User login

Metastatic Melanoma Mimicking Eruptive Keratoacanthomas

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

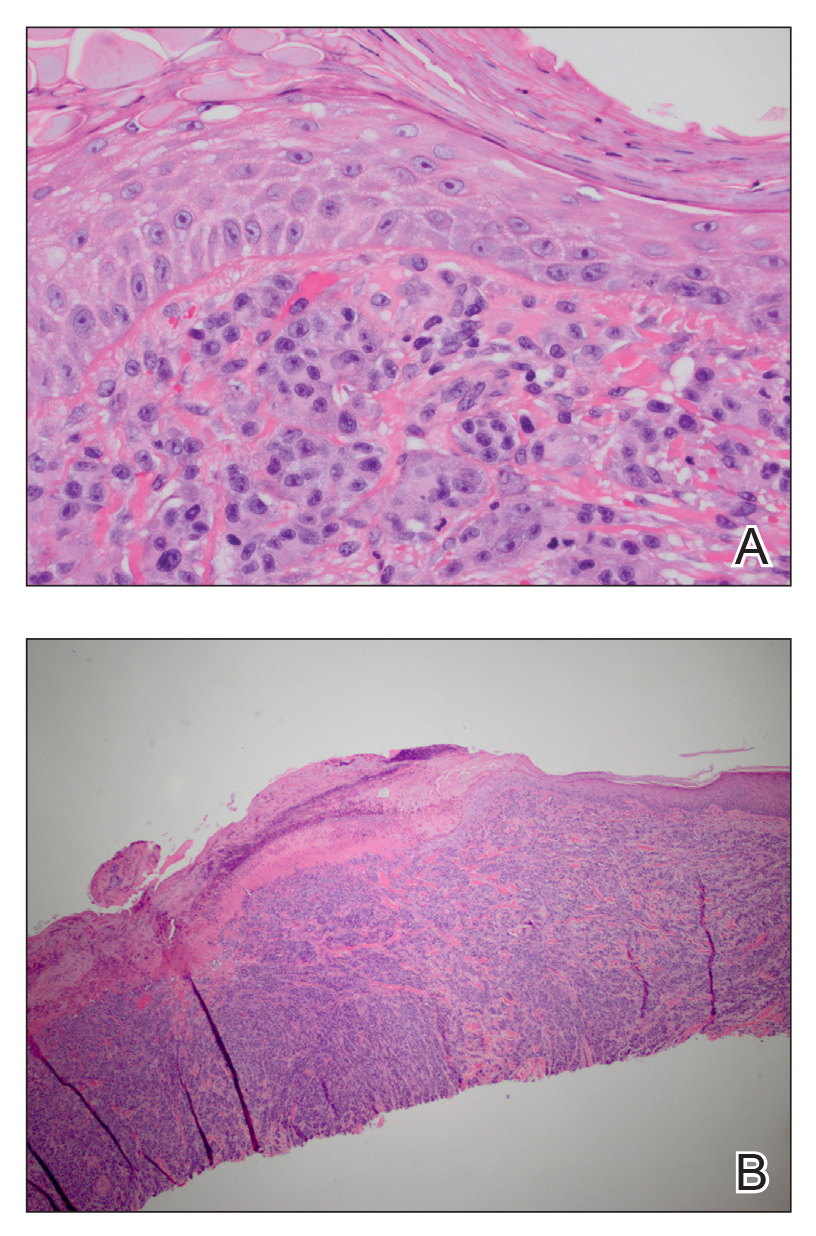

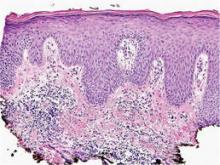

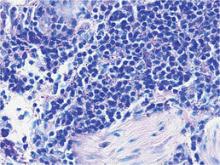

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

To the Editor:

Melanoma is the third most common skin cancer. It is estimated that 18% of melanoma patients will develop skin metastases, with skin being the first site of involvement in 56% of cases.1 Of all cancers, it is estimated that 5% will develop skin metastases. It is the presenting sign in nearly 1% of visceral cancers.2 Melanoma and nonmelanoma metastases can have sundry presentations. We present a case of metastatic melanoma with multiple keratoacanthoma (KA)–like skin lesions in a patient with a known history of nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC) as well as melanoma.

A 76-year-old man with a history of pT2aNXMX melanoma on the left upper back presented for a routine 3-month follow-up and reported several new asymptomatic bumps on the chest, back, and right upper extremity within the last 2 weeks. The melanoma was removed via wide local excision 2 years prior at an outside facility with a Breslow depth of 1.05 mm and a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. The mitotic rate or ulceration status was unknown. He also had a history of several NMSCs, as well as a medical history of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, and ventricular tachycardia with cardiac defibrillator placement. Physical examination revealed 5 pink, volcano-shaped nodules with central keratotic plugs on the upper back (Figure 1), chest, and right upper extremity, in addition to 1 pink pearly nodule on the right side of the chest. The history and appearance of the lesions were suspicious for eruptive KAs. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence at the prior melanoma and NMSC sites.

A deep shave skin biopsy was performed at all 6 sites. Histopathology showed a diffuse dermal infiltrate of elongated nests of melanocytes and nonnested melanocytes. Marked cytologic atypia and ulceration were present. Minimal connection to the overlying epidermis and a lack of junctional nests was noted. Immunohistochemical studies revealed scattered positivity for Melan-A and negative staining for AE1, AE3, cytokeratin 5, and cytokeratin 6 at all 6 sites (Figure 2). A subsequent metastatic workup showed widespread metastatic disease in the liver, bone, lung, and inferior vena cava. Computed tomography of the head was unremarkable. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was not performed due to the cardiac defibrillator. The patient’s lactate dehydrogenase level showed a mild increase compared to 2 months prior to the metastatic melanoma diagnosis (144 U/L vs 207 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]).

The patient had no systemic symptoms at follow-up 5 weeks later. He was already evaluated by an oncologist and received his first dose of ipilimumab. He was BRAF-mutation negative. He had developed 2 new skin metastases. Five of 6 initially biopsied metastases returned and were growing; they were tender and friable with intermittent bleeding. He was subsequently referred to surgical oncology for excision of symptomatic nodules as palliative care.

Although melanoma is well known to metastasize years and even decades later, KA-like lesions have not been reported as manifestations of metastatic melanoma.4,5 Our patient likely had a primary amelanotic melanoma, as the medical records from the outside facility stated that basal cell carcinoma was ruled out via biopsy. The amelanotic nature of the primary melanoma may have influenced the amelanotic appearance of the metastases. Our patient had no signs of immunosuppression that could have contributed to the sudden skin metastases.

Depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases (eg, satellitosis, in-transit disease, distant cutaneous metastases), the location prevalence of the primary melanoma varies. In a study of 4865 melanoma patients who were diagnosed and followed prospectively over a 30-year period, skin metastases were mostly locoregional and presentation on the leg and foot were disproportionate.1 In contrast, the trunk was overrepresented for distant metastases. Distant metastases also were more associated with concurrent metastases to the viscera.1 Accordingly, a patient’s prognosis and management will differ depending on the subtype of cutaneous metastases.

