User login

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Skin Cancer

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

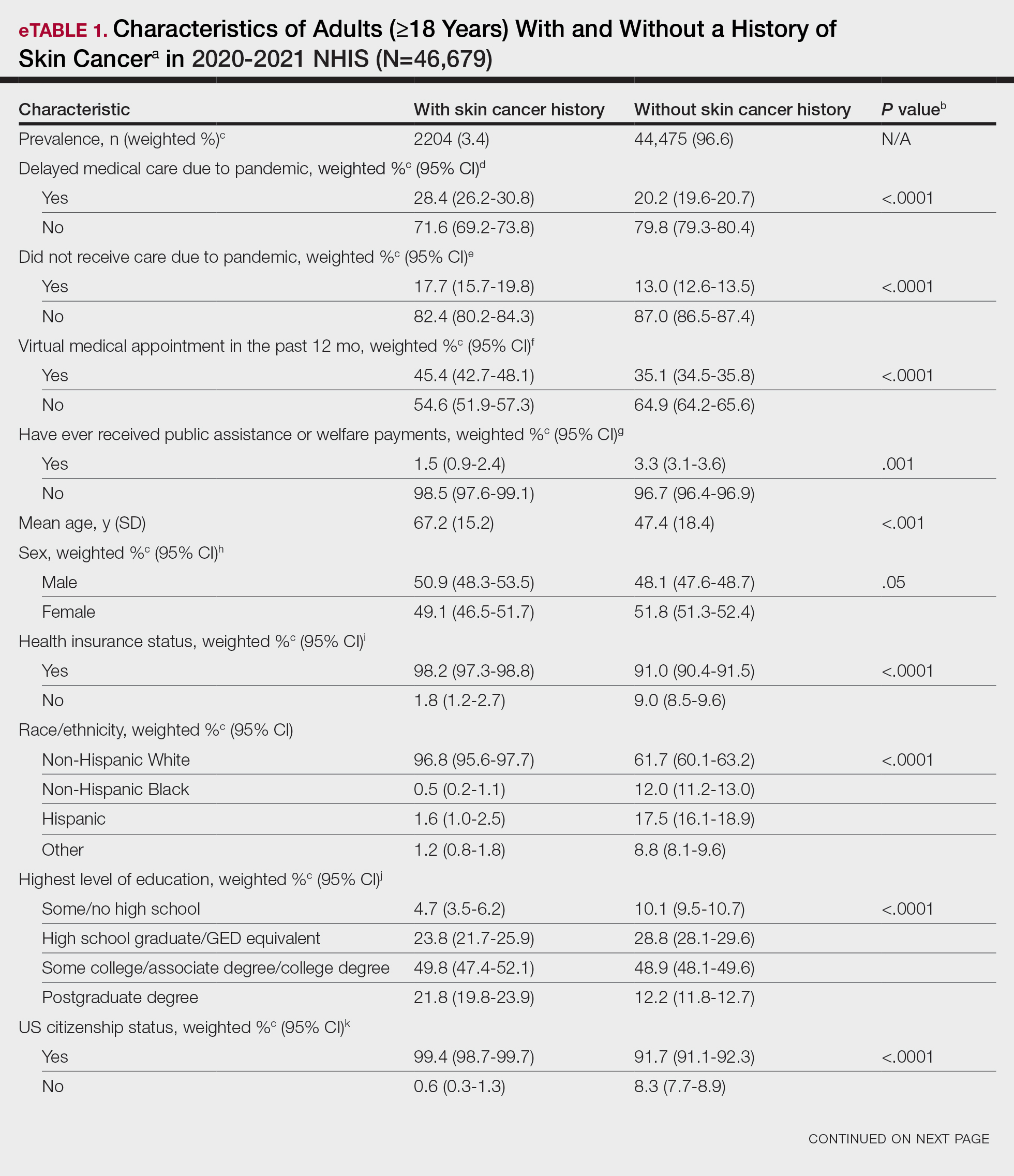

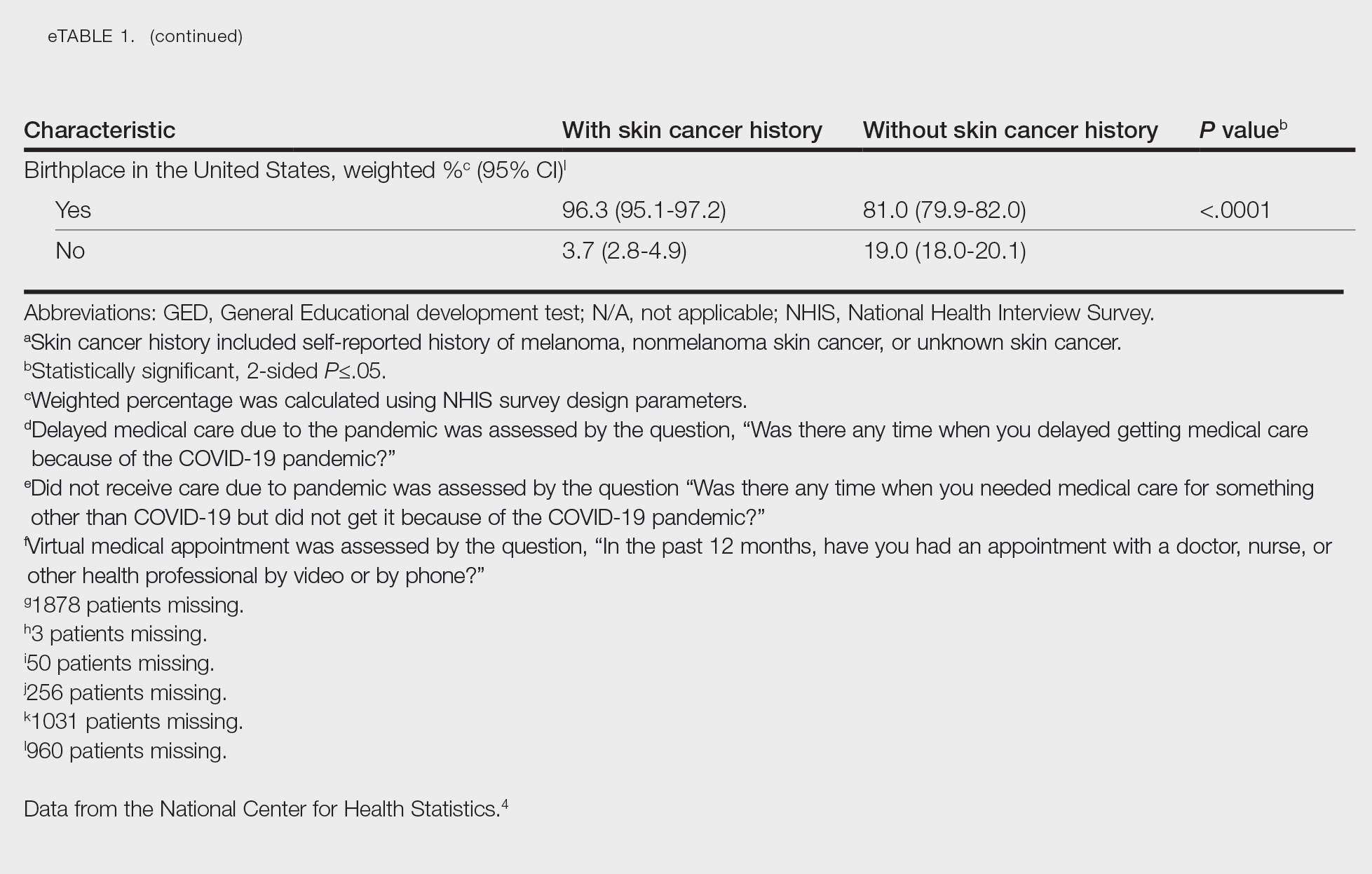

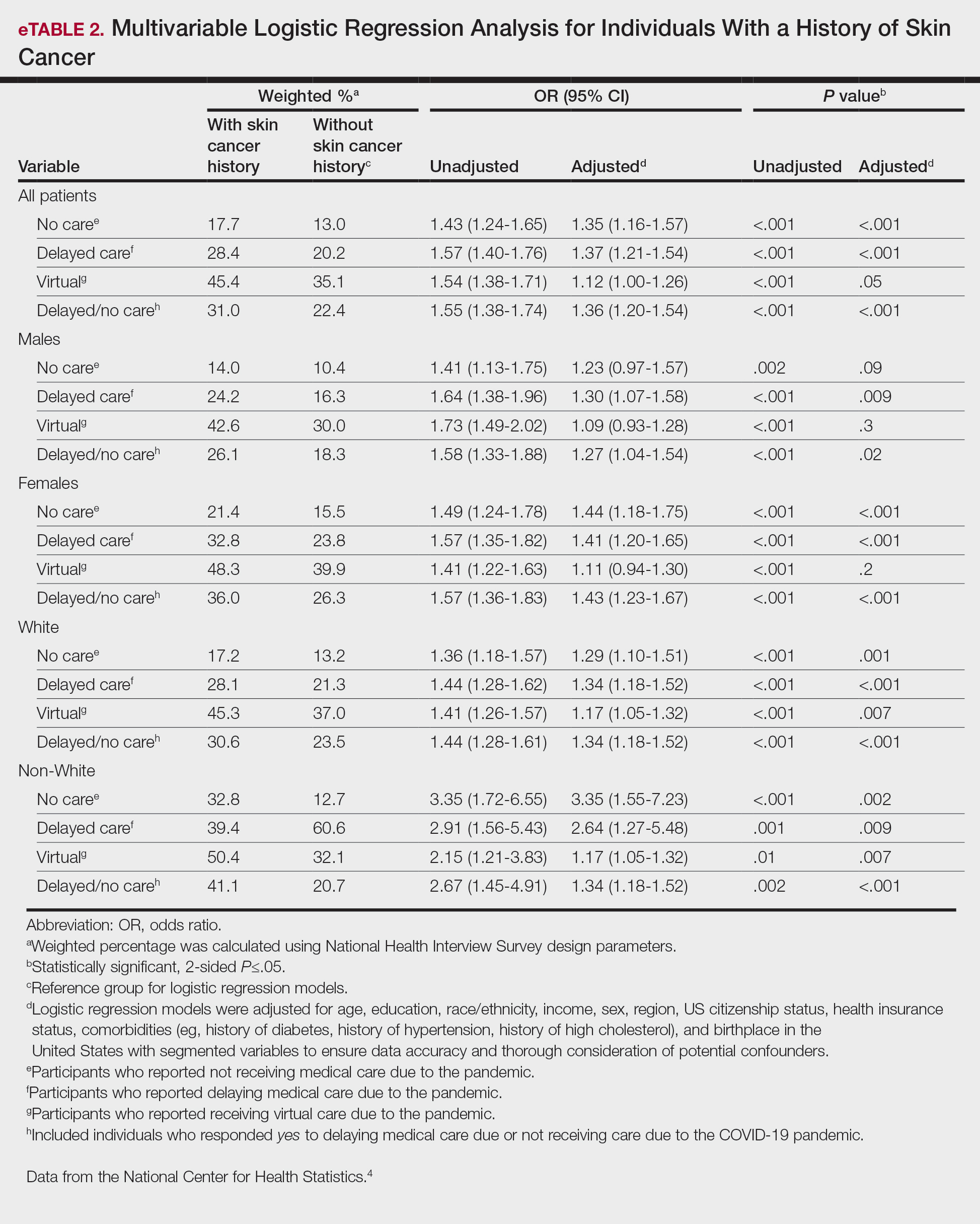

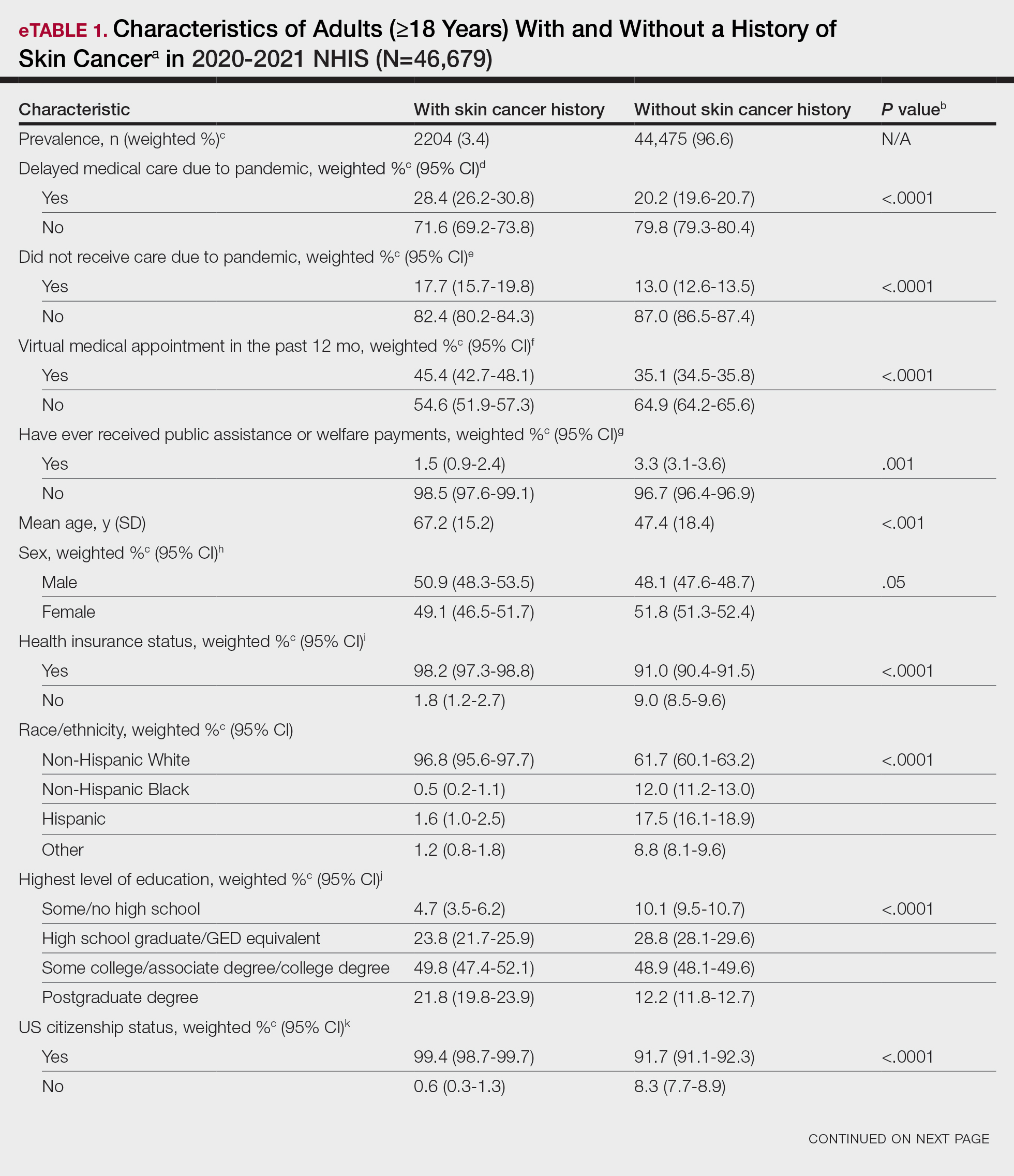

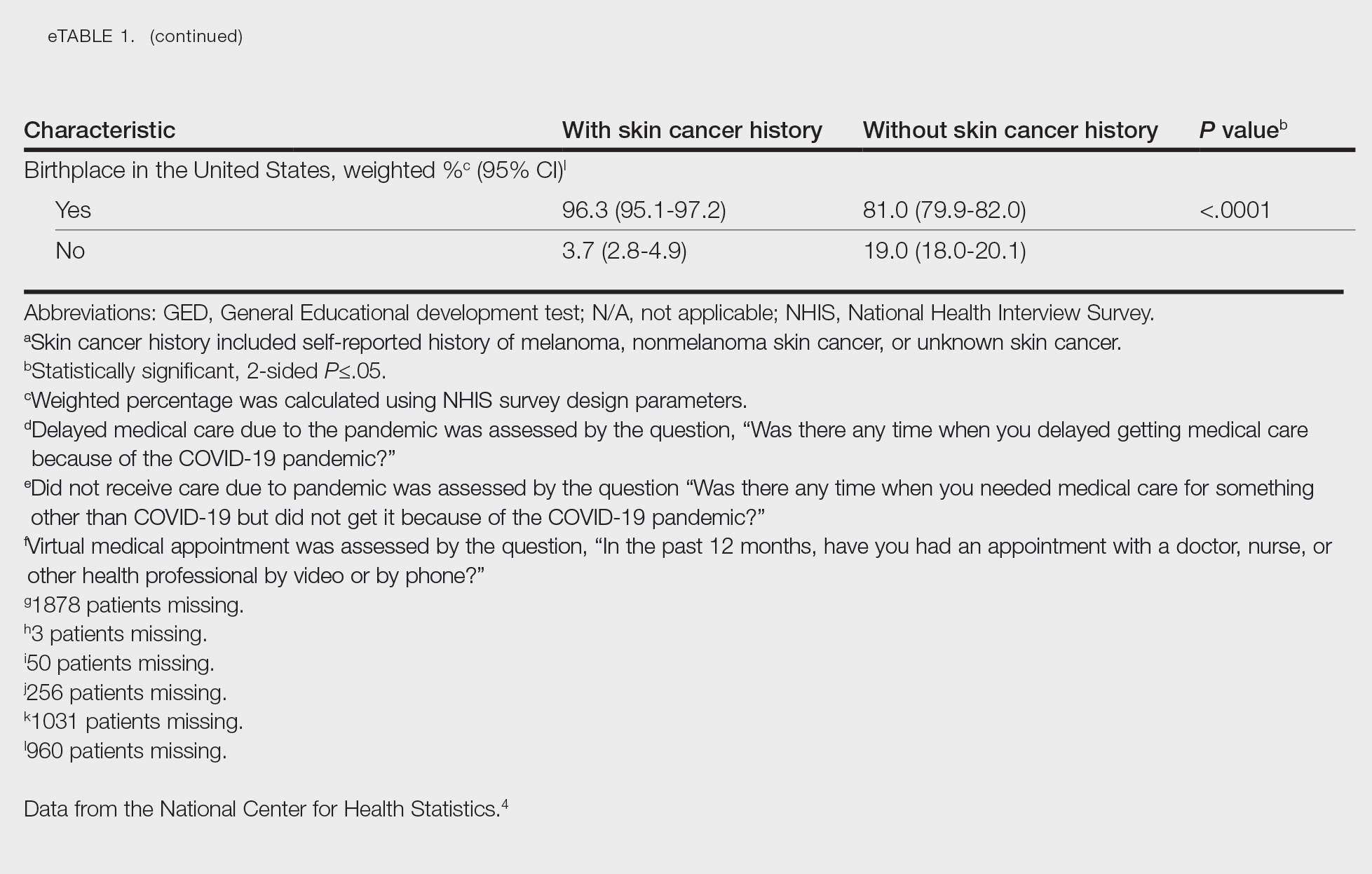

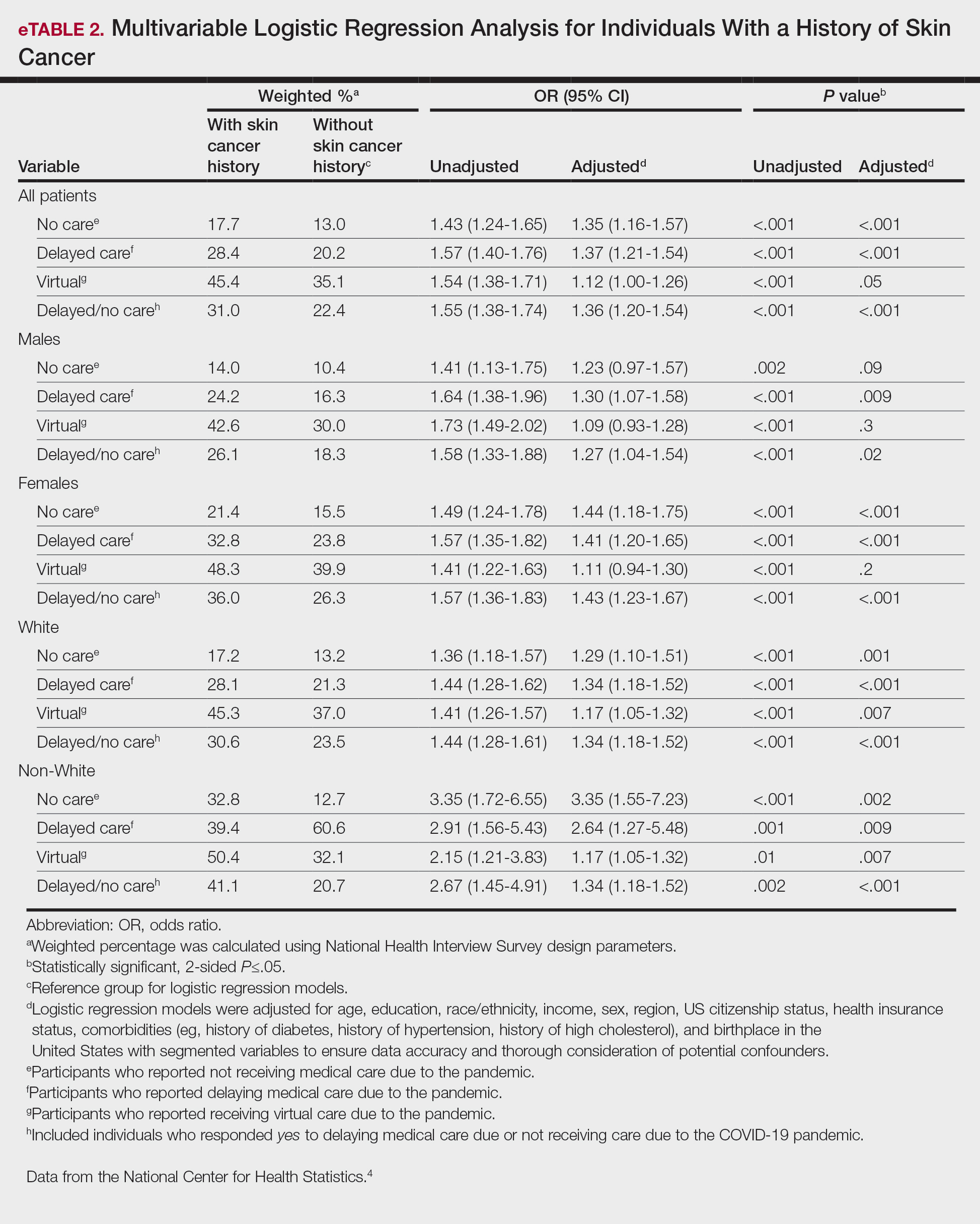

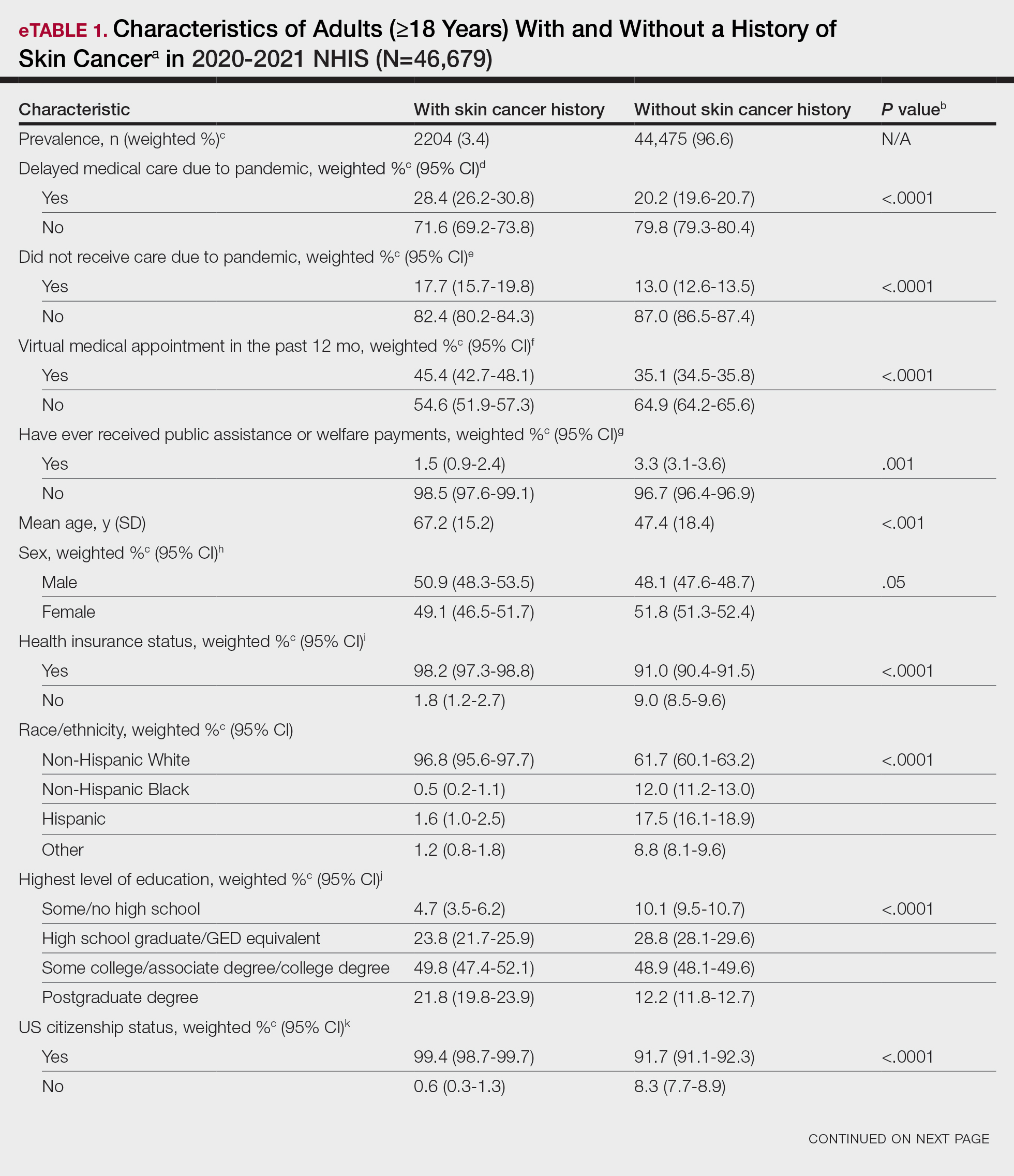

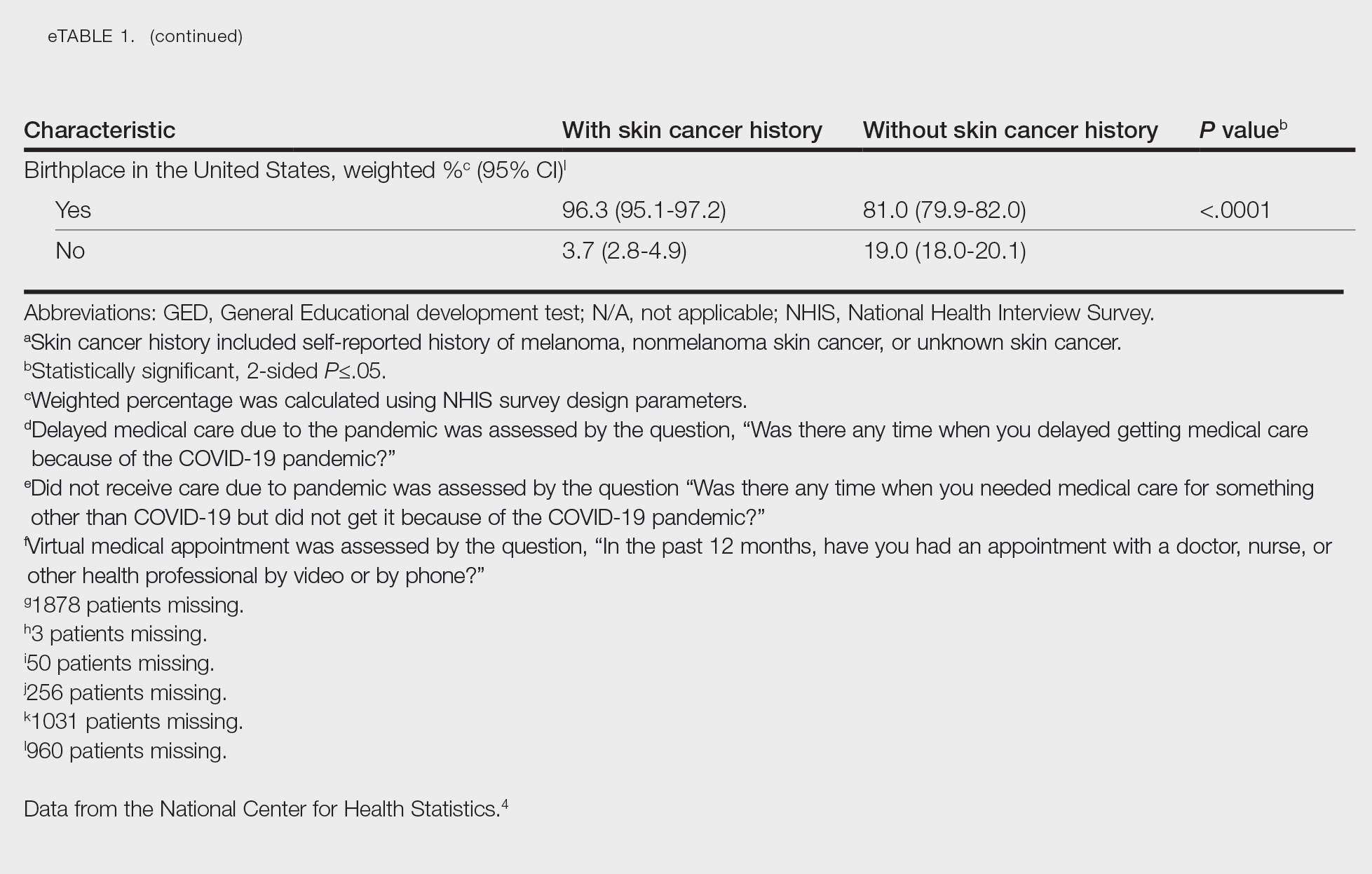

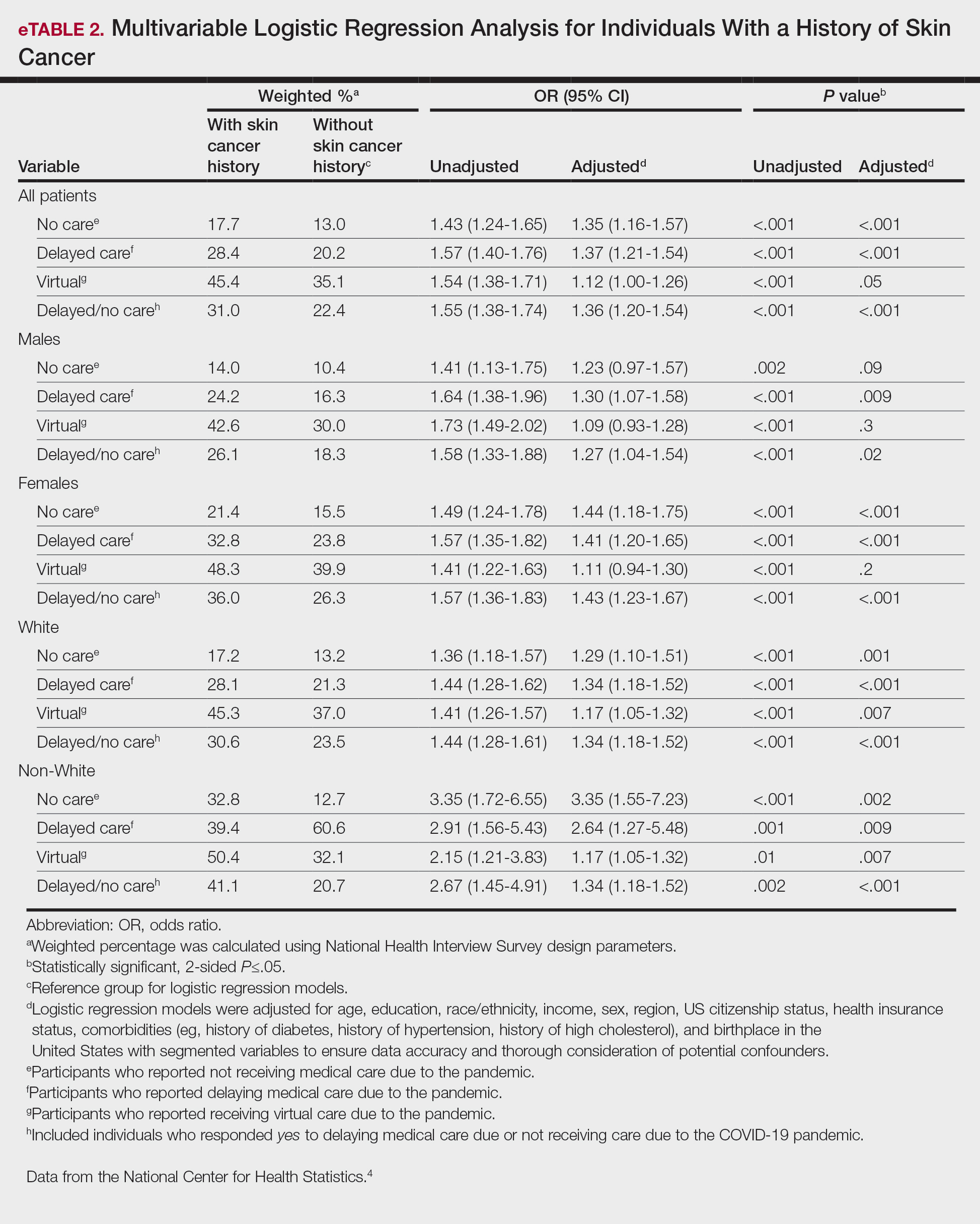

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

PRACTICE POINTS

- The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the landscape of medicine, as many individuals are now utilizing telemedicine to receive care.

- Many individuals will continue to receive telemedicine moving forward, making it crucial to understand access to care.

Risk for COVID-19 Infection in Patients With Vitiligo

To the Editor:

Vitiligo is a depigmentation disorder that results from the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis.1 The most widely accepted pathophysiology for melanocyte destruction in vitiligo is an autoimmune process involving dysregulated cytokine production and autoreactive T-cell activation.1 Individuals with cutaneous autoinflammatory conditions currently are vital patient populations warranting research, as their susceptibility to COVID-19 infection may differ from the general population. We previously found a small increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis,2 which suggests that other dermatologic conditions also may impact COVID-19 risk. The risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo remains largely unknown. In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated the risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo compared with those without vitiligo utilizing claims data from the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/).

Claims were evaluated for patients aged 3 years and older with a vitiligo diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code L80) that was made between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2020. Individuals without a vitiligo diagnosis during the same period were placed (4:1 ratio) in the control group and were matched with study group patients for age and sex. All comorbidity variables and vitiligo diagnoses were extracted from ICD-10 codes that were given prior to a diagnosis of COVID-19. We then constructed multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for measured confounders to evaluate if vitiligo was associated with higher risk for COVID-19 infection after January 1, 2020.

