User login

Novel Intraoperative Technique to Visualize the Lower Cervical Spine: A Case Series

Two adequate views of the lower cervical vertebrae are necessary to confirm the 3-dimensional location of any hardware placed during cervical spine fusion. Visualizing the lower cervical vertebrae in 2 planes intraoperatively is often a challenge because the shoulders obstruct the lateral view.1 Techniques have been described to improve lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 These techniques have their inadequacies, including an association with peripheral nerve injury and brachial plexopathy.4 In patients with stout necks, these methods may still be insufficient to achieve adequate visualization of the lower cervical vertebrae.

Invasive techniques to improve visualization have also been described. In 1 study, exposure had to be extended cephalad to allow for manual counting of cervical vertebrae when the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae had to be identified in a morbidly obese patient.5 More invasive spine procedures are associated with higher rates of complications, increased blood loss, more soft-tissue trauma, and longer hospital stays.6 We present a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral as a variation of the lateral radiograph that improves visualization of the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae. The authors have obtained the patients’ informed written consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

We used either the Smith-Robinson or Cloward approach to the anterior spine. Both techniques use the avascular plane between the medially located esophagus and trachea and the lateral sternocleidomastoid and carotid sheath to approach the anterior cervical spine. Once adequate exposure was achieved, standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were obtained to confirm the correct vertebral level. Gentle caudal traction was applied to the patient’s wrist straps, and when visualization continued to be compromised, a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral was obtained (Figure 1).

Case Series

Case 1

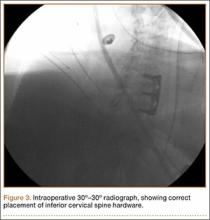

A 54-year-old man with a body mass index (BMI) of 50 presented with neck and bilateral arm pain, with left greater than right radicular symptoms in the C6 and C7 distribution. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed disc herniations at C5-C6 and C6-C7 with spinal cord signal changes, and he underwent a C5-C6 and C6-C7 anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Initial localization was determined using a lateral radiograph and vertebral needle. During hardware placement, anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic radiographs confirmed adequate placement of the superior screw, but visualization of the inferior portion of the plate and inferior screw was challenging (Figure 2). Our oblique 30º–30º view provided better visualization of the plate and screws in the lower cervical vertebrae than lateral imaging, and allowed confirmation that the hardware was positioned correctly (Figure 3). It took 1 attempt to achieve adequate visualization with the 30º–30º view.

Postoperatively, the patient’s radiculopathy and motor weakness improved. Radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement, and he was discharged on postoperative day 1 (Figure 4). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, anatomically aligned facet joints, and no hardware failure. The patient’s Neck Disability Index was 31/50 preoperatively and 26/50 at this visit.

Case 2

A 51-year-old man with a BMI of 29 presented with a long-standing history of neck pain and bilateral arm pain left greater than right in the C6 and C7 dermomyotome. MRI showed a broad-based disc herniation with foraminal narrowing at C5-C6 and C6-C7, and the patient underwent a 2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. This patient had pronounced neck musculature, and a deeper than normal incision was required.

Intraoperative lateral fluoroscopy was obtained to confirm the C5-C6 and C6-C7 level prior to discectomy. The musculature of the patient’s neck and shoulder made visualization of the C6-C7 disc space difficult on the lateral radiograph (Figure 5). One attempt was required to obtain the 30º–30º oblique view, which was used to ensure correct placement of the screws and plate (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, the patient’s pain had improved, and radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement. He was discharged 1 day after surgery (Figure 7). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, stable disc spaces, and anatomically aligned facet joints. His Neck Disability Index was 34/50 preoperatively and 32/50 at 2-week follow-up.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe an alternative to the lateral radiograph for imaging the cervical spine in patients with challenging anatomy or in procedures involving hardware placement at the lower cervical vertebrae. Techniques have been developed to assist with improved lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 However, visualization in 2 planes continues to be a challenge in a subset of patients. It is particularly difficult to obtain adequate lateral radiographs of the cervical spine in patients with stout necks.3 In patients with stout necks, there is more obstruction of the radiography path through the cervical spine. This leads to imaging that is unclear or may fail to show the mid- to lower cervical spine. The extent to which one should rely on the 30º–30º oblique technique for adequate visualization of the cervical spine depends on the anatomy of a particular patient. Historically, it is more challenging to obtain satisfactory lateral radiographs in patients with stout necks,3 and these patients have benefited the most from using the 30º–30º degree oblique view.

Lack of visualization can lead to aborted surgeries or, potentially, surgery at the wrong level.3 A 2008 American Academy of Neurological Surgeons survey indicated that 50% of spine surgeons had performed a wrong-level surgery at least once in their career, and the cervical spine accounted for 21% of all incorrect-level spine surgeries.7 Intraoperative factors reported during cases of wrong-level spinal surgeries included misinterpretation of intraoperative imaging, no intraoperative imaging, and unusual anatomy or physical characteristics.8 Such complications can lead to revision surgery and other significant morbidities for the patient.

In most patients, fluoroscopy allows confirmation of the correct level before disc incision.3 However, operating at a lower cervical level in a patient with a short neck or prominent shoulders poses a significant problem.3 A case report from Singh and colleagues9 described a modified intraoperative fluoroscopic view for spinal level localization at cervicothoracic levels. Their method focuses on identifying the bony lamina and using them as landmarks to count spinal levels, whereas our 30º–30º oblique image is useful for confirmation of adequate hardware placement during anterior cervical spinal fusions. Often, the initial localization of cervical vertebral levels can be achieved with a standard lateral radiograph. We recognized the utility of the 30º–30º oblique view when we were attempting to visualize the inferior aspect of the plate and inferior screw placement.

In patients with stout necks, a lateral radiograph may show only visualization down to C4 or C5.3 Even with applying traction to the arms or taping the shoulders down, it can be impossible to visualize C6, C7, or T1 because the shoulder bones and muscles obstruct the image.3 Using a 30º–30º oblique view, we were able to obtain adequate visualization and assess the accurate placement of hardware.

