User login

Association Between Psoriasis and Obesity Among US Adults in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

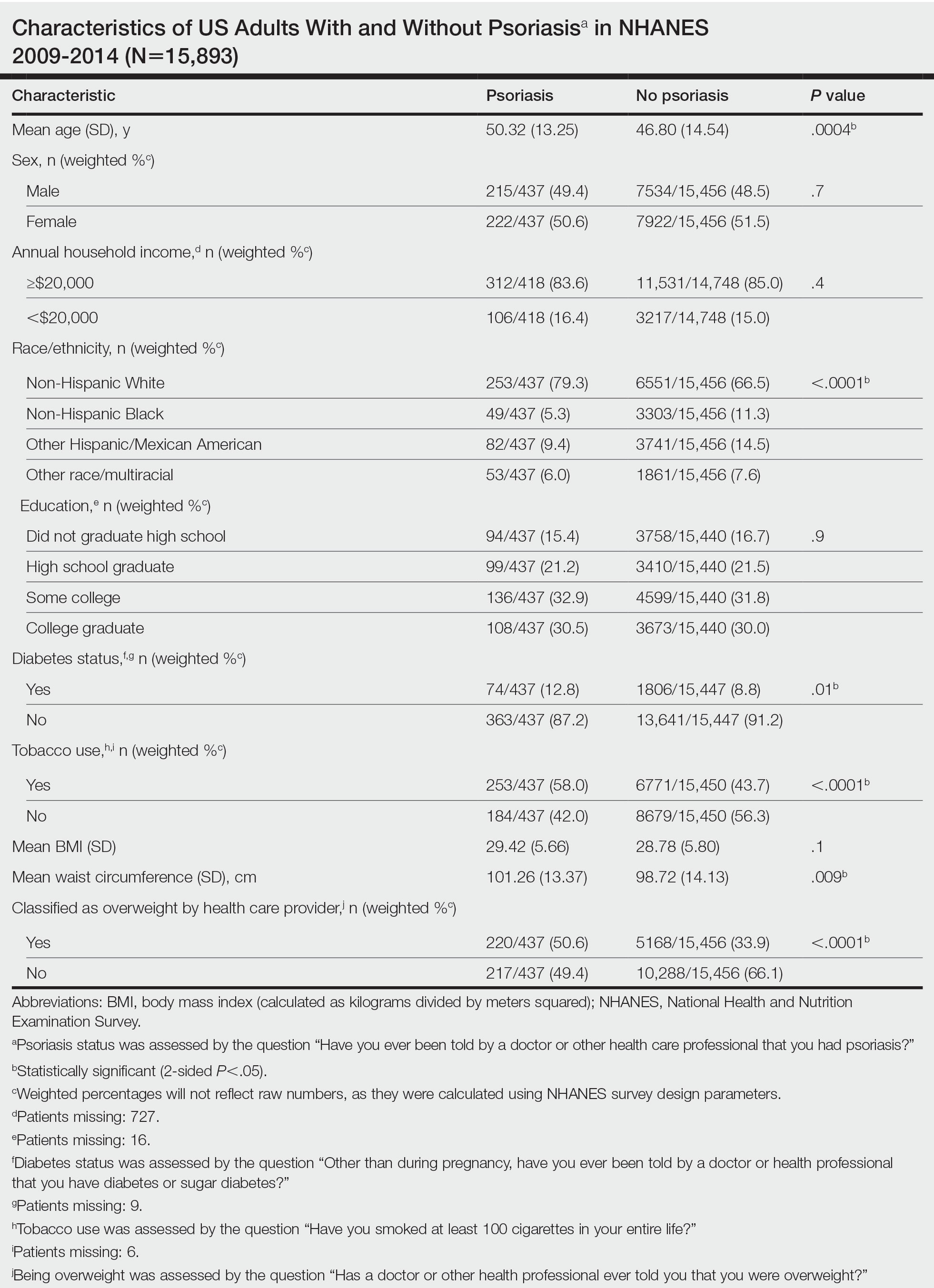

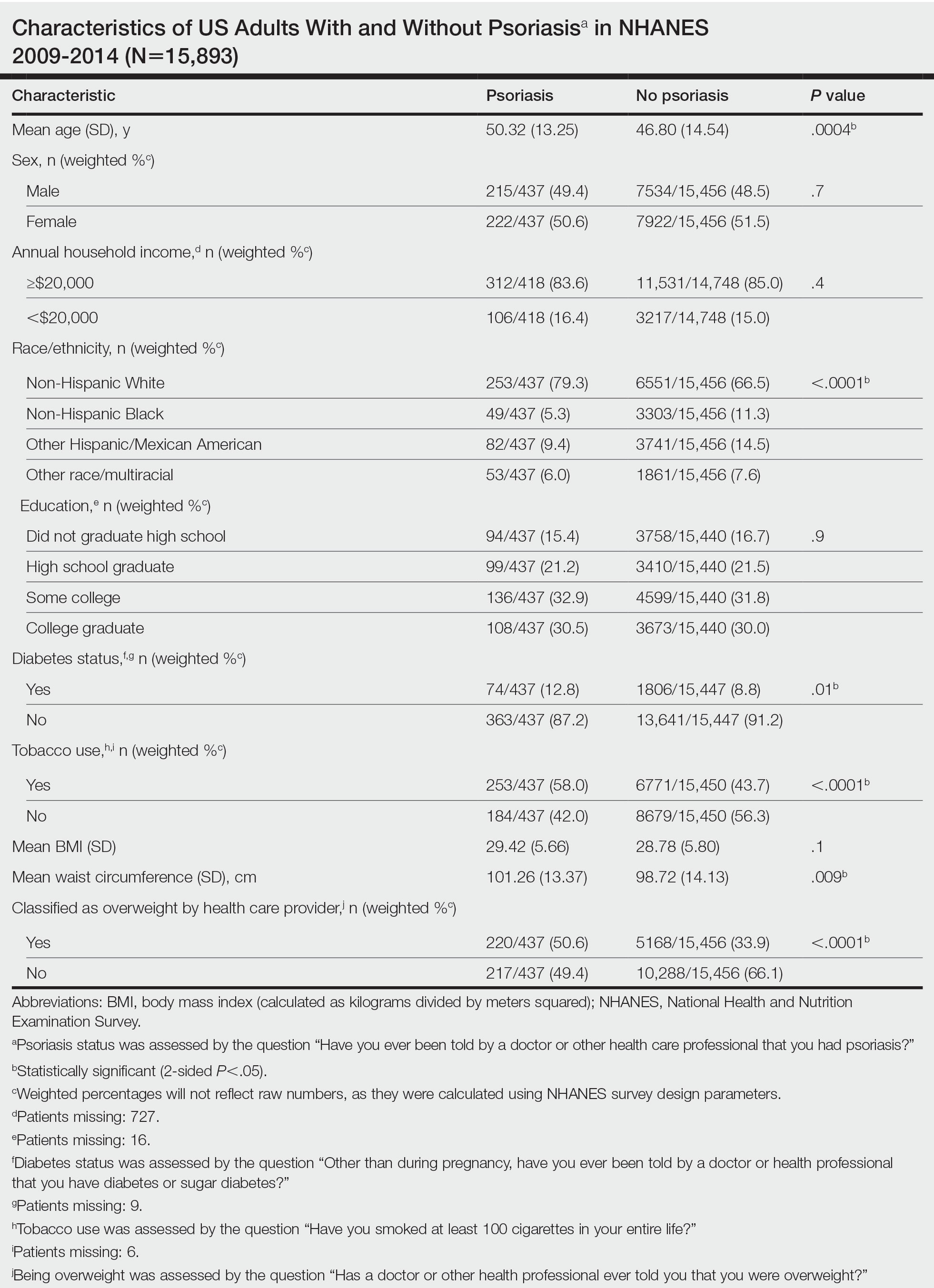

