User login

Penile Paraffinoma: Dramatic Recurrence After Surgical Resection

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

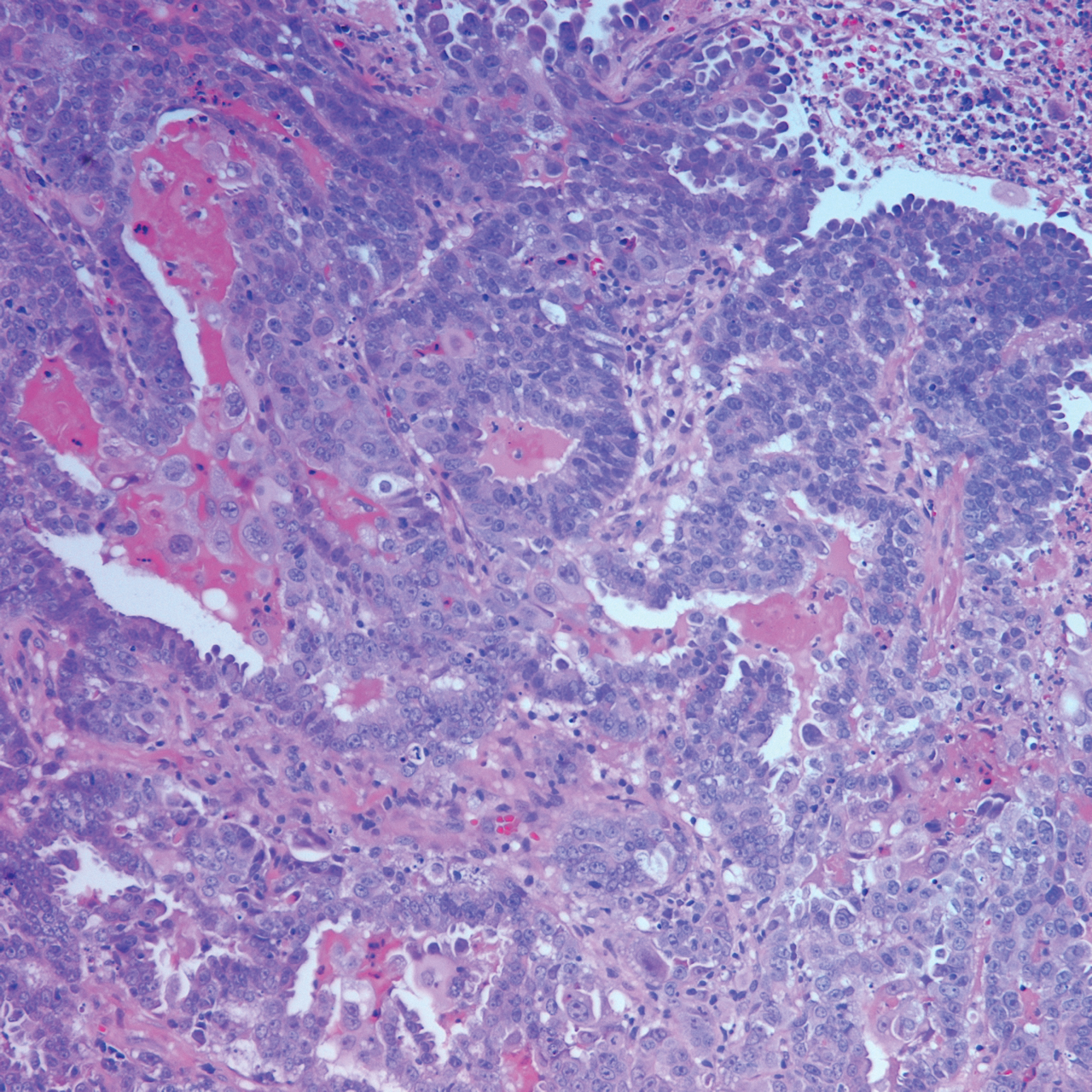

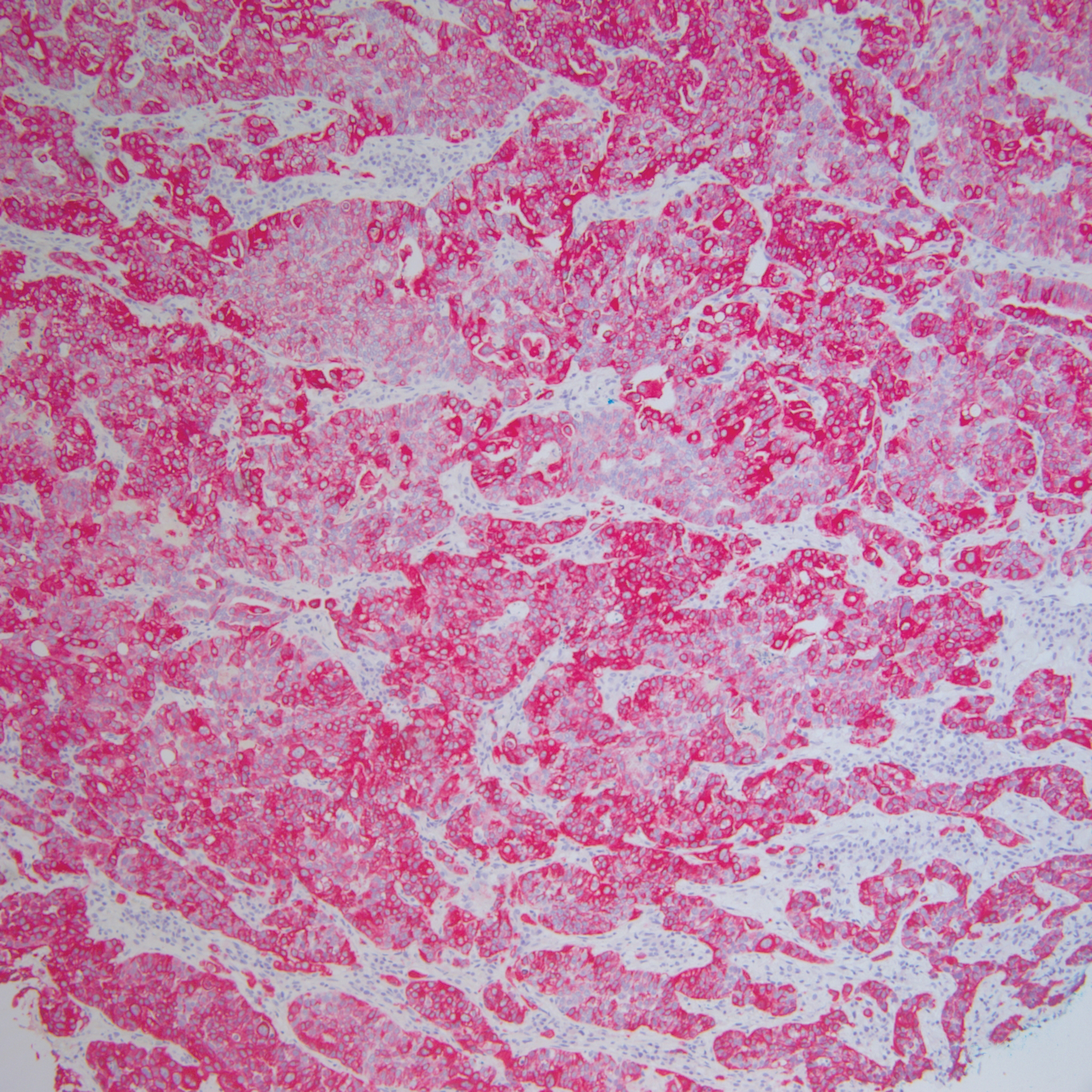

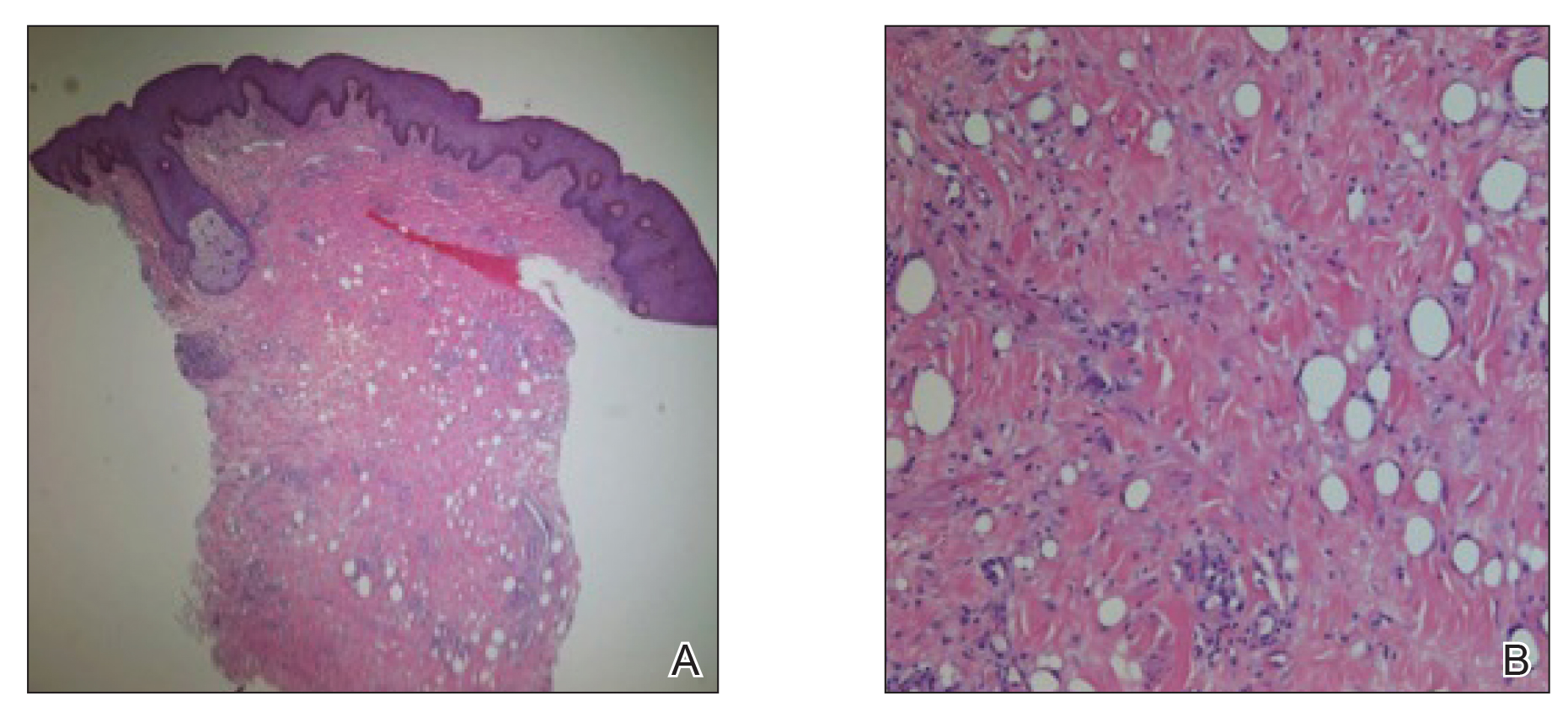

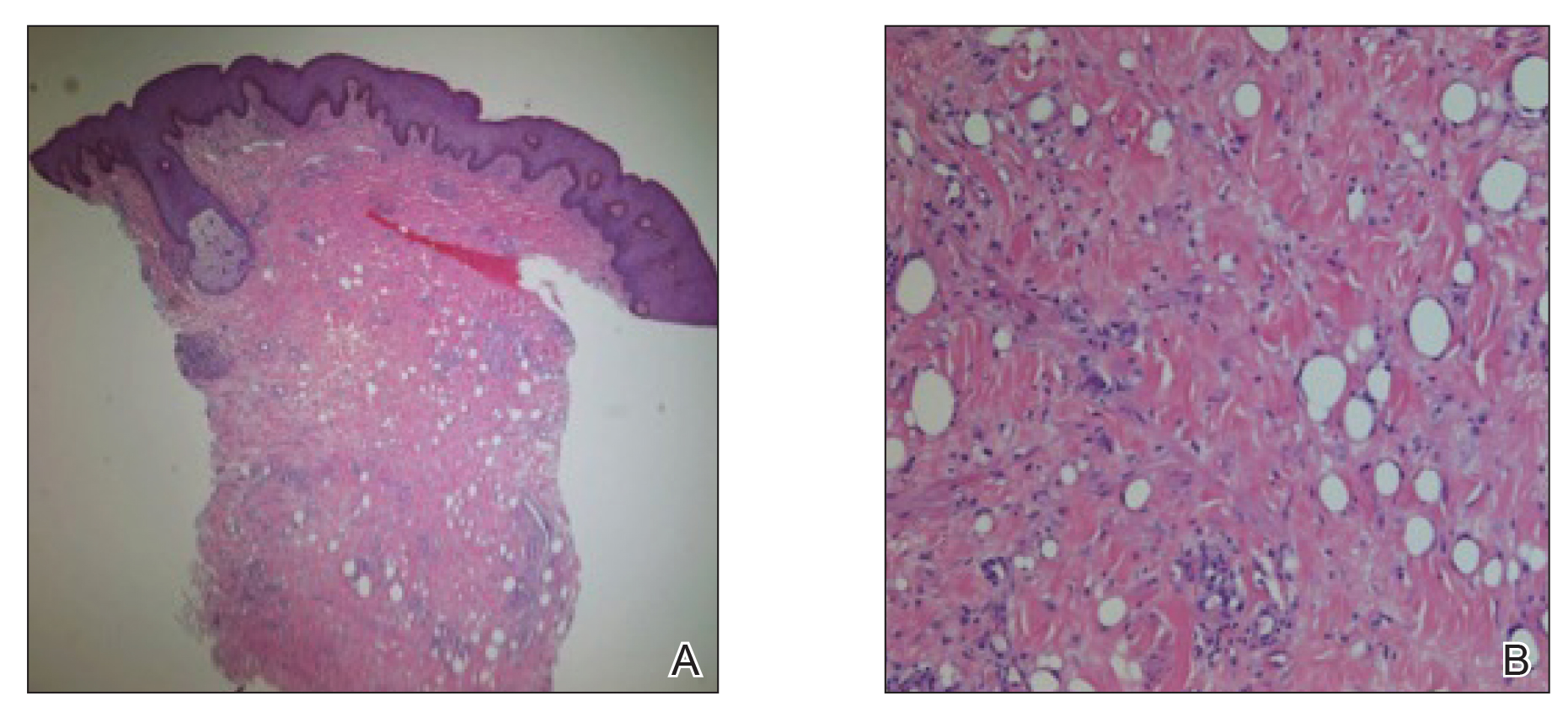

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

To the Editor:

The term paraffinoma refers to a chronic granulomatous response to injection of paraffin, silicone, or other mineral oils into skin and soft tissue. Paraffinomas develop when the material is injected into the skin for cosmetic purposes to augment or enhance one’s appearance. Although they may occur in any location, the most common sites include the breasts and buttocks. The penis is a rare but emerging site for paraffinomas.1-3 We present a rare case of recurrence of a penile paraffinoma following surgical resection.

