User login

Reducing Benzodiazepine Prescribing in Older Veterans: A Direct-to-Consumer Educational Brochure

This quality improvement project used an educational brochure to help older veterans reduce their benzodiazepine use.

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are among the most commonly prescribed medications. A recent study found that in 2008, more than 5% of Americans used a BZD, and the percentage was almost 9% among Americans aged ≥ 65 years.1,2 Among veterans, BZD use is even higher, in part because of the high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One study found that more than 30% of veterans with PTSD received at least 1 BZD prescription.3 The risks associated with BZD treatment for PTSD are compounded by concurrent use of other sedatives and opioids prescribed for co-occurring chronic pain and insomnia.3

Older adults metabolize long-acting BZDs more slowly and generally have an increased sensitivity to the adverse effects (AEs) of all BZDs.4 In older adults, BZD use has been associated with cognitive decline, dementia, falls and consequent fractures, and adverse respiratory outcomes.5-12 The risk of most but not all of these AEs was increased with higher BZD dose or long-term BZD use, which this quality improvement project (QIP) defines as having at least a 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year.

Long-term BZD use increases with age. One study found that, among patients receiving a BZD, the rate of long-term BZD use was more than double in older adults (31.4%) than it was in adults aged between 18 and 35 years (14.7%).2 For these reasons, the 2012 Beers criteria of the American Geriatrics Society recommend avoiding all types of BZDs in the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium in patients aged > 65 years.13 Despite this recommendation, the prevalence of BZD use in older adults remains high.14

Some innovative approaches have been developed to address the inappropriate use, including overuse and misuse, of BZDs in older adults.15 In one approach, direct-to-consumer (DTC) information is used to empower patients to collaborate with their physician to manage their health. Results from several studies suggest that providing older patients with information on BZD risks and benefits increases patient–physician interaction and thereby decreases inappropriate BZD use and improves health outcomes.4,16,17 One study found that perceptions of BZD risks increased 1 week after exposure to a DTC educational brochure (EB), with intention to discuss BZD discontinuation with their physician higher for patients who received the EB than it was for those who did not (83.1% vs 44.3%; P < .0001).16 The EMPOWER (Eliminating Medications Through Patient Ownership of End Results) cluster randomized controlled trial assessed the effectiveness of a DTC EB focused on BZD risks in older adults.17 In that seminal study, patients who received a DTC EB were more likely than were comparison patients to discontinue BZD within 6 months (27% vs 5%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, 14%-32%).

The Veterans Integrated Systems Network (VISN) 22 Academic Detailing Program is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20 With BZD use among older veterans remaining high, the VISN 22 program initiated a clinical QIP modeled on the EMPOWER trial. Veterans in VISN 22 received the DTC EB, which included information on BZD risks and encouraged them to discuss their BZD treatment with their health care provider. VISN 22 was the first VISN in the VHA to implement the EMPOWER protocol.

As this was a QIP, all eligible veterans in VISN 22 were mailed the DTC EB, thus making it difficult to estimate the impact of the EB on BZD discontinuation in this VISN. Therefore, DTC EB efficacy was estimated by comparing BZD discontinuation between VISN 22 and VISN 21, an adjacent VISN that did not mail the DTC EB.

Methods

Two QIPs were undertaken to determine the impact of DTC EB on BZD use in older veterans in the VHA.

Quality Improvement Project 1

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis was performed. The VISN 22 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in southern California and southern Nevada, serves about 500,000 veterans, a substantial proportion of whom are aged ≥ 65 years. Among these older veterans are active long-term BZD users, who were defined as having ≥ 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year. Each active long-term user with a BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date (the date the user was to meet with the prescribing physician) was mailed an EB 2 to 8 weeks in advance of the visit. Excluded from analysis were veterans with a schizophrenia, spinal cord injury, or seizure disorder diagnosis recorded in both their inpatient and outpatient medical records; veterans seen by Palliative Care within the past year; and veterans who died before analysis was completed.

Education Brochure. The EB for VISN 22 (Figure 1, see

Patients. The sample consisted of all veterans identified as meeting the inclusion criteria and being enrolled in VISN 22. The EB was mailed once to veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016. Change in BZD use was analyzed only after 9 to 24 months had passed since the index appointment with the prescribing physician. This period included 12 weeks for BZD taper and then 6 months after taper.

Analysis. For each veteran, monthly mean lorazepam equivalent (LE) was calculated using as many as 12 fills before the index date. Average daily dose of LE was calculated by dividing the sum of LE from all included prescriptions by total number of days between the first fill and the index date. The BZD prescription fills were evaluated after the index date. Veterans who received at least 1 prescription after the index date but then had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics for 3 consecutive months during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having tapered and then discontinued BZD. Veterans who had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having discontinued BZD without tapering. For veterans who had BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period, mean LE was calculated by dividing the total LE for BZD prescriptions after the index date by number of days from the first fill after the index date to the date of analysis.

Quality Improvement Project 2

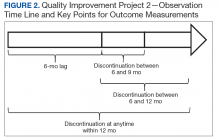

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis using PSM was performed on a subgroup of the QIP-1 sample to evaluate the impact of EB on BZD prescribing in the VA during 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. Veterans in the analysis were active long-term BZD users, had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date, were aged ≥ 65 years, and had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescriber within 2 to 8 weeks (Figure 2).

Patients. VISN 22 implemented QIP-2, a real-world application of a modified EMPOWER program, by identifying eligible veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to August 2015. All veterans who were identified and sent an EB during this period were included in the case group. The index date was defined as the first of the month the EB was mailed. Veterans with a pending appointment were chosen because the lead time would allow them to receive the EB and prepare to discuss it with the physician during the visit.

A comparator group was drawn from the adjacent VISN 21 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in Hawaii, northern California, and northern Nevada. During the observation period, VISN 21 did not mail any EBs specifically addressing BZD risks. Veterans in the comparator group had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescribing physician within 4 weeks, were aged ≥ 65 years on the index date (first of the month before the next appointment, coinciding with the date EBs were sent to VISN 22 veterans), were active long-term BZD users, and had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date. All patients were followed for up to 12 months after the index date, with BZD discontinuation recorded 9 and 12 months after the index date.

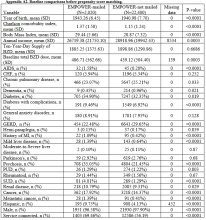

Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score (PS) was estimated with logistic regression analysis with treatment as the dependent variable and baseline characteristics as the independent variables.21,22 One-to-one matching on the PS was performed using the nearest neighbor approach without replacements. Independent variables related to outcome but unrelated to EB exposure were selected for PS development.22 These variables included year of birth; male sex; Hispanic ethnicity; annual income; service connection status; region; body mass index; Charlson Comorbidity Index category; total baseline BZD dose; and diagnosis of AIDS, nonmetastatic cancer, metastatic cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), dementia, diabetes mellitus (DM), DM with complications, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), general anxiety disorder (GAD), hemiparaplegia, liver disease (mild), liver disease (moderate to severe), myocardial infarction (MI), Parkinson disease, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), psychosis, renal disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or substance use disorder (SUD).