Eruptive or multiple KAs classically have been associated with the Grzybowski variant, the Ferguson-Smith familial variant, and Muir-Torre syndrome. It was reported as a paraneoplastic syndrome associated with colon cancer, ovarian cancer, and once with myelodysplastic syndrome.3 Keratoacanthomas are being classified as well-differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and have metastatic potential. A biopsy is recommended to diagnose KAs as opposed to historically being monitored for resolution. A skin biopsy is the standard of care in management of KAs.

In addition to being associated with Muir-Torre syndrome and classified as a paraneoplastic syndrome,3 eruptive KAs can occur following skin resurfacing for actinic damage, fractional photothermolysis, cryotherapy, Jessner peels, and trichloroacetic acid peels.6 A couple other uncommon settings include a case report of an arc welder with job-associated radiation and multiple reports of tattoo-induced KAs.7,8 There is the new increasingly common association of squamous cell carcinomas with BRAF inhibitors, such as vemurafenib, for metastatic melanoma.9

In a 2012 review article on cutaneous metastases, Riahi and Cohen10 found 8 cases of cutaneous metastases presenting as KA-like lesions; none were metastatic melanoma. All were solitary lesions, not multiple lesions, as in our patient. The sources were lung (3 cases), breast, esophagus, chondrosarcoma, bronchial, and mesothelioma. The most common location was the upper lip. Additionally, similar to our patient, they behaved clinically as KAs with rapid growth and keratotic plugs and were asymptomatic.10

Metastatic melanoma may mimic many other cutaneous processes that may make the diagnosis more difficult. Our case indicates that cutaneous metastases may mimic KAs. Although multiple KA-like lesions can spontaneously occur, a paraneoplastic syndrome and other underlying etiologies should be considered.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

- Savoia P, Fava P, Nardò T, et al. Skin metastases of malignant melanoma: a clinical and prognostic study. Melanoma Res. 2009;19:321-326.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Behzad M, Michl C, Pfützner W. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:359-360.

- Cheung WL, Patel RR, Leonard A, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a detailed morphologic analysis with clinicopathologic correlation of 75 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:33-39.

- Ferrari A, Piccolo D, Fargnoli MC, et al. Cutaneous amelanotic melanoma metastasis and dermatofibromas showing a dotted vascular pattern. Acta Dermato Venereologica. 2004;84:164-165.

- Mohr B, Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J. Eruptive keratoacanthoma after Jessner’s and trichloroacetic acid peel for actinic keratosis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:331-333.

- Wolfe CM, Green WH, Cognetta AB, et al. Multiple squamous cell carcinomas and eruptive keratoacanthomas in an arc welder. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:328-330.

- Kluger N, Phan A, Debarbieux S, et al. Skin cancers arising in tattoos: coincidental or not? Dermatology. 2008;217:219-221.

- Mays R, Curry J, Kim K, et al. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas after vemurafenib therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:419-422.

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Clinical manifestations of cutaneous metastases: a review with special emphasis on cutaneous metastases mimicking keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:103-112.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastatic melanoma can have variable clinical presentations.

- Patients with a history of melanoma should be monitored closely with a low threshold for biopsy of new skin lesions.

Identifying Melanoma With Dermoscopy

Using Dermoscopy to Identify Melanoma and Improve Diagnostic Discrimination (FULL)

From 1982 to 2011, the melanoma incidence rate doubled in the US.1 In 2018, an estimated 87,290 cases of melanoma in situ and 91,270 cases of invasive melanoma will be diagnosed in the US, and 9,320 deaths will be attributable to melanoma.2 Early detection of melanoma is critically important to reduce melanoma-related mortality, with 5-year survival rates as high as 97% at stage 1A vs a 20% 5-year survival when there is distant metastasis.2,3 Melanoma is particularly relevant for medical providers working with veterans because melanoma disproportionately affects service members with an incidence rate ratio of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.40-1.86) compared with that of the general population.4

Biopsy is the definitive diagnostic tool for melanoma. Histologic analysis differentiates melanoma from seborrheic keratoses, pigmented nevi, dermatofibromas, and other pigmented lesions that can resemble melanoma on clinical examination. However, biopsy must be used judiciously as unnecessary biopsies contribute to health care costs and leave scars, which can have psychosocial implications. With benign nevi outnumbering melanoma about 2 million to 1, biopsy is indicated once a threshold of suspicion is obtained.5

Dermoscopic Tool

Dermoscopy is a microscopy-based tool to improve noninvasive diagnostic discrimination of skin lesions based on color and structure analysis. Coloration provides an indication of the composition of elements present in the skin with keratin appearing yellow, blood appearing red, and collagen appearing white. Coloration also suggests pigment depth as melanin appears black when located in the stratum corneum, brown when located deeper in the epidermis, and blue when located in the dermis.6 Finally, characteristic histopathologic alterations in the dermoepidermal junction, rete ridges, pigment-containing cells, and/or melanocyte granules that occur in melanoma are recognizable with dermoscopy.6

In 2001, Bafounta and colleagues performed the first meta-analysis on the efficacy of dermoscopy compared with that of clinical evaluation, finding that dermoscopy performed specifically by dermatology-trained clinicians improved the accuracy of identifying melanoma from an odds ratio of 16 (95% CI, 9-31) with naked eye examination to 76 (95% CI, 25-223) with dermoscopy.7

More recently, Terushkin and colleagues demonstrated that diagnosis specificity improves when a general dermatologist is trained in dermoscopic pattern recognition. Naked eye examination produced a benign to malignant ratio (BMR) of 18.4:1, indicating that about 18 of 19 biopsies considered suspicious for melanoma ultimately yielded benign melanocytic lesions. Although the BMR for the general dermatologist experienced an increase after dermoscopy training, the ratio eventually decreased to 7.9:1.8

Dermoscopic Analysis

Some of the common patterns recognized in melanoma are demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is a close-up of a patient’s upper back showing a solitary asymmetric melanocytic lesion containing multiple red, brown, black, and blue hues.

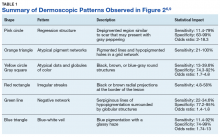

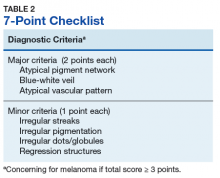

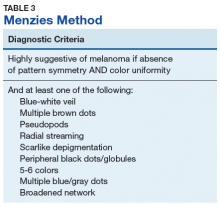

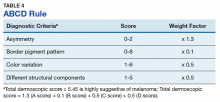

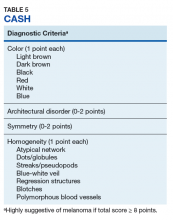

Pattern analysis, the dermoscopic interpretation method preferred by pigmented lesion specialists, requires simultaneously assessing numerous lesion patterns that vary depending on body site.10 Alternative dermoscopic algorithms that focus on the most common features of melanoma have been developed to aid practitioners with the interpretation of dermoscopy findings: the 7-point checklist, the Menzies method, the ABCD rule, and the CASH algorithm (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5).