A 26-year-old uncircumcised Trinidadian man presented with a 5-cm, exquisitely tender tumor involving the penile shaft and median raphe that rapidly evolved over the course of 3 weeks (Figure 1). He presented with inability to urinate, attain an erection, or ambulate without notable tenderness. Additionally, he developed swelling of the penis and surrounding tissue. He had no other medical comorbidities; however, 1 year prior he presented to a urologist with a 1-cm nodule involving the median raphe that was surgically resected and required circumcision. Biopsy at the time of his surgical procedure revealed an exuberant foreign body giant cell reaction with surrounding empty spaces in the dermis resembling Swiss cheese, consistent with a paraffinoma (Figure 2). The recurrent tumor, which was 5 times the size of the initial nodule, was biopsied. Again, histopathologic findings were consistent with a paraffinoma with extensive dermal fibrosis and absence of polarizable material.

The patient underwent extensive reconstructive surgery requiring skin grafting to the penile shaft. Given the size and location of this recurrent tumor with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, consideration for prevention of recurrent episodes included novel therapeutic treatment options to suppress inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.

Paraffin injections are used for cosmetic enhancement and most often occur in a nonclinical setting without medical supervision, as they are not US Food and Drug Administration–approved medical injectable materials. Examples of oils injected include paraffin, camphorated oil, cottonseed or sesame oil, mineral oil, petroleum jelly, and beeswax. These oils are not hydrolyzed by tissue lipases but are instead treated as a foreign body substance with subsequent granuloma formation (also known as sclerosing lipogranuloma), which can occur many years after injection.4 The granulomatous response may be observed months to years after injection. The paraffinoma normally affects the injection site; however, regional lymphadenopathy and systemic disease has been reported.2 Histopathologic findings are characteristic and consist of a foreign body giant cell reaction, variably sized round to oval cavities within the dermis, and varying degrees of dermal fibrosis.5

In 1899, mineral oil was first injected into male genitalia to restore architecture in a patient’s testicles following bilateral orchiectomy. After the success of this endeavor, mineral oil injections were used as filler for other defects.3 However, by 1906 the complications of these injections became public knowledge when 2 patients developed subcutaneous nodules after receiving injections for facial wrinkles.2 Despite public knowledge of these complications, penile paraffin injections continued to occur both in medical and eventually nonmedical settings.