Conclusion

A 30º oblique view from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral radiograph can be used intraoperatively in patients with challenging anatomy to identify placement of hardware at the correct vertebral level in the lower cervical spine. It is a noninvasive technique that can help reduce the risk of wrong-site surgeries without prolonging operation time. This technique describes an alternative to the lateral radiograph and provides a solution to the difficult problem of intraoperative imaging of the mid- to lower cervical spine in 2 adequate planes.

1. Bebawy JF, Koht A, Mirkovic S. Anterior cervical spine surgery. In: Khot A, Sloan TB, Toleikis JR, eds. Monitoring the Nervous System for Anesthesiologists and Other Health Care Professionals. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:539-554.

2. Abumi K, Shono Y, Ito M, Taneichi H, Kotani Y, Kaneda K. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25(8):962-969.

3. Irace C. Intraoperative imaging for verification of the correct level during spinal surgery. In: Fountas KN, ed. Novel Frontiers of Advanced Neuroimaging. Rijeka, Croatia: Intech; 2013:175-188.

4. Schwartz DM, Sestokas AK, Hilibrand AS, et al. Neurophysiological identification of position-induced neurologic injury during anterior cervical spine surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2006;20(6):437-444.

5. Telfeian AE, Reiter GT, Durham SR, Marcotte P. Spine surgery in morbidly obese patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2002;97(1):20-24.

6. Oppenheimer JH, DeCastro I, McDonnell DE. Minimally invasive spine technology and minimally invasive spine surgery: a historical review. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(3):E9.

7. Mody MG, Nourbakhsh A, Stahl DL, Gibbs M, Alfawareh M, Garges KJ. The prevalence of wrong level surgery among spine surgeons. Spine. 2008;33(2):194.

8. Jhawar BS, Mitsis D, Duggal N. Wrong-sided and wrong-level neurosurgery: A national survey. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(5):467-472.

9. Singh H, Meyer SA, Hecht AC, Jenkins AL 3rd. Novel fluoroscopic technique for localization at cervicothoracic levels. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(8):615-618.

Two adequate views of the lower cervical vertebrae are necessary to confirm the 3-dimensional location of any hardware placed during cervical spine fusion. Visualizing the lower cervical vertebrae in 2 planes intraoperatively is often a challenge because the shoulders obstruct the lateral view.1 Techniques have been described to improve lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 These techniques have their inadequacies, including an association with peripheral nerve injury and brachial plexopathy.4 In patients with stout necks, these methods may still be insufficient to achieve adequate visualization of the lower cervical vertebrae.

Invasive techniques to improve visualization have also been described. In 1 study, exposure had to be extended cephalad to allow for manual counting of cervical vertebrae when the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae had to be identified in a morbidly obese patient.5 More invasive spine procedures are associated with higher rates of complications, increased blood loss, more soft-tissue trauma, and longer hospital stays.6 We present a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral as a variation of the lateral radiograph that improves visualization of the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae. The authors have obtained the patients’ informed written consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

We used either the Smith-Robinson or Cloward approach to the anterior spine. Both techniques use the avascular plane between the medially located esophagus and trachea and the lateral sternocleidomastoid and carotid sheath to approach the anterior cervical spine. Once adequate exposure was achieved, standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were obtained to confirm the correct vertebral level. Gentle caudal traction was applied to the patient’s wrist straps, and when visualization continued to be compromised, a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral was obtained (Figure 1).

Case Series

Case 1

A 54-year-old man with a body mass index (BMI) of 50 presented with neck and bilateral arm pain, with left greater than right radicular symptoms in the C6 and C7 distribution. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed disc herniations at C5-C6 and C6-C7 with spinal cord signal changes, and he underwent a C5-C6 and C6-C7 anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Initial localization was determined using a lateral radiograph and vertebral needle. During hardware placement, anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic radiographs confirmed adequate placement of the superior screw, but visualization of the inferior portion of the plate and inferior screw was challenging (Figure 2). Our oblique 30º–30º view provided better visualization of the plate and screws in the lower cervical vertebrae than lateral imaging, and allowed confirmation that the hardware was positioned correctly (Figure 3). It took 1 attempt to achieve adequate visualization with the 30º–30º view.

Postoperatively, the patient’s radiculopathy and motor weakness improved. Radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement, and he was discharged on postoperative day 1 (Figure 4). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, anatomically aligned facet joints, and no hardware failure. The patient’s Neck Disability Index was 31/50 preoperatively and 26/50 at this visit.

Case 2

A 51-year-old man with a BMI of 29 presented with a long-standing history of neck pain and bilateral arm pain left greater than right in the C6 and C7 dermomyotome. MRI showed a broad-based disc herniation with foraminal narrowing at C5-C6 and C6-C7, and the patient underwent a 2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. This patient had pronounced neck musculature, and a deeper than normal incision was required.

Intraoperative lateral fluoroscopy was obtained to confirm the C5-C6 and C6-C7 level prior to discectomy. The musculature of the patient’s neck and shoulder made visualization of the C6-C7 disc space difficult on the lateral radiograph (Figure 5). One attempt was required to obtain the 30º–30º oblique view, which was used to ensure correct placement of the screws and plate (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, the patient’s pain had improved, and radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement. He was discharged 1 day after surgery (Figure 7). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, stable disc spaces, and anatomically aligned facet joints. His Neck Disability Index was 34/50 preoperatively and 32/50 at 2-week follow-up.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe an alternative to the lateral radiograph for imaging the cervical spine in patients with challenging anatomy or in procedures involving hardware placement at the lower cervical vertebrae. Techniques have been developed to assist with improved lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 However, visualization in 2 planes continues to be a challenge in a subset of patients. It is particularly difficult to obtain adequate lateral radiographs of the cervical spine in patients with stout necks.3 In patients with stout necks, there is more obstruction of the radiography path through the cervical spine. This leads to imaging that is unclear or may fail to show the mid- to lower cervical spine. The extent to which one should rely on the 30º–30º oblique technique for adequate visualization of the cervical spine depends on the anatomy of a particular patient. Historically, it is more challenging to obtain satisfactory lateral radiographs in patients with stout necks,3 and these patients have benefited the most from using the 30º–30º degree oblique view.

