User login

What Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Procedures Should Receive Antibiotic Prophylaxis?

Case

You are asked to admit two patients. The first is a 75-year-old male with a prosthetic aortic valve on warfarin who presents with bright red blood per rectum and is scheduled for colonoscopy. The second patient is a 35-year-old female with biliary obstruction due to choledocholithiasis; she is afebrile with normal vital signs and no leukocytosis. She underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which did not resolve her biliary obstruction. Should you prescribe prophylactic antibiotics for either patient?

Overview

Providers are often confused regarding which patients undergoing gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures should receive antibiotic prophylaxis. To answer this question, it is important to understand the goal of prophylactic antibiotics. Are we trying to prevent infective endocarditis or a localized infection?

There are few large, prospective, randomized controlled trials that have examined the need for antibiotic prophylaxis with GI endoscopic procedures. Guidelines from professional societies are mainly based on expert opinion, evidence from retrospective case studies, and meta-analysis reviews.

Review of the Data

Infective endocarditis resulting from GI endoscopy has been a concern of physicians for decades. The American Heart Association (AHA) first published its recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis of GI tract procedures in 1965. The most recent antibacterial prophylaxis guidelines, published in 2007, have simplified recommendations and greatly scaled back the indications for antibiotics. The new guidelines conclude that frequent bacteremia from daily activities is more likely to precipitate endocarditis than a single dental, GI, or genitourinary tract procedure.1

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) reports that 14.2 million colonoscopies, 2.8 million flexible sigmoidoscopies, and nearly as many upper endoscopies are performed in the U.S. each year, but only 15 cases of endocarditis have been reported with a temporal association to a procedure.2

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) found, after reviewing the histories of patients with infective endocarditis from 1983 through 2006, that there is not enough evidence to warrant antibiotic prophylaxis prior to endoscopy. They noted less than one case of endocarditis after GI endoscopy per year as well as significant variation in the time interval between the procedure and symptoms. The BSG also recognized that antibiotic prophylaxis does not always protect against infection and that clinical factors unrelated to the endoscopy may play a significant role in the development of endocarditis.3

Upper GI Endoscopy, Colonoscopy with Biopsy, and Esophageal Dilatation. Administering antibiotics to prevent infective endocarditis is not recommended for patients undergoing routine procedures such as endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy. Likewise, patients with a history of prosthetic heart valves, valve repair with prosthetic material, endocarditis, congenital heart disease, or cardiac transplant with valvulopathy do not need prophylactic antibiotics before GI endoscopic procedures. However, for patients who are being treated for an active GI infection, antibiotic coverage for enterococcus may be warranted given the increased risk of developing endocarditis. The AHA acknowledges there are no published studies to support the efficacy of antibiotics to prevent enterococcal endocarditis in patients in this clinical setting.1

Unlike routine endoscopy, esophageal dilation is associated with an increased rate of bacteremia (12%-100%).4 Streptococcus viridans has been found in blood cultures up to 79% of the time after esophageal dilation.5 Patients with malignant strictures have higher rates of bacteremia than those with benign strictures (52.9% versus 15.7%). Patients treated with multiple passes with the esophageal dilator compared to those treated with a single dilation have a higher risk of bacteremia.6 All patients undergoing esophageal stricture dilation should receive pre-procedural prophylactic antibiotics.7

Patients with bleeding esophageal varices also have high rates of bacteremia. Up to 20% of patients with cirrhosis and GI bleeding on admission develop an infection within 48 hours of presentation.8 There is evidence that the bacteremia may actually be related to the variceal bleeding rather than the procedure.9 Patients with bleeding esophageal varices treated with antibiotics have improved outcomes, including a decrease in mortality.10 Therefore, all patients with bleeding esophageal varices should be placed on antibiotic therapy regardless of whether an endoscopic intervention is planned.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Placement. Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended before placement of a PEG. The indication for prophylactic antibiotics is to prevent a gastrostomy site infection, not infective endocarditis. Gastrostomy site infection is unfortunately a fairly common infection, affecting 4% to 30% of patients who undergo PEG tube placement. There is significant evidence that antibiotics are beneficial in preventing peristomal infections. A meta-analysis showed that only eight patients need to be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent a single peristomal infection.11 Since these infections are believed to be caused by contamination from the oropharynx, physicians should consider prophylaxis against pathogens from the oral flora.12

More recently, it has been noted that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasingly cultured from infection sites.13 In centers with endemic MRSA, patients should be screened and then undergo decontamination prior to the PEG placement in positive cases.