In 1947, Quérnu and Pérol6 described 6 penile paraffinoma cases outside the United States. Patients had petroleum jelly injections that eventuated in penile paraffinomas, and all of them lost the ability to attain an erection.6 Four years later, Bradley and Ehrgott7 described a case of penile paraffinoma likely caused by application of paraffin in association with occupational exposure. In 1956, May and Pickering8 cited a case of penile paraffinoma affecting the entire penile shaft in which the patient had undergone paraffin injection 7 years prior to treat premature ejaculation. Unfortunately, the injection resulted in a painful and unsatisfactory erection without resolution of premature ejaculation.8 Lee et al9 analyzed 26 cases of penile paraffinomas that occurred from 1981 to 1993. They found that all patients underwent injections of paraffin or petroleum jelly performed by nonmedical personnel with the predominant goal of enhancing penis size. Within 18.5 months of injection, 19 patients already experienced tenderness at the injection site. The remaining 7 patients experienced penile skin discoloration and abnormal contouring of the penis. Biopsy specimens revealed hyaline necrosis of subcutaneous adipose septa, cystlike spaces throughout involved tissue, and macrophages engulfing adipose tissue were found near blood vessels.9 In 2007, Eandi et al4 reported a case of penile paraffinoma with a 40-year delay of onset. Four years later, Manny et al10 reported penile paraffinomas in 3 Laotian men who injected a mineral oil.

Currently, paraffin injections are uncommon but still are being performed in some countries in Eastern Europe and the Far East11; they rarely are reported in the United States. Injections can occur in unusual sites such as the knee, and paraffinomas can develop many years after the procedure.12 Additionally, paraffinomas can obscure proper diagnosis of carcinomas, as described by Lee et al13 in a case in which a cervical paraffin injection confounded the diagnosis of a thyroid tumor. Furthermore, these injections usually are performed by nonmedical personnel and typically are repeated multiple times to reach cosmetic goals, rendering the patient vulnerable to early complications including allergic reactions, paraphimosis, infection, and inflammation.3

The clinical presentation of a penile paraffinoma may be a mimicker of several different entities, which are important to consider in the evaluation of a presenting patient. Infectious etiologies must be considered including lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, atypical mycobacteria, lupus vulgaris, and sexually transmitted infections. Importantly, neoplasms must be ruled out including squamous cell carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas, melanoma, adenocarcinoma, or metastasis. Lymphedema, prior surgical procedures, trauma, and inflammatory etiologies also are in the differential diagnosis.14 Nonetheless, physicians must have a high clinical suspicion in the evaluation of a possible paraffinoma, as patients may not be forthcoming with relevant clinical history regarding a prior injection to the affected site, particularly if the injection occurred many years ago. As such, the patient may not consider this history relevant or may not even remember the event occurred, as was observed in our case. Furthermore, embarrassment, social taboo, and stigma may be associated with the behavior of undergoing injections in nonclinical settings without medical supervision.15

Patients may be motivated to undergo dangerous procedures to potentially alter their appearance due to perceived enhanced sexual ability, influence by loved ones, cultural rituals, and societal pressure.15,16 Furthermore, patients may not be aware of the material being injected or the volume. Given that these injections often are used with the goal of cosmetic enhancement, biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration, and a thorough clinical history must support the decision to pursue a biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

The definitive diagnosis of a paraffinoma is determined by histopathology. However, the use of imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography have been employed to delineate the extent of involvement. Imaging studies allow for surgical planning and may assist in narrowing a differential diagnosis.17 Currently, wide and complete surgical resection is the only definitive treatment of paraffinomas, including penile paraffinomas, as there is no evidence of spontaneous regression.3 A report of a reconstructive surgery involving penile resurfacing without T-style anastomosis has been found effective at preventing necrosis of the ventral penile skin. Not all paraffinomas behave similarly, and there is no reliable method to determine which paraffinoma may possess a more aggressive clinical course compared to those which have a more indolent course.18 As such, early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance. In the case of a large penile paraffinoma with the ability to destroy vital urologic and reproductive function, physicians must consider prevention of recurrent episodes through suppression of inflammation and fibrosis with doxycycline and nicotinamide.19 Other medical treatments reported with varying success include corticosteroids, imiquimod, and isotretinoin.19-24 Employing adjunctive medical treatment may decrease the size of the mass, reducing the surgical defect size and preserving tissue vitality. Ultimately, the most crucial aspect in treatment is prevention, as injection of foreign materials elicits a foreign body response and can lead to notable morbidity.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

