User login

Waxy fingers and skin tethering

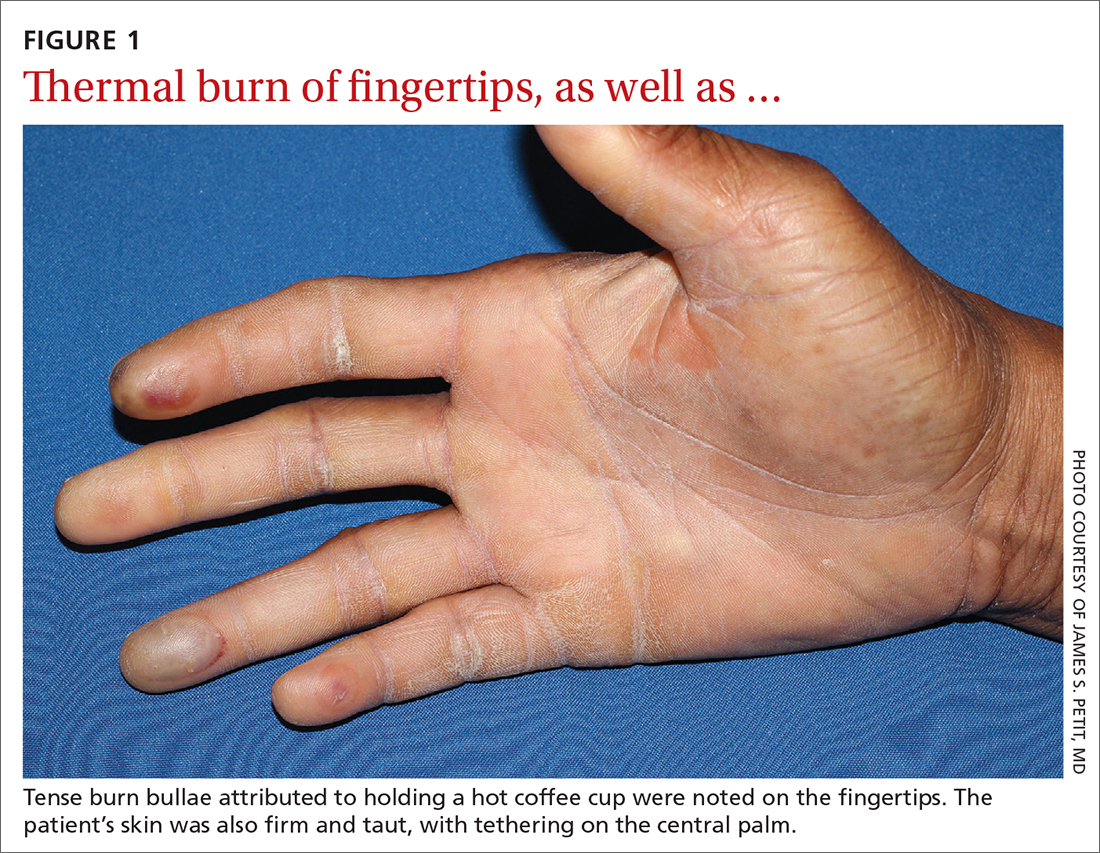

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

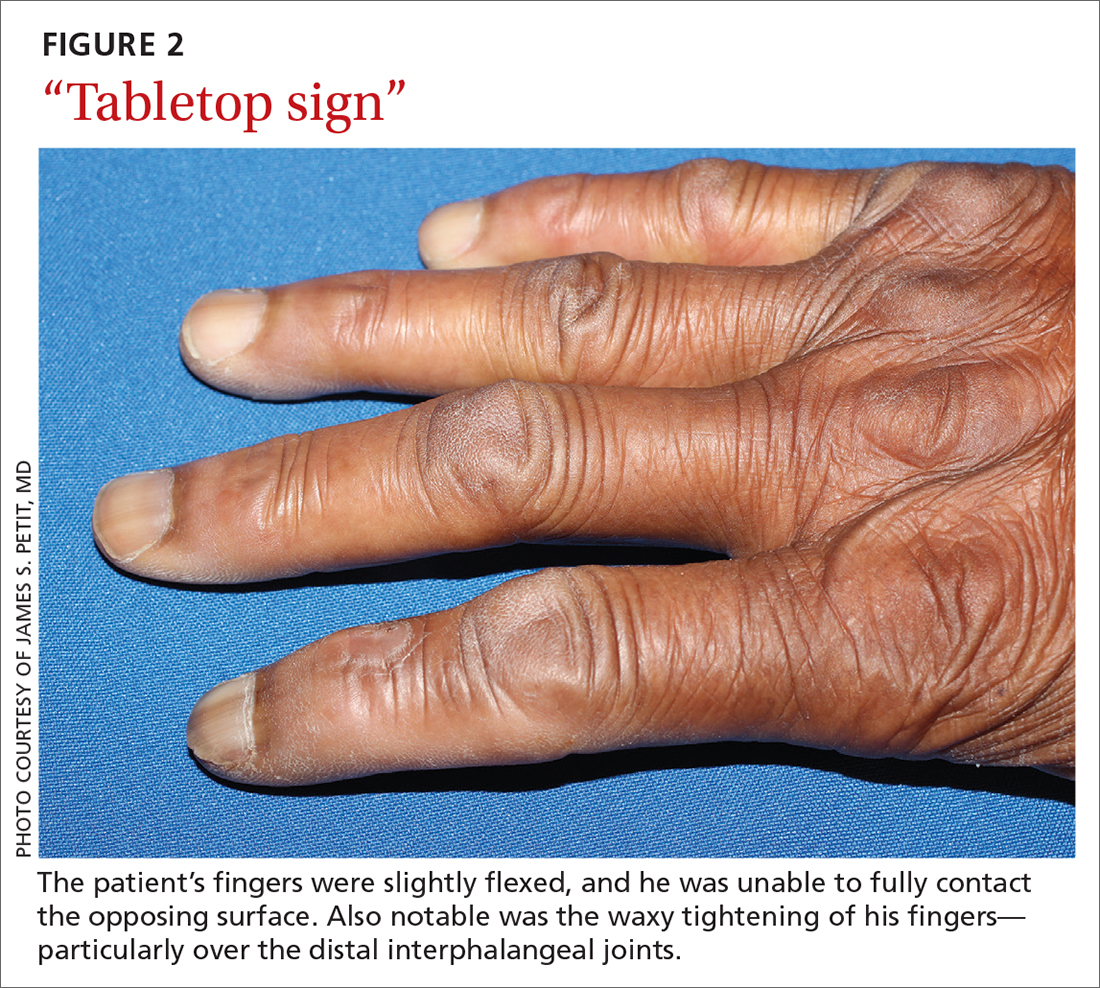

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

A 73-year-old man with longstanding, poorly controlled type 1 diabetes (T1D) and worsening paresthesia presented to the dermatology clinic following a painless thermal burn of his fingertips from holding a hot cup of coffee. The patient’s paresthesia in a stocking-and-glove distribution was attributable to diabetes-associated polyneuropathy. Two years prior, he had been diagnosed with mildly symptomatic, diabetes-associated scleredema of his upper back and treated with topical corticosteroids.

Physical examination revealed tense bullae on the pads of all 5 digits of his right hand (FIGURE 1). Localized, waxy tightening of the skin was noted on all digits of both hands, along with mild tethering of thickened skin on the right palm.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Diabetic hand syndrome

Subtle, early signs of diabetic sclerodactyly and Dupuytren contracture (DC) were observed in the context of an existing diagnosis of T1D, leading to a diagnosis of diabetic hand syndrome.

Sclerodactyly, a thickening and tightening of the skin, is a characteristic component of limited and systemic sclerosis. Sclerodactyly is not commonly observed in association with type 1 and type 2 diabetes; however, when it does occur, it is typically found in patients who have had uncontrolled diabetes for some time.1-3 (In the context of diabetes, this skin manifestation is known as pseudoscleroderma and scleredema diabeticorum.) In 1 study of 238 patients with T1D, the prevalence of this diabetes manifestation was 39%, with a range of 10% to 50% also reported.3

Diabetic hand syndrome is an umbrella term for the constellation of debilitating fibroproliferative sequelae of the hand rendered by diabetes.3 In addition to diabetic sclerodactyly, diabetic hand syndrome includes limited joint mobility (LJM), or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, which typically manifests with either the “prayer sign” (the inability of the palms to obtain full approximation while the wrists are maximally flexed) or the “tabletop sign” (the inability of the palm to flatten completely against the surface of a table) (FIGURE 2).4,5 The prevalence of LJM has been reported to range from 8% to 50% of patients diagnosed with longstanding, uncontrolled diabetes.4

Other musculoskeletal abnormalities seen in this syndrome include: DC, often found clinically as a palpable palmar nodule that ultimately results in a flexion contracture of the affected finger; stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, in which a reproducible locking phenomenon occurs on flexion of a finger, typically in the first, third, and fourth digits; and carpal tunnel syndrome, a median nerve entrapment neuropathy that results in pain and/or paresthesia over the thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of the ring fingers.3-5

Secondary symptoms can signal long-term degenerative disease

Stocking-and-glove distribution polyneuropathy with deterioration of tactile sensation is a common sequela of diabetes, especially as disease severity progresses.2 Although the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, it has been proposed that both diabetic polyneuropathy and increased skin thickness occur secondary to long-term degenerative microvascular disease.

