User login

Association Between LDL-C and Androgenetic Alopecia Among Female Patients in a Specialty Alopecia Clinic

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

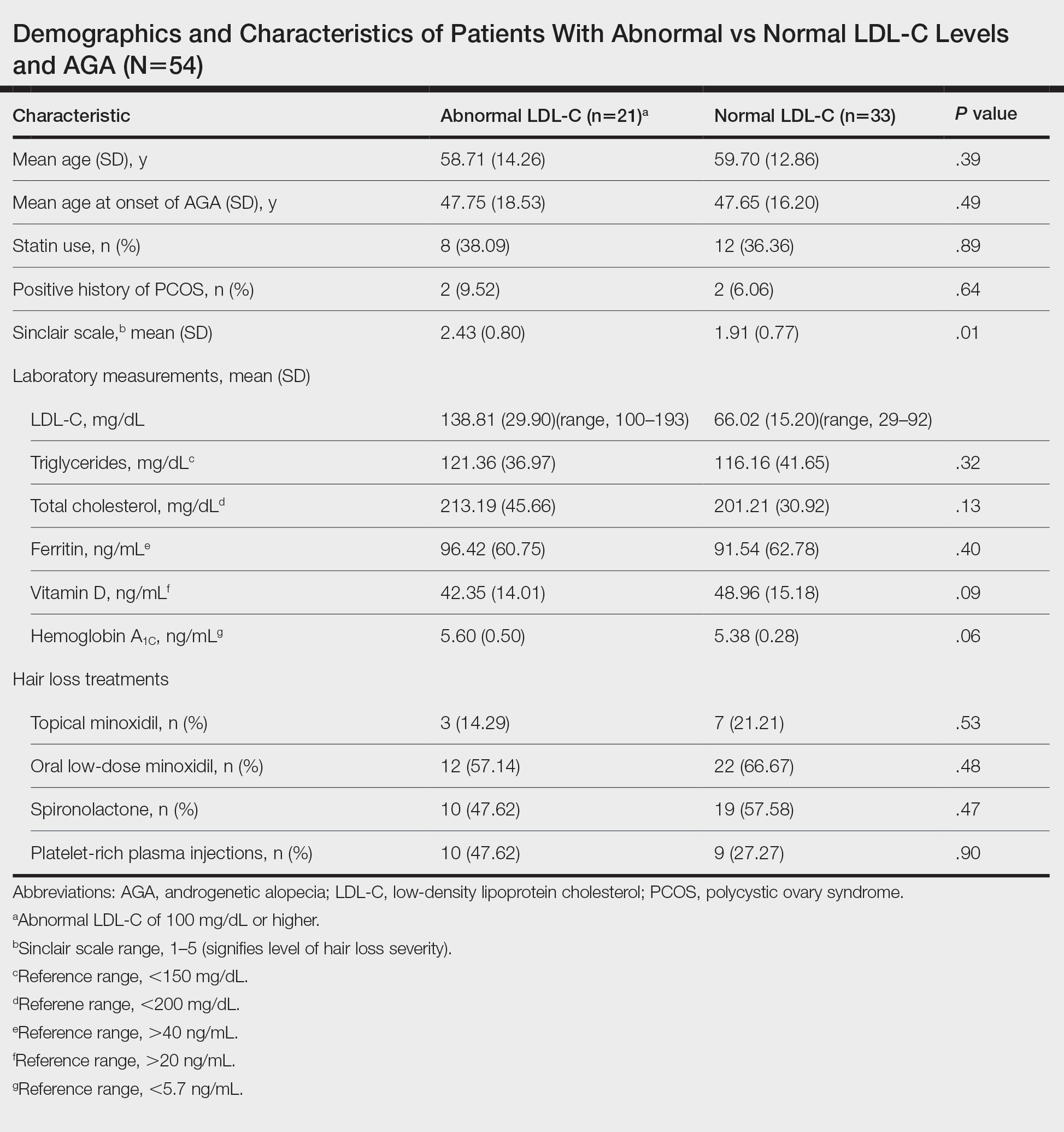

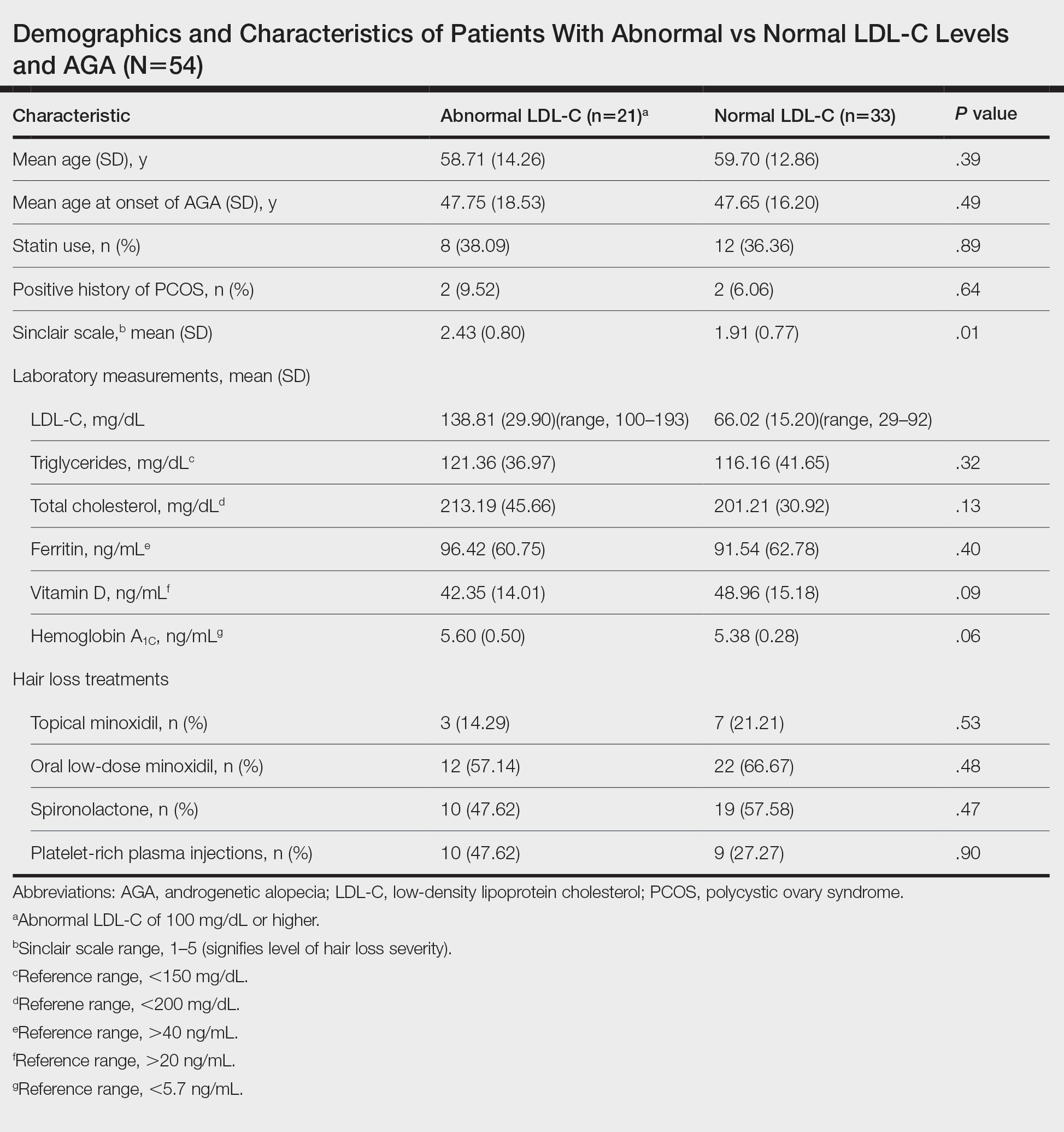

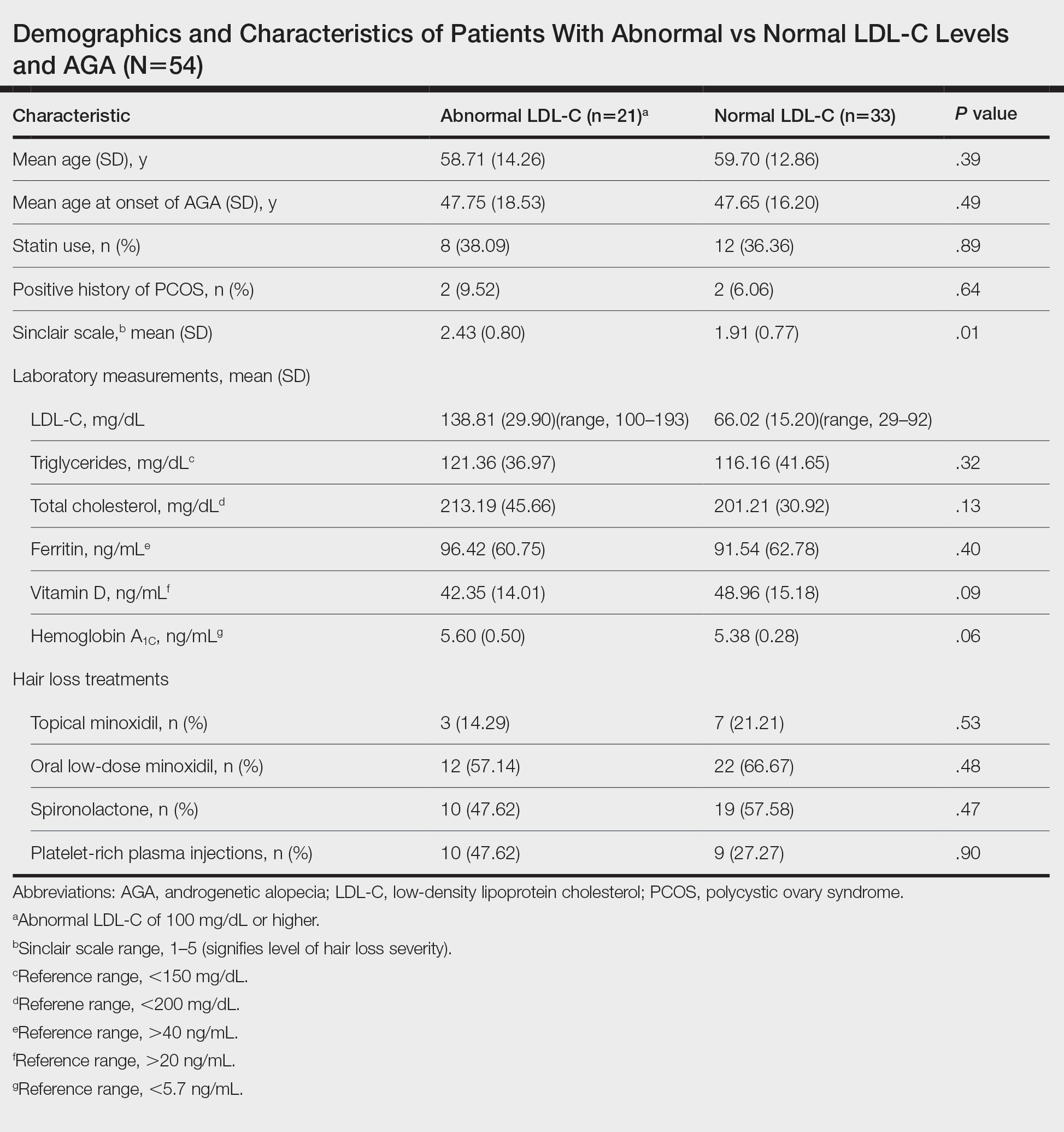

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss (FPHL), or androgenetic alopecia (AGA), is the most common form of alopecia worldwide and is characterized by a reduction of hair follicles spent in the anagen phase of growth as well as progressive terminal hair loss.1 It is caused by an excessive response to androgens and leads to the characteristic distribution of hair loss in both sexes. Studies have shown a notable association between AGA and markers of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and obesity in age- and sex-matched controls.2,3 However, research describing the relationship between AGA severity and these markers is scarce.

