User login

Migratory Nodules in a Traveler

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

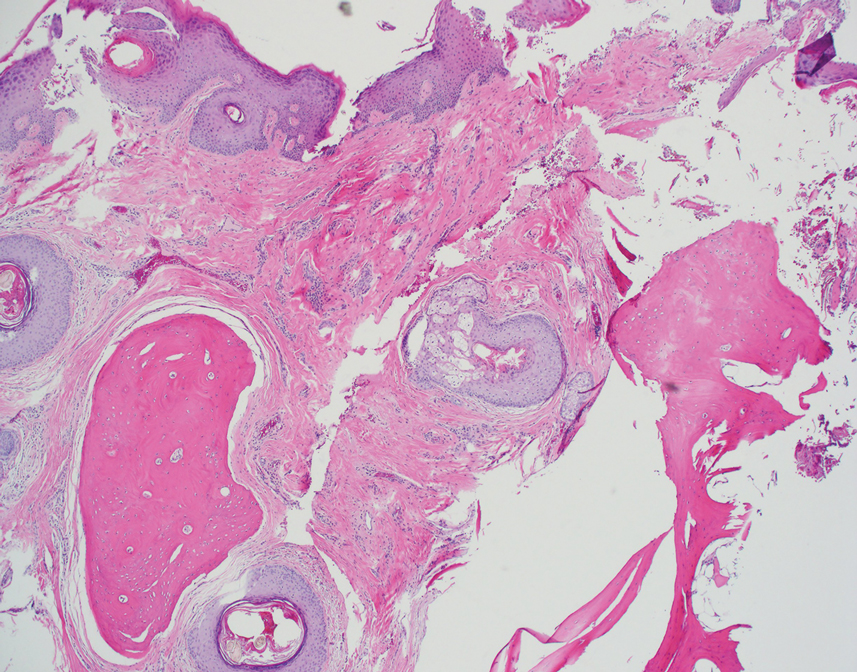

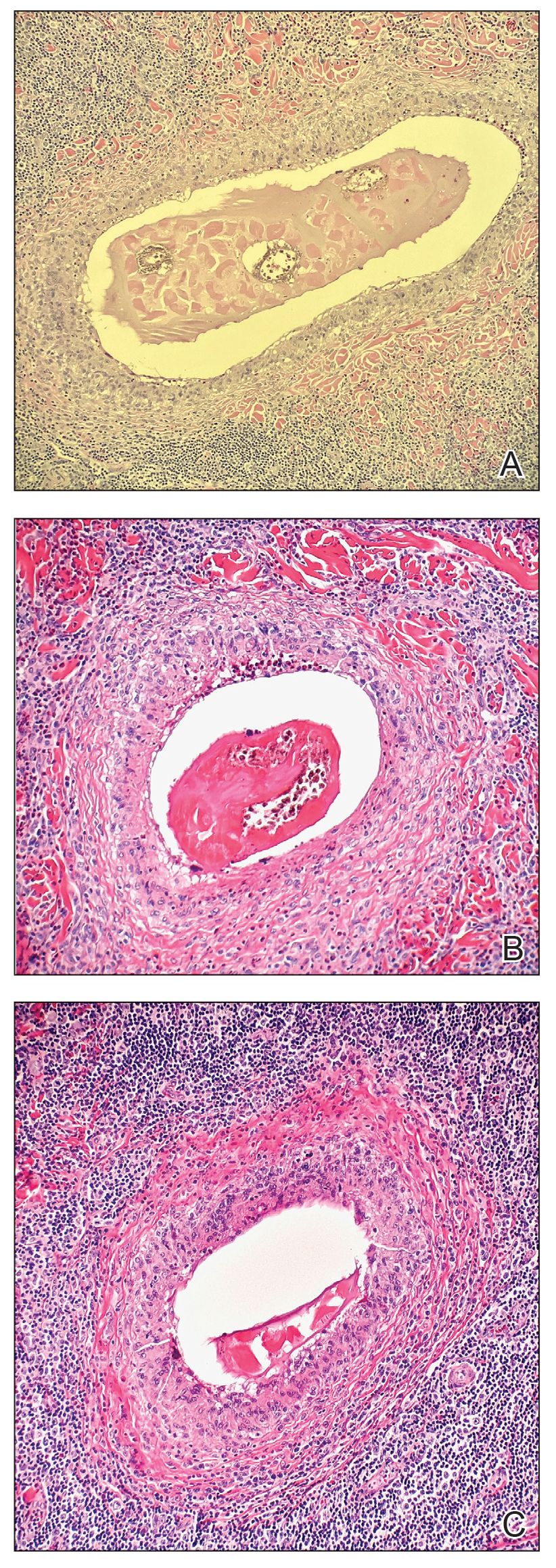

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

The Diagnosis: Gnathostomiasis

The biopsy demonstrated a dense, eosinophilic, granulomatous infiltrate surrounding sections of a parasite with skeletal muscle bundles and intestines containing a brush border and luminal debris (Figure), which was consistent with a diagnosis of gnathostomiasis. Upon further questioning, he revealed that while in Peru he frequently consumed ceviche, which is a dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in lemon or lime juice. He subsequently was treated with oral ivermectin 0.2 mg/kg once daily for 2 days with no evidence of recurrence 12 months later.

