User login

Constructive Criticism

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

This is the first in a two-part series about how to provide constructive criticism to your hospitalist peers.

Part of improving your performance is learning from other hospitalists on a regular basis. You can do this through observation or discussion, and—when appropriate—by offering or receiving constructive criticism.

There are two types of physician-to-physician constructive criticism: When discussing perceived poor handling of a patient’s case, comments should take place within a formal peer review. Concerns about a physician’s non-clinical performance, such as communications problems or lack of availability, can be handled in a one-on-one conversation. Herein we’ll examine the peer review process; next month we’ll take a look at how and when to give constructive criticism to a peer informally.

Why Use Peer Review?

When a hospitalist notices a colleague’s clinical error or lack of judgment, it should be addressed in the program’s next peer review meeting, both for legal and procedural reasons.

“The key thing to understand is that ‘peer review’ offers certain protections for physicians and their colleagues,” explains Richard Rohr, MD, director, Hospitalist Service, Milford Hospital, Milford, Conn. “Ordinarily, if I discuss [another physician’s] case and render my opinion, then—in principle—if that patient were to file a lawsuit, they could subpoena me to testify about what I thought about their case. In the past, this had a chilling effect on peer review.”

Due to state laws passed years ago, peer review meetings now offer protection against subpoena. “Peer review meetings are protected,” says Dr. Rohr. “They can’t be used in court, and this makes it possible to have an organized peer review where you look at physicians’ work and provide an opinion about that work without fear of being drawn into a legal situation.”

The bottom line: “If you want to talk to another physician about their case, do so within [the peer review structure] so you’re legally protected,” says Dr. Rohr.

Focus on Improvement

When discussing a specific case or physician, remember that the reason for doing so is to improve quality of care. “Every practice should sit down, look at specific cases, and talk about possible areas of improvement,” says Dr. Rohr. “You need to take minutes of these meetings that are marked as confidential.”

The key to improvement is having an open discussion in each peer review meeting. “A good meeting is educational,” says Dr. Rohr. “The objective is to support each other and improve performance. A lot depends on the attitude that people bring to it. You have to not be afraid to say something; you must be willing to express opinions, or you’ll have a wasted meeting.”

Sometimes you may find that the problem goes beyond a single physician’s actions on a case. “If there is a problem with a case, find out whether it’s an aberration or if the problem needs to be addressed,” says Dr. Rohr. “Some things are not a physician’s fault, so much as [they are] signs that a medical system doesn’t work as effectively as it should or [that there is] a general lack of training. For example, an ER [emergency room] doctor misses a fracture. Was finding that fracture outside his competency? Does he need training reading X-rays, or can you manage to get radiologists in to check X-rays fast enough to become part of the process?”

Use a Set Structure

It’s up to the hospital medicine program director to set up a peer review process, which should be done within the structure established by the hospital. Peer review meetings “should be done on a regular basis,” advises Dr. Rohr. “How often depends on the volume of the program, but a typical group should meet monthly. You’ll probably look at three or four cases, which is a reasonable number to cover in one meeting. Look at unexpected mortalities or complications—you have a responsibility to the public to examine these.”

You might do best by bringing in an outside facilitator for the meetings. This creates an impartial atmosphere for discussions. “We bring in an external facilitator from a local teaching hospital,” says Dr. Rohr. “It’s good to have an educator lead the meeting; someone from academia will have a greater fund of knowledge and [a stronger] grasp of the medical literature, which helps bring the discussion to a more educational level. Everyone respects medical science.”

Note that the facilitator may need to be credentialed as a member of the medical staff in order for the proceedings to be protected from legal discovery.

“Peer review is difficult in smaller practices, because everyone knows everyone and they may be uncomfortable addressing problems,” explains Dr. Rohr. “Here, it’s especially helpful to have a leader from the outside who can render opinions and get everyone to chime in and render their own opinions.”

Remember that your peer review system is reportable. “As part of the hospital’s peer review structure, you’ll have to report findings from the meetings,” adds Dr. Rohr. “If someone is showing a pattern, these things have to be trended. Do they need training, or should they be dismissed?”

Giving Feedback through Peer Review

When you participate in a peer review discussion, don’t let your comments get too personal or subjective. “The most important thing is to keep it professional and make it educational to the greatest extent possible,” says Dr. Rohr. “Reference facts in the medical literature as often as possible. Point to something that’s been published to support your opinion. Base your comments on what’s known, and apply that to your analysis of the case.”

An evidence-based opinion doesn’t have to cite specific details; as long as you’re aware of major papers on the topic, you should have a grounded opinion.

Finally, as a physician participating in a peer review discussion, think before you speak. “Peer review works best when you have a basic respect for each other, as well as basic humility,” he says. TH

Jane Jerrard has written for The Hospitalist since 2005.

New Party in Power

Due to an overwhelming number of Democratic victories in last November’s midterm elections, the 110th Congress, which took office early this year, has new leaders and a new agenda that could bode well for healthcare legislation.

In this article, Laura Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs, explains what the changes in Congress could mean for the near future of healthcare and for the legislation and issues that SHM strongly supports. Based in Washington, D.C., Allendorf is responsible for providing government relations services for SHM. She advises the organization on key legislative and regulatory healthcare issues before Congress and the Bush administration, and she works with SHM leaders and staff on policy development and advocacy strategies.

Majority Rules

The midterm elections brought about a shift in power that goes deeper than numbers of bodies on each side of the aisle. “The Democrats are now the majority in both chambers. This is significant, because they’ve been the minority since 1994, says Allendorf. “As the majority, they control the agenda now—on healthcare and other issues—and they also head the key committees.”

What can we expect to see from the Democratic Congress? “We should expect to see a more expansionist agenda” in general, according to Allendorf. “We’re going to see more activism in the area of healthcare, but whether anything gets done remains to be seen. There’s only a slim majority in the Senate, and President Bush can wield his veto pen. For example, the Democrats would like to give [the Department of] Health and Human Services the power to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, specifically on Medicare Part D, but Bush won’t like that.”

Much depends on the issues at hand, as well as on how much bipartisan support exists for each specific bill.

Changing of the Guard

Anyone who glances at the newspaper knows that Democrat Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) is now the Speaker of the House. But Democratic leadership goes much deeper than that because the ruling party has also taken over leadership of Congressional committees. These committees shape the legislation introduced in the House and Senate.