The EMPOWER cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated the effectiveness of EB exposure in a Canadian population of elderly patients who were long-term BZD users.17 Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for clinical trials because they can establish causal inference.23-25 Given ethical and practical concerns, however, RCTs cannot be applied to all clinical scenarios. Although EMPOWER is reported to be an effective tool in reducing BZD use in older adults, its application in a real-world, large, integrated health care system remains untested. Observational studies are often conducted as an alternative to RCTs but are subject to selection bias because of their lack of randomization.26 Therefore, robust research methods are needed to generate unbiased estimates of the impact of an intervention on an outcome. Propensity score matching simulates an RCT by balancing the covariates across treatment groups.21,22,27 Observed patient characteristics are used to estimate PS, the probability that treatment will be received. Logistic or probit regression is used to balance the potential confounding covariates between the treatment groups.Once PSs are known, mean treatment effect can be estimated without the mean model.28 In other words, PSM methods can be used to generate an unbiased estimate of the treatment.

Propensity Score Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using Student t test (continuous variables) and χ2 test (discrete variables). Results are presented as means and standard deviations (continuous variables) and frequency and percentage (discrete variables).

The main outcome was BZD discontinuation 9 and 12 months after the index date. A postindex lag of 6 months was used to capture any tapering (Figure 2). Discontinuation, defined as 3 consecutive months of no BZD prescription on hand, was measured for 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. An estimate was made of the difference in the proportions of BZD discontinuers who received the EB and BZD discontinuers who did not receive the EB, where mean treatment (risk difference) was presented as the absolute risk difference with a 95% CI. Standard errors and 95% CIs for the risk differences were generated with biased-corrected CIs from 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Sensitivity Analyses

Naïve multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between EB exposure and BZD discontinuation while controlling for potential confounders. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Confounders identified were the same covariates used to generate the PSs.

Several analyses were performed to test the sensitivity of the methods applied using PSM by changing caliber size while maintaining the nearest neighbor approach without replacement. Linear regression analysis was performed with robust standard errors to estimate the risk difference of BZD discontinuation between EB-exposed and EB-unexposed veterans.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/SE Version 13 (College Station, TX).

Results

Quality Improvement Project 1

On a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016, the EB was mailed once to 3,896 VISN 22 veterans 2 to 8 weeks before a clinic appointment with their BZD prescribing physician.

Quality Improvement Project 2

Of all the VISN 22 and VISN 21 veterans, 24,420 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these 24,420 veterans, 2,020 (8.3%) were in VISN 22 and received the EB between December 2014 and August 2015 (QIP-1), and 22,400 (91.7%) were in VISN 21 and did not receive the EB.

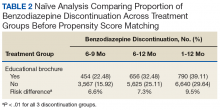

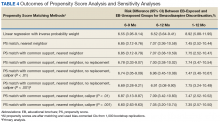

Naïve Results Before PS Matching. In the naïve analyses, a larger proportion of EB-exposed vs unexposed veterans discontinued BZD; in addition, reductions were 6.6%, 7.4%, and 9.5% larger for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (P < .0001 for all comparisons; Table 2).

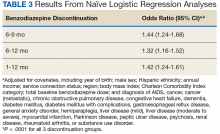

After controlling for potential confounders, the naïve logistic regression analyses found EB exposure was significantly associated with 44%, 32%, and 42% increases in the odds of BZD discontinuation for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (Table 3).

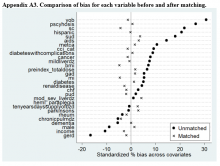

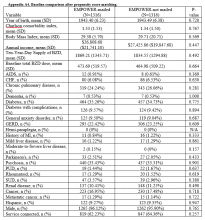

Propensity Score Matching. Before matching, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics of veterans who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with few exceptions (eAppendices 2 and 3, ).

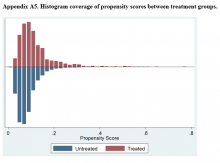

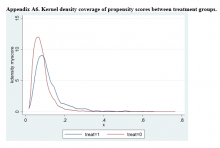

Propensity Score Matching Results. Inspection of PSs revealed good coverage across treatment groups on a histogram plot and a kernel density plot (eAppendices 5 and 6).

Discussion

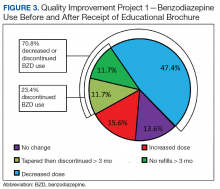

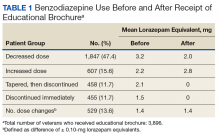

This QIP was the first to evaluate the impact of an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB in a large, integrated health care system in the U.S. It was also the first to demonstrate potential benefits of a DTC EB designed for older veterans who are long-term BZD users. In this QIP, which mailed the EB to 3,896 veterans, 1,847 (47.4%) decreased their BZD dose, 458 (11.7%) tapered and then discontinued BZD, and 455 (11.7%) immediately discontinued BZD. The total percentage of veterans who discontinued BZD (23.4%; 913/3,896) was similar to the 27% reported in the EMPOWER trial.17 However, the risk difference between the 1,316 EB-exposed VISN 22 veterans (QIP-1) and the 1,316 EB-unexposed VISN 21 veterans in this QIP was significantly lower than the 23% risk difference in EMPOWER (though it still demonstrated a significantly larger reduction for EB-exposed veterans).17

Given this inclusion of all qualifying veterans from the catchment area studied in this QIP, and given the ethical and practical concerns, an RCT was not possible. Therefore, PSM methods were used to balance the covariates across treatment groups and thereby simulate an RCT.21,22,27 With use of the PSM approach, findings from the descriptive analysis were confirmed and potential selection bias reduced.

Study Limitations

The less robust risk difference found in this QIP has several possible explanations. The authors’ use of a DTC EB coincided with a national VA effort to reduce older veterans’ use of BZDs and other inappropriate medications. For instance, during the study period, academic detailing was being implemented to reduce use of BZDs, particularly in combination with opioids, across VHA facilities and clinics. (Academic detailing is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20) However, QIP-2 results and PS analysis of a subgroup of the original sample suggest that EB-exposed veterans were significantly more likely than were their unexposed counterparts were to discontinue BZD. To an extent, this analysis controlled for these other efforts to reduce BZD use in VHA clinics and can be considered a study strength.

Another limitation is the study design, which lacked a control group and did not consider the possibility that some facility or clinic physicians might influence others. Although the region variable was controlled for in PSM, the authors did not capture facility characteristics, including frequency of prescribing BZD and use of a protocol for enforcing the Beers criteria. Such confounders might have influenced outcomes. Unlike the EMPOWER trial,17 this QIP did not assess or exclude cognitively impaired veterans. It is reasonable to assume that these veterans might not understand some EB messages and consequently might fail to engage their physicians. Failure to initiate discussion with a physician would attenuate the impact of the EB.

Study Strengths

A strength of this QIP was its use of a DTC EB in a large, regional sample of older veterans in a real-world clinical setting. In addition, the study group (EB-exposed veterans) and the comparator group (EB-unexposed veterans) were from similar geographic areas (primarily California and Nevada).