Lack of visualization can lead to aborted surgeries or, potentially, surgery at the wrong level.3 A 2008 American Academy of Neurological Surgeons survey indicated that 50% of spine surgeons had performed a wrong-level surgery at least once in their career, and the cervical spine accounted for 21% of all incorrect-level spine surgeries.7 Intraoperative factors reported during cases of wrong-level spinal surgeries included misinterpretation of intraoperative imaging, no intraoperative imaging, and unusual anatomy or physical characteristics.8 Such complications can lead to revision surgery and other significant morbidities for the patient.

In most patients, fluoroscopy allows confirmation of the correct level before disc incision.3 However, operating at a lower cervical level in a patient with a short neck or prominent shoulders poses a significant problem.3 A case report from Singh and colleagues9 described a modified intraoperative fluoroscopic view for spinal level localization at cervicothoracic levels. Their method focuses on identifying the bony lamina and using them as landmarks to count spinal levels, whereas our 30º–30º oblique image is useful for confirmation of adequate hardware placement during anterior cervical spinal fusions. Often, the initial localization of cervical vertebral levels can be achieved with a standard lateral radiograph. We recognized the utility of the 30º–30º oblique view when we were attempting to visualize the inferior aspect of the plate and inferior screw placement.

In patients with stout necks, a lateral radiograph may show only visualization down to C4 or C5.3 Even with applying traction to the arms or taping the shoulders down, it can be impossible to visualize C6, C7, or T1 because the shoulder bones and muscles obstruct the image.3 Using a 30º–30º oblique view, we were able to obtain adequate visualization and assess the accurate placement of hardware.

Conclusion

A 30º oblique view from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral radiograph can be used intraoperatively in patients with challenging anatomy to identify placement of hardware at the correct vertebral level in the lower cervical spine. It is a noninvasive technique that can help reduce the risk of wrong-site surgeries without prolonging operation time. This technique describes an alternative to the lateral radiograph and provides a solution to the difficult problem of intraoperative imaging of the mid- to lower cervical spine in 2 adequate planes.

Two adequate views of the lower cervical vertebrae are necessary to confirm the 3-dimensional location of any hardware placed during cervical spine fusion. Visualizing the lower cervical vertebrae in 2 planes intraoperatively is often a challenge because the shoulders obstruct the lateral view.1 Techniques have been described to improve lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 These techniques have their inadequacies, including an association with peripheral nerve injury and brachial plexopathy.4 In patients with stout necks, these methods may still be insufficient to achieve adequate visualization of the lower cervical vertebrae.

Invasive techniques to improve visualization have also been described. In 1 study, exposure had to be extended cephalad to allow for manual counting of cervical vertebrae when the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae had to be identified in a morbidly obese patient.5 More invasive spine procedures are associated with higher rates of complications, increased blood loss, more soft-tissue trauma, and longer hospital stays.6 We present a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral as a variation of the lateral radiograph that improves visualization of the mid- to lower cervical vertebrae. The authors have obtained the patients’ informed written consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Technique

We used either the Smith-Robinson or Cloward approach to the anterior spine. Both techniques use the avascular plane between the medially located esophagus and trachea and the lateral sternocleidomastoid and carotid sheath to approach the anterior cervical spine. Once adequate exposure was achieved, standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were obtained to confirm the correct vertebral level. Gentle caudal traction was applied to the patient’s wrist straps, and when visualization continued to be compromised, a view 30º oblique from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral was obtained (Figure 1).

Case Series

Case 1

A 54-year-old man with a body mass index (BMI) of 50 presented with neck and bilateral arm pain, with left greater than right radicular symptoms in the C6 and C7 distribution. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed disc herniations at C5-C6 and C6-C7 with spinal cord signal changes, and he underwent a C5-C6 and C6-C7 anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Initial localization was determined using a lateral radiograph and vertebral needle. During hardware placement, anteroposterior and lateral fluoroscopic radiographs confirmed adequate placement of the superior screw, but visualization of the inferior portion of the plate and inferior screw was challenging (Figure 2). Our oblique 30º–30º view provided better visualization of the plate and screws in the lower cervical vertebrae than lateral imaging, and allowed confirmation that the hardware was positioned correctly (Figure 3). It took 1 attempt to achieve adequate visualization with the 30º–30º view.

Postoperatively, the patient’s radiculopathy and motor weakness improved. Radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement, and he was discharged on postoperative day 1 (Figure 4). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, anatomically aligned facet joints, and no hardware failure. The patient’s Neck Disability Index was 31/50 preoperatively and 26/50 at this visit.

Case 2

A 51-year-old man with a BMI of 29 presented with a long-standing history of neck pain and bilateral arm pain left greater than right in the C6 and C7 dermomyotome. MRI showed a broad-based disc herniation with foraminal narrowing at C5-C6 and C6-C7, and the patient underwent a 2-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. This patient had pronounced neck musculature, and a deeper than normal incision was required.

Intraoperative lateral fluoroscopy was obtained to confirm the C5-C6 and C6-C7 level prior to discectomy. The musculature of the patient’s neck and shoulder made visualization of the C6-C7 disc space difficult on the lateral radiograph (Figure 5). One attempt was required to obtain the 30º–30º oblique view, which was used to ensure correct placement of the screws and plate (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, the patient’s pain had improved, and radiographs confirmed adequate hardware placement. He was discharged 1 day after surgery (Figure 7). Imaging at the patient’s 6-week follow-up confirmed adequate fusion from C5-C7, stable disc spaces, and anatomically aligned facet joints. His Neck Disability Index was 34/50 preoperatively and 32/50 at 2-week follow-up.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to describe an alternative to the lateral radiograph for imaging the cervical spine in patients with challenging anatomy or in procedures involving hardware placement at the lower cervical vertebrae. Techniques have been developed to assist with improved lateral visualization, including gentle traction of the arms via wrist restraints or taping the shoulders down inferiorly.2,3 However, visualization in 2 planes continues to be a challenge in a subset of patients. It is particularly difficult to obtain adequate lateral radiographs of the cervical spine in patients with stout necks.3 In patients with stout necks, there is more obstruction of the radiography path through the cervical spine. This leads to imaging that is unclear or may fail to show the mid- to lower cervical spine. The extent to which one should rely on the 30º–30º oblique technique for adequate visualization of the cervical spine depends on the anatomy of a particular patient. Historically, it is more challenging to obtain satisfactory lateral radiographs in patients with stout necks,3 and these patients have benefited the most from using the 30º–30º degree oblique view.