Continue to: Specifically, prolonged...

Specifically, prolonged hyperglycemia and secondary chronic inflammation set the stage for protein glycation, with formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). It is thought that these AGEs in cutaneous and connective tissues stiffen collagen, leading to scleroderma-like skin changes.2

These microvascular and fibroproliferative changes are also considered important contributors in the etiology of DC and trigger finger, ultimately leading to increased collagen deposition and fascial thickening.4,5 In addition, increased activation of the polyol pathway may occur secondary to hyperglycemia, resulting in increased intracellular water and cellular edema.5

The differential is comprisedof components of systemic disease

The differential diagnosis includes tropical diabetic hand, autoimmune-related scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis), complex regional pain syndrome, and diabetic scleredema.

Tropical diabetic hand, a potentially dangerous infection, is generally found only in tropical regions and in the setting of injury.5,6

Autoimmune-related scleroderma may be diagnosed alongside other signs and symptoms of CREST: calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. In the absence of other signs and symptoms, and in the presence of uncontrolled diabetes, biopsy would be needed to definitively diagnose it. Clinically, diabetic hand can be distinguished with concurrent involvement of the upper back.

Continue to: Complex regional pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome is characterized by chronic, disabling pain, swelling, and motor impairment that frequently affect the hand, often secondary to surgery or trauma.5,7 This diagnosis differs from the generally painless skin hardening of diabetic hand.

The co-existence of diabetic scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly has been previously reported, although the onset of each condition is often temporally distinct.8 In contrast to diabetic sclerodactyly, the firm indurated skin characteristic of diabetic scleredema (which our patient had) initially involves the shoulders and neck and may progress over the trunk, including the upper back, typically sparing the distal extremities. Of note, the dermis in scleredema is thickened with marked deposition of mucopolysaccharide.9

Glycemic control is paramount

Studies of patients with diabetes who have thick, waxy skin and LJM have shown that tight glycemic control may reduce skin thickness and palmar fascia fibrosis.3,5,9 Thus, in this patient with poorly controlled T1D, diabetic sclerodactyly, early DC, and second-degree burns attributable to advanced polyneuropathy, tightened glycemic control is logical and warranted. Such control could potentially impact the trajectory and morbidity of skin and musculoskeletal manifestations in this broad-reaching disease.

Although there are limited treatments for mobility-related symptoms of diabetic hand syndrome, physiotherapy is recommended in more severe stages of disease to increase joint range of motion.4,5 More severe cases of DC and trigger finger have been successfully treated with topical steroids, corticosteroid injections, and surgery.4,5 Simply stated—and in line with compulsive foot care—the diabetic milieu necessitates clinicians’ close attention to the hands. Components of diabetic hand, LJM, DC, or trigger finger may indicate a need to screen not only for diabetes in a patient previously undiagnosed but also, importantly, for other sequelae of diabetes, including retinopathy.4,5

Our patient was treated with a moderate-potency topical steroid, triamcinolone 0.1% cream, and was advised to continue optimizing glycemic control with the aid of his primary care physician. It was unclear whether the patient improved with use, as he was lost to follow-up.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

1. Yosipovitch G, Hodak E, Vardi P, et al. The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in IDDM patients and their association with diabetes risk factors and microvascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:506-509. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.506

2. Redmond CL, Bain GI, Laslett LL, et al. Deteriorating tactile sensation in patients with hand syndromes associated with diabetes: a two-year observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:313-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2012.04.009

3. Rosen J, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of diabetes mellitus. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al, eds. Endotext. 2018. South Dartmouth, MA. Accessed November 30, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/

4. Goyal A, Tiwari V, Gupta Y. Diabetic hand: a neglected complication of diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2018;10:e2772. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2772

5. Papanas N, Maltezos E. The diabetic hand: a forgotten complication? J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:154-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.12.009

6. Gill GV, Famuyiwa OO, Rolfe M, et al. Tropical diabetic hand syndrome. Lancet. 1998;351:113-114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78146-0

7. Goh EL, Chidambaram S, Ma D. Complex regional pain syndrome: a recent update. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:2. doi: 10.1186/s41038-016-0066-4

8. Gruson LM, Franks A Jr. Scleredema and diabetic sclerodactyly. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:3.