Conclusion

Results of this study suggest that a DTC EB, designed to reduce BZD use among older veterans, was effective in helping patients lower their BZD dose and discontinue BZD. The likelihood of discontinuing BZD 9 and 12 months after the index date was significantly higher for veterans who received an EB modeled on the EMPOWER educational brochure than for a comparator group of veterans who did not receive the EB and were receiving care during the same observation period. In the future, it would be beneficial to use a design that controls for physician exposure to academic detailing focused on BZD reduction and that accounts for the cluster effects of facility practice. Despite these limitations, this QIP is the first real-world empirical example of using an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB to decrease BZD use among older veterans. Furthermore, these results suggest that a DTC EB can be used to target other high-risk prescription drugs, such as opioids, particularly if alternative treatment options can be provided.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hauser thanks Cathy, Anika, Katia, and Max Hauser, and Alba and Kevin Quinlan, for their support. In memory of Jirina Hauser, who died on Mother’s Day, May 14, 2017, at the age of 100.

1. Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):7-20.

2. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

3. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Friedman MJ. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

4. Roberts KJ. Patient empowerment in the United States: a critical commentary. Health Expect. 1999;2(2):82-92.

5. Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(3):285-293.

6. van der Hooft CS, Schoofs MW, Ziere G, et al. Inappropriate benzodiazepine use in older adults and the risk of fracture. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(2):276-282.

7. Zint K, Haefeli WE, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Impact of drug interactions, dosage, and duration of therapy on the risk of hip fracture associated with benzodiazepine use in older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(12):1248-1255.

8. Finkle WD, Der JS, Greenland S, et al. Risk of fractures requiring hospitalization after an initial prescription for zolpidem, alprazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1883-1890.

9. de Gage SB, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231

10. Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639-658.

11. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

12. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Regular benzodiazepine and z-substance use and risk of dementia: an analysis of German claims data. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(2):801-808.

13. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

14. National Institutes of Health. Despite risks, benzodiazepine use highest in older people. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/despite-risks-benzodiaze pine-use-highest-older-people. Published December 17, 2014. Accessed July 31, 2018.

15. Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):89.

16. Martin P, Tamblyn R, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. A drug education tool developed for older adults changes knowledge, beliefs and risk perceptions about inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions in the elderly. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):81-87.

17. Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-898.

18. Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263(4):549-556.

19. Fischer MA, Avorn J. Academic detailing can play a key role in assessing and implementing comparative effectiveness research findings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2206-2212.

20. Wells DL, Popish S, Kay C, Torrise V, Christopher ML. VA Academic Detailing Service: implementation and lessons learned. Fed Pract. 2016;33(5):38-42.

21. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424.

22. Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1149-1156.

23. Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Ed Psych. 1974;66(5):688-701.

24. Greenland S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(4):722-729.

25. Cartwright N. What are randomized controlled trials good for? Philos Stud. 2010;147(1):59.

26. Kleinbaum DG, Morgenstern H, Kupper LL. Selection bias in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113(4):452-463.

27. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55.

28. Pirracchio R, Carone M, Rigon MR, Caruana E, Mebazaa A, Chevret S. Propensity score estimators for the average treatment effect and the average treatment effect on the treated may yield very different estimates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(5):1938-1954.

This quality improvement project used an educational brochure to help older veterans reduce their benzodiazepine use.

This quality improvement project used an educational brochure to help older veterans reduce their benzodiazepine use.

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are among the most commonly prescribed medications. A recent study found that in 2008, more than 5% of Americans used a BZD, and the percentage was almost 9% among Americans aged ≥ 65 years.1,2 Among veterans, BZD use is even higher, in part because of the high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One study found that more than 30% of veterans with PTSD received at least 1 BZD prescription.3 The risks associated with BZD treatment for PTSD are compounded by concurrent use of other sedatives and opioids prescribed for co-occurring chronic pain and insomnia.3

Older adults metabolize long-acting BZDs more slowly and generally have an increased sensitivity to the adverse effects (AEs) of all BZDs.4 In older adults, BZD use has been associated with cognitive decline, dementia, falls and consequent fractures, and adverse respiratory outcomes.5-12 The risk of most but not all of these AEs was increased with higher BZD dose or long-term BZD use, which this quality improvement project (QIP) defines as having at least a 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year.

Long-term BZD use increases with age. One study found that, among patients receiving a BZD, the rate of long-term BZD use was more than double in older adults (31.4%) than it was in adults aged between 18 and 35 years (14.7%).2 For these reasons, the 2012 Beers criteria of the American Geriatrics Society recommend avoiding all types of BZDs in the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium in patients aged > 65 years.13 Despite this recommendation, the prevalence of BZD use in older adults remains high.14

Some innovative approaches have been developed to address the inappropriate use, including overuse and misuse, of BZDs in older adults.15 In one approach, direct-to-consumer (DTC) information is used to empower patients to collaborate with their physician to manage their health. Results from several studies suggest that providing older patients with information on BZD risks and benefits increases patient–physician interaction and thereby decreases inappropriate BZD use and improves health outcomes.4,16,17 One study found that perceptions of BZD risks increased 1 week after exposure to a DTC educational brochure (EB), with intention to discuss BZD discontinuation with their physician higher for patients who received the EB than it was for those who did not (83.1% vs 44.3%; P < .0001).16 The EMPOWER (Eliminating Medications Through Patient Ownership of End Results) cluster randomized controlled trial assessed the effectiveness of a DTC EB focused on BZD risks in older adults.17 In that seminal study, patients who received a DTC EB were more likely than were comparison patients to discontinue BZD within 6 months (27% vs 5%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, 14%-32%).

The Veterans Integrated Systems Network (VISN) 22 Academic Detailing Program is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20 With BZD use among older veterans remaining high, the VISN 22 program initiated a clinical QIP modeled on the EMPOWER trial. Veterans in VISN 22 received the DTC EB, which included information on BZD risks and encouraged them to discuss their BZD treatment with their health care provider. VISN 22 was the first VISN in the VHA to implement the EMPOWER protocol.

As this was a QIP, all eligible veterans in VISN 22 were mailed the DTC EB, thus making it difficult to estimate the impact of the EB on BZD discontinuation in this VISN. Therefore, DTC EB efficacy was estimated by comparing BZD discontinuation between VISN 22 and VISN 21, an adjacent VISN that did not mail the DTC EB.

Methods

Two QIPs were undertaken to determine the impact of DTC EB on BZD use in older veterans in the VHA.

Quality Improvement Project 1

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis was performed. The VISN 22 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in southern California and southern Nevada, serves about 500,000 veterans, a substantial proportion of whom are aged ≥ 65 years. Among these older veterans are active long-term BZD users, who were defined as having ≥ 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year. Each active long-term user with a BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date (the date the user was to meet with the prescribing physician) was mailed an EB 2 to 8 weeks in advance of the visit. Excluded from analysis were veterans with a schizophrenia, spinal cord injury, or seizure disorder diagnosis recorded in both their inpatient and outpatient medical records; veterans seen by Palliative Care within the past year; and veterans who died before analysis was completed.

Education Brochure. The EB for VISN 22 (Figure 1, see

Patients. The sample consisted of all veterans identified as meeting the inclusion criteria and being enrolled in VISN 22. The EB was mailed once to veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016. Change in BZD use was analyzed only after 9 to 24 months had passed since the index appointment with the prescribing physician. This period included 12 weeks for BZD taper and then 6 months after taper.