Endoscopic Ultrasound with Fine Needle Aspiration (EUS-FNA). Antibiotic prophylaxis before EUS-FNA of a solid lesion in an organ is generally thought to be unnecessary because the risk of bacteremia with this procedure is low, comparable to routine GI endoscopy with biopsy. The recommendation for prophylactic antibiotics before biopsy of a cystic lesion is different. There is concern that puncturing cystic lesions may create a new infected fluid collection.2 A systematic review of more than 10,000 patients undergoing EUS-FNA with a full range of target organs revealed that, overall, 11.2% of patients experienced a fever and 4.7% of patients had a peri-procedural infection. While it was not possible in this study to determine which patients received prophylactic antibiotics, 93.7% of patients with pancreatic cystic lesions were reported to have been treated with antibiotics.14

A separate, single-center, retrospective trial produced different results. This study examined a population of 253 patients who underwent 266 EUS-FNA of pancreatic cysts and found that prophylactic antibiotics were associated with more adverse events and were not protective for the 3% of the patients with infectious symptoms.15 Despite the conflicting data, guidelines at this time recommend prophylactic antibiotics before drainage of a sterile pancreatic fluid collection that communicates with the pancreatic duct and also for aspiration of cystic lesions along the GI tract and the mediastinum.2

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In patients undergoing ERCP, the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics has not been found to be effective in decreasing the risk of post-procedure cholangitis.16 Guidelines recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics only in those patients in which the ERCP may not completely resolve the biliary obstruction.2 In these patients, the thought is that ERCP can precipitate infection by disturbing bacteria already present in the biliary tree, especially with increased intrabiliary pressure at the time of contrast dye injection.17

Patients with incomplete biliary drainage, including those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), hilar cholangiocarcinoma, persistent biliary that were not extracted, and strictures that continue to obstruct despite attempted intervention, are thought to be at elevated risk of developing cholangitis post-ERCP. These patients should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the procedure to cover biliary flora such as enteric gram negatives and enterococci. Antibiotics should be continued until the biliary obstruction is resolved.2

Additional Populations to Consider. Previously, the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis recommended that patients on peritoneal dialysis receive prophylactic antibiotics and empty their abdomen of dialysate prior to colonoscopy. This recommendation has been removed from the 2010 guidelines.18 There is also no indication that patients with synthetic vascular grafts or cardiac devices should receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to routine GI endoscopy.19 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons no longer recommends that patients with joint replacements receive antibiotic prophylaxis prior to GI endoscopy.20

Back to the Case

The older gentleman with a prosthetic valve undergoing colonoscopy should not receive prophylactic antibiotics, because even in the setting of valvulopathy, colonoscopy does not pose a significant risk for infective endocarditis. The young patient with severe choledocholithiasis should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics because she has continued biliary obstruction, which could result in a cholangitis after ERCP.

Bottom Line

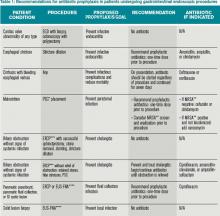

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for any patient undergoing routine endoscopy or colonoscopy. They are indicated for patients with bleeding esophageal varices and for patients who undergo esophageal stricture dilation, PEG placement, or pseudocyst or cyst drainage, and those with continued biliary obstruction undergoing ERCP as summarized in Table 1.

Drs. Ritter, Jupiter, Carbo, and Li are hospitalists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School faculty in Boston.

References

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754.

- Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(6):791-798.

- Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, Simpson IA, Hall RJ, Elliott TS. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58(6):869-880.

- Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: Part I, endogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(4):546-556.

- Zuccaro G Jr., Richter JE, Rice TW, et al. Viridans streptococcal bacteremia after esophageal stricture dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):568-573.

- Nelson DB, Sanderson SJ, Azar MM. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc.1998;48(6):563-567.

- Hirota WK, Petersen K, Baron TH, et al. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(4):475-482.

- Ho H, Zuckerman MJ, Wassem C. A prospective controlled study of the risk of bacteremia in emergency sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(6):1642-1648.

- Rolando N, Gimson A, Philpott-Howard J, et al. Infectious sequelae after endoscopic sclerotherapy of oesophageal varices: Role of antibiotic prophylaxis. J Hepatol. 1993;18(3):290-294.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938.

- Jafri NS, Mahid SS, Minor KS, Idstein SR, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Meta-analysis: Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent peristomal infection following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(6):647-656.

- Chuang CH, Hung KH, Chen JR, et al. Airway infection predisposes to peristomal infection after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with high concordance between sputum and wound isolates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(1):45-51.

