User login

Optimizing Well-being, Practice Culture, and Professional Thriving in an Era of Turbulence

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

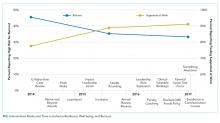

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

In 2010, the Journal of Hospital Medicine published an article proposing a “talent facilitation” framework for addressing physician workforce challenges.1 Since then, continuous changes in healthcare work environments and shifts in relevant policies have intensified a sense of clinician workforce crisis in the United States,2,3 often described as an epidemic of burnout. Unfortunately, hospital medicine remains among the specialties most impacted by high burnout rates and related turnover.4-6

THE HEALTHCARE TALENT IMPERATIVE

Despite efforts to address the sustainability of careers in hospital medicine, common approaches remain mostly reactive. Existing research on burnout is largely descriptive, focusing on the magnitude of the problem,3 the links between burnout and diminished productivity or turnover,7 and the negative impact of burnout on patient care.8.9 Improvement efforts often focus on rescuing individuals from burnout, rather than prevention.10 While evidence exists that both individually targeted interventions (eg, mindfulness-based stress reduction) and institutional changes (eg, improvements in the operation of care teams) can reduce burnout, efforts to promote individuals’ resilience appear to have limited impact.11,12

Given our field’s reputation for innovation, we believe hospitalist groups must lead the way in developing practical solutions that enhance the well-being of their members, by doing more than exhorting clinicians to “heal themselves” or imploring executives to fix care delivery systems. In this article, we describe an approach to increase resilience and well-being in a large, academic hospital medicine practice and offer an emerging list of best practices.

FROM BURNOUT TO WELL-BEING—A PARADIGM SHIFT

Maslach et al. demonstrated that burnout reflects an individual’s experience of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization of human interactions, and decreased sense of accomplishment at work.13 Updated frameworks emphasize that well-being and lower burnout arise from workflow efficiency, a surrounding culture of wellness, and attention to individual resilience.14 Emerging evidence suggests that burnout and well-being are, in part, a collective experience.15 As outlined in the recently published “Charter on Physician Well-being,”16 this realization creates an opportunity for clinical groups to enhance collective well-being—or thriving—rather than asking individuals to take personal responsibility for resilience or waiting for a top-down system redesign to fix drivers of burnout.

APPLYING THE NEW PARADIGM TO HOSPITAL MEDICINE

In 2013, our academic hospital medicine group set a new vision: To become the best in the nation by being an outstanding place to work. We held an inclusive divisional strategic planning retreat, which focused on clarifying the group’s six core values and exploring how to translate the values into structures, processes, and behaviors that reinforced, rather than undermined, a positive work environment. We used these initial themes to create 16 novel interventions from 2014-2017 (Figure).

Notably, we pursued this work without explicit support or interference from senior leaders in our institution. There were no competing organizational efforts addressing hospitalist efficiency, turnover, or burnout until 2017 (Excellence in Communication, described below). Furthermore, we avoided individually targeted resilience efforts based on feedback from our group that “requiring resilience activities is like blaming the victim.” Intervention participation was not mandatory, out of respect for individual choice and to avoid impeding hospitalists’ daily work.

Before designing interventions, we created a measurement tool to assess our existing culture and track evolution over time (available upon request). We utilized the instrument to provoke emotional responses, surface paradoxes, uncover assumptions, and engage the group in iterative dialog that informed and calibrated interventions. The instrument itself drew from validated elements of existing tools to quantify perceptions across nine domains: meaningful work, autonomy, professional development, logistical support, health, fulfillment outside of work, collegiality, organizational learning, and safety culture.

Several subsequent interventions focused on the emotional experience of work. For example, we developed a formal mechanism (Something Awesome) for members to share the experience of positive emotions during daily work (eg, gratitude and awe) for five minutes at monthly group meetings. We created a Collaborative Case Review process, allowing members to submit concerning cases for nonpunitive discussion and coaching among peers. Finally, we created Above and Beyond Awards, through which members’ written praise of peers’ extraordinary efforts were distributed to the entire group.

We also pursued interventions designed to increase empathy and translate it to action. These included leader rounding on our clinical units, which sought to recognize and thank individuals for daily work and to uncover exigent needs, such as food or assistance with conflict resolution between services. We created “Flash Mobs” or group conversations, which are facilitated by a leader and convened in the hospital, in order to hear from people and discuss topics of concern in real time, such as increased patient volumes. Likewise, we established “The Incubator,” a half-day meeting held four to six times annually when selected clinical faculty applied design thinking techniques to create, test, and implement ideas to enhance workplace experience (eg, supplying healthy food to our common work space at low cost).

Another key focus was professional development for group members. Examples included a three-year development program for new faculty (LaunchPad), increasing the number of available leadership roles for aspiring leaders, modifying annual reviews to focus on increasing individuals’ strengths-based work rather than solely grading performance, and creating a peer-support coaching program for newly hired members. In 2017, we began offering members a full shift credit to attend the hospital’s four-hour Excellence in Communication course, which covers six high-yield skills that increase efficiency, efficacy, and joy in practice.

Finally, we revised a number of structures and operational processes within our group’s control. We created a task force to address the needs of new parents and acquired a lactation room in the hospital. Instead of only covering offsite conference attendance (our old policy), we enhanced autonomy regarding use of continuing education dollars to allow faculty to fund any activity supporting their clinical practice. Finally, we applied quality improvement methodology to redesign the clinical schedule. This included blending value-stream mapping, software solutions, and a values-based framework to analyze proposed changes through the lens of waste elimination, IT feasibility, and whether the proposed changes aligned with the group’s core values.