To understand the relationship between FPHL severity and abnormal cholesterol levels, we performed a retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with FPHL at a specialty alopecia clinic from June 2022 to December 2022. Patient age and age at onset of FPHL were collected. The severity of FPHL was measured using the Sinclair scale (score range, 1–5) and unidentifiable patient photographs. Laboratory values were collected; abnormal cholesterol was defined by the American Heart Association as having a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level of 100 mg/dL or higher.4 Finally, data on medication use were noted to understand patient treatment status (Table).

We identified 54 female patients with FPHL with an average age of 59 years (range, 34–80 years). Thirty-three females (61.11%) had a normal LDL-C level and 21 (38.89%) had an abnormal level. The mean (SD) LDL-C level was 66.02 (15.20) mg/dL (range, 29–92 mg/dL) in the group with normal levels and 138.81 (29.90) mg/dL (range, 100–193 mg/dL) in the group with abnormal levels. Patients with abnormal LDL-C had significantly higher Sinclair scale scores compared to those with normal levels (2.43 vs 1.91; P=.01). There were no significant differences in patient age (58.71 vs 59.70 years; P=.39), age at onset of AGA (47.75 vs 47.65 years; P=.49), history of polycystic ovary syndrome (9.52% vs 6.06%; P=.64), or statin use (38.09% vs 36.36%; P=.89) between patients with abnormal and normal LDL-C levels, respectively. There also were no significant differences in ferritin (96.42 vs 91.54 ng/mL; P=.40), vitamin D (42.35 vs 48.96 ng/mL; P=.09), or hemoglobin A1c levels (5.60 ng/mL vs 5.38 ng/mL; P=.06)—variables that could have confounded this relationship. Triglycerides were within reference range in both groups (121.36 vs 116.16 mg/dL; P=.32), while total cholesterol was mildly elevated in both groups but not significantly different (213.19 vs 201.21 mg/dL; P=.13). Use of hair loss treatments such as topical minoxidil (14.29% vs 21.21%; P=.53), oral low-dose minoxidil (57.14% vs 66.67%; P=.48), oral spironolactone (47.62% vs 57.58%; P=.47), and platelet-rich plasma injections (47.62% vs 27.27%; P=.90) were not significantly different across both groups.

The data suggest a significant (P<.05) association between abnormal LDL-C and hair loss severity in FPHL patients. Our study was limited by its small sample size and lack of causality; however, it coincides with and reiterates the findings established in the literature. The mechanism of the association between hyperlipidemia and AGA is not well understood but is thought to stem from the homology between cholesterol and androgens. Increased cholesterol release from dermal adipocytes and subsequent absorption into hair follicle cell populations may increase hair follicle steroidogenesis, thereby accelerating the anagen-catagen transition and inducing AGA. Alternatively, impaired cholesterol homeostasis may disrupt normal hair follicle cycling by interrupting signaling pathways in follicle proliferation and differentiation.5 Adequate control and monitoring of LDL-C levels may be important, particularly in patients with more severe FPHL.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:E9860. doi:10.5812/ijem.9860

- El Sayed MH, Abdallah MA, Aly DG, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with female pattern hair loss in women: a case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:1131-1137. doi:10.1111/ijd.13303

- Kim MW, Shin IS, Yoon HS, et al. Lipid profile in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:942-951. doi:10.1111/jdv.14000

- Birtcher KK, Ballantyne CM. Cardiology patient page. measurement of cholesterol: a patient perspective. Circulation. 2004;110:E296-E297. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000141564.89465.4E

- Palmer MA, Blakeborough L, Harries M, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: links to hair follicle biology and hair disorders. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:299-311. doi:10.1111/exd.13993

Practice Points

- Associations have been shown between hair loss and markers of bad health such as insulin resistance and high cholesterol. Research has not yet shown the relationship between hair loss severity and these markers, particularly cholesterol.

Financial Insecurity Among US Adults With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