- Chaudhary KA, Smith OJ, Cuddy PG, Clarkston WK. PEG site infections: The emergence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a major pathogen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1713-1716.

- Wang KX, Ben QW, Jin ZD, et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: A systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(2):283-290.

- Guarner-Argente C, Shah P, Buchner A, Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG. Use of antimicrobials for EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic cysts: A retrospective, comparative analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):81-86.

- Bai Y, Gao F, Gao J, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot prevent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-induced cholangitis: A meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2009;38(2):126-130.

- Cotton PB, Connor P, Rawls E, Romagnuolo J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: A sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):471-475.

- Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(4):393-423.

- Baddour LM, Bettmann MA, Bolger AF, et al. Nonvalvular cardiovascular device-related infections. Circulation. 2003;108(16):2015-2031.

- Rethman MP, Watters W III, Abt E, et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Dental Association clinical practice guideline on the prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):745-747.

Case

You are asked to admit two patients. The first is a 75-year-old male with a prosthetic aortic valve on warfarin who presents with bright red blood per rectum and is scheduled for colonoscopy. The second patient is a 35-year-old female with biliary obstruction due to choledocholithiasis; she is afebrile with normal vital signs and no leukocytosis. She underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which did not resolve her biliary obstruction. Should you prescribe prophylactic antibiotics for either patient?

Overview

Providers are often confused regarding which patients undergoing gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures should receive antibiotic prophylaxis. To answer this question, it is important to understand the goal of prophylactic antibiotics. Are we trying to prevent infective endocarditis or a localized infection?

There are few large, prospective, randomized controlled trials that have examined the need for antibiotic prophylaxis with GI endoscopic procedures. Guidelines from professional societies are mainly based on expert opinion, evidence from retrospective case studies, and meta-analysis reviews.

Review of the Data

Infective endocarditis resulting from GI endoscopy has been a concern of physicians for decades. The American Heart Association (AHA) first published its recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis of GI tract procedures in 1965. The most recent antibacterial prophylaxis guidelines, published in 2007, have simplified recommendations and greatly scaled back the indications for antibiotics. The new guidelines conclude that frequent bacteremia from daily activities is more likely to precipitate endocarditis than a single dental, GI, or genitourinary tract procedure.1

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) reports that 14.2 million colonoscopies, 2.8 million flexible sigmoidoscopies, and nearly as many upper endoscopies are performed in the U.S. each year, but only 15 cases of endocarditis have been reported with a temporal association to a procedure.2

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) found, after reviewing the histories of patients with infective endocarditis from 1983 through 2006, that there is not enough evidence to warrant antibiotic prophylaxis prior to endoscopy. They noted less than one case of endocarditis after GI endoscopy per year as well as significant variation in the time interval between the procedure and symptoms. The BSG also recognized that antibiotic prophylaxis does not always protect against infection and that clinical factors unrelated to the endoscopy may play a significant role in the development of endocarditis.3

Upper GI Endoscopy, Colonoscopy with Biopsy, and Esophageal Dilatation. Administering antibiotics to prevent infective endocarditis is not recommended for patients undergoing routine procedures such as endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy. Likewise, patients with a history of prosthetic heart valves, valve repair with prosthetic material, endocarditis, congenital heart disease, or cardiac transplant with valvulopathy do not need prophylactic antibiotics before GI endoscopic procedures. However, for patients who are being treated for an active GI infection, antibiotic coverage for enterococcus may be warranted given the increased risk of developing endocarditis. The AHA acknowledges there are no published studies to support the efficacy of antibiotics to prevent enterococcal endocarditis in patients in this clinical setting.1

Unlike routine endoscopy, esophageal dilation is associated with an increased rate of bacteremia (12%-100%).4 Streptococcus viridans has been found in blood cultures up to 79% of the time after esophageal dilation.5 Patients with malignant strictures have higher rates of bacteremia than those with benign strictures (52.9% versus 15.7%). Patients treated with multiple passes with the esophageal dilator compared to those treated with a single dilation have a higher risk of bacteremia.6 All patients undergoing esophageal stricture dilation should receive pre-procedural prophylactic antibiotics.7