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

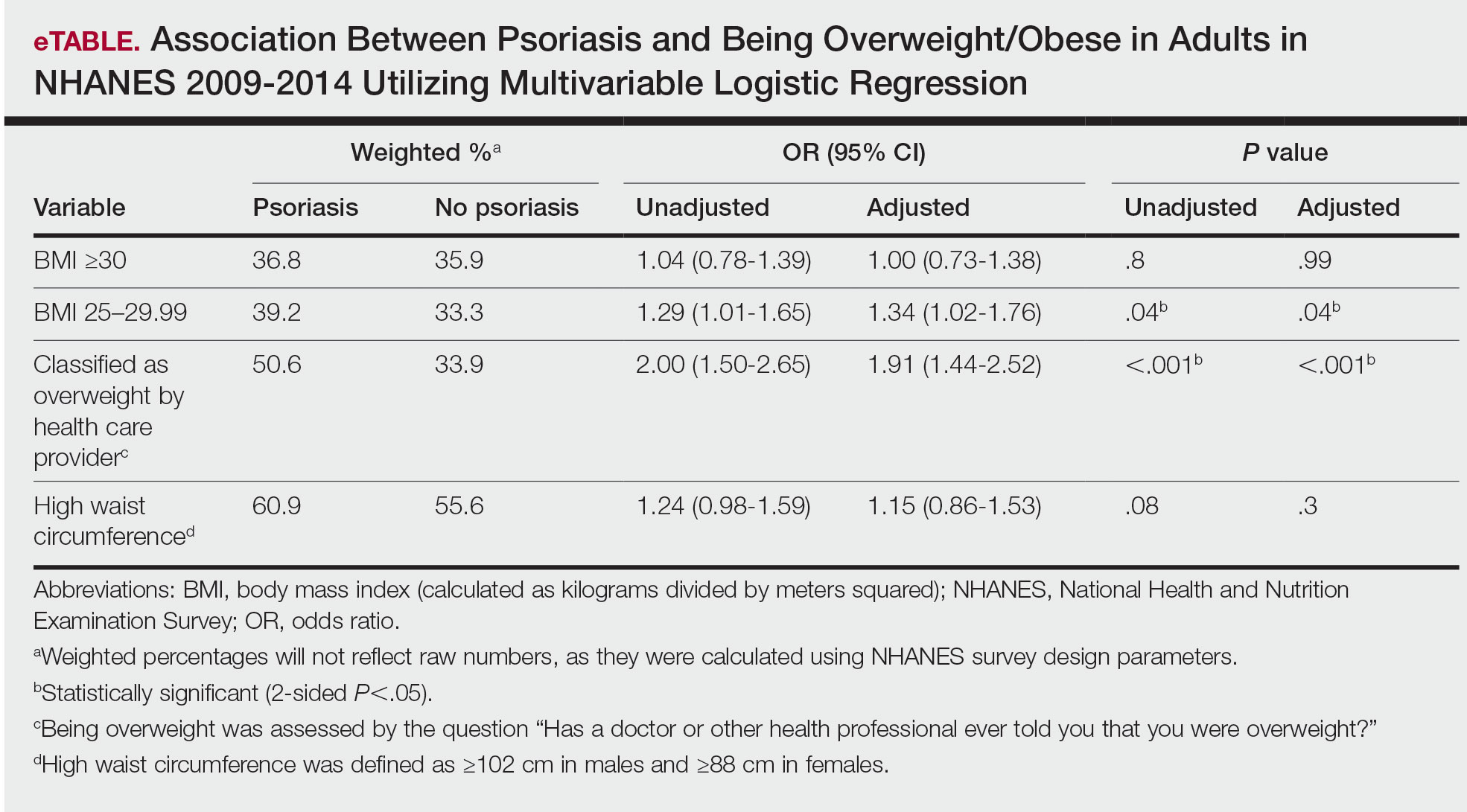

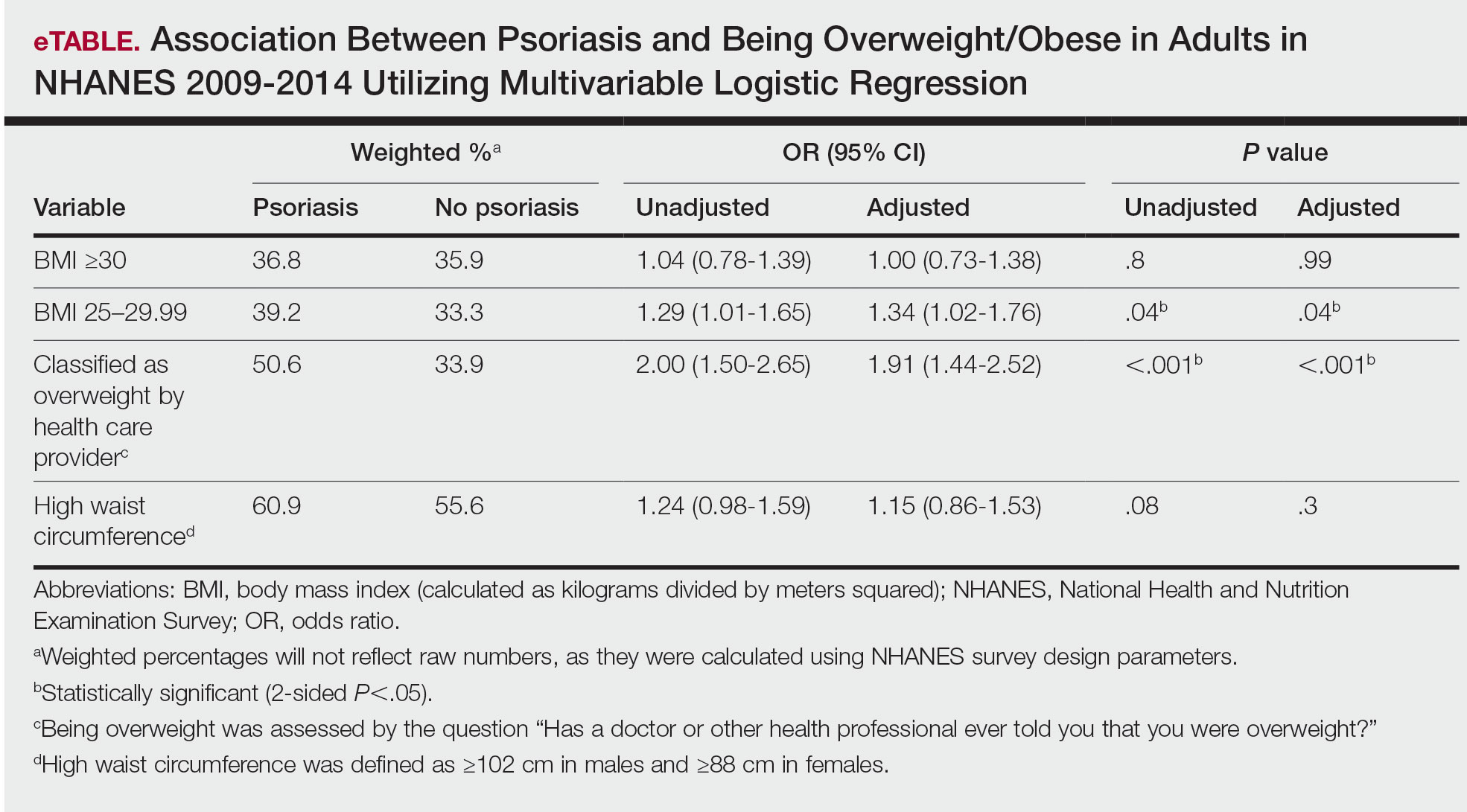

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

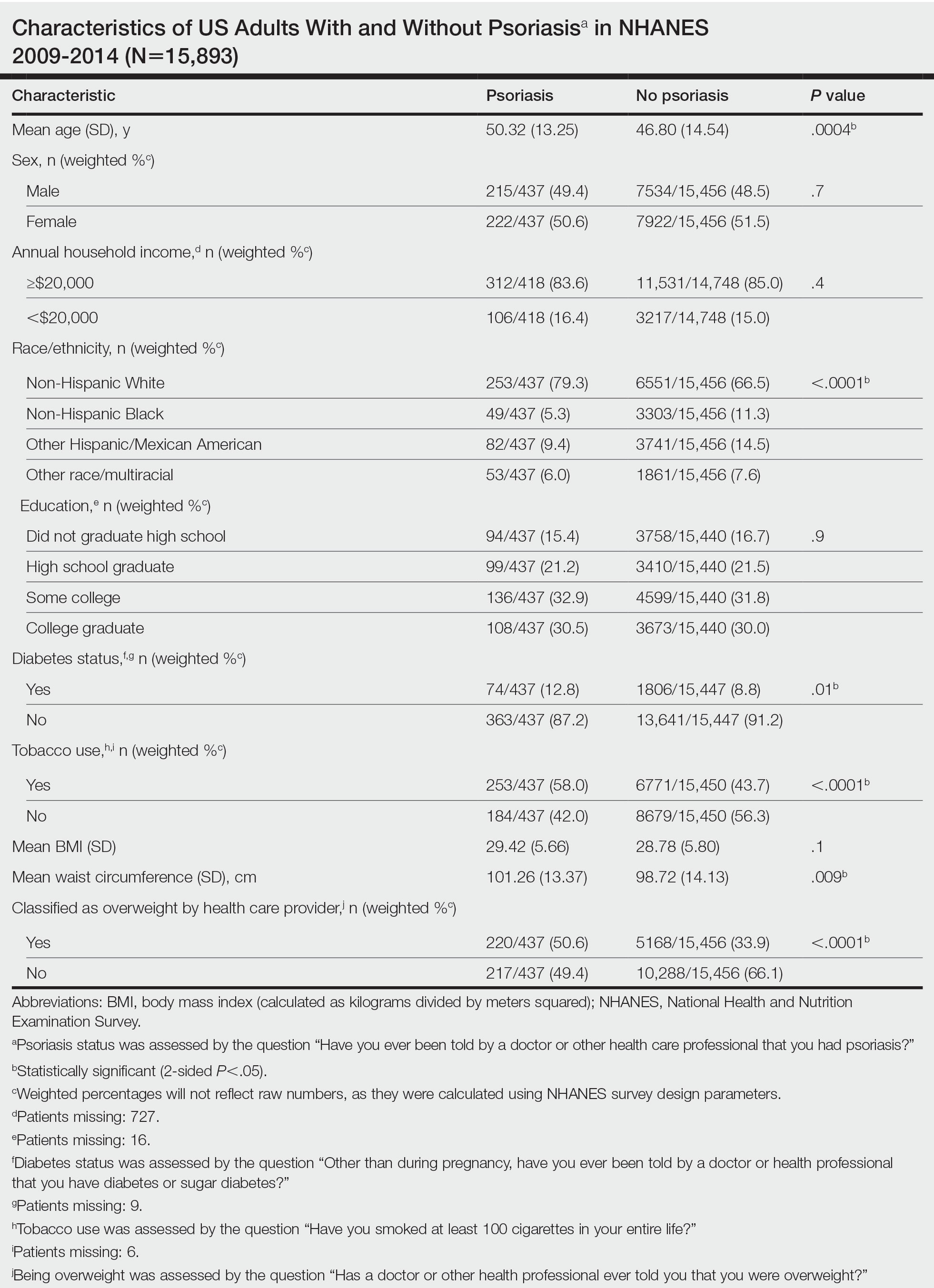