Argenziano and colleagues developed the 7-point checklist in 1998. Two points are assigned to the lesion for each of the major criteria and 1 point for each minor criteria.

The Menzies method was developed by Menzies and colleagues in 1996. To be classified as melanoma, the pigmented lesion must show an absence of pattern symmetry and color uniformity while simultaneously exhibiting at least one of the following: blue-white veil, multiple brown dots, pseudopods, radial streaming, scarlike depigmentation, peripheral block dots/globules, 5 to 6 colors, multiple blue/gray dots, and a broadened network.12

The ABCD rule is a more technical dermoscopic evaluation algorithm developed in 1994 by Stolz and colleagues. This method yields a numeric value called the total dermoscopic score (TDS) based on Asymmetry, Border pigment pattern, Color variation, and 5 Different structural components.

Henning and colleagues developed the CASH algorithm in 2006 with the intention of assisting less experienced dermoscopy users with lesion evaluation.14 This algorithm tallies points for Color, Architectural disorder, Symmetry, and Homogeneity. One point is attributed to a lesion for each light brown, dark brown, black, red, white, and/or blue region present. Architectural disorder is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 indicating the absence of or minimal architectural disorder, 1 indicating moderate disorder, and 2 indicating marked disorder. Symmetry is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial symmetry, 1 point assigned to a lesion that exhibits monoaxial symmetry, and 2 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial asymmetry. Finally, 1 point is attributed to a lesion for evidence of each of the following: atypical network, dots/globules, streaks/pseudopods, blue-white veil, regression structures, blotches > 10% of the overall lesion size, and polymorphous blood vessels. The lesion in Figure 2 scores 16 points out of the maximum total CASH score of 17. Any lesion scoring 8 or more is suggestive of malignant melanoma.14

Finally, the TADA method was developed by Rogers and colleagues in 2016.15 This method uses sequential questions to evaluate lesions. First, “Does the lesion exhibit clear dermoscopic evidence of an angioma, dermatofibroma, or seborrheic keratosis?” If “yes,” then no additional dermoscopic evaluation is necessary, and it is recommended to monitor the lesion. If the answer to the first question is “no,” then ask, “Does the lesion exhibit architectural disorder?” The presence of architectural disorder is based on an overall impression of the lesion, which includes symmetry with regard to structures and colors. Any lesion deemed to exhibit architectural disorder should be biopsied. If the lesion has no architectural disorder, the third question is, “Does the lesion contain any starburst patterns, blue-black or gray coloration, shiny white structures, negative networks, ulcers or erosions, and/or vessels?” If “yes,” then the lesion should be biopsied. Since the lesion in Figure 2 exhibits marked architectural disorder in terms of symmetry and color, analysis of the lesion with the TADA method would yield a recommendation for biopsy.15

Dermoscopy in Practice

A. Bernard Ackerman, MD, a key figure in the modern era of dermatopathology, wrote an editorial for the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 1985 titled “No one should die of malignant melanoma.” The editorial highlighted that the visual changes associated with melanoma often manifest years prior to malignant invasion and advocated that all physicians should have competence in melanoma detection, specifically mentioning the importance of training primary care physicians (PCPs), dermatologists, and pathologists in this regard.16 This sentiment is equally as true now as it was in 1985.

Naked eye examination paired with an evaluation of patient risk factors for melanoma, including fair skin types, significant sun exposure history, history of sunburn, geographic location, and personal and family history of melanoma, are the foundation of melanoma detection efforts.17 Studies suggest that the triage skills of PCPs could be improved in regard to the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Primary care residents, for instance, did not accurately diagnose 40% of malignant melanoma cases.18,19 Additionally, a meta-analysis demonstrated that PCP accuracy when diagnosing malignant melanoma ranged between 49% and 80%, significantly less than the 85% to 89% exhibited by practicing dermatologists.19 Dermoscopy could be incorporated as an element of the skin examination to enhance lesion discrimination among PCPs, as it has proven use in dermatologic practice.

Dermoscopy is not readily used by PCPs. A survey study of 705 family practitioners in the US performed by Morris and colleagues demonstrated that only 8.3% of participants currently use a dermatoscope to evaluate pigmented lesions.20 The most common barriers to dermoscopy use cited by PCPs in the US include the cost of the dermatoscope, the time required to acquire proficiency, and the lack of financial reimbursement.16 True utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs is higher than this figure suggests due to the number of PCPs who access dermoscopic evaluations via teledermatology. All 21 Veterans Integrated Services Networks of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system, for instance, participate in teledermatology and jointly employ more than 1,150 trained telehealth clinical technicians who created a collective 107,000 teledermatology encounters with and without dermoscopy for evaluation by dermatologists in the most recent fiscal year(Martin Weinstock, written communication, October 2017). Nonetheless, it is necessary to determine the contribution that wider utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs would have on melanoma surveillance.

Studies show that dermoscopic algorithms improve the sensitivity while slightly decreasing the specificity of PCPs to detect melanoma compared with that of the naked eye examination. Dolianitis and colleagues demonstrated that a baseline sensitivity of 60.9% for melanoma detection improved to 85.4% with the 7-point checklist, 85.4% with Menzies method, and 77.5% with the ABCD rule, while the baseline specificity of 85.4% moderated to 73.0%, 77.7%, and 80.4%, respectively, among 61 medical practitioners after studying dermoscopy techniques from 2 CDs.21 Westerhoff and colleagues performed a randomized controlled trial with 74 PCPs to determine the effect of a minimal intervention on melanoma diagnostic accuracy. The intervention consisted of providing participants in the experimental group with an atlas of microscopic features common to melanoma to be read at the participants’ leisure, a 1-hour presentation on microscopy, and a 25-questionpractice quiz. Participants randomized to the intervention group improved their diagnostic accuracy from 57.8% to 75.9% with the use of dermoscopy. This group also experiencedimproved accuracy in its clinical diagnosis of melanoma from 54.6% to 62.7%.22

Argenziano and colleagues demonstrated similar results after PCPs attended a 4-hour workshop on dermoscopy. The 73 PCPs in this study evaluated 2,522 lesions randomized to naked eye examination or dermoscopy. The BMR, calculated from the data provided, improved from 12.6:1 to 10.5:1, respectively, when dermoscopy was incorporated into lesion analysis, while the sensitivity increased from 54.1% to 79.2% and the negative predictive value increased from 95.8% to 98.1%. It is important to note that the BMR and negative predictive value improved in tandem, indicating that PCPs were more discriminatory with their referrals for evaluation by dermatology while capturing a greater percentage of melanomas.23

These studies are not without limitations that preclude broad generalizations. For example, Dolianitis and colleagues and Westerhoff and colleagues provided participants with dermoscopic images of the lesions to be evaluated instead of requiring personal use of a dermatoscope, whereas the study by Argenziano and colleagues incorporated only 6 histopathologically proven malignant melanomas into each of the naked eye examination and the experimental dermoscopy groups.21-23 Yet these studies suggest that broader use of dermoscopy among PCPs could improve the accuracy of melanoma detection given clinically relevant training.