9. Shazzad MN, Azad AK, Abdal SJ, et al. Scleredema diabeticorum – a case report. Mymensingh Med J. 2015;24:606-609.

Locus Minoris Resistentiae: Mycobacterium chelonae in Striae Distensae

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

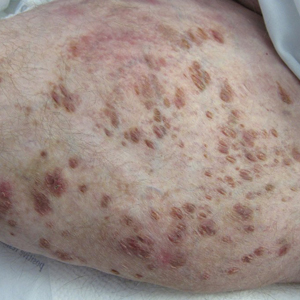

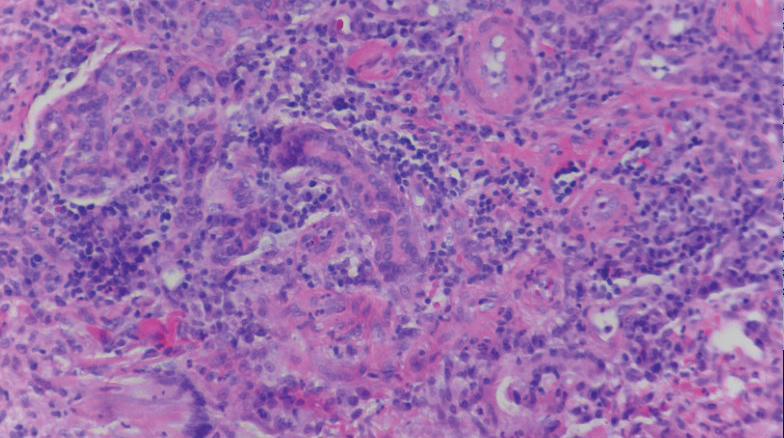

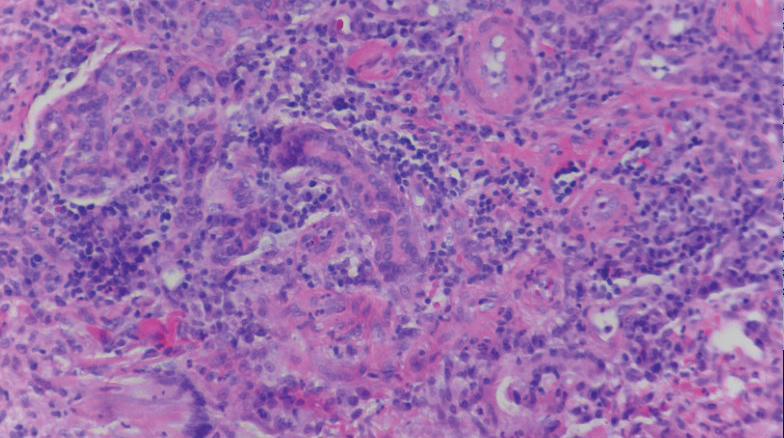

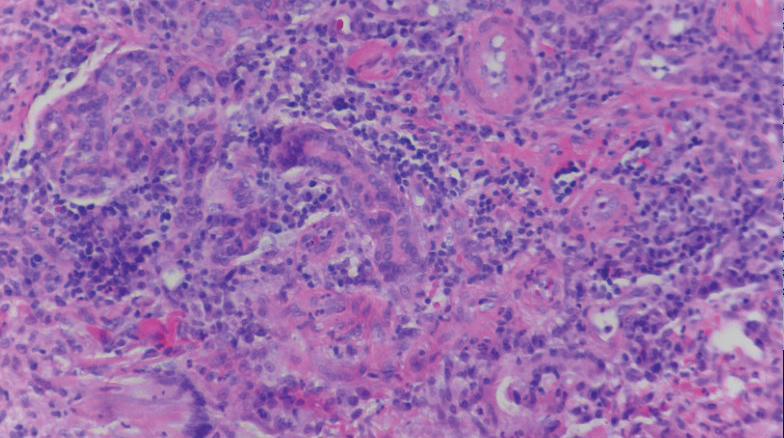

