User login

Compounded Semaglutide: How to Better Ensure Its Safety

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic and Rybelsus for type 2 diabetes and as Wegovy for obesity) slow down digestion and curb hunger by working on the brain’s dopamine reward center. They are prescribed to promote weight loss, metabolic health in type 2 diabetes, and heart health in coronary artery disease.

Semaglutide can be prescribed in two forms: the brand-name version, which is approved and confirmed as safe and effective by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the versions that can be obtained from a compounding pharmacy. Compounding pharmacies are permitted by the FDA to produce what is “ essentially a copy” of approved medications when there’s an official shortage, which is currently the case with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Patients are often drawn to compounding pharmacies for pricing-related reasons. If semaglutide is prescribed for a clear indication like diabetes and is covered by insurance, the brand-name version is commonly dispensed. However, if it’s not covered, patients need to pay out of pocket for branded versions, which carry a monthly cost of $1000 or more. Alternatively, their doctors can prescribe compounded semaglutide, which some telehealth companies advertise at costs of approximately $150-$300 per month.

Potential Issues With Compounded Semaglutide

Compounding pharmacies produce drugs from raw materials containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Although compounders use many of the same ingredients found in brand-name medications, for drugs like semaglutide, they may opt for specific salts that are not identical to those involved in the production of the standard versions. These salts are typically reserved for research purposes and may not be suitable for general use.

In late 2023, the FDA issued a letter asking the public to exercise caution when using compounded products containing semaglutide or semaglutide salts. This was followed in January 2024 by an FDA communication citing adverse events reported with the use of compounded semaglutide and advising patients to avoid these versions if an approved form of the drug is available.

Compound Pharmacies: A Closer Look

Compounding pharmacies have exploded in popularity in the past several decades. The compounding pharmacy market is expected to grow at 7.8% per year over the next decade.

Historically, compounding pharmacies have filled a niche for specialty vitamins for intravenous administration as well as chemotherapy medications. They also offer controlled substances, such as ketamine lozenges and nasal sprays, which are unavailable or are in short supply from traditional manufacturers.

Compounding pharmacies fall into two categories. First are compounding pharmacies covered under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act; these drugs are neither tested nor monitored. Such facilities do not have to report adverse events to the FDA. The second category is Section 503B outsourcing facilities. These pharmacies choose to be tested by, to be inspected by, and to report adverse events to the FDA.

The FDA’s Latest Update on This Issue

This news organization contacted the FDA for an update on the adverse events reported about compounded semaglutide. From August 8, 2021, to March 31, 2024, they received more than 20,000 adverse events reports for FDA-approved semaglutide. Comparatively, there were 210 adverse events reported on compounded semaglutide products.

The FDA went on to describe that many of the adverse events reported were consistent with known reactions in the labeling, like nausea, diarrhea, and headache. Yet, they added that, “the FDA is unable to determine how, or if, other factors may have contributed to these adverse events, such as differences in ingredients and formulation between FDA-approved and compounded semaglutide products.” They also noted there was variation in the data quality in the reports they have received, which came only from 503B compounding pharmacies.

In conclusion, given the concerns about compounded semaglutide, it is prudent for the prescribing physicians as well as the patients taking the medication to know that risks are “higher” according to the FDA. We eagerly await more specific information from the FDA to better understand reported adverse events.

How to Help Patients Receive Safe Compounded Semaglutide

For clinicians considering prescribing semaglutide from compounding pharmacies, there are several questions worth asking, according to the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding. First, find out whether the pharmacy complies with United States Pharmacopeia compounding standards and whether they source their APIs from FDA-registered facilities, the latter being required by federal law. It’s also important to ensure that these facilities undergo periodic third-party testing to verify medication purity and dosing.

Ask whether the pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation from the PCAB means that pharmacies have been assessed for processes related to continuous quality improvement. In addition, ask whether the pharmacy is designated as a 503B compounder and if not, why.

Finally, interviewing the pharmacist themselves can provide useful information about staffing, training, and their methods of preparing medications. For example, if they are preparing a sterile eye drop, it is important to ask about sterility testing.

Jesse M. Pines, MD, MBA, MSCE, is a clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, and a professor in the department of emergency medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Pines is also the chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. Dr. Pines reported conflicts of interest with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic and Rybelsus for type 2 diabetes and as Wegovy for obesity) slow down digestion and curb hunger by working on the brain’s dopamine reward center. They are prescribed to promote weight loss, metabolic health in type 2 diabetes, and heart health in coronary artery disease.

Semaglutide can be prescribed in two forms: the brand-name version, which is approved and confirmed as safe and effective by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the versions that can be obtained from a compounding pharmacy. Compounding pharmacies are permitted by the FDA to produce what is “ essentially a copy” of approved medications when there’s an official shortage, which is currently the case with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Patients are often drawn to compounding pharmacies for pricing-related reasons. If semaglutide is prescribed for a clear indication like diabetes and is covered by insurance, the brand-name version is commonly dispensed. However, if it’s not covered, patients need to pay out of pocket for branded versions, which carry a monthly cost of $1000 or more. Alternatively, their doctors can prescribe compounded semaglutide, which some telehealth companies advertise at costs of approximately $150-$300 per month.

Potential Issues With Compounded Semaglutide

Compounding pharmacies produce drugs from raw materials containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Although compounders use many of the same ingredients found in brand-name medications, for drugs like semaglutide, they may opt for specific salts that are not identical to those involved in the production of the standard versions. These salts are typically reserved for research purposes and may not be suitable for general use.

In late 2023, the FDA issued a letter asking the public to exercise caution when using compounded products containing semaglutide or semaglutide salts. This was followed in January 2024 by an FDA communication citing adverse events reported with the use of compounded semaglutide and advising patients to avoid these versions if an approved form of the drug is available.

Compound Pharmacies: A Closer Look

Compounding pharmacies have exploded in popularity in the past several decades. The compounding pharmacy market is expected to grow at 7.8% per year over the next decade.

Historically, compounding pharmacies have filled a niche for specialty vitamins for intravenous administration as well as chemotherapy medications. They also offer controlled substances, such as ketamine lozenges and nasal sprays, which are unavailable or are in short supply from traditional manufacturers.

Compounding pharmacies fall into two categories. First are compounding pharmacies covered under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act; these drugs are neither tested nor monitored. Such facilities do not have to report adverse events to the FDA. The second category is Section 503B outsourcing facilities. These pharmacies choose to be tested by, to be inspected by, and to report adverse events to the FDA.

The FDA’s Latest Update on This Issue

This news organization contacted the FDA for an update on the adverse events reported about compounded semaglutide. From August 8, 2021, to March 31, 2024, they received more than 20,000 adverse events reports for FDA-approved semaglutide. Comparatively, there were 210 adverse events reported on compounded semaglutide products.

The FDA went on to describe that many of the adverse events reported were consistent with known reactions in the labeling, like nausea, diarrhea, and headache. Yet, they added that, “the FDA is unable to determine how, or if, other factors may have contributed to these adverse events, such as differences in ingredients and formulation between FDA-approved and compounded semaglutide products.” They also noted there was variation in the data quality in the reports they have received, which came only from 503B compounding pharmacies.

In conclusion, given the concerns about compounded semaglutide, it is prudent for the prescribing physicians as well as the patients taking the medication to know that risks are “higher” according to the FDA. We eagerly await more specific information from the FDA to better understand reported adverse events.

How to Help Patients Receive Safe Compounded Semaglutide

For clinicians considering prescribing semaglutide from compounding pharmacies, there are several questions worth asking, according to the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding. First, find out whether the pharmacy complies with United States Pharmacopeia compounding standards and whether they source their APIs from FDA-registered facilities, the latter being required by federal law. It’s also important to ensure that these facilities undergo periodic third-party testing to verify medication purity and dosing.

Ask whether the pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation from the PCAB means that pharmacies have been assessed for processes related to continuous quality improvement. In addition, ask whether the pharmacy is designated as a 503B compounder and if not, why.

Finally, interviewing the pharmacist themselves can provide useful information about staffing, training, and their methods of preparing medications. For example, if they are preparing a sterile eye drop, it is important to ask about sterility testing.

Jesse M. Pines, MD, MBA, MSCE, is a clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, and a professor in the department of emergency medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Pines is also the chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. Dr. Pines reported conflicts of interest with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists such as semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic and Rybelsus for type 2 diabetes and as Wegovy for obesity) slow down digestion and curb hunger by working on the brain’s dopamine reward center. They are prescribed to promote weight loss, metabolic health in type 2 diabetes, and heart health in coronary artery disease.

Semaglutide can be prescribed in two forms: the brand-name version, which is approved and confirmed as safe and effective by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the versions that can be obtained from a compounding pharmacy. Compounding pharmacies are permitted by the FDA to produce what is “ essentially a copy” of approved medications when there’s an official shortage, which is currently the case with semaglutide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists.