Cutaneous gnathostomiasis is the most common manifestation of infection caused by the third-stage larvae of the genus Gnathostoma. The nematode is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions of Japan and Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand. The disease has been increasingly observed in Central and South America. Humans can become infected through ingestion of undercooked meats, particularly freshwater fish but also poultry, snakes, or frogs. Few cases have been reported in North America and Europe presumably due to more stringent regulations governing the sourcing and storage of fish for consumption.1-3 Restaurants in endemic regions also may use cheaper local freshwater or brackish fish compared to restaurants in the West, which use more expensive saltwater fish that do not harbor Gnathostoma species.1 There is a false belief among restauranteurs and consumers that the larvae can be reliably killed by marinating meat in citrus juice or with concurrent consumption of alcohol or hot spices.2 Adequately cooking or freezing meat to 20 °C for 3 to 5 days are the only effective ways to ensure that the larvae are killed.1-3

The parasite requires its natural definitive hosts—fish-eating mammals such as pigs, cats, and dogs—to complete its life cycle and reproduce. Humans are accidental hosts in whom the parasite fails to reach sexual maturity.1-3 Consequently, symptoms commonly are due to the migration of only 1 larva, but occasionally infection with 2 or more has been observed.1,4

Human infection initially may result in malaise, fever, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea as the parasite migrates through the stomach, intestines, and liver. After 2 to 4 weeks, larvae may reach the skin where they most commonly create ill-defined, erythematous, indurated, round or oval plaques or nodules described as nodular migratory panniculitis. These lesions tend to develop on the trunk or arms and correspond to the location of the migrating worm.1,3,5 The larvae have been observed to migrate at 1 cm/h.6 Symptoms often wax and wane, with individual nodules lasting approximately 1 to 2 weeks. Uniquely, larval migration can result in a trail of subcutaneous hemorrhage that is considered pathognomonic and helps to differentiate gnathostomiasis from other forms of parasitosis such as strongyloidiasis and sparganosis.1,3 Larvae are highly motile and invasive, and they are capable of producing a wide range of symptoms affecting virtually any part of the body.1,2 Depending on the anatomic location of the migrating worm, infection also may result in neurologic, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or ocular symptoms.1-3,7 Eosinophilia is common but can subside in the chronic stage, as seen in our patient.1

The classic triad of intermittent migratory nodules, eosinophilia, and a history of travel to Southeast Asia or another endemic region should raise suspicion for gnathostomiasis.1-3,5,7 Unfortunately, confirmatory testing such as Gnathostoma serology is not readily available in the United States, and available serologic tests demonstrate frequent false positives and incomplete crossreactivity.1,2,8 Accordingly, the diagnosis most commonly is solidified by combining cardinal clinical features with histologic findings of a dense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate involving the dermis and hypodermis.2,5 In one study, the larva itself was only found in 12 of 66 (18%) skin biopsy specimens from patients with gnathostomiasis.5 If the larva is detected within the sections, it ranges from 2.5 to 12.5 mm in length and 0.4 to 1.2 mm in width and can exhibit cuticular spines, intestinal cells, and characteristic large lateral chords.1,5

The treatment of choice is surgical removal of the worm. Oral albendazole (400–800 mg/d for 21 days) also is considered a first-line treatment and results in clinical cure in approximately 90% of cases. Two doses of oral ivermectin (0.2 mg/kg) spaced 24 to 48 hours apart is an acceptable alternative with comparable efficacy.1-3 Care should be taken if involvement of the central nervous system is suspected, as antihelminthic treatment theoretically could be deleterious due to an inflammatory response to the dying larvae.1,2,9

In the differential diagnosis, loiasis can resemble gnathostomiasis, but the former is endemic to Africa.3 Cutaneous larva migrans most frequently is caused by hookworms from the genus Ancylostoma, which classically leads to superficial serpiginous linear plaques that migrate at a rate of several millimeters per day. However, the larvae are believed to lack the collagenase enzyme required to penetrate the epidermal basement membrane and thus are not capable of producing deep-seated nodules or visceral symptoms.3Strongyloidiasis (larva currens) generally exhibits a more linear morphology, and infection would result in positive Strongyloides serology.7 Erythema nodosum is a septal panniculitis that can be triggered by infection, pregnancy, medications, connective tissue diseases, inflammatory conditions, and underlying malignancy.10

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

- Herman JS, Chiodini PL. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:484-492.

- Liu GH, Sun MM, Elsheikha HM, et al. Human gnathostomiasis: a neglected food-borne zoonosis. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:616.

- Tyring SK. Gnathostomiasis. In: Tyring SK, Lupi O, Hengge UR, eds. Tropical Dermatology. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2017:77-78.

- Rusnak JM, Lucey DR. Clinical gnathostomiasis: case report and review of the English-language literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:33-50.

- Magaña M, Messina M, Bustamante F, et al. Gnathostomiasis: clinicopathologic study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:91-95.

- Chandenier J, Husson J, Canaple S, et al. Medullary gnathostomiasis in a white patient: use of immunodiagnosis and magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E154-E157.

- Hamilton WL, Agranoff D. Imported gnathostomiasis manifesting as cutaneous larva migrans and Löffler’s syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017223132.

