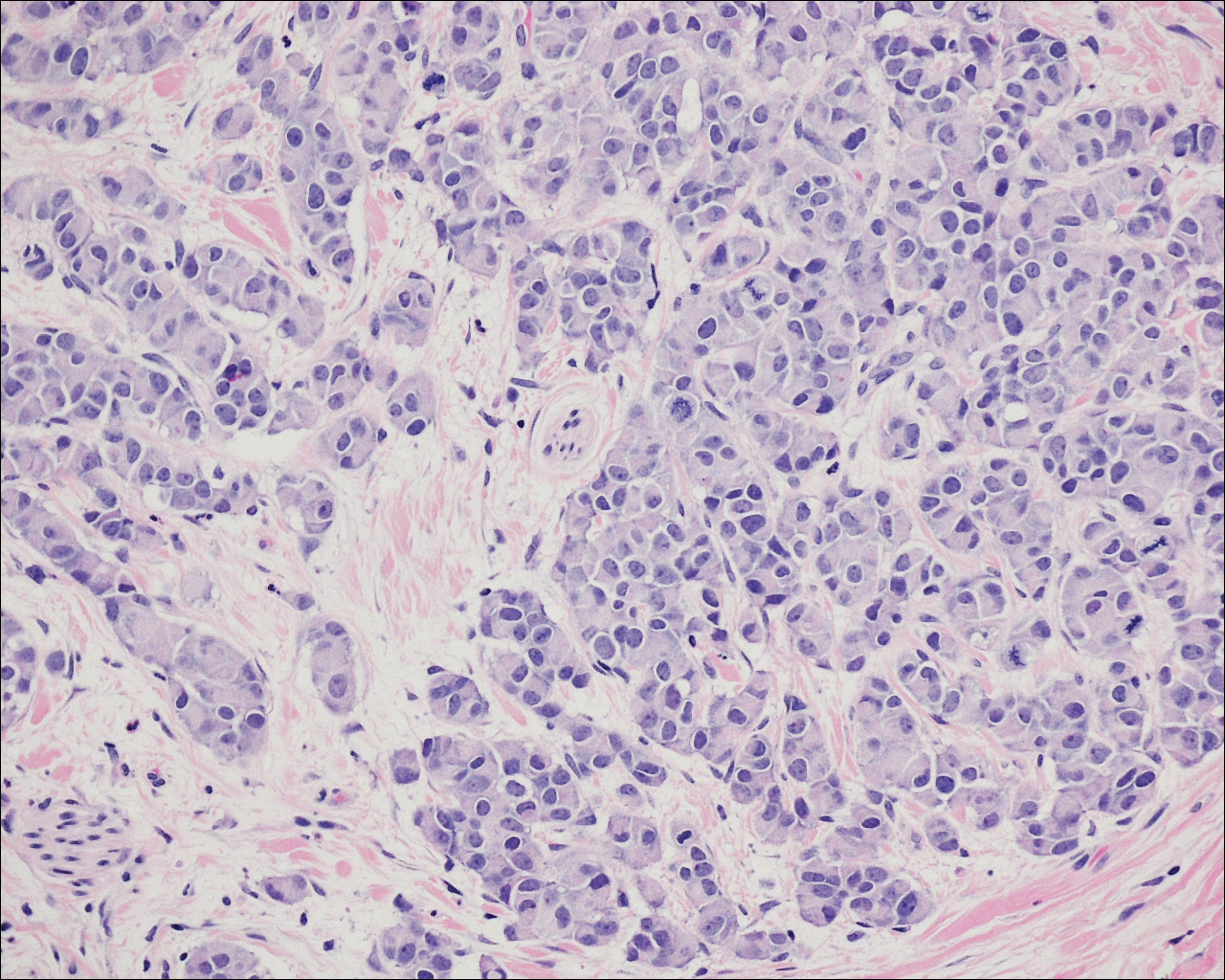

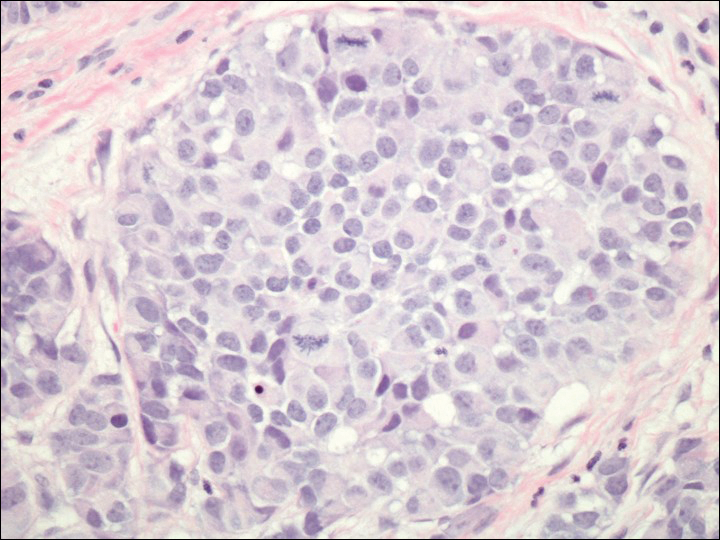

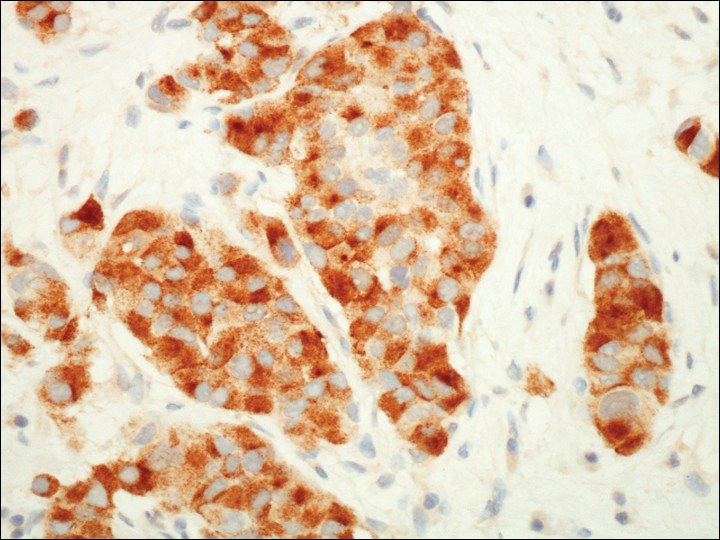

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

Case Report

A 72-year-old white man with a history of pancreatic adenocarcinoma presented for Mohs micrographic surgery of a basal cell carcinoma on the right helix. On the day of the surgery, the patient reported a new, rapidly growing, exquisitely painful lesion on the cheek of 3 to 4 weeks’ duration. Physical examination revealed a 0.8×0.8×0.8-cm, extremely tender, firm, pink papule on the right preauricular cheek. A horizontal deep shave excision was done and the histopathology was remarkable for neoplastic cells with necrosis in the dermis. We observed dermal cellular infiltrates in the form of sheets and nodules, some showing central necrosis (Figure 1). At higher magnification, a trabecular arrangement of cells was seen. These cells had a moderate amount of cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei and rare nucleoli (Figure 2). Mitotic figures were seen at higher magnification (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry of the neoplastic cells exhibited similar positive staining for the neuroendocrine markers chromogranin A and synaptophysin (Figure 4). Staining of the neoplastic cells also was positive for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and cancer antigen 19-9. Villin and caudal type homeobox 2 stains were negative. These results were consistent with cutaneous metastasis from a known pulmonary carcinoid tumor.

On further review of the patient’s medical history, it was discovered that he had undergone a Whipple procedure with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation for pancreatic adenocarcinoma approximately 4 years prior to the current presentation. He was then followed by oncology, and 3 years later a chest computed tomography suggested possible disease progression with a new pulmonary metastasis. This pulmonary lesion was biopsied and immunologic staining was consistent with a primary neuroendocrine neoplasm of the lung, a new carcinoid tumor. The tissue was positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7,TTF-1, cancer antigen 19-9, CD56, synaptophysin, and chromogranin A, and was negative for villin and CK20. By the time he was seen in our clinic, several trials of chemotherapy had failed. Serial computed tomography subsequently demonstrated progression of the lung disease and he later developed malignant pleural effusions. Approximately 6 months after the cutaneous carcinoid metastasis was diagnosed, the patient died of respiratory failure.

Comment

Carcinoid tumors are uncommon neoplasms of neuroendocrine origin that generally arise in the gastrointestinal or bronchopulmonary tracts. Metastases from these primary neoplasms more commonly affect the regional lymph nodes or viscera, with rare reports of cutaneous metastases to the skin. The true incidence of carcinoid tumors with metastasis to the skin is unknown because it is limited to single case reports in the literature.