Several additional studies identify positive correlations associated with dermoscopy use among PCPs. A recent survey of 425 French general practitioners found that 8% of the study participants acknowledged owning a dermatoscope. Dermatoscope owners spent a statistically significant longer time analyzing each pigmented skin lesions, exhibited greater confidence in their analysis of pigmented lesions, and issued fewer overall referrals to dermatologists.24

Similarly, Rosendahl and colleagues evaluated the number needed to treat (NNT) (equivalent to the BMR) among 193 Australian PCPs and found that the NNT was inversely correlated to the frequency with which the physicians used dermoscopy. However, it was difficult to determine the definitive cause of the reduced NNT in this study because a similar effect was observed when NNT was evaluated based on general practitioner subspecialization.25 Again, despite limitations, these studies suggest that increased dermoscopy use among PCPs could reduce the morbidity of lifelong scarring as well as the short-term anxiety associated with a possible melanoma diagnosis.

Limitations

Even in the hands of a trained dermatologist, dermoscopy has limitations. Featureless melanoma is a term applied to melanoma lesions bereft of classical findings on both naked eye examination and dermoscopy. Menzies, a dermatologic pioneer in dermoscopy, acknowledged this limitation in 1996 while showing that 8% of melanomas evaded dermoscopic detection. He proceeded to discuss the importance of clinical history in melanoma detection because all of the featureless melanomas exhibited recent changes in size, shape, and/or color.26 More recently, sequential dermoscopy (mole mapping) imaging has been implemented to successfully identify these lesions.27 Thus, dermoscopy cannot replace dermatologists trained in the art of visual assessment with honed clinical diagnostic acumen. Rather, dermoscopy is a tool to enhance the assessment of clinically suspicious lesions and aid diagnostic discrimination of uncertain pigmented lesions.

Conclusion

Primary care physicians are on the frontline of medicine and often the first to have the opportunity to detect the presence of melanoma. Notably, 52.2% of the 884.7 million medical office visits performed annually in the US are with PCPs.28 Despite the benefits, dermoscopy is not uniformly used by dermatologists in the US. Of dermatologists practicing for more than 20 years, 76.2% use dermoscopy compared with 97.8% of dermatologists in practice for less than 5 years. This illustrates an increased use in tandem with dermatology residencies integrating dermoscopy training as a component of the curriculum, showing the importance of incorporating dermoscopy into medical school and residency training for PCPs..29-31 Guidelines regarding dermoscopy training and dermoscopic evaluation algorithms should be established, routinely taught in medical education, and actively incorporated into training curriculum for PCPs in order to improve patient care and realize the potential health care savings associated with the early diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. Dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations present a viable opportunity within the VHA to expedite access to care for veterans and simultaneously offer evaluative feedback on lesions to referring PCPs, as skilled, dermoscopy-trained dermatologists render the diagnoses. Given the devastating mortality rate of melanoma, continued multidisciplinary education on identifying melanoma is of the utmost importance for patient care. Widespread implementation of dermoscopy and dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations could save lives and slow the ever-increasing economic burden associated with melanoma treatment, costing $1.467 billion in 2016.32

1. Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, Watson M, Massetti GM, Richardson LC. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections-United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(21):591-596.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2018.

4. Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, Lewis DR, Phillips CJ. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179(3):247-253.

5. Thomas L, Puig S. Dermoscopy, digital dermoscopy and other diagnostic tools in the early detection of melanoma and follow-up of high-risk skin cancer patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(218):14-21.

6. Marghoob AA, Usatine RP, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(7):441-450.

7. Bafounta ML, Beauchet A, Aegerter P, Saiag P. Is dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) useful for the diagnosis of melanoma? Results of a meta-analysis using techniques adapted to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(10):1343-1350.

8. Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, Kopf AW, Cohen DE, Polsky D. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):343-344.

9. Wolner ZJ, Yélamos O, Liopyris K, Rogers T, Marchetti MA, Marghoob AA. Enhancing skin cancer diagnosis with dermoscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(4):417-437.

10. Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):981-984.

11. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, De Giorgi V, Sammarco E, Delfino M. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(12):1563-1570.

12. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, Crotty KA, McCarthy WH. Frequency and morphologic characteristics of invasive melanomas lacking specific surface microscopic features. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(10):1178-1182.

13. Nachbar F, Stolz W, Merkle T, et al. The ABCD rule of dermatoscopy. High prospective value in the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(4):551-559.

14. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):45-52.

15. Rogers T, Marino M, Dusza SW, Bajaj S, Marchetti MA, Marghoob A. Triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm (TADA) for skin cancer screening. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(2):39-46.

16. Ackerman AB. No one should die of malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(1):115-116.

17. Gandini S, Sera F, Cattaruzza MS, et al. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II: sun exposure. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(1):45-60.

18. Gerbert B, Maurer T, Berger T, et al. Primary care physicians as gatekeepers in managed care. Primary care physicians’ and dermatologists’ skills at secondary prevention of skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(9):1030-1038.

19. Corbo MD, Wismer J. Agreement between dermatologists and primary care practitioners in the diagnosis of malignant melanoma: review of the literature. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16(5):306-310.

20. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, Fernández MI. Examining the factors associated with past and present dermoscopy use among family physicians. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7(4):63-70.

21. Dolianitis C, Kelly J, Wolfe R, Simpson P. Comparative performance of 4 dermoscopic algorithms by nonexperts for the diagnosis of melanocytic lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):1008-1014.

22. Westerhoff K, Mccarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143(5):1016-1020.

23. Argenziano G, Puig S, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy improves accuracy of primary care physicians to triage lesions suggestive of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(12):1877-1882.

24. Chappuis P, Duru G, Marchal O, Girier P, Dalle S, Thomas L. Dermoscopy, a useful tool for general practitioners in melanoma screening: a nationwide survey. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175(4):744-750.

25. Rosendahl C, Williams G, Eley D, et al. The impact of subspecialization and dermatoscopy use on accuracy of melanoma diagnosis among primary care doctors in Australia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):846-852.

26. Menzies SW, Ingvar C, Crotty KA, McCarthy WH. Frequency and morphologic characteristics of invasive melanomas lacking specific surface microscopic features. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(10):1178-1182.

27. Kittler H, Guitera P, Riedl E, et al. Identification of clinically featureless incipient melanoma using sequential dermoscopy imaging. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(9):1113-1119.

28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ambulatory care use and physician office visits. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm. Updated May 3, 2017. Accessed April 10, 2018.

29. Murzaku EC, Hayan S, Rao BK. Methods and rates of dermoscopy usage: a cross-sectional survey of US dermatologists stratified by years in practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):393-395.