Patients with bleeding esophageal varices also have high rates of bacteremia. Up to 20% of patients with cirrhosis and GI bleeding on admission develop an infection within 48 hours of presentation.8 There is evidence that the bacteremia may actually be related to the variceal bleeding rather than the procedure.9 Patients with bleeding esophageal varices treated with antibiotics have improved outcomes, including a decrease in mortality.10 Therefore, all patients with bleeding esophageal varices should be placed on antibiotic therapy regardless of whether an endoscopic intervention is planned.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Placement. Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended before placement of a PEG. The indication for prophylactic antibiotics is to prevent a gastrostomy site infection, not infective endocarditis. Gastrostomy site infection is unfortunately a fairly common infection, affecting 4% to 30% of patients who undergo PEG tube placement. There is significant evidence that antibiotics are beneficial in preventing peristomal infections. A meta-analysis showed that only eight patients need to be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent a single peristomal infection.11 Since these infections are believed to be caused by contamination from the oropharynx, physicians should consider prophylaxis against pathogens from the oral flora.12

More recently, it has been noted that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasingly cultured from infection sites.13 In centers with endemic MRSA, patients should be screened and then undergo decontamination prior to the PEG placement in positive cases.

Endoscopic Ultrasound with Fine Needle Aspiration (EUS-FNA). Antibiotic prophylaxis before EUS-FNA of a solid lesion in an organ is generally thought to be unnecessary because the risk of bacteremia with this procedure is low, comparable to routine GI endoscopy with biopsy. The recommendation for prophylactic antibiotics before biopsy of a cystic lesion is different. There is concern that puncturing cystic lesions may create a new infected fluid collection.2 A systematic review of more than 10,000 patients undergoing EUS-FNA with a full range of target organs revealed that, overall, 11.2% of patients experienced a fever and 4.7% of patients had a peri-procedural infection. While it was not possible in this study to determine which patients received prophylactic antibiotics, 93.7% of patients with pancreatic cystic lesions were reported to have been treated with antibiotics.14

A separate, single-center, retrospective trial produced different results. This study examined a population of 253 patients who underwent 266 EUS-FNA of pancreatic cysts and found that prophylactic antibiotics were associated with more adverse events and were not protective for the 3% of the patients with infectious symptoms.15 Despite the conflicting data, guidelines at this time recommend prophylactic antibiotics before drainage of a sterile pancreatic fluid collection that communicates with the pancreatic duct and also for aspiration of cystic lesions along the GI tract and the mediastinum.2

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In patients undergoing ERCP, the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics has not been found to be effective in decreasing the risk of post-procedure cholangitis.16 Guidelines recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics only in those patients in which the ERCP may not completely resolve the biliary obstruction.2 In these patients, the thought is that ERCP can precipitate infection by disturbing bacteria already present in the biliary tree, especially with increased intrabiliary pressure at the time of contrast dye injection.17

Patients with incomplete biliary drainage, including those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), hilar cholangiocarcinoma, persistent biliary that were not extracted, and strictures that continue to obstruct despite attempted intervention, are thought to be at elevated risk of developing cholangitis post-ERCP. These patients should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the procedure to cover biliary flora such as enteric gram negatives and enterococci. Antibiotics should be continued until the biliary obstruction is resolved.2

Additional Populations to Consider. Previously, the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis recommended that patients on peritoneal dialysis receive prophylactic antibiotics and empty their abdomen of dialysate prior to colonoscopy. This recommendation has been removed from the 2010 guidelines.18 There is also no indication that patients with synthetic vascular grafts or cardiac devices should receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to routine GI endoscopy.19 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons no longer recommends that patients with joint replacements receive antibiotic prophylaxis prior to GI endoscopy.20

Back to the Case

The older gentleman with a prosthetic valve undergoing colonoscopy should not receive prophylactic antibiotics, because even in the setting of valvulopathy, colonoscopy does not pose a significant risk for infective endocarditis. The young patient with severe choledocholithiasis should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics because she has continued biliary obstruction, which could result in a cholangitis after ERCP.

Bottom Line

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for any patient undergoing routine endoscopy or colonoscopy. They are indicated for patients with bleeding esophageal varices and for patients who undergo esophageal stricture dilation, PEG placement, or pseudocyst or cyst drainage, and those with continued biliary obstruction undergoing ERCP as summarized in Table 1.

Drs. Ritter, Jupiter, Carbo, and Li are hospitalists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School faculty in Boston.

References

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754.

- Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(6):791-798.

- Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, Simpson IA, Hall RJ, Elliott TS. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58(6):869-880.

- Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: Part I, endogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(4):546-556.

- Zuccaro G Jr., Richter JE, Rice TW, et al. Viridans streptococcal bacteremia after esophageal stricture dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):568-573.

- Nelson DB, Sanderson SJ, Azar MM. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc.1998;48(6):563-567.

- Hirota WK, Petersen K, Baron TH, et al. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(4):475-482.

- Ho H, Zuckerman MJ, Wassem C. A prospective controlled study of the risk of bacteremia in emergency sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(6):1642-1648.