Patients are often drawn to compounding pharmacies for pricing-related reasons. If semaglutide is prescribed for a clear indication like diabetes and is covered by insurance, the brand-name version is commonly dispensed. However, if it’s not covered, patients need to pay out of pocket for branded versions, which carry a monthly cost of $1000 or more. Alternatively, their doctors can prescribe compounded semaglutide, which some telehealth companies advertise at costs of approximately $150-$300 per month.

Potential Issues With Compounded Semaglutide

Compounding pharmacies produce drugs from raw materials containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Although compounders use many of the same ingredients found in brand-name medications, for drugs like semaglutide, they may opt for specific salts that are not identical to those involved in the production of the standard versions. These salts are typically reserved for research purposes and may not be suitable for general use.

In late 2023, the FDA issued a letter asking the public to exercise caution when using compounded products containing semaglutide or semaglutide salts. This was followed in January 2024 by an FDA communication citing adverse events reported with the use of compounded semaglutide and advising patients to avoid these versions if an approved form of the drug is available.

Compound Pharmacies: A Closer Look

Compounding pharmacies have exploded in popularity in the past several decades. The compounding pharmacy market is expected to grow at 7.8% per year over the next decade.

Historically, compounding pharmacies have filled a niche for specialty vitamins for intravenous administration as well as chemotherapy medications. They also offer controlled substances, such as ketamine lozenges and nasal sprays, which are unavailable or are in short supply from traditional manufacturers.

Compounding pharmacies fall into two categories. First are compounding pharmacies covered under Section 503A of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act; these drugs are neither tested nor monitored. Such facilities do not have to report adverse events to the FDA. The second category is Section 503B outsourcing facilities. These pharmacies choose to be tested by, to be inspected by, and to report adverse events to the FDA.

The FDA’s Latest Update on This Issue

This news organization contacted the FDA for an update on the adverse events reported about compounded semaglutide. From August 8, 2021, to March 31, 2024, they received more than 20,000 adverse events reports for FDA-approved semaglutide. Comparatively, there were 210 adverse events reported on compounded semaglutide products.

The FDA went on to describe that many of the adverse events reported were consistent with known reactions in the labeling, like nausea, diarrhea, and headache. Yet, they added that, “the FDA is unable to determine how, or if, other factors may have contributed to these adverse events, such as differences in ingredients and formulation between FDA-approved and compounded semaglutide products.” They also noted there was variation in the data quality in the reports they have received, which came only from 503B compounding pharmacies.

In conclusion, given the concerns about compounded semaglutide, it is prudent for the prescribing physicians as well as the patients taking the medication to know that risks are “higher” according to the FDA. We eagerly await more specific information from the FDA to better understand reported adverse events.

How to Help Patients Receive Safe Compounded Semaglutide

For clinicians considering prescribing semaglutide from compounding pharmacies, there are several questions worth asking, according to the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding. First, find out whether the pharmacy complies with United States Pharmacopeia compounding standards and whether they source their APIs from FDA-registered facilities, the latter being required by federal law. It’s also important to ensure that these facilities undergo periodic third-party testing to verify medication purity and dosing.

Ask whether the pharmacy is accredited by the Pharmacy Compounding Accreditation Board (PCAB). Accreditation from the PCAB means that pharmacies have been assessed for processes related to continuous quality improvement. In addition, ask whether the pharmacy is designated as a 503B compounder and if not, why.

Finally, interviewing the pharmacist themselves can provide useful information about staffing, training, and their methods of preparing medications. For example, if they are preparing a sterile eye drop, it is important to ask about sterility testing.

Jesse M. Pines, MD, MBA, MSCE, is a clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, and a professor in the department of emergency medicine at Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dr. Pines is also the chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. Dr. Pines reported conflicts of interest with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Everyone Needs Their Own Emergency Medicine Doctor

How emerging models come close to making this reality

As emergency medicine doctors, we regularly give medical advice to family and close friends when they get sick or are injured and don’t know what to do. In a matter of moments, we triage, diagnose, and assemble a logical plan, whatever the issue may be. This skill comes from our training and years of experience in treating emergencies and also routine medical matters. The value proposition is clear.

Frankly, it’s a service everyone should have. Think about the potential time and money saved if this option for medical care and triage was broadly available. Overtriage would plummet. That’s when people run to the emergency department (ED) and wait endless hours, only to be reassured or receive limited treatment. Undertriage would also decline. That’s when people should go to the ED but, unwisely, wait. For example, this may occur when symptoms of dizziness end up being a stroke.

Why doesn’t everyone have an ED doctor they can call? The primary reason is that the current system mostly doesn’t support it. The most common scenario is that insurance companies pay us to see patients in an expensive box called the ED. Most EDs are situated within an even more expensive box, called a hospital.

Here’s the good news: Better access to emergency care and people who are formally trained in emergency medicine and routine matters of urgent care is increasing.

One example is telemedicine, where a remote doctor — either your own or a doctor through an app — conducts a visit. Telemedicine is more common since the pandemic, now that insurance pays for it. In emergency situations, it’s rare that your own doctor can see you immediately by telemedicine. By contrast, direct-to-consumer telemedicine (eg, Teladoc, Doctor On Demand, and others) connects you with a random doctor.

In many apps, it’s unclear not only who the doctor is, but more importantly, what their specific medical specialty or training is. It may be an ED doctor evaluating your child’s fever, or it may be a retired general surgeon or an adult rheumatology specialist in the midst of their fellowship, making an extra buck, who may have no pediatric training.

Training Matters

Clinical training and whether the doctor knows you matters. A recent JAMA study from Ontario, Canada, found that patients with virtual visits who saw outside family physicians (whom they had never met) compared with their own family physicians were 66% more likely to visit an ED within 7 days after the visit. This illustrates the importance of understanding your personal history in assessing acute symptoms.

Some healthcare systems do use ED physicians for on-demand telehealth services, such as Thomas Jefferson’s JeffConnect. Amazon Clinic recently entered this space, providing condition-specific acute or chronic care to adults aged 18-64 years for a fee that is, notably, not covered by insurance.

A second innovative approach, albeit not specifically in the realm of a personal emergency medicine doctor, is artificial intelligence (AI)–powered kiosks. A concierge medicine company known as Forward recently unveiled an innovative concept known as CarePods that are now available in Sacramento, California; Chandler, Arizona; and Chicago. For a membership fee, you swipe into what looks like an oversize, space-age porta-potty. You sit in a chair and run through a series of health apps, which includes a biometric body scan along with mental health screenings. It even takes your blood (without a needle) and sequences your DNA. Results are reviewed by a doctor (not yours) who talks to you by video. They advertise that AI helps make the diagnosis. Although diagnostic AI is emerging and exciting, its benefit is not clear in emergency conditions. Yet, one clear value in a kiosk over telemedicine is the ability to obtain vital signs and lab results, which are useful for diagnosis.

Another approach is the telehealth offerings used in integrated systems of care, such as Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser is both an insurance company and a deliverer of healthcare services. Kaiser maintains a nurse call center and can handle urgent e-visits. Integrated systems not only help triage patients’ acute issues but also have access to their personal health histories. They can also provide a definitive plan for in-person treatment or a specific referral. A downside of integrated care is that it often limits your choice of provider.

Insurance companies also maintain call-in lines such as HumanaFirst, which is also staffed by nurses. We have not seen data on the calls such services receive, but we doubt people that want to call their insurance company when sick or injured, knowing that the insurer benefits when you receive less care. Additionally, studies have found that nurse-only triage is not as effective as physician triage and results in higher ED referral rates.

The Concierge Option

Probably the closest thing to having your own personal emergency medicine doctor is concierge medicine, which combines personalized care and accessibility. Concierge doctors come in many forms, but they usually charge a fixed fee for 24/7 availability and same-day appointments. A downside of concierge medicine is its expense ($2000–$3500 per year), and that many don’t take insurance. Concierge medicine is also criticized because, as doctors gravitate toward it, people in the community often lose their physician if they can’t afford the fees.

Ultimately, remote medical advice for emergency care is clearly evolving in new ways. The inability of traditional care models to achieve this goal will lead to innovation to improve the available options that have led us to think outside of the proverbial “box” we refer to as the ED-in-the-case.

At this time, will any option come close to having a personal emergency medicine physician willing to answer your questions, real-time, as with family and close friends? We think not.

But the future certainly holds promise for alternatives that will hopefully make payers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services take notice. Innovations in personalized care that reduce costs will be critical in our current healthcare landscape.

Dr. Pines is clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, DC, and chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. He disclosed ties with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

How emerging models come close to making this reality

How emerging models come close to making this reality

As emergency medicine doctors, we regularly give medical advice to family and close friends when they get sick or are injured and don’t know what to do. In a matter of moments, we triage, diagnose, and assemble a logical plan, whatever the issue may be. This skill comes from our training and years of experience in treating emergencies and also routine medical matters. The value proposition is clear.