30. Nehal KS, Oliveria SA, Marghoob AA, et al. Use of and beliefs about dermoscopy in the management of patients with pigmented lesions: a survey of dermatology residency programmes in the United States. Melanoma Res. 2002;12(6):601-605.

31. Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, Vuong CH, Stein JA, Polsky D. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(6):1000-1005.

32. Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(5):958-972

From 1982 to 2011, the melanoma incidence rate doubled in the US.1 In 2018, an estimated 87,290 cases of melanoma in situ and 91,270 cases of invasive melanoma will be diagnosed in the US, and 9,320 deaths will be attributable to melanoma.2 Early detection of melanoma is critically important to reduce melanoma-related mortality, with 5-year survival rates as high as 97% at stage 1A vs a 20% 5-year survival when there is distant metastasis.2,3 Melanoma is particularly relevant for medical providers working with veterans because melanoma disproportionately affects service members with an incidence rate ratio of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.40-1.86) compared with that of the general population.4

Biopsy is the definitive diagnostic tool for melanoma. Histologic analysis differentiates melanoma from seborrheic keratoses, pigmented nevi, dermatofibromas, and other pigmented lesions that can resemble melanoma on clinical examination. However, biopsy must be used judiciously as unnecessary biopsies contribute to health care costs and leave scars, which can have psychosocial implications. With benign nevi outnumbering melanoma about 2 million to 1, biopsy is indicated once a threshold of suspicion is obtained.5

Dermoscopic Tool

Dermoscopy is a microscopy-based tool to improve noninvasive diagnostic discrimination of skin lesions based on color and structure analysis. Coloration provides an indication of the composition of elements present in the skin with keratin appearing yellow, blood appearing red, and collagen appearing white. Coloration also suggests pigment depth as melanin appears black when located in the stratum corneum, brown when located deeper in the epidermis, and blue when located in the dermis.6 Finally, characteristic histopathologic alterations in the dermoepidermal junction, rete ridges, pigment-containing cells, and/or melanocyte granules that occur in melanoma are recognizable with dermoscopy.6

In 2001, Bafounta and colleagues performed the first meta-analysis on the efficacy of dermoscopy compared with that of clinical evaluation, finding that dermoscopy performed specifically by dermatology-trained clinicians improved the accuracy of identifying melanoma from an odds ratio of 16 (95% CI, 9-31) with naked eye examination to 76 (95% CI, 25-223) with dermoscopy.7

More recently, Terushkin and colleagues demonstrated that diagnosis specificity improves when a general dermatologist is trained in dermoscopic pattern recognition. Naked eye examination produced a benign to malignant ratio (BMR) of 18.4:1, indicating that about 18 of 19 biopsies considered suspicious for melanoma ultimately yielded benign melanocytic lesions. Although the BMR for the general dermatologist experienced an increase after dermoscopy training, the ratio eventually decreased to 7.9:1.8

Dermoscopic Analysis

Some of the common patterns recognized in melanoma are demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is a close-up of a patient’s upper back showing a solitary asymmetric melanocytic lesion containing multiple red, brown, black, and blue hues.

Pattern analysis, the dermoscopic interpretation method preferred by pigmented lesion specialists, requires simultaneously assessing numerous lesion patterns that vary depending on body site.10 Alternative dermoscopic algorithms that focus on the most common features of melanoma have been developed to aid practitioners with the interpretation of dermoscopy findings: the 7-point checklist, the Menzies method, the ABCD rule, and the CASH algorithm (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5).

Argenziano and colleagues developed the 7-point checklist in 1998. Two points are assigned to the lesion for each of the major criteria and 1 point for each minor criteria.

The Menzies method was developed by Menzies and colleagues in 1996. To be classified as melanoma, the pigmented lesion must show an absence of pattern symmetry and color uniformity while simultaneously exhibiting at least one of the following: blue-white veil, multiple brown dots, pseudopods, radial streaming, scarlike depigmentation, peripheral block dots/globules, 5 to 6 colors, multiple blue/gray dots, and a broadened network.12

The ABCD rule is a more technical dermoscopic evaluation algorithm developed in 1994 by Stolz and colleagues. This method yields a numeric value called the total dermoscopic score (TDS) based on Asymmetry, Border pigment pattern, Color variation, and 5 Different structural components.

Henning and colleagues developed the CASH algorithm in 2006 with the intention of assisting less experienced dermoscopy users with lesion evaluation.14 This algorithm tallies points for Color, Architectural disorder, Symmetry, and Homogeneity. One point is attributed to a lesion for each light brown, dark brown, black, red, white, and/or blue region present. Architectural disorder is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 indicating the absence of or minimal architectural disorder, 1 indicating moderate disorder, and 2 indicating marked disorder. Symmetry is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial symmetry, 1 point assigned to a lesion that exhibits monoaxial symmetry, and 2 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial asymmetry. Finally, 1 point is attributed to a lesion for evidence of each of the following: atypical network, dots/globules, streaks/pseudopods, blue-white veil, regression structures, blotches > 10% of the overall lesion size, and polymorphous blood vessels. The lesion in Figure 2 scores 16 points out of the maximum total CASH score of 17. Any lesion scoring 8 or more is suggestive of malignant melanoma.14

Finally, the TADA method was developed by Rogers and colleagues in 2016.15 This method uses sequential questions to evaluate lesions. First, “Does the lesion exhibit clear dermoscopic evidence of an angioma, dermatofibroma, or seborrheic keratosis?” If “yes,” then no additional dermoscopic evaluation is necessary, and it is recommended to monitor the lesion. If the answer to the first question is “no,” then ask, “Does the lesion exhibit architectural disorder?” The presence of architectural disorder is based on an overall impression of the lesion, which includes symmetry with regard to structures and colors. Any lesion deemed to exhibit architectural disorder should be biopsied. If the lesion has no architectural disorder, the third question is, “Does the lesion contain any starburst patterns, blue-black or gray coloration, shiny white structures, negative networks, ulcers or erosions, and/or vessels?” If “yes,” then the lesion should be biopsied. Since the lesion in Figure 2 exhibits marked architectural disorder in terms of symmetry and color, analysis of the lesion with the TADA method would yield a recommendation for biopsy.15

Dermoscopy in Practice

A. Bernard Ackerman, MD, a key figure in the modern era of dermatopathology, wrote an editorial for the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 1985 titled “No one should die of malignant melanoma.” The editorial highlighted that the visual changes associated with melanoma often manifest years prior to malignant invasion and advocated that all physicians should have competence in melanoma detection, specifically mentioning the importance of training primary care physicians (PCPs), dermatologists, and pathologists in this regard.16 This sentiment is equally as true now as it was in 1985.

Naked eye examination paired with an evaluation of patient risk factors for melanoma, including fair skin types, significant sun exposure history, history of sunburn, geographic location, and personal and family history of melanoma, are the foundation of melanoma detection efforts.17 Studies suggest that the triage skills of PCPs could be improved in regard to the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Primary care residents, for instance, did not accurately diagnose 40% of malignant melanoma cases.18,19 Additionally, a meta-analysis demonstrated that PCP accuracy when diagnosing malignant melanoma ranged between 49% and 80%, significantly less than the 85% to 89% exhibited by practicing dermatologists.19 Dermoscopy could be incorporated as an element of the skin examination to enhance lesion discrimination among PCPs, as it has proven use in dermatologic practice.