- De Siati M, Selvaggio O, Di Fino G, et al. An unusual delayed complication of paraffin self-injection for penile girth augmentation. BMC Urol. 2013;13:66.

- Sejben I, Rácz A, Svébis M, et al. Petroleum jelly-induced penile paraffinoma with inguinal lymphadenitis mimicking incarcerated inguinal hernia. Can Urol Assoc J. 2012;6:E137-E139.

- Bayraktar N, Basar I. Penile paraffinoma [published online September 17, 2012]. Case Rep Urol. 2012;2012:202840.

- Eandi JA, Yao AP, Javidan J. Penile paraffinoma: the delayed presentation. Int Urol Nephrol. 2007;29:553-555.

- HirshBCJohnsonWC. Pathology of granulomatous diseases. foreign body granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:531-538.

- Quérnu J, Pérol E. Paraffinomas of the penis. J Chir Par. 1947;63:345.

- Bradley, RH, Ehrgott WA. Paraffinoma of the penis: case report. J Urol. 1951;65:453.

- May JA, Pickering PP. Paraffinoma of the penis. Calif Med. 1956;85:42-44.

Yonsei Med J. 1994;35:344-348. - Lee T, Choi HR, Lee YT, et al. Paraffinoma of the penis.

- Manny T, Pettus J, Hemal A, et al. Penile sclerosing lipogranulomas and disfigurement from use of “1Super Extenze” among Laotian immigrants. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3505-3510.

- Akkus E Paraffinoma and ulcer of the external genitalia after self-injection of vaseline. J Sex Med. 2006;3:170-172.

- Grassetti L, Lazzeri D, Torresetti M, et al. Paraffinoma of the knee 60 years after primary infection. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:789-790.

- Lee YS, Son EJ, Kim BW, et al. Difficult evaluation of thyroid cancer due to cervical paraffin injection. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(suppl 1):S17-S20.

- Gómez-Armayones S, Penín R, Marcoval J. Penile paraffinoma [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:957-959.

- Moon DG, Yoo JW, Bae JH, et al. Sexual function and psychological characteristics of penile paraffinoma. Asian J Androl. 2003;5:191-194.

- Pehlivanov G, Kavaklieva S, Kazandjieva J, et al. Foreign-body granuloma of the penis in sexually active individuals (penile paraffinoma). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:845-851.

- Cormio L, Di Fino G, Scavone C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile paraffinoma: case report. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:39.

- Shin YS, Zhao C, Park JK. New reconstructive surgery for penile paraffinoma to prevent necrosis of ventral penile skin. Urology. 2013;81:437-441.

- Feldmann R, Harms M, Chavaz P, et al. Orbital and palpebral paraffinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:833-835.

- MastruserioDNPesqueiraMJCobbMW. Severe granulomatous reaction and facial ulceration occurring after subcutaneous silicone injection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:849-852.

- HoWS Management of paraffinoma of the breast. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54:232-234.

- LloretPSuccessful treatment of granulomatous reactions secondary to injection of esthetic implants. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:486-490.

- RosenbergEThree cases of penile paraffinoma. Urology. 2007;70:372.

- Baumann LS, Halem ML. Lip silicone granulomatous foreign body reaction treated with Aldara (imiquimod 5%). Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:429-432.

Practice Points

- Taking a thorough history in patients with possible paraffinomas is vital, including a history of injectables even in the genital region.

- Biopsies in cosmetically sensitive areas must be given careful consideration. Clinical history must support the decision to pursue a definitive diagnosis.

- Early detection is critical in the management of paraffinomas, especially in anatomic locations where tissue preservation is of utmost importance.

Cutaneous Metastasis of Endometrial Carcinoma: An Unusual and Dramatic Presentation

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastases of endometrial carcinoma are extremely rare and typically present in areas of direct local spread.

- As with other cutaneous metastases, lesions often are nonspecific, making history and histopathology essential for diagnosis.