User login

That’s What They Said

I stare; a brimming audience stares back. Two eyeballs battling thousands. Slightly uncomfortable, I shift my weight, trying to hide behind the glass podium. Two microphones snake out of the podium slithering together inches from my mouth. The attendees squirm, sidle to the edge of their seats, restless to depart. HM11 is trying to close; only I stand in its way.

A Herculean task lies before me—summarize the annual meeting in a 10-minute wrap-up session titled “What We’ve Learned.” How do you summarize four days, eight pre-courses, nine breakout tracks, and more than 100 presentations in a few minutes? A bead of forehead sweat forms; I clear my throat. Memories of the past few days slide-show across my mind. It occurs to me that the essence of the meeting is not contained in the data, the information, or the PowerPoint slides that were presented. Rather, the story of HM11 is best told through its quotes.

Patient Caps: Your Grandmother and Professionalism

“I worry about patient caps because the next patient could be your grandmother.”

—Joe Li, MD, SFHM, new president of SHM

“Patient caps are the greatest threat to the professionalism of the field.”

—Rob Bessler, MD, CEO, Sound Inpatient Physicians

These two quotes from the opening plenary focused on the 2011 HM compensation and productivity survey particularly stuck out. The most noteworthy exchange came when Drs. Li and Bressler commented on the appropriate number of daily encounters for a hospitalist. The quotes highlight two important points about patient volume, especially in the wake of the training regulations that limit the number of resident physician encounters, which can engender a “cap mentality.” One is that it matters; there is a safe amount of encounters that shouldn’t routinely be breached. Two is that in the heat of the moment, Patient 19 is as important as Patient 11 and should be treated as such. Contingency plans are essential, but our field is built on the moorings of professionalism—the focus needs to be on humans, not numbers.

Hospitalist Compensation: Increasing but Not as Juicy

“It’s not going to get less anytime soon.”

—Dr. Bressler

In commenting on the data showing that the average community hospitalist makes about $220,000 annually—a 3% increase over last year—while producing around 4,000 work RVUs—flat over last year—and that their academic counterparts made $173,000 on about 3,400 wRVUs, Dr. Bressler opined that the laws of supply and demand would dictate that salaries would continue to rise for the near term. Although I agree with Dr. Bressler, my guess is that future salary increases will be driven more by quality than quantity (more to follow below).

“Juice-to-squeeze ratio”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, SHM cofounder

Dr. Nelson highlighted interesting data showing that the average pay per wRVU was approximately $54. However, he noted that the compensation per wRVU tends to peak at a certain level, after which compensation per wRVU falls. In other words, after, say, 4,000 wRVUs, the amount of compensation per wRVU diminishes such that seeing more patients benefits an individual hospitalist less. That is, lots of squeeze, little juice at the high end.

Reform: Variety, Change, and Waste

“Variety is about choice; change is not.”

—Cecil Wilson, MD, AMA president

“You won’t have many more conferences where you start by talking about work RVUs.”

—Bob Kocher, MD, former special assistant to President Obama

The highlight of the conference for me was Dr. Kocher’s behind-the-scenes look at what was a very publicly muddy event—the passage of ACA. Coming from a D.C. insider, this under-the-covers peek at the machinations that went into passing the healthcare reform bill was fascinating.

The key message, summarized in this comment referring to the opening plenary about hospitalist compensation and productivity, was that the future is quality and the future is now. In the very near future, we will be measured and paid based on our ability to effect quality outcomes, not patient encounters. The message was simple: It’s about quality, not quantity.

“It costs $7.50 for a healthcare transaction, versus 2 cents for a VISA transaction.”

—Dr. Kocher

A statistic I had not heard before, this quote sums up one of the major problems with American healthcare: waste. The $7.50 transaction he was referring to was the amount of money it takes to file a healthcare claim. We certainly feel it in the challenges of documentation, billing, and denials, but the system feels it in terms of high cost of capturing what in many ways should be as simple as swiping your credit card at Starbucks.

Duty-Hour Restrictions: Harbinger of The Future?

“Don’t begrudge the ACGME—begrudge us.”

—Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, SHM past president

In a much-anticipated session on the impact of the new ACGME residency work-hour rules commencing in July—notably limiting intern (16-hour) and resident (28-hour) shift duration—Dr. Wiese aptly pointed out that a lot of the angst toward residency work environment regulation could have been avoided if physician leadership had better reacted to the issues of sleep deprivation and resident fatigue following Libby Zion’s death in 1984. Had we put our energy into improving work conditions rather than debate the impact of sleep deprivation on the outcome in this one case, we might be in a different place today.

I couldn’t help but wonder if the message here could also be applied to society’s push for higher quality, lower cost, and safer care. Either we regulate ourselves or someone else will. In other words, we need to embrace quality and safety, or it will be thrust upon us from external sources in ways we might not like.

A Mariner Calls

“I love you, Papi. Come home and take some baseball cuts.”

—Greyson Glasheen, future Major League Baseball shortstop

I wrote in a column leading up to the annual meeting (see “Annual Meeting Mariner,” April 2011, p. 45) that I was looking forward to the meeting because it was a professional mariner of sorts, a way for me to refresh, reset, and reinvigorate. Indeed, reflecting from the podium, it had been a fantastic meeting that served its purpose well. I had learned a ton, caught up with colleagues I hadn’t seen since the last meeting, saw old medical school friends, and met future old friends. I’d led a committee, given a talk, presented a poster, met up with a mentor, and had a reunion with past attendees of the Academic Hospitalist Academy.

Yet I was ready to get back to normalcy. On the last night of the meeting, I was therefore drawn by a different, more personal mariner—this time, a 14-second voicemail message from a 3-year-old boy waiting impatiently for Dad to come home, to make him his center, to simply play a little tee ball in the backyard. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

I stare; a brimming audience stares back. Two eyeballs battling thousands. Slightly uncomfortable, I shift my weight, trying to hide behind the glass podium. Two microphones snake out of the podium slithering together inches from my mouth. The attendees squirm, sidle to the edge of their seats, restless to depart. HM11 is trying to close; only I stand in its way.

A Herculean task lies before me—summarize the annual meeting in a 10-minute wrap-up session titled “What We’ve Learned.” How do you summarize four days, eight pre-courses, nine breakout tracks, and more than 100 presentations in a few minutes? A bead of forehead sweat forms; I clear my throat. Memories of the past few days slide-show across my mind. It occurs to me that the essence of the meeting is not contained in the data, the information, or the PowerPoint slides that were presented. Rather, the story of HM11 is best told through its quotes.