Dermoscopy is not readily used by PCPs. A survey study of 705 family practitioners in the US performed by Morris and colleagues demonstrated that only 8.3% of participants currently use a dermatoscope to evaluate pigmented lesions.20 The most common barriers to dermoscopy use cited by PCPs in the US include the cost of the dermatoscope, the time required to acquire proficiency, and the lack of financial reimbursement.16 True utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs is higher than this figure suggests due to the number of PCPs who access dermoscopic evaluations via teledermatology. All 21 Veterans Integrated Services Networks of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system, for instance, participate in teledermatology and jointly employ more than 1,150 trained telehealth clinical technicians who created a collective 107,000 teledermatology encounters with and without dermoscopy for evaluation by dermatologists in the most recent fiscal year(Martin Weinstock, written communication, October 2017). Nonetheless, it is necessary to determine the contribution that wider utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs would have on melanoma surveillance.

Studies show that dermoscopic algorithms improve the sensitivity while slightly decreasing the specificity of PCPs to detect melanoma compared with that of the naked eye examination. Dolianitis and colleagues demonstrated that a baseline sensitivity of 60.9% for melanoma detection improved to 85.4% with the 7-point checklist, 85.4% with Menzies method, and 77.5% with the ABCD rule, while the baseline specificity of 85.4% moderated to 73.0%, 77.7%, and 80.4%, respectively, among 61 medical practitioners after studying dermoscopy techniques from 2 CDs.21 Westerhoff and colleagues performed a randomized controlled trial with 74 PCPs to determine the effect of a minimal intervention on melanoma diagnostic accuracy. The intervention consisted of providing participants in the experimental group with an atlas of microscopic features common to melanoma to be read at the participants’ leisure, a 1-hour presentation on microscopy, and a 25-questionpractice quiz. Participants randomized to the intervention group improved their diagnostic accuracy from 57.8% to 75.9% with the use of dermoscopy. This group also experiencedimproved accuracy in its clinical diagnosis of melanoma from 54.6% to 62.7%.22

Argenziano and colleagues demonstrated similar results after PCPs attended a 4-hour workshop on dermoscopy. The 73 PCPs in this study evaluated 2,522 lesions randomized to naked eye examination or dermoscopy. The BMR, calculated from the data provided, improved from 12.6:1 to 10.5:1, respectively, when dermoscopy was incorporated into lesion analysis, while the sensitivity increased from 54.1% to 79.2% and the negative predictive value increased from 95.8% to 98.1%. It is important to note that the BMR and negative predictive value improved in tandem, indicating that PCPs were more discriminatory with their referrals for evaluation by dermatology while capturing a greater percentage of melanomas.23

These studies are not without limitations that preclude broad generalizations. For example, Dolianitis and colleagues and Westerhoff and colleagues provided participants with dermoscopic images of the lesions to be evaluated instead of requiring personal use of a dermatoscope, whereas the study by Argenziano and colleagues incorporated only 6 histopathologically proven malignant melanomas into each of the naked eye examination and the experimental dermoscopy groups.21-23 Yet these studies suggest that broader use of dermoscopy among PCPs could improve the accuracy of melanoma detection given clinically relevant training.

Several additional studies identify positive correlations associated with dermoscopy use among PCPs. A recent survey of 425 French general practitioners found that 8% of the study participants acknowledged owning a dermatoscope. Dermatoscope owners spent a statistically significant longer time analyzing each pigmented skin lesions, exhibited greater confidence in their analysis of pigmented lesions, and issued fewer overall referrals to dermatologists.24

Similarly, Rosendahl and colleagues evaluated the number needed to treat (NNT) (equivalent to the BMR) among 193 Australian PCPs and found that the NNT was inversely correlated to the frequency with which the physicians used dermoscopy. However, it was difficult to determine the definitive cause of the reduced NNT in this study because a similar effect was observed when NNT was evaluated based on general practitioner subspecialization.25 Again, despite limitations, these studies suggest that increased dermoscopy use among PCPs could reduce the morbidity of lifelong scarring as well as the short-term anxiety associated with a possible melanoma diagnosis.

Limitations

Even in the hands of a trained dermatologist, dermoscopy has limitations. Featureless melanoma is a term applied to melanoma lesions bereft of classical findings on both naked eye examination and dermoscopy. Menzies, a dermatologic pioneer in dermoscopy, acknowledged this limitation in 1996 while showing that 8% of melanomas evaded dermoscopic detection. He proceeded to discuss the importance of clinical history in melanoma detection because all of the featureless melanomas exhibited recent changes in size, shape, and/or color.26 More recently, sequential dermoscopy (mole mapping) imaging has been implemented to successfully identify these lesions.27 Thus, dermoscopy cannot replace dermatologists trained in the art of visual assessment with honed clinical diagnostic acumen. Rather, dermoscopy is a tool to enhance the assessment of clinically suspicious lesions and aid diagnostic discrimination of uncertain pigmented lesions.

Conclusion

Primary care physicians are on the frontline of medicine and often the first to have the opportunity to detect the presence of melanoma. Notably, 52.2% of the 884.7 million medical office visits performed annually in the US are with PCPs.28 Despite the benefits, dermoscopy is not uniformly used by dermatologists in the US. Of dermatologists practicing for more than 20 years, 76.2% use dermoscopy compared with 97.8% of dermatologists in practice for less than 5 years. This illustrates an increased use in tandem with dermatology residencies integrating dermoscopy training as a component of the curriculum, showing the importance of incorporating dermoscopy into medical school and residency training for PCPs..29-31 Guidelines regarding dermoscopy training and dermoscopic evaluation algorithms should be established, routinely taught in medical education, and actively incorporated into training curriculum for PCPs in order to improve patient care and realize the potential health care savings associated with the early diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. Dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations present a viable opportunity within the VHA to expedite access to care for veterans and simultaneously offer evaluative feedback on lesions to referring PCPs, as skilled, dermoscopy-trained dermatologists render the diagnoses. Given the devastating mortality rate of melanoma, continued multidisciplinary education on identifying melanoma is of the utmost importance for patient care. Widespread implementation of dermoscopy and dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations could save lives and slow the ever-increasing economic burden associated with melanoma treatment, costing $1.467 billion in 2016.32

From 1982 to 2011, the melanoma incidence rate doubled in the US.1 In 2018, an estimated 87,290 cases of melanoma in situ and 91,270 cases of invasive melanoma will be diagnosed in the US, and 9,320 deaths will be attributable to melanoma.2 Early detection of melanoma is critically important to reduce melanoma-related mortality, with 5-year survival rates as high as 97% at stage 1A vs a 20% 5-year survival when there is distant metastasis.2,3 Melanoma is particularly relevant for medical providers working with veterans because melanoma disproportionately affects service members with an incidence rate ratio of 1.62 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.40-1.86) compared with that of the general population.4