Frankly, it’s a service everyone should have. Think about the potential time and money saved if this option for medical care and triage was broadly available. Overtriage would plummet. That’s when people run to the emergency department (ED) and wait endless hours, only to be reassured or receive limited treatment. Undertriage would also decline. That’s when people should go to the ED but, unwisely, wait. For example, this may occur when symptoms of dizziness end up being a stroke.

Why doesn’t everyone have an ED doctor they can call? The primary reason is that the current system mostly doesn’t support it. The most common scenario is that insurance companies pay us to see patients in an expensive box called the ED. Most EDs are situated within an even more expensive box, called a hospital.

Here’s the good news: Better access to emergency care and people who are formally trained in emergency medicine and routine matters of urgent care is increasing.

One example is telemedicine, where a remote doctor — either your own or a doctor through an app — conducts a visit. Telemedicine is more common since the pandemic, now that insurance pays for it. In emergency situations, it’s rare that your own doctor can see you immediately by telemedicine. By contrast, direct-to-consumer telemedicine (eg, Teladoc, Doctor On Demand, and others) connects you with a random doctor.

In many apps, it’s unclear not only who the doctor is, but more importantly, what their specific medical specialty or training is. It may be an ED doctor evaluating your child’s fever, or it may be a retired general surgeon or an adult rheumatology specialist in the midst of their fellowship, making an extra buck, who may have no pediatric training.

Training Matters

Clinical training and whether the doctor knows you matters. A recent JAMA study from Ontario, Canada, found that patients with virtual visits who saw outside family physicians (whom they had never met) compared with their own family physicians were 66% more likely to visit an ED within 7 days after the visit. This illustrates the importance of understanding your personal history in assessing acute symptoms.

Some healthcare systems do use ED physicians for on-demand telehealth services, such as Thomas Jefferson’s JeffConnect. Amazon Clinic recently entered this space, providing condition-specific acute or chronic care to adults aged 18-64 years for a fee that is, notably, not covered by insurance.

A second innovative approach, albeit not specifically in the realm of a personal emergency medicine doctor, is artificial intelligence (AI)–powered kiosks. A concierge medicine company known as Forward recently unveiled an innovative concept known as CarePods that are now available in Sacramento, California; Chandler, Arizona; and Chicago. For a membership fee, you swipe into what looks like an oversize, space-age porta-potty. You sit in a chair and run through a series of health apps, which includes a biometric body scan along with mental health screenings. It even takes your blood (without a needle) and sequences your DNA. Results are reviewed by a doctor (not yours) who talks to you by video. They advertise that AI helps make the diagnosis. Although diagnostic AI is emerging and exciting, its benefit is not clear in emergency conditions. Yet, one clear value in a kiosk over telemedicine is the ability to obtain vital signs and lab results, which are useful for diagnosis.

Another approach is the telehealth offerings used in integrated systems of care, such as Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser is both an insurance company and a deliverer of healthcare services. Kaiser maintains a nurse call center and can handle urgent e-visits. Integrated systems not only help triage patients’ acute issues but also have access to their personal health histories. They can also provide a definitive plan for in-person treatment or a specific referral. A downside of integrated care is that it often limits your choice of provider.

Insurance companies also maintain call-in lines such as HumanaFirst, which is also staffed by nurses. We have not seen data on the calls such services receive, but we doubt people that want to call their insurance company when sick or injured, knowing that the insurer benefits when you receive less care. Additionally, studies have found that nurse-only triage is not as effective as physician triage and results in higher ED referral rates.

The Concierge Option

Probably the closest thing to having your own personal emergency medicine doctor is concierge medicine, which combines personalized care and accessibility. Concierge doctors come in many forms, but they usually charge a fixed fee for 24/7 availability and same-day appointments. A downside of concierge medicine is its expense ($2000–$3500 per year), and that many don’t take insurance. Concierge medicine is also criticized because, as doctors gravitate toward it, people in the community often lose their physician if they can’t afford the fees.

Ultimately, remote medical advice for emergency care is clearly evolving in new ways. The inability of traditional care models to achieve this goal will lead to innovation to improve the available options that have led us to think outside of the proverbial “box” we refer to as the ED-in-the-case.

At this time, will any option come close to having a personal emergency medicine physician willing to answer your questions, real-time, as with family and close friends? We think not.

But the future certainly holds promise for alternatives that will hopefully make payers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services take notice. Innovations in personalized care that reduce costs will be critical in our current healthcare landscape.

Dr. Pines is clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, DC, and chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. He disclosed ties with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As emergency medicine doctors, we regularly give medical advice to family and close friends when they get sick or are injured and don’t know what to do. In a matter of moments, we triage, diagnose, and assemble a logical plan, whatever the issue may be. This skill comes from our training and years of experience in treating emergencies and also routine medical matters. The value proposition is clear.

Frankly, it’s a service everyone should have. Think about the potential time and money saved if this option for medical care and triage was broadly available. Overtriage would plummet. That’s when people run to the emergency department (ED) and wait endless hours, only to be reassured or receive limited treatment. Undertriage would also decline. That’s when people should go to the ED but, unwisely, wait. For example, this may occur when symptoms of dizziness end up being a stroke.

Why doesn’t everyone have an ED doctor they can call? The primary reason is that the current system mostly doesn’t support it. The most common scenario is that insurance companies pay us to see patients in an expensive box called the ED. Most EDs are situated within an even more expensive box, called a hospital.

Here’s the good news: Better access to emergency care and people who are formally trained in emergency medicine and routine matters of urgent care is increasing.

One example is telemedicine, where a remote doctor — either your own or a doctor through an app — conducts a visit. Telemedicine is more common since the pandemic, now that insurance pays for it. In emergency situations, it’s rare that your own doctor can see you immediately by telemedicine. By contrast, direct-to-consumer telemedicine (eg, Teladoc, Doctor On Demand, and others) connects you with a random doctor.

In many apps, it’s unclear not only who the doctor is, but more importantly, what their specific medical specialty or training is. It may be an ED doctor evaluating your child’s fever, or it may be a retired general surgeon or an adult rheumatology specialist in the midst of their fellowship, making an extra buck, who may have no pediatric training.

Training Matters

Clinical training and whether the doctor knows you matters. A recent JAMA study from Ontario, Canada, found that patients with virtual visits who saw outside family physicians (whom they had never met) compared with their own family physicians were 66% more likely to visit an ED within 7 days after the visit. This illustrates the importance of understanding your personal history in assessing acute symptoms.

Some healthcare systems do use ED physicians for on-demand telehealth services, such as Thomas Jefferson’s JeffConnect. Amazon Clinic recently entered this space, providing condition-specific acute or chronic care to adults aged 18-64 years for a fee that is, notably, not covered by insurance.

A second innovative approach, albeit not specifically in the realm of a personal emergency medicine doctor, is artificial intelligence (AI)–powered kiosks. A concierge medicine company known as Forward recently unveiled an innovative concept known as CarePods that are now available in Sacramento, California; Chandler, Arizona; and Chicago. For a membership fee, you swipe into what looks like an oversize, space-age porta-potty. You sit in a chair and run through a series of health apps, which includes a biometric body scan along with mental health screenings. It even takes your blood (without a needle) and sequences your DNA. Results are reviewed by a doctor (not yours) who talks to you by video. They advertise that AI helps make the diagnosis. Although diagnostic AI is emerging and exciting, its benefit is not clear in emergency conditions. Yet, one clear value in a kiosk over telemedicine is the ability to obtain vital signs and lab results, which are useful for diagnosis.

Another approach is the telehealth offerings used in integrated systems of care, such as Kaiser Permanente. Kaiser is both an insurance company and a deliverer of healthcare services. Kaiser maintains a nurse call center and can handle urgent e-visits. Integrated systems not only help triage patients’ acute issues but also have access to their personal health histories. They can also provide a definitive plan for in-person treatment or a specific referral. A downside of integrated care is that it often limits your choice of provider.

Insurance companies also maintain call-in lines such as HumanaFirst, which is also staffed by nurses. We have not seen data on the calls such services receive, but we doubt people that want to call their insurance company when sick or injured, knowing that the insurer benefits when you receive less care. Additionally, studies have found that nurse-only triage is not as effective as physician triage and results in higher ED referral rates.

The Concierge Option

Probably the closest thing to having your own personal emergency medicine doctor is concierge medicine, which combines personalized care and accessibility. Concierge doctors come in many forms, but they usually charge a fixed fee for 24/7 availability and same-day appointments. A downside of concierge medicine is its expense ($2000–$3500 per year), and that many don’t take insurance. Concierge medicine is also criticized because, as doctors gravitate toward it, people in the community often lose their physician if they can’t afford the fees.

Ultimately, remote medical advice for emergency care is clearly evolving in new ways. The inability of traditional care models to achieve this goal will lead to innovation to improve the available options that have led us to think outside of the proverbial “box” we refer to as the ED-in-the-case.

At this time, will any option come close to having a personal emergency medicine physician willing to answer your questions, real-time, as with family and close friends? We think not.