IMPACT ON GROUP CULTURE AND WELL-BEING

We examined the impact of these tactics on workplace experience over a four-year period (Figure). In 2014, 30% of group members reported psychological safety, 24% had become more callous toward people in their current job, and 45% were experiencing burnout. By 2017, 59% felt a sense of psychological safety (69% increase), 15% had become more callous toward people (38% decrease), and 33% were experiencing burnout (27% decrease). Average annual turnover in the five years before the first survey was 13.2%; turnover declined during the intervention period to 6.6% (adjusted for increased number of positions). While few comprehensive models exist for calculating well-being program return on investment, the American Medical Association’s calculator17 demonstrated our group’s cost of burnout plus turnover in 2013 was $464,385 per year (assumptions in Appendix 1). We spent $343,517 on the 16 interventions between 2013 and 2017, representing an average annual cost of $86,000: $190,094 to buy-down clinical time for new leadership roles, $133,023 to fund time for the Incubator, $2,500 on gifts and awards, $4,900 on program supplies, and $10,000 on leadership training.

BEST PRACTICES FOR HOSPITALIST GROUPS

Based on the current literature and our experience, hospital medicine groups seeking to improve culture, resilience, and well-being should:

- Collaborate to define the group’s sense of purpose. Mission and vision are important, but most of the focus should be on surfacing, naming, and agreeing upon the group’s essential core values—the beliefs that inform whether hospitalists see the workplace as attractive, fair, and sustainable. Utilizing an expert, neutral facilitator is helpful.

- Assess culture—including, but not limited to, individual burnout and well-being—using preexisting questions from validated instruments. As culture is a product of systems, team climate, and leadership, measurement should include these domains.

- Monitor and share anonymous data from the assessment regularly (at least annually) as soon as possible after survey results are available. The data should drive inclusive, open, nonjudgmental dialog among group members and leaders in order to clarify, explore, and refine what the data mean.

- Undertake improvement efforts that emerge from the steps above, with a balanced focus on the three domains of well-being: efficiency of practice, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. Modify the number and intensity of interventions based on the group’s readiness and ability to control change in these domains. For example, some groups may have more excitement and ability to work on factors impacting the efficiency of practice, such as electronic health record templates, while others may wish to enhance opportunities for collegial interaction during the workday.

- Strive for codesign. Group members must be an integral part of the solution, rather than simply raise complaints with the expectation that leaders will devise solutions. Ideally, group members should have time, funding, or titles to lead improvement efforts.

- Opportunities to improve resilience and well-being should be widely available to all group members, but should not be mandatory.

CONCLUSION

The healthcare industry will continue to grapple with high rates of burnout and rapid change for the foreseeable future. We believe significant improvements in burnout rates and workplace experience can result from hospitalist-led interventions designed to improve experience of work among hospitalist clinicians, even as we await broader and necessary systematic efforts to address structural drivers of professional satisfaction. This work is vital if we are to honor our field’s history of productive innovation and navigate dynamic change in healthcare by attracting, engaging, developing, and retaining our most valuable asset: our people.

Disclosures

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

1. Kneeland PP, Kneeland C, Wachter RM. Bleeding talent: a lesson from industry on embracing physician workforce challenges. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):306-310. doi: 10.1002/jhm.594. PubMed

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

3. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-181. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2146. PubMed

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the General US Working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. PubMed

5. Vuong K. Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward. The Hospitalist. http://www.thehospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/130462/turnover-rate-hospitalist-groups-trending-downward; 2017, Feb 1.

6. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Wolosin RJ, Miller JA, Wetterneck TB. Worklife and satisfaction of hospitalists: toward flourishing careers. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):28-36. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1780-z. PubMed

7. Farr C. Siren song of tech lures New Doctors away from medicine. Shots. Health news from NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/07/19/423882899/siren-song-of-tech-lures-new-doctors-away-from-medicine; 2015, July 19.

8. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. PubMed

9. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:325. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-325. PubMed

10. Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. PubMed

11. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: A systematic review PLOS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. PubMed

12. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. PubMed

13. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. PubMed

14. Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. PubMed

15. Bohman B, Dyrbye L, Sinsky CA, et al. Physician well-being: the reciprocity of practice efficiency, culture of wellness, and personal resilience. NEJM Catalyst. 2017 Aug.

16. Sexton JB, Adair KC, Leonard MW, et al. Providing feedback following Leadership WalkRounds is associated with better patient safety culture, higher employee engagement and lower burnout. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(4):261-270. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006399. PubMed

17. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

18. American Medical Association. Nine Steps to Creating the Organizational Foundation for Joy in Medicine: culture of Wellness—track the business case for well-being. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/joy-in-medicine.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

What Is Career Success for Academic Hospitalists? A Qualitative Analysis of Early-Career Faculty Perspectives

Academic hospital medicine is a young specialty, with most faculty at the rank of instructor or assistant professor.1 Traditional markers of academic success for clinical and translational investigators emphasize progressive, externally funded grants, achievements in basic science research, and prolific publication in the peer-reviewed literature.2 Promotion is often used as a proxy measure for academic success.

Conceptual models of career success derived from nonhealthcare industries and for physician-scientists include both extrinsic and intrinsic domains.3,4 Extrinsic domains of career success include financial rewards (compensation) and progression in hierarchical status (advancement).3,4 Intrinsic domains of career success include pleasure derived from daily work (job satisfaction) and satisfaction derived from aspects of the career over time (career satisfaction).3,4