As of press time, Congressional committee assignments had not been formally decided—at least not in the Senate—but many assignments were certain. “Typically, the highest-ranking Democrat [House or Senate] on a committee will become the new head, though Nancy Pelosi isn’t sticking to that,” explains Allendorf. “Pete Stark (D-Calif.) will likely chair the Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health, and Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) will head the House Ways and Means Committee. John Dingell (D-Mich.) will chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee.” (For more on committee chairs, visit http://media-newswire.com/release_1040623.html.)

For a complete list of committee members, visit SHM’s new Legislative Action Center at http://capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home/. See “New Advocacy Tool Available,” for more information on the Legislative Action Center, above.)

Starting Over on Key Issues

Many of the bills introduced in 2006—particularly spending bills—were not voted on by the end of the lame duck session last fall. That means that these bills must be reintroduced in the new year. Bills that recommend funding changes are frozen, so agencies continue to receive 2006 funding until the new Congress votes to change their budget.

“All bills have to be reintroduced in the 110th,” stresses Allendorf. “It will take some time—how much depends on the issue. The Democrats may want to hold hearings on legislation, or they may simply dust off legislation that was introduced last year.”

The Democrats are expected to move on many of the issues that SHM has been lobbying for. “They’ve said that they want to reform the healthcare system,” says Allendorf. “Top issues include providing coverage to the uninsured, reforming Medicare Part D, and resolving the physician payment issue.”

Allendorf believes that there will be a bipartisan effort to push through physician payment reform. “There are some 265 members of Congress who requested action on this issue this year [in 2006],” she points out. “There’s a genuine interest and desire to address physician payment reform and pay-for-performance as well. They may differ on how quickly they want to move on some of these.”

The news is not so good on the issue of gainsharing, where physicians are allowed to share the profits realized by a hospital’s cost reductions when linked to specific best practices. “Representative Nancy Johnson (R-Conn.) was a big proponent of this issue in the House, and she was not re-elected,” says Allendorf. “Stark is an opponent of gainsharing, so there may not be the same Congressional push behind it—at least in the House.”

However, the unexpected gainsharing demonstration projects approved in 2006 are underway, and Congress will hear reports on those in several years, once the projects have been analyzed.

Another issue that may not be addressed is liability. “Medical liability reform will be on the back burner,” warns Allendorf. “It’s generally not supported by the Democrats.”

In 2006, SHM supported increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—this was one of the major issues addressed by members during Legislative Advocacy Day during the Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. Whether the next budget includes more money for the agency remains to be seen. “The Democrats support increased funding for NIH (National Institutes of Health), AHRQ, and other healthcare agencies,” says Allendorf. “There’s certainly political will, but where is the money going to come from?”

New Congress, New Issues

What about new issues? “Democrats have signaled that healthcare access for the uninsured will be a priority,” says Allendorf. “I think that we’ll see new legislation with a renewed emphasis on access to care.”

SHM’s Public Policy Committee will be waiting for the first legislation to be introduced regarding coverage for uninsured Americans. “This is an issue that SHM is strongly in favor of,” explains Allendorf. “SHM will look at any bills that come out on this issue and then form a policy.”

Regardless of which healthcare issues come to the forefront first, SHM’s Public Policy Committee, staff, and members are likely to be more active than ever. “I see a very busy year legislatively for SHM,” says Allendorf. TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Due to an overwhelming number of Democratic victories in last November’s midterm elections, the 110th Congress, which took office early this year, has new leaders and a new agenda that could bode well for healthcare legislation.

In this article, Laura Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs, explains what the changes in Congress could mean for the near future of healthcare and for the legislation and issues that SHM strongly supports. Based in Washington, D.C., Allendorf is responsible for providing government relations services for SHM. She advises the organization on key legislative and regulatory healthcare issues before Congress and the Bush administration, and she works with SHM leaders and staff on policy development and advocacy strategies.

Majority Rules

The midterm elections brought about a shift in power that goes deeper than numbers of bodies on each side of the aisle. “The Democrats are now the majority in both chambers. This is significant, because they’ve been the minority since 1994, says Allendorf. “As the majority, they control the agenda now—on healthcare and other issues—and they also head the key committees.”

What can we expect to see from the Democratic Congress? “We should expect to see a more expansionist agenda” in general, according to Allendorf. “We’re going to see more activism in the area of healthcare, but whether anything gets done remains to be seen. There’s only a slim majority in the Senate, and President Bush can wield his veto pen. For example, the Democrats would like to give [the Department of] Health and Human Services the power to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, specifically on Medicare Part D, but Bush won’t like that.”

Much depends on the issues at hand, as well as on how much bipartisan support exists for each specific bill.

Changing of the Guard

Anyone who glances at the newspaper knows that Democrat Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) is now the Speaker of the House. But Democratic leadership goes much deeper than that because the ruling party has also taken over leadership of Congressional committees. These committees shape the legislation introduced in the House and Senate.

As of press time, Congressional committee assignments had not been formally decided—at least not in the Senate—but many assignments were certain. “Typically, the highest-ranking Democrat [House or Senate] on a committee will become the new head, though Nancy Pelosi isn’t sticking to that,” explains Allendorf. “Pete Stark (D-Calif.) will likely chair the Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health, and Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) will head the House Ways and Means Committee. John Dingell (D-Mich.) will chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee.” (For more on committee chairs, visit http://media-newswire.com/release_1040623.html.)

For a complete list of committee members, visit SHM’s new Legislative Action Center at http://capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home/. See “New Advocacy Tool Available,” for more information on the Legislative Action Center, above.)

Starting Over on Key Issues

Many of the bills introduced in 2006—particularly spending bills—were not voted on by the end of the lame duck session last fall. That means that these bills must be reintroduced in the new year. Bills that recommend funding changes are frozen, so agencies continue to receive 2006 funding until the new Congress votes to change their budget.

“All bills have to be reintroduced in the 110th,” stresses Allendorf. “It will take some time—how much depends on the issue. The Democrats may want to hold hearings on legislation, or they may simply dust off legislation that was introduced last year.”