Biopsy is the definitive diagnostic tool for melanoma. Histologic analysis differentiates melanoma from seborrheic keratoses, pigmented nevi, dermatofibromas, and other pigmented lesions that can resemble melanoma on clinical examination. However, biopsy must be used judiciously as unnecessary biopsies contribute to health care costs and leave scars, which can have psychosocial implications. With benign nevi outnumbering melanoma about 2 million to 1, biopsy is indicated once a threshold of suspicion is obtained.5

Dermoscopic Tool

Dermoscopy is a microscopy-based tool to improve noninvasive diagnostic discrimination of skin lesions based on color and structure analysis. Coloration provides an indication of the composition of elements present in the skin with keratin appearing yellow, blood appearing red, and collagen appearing white. Coloration also suggests pigment depth as melanin appears black when located in the stratum corneum, brown when located deeper in the epidermis, and blue when located in the dermis.6 Finally, characteristic histopathologic alterations in the dermoepidermal junction, rete ridges, pigment-containing cells, and/or melanocyte granules that occur in melanoma are recognizable with dermoscopy.6

In 2001, Bafounta and colleagues performed the first meta-analysis on the efficacy of dermoscopy compared with that of clinical evaluation, finding that dermoscopy performed specifically by dermatology-trained clinicians improved the accuracy of identifying melanoma from an odds ratio of 16 (95% CI, 9-31) with naked eye examination to 76 (95% CI, 25-223) with dermoscopy.7

More recently, Terushkin and colleagues demonstrated that diagnosis specificity improves when a general dermatologist is trained in dermoscopic pattern recognition. Naked eye examination produced a benign to malignant ratio (BMR) of 18.4:1, indicating that about 18 of 19 biopsies considered suspicious for melanoma ultimately yielded benign melanocytic lesions. Although the BMR for the general dermatologist experienced an increase after dermoscopy training, the ratio eventually decreased to 7.9:1.8

Dermoscopic Analysis

Some of the common patterns recognized in melanoma are demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is a close-up of a patient’s upper back showing a solitary asymmetric melanocytic lesion containing multiple red, brown, black, and blue hues.

Pattern analysis, the dermoscopic interpretation method preferred by pigmented lesion specialists, requires simultaneously assessing numerous lesion patterns that vary depending on body site.10 Alternative dermoscopic algorithms that focus on the most common features of melanoma have been developed to aid practitioners with the interpretation of dermoscopy findings: the 7-point checklist, the Menzies method, the ABCD rule, and the CASH algorithm (Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5).

Argenziano and colleagues developed the 7-point checklist in 1998. Two points are assigned to the lesion for each of the major criteria and 1 point for each minor criteria.

The Menzies method was developed by Menzies and colleagues in 1996. To be classified as melanoma, the pigmented lesion must show an absence of pattern symmetry and color uniformity while simultaneously exhibiting at least one of the following: blue-white veil, multiple brown dots, pseudopods, radial streaming, scarlike depigmentation, peripheral block dots/globules, 5 to 6 colors, multiple blue/gray dots, and a broadened network.12

The ABCD rule is a more technical dermoscopic evaluation algorithm developed in 1994 by Stolz and colleagues. This method yields a numeric value called the total dermoscopic score (TDS) based on Asymmetry, Border pigment pattern, Color variation, and 5 Different structural components.

Henning and colleagues developed the CASH algorithm in 2006 with the intention of assisting less experienced dermoscopy users with lesion evaluation.14 This algorithm tallies points for Color, Architectural disorder, Symmetry, and Homogeneity. One point is attributed to a lesion for each light brown, dark brown, black, red, white, and/or blue region present. Architectural disorder is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 indicating the absence of or minimal architectural disorder, 1 indicating moderate disorder, and 2 indicating marked disorder. Symmetry is assigned a point value between 0 and 2, with 0 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial symmetry, 1 point assigned to a lesion that exhibits monoaxial symmetry, and 2 points assigned to a lesion that exhibits biaxial asymmetry. Finally, 1 point is attributed to a lesion for evidence of each of the following: atypical network, dots/globules, streaks/pseudopods, blue-white veil, regression structures, blotches > 10% of the overall lesion size, and polymorphous blood vessels. The lesion in Figure 2 scores 16 points out of the maximum total CASH score of 17. Any lesion scoring 8 or more is suggestive of malignant melanoma.14

Finally, the TADA method was developed by Rogers and colleagues in 2016.15 This method uses sequential questions to evaluate lesions. First, “Does the lesion exhibit clear dermoscopic evidence of an angioma, dermatofibroma, or seborrheic keratosis?” If “yes,” then no additional dermoscopic evaluation is necessary, and it is recommended to monitor the lesion. If the answer to the first question is “no,” then ask, “Does the lesion exhibit architectural disorder?” The presence of architectural disorder is based on an overall impression of the lesion, which includes symmetry with regard to structures and colors. Any lesion deemed to exhibit architectural disorder should be biopsied. If the lesion has no architectural disorder, the third question is, “Does the lesion contain any starburst patterns, blue-black or gray coloration, shiny white structures, negative networks, ulcers or erosions, and/or vessels?” If “yes,” then the lesion should be biopsied. Since the lesion in Figure 2 exhibits marked architectural disorder in terms of symmetry and color, analysis of the lesion with the TADA method would yield a recommendation for biopsy.15

Dermoscopy in Practice

A. Bernard Ackerman, MD, a key figure in the modern era of dermatopathology, wrote an editorial for the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in 1985 titled “No one should die of malignant melanoma.” The editorial highlighted that the visual changes associated with melanoma often manifest years prior to malignant invasion and advocated that all physicians should have competence in melanoma detection, specifically mentioning the importance of training primary care physicians (PCPs), dermatologists, and pathologists in this regard.16 This sentiment is equally as true now as it was in 1985.

Naked eye examination paired with an evaluation of patient risk factors for melanoma, including fair skin types, significant sun exposure history, history of sunburn, geographic location, and personal and family history of melanoma, are the foundation of melanoma detection efforts.17 Studies suggest that the triage skills of PCPs could be improved in regard to the evaluation of pigmented lesions. Primary care residents, for instance, did not accurately diagnose 40% of malignant melanoma cases.18,19 Additionally, a meta-analysis demonstrated that PCP accuracy when diagnosing malignant melanoma ranged between 49% and 80%, significantly less than the 85% to 89% exhibited by practicing dermatologists.19 Dermoscopy could be incorporated as an element of the skin examination to enhance lesion discrimination among PCPs, as it has proven use in dermatologic practice.