Patient Caps: Your Grandmother and Professionalism

“I worry about patient caps because the next patient could be your grandmother.”

—Joe Li, MD, SFHM, new president of SHM

“Patient caps are the greatest threat to the professionalism of the field.”

—Rob Bessler, MD, CEO, Sound Inpatient Physicians

These two quotes from the opening plenary focused on the 2011 HM compensation and productivity survey particularly stuck out. The most noteworthy exchange came when Drs. Li and Bressler commented on the appropriate number of daily encounters for a hospitalist. The quotes highlight two important points about patient volume, especially in the wake of the training regulations that limit the number of resident physician encounters, which can engender a “cap mentality.” One is that it matters; there is a safe amount of encounters that shouldn’t routinely be breached. Two is that in the heat of the moment, Patient 19 is as important as Patient 11 and should be treated as such. Contingency plans are essential, but our field is built on the moorings of professionalism—the focus needs to be on humans, not numbers.

Hospitalist Compensation: Increasing but Not as Juicy

“It’s not going to get less anytime soon.”

—Dr. Bressler

In commenting on the data showing that the average community hospitalist makes about $220,000 annually—a 3% increase over last year—while producing around 4,000 work RVUs—flat over last year—and that their academic counterparts made $173,000 on about 3,400 wRVUs, Dr. Bressler opined that the laws of supply and demand would dictate that salaries would continue to rise for the near term. Although I agree with Dr. Bressler, my guess is that future salary increases will be driven more by quality than quantity (more to follow below).

“Juice-to-squeeze ratio”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, SHM cofounder

Dr. Nelson highlighted interesting data showing that the average pay per wRVU was approximately $54. However, he noted that the compensation per wRVU tends to peak at a certain level, after which compensation per wRVU falls. In other words, after, say, 4,000 wRVUs, the amount of compensation per wRVU diminishes such that seeing more patients benefits an individual hospitalist less. That is, lots of squeeze, little juice at the high end.

Reform: Variety, Change, and Waste

“Variety is about choice; change is not.”

—Cecil Wilson, MD, AMA president

“You won’t have many more conferences where you start by talking about work RVUs.”

—Bob Kocher, MD, former special assistant to President Obama

The highlight of the conference for me was Dr. Kocher’s behind-the-scenes look at what was a very publicly muddy event—the passage of ACA. Coming from a D.C. insider, this under-the-covers peek at the machinations that went into passing the healthcare reform bill was fascinating.

The key message, summarized in this comment referring to the opening plenary about hospitalist compensation and productivity, was that the future is quality and the future is now. In the very near future, we will be measured and paid based on our ability to effect quality outcomes, not patient encounters. The message was simple: It’s about quality, not quantity.

“It costs $7.50 for a healthcare transaction, versus 2 cents for a VISA transaction.”

—Dr. Kocher

A statistic I had not heard before, this quote sums up one of the major problems with American healthcare: waste. The $7.50 transaction he was referring to was the amount of money it takes to file a healthcare claim. We certainly feel it in the challenges of documentation, billing, and denials, but the system feels it in terms of high cost of capturing what in many ways should be as simple as swiping your credit card at Starbucks.

Duty-Hour Restrictions: Harbinger of The Future?

“Don’t begrudge the ACGME—begrudge us.”

—Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, SHM past president

In a much-anticipated session on the impact of the new ACGME residency work-hour rules commencing in July—notably limiting intern (16-hour) and resident (28-hour) shift duration—Dr. Wiese aptly pointed out that a lot of the angst toward residency work environment regulation could have been avoided if physician leadership had better reacted to the issues of sleep deprivation and resident fatigue following Libby Zion’s death in 1984. Had we put our energy into improving work conditions rather than debate the impact of sleep deprivation on the outcome in this one case, we might be in a different place today.

I couldn’t help but wonder if the message here could also be applied to society’s push for higher quality, lower cost, and safer care. Either we regulate ourselves or someone else will. In other words, we need to embrace quality and safety, or it will be thrust upon us from external sources in ways we might not like.

A Mariner Calls

“I love you, Papi. Come home and take some baseball cuts.”

—Greyson Glasheen, future Major League Baseball shortstop

I wrote in a column leading up to the annual meeting (see “Annual Meeting Mariner,” April 2011, p. 45) that I was looking forward to the meeting because it was a professional mariner of sorts, a way for me to refresh, reset, and reinvigorate. Indeed, reflecting from the podium, it had been a fantastic meeting that served its purpose well. I had learned a ton, caught up with colleagues I hadn’t seen since the last meeting, saw old medical school friends, and met future old friends. I’d led a committee, given a talk, presented a poster, met up with a mentor, and had a reunion with past attendees of the Academic Hospitalist Academy.

Yet I was ready to get back to normalcy. On the last night of the meeting, I was therefore drawn by a different, more personal mariner—this time, a 14-second voicemail message from a 3-year-old boy waiting impatiently for Dad to come home, to make him his center, to simply play a little tee ball in the backyard. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

I stare; a brimming audience stares back. Two eyeballs battling thousands. Slightly uncomfortable, I shift my weight, trying to hide behind the glass podium. Two microphones snake out of the podium slithering together inches from my mouth. The attendees squirm, sidle to the edge of their seats, restless to depart. HM11 is trying to close; only I stand in its way.

A Herculean task lies before me—summarize the annual meeting in a 10-minute wrap-up session titled “What We’ve Learned.” How do you summarize four days, eight pre-courses, nine breakout tracks, and more than 100 presentations in a few minutes? A bead of forehead sweat forms; I clear my throat. Memories of the past few days slide-show across my mind. It occurs to me that the essence of the meeting is not contained in the data, the information, or the PowerPoint slides that were presented. Rather, the story of HM11 is best told through its quotes.

Patient Caps: Your Grandmother and Professionalism

“I worry about patient caps because the next patient could be your grandmother.”

—Joe Li, MD, SFHM, new president of SHM

“Patient caps are the greatest threat to the professionalism of the field.”