The Democrats are expected to move on many of the issues that SHM has been lobbying for. “They’ve said that they want to reform the healthcare system,” says Allendorf. “Top issues include providing coverage to the uninsured, reforming Medicare Part D, and resolving the physician payment issue.”

Allendorf believes that there will be a bipartisan effort to push through physician payment reform. “There are some 265 members of Congress who requested action on this issue this year [in 2006],” she points out. “There’s a genuine interest and desire to address physician payment reform and pay-for-performance as well. They may differ on how quickly they want to move on some of these.”

The news is not so good on the issue of gainsharing, where physicians are allowed to share the profits realized by a hospital’s cost reductions when linked to specific best practices. “Representative Nancy Johnson (R-Conn.) was a big proponent of this issue in the House, and she was not re-elected,” says Allendorf. “Stark is an opponent of gainsharing, so there may not be the same Congressional push behind it—at least in the House.”

However, the unexpected gainsharing demonstration projects approved in 2006 are underway, and Congress will hear reports on those in several years, once the projects have been analyzed.

Another issue that may not be addressed is liability. “Medical liability reform will be on the back burner,” warns Allendorf. “It’s generally not supported by the Democrats.”

In 2006, SHM supported increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—this was one of the major issues addressed by members during Legislative Advocacy Day during the Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. Whether the next budget includes more money for the agency remains to be seen. “The Democrats support increased funding for NIH (National Institutes of Health), AHRQ, and other healthcare agencies,” says Allendorf. “There’s certainly political will, but where is the money going to come from?”

New Congress, New Issues

What about new issues? “Democrats have signaled that healthcare access for the uninsured will be a priority,” says Allendorf. “I think that we’ll see new legislation with a renewed emphasis on access to care.”

SHM’s Public Policy Committee will be waiting for the first legislation to be introduced regarding coverage for uninsured Americans. “This is an issue that SHM is strongly in favor of,” explains Allendorf. “SHM will look at any bills that come out on this issue and then form a policy.”

Regardless of which healthcare issues come to the forefront first, SHM’s Public Policy Committee, staff, and members are likely to be more active than ever. “I see a very busy year legislatively for SHM,” says Allendorf. TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Due to an overwhelming number of Democratic victories in last November’s midterm elections, the 110th Congress, which took office early this year, has new leaders and a new agenda that could bode well for healthcare legislation.

In this article, Laura Allendorf, SHM’s senior advisor for advocacy and government affairs, explains what the changes in Congress could mean for the near future of healthcare and for the legislation and issues that SHM strongly supports. Based in Washington, D.C., Allendorf is responsible for providing government relations services for SHM. She advises the organization on key legislative and regulatory healthcare issues before Congress and the Bush administration, and she works with SHM leaders and staff on policy development and advocacy strategies.

Majority Rules

The midterm elections brought about a shift in power that goes deeper than numbers of bodies on each side of the aisle. “The Democrats are now the majority in both chambers. This is significant, because they’ve been the minority since 1994, says Allendorf. “As the majority, they control the agenda now—on healthcare and other issues—and they also head the key committees.”

What can we expect to see from the Democratic Congress? “We should expect to see a more expansionist agenda” in general, according to Allendorf. “We’re going to see more activism in the area of healthcare, but whether anything gets done remains to be seen. There’s only a slim majority in the Senate, and President Bush can wield his veto pen. For example, the Democrats would like to give [the Department of] Health and Human Services the power to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies, specifically on Medicare Part D, but Bush won’t like that.”

Much depends on the issues at hand, as well as on how much bipartisan support exists for each specific bill.

Changing of the Guard

Anyone who glances at the newspaper knows that Democrat Nancy Pelosi (Calif.) is now the Speaker of the House. But Democratic leadership goes much deeper than that because the ruling party has also taken over leadership of Congressional committees. These committees shape the legislation introduced in the House and Senate.

As of press time, Congressional committee assignments had not been formally decided—at least not in the Senate—but many assignments were certain. “Typically, the highest-ranking Democrat [House or Senate] on a committee will become the new head, though Nancy Pelosi isn’t sticking to that,” explains Allendorf. “Pete Stark (D-Calif.) will likely chair the Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health, and Charles Rangel (D-N.Y.) will head the House Ways and Means Committee. John Dingell (D-Mich.) will chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee.” (For more on committee chairs, visit http://media-newswire.com/release_1040623.html.)

For a complete list of committee members, visit SHM’s new Legislative Action Center at http://capwiz.com/hospitalmedicine/home/. See “New Advocacy Tool Available,” for more information on the Legislative Action Center, above.)

Starting Over on Key Issues

Many of the bills introduced in 2006—particularly spending bills—were not voted on by the end of the lame duck session last fall. That means that these bills must be reintroduced in the new year. Bills that recommend funding changes are frozen, so agencies continue to receive 2006 funding until the new Congress votes to change their budget.

“All bills have to be reintroduced in the 110th,” stresses Allendorf. “It will take some time—how much depends on the issue. The Democrats may want to hold hearings on legislation, or they may simply dust off legislation that was introduced last year.”

The Democrats are expected to move on many of the issues that SHM has been lobbying for. “They’ve said that they want to reform the healthcare system,” says Allendorf. “Top issues include providing coverage to the uninsured, reforming Medicare Part D, and resolving the physician payment issue.”

Allendorf believes that there will be a bipartisan effort to push through physician payment reform. “There are some 265 members of Congress who requested action on this issue this year [in 2006],” she points out. “There’s a genuine interest and desire to address physician payment reform and pay-for-performance as well. They may differ on how quickly they want to move on some of these.”

The news is not so good on the issue of gainsharing, where physicians are allowed to share the profits realized by a hospital’s cost reductions when linked to specific best practices. “Representative Nancy Johnson (R-Conn.) was a big proponent of this issue in the House, and she was not re-elected,” says Allendorf. “Stark is an opponent of gainsharing, so there may not be the same Congressional push behind it—at least in the House.”

However, the unexpected gainsharing demonstration projects approved in 2006 are underway, and Congress will hear reports on those in several years, once the projects have been analyzed.

Another issue that may not be addressed is liability. “Medical liability reform will be on the back burner,” warns Allendorf. “It’s generally not supported by the Democrats.”