- Neumayr A, Ollague J, Bravo F, et al. Cross-reactivity pattern of Asian and American human gnathostomiasis in western blot assays using crude antigens prepared from Gnathostoma spinigerum and Gnathostoma binucleatum third-stage larvae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95:413-416.

- Kraivichian K, Nuchprayoon S, Sitichalernchai P, et al. Treatment of cutaneous gnathostomiasis with ivermectin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:623-628.

- Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, et al. Erythema nodosum: a practical approach and diagnostic algorithm. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:367-378.

A 41-year-old man presented to a dermatology clinic in the United States with a migratory subcutaneous nodule overlying the left upper chest that initially developed 12 months prior and continued to migrate along the trunk and proximal aspect of the arms. The patient had spent the last 3 years residing in Peru. He never observed more than 1 nodule at a time and denied associated fever, headache, visual changes, chest pain, cough, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Laboratory studies including a blood eosinophil count and serum Strongyloides immunoglobulins were within reference range. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Hard Nodular Plaque on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Platelike Osteoma Cutis

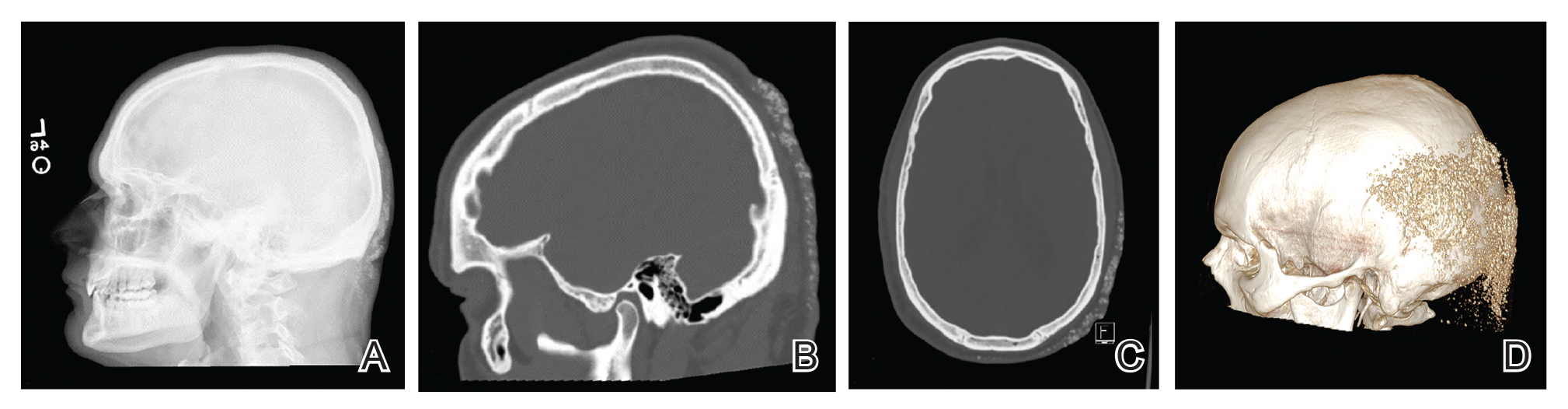

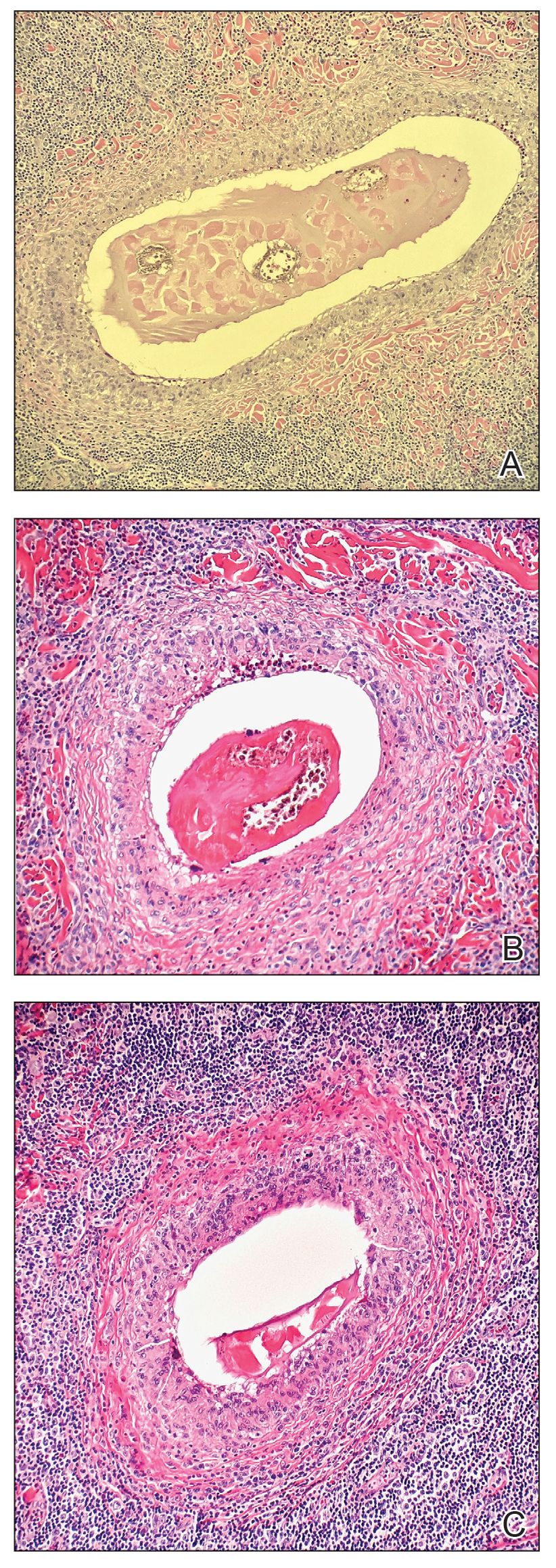

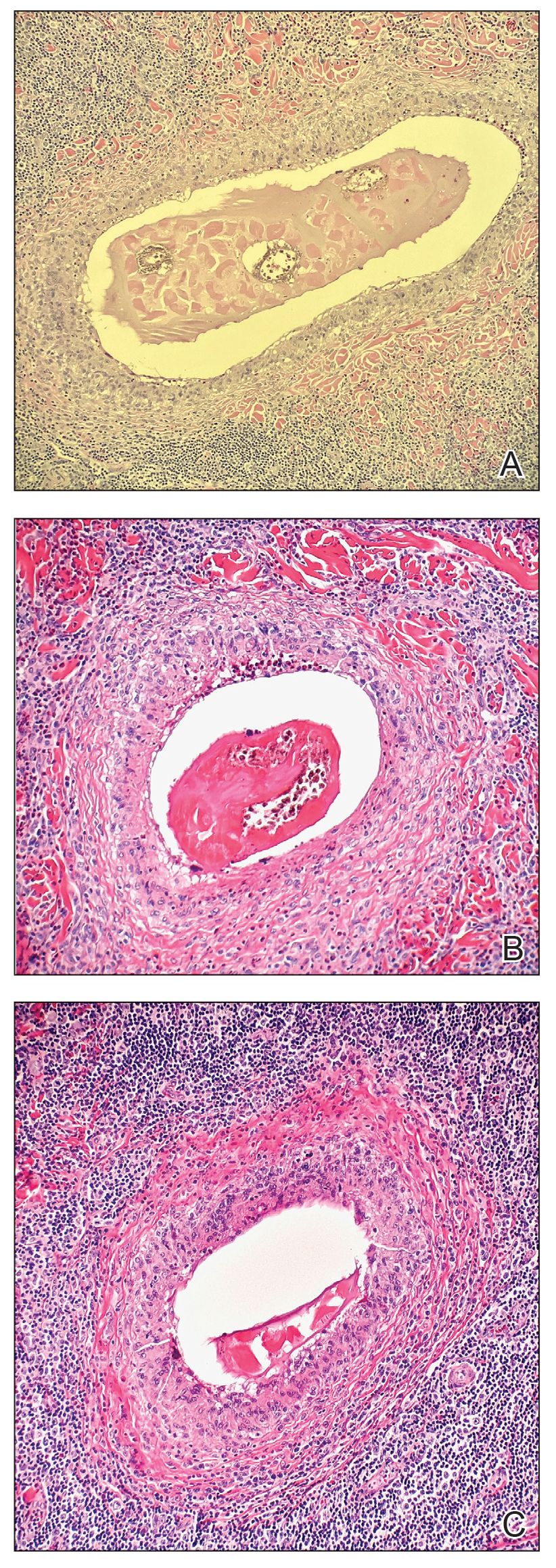

Histopathologic examination revealed extensive cutaneous ossification in the dermis and subcutis with dermal fibrosis and minimal surrounding inflammation (Figure 1). There was no evidence of infection or neoplasm. Further evaluation did not demonstrate any additional physical dysmorphia, and there were no imbalances of calcium-phosphate metabolism or abnormalities in parathyroid hormone or thyroid hormone function. A diagnosis of platelike osteoma cutis (PLOC) was favored. Computed tomography of the head showed material at the posterior skull of similar density to the adjacent calvarial skull and centered within the dermis, consistent with osteoma cutis (Figure 2).