Analysis. For each veteran, monthly mean lorazepam equivalent (LE) was calculated using as many as 12 fills before the index date. Average daily dose of LE was calculated by dividing the sum of LE from all included prescriptions by total number of days between the first fill and the index date. The BZD prescription fills were evaluated after the index date. Veterans who received at least 1 prescription after the index date but then had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics for 3 consecutive months during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having tapered and then discontinued BZD. Veterans who had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having discontinued BZD without tapering. For veterans who had BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period, mean LE was calculated by dividing the total LE for BZD prescriptions after the index date by number of days from the first fill after the index date to the date of analysis.

Quality Improvement Project 2

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis using PSM was performed on a subgroup of the QIP-1 sample to evaluate the impact of EB on BZD prescribing in the VA during 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. Veterans in the analysis were active long-term BZD users, had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date, were aged ≥ 65 years, and had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescriber within 2 to 8 weeks (Figure 2).

Patients. VISN 22 implemented QIP-2, a real-world application of a modified EMPOWER program, by identifying eligible veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to August 2015. All veterans who were identified and sent an EB during this period were included in the case group. The index date was defined as the first of the month the EB was mailed. Veterans with a pending appointment were chosen because the lead time would allow them to receive the EB and prepare to discuss it with the physician during the visit.

A comparator group was drawn from the adjacent VISN 21 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in Hawaii, northern California, and northern Nevada. During the observation period, VISN 21 did not mail any EBs specifically addressing BZD risks. Veterans in the comparator group had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescribing physician within 4 weeks, were aged ≥ 65 years on the index date (first of the month before the next appointment, coinciding with the date EBs were sent to VISN 22 veterans), were active long-term BZD users, and had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date. All patients were followed for up to 12 months after the index date, with BZD discontinuation recorded 9 and 12 months after the index date.

Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score (PS) was estimated with logistic regression analysis with treatment as the dependent variable and baseline characteristics as the independent variables.21,22 One-to-one matching on the PS was performed using the nearest neighbor approach without replacements. Independent variables related to outcome but unrelated to EB exposure were selected for PS development.22 These variables included year of birth; male sex; Hispanic ethnicity; annual income; service connection status; region; body mass index; Charlson Comorbidity Index category; total baseline BZD dose; and diagnosis of AIDS, nonmetastatic cancer, metastatic cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), dementia, diabetes mellitus (DM), DM with complications, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), general anxiety disorder (GAD), hemiparaplegia, liver disease (mild), liver disease (moderate to severe), myocardial infarction (MI), Parkinson disease, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), psychosis, renal disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or substance use disorder (SUD).

The EMPOWER cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated the effectiveness of EB exposure in a Canadian population of elderly patients who were long-term BZD users.17 Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for clinical trials because they can establish causal inference.23-25 Given ethical and practical concerns, however, RCTs cannot be applied to all clinical scenarios. Although EMPOWER is reported to be an effective tool in reducing BZD use in older adults, its application in a real-world, large, integrated health care system remains untested. Observational studies are often conducted as an alternative to RCTs but are subject to selection bias because of their lack of randomization.26 Therefore, robust research methods are needed to generate unbiased estimates of the impact of an intervention on an outcome. Propensity score matching simulates an RCT by balancing the covariates across treatment groups.21,22,27 Observed patient characteristics are used to estimate PS, the probability that treatment will be received. Logistic or probit regression is used to balance the potential confounding covariates between the treatment groups.Once PSs are known, mean treatment effect can be estimated without the mean model.28 In other words, PSM methods can be used to generate an unbiased estimate of the treatment.

Propensity Score Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using Student t test (continuous variables) and χ2 test (discrete variables). Results are presented as means and standard deviations (continuous variables) and frequency and percentage (discrete variables).

The main outcome was BZD discontinuation 9 and 12 months after the index date. A postindex lag of 6 months was used to capture any tapering (Figure 2). Discontinuation, defined as 3 consecutive months of no BZD prescription on hand, was measured for 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. An estimate was made of the difference in the proportions of BZD discontinuers who received the EB and BZD discontinuers who did not receive the EB, where mean treatment (risk difference) was presented as the absolute risk difference with a 95% CI. Standard errors and 95% CIs for the risk differences were generated with biased-corrected CIs from 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Sensitivity Analyses

Naïve multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between EB exposure and BZD discontinuation while controlling for potential confounders. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Confounders identified were the same covariates used to generate the PSs.

Several analyses were performed to test the sensitivity of the methods applied using PSM by changing caliber size while maintaining the nearest neighbor approach without replacement. Linear regression analysis was performed with robust standard errors to estimate the risk difference of BZD discontinuation between EB-exposed and EB-unexposed veterans.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/SE Version 13 (College Station, TX).

Results

Quality Improvement Project 1

On a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016, the EB was mailed once to 3,896 VISN 22 veterans 2 to 8 weeks before a clinic appointment with their BZD prescribing physician.

Quality Improvement Project 2

Of all the VISN 22 and VISN 21 veterans, 24,420 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these 24,420 veterans, 2,020 (8.3%) were in VISN 22 and received the EB between December 2014 and August 2015 (QIP-1), and 22,400 (91.7%) were in VISN 21 and did not receive the EB.

Naïve Results Before PS Matching. In the naïve analyses, a larger proportion of EB-exposed vs unexposed veterans discontinued BZD; in addition, reductions were 6.6%, 7.4%, and 9.5% larger for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (P < .0001 for all comparisons; Table 2).

After controlling for potential confounders, the naïve logistic regression analyses found EB exposure was significantly associated with 44%, 32%, and 42% increases in the odds of BZD discontinuation for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (Table 3).

Propensity Score Matching. Before matching, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics of veterans who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with few exceptions (eAppendices 2 and 3, ).

Propensity Score Matching Results. Inspection of PSs revealed good coverage across treatment groups on a histogram plot and a kernel density plot (eAppendices 5 and 6).

Discussion

This QIP was the first to evaluate the impact of an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB in a large, integrated health care system in the U.S. It was also the first to demonstrate potential benefits of a DTC EB designed for older veterans who are long-term BZD users. In this QIP, which mailed the EB to 3,896 veterans, 1,847 (47.4%) decreased their BZD dose, 458 (11.7%) tapered and then discontinued BZD, and 455 (11.7%) immediately discontinued BZD. The total percentage of veterans who discontinued BZD (23.4%; 913/3,896) was similar to the 27% reported in the EMPOWER trial.17 However, the risk difference between the 1,316 EB-exposed VISN 22 veterans (QIP-1) and the 1,316 EB-unexposed VISN 21 veterans in this QIP was significantly lower than the 23% risk difference in EMPOWER (though it still demonstrated a significantly larger reduction for EB-exposed veterans).17

Given this inclusion of all qualifying veterans from the catchment area studied in this QIP, and given the ethical and practical concerns, an RCT was not possible. Therefore, PSM methods were used to balance the covariates across treatment groups and thereby simulate an RCT.21,22,27 With use of the PSM approach, findings from the descriptive analysis were confirmed and potential selection bias reduced.

Study Limitations

The less robust risk difference found in this QIP has several possible explanations. The authors’ use of a DTC EB coincided with a national VA effort to reduce older veterans’ use of BZDs and other inappropriate medications. For instance, during the study period, academic detailing was being implemented to reduce use of BZDs, particularly in combination with opioids, across VHA facilities and clinics. (Academic detailing is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20) However, QIP-2 results and PS analysis of a subgroup of the original sample suggest that EB-exposed veterans were significantly more likely than were their unexposed counterparts were to discontinue BZD. To an extent, this analysis controlled for these other efforts to reduce BZD use in VHA clinics and can be considered a study strength.

