User login

Pembrolizumab-Induced Lobular Panniculitis in the Setting of Metastatic Melanoma

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

To the Editor:

Pembrolizumab is an anti–programmed death receptor 1 humanized monoclonal antibody used for treating advanced or metastatic melanoma.1 It is associated with several immune-related adverse events because it blocks a T-cell receptor checkpoint.2 The most common dermatologic immune-related adverse event seen with anti–programmed death receptor 1 medications is a nonspecific morbilliform rash, usually seen after the second treatment cycle; however, pruritus, vitiligo, bullous disorders, and lichenoid reactions also have been reported.3 We report a case of pembrolizumab-induced, self-limited lobular panniculitis in a patient with metastatic melanoma.

A 37-year-old woman with malignant melanoma presented with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules on the hips and legs of 2 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). Twelve years prior to the current presentation, she was diagnosed with metastases to the cecum, lung, and brain. A review of systems was otherwise negative. She had been receiving pembrolizumab infusions (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for the last 2.7 years as second-line therapy after previously undergoing chemotherapy, radiation, and resection. She was not taking oral contraceptives or other hormone-based medications and did not report any new medications.

Laboratory testing was negative for infectious processes including Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and Streptococcus due to recent upper respiratory infection. Punch biopsy of a left shin lesion revealed a lobular panniculitis with lymphohistiocytic inflammation, a focal lymphocytic vasculitis, and small granulomas (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff, Gram, and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. After ruling out alternative causes, the etiology of the panniculitis was deemed to be a pembrolizumab side effect. The patient was treated conservatively with ibuprofen; pembrolizumab was not discontinued. Two weeks later, the panniculitis had resolved without additional treatment. She remains on pembrolizumab and is doing well.

Panniculitis is known to be associated with certain BRAF inhibitors used for the treatment of melanoma positive for the BRAF V600E mutation, including vemurafenib and dabrafenib.4,5 Reports of panniculitis in the setting of pembrolizumab are limited and are seen within the larger context of sarcoidosis. One patient on pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma developed granulomatous lobular panniculitis with oligoarthritis, high fever, and hilar/mediastinal adenopathy, consistent with pembrolizumab-induced sarcoidosis. It developed after her second pembrolizumab infusion and resolved with prednisone and temporary pembrolizumab cessation.6 In another case, pembrolizumab triggered a flare of sarcoidosis with similar granulomatous subcutaneous nodules in a patient with stage IV lymphoma who was previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis but lacked cutaneous manifestations. The lesions resolved with prednisone therapy.7

Chest computed tomography was normal in our patient, and she reported no systemic symptoms. Additional laboratory studies to evaluate for sarcoidosis were not obtained. Furthermore, the lesions quickly resolved despite continued use of pembrolizumab. We report this case to highlight that pembrolizumab may induce an isolated, self-limited lobular panniculitis years after medication initiation.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

- Poole RM. Pembrolizumab: first global approval. Drugs. 2014;74:1973-1981.

- Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;54:139-148.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Ramani NS, Curry JL, Kapil J, et al. Panniculitis with necrotizing granulomata in a patient on BRAF inhibitor (dabrafenib) therapy for metastatic melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:E96-E99.

- Burillo-Martinez S, Morales-Raya C, Prieto-Barrios M, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced extensive panniculitis and nevus regression: two novel cutaneous manifestations of the post-immunotherapy granulomatous reactions spectrum. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:721-722.

- Cotliar J, Querfeld C, Boswell WJ, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated sarcoidosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:290-293.

Practice Points

- Pembrolizumab may cause lobular panniculitis years after treatment initiation.

- Pembrolizumab-induced lobular panniculitis may self-resolve without discontinuing the medication.

Growing Subcutaneous Mass on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