But the future certainly holds promise for alternatives that will hopefully make payers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services take notice. Innovations in personalized care that reduce costs will be critical in our current healthcare landscape.

Dr. Pines is clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University in Washington, DC, and chief of clinical innovation at US Acute Care Solutions in Canton, Ohio. He disclosed ties with CSL Behring and Abbott Point-of-Care. Dr. Glatter is assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is a medical advisor for Medscape and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk Factors For Unplanned ICU Transfer

Emergency Department (ED) patients who are hospitalized and require unplanned transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) within 24 hours of arrival on the ward have higher mortality than direct ICU admissions.1, 2 Previous research found that 5% of ED admissions experienced unplanned ICU transfer during their hospitalization, yet these patients account for 25% of in‐hospital deaths and have a longer length of stay than direct ICU admissions.1, 3 For these reasons, inpatient rapid‐response teams and early warning systems have been studied to reduce the mortality of patients who rapidly deteriorate on the hospital ward.410 However, there is little conclusive evidence that these interventions decrease mortality.710 It is possible that with better recognition and intervention in the ED, a portion of these unplanned ICU transfers and their subsequent adverse outcomes could be prevented.11

Previous research on risk factors for unplanned ICU transfers among ED admissions is limited. While 2 previous studies from non‐US hospitals used administrative data to identify some general populations at risk for unplanned ICU transfer,12, 13 these studies did not differentiate between transfers shortly after admission and those that occurred during a prolonged hospital staya critical distinction since the outcomes between these groups differs substantially.1 Another limitation of these studies is the absence of physiologic measures at ED presentation, which have been shown to be highly predictive of mortality.14

In this study, we describe risk factors for unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival on the ward, among a large cohort of ED hospitalizations across 13 community hospitals. Focusing on admitting diagnoses most at risk, our goal was to inform efforts to improve the triage of ED admissions and determine which patients may benefit from additional interventions, such as improved resuscitation, closer monitoring, or risk stratification tools. We also hypothesized that higher volume hospitals would have lower rates of unplanned ICU transfers, as these hospitals are more likely have more patient care resources on the hospital ward and a higher threshold to transfer to the ICU.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

The setting for this study was Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated healthcare delivery system serving approximately 3.3 million members.1, 3, 15, 16 We extracted data on all adult ED admissions (18 years old) to the hospital between 2007 and 2009. We excluded patients who went directly to the operating room or the ICU, as well as gynecological/pregnancy‐related admissions, as these patients have substantially different mortality risks.14 ED admissions to hospital wards could either go to medicalsurgical units or transitional care units (TCU), an intermediate level of care between the medicalsurgical units and the ICU. We chose to focus on hospitals with similar inpatient structures. Thus, 8 hospitals without TCUs were excluded, leaving 13 hospitals for analysis. The KPNC Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Main Outcome Measure

The main outcome measure was unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival to the hospital ward, based upon bed history data. As in previous research, we make the assumptionwhich is supported by the high observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios found in these patientsthat these transfers to the ICU were due to clinical deterioration, and thus were unplanned, rather than a planned transfer to the ICU as is more common after an elective surgical procedure.13 The comparison population was patients admitted from the ED to the ward who never experienced a transfer to the ICU.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

We extracted patient data on age, sex, admitting diagnosis, chronic illness burden, acute physiologic derangement in the ED, and hospital unit length of stay. Chronic illness was measured using the Comorbidity Point Score (COPS), and physiologic derangement was measured using the Laboratory Acute Physiology Score (LAPS) calculated from labs collected in the ED.1, 14, 17 The derivation of these variables from the electronic medical record has been previously described.14 The COPS was derived from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes for all Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program (KPMCP) inpatient and outpatient encounters prior to hospitalization. The LAPS is based on 14 possible lab tests that could be drawn in the ED or in the 72 hours prior to hospitalization. The admitting diagnosis is the ICD‐9 code assigned for the primary diagnosis determined by the admitting physician at the time when hospital admission orders are entered. We further collapsed a previously used categorization of 44 primary condition diagnoses, based on admission ICD‐9 codes,14 into 25 broad diagnostic categories based on pathophysiologic plausibility and mortality rates. We tabulated inpatient admissions originating in the ED to derive a hospital volume measure.

Statistical Analyses

We compared patient characteristics, hospital volume, and outcomes by whether or not an unplanned ICU transfer occurred. Unadjusted analyses were performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi‐square tests. We calculated crude rates of unplanned ICU transfer per 1,000 ED inpatient admissions by patient characteristics and by hospital, stratified by hospital volume.

We used a hierarchical multivariate logistic regression model to estimate adjusted odds ratios for unplanned ICU transfer as a function of both patient‐level variables (age, sex, COPS, LAPS, time of admission, admission to TCU vs ward, admitting diagnosis) and hospital‐level variables (volume) in the model. We planned to choose the reference group for admitting diagnosis as the one with an unadjusted odds ratio closest to the null (1.00). This model addresses correlations between patients with multiple hospitalizations and clustering by hospital, by fitting random intercepts for these clusters. All analyses were performed in Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and statistics are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Stata program gllamm (Generalized Linear Latent and Mixed Models) was used for hierarchical modeling.18

RESULTS

Of 178,315 ED non‐ICU hospitalizations meeting inclusion criteria, 4,252 (2.4%) were admitted to the ward and were transferred to the ICU within 24 hours of leaving the ED. There were 122,251 unique patients in our study population. Table 1 compares the characteristics of ED hospitalizations in which an unplanned transfer occurred to those that did not experience an unplanned transfer. Unplanned transfers were more likely to have a higher comorbidity burden, more deranged physiology, and more likely to arrive on the floor during the overnight shift.

| Characteristics | Unplanned Transfer to ICU Within 24 h of Leaving ED? | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| N = 4,252 (2.4%) | N = 174,063 (97.6%) | ||

| |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 69 (5680) | 70 (5681) | <0.01 |

| Male, % | 51.3 | 45.9 | <0.01 |

| Comorbidity Points Score (COPS), median (IQR) | 100 (46158) | 89 (42144) | <0.01 |

| Laboratory Acute Physiology Score (LAPS), median (IQR) | 26 (1342) | 18 (633) | <0.01 |

| Nursing shift on arrival to floor, % | |||

| Day: 7 am3 pm (Reference) | 20.1 | 20.1 | NS |

| Evening: 3 pm11 pm | 47.6 | 50.2 | NS |

| Overnight: 11 pm7 am | 32.3 | 29.7 | <0.01 |

| Weekend admission, % | 33.7 | 32.7 | NS |

| Admitted to monitored bed, % | 24.1 | 24.9 | NS |

| Emergency department annual volume, mean (SD) | 48,755 (15,379) | 50,570 (15,276) | <0.01 |

| Non‐ICU annual admission volume, mean (SD) | 5,562 (1,626) | 5,774 (1,568) | <0.01 |

| Admitting diagnosis, listed by descending frequency, % | NS | ||

| Pneumonia and respiratory infections | 16.3 | 11.8 | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 12.8 | 13.6 | NS |

| Chest pain | 7.3 | 10.0 | <0.01 |

| Miscellaneous conditions | 5.6 | 6.2 | NS |

| All other acute infections | 4.7 | 6.0 | <0.01 |

| Seizures | 4.1 | 5.9 | <0.01 |

| AMI | 3.9 | 3.3 | <0.05 |

| COPD | 3.8 | 3.0 | <0.01 |

| CHF | 3.5 | 3.7 | NS |

| Arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism | 3.5 | 3.3 | NS |

| Stroke | 3.4 | 3.5 | NS |

| Diabetic emergencies | 3.3 | 2.6 | <0.01 |

| Metabolic, endocrine, electrolytes | 3.0 | 2.9 | NS |

| Sepsis | 3.0 | 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Other neurology and toxicology | 3.0 | 2.9 | NS |

| Urinary tract infections | 2.9 | 3.2 | NS |

| Catastrophic conditions | 2.6 | 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Rheumatology | 2.5 | 3.5 | <0.01 |

| Hematology and oncology | 2.4 | 2.4 | NS |

| Acute renal failure | 1.9 | 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Pancreatic and liver | 1.7 | 2.0 | NS |

| Trauma, fractures, and dislocations | 1.6 | 1.8 | NS |

| Bowel obstructions and diseases | 1.6 | 2.9 | <0.01 |

| Other cardiac conditions | 1.5 | 1.3 | NS |

| Other renal conditions | 0.6 | 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Inpatient length of stay, median days (IQR) | 4.7 (2.78.6) | 2.6 (1.54.4) | <0.01 |