Another limitation is the study design, which lacked a control group and did not consider the possibility that some facility or clinic physicians might influence others. Although the region variable was controlled for in PSM, the authors did not capture facility characteristics, including frequency of prescribing BZD and use of a protocol for enforcing the Beers criteria. Such confounders might have influenced outcomes. Unlike the EMPOWER trial,17 this QIP did not assess or exclude cognitively impaired veterans. It is reasonable to assume that these veterans might not understand some EB messages and consequently might fail to engage their physicians. Failure to initiate discussion with a physician would attenuate the impact of the EB.

Study Strengths

A strength of this QIP was its use of a DTC EB in a large, regional sample of older veterans in a real-world clinical setting. In addition, the study group (EB-exposed veterans) and the comparator group (EB-unexposed veterans) were from similar geographic areas (primarily California and Nevada).

Conclusion

Results of this study suggest that a DTC EB, designed to reduce BZD use among older veterans, was effective in helping patients lower their BZD dose and discontinue BZD. The likelihood of discontinuing BZD 9 and 12 months after the index date was significantly higher for veterans who received an EB modeled on the EMPOWER educational brochure than for a comparator group of veterans who did not receive the EB and were receiving care during the same observation period. In the future, it would be beneficial to use a design that controls for physician exposure to academic detailing focused on BZD reduction and that accounts for the cluster effects of facility practice. Despite these limitations, this QIP is the first real-world empirical example of using an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB to decrease BZD use among older veterans. Furthermore, these results suggest that a DTC EB can be used to target other high-risk prescription drugs, such as opioids, particularly if alternative treatment options can be provided.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hauser thanks Cathy, Anika, Katia, and Max Hauser, and Alba and Kevin Quinlan, for their support. In memory of Jirina Hauser, who died on Mother’s Day, May 14, 2017, at the age of 100.

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are among the most commonly prescribed medications. A recent study found that in 2008, more than 5% of Americans used a BZD, and the percentage was almost 9% among Americans aged ≥ 65 years.1,2 Among veterans, BZD use is even higher, in part because of the high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). One study found that more than 30% of veterans with PTSD received at least 1 BZD prescription.3 The risks associated with BZD treatment for PTSD are compounded by concurrent use of other sedatives and opioids prescribed for co-occurring chronic pain and insomnia.3

Older adults metabolize long-acting BZDs more slowly and generally have an increased sensitivity to the adverse effects (AEs) of all BZDs.4 In older adults, BZD use has been associated with cognitive decline, dementia, falls and consequent fractures, and adverse respiratory outcomes.5-12 The risk of most but not all of these AEs was increased with higher BZD dose or long-term BZD use, which this quality improvement project (QIP) defines as having at least a 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year.

Long-term BZD use increases with age. One study found that, among patients receiving a BZD, the rate of long-term BZD use was more than double in older adults (31.4%) than it was in adults aged between 18 and 35 years (14.7%).2 For these reasons, the 2012 Beers criteria of the American Geriatrics Society recommend avoiding all types of BZDs in the treatment of insomnia, agitation, or delirium in patients aged > 65 years.13 Despite this recommendation, the prevalence of BZD use in older adults remains high.14

Some innovative approaches have been developed to address the inappropriate use, including overuse and misuse, of BZDs in older adults.15 In one approach, direct-to-consumer (DTC) information is used to empower patients to collaborate with their physician to manage their health. Results from several studies suggest that providing older patients with information on BZD risks and benefits increases patient–physician interaction and thereby decreases inappropriate BZD use and improves health outcomes.4,16,17 One study found that perceptions of BZD risks increased 1 week after exposure to a DTC educational brochure (EB), with intention to discuss BZD discontinuation with their physician higher for patients who received the EB than it was for those who did not (83.1% vs 44.3%; P < .0001).16 The EMPOWER (Eliminating Medications Through Patient Ownership of End Results) cluster randomized controlled trial assessed the effectiveness of a DTC EB focused on BZD risks in older adults.17 In that seminal study, patients who received a DTC EB were more likely than were comparison patients to discontinue BZD within 6 months (27% vs 5%; risk difference, 23%; 95% CI, 14%-32%).

The Veterans Integrated Systems Network (VISN) 22 Academic Detailing Program is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20 With BZD use among older veterans remaining high, the VISN 22 program initiated a clinical QIP modeled on the EMPOWER trial. Veterans in VISN 22 received the DTC EB, which included information on BZD risks and encouraged them to discuss their BZD treatment with their health care provider. VISN 22 was the first VISN in the VHA to implement the EMPOWER protocol.

As this was a QIP, all eligible veterans in VISN 22 were mailed the DTC EB, thus making it difficult to estimate the impact of the EB on BZD discontinuation in this VISN. Therefore, DTC EB efficacy was estimated by comparing BZD discontinuation between VISN 22 and VISN 21, an adjacent VISN that did not mail the DTC EB.

Methods

Two QIPs were undertaken to determine the impact of DTC EB on BZD use in older veterans in the VHA.

Quality Improvement Project 1

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis was performed. The VISN 22 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in southern California and southern Nevada, serves about 500,000 veterans, a substantial proportion of whom are aged ≥ 65 years. Among these older veterans are active long-term BZD users, who were defined as having ≥ 60-day supply of BZD prescriptions dispensed within the past year. Each active long-term user with a BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date (the date the user was to meet with the prescribing physician) was mailed an EB 2 to 8 weeks in advance of the visit. Excluded from analysis were veterans with a schizophrenia, spinal cord injury, or seizure disorder diagnosis recorded in both their inpatient and outpatient medical records; veterans seen by Palliative Care within the past year; and veterans who died before analysis was completed.

Education Brochure. The EB for VISN 22 (Figure 1, see

Patients. The sample consisted of all veterans identified as meeting the inclusion criteria and being enrolled in VISN 22. The EB was mailed once to veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016. Change in BZD use was analyzed only after 9 to 24 months had passed since the index appointment with the prescribing physician. This period included 12 weeks for BZD taper and then 6 months after taper.

Analysis. For each veteran, monthly mean lorazepam equivalent (LE) was calculated using as many as 12 fills before the index date. Average daily dose of LE was calculated by dividing the sum of LE from all included prescriptions by total number of days between the first fill and the index date. The BZD prescription fills were evaluated after the index date. Veterans who received at least 1 prescription after the index date but then had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics for 3 consecutive months during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having tapered and then discontinued BZD. Veterans who had no BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period were recorded as having discontinued BZD without tapering. For veterans who had BZD prescription activity in VA clinics after the index date and during the 9-month observation period, mean LE was calculated by dividing the total LE for BZD prescriptions after the index date by number of days from the first fill after the index date to the date of analysis.

Quality Improvement Project 2

Design. A retrospective cohort analysis using PSM was performed on a subgroup of the QIP-1 sample to evaluate the impact of EB on BZD prescribing in the VA during 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. Veterans in the analysis were active long-term BZD users, had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date, were aged ≥ 65 years, and had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescriber within 2 to 8 weeks (Figure 2).

