User login

In the Hospital: Laura Shea

We spoke with medical social worker Laura Shea, MSW, LICSW on her role at our tertiary care hospital. Laura’s reflections on the struggles and rewards of her job may resonate with those of us who search for balance and meaning in work.

Laura, tell us about yourself. What made you want to be a social worker?

I couldn’t really picture doing anything else. I got a degree in psychology and loved counseling. Social work was a natural fit because of the social justice component and the look into larger systems. I knew I had the skill set for this, and for those most marginalized, to be a supportive person for someone who doesn’t have that.

I also have a family member with major mental illness and chronic suicidality who I supported for a very long time. In many ways, I was a personal social worker advocating on their behalf while growing up. I remember being in high school when they overdosed, and going to the ER in the middle of the night. The next morning, I was back at school. I was a total do-gooder—President of the student council and on top of my grades. I tried dealing with this while keeping up the appearance that everything was ok, even though it wasn’t.

As I got older, there were middle-of-the-night phone calls professing suicidality which were so painful. I learned a lot about compartmentalizing and resiliency. It has given me an incredible amount of empathy for family members of patients. I have learned that it’s not always simple, and decisions aren’t easy, and solutions are complicated and can feel incomplete. We often hear, “Why hasn’t the family stepped in?” Well these issues are hard for families too, I know from firsthand experience.

At the end of the day, as challenging as the work is, I get something from it. I feel honored to bear witness to some of people’s darkest moments and also some of the most beautiful moments—the joys of coming out the other side of their process and journey.

How much of your personal story do you reveal to your patients?

I rarely do. However, to some families that are particularly devastated, I do share some of my family story. I try to affirm their challenge and acknowledge that family and friends can’t always “solve this.”

We have a culture that reveres going above and beyond, however I really honor those family members who can set boundaries. Sometimes caregivers need space, that doesn’t make you a bad person. It’s actually brave and really hard to do. You can’t give from an empty well.

Laura, tell us about your typical day.

Well, it begins with responding to e-mails. Then I meet with patients and obtain collateral to prep for multidisciplinary rounds (with physicians, RNs, case managers). I usually consult on 20-30 patients a day. In the afternoon, it varies -- maybe three patients are leaving that may need my help with things like providing substance use information or shelter resources. Typically, I’ll have a few complicated long-term patients, who may have challenging family dynamics, ongoing goals of care discussions, or behavioral difficulties. These patients keep me just as busy, it’s not quite as time sensitive but I have to keep chipping away at the work.

Seems like a busy day. Do you get a break at all?

When possible, I take a walk in the woods behind the hospital on my lunch break. There’s a beautiful path, it’s an important part of my day -- getting outside and taking a step back. I bring my pager, so I am still connected.

I used to feel like I didn’t have time to take a break, and I would work through lunch. But now I find if I take a break, I am more productive the rest of the day because it makes me more mindful. It quiets me a little, gives me perspective on the stress and stressors of working in the hospital and allows me to better connect to my job and others around me.

What does a successful day look like?

Well, one involved a homeless gentleman and a search for his family. He was in his 40s, though he looked much older, and recently had been assaulted at a shelter. He presented to either the ER or was admitted to various hospitals 14 times over the past month – typically for intoxication and hypothermia. He kept saying “I just need to find my brother” though no one was taking this request too seriously. We spent a lot of time looking for his brother with the Office of Public Guardian’s help, and we actually found him! The patient hadn’t seen his brother in four years and as it turns out was searching for him too. The brother thought the patient had passed away. With his brother’s support, the patient is now housed, going to alcohol treatment, reunited with his family, and taking his medications. His whole life changed. So that was amazing, and a reminder of how rewarding this job can be.

What is most challenging about your work?

The biggest challenge is grappling with the limitations of the system, and discharging someone to the community when the community has limited resources for these patients.

Though it’s not just the limitation of resources, some patients have been through the system so many times that as a coping mechanism and to protect themselves they do everything possible to push you away. They have walls firmly up, because of prior negative experiences with providers. I am not fazed by being yelled at, but it’s hard trying to connect with someone who has learned not to let you in. These are often the patients that need the support the most, and yet I want to respect their ability to have control or to say no. It is a tough balance.