Lack of visualization can lead to aborted surgeries or, potentially, surgery at the wrong level.3 A 2008 American Academy of Neurological Surgeons survey indicated that 50% of spine surgeons had performed a wrong-level surgery at least once in their career, and the cervical spine accounted for 21% of all incorrect-level spine surgeries.7 Intraoperative factors reported during cases of wrong-level spinal surgeries included misinterpretation of intraoperative imaging, no intraoperative imaging, and unusual anatomy or physical characteristics.8 Such complications can lead to revision surgery and other significant morbidities for the patient.

In most patients, fluoroscopy allows confirmation of the correct level before disc incision.3 However, operating at a lower cervical level in a patient with a short neck or prominent shoulders poses a significant problem.3 A case report from Singh and colleagues9 described a modified intraoperative fluoroscopic view for spinal level localization at cervicothoracic levels. Their method focuses on identifying the bony lamina and using them as landmarks to count spinal levels, whereas our 30º–30º oblique image is useful for confirmation of adequate hardware placement during anterior cervical spinal fusions. Often, the initial localization of cervical vertebral levels can be achieved with a standard lateral radiograph. We recognized the utility of the 30º–30º oblique view when we were attempting to visualize the inferior aspect of the plate and inferior screw placement.

In patients with stout necks, a lateral radiograph may show only visualization down to C4 or C5.3 Even with applying traction to the arms or taping the shoulders down, it can be impossible to visualize C6, C7, or T1 because the shoulder bones and muscles obstruct the image.3 Using a 30º–30º oblique view, we were able to obtain adequate visualization and assess the accurate placement of hardware.

Conclusion

A 30º oblique view from horizontal and 30º cephalad from neutral radiograph can be used intraoperatively in patients with challenging anatomy to identify placement of hardware at the correct vertebral level in the lower cervical spine. It is a noninvasive technique that can help reduce the risk of wrong-site surgeries without prolonging operation time. This technique describes an alternative to the lateral radiograph and provides a solution to the difficult problem of intraoperative imaging of the mid- to lower cervical spine in 2 adequate planes.

1. Bebawy JF, Koht A, Mirkovic S. Anterior cervical spine surgery. In: Khot A, Sloan TB, Toleikis JR, eds. Monitoring the Nervous System for Anesthesiologists and Other Health Care Professionals. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:539-554.

2. Abumi K, Shono Y, Ito M, Taneichi H, Kotani Y, Kaneda K. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25(8):962-969.

3. Irace C. Intraoperative imaging for verification of the correct level during spinal surgery. In: Fountas KN, ed. Novel Frontiers of Advanced Neuroimaging. Rijeka, Croatia: Intech; 2013:175-188.

4. Schwartz DM, Sestokas AK, Hilibrand AS, et al. Neurophysiological identification of position-induced neurologic injury during anterior cervical spine surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2006;20(6):437-444.

5. Telfeian AE, Reiter GT, Durham SR, Marcotte P. Spine surgery in morbidly obese patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2002;97(1):20-24.

6. Oppenheimer JH, DeCastro I, McDonnell DE. Minimally invasive spine technology and minimally invasive spine surgery: a historical review. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(3):E9.

7. Mody MG, Nourbakhsh A, Stahl DL, Gibbs M, Alfawareh M, Garges KJ. The prevalence of wrong level surgery among spine surgeons. Spine. 2008;33(2):194.

8. Jhawar BS, Mitsis D, Duggal N. Wrong-sided and wrong-level neurosurgery: A national survey. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(5):467-472.

9. Singh H, Meyer SA, Hecht AC, Jenkins AL 3rd. Novel fluoroscopic technique for localization at cervicothoracic levels. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(8):615-618.

1. Bebawy JF, Koht A, Mirkovic S. Anterior cervical spine surgery. In: Khot A, Sloan TB, Toleikis JR, eds. Monitoring the Nervous System for Anesthesiologists and Other Health Care Professionals. New York, NY: Springer; 2012:539-554.

2. Abumi K, Shono Y, Ito M, Taneichi H, Kotani Y, Kaneda K. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25(8):962-969.

3. Irace C. Intraoperative imaging for verification of the correct level during spinal surgery. In: Fountas KN, ed. Novel Frontiers of Advanced Neuroimaging. Rijeka, Croatia: Intech; 2013:175-188.

4. Schwartz DM, Sestokas AK, Hilibrand AS, et al. Neurophysiological identification of position-induced neurologic injury during anterior cervical spine surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2006;20(6):437-444.

5. Telfeian AE, Reiter GT, Durham SR, Marcotte P. Spine surgery in morbidly obese patients. J Neurosurg Spine. 2002;97(1):20-24.

6. Oppenheimer JH, DeCastro I, McDonnell DE. Minimally invasive spine technology and minimally invasive spine surgery: a historical review. Neurosurg Focus. 2009;27(3):E9.

7. Mody MG, Nourbakhsh A, Stahl DL, Gibbs M, Alfawareh M, Garges KJ. The prevalence of wrong level surgery among spine surgeons. Spine. 2008;33(2):194.

8. Jhawar BS, Mitsis D, Duggal N. Wrong-sided and wrong-level neurosurgery: A national survey. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7(5):467-472.

9. Singh H, Meyer SA, Hecht AC, Jenkins AL 3rd. Novel fluoroscopic technique for localization at cervicothoracic levels. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(8):615-618.