In 2006, SHM supported increased funding for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)—this was one of the major issues addressed by members during Legislative Advocacy Day during the Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C. Whether the next budget includes more money for the agency remains to be seen. “The Democrats support increased funding for NIH (National Institutes of Health), AHRQ, and other healthcare agencies,” says Allendorf. “There’s certainly political will, but where is the money going to come from?”

New Congress, New Issues

What about new issues? “Democrats have signaled that healthcare access for the uninsured will be a priority,” says Allendorf. “I think that we’ll see new legislation with a renewed emphasis on access to care.”

SHM’s Public Policy Committee will be waiting for the first legislation to be introduced regarding coverage for uninsured Americans. “This is an issue that SHM is strongly in favor of,” explains Allendorf. “SHM will look at any bills that come out on this issue and then form a policy.”

Regardless of which healthcare issues come to the forefront first, SHM’s Public Policy Committee, staff, and members are likely to be more active than ever. “I see a very busy year legislatively for SHM,” says Allendorf. TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Train the Teacher

If you work at a teaching institution, an important part of your career track may be teaching residents the work of hospitalists. “Within academia, there are two major tracks: research[er] and clinical educator,” says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, hospitalist and professor of internal medicine at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “We’re promoted based on our clinical work and on education evaluations; it’s helpful when we’re being reviewed if we’re seen as good teachers by our students.”

How are your teaching skills? How much thought and effort do you put into how you train your students? Do you take steps to improve your methods?

“Most of us have to work at being good teachers,” admits Dr. Saint. “We watch excellent teachers and learn as we go.” What follows is the advice of one excellent teacher.

Teachers: Champions for Hospital Medicine

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, is an SHM board member and associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, where he also serves as associate chairman of medicine, director of the Tulane Internal Medicine Residency Program, and associate director of student programs, internal medicine. “From an [SHM] board perspective, it’s been my agenda to better situate hospitalists as teachers,” he says.

One reason he’s committed to boosting the number of hospitalist-teachers is that Dr. Wiese believes the specialty is a perfect match for imparting knowledge. “Hospitalists are better instructors primarily because of their greater accessibility for supervision,” he says. “Because of the number of things they do and the consistent repetition with which they do them, they also have a better familiarity with what students need to know and how to do it.”

Another reason that hospitalists are excellent choices to train residents: “Hospitalists work at improving hospital systems and focus on quality of care,” says Dr. Wiese. “What better group of people to teach the systems of care and practice-based learning competencies?”

Coaching Versus Teaching

The basis of Dr. Wiese’s theory of teaching is that you should think and act as a coach—not a teacher. “A teacher is responsible for disseminating knowledge to his pupils; a coach is responsible for the performance of his pupils,” explains Dr. Wiese. “With a coach, the success of the job is contingent on the performance of the player—in this case, the student or resident.”

The coaching theory goes deeper than that distinction. “Components of coaching include [the following]: You have to teach the necessary skill, but you have to motivate the person to want to do it right, create a vision of how they’re going to do it, anticipate and prepare them for potential obstacles that might stand in the way of their performance, and provide feedback and evaluation when they do it,” says Dr. Wiese. “A football coach wouldn’t just tell you how to throw a ball. He would teach you the skill and then watch you do it, while providing feedback on your performance. He would tell you what the opposing team might do to oppose your performance of that skill and prepare you to overcome that opposition. And then he would instill a motivation such that you wanted to perform the skill well.”

Dr. Saint, who is familiar with Dr. Wiese’s theory, says, “I like the metaphor of coaching because a coach tries to make you better at what you’re learning. A coach may use techniques that make you uncomfortable at the time, but if you look back after a couple of years, you’ll be thankful that he pushed you.”

Another aspect of coaching that fits neatly into today’s clinical learning is the team aspect. “Medicine is no longer an individual event,” explains Dr. Wiese. “It’s a team activity, where the best patient care is provided by a team of healthcare professionals from doctors to nurses to physical therapists and others. Teaching the mentality of playing as part of a team will help residents perform better in this environment as they advance in their careers.”

Teaching in a “Vacum”

“I use the mnemonic VACUM [to describe coaching],” says Dr. Wiese. VACUM stands for:

- Visualization: To pique interest in a topic or procedure, start by asking students to visualize themselves using the skill. Repeatedly ask them how they think they will put the skill to use.

“Get the person to picture herself with a patient,” urges Dr. Wiese. This step both hooks learners at the beginning of a session and helps teach them the skill.

- Anticipation: If you’re an experienced teacher and know your students well, you know where they will struggle in the learning process. “Think about the common pitfalls,” says Dr. Wiese. “Alert the student to where she will get confused or make mistakes and spend time preparing the student for how she can avoid the pitfall. For example, if you’re teaching them about putting in a central line, tell them, ‘You [might] not think about the patient’s bleeding risk prior to procedure. Make sure you know his INR [international normalized ratio] and platelet count prior to starting the procedure.’ ”

- Content: “This is where most teachers go awry,” warns Dr. Wiese. “Medical educators try to teach too much, and students try to learn too much. Not every detail in a topic needs to be discussed. It’s far better to sacrifice details to preserve time to ensure that students have mastered the fundamental concepts of a disease or skill. They can pick up the details later—focus on what they need to know.”

How do you know what to focus on? “The guidelines of what students must learn during their internal medicine clerkship are voluminous,” says Dr. Wiese. “Find those that you think have utility in your practice or utility to the students. The best strategy is to stick to the fundamentals. With this strategy, they will walk away with the critical components that will empower them to pick up the details during subsequent teaching sessions.”

- Utility: “This goes with content,” says Dr. Wiese. “Teach them skills that they can utilize. Remember, utility varies from student to student. A student heading into a future career in orthopedics will find greater utility in learning about pre-operative care and management of atrial fibrillation than she will with a discourse on lupus.”

- Motivation: Motivation includes three subcategories. “Students or residents have to know that the coach is on their side,” says Dr. Wiese. One way to do this is to learn their names—and use them frequently. You should also use physical contact to show your support.

“Give a pat on the shoulder, or shake someone’s hand,” he advises. “If you’re in a classroom, move around the room. Show that you’re accessible.” Finally, find people’s hooks—that is, what interests them.

So how do you know you’ve become a good teacher? “The ultimate goal of coaching is successful student performance—not awards or approbation. The measure of your success is defined by seeing your students months or even years later, doing right by a patient because of what you taught them to do,” says Dr. Wiese. “Focus on that goal, and everything else will fall into place.” TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Career Development.”