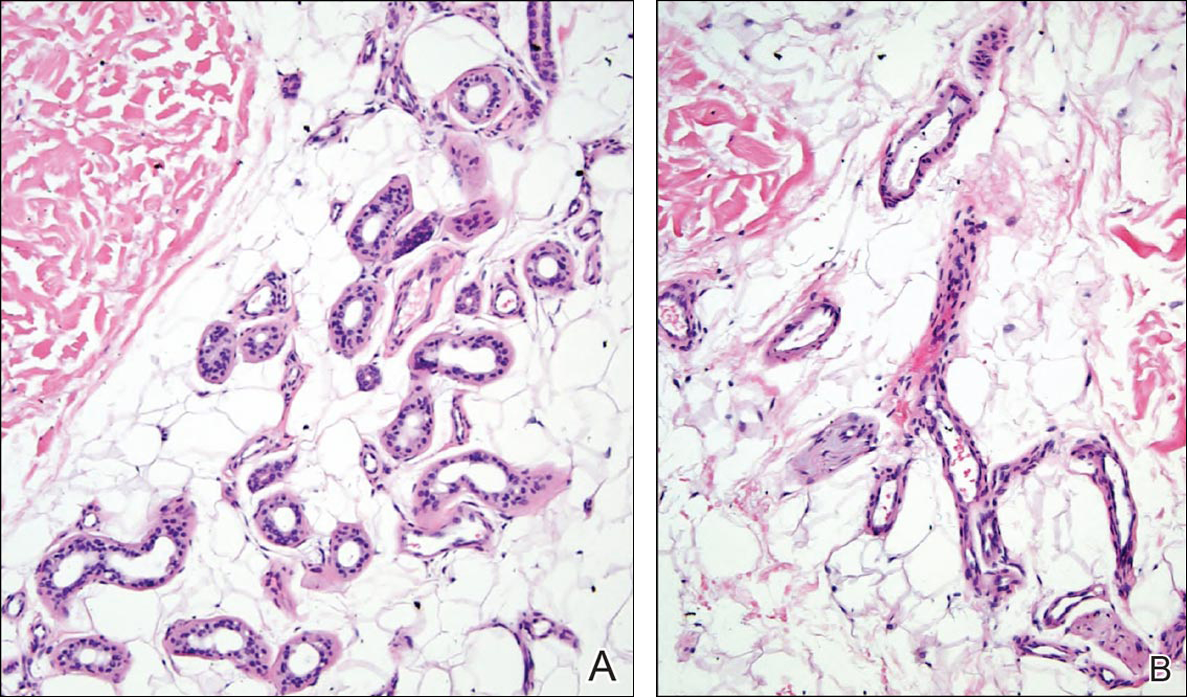

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

The Diagnosis: Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma

Given the progression of symptoms 3 months prior to presentation, an excisional biopsy was performed (Figure 1). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed prominent eccrine sweat glands and vessels surrounded by superficially located adipose tissue in the mid and deep dermis (Figure 2).

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is an uncommon benign tumor typically located on the arms and legs or trunk. It is usually solitary, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.1,2 Most cases are diagnosed in childhood as either congenital or acquired lesions. However, EAHs can develop in adulthood and have been described in patients up to 70 years of age.3 The median age of diagnosis is 10 years,2 indicating that EAH is primarily a pediatric tumor. There is no gender predilection.

Approximately 35% to 66% of patients report pain, pruritus, or hyperhidrosis associated with EAHs, though this incidence may be overrepresented because patients tend to present when the lesions become symptomatic.2-5 The pain is attributed to nerve fibers infiltrating the tumor. Hypertrichosis also has been described and is thought to be due to hair follicles within the hamartoma.

Histologically, EAHs are characterized by normal-appearing eccrine glands mingled with venules and capillaries. Additional variable pathologic findings include lipomatous, pilar, lymphatic, or mucinous features.2 Other vascular anomalies such as hemangiomas or arteriovenous malformations occasionally have been described in association with EAH. The vessels stain for ulex europaeus 1 and factor VIII. Eccrine glands stain for S-100 protein, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and cytokeratin CAM 5.2. In light of a publication proposing that EAH is a lymphatic proliferation,6 a D2-40 stain was performed on the specimen and was negative.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma has been reported to grow mainly during childhood, puberty, or pregnancy, presumably due to hormonal influences.7 There are few reports of EAH enlarging in middle-aged adults, and even fewer without pain during the growth phase. It is unclear what triggered the growth in our otherwise healthy postmenopausal patient.

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma does not have malignant potential and thus treatment is optional and based on relief of symptoms. Simple excision of the EAH usually is curative, but recurrences can occur.4 Botulinum toxin also has been used to treat hyperhidrosis in tumors that are too large for resection. Treatment with lasers such as the pulsed dye laser and Nd:YAG laser has not been successful.8 A case of spontaneous regression has been reported.1

Liposuction was considered in our patient given the substantial adipose tissue on biopsy. The patient ultimately declined treatment. This case highlights that EAH can present in adulthood and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of an enlarging but otherwise asymptomatic vascular tumor.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.

- Tay YK, Sim CS. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma associated with spontaneous regression. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:516-517.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:429-435.

- Shin J, Jang YH, Kim SC, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a review of ten cases [published online May 10, 2013]. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:208-212.

- Lin YT, Chen CM, Yang CH, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a retrospective study of 15 cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35:167-177.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Wang L, Wang S, Gao T, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma is a lymphatic proliferation. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23:614-617.

- Kikusawa A, Oka M, Taguchi K, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with sudden enlargement and pain in an adolescent girl after menarche [published online October 1, 2011]. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:266-268.

- Barco D, Baselga E, Alegre M, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:241-243.