Osteoma cutis describes the formation of bone within the skin. It occurs when hydroxyapatite crystals in a proteinaceous matrix are deposited within the skin, ultimately leading to the formation of bone ultrastructure. Ossification of the skin most often occurs secondary to trauma, inflammation, or neoplasm; however, it rarely may be a primary event.1,2

Platelike osteoma cutis is a rare form of primary cutaneous ossification in which bone forms within the skin in a platelike manner. It most frequently affects the scalp but also has been observed on the trunk and extremities.1 A driving metabolic or endocrine abnormality typically is not identified.2

Platelike osteoma cutis can occur as an isolated finding or as a feature of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) or progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH). In addition to cutaneous ossification, AHO involves short stature, endocrinopathy, obesity, shortened fourth and fifth metacarpals, and mental retardation. Progressive osseous heteroplasia is characterized by progressive ossification of the skin and deeper tissues such as muscle and fascia, leading to severe movement restriction; it is believed to be a localized nonprogressive variant of POH.3,4 Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating activity polypeptide 1 gene, GNAS1, a key regulatory gene involved in AHO and POH, have been found in several cases of PLOC.3 Our patient lacked any dysmorphic features or laboratory abnormalities suggestive of AHO or POH. Moreover, testing of the tissue and blood for the GNAS1 mutation was negative. Treatment of PLOC often is difficult. Our patient underwent a trial of ablative fractional laser resurfacing, which failed to lead to perceivable improvement.