If you work at a teaching institution, an important part of your career track may be teaching residents the work of hospitalists. “Within academia, there are two major tracks: research[er] and clinical educator,” says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, hospitalist and professor of internal medicine at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “We’re promoted based on our clinical work and on education evaluations; it’s helpful when we’re being reviewed if we’re seen as good teachers by our students.”

How are your teaching skills? How much thought and effort do you put into how you train your students? Do you take steps to improve your methods?

“Most of us have to work at being good teachers,” admits Dr. Saint. “We watch excellent teachers and learn as we go.” What follows is the advice of one excellent teacher.

Teachers: Champions for Hospital Medicine

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, is an SHM board member and associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, where he also serves as associate chairman of medicine, director of the Tulane Internal Medicine Residency Program, and associate director of student programs, internal medicine. “From an [SHM] board perspective, it’s been my agenda to better situate hospitalists as teachers,” he says.

One reason he’s committed to boosting the number of hospitalist-teachers is that Dr. Wiese believes the specialty is a perfect match for imparting knowledge. “Hospitalists are better instructors primarily because of their greater accessibility for supervision,” he says. “Because of the number of things they do and the consistent repetition with which they do them, they also have a better familiarity with what students need to know and how to do it.”

Another reason that hospitalists are excellent choices to train residents: “Hospitalists work at improving hospital systems and focus on quality of care,” says Dr. Wiese. “What better group of people to teach the systems of care and practice-based learning competencies?”

Coaching Versus Teaching

The basis of Dr. Wiese’s theory of teaching is that you should think and act as a coach—not a teacher. “A teacher is responsible for disseminating knowledge to his pupils; a coach is responsible for the performance of his pupils,” explains Dr. Wiese. “With a coach, the success of the job is contingent on the performance of the player—in this case, the student or resident.”

The coaching theory goes deeper than that distinction. “Components of coaching include [the following]: You have to teach the necessary skill, but you have to motivate the person to want to do it right, create a vision of how they’re going to do it, anticipate and prepare them for potential obstacles that might stand in the way of their performance, and provide feedback and evaluation when they do it,” says Dr. Wiese. “A football coach wouldn’t just tell you how to throw a ball. He would teach you the skill and then watch you do it, while providing feedback on your performance. He would tell you what the opposing team might do to oppose your performance of that skill and prepare you to overcome that opposition. And then he would instill a motivation such that you wanted to perform the skill well.”

Dr. Saint, who is familiar with Dr. Wiese’s theory, says, “I like the metaphor of coaching because a coach tries to make you better at what you’re learning. A coach may use techniques that make you uncomfortable at the time, but if you look back after a couple of years, you’ll be thankful that he pushed you.”

Another aspect of coaching that fits neatly into today’s clinical learning is the team aspect. “Medicine is no longer an individual event,” explains Dr. Wiese. “It’s a team activity, where the best patient care is provided by a team of healthcare professionals from doctors to nurses to physical therapists and others. Teaching the mentality of playing as part of a team will help residents perform better in this environment as they advance in their careers.”

Teaching in a “Vacum”

“I use the mnemonic VACUM [to describe coaching],” says Dr. Wiese. VACUM stands for:

- Visualization: To pique interest in a topic or procedure, start by asking students to visualize themselves using the skill. Repeatedly ask them how they think they will put the skill to use.

“Get the person to picture herself with a patient,” urges Dr. Wiese. This step both hooks learners at the beginning of a session and helps teach them the skill.

- Anticipation: If you’re an experienced teacher and know your students well, you know where they will struggle in the learning process. “Think about the common pitfalls,” says Dr. Wiese. “Alert the student to where she will get confused or make mistakes and spend time preparing the student for how she can avoid the pitfall. For example, if you’re teaching them about putting in a central line, tell them, ‘You [might] not think about the patient’s bleeding risk prior to procedure. Make sure you know his INR [international normalized ratio] and platelet count prior to starting the procedure.’ ”

- Content: “This is where most teachers go awry,” warns Dr. Wiese. “Medical educators try to teach too much, and students try to learn too much. Not every detail in a topic needs to be discussed. It’s far better to sacrifice details to preserve time to ensure that students have mastered the fundamental concepts of a disease or skill. They can pick up the details later—focus on what they need to know.”

How do you know what to focus on? “The guidelines of what students must learn during their internal medicine clerkship are voluminous,” says Dr. Wiese. “Find those that you think have utility in your practice or utility to the students. The best strategy is to stick to the fundamentals. With this strategy, they will walk away with the critical components that will empower them to pick up the details during subsequent teaching sessions.”

- Utility: “This goes with content,” says Dr. Wiese. “Teach them skills that they can utilize. Remember, utility varies from student to student. A student heading into a future career in orthopedics will find greater utility in learning about pre-operative care and management of atrial fibrillation than she will with a discourse on lupus.”

- Motivation: Motivation includes three subcategories. “Students or residents have to know that the coach is on their side,” says Dr. Wiese. One way to do this is to learn their names—and use them frequently. You should also use physical contact to show your support.

“Give a pat on the shoulder, or shake someone’s hand,” he advises. “If you’re in a classroom, move around the room. Show that you’re accessible.” Finally, find people’s hooks—that is, what interests them.

So how do you know you’ve become a good teacher? “The ultimate goal of coaching is successful student performance—not awards or approbation. The measure of your success is defined by seeing your students months or even years later, doing right by a patient because of what you taught them to do,” says Dr. Wiese. “Focus on that goal, and everything else will fall into place.” TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Career Development.”

If you work at a teaching institution, an important part of your career track may be teaching residents the work of hospitalists. “Within academia, there are two major tracks: research[er] and clinical educator,” says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, hospitalist and professor of internal medicine at the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor. “We’re promoted based on our clinical work and on education evaluations; it’s helpful when we’re being reviewed if we’re seen as good teachers by our students.”

How are your teaching skills? How much thought and effort do you put into how you train your students? Do you take steps to improve your methods?

“Most of us have to work at being good teachers,” admits Dr. Saint. “We watch excellent teachers and learn as we go.” What follows is the advice of one excellent teacher.