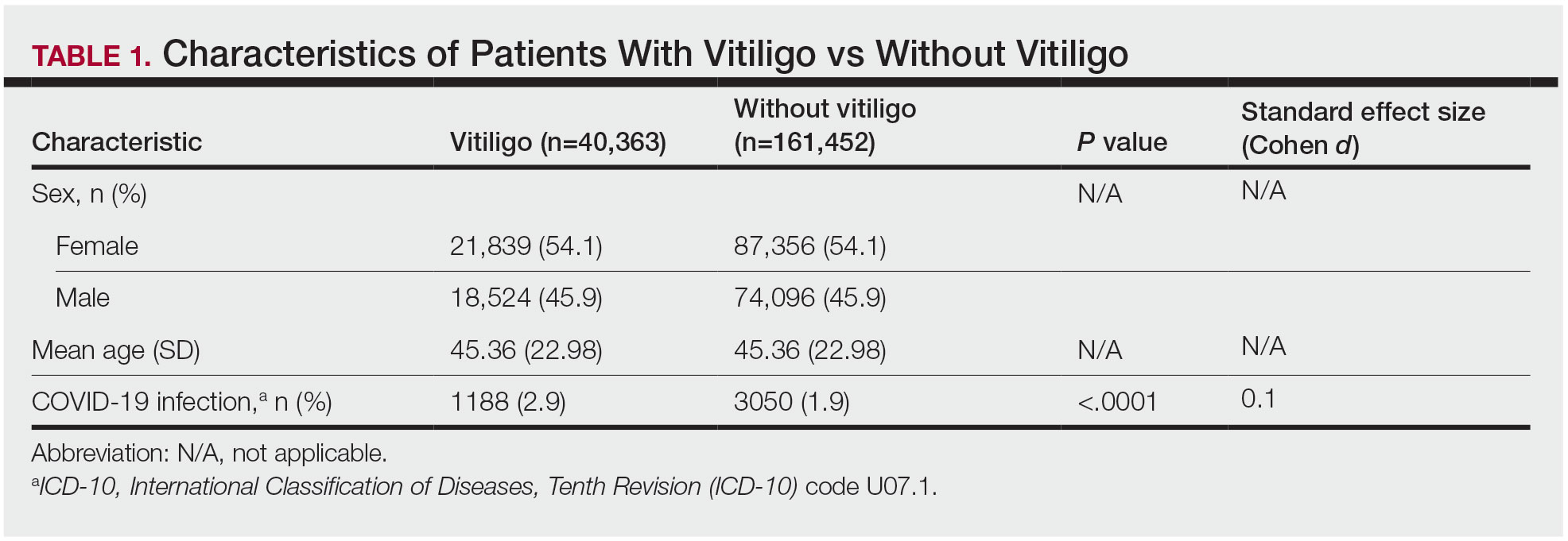

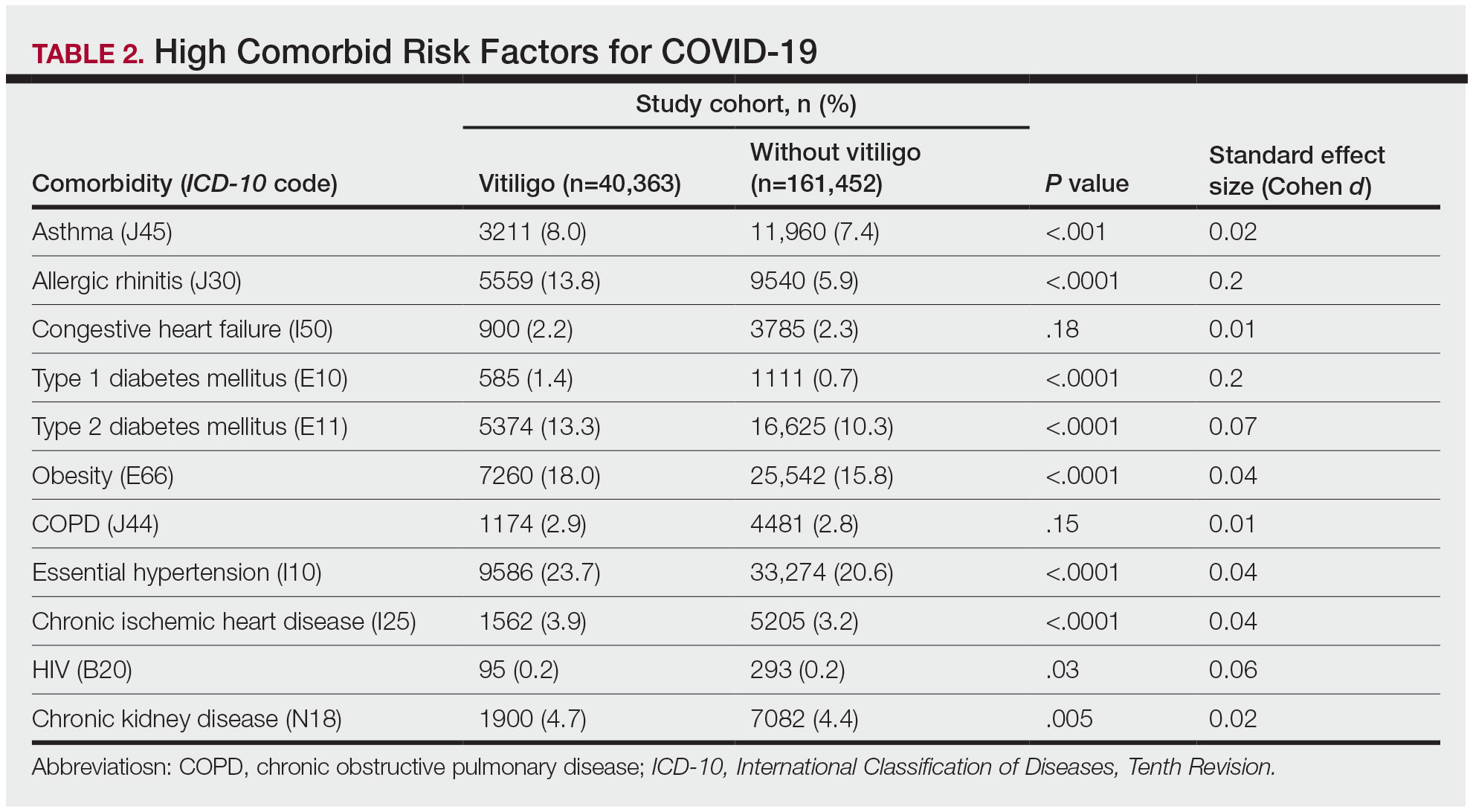

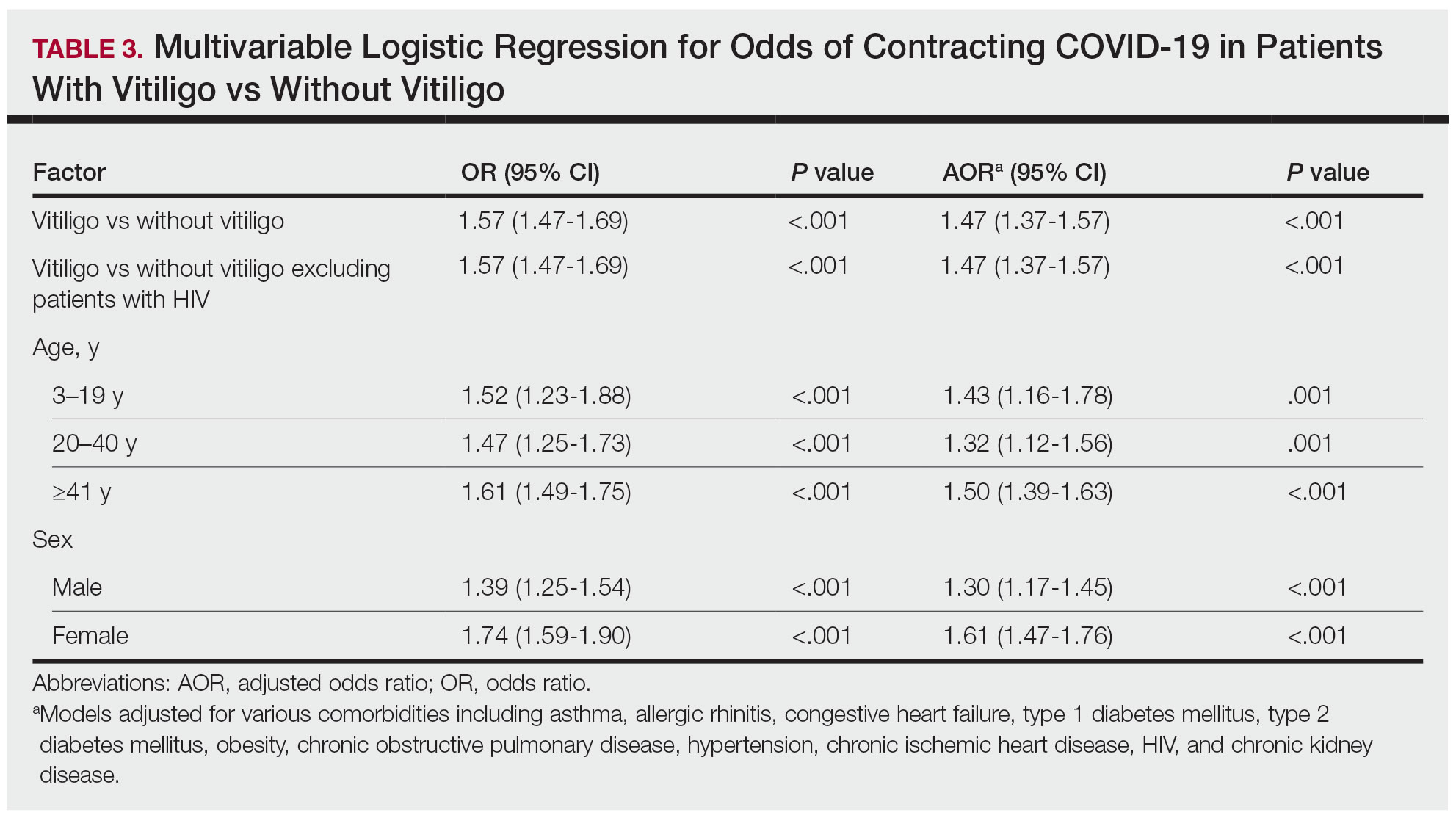

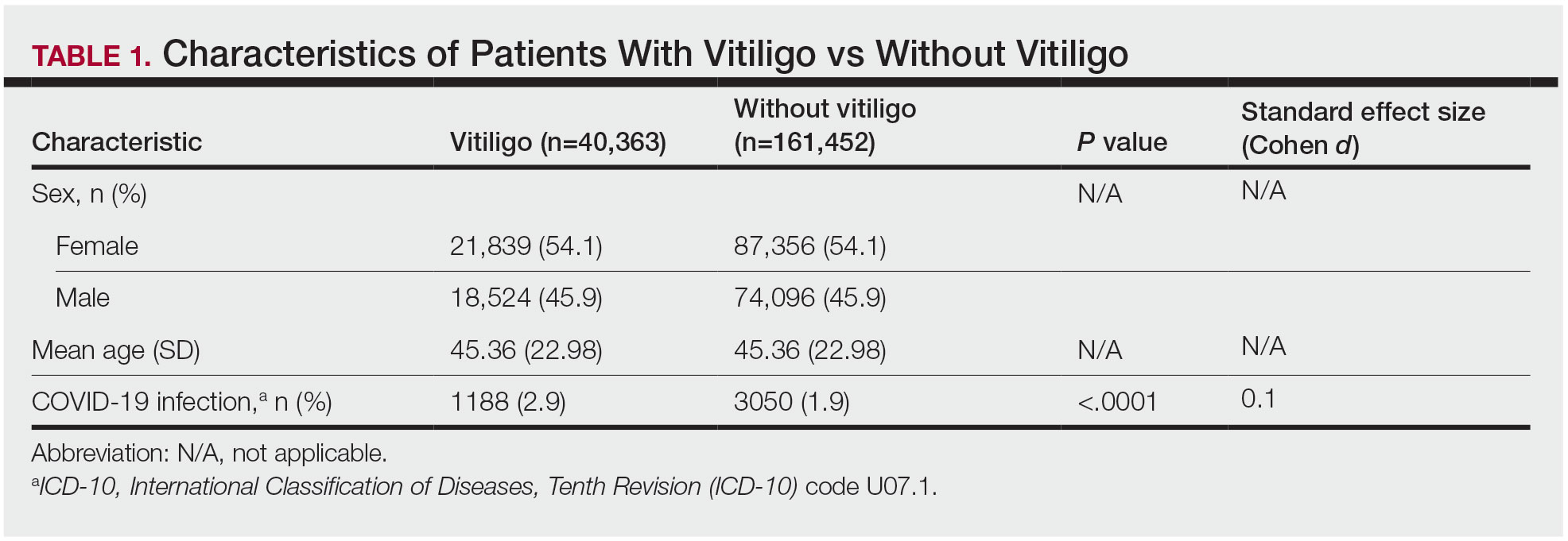

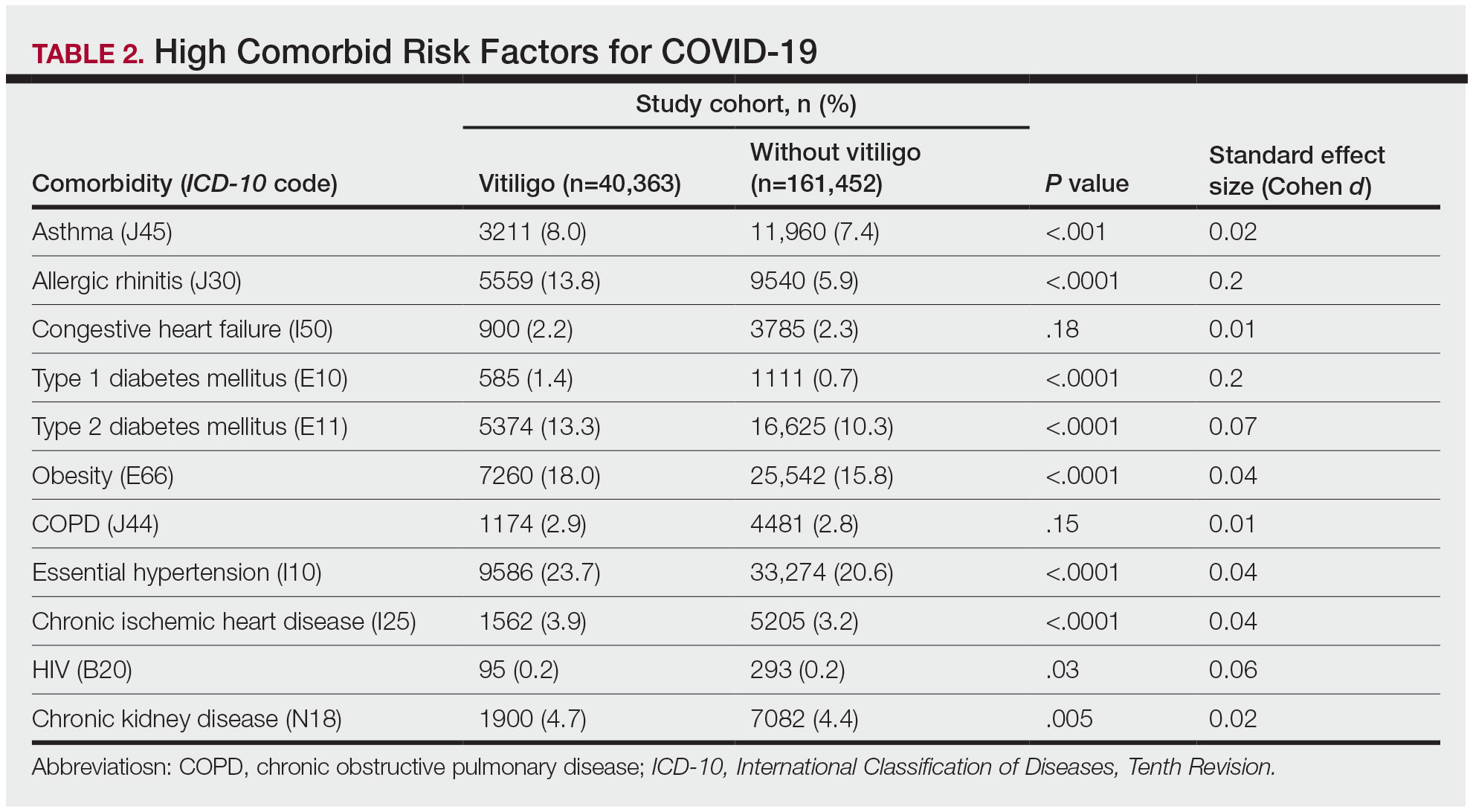

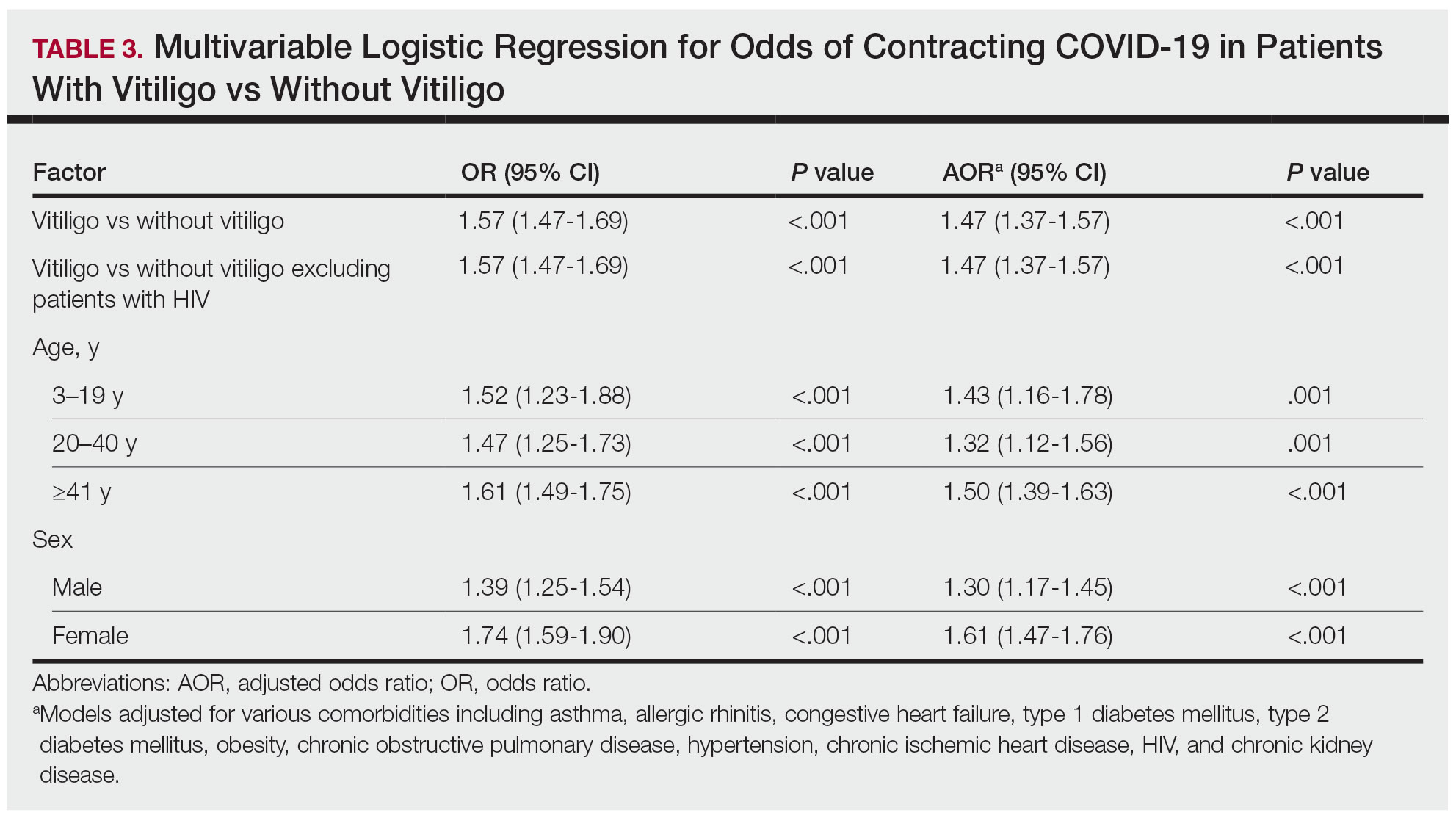

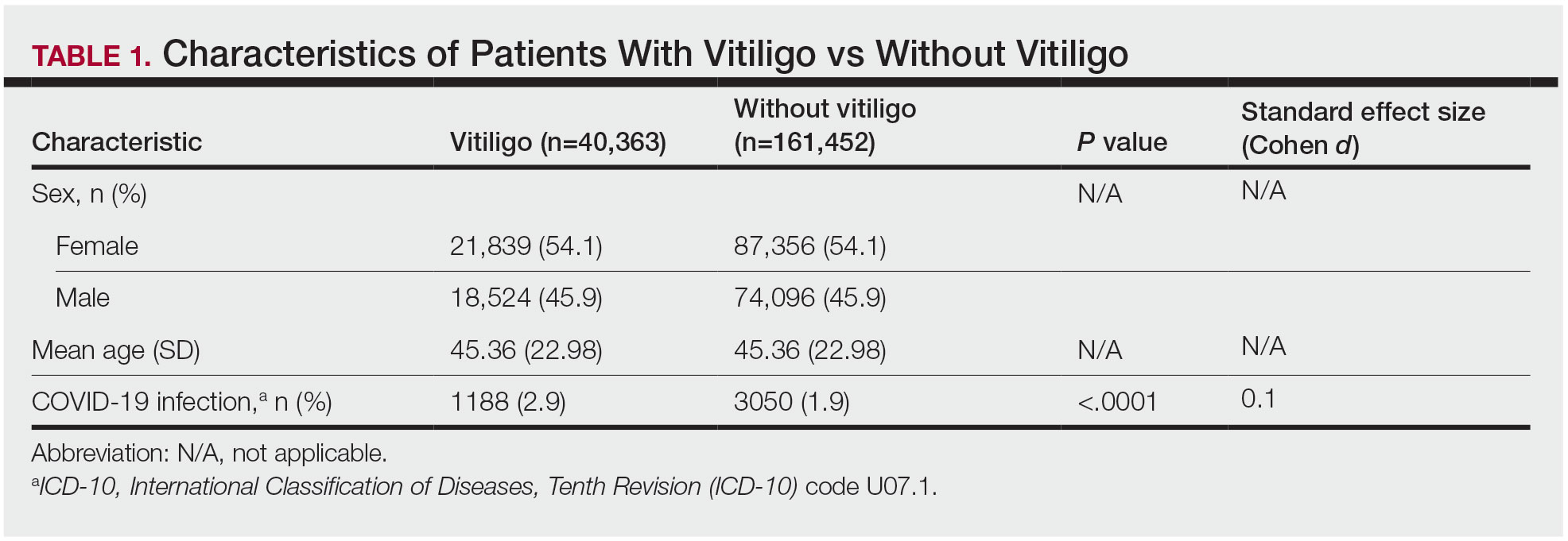

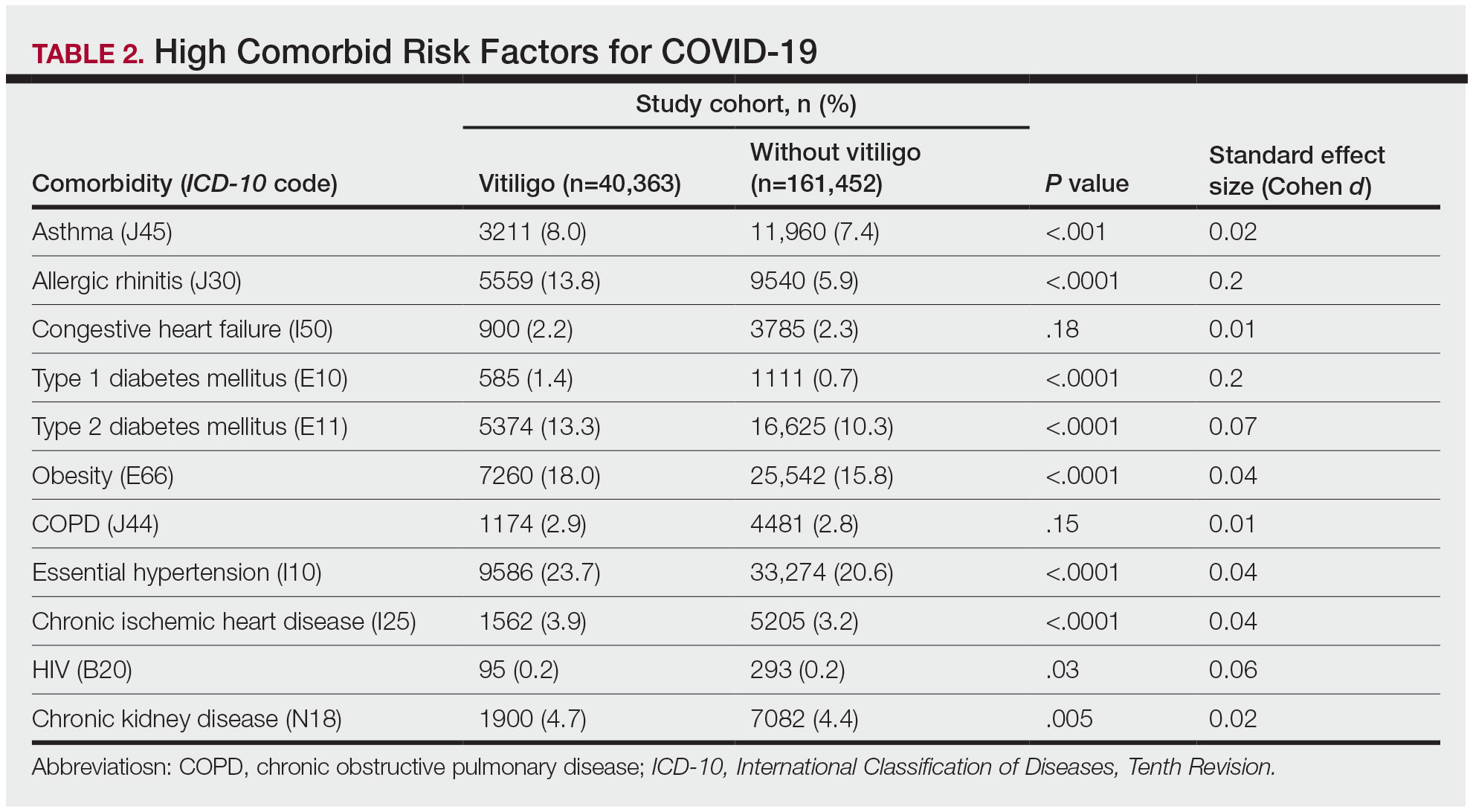

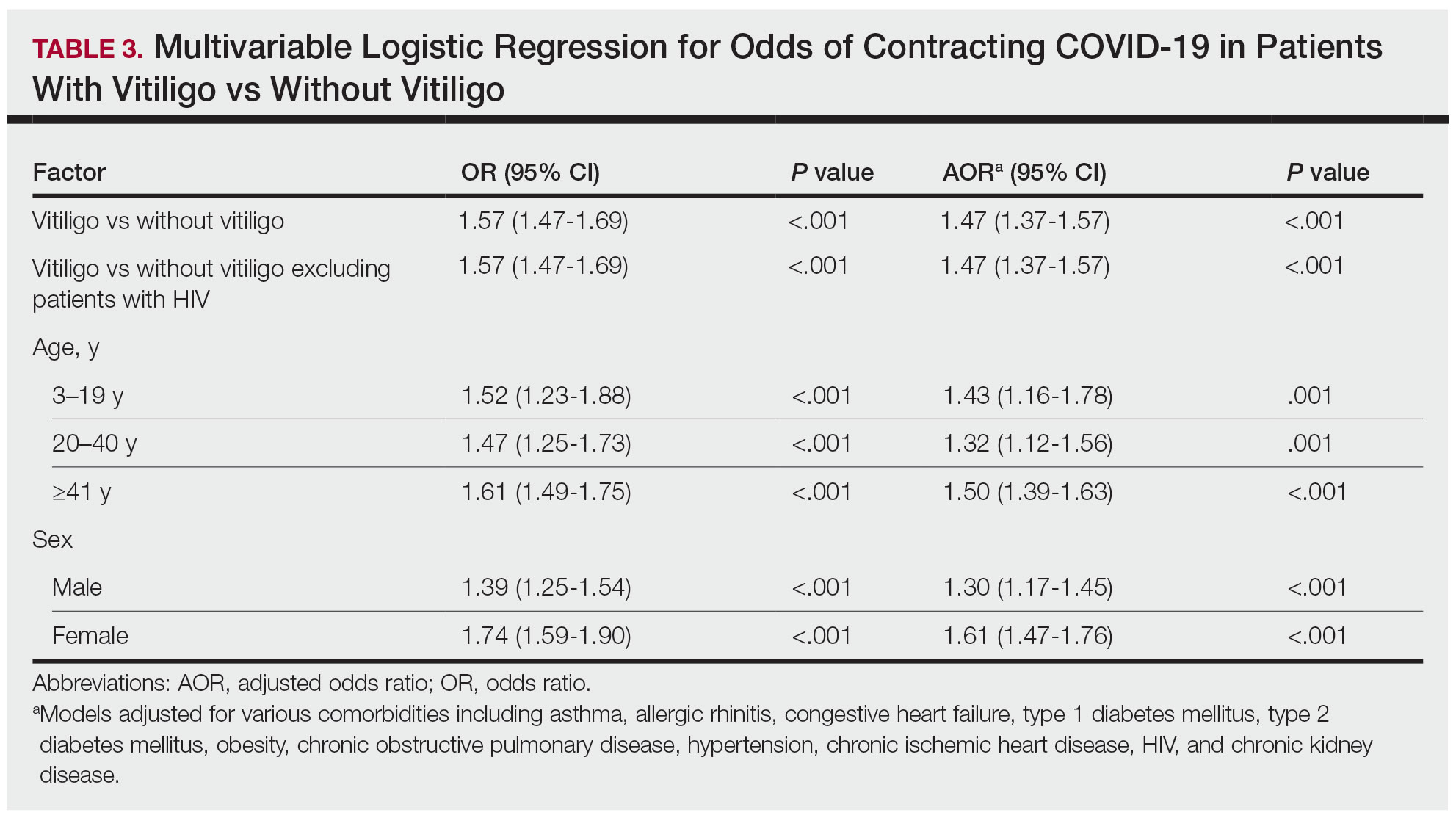

The vitiligo and nonvitiligo cohorts included 40,363 and 161,452 patients, respectively (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis with adjustment for confounding variables, including high comorbid risk factors (Table 2) revealed that patients with a diagnosis of vitiligo had significantly increased odds of COVID-19 infection compared with patients without vitiligo (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.37-1.57; P<.001)(Table 3). Additionally, subgroup logistic analyses for sex, age, and exclusion of patients who were HIV positive revealed that females with vitiligo had higher odds of contracting COVID-19 than males with vitiligo (Table 3).

Our results showed that patients with vitiligo had a higher relative risk for contracting COVID-19 than individuals without vitiligo. It has been reported that the prevalence of COVID-19 is higher among patients with autoimmune diseases compared to the general population.3 Additionally, a handful of vitiligo patients are managed with immunosuppressive agents that may further weaken their immune response.1 Moreover, survey results from dermatologists managing vitiligo patients revealed that physicians were fairly comfortable prescribing immunosuppressants and encouraging in-office phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 As a result, more patients may have been attending in-office visits for their phototherapy, which may have increased their risk for COVID-19. Although these factors play a role in COVID-19 infection rates, the underlying immune dysregulation in vitiligo in relation to COVID-19 remains unknown and should be further explored.

Our findings are limited by the use of ICD-10 codes, the inability to control for all potential confounding variables, the lack of data regarding the stage of vitiligo, and the absence of data for undiagnosed COVID-19 infections. In addition, patients with vitiligo may be more likely to seek care, potentially increasing their rates of COVID-19 testing. The inability to identify the stage of vitiligo during enrollment in the database may have altered our results, as individuals with active disease have increased levels of IFN-γ. Increased secretion of IFN-γ also potentially helps in the clearance of COVID-19 infection.1 Future studies should investigate this relationship via planned COVID-19 testing, identification of vitiligo stage, and controlling for other associated comorbidities.

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Wu JJ, Liu J, Thatiparthi A, et al. The risk of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis—a retrospective cohort study [published online September 20, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.040

- Zhong J, Shen G, Yang H, et al. COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease in Hubei province, China: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:E557-E564. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30227-7

- Chatterjee M, Das A. Management of vitiligo amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey and resulting consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:479-483. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_859_20

To the Editor:

Vitiligo is a depigmentation disorder that results from the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis.1 The most widely accepted pathophysiology for melanocyte destruction in vitiligo is an autoimmune process involving dysregulated cytokine production and autoreactive T-cell activation.1 Individuals with cutaneous autoinflammatory conditions currently are vital patient populations warranting research, as their susceptibility to COVID-19 infection may differ from the general population. We previously found a small increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis,2 which suggests that other dermatologic conditions also may impact COVID-19 risk. The risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo remains largely unknown. In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated the risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo compared with those without vitiligo utilizing claims data from the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/).

Claims were evaluated for patients aged 3 years and older with a vitiligo diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code L80) that was made between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2020. Individuals without a vitiligo diagnosis during the same period were placed (4:1 ratio) in the control group and were matched with study group patients for age and sex. All comorbidity variables and vitiligo diagnoses were extracted from ICD-10 codes that were given prior to a diagnosis of COVID-19. We then constructed multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for measured confounders to evaluate if vitiligo was associated with higher risk for COVID-19 infection after January 1, 2020.

The vitiligo and nonvitiligo cohorts included 40,363 and 161,452 patients, respectively (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis with adjustment for confounding variables, including high comorbid risk factors (Table 2) revealed that patients with a diagnosis of vitiligo had significantly increased odds of COVID-19 infection compared with patients without vitiligo (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.37-1.57; P<.001)(Table 3). Additionally, subgroup logistic analyses for sex, age, and exclusion of patients who were HIV positive revealed that females with vitiligo had higher odds of contracting COVID-19 than males with vitiligo (Table 3).

Our results showed that patients with vitiligo had a higher relative risk for contracting COVID-19 than individuals without vitiligo. It has been reported that the prevalence of COVID-19 is higher among patients with autoimmune diseases compared to the general population.3 Additionally, a handful of vitiligo patients are managed with immunosuppressive agents that may further weaken their immune response.1 Moreover, survey results from dermatologists managing vitiligo patients revealed that physicians were fairly comfortable prescribing immunosuppressants and encouraging in-office phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 As a result, more patients may have been attending in-office visits for their phototherapy, which may have increased their risk for COVID-19. Although these factors play a role in COVID-19 infection rates, the underlying immune dysregulation in vitiligo in relation to COVID-19 remains unknown and should be further explored.