| Died during hospitalization, % | 12.7 | 2.4 | <0.01 |

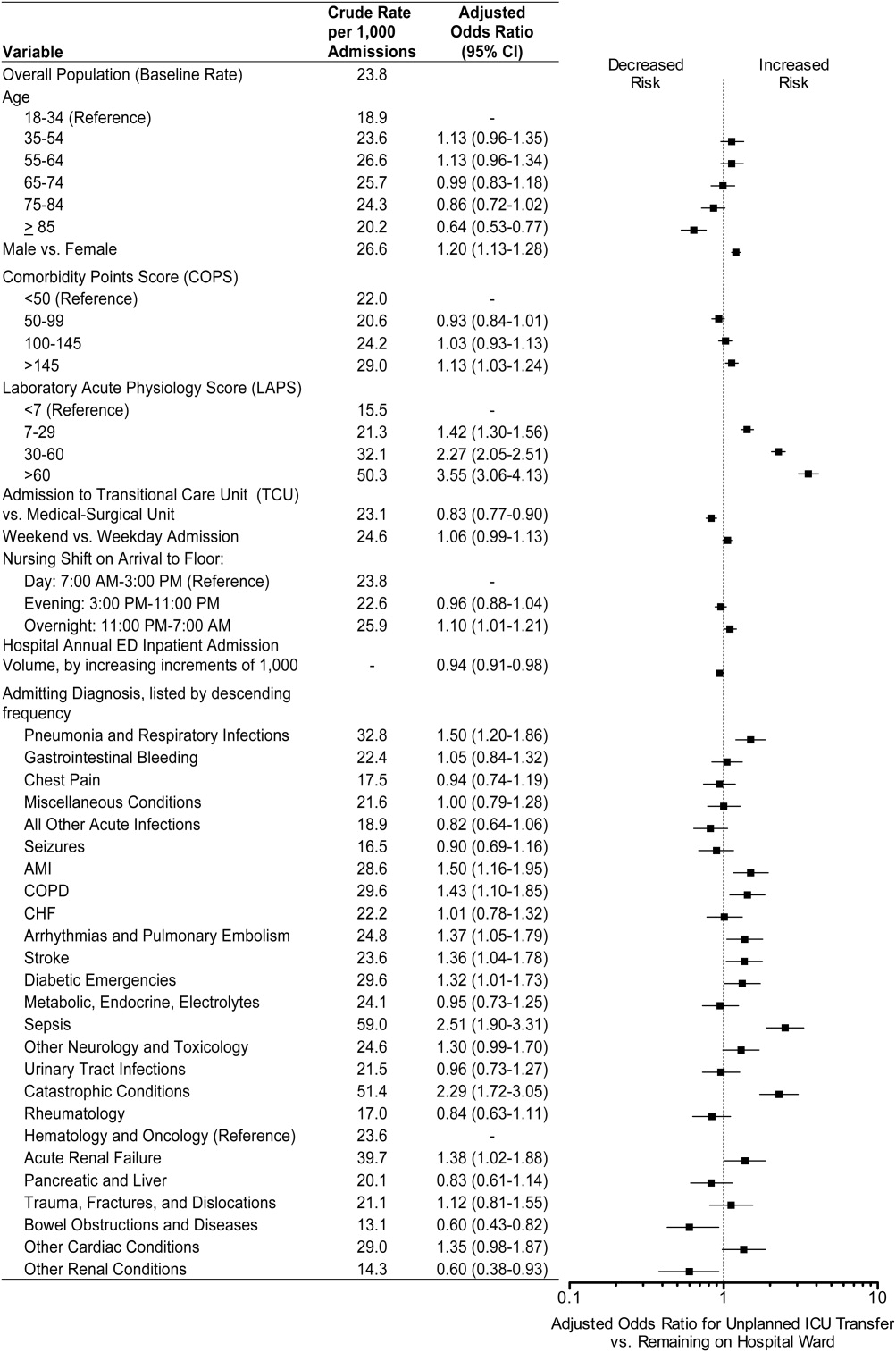

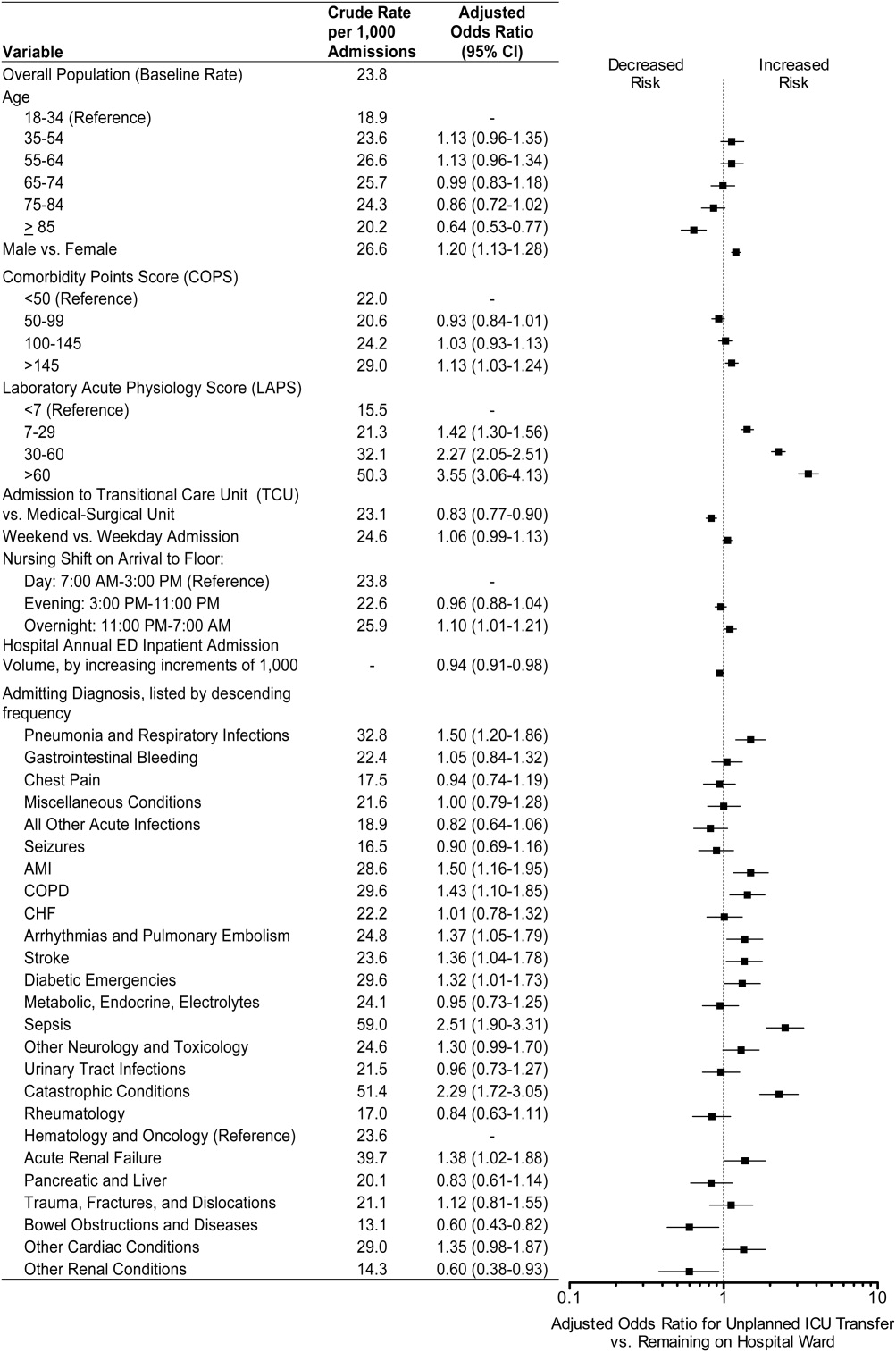

Unplanned ICU transfers were more frequent in lower volume hospitals (Table 1). Figure 1 displays the inverse relationship between hospital annual ED inpatient admission volume and unplanned ICU transfers rates. The lowest volume hospital had a crude rate twice as high as the 2 highest volume hospitals (39 vs 20, per 1,000 admissions).

