User login

Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis Mimicking Livedo Racemosa

To the Editor:

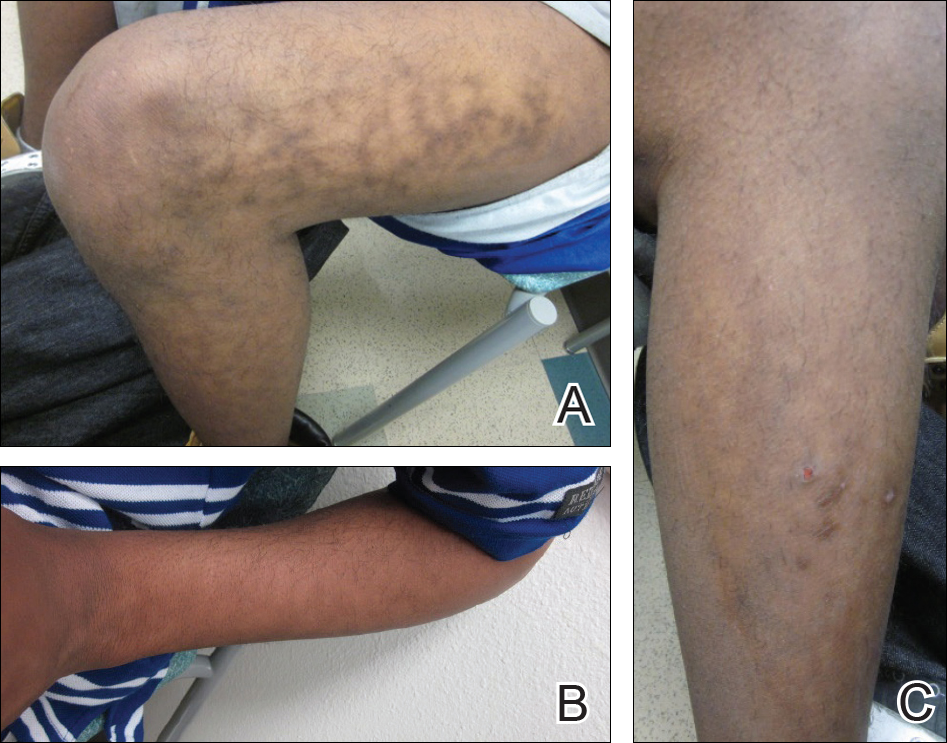

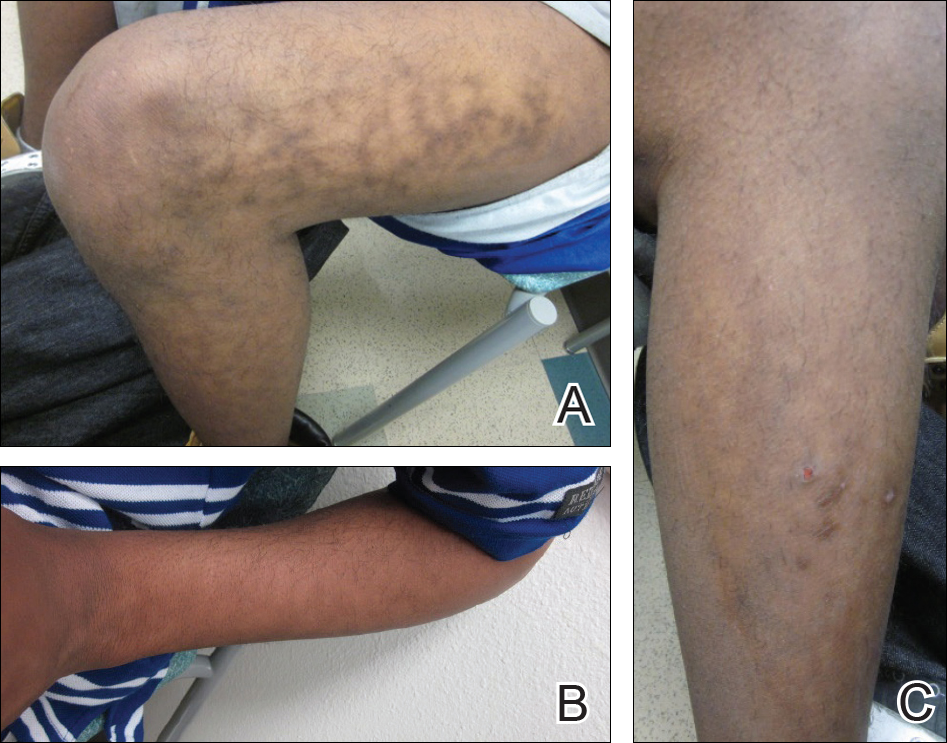

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

Practice Points

- Clinicians should include terra firma-forme dermatosis in the differential diagnosis of any hyperpigmented condition, regardless of pattern of presentation.

- Clean the skin with an alcohol wipe to rule out a diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Painful Nonhealing Vulvar and Perianal Erosions