Our findings are limited by the use of ICD-10 codes, the inability to control for all potential confounding variables, the lack of data regarding the stage of vitiligo, and the absence of data for undiagnosed COVID-19 infections. In addition, patients with vitiligo may be more likely to seek care, potentially increasing their rates of COVID-19 testing. The inability to identify the stage of vitiligo during enrollment in the database may have altered our results, as individuals with active disease have increased levels of IFN-γ. Increased secretion of IFN-γ also potentially helps in the clearance of COVID-19 infection.1 Future studies should investigate this relationship via planned COVID-19 testing, identification of vitiligo stage, and controlling for other associated comorbidities.

To the Editor:

Vitiligo is a depigmentation disorder that results from the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis.1 The most widely accepted pathophysiology for melanocyte destruction in vitiligo is an autoimmune process involving dysregulated cytokine production and autoreactive T-cell activation.1 Individuals with cutaneous autoinflammatory conditions currently are vital patient populations warranting research, as their susceptibility to COVID-19 infection may differ from the general population. We previously found a small increased risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis,2 which suggests that other dermatologic conditions also may impact COVID-19 risk. The risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo remains largely unknown. In this retrospective cohort study, we investigated the risk for COVID-19 infection in patients with vitiligo compared with those without vitiligo utilizing claims data from the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/).

Claims were evaluated for patients aged 3 years and older with a vitiligo diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code L80) that was made between January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2020. Individuals without a vitiligo diagnosis during the same period were placed (4:1 ratio) in the control group and were matched with study group patients for age and sex. All comorbidity variables and vitiligo diagnoses were extracted from ICD-10 codes that were given prior to a diagnosis of COVID-19. We then constructed multivariable logistic regression models adjusting for measured confounders to evaluate if vitiligo was associated with higher risk for COVID-19 infection after January 1, 2020.

The vitiligo and nonvitiligo cohorts included 40,363 and 161,452 patients, respectively (Table 1). Logistic regression analysis with adjustment for confounding variables, including high comorbid risk factors (Table 2) revealed that patients with a diagnosis of vitiligo had significantly increased odds of COVID-19 infection compared with patients without vitiligo (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.47; 95% CI, 1.37-1.57; P<.001)(Table 3). Additionally, subgroup logistic analyses for sex, age, and exclusion of patients who were HIV positive revealed that females with vitiligo had higher odds of contracting COVID-19 than males with vitiligo (Table 3).

Our results showed that patients with vitiligo had a higher relative risk for contracting COVID-19 than individuals without vitiligo. It has been reported that the prevalence of COVID-19 is higher among patients with autoimmune diseases compared to the general population.3 Additionally, a handful of vitiligo patients are managed with immunosuppressive agents that may further weaken their immune response.1 Moreover, survey results from dermatologists managing vitiligo patients revealed that physicians were fairly comfortable prescribing immunosuppressants and encouraging in-office phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 As a result, more patients may have been attending in-office visits for their phototherapy, which may have increased their risk for COVID-19. Although these factors play a role in COVID-19 infection rates, the underlying immune dysregulation in vitiligo in relation to COVID-19 remains unknown and should be further explored.

Our findings are limited by the use of ICD-10 codes, the inability to control for all potential confounding variables, the lack of data regarding the stage of vitiligo, and the absence of data for undiagnosed COVID-19 infections. In addition, patients with vitiligo may be more likely to seek care, potentially increasing their rates of COVID-19 testing. The inability to identify the stage of vitiligo during enrollment in the database may have altered our results, as individuals with active disease have increased levels of IFN-γ. Increased secretion of IFN-γ also potentially helps in the clearance of COVID-19 infection.1 Future studies should investigate this relationship via planned COVID-19 testing, identification of vitiligo stage, and controlling for other associated comorbidities.

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Wu JJ, Liu J, Thatiparthi A, et al. The risk of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis—a retrospective cohort study [published online September 20, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.040

- Zhong J, Shen G, Yang H, et al. COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease in Hubei province, China: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:E557-E564. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30227-7

- Chatterjee M, Das A. Management of vitiligo amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey and resulting consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:479-483. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_859_20

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Wu JJ, Liu J, Thatiparthi A, et al. The risk of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis—a retrospective cohort study [published online September 20, 2022]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.040

- Zhong J, Shen G, Yang H, et al. COVID-19 in patients with rheumatic disease in Hubei province, China: a multicentre retrospective observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:E557-E564. doi:10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30227-7

- Chatterjee M, Das A. Management of vitiligo amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey and resulting consensus. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:479-483. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_859_20

Practice Points

- The underlying autoimmune process in vitiligo can result in various changes to the immune system.

- A diagnosis of vitiligo may alter the body’s immune response to COVID-19 infection.