The differential diagnoses include a kerion, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, folliculitis decalvans, and acne keloidalis nuchae. A kerion is a manifestation of tinea capitis characterized by an inflammatory plaque, often with pain or tenderness. Kerions most frequently occur in children aged 5 to 10 years.5 Failure to treat a kerion may result in scarring alopecia. Treatment consists of oral antifungals.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is thought to occur secondary to follicular occlusion. It is characterized by boggy suppurative nodules primarily on the posterior and vertex scalp. Patchy hair loss is present and typically progresses to cicatricial alopecia. Histology characteristically shows areas of dense, predominantly neutrophilic, perifollicular dermal infiltrates.6

Folliculitis decalvans is a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia that primarily occurs in adults. Patients with folliculitis decalvans tend to have multiple pustules on the periphery of confluent areas of scarring alopecia. It is theorized that an immune response to staphylococcal superantigens contributes to this disease process.7

The clinical findings of acne keloidalis nuchae include inflammatory pustules and papules with keloidlike plaques on the posterior neck and scalp. It occurs predominantly in teenaged and adult males of African ancestry.8 Treatment is aimed at reducing inflammation and preventing exacerbating factors. Severe disease courses may lead to scarring alopecia.

- Sanmartín O, Alegre V, Martinez-Aparicio A, et al. Congenital platelike osteoma cutis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:182-186.

- Talsania N, Jolliffe V, O’Toole EA, et al. Platelike osteoma cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;64:613-615.

- Yeh GL, Mathur S, Wivel A, et al. GNAS1 mutation and Cbfa1 misexpression in a child with severe congenital platelike osteoma cutis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2063-2073.

- Hernandez-Martin A, Perez-Mies B, Torrelo A. Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:479-481.

- Zaraa I, Hawilo A, Aounallah A, et al. Inflammatory tinea capitis: a 12-year study and a review of the literature. Mycoses. 2013;56:110-116.

- Scheinfeld N. Dissecting cellulitis (perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens): a comprehensive review focusing on new treatments and findings of the last decade with commentary comparing the therapies and causes of dissecting cellulitis to hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22692.

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574.

The Diagnosis: Platelike Osteoma Cutis

Histopathologic examination revealed extensive cutaneous ossification in the dermis and subcutis with dermal fibrosis and minimal surrounding inflammation (Figure 1). There was no evidence of infection or neoplasm. Further evaluation did not demonstrate any additional physical dysmorphia, and there were no imbalances of calcium-phosphate metabolism or abnormalities in parathyroid hormone or thyroid hormone function. A diagnosis of platelike osteoma cutis (PLOC) was favored. Computed tomography of the head showed material at the posterior skull of similar density to the adjacent calvarial skull and centered within the dermis, consistent with osteoma cutis (Figure 2).

Osteoma cutis describes the formation of bone within the skin. It occurs when hydroxyapatite crystals in a proteinaceous matrix are deposited within the skin, ultimately leading to the formation of bone ultrastructure. Ossification of the skin most often occurs secondary to trauma, inflammation, or neoplasm; however, it rarely may be a primary event.1,2

Platelike osteoma cutis is a rare form of primary cutaneous ossification in which bone forms within the skin in a platelike manner. It most frequently affects the scalp but also has been observed on the trunk and extremities.1 A driving metabolic or endocrine abnormality typically is not identified.2

Platelike osteoma cutis can occur as an isolated finding or as a feature of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) or progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH). In addition to cutaneous ossification, AHO involves short stature, endocrinopathy, obesity, shortened fourth and fifth metacarpals, and mental retardation. Progressive osseous heteroplasia is characterized by progressive ossification of the skin and deeper tissues such as muscle and fascia, leading to severe movement restriction; it is believed to be a localized nonprogressive variant of POH.3,4 Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating activity polypeptide 1 gene, GNAS1, a key regulatory gene involved in AHO and POH, have been found in several cases of PLOC.3 Our patient lacked any dysmorphic features or laboratory abnormalities suggestive of AHO or POH. Moreover, testing of the tissue and blood for the GNAS1 mutation was negative. Treatment of PLOC often is difficult. Our patient underwent a trial of ablative fractional laser resurfacing, which failed to lead to perceivable improvement.