- Rolando N, Gimson A, Philpott-Howard J, et al. Infectious sequelae after endoscopic sclerotherapy of oesophageal varices: Role of antibiotic prophylaxis. J Hepatol. 1993;18(3):290-294.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938.

- Jafri NS, Mahid SS, Minor KS, Idstein SR, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Meta-analysis: Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent peristomal infection following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(6):647-656.

- Chuang CH, Hung KH, Chen JR, et al. Airway infection predisposes to peristomal infection after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with high concordance between sputum and wound isolates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(1):45-51.

- Chaudhary KA, Smith OJ, Cuddy PG, Clarkston WK. PEG site infections: The emergence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a major pathogen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1713-1716.

- Wang KX, Ben QW, Jin ZD, et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: A systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(2):283-290.

- Guarner-Argente C, Shah P, Buchner A, Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG. Use of antimicrobials for EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic cysts: A retrospective, comparative analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):81-86.

- Bai Y, Gao F, Gao J, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot prevent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-induced cholangitis: A meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2009;38(2):126-130.

- Cotton PB, Connor P, Rawls E, Romagnuolo J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: A sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):471-475.

- Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(4):393-423.

- Baddour LM, Bettmann MA, Bolger AF, et al. Nonvalvular cardiovascular device-related infections. Circulation. 2003;108(16):2015-2031.

- Rethman MP, Watters W III, Abt E, et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Dental Association clinical practice guideline on the prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):745-747.

Case

You are asked to admit two patients. The first is a 75-year-old male with a prosthetic aortic valve on warfarin who presents with bright red blood per rectum and is scheduled for colonoscopy. The second patient is a 35-year-old female with biliary obstruction due to choledocholithiasis; she is afebrile with normal vital signs and no leukocytosis. She underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which did not resolve her biliary obstruction. Should you prescribe prophylactic antibiotics for either patient?

Overview

Providers are often confused regarding which patients undergoing gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures should receive antibiotic prophylaxis. To answer this question, it is important to understand the goal of prophylactic antibiotics. Are we trying to prevent infective endocarditis or a localized infection?

There are few large, prospective, randomized controlled trials that have examined the need for antibiotic prophylaxis with GI endoscopic procedures. Guidelines from professional societies are mainly based on expert opinion, evidence from retrospective case studies, and meta-analysis reviews.

Review of the Data

Infective endocarditis resulting from GI endoscopy has been a concern of physicians for decades. The American Heart Association (AHA) first published its recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis of GI tract procedures in 1965. The most recent antibacterial prophylaxis guidelines, published in 2007, have simplified recommendations and greatly scaled back the indications for antibiotics. The new guidelines conclude that frequent bacteremia from daily activities is more likely to precipitate endocarditis than a single dental, GI, or genitourinary tract procedure.1

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) reports that 14.2 million colonoscopies, 2.8 million flexible sigmoidoscopies, and nearly as many upper endoscopies are performed in the U.S. each year, but only 15 cases of endocarditis have been reported with a temporal association to a procedure.2

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) found, after reviewing the histories of patients with infective endocarditis from 1983 through 2006, that there is not enough evidence to warrant antibiotic prophylaxis prior to endoscopy. They noted less than one case of endocarditis after GI endoscopy per year as well as significant variation in the time interval between the procedure and symptoms. The BSG also recognized that antibiotic prophylaxis does not always protect against infection and that clinical factors unrelated to the endoscopy may play a significant role in the development of endocarditis.3

Upper GI Endoscopy, Colonoscopy with Biopsy, and Esophageal Dilatation. Administering antibiotics to prevent infective endocarditis is not recommended for patients undergoing routine procedures such as endoscopy with biopsy and colonoscopy with polypectomy. Likewise, patients with a history of prosthetic heart valves, valve repair with prosthetic material, endocarditis, congenital heart disease, or cardiac transplant with valvulopathy do not need prophylactic antibiotics before GI endoscopic procedures. However, for patients who are being treated for an active GI infection, antibiotic coverage for enterococcus may be warranted given the increased risk of developing endocarditis. The AHA acknowledges there are no published studies to support the efficacy of antibiotics to prevent enterococcal endocarditis in patients in this clinical setting.1

Unlike routine endoscopy, esophageal dilation is associated with an increased rate of bacteremia (12%-100%).4 Streptococcus viridans has been found in blood cultures up to 79% of the time after esophageal dilation.5 Patients with malignant strictures have higher rates of bacteremia than those with benign strictures (52.9% versus 15.7%). Patients treated with multiple passes with the esophageal dilator compared to those treated with a single dilation have a higher risk of bacteremia.6 All patients undergoing esophageal stricture dilation should receive pre-procedural prophylactic antibiotics.7