Teachers: Champions for Hospital Medicine

Jeffrey Wiese, MD, FACP, is an SHM board member and associate professor of medicine at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, where he also serves as associate chairman of medicine, director of the Tulane Internal Medicine Residency Program, and associate director of student programs, internal medicine. “From an [SHM] board perspective, it’s been my agenda to better situate hospitalists as teachers,” he says.

One reason he’s committed to boosting the number of hospitalist-teachers is that Dr. Wiese believes the specialty is a perfect match for imparting knowledge. “Hospitalists are better instructors primarily because of their greater accessibility for supervision,” he says. “Because of the number of things they do and the consistent repetition with which they do them, they also have a better familiarity with what students need to know and how to do it.”

Another reason that hospitalists are excellent choices to train residents: “Hospitalists work at improving hospital systems and focus on quality of care,” says Dr. Wiese. “What better group of people to teach the systems of care and practice-based learning competencies?”

Coaching Versus Teaching

The basis of Dr. Wiese’s theory of teaching is that you should think and act as a coach—not a teacher. “A teacher is responsible for disseminating knowledge to his pupils; a coach is responsible for the performance of his pupils,” explains Dr. Wiese. “With a coach, the success of the job is contingent on the performance of the player—in this case, the student or resident.”

The coaching theory goes deeper than that distinction. “Components of coaching include [the following]: You have to teach the necessary skill, but you have to motivate the person to want to do it right, create a vision of how they’re going to do it, anticipate and prepare them for potential obstacles that might stand in the way of their performance, and provide feedback and evaluation when they do it,” says Dr. Wiese. “A football coach wouldn’t just tell you how to throw a ball. He would teach you the skill and then watch you do it, while providing feedback on your performance. He would tell you what the opposing team might do to oppose your performance of that skill and prepare you to overcome that opposition. And then he would instill a motivation such that you wanted to perform the skill well.”

Dr. Saint, who is familiar with Dr. Wiese’s theory, says, “I like the metaphor of coaching because a coach tries to make you better at what you’re learning. A coach may use techniques that make you uncomfortable at the time, but if you look back after a couple of years, you’ll be thankful that he pushed you.”

Another aspect of coaching that fits neatly into today’s clinical learning is the team aspect. “Medicine is no longer an individual event,” explains Dr. Wiese. “It’s a team activity, where the best patient care is provided by a team of healthcare professionals from doctors to nurses to physical therapists and others. Teaching the mentality of playing as part of a team will help residents perform better in this environment as they advance in their careers.”

Teaching in a “Vacum”

“I use the mnemonic VACUM [to describe coaching],” says Dr. Wiese. VACUM stands for:

- Visualization: To pique interest in a topic or procedure, start by asking students to visualize themselves using the skill. Repeatedly ask them how they think they will put the skill to use.

“Get the person to picture herself with a patient,” urges Dr. Wiese. This step both hooks learners at the beginning of a session and helps teach them the skill.

- Anticipation: If you’re an experienced teacher and know your students well, you know where they will struggle in the learning process. “Think about the common pitfalls,” says Dr. Wiese. “Alert the student to where she will get confused or make mistakes and spend time preparing the student for how she can avoid the pitfall. For example, if you’re teaching them about putting in a central line, tell them, ‘You [might] not think about the patient’s bleeding risk prior to procedure. Make sure you know his INR [international normalized ratio] and platelet count prior to starting the procedure.’ ”

- Content: “This is where most teachers go awry,” warns Dr. Wiese. “Medical educators try to teach too much, and students try to learn too much. Not every detail in a topic needs to be discussed. It’s far better to sacrifice details to preserve time to ensure that students have mastered the fundamental concepts of a disease or skill. They can pick up the details later—focus on what they need to know.”

How do you know what to focus on? “The guidelines of what students must learn during their internal medicine clerkship are voluminous,” says Dr. Wiese. “Find those that you think have utility in your practice or utility to the students. The best strategy is to stick to the fundamentals. With this strategy, they will walk away with the critical components that will empower them to pick up the details during subsequent teaching sessions.”

- Utility: “This goes with content,” says Dr. Wiese. “Teach them skills that they can utilize. Remember, utility varies from student to student. A student heading into a future career in orthopedics will find greater utility in learning about pre-operative care and management of atrial fibrillation than she will with a discourse on lupus.”

- Motivation: Motivation includes three subcategories. “Students or residents have to know that the coach is on their side,” says Dr. Wiese. One way to do this is to learn their names—and use them frequently. You should also use physical contact to show your support.

“Give a pat on the shoulder, or shake someone’s hand,” he advises. “If you’re in a classroom, move around the room. Show that you’re accessible.” Finally, find people’s hooks—that is, what interests them.

So how do you know you’ve become a good teacher? “The ultimate goal of coaching is successful student performance—not awards or approbation. The measure of your success is defined by seeing your students months or even years later, doing right by a patient because of what you taught them to do,” says Dr. Wiese. “Focus on that goal, and everything else will fall into place.” TH

Jane Jerrard regularly writes “Career Development.”

A Look inside Healthcare Transparency

One of the many trends in healthcare today is a move toward making specific quality and pricing information available to the public.

“When you’re buying a car, you can easily compare quality, features, and prices to make an educated guess,” points out Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director, Cogent Healthcare, Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. “In contrast, healthcare is completely opaque. People choose a doctor or a hospital—sometimes for a surgery that’s life threatening—by word of mouth or [based on] proximity. How do you make it possible to choose based on quality of care and on price?”

Known as healthcare transparency, this trend is driven by multiple sources. “The [CMS] Hospital Compare initiative was a first step in this, as were the Leapfrog initiative and the IHI [Institute for Health Improvement] Collaborative,” says Dr. Siegal. “In fact, the government is a little late to the game, but they’re quickly closing the gap.”

Mandate from the President

On August 22, 2006, President George W. Bush signed an executive order requiring key federal agencies to collect information about the quality and cost of the healthcare they provide and to share that data with each another—and with beneficiaries. Agencies included in the order are the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

The executive order directs these four agencies to work with the private sector and other government agencies to develop programs to measure quality of care. They were required by Jan. 1, 2007, to identify practices that promote high quality care and to compile information on the prices they pay for common services available to their members. Ultimately, the executive order calls for combining that data in a comprehensive source on providers’ quality and prices; this information will then be available to consumers.