The differential diagnoses include a kerion, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, folliculitis decalvans, and acne keloidalis nuchae. A kerion is a manifestation of tinea capitis characterized by an inflammatory plaque, often with pain or tenderness. Kerions most frequently occur in children aged 5 to 10 years.5 Failure to treat a kerion may result in scarring alopecia. Treatment consists of oral antifungals.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is thought to occur secondary to follicular occlusion. It is characterized by boggy suppurative nodules primarily on the posterior and vertex scalp. Patchy hair loss is present and typically progresses to cicatricial alopecia. Histology characteristically shows areas of dense, predominantly neutrophilic, perifollicular dermal infiltrates.6

Folliculitis decalvans is a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia that primarily occurs in adults. Patients with folliculitis decalvans tend to have multiple pustules on the periphery of confluent areas of scarring alopecia. It is theorized that an immune response to staphylococcal superantigens contributes to this disease process.7

The clinical findings of acne keloidalis nuchae include inflammatory pustules and papules with keloidlike plaques on the posterior neck and scalp. It occurs predominantly in teenaged and adult males of African ancestry.8 Treatment is aimed at reducing inflammation and preventing exacerbating factors. Severe disease courses may lead to scarring alopecia.

The Diagnosis: Platelike Osteoma Cutis

Histopathologic examination revealed extensive cutaneous ossification in the dermis and subcutis with dermal fibrosis and minimal surrounding inflammation (Figure 1). There was no evidence of infection or neoplasm. Further evaluation did not demonstrate any additional physical dysmorphia, and there were no imbalances of calcium-phosphate metabolism or abnormalities in parathyroid hormone or thyroid hormone function. A diagnosis of platelike osteoma cutis (PLOC) was favored. Computed tomography of the head showed material at the posterior skull of similar density to the adjacent calvarial skull and centered within the dermis, consistent with osteoma cutis (Figure 2).

Osteoma cutis describes the formation of bone within the skin. It occurs when hydroxyapatite crystals in a proteinaceous matrix are deposited within the skin, ultimately leading to the formation of bone ultrastructure. Ossification of the skin most often occurs secondary to trauma, inflammation, or neoplasm; however, it rarely may be a primary event.1,2

Platelike osteoma cutis is a rare form of primary cutaneous ossification in which bone forms within the skin in a platelike manner. It most frequently affects the scalp but also has been observed on the trunk and extremities.1 A driving metabolic or endocrine abnormality typically is not identified.2

Platelike osteoma cutis can occur as an isolated finding or as a feature of Albright hereditary osteodystrophy (AHO) or progressive osseous heteroplasia (POH). In addition to cutaneous ossification, AHO involves short stature, endocrinopathy, obesity, shortened fourth and fifth metacarpals, and mental retardation. Progressive osseous heteroplasia is characterized by progressive ossification of the skin and deeper tissues such as muscle and fascia, leading to severe movement restriction; it is believed to be a localized nonprogressive variant of POH.3,4 Mutations in the guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha stimulating activity polypeptide 1 gene, GNAS1, a key regulatory gene involved in AHO and POH, have been found in several cases of PLOC.3 Our patient lacked any dysmorphic features or laboratory abnormalities suggestive of AHO or POH. Moreover, testing of the tissue and blood for the GNAS1 mutation was negative. Treatment of PLOC often is difficult. Our patient underwent a trial of ablative fractional laser resurfacing, which failed to lead to perceivable improvement.

The differential diagnoses include a kerion, dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, folliculitis decalvans, and acne keloidalis nuchae. A kerion is a manifestation of tinea capitis characterized by an inflammatory plaque, often with pain or tenderness. Kerions most frequently occur in children aged 5 to 10 years.5 Failure to treat a kerion may result in scarring alopecia. Treatment consists of oral antifungals.

Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp is thought to occur secondary to follicular occlusion. It is characterized by boggy suppurative nodules primarily on the posterior and vertex scalp. Patchy hair loss is present and typically progresses to cicatricial alopecia. Histology characteristically shows areas of dense, predominantly neutrophilic, perifollicular dermal infiltrates.6

Folliculitis decalvans is a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia that primarily occurs in adults. Patients with folliculitis decalvans tend to have multiple pustules on the periphery of confluent areas of scarring alopecia. It is theorized that an immune response to staphylococcal superantigens contributes to this disease process.7

The clinical findings of acne keloidalis nuchae include inflammatory pustules and papules with keloidlike plaques on the posterior neck and scalp. It occurs predominantly in teenaged and adult males of African ancestry.8 Treatment is aimed at reducing inflammation and preventing exacerbating factors. Severe disease courses may lead to scarring alopecia.

- Sanmartín O, Alegre V, Martinez-Aparicio A, et al. Congenital platelike osteoma cutis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:182-186.

- Talsania N, Jolliffe V, O’Toole EA, et al. Platelike osteoma cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;64:613-615.

- Yeh GL, Mathur S, Wivel A, et al. GNAS1 mutation and Cbfa1 misexpression in a child with severe congenital platelike osteoma cutis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2063-2073.

- Hernandez-Martin A, Perez-Mies B, Torrelo A. Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:479-481.

- Zaraa I, Hawilo A, Aounallah A, et al. Inflammatory tinea capitis: a 12-year study and a review of the literature. Mycoses. 2013;56:110-116.

- Scheinfeld N. Dissecting cellulitis (perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens): a comprehensive review focusing on new treatments and findings of the last decade with commentary comparing the therapies and causes of dissecting cellulitis to hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22692.

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574.

- Sanmartín O, Alegre V, Martinez-Aparicio A, et al. Congenital platelike osteoma cutis: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:182-186.

- Talsania N, Jolliffe V, O’Toole EA, et al. Platelike osteoma cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;64:613-615.