Association Between Atopic Dermatitis and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among US Adults in the 1999-2006 NHANES Survey

To the Editor:

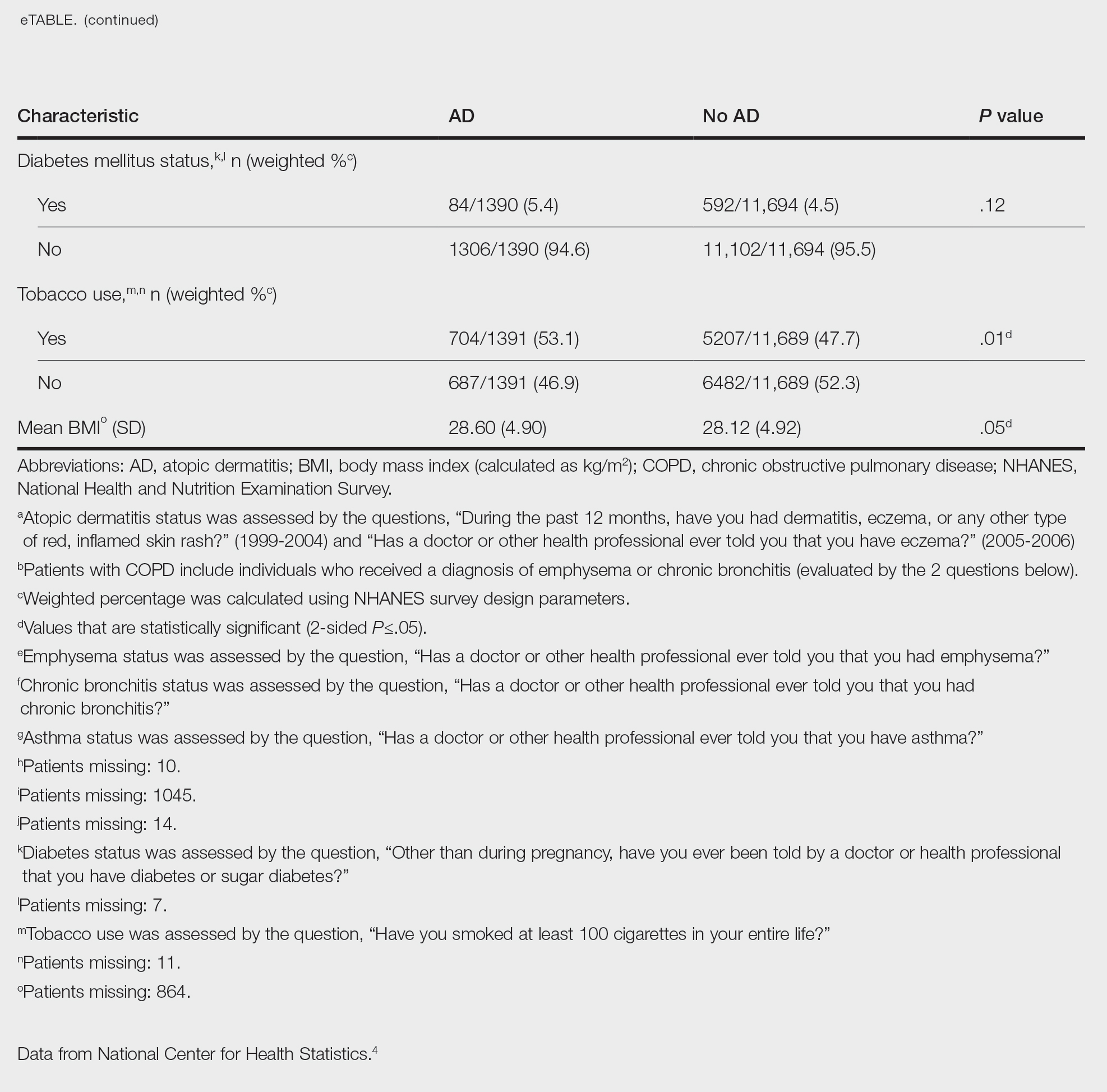

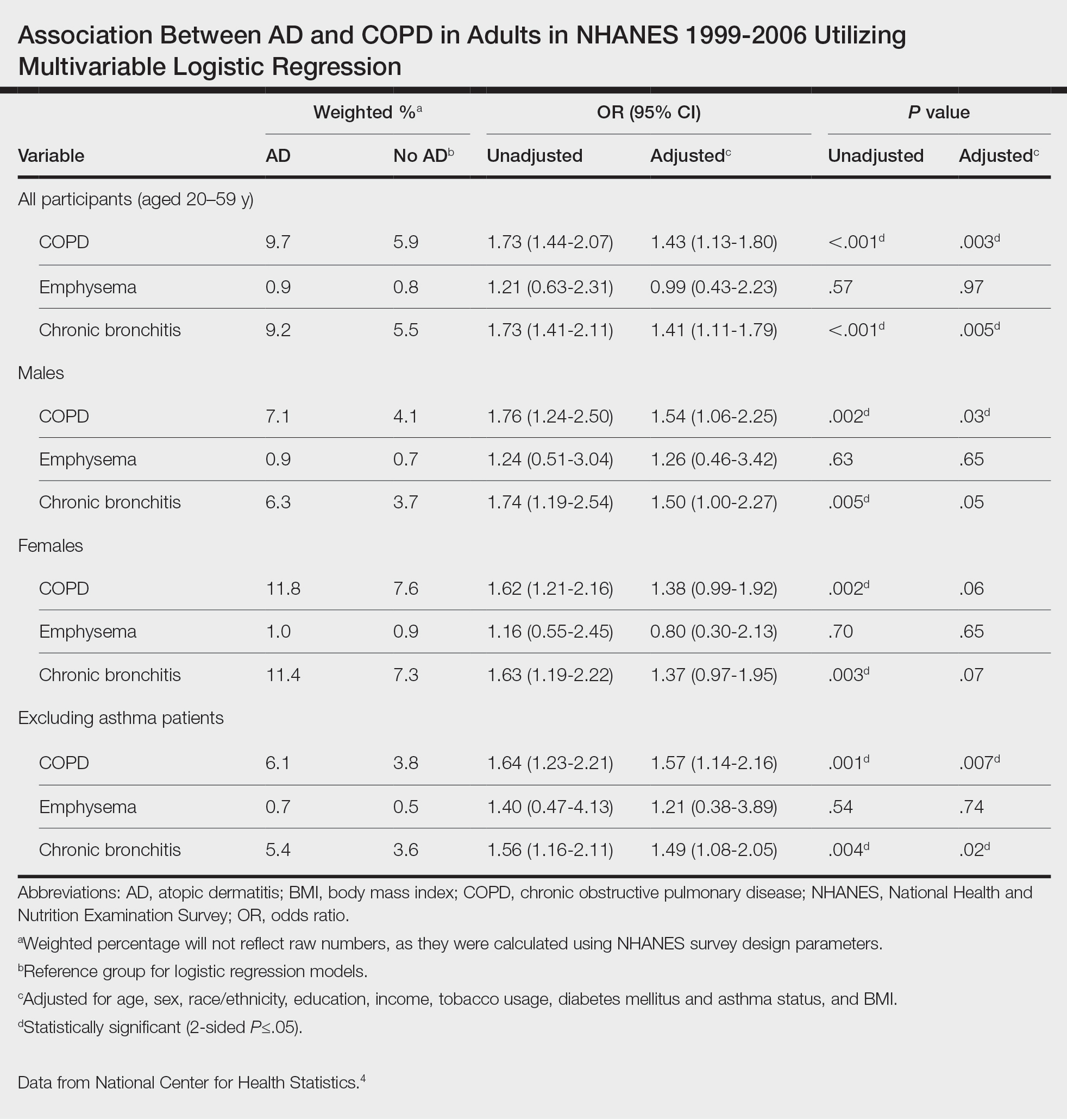

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

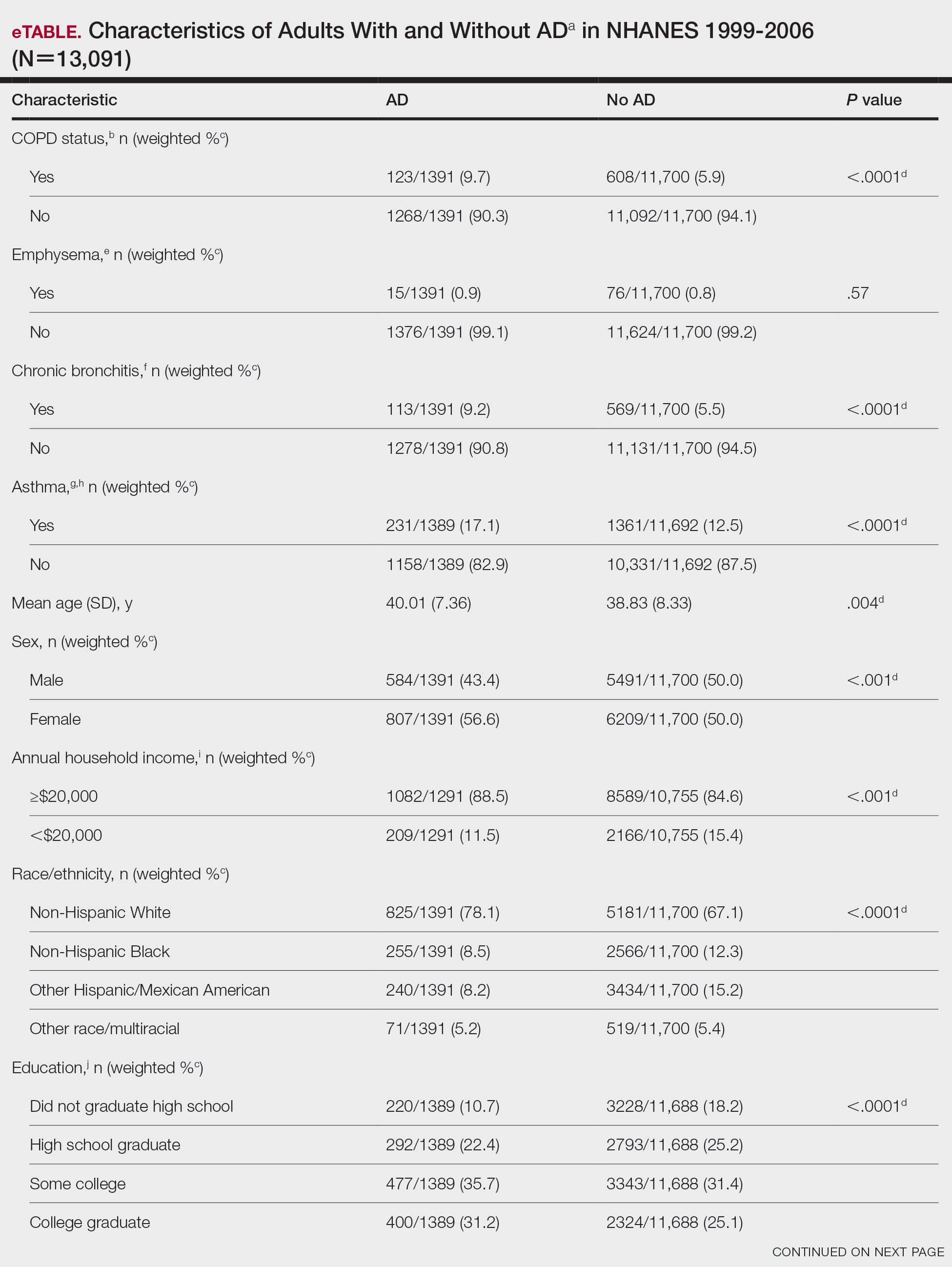

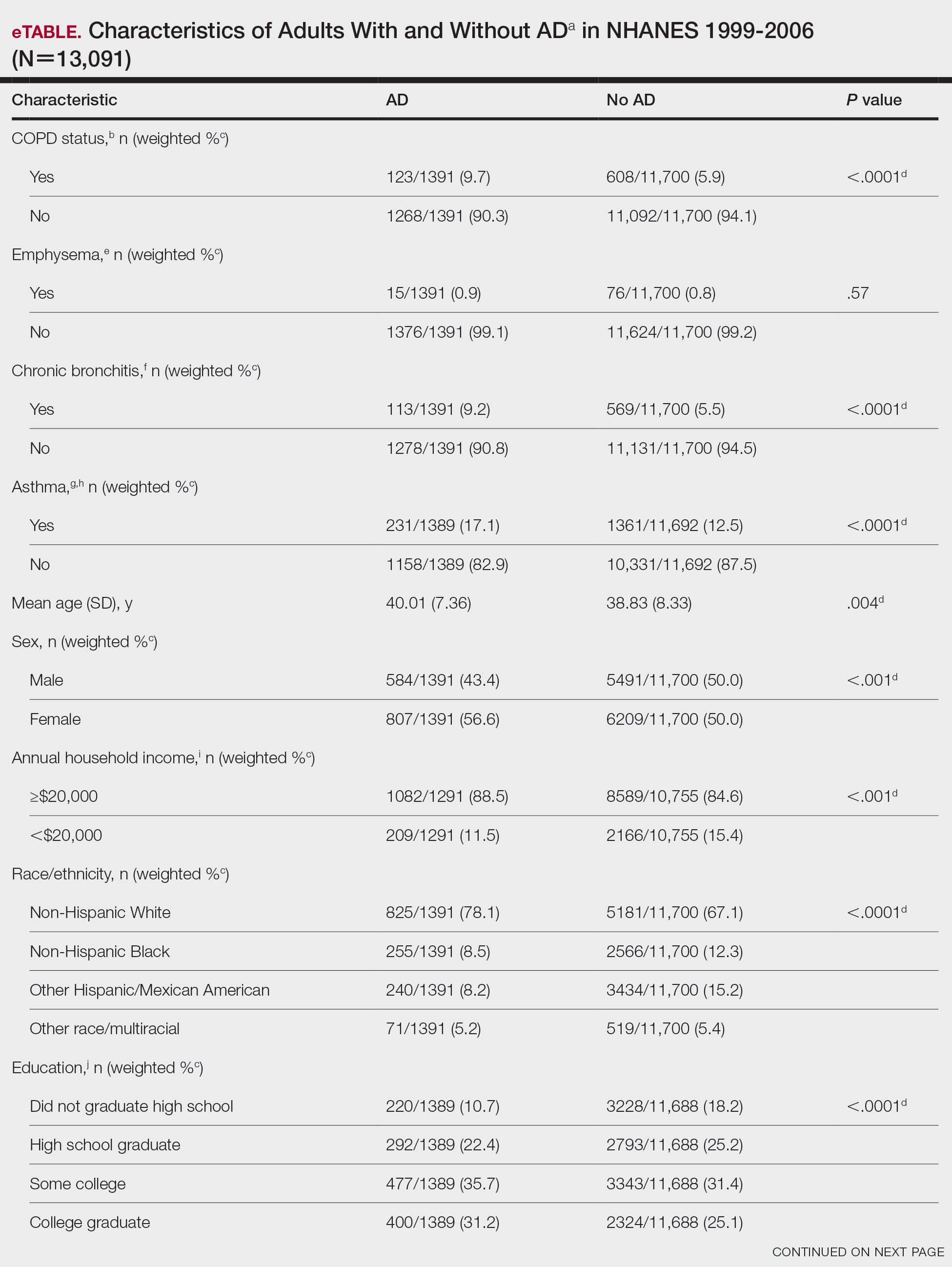

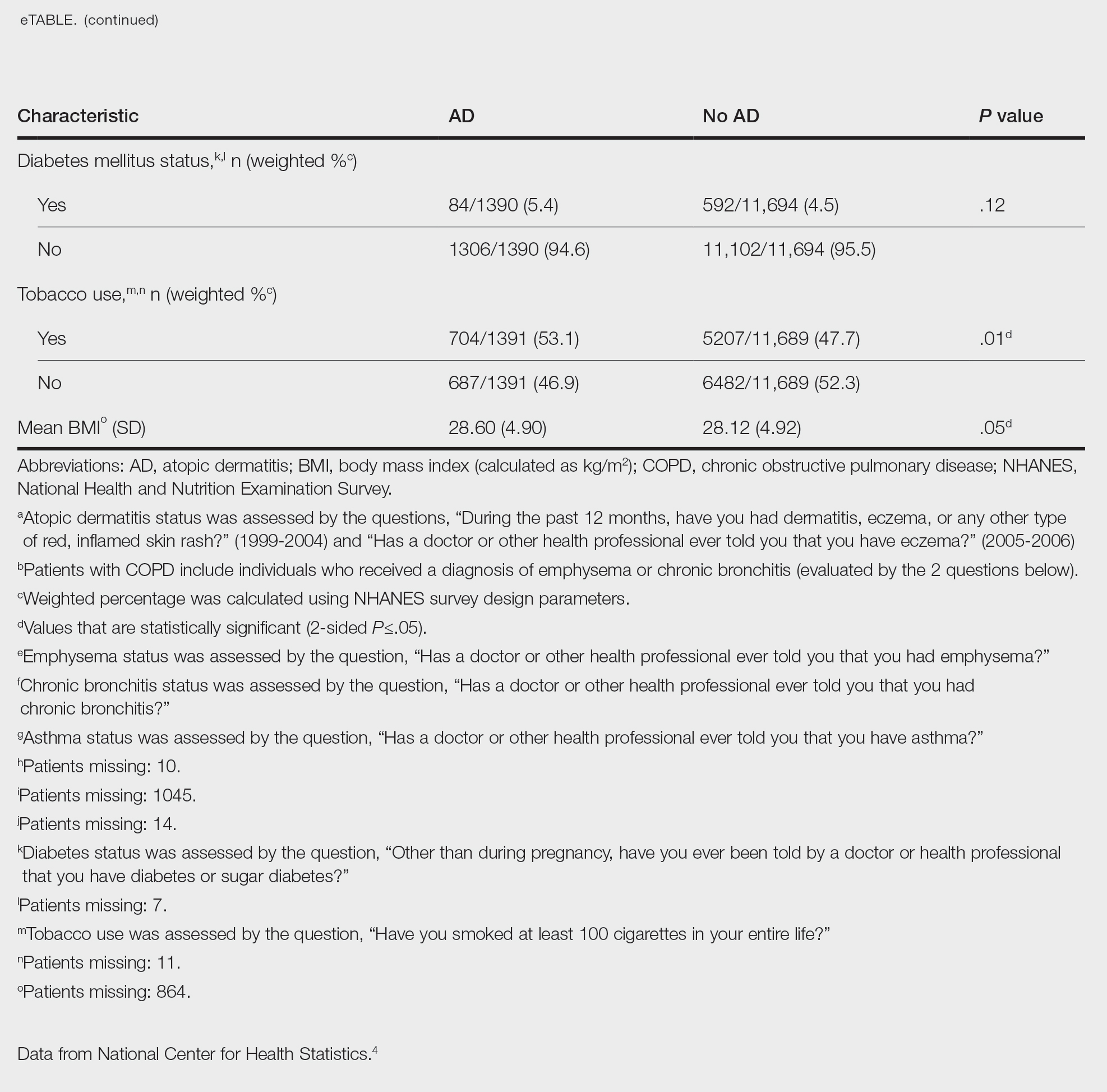

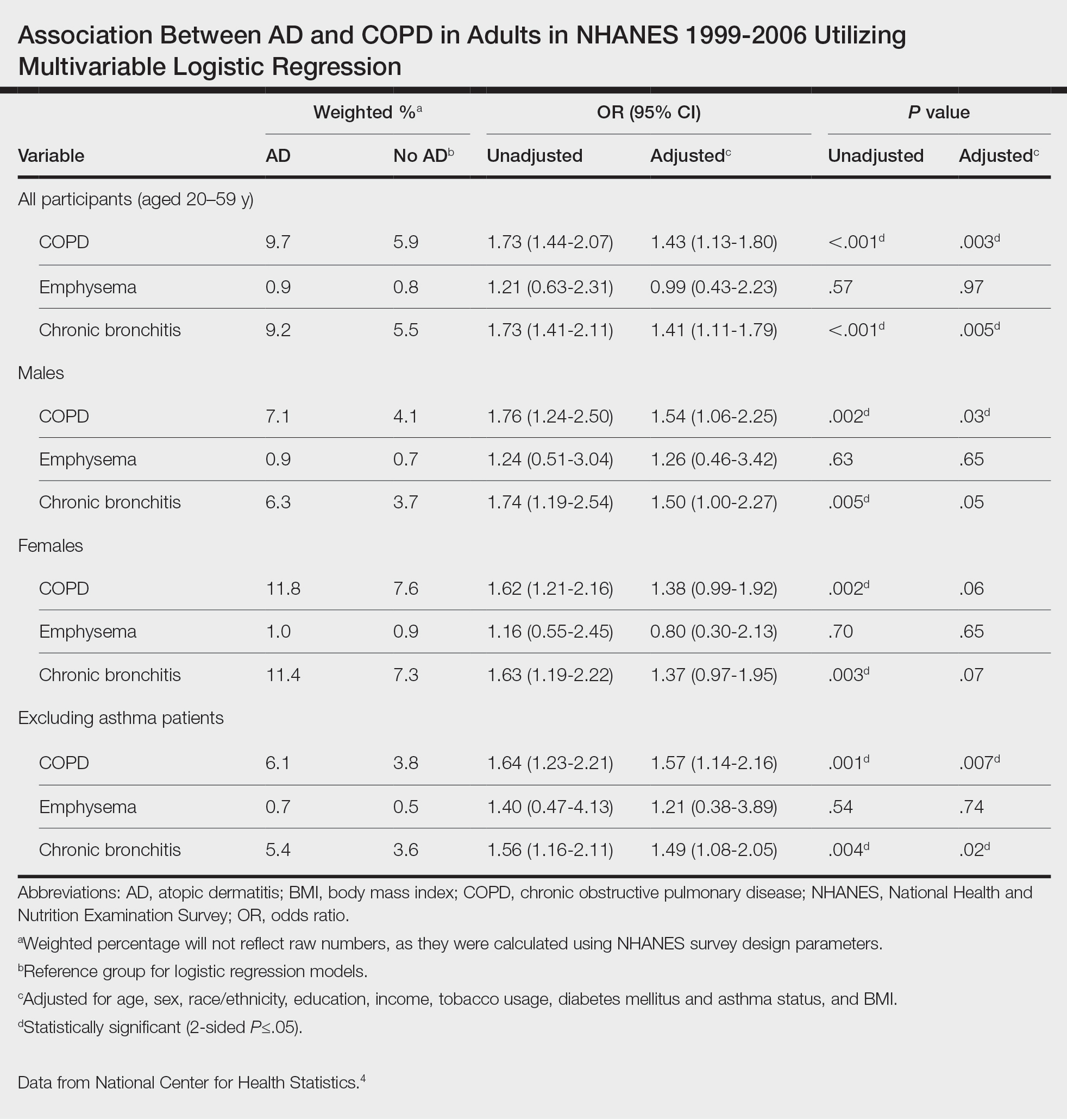

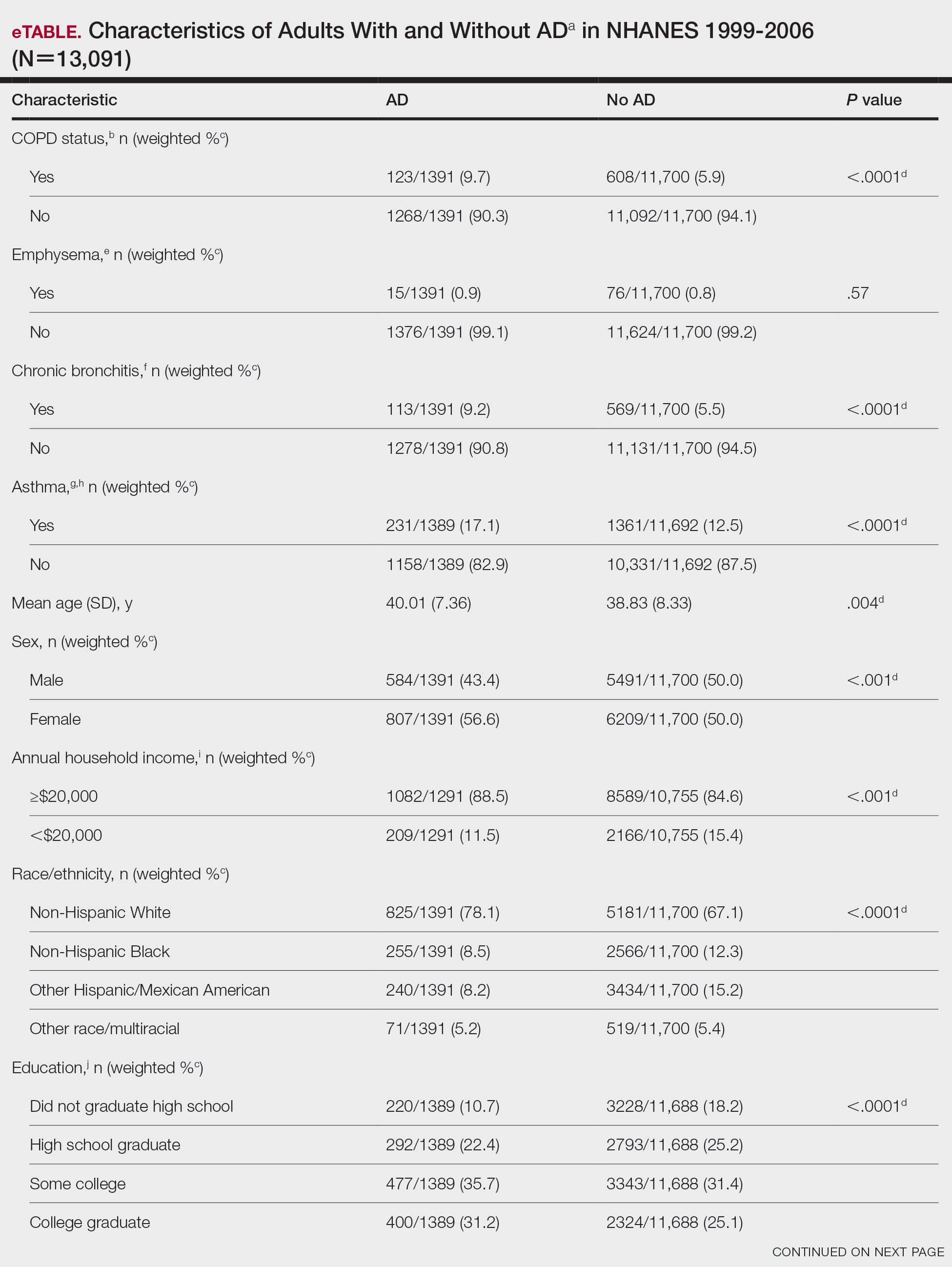

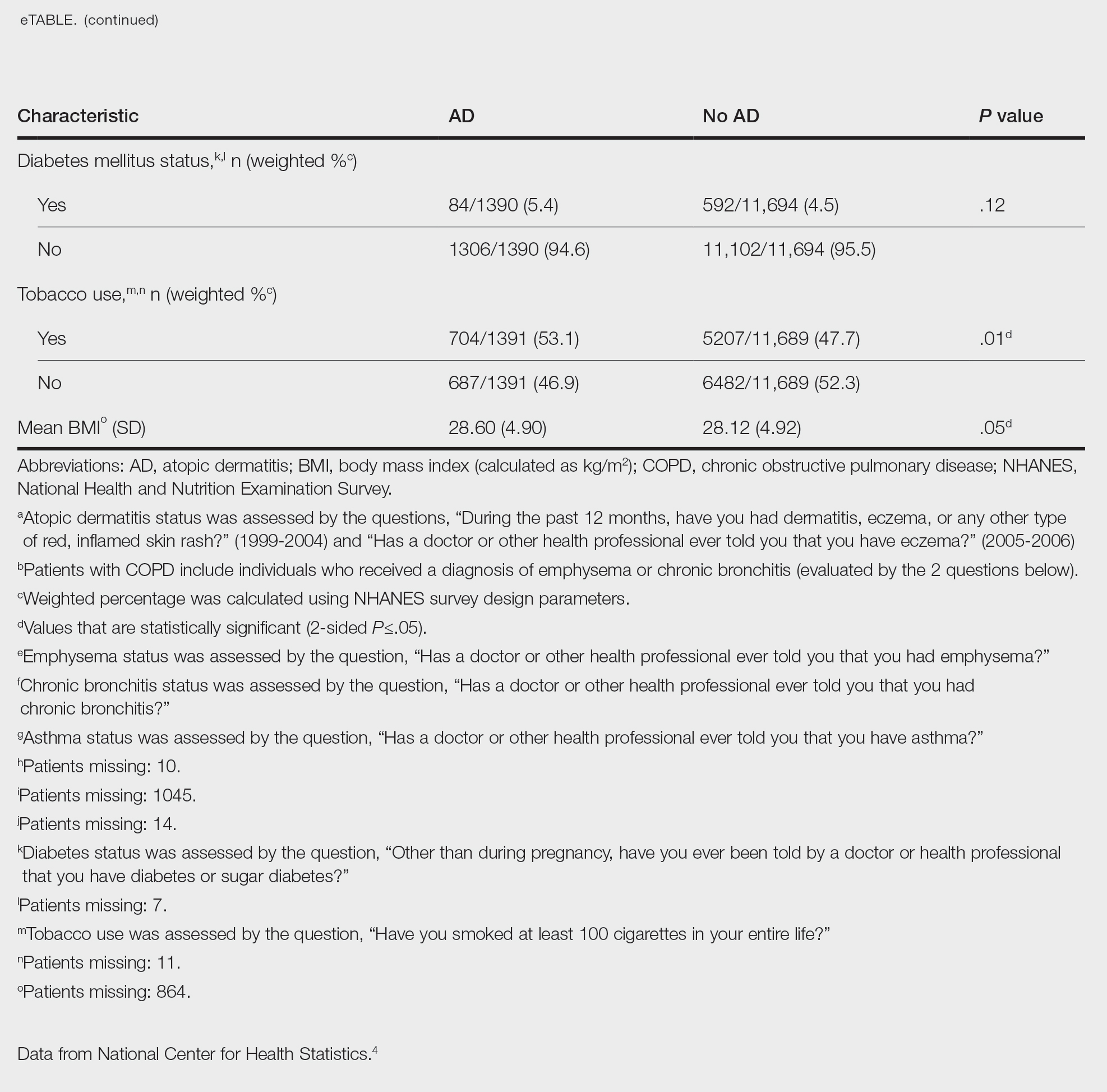

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

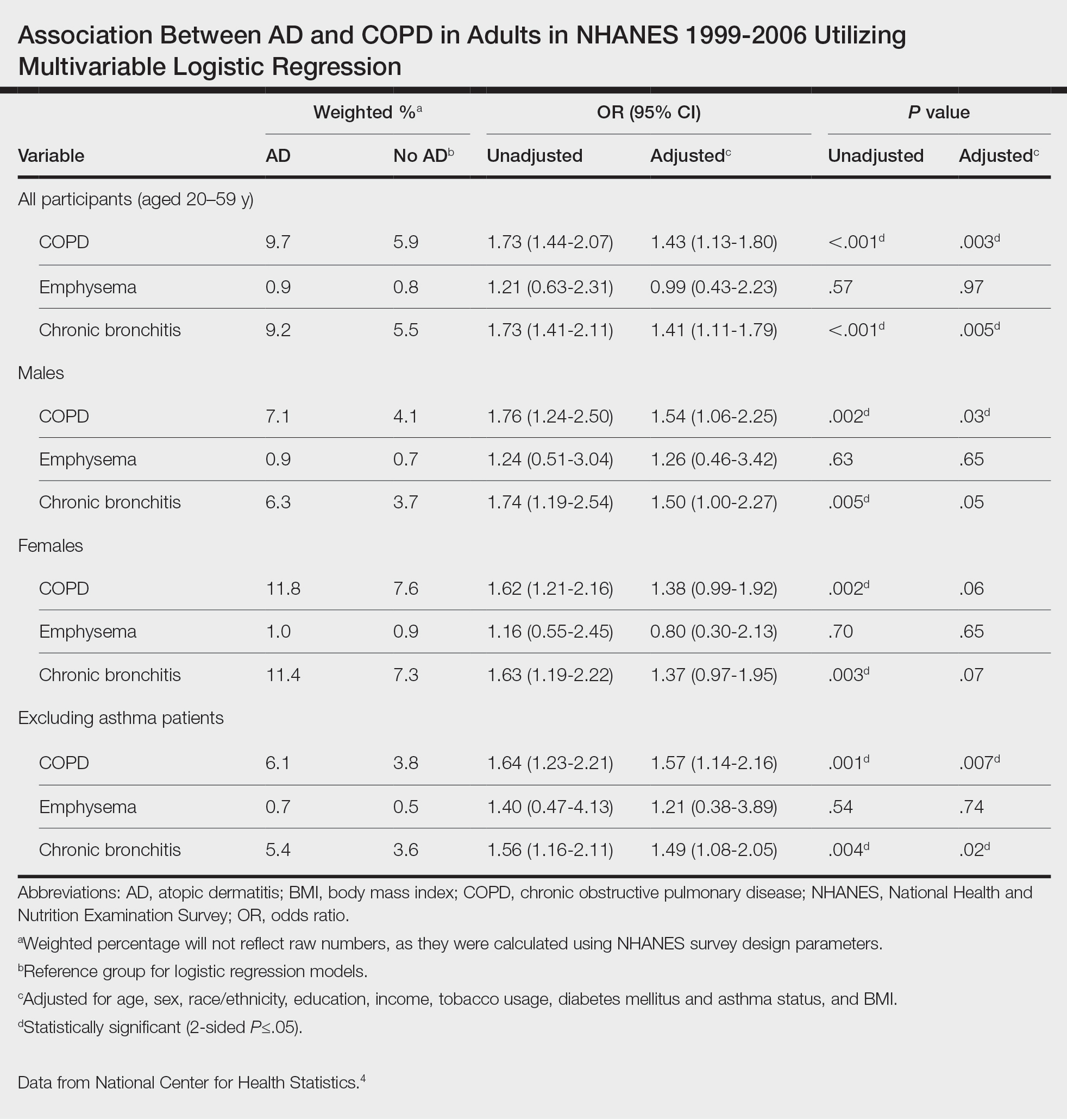

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

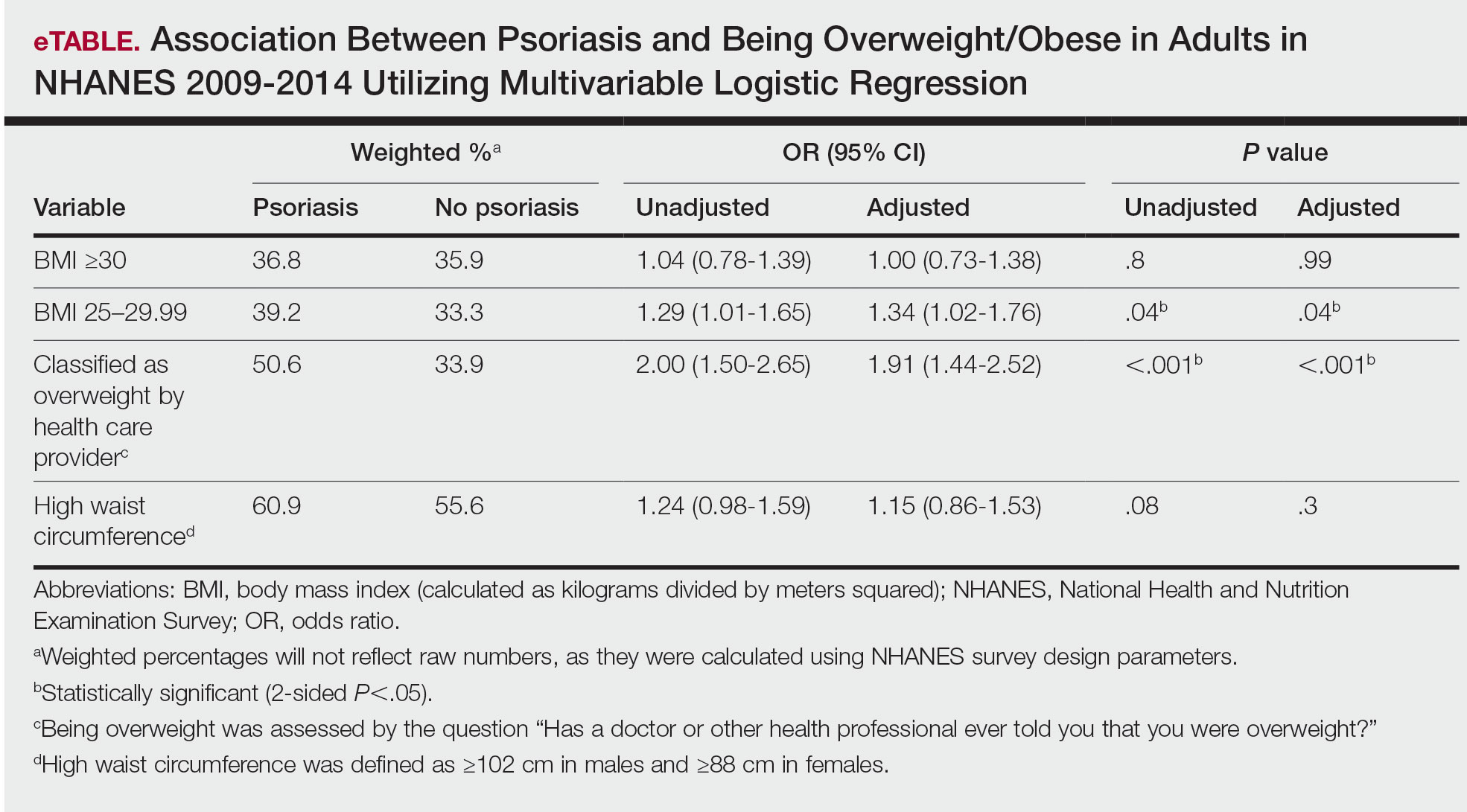

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is an inflammatory skin condition that affects approximately 16.5 million adults in the United States.1 Atopic dermatitis is associated with skin barrier dysfunction and the activation of type 2 inflammatory cytokines. Multiorgan involvement of AD has been demonstrated, as patients with AD are more prone to asthma, allergic rhinitis, and other systemic diseases.2 In 2020, Smirnova et al3 reported a significant association (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.58; 95% CI, 1.30-1.92) between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in a large Swedish population. Currently, there is a lack of research evaluating the association between AD and COPD in a population of US adults. Therefore, we explored the association between AD and COPD (chronic bronchitis or emphysema) in a population of US adults utilizing the 1999-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), as these were the latest data for AD available in NHANES.4

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 1999-2006 NHANES database. Three outcome variables—emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and COPD—and numerous confounding variables for each participant were extracted from the NHANES database. The original cohort consisted of 13,134 participants, and 43 patients were excluded from our analysis owing to the lack of response to survey questions regarding AD and COPD status. The relationship between AD and COPD was evaluated by multivariable logistic regression analyses utilizing Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our logistic regression models, we controlled for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, tobacco usage, diabetes mellitus and asthma status, and body mass index (eTable).

Our study consisted of 13,091 participants. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between AD and COPD (Table). Approximately 12.5% (weighted) of the patients in our analysis had AD. Additionally, 9.7% (weighted) of patients with AD had received a diagnosis of COPD; conversely, 5.9% (weighted) of patients without AD had received a diagnosis of COPD. More patients with AD reported a diagnosis of chronic bronchitis (9.2%) rather than emphysema (0.9%). Our analysis revealed a significant association between AD and COPD among adults aged 20 to 59 years (AOR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.13-1.80; P=.003) after controlling