Patients. VISN 22 implemented QIP-2, a real-world application of a modified EMPOWER program, by identifying eligible veterans on a rolling basis from December 2014 to August 2015. All veterans who were identified and sent an EB during this period were included in the case group. The index date was defined as the first of the month the EB was mailed. Veterans with a pending appointment were chosen because the lead time would allow them to receive the EB and prepare to discuss it with the physician during the visit.

A comparator group was drawn from the adjacent VISN 21 catchment area, which encompasses VA facilities and clinics in Hawaii, northern California, and northern Nevada. During the observation period, VISN 21 did not mail any EBs specifically addressing BZD risks. Veterans in the comparator group had an appointment scheduled with their BZD prescribing physician within 4 weeks, were aged ≥ 65 years on the index date (first of the month before the next appointment, coinciding with the date EBs were sent to VISN 22 veterans), were active long-term BZD users, and had at least 1 BZD prescription released within 200 days before the index date. All patients were followed for up to 12 months after the index date, with BZD discontinuation recorded 9 and 12 months after the index date.

Propensity Score Matching

Propensity score (PS) was estimated with logistic regression analysis with treatment as the dependent variable and baseline characteristics as the independent variables.21,22 One-to-one matching on the PS was performed using the nearest neighbor approach without replacements. Independent variables related to outcome but unrelated to EB exposure were selected for PS development.22 These variables included year of birth; male sex; Hispanic ethnicity; annual income; service connection status; region; body mass index; Charlson Comorbidity Index category; total baseline BZD dose; and diagnosis of AIDS, nonmetastatic cancer, metastatic cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), dementia, diabetes mellitus (DM), DM with complications, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), general anxiety disorder (GAD), hemiparaplegia, liver disease (mild), liver disease (moderate to severe), myocardial infarction (MI), Parkinson disease, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), psychosis, renal disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or substance use disorder (SUD).

The EMPOWER cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated the effectiveness of EB exposure in a Canadian population of elderly patients who were long-term BZD users.17 Randomized controlled trials are the gold standard for clinical trials because they can establish causal inference.23-25 Given ethical and practical concerns, however, RCTs cannot be applied to all clinical scenarios. Although EMPOWER is reported to be an effective tool in reducing BZD use in older adults, its application in a real-world, large, integrated health care system remains untested. Observational studies are often conducted as an alternative to RCTs but are subject to selection bias because of their lack of randomization.26 Therefore, robust research methods are needed to generate unbiased estimates of the impact of an intervention on an outcome. Propensity score matching simulates an RCT by balancing the covariates across treatment groups.21,22,27 Observed patient characteristics are used to estimate PS, the probability that treatment will be received. Logistic or probit regression is used to balance the potential confounding covariates between the treatment groups.Once PSs are known, mean treatment effect can be estimated without the mean model.28 In other words, PSM methods can be used to generate an unbiased estimate of the treatment.

Propensity Score Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared using Student t test (continuous variables) and χ2 test (discrete variables). Results are presented as means and standard deviations (continuous variables) and frequency and percentage (discrete variables).

The main outcome was BZD discontinuation 9 and 12 months after the index date. A postindex lag of 6 months was used to capture any tapering (Figure 2). Discontinuation, defined as 3 consecutive months of no BZD prescription on hand, was measured for 2 periods: 6 to 9 months and 6 to 12 months after the index date. A secondary outcome was discontinuation 1 to 12 months after the index date. An estimate was made of the difference in the proportions of BZD discontinuers who received the EB and BZD discontinuers who did not receive the EB, where mean treatment (risk difference) was presented as the absolute risk difference with a 95% CI. Standard errors and 95% CIs for the risk differences were generated with biased-corrected CIs from 1,000 bootstrap samples.

Sensitivity Analyses

Naïve multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between EB exposure and BZD discontinuation while controlling for potential confounders. Results are presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. Confounders identified were the same covariates used to generate the PSs.

Several analyses were performed to test the sensitivity of the methods applied using PSM by changing caliber size while maintaining the nearest neighbor approach without replacement. Linear regression analysis was performed with robust standard errors to estimate the risk difference of BZD discontinuation between EB-exposed and EB-unexposed veterans.

Statistical significance was set at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/SE Version 13 (College Station, TX).

Results

Quality Improvement Project 1

On a rolling basis from December 2014 to February 2016, the EB was mailed once to 3,896 VISN 22 veterans 2 to 8 weeks before a clinic appointment with their BZD prescribing physician.

Quality Improvement Project 2

Of all the VISN 22 and VISN 21 veterans, 24,420 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these 24,420 veterans, 2,020 (8.3%) were in VISN 22 and received the EB between December 2014 and August 2015 (QIP-1), and 22,400 (91.7%) were in VISN 21 and did not receive the EB.

Naïve Results Before PS Matching. In the naïve analyses, a larger proportion of EB-exposed vs unexposed veterans discontinued BZD; in addition, reductions were 6.6%, 7.4%, and 9.5% larger for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (P < .0001 for all comparisons; Table 2).

After controlling for potential confounders, the naïve logistic regression analyses found EB exposure was significantly associated with 44%, 32%, and 42% increases in the odds of BZD discontinuation for 6 to 9 months, 6 to 12 months, and 1 to 12 months after the index date, respectively (Table 3).

Propensity Score Matching. Before matching, there were significant differences in baseline characteristics of veterans who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with few exceptions (eAppendices 2 and 3, ).

Propensity Score Matching Results. Inspection of PSs revealed good coverage across treatment groups on a histogram plot and a kernel density plot (eAppendices 5 and 6).

Discussion

This QIP was the first to evaluate the impact of an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB in a large, integrated health care system in the U.S. It was also the first to demonstrate potential benefits of a DTC EB designed for older veterans who are long-term BZD users. In this QIP, which mailed the EB to 3,896 veterans, 1,847 (47.4%) decreased their BZD dose, 458 (11.7%) tapered and then discontinued BZD, and 455 (11.7%) immediately discontinued BZD. The total percentage of veterans who discontinued BZD (23.4%; 913/3,896) was similar to the 27% reported in the EMPOWER trial.17 However, the risk difference between the 1,316 EB-exposed VISN 22 veterans (QIP-1) and the 1,316 EB-unexposed VISN 21 veterans in this QIP was significantly lower than the 23% risk difference in EMPOWER (though it still demonstrated a significantly larger reduction for EB-exposed veterans).17

Given this inclusion of all qualifying veterans from the catchment area studied in this QIP, and given the ethical and practical concerns, an RCT was not possible. Therefore, PSM methods were used to balance the covariates across treatment groups and thereby simulate an RCT.21,22,27 With use of the PSM approach, findings from the descriptive analysis were confirmed and potential selection bias reduced.

Study Limitations

The less robust risk difference found in this QIP has several possible explanations. The authors’ use of a DTC EB coincided with a national VA effort to reduce older veterans’ use of BZDs and other inappropriate medications. For instance, during the study period, academic detailing was being implemented to reduce use of BZDs, particularly in combination with opioids, across VHA facilities and clinics. (Academic detailing is a pharmacy educational outreach program that uses unbiased clinical guidelines to promote physicians’ safety initiatives and align prescribing behavior with best practices.18-20) However, QIP-2 results and PS analysis of a subgroup of the original sample suggest that EB-exposed veterans were significantly more likely than were their unexposed counterparts were to discontinue BZD. To an extent, this analysis controlled for these other efforts to reduce BZD use in VHA clinics and can be considered a study strength.