Technique for Lumbar Pedicle Subtraction Osteotomy for Sagittal Plane Deformity in Revision

Pedicle subtraction osteotomies (PSOs) have been used in the treatment of multiple spinal conditions involving a fixed sagittal imbalance, such as degenerative scoliosis, idiopathic scoliosis, posttraumatic deformities, iatrogenic flatback syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis. The procedure was first described by Thomasen1 for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. More recently, multiple centers have reported the expanded use and good success of PSO in the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance of other etiologies.2,3 According to Bridwell and colleagues,2 lumbar lordosis can be increased 34.1°, and sagittal plumb line can be improved 13.5 cm.

PSO is a complex, extensive surgery most often performed in the revision setting. Multiple authors have described the technique for PSO.4,5 There are significant technical challenges and many complications, including neurologic deficits, pseudarthrosis of adjacent levels, and wound infections.6 Short-term challenges include a large loss of blood, 2.4 L on average, according to Bridwell and colleagues.6 Time of closure of the osteotomy gap is a crucial point in the surgery. Blood loss, often large, slows only after the gap is closed and stabilized.

In this article, we describe a technique in which an additional rod or pedicle screw construct is used at the periosteotomy levels to close the osteotomy gap during PSO and simplify subsequent instrumentation. In addition, we report our experience with the procedure.

Materials and Methods

Seventeen consecutive patients (mean age, 58 years; range, 12-81 years) with fixed sagittal imbalance were treated with lumbar PSO. The indication in all cases was flatback syndrome after previous spinal surgery. Mean follow-up was 13 months. Mean number of prior surgeries was 3. Thirteen PSOs were performed at L3, and 4 were performed at L2.

Radiographic data were collected from before surgery, in the immediate postoperative period, and at final follow-up. All the radiographs were standing films. Established radiographic parameters were measured: thoracic kyphosis from T5 to T12, lumbar lordosis from L1 to S1, PSO angle (1 level above to 1 level below osteotomy level), sagittal plumb line (from center of C7 body to posterosuperior aspect of S1 body), and coronal plumb line (from center of C7 body to center of S1 body).2

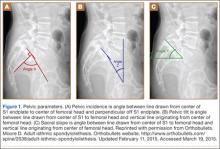

Good clinical outcomes in the treatment of spinal disorders require careful attention to the alignment of the spine in the sagittal plane.7,8 When evaluating the preoperative radiographs, we measured and documented pelvic parameters. Figure 1A shows how pelvic incidence was determined. We measured this as the angle between a line drawn from the center of the S1 endplate to the center of the femoral head and the perpendicular off the S1 endplate. Figure 1B shows pelvic tilt as determined by the angle between a line drawn from the center of S1 to the femoral head and a vertical line originating from the center of the femoral head. Figure 1C shows the sacral slope, which we measured as the angle between a line drawn parallel to the endplate of S1 and its intersection with a horizontal line.

Surgical Technique

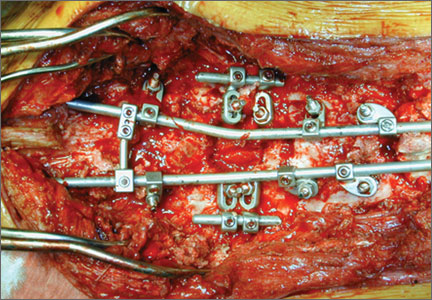

The overall surgical technique for PSO has been well described.4,5 Here we describe the “outrigger” modification to osteotomy closure (Figures 2, 3).

Most of our 17 cases were revisions. In these cases, new fixation points are first established. All fixation points that will be needed for the final fusion are placed. If a pedicle above or below the osteotomy level is not suitable for a screw, it can be skipped.

Wide decompression of the involved level is performed from pedicle to pedicle, ensuring that the nerve roots are completely decompressed. The dissection is then continued around the lateral wall of the vertebral body. While the neural elements are protected with gentle retraction, the pedicle and a portion of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body are removed with a combination of a rongeur and reverse-angle curettes. Resection of the vertebral body can be facilitated by attaching a short rod to the pedicle screws on either side of the osteotomy level and using it to provide gentle distraction.

Once sufficient bone has been removed to close the osteotomy, short rods are placed in the pedicle screws in the level above and the level below the osteotomy site. These rods are attached with offset connectors that allow the rods to be placed lateral to the screws. Before the surgical procedure is started, the patient is positioned on 2 sets of posts separated by the break in the table. The break in the table allows flexion to accommodate the preoperative kyphosis and allows hyperextension to help close the osteotomy site. Now, with the osteotomy site ready for closure, the table is gradually positioned in extension along with a combination of posterior pressure and compression between the pedicle screws above and below the osteotomy. Once the osteotomy is adequately compressed, the short rods are tightened, holding the osteotomy in good position. With the osteotomy held by the short rods and table positioning, decompression of the neural elements is confirmed and hemostasis obtained.

Final instrumentation is then performed with long rods that can bypass the osteotomized levels, allowing for simpler contouring. If desired, a cross connector can be placed between the long rod of the fusion construct and the short rod holding the osteotomy. The rest of the fusion procedure is completed in standard fashion with at least 1 subfascial drain.

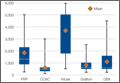

Results

Our 17 patients’ results are summarized in the Table. Mean sagittal plumb line improved from 17.7 cm (range, 5.9 to 29 cm) before surgery to 4.5 cm (range, –0.2 to 12.9 cm) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 13.2 cm. At final follow-up, mean sagittal plumb line was 5.1 cm (range, –1.4 to 10.2 cm).

Mean lumbar lordosis improved from 10° (range, –14° to 34°) before surgery to 49° (range, 36° to 63°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 39°. Mean PSO angle improved from 3° (range, –36° to 23°) before surgery to 41° (range, 25° to 65°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 38°. At final follow-up, mean lumbar lordosis remained at 47° (range, 26° to 64°), and mean PSO angle was 39° (range, 24° to 59°).