for potential confounding variables. Subsequently, we performed subgroup analyses, including exclusion of patients with an asthma diagnosis, to further explore the association between AD and COPD. After excluding participants with asthma, there was still a significant association between AD and COPD (AOR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.14-2.16; P=.007). Moreover, the odds of receiving a COPD diagnosis were significantly higher among male patients with AD (AOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.06-2.25; P=.03).

Our results support the association between AD and COPD, more specifically chronic bronchitis. This finding may be due to similar pathogenic mechanisms in both conditions, including overlapping cytokine production and immune pathways.5 Additionally, Harazin et al6 discussed the role of a novel gene, collagen 29A1 (COL29A1), in the pathogenesis of AD, COPD, and asthma. Variations in this gene may predispose patients to not only atopic diseases but also COPD.6

Limitations of our study include self-reported diagnoses and lack of patients older than 59 years. Self-reported diagnoses could have resulted in some misclassification of COPD, as some individuals may have reported a diagnosis of COPD rather than their true diagnosis of asthma. We mitigated this limitation by constructing a subpopulation model with exclusion of individuals with asthma. Further studies with spirometry-diagnosed COPD are needed to explore this relationship and the potential contributory pathophysiologic mechanisms. Understanding this association may increase awareness of potential comorbidities and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in America Study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:583-590. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028

- Darlenski R, Kazandjieva J, Hristakieva E, et al. Atopic dermatitis as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:409-413. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.007

- Smirnova J, Montgomery S, Lindberg M, et al. Associations of self-reported atopic dermatitis with comorbid conditions in adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Dermatol. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12895-020-00117-8

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Kawayama T, Okamoto M, Imaoka H, et al. Interleukin-18 in pulmonary inflammatory diseases. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:443-449. doi:10.1089/jir.2012.0029

- Harazin M, Parwez Q, Petrasch-Parwez E, et al. Variation in the COL29A1 gene in German patients with atopic dermatitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Dermatol. 2010;37:740-742. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00923.x

Practice Points

- Various comorbidities are associated with atopic dermatitis (AD). Currently, research exploring the association between AD and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is limited.

- Understanding the systemic diseases associated with inflammatory skin diseases can assist with adequate patient management.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Atopic Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