—Rob Bessler, MD, CEO, Sound Inpatient Physicians

These two quotes from the opening plenary focused on the 2011 HM compensation and productivity survey particularly stuck out. The most noteworthy exchange came when Drs. Li and Bressler commented on the appropriate number of daily encounters for a hospitalist. The quotes highlight two important points about patient volume, especially in the wake of the training regulations that limit the number of resident physician encounters, which can engender a “cap mentality.” One is that it matters; there is a safe amount of encounters that shouldn’t routinely be breached. Two is that in the heat of the moment, Patient 19 is as important as Patient 11 and should be treated as such. Contingency plans are essential, but our field is built on the moorings of professionalism—the focus needs to be on humans, not numbers.

Hospitalist Compensation: Increasing but Not as Juicy

“It’s not going to get less anytime soon.”

—Dr. Bressler

In commenting on the data showing that the average community hospitalist makes about $220,000 annually—a 3% increase over last year—while producing around 4,000 work RVUs—flat over last year—and that their academic counterparts made $173,000 on about 3,400 wRVUs, Dr. Bressler opined that the laws of supply and demand would dictate that salaries would continue to rise for the near term. Although I agree with Dr. Bressler, my guess is that future salary increases will be driven more by quality than quantity (more to follow below).

“Juice-to-squeeze ratio”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, SHM cofounder

Dr. Nelson highlighted interesting data showing that the average pay per wRVU was approximately $54. However, he noted that the compensation per wRVU tends to peak at a certain level, after which compensation per wRVU falls. In other words, after, say, 4,000 wRVUs, the amount of compensation per wRVU diminishes such that seeing more patients benefits an individual hospitalist less. That is, lots of squeeze, little juice at the high end.

Reform: Variety, Change, and Waste

“Variety is about choice; change is not.”

—Cecil Wilson, MD, AMA president

“You won’t have many more conferences where you start by talking about work RVUs.”

—Bob Kocher, MD, former special assistant to President Obama

The highlight of the conference for me was Dr. Kocher’s behind-the-scenes look at what was a very publicly muddy event—the passage of ACA. Coming from a D.C. insider, this under-the-covers peek at the machinations that went into passing the healthcare reform bill was fascinating.

The key message, summarized in this comment referring to the opening plenary about hospitalist compensation and productivity, was that the future is quality and the future is now. In the very near future, we will be measured and paid based on our ability to effect quality outcomes, not patient encounters. The message was simple: It’s about quality, not quantity.

“It costs $7.50 for a healthcare transaction, versus 2 cents for a VISA transaction.”

—Dr. Kocher

A statistic I had not heard before, this quote sums up one of the major problems with American healthcare: waste. The $7.50 transaction he was referring to was the amount of money it takes to file a healthcare claim. We certainly feel it in the challenges of documentation, billing, and denials, but the system feels it in terms of high cost of capturing what in many ways should be as simple as swiping your credit card at Starbucks.

Duty-Hour Restrictions: Harbinger of The Future?

“Don’t begrudge the ACGME—begrudge us.”

—Jeff Wiese, MD, SFHM, SHM past president

In a much-anticipated session on the impact of the new ACGME residency work-hour rules commencing in July—notably limiting intern (16-hour) and resident (28-hour) shift duration—Dr. Wiese aptly pointed out that a lot of the angst toward residency work environment regulation could have been avoided if physician leadership had better reacted to the issues of sleep deprivation and resident fatigue following Libby Zion’s death in 1984. Had we put our energy into improving work conditions rather than debate the impact of sleep deprivation on the outcome in this one case, we might be in a different place today.

I couldn’t help but wonder if the message here could also be applied to society’s push for higher quality, lower cost, and safer care. Either we regulate ourselves or someone else will. In other words, we need to embrace quality and safety, or it will be thrust upon us from external sources in ways we might not like.

A Mariner Calls

“I love you, Papi. Come home and take some baseball cuts.”

—Greyson Glasheen, future Major League Baseball shortstop

I wrote in a column leading up to the annual meeting (see “Annual Meeting Mariner,” April 2011, p. 45) that I was looking forward to the meeting because it was a professional mariner of sorts, a way for me to refresh, reset, and reinvigorate. Indeed, reflecting from the podium, it had been a fantastic meeting that served its purpose well. I had learned a ton, caught up with colleagues I hadn’t seen since the last meeting, saw old medical school friends, and met future old friends. I’d led a committee, given a talk, presented a poster, met up with a mentor, and had a reunion with past attendees of the Academic Hospitalist Academy.

Yet I was ready to get back to normalcy. On the last night of the meeting, I was therefore drawn by a different, more personal mariner—this time, a 14-second voicemail message from a 3-year-old boy waiting impatiently for Dad to come home, to make him his center, to simply play a little tee ball in the backyard. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Annual Meeting Mariner

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

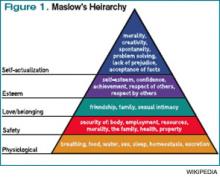

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

It’s been one of those days. It all started at 4:30 this morning, when my 3-year-old son crawled into our bed, naked except for the diarrhea dripping down his leg. Turns out, this was his way—quite effective, I might add—of telling my wife and me that he had had an “accident.” After an hour of carrying soiled sheets to the washer, child-bathing, and Weimaraner coat-scrubbing, we relaxed to the sound of our 1-year-old daughter’s blood-curdling screams.

Upon examination, we found that the night had mysteriously transformed our precious little button-nosed bundle of joy into a tangle-haired, snot-nosed bundle of melancholy. Where her face used to be, there now hung something approximating the mask from that Scream movie. Additionally, her throat was raw, olive-sized lymph nodes populated her neck, and her nose had taken to perpetual booger-manufacturing. A rapid strep swab would later reveal the culprit, but at the moment, our differential tilted toward demonic possession.

That Dripping Feeling

Moments later, my wife and I picked 6:15 a.m. as the time to discover that we both had 7 a.m. meetings and no time to drop the kids off at daycare, especially when factoring in the 10-minute “discussion” we had about who was going to drop the kids off at daycare. All of this preceded my 7:10 a.m. arrival time for the 7 o’clock meeting with a hospital executive team to discuss our HM group funding for the next year—an encounter that left me feeling as my son must have just prior to crawling into bed with us that morning.

Now 8 a.m., I had to meet with a surgeon eager to unveil his “great idea” for our hospitalists to admit all of his patients. “It solves our problem of no interns, and allows you to play a meaningful role in the hospital!” he exclaimed.

“The meaningful role of intern?” I replied. Again, I had that dripping feeling.

