User login

What Is the Best Therapy for Acute Hepatic Encephalopathy?

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

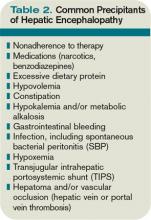

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

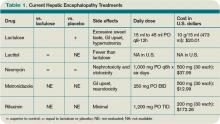

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.

Case

A 56-year-old man with a history of cirrhosis, complicated by esophageal varices and ongoing alcohol abuse, is admitted after his wife found him lethargic and disoriented in bed. His wife said he’d been increasingly irritable and agitated, with slurred speech, the past two days. On exam, he is somnolent but arousable; spider telangiectasias and asterixis are noted. Laboratory studies are consistent with chronic liver disease.

What is the best therapy for his acute hepatic encephalopathy?

Overview

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) describes the spectrum of potentially reversible neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction. The wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations led to the development of consensus HE classification terminology by the World Congress of Gastroenterology in 2002.

The primary tenet of all HE pathogenesis theories is firmly established: Nitrogenous substances derived from the gut adversely affect brain function. These compounds access the systemic circulation via decreased hepatic function or portal-systemic shunts. In the brain, they alter neurotransmission, which affects consciousness and behavior.

HE patients usually have advanced cirrhosis and, hence, many of the physical findings associated with severe hepatic dysfunction: muscle-wasting, jaundice, ascites, palmar erythema, edema, spider telangiectasias, and fetor hepaticus. Encephalopathy progresses from reversal of the sleep-wake cycle and mild mental status changes to irritability, confusion, and slurred speech.

Advanced neurologic features include asterixis or tongue fasciculations, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, and ultimately coma. History and laboratory data can reveal a precipitating cause (see Table 2, p. 19). Measurement of ammonia concentration remains controversial. The value may be useful for monitoring the efficacy of ammonia-lowering therapy, but elevated levels are not required to make the diagnosis.

Multiple treatments have been used to manage HE, yet few well-designed randomized trials have assessed efficacy due to challenges inherent in measuring the wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations. Nonetheless, a critical appraisal of available data delineates a rational approach to therapy.

Review of the Data

In addition to supportive care and the reversal of any precipitating factors, the treatment of acute HE is aimed at reducing or inhibiting intestinal ammonia production or increasing its removal (see Table 1, left).

Nonabsorbable disaccharides (NAD): Lactulose (beta-galactosidofructose) and lactitol (beta-galactosidosorbitol) are used as first-line agents for the treatment of HE and lead to symptomatic improvement in 67% to 87% of patients.1 They reduce the concentration of ammoniogenic substrates in the colonic lumen in two ways—first, by facilitating bacterial fermentation and secondary organic acid production (lowering colonic pH) and, second, by direct osmotic catharsis.

NAD are administered orally or via nasogastric tube at an initial dose of 45 ml, followed by repeated hourly doses until the patient has a bowel movement. For patients at risk of aspiration, NAD can be administered via enema (300 ml in 700 ml of water) every two hours as needed until mental function improves. Once the risk of aspiration is minimized, NAD can be administered orally and titrated to achieve two to three soft bowel movements daily (the usual oral dosage is 15 ml to 45 ml every eight to 12 hours).

Common side effects of NAD include an excessively sweet taste, flatulence, abdominal cramping, and electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypernatremia, which may further deteriorate mental status.

Als-Nielsen et al demonstrated in a systematic review that NAD were more effective than placebo in improving HE, but NAD had no significant benefit on mortality.1 However, the effect on HE no longer reached statistical significance when the analysis was confined to studies with the highest methodological quality. In a randomized, double-blind comparison, Morgan et al showed that lactitol was more tolerable than lactulose and produced fewer side effects.2 Lactitol is not currently available for use in the U.S.

Antibiotics: Certain oral antibiotics (e.g., neomycin, rifaximin, and metronidazole) reduce urease-producing intestinal bacteria, which results in decreased ammonia production and absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. Antibiotics generally are used in patients who do not tolerate NAD or who remain symptomatic despite NAD. The combined use of NAD and antibiotics is a subject of significant clinical relevance, though data are limited.

Neomycin is approved by the FDA for treatment of acute HE. It can be administered orally at a dose of 1,000 mg every six hours for up to six days. A randomized, controlled trial of neomycin versus placebo in 39 patients with acute HE demonstrated no significant difference in time to symptom improvement.3 Another study of 80 patients receiving neomycin and lactulose demonstrated no benefit against placebo, though some data suggest that the combination of lactulose and neomycin therapy might be more effective than either agent alone against placebo.4

Rifaximin was granted an orphan drug designation by the FDA for use in HE cases and has been compared with NAD. The recommended dose is 1,200 mg three times per day. It has minimal side effects and no reported drug interactions. A study of rifaximin versus lactitol administered for five to 10 days showed approximately 80% symptomatic improvement in both groups.5 Another trial demonstrated significantly greater improvement in blood ammonia concentrations, electroencephalographic (EEG) abnormalities, and mental status with rifaximin compared with lactulose.6 Studies comparing rifaximin and lactulose, either alone or in combination, have demonstrated that rifaximin is at least similar to lactulose, and in some cases superior in reversing encephalopathy, with better tolerability reported in the antibiotic group.7