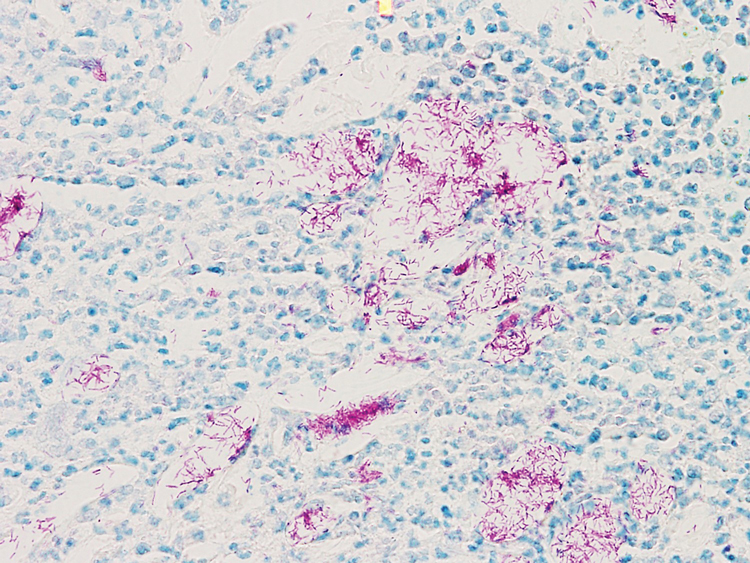

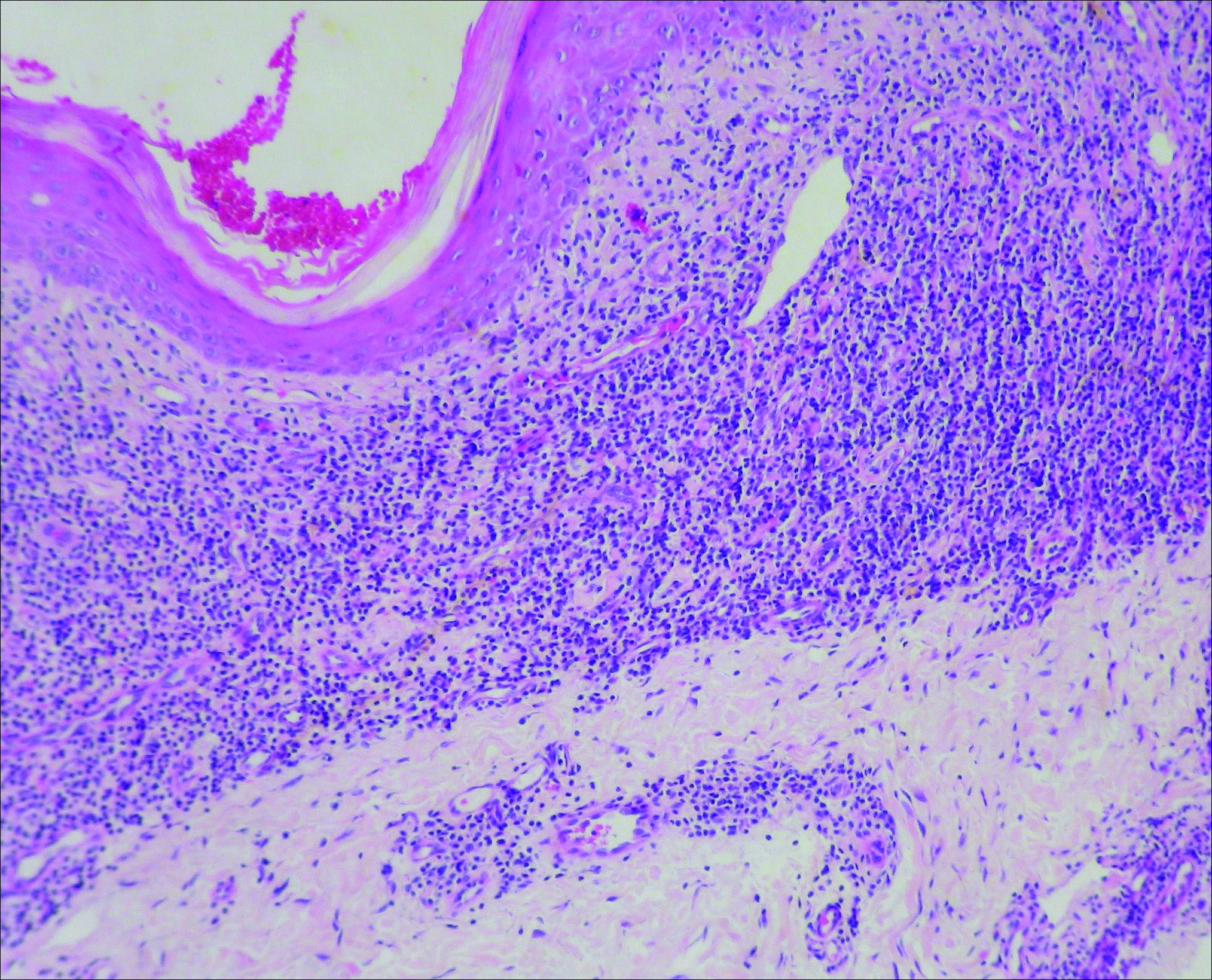

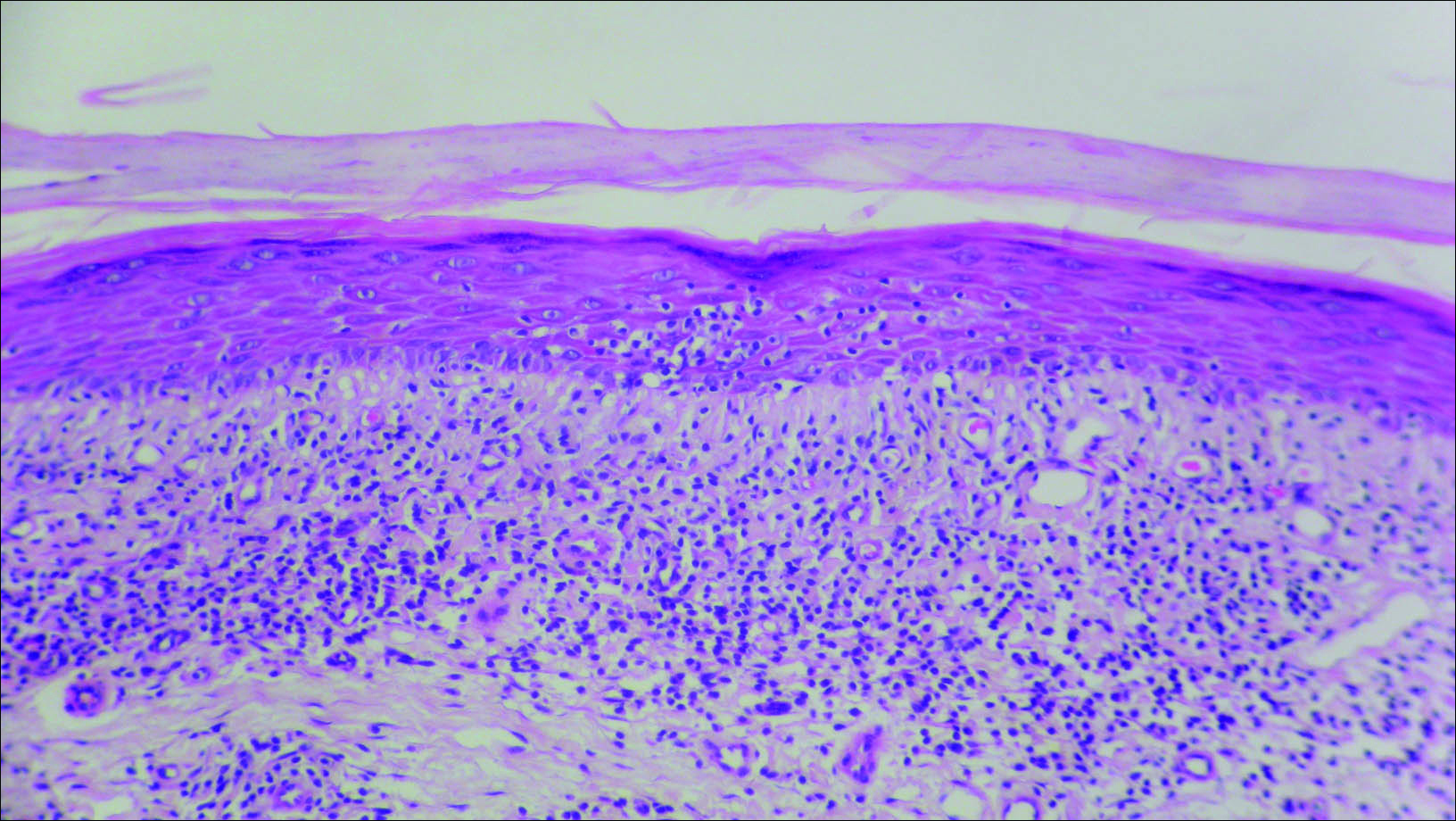

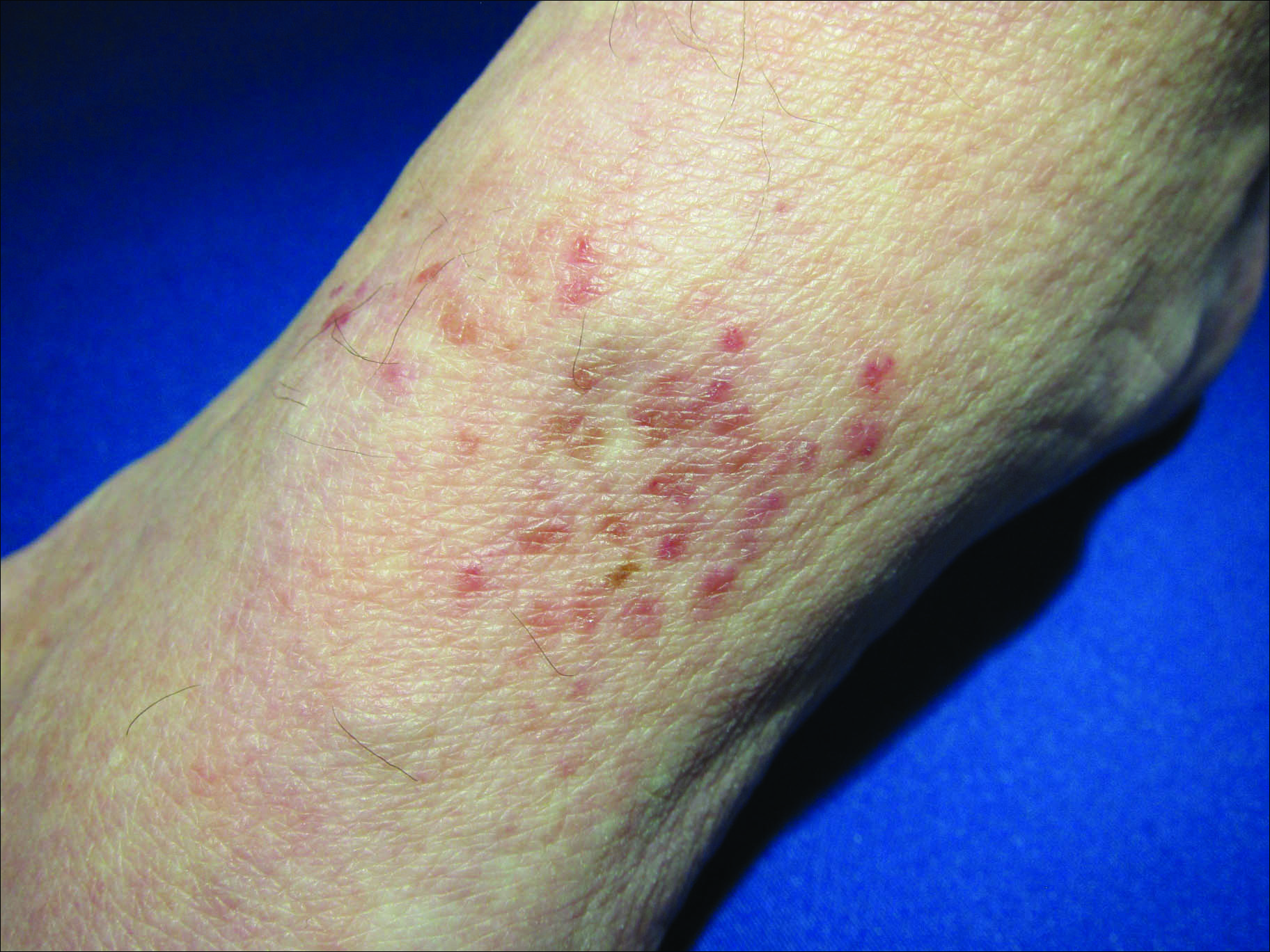

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

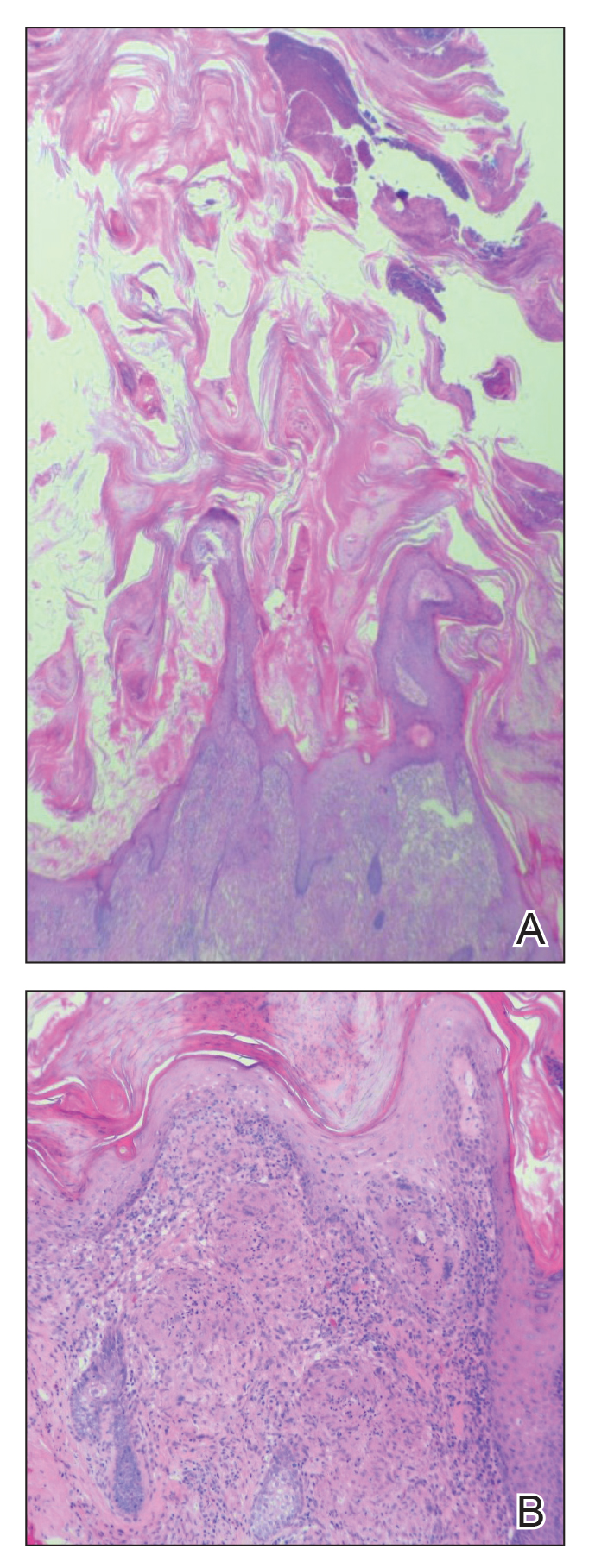

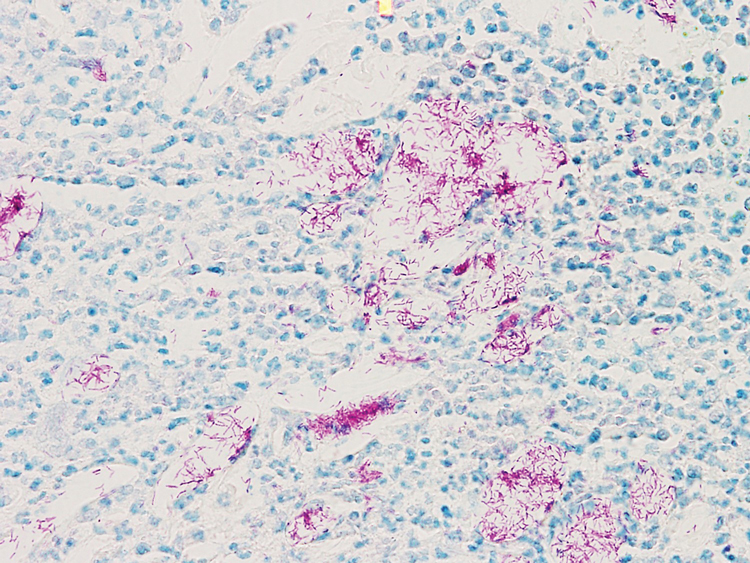

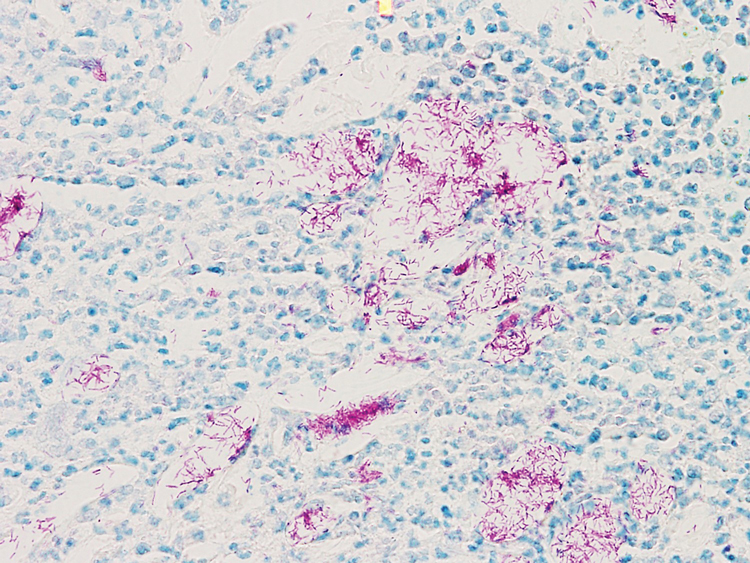

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

To the Editor:

Immunosuppressed patients are at particular risk for disseminated mycobacterial infections. A locus minoris resistentiae offers less resistance to the infectious spread of these microorganisms. We present a case of Mycobacterium chelonae infection preferentially involving striae distensae.

A 30-year-old man with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia requiring high-dose corticosteroid therapy presented with widespread skin lesions. He reported no history of cutaneous trauma or aquatic activities. Physical examination revealed the patient was markedly cushingoid with generalized cutaneous atrophy and widespread striae. Multiple erythematous papules surrounded a large ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the left hand. Depressed erythematous plaques and several small crusted erosions extended up the left lower leg (Figure 1) to the knee. Strikingly, numerous brown and pink papules and small plaques on the left thigh were primarily confined within striae (Figure 2).

A biopsy of the left thigh revealed granulomatous inflammation (Figure 3) with numerous acid-fast bacilli (Figure 4). Broad-spectrum coverage for fast-growing acid-fast bacilli with amikacin, ceftriaxone, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin was initiated with steady improvement of the eruption. Tissue culture subsequently grew Mycobacterium abscessus-chelonae, and therapy was narrowed to clarithromycin and moxifloxacin.

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated from soil and water worldwide, and human skin is a commensal organism. Cutaneous infections have been associated with traumatic injury, tattooing, surgery, cosmetic procedures, vascular access sites, and acupuncture.1 Most cases of cutaneous M chelonae infection begin as a violaceous nodule. Over weeks to months, the localized infection progresses to multiple papules, nodules, draining abscesses, or ulcers. Infections tend to disseminate in immunosuppressed patients, and granulomatous inflammation may not be seen.1

Atypical mycobacterial infection occurring within striae distensae is an example of locus minoris resistentiae—a place of less resistance. Wolf et al2 hypothesized that locus minoris resistentiae could explain the occurrence of an isotopic response or the occurrence of a new skin disorder at the site of a previously healed skin condition. They suggested that the same site could be affected by 2 unrelated diseases at different times due to an inherited or acquired susceptibility in the area.2 Herpes zoster serves as a primary example of Wolf phenomenon, as numerous conditions including granuloma annulare, pseudolymphoma, Bowen disease, and acne have reportedly emerged in its wake.3

Although locus minoris resistentiae does not specifically involve traumatized skin, it must be distinguished from the Koebner phenomenon, characterized by the appearance of isomorphic lesions in areas of otherwise healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury, as well as the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon, a similar process involving infectious agents.3

In our patient, striae distensae represented areas of increased predisposition to infection. The catabolic effect of high corticosteroid levels on fibroblast activity decreased collagen deposition in the dermal matrix, leading to the formation of linear bands of atrophic skin.4 The elastic fiber network in striae distensae is reduced and reorganized compared to normal skin, in which an intertwining elastic system forms a continuum from the dermoepidermal junction to the deep dermis.5 The number of vertically oriented fibrillin microfibrils subjacent to the dermoepidermal junction and elastin fibers in the papillary dermis is comparatively diminished such that the elastin and fibrillin fibers in the deep dermis run more horizontally compared to normal skin.4 Consequently, collagen alignment in striae distensae demonstrates more anisotropy, or directionally dependent variability, and the dermal matrix is looser and more floccular than the surrounding skin.6 These alterations of dermal architecture likely provide a mechanical advantage for intradermal spread of M chelonae within striae.

Other dermatoses have been observed to occur within striae distensae, specifically leukemia cutis, urticarial vasculitis, lupus erythematosus, keloids, linear focal elastosis, chronic graft-vs-host disease, psoriasis, gestational pemphigoid, and vitiligo.7 Given the dissimilarities of these conditions, the distinctive milieu of striae must provide an invitation—a locus minoris resistentiae—for secondary pathology.

Chronic corticosteroid use leads to both immunosuppression and striae distensae, effectively creating a perfect storm for an atypical mycobacterial skin infection demonstrating locus minoris resistentiae. The immunosuppressed state makes patients more susceptible to infection, and striae distensae may serve as a conduit for the offending organisms.

Acknowledgments—We are indebted to Letty Peterson, MD (Vidalia, Georgia), for her referral of this case, and to Stephen Mullins, MD (Augusta, Georgia), for his dermatopathology services.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Hay RJ. Mycobacterium chelonae—a growing problem in soft tissue infection. Cur Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:99-101.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Medeiros do Santos Camargo C, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, et al. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:741-749.

- Watson REB, Parry EJ, Humphries JD, et al. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931-397.

- Bertin C, A Lopes-DaCunha, Nkengne A, et al. Striae distensae are characterized by distinct microstructural features as measured by non-invasive methods in vivo. Skin Res Technol. 2014;20:81-86.

- Elsaie ML, Baumann LS, Elsaaiee LT. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563-573.

- Liu CI, Hsu CH. Leukemia cutis at the site of striae distensae: an isotopic response? Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

Practice Points

- Striae distensae, seen frequently in the setting of chronic corticosteroid use, are at an increased risk for localized infection, particularly in immunocompromised patients. There should be a low threshold to biopsy striae distensae that demonstrate morphologic evolution.

- The Koebner reaction, also known as an isomorphic response, refers to the appearance of certain dermatoses in previously healthy skin subjected to cutaneous injury.

- Locus minoris resistentiae is an isotropic response that characterizes the presentation of a new dermatosis within an area previously affected by an unrelated skin condition that has healed.