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

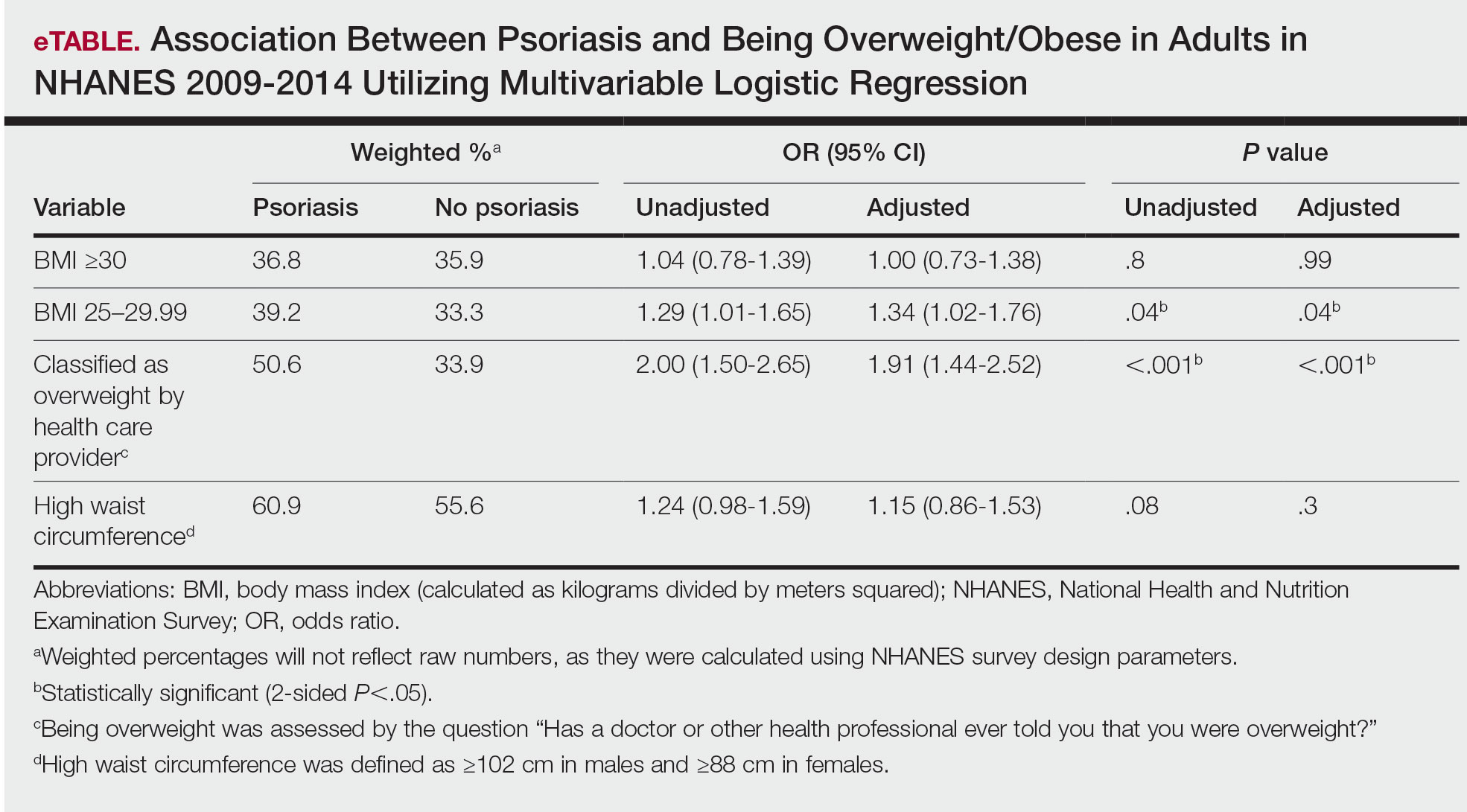

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

Practice Points

- There are many comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis, making it crucial to evaluate for these diseases in patients with psoriasis.

- Obesity may be a contributing factor to psoriasis development due to the role of IL-17 secretion.