Another limitation is the study design, which lacked a control group and did not consider the possibility that some facility or clinic physicians might influence others. Although the region variable was controlled for in PSM, the authors did not capture facility characteristics, including frequency of prescribing BZD and use of a protocol for enforcing the Beers criteria. Such confounders might have influenced outcomes. Unlike the EMPOWER trial,17 this QIP did not assess or exclude cognitively impaired veterans. It is reasonable to assume that these veterans might not understand some EB messages and consequently might fail to engage their physicians. Failure to initiate discussion with a physician would attenuate the impact of the EB.

Study Strengths

A strength of this QIP was its use of a DTC EB in a large, regional sample of older veterans in a real-world clinical setting. In addition, the study group (EB-exposed veterans) and the comparator group (EB-unexposed veterans) were from similar geographic areas (primarily California and Nevada).

Conclusion

Results of this study suggest that a DTC EB, designed to reduce BZD use among older veterans, was effective in helping patients lower their BZD dose and discontinue BZD. The likelihood of discontinuing BZD 9 and 12 months after the index date was significantly higher for veterans who received an EB modeled on the EMPOWER educational brochure than for a comparator group of veterans who did not receive the EB and were receiving care during the same observation period. In the future, it would be beneficial to use a design that controls for physician exposure to academic detailing focused on BZD reduction and that accounts for the cluster effects of facility practice. Despite these limitations, this QIP is the first real-world empirical example of using an EMPOWER-modeled DTC EB to decrease BZD use among older veterans. Furthermore, these results suggest that a DTC EB can be used to target other high-risk prescription drugs, such as opioids, particularly if alternative treatment options can be provided.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hauser thanks Cathy, Anika, Katia, and Max Hauser, and Alba and Kevin Quinlan, for their support. In memory of Jirina Hauser, who died on Mother’s Day, May 14, 2017, at the age of 100.

1. Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):7-20.

2. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

3. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Friedman MJ. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

4. Roberts KJ. Patient empowerment in the United States: a critical commentary. Health Expect. 1999;2(2):82-92.

5. Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(3):285-293.

6. van der Hooft CS, Schoofs MW, Ziere G, et al. Inappropriate benzodiazepine use in older adults and the risk of fracture. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(2):276-282.

7. Zint K, Haefeli WE, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Impact of drug interactions, dosage, and duration of therapy on the risk of hip fracture associated with benzodiazepine use in older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(12):1248-1255.

8. Finkle WD, Der JS, Greenland S, et al. Risk of fractures requiring hospitalization after an initial prescription for zolpidem, alprazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1883-1890.

9. de Gage SB, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231

10. Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639-658.

11. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

12. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Regular benzodiazepine and z-substance use and risk of dementia: an analysis of German claims data. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(2):801-808.

13. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

14. National Institutes of Health. Despite risks, benzodiazepine use highest in older people. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/despite-risks-benzodiaze pine-use-highest-older-people. Published December 17, 2014. Accessed July 31, 2018.

15. Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):89.

16. Martin P, Tamblyn R, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. A drug education tool developed for older adults changes knowledge, beliefs and risk perceptions about inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions in the elderly. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):81-87.

17. Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-898.

18. Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263(4):549-556.

19. Fischer MA, Avorn J. Academic detailing can play a key role in assessing and implementing comparative effectiveness research findings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2206-2212.

20. Wells DL, Popish S, Kay C, Torrise V, Christopher ML. VA Academic Detailing Service: implementation and lessons learned. Fed Pract. 2016;33(5):38-42.

21. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424.

22. Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1149-1156.

23. Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Ed Psych. 1974;66(5):688-701.

24. Greenland S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(4):722-729.

25. Cartwright N. What are randomized controlled trials good for? Philos Stud. 2010;147(1):59.

26. Kleinbaum DG, Morgenstern H, Kupper LL. Selection bias in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113(4):452-463.

27. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55.

28. Pirracchio R, Carone M, Rigon MR, Caruana E, Mebazaa A, Chevret S. Propensity score estimators for the average treatment effect and the average treatment effect on the treated may yield very different estimates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(5):1938-1954.

1. Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(1):7-20.

2. Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(2):136-142.

3. Bernardy NC, Lund BC, Alexander B, Friedman MJ. Increased polysedative use in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1083-1090.

4. Roberts KJ. Patient empowerment in the United States: a critical commentary. Health Expect. 1999;2(2):82-92.

5. Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alpérovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: the Epidemiology of Vascular Aging Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(3):285-293.

6. van der Hooft CS, Schoofs MW, Ziere G, et al. Inappropriate benzodiazepine use in older adults and the risk of fracture. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(2):276-282.

7. Zint K, Haefeli WE, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Impact of drug interactions, dosage, and duration of therapy on the risk of hip fracture associated with benzodiazepine use in older adults. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(12):1248-1255.

8. Finkle WD, Der JS, Greenland S, et al. Risk of fractures requiring hospitalization after an initial prescription for zolpidem, alprazolam, lorazepam, or diazepam in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1883-1890.

9. de Gage SB, Bégaud B, Bazin F, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2012;345:e6231

10. Tannenbaum C, Paquette A, Hilmer S, Holroyd-Leduc J, Carnahan R. A systematic review of amnestic and non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment induced by anticholinergic, antihistamine, GABAergic and opioid drugs. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(8):639-658.

11. Vozoris NT, Fischer HD, Wang X, et al. Benzodiazepine drug use and adverse respiratory outcomes among older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(2):332-340.

12. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Regular benzodiazepine and z-substance use and risk of dementia: an analysis of German claims data. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(2):801-808.

13. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

14. National Institutes of Health. Despite risks, benzodiazepine use highest in older people. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/despite-risks-benzodiaze pine-use-highest-older-people. Published December 17, 2014. Accessed July 31, 2018.

15. Airagnes G, Pelissolo A, Lavallée M, Flament M, Limosin F. Benzodiazepine misuse in the elderly: risk factors, consequences, and management. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):89.

16. Martin P, Tamblyn R, Ahmed S, Tannenbaum C. A drug education tool developed for older adults changes knowledge, beliefs and risk perceptions about inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions in the elderly. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):81-87.

17. Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, Benedetti A, Ahmed S. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890-898.

18. Soumerai SB, Avorn J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA. 1990;263(4):549-556.

19. Fischer MA, Avorn J. Academic detailing can play a key role in assessing and implementing comparative effectiveness research findings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2206-2212.

20. Wells DL, Popish S, Kay C, Torrise V, Christopher ML. VA Academic Detailing Service: implementation and lessons learned. Fed Pract. 2016;33(5):38-42.

21. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424.

22. Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(12):1149-1156.

23. Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J Ed Psych. 1974;66(5):688-701.

24. Greenland S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(4):722-729.

25. Cartwright N. What are randomized controlled trials good for? Philos Stud. 2010;147(1):59.

26. Kleinbaum DG, Morgenstern H, Kupper LL. Selection bias in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1981;113(4):452-463.

27. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55.

28. Pirracchio R, Carone M, Rigon MR, Caruana E, Mebazaa A, Chevret S. Propensity score estimators for the average treatment effect and the average treatment effect on the treated may yield very different estimates. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(5):1938-1954.