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

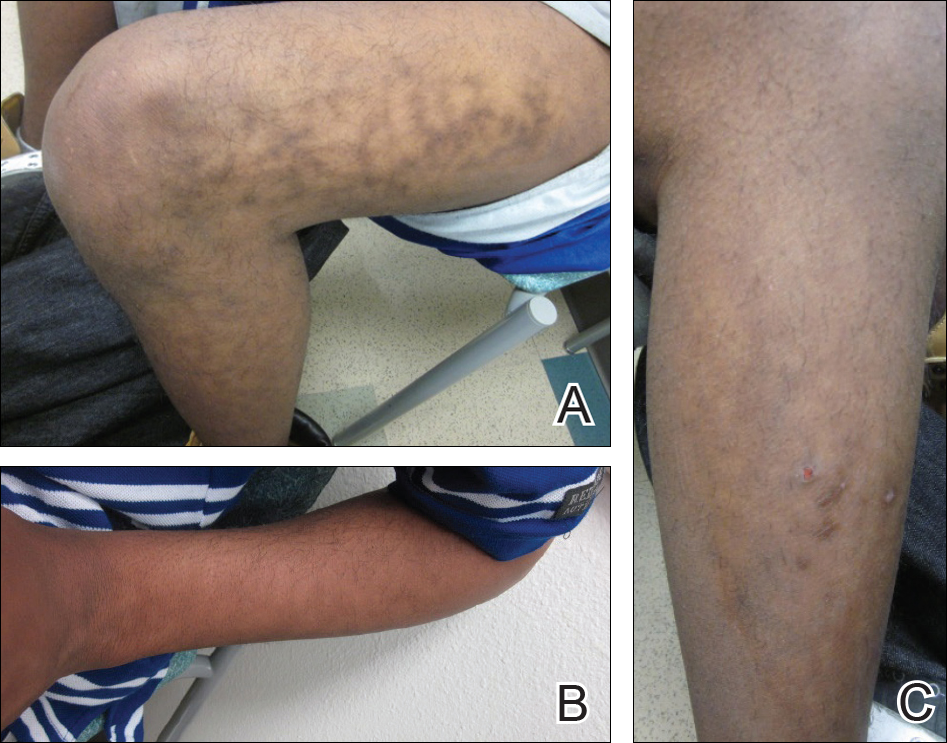

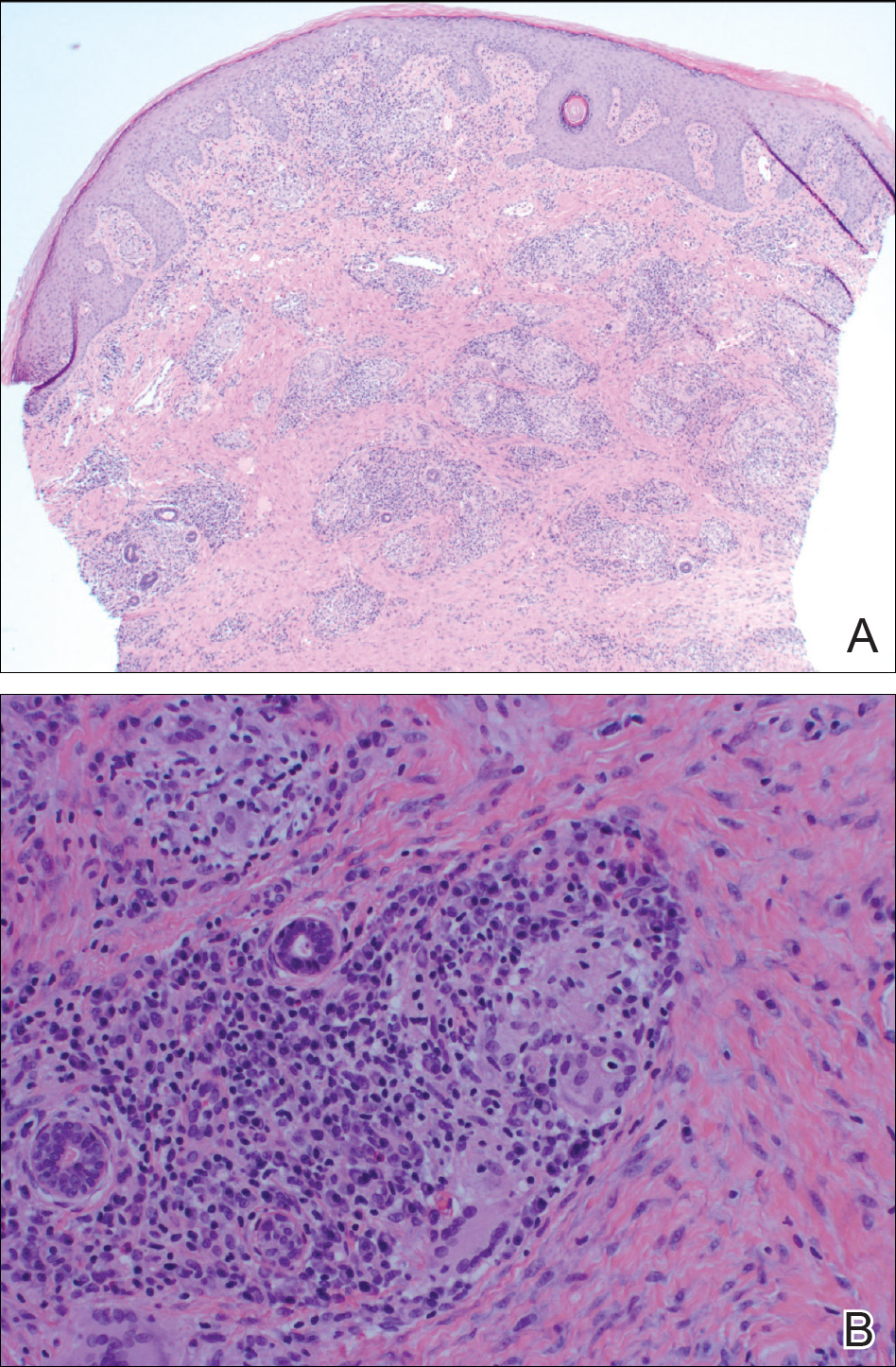

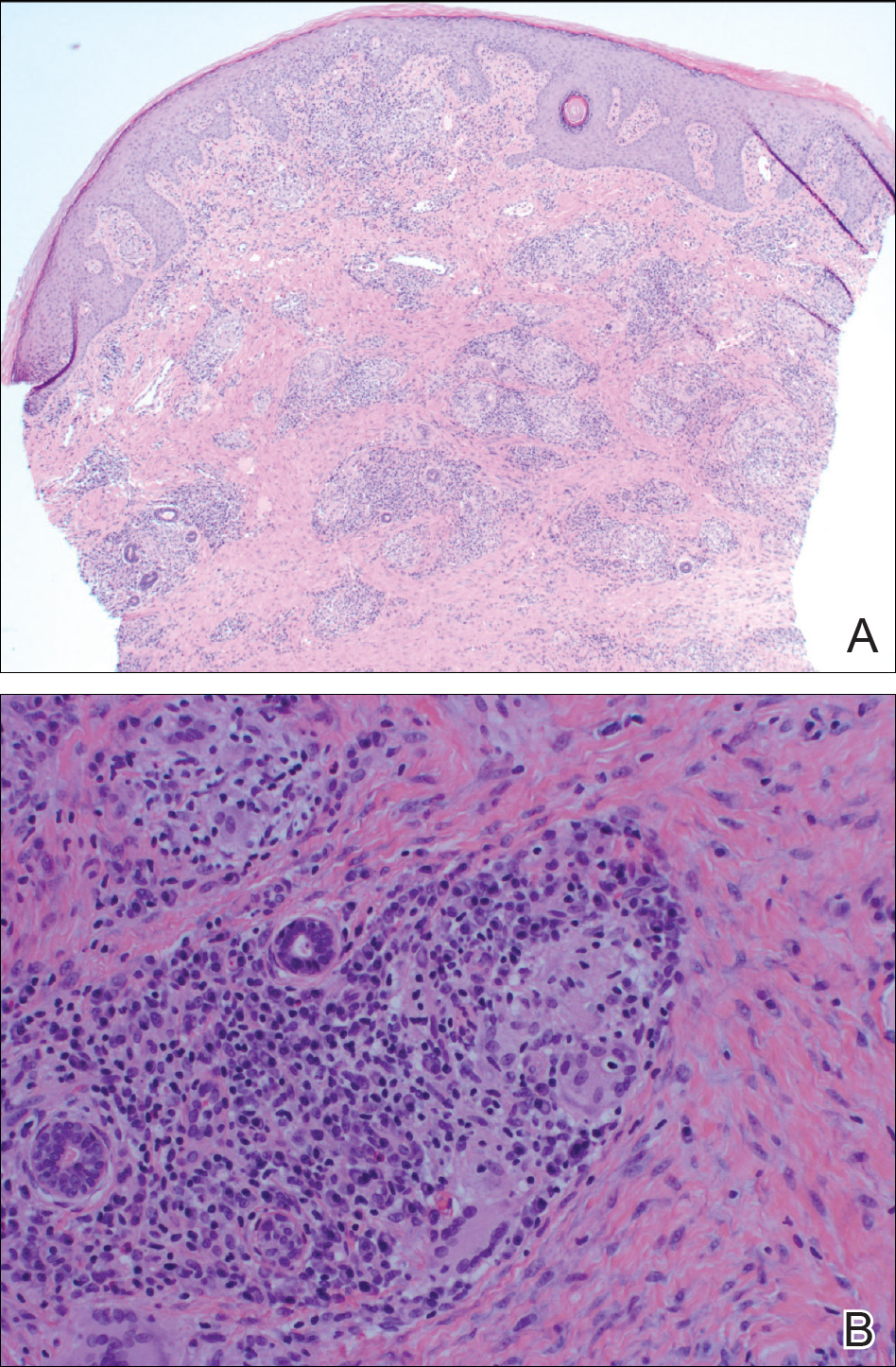

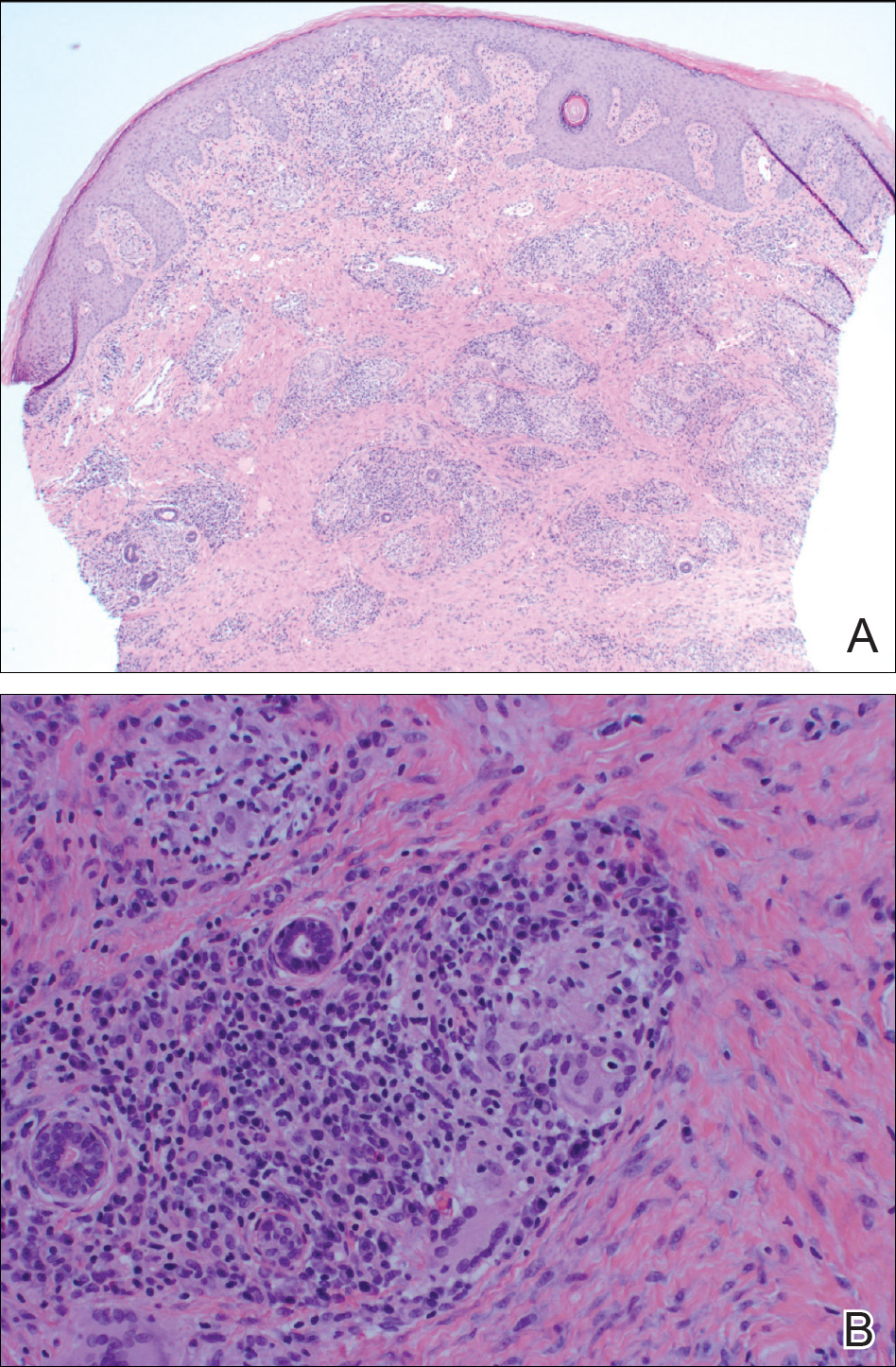

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Crohn Disease

A punch biopsy of the vulvar skin revealed epidermal hyperplasia with moderate spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes and neutrophils in the epidermis. A brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleate foreign body-type giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils in a granulomatous pattern also were present in the dermis (Figure). Periodic acid-Schiff and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. Given the history of Crohn disease (CD) and the characteristic dermal noncaseating granulomas on histology, the patient was diagnosed with cutaneous CD.