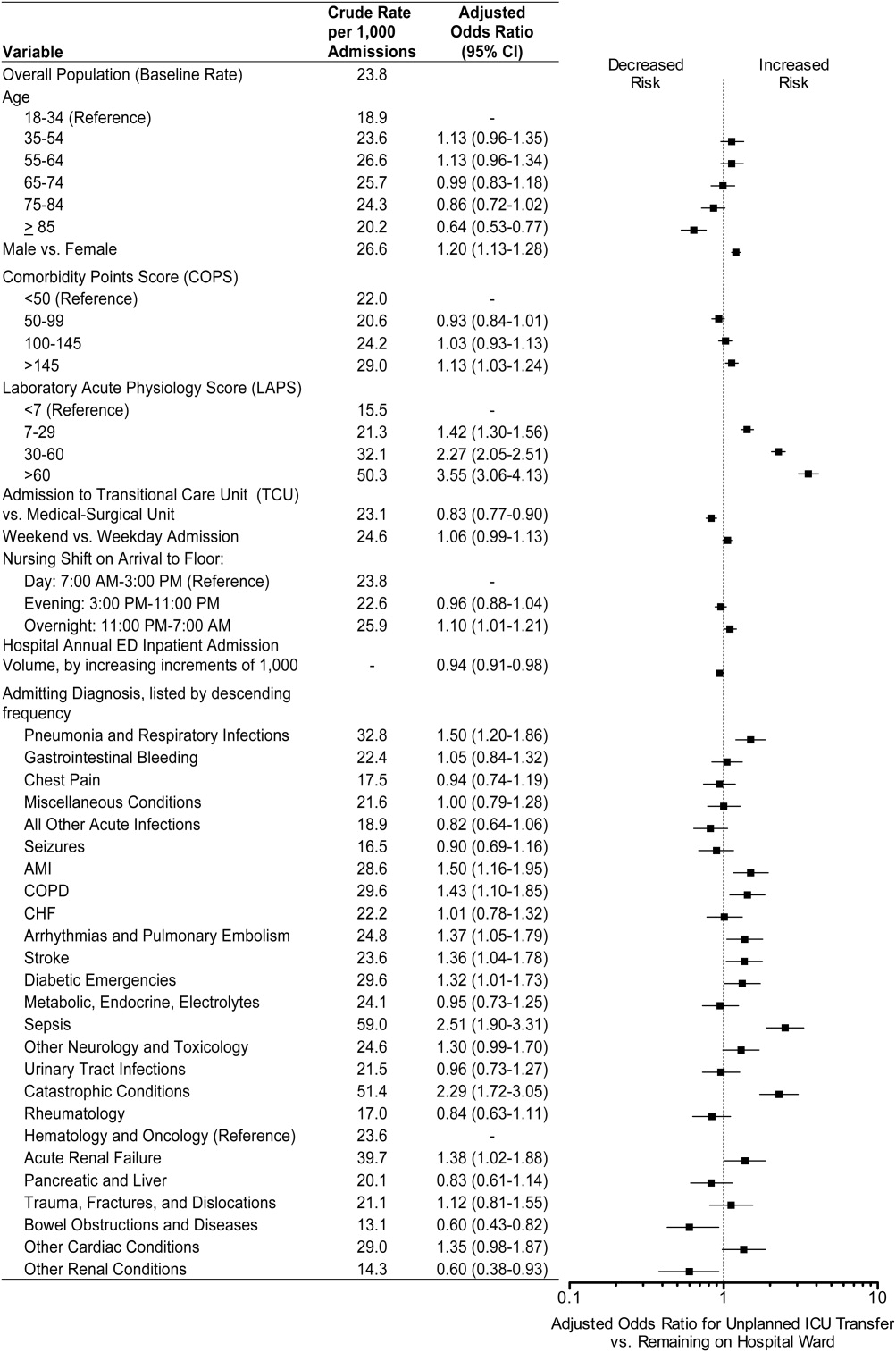

Pneumonia/respiratory infection was the most frequent admitting condition associated with unplanned transfer (16.3%) (Table 1). There was also wide variation in crude rates for unplanned ICU transfer by admitting condition (Figure 2). Patients admitted with sepsis had the highest rate (59 per 1,000 admissions), while patients admitted with renal conditions other than acute renal failure had the lowest rates (14.3 per 1,000 admissions).

We confirmed that almost all diagnoses found to account for a disproportionately high share of unplanned ICU transfers in Table 1 were indeed independently associated with this phenomenon after adjustment for patient and hospital differences (Figure 2). Pneumonia remained the most frequent condition associated with unplanned ICU transfer (odds ratio [OR] 1.50; 95% CI 1.201.86). Although less frequent, sepsis had the strongest association of any condition with unplanned transfer (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.903.31). However, metabolic, endocrine, and electrolyte conditions were no longer associated with unplanned transfer after adjustment, while arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism were. Other conditions confirmed to be associated with increased risk of unplanned transfer included: myocardial infarction (MI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, diabetic emergencies, catastrophic conditions (includes aortic catastrophes, all forms of shock except septic shock, and intracranial hemorrhage), and acute renal failure. After taking into account the frequency of admitting diagnoses, respiratory conditions (COPD, pneumonia/acute respiratory infection) comprised nearly half (47%) of all conditions associated with increased risk of unplanned ICU transfer.

Other factors confirmed to be independently associated with unplanned ICU transfer included: male sex (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.131.28), high comorbidity burden as measured by COPS >145 (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.031.24), increasingly abnormal physiology compared to a LAPS <7, and arrival on ward during the overnight shift (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.011.21). After adjustment, we did find that admission to the TCU rather than a medicalsurgical unit was associated with decreased risk of unplanned ICU transfer (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.770.90). Age 85 was associated with decreased risk of unplanned ICU transfer relative to the youngest age group of 1834‐year‐old patients (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.530.77).

ED admissions to higher volume hospitals were 6% less likely to experience an unplanned transfer for each additional 1,000 annual ED hospitalizations over a lower volume hospital (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.910.98). In other words, a patient admitted to a hospital with 8,000 annual ED hospitalizations had 30% decreased odds of unplanned ICU transfer compared to a hospital with only 3,000 annual ED hospitalizations.

DISCUSSION

Patients admitted with respiratory conditions accounted for half of all admitting diagnoses associated with increased risk of unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival to the ward. We found that 1 in 30 ED ward admissions for pneumonia, and 1 in 33 for COPD, were transferred to the ICU within 24 hours. These findings indicate that there is some room for improvement in early care of respiratory conditions, given the average unplanned transfer rate of 1 in 42, and previous research showing that patients with pneumonia and patients with COPD, who experience unplanned ICU transfer, have substantially worse mortality than those directly admitted to the ICU.1

Although less frequent than hospitalizations for respiratory conditions, patients admitted with sepsis were at the highest risk of unplanned ICU transfer (1 in 17 ED non‐ICU hospitalizations). We also found that MI and stroke ward admissions had a higher risk of unplanned ICU transfer. However, we previously found that unplanned ICU transfers for sepsis, MI, and stroke did not have worse mortality than direct ICU admits for these conditions.1 Therefore, quality improvement efforts to reduce excess mortality related to early decompensation in the hospital and unplanned ICU transfer would be most effective if targeted towards respiratory conditions such as pneumonia and COPD.

This is the only in‐depth study, to our knowledge, to explore the association between a set of mutually exclusive diagnostic categories and risk of unplanned ICU transfer within 24 hours, and it is the first study to identify risk factors for unplanned ICU transfer in a multi‐hospital cohort adjusted for patient‐ and hospital‐level characteristics. We also identified a novel hospital volumeoutcome relationship: Unplanned ICU transfers are up to twice as likely to occur in the smallest volume hospitals compared with highest volume hospitals. Hospital volume has long been proposed as a proxy for hospital resources; there are several studies showing a relationship between low‐volume hospitals and worse outcomes for a number of conditions.19, 20 Possible mechanisms may include decreased ICU capacity, decreased on‐call intensivists in the hospital after hours, and less experience with certain critical care conditions seen more frequently in high‐volume hospitals.21

Patients at risk of unplanned ICU transfer were also more likely to have physiologic derangement identified on laboratory testing, high comorbidity burden, and arrive on the ward between 11 PM and 7 AM. Given the strong correlation between comorbidity burden and physiologic derangement and mortality,14 it is not surprising that the COPS and LAPS were independent predictors of unplanned transfer. It is unclear, however, why arriving on the ward on the overnight shift is associated with higher risk. One possibility is that patients who arrive on the wards during 11 PM to 7 AM are also likely to have been in the ED during evening peak hours most associated with ED crowding.22 High levels of ED crowding have been associated with delays in care, worse quality care, lapses in patient safety, and even increased in‐hospital mortality.22, 23 Other possible reasons include decreased in‐hospital staffing and longer delays in critical diagnostic tests and interventions.2428

Admission to TCUs was associated with decreased risk of unplanned ICU transfer in the first 24 hours of hospitalization. This may be due to the continuous monitoring, decreased nursing‐to‐patient ratios, or the availability to provide some critical care interventions. In our study, age 85 was associated with lower likelihood of unplanned transfer. Unfortunately, we did not have access to data on advanced directives or patient preferences. Data on advanced directives would help to distinguish whether this phenomenon was related to end‐of‐life care goals versus other explanations.

Our study confirms some risk factors identified in previous studies. These include specific diagnoses such as pneumonia and COPD,12, 13, 29 heavy comorbidity burden,12, 13, 29 abnormal labs,29 and male sex.13 Pneumonia has consistently been shown to be a risk factor for unplanned ICU transfer. This may stem from the dynamic nature of this condition and its ability to rapidly progress, and the fact that some ICUs may not accept pneumonia patients unless they demonstrate a need for mechanical ventilation.30 Recently, a prediction rule has been developed to determine which patients with pneumonia are likely to have an unplanned ICU transfer.30 It is possible that with validation and application of this rule, unplanned transfer rates for pneumonia could be reduced. It is unclear whether males have unmeasured factors associated with increased risk of unplanned transfer or whether a true gender disparity exists.