The clinical presentation of cutaneous carcinoid metastases has been reported most commonly as firm papules of varying sizes with no specific site predilection.1 The color of these lesions has ranged from erythematous to violaceous to brown.2 Several of the reported cases were noted to be extremely tender and painful, while other reports of lesions were noted to be asymptomatic or only mildly pruritic.3-7

Carcinoid syndrome is more common with neoplasms present within the gastrointestinal tract, but it also has been reported with large bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.8,9 Paroxysmal flushing is the most prominent cutaneous manifestation of this syndrome, occurring in 75% of patients.10,11 Other common symptoms include patchy cyanosis, telangiectasia, and pellagralike skin lesions.3 Carcinoid syndrome secondary to bronchial adenomas is thought to differ from gastrointestinal carcinoid neoplasms in that it has prolonged flushing (hours to days instead of minutes) and is characterized by marked anxiety, fever, disorientation, sweating, and lacrimation.8,9

Many cases of cutaneous carcinoid metastases have been accompanied by reports of exquisite tenderness,7 similar to our patient. The pathogenesis of the pain in these lesions is still unclear, but several hypotheses have been established. It has been postulated that perineural invasion by the tumor is responsible for the pain; however, this finding has been inconsistent, as neural involvement also has been present in nonpainful lesions.2,5,7,12 Another theory for the pain is that it is secondary to the release of vasoactive substances and peptide hormones from the carcinoid cells, such as kallikrein and serotonin. Lastly, local tissue necrosis and fibrosis also have been suggested as possible etiologies.7

The histology of cutaneous carcinoid metastases typically resembles the primary lesion and may demonstrate fascicles of spindle cells with focal areas of necrosis, mild atypia, and a relatively low mitotic rate.10 Other neoplasms such as Merkel cell carcinoma and carcinoidlike sebaceous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. A primary malignant peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor or a primary cutaneous carcinoid tumor is less common but should be considered. Differing from carcinoid tumors, Merkel cell carcinomas usually have a higher mitotic rate and positive staining for CK20. The sebaceous neoplasms with a carcinoidlike pattern may appear histologically similar, requiring immunohistochemical evaluation with monoclonal antibodies such as D2-40.13 A diffuse granular cytoplasmic reaction to chromogranin A is characteristic of carcinoid tumors. Synaptophysin and TTF-1 also are positive in carcinoid tumors, with TTF-1 being highly specific for neuroendocrine tumors of the lung.10

Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies are more common from carcinomas of the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and breasts.5 Occasionally, the cutaneous metastasis will develop directly over the underlying malignancy. Our case of cutaneous metastasis of a carcinoid tumor presented as an exquisitely tender and painful papule on the cheek. The histology of the lesion was consistent with the known carcinoid tumor of the lung. Because these lesions are extremely uncommon, it is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose these metastases.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

- Blochin E, Stein JA, Wang NS. Atypical carcinoid metastasis to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:735-739.

- Rodriguez G, Villamizar R. Carcinoid tumor with skin metastasis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:263-269.

- Archer CB, Rauch HJ, Allen MH, et al. Ultrastructural features of metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Cutan Pathol. 1984;11:485-490.

- Archer CB, Wells RS, MacDonald DM. Metastatic cutaneous carcinoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2, pt 2):363-366.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis:a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Oleksowicz L, Morris JC, Phelps RG, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid presenting as multiple subcutaneous nodules. Tumori. 1990;76:44-47.

- Zuetenhorst JM, van Velthuysen ML, Rutgers EJ, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of pain caused by skin metastases in neuroendocrine tumours. Neth J Med. 2002;60:207-211.

- Melmon KL. Kinins: one of the many mediators of the carcinoid spectrum. Gastroenterology. 1968;55:545-548.

- Zuetenhorst JM, Taal BG. Metastatic carcinoid tumors: a clinical review. Oncologist. 2005;10:123-131.

- Sabir S, James WD, Schuchter LM. Cutaneous manifestations of cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:139-144.

- Braverman IM. Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18:1-19.

- Santi R, Massi D, Mazzoni F, et al. Skin metastasis from typical carcinoid tumor of the lung. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:418-422.

- Kazakov DV, Kutzner H, Rütten A, et al. Carcinoid-like pattern in sebaceous neoplasms. another distinctive, previously unrecognized pattern in extraocular sebaceous carcinoma and sebaceoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:195-203.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors are extremely rare, and clinical presentation can vary. They can present as firm papules ranging in color from pink to brown, can be painful, and could occur at any site.

- It is imperative to obtain an accurate clinical history and use the appropriate immunohistochemical panel to correctly diagnose cutaneous metastases of carcinoid tumors.

- Neoplasms within the gastrointestinal tract commonly present with carcinoid syndrome, but it also has been observed with bronchial carcinoid tumors and with metastatic disease.