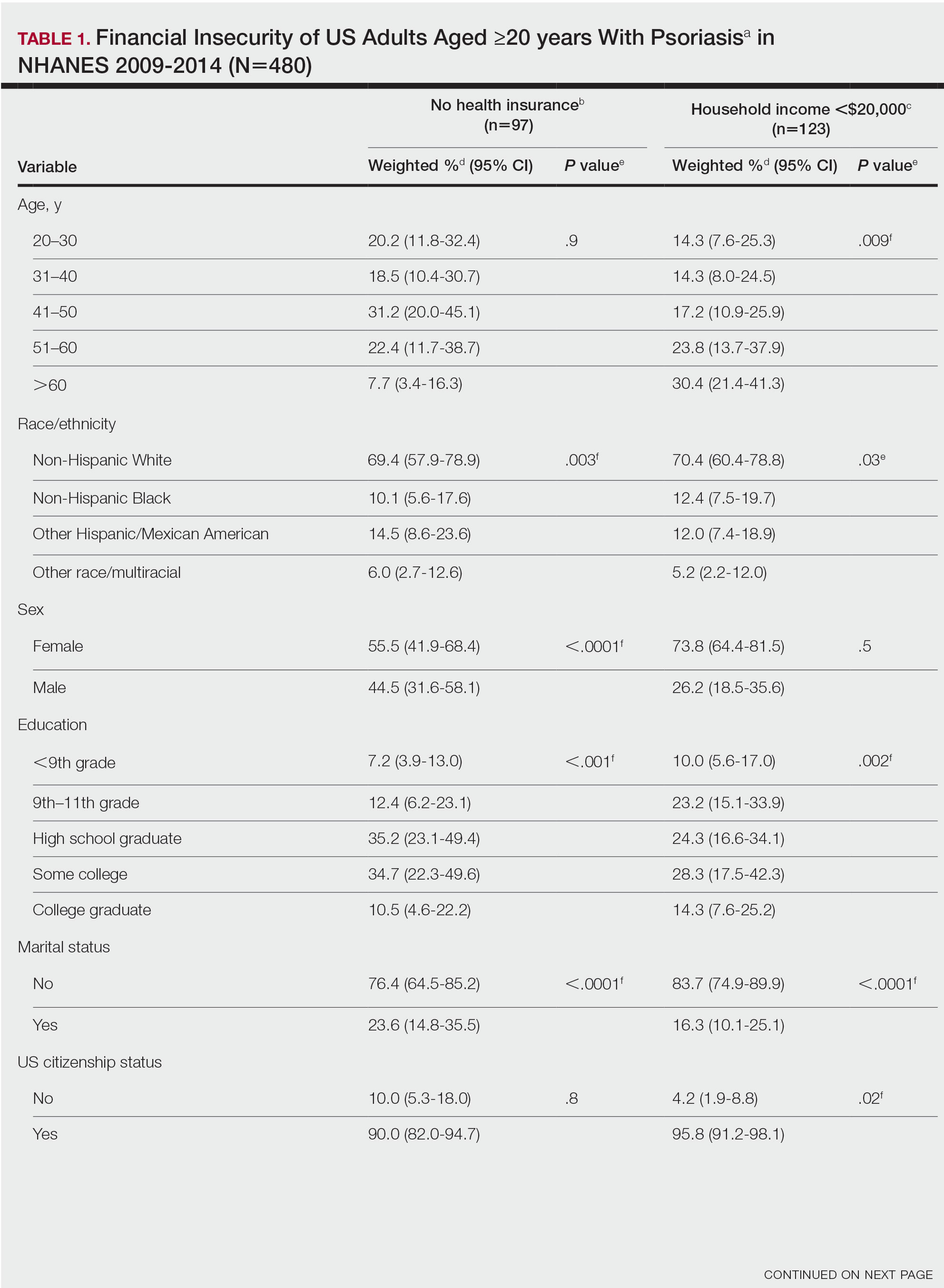

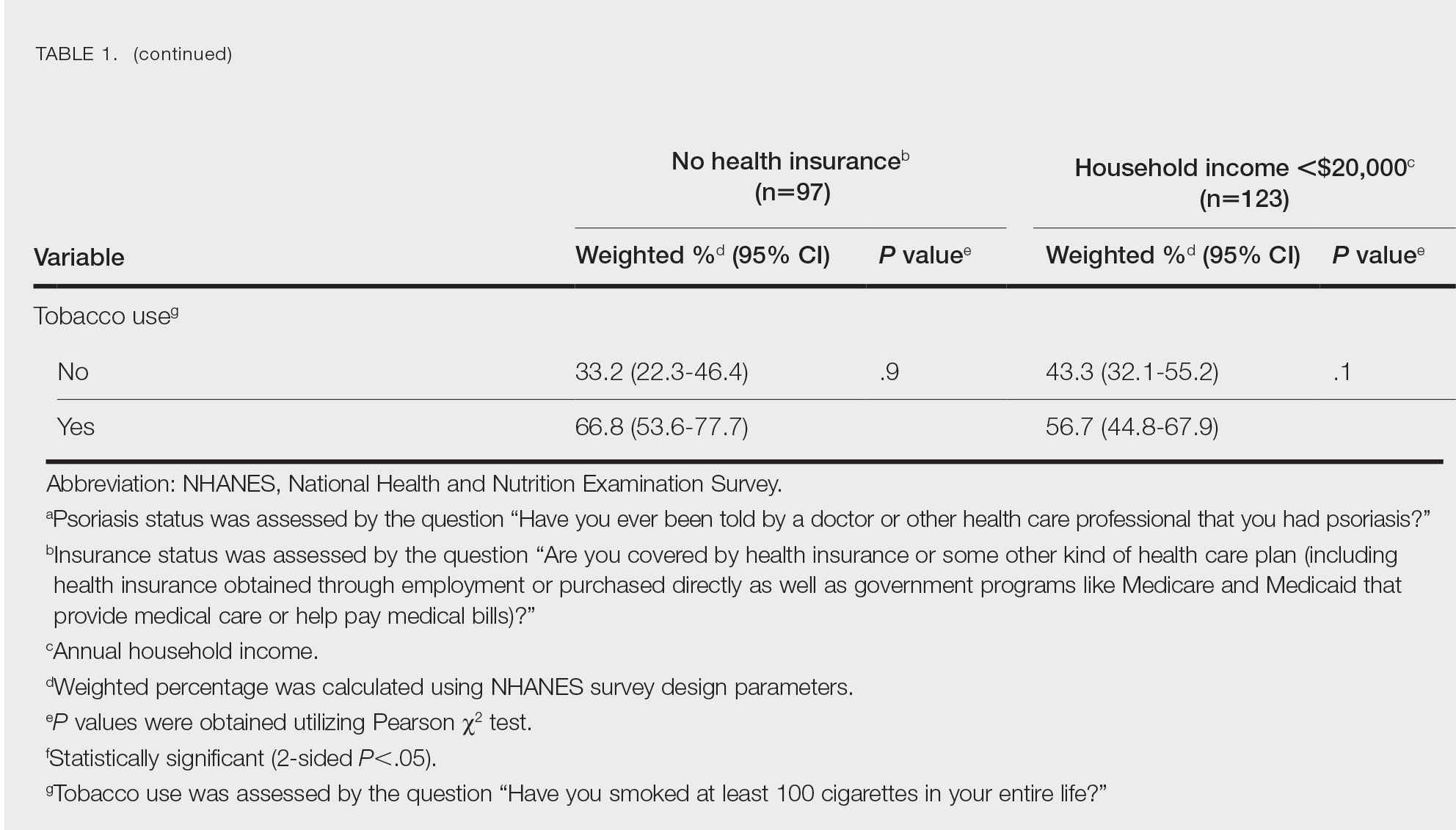

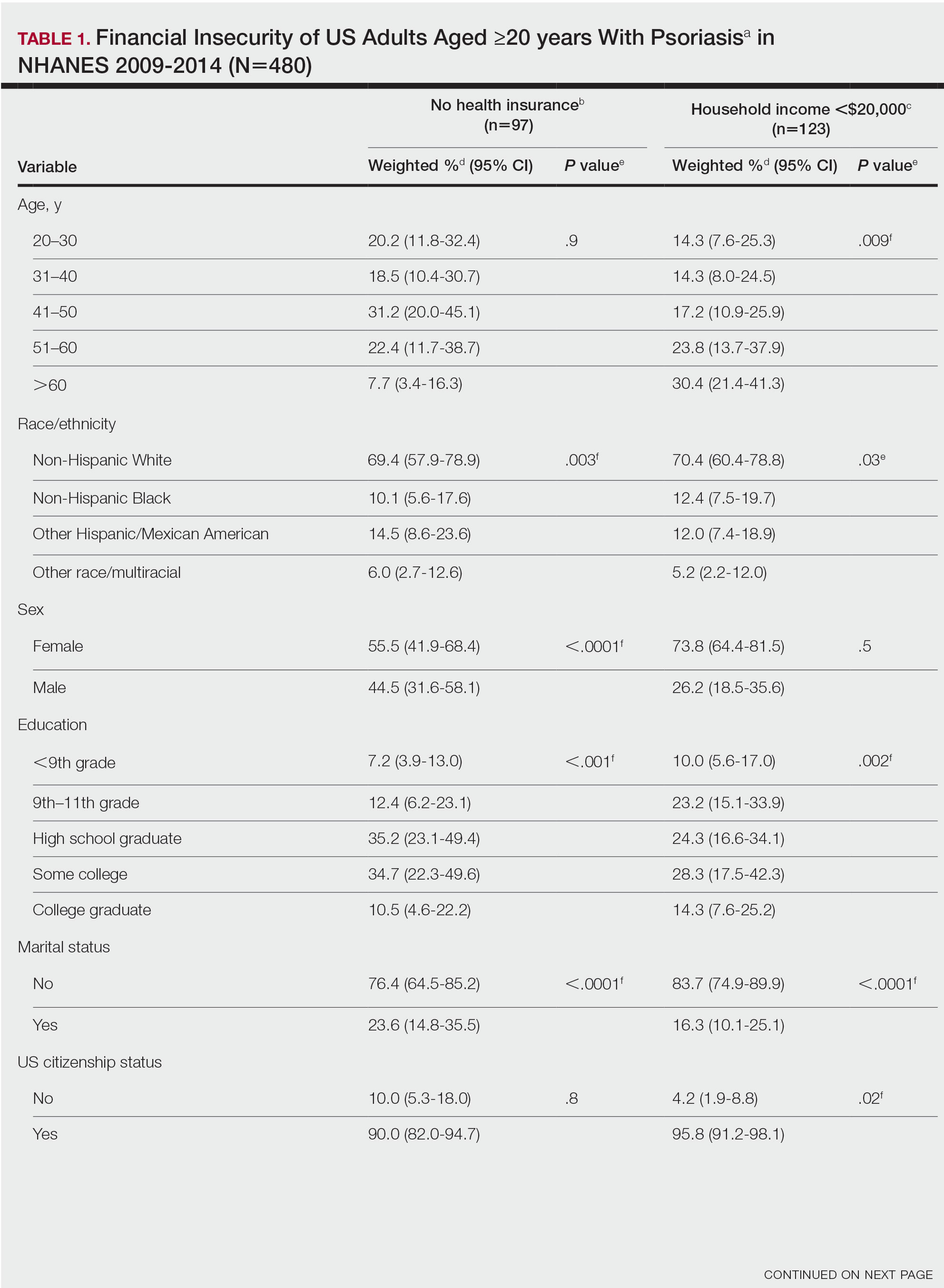

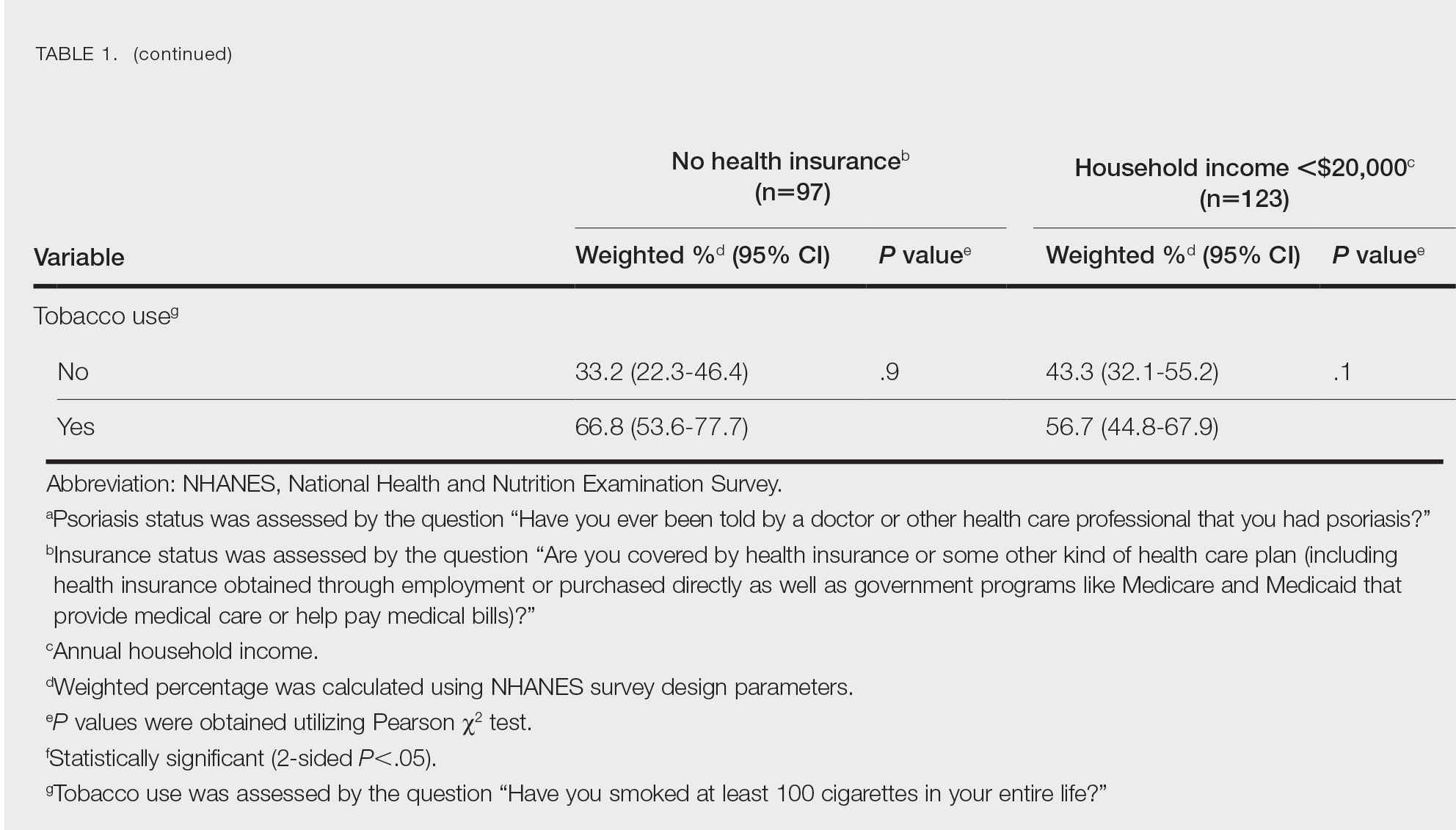

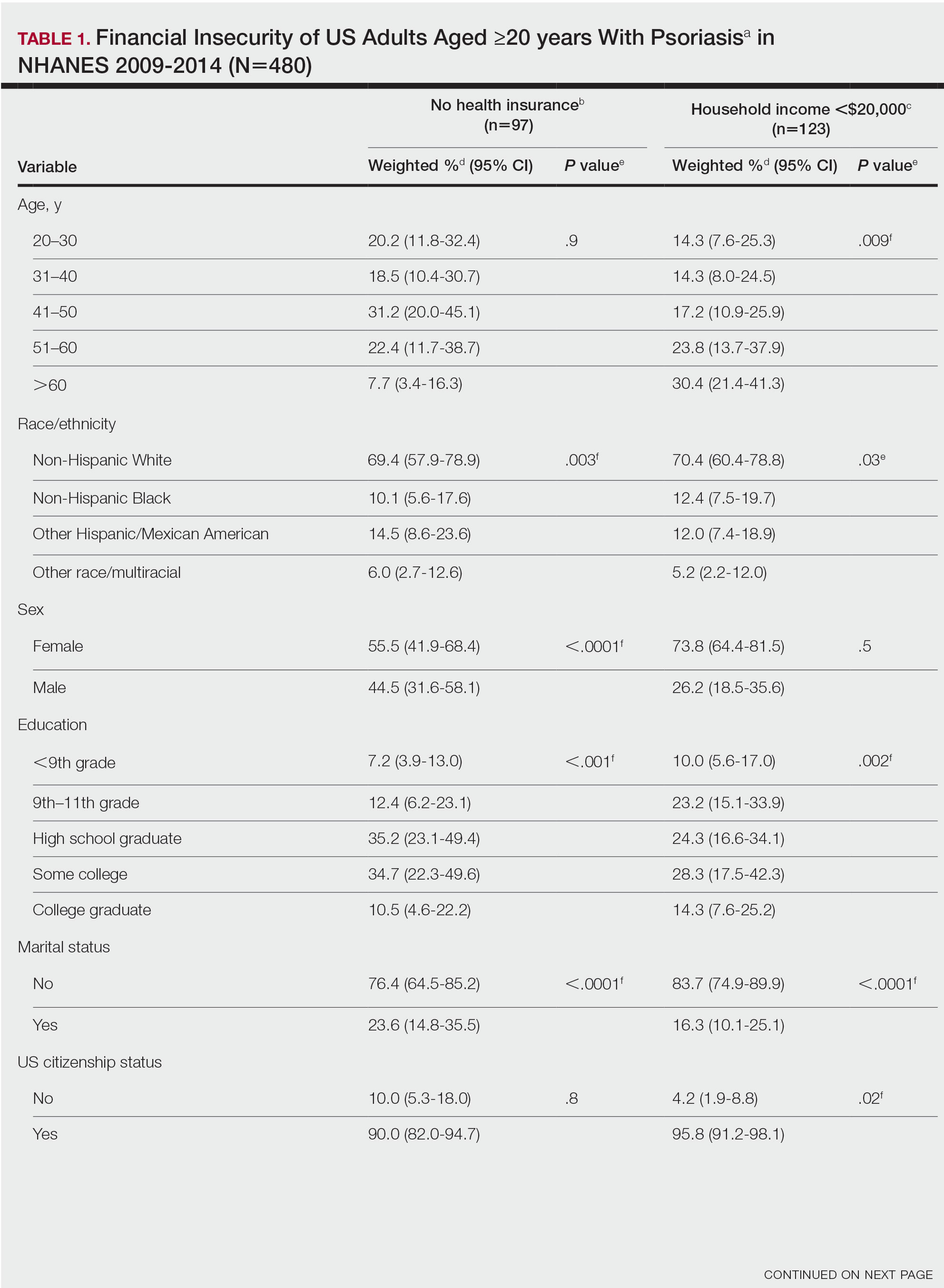

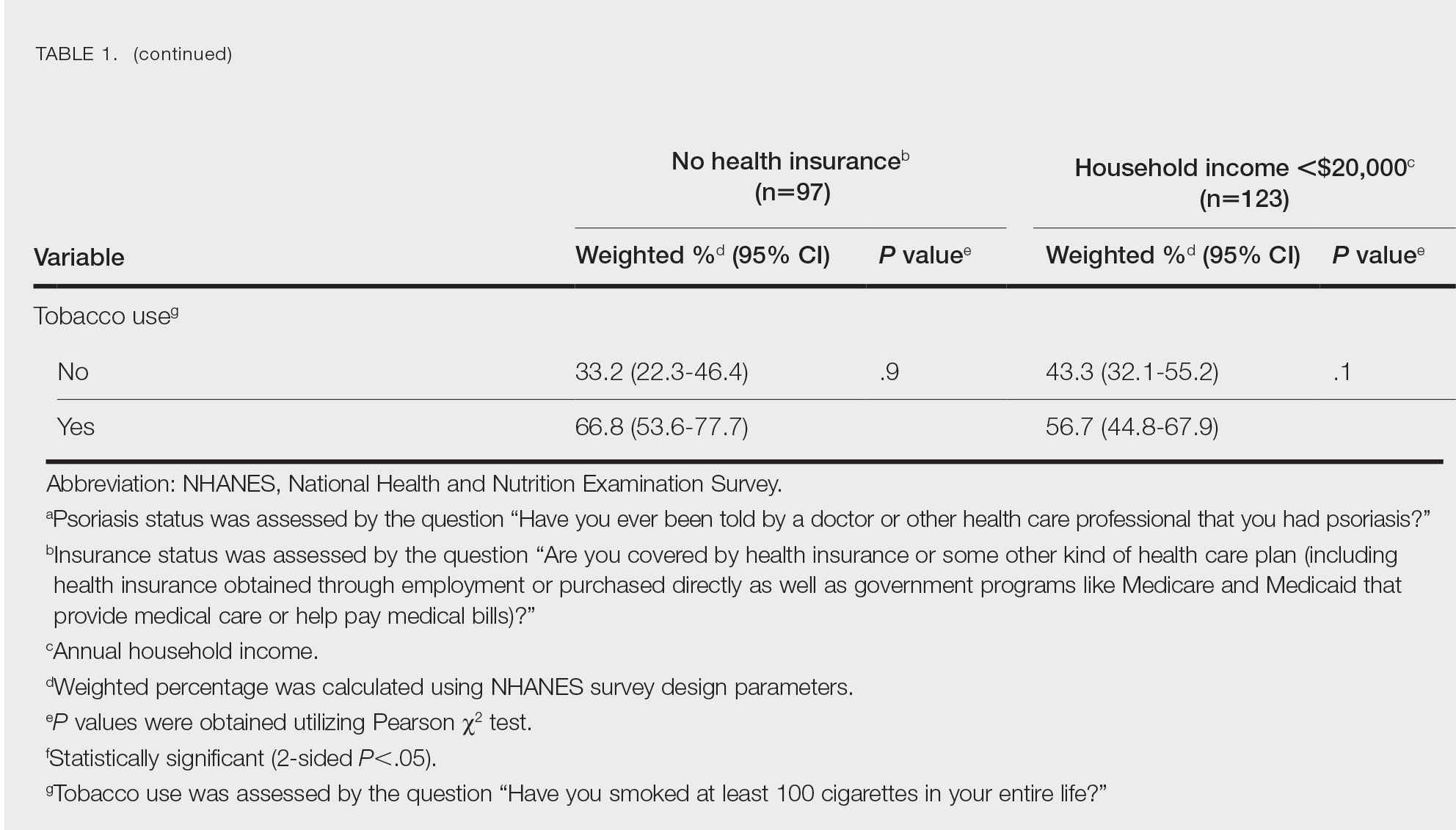