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of this study's limitations. First, this study was not designed to distinguish the underlying cause of the unplanned transfer such as under‐recognition of illness severity in the ED, evolving clinical disease after leaving the ED, or delays in critical interventions on the ward. These are a focus of our ongoing research efforts. Second, while previous studies have demonstrated that our automated risk adjustment variables can accurately predict in‐hospital mortality (0.88 area under curve in external populations),17 additional data on vital signs and mental status could further improve risk adjustment. However, using automated data allowed us to study risk factors for unplanned transfer in a multi‐hospital cohort with a much larger population than has been previously studied. Serial data on vital signs and mental status both in the ED and during hospitalization could also be helpful in determining which unplanned transfers could be prevented with earlier recognition and intervention. Finally, all patient care occurred within an integrated healthcare delivery system. Thus, differences in case‐mix, hospital resources, ICU structure, and geographic location should be considered when applying our results to other healthcare systems.

This study raises several new areas for future research. With access to richer data becoming available in electronic medical records, prediction rules should be developed to enable better triage to appropriate levels of care for ED admissions. Future research should also analyze the comparative effectiveness of intermediate monitored units versus non‐monitored wards for preventing clinical deterioration by admitting diagnosis. Diagnoses that have been shown to have an increased risk of death after unplanned ICU transfer, such as pneumonia/respiratory infection and COPD,1 should be prioritized in this research. Better understanding is needed on the diagnosis‐specific differences and the differences in ED triage process and ICU structure that may explain why high‐volume hospitals have significantly lower rates of early unplanned ICU transfers compared with low‐volume hospitals. In particular, determining the effect of TCU and ICU capacities and census at the time of admission, and comparing patient risk characteristics across hospital‐volume strata would be very useful. Finally, more work is needed to determine whether the higher rate of unplanned transfers during overnight nursing shifts is related to decreased resource availability, preceding ED crowding, or other organizational causes.

In conclusion, patients admitted with respiratory conditions, sepsis, MI, high comorbidity, and abnormal labs are at modestly increased risk of unplanned ICU transfer within 24 hours of admission from the ED. Patients admitted with respiratory conditions (pneumonia/respiratory infections and COPD) accounted for half of the admitting diagnoses that are at increased risk for unplanned ICU transfer. These patients may benefit from better inpatient triage from the ED, earlier intervention, or closer monitoring. More research is needed to determine the specific aspects of care associated with admission to intermediate care units and high‐volume hospitals that reduce the risk of unplanned ICU transfer.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank John D. Greene, Juan Carlos La Guardia, and Benjamin Turk for their assistance with formatting of the dataset; Dr Alan S. Go, Acting Director of the Division of Research, for reviewing the manuscript; and Alina Schnake‐Mahl for formatting the manuscript.

- , , , et al. Adverse outcomes associated with delayed intensive care unit transfers in an integrated healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2011;7(3):224–230.

- , , , et al. Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):77–83.

- , , , et al. Intra‐hospital transfers to a higher level of care: contribution to total hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) mortality and length of stay (LOS). J Hosp Med. 2011;6:74–80.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300(21):2506–2513.

- , , , et al. Effect of a rapid response team on hospital‐wide mortality and code rates outside the ICU in a children's hospital. JAMA. 2007;298(19):2267–2274.

- , , , et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091–2097.

- , , , et al. Rapid response systems: A systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1238–1243.

- , , , et al. Effects of rapid response systems on clinical outcomes: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(6):422–432.

- , , , et al. Rapid response teams: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):18–26.

- , , , et al. Outreach and early warning systems (EWS) for the prevention of intensive care admission and death of critically ill adult patients on general hospital wards. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD005529.

- , , , et al. Unplanned transfers to a medical intensive care unit: Causes and relationship to preventable errors in care. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:68–72.

- , , , et al. Using administrative data to develop a nomogram for individualising risk of unplanned admission to intensive care. Resuscitation. 2008;79(2):241–248.

- , , , et al. Unplanned admission to intensive care after emergency hospitalisation: risk factors and development of a nomogram for individualising risk. Resuscitation. 2009;80(2):224–230.

- , , , et al. Risk‐adjusting hospital inpatient mortality using automated inpatient, outpatient, and laboratory databases. Med Care. 2008;46(3):232–239.

- . Linking automated databases for research in managed care settings. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8 pt 2):719–724.

- , , , et al. Risk adjusting community‐acquired pneumonia hospital outcomes using automated databases. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(3):158–166.

- , , , et al. The Kaiser Permanente inpatient risk adjustment methodology was valid in an external patient population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;63(7):798–803.

- , , . Maximum likelihood estimation of limited and discrete dependent variable models with nested random effects. J Econometrics. 2005;128(2):301–323.

- . The relation between volume and outcome in health care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(21):1677–1679.

- , , . Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(6):511–520.

- , , . Working with capacity limitations: operations management in critical care. Crit Care. 2011;15(4):308.

- , . Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann Intern Med. 2008;52(2):126–136.

- , , , et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10.

- , , , et al. Association between time of admission to the ICU and mortality. Chest. 2010;138(1):68–75.

- , , , et al. Off‐hour admission and in‐hospital stroke case fatality in the get with the guidelines‐stroke program. Stroke. 2009;40(2):569–576.

- , , , et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in‐hospital mortality for patients with acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2005;294(7):803–812.

- , , , et al. Hospital mortality among adults admitted to and discharged from intensive care on weekends and evenings. J Crit Care. 2008;23(3):317–324.

- , , , et al. Association between ICU admission during morning rounds and mortality. Chest. 2009;136(6):1489–1495.

- , , , et al. Identifying infected emergency department patients admitted to the hospital ward at risk of clinical deterioration and intensive care unit transfer. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(10):1080–1085.

- , , , et al. Risk stratification of early admission to the intensive care unit of patients with no major criteria of severe community‐acquired pneumonia: development of an international prediction rule. Crit Care. 2009;13(2):R54.

Emergency Department (ED) patients who are hospitalized and require unplanned transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) within 24 hours of arrival on the ward have higher mortality than direct ICU admissions.1, 2 Previous research found that 5% of ED admissions experienced unplanned ICU transfer during their hospitalization, yet these patients account for 25% of in‐hospital deaths and have a longer length of stay than direct ICU admissions.1, 3 For these reasons, inpatient rapid‐response teams and early warning systems have been studied to reduce the mortality of patients who rapidly deteriorate on the hospital ward.410 However, there is little conclusive evidence that these interventions decrease mortality.710 It is possible that with better recognition and intervention in the ED, a portion of these unplanned ICU transfers and their subsequent adverse outcomes could be prevented.11

Previous research on risk factors for unplanned ICU transfers among ED admissions is limited. While 2 previous studies from non‐US hospitals used administrative data to identify some general populations at risk for unplanned ICU transfer,12, 13 these studies did not differentiate between transfers shortly after admission and those that occurred during a prolonged hospital staya critical distinction since the outcomes between these groups differs substantially.1 Another limitation of these studies is the absence of physiologic measures at ED presentation, which have been shown to be highly predictive of mortality.14

In this study, we describe risk factors for unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival on the ward, among a large cohort of ED hospitalizations across 13 community hospitals. Focusing on admitting diagnoses most at risk, our goal was to inform efforts to improve the triage of ED admissions and determine which patients may benefit from additional interventions, such as improved resuscitation, closer monitoring, or risk stratification tools. We also hypothesized that higher volume hospitals would have lower rates of unplanned ICU transfers, as these hospitals are more likely have more patient care resources on the hospital ward and a higher threshold to transfer to the ICU.

METHODS

Setting and Patients

The setting for this study was Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large integrated healthcare delivery system serving approximately 3.3 million members.1, 3, 15, 16 We extracted data on all adult ED admissions (18 years old) to the hospital between 2007 and 2009. We excluded patients who went directly to the operating room or the ICU, as well as gynecological/pregnancy‐related admissions, as these patients have substantially different mortality risks.14 ED admissions to hospital wards could either go to medicalsurgical units or transitional care units (TCU), an intermediate level of care between the medicalsurgical units and the ICU. We chose to focus on hospitals with similar inpatient structures. Thus, 8 hospitals without TCUs were excluded, leaving 13 hospitals for analysis. The KPNC Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Main Outcome Measure

The main outcome measure was unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival to the hospital ward, based upon bed history data. As in previous research, we make the assumptionwhich is supported by the high observed‐to‐expected mortality ratios found in these patientsthat these transfers to the ICU were due to clinical deterioration, and thus were unplanned, rather than a planned transfer to the ICU as is more common after an elective surgical procedure.13 The comparison population was patients admitted from the ED to the ward who never experienced a transfer to the ICU.