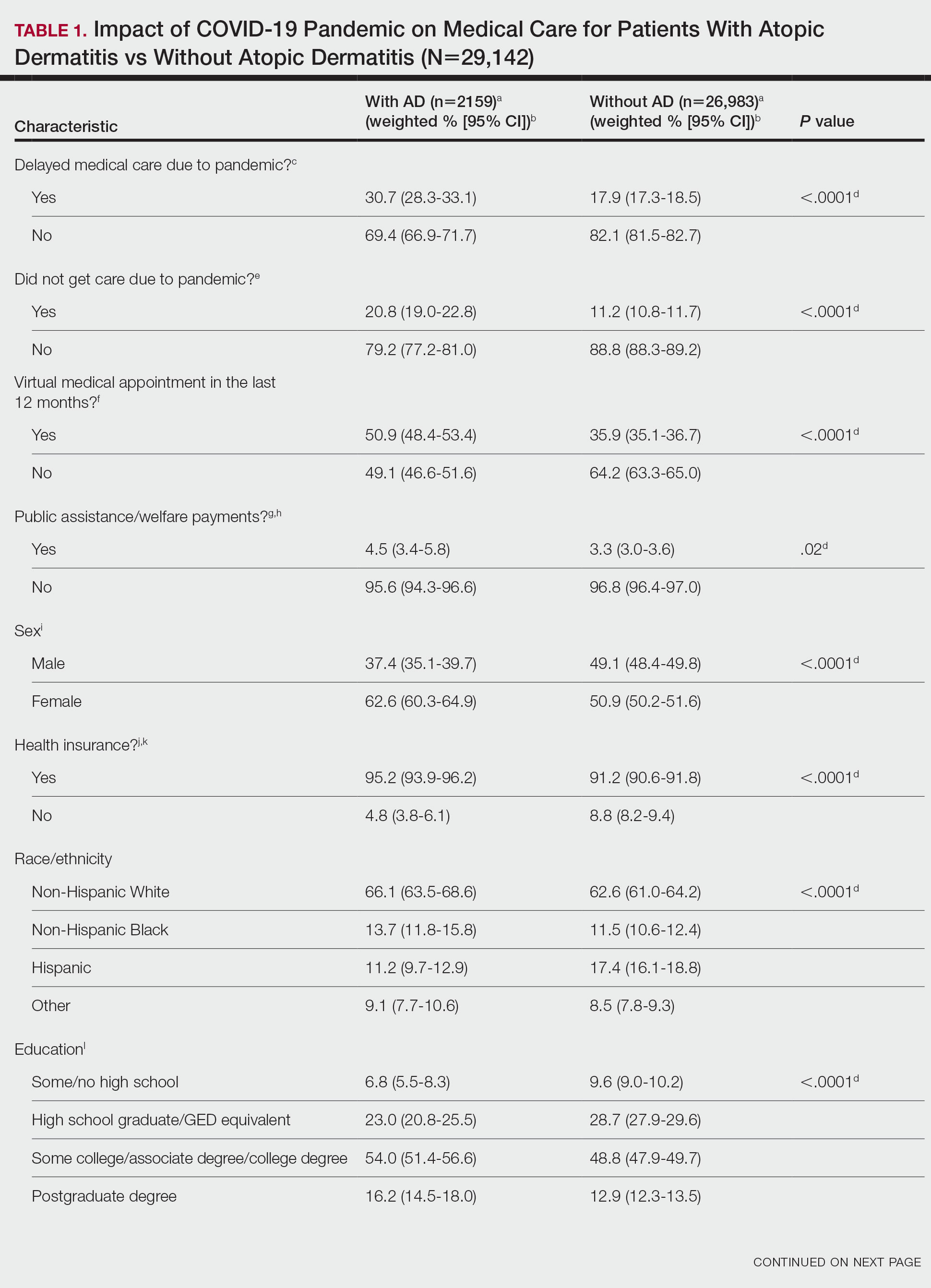

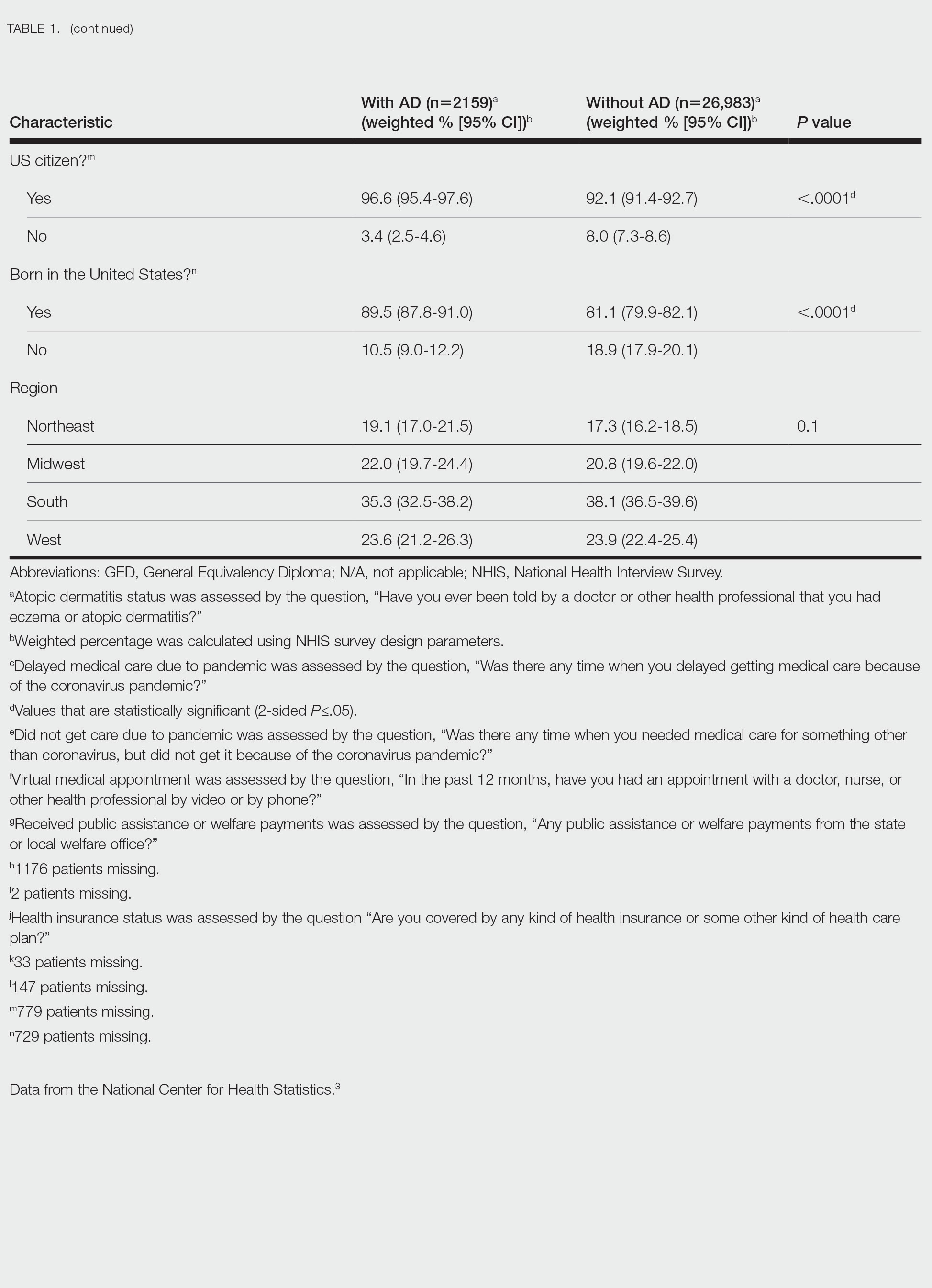

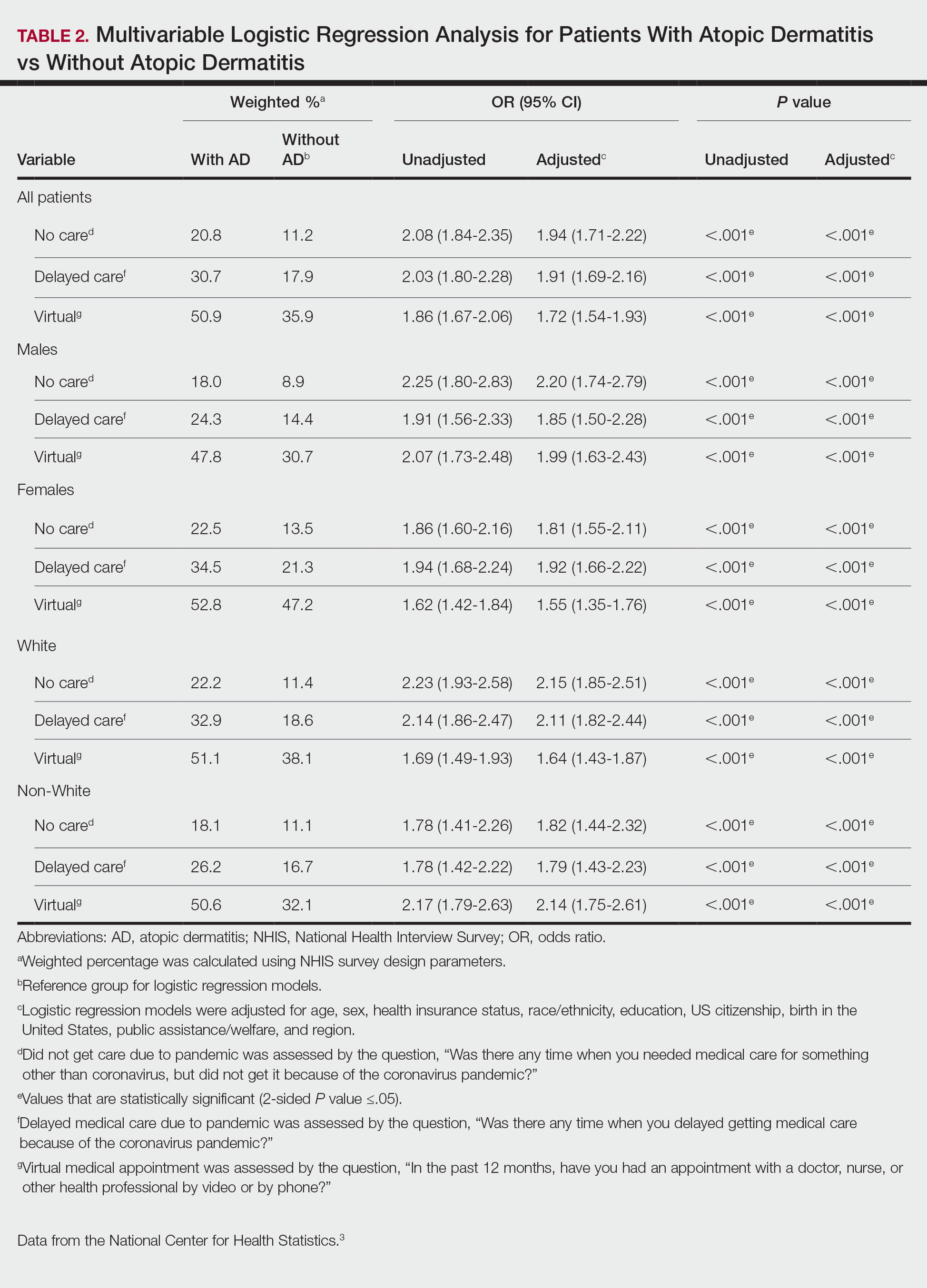

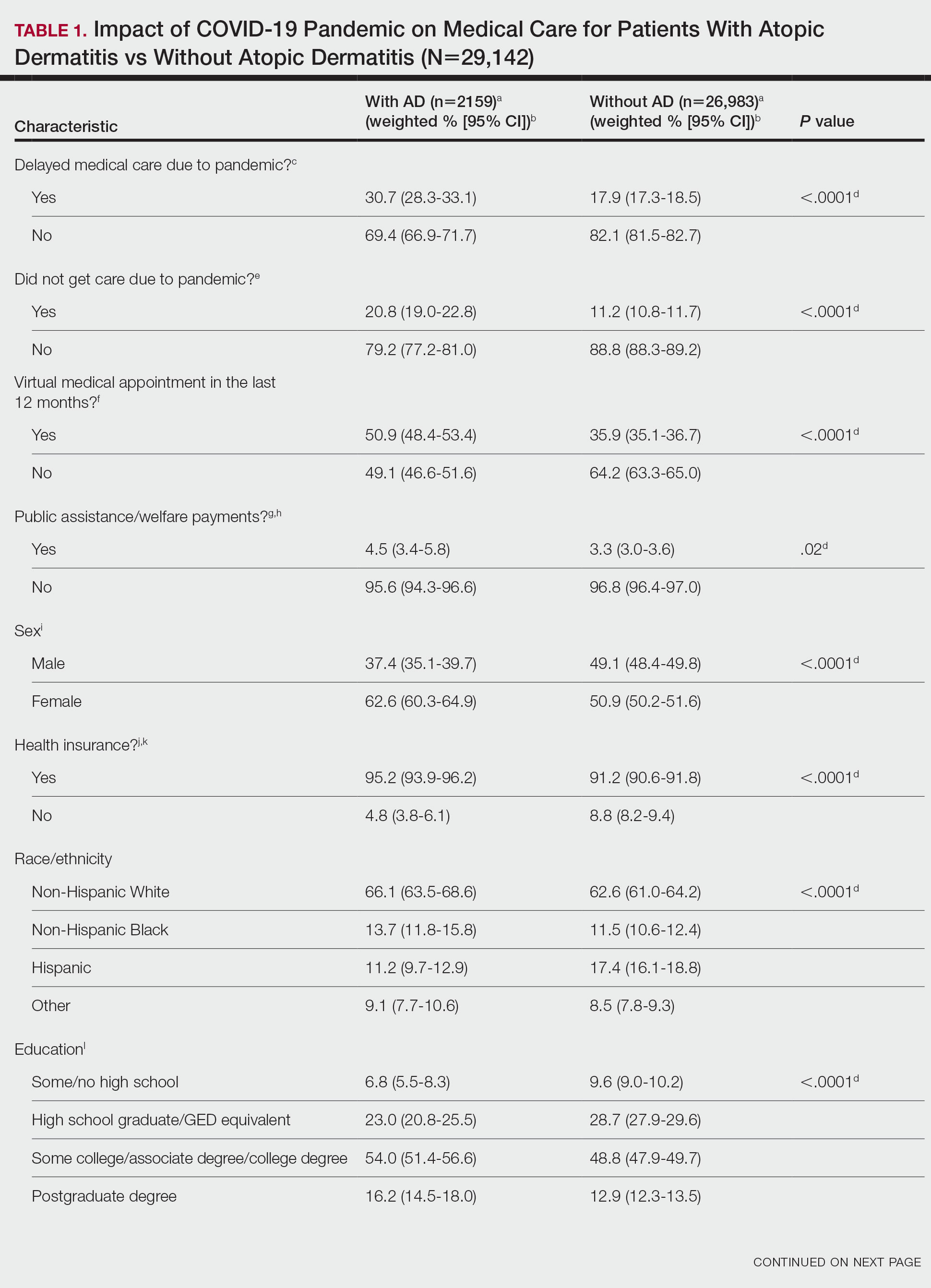

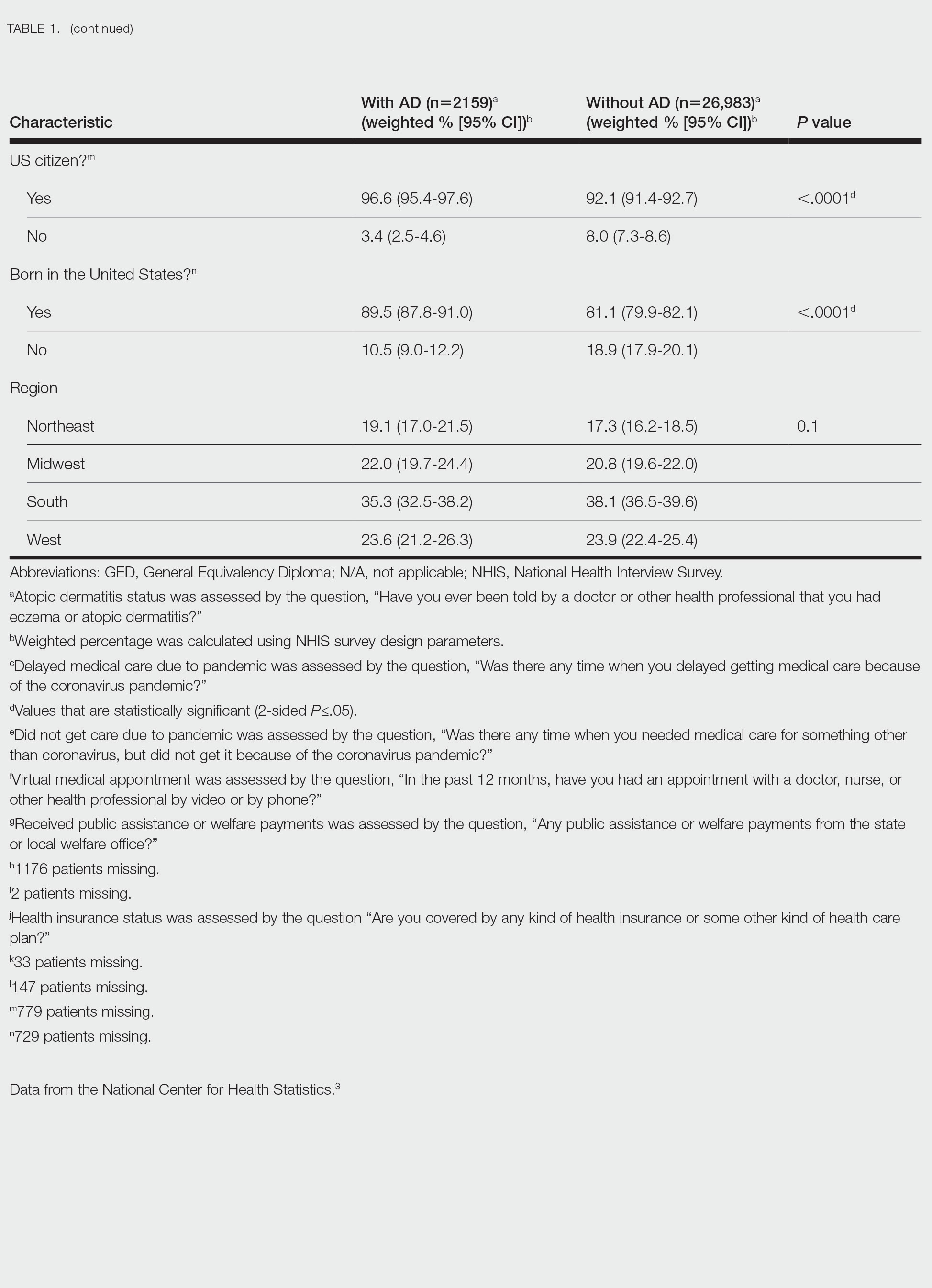

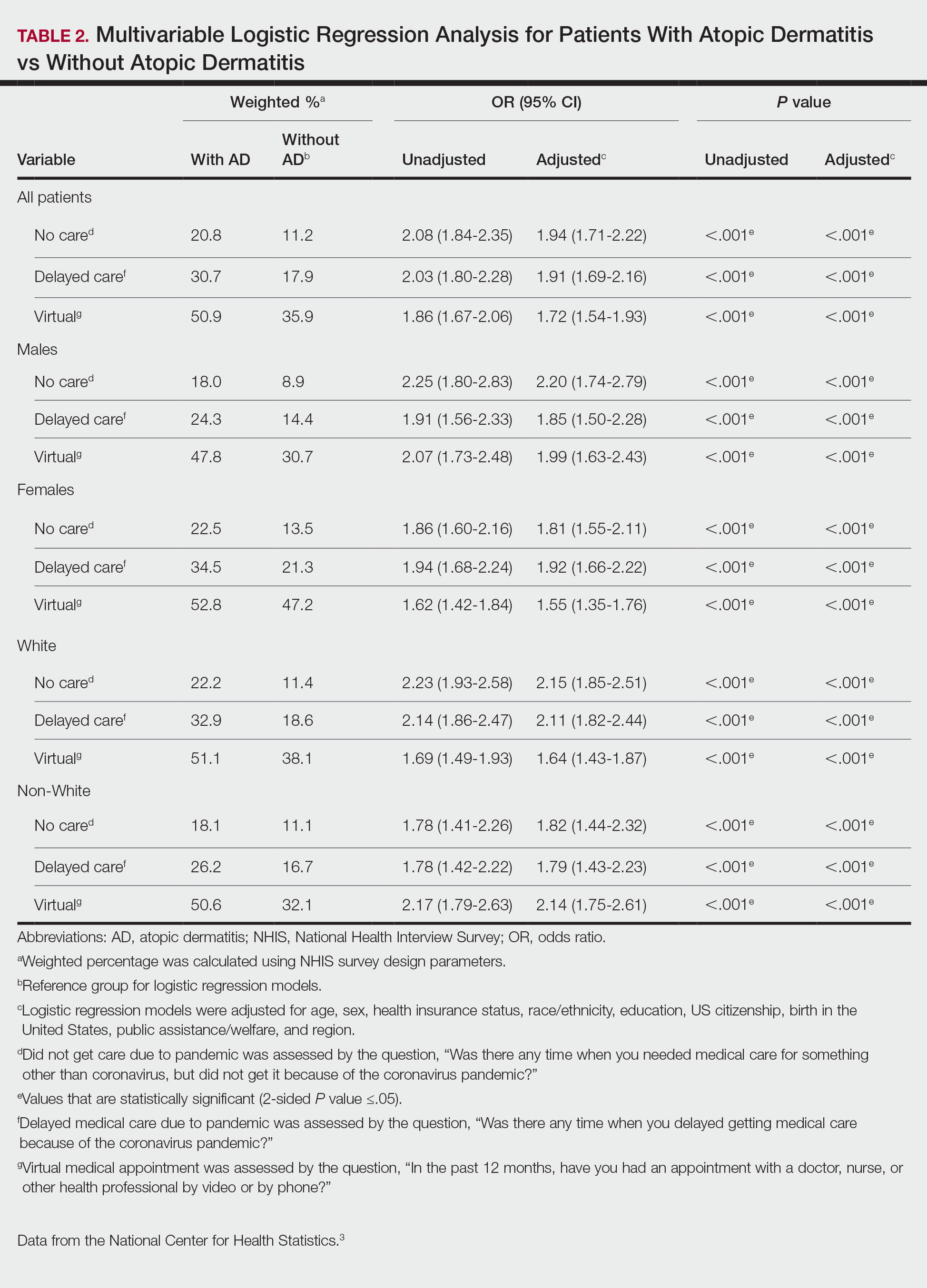

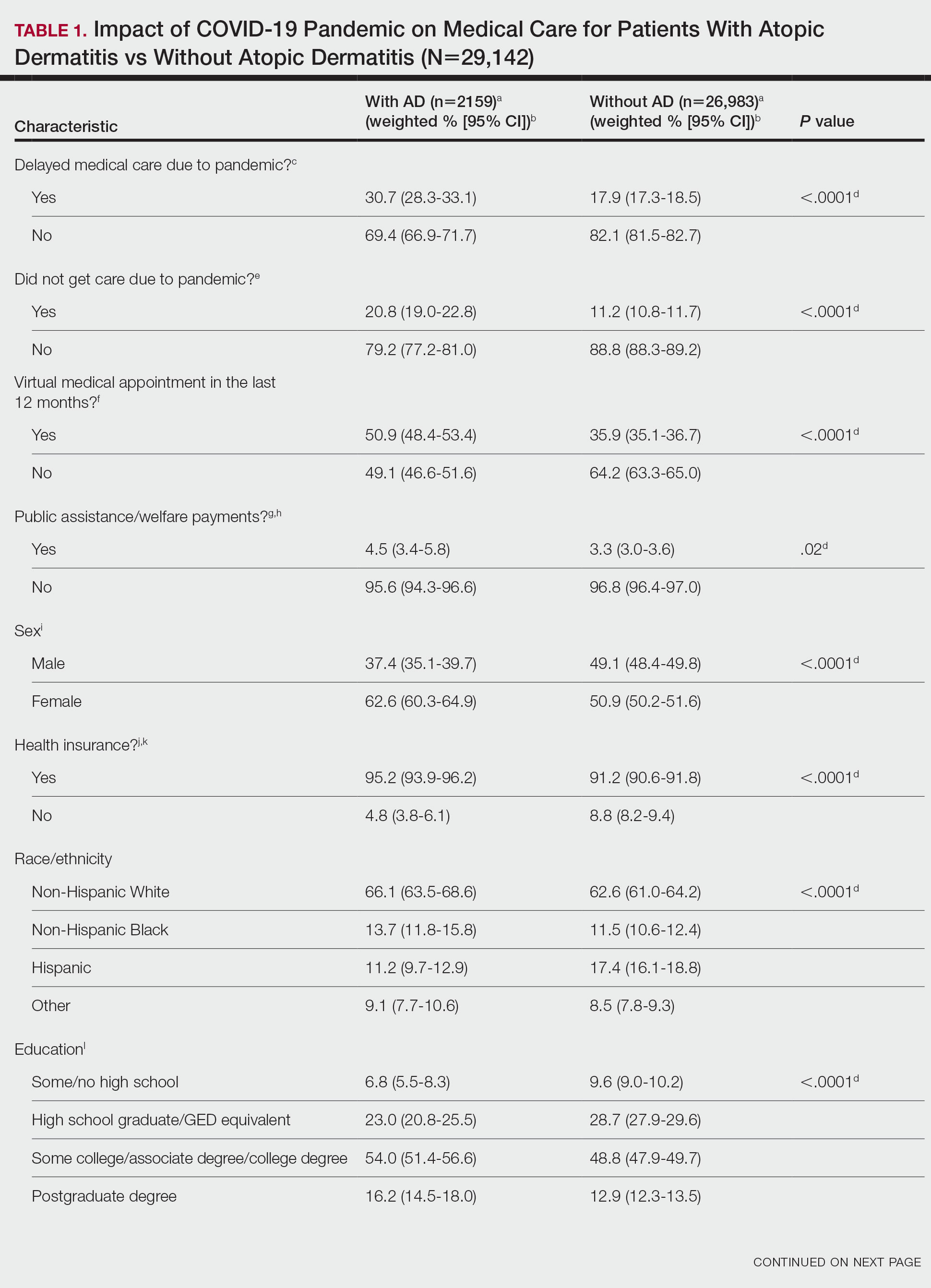

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

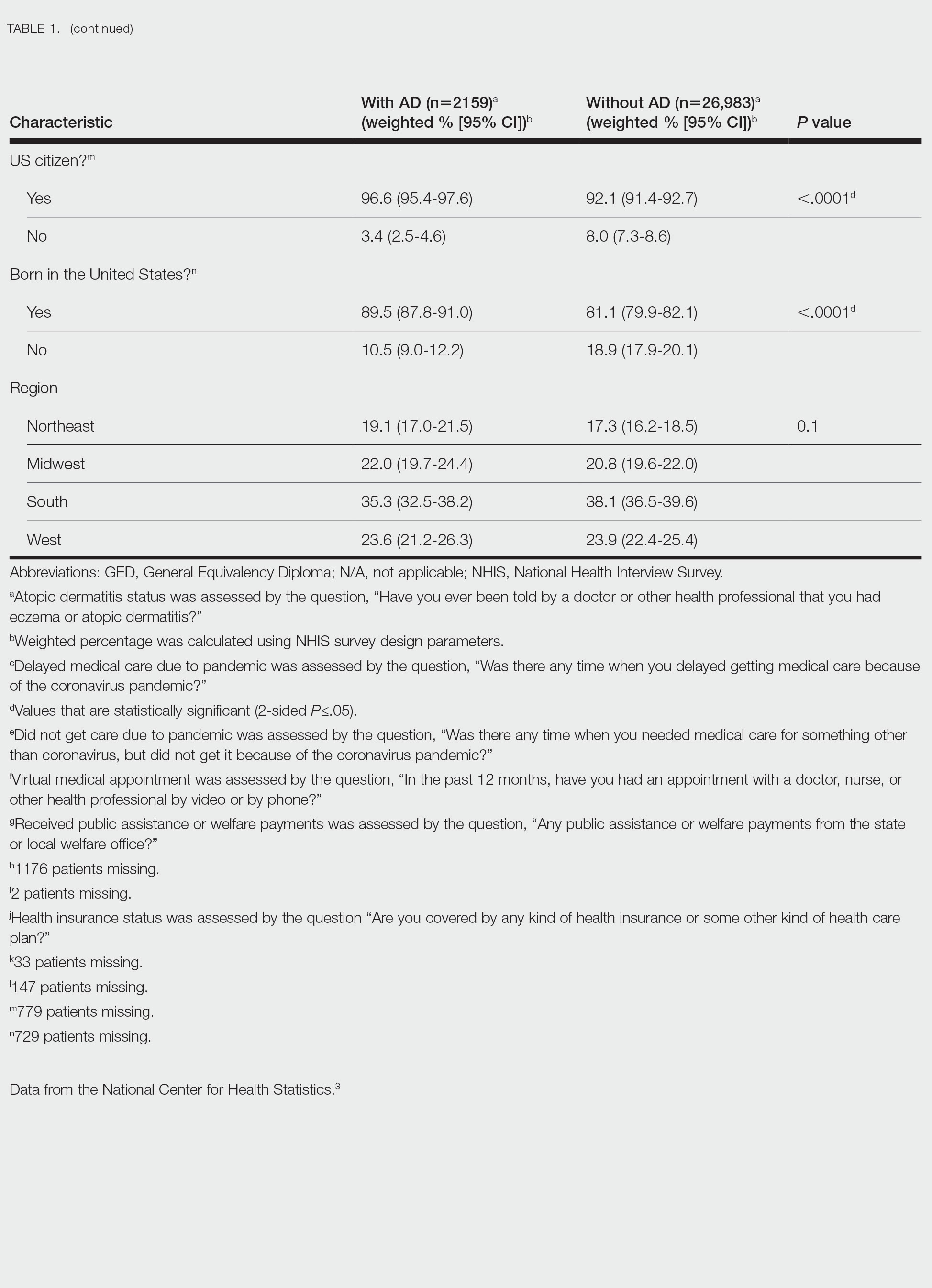

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

Practice Points

- The landscape of dermatology has seen major changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as many patients now utilize telemedicine to receive care.

- Understanding accessibility to in-person care for patients with atopic dermatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic can assist with the development of methods to enhance management.

Financial Insecurity Among US Adults With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