It was 8:30 a.m. and I was ready to round on my patients. The first patient, a lovely woman, was stricken with un-insure-ia and a deep-seated belief that the inequitable health system that rendered her unable to get her surgery was clearly the result of some moral failing on my part. Next up was a spectacularly intoxicated male who welcomed my caring touch by belching a bit of breakfast burrito onto my cheek. Then it was a floridly bipolar patient whose apparent life mission was to drop her pants to show me her new mesh thong.

Burnout, Respect, Satisfaction

And so it continued until 1 p.m., when I had a meeting with a resident mentee of mine. It turns out that he wanted to tell me that despite his desire to be a hospitalist since his fourth year of medical school, he instead was going to apply to a rheumatology fellowship. After talking to several practicing hospitalists, he’d decided it just wasn’t for him—discussions he summarized as too much burnout, too little respect, and not enough satisfaction. Again, that dripping feeling.

Stuffing my face with a vending-machine carb-load that doubled as both breakfast and lunch, I sat down for a few minutes of e-mail. First up, a journal rejection of a research paper we’d recently submitted. Oh, the fulfillment of academics. Next were two e-mails that enzymatically trebled my “to do” list for the day. Sandwiched between those e-mails and one from a friend reminding me not to be late for a dinner that night that I was clearly going to be late for was an e-mail from a nice-appearing Nigerian man wanting to give me millions of dollars; at last, my day was turning around.

Alas, this was not the case. Checking my voicemail, I found out that my uncle was in the hospital, my dog’s lab tests were abnormal, my mom was angry about something, and I had missed a dentist appointment that morning. Finally, our group assistant came with a message that our prized hospitalist recruit had accepted a job at another institution. Drip … drip … drip…

Self-Reflection

Now 2:30 p.m., I took stock of my day and reflected on what my resident mentee had said about hospitalists. Trying to balance the rigors of patient care, academic requirements, life, friends, family, and being a boss, I was most definitely feeling a bit downtrodden, unsated, and crispy around the edges. What, exactly, did I like about this job? Was this what I wanted professionally? Would I ever find balance? Perhaps, too, a rheumatology application could salve my problems.

It was at that point that the notice for the SHM annual meeting appeared, oracle-like, on my desk. Picking it up, I realized this, not a two-year sojourn through the world of creaky joints, was the tonic to my problems.

Meeting Hierarchy

Every year since I began going to the SHM annual meeting in 2003, the meeting has helped me rejuvenate and grow. Much like Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which posits that humans develop in stages that build on each other, I’ve found stepwise growth in the annual meeting.

Before my first meeting, I had been wandering nomadically through a hospitalist job for three years, wondering what, exactly, I was doing. I was the only hospitalist in my group, had few days off, with no support system around me. I had just agreed to take a job at another institution to build a new 10-person hospitalist group and had no idea how to do this. In Maslow terms, I was trying to satisfy my “physiologic needs” to survive. I needed to find, metaphorically, “food, water, clothes, and shelter.”

I found them at the annual meeting. The practice-management pre-course taught me how to build a hospitalist group, the mentorship breakfast introduced me to a veteran I still turn to, and the educational offerings helped improve my patient-care skills. I had conquered the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

The next year, I became involved in an SHM committee, and our gathering at the annual meeting helped set the course for our group’s future endeavors. I also met up with many friends I hadn’t seen since medical school and even recruited a person to my new group. In Maslow-speak, the meeting was helping me achieve my “safety needs” by providing control, well-being, and predictability.

By the third year, I was beginning to look forward to meeting up with national colleagues I had met at prior annual meetings, fulfilling Maslow’s third-stage need of “belonging.” During the ensuing years, I presented research projects, gave talks, and helped develop and lead forums and summits, thus quenching Maslow’s “self-esteem” need.

I wonder, as I leave my office to go back to see my afternoon complement of new patients, what my ninth annual meeting will bring. I’m not sure if I’ll ever achieve Maslow’s final phase of “self-actualization,” mostly because I’m not entirely sure what that means. However, I do know this: This job can be tough. We all feel it regardless of our age, gender, or practice setting. It is easy to get knocked out of balance, to get beaten down, to lose our focus. It is at those times that we all need a mariner to right the course. To remind us why we do this, to allow us to recharge, to facilitate our growth, to fulfill our needs.

For me, that mariner is the annual meeting. I look forward to seeing you all in Dallas next month. TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

Minivan, Major Lesson

I recently visited my parents in my ancestral home of Wisconsin. As parents of a certain age, they inexplicably are genetically predisposed to owning a minivan. Another quirk of their DNA is that they must own a new minivan. No sooner has the last wisp of new-car smell osmosed from the burled walnut interior than they are trading up to the newest, tricked-out minivan. Perhaps more puzzling is the manner of pride they display in their minivan.

Now, my dad, as if not readily apparent, is not cool. And to see him folded into the driver’s seat, his furry-ear-to-furry-ear grin signaling a self-satisfaction customarily reserved for his grandchildren, painstakingly recounting glory-day stories and 4:30 p.m. dinner buffets, further solidifies his place in the Annals of Uncool.

When I’m home, they tend to employ my chauffeur services (most likely in retribution for my peri-pubescent years), and on the first day back home, I stopped their newest ride near the back door of the house, foot idling on the brake while this exchange occurred: “That’s a fascinating story about how much more challenging the world was when you were my age, Dad. You are a true American hero. Would you like to get out here or in the garage?”

“Here,” he replied.

“OK, then get out,” I countered.

“I can’t,” he responded knowingly.

“Why not?” I queried, the patience seeping from my voice.

“Because the door’s not open,” he answered, seemingly mocking me.

“Then open it,” I replied, silently recounting the evidence for his institutionalization.

“I can’t,” he responded.

“Why not?” I replied again, this time calculating the likelihood that I was adopted.

“Because it’s locked,” came his retort.

“Then unlock it,” I answered, reconfirming my decision to move away for college.

“I can’t,” he replied, ostensibly encouraging parenticide.

“Why not?” I queried, strongly contemplating parenticide.

“Because you haven’t put the car in park,” he responded triumphantly.

