User login

Optimizing Well-being, Practice Culture, and Professional Thriving in an Era of Turbulence

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

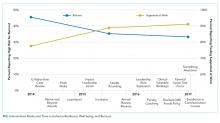

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Letter: Working together to empower our next generation of leaders

Editor:

Dr. Nasim Afsar’s article of June 2, 2017 (“A case for building our leadership skills”) calls for the integration of leadership skills into medical training, and we at the University of Colorado wholeheartedly agree. There are several institutions around the country that are already addressing this problem head on, and we write this letter to highlight a few educational programs we’ve created that demonstrate the power of arming our trainees with this skill set. Furthermore, we wish to encourage collaboration between educators and institutions that are engaged in similar work in the hopes of moving this field forward.

Here at the University of Colorado, a team of Hospital Medicine faculty has created a number of programs to address the leadership education gap in learners at the undergraduate medical education,1 graduate medical education,2 and fellowship levels – creating a pipeline for developing leaders in hospital medicine. These programs include an immersive medical student elective, a dedicated leadership track in the Internal Medicine Residency Program, and a fellowship program in Hospital Medicine focused on Quality Improvement and Health Systems Leadership. Our goal in each of these programs to equip trainees across the spectrum of medical education with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to lead high-functioning teams.

In our 5-year experience with our leadership training pipeline, we’ve learned a few important lessons. First, medical trainees are rarely exposed to the leadership skill set elsewhere in medical training, and are eager to learn new approaches to common problems that they encounter on a daily basis: How do I negotiate with a colleague? How can I motivate team members to change behavior to accomplish a goal? How can I use data to support requests for resources?

Secondly, trainees who are exposed to leadership concepts and who are given the opportunity to practice them through challenging project work in the live system routinely make meaningful changes to the health system. Our trainees have revamped our process of managing interhospital transfers, have decreased rates of inappropriate antibiotic usage, and have enhanced the patient experience in our stroke units. Further, our recent graduates have positioned themselves as leaders in health systems. Our graduates are leading a QI program at a major academic center, being promoted to educational leadership roles such as assistant program director within a residency training program, directing process improvement in a developing country, and leading the operations unit of a large physician group.

As Dr. Afsar highlights, there is much work to be done to better equip trainees with the skill set to lead. We strongly encourage other training programs to develop strategies to teach leadership and create forums for trainees to practice their burgeoning skill set. In addition to responding to Dr. Afsar’s call to develop programs, we should form collaborative working groups through our regional and national organizations to develop comprehensive leadership programs for medical trainees at all levels. Collaborating to empower the next generation of providers is critical to our future as hospitalists as we continue to take the lead in improving and shaping our health care systems.

Tyler Anstett, DO

Manuel Diaz, MD

Emily Gottenborg, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.

References

1. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital Medicine Resident Training Tracks: Developing the Hospital Medicine Pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

2. Tad-y D, Price L, Cumbler E, Levin D, Wald H, Glasheen J. An experiential quality improvement curriculum for the inpatient setting – part 1: design phase of a QI project. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2014;10:9841. http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9841.

Editor:

Dr. Nasim Afsar’s article of June 2, 2017 (“A case for building our leadership skills”) calls for the integration of leadership skills into medical training, and we at the University of Colorado wholeheartedly agree. There are several institutions around the country that are already addressing this problem head on, and we write this letter to highlight a few educational programs we’ve created that demonstrate the power of arming our trainees with this skill set. Furthermore, we wish to encourage collaboration between educators and institutions that are engaged in similar work in the hopes of moving this field forward.

Here at the University of Colorado, a team of Hospital Medicine faculty has created a number of programs to address the leadership education gap in learners at the undergraduate medical education,1 graduate medical education,2 and fellowship levels – creating a pipeline for developing leaders in hospital medicine. These programs include an immersive medical student elective, a dedicated leadership track in the Internal Medicine Residency Program, and a fellowship program in Hospital Medicine focused on Quality Improvement and Health Systems Leadership. Our goal in each of these programs to equip trainees across the spectrum of medical education with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to lead high-functioning teams.

In our 5-year experience with our leadership training pipeline, we’ve learned a few important lessons. First, medical trainees are rarely exposed to the leadership skill set elsewhere in medical training, and are eager to learn new approaches to common problems that they encounter on a daily basis: How do I negotiate with a colleague? How can I motivate team members to change behavior to accomplish a goal? How can I use data to support requests for resources?