Medicare Part D Prescription Claims for Brodalumab: Analysis of Annual Trends for 2017-2019

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

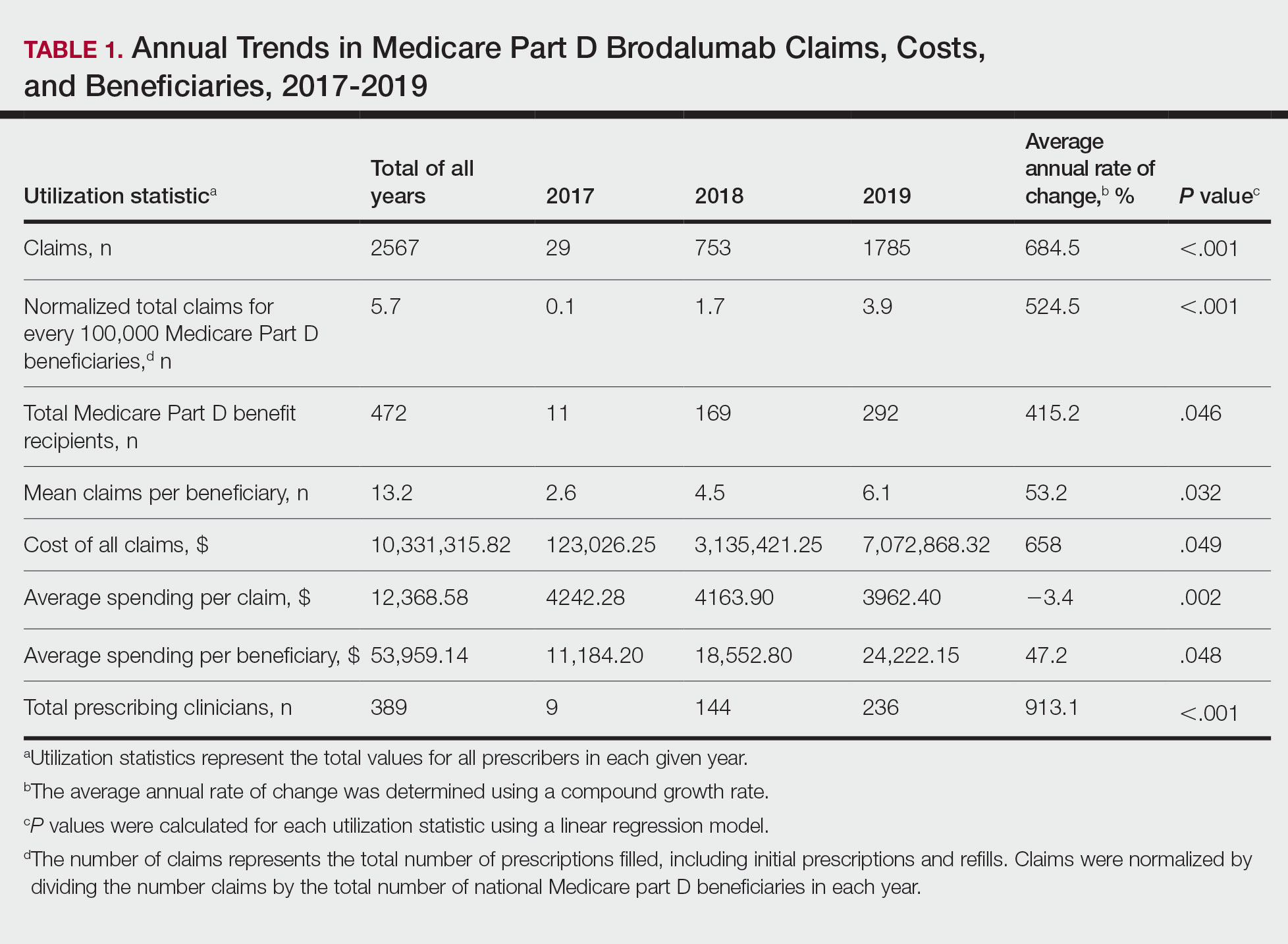

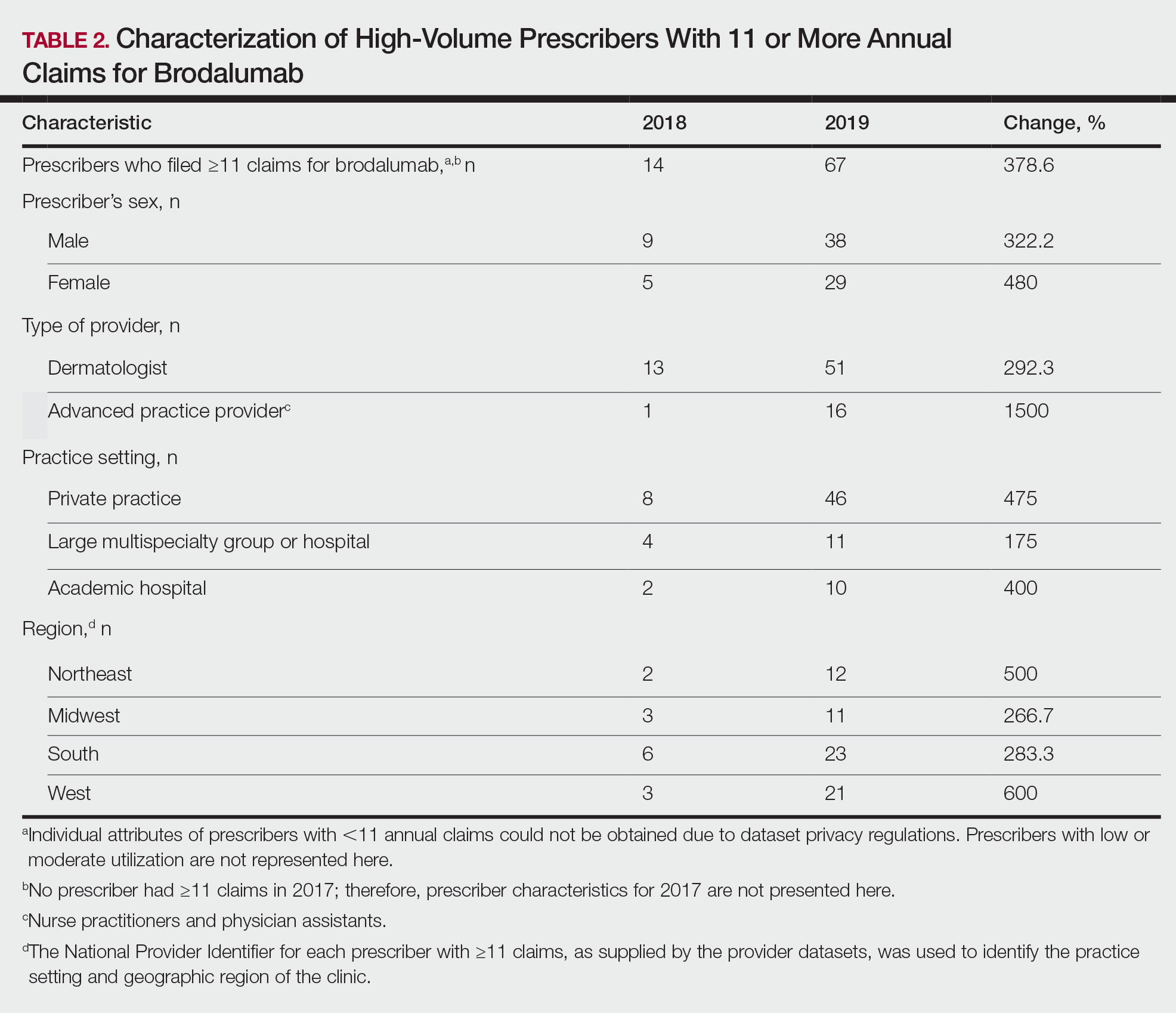

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