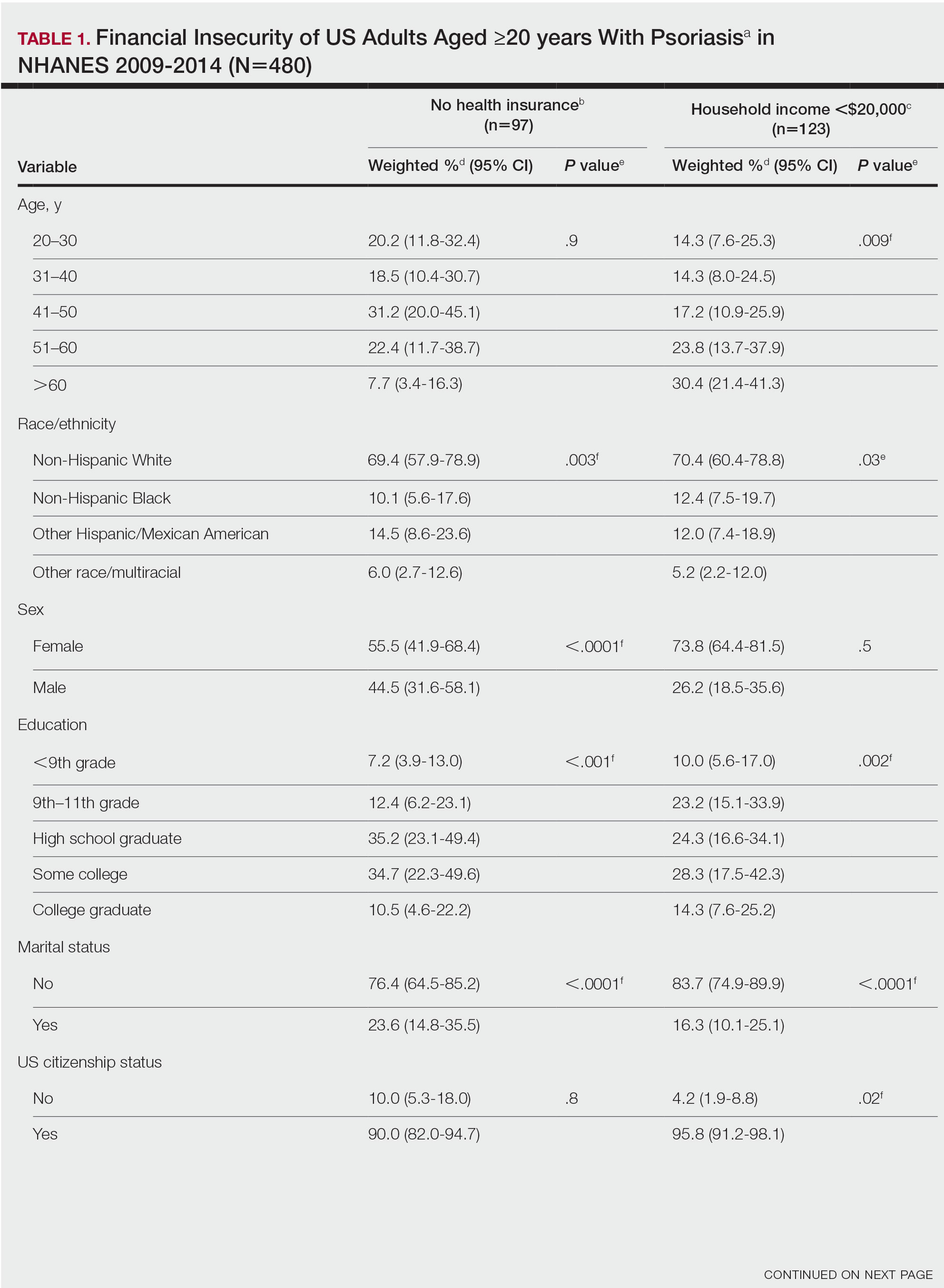

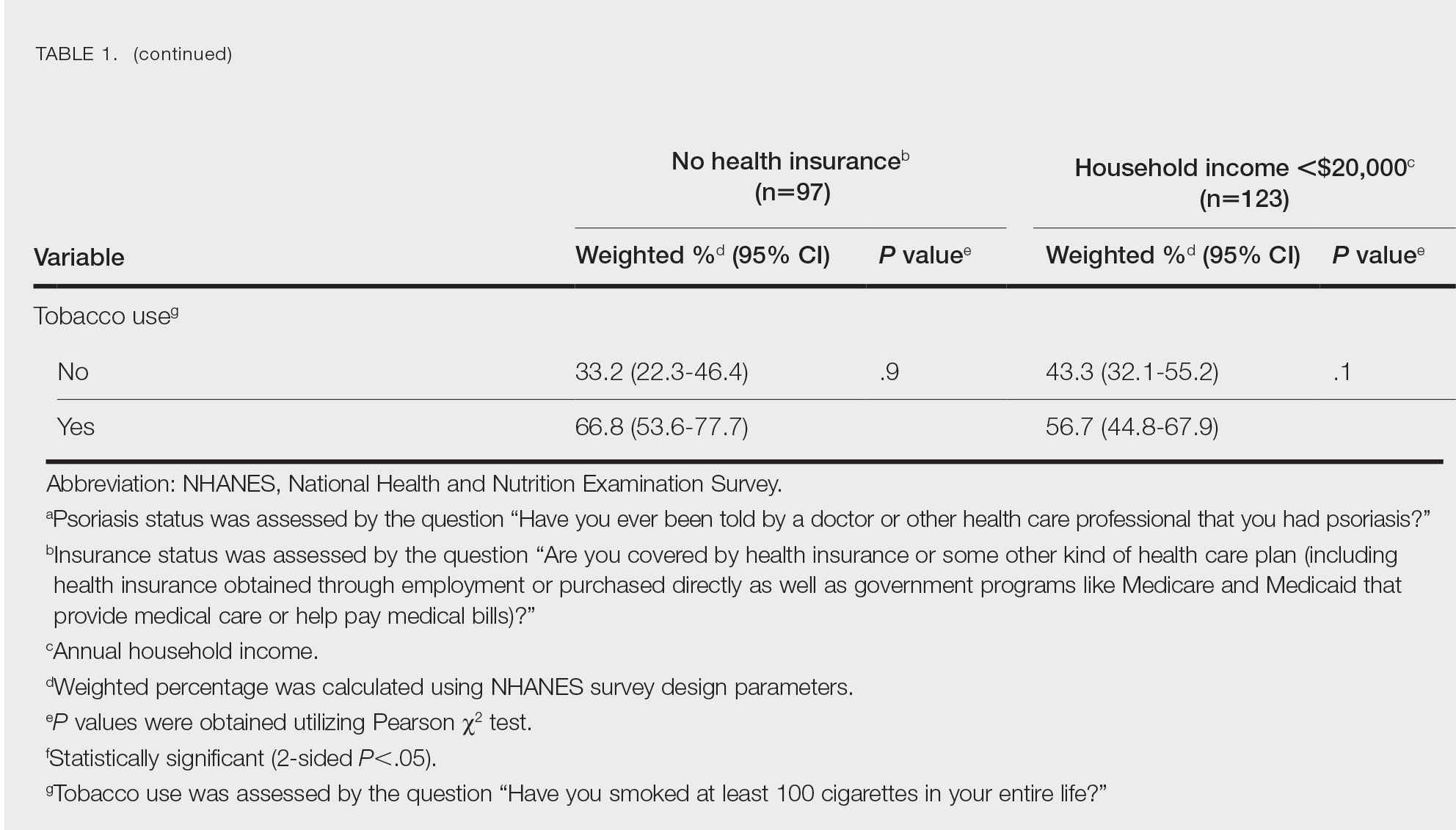

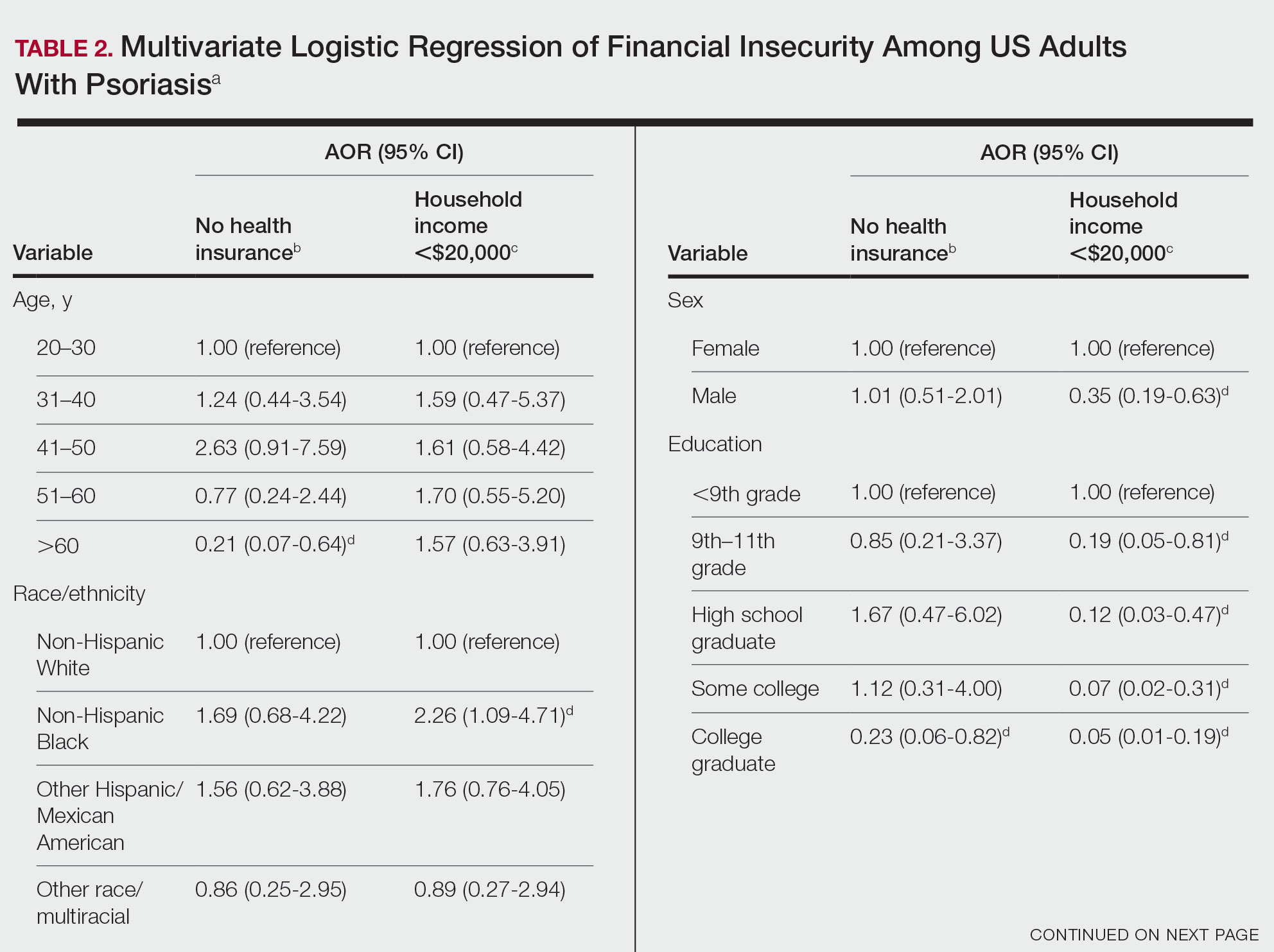

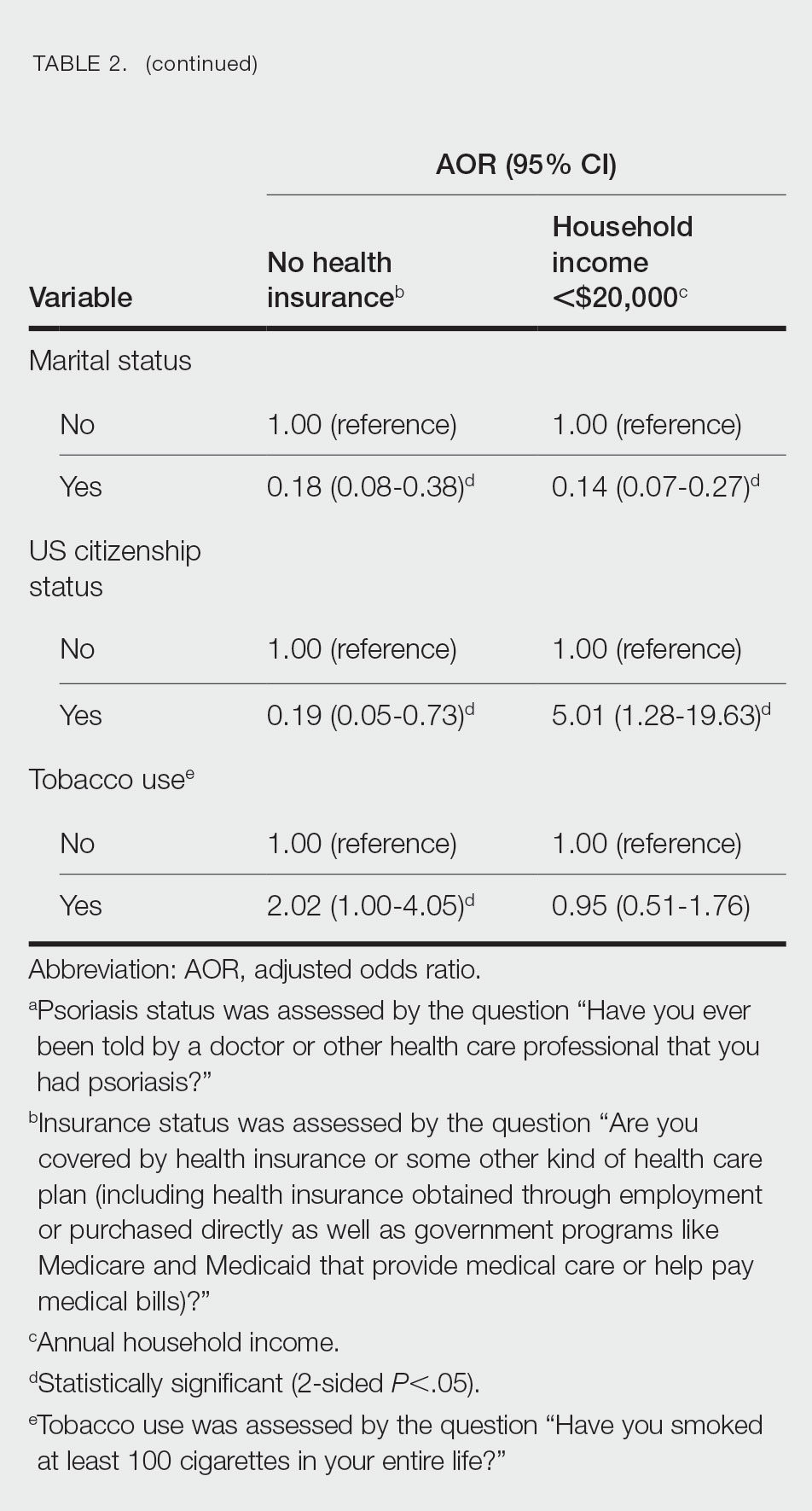

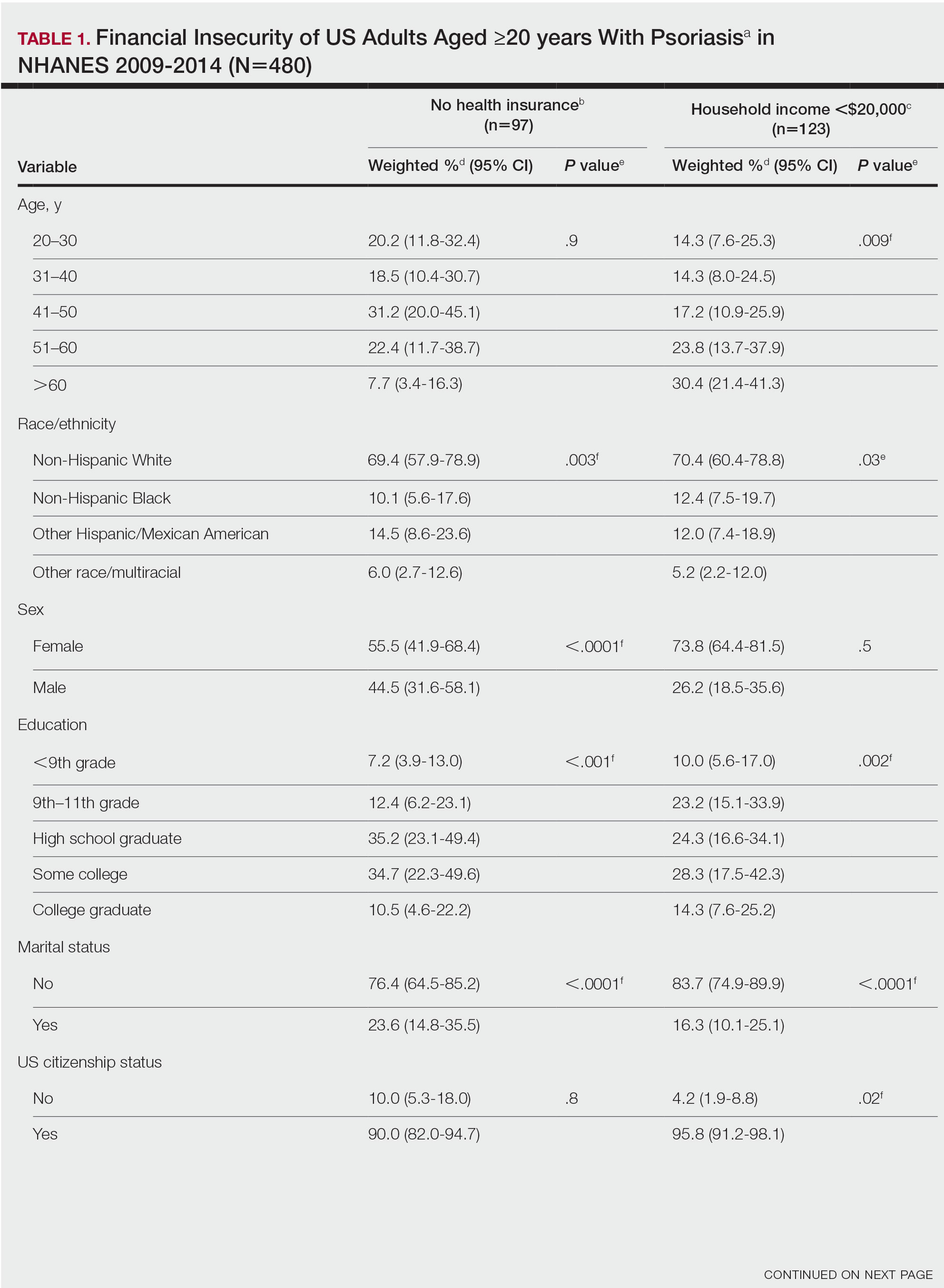

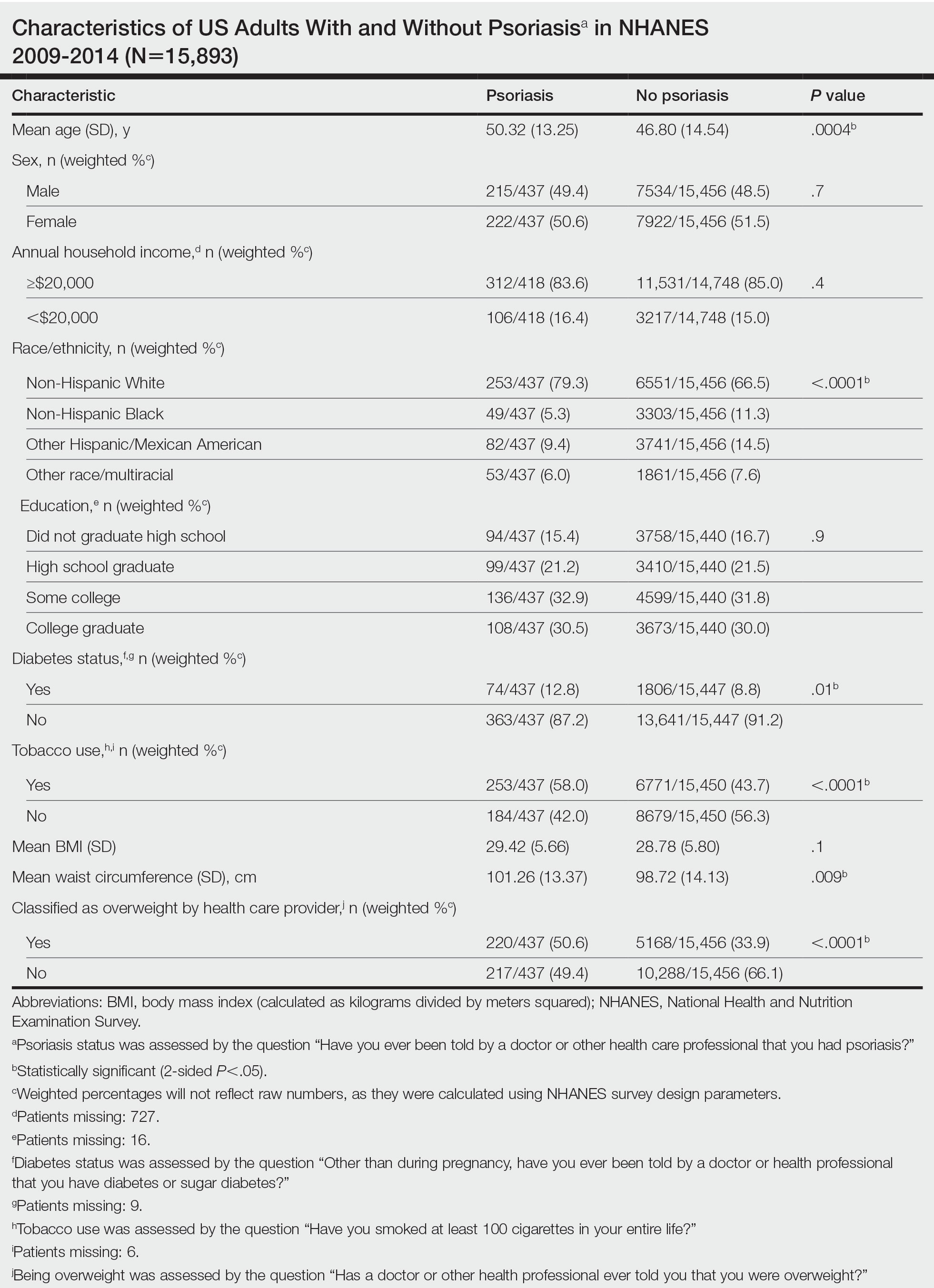

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

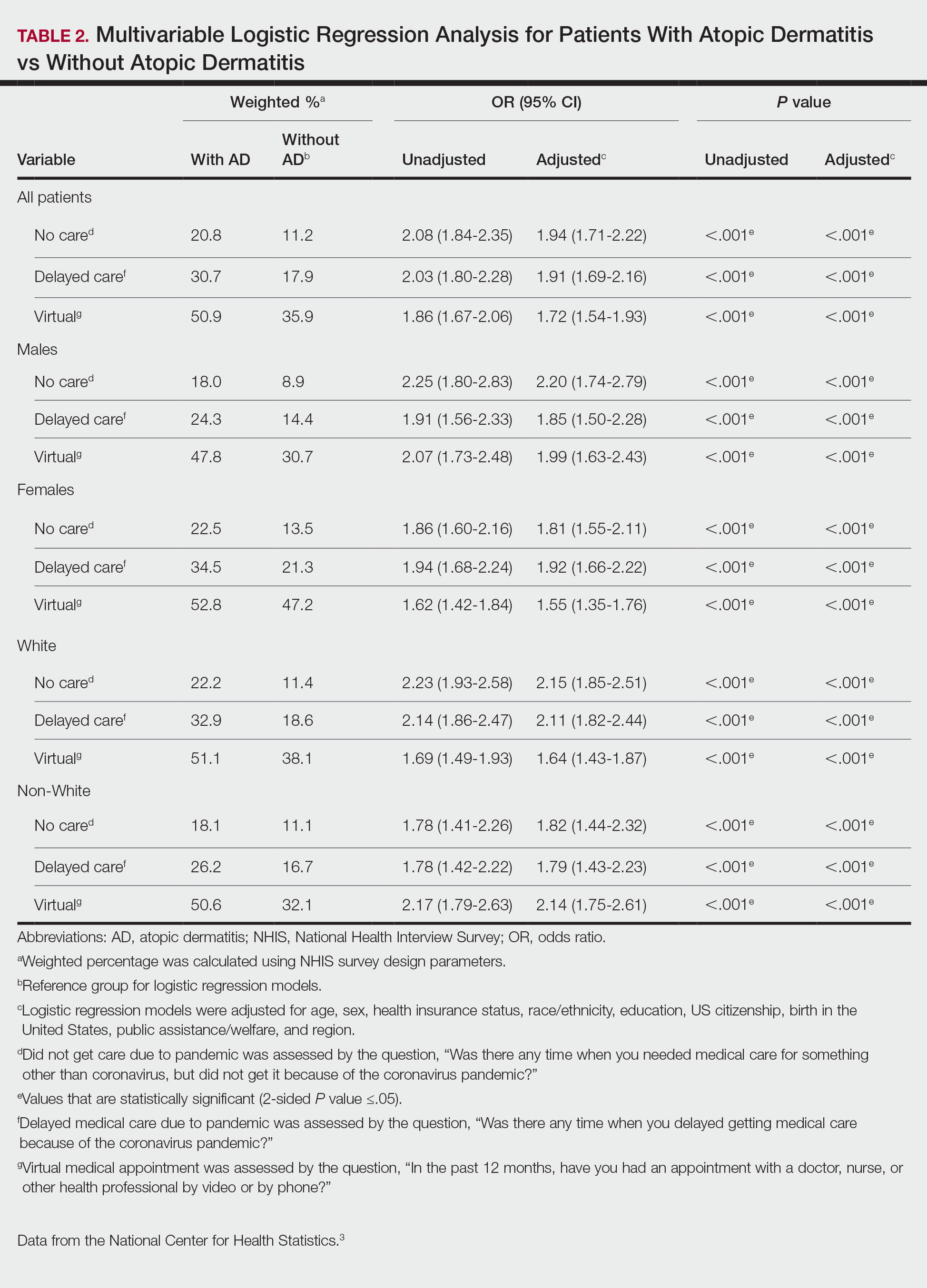

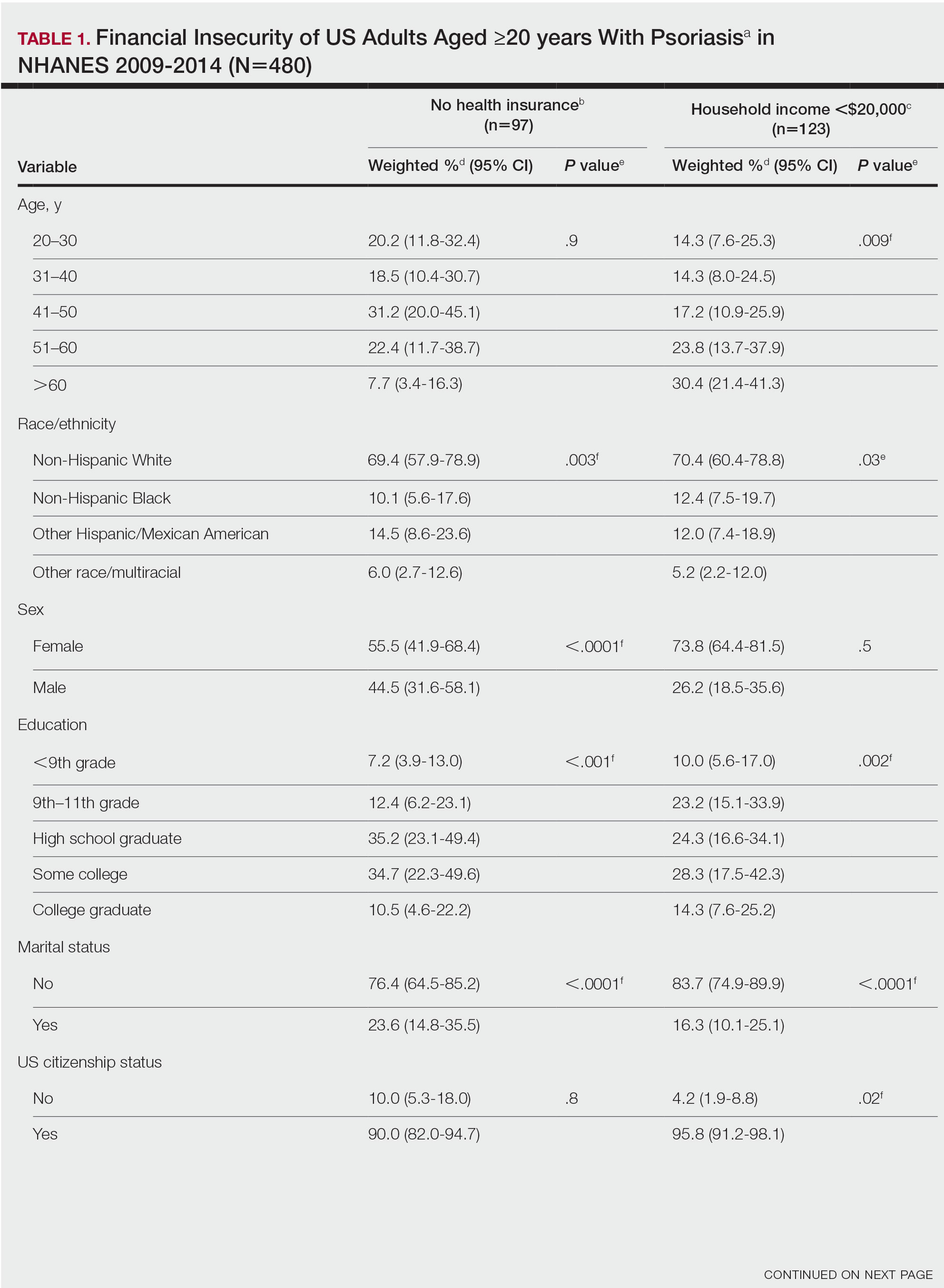

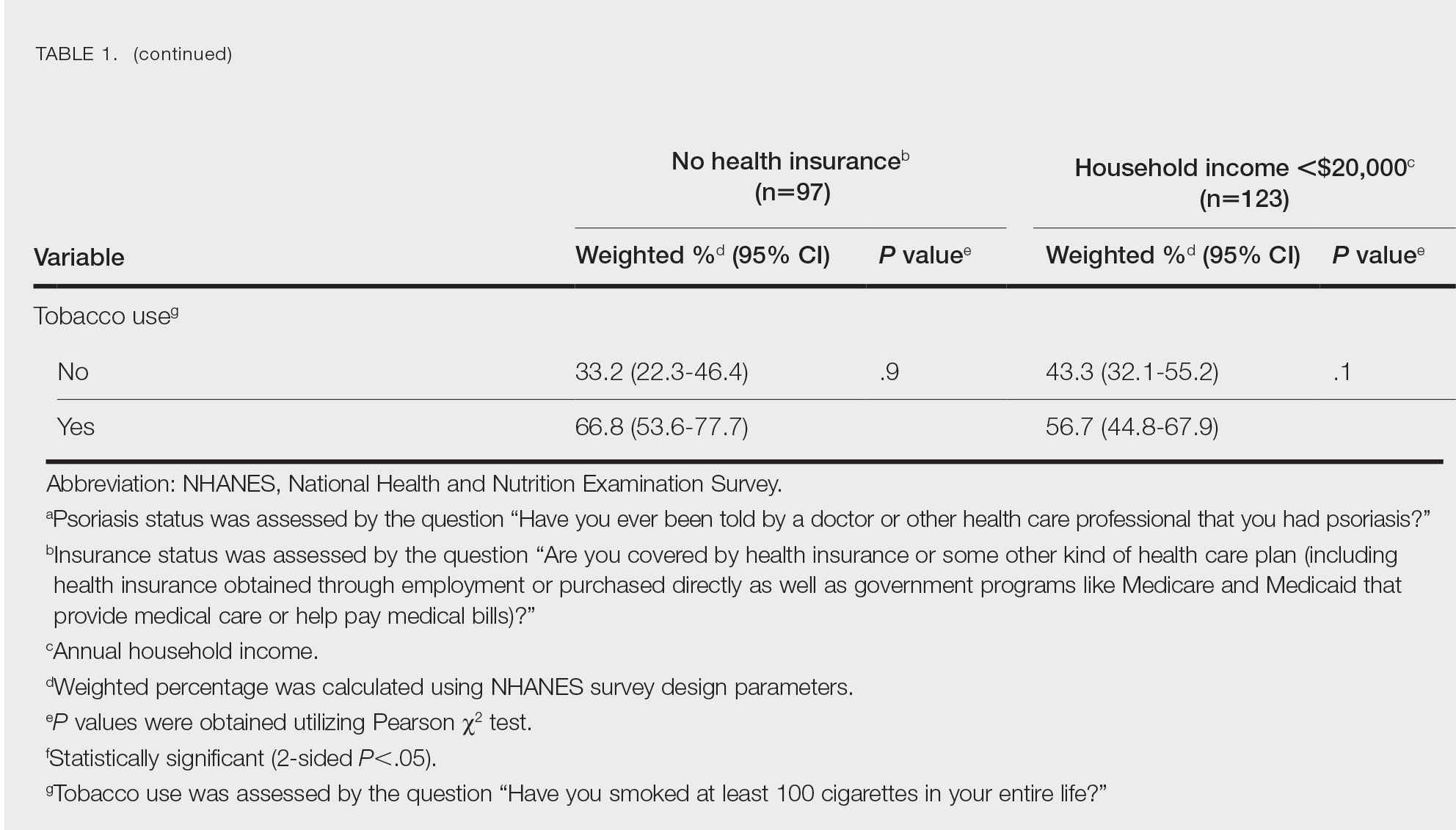

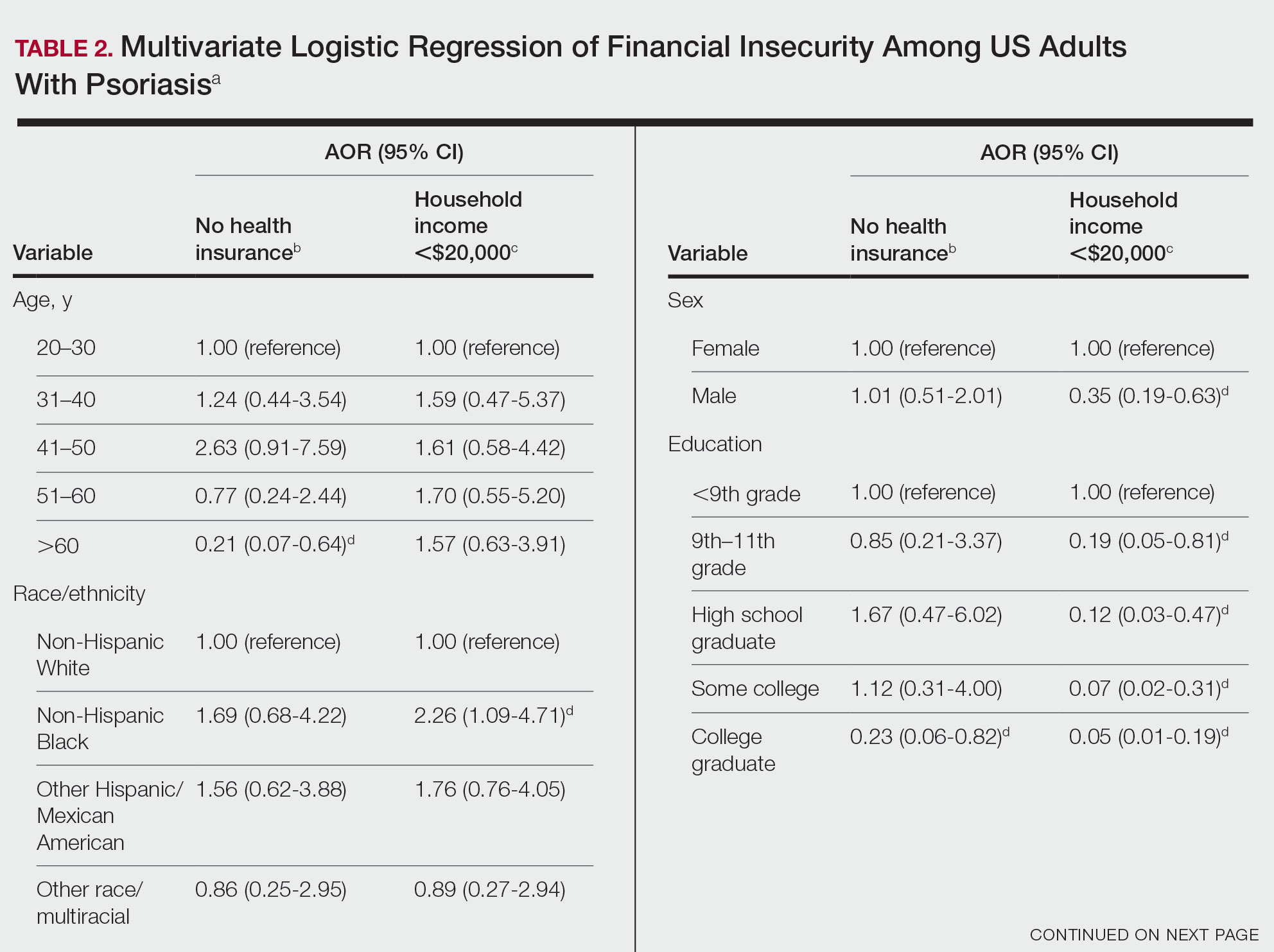

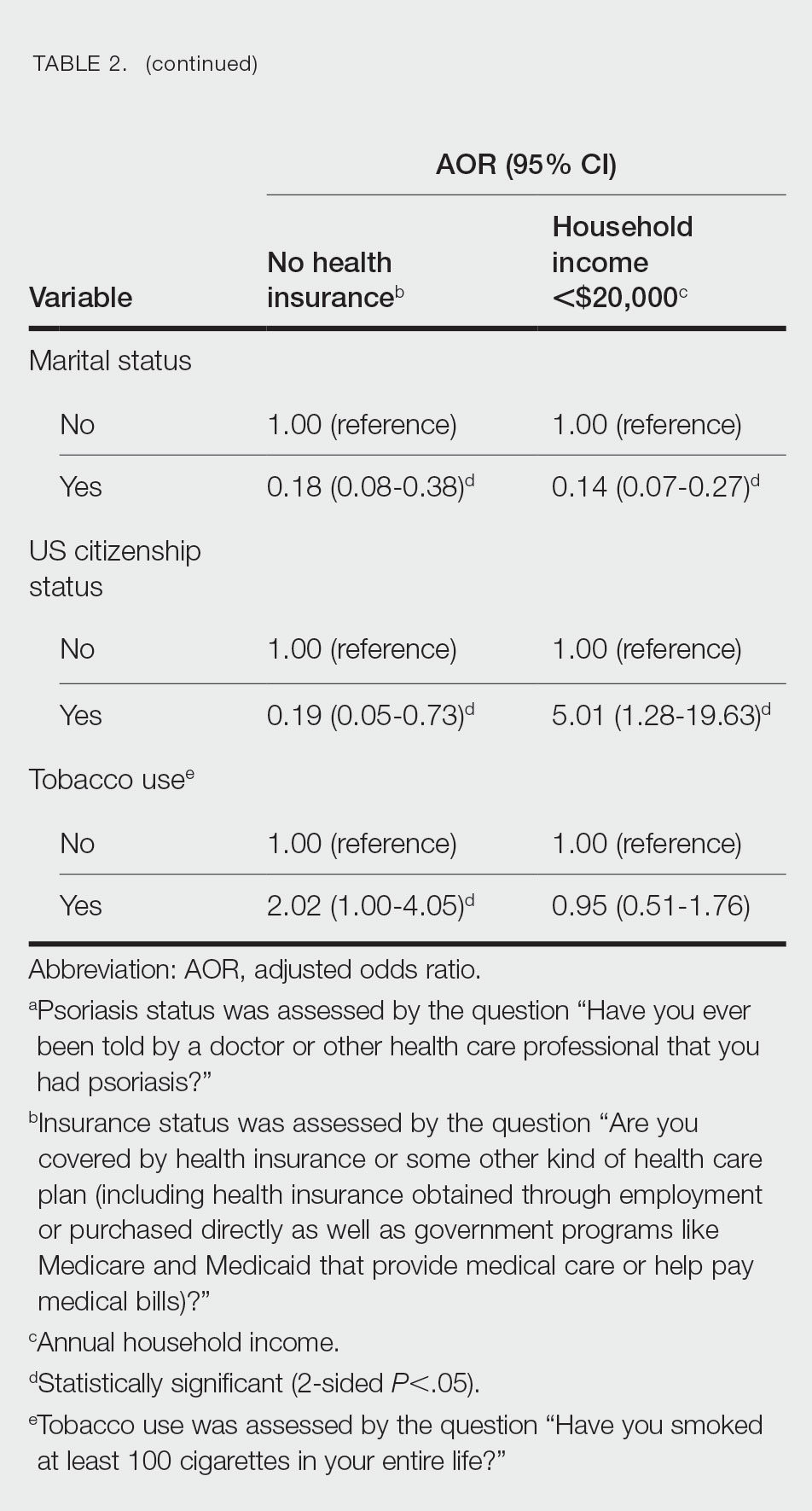

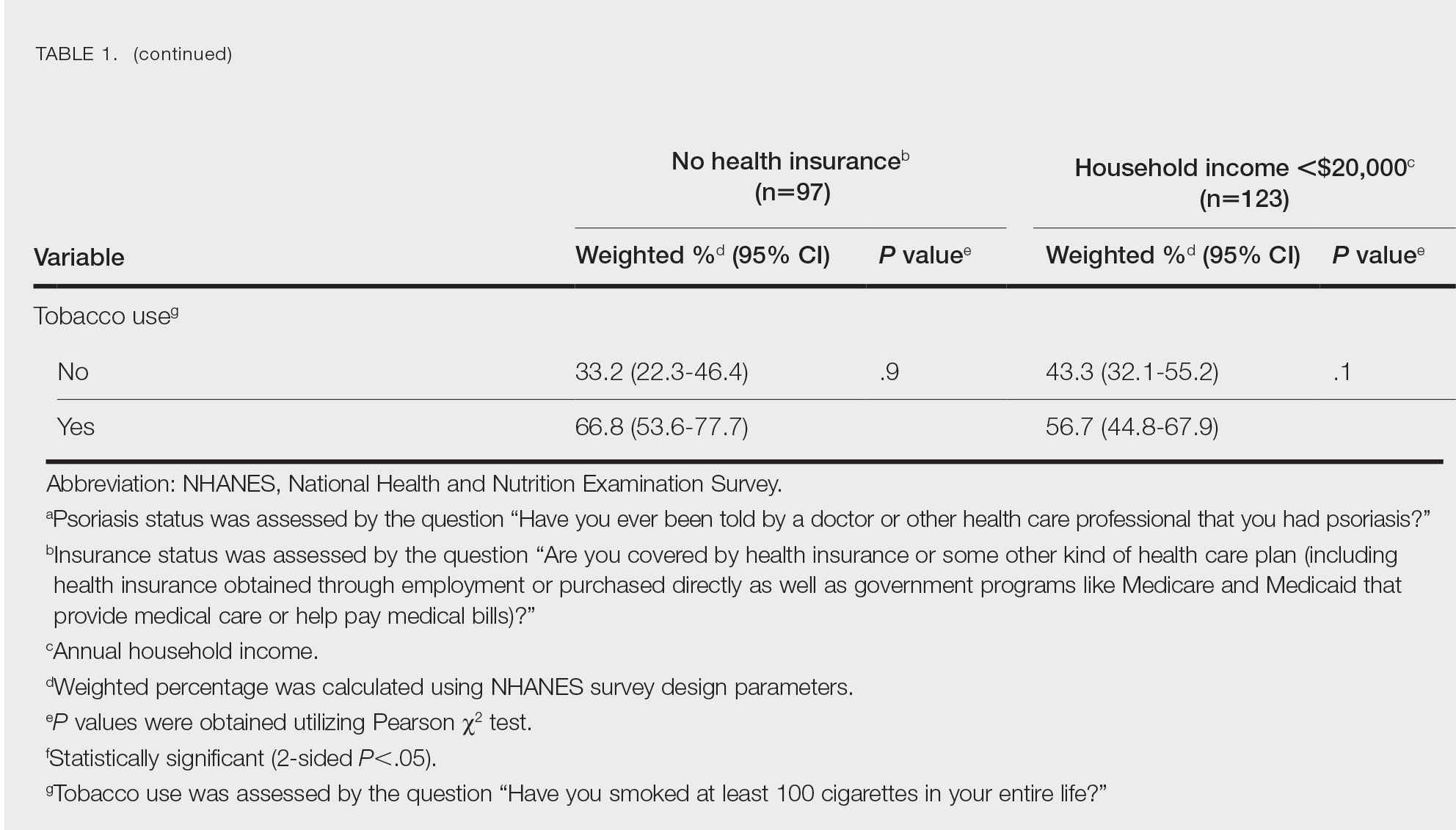

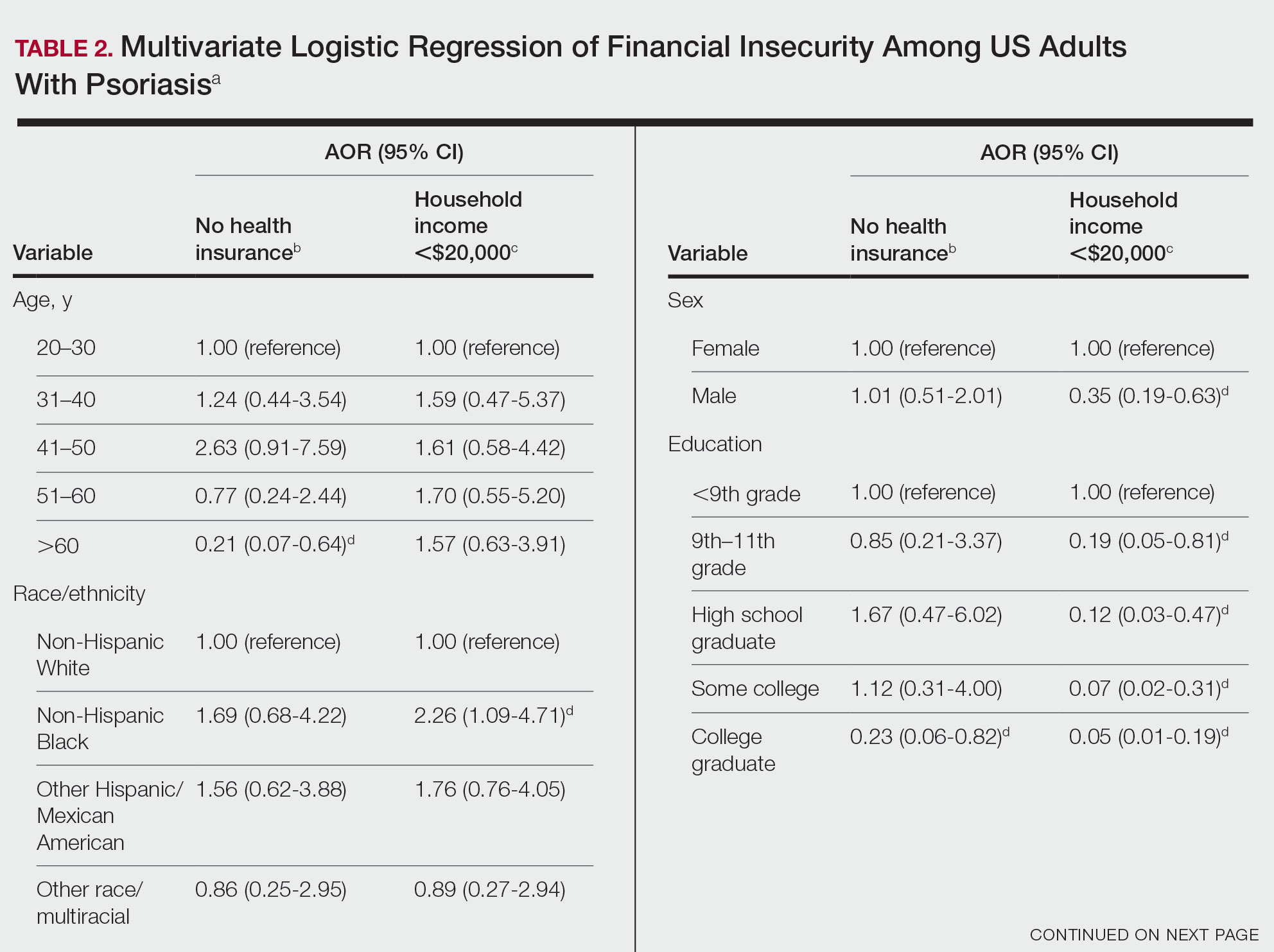

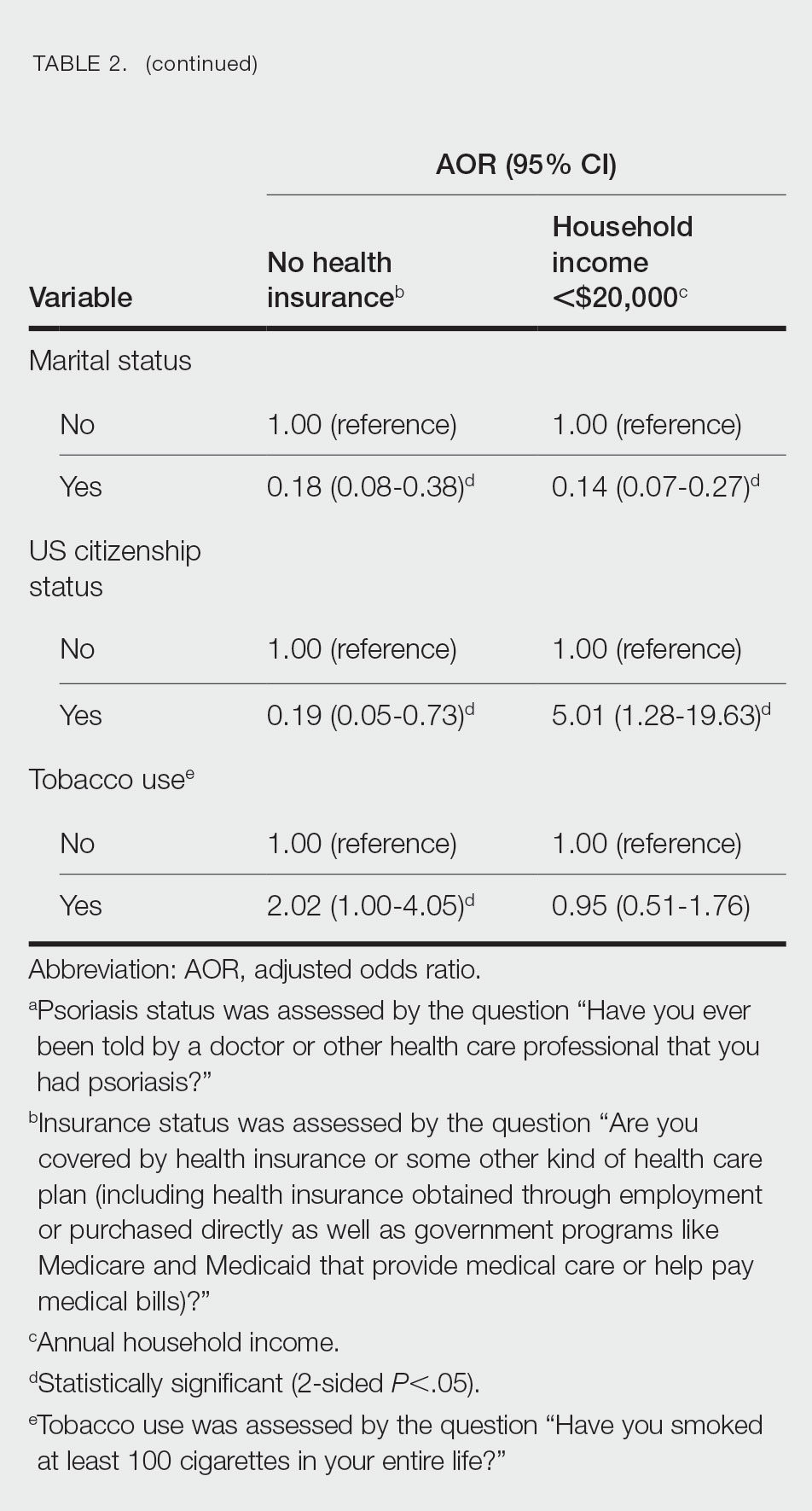

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

- Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, et al. Prevalence of psoriasis among adults in the US 2009-2010 and 2013-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:767-769. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.10.035

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.3593

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Maya-Rico AM, Londoño-García Á, Palacios-Barahona AU, et al. Out-of-pocket costs for patients with psoriasis in an outpatient dermatology referral service. An Bras Dermatol. 2021;96:295-300. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2020.09.004

- Cheng J, Feldman SR. The cost of biologics for psoriasis is increasing. Drugs Context. 2014;3:212266. doi:10.7573/dic.212266

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).

Our findings indicate that certain sociodemographic groups of psoriasis patients have an increased risk for being financially insecure. It is important to evaluate the cost of treatment, number of necessary visits to the office, and cost of transportation, as these factors can serve as a major economic burden to patients being managed for psoriasis.4 Additionally, the cost of biologics has been increasing over time.5 Taking all of this into account when caring for psoriasis patients is crucial, as understanding the financial status of patients can assist with determining appropriate individualized treatment regimens.

To the Editor:

Approximately 3% of the US population, or 6.9 million adults, is affected by psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a substantial impact on quality of life and is associated with increased health care expenses and medication costs. In 2013, it was reported that the estimated US annual cost—direct, indirect, intangible, and comorbidity costs—of psoriasis for adults was $112 billion.2 We investigated the prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics of adult psoriasis patients (aged ≥20 years) with financial insecurity utilizing the 2009–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data.3