Dermoscopy is not readily used by PCPs. A survey study of 705 family practitioners in the US performed by Morris and colleagues demonstrated that only 8.3% of participants currently use a dermatoscope to evaluate pigmented lesions.20 The most common barriers to dermoscopy use cited by PCPs in the US include the cost of the dermatoscope, the time required to acquire proficiency, and the lack of financial reimbursement.16 True utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs is higher than this figure suggests due to the number of PCPs who access dermoscopic evaluations via teledermatology. All 21 Veterans Integrated Services Networks of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system, for instance, participate in teledermatology and jointly employ more than 1,150 trained telehealth clinical technicians who created a collective 107,000 teledermatology encounters with and without dermoscopy for evaluation by dermatologists in the most recent fiscal year(Martin Weinstock, written communication, October 2017). Nonetheless, it is necessary to determine the contribution that wider utilization of dermoscopy among PCPs would have on melanoma surveillance.

Studies show that dermoscopic algorithms improve the sensitivity while slightly decreasing the specificity of PCPs to detect melanoma compared with that of the naked eye examination. Dolianitis and colleagues demonstrated that a baseline sensitivity of 60.9% for melanoma detection improved to 85.4% with the 7-point checklist, 85.4% with Menzies method, and 77.5% with the ABCD rule, while the baseline specificity of 85.4% moderated to 73.0%, 77.7%, and 80.4%, respectively, among 61 medical practitioners after studying dermoscopy techniques from 2 CDs.21 Westerhoff and colleagues performed a randomized controlled trial with 74 PCPs to determine the effect of a minimal intervention on melanoma diagnostic accuracy. The intervention consisted of providing participants in the experimental group with an atlas of microscopic features common to melanoma to be read at the participants’ leisure, a 1-hour presentation on microscopy, and a 25-questionpractice quiz. Participants randomized to the intervention group improved their diagnostic accuracy from 57.8% to 75.9% with the use of dermoscopy. This group also experiencedimproved accuracy in its clinical diagnosis of melanoma from 54.6% to 62.7%.22

Argenziano and colleagues demonstrated similar results after PCPs attended a 4-hour workshop on dermoscopy. The 73 PCPs in this study evaluated 2,522 lesions randomized to naked eye examination or dermoscopy. The BMR, calculated from the data provided, improved from 12.6:1 to 10.5:1, respectively, when dermoscopy was incorporated into lesion analysis, while the sensitivity increased from 54.1% to 79.2% and the negative predictive value increased from 95.8% to 98.1%. It is important to note that the BMR and negative predictive value improved in tandem, indicating that PCPs were more discriminatory with their referrals for evaluation by dermatology while capturing a greater percentage of melanomas.23

These studies are not without limitations that preclude broad generalizations. For example, Dolianitis and colleagues and Westerhoff and colleagues provided participants with dermoscopic images of the lesions to be evaluated instead of requiring personal use of a dermatoscope, whereas the study by Argenziano and colleagues incorporated only 6 histopathologically proven malignant melanomas into each of the naked eye examination and the experimental dermoscopy groups.21-23 Yet these studies suggest that broader use of dermoscopy among PCPs could improve the accuracy of melanoma detection given clinically relevant training.

Several additional studies identify positive correlations associated with dermoscopy use among PCPs. A recent survey of 425 French general practitioners found that 8% of the study participants acknowledged owning a dermatoscope. Dermatoscope owners spent a statistically significant longer time analyzing each pigmented skin lesions, exhibited greater confidence in their analysis of pigmented lesions, and issued fewer overall referrals to dermatologists.24

Similarly, Rosendahl and colleagues evaluated the number needed to treat (NNT) (equivalent to the BMR) among 193 Australian PCPs and found that the NNT was inversely correlated to the frequency with which the physicians used dermoscopy. However, it was difficult to determine the definitive cause of the reduced NNT in this study because a similar effect was observed when NNT was evaluated based on general practitioner subspecialization.25 Again, despite limitations, these studies suggest that increased dermoscopy use among PCPs could reduce the morbidity of lifelong scarring as well as the short-term anxiety associated with a possible melanoma diagnosis.

Limitations

Even in the hands of a trained dermatologist, dermoscopy has limitations. Featureless melanoma is a term applied to melanoma lesions bereft of classical findings on both naked eye examination and dermoscopy. Menzies, a dermatologic pioneer in dermoscopy, acknowledged this limitation in 1996 while showing that 8% of melanomas evaded dermoscopic detection. He proceeded to discuss the importance of clinical history in melanoma detection because all of the featureless melanomas exhibited recent changes in size, shape, and/or color.26 More recently, sequential dermoscopy (mole mapping) imaging has been implemented to successfully identify these lesions.27 Thus, dermoscopy cannot replace dermatologists trained in the art of visual assessment with honed clinical diagnostic acumen. Rather, dermoscopy is a tool to enhance the assessment of clinically suspicious lesions and aid diagnostic discrimination of uncertain pigmented lesions.

Conclusion

Primary care physicians are on the frontline of medicine and often the first to have the opportunity to detect the presence of melanoma. Notably, 52.2% of the 884.7 million medical office visits performed annually in the US are with PCPs.28 Despite the benefits, dermoscopy is not uniformly used by dermatologists in the US. Of dermatologists practicing for more than 20 years, 76.2% use dermoscopy compared with 97.8% of dermatologists in practice for less than 5 years. This illustrates an increased use in tandem with dermatology residencies integrating dermoscopy training as a component of the curriculum, showing the importance of incorporating dermoscopy into medical school and residency training for PCPs..29-31 Guidelines regarding dermoscopy training and dermoscopic evaluation algorithms should be established, routinely taught in medical education, and actively incorporated into training curriculum for PCPs in order to improve patient care and realize the potential health care savings associated with the early diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. Dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations present a viable opportunity within the VHA to expedite access to care for veterans and simultaneously offer evaluative feedback on lesions to referring PCPs, as skilled, dermoscopy-trained dermatologists render the diagnoses. Given the devastating mortality rate of melanoma, continued multidisciplinary education on identifying melanoma is of the utmost importance for patient care. Widespread implementation of dermoscopy and dermoscopic-teledermatology consultations could save lives and slow the ever-increasing economic burden associated with melanoma treatment, costing $1.467 billion in 2016.32

1. Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, Watson M, Massetti GM, Richardson LC. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections-United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(21):591-596.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2018.

4. Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, Lewis DR, Phillips CJ. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179(3):247-253.

5. Thomas L, Puig S. Dermoscopy, digital dermoscopy and other diagnostic tools in the early detection of melanoma and follow-up of high-risk skin cancer patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97(218):14-21.

6. Marghoob AA, Usatine RP, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(7):441-450.

7. Bafounta ML, Beauchet A, Aegerter P, Saiag P. Is dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) useful for the diagnosis of melanoma? Results of a meta-analysis using techniques adapted to the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(10):1343-1350.

8. Terushkin V, Warycha M, Levy M, Kopf AW, Cohen DE, Polsky D. Analysis of the benign to malignant ratio of lesions biopsied by a general dermatologist before and after the adoption of dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):343-344.

9. Wolner ZJ, Yélamos O, Liopyris K, Rogers T, Marchetti MA, Marghoob AA. Enhancing skin cancer diagnosis with dermoscopy. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(4):417-437.

10. Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(5):981-984.