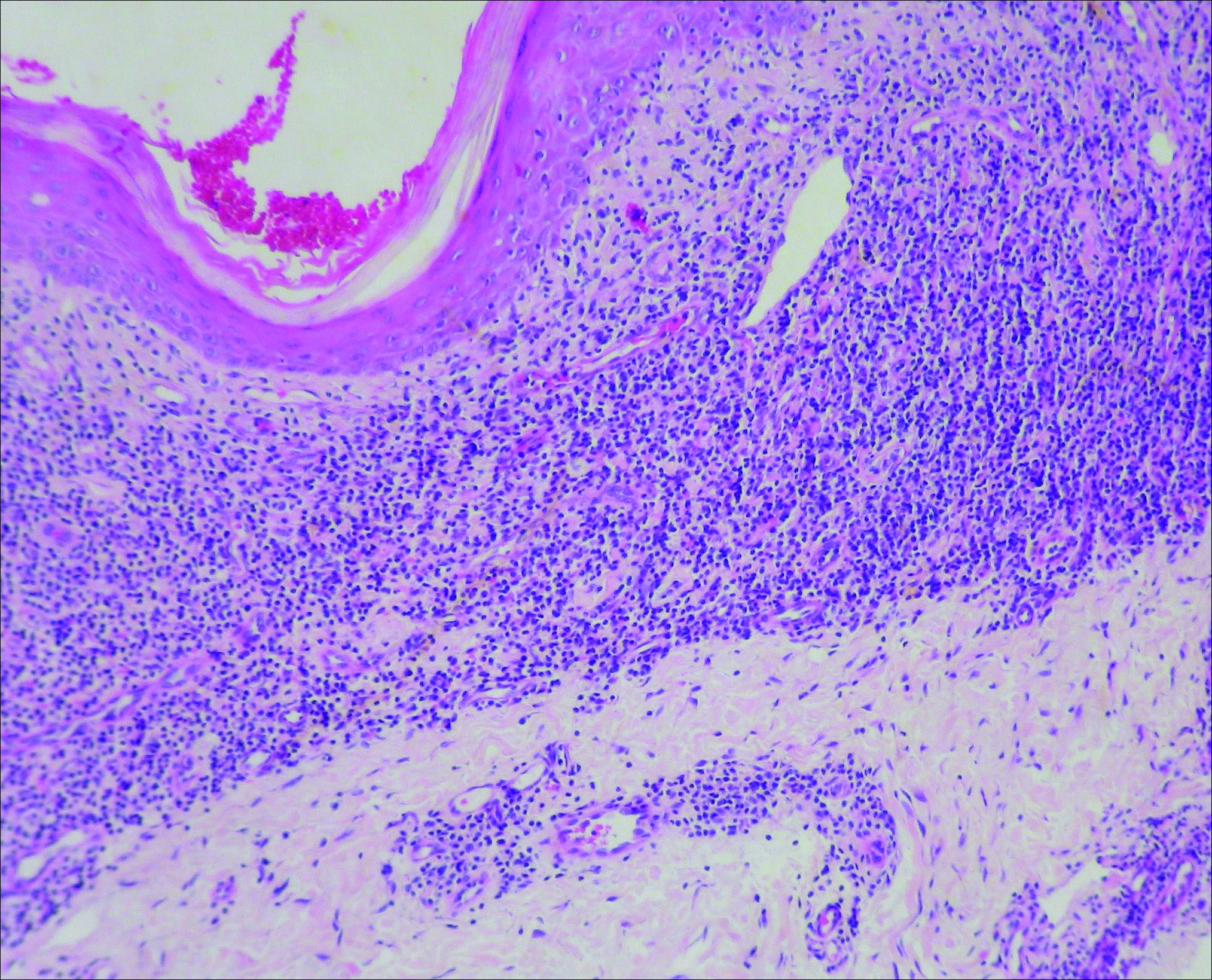

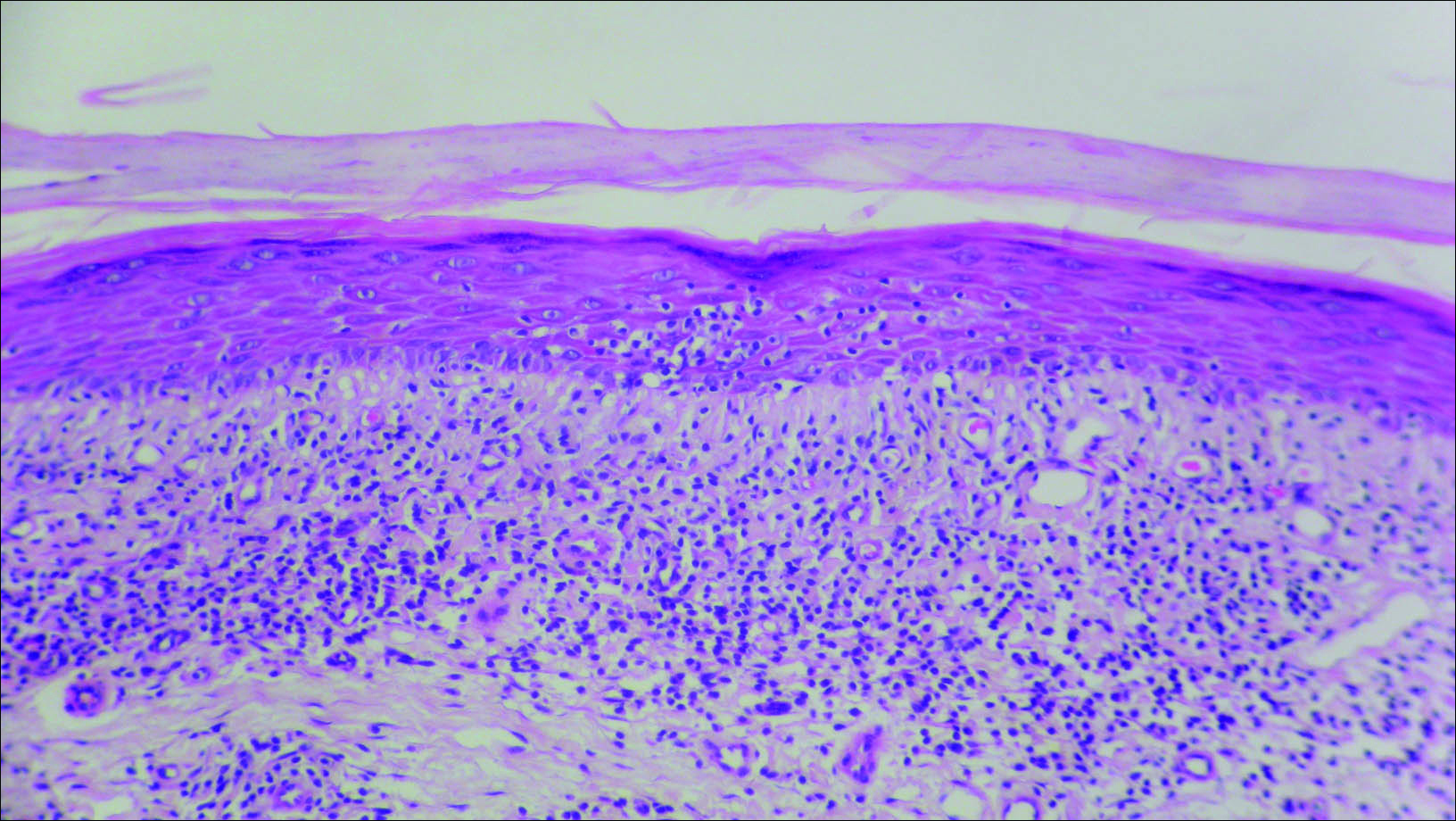

Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Presenting as a Cutaneous Horn

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

To the Editor:

A 53-year-old woman presented to our dermatology clinic with a painful growth on the right ear of 2 months’ duration. A complete review of systems was negative except for an isolated episode of shortness of breath prior to presentation that resolved without intervention. During this episode, her primary care physician made a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on a chest radiograph. The patient reported minimal tobacco use, specifically that she had smoked a few cigarettes daily for several years but had quit 6 months prior to the current presentation.

Cutaneous horn is a clinical term used to describe hyperkeratotic horn-shaped growths of highly variable shapes and sizes. Although the pathogenesis and incidence of cutaneous horns remain unknown, these lesions most often are the result of a neoplastic rather than an inflammatory process. The differential diagnosis typically includes entities characterized by marked hyperkeratosis, including hypertrophic actinic keratosis, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), seborrheic keratosis, and verruca vulgaris. The base of the horn must be biopsied to determine the underlying etiology, paying careful attention to avoid a superficial biopsy, as it may be nondiagnostic.

Studies analyzing the underlying diagnoses and clinical features of cutaneous horns are limited. In a large retrospective study of 643 cutaneous horns, 61% were benign, 23% were premalignant, and 16% were malignant. In this study, 4 features were associated with premalignant or malignant pathology: (1) older age (mid- 60s to 70s); (2) male sex; (3) location on the nose, pinnae, dorsal hands, scalp, forearms, or face; and (4) a wide base (4.4 mm or larger) and a lower height-to-base ratio than benign lesions.1 Two additional studies of more than 200 horns each showed higher rates of premalignant horns (42% and 38%, respectively) with malignancy found in 7% and 20% of horns, respectively.2,3 One prospective study sought to identify clinical and dermatoscopic features of SCCs underlying cutaneous horns, concluding that SCC diagnosis was more likely if a horn had (1) a height less than the diameter of its base, (2) a lack of terrace morphology (a dermatoscopic feature defined as horizontal parallel layers of keratin), (3) erythema at the base, and (4) the presence of pain.4

Our patient had a cutaneous horn on the pinna that was painful, wider than it was tall, and erythematous at the base, suggesting a malignant process; however, a complete cutaneous physical examination revealed other skin lesions that were concerning for sarcoidosis and raised suspicion that the horn also was a manifestation of the same inflammatory process.

Although unusual, cutaneous sarcoidosis presenting as a cutaneous horn is not unexpected. In a histopathologic study of 62 cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis, 79% (49/62) showed epidermal changes and 13% (8/62) demonstrated hyperkeratosis. Other epidermal changes included parakeratosis (16% [10/62]), acanthosis (10% [6/62]), and epidermal atrophy (57% [35/62]).5 The spectrum of epidermal pathology in cutaneous sarcoidosis is evident in its well-documented verrucous, psoriasiform, and ichthyosiform presentations. For completeness, cutaneous horn is added to the list of clinical morphologies for this “great imitator” of cutaneous diseases.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

- Yu RC, Pryce DW, Macfarlane AW, et al. A histopathological study of 643 cutaneous horns. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:449-452.

- Schosser RH, Hodge SJ, Gaba CR, et al. Cutaneous horns: a histopathologic study. South Med J. 1979;72:1129-1131.

- Mantese SA, Diogo PM, Rocha A, et al. Cutaneous horn: a retrospective histopathological study of 222 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:157-163.