Mean thoracic kyphosis improved from 18° (range, –8° to 52°) before surgery to 30° (range, 3° to 58°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 12°. At final follow-up, mean thoracic kyphosis was 31° (range, 2° to 57°).

Fourteen patients did not have complications during the study period. Of the 3 patients with complications, 1 had an early infection, treated effectively with irrigation and débridement and intravenous antibiotics; 1 had a late deep infection, treated with multiple débridements, hardware removal, and, eventually, suppressive antibiotics; and 1 had cauda equina syndrome (caused by extensive scar tissue on the dura, which buckled with restoration of lordosis leading to cord compression), treated with duraplasty, which resulted in full neurologic recovery.

Discussion

In the present series of patients, the described technique for facilitating PSO for correction of sagittal imbalance was effective, and complications were similar to those previously reported.

The benefit of the outrigger construct is that it allows controlled compression of the osteotomy site and can be left in place at time of final instrumentation, locking in compression and correction. Other techniques involve removing the temporary rod and replacing it with final instrumentation4,5—an extra step that complicates instrumentation of the additional levels of the fusion construct and possibly adds pedicle screw stress and contributes to loosening when the new rod is reduced to the pedicle screw. The final long rod construct can bypass the osteotomy levels and allow for simpler instrumentation.

Mean age was 58 years in this series versus 52.4 years in the series reported by Bridwell and colleagues.2 Given the higher mean age of our patients, though no objective measures of bone quality were available, this technique is likely applicable to patients with poor bone quality.

The complications we have reported are in line with those reported in previous series, and maintenance of radiographic parameters at final follow-up indicates that this osteotomy technique allows for solid fusion constructs.

The outrigger technique for controlling PSO closure is an effective method that simplifies instrumentation during a complex revision case.

1. Thomasen E. Vertebral osteotomy for correction of kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop. 1985;(194):142-152.

2. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(3):454-463.

3. Berven SH, Deviren V, Smith JA, Emami A, Hu SS, Bradford DS. Management of fixed sagittal plane deformity: results of the transpedicular wedge resection osteotomy. Spine. 2001;26(18):2036-2043.

4. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Rinella A, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):44-50.

5. Wang MY, Berven SH. Lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2 suppl 1):ONS140-ONS146.

6. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Edwards C, et al. Complications and outcomes of pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine. 2003;28(18):2093-2101.

7. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):260-267.

8. Schwab F, Lafage V, Patel A, Farcy JP. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adult patient. Spine. 2009;34(17):1828-1833.

Pedicle subtraction osteotomies (PSOs) have been used in the treatment of multiple spinal conditions involving a fixed sagittal imbalance, such as degenerative scoliosis, idiopathic scoliosis, posttraumatic deformities, iatrogenic flatback syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis. The procedure was first described by Thomasen1 for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. More recently, multiple centers have reported the expanded use and good success of PSO in the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance of other etiologies.2,3 According to Bridwell and colleagues,2 lumbar lordosis can be increased 34.1°, and sagittal plumb line can be improved 13.5 cm.

PSO is a complex, extensive surgery most often performed in the revision setting. Multiple authors have described the technique for PSO.4,5 There are significant technical challenges and many complications, including neurologic deficits, pseudarthrosis of adjacent levels, and wound infections.6 Short-term challenges include a large loss of blood, 2.4 L on average, according to Bridwell and colleagues.6 Time of closure of the osteotomy gap is a crucial point in the surgery. Blood loss, often large, slows only after the gap is closed and stabilized.

In this article, we describe a technique in which an additional rod or pedicle screw construct is used at the periosteotomy levels to close the osteotomy gap during PSO and simplify subsequent instrumentation. In addition, we report our experience with the procedure.

Materials and Methods

Seventeen consecutive patients (mean age, 58 years; range, 12-81 years) with fixed sagittal imbalance were treated with lumbar PSO. The indication in all cases was flatback syndrome after previous spinal surgery. Mean follow-up was 13 months. Mean number of prior surgeries was 3. Thirteen PSOs were performed at L3, and 4 were performed at L2.

Radiographic data were collected from before surgery, in the immediate postoperative period, and at final follow-up. All the radiographs were standing films. Established radiographic parameters were measured: thoracic kyphosis from T5 to T12, lumbar lordosis from L1 to S1, PSO angle (1 level above to 1 level below osteotomy level), sagittal plumb line (from center of C7 body to posterosuperior aspect of S1 body), and coronal plumb line (from center of C7 body to center of S1 body).2

Good clinical outcomes in the treatment of spinal disorders require careful attention to the alignment of the spine in the sagittal plane.7,8 When evaluating the preoperative radiographs, we measured and documented pelvic parameters. Figure 1A shows how pelvic incidence was determined. We measured this as the angle between a line drawn from the center of the S1 endplate to the center of the femoral head and the perpendicular off the S1 endplate. Figure 1B shows pelvic tilt as determined by the angle between a line drawn from the center of S1 to the femoral head and a vertical line originating from the center of the femoral head. Figure 1C shows the sacral slope, which we measured as the angle between a line drawn parallel to the endplate of S1 and its intersection with a horizontal line.

Surgical Technique

The overall surgical technique for PSO has been well described.4,5 Here we describe the “outrigger” modification to osteotomy closure (Figures 2, 3).

Most of our 17 cases were revisions. In these cases, new fixation points are first established. All fixation points that will be needed for the final fusion are placed. If a pedicle above or below the osteotomy level is not suitable for a screw, it can be skipped.

Wide decompression of the involved level is performed from pedicle to pedicle, ensuring that the nerve roots are completely decompressed. The dissection is then continued around the lateral wall of the vertebral body. While the neural elements are protected with gentle retraction, the pedicle and a portion of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body are removed with a combination of a rongeur and reverse-angle curettes. Resection of the vertebral body can be facilitated by attaching a short rod to the pedicle screws on either side of the osteotomy level and using it to provide gentle distraction.