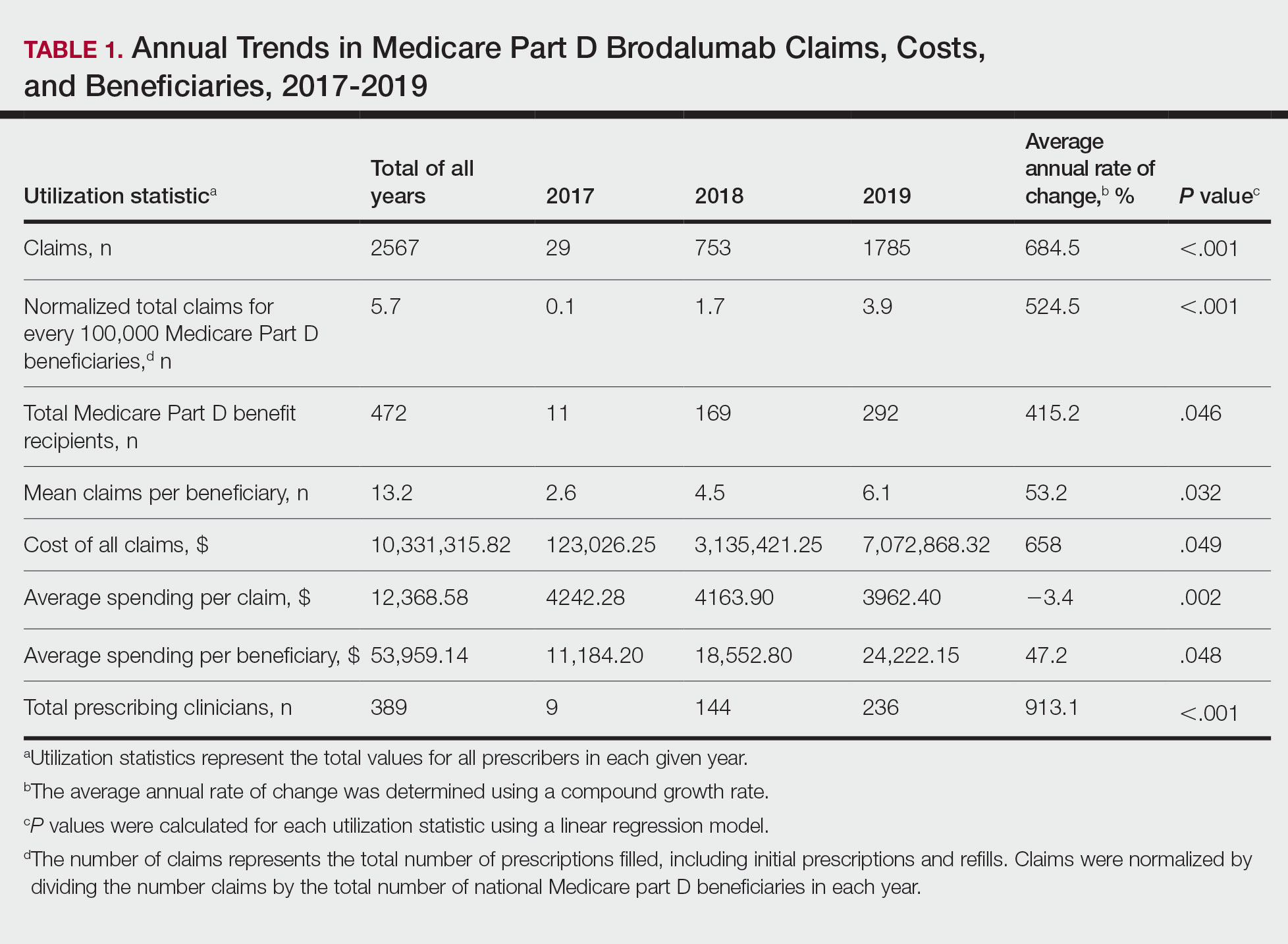

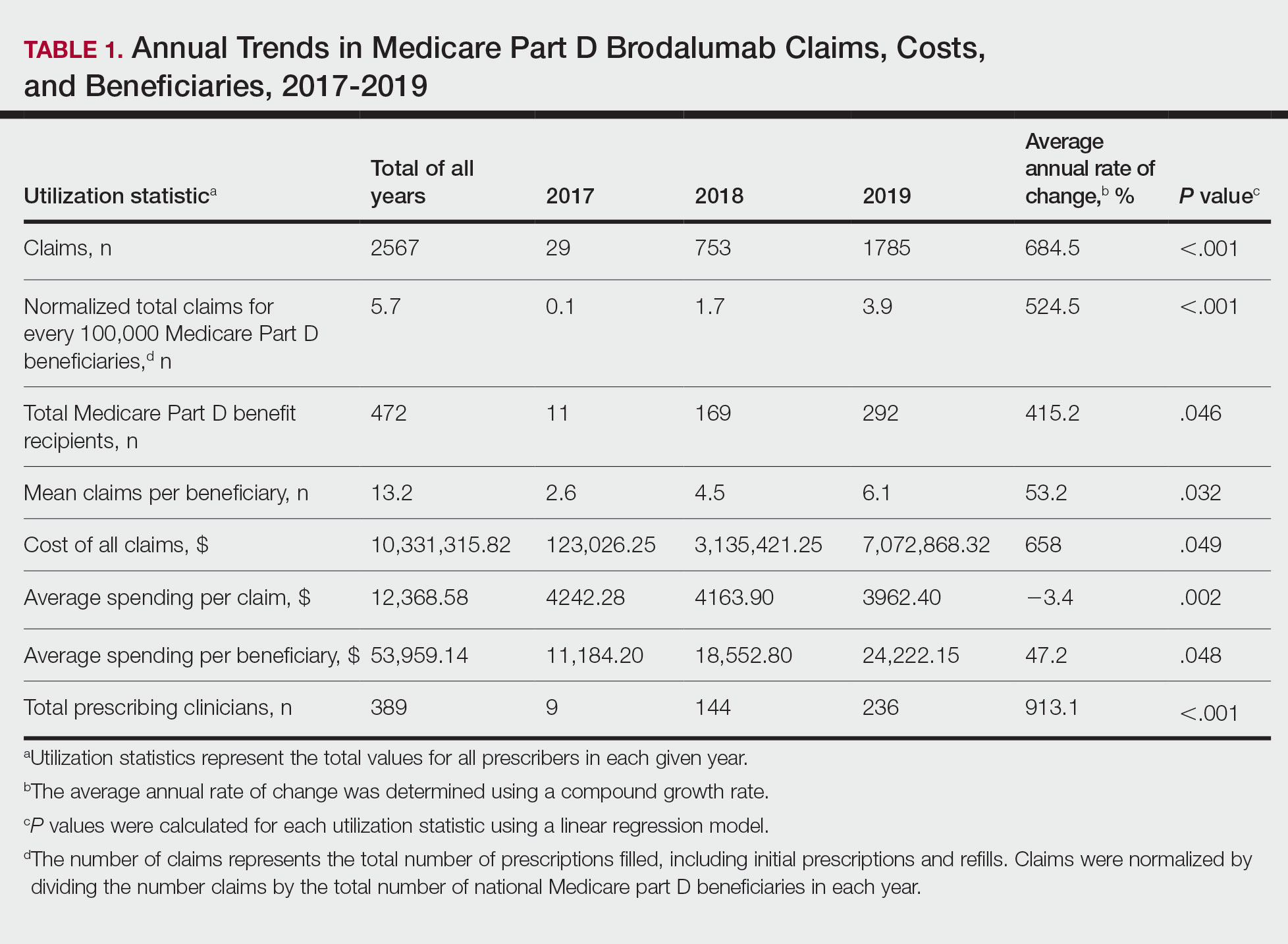

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

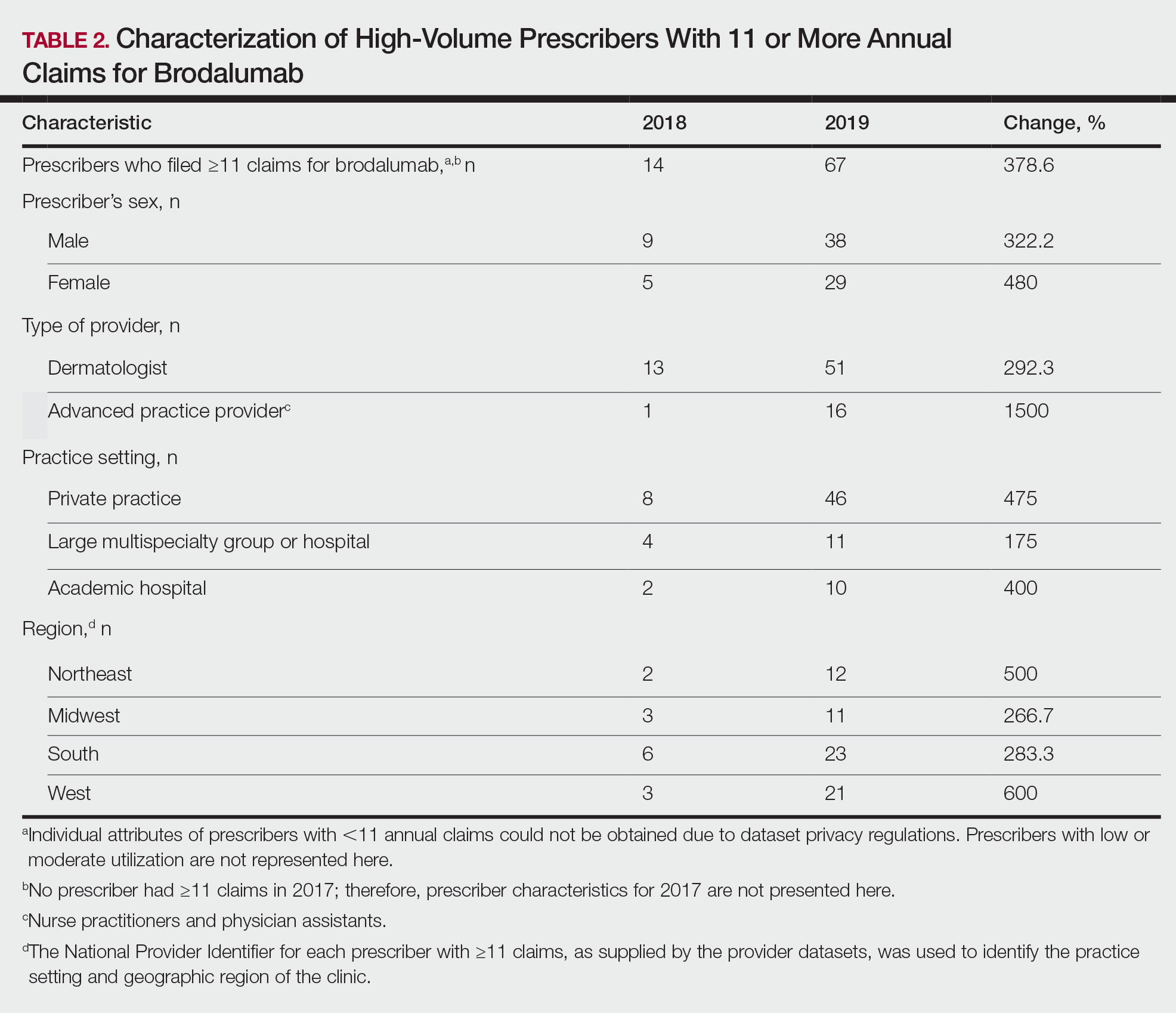

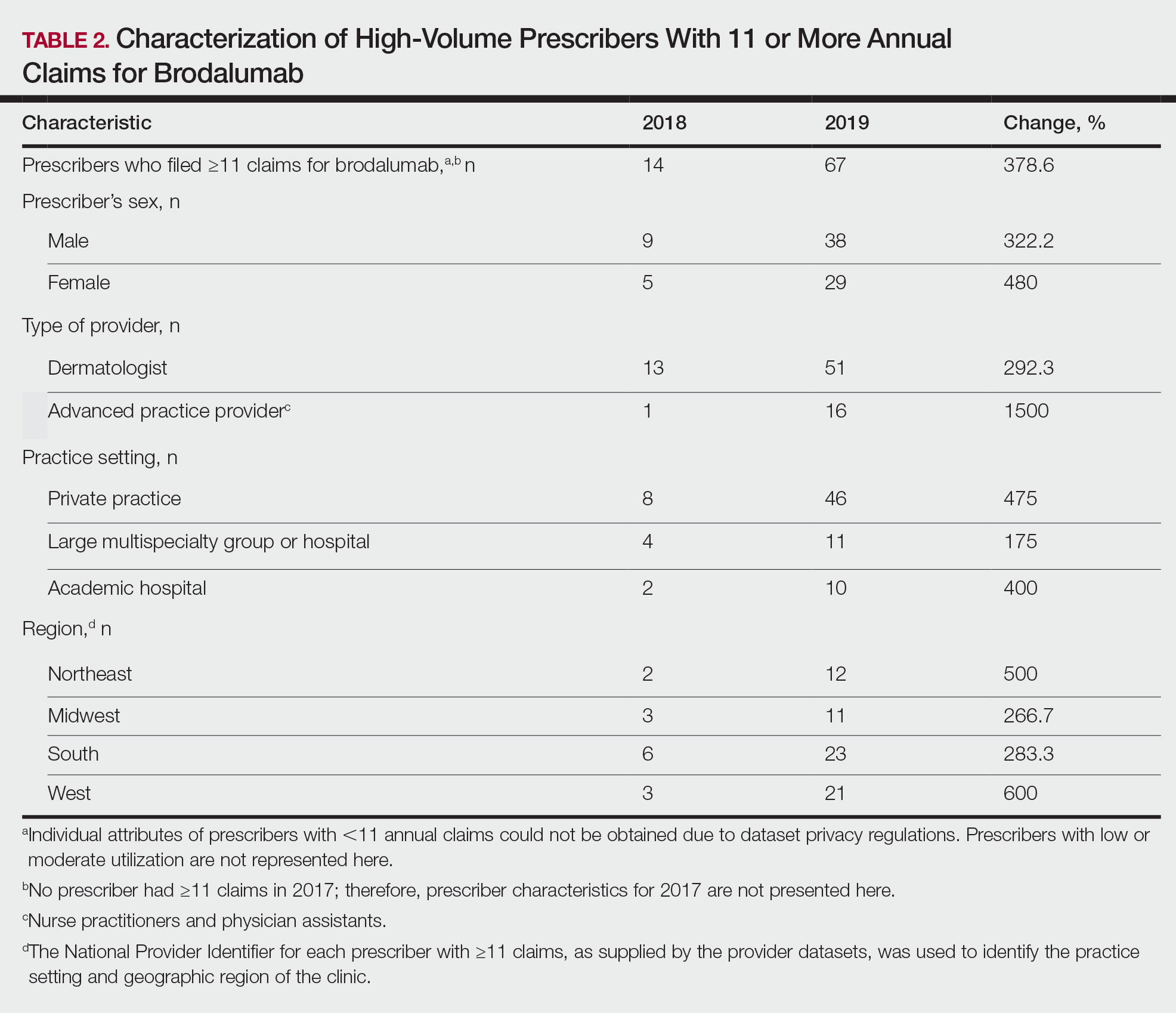

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

Practice Points

- Brodalumab is associated with a boxed warning due to increased suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

- Brodalumab is underutilized compared to the other US Food and Drug Administration–approved IL-17 inhibitors used to treat psoriasis.

- Most experts agree that there is no increased risk for suicide associated with brodalumab. However, it remains imperative that prescribers assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services prior to initiating and during treatment with brodalumab.