Patients with bleeding esophageal varices also have high rates of bacteremia. Up to 20% of patients with cirrhosis and GI bleeding on admission develop an infection within 48 hours of presentation.8 There is evidence that the bacteremia may actually be related to the variceal bleeding rather than the procedure.9 Patients with bleeding esophageal varices treated with antibiotics have improved outcomes, including a decrease in mortality.10 Therefore, all patients with bleeding esophageal varices should be placed on antibiotic therapy regardless of whether an endoscopic intervention is planned.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) Placement. Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended before placement of a PEG. The indication for prophylactic antibiotics is to prevent a gastrostomy site infection, not infective endocarditis. Gastrostomy site infection is unfortunately a fairly common infection, affecting 4% to 30% of patients who undergo PEG tube placement. There is significant evidence that antibiotics are beneficial in preventing peristomal infections. A meta-analysis showed that only eight patients need to be treated with prophylactic antibiotics to prevent a single peristomal infection.11 Since these infections are believed to be caused by contamination from the oropharynx, physicians should consider prophylaxis against pathogens from the oral flora.12

More recently, it has been noted that methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is increasingly cultured from infection sites.13 In centers with endemic MRSA, patients should be screened and then undergo decontamination prior to the PEG placement in positive cases.

Endoscopic Ultrasound with Fine Needle Aspiration (EUS-FNA). Antibiotic prophylaxis before EUS-FNA of a solid lesion in an organ is generally thought to be unnecessary because the risk of bacteremia with this procedure is low, comparable to routine GI endoscopy with biopsy. The recommendation for prophylactic antibiotics before biopsy of a cystic lesion is different. There is concern that puncturing cystic lesions may create a new infected fluid collection.2 A systematic review of more than 10,000 patients undergoing EUS-FNA with a full range of target organs revealed that, overall, 11.2% of patients experienced a fever and 4.7% of patients had a peri-procedural infection. While it was not possible in this study to determine which patients received prophylactic antibiotics, 93.7% of patients with pancreatic cystic lesions were reported to have been treated with antibiotics.14

A separate, single-center, retrospective trial produced different results. This study examined a population of 253 patients who underwent 266 EUS-FNA of pancreatic cysts and found that prophylactic antibiotics were associated with more adverse events and were not protective for the 3% of the patients with infectious symptoms.15 Despite the conflicting data, guidelines at this time recommend prophylactic antibiotics before drainage of a sterile pancreatic fluid collection that communicates with the pancreatic duct and also for aspiration of cystic lesions along the GI tract and the mediastinum.2

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). In patients undergoing ERCP, the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics has not been found to be effective in decreasing the risk of post-procedure cholangitis.16 Guidelines recommend the use of prophylactic antibiotics only in those patients in which the ERCP may not completely resolve the biliary obstruction.2 In these patients, the thought is that ERCP can precipitate infection by disturbing bacteria already present in the biliary tree, especially with increased intrabiliary pressure at the time of contrast dye injection.17

Patients with incomplete biliary drainage, including those with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), hilar cholangiocarcinoma, persistent biliary that were not extracted, and strictures that continue to obstruct despite attempted intervention, are thought to be at elevated risk of developing cholangitis post-ERCP. These patients should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics at the time of the procedure to cover biliary flora such as enteric gram negatives and enterococci. Antibiotics should be continued until the biliary obstruction is resolved.2

Additional Populations to Consider. Previously, the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis recommended that patients on peritoneal dialysis receive prophylactic antibiotics and empty their abdomen of dialysate prior to colonoscopy. This recommendation has been removed from the 2010 guidelines.18 There is also no indication that patients with synthetic vascular grafts or cardiac devices should receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to routine GI endoscopy.19 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons no longer recommends that patients with joint replacements receive antibiotic prophylaxis prior to GI endoscopy.20

Back to the Case

The older gentleman with a prosthetic valve undergoing colonoscopy should not receive prophylactic antibiotics, because even in the setting of valvulopathy, colonoscopy does not pose a significant risk for infective endocarditis. The young patient with severe choledocholithiasis should be placed on prophylactic antibiotics because she has continued biliary obstruction, which could result in a cholangitis after ERCP.

Bottom Line

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for any patient undergoing routine endoscopy or colonoscopy. They are indicated for patients with bleeding esophageal varices and for patients who undergo esophageal stricture dilation, PEG placement, or pseudocyst or cyst drainage, and those with continued biliary obstruction undergoing ERCP as summarized in Table 1.