President Bush has said that his order sends a message to healthcare providers that “in order to do business with the federal government, you’ve got to show us your prices.” The new requirements for transparency will affect healthcare providers across the country because treating about one-quarter of Americans covered by health insurance entails “doing business with the federal government.” That one-quarter includes Medicare beneficiaries, health insurance beneficiaries at the DoD and the VA, and federal employees. (The order clearly states that the directive does not apply to state-administered or -funded programs.)

House Legislation: Make Prices Public

Comprehensive pricing transparency may also be required on a state level. On Sept. 13, 2006, Representative Michael Burgess (R-Texas) introduced the Health Care Price Transparency Act of 2006 in the House. This American Hospital Association (AHA)-supported legislation would require states to publicly report hospital charges for specific inpatient and outpatient services and would require insurers to give patients, on request, an estimate of their expected out-of-pocket expenses.

—Eric Siegal, MD

The bill would also require the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study what type of healthcare price information consumers would find useful and how that information could be made available in a timely, understandable form.

Thirty-two states already require hospitals to report pricing information, and six more are voluntarily doing so, but this legislation would likely change the information that hospitals and other providers are gathering and providing.

At press time, the legislation had been referred to the House Subcommittee on Health.

How Transparency Will Roll Out

While the House legislation is in limbo, the executive order will have an immediate effect on healthcare, starting this year. The quality measures to be included in reporting will be developed from private and government sources, including local providers, employers, and health plans and insurers.

After the data are gathered and the information technology (IT) infrastructure is set up, consumers will be able to access specific information on pricing and quality of services performed by doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers. This information may be available through a variety of sources, including insurance companies, employers, and Medicare-sponsored Web sites.

One of the keys to success will be in the collaboration among the agencies involved. “There’s a keen understanding among the major players that if everyone does their own thing, we’ll have chaos,” says Dr. Siegal. “There has to be a significant degree of harmonization [among] physician measures, hospital measures, inpatient measures, and outpatient measures.”

Where Hospitalists Fit in

Will healthcare transparency affect hospitalists? “It’s already impacting hospitalists,” says Dr. Siegal. “Not on pricing, but on quality reporting. The good news is that hospitalists may be the single best-prepared group of physicians [for transparency] because we’re already doing it. The question will be, as it becomes more pervasive, will it be done in a way that is thoughtful, measured, and practical?”

Hospitals are likely to look to their hospitalists to ensure that their quality measurements are competitive. Dr. Siegal explains, “Hospitals looking to improve quality will be most effective in getting results from the physicians whose financial incentives are aligned with theirs.”

However, additional—or more public—quality indicators will not necessarily create a huge source of income for hospital medicine. “The low-hanging fruit won’t be the patients that hospitalists see; it will be elective surgical cases,” predicts Dr. Siegal. “Those are cleanly defined procedures, with bundled payments and predictable outcomes, where a hospital can understand what happens and what’s included. Then they can say, ‘Why do we charge 20% more for a total elective hip [surgery] than the hospital down the road?’ ”

As transparency is rolled out in U.S. hospitals and healthcare systems, hospitalists will look good. “Hospitalists already live in a quality reporting world, more so than other doctors,” says Dr. Siegal. TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

One of the many trends in healthcare today is a move toward making specific quality and pricing information available to the public.

“When you’re buying a car, you can easily compare quality, features, and prices to make an educated guess,” points out Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director, Cogent Healthcare, Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. “In contrast, healthcare is completely opaque. People choose a doctor or a hospital—sometimes for a surgery that’s life threatening—by word of mouth or [based on] proximity. How do you make it possible to choose based on quality of care and on price?”

Known as healthcare transparency, this trend is driven by multiple sources. “The [CMS] Hospital Compare initiative was a first step in this, as were the Leapfrog initiative and the IHI [Institute for Health Improvement] Collaborative,” says Dr. Siegal. “In fact, the government is a little late to the game, but they’re quickly closing the gap.”

Mandate from the President

On August 22, 2006, President George W. Bush signed an executive order requiring key federal agencies to collect information about the quality and cost of the healthcare they provide and to share that data with each another—and with beneficiaries. Agencies included in the order are the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

The executive order directs these four agencies to work with the private sector and other government agencies to develop programs to measure quality of care. They were required by Jan. 1, 2007, to identify practices that promote high quality care and to compile information on the prices they pay for common services available to their members. Ultimately, the executive order calls for combining that data in a comprehensive source on providers’ quality and prices; this information will then be available to consumers.

President Bush has said that his order sends a message to healthcare providers that “in order to do business with the federal government, you’ve got to show us your prices.” The new requirements for transparency will affect healthcare providers across the country because treating about one-quarter of Americans covered by health insurance entails “doing business with the federal government.” That one-quarter includes Medicare beneficiaries, health insurance beneficiaries at the DoD and the VA, and federal employees. (The order clearly states that the directive does not apply to state-administered or -funded programs.)

House Legislation: Make Prices Public

Comprehensive pricing transparency may also be required on a state level. On Sept. 13, 2006, Representative Michael Burgess (R-Texas) introduced the Health Care Price Transparency Act of 2006 in the House. This American Hospital Association (AHA)-supported legislation would require states to publicly report hospital charges for specific inpatient and outpatient services and would require insurers to give patients, on request, an estimate of their expected out-of-pocket expenses.

—Eric Siegal, MD

The bill would also require the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study what type of healthcare price information consumers would find useful and how that information could be made available in a timely, understandable form.

Thirty-two states already require hospitals to report pricing information, and six more are voluntarily doing so, but this legislation would likely change the information that hospitals and other providers are gathering and providing.

At press time, the legislation had been referred to the House Subcommittee on Health.

How Transparency Will Roll Out

While the House legislation is in limbo, the executive order will have an immediate effect on healthcare, starting this year. The quality measures to be included in reporting will be developed from private and government sources, including local providers, employers, and health plans and insurers.

After the data are gathered and the information technology (IT) infrastructure is set up, consumers will be able to access specific information on pricing and quality of services performed by doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers. This information may be available through a variety of sources, including insurance companies, employers, and Medicare-sponsored Web sites.