- Pyne J, Sapkota D, Wong JC. Cutaneous horns: clues to invasive squamous cell carcinoma being present in the horn base. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3:3-7.

- Hiroyuki O. Epidermal changes in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:229-233.

Practice Points

- Biopsy of a cutaneous horn should be deep enough to capture the neoplastic or inflammatory process at the base of the lesion.

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis can present with variable morphologies including the epidermal changes of a cutaneous horn.

Acute Kwashiorkor in the Setting of Cerebral Palsy and Pancreatic Insufficiency

To the Editor:

Kwashiorkor, or protein-calorie malnutrition, is a common issue in developing countries subject to starvation. In economically advanced nations, however, kwashiorkor is extremely rare and may appear in children placed on restrictive diets instituted by well-meaning guardians. Kwashiorkor also may occur because of gastrointestinal malabsorption. We present a unique case of kwashiorkor that revealed an underlying diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency.

A 12-year-old girl presented to the hospital with 4 days of watery nonbloody diarrhea occurring with every feeding as well as new onset of presumed diaper dermatitis that had not responded to nystatin cream. Facial swelling also was noted the day prior to admission. Her medical history was notable for cerebral palsy secondary to nonaccidental trauma, leaving the patient nonverbal and quadriplegic. She had numerous prior admissions for sepsis with marked hypotension and more recently was diagnosed with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had never lived outside the United States and resided at home with her adoptive parents.

Physical examination revealed a nonverbal underweight girl (weight, 25 kg). Large areas of denudation with surrounding desquamated skin resembling flaking enamel paint covered the buttocks and posterior legs bilaterally (Figure). She had linear hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands with one superficial erosion on the left wrist. Marked periorbital edema as well as nonpitting edema of the face, arms, and legs were present.

Upon additional questioning, the patient’s adoptive parent reported a diet of formula containing 1.0 cal/mL with 200-mL feedings 3 times daily through a Geiger-Müller tube, providing a daily protein intake of approximately 17.7 g per day (0.7 g/kg per day). On the day of admission, abnormal laboratory findings included low protein and albumin levels at 4.6 g/dL (reference range, 5.7–8.2 g/dL) and 2.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.2–4.8 g/dL), respectively; an elevated aspartate aminotransferase level of 73 U/L (reference range, 10–34 U/L); and an elevated alanine aminotransferase level of 80 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Based on the patient’s characteristic clinical findings and abnormal laboratory values, a diagnosis of acute kwashiorkor was made. Although the zinc level was low at 0.29 µg/mL (reference range, 0.66–1.10 µg/mL), the patient did not have any periorificial involvement to support a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica.

Upon further workup, stool elastase was measured at less than 50 µg per gram of stool (reference range, >200 µg pancreatic elastase per gram of stool), confirming a diagnosis of severe pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic enzyme supplementation was initiated along with an increase in protein intake to 1.5 g/kg per day. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by respiratory distress and sepsis, leading to a prolonged hospital stay. A component of refeeding syndrome may have contributed to the patient’s respiratory distress.

Kwashiorkor, a form of protein malnutrition, is caused by inadequate protein intake and usually is seen in developing countries when children are weaned from breastmilk to a diet high in starch and low in protein. It is characterized by edema, growth retardation, a characteristic dermatosis, depigmentation of hair, lethargy, and irritability.1 If left untreated, kwashiorkor can be fatal. Skin changes associated with kwashiorkor first occur in areas of friction or pressure. The skin develops patches of hyperpigmentation that subsequently desquamate in a pattern likened to flaky paint. In the current case of a nonmobile child with diarrhea, prominent involvement of the buttocks and thighs would be expected. This dermatosis does not appear in marasmus and is pathognomonic for kwashiorkor when seen in a child with edema.2

Children in the United States developing kwashiorkor secondary to severely restrictive diets has been reported.3 However, kwashiorkor also may occur due to underlying chronic malabsorptive disease. There have been rare reports of children with cystic fibrosis presenting with kwashiorkor,4 as well as a case of kwashiorkor secondary to underlying infantile Crohn disease.5

Cerebral palsy is associated with multiple different risk factors for malnutrition. Musculoskeletal deformities, oral-motor difficulties, medication side effects, limited communication skills, compromised pulmonary status, and poor muscle tone can all contribute to energy and nutrient deprivation.6 A 2018 study including 728 children registered into the Bangladesh Cerebral Palsy Register between January 2015 and December 2016 demonstrated that more than two-thirds were underweight (70.0%) and stunted (73.1%) and that children with tri/quadriplegic cerebral palsy presented with the highest proportion of severe malnutrition.7 In another report (N=142), up to 85% of children with spastic quadriplegia had severe feeding problems,8 making this population particularly high risk for poor nutritional status.

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency is characterized by reduced secretion of amylase, lipase, and protease, and it may result in diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption of essential nutrients, and malnutrition. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency may occur in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, and cystic fibrosis. Our patient had numerous hospitalizations for sepsis marked by hypotension, and in the absence of more typical causes, we postulate that both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic damage resulted from prolonged hypotension. A sweat chloride test was not performed, as the patient had not experienced frequent pulmonary infections or other signs of cystic fibrosis.

According to a report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization/United Nations University (FAO/WHO/UNU), protein should provide at least 10% of the total caloric intake in a child.9 Although the adoptive parent approximated that our patient received 12% of her daily calories in the form of protein, the amount that she absorbed in the context of pancreatic insufficiency was undoubtedly much lower.

In this case, the diagnosis of kwashiorkor led to the discovery of underlying pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Low stool elastase confirmed the diagnosis. Because kwashiorkor is rare in developed countries, the classic signs and symptoms may go unrecognized, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and notable morbidity and mortality. New-onset edema and desquamative rash in a child, especially a child with cerebral palsy, should alert physicians to the possibility of acute kwashiorkor and prompt investigation into underlying medical issues that may have contributed to its development.

1. Trowell HC, Davies JN, Dean RF. Kwashiorkor. II. clinical picture, pathology, and differential diagnosis. Br Med J. 1952;2:798-801.

2. Latham MC. The dermatosis of kwashiorkor in young children. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:270-272.

3. Liu T, Howard RM, Mancini AJ, et al. Kwashiorkor in the United States: fad diets, perceived and true milk allergy, and nutritional ignorance. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:630-636.

4. Phillips RJ, Crock CM, Dillon MJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis presenting as kwashiorkor with florid skin rash. Arch Dis Childhood. 1993;69:446-448.

5. Al-Mubarak L, Al-Khenaizan S, Al Goufi T. Cutaneous presentation of kwashiorkor due to infantile Crohn’s disease. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:117-119.

6. Wittenbrook W. Nutritional assessment and intervention in cerebral palsy. Practical Gastroenterol. Feb 2011;92:16-32. http://www.practicalgastro.com/pdf/February11/WittenbrookArticle.pdf.

7. Jahan I, Muhit M, Karim T, et al. What makes children with cerebral palsy vulnerable to malnutrition? findings from the Bangladesh cerebral palsy register (BCPR)[published online April 16, 2018]. Disabil Rehabil. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1461260.

8. Stallings VA, Charney EB, Davies JC, et al. Nutrition-related growth failure of children with quadriplegic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1993;35:126-138.

9. World Health Organization. Energy and Protein Requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1985. Technical Report Series 724.

To the Editor:

Kwashiorkor, or protein-calorie malnutrition, is a common issue in developing countries subject to starvation. In economically advanced nations, however, kwashiorkor is extremely rare and may appear in children placed on restrictive diets instituted by well-meaning guardians. Kwashiorkor also may occur because of gastrointestinal malabsorption. We present a unique case of kwashiorkor that revealed an underlying diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency.

A 12-year-old girl presented to the hospital with 4 days of watery nonbloody diarrhea occurring with every feeding as well as new onset of presumed diaper dermatitis that had not responded to nystatin cream. Facial swelling also was noted the day prior to admission. Her medical history was notable for cerebral palsy secondary to nonaccidental trauma, leaving the patient nonverbal and quadriplegic. She had numerous prior admissions for sepsis with marked hypotension and more recently was diagnosed with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had never lived outside the United States and resided at home with her adoptive parents.

Physical examination revealed a nonverbal underweight girl (weight, 25 kg). Large areas of denudation with surrounding desquamated skin resembling flaking enamel paint covered the buttocks and posterior legs bilaterally (Figure). She had linear hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands with one superficial erosion on the left wrist. Marked periorbital edema as well as nonpitting edema of the face, arms, and legs were present.