Drs. Ritter, Jupiter, Carbo, and Li are hospitalists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School faculty in Boston.

References

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736-1754.

- Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(6):791-798.

- Allison MC, Sandoe JA, Tighe R, Simpson IA, Hall RJ, Elliott TS. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gut. 2009;58(6):869-880.

- Nelson DB. Infectious disease complications of GI endoscopy: Part I, endogenous infections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(4):546-556.

- Zuccaro G Jr., Richter JE, Rice TW, et al. Viridans streptococcal bacteremia after esophageal stricture dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):568-573.

- Nelson DB, Sanderson SJ, Azar MM. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc.1998;48(6):563-567.

- Hirota WK, Petersen K, Baron TH, et al. Guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(4):475-482.

- Ho H, Zuckerman MJ, Wassem C. A prospective controlled study of the risk of bacteremia in emergency sclerotherapy of esophageal varices. Gastroenterology. 1991;101(6):1642-1648.

- Rolando N, Gimson A, Philpott-Howard J, et al. Infectious sequelae after endoscopic sclerotherapy of oesophageal varices: Role of antibiotic prophylaxis. J Hepatol. 1993;18(3):290-294.

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922-938.

- Jafri NS, Mahid SS, Minor KS, Idstein SR, Hornung CA, Galandiuk S. Meta-analysis: Antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent peristomal infection following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(6):647-656.

- Chuang CH, Hung KH, Chen JR, et al. Airway infection predisposes to peristomal infection after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with high concordance between sputum and wound isolates. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(1):45-51.

- Chaudhary KA, Smith OJ, Cuddy PG, Clarkston WK. PEG site infections: The emergence of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a major pathogen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1713-1716.

- Wang KX, Ben QW, Jin ZD, et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: A systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(2):283-290.

- Guarner-Argente C, Shah P, Buchner A, Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Ginsberg GG. Use of antimicrobials for EUS-guided FNA of pancreatic cysts: A retrospective, comparative analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):81-86.

- Bai Y, Gao F, Gao J, Zou DW, Li ZS. Prophylactic antibiotics cannot prevent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-induced cholangitis: A meta-analysis. Pancreas. 2009;38(2):126-130.

- Cotton PB, Connor P, Rawls E, Romagnuolo J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: A sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(3):471-475.

- Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30(4):393-423.

- Baddour LM, Bettmann MA, Bolger AF, et al. Nonvalvular cardiovascular device-related infections. Circulation. 2003;108(16):2015-2031.

- Rethman MP, Watters W III, Abt E, et al. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the American Dental Association clinical practice guideline on the prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):745-747.

CMS Allows Residents, Advanced Practitioners to Admit Inpatients

A federal rule that some hospitalists feared would bar nonstaff physicians from writing admission orders for hospital inpatients has been clarified to extend those privileges to resident physicians and advanced practitioners.

On Aug. 19, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its fiscal 2014 hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule, which is effective Oct. 1. Although this document impacts a number of important areas for hospitals, including the use of inpatient admission and observation status, hospitalists also were left with the impression that resident physicians and advanced practitioners (NPs and PAs) were being barred from writing admission orders.

Medical residents, NPs, and PAs do not have admitting privileges in most hospitals, and their inability to write admission orders would pose significant logistical and financial hurdles for many hospitals and physician groups, including hospitalists.

In most academic centers, residents have the opportunity and responsibility to evaluate patients at the time of hospitalization, write initial hospitalization orders, and then discuss patients with the attending physician. The "staffing" of patients typically occurs either later the same day or the following morning. The provision requiring an attending physician knowledgeable of the case to furnish the admission order, and not allowing delegation of this order to their residents, could fundamentally change the way our physicians are trained.

Many hospitals rely on NPs and PAs for the care of hospitalized patients under the supervision of a staff physician. These nonphysician providers often care for hospitalized patients, admit patients, and provide overnight coverage. Requiring admission orders to be placed by physicians with admitting privileges would require a greater presence of staff physicians, which would increase costs.

Some of these concerns were voiced Aug. 15 on CMS' Special Open Door Forum on CMS Rule 1599-F. While clarification was not offered, it was indicated that CMS did not intend to place such limitations on residents, NPs, and PAs. On Sept. 5, CMS released clarifications to some of these provisions in the IPPS Final Rule, and noted that admission orders may come from a physician or other practitioner.

This clarification suggests that when a resident, NP, or PA writes admission orders, they are doing so at the direction of a physician with admitting privileges. This may occur in the form of a verbal order, which requires documentation of the name of the admitting physician, as well as the date and time of the verbal order. This verbal order must then be countersigned by a qualified physician prior to patient discharge.