What’s fun about your job?

I love meeting new people. I met a woman a few weeks ago who was talking about being a hippie in the ‘60s in San Francisco, and how great it was and how soft millennials are. She actually put meth in her coffee because she needed a pick-me-up to clean her house. You can’t make this stuff up! It’s just really fascinating how people live their lives, and to have a window into their world and perspective is a privilege.

Do you take work home with you or do you disconnect?

I try to disconnect, however there are days when something sticks with you and you really worry and wonder about a patient. As I mentioned, you can’t give from an empty well—so I try to acknowledge this. I find that trying to have a rich life outside of work is an important part of self-care as well. Social work is a big part of my identity but it’s not entirely who I am. I focus on friends, family, travel, yoga, and things that sustain me. I can’t do my job effectively if I am not taking a step back regularly.

What advice do you have for other providers and for patients?

The hospital is so overwhelming for our patients, more so than some providers realize. I could be in the room with a patient for 45 minutes and six different providers may come in. I try to maintain that this is the patient’s bedroom I’m walking into. It’s a private, and a sacred space for them. That’s where they sleep. This is where they are trying to recover and grapple with what brought them into the hospital.

Laura, thank you so much for telling us about your work. Anything else you’d like to share with us?

Some days I’ll go home completely exhausted and wiped out, and at first, I don’t feel like I did a single solitary thing. Some of the things that I’m trying to help people work through ...it never occurred to me that someone could, for whatever reason, find themselves in such challenging situations. I don’t have a magic wand to provide someone with housing or sobriety, but maybe in that moment I can begin to make a connection. When I just listen, I am beginning to build relationships – which for some patients is something they haven’t had in a long time. It’s in these moments of being present, without an agenda, walking with them in their challenges, that I feel most connected to the work.

Thanks, Laura.

We spoke with medical social worker Laura Shea, MSW, LICSW on her role at our tertiary care hospital. Laura’s reflections on the struggles and rewards of her job may resonate with those of us who search for balance and meaning in work.

Laura, tell us about yourself. What made you want to be a social worker?

I couldn’t really picture doing anything else. I got a degree in psychology and loved counseling. Social work was a natural fit because of the social justice component and the look into larger systems. I knew I had the skill set for this, and for those most marginalized, to be a supportive person for someone who doesn’t have that.

I also have a family member with major mental illness and chronic suicidality who I supported for a very long time. In many ways, I was a personal social worker advocating on their behalf while growing up. I remember being in high school when they overdosed, and going to the ER in the middle of the night. The next morning, I was back at school. I was a total do-gooder—President of the student council and on top of my grades. I tried dealing with this while keeping up the appearance that everything was ok, even though it wasn’t.

As I got older, there were middle-of-the-night phone calls professing suicidality which were so painful. I learned a lot about compartmentalizing and resiliency. It has given me an incredible amount of empathy for family members of patients. I have learned that it’s not always simple, and decisions aren’t easy, and solutions are complicated and can feel incomplete. We often hear, “Why hasn’t the family stepped in?” Well these issues are hard for families too, I know from firsthand experience.

At the end of the day, as challenging as the work is, I get something from it. I feel honored to bear witness to some of people’s darkest moments and also some of the most beautiful moments—the joys of coming out the other side of their process and journey.

How much of your personal story do you reveal to your patients?

I rarely do. However, to some families that are particularly devastated, I do share some of my family story. I try to affirm their challenge and acknowledge that family and friends can’t always “solve this.”

We have a culture that reveres going above and beyond, however I really honor those family members who can set boundaries. Sometimes caregivers need space, that doesn’t make you a bad person. It’s actually brave and really hard to do. You can’t give from an empty well.

Laura, tell us about your typical day.