Although the patient was offered a topical corticosteroid, she deferred topical therapy. Given the lack of response to adalimumab, the gastroenterology department switched the patient to a treatment of infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Azathioprine was discontinued and the patient was switched to intramuscular methotrexate 25 mg/mL weekly. Slow reepithelialization of the vulvar and perianal erosions occurred on this regimen.

Although CD has numerous cutaneous features, cutaneous CD, also known as metastatic CD, is the rarest cutaneous manifestation of CD.1 This disease process is characterized by noncaseating granulomatous cutaneous lesions that are not contiguous with the affected gastrointestinal tract.2 The pathogenesis of cutaneous CD is unknown. Young adults tend to be more predisposed to developing cutaneous CD, likely due to the age distribution of CD.3

Cutaneous CD commonly presents in patients with a well-established history of gastrointestinal CD but occasionally can be the presenting sign of CD.1 The most common sites of involvement are the legs, vulva, penis, trunk, face, and intertriginous areas. Cutaneous CD findings can be divided into 2 subgroups: genital and nongenital lesions. Genital findings involve ulceration, erythema, edema, and fissuring of the vulva, labia, clitoris, scrotum, penis, and perineum. Nongenital cutaneous manifestations include ulcers; erythematous papules, plaques, and nodules; abscesslike lesions; and lichenoid papules.4,5 The severity of cutaneous lesions does not correlate to the severity of gastrointestinal disease; however, colon involvement is more common in patients with cutaneous CD.6

Histologically, cutaneous CD presents as noncaseating granulomatous inflammation in the papillary and reticular dermis. These granulomas consist of epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells with a lymphocytic infiltrate.5

Given the rarity of cutaneous CD, treatment approach is based on anecdotal evidence from case reports and case series. For a single lesion or localized disease, topical superpotent or intralesional steroids are recommended for initial therapy.3 Oral metronidazole also is an effective treatment and can be combined with topical or intralesional steroids.7 For disseminated disease, systemic corticosteroids have shown efficacy.3 Other reported treatment options include oral corticosteroids, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, infliximab, and adalimumab. If monotherapy fails, combination therapy may be needed. Surgical debridement may be attempted if medical therapy fails but is complicated by wound dehiscence and disease recurrence.3

Although genital ulcers can be a presentation of Behçet disease and genital herpes infection, genital nodules and plaques are not typical for these 2 diseases. Also, the patient did not have oral ulcers, which is a common feature of Behçet disease. Genital sarcoidosis is extremely rare, and cutaneous CD was more likely given the patient's medical history. Finally, Jacquet dermatitis is more common in children, and patients with this condition typically have history of fecal and urinary incontinence.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

- Teixeira M, Machado S, Lago P, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1074-1076.

- Stingeni L, Neve D, Bassotti G, et al. Cutaneous Crohn's disease successfully treated with adalimumab [published online Sep 15, 2015]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2016;30:E72-E74.

- Kurtzman DJ, Jones T, Fangru L, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review and approach to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:804-813.

- Hagen JW, Swoger JM, Grandinetti LM. Cutaneous manifestations of Crohn disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:417-431.

- Palamaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn's disease: a review [published online June 19, 2008]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033-1043.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease, part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33.

- Abide JM. Metastatic Crohn disease: clearance with metronidazole. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:448-449.

A 38-year-old woman with a history of Crohn disease presented with painful nonhealing vulvar and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. The erosions developed 4 months after discontinuing adalimumab for a planned surgery. During this time, the patient also had an exacerbation of Crohn colitis and developed an anal fistula. Prior to this break in adalimumab, the patient's Crohn disease was well controlled on adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, azathioprine 100 mg daily, and mesalamine 4.8 g daily. Despite restarting adalimumab and therapy with multiple antibiotics (ie, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin), the erosions persisted. On physical examination erythematous plaques and nodules were present at the vulvar (top) and perianal (bottom) skin. In addition, well-demarcated erosions measuring 20 mm and 80 mm were present on the vulvar and perianal skin, respectively. Human immunodeficiency virus screening and rapid plasma reagin were negative.