- Yeh GL, Mathur S, Wivel A, et al. GNAS1 mutation and Cbfa1 misexpression in a child with severe congenital platelike osteoma cutis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:2063-2073.

- Hernandez-Martin A, Perez-Mies B, Torrelo A. Congenital plate-like osteoma cutis in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26:479-481.

- Zaraa I, Hawilo A, Aounallah A, et al. Inflammatory tinea capitis: a 12-year study and a review of the literature. Mycoses. 2013;56:110-116.

- Scheinfeld N. Dissecting cellulitis (perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens): a comprehensive review focusing on new treatments and findings of the last decade with commentary comparing the therapies and causes of dissecting cellulitis to hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:22692.

- Ross EK, Tan E, Shapiro J. Update on primary cicatricial alopecias. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1-37.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574.

A 35-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a slow-growing plaque on the scalp of 10 years’ duration. The lesion was mildly pruritic and was never associated with any pain or discharge. He denied antecedent trauma or infection. A hard, erythematous, nodular, alopecic plaque with punctate hyperkeratosis on the left posterior temporal and parietal scalp was noted on physical examination. The lesion was slightly tender to palpation.

Erythematous Abdominal Nodule

The Diagnosis: Foreign Body Reaction With Sinus Tract

A delayed foreign body reaction is a rare complication of retained temporary pacing wires following cardiovascular surgery. These epicardial pacing wires are important for the management of postoperative arrhythmia and normally are removed by external traction after normal rhythm has been re-established. However, it is not uncommon for these wires to be cut at the skin surface in the setting of difficult removal, as retained pacing wires generally are viewed as benign.1 These reactions often take years after placement of the pacing wire to present themselves and most often resolve with either complete removal of the wire or resection of the distal end.2

Our patient was referred to dermatology and underwent a shave biopsy. Results were consistent with chronic inflammatory granulation tissue. Bacterial tissue culture grew Staphylococcus epidermidis. Cultures for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. The patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery. Computed tomography identified a retained temporary pacing wire extending to the base of the lesion. The lesion was excised and the distal aspect of the pacing wire was removed, which resulted in resolution of the nodule.

The differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, nodular basal cell carcinoma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, and pyogenic granuloma. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a rapidly progressing, painful, necrotic ulcer. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease and other systemic diseases but also can occur in isolation.3

Nodular basal cell carcinomas often develop in chronically sun-exposed areas of the body. Morphologically, they present as pink, pearl appearing papules with rolled borders and overlying arborizing telangiectasia. Nodular basal cell carcinomas may present with recurrent bleeding but typically do not have continuous drainage.4

Sister Mary Joseph nodule represents a periumbilical lymphatic metastasis from an underlying (usually intra-abdominal) malignancy. It typically presents as an umbilical or periumbilical nodule measuring 0.5 to 15 cm in diameter. The nodules often are painful and discharge a serous fluid. It is estimated that they are present in 1% to 3% of cases of abdominopelvic malignancy, but Sister Mary Joseph nodules also have been reported in several other types of solid organ tumors.5

Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular lesion that classically develops rapidly over the course of a few weeks. It often presents as a single red, moist, friable papule with a collarette of scale and frequently is associated with pain, bleeding, and ulceration. Keratinized skin or mucosa can be affected, and pyogenic granuloma is most common in children and young adults.6

- Chung DA, Smith EE. Delayed presentation of foreign body reaction secondary to retained pacing wires. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:550-551.

- Gentry WH, Hassan AA. Complications of retained epicardial pacing wires (an unusual bronchial foreign body. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:1391-1393.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13

- Tso S, Brockley J, Recica H, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule: an unusual but important physical finding characteristic of widespread internal malignancy. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:551-552.

- Mashiah J, Hadj-Rabia S, Slodownik D, et al. Effectiveness of topical propranolol 4% gel in the treatment of pyogenic granuloma in children. J Dermatol. 2019;46:245-248.

The Diagnosis: Foreign Body Reaction With Sinus Tract

A delayed foreign body reaction is a rare complication of retained temporary pacing wires following cardiovascular surgery. These epicardial pacing wires are important for the management of postoperative arrhythmia and normally are removed by external traction after normal rhythm has been re-established. However, it is not uncommon for these wires to be cut at the skin surface in the setting of difficult removal, as retained pacing wires generally are viewed as benign.1 These reactions often take years after placement of the pacing wire to present themselves and most often resolve with either complete removal of the wire or resection of the distal end.2

Our patient was referred to dermatology and underwent a shave biopsy. Results were consistent with chronic inflammatory granulation tissue. Bacterial tissue culture grew Staphylococcus epidermidis. Cultures for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. The patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery. Computed tomography identified a retained temporary pacing wire extending to the base of the lesion. The lesion was excised and the distal aspect of the pacing wire was removed, which resulted in resolution of the nodule.

The differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, nodular basal cell carcinoma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, and pyogenic granuloma. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a rapidly progressing, painful, necrotic ulcer. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease and other systemic diseases but also can occur in isolation.3

Nodular basal cell carcinomas often develop in chronically sun-exposed areas of the body. Morphologically, they present as pink, pearl appearing papules with rolled borders and overlying arborizing telangiectasia. Nodular basal cell carcinomas may present with recurrent bleeding but typically do not have continuous drainage.4

Sister Mary Joseph nodule represents a periumbilical lymphatic metastasis from an underlying (usually intra-abdominal) malignancy. It typically presents as an umbilical or periumbilical nodule measuring 0.5 to 15 cm in diameter. The nodules often are painful and discharge a serous fluid. It is estimated that they are present in 1% to 3% of cases of abdominopelvic malignancy, but Sister Mary Joseph nodules also have been reported in several other types of solid organ tumors.5

Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular lesion that classically develops rapidly over the course of a few weeks. It often presents as a single red, moist, friable papule with a collarette of scale and frequently is associated with pain, bleeding, and ulceration. Keratinized skin or mucosa can be affected, and pyogenic granuloma is most common in children and young adults.6

The Diagnosis: Foreign Body Reaction With Sinus Tract

A delayed foreign body reaction is a rare complication of retained temporary pacing wires following cardiovascular surgery. These epicardial pacing wires are important for the management of postoperative arrhythmia and normally are removed by external traction after normal rhythm has been re-established. However, it is not uncommon for these wires to be cut at the skin surface in the setting of difficult removal, as retained pacing wires generally are viewed as benign.1 These reactions often take years after placement of the pacing wire to present themselves and most often resolve with either complete removal of the wire or resection of the distal end.2

Our patient was referred to dermatology and underwent a shave biopsy. Results were consistent with chronic inflammatory granulation tissue. Bacterial tissue culture grew Staphylococcus epidermidis. Cultures for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were negative. The patient was referred to cardiothoracic surgery. Computed tomography identified a retained temporary pacing wire extending to the base of the lesion. The lesion was excised and the distal aspect of the pacing wire was removed, which resulted in resolution of the nodule.

The differential diagnosis includes pyoderma gangrenosum, nodular basal cell carcinoma, Sister Mary Joseph nodule, and pyogenic granuloma. Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as a rapidly progressing, painful, necrotic ulcer. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease and other systemic diseases but also can occur in isolation.3

Nodular basal cell carcinomas often develop in chronically sun-exposed areas of the body. Morphologically, they present as pink, pearl appearing papules with rolled borders and overlying arborizing telangiectasia. Nodular basal cell carcinomas may present with recurrent bleeding but typically do not have continuous drainage.4

Sister Mary Joseph nodule represents a periumbilical lymphatic metastasis from an underlying (usually intra-abdominal) malignancy. It typically presents as an umbilical or periumbilical nodule measuring 0.5 to 15 cm in diameter. The nodules often are painful and discharge a serous fluid. It is estimated that they are present in 1% to 3% of cases of abdominopelvic malignancy, but Sister Mary Joseph nodules also have been reported in several other types of solid organ tumors.5

Pyogenic granuloma is a benign vascular lesion that classically develops rapidly over the course of a few weeks. It often presents as a single red, moist, friable papule with a collarette of scale and frequently is associated with pain, bleeding, and ulceration. Keratinized skin or mucosa can be affected, and pyogenic granuloma is most common in children and young adults.6

- Chung DA, Smith EE. Delayed presentation of foreign body reaction secondary to retained pacing wires. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:550-551.

- Gentry WH, Hassan AA. Complications of retained epicardial pacing wires (an unusual bronchial foreign body. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:1391-1393.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13

- Tso S, Brockley J, Recica H, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule: an unusual but important physical finding characteristic of widespread internal malignancy. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:551-552.

- Mashiah J, Hadj-Rabia S, Slodownik D, et al. Effectiveness of topical propranolol 4% gel in the treatment of pyogenic granuloma in children. J Dermatol. 2019;46:245-248.

- Chung DA, Smith EE. Delayed presentation of foreign body reaction secondary to retained pacing wires. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:550-551.

- Gentry WH, Hassan AA. Complications of retained epicardial pacing wires (an unusual bronchial foreign body. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:1391-1393.

- Ahn C, Negus D, Huang W. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of pathogenesis and treatment. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:225-233.

- Tanese K. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2019;20:13

- Tso S, Brockley J, Recica H, et al. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule: an unusual but important physical finding characteristic of widespread internal malignancy. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:551-552.

- Mashiah J, Hadj-Rabia S, Slodownik D, et al. Effectiveness of topical propranolol 4% gel in the treatment of pyogenic granuloma in children. J Dermatol. 2019;46:245-248.

A 71-year-old man presented with an inflamed erythematous papule on the right subcostal region of 12 months’ duration. It began as a small pimplelike bump that slowly enlarged. The patient did not report any pain or pruritus, but the lesion intermittently drained purulent fluid. The patient had a pacemaker and a history of severe aortic stenosis for which he underwent bioprosthetic aortic valve repair approximately 3 years prior to presentation. His postoperative course was complicated by sternal wound infection and sepsis, prompting surgical replacement of the graft and the pacemaker. He then developed aortitis secondary to bacterial endocarditis with multiple associated septic emboli and is now on lifelong levofloxacin and minocycline therapy. Physical examination revealed a 1.5-cm, erythematous, soft, protuberant nodule with surrounding skin dimpling on the right subcostal region adjacent to a well-healed surgical scar. Approximately 1 to 2 mL of purulent fluid was expressed.