A System So Safe

As a safety feature, the minivan needed to be in park before you could open the door to exit. I’ve never heard of anyone actually falling out of a moving car, but recollecting high school, I can fathom the right mix, type, and number of teenagers where possibility would meet inevitability. But, apparently, enough people are falling out of moving vehicles that car engineers have built a system that is so safe, this can’t happen. So no matter how hard someone tries, it just isn’t possible to fall out of a moving car (believe me, toward the end of a week of my father’s car stories, my mind had worked every possible angle).

Likewise, newer vehicles employ occupant-sensitive sensors that detect the weight, size, and position of the passenger to determine if the airbag should deploy. Rather than depending on the driver to turn the passenger-side airbag on or off, the car does it for you: heavy enough to trigger the sensor, and the airbag will deploy; too light, and the car assumes you are a child and doesn’t deploy. It’s a system that is so safe because it doesn’t depend on the operator to get it right.

Ditto motion sensors that detect objects behind the car while reversing (avoiding accidental back-overs), antilock brakes (to maintain control during panicked braking), traction control (improves stability during acceleration), electronic stability control (foils spinouts), tire-pressure-monitoring systems (avoids blowouts), daytime running lights (ensures others see you), rollover airbags (they stay inflated to keep you in the car), lane-departure warning (alerts you if you stray from your lane), and doors that automatically lock after the car starts (again, falling out of cars).

For all the negative press of late, car manufacturers understand safety.

A System Not So Safe

Contrast this to healthcare, in which 10% of patients will suffer a serious, preventable, adverse event during their hospital stay.1 Read that sentence again. That’s 10%; that’s preventable; that’s a number that has largely remained unchanged in the past decade. If 1 in 10 drivers suffered a serious adverse preventable auto accident, Congress would do nothing but hold automotive safety hearings.

In medicine, we still largely employ unsafe systems in which even the best doctors can, and do, hurt patients. Sure, we have made strides in this arena (oxygen tubing that only works if hooked up properly, smart pumps that avert IV dosing errors, CO2 monitors to detect proper endotracheal tube placement), but remarkably, in this era of patient safety, we still utilize systems that largely depend on the heroism of the individual.

As physicians, we are famously autonomous and value our professional independence, even to the degree that it might harm patients. We generally eschew standardization, believing that each patient is inherently different. In fact, the thrill of the improvisational theater that follows every patient’s chief compliant is one of the great satisfiers in medicine. We love that feeling that comes from sleuthing each case, deftly enacting a plan of action to shepherd the patient to health.

To suggest following protocols, guidelines, and checklists is derisively dismissed as “cookbook medicine.” To work in teams in which certain tasks are delegated to others is seen as weakness—we don’t need a system that utilizes a pharmacist; rather, we should know the doses of all medicines, their interactions, and the effect of renal and liver impairment on their clearance. To suggest otherwise is an insult to our Oslerian roots. To examine our errors, our system breakdowns, our patient harms is anathema to our practice, an admission of failure.

The result is that most of us continue to toil in systems that have become exponentially unsafe as healthcare has become more complex. Today, we still have a system that will more or less allow us to kill a patient by doing nothing more than forgetting the letter “g.” I can go to my hospital today and intend to write “4 grams of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4)” and inadvertently forget the “g” in “Mg.” This could result in an order for a lethal dose of morphine sulfate (MSO4). It’s that easy to hurt a patient. Now, you might say that would never happen, because the pharmacy would catch it. And this is likely. But is it guaranteed? Can you 100% ensure it wouldn’t happen? Consider that nearly 20% of medication doses administered in a hospital are done so incorrectly.2 Nearly 1 in 5. This is the type of system we are employing to stop this lethal overdose. Is this system, which depends on another human to prevent an error, foolproof, or just a snare waiting to prove you the fool?

This represents our opportunity. As hospitalists, the hospital is our tapestry, our system of care, our responsibility. Few others are as well-positioned to ensure that the systems that envelop our patients are highly functional, reliable, and safe. This will take work—work that will feel burdensome, underappreciated, undercompensated. And, fully recognizing that none of us went into medicine to become systems engineers, this will be hard.

However, if not us, who? Who will ensure that our fathers, our mothers, our children will be as safe in the hospital as they are on the drive to the hospital? TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

References

- Global health leaders join the World Health Organization to announce accelerated efforts to improve patient safety. World Health Organization website. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr74/en/. Accessed Feb. 14, 2011.

- Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1897-1903.

I recently visited my parents in my ancestral home of Wisconsin. As parents of a certain age, they inexplicably are genetically predisposed to owning a minivan. Another quirk of their DNA is that they must own a new minivan. No sooner has the last wisp of new-car smell osmosed from the burled walnut interior than they are trading up to the newest, tricked-out minivan. Perhaps more puzzling is the manner of pride they display in their minivan.

Now, my dad, as if not readily apparent, is not cool. And to see him folded into the driver’s seat, his furry-ear-to-furry-ear grin signaling a self-satisfaction customarily reserved for his grandchildren, painstakingly recounting glory-day stories and 4:30 p.m. dinner buffets, further solidifies his place in the Annals of Uncool.

When I’m home, they tend to employ my chauffeur services (most likely in retribution for my peri-pubescent years), and on the first day back home, I stopped their newest ride near the back door of the house, foot idling on the brake while this exchange occurred: “That’s a fascinating story about how much more challenging the world was when you were my age, Dad. You are a true American hero. Would you like to get out here or in the garage?”

“Here,” he replied.

“OK, then get out,” I countered.

“I can’t,” he responded knowingly.

“Why not?” I queried, the patience seeping from my voice.

“Because the door’s not open,” he answered, seemingly mocking me.

“Then open it,” I replied, silently recounting the evidence for his institutionalization.

“I can’t,” he responded.

“Why not?” I replied again, this time calculating the likelihood that I was adopted.

“Because it’s locked,” came his retort.

“Then unlock it,” I answered, reconfirming my decision to move away for college.

“I can’t,” he replied, ostensibly encouraging parenticide.

“Why not?” I queried, strongly contemplating parenticide.

“Because you haven’t put the car in park,” he responded triumphantly.

A System So Safe

As a safety feature, the minivan needed to be in park before you could open the door to exit. I’ve never heard of anyone actually falling out of a moving car, but recollecting high school, I can fathom the right mix, type, and number of teenagers where possibility would meet inevitability. But, apparently, enough people are falling out of moving vehicles that car engineers have built a system that is so safe, this can’t happen. So no matter how hard someone tries, it just isn’t possible to fall out of a moving car (believe me, toward the end of a week of my father’s car stories, my mind had worked every possible angle).