New Treatments for Hepatitis C

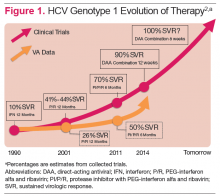

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remains a significant problem in the VA system, with over 174,000 current actively infected patients.1 Despite the availability of antiviral treatment since the early 1990’s, only approximately 26% of patients have ever been treated. These treatments required the use of pegylated interferon alfa (PEG) and ribavirin (RBV), which are associated with significant adverse events (AEs) that prevented many from receiving the treatment. Of those treated, only a minority achieved a sustained virologic response (SVR), due to the limited efficacy of the treatments (Figure 1).2 With the advent of new direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments in 2011, treatment efficacy improved.

The first DAAs in use were the viral nonstructural protein 3/4A (NS3/4A) serine protease inhibitors (PIs) boceprevir and telaprevir, which were used with PEG and RBV for patients with HCV genotype 1 infection. This combination therapy improved SVR rates from about 26% to 50% in patients with HCV genotype 1 in the VA.3,4 However, due to the significant AEs with these combinations, relatively few patients were treated.

In late 2013, the FDA approved other DAAs, which allowed patients to be treated effectively without PEG. These included the nucleotide nonstructural protein 5B (NS5B) polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir and a secondgeneration NS3/4A PI simeprevir.5-7 The first nucleotide analog NS5B polymerase inhibitor, sofosbuvir and the nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) replication complex inhibitor, ledipasvir, was approved in October 2014.8-10 The recent developments in noninterferon treatments have been accompanied by revised treatment guidelines or recommendations by major professional societies. Current treatment recommendations will be reviewed here, but the recommendations will continue to evolve as new DAAs come to market.

DAA Sites of Action

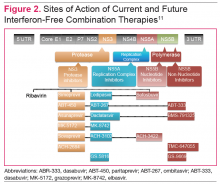

The HCV genome is a positive-stranded RNA molecule of about 9,500 nucleotides, which encodes a polyprotein of approximately 3,000 amino acids that form 10 individual viral proteins. These are composed of both structural and nonstructural (NS) proteins that are responsible for replication of the genome and formation of new viral particles. Understanding of the HCV-encoded proteins and their functions has permitted the development of different DAA therapies. In general, targeting a single protein is not effective, and combination therapy targeting 2 proteins is required for viral eradication (Figure 2).11 The 3 drug targets that are currently available include NS3/4A serine PIs (eg, simeprevir, boceprevir, telaprevir), NS5A replication complex inhibitors (eg, ledipasvir, daclatasvir), and NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors (eg, sofosbuvir).

Other DAA’s are in development that have targets in host rather than viral cells. These include cycolphilin A inhibitors and the micro-RNA (miR-122) antagonist miravirsen.12,13

The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, encoded by the HCV NS5B is targeted by 2 classes of inhibitors: nucleoside or nucleotide analog inhibitors (NIs), and non-nucleoside inhibitors (NNIs).11 The only NI of the NS5B protein approved by the FDA is sofosbuvir. The resistance profiles of NIs and NNIs differ, because they bind to distinct sites on the NS5B protein. NIs are analogs of natural substrates and bind to the active site of the RNA polymerase, whereas NNIs are allosteric site inhibitors. NIs have activity in vitro against all HCV genotypes and have high barrier to resistance as the active site of NS5B polymerase is less tolerant of different amino acid substitutions.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that NIs are less likely to select for mutations compared with NNIs and PIs. The NNIs have limited genotypic coverage and have a lower barrier to resistance. Strategies for targeting HCV proteins include using a NI NS5B protein inhibitor as the backbone with a high barrier to resistance in combination with 1 or 2 other DAAs with lower barriers to resistance, or the combination of 3 DAAs with lower barriers to resistance.11 Ribavirin has broad-spectrum antiviral activity, one of which is anti-HCV activity. The mode of action of RBV against HCV is not well understood, but several mechanisms have been proposed, one of which is via inhibition of viral-dependent RNA polymerase.

Current HCV Treatment Recommendations

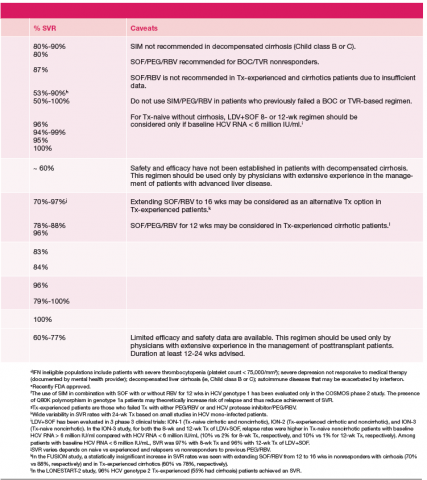

Current treatment recommendations are available from the American Association for the Study of the Liver Disease (AASLD) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) (http://www.hcvguidelines.org); the VA National Hepatitis C Resource Center Program and Office of Public Health (http://www.hepatitis.va.gov/pdf/2014hcv.pdf); and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) (http://www.easl.eu/_newsroom/latest-news/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-c-2014). These recommendations are updated frequently as new drugs enter the marketplace (Table 1).14-16

Since most patients are unable or unwilling to tolerate interferon, the majority of patients in treatment are currently receiving interferon-free combinations. Treatment of genotype 1 is currently dominated by the offlabel use of sofosbuvir in combination with simeprevir. Data have been published from a single phase II trial in patients with and without cirrhosis.7 Of note are emerging data from observational studies confirming the efficacy of over 80% SVR in patients with cirrhosis and genotype 1a with or without prior treatment.17 Treatment of patients with genotype 2 infection is dominated by the use of sofosbuvir and RBV combination. However, patients with cirrhosis do not respond as well as patients without cirrhosis, and it remains to be seen whether extending therapy is of any benefit.

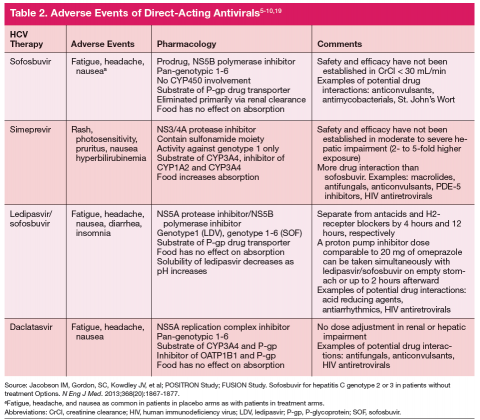

One exception for the use of PEG is the recommendation for patients with HCV genotype 3 and cirrhosis to consider the combination of PEG, RBV, and sofosbuvir for 12 weeks.18 This has the advantage of being more effective, less costly, and shorter treatment duration compared with the sofosbuvir and RBV association but is only appropriate for patients who can tolerate interferon. Common AEs and potential contraindications to treatment are listed in Table 2.5-10,19

New Treatment Options for HCV in 2015

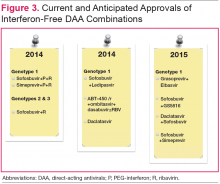

Figure 3 details DAA combinations currently in phase III trials that are expected to receive approval in 2015. This will expand the repertoire of drug combinations available and enable fine-tuning of regimens according to patient and viral characteristics and cost requirements.

Cost and Effectiveness