Upon additional questioning, the patient’s adoptive parent reported a diet of formula containing 1.0 cal/mL with 200-mL feedings 3 times daily through a Geiger-Müller tube, providing a daily protein intake of approximately 17.7 g per day (0.7 g/kg per day). On the day of admission, abnormal laboratory findings included low protein and albumin levels at 4.6 g/dL (reference range, 5.7–8.2 g/dL) and 2.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.2–4.8 g/dL), respectively; an elevated aspartate aminotransferase level of 73 U/L (reference range, 10–34 U/L); and an elevated alanine aminotransferase level of 80 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Based on the patient’s characteristic clinical findings and abnormal laboratory values, a diagnosis of acute kwashiorkor was made. Although the zinc level was low at 0.29 µg/mL (reference range, 0.66–1.10 µg/mL), the patient did not have any periorificial involvement to support a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica.

Upon further workup, stool elastase was measured at less than 50 µg per gram of stool (reference range, >200 µg pancreatic elastase per gram of stool), confirming a diagnosis of severe pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic enzyme supplementation was initiated along with an increase in protein intake to 1.5 g/kg per day. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by respiratory distress and sepsis, leading to a prolonged hospital stay. A component of refeeding syndrome may have contributed to the patient’s respiratory distress.

Kwashiorkor, a form of protein malnutrition, is caused by inadequate protein intake and usually is seen in developing countries when children are weaned from breastmilk to a diet high in starch and low in protein. It is characterized by edema, growth retardation, a characteristic dermatosis, depigmentation of hair, lethargy, and irritability.1 If left untreated, kwashiorkor can be fatal. Skin changes associated with kwashiorkor first occur in areas of friction or pressure. The skin develops patches of hyperpigmentation that subsequently desquamate in a pattern likened to flaky paint. In the current case of a nonmobile child with diarrhea, prominent involvement of the buttocks and thighs would be expected. This dermatosis does not appear in marasmus and is pathognomonic for kwashiorkor when seen in a child with edema.2

Children in the United States developing kwashiorkor secondary to severely restrictive diets has been reported.3 However, kwashiorkor also may occur due to underlying chronic malabsorptive disease. There have been rare reports of children with cystic fibrosis presenting with kwashiorkor,4 as well as a case of kwashiorkor secondary to underlying infantile Crohn disease.5

Cerebral palsy is associated with multiple different risk factors for malnutrition. Musculoskeletal deformities, oral-motor difficulties, medication side effects, limited communication skills, compromised pulmonary status, and poor muscle tone can all contribute to energy and nutrient deprivation.6 A 2018 study including 728 children registered into the Bangladesh Cerebral Palsy Register between January 2015 and December 2016 demonstrated that more than two-thirds were underweight (70.0%) and stunted (73.1%) and that children with tri/quadriplegic cerebral palsy presented with the highest proportion of severe malnutrition.7 In another report (N=142), up to 85% of children with spastic quadriplegia had severe feeding problems,8 making this population particularly high risk for poor nutritional status.

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency is characterized by reduced secretion of amylase, lipase, and protease, and it may result in diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption of essential nutrients, and malnutrition. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency may occur in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, and cystic fibrosis. Our patient had numerous hospitalizations for sepsis marked by hypotension, and in the absence of more typical causes, we postulate that both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic damage resulted from prolonged hypotension. A sweat chloride test was not performed, as the patient had not experienced frequent pulmonary infections or other signs of cystic fibrosis.

According to a report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization/United Nations University (FAO/WHO/UNU), protein should provide at least 10% of the total caloric intake in a child.9 Although the adoptive parent approximated that our patient received 12% of her daily calories in the form of protein, the amount that she absorbed in the context of pancreatic insufficiency was undoubtedly much lower.

In this case, the diagnosis of kwashiorkor led to the discovery of underlying pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. Low stool elastase confirmed the diagnosis. Because kwashiorkor is rare in developed countries, the classic signs and symptoms may go unrecognized, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and notable morbidity and mortality. New-onset edema and desquamative rash in a child, especially a child with cerebral palsy, should alert physicians to the possibility of acute kwashiorkor and prompt investigation into underlying medical issues that may have contributed to its development.

To the Editor:

Kwashiorkor, or protein-calorie malnutrition, is a common issue in developing countries subject to starvation. In economically advanced nations, however, kwashiorkor is extremely rare and may appear in children placed on restrictive diets instituted by well-meaning guardians. Kwashiorkor also may occur because of gastrointestinal malabsorption. We present a unique case of kwashiorkor that revealed an underlying diagnosis of pancreatic insufficiency.

A 12-year-old girl presented to the hospital with 4 days of watery nonbloody diarrhea occurring with every feeding as well as new onset of presumed diaper dermatitis that had not responded to nystatin cream. Facial swelling also was noted the day prior to admission. Her medical history was notable for cerebral palsy secondary to nonaccidental trauma, leaving the patient nonverbal and quadriplegic. She had numerous prior admissions for sepsis with marked hypotension and more recently was diagnosed with insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus. She had never lived outside the United States and resided at home with her adoptive parents.

Physical examination revealed a nonverbal underweight girl (weight, 25 kg). Large areas of denudation with surrounding desquamated skin resembling flaking enamel paint covered the buttocks and posterior legs bilaterally (Figure). She had linear hyperpigmented patches on the dorsal hands with one superficial erosion on the left wrist. Marked periorbital edema as well as nonpitting edema of the face, arms, and legs were present.

Upon additional questioning, the patient’s adoptive parent reported a diet of formula containing 1.0 cal/mL with 200-mL feedings 3 times daily through a Geiger-Müller tube, providing a daily protein intake of approximately 17.7 g per day (0.7 g/kg per day). On the day of admission, abnormal laboratory findings included low protein and albumin levels at 4.6 g/dL (reference range, 5.7–8.2 g/dL) and 2.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.2–4.8 g/dL), respectively; an elevated aspartate aminotransferase level of 73 U/L (reference range, 10–34 U/L); and an elevated alanine aminotransferase level of 80 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Based on the patient’s characteristic clinical findings and abnormal laboratory values, a diagnosis of acute kwashiorkor was made. Although the zinc level was low at 0.29 µg/mL (reference range, 0.66–1.10 µg/mL), the patient did not have any periorificial involvement to support a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica.

Upon further workup, stool elastase was measured at less than 50 µg per gram of stool (reference range, >200 µg pancreatic elastase per gram of stool), confirming a diagnosis of severe pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic enzyme supplementation was initiated along with an increase in protein intake to 1.5 g/kg per day. The patient’s hospital course was complicated by respiratory distress and sepsis, leading to a prolonged hospital stay. A component of refeeding syndrome may have contributed to the patient’s respiratory distress.

Kwashiorkor, a form of protein malnutrition, is caused by inadequate protein intake and usually is seen in developing countries when children are weaned from breastmilk to a diet high in starch and low in protein. It is characterized by edema, growth retardation, a characteristic dermatosis, depigmentation of hair, lethargy, and irritability.1 If left untreated, kwashiorkor can be fatal. Skin changes associated with kwashiorkor first occur in areas of friction or pressure. The skin develops patches of hyperpigmentation that subsequently desquamate in a pattern likened to flaky paint. In the current case of a nonmobile child with diarrhea, prominent involvement of the buttocks and thighs would be expected. This dermatosis does not appear in marasmus and is pathognomonic for kwashiorkor when seen in a child with edema.2

Children in the United States developing kwashiorkor secondary to severely restrictive diets has been reported.3 However, kwashiorkor also may occur due to underlying chronic malabsorptive disease. There have been rare reports of children with cystic fibrosis presenting with kwashiorkor,4 as well as a case of kwashiorkor secondary to underlying infantile Crohn disease.5

Cerebral palsy is associated with multiple different risk factors for malnutrition. Musculoskeletal deformities, oral-motor difficulties, medication side effects, limited communication skills, compromised pulmonary status, and poor muscle tone can all contribute to energy and nutrient deprivation.6 A 2018 study including 728 children registered into the Bangladesh Cerebral Palsy Register between January 2015 and December 2016 demonstrated that more than two-thirds were underweight (70.0%) and stunted (73.1%) and that children with tri/quadriplegic cerebral palsy presented with the highest proportion of severe malnutrition.7 In another report (N=142), up to 85% of children with spastic quadriplegia had severe feeding problems,8 making this population particularly high risk for poor nutritional status.

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency is characterized by reduced secretion of amylase, lipase, and protease, and it may result in diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption of essential nutrients, and malnutrition. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency may occur in the setting of chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, and cystic fibrosis. Our patient had numerous hospitalizations for sepsis marked by hypotension, and in the absence of more typical causes, we postulate that both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic damage resulted from prolonged hypotension. A sweat chloride test was not performed, as the patient had not experienced frequent pulmonary infections or other signs of cystic fibrosis.

According to a report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization/United Nations University (FAO/WHO/UNU), protein should provide at least 10% of the total caloric intake in a child.9 Although the adoptive parent approximated that our patient received 12% of her daily calories in the form of protein, the amount that she absorbed in the context of pancreatic insufficiency was undoubtedly much lower.