Patient and Hospital Characteristics

We extracted patient data on age, sex, admitting diagnosis, chronic illness burden, acute physiologic derangement in the ED, and hospital unit length of stay. Chronic illness was measured using the Comorbidity Point Score (COPS), and physiologic derangement was measured using the Laboratory Acute Physiology Score (LAPS) calculated from labs collected in the ED.1, 14, 17 The derivation of these variables from the electronic medical record has been previously described.14 The COPS was derived from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes for all Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program (KPMCP) inpatient and outpatient encounters prior to hospitalization. The LAPS is based on 14 possible lab tests that could be drawn in the ED or in the 72 hours prior to hospitalization. The admitting diagnosis is the ICD‐9 code assigned for the primary diagnosis determined by the admitting physician at the time when hospital admission orders are entered. We further collapsed a previously used categorization of 44 primary condition diagnoses, based on admission ICD‐9 codes,14 into 25 broad diagnostic categories based on pathophysiologic plausibility and mortality rates. We tabulated inpatient admissions originating in the ED to derive a hospital volume measure.

Statistical Analyses

We compared patient characteristics, hospital volume, and outcomes by whether or not an unplanned ICU transfer occurred. Unadjusted analyses were performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi‐square tests. We calculated crude rates of unplanned ICU transfer per 1,000 ED inpatient admissions by patient characteristics and by hospital, stratified by hospital volume.

We used a hierarchical multivariate logistic regression model to estimate adjusted odds ratios for unplanned ICU transfer as a function of both patient‐level variables (age, sex, COPS, LAPS, time of admission, admission to TCU vs ward, admitting diagnosis) and hospital‐level variables (volume) in the model. We planned to choose the reference group for admitting diagnosis as the one with an unadjusted odds ratio closest to the null (1.00). This model addresses correlations between patients with multiple hospitalizations and clustering by hospital, by fitting random intercepts for these clusters. All analyses were performed in Stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and statistics are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Stata program gllamm (Generalized Linear Latent and Mixed Models) was used for hierarchical modeling.18

RESULTS

Of 178,315 ED non‐ICU hospitalizations meeting inclusion criteria, 4,252 (2.4%) were admitted to the ward and were transferred to the ICU within 24 hours of leaving the ED. There were 122,251 unique patients in our study population. Table 1 compares the characteristics of ED hospitalizations in which an unplanned transfer occurred to those that did not experience an unplanned transfer. Unplanned transfers were more likely to have a higher comorbidity burden, more deranged physiology, and more likely to arrive on the floor during the overnight shift.

| Characteristics | Unplanned Transfer to ICU Within 24 h of Leaving ED? | P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| N = 4,252 (2.4%) | N = 174,063 (97.6%) | ||

| |||

| Age, median (IQR) | 69 (5680) | 70 (5681) | <0.01 |

| Male, % | 51.3 | 45.9 | <0.01 |

| Comorbidity Points Score (COPS), median (IQR) | 100 (46158) | 89 (42144) | <0.01 |

| Laboratory Acute Physiology Score (LAPS), median (IQR) | 26 (1342) | 18 (633) | <0.01 |

| Nursing shift on arrival to floor, % | |||

| Day: 7 am3 pm (Reference) | 20.1 | 20.1 | NS |

| Evening: 3 pm11 pm | 47.6 | 50.2 | NS |

| Overnight: 11 pm7 am | 32.3 | 29.7 | <0.01 |

| Weekend admission, % | 33.7 | 32.7 | NS |

| Admitted to monitored bed, % | 24.1 | 24.9 | NS |

| Emergency department annual volume, mean (SD) | 48,755 (15,379) | 50,570 (15,276) | <0.01 |

| Non‐ICU annual admission volume, mean (SD) | 5,562 (1,626) | 5,774 (1,568) | <0.01 |

| Admitting diagnosis, listed by descending frequency, % | NS | ||

| Pneumonia and respiratory infections | 16.3 | 11.8 | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 12.8 | 13.6 | NS |

| Chest pain | 7.3 | 10.0 | <0.01 |

| Miscellaneous conditions | 5.6 | 6.2 | NS |

| All other acute infections | 4.7 | 6.0 | <0.01 |

| Seizures | 4.1 | 5.9 | <0.01 |

| AMI | 3.9 | 3.3 | <0.05 |

| COPD | 3.8 | 3.0 | <0.01 |

| CHF | 3.5 | 3.7 | NS |

| Arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism | 3.5 | 3.3 | NS |

| Stroke | 3.4 | 3.5 | NS |

| Diabetic emergencies | 3.3 | 2.6 | <0.01 |

| Metabolic, endocrine, electrolytes | 3.0 | 2.9 | NS |

| Sepsis | 3.0 | 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Other neurology and toxicology | 3.0 | 2.9 | NS |

| Urinary tract infections | 2.9 | 3.2 | NS |

| Catastrophic conditions | 2.6 | 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Rheumatology | 2.5 | 3.5 | <0.01 |

| Hematology and oncology | 2.4 | 2.4 | NS |

| Acute renal failure | 1.9 | 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Pancreatic and liver | 1.7 | 2.0 | NS |

| Trauma, fractures, and dislocations | 1.6 | 1.8 | NS |

| Bowel obstructions and diseases | 1.6 | 2.9 | <0.01 |

| Other cardiac conditions | 1.5 | 1.3 | NS |

| Other renal conditions | 0.6 | 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Inpatient length of stay, median days (IQR) | 4.7 (2.78.6) | 2.6 (1.54.4) | <0.01 |

| Died during hospitalization, % | 12.7 | 2.4 | <0.01 |

Unplanned ICU transfers were more frequent in lower volume hospitals (Table 1). Figure 1 displays the inverse relationship between hospital annual ED inpatient admission volume and unplanned ICU transfers rates. The lowest volume hospital had a crude rate twice as high as the 2 highest volume hospitals (39 vs 20, per 1,000 admissions).

Pneumonia/respiratory infection was the most frequent admitting condition associated with unplanned transfer (16.3%) (Table 1). There was also wide variation in crude rates for unplanned ICU transfer by admitting condition (Figure 2). Patients admitted with sepsis had the highest rate (59 per 1,000 admissions), while patients admitted with renal conditions other than acute renal failure had the lowest rates (14.3 per 1,000 admissions).

We confirmed that almost all diagnoses found to account for a disproportionately high share of unplanned ICU transfers in Table 1 were indeed independently associated with this phenomenon after adjustment for patient and hospital differences (Figure 2). Pneumonia remained the most frequent condition associated with unplanned ICU transfer (odds ratio [OR] 1.50; 95% CI 1.201.86). Although less frequent, sepsis had the strongest association of any condition with unplanned transfer (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.903.31). However, metabolic, endocrine, and electrolyte conditions were no longer associated with unplanned transfer after adjustment, while arrhythmias and pulmonary embolism were. Other conditions confirmed to be associated with increased risk of unplanned transfer included: myocardial infarction (MI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stroke, diabetic emergencies, catastrophic conditions (includes aortic catastrophes, all forms of shock except septic shock, and intracranial hemorrhage), and acute renal failure. After taking into account the frequency of admitting diagnoses, respiratory conditions (COPD, pneumonia/acute respiratory infection) comprised nearly half (47%) of all conditions associated with increased risk of unplanned ICU transfer.

Other factors confirmed to be independently associated with unplanned ICU transfer included: male sex (OR 1.20; 95% CI 1.131.28), high comorbidity burden as measured by COPS >145 (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.031.24), increasingly abnormal physiology compared to a LAPS <7, and arrival on ward during the overnight shift (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.011.21). After adjustment, we did find that admission to the TCU rather than a medicalsurgical unit was associated with decreased risk of unplanned ICU transfer (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.770.90). Age 85 was associated with decreased risk of unplanned ICU transfer relative to the youngest age group of 1834‐year‐old patients (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.530.77).

ED admissions to higher volume hospitals were 6% less likely to experience an unplanned transfer for each additional 1,000 annual ED hospitalizations over a lower volume hospital (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.910.98). In other words, a patient admitted to a hospital with 8,000 annual ED hospitalizations had 30% decreased odds of unplanned ICU transfer compared to a hospital with only 3,000 annual ED hospitalizations.

DISCUSSION

Patients admitted with respiratory conditions accounted for half of all admitting diagnoses associated with increased risk of unplanned transfer to the ICU within 24 hours of arrival to the ward. We found that 1 in 30 ED ward admissions for pneumonia, and 1 in 33 for COPD, were transferred to the ICU within 24 hours. These findings indicate that there is some room for improvement in early care of respiratory conditions, given the average unplanned transfer rate of 1 in 42, and previous research showing that patients with pneumonia and patients with COPD, who experience unplanned ICU transfer, have substantially worse mortality than those directly admitted to the ICU.1

Although less frequent than hospitalizations for respiratory conditions, patients admitted with sepsis were at the highest risk of unplanned ICU transfer (1 in 17 ED non‐ICU hospitalizations). We also found that MI and stroke ward admissions had a higher risk of unplanned ICU transfer. However, we previously found that unplanned ICU transfers for sepsis, MI, and stroke did not have worse mortality than direct ICU admits for these conditions.1 Therefore, quality improvement efforts to reduce excess mortality related to early decompensation in the hospital and unplanned ICU transfer would be most effective if targeted towards respiratory conditions such as pneumonia and COPD.