One of the keys to success will be in the collaboration among the agencies involved. “There’s a keen understanding among the major players that if everyone does their own thing, we’ll have chaos,” says Dr. Siegal. “There has to be a significant degree of harmonization [among] physician measures, hospital measures, inpatient measures, and outpatient measures.”

Where Hospitalists Fit in

Will healthcare transparency affect hospitalists? “It’s already impacting hospitalists,” says Dr. Siegal. “Not on pricing, but on quality reporting. The good news is that hospitalists may be the single best-prepared group of physicians [for transparency] because we’re already doing it. The question will be, as it becomes more pervasive, will it be done in a way that is thoughtful, measured, and practical?”

Hospitals are likely to look to their hospitalists to ensure that their quality measurements are competitive. Dr. Siegal explains, “Hospitals looking to improve quality will be most effective in getting results from the physicians whose financial incentives are aligned with theirs.”

However, additional—or more public—quality indicators will not necessarily create a huge source of income for hospital medicine. “The low-hanging fruit won’t be the patients that hospitalists see; it will be elective surgical cases,” predicts Dr. Siegal. “Those are cleanly defined procedures, with bundled payments and predictable outcomes, where a hospital can understand what happens and what’s included. Then they can say, ‘Why do we charge 20% more for a total elective hip [surgery] than the hospital down the road?’ ”

As transparency is rolled out in U.S. hospitals and healthcare systems, hospitalists will look good. “Hospitalists already live in a quality reporting world, more so than other doctors,” says Dr. Siegal. TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

One of the many trends in healthcare today is a move toward making specific quality and pricing information available to the public.

“When you’re buying a car, you can easily compare quality, features, and prices to make an educated guess,” points out Eric Siegal, MD, regional medical director, Cogent Healthcare, Madison, Wis., and chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. “In contrast, healthcare is completely opaque. People choose a doctor or a hospital—sometimes for a surgery that’s life threatening—by word of mouth or [based on] proximity. How do you make it possible to choose based on quality of care and on price?”

Known as healthcare transparency, this trend is driven by multiple sources. “The [CMS] Hospital Compare initiative was a first step in this, as were the Leapfrog initiative and the IHI [Institute for Health Improvement] Collaborative,” says Dr. Siegal. “In fact, the government is a little late to the game, but they’re quickly closing the gap.”

Mandate from the President

On August 22, 2006, President George W. Bush signed an executive order requiring key federal agencies to collect information about the quality and cost of the healthcare they provide and to share that data with each another—and with beneficiaries. Agencies included in the order are the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Defense (DoD), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

The executive order directs these four agencies to work with the private sector and other government agencies to develop programs to measure quality of care. They were required by Jan. 1, 2007, to identify practices that promote high quality care and to compile information on the prices they pay for common services available to their members. Ultimately, the executive order calls for combining that data in a comprehensive source on providers’ quality and prices; this information will then be available to consumers.

President Bush has said that his order sends a message to healthcare providers that “in order to do business with the federal government, you’ve got to show us your prices.” The new requirements for transparency will affect healthcare providers across the country because treating about one-quarter of Americans covered by health insurance entails “doing business with the federal government.” That one-quarter includes Medicare beneficiaries, health insurance beneficiaries at the DoD and the VA, and federal employees. (The order clearly states that the directive does not apply to state-administered or -funded programs.)

House Legislation: Make Prices Public

Comprehensive pricing transparency may also be required on a state level. On Sept. 13, 2006, Representative Michael Burgess (R-Texas) introduced the Health Care Price Transparency Act of 2006 in the House. This American Hospital Association (AHA)-supported legislation would require states to publicly report hospital charges for specific inpatient and outpatient services and would require insurers to give patients, on request, an estimate of their expected out-of-pocket expenses.

—Eric Siegal, MD

The bill would also require the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to study what type of healthcare price information consumers would find useful and how that information could be made available in a timely, understandable form.

Thirty-two states already require hospitals to report pricing information, and six more are voluntarily doing so, but this legislation would likely change the information that hospitals and other providers are gathering and providing.

At press time, the legislation had been referred to the House Subcommittee on Health.

How Transparency Will Roll Out

While the House legislation is in limbo, the executive order will have an immediate effect on healthcare, starting this year. The quality measures to be included in reporting will be developed from private and government sources, including local providers, employers, and health plans and insurers.

After the data are gathered and the information technology (IT) infrastructure is set up, consumers will be able to access specific information on pricing and quality of services performed by doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers. This information may be available through a variety of sources, including insurance companies, employers, and Medicare-sponsored Web sites.

One of the keys to success will be in the collaboration among the agencies involved. “There’s a keen understanding among the major players that if everyone does their own thing, we’ll have chaos,” says Dr. Siegal. “There has to be a significant degree of harmonization [among] physician measures, hospital measures, inpatient measures, and outpatient measures.”

Where Hospitalists Fit in

Will healthcare transparency affect hospitalists? “It’s already impacting hospitalists,” says Dr. Siegal. “Not on pricing, but on quality reporting. The good news is that hospitalists may be the single best-prepared group of physicians [for transparency] because we’re already doing it. The question will be, as it becomes more pervasive, will it be done in a way that is thoughtful, measured, and practical?”

Hospitals are likely to look to their hospitalists to ensure that their quality measurements are competitive. Dr. Siegal explains, “Hospitals looking to improve quality will be most effective in getting results from the physicians whose financial incentives are aligned with theirs.”

However, additional—or more public—quality indicators will not necessarily create a huge source of income for hospital medicine. “The low-hanging fruit won’t be the patients that hospitalists see; it will be elective surgical cases,” predicts Dr. Siegal. “Those are cleanly defined procedures, with bundled payments and predictable outcomes, where a hospital can understand what happens and what’s included. Then they can say, ‘Why do we charge 20% more for a total elective hip [surgery] than the hospital down the road?’ ”

As transparency is rolled out in U.S. hospitals and healthcare systems, hospitalists will look good. “Hospitalists already live in a quality reporting world, more so than other doctors,” says Dr. Siegal. TH

Jane Jerrard writes “Public Policy” for The Hospitalist.

Pay Dirt

It’ s easy to find figures on what hospitalists earn these days, but if your own income doesn’t match up, does that mean you’re underpaid? Not necessarily.

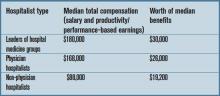

The SHM Survey