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database to evaluate financial insecurity. Financial insecurity was evaluated by 2 outcome variables. The primary outcome variable was assessed by the question “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of health care plan (including health insurance obtained through employment or purchased directly as well as government programs like Medicare and Medicaid that provide medical care or help pay medical bills)?”3 Our secondary outcome variable was evaluated by a reported annual household income of less than $20,000. P values in Table 1 were calculated using Pearson χ2 tests. In Table 2, multivariate logistic regressions were performed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC) to analyze associations between outcome variables and sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex, education, marital status, US citizenship status, and tobacco use. Subsequently, relationships with P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Our analysis comprised 480 individuals with psoriasis; 40 individuals were excluded from our analysis because they did not report annual household income and health insurance status (Table 1). Among the 480 individuals with psoriasis, approximately 16% (weighted) reported a lack of health insurance, and approximately 17% (weighted) reported an annual household income of less than $20,000. Among those who reported an annual household income of less than $20,000, approximately 38% (weighted) of them reported that they did not have health insurance.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that elderly individuals (aged >60 years), college graduates, married individuals, and US citizens had decreased odds of lacking health insurance (Table 2). Additionally, those with a history of tobacco use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 2.02; 95% CI, 1.00-4.05) were associated with lacking health insurance. Non-Hispanic Black individuals (AOR 2.26; 95% CI, 1.09-4.71) and US citizens (AOR 5.01; 95% CI, 1.28-19.63) had a significant association with an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05). Lastly, males, those with education beyond ninth grade, and married individuals had a significantly decreased odds of having an annual household income of less than $20,000 (P<.05)(Table 2).