Failures to obtain appropriate orders co-signed by an appropriate physician are likely at high risk for Medicare payment denial. This clarification appears to address previously held concerns about this new rule.

A federal rule that some hospitalists feared would bar nonstaff physicians from writing admission orders for hospital inpatients has been clarified to extend those privileges to resident physicians and advanced practitioners.

On Aug. 19, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its fiscal 2014 hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule, which is effective Oct. 1. Although this document impacts a number of important areas for hospitals, including the use of inpatient admission and observation status, hospitalists also were left with the impression that resident physicians and advanced practitioners (NPs and PAs) were being barred from writing admission orders.

Medical residents, NPs, and PAs do not have admitting privileges in most hospitals, and their inability to write admission orders would pose significant logistical and financial hurdles for many hospitals and physician groups, including hospitalists.

In most academic centers, residents have the opportunity and responsibility to evaluate patients at the time of hospitalization, write initial hospitalization orders, and then discuss patients with the attending physician. The "staffing" of patients typically occurs either later the same day or the following morning. The provision requiring an attending physician knowledgeable of the case to furnish the admission order, and not allowing delegation of this order to their residents, could fundamentally change the way our physicians are trained.

Many hospitals rely on NPs and PAs for the care of hospitalized patients under the supervision of a staff physician. These nonphysician providers often care for hospitalized patients, admit patients, and provide overnight coverage. Requiring admission orders to be placed by physicians with admitting privileges would require a greater presence of staff physicians, which would increase costs.

Some of these concerns were voiced Aug. 15 on CMS' Special Open Door Forum on CMS Rule 1599-F. While clarification was not offered, it was indicated that CMS did not intend to place such limitations on residents, NPs, and PAs. On Sept. 5, CMS released clarifications to some of these provisions in the IPPS Final Rule, and noted that admission orders may come from a physician or other practitioner.

This clarification suggests that when a resident, NP, or PA writes admission orders, they are doing so at the direction of a physician with admitting privileges. This may occur in the form of a verbal order, which requires documentation of the name of the admitting physician, as well as the date and time of the verbal order. This verbal order must then be countersigned by a qualified physician prior to patient discharge.

Failures to obtain appropriate orders co-signed by an appropriate physician are likely at high risk for Medicare payment denial. This clarification appears to address previously held concerns about this new rule.

A federal rule that some hospitalists feared would bar nonstaff physicians from writing admission orders for hospital inpatients has been clarified to extend those privileges to resident physicians and advanced practitioners.

On Aug. 19, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its fiscal 2014 hospital Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Final Rule, which is effective Oct. 1. Although this document impacts a number of important areas for hospitals, including the use of inpatient admission and observation status, hospitalists also were left with the impression that resident physicians and advanced practitioners (NPs and PAs) were being barred from writing admission orders.

Medical residents, NPs, and PAs do not have admitting privileges in most hospitals, and their inability to write admission orders would pose significant logistical and financial hurdles for many hospitals and physician groups, including hospitalists.

In most academic centers, residents have the opportunity and responsibility to evaluate patients at the time of hospitalization, write initial hospitalization orders, and then discuss patients with the attending physician. The "staffing" of patients typically occurs either later the same day or the following morning. The provision requiring an attending physician knowledgeable of the case to furnish the admission order, and not allowing delegation of this order to their residents, could fundamentally change the way our physicians are trained.

Many hospitals rely on NPs and PAs for the care of hospitalized patients under the supervision of a staff physician. These nonphysician providers often care for hospitalized patients, admit patients, and provide overnight coverage. Requiring admission orders to be placed by physicians with admitting privileges would require a greater presence of staff physicians, which would increase costs.

Some of these concerns were voiced Aug. 15 on CMS' Special Open Door Forum on CMS Rule 1599-F. While clarification was not offered, it was indicated that CMS did not intend to place such limitations on residents, NPs, and PAs. On Sept. 5, CMS released clarifications to some of these provisions in the IPPS Final Rule, and noted that admission orders may come from a physician or other practitioner.

This clarification suggests that when a resident, NP, or PA writes admission orders, they are doing so at the direction of a physician with admitting privileges. This may occur in the form of a verbal order, which requires documentation of the name of the admitting physician, as well as the date and time of the verbal order. This verbal order must then be countersigned by a qualified physician prior to patient discharge.

Failures to obtain appropriate orders co-signed by an appropriate physician are likely at high risk for Medicare payment denial. This clarification appears to address previously held concerns about this new rule.