Likewise, newer vehicles employ occupant-sensitive sensors that detect the weight, size, and position of the passenger to determine if the airbag should deploy. Rather than depending on the driver to turn the passenger-side airbag on or off, the car does it for you: heavy enough to trigger the sensor, and the airbag will deploy; too light, and the car assumes you are a child and doesn’t deploy. It’s a system that is so safe because it doesn’t depend on the operator to get it right.

Ditto motion sensors that detect objects behind the car while reversing (avoiding accidental back-overs), antilock brakes (to maintain control during panicked braking), traction control (improves stability during acceleration), electronic stability control (foils spinouts), tire-pressure-monitoring systems (avoids blowouts), daytime running lights (ensures others see you), rollover airbags (they stay inflated to keep you in the car), lane-departure warning (alerts you if you stray from your lane), and doors that automatically lock after the car starts (again, falling out of cars).

For all the negative press of late, car manufacturers understand safety.

A System Not So Safe

Contrast this to healthcare, in which 10% of patients will suffer a serious, preventable, adverse event during their hospital stay.1 Read that sentence again. That’s 10%; that’s preventable; that’s a number that has largely remained unchanged in the past decade. If 1 in 10 drivers suffered a serious adverse preventable auto accident, Congress would do nothing but hold automotive safety hearings.

In medicine, we still largely employ unsafe systems in which even the best doctors can, and do, hurt patients. Sure, we have made strides in this arena (oxygen tubing that only works if hooked up properly, smart pumps that avert IV dosing errors, CO2 monitors to detect proper endotracheal tube placement), but remarkably, in this era of patient safety, we still utilize systems that largely depend on the heroism of the individual.

As physicians, we are famously autonomous and value our professional independence, even to the degree that it might harm patients. We generally eschew standardization, believing that each patient is inherently different. In fact, the thrill of the improvisational theater that follows every patient’s chief compliant is one of the great satisfiers in medicine. We love that feeling that comes from sleuthing each case, deftly enacting a plan of action to shepherd the patient to health.

To suggest following protocols, guidelines, and checklists is derisively dismissed as “cookbook medicine.” To work in teams in which certain tasks are delegated to others is seen as weakness—we don’t need a system that utilizes a pharmacist; rather, we should know the doses of all medicines, their interactions, and the effect of renal and liver impairment on their clearance. To suggest otherwise is an insult to our Oslerian roots. To examine our errors, our system breakdowns, our patient harms is anathema to our practice, an admission of failure.

The result is that most of us continue to toil in systems that have become exponentially unsafe as healthcare has become more complex. Today, we still have a system that will more or less allow us to kill a patient by doing nothing more than forgetting the letter “g.” I can go to my hospital today and intend to write “4 grams of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4)” and inadvertently forget the “g” in “Mg.” This could result in an order for a lethal dose of morphine sulfate (MSO4). It’s that easy to hurt a patient. Now, you might say that would never happen, because the pharmacy would catch it. And this is likely. But is it guaranteed? Can you 100% ensure it wouldn’t happen? Consider that nearly 20% of medication doses administered in a hospital are done so incorrectly.2 Nearly 1 in 5. This is the type of system we are employing to stop this lethal overdose. Is this system, which depends on another human to prevent an error, foolproof, or just a snare waiting to prove you the fool?

This represents our opportunity. As hospitalists, the hospital is our tapestry, our system of care, our responsibility. Few others are as well-positioned to ensure that the systems that envelop our patients are highly functional, reliable, and safe. This will take work—work that will feel burdensome, underappreciated, undercompensated. And, fully recognizing that none of us went into medicine to become systems engineers, this will be hard.

However, if not us, who? Who will ensure that our fathers, our mothers, our children will be as safe in the hospital as they are on the drive to the hospital? TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

References

- Global health leaders join the World Health Organization to announce accelerated efforts to improve patient safety. World Health Organization website. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr74/en/. Accessed Feb. 14, 2011.

- Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1897-1903.

I recently visited my parents in my ancestral home of Wisconsin. As parents of a certain age, they inexplicably are genetically predisposed to owning a minivan. Another quirk of their DNA is that they must own a new minivan. No sooner has the last wisp of new-car smell osmosed from the burled walnut interior than they are trading up to the newest, tricked-out minivan. Perhaps more puzzling is the manner of pride they display in their minivan.

Now, my dad, as if not readily apparent, is not cool. And to see him folded into the driver’s seat, his furry-ear-to-furry-ear grin signaling a self-satisfaction customarily reserved for his grandchildren, painstakingly recounting glory-day stories and 4:30 p.m. dinner buffets, further solidifies his place in the Annals of Uncool.

When I’m home, they tend to employ my chauffeur services (most likely in retribution for my peri-pubescent years), and on the first day back home, I stopped their newest ride near the back door of the house, foot idling on the brake while this exchange occurred: “That’s a fascinating story about how much more challenging the world was when you were my age, Dad. You are a true American hero. Would you like to get out here or in the garage?”

“Here,” he replied.

“OK, then get out,” I countered.

“I can’t,” he responded knowingly.

“Why not?” I queried, the patience seeping from my voice.

“Because the door’s not open,” he answered, seemingly mocking me.

“Then open it,” I replied, silently recounting the evidence for his institutionalization.

“I can’t,” he responded.

“Why not?” I replied again, this time calculating the likelihood that I was adopted.

“Because it’s locked,” came his retort.

“Then unlock it,” I answered, reconfirming my decision to move away for college.

“I can’t,” he replied, ostensibly encouraging parenticide.

“Why not?” I queried, strongly contemplating parenticide.

“Because you haven’t put the car in park,” he responded triumphantly.

A System So Safe

As a safety feature, the minivan needed to be in park before you could open the door to exit. I’ve never heard of anyone actually falling out of a moving car, but recollecting high school, I can fathom the right mix, type, and number of teenagers where possibility would meet inevitability. But, apparently, enough people are falling out of moving vehicles that car engineers have built a system that is so safe, this can’t happen. So no matter how hard someone tries, it just isn’t possible to fall out of a moving car (believe me, toward the end of a week of my father’s car stories, my mind had worked every possible angle).