Once sufficient bone has been removed to close the osteotomy, short rods are placed in the pedicle screws in the level above and the level below the osteotomy site. These rods are attached with offset connectors that allow the rods to be placed lateral to the screws. Before the surgical procedure is started, the patient is positioned on 2 sets of posts separated by the break in the table. The break in the table allows flexion to accommodate the preoperative kyphosis and allows hyperextension to help close the osteotomy site. Now, with the osteotomy site ready for closure, the table is gradually positioned in extension along with a combination of posterior pressure and compression between the pedicle screws above and below the osteotomy. Once the osteotomy is adequately compressed, the short rods are tightened, holding the osteotomy in good position. With the osteotomy held by the short rods and table positioning, decompression of the neural elements is confirmed and hemostasis obtained.

Final instrumentation is then performed with long rods that can bypass the osteotomized levels, allowing for simpler contouring. If desired, a cross connector can be placed between the long rod of the fusion construct and the short rod holding the osteotomy. The rest of the fusion procedure is completed in standard fashion with at least 1 subfascial drain.

Results

Our 17 patients’ results are summarized in the Table. Mean sagittal plumb line improved from 17.7 cm (range, 5.9 to 29 cm) before surgery to 4.5 cm (range, –0.2 to 12.9 cm) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 13.2 cm. At final follow-up, mean sagittal plumb line was 5.1 cm (range, –1.4 to 10.2 cm).

Mean lumbar lordosis improved from 10° (range, –14° to 34°) before surgery to 49° (range, 36° to 63°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 39°. Mean PSO angle improved from 3° (range, –36° to 23°) before surgery to 41° (range, 25° to 65°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 38°. At final follow-up, mean lumbar lordosis remained at 47° (range, 26° to 64°), and mean PSO angle was 39° (range, 24° to 59°).

Mean thoracic kyphosis improved from 18° (range, –8° to 52°) before surgery to 30° (range, 3° to 58°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 12°. At final follow-up, mean thoracic kyphosis was 31° (range, 2° to 57°).

Fourteen patients did not have complications during the study period. Of the 3 patients with complications, 1 had an early infection, treated effectively with irrigation and débridement and intravenous antibiotics; 1 had a late deep infection, treated with multiple débridements, hardware removal, and, eventually, suppressive antibiotics; and 1 had cauda equina syndrome (caused by extensive scar tissue on the dura, which buckled with restoration of lordosis leading to cord compression), treated with duraplasty, which resulted in full neurologic recovery.

Discussion

In the present series of patients, the described technique for facilitating PSO for correction of sagittal imbalance was effective, and complications were similar to those previously reported.

The benefit of the outrigger construct is that it allows controlled compression of the osteotomy site and can be left in place at time of final instrumentation, locking in compression and correction. Other techniques involve removing the temporary rod and replacing it with final instrumentation4,5—an extra step that complicates instrumentation of the additional levels of the fusion construct and possibly adds pedicle screw stress and contributes to loosening when the new rod is reduced to the pedicle screw. The final long rod construct can bypass the osteotomy levels and allow for simpler instrumentation.

Mean age was 58 years in this series versus 52.4 years in the series reported by Bridwell and colleagues.2 Given the higher mean age of our patients, though no objective measures of bone quality were available, this technique is likely applicable to patients with poor bone quality.

The complications we have reported are in line with those reported in previous series, and maintenance of radiographic parameters at final follow-up indicates that this osteotomy technique allows for solid fusion constructs.

The outrigger technique for controlling PSO closure is an effective method that simplifies instrumentation during a complex revision case.

Pedicle subtraction osteotomies (PSOs) have been used in the treatment of multiple spinal conditions involving a fixed sagittal imbalance, such as degenerative scoliosis, idiopathic scoliosis, posttraumatic deformities, iatrogenic flatback syndrome, and ankylosing spondylitis. The procedure was first described by Thomasen1 for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. More recently, multiple centers have reported the expanded use and good success of PSO in the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance of other etiologies.2,3 According to Bridwell and colleagues,2 lumbar lordosis can be increased 34.1°, and sagittal plumb line can be improved 13.5 cm.

PSO is a complex, extensive surgery most often performed in the revision setting. Multiple authors have described the technique for PSO.4,5 There are significant technical challenges and many complications, including neurologic deficits, pseudarthrosis of adjacent levels, and wound infections.6 Short-term challenges include a large loss of blood, 2.4 L on average, according to Bridwell and colleagues.6 Time of closure of the osteotomy gap is a crucial point in the surgery. Blood loss, often large, slows only after the gap is closed and stabilized.

In this article, we describe a technique in which an additional rod or pedicle screw construct is used at the periosteotomy levels to close the osteotomy gap during PSO and simplify subsequent instrumentation. In addition, we report our experience with the procedure.

Materials and Methods

Seventeen consecutive patients (mean age, 58 years; range, 12-81 years) with fixed sagittal imbalance were treated with lumbar PSO. The indication in all cases was flatback syndrome after previous spinal surgery. Mean follow-up was 13 months. Mean number of prior surgeries was 3. Thirteen PSOs were performed at L3, and 4 were performed at L2.

Radiographic data were collected from before surgery, in the immediate postoperative period, and at final follow-up. All the radiographs were standing films. Established radiographic parameters were measured: thoracic kyphosis from T5 to T12, lumbar lordosis from L1 to S1, PSO angle (1 level above to 1 level below osteotomy level), sagittal plumb line (from center of C7 body to posterosuperior aspect of S1 body), and coronal plumb line (from center of C7 body to center of S1 body).2

Good clinical outcomes in the treatment of spinal disorders require careful attention to the alignment of the spine in the sagittal plane.7,8 When evaluating the preoperative radiographs, we measured and documented pelvic parameters. Figure 1A shows how pelvic incidence was determined. We measured this as the angle between a line drawn from the center of the S1 endplate to the center of the femoral head and the perpendicular off the S1 endplate. Figure 1B shows pelvic tilt as determined by the angle between a line drawn from the center of S1 to the femoral head and a vertical line originating from the center of the femoral head. Figure 1C shows the sacral slope, which we measured as the angle between a line drawn parallel to the endplate of S1 and its intersection with a horizontal line.