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

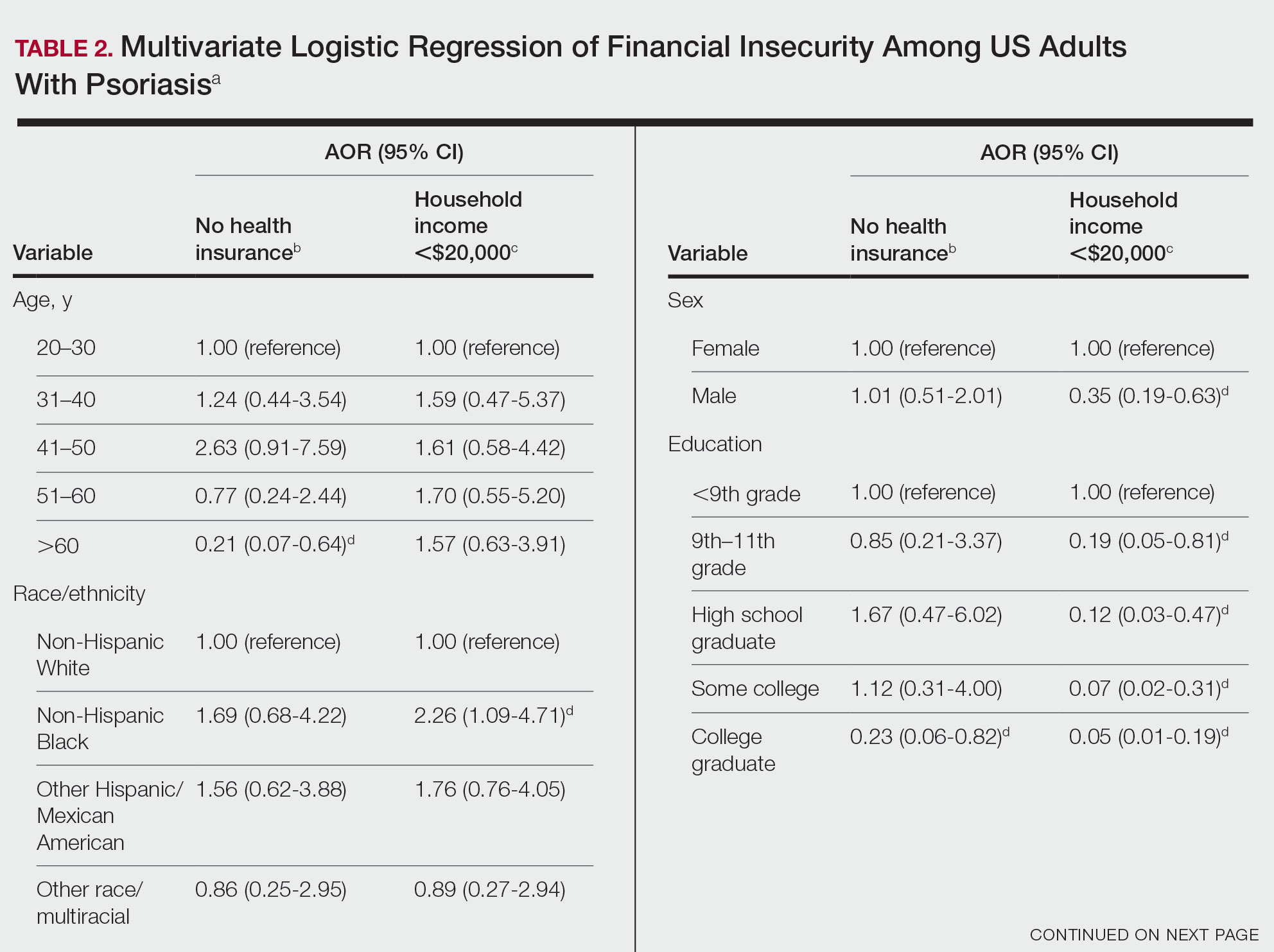

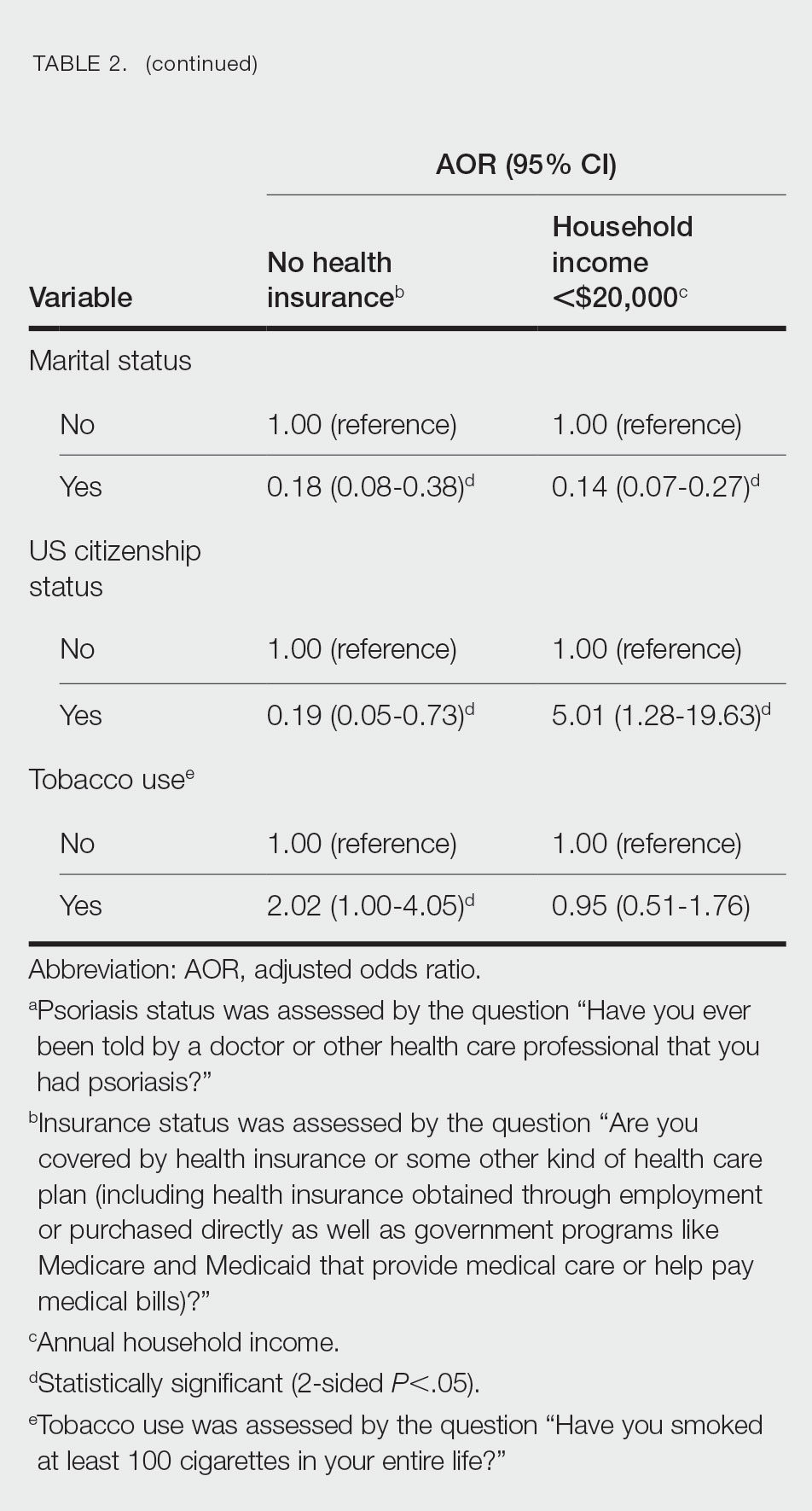

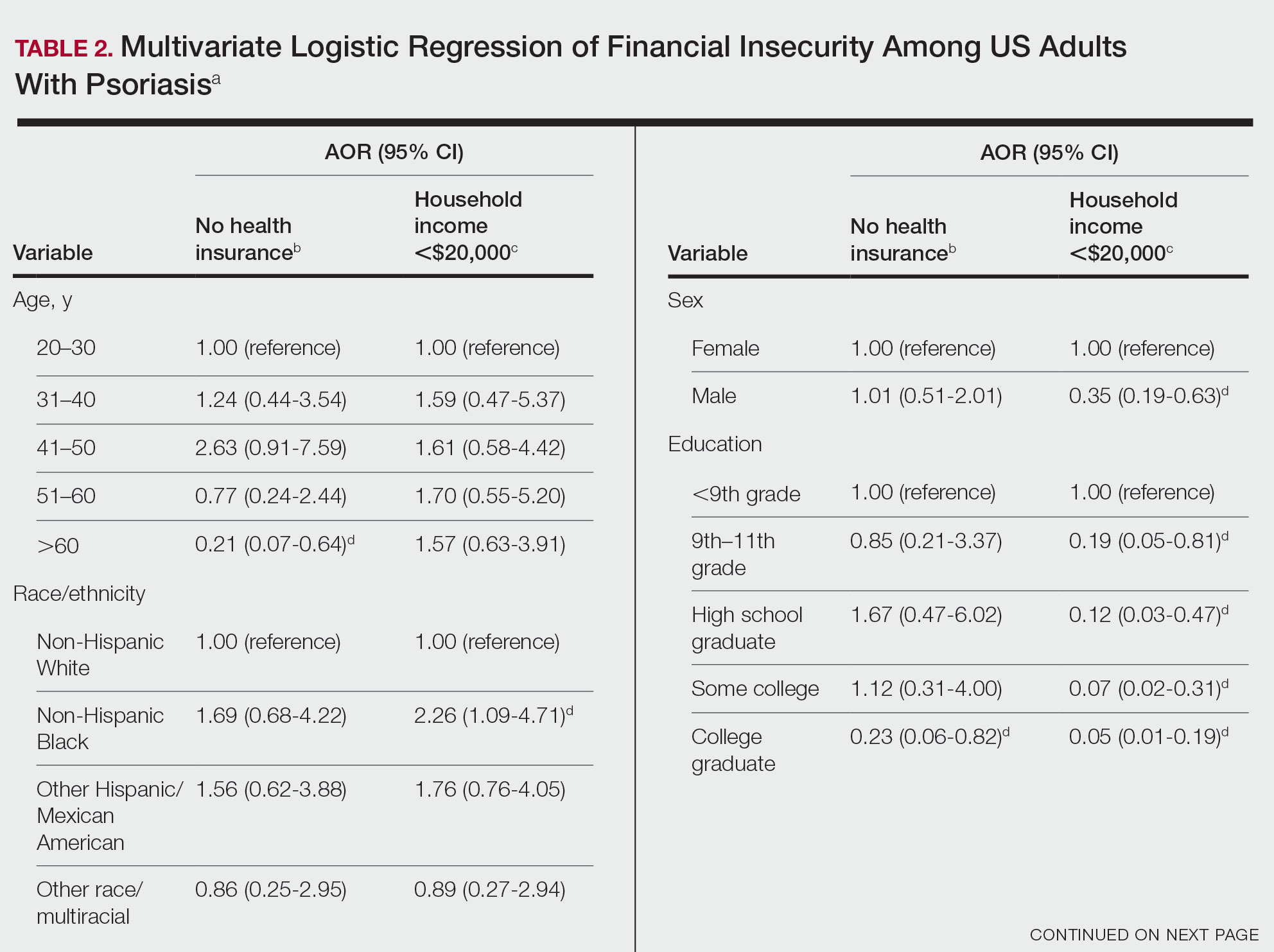

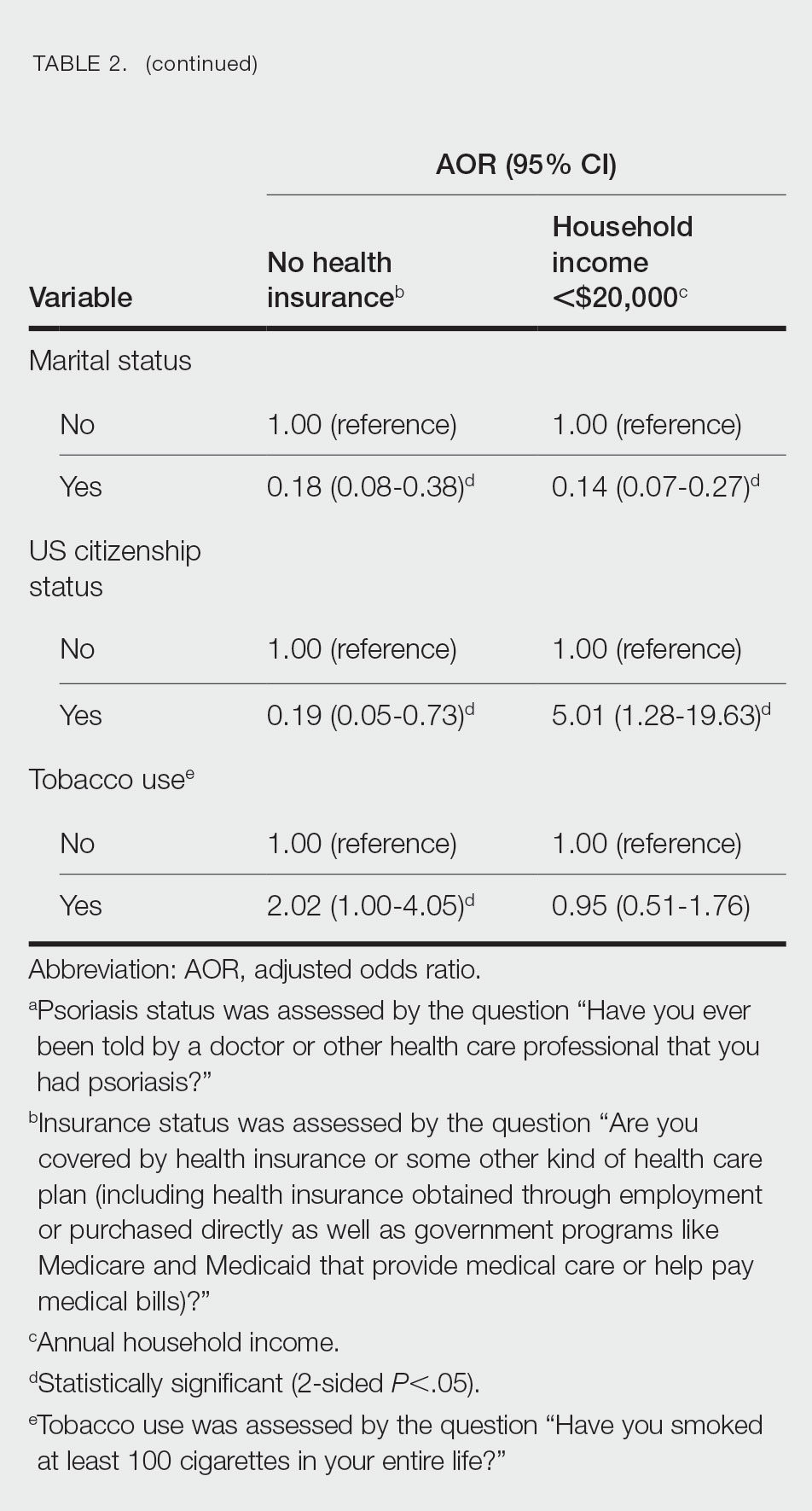

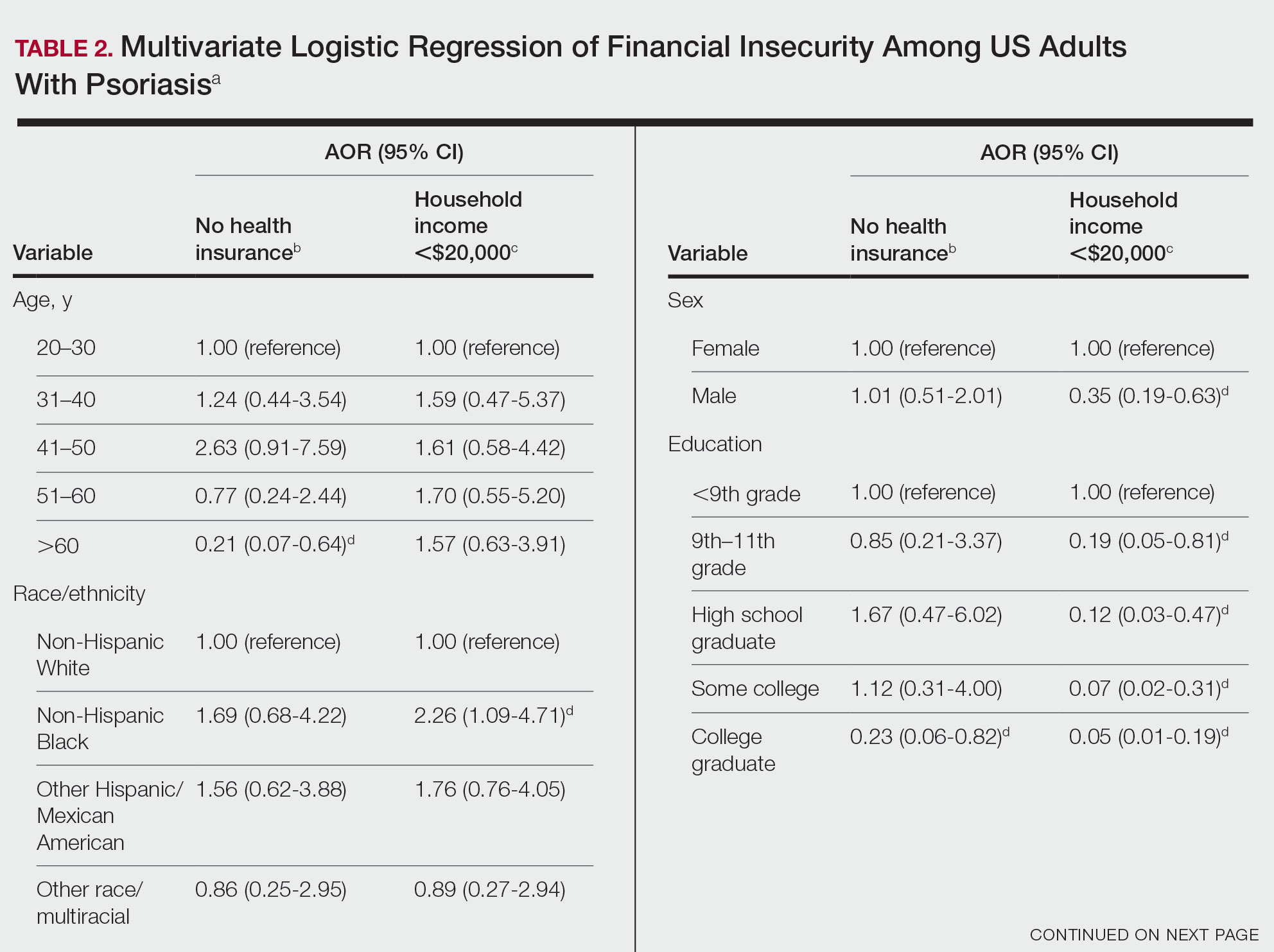

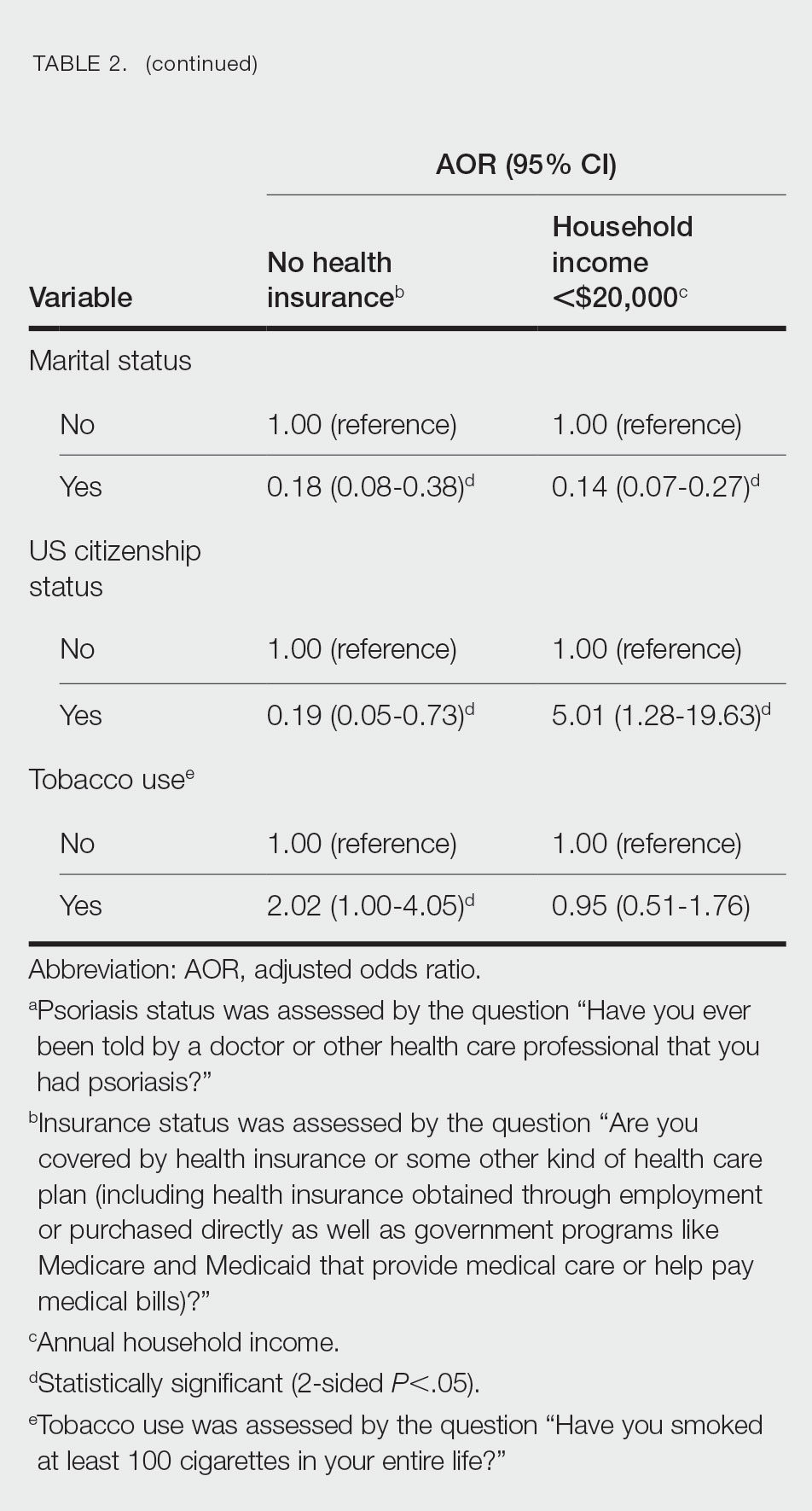

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

Practice Points

- The economic burden on patients with psoriasis has been rising over time, as the disease impacts many aspects of patients’ lives.

- Various sociodemographic groups among patients with psoriasis are financially insecure. Knowing which groups are at higher risk for poor outcomes due to financial insecurity can assist with appropriate treatment regimens.

Association Between Psoriasis and Obesity Among US Adults in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