Likewise, newer vehicles employ occupant-sensitive sensors that detect the weight, size, and position of the passenger to determine if the airbag should deploy. Rather than depending on the driver to turn the passenger-side airbag on or off, the car does it for you: heavy enough to trigger the sensor, and the airbag will deploy; too light, and the car assumes you are a child and doesn’t deploy. It’s a system that is so safe because it doesn’t depend on the operator to get it right.

Ditto motion sensors that detect objects behind the car while reversing (avoiding accidental back-overs), antilock brakes (to maintain control during panicked braking), traction control (improves stability during acceleration), electronic stability control (foils spinouts), tire-pressure-monitoring systems (avoids blowouts), daytime running lights (ensures others see you), rollover airbags (they stay inflated to keep you in the car), lane-departure warning (alerts you if you stray from your lane), and doors that automatically lock after the car starts (again, falling out of cars).

For all the negative press of late, car manufacturers understand safety.

A System Not So Safe

Contrast this to healthcare, in which 10% of patients will suffer a serious, preventable, adverse event during their hospital stay.1 Read that sentence again. That’s 10%; that’s preventable; that’s a number that has largely remained unchanged in the past decade. If 1 in 10 drivers suffered a serious adverse preventable auto accident, Congress would do nothing but hold automotive safety hearings.

In medicine, we still largely employ unsafe systems in which even the best doctors can, and do, hurt patients. Sure, we have made strides in this arena (oxygen tubing that only works if hooked up properly, smart pumps that avert IV dosing errors, CO2 monitors to detect proper endotracheal tube placement), but remarkably, in this era of patient safety, we still utilize systems that largely depend on the heroism of the individual.

As physicians, we are famously autonomous and value our professional independence, even to the degree that it might harm patients. We generally eschew standardization, believing that each patient is inherently different. In fact, the thrill of the improvisational theater that follows every patient’s chief compliant is one of the great satisfiers in medicine. We love that feeling that comes from sleuthing each case, deftly enacting a plan of action to shepherd the patient to health.

To suggest following protocols, guidelines, and checklists is derisively dismissed as “cookbook medicine.” To work in teams in which certain tasks are delegated to others is seen as weakness—we don’t need a system that utilizes a pharmacist; rather, we should know the doses of all medicines, their interactions, and the effect of renal and liver impairment on their clearance. To suggest otherwise is an insult to our Oslerian roots. To examine our errors, our system breakdowns, our patient harms is anathema to our practice, an admission of failure.

The result is that most of us continue to toil in systems that have become exponentially unsafe as healthcare has become more complex. Today, we still have a system that will more or less allow us to kill a patient by doing nothing more than forgetting the letter “g.” I can go to my hospital today and intend to write “4 grams of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4)” and inadvertently forget the “g” in “Mg.” This could result in an order for a lethal dose of morphine sulfate (MSO4). It’s that easy to hurt a patient. Now, you might say that would never happen, because the pharmacy would catch it. And this is likely. But is it guaranteed? Can you 100% ensure it wouldn’t happen? Consider that nearly 20% of medication doses administered in a hospital are done so incorrectly.2 Nearly 1 in 5. This is the type of system we are employing to stop this lethal overdose. Is this system, which depends on another human to prevent an error, foolproof, or just a snare waiting to prove you the fool?

This represents our opportunity. As hospitalists, the hospital is our tapestry, our system of care, our responsibility. Few others are as well-positioned to ensure that the systems that envelop our patients are highly functional, reliable, and safe. This will take work—work that will feel burdensome, underappreciated, undercompensated. And, fully recognizing that none of us went into medicine to become systems engineers, this will be hard.

However, if not us, who? Who will ensure that our fathers, our mothers, our children will be as safe in the hospital as they are on the drive to the hospital? TH

Dr. Glasheen is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

References

- Global health leaders join the World Health Organization to announce accelerated efforts to improve patient safety. World Health Organization website. Available at: www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr74/en/. Accessed Feb. 14, 2011.

- Barker KN, Flynn EA, Pepper GA, Bates DW, Mikeal RL. Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1897-1903.

Surgery’s Waterboys

The query came from the audience: “But isn’t comanagement really about us becoming the surgeon’s waterboy?” Encouraged by the chortling crowd, he furthered, “I mean, think about it: How much more demeaning can it get than to be the admit-ologist and discharge-ologist for the surgeon? They make all the coin and we just follow after them picking up their jock straps.”

Slack-jawed, I mustered what was, under the circumstances, a rather confident “Umm … ?”

This comment, from a talk I gave a couple of years ago at an SHM annual meeting about comanagement, took me a bit by surprise. Not because of the sentiment; that I get. It’s easy to feel that the comanagement we do suffices only to sate the surgeon at the hospitalist’s expense. Rather, I was taken aback because of its indication of the distance with which we’ve missed the comanagement bull’s-eye.

New Comanagement Data

A recent article regarding the comanagement of neurosurgical patients drudged this oratorical memory from its peaceful cerebral resting place between the 1982 Milwaukee Brewers’ starting outfield (Ogilvie, Thomas, Moore), my wife’s least favorite Beatle (Ringo), and the number of macaroni noodles my grade-school friend Mike could stuff into his nostril and cough up through his mouth (nine with aspiration, five without). In the paper, Auerbach et al report a retrospective, before-and-after study of 7,596 patients admitted to the neurosurgery service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center.1 The authors compared administrative, financial, and survey data for 4,203 patients before a hospitalist-neurosurgery comanagement arrangement to 3,393 patients after the program implementation—by far the largest trial of hospitalist comanagement to date.

They found:

- Shockingly, surgeons (“hospitalists make it easier for me to do my job”) and nurses (“I can easily and promptly reach a physician”) liked having us around.

- Curiously, patients were rather indifferent (measured via patient satisfaction indicators) to our presence.

- The cost of care decreased by about $1,500 per patient after the intercalation of hospitalists—this despite the fact that the length of stay was unchanged before and after model implementation.

- Unfortunately, such traditional markers of quality as mortality and readmission rate remained stubbornly unchanged.

- Encouragingly, nontraditional-but-likely-important indicators of quality (e.g. nursing and physician perception of improvements in care provision) were achieved.