Surgical Technique

The overall surgical technique for PSO has been well described.4,5 Here we describe the “outrigger” modification to osteotomy closure (Figures 2, 3).

Most of our 17 cases were revisions. In these cases, new fixation points are first established. All fixation points that will be needed for the final fusion are placed. If a pedicle above or below the osteotomy level is not suitable for a screw, it can be skipped.

Wide decompression of the involved level is performed from pedicle to pedicle, ensuring that the nerve roots are completely decompressed. The dissection is then continued around the lateral wall of the vertebral body. While the neural elements are protected with gentle retraction, the pedicle and a portion of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body are removed with a combination of a rongeur and reverse-angle curettes. Resection of the vertebral body can be facilitated by attaching a short rod to the pedicle screws on either side of the osteotomy level and using it to provide gentle distraction.

Once sufficient bone has been removed to close the osteotomy, short rods are placed in the pedicle screws in the level above and the level below the osteotomy site. These rods are attached with offset connectors that allow the rods to be placed lateral to the screws. Before the surgical procedure is started, the patient is positioned on 2 sets of posts separated by the break in the table. The break in the table allows flexion to accommodate the preoperative kyphosis and allows hyperextension to help close the osteotomy site. Now, with the osteotomy site ready for closure, the table is gradually positioned in extension along with a combination of posterior pressure and compression between the pedicle screws above and below the osteotomy. Once the osteotomy is adequately compressed, the short rods are tightened, holding the osteotomy in good position. With the osteotomy held by the short rods and table positioning, decompression of the neural elements is confirmed and hemostasis obtained.

Final instrumentation is then performed with long rods that can bypass the osteotomized levels, allowing for simpler contouring. If desired, a cross connector can be placed between the long rod of the fusion construct and the short rod holding the osteotomy. The rest of the fusion procedure is completed in standard fashion with at least 1 subfascial drain.

Results

Our 17 patients’ results are summarized in the Table. Mean sagittal plumb line improved from 17.7 cm (range, 5.9 to 29 cm) before surgery to 4.5 cm (range, –0.2 to 12.9 cm) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 13.2 cm. At final follow-up, mean sagittal plumb line was 5.1 cm (range, –1.4 to 10.2 cm).

Mean lumbar lordosis improved from 10° (range, –14° to 34°) before surgery to 49° (range, 36° to 63°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 39°. Mean PSO angle improved from 3° (range, –36° to 23°) before surgery to 41° (range, 25° to 65°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 38°. At final follow-up, mean lumbar lordosis remained at 47° (range, 26° to 64°), and mean PSO angle was 39° (range, 24° to 59°).

Mean thoracic kyphosis improved from 18° (range, –8° to 52°) before surgery to 30° (range, 3° to 58°) after surgery, for a mean improvement of 12°. At final follow-up, mean thoracic kyphosis was 31° (range, 2° to 57°).

Fourteen patients did not have complications during the study period. Of the 3 patients with complications, 1 had an early infection, treated effectively with irrigation and débridement and intravenous antibiotics; 1 had a late deep infection, treated with multiple débridements, hardware removal, and, eventually, suppressive antibiotics; and 1 had cauda equina syndrome (caused by extensive scar tissue on the dura, which buckled with restoration of lordosis leading to cord compression), treated with duraplasty, which resulted in full neurologic recovery.

Discussion

In the present series of patients, the described technique for facilitating PSO for correction of sagittal imbalance was effective, and complications were similar to those previously reported.

The benefit of the outrigger construct is that it allows controlled compression of the osteotomy site and can be left in place at time of final instrumentation, locking in compression and correction. Other techniques involve removing the temporary rod and replacing it with final instrumentation4,5—an extra step that complicates instrumentation of the additional levels of the fusion construct and possibly adds pedicle screw stress and contributes to loosening when the new rod is reduced to the pedicle screw. The final long rod construct can bypass the osteotomy levels and allow for simpler instrumentation.

Mean age was 58 years in this series versus 52.4 years in the series reported by Bridwell and colleagues.2 Given the higher mean age of our patients, though no objective measures of bone quality were available, this technique is likely applicable to patients with poor bone quality.

The complications we have reported are in line with those reported in previous series, and maintenance of radiographic parameters at final follow-up indicates that this osteotomy technique allows for solid fusion constructs.

The outrigger technique for controlling PSO closure is an effective method that simplifies instrumentation during a complex revision case.

1. Thomasen E. Vertebral osteotomy for correction of kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop. 1985;(194):142-152.

2. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(3):454-463.

3. Berven SH, Deviren V, Smith JA, Emami A, Hu SS, Bradford DS. Management of fixed sagittal plane deformity: results of the transpedicular wedge resection osteotomy. Spine. 2001;26(18):2036-2043.

4. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Rinella A, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):44-50.

5. Wang MY, Berven SH. Lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2 suppl 1):ONS140-ONS146.

6. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Edwards C, et al. Complications and outcomes of pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine. 2003;28(18):2093-2101.

7. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):260-267.

8. Schwab F, Lafage V, Patel A, Farcy JP. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adult patient. Spine. 2009;34(17):1828-1833.

1. Thomasen E. Vertebral osteotomy for correction of kyphosis in ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Orthop. 1985;(194):142-152.

2. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(3):454-463.

3. Berven SH, Deviren V, Smith JA, Emami A, Hu SS, Bradford DS. Management of fixed sagittal plane deformity: results of the transpedicular wedge resection osteotomy. Spine. 2001;26(18):2036-2043.

4. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Rinella A, Lenke LG, Baldus C, Blanke K. Pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the treatment of fixed sagittal imbalance. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 1):44-50.

5. Wang MY, Berven SH. Lumbar pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(2 suppl 1):ONS140-ONS146.

6. Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, Edwards C, et al. Complications and outcomes of pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine. 2003;28(18):2093-2101.

7. Vialle R, Levassor N, Rillardon L, Templier A, Skalli W, Guigui P. Radiographic analysis of the sagittal alignment and balance of the spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):260-267.

8. Schwab F, Lafage V, Patel A, Farcy JP. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adult patient. Spine. 2009;34(17):1828-1833.