Metronidazole is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of HE but has been evaluated. The recommended oral dose of metronidazole for chronic use is 250 mg twice per day. Prolonged administration of metronidazole can be associated with gastrointestinal disturbance and neurotoxicity. In a report of 11 HE patients with mild to moderate symptoms and seven chronically affected HE cirrhotic patients treated with metronidazole for one week, Morgan and colleagues showed metronidazole to be as effective as neomycin.8

Diet: Historically, patients with HE were placed on protein-restricted diets to reduce the production of intestinal ammonia. Recent evidence suggests that excessive restriction can raise serum ammonia levels as a result of reduced muscular ammonia metabolism. Furthermore, restricting protein intake worsens nutritional status and does not improve the outcome.9

In patients with established cirrhosis, the minimal daily dietary protein intake required to maintain nitrogen balance is 0.8 g/kg to 1.0 g/kg. At this time, a normoprotein diet for HE patients is considered the standard of care.

Other agents: L-ornithine L-aspartate (LOLA), a stable salt of ornithine and aspartic acid, provides crucial substrates for glutamine and urea synthesis—key pathways in deammonation. In patients with cirrhosis and HE, oral LOLA reduces serum ammonia and improves clinical manifestations of HE, including EEG abnormalities.10 LOLA, however, is not available in the U.S.

Sodium benzoate might be beneficial in the treatment of acute HE; it increases urinary excretion of ammonia. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 74 patients with acute HE found that treatment with sodium benzoate 5 g twice daily, compared with lactulose, resulted in equivalent improvements in encephalopathy. There was no placebo group.11 Routine use has been limited due to concerns regarding sodium load and increased frequency of adverse gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly nausea.

Flumazenil, a short-acting benzodiazepine receptor antagonist, has been utilized on the basis of observed increases in benzodiazepine receptor activation among cirrhotic HE patients. In a systematic review of 12 controlled trials (765 patients), Als-Nielsen and colleagues found flumazenil to be associated with significant improvement.12 Flumazenil is not used routinely as an HE therapy because of significant side effects, namely seizures, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and agitation.

Such therapies as L-carnitine, branched amino acids (BCAA), probiotics, bromocriptine, acarbose, and zinc are among the many experimental agents currently under evaluation. Few have been tested in clinical trials.

Back to the Case

Our patient has severe HE manifested by worsening somnolence. It is postulated that ongoing alcohol abuse led to medication nonadherence, precipitating his HE, but as HE has many causes, a complete workup for infection and metabolic derangement is performed. However, it is unrevealing.

The best initial action is the prescription of lactulose, the mainstay of HE therapy. Given concern for aspiration in patients with somnolence, a feeding tube is placed for administration. The lactulose dosage will be titrated to achieve two to three soft stools per day. If the patient remains symptomatic or develops significant side effects on lactulose, the addition of an antibiotic is recommended. Neomycin, a low-cost medicine approved by the FDA for HE treatment, is a good choice. The patient will be maintained on a normal protein diet.

Bottom Line

The first-line agents used to treat episodes of acute HE are the nonabsorbable disaccharides, lactulose or lactitol. TH

Dr. Shoeb is a resident in the Department of Medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle. Dr. Best is assistant professor of medicine in the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Washington.

References

- Als-Nielsen B, Gluud L, Gluud C. Nonabsorbable disaccharides for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003044.

- Morgan MY, Hawley KE. Lactitol v. lactulose in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients: a double-blind, randomized trial. Hepatology. 1987; 7(6):1278-1284.

- Blanc P, Daurès JP, Liautard J, et al. Lactulose-neomycin combination versus placebo in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18(12):1063-1068.

- Mas A, Rodés J, Sunyer L, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactitol in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, controlled clinical trial. J Hepatol. 2003;38(1):51-58.

- Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, et al. Comparison of rifaximin and lactulose for the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a prospective randomized study. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46(3):399-407.

- Massa P, Vallerino E, Dodero M. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with rifaximin: double blind, double dummy study versus lactulose. Eur J Clin Res. 1993;4:7-18.

- Williams R, James OF, Warnes TW, Morgan MY. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rifaximin in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind, randomized, dose-finding multi-centre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):203-208.

- Morgan MH, Read AE, Speller DC. Treatment of hepatic encephalopathy with metronidazole. Gut. 1982;23(1):1-7.

- Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, et al. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):38-43.

- Poo JL, Gongora J, Sánchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy. Results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol. 2006;5(4):281-288.

- Sushma S, Dasarathy S, Tandon RK, Jain S, Gupta S, Bhist MS. Sodium benzoate in the treatment of acute hepatic encephalopathy: a double-blind randomized trial. Hepatology. 1992;16(16):138-144.

- Als-Nielsen B, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Benzodiazepine receptor antagonists for acute and chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;4:CD002798.