Well, it begins with responding to e-mails. Then I meet with patients and obtain collateral to prep for multidisciplinary rounds (with physicians, RNs, case managers). I usually consult on 20-30 patients a day. In the afternoon, it varies -- maybe three patients are leaving that may need my help with things like providing substance use information or shelter resources. Typically, I’ll have a few complicated long-term patients, who may have challenging family dynamics, ongoing goals of care discussions, or behavioral difficulties. These patients keep me just as busy, it’s not quite as time sensitive but I have to keep chipping away at the work.

Seems like a busy day. Do you get a break at all?

When possible, I take a walk in the woods behind the hospital on my lunch break. There’s a beautiful path, it’s an important part of my day -- getting outside and taking a step back. I bring my pager, so I am still connected.

I used to feel like I didn’t have time to take a break, and I would work through lunch. But now I find if I take a break, I am more productive the rest of the day because it makes me more mindful. It quiets me a little, gives me perspective on the stress and stressors of working in the hospital and allows me to better connect to my job and others around me.

What does a successful day look like?

Well, one involved a homeless gentleman and a search for his family. He was in his 40s, though he looked much older, and recently had been assaulted at a shelter. He presented to either the ER or was admitted to various hospitals 14 times over the past month – typically for intoxication and hypothermia. He kept saying “I just need to find my brother” though no one was taking this request too seriously. We spent a lot of time looking for his brother with the Office of Public Guardian’s help, and we actually found him! The patient hadn’t seen his brother in four years and as it turns out was searching for him too. The brother thought the patient had passed away. With his brother’s support, the patient is now housed, going to alcohol treatment, reunited with his family, and taking his medications. His whole life changed. So that was amazing, and a reminder of how rewarding this job can be.

What is most challenging about your work?

The biggest challenge is grappling with the limitations of the system, and discharging someone to the community when the community has limited resources for these patients.

Though it’s not just the limitation of resources, some patients have been through the system so many times that as a coping mechanism and to protect themselves they do everything possible to push you away. They have walls firmly up, because of prior negative experiences with providers. I am not fazed by being yelled at, but it’s hard trying to connect with someone who has learned not to let you in. These are often the patients that need the support the most, and yet I want to respect their ability to have control or to say no. It is a tough balance.

What’s fun about your job?

I love meeting new people. I met a woman a few weeks ago who was talking about being a hippie in the ‘60s in San Francisco, and how great it was and how soft millennials are. She actually put meth in her coffee because she needed a pick-me-up to clean her house. You can’t make this stuff up! It’s just really fascinating how people live their lives, and to have a window into their world and perspective is a privilege.

Do you take work home with you or do you disconnect?

I try to disconnect, however there are days when something sticks with you and you really worry and wonder about a patient. As I mentioned, you can’t give from an empty well—so I try to acknowledge this. I find that trying to have a rich life outside of work is an important part of self-care as well. Social work is a big part of my identity but it’s not entirely who I am. I focus on friends, family, travel, yoga, and things that sustain me. I can’t do my job effectively if I am not taking a step back regularly.

What advice do you have for other providers and for patients?

The hospital is so overwhelming for our patients, more so than some providers realize. I could be in the room with a patient for 45 minutes and six different providers may come in. I try to maintain that this is the patient’s bedroom I’m walking into. It’s a private, and a sacred space for them. That’s where they sleep. This is where they are trying to recover and grapple with what brought them into the hospital.

Laura, thank you so much for telling us about your work. Anything else you’d like to share with us?

Some days I’ll go home completely exhausted and wiped out, and at first, I don’t feel like I did a single solitary thing. Some of the things that I’m trying to help people work through ...it never occurred to me that someone could, for whatever reason, find themselves in such challenging situations. I don’t have a magic wand to provide someone with housing or sobriety, but maybe in that moment I can begin to make a connection. When I just listen, I am beginning to build relationships – which for some patients is something they haven’t had in a long time. It’s in these moments of being present, without an agenda, walking with them in their challenges, that I feel most connected to the work.

Thanks, Laura.

We spoke with medical social worker Laura Shea, MSW, LICSW on her role at our tertiary care hospital. Laura’s reflections on the struggles and rewards of her job may resonate with those of us who search for balance and meaning in work.

Laura, tell us about yourself. What made you want to be a social worker?