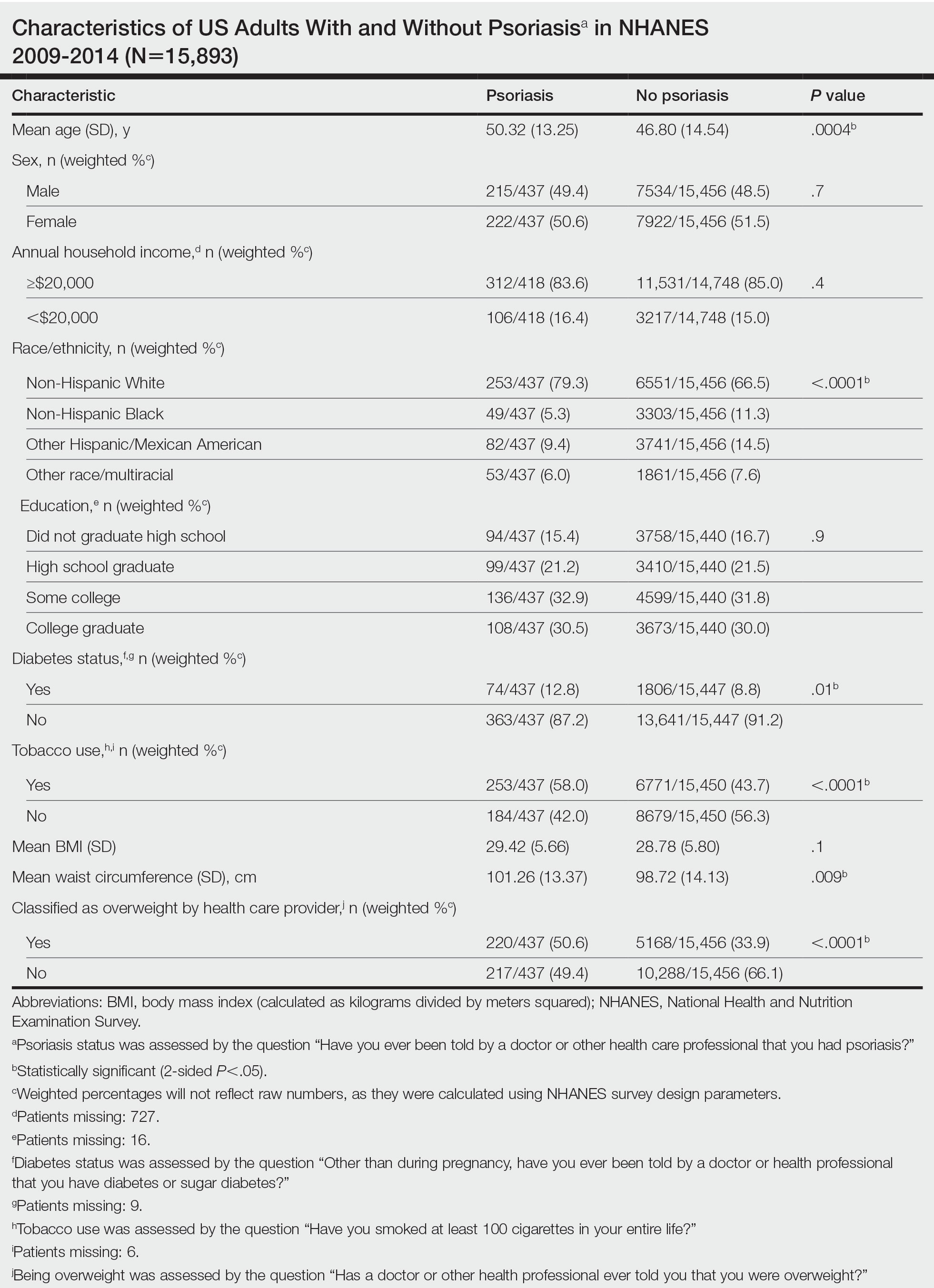

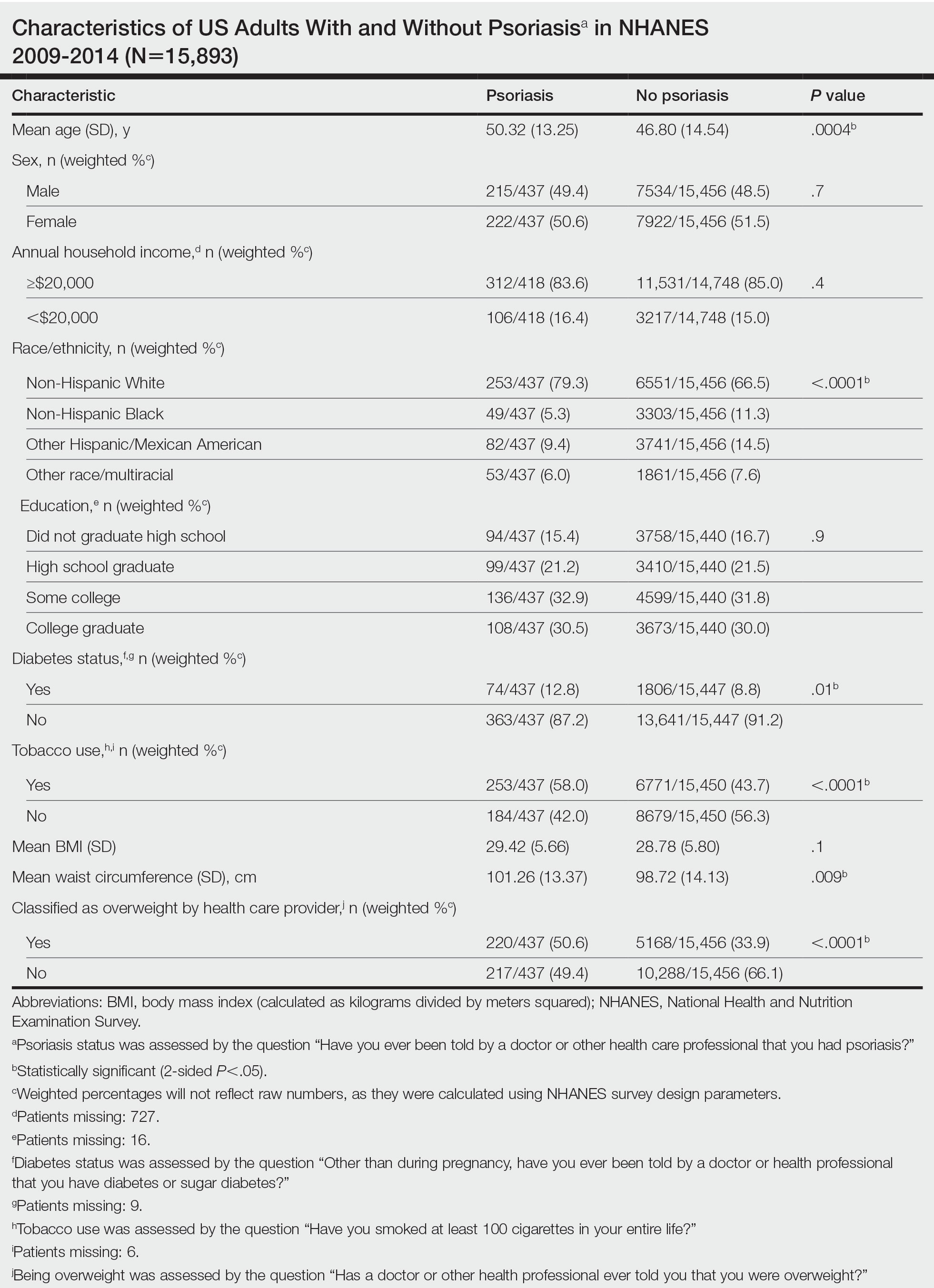

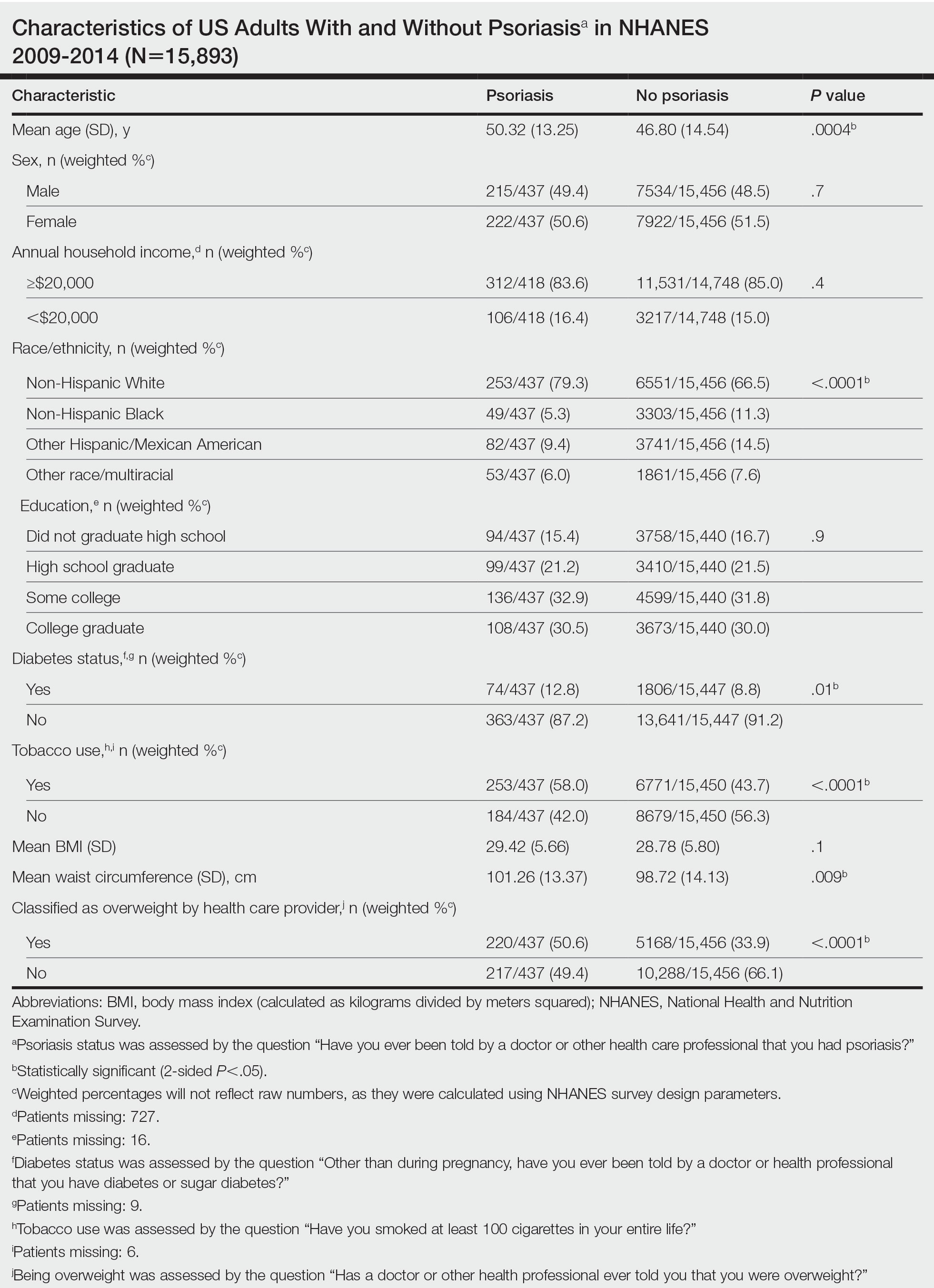

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

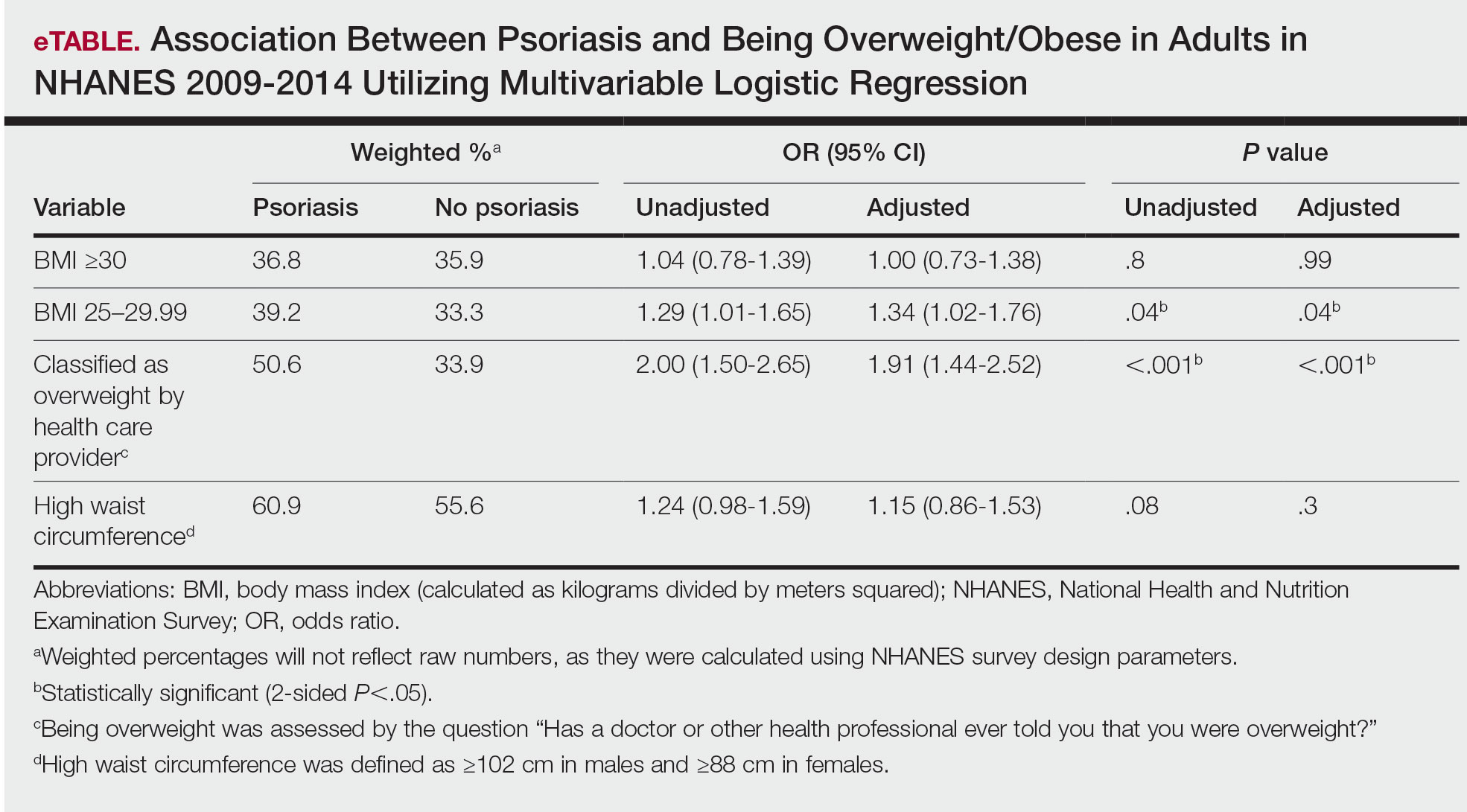

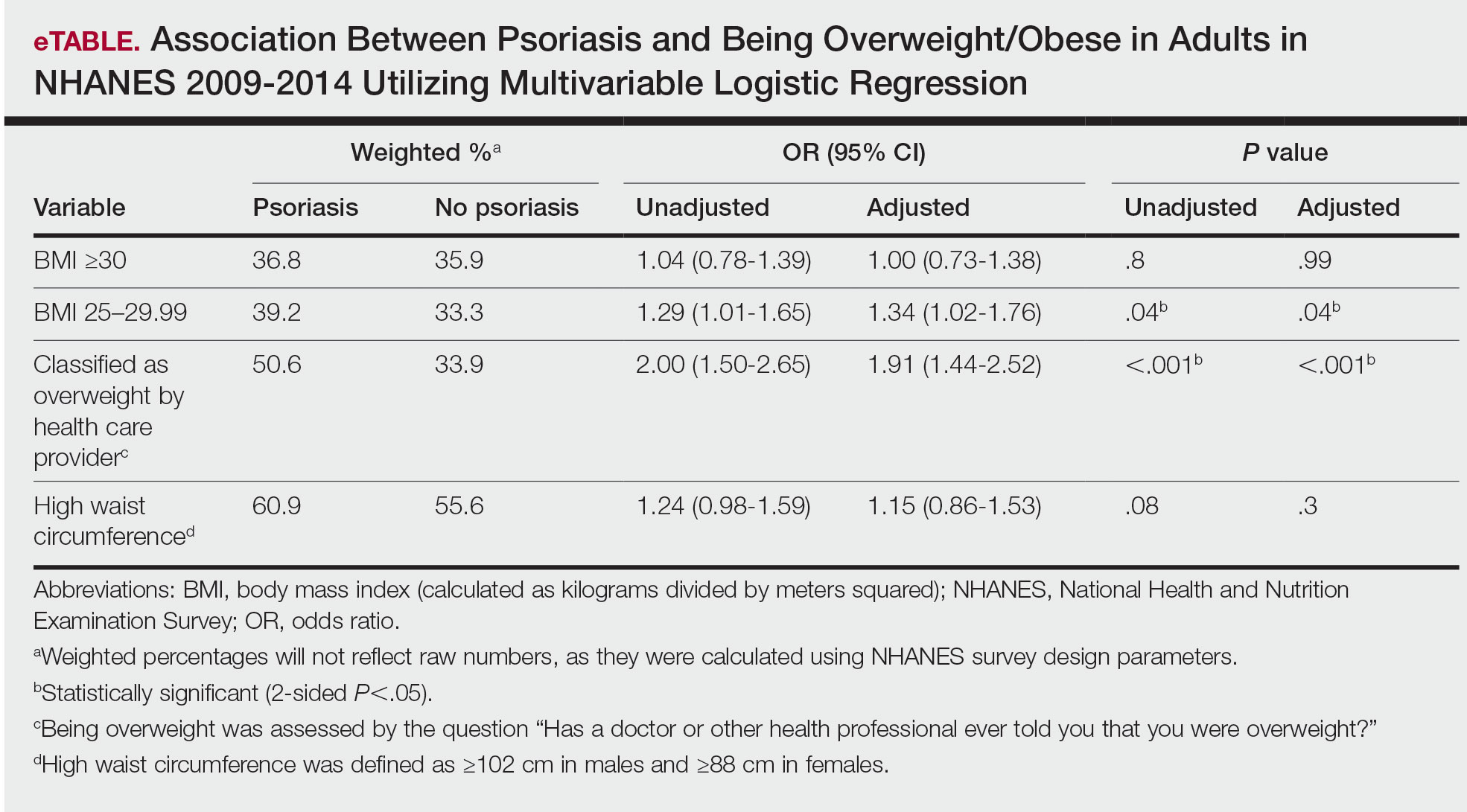

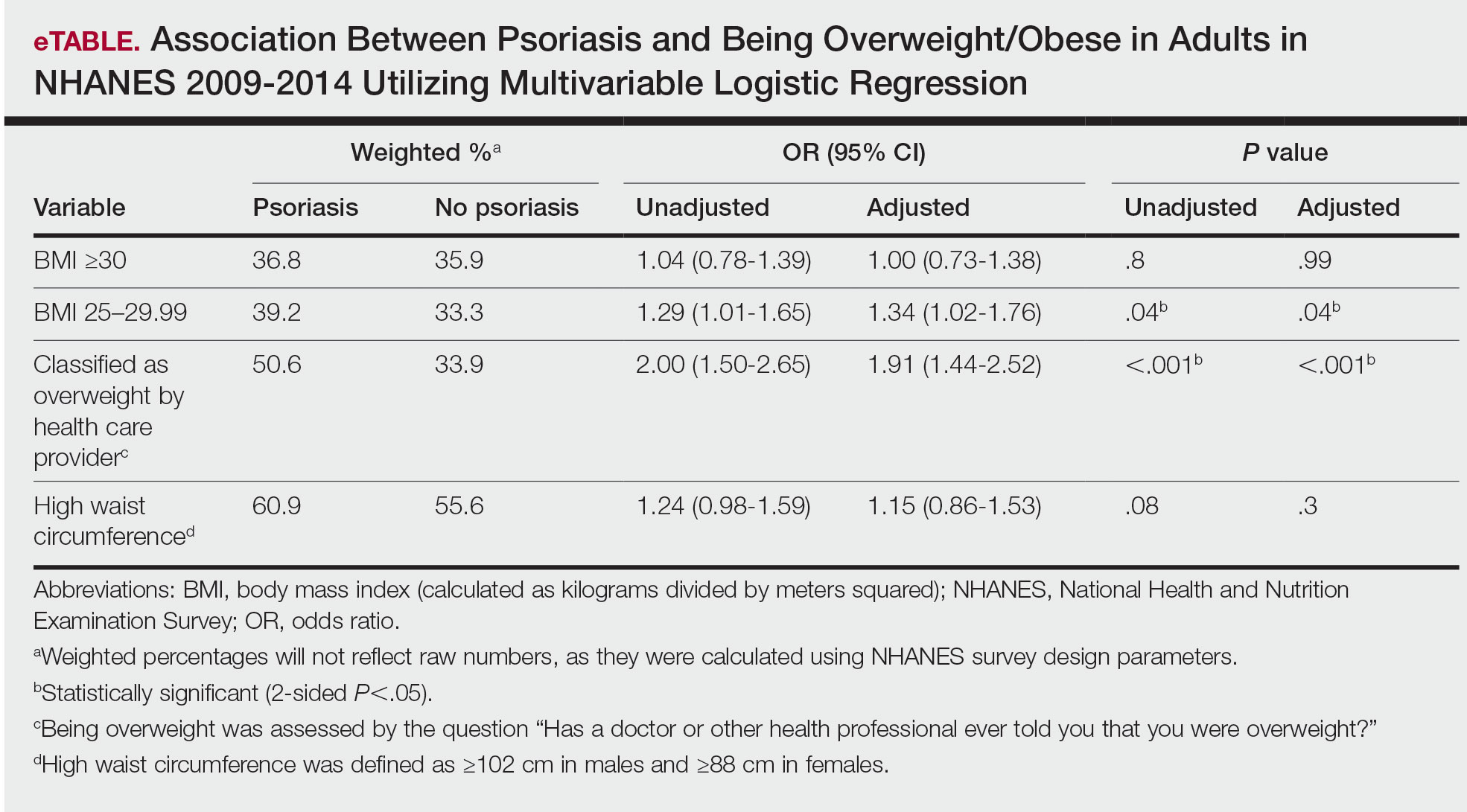

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

Practice Points

- There are many comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis, making it crucial to evaluate for these diseases in patients with psoriasis.

- Obesity may be a contributing factor to psoriasis development due to the role of IL-17 secretion.