Secondly, trainees who are exposed to leadership concepts and who are given the opportunity to practice them through challenging project work in the live system routinely make meaningful changes to the health system. Our trainees have revamped our process of managing interhospital transfers, have decreased rates of inappropriate antibiotic usage, and have enhanced the patient experience in our stroke units. Further, our recent graduates have positioned themselves as leaders in health systems. Our graduates are leading a QI program at a major academic center, being promoted to educational leadership roles such as assistant program director within a residency training program, directing process improvement in a developing country, and leading the operations unit of a large physician group.

As Dr. Afsar highlights, there is much work to be done to better equip trainees with the skill set to lead. We strongly encourage other training programs to develop strategies to teach leadership and create forums for trainees to practice their burgeoning skill set. In addition to responding to Dr. Afsar’s call to develop programs, we should form collaborative working groups through our regional and national organizations to develop comprehensive leadership programs for medical trainees at all levels. Collaborating to empower the next generation of providers is critical to our future as hospitalists as we continue to take the lead in improving and shaping our health care systems.

Tyler Anstett, DO

Manuel Diaz, MD

Emily Gottenborg, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.

References

1. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital Medicine Resident Training Tracks: Developing the Hospital Medicine Pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

2. Tad-y D, Price L, Cumbler E, Levin D, Wald H, Glasheen J. An experiential quality improvement curriculum for the inpatient setting – part 1: design phase of a QI project. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2014;10:9841. http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9841.

Editor:

Dr. Nasim Afsar’s article of June 2, 2017 (“A case for building our leadership skills”) calls for the integration of leadership skills into medical training, and we at the University of Colorado wholeheartedly agree. There are several institutions around the country that are already addressing this problem head on, and we write this letter to highlight a few educational programs we’ve created that demonstrate the power of arming our trainees with this skill set. Furthermore, we wish to encourage collaboration between educators and institutions that are engaged in similar work in the hopes of moving this field forward.

Here at the University of Colorado, a team of Hospital Medicine faculty has created a number of programs to address the leadership education gap in learners at the undergraduate medical education,1 graduate medical education,2 and fellowship levels – creating a pipeline for developing leaders in hospital medicine. These programs include an immersive medical student elective, a dedicated leadership track in the Internal Medicine Residency Program, and a fellowship program in Hospital Medicine focused on Quality Improvement and Health Systems Leadership. Our goal in each of these programs to equip trainees across the spectrum of medical education with the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to lead high-functioning teams.

In our 5-year experience with our leadership training pipeline, we’ve learned a few important lessons. First, medical trainees are rarely exposed to the leadership skill set elsewhere in medical training, and are eager to learn new approaches to common problems that they encounter on a daily basis: How do I negotiate with a colleague? How can I motivate team members to change behavior to accomplish a goal? How can I use data to support requests for resources?

Secondly, trainees who are exposed to leadership concepts and who are given the opportunity to practice them through challenging project work in the live system routinely make meaningful changes to the health system. Our trainees have revamped our process of managing interhospital transfers, have decreased rates of inappropriate antibiotic usage, and have enhanced the patient experience in our stroke units. Further, our recent graduates have positioned themselves as leaders in health systems. Our graduates are leading a QI program at a major academic center, being promoted to educational leadership roles such as assistant program director within a residency training program, directing process improvement in a developing country, and leading the operations unit of a large physician group.

As Dr. Afsar highlights, there is much work to be done to better equip trainees with the skill set to lead. We strongly encourage other training programs to develop strategies to teach leadership and create forums for trainees to practice their burgeoning skill set. In addition to responding to Dr. Afsar’s call to develop programs, we should form collaborative working groups through our regional and national organizations to develop comprehensive leadership programs for medical trainees at all levels. Collaborating to empower the next generation of providers is critical to our future as hospitalists as we continue to take the lead in improving and shaping our health care systems.

Tyler Anstett, DO

Manuel Diaz, MD

Emily Gottenborg, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.

References

1. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital Medicine Resident Training Tracks: Developing the Hospital Medicine Pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):173-176. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2703.

2. Tad-y D, Price L, Cumbler E, Levin D, Wald H, Glasheen J. An experiential quality improvement curriculum for the inpatient setting – part 1: design phase of a QI project. MedEdPORTAL Publications. 2014;10:9841. http://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9841.