Perspective

This study adds significantly to our understanding of the comanagement model. The finding of costs savings is as expected (nearly all studies of hospitalist programs have shown cost savings) as it is unexpected (prior studies of comanagement models reported no cost savings).2 Likewise, the lack of improvement of hard quality endpoints (mortality and readmission rates) is consistent with most studies of hospitalist programs, including a previous report of comanagement of orthopedic patients that showed improvements only in minor complications, such as rates of electrolyte abnormalities, while improvement in the softer quality endpoints—nursing and surgeon satisfaction and perceptions of quality—is consistent with most reports and conventional wisdom.2

Within hours of publication, the blogs were throbbing with discussion of what this meant for the field of hospital medicine. Did this prove comanagement to be the godsend many believe (perceptions of improved quality), the complete farce that many believe (no evidence of mortality benefit), or was this just further confirmation that hospitalists are really nothing more than cost reduction-ists?

My opinion? This is just the comanagement MacGuffin.

MacGuffin Explained

Fans of film will know that the MacGuffin is a Hitchcockian plot device that uses a meaningless but often mysterious and intriguing element to drive the plot. So while everyone, it seems, is concerned with the MacGuffin, the MacGuffin exists only to help the story unfold. Think of the “government secrets” driving the plot in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest, or “unobtainium” in the movie Avatar. In both cases, the MacGuffin preoccupied the cast (they had to have it, or defend it), but in the end, the MacGuffin was insignificant except to move the plot forward.

In much the same way, the debate about whether the shared-care model of surgical patients is a good thing is comanagment’s MacGuffin; it definitely drives the plot but ultimately it misses the point. The real comanagement story—indeed, the story of the whole of hospital medicine—is our need to fundamentally improve outcomes through systems improvements. The true benefit of comanagement is not in one doctor (hospitalist) taking over the medical care of another doctor (surgeon). That will only slightly improve outcomes of the medical issues at which the hospitalist is more expert (e.g. minor electrolyte disorders). Meanwhile, this model continues to allow the same harms that the underlying unsafe hospital system imparts. The comanagement model itself won’t fix this. Rather, the model simply acts as a mechanism for us to accomplish our desired goals of system redesign.

Put another way, I am better at internal-medicine care than a neurosurgeon is. As such, I have no doubt that if I manage the medical issues of neurosurgical patients, I will do it better. However, this system of hospitalist provision of internal-medicine care can ultimately only lead to the type of marginal, not meaningful, improvements these comanagement studies have shown.

The real potential for the comanagement model comes when I take off my internal-medicine hat (diabetes care, electrolyte management, etc.) and put on my HM hat (ability to execute systematic quality and process improvements that result in safer systems that effect ALL patients, ALL the time, and is not dependent on the individual provider to do the right thing).

In doing this, the MacGuffin—the comanagement model that cohorts a lot of patients in the hands of a relatively few hospitalists—affords us the opportunity to truly advance the patient-safety plot by building better systems, the type of systems that ensure that every patient systematically gets appropriate VTE prophylaxis, avoids medication errors, has unnecessary urinary and central venous catheters removed, avoids pressure ulcers, doesn’t fall or get delirious, and has expert transitions of care. I have no doubt that if we achieved these kinds of interventions, rather than just managing patients’ medical issues, we’d see the kind of profound changes the comanagement model can offer.

MacGuffin or not, comanagement is likely here to stay. The challenge, then, is to find a way in which these care arrangements can go beyond scut to systematically and comprehensively improve the flawed systems of care that envelop our surgical patients.

Doing this will vastly improve patient outcomes, add significant value to the care we provide, and clearly signal to the surgeon that it’s time to bring us the water bottle. TH

Dr. Glasheen is physician editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Denver, where he serves as director of the Hospital Medicine Program and the Hospitalist Training Program, and as associate program director of the Internal Medicine Residency Program.

References

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Cheng HQ, et al. Comanagement of surgical patients between neurosurgeons and hospitalists. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):2004-2010.

- Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(1):28-38.

The query came from the audience: “But isn’t comanagement really about us becoming the surgeon’s waterboy?” Encouraged by the chortling crowd, he furthered, “I mean, think about it: How much more demeaning can it get than to be the admit-ologist and discharge-ologist for the surgeon? They make all the coin and we just follow after them picking up their jock straps.”

Slack-jawed, I mustered what was, under the circumstances, a rather confident “Umm … ?”

This comment, from a talk I gave a couple of years ago at an SHM annual meeting about comanagement, took me a bit by surprise. Not because of the sentiment; that I get. It’s easy to feel that the comanagement we do suffices only to sate the surgeon at the hospitalist’s expense. Rather, I was taken aback because of its indication of the distance with which we’ve missed the comanagement bull’s-eye.

New Comanagement Data

A recent article regarding the comanagement of neurosurgical patients drudged this oratorical memory from its peaceful cerebral resting place between the 1982 Milwaukee Brewers’ starting outfield (Ogilvie, Thomas, Moore), my wife’s least favorite Beatle (Ringo), and the number of macaroni noodles my grade-school friend Mike could stuff into his nostril and cough up through his mouth (nine with aspiration, five without). In the paper, Auerbach et al report a retrospective, before-and-after study of 7,596 patients admitted to the neurosurgery service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center.1 The authors compared administrative, financial, and survey data for 4,203 patients before a hospitalist-neurosurgery comanagement arrangement to 3,393 patients after the program implementation—by far the largest trial of hospitalist comanagement to date.

They found:

- Shockingly, surgeons (“hospitalists make it easier for me to do my job”) and nurses (“I can easily and promptly reach a physician”) liked having us around.

- Curiously, patients were rather indifferent (measured via patient satisfaction indicators) to our presence.

- The cost of care decreased by about $1,500 per patient after the intercalation of hospitalists—this despite the fact that the length of stay was unchanged before and after model implementation.

- Unfortunately, such traditional markers of quality as mortality and readmission rate remained stubbornly unchanged.

- Encouragingly, nontraditional-but-likely-important indicators of quality (e.g. nursing and physician perception of improvements in care provision) were achieved.

Perspective

This study adds significantly to our understanding of the comanagement model. The finding of costs savings is as expected (nearly all studies of hospitalist programs have shown cost savings) as it is unexpected (prior studies of comanagement models reported no cost savings).2 Likewise, the lack of improvement of hard quality endpoints (mortality and readmission rates) is consistent with most studies of hospitalist programs, including a previous report of comanagement of orthopedic patients that showed improvements only in minor complications, such as rates of electrolyte abnormalities, while improvement in the softer quality endpoints—nursing and surgeon satisfaction and perceptions of quality—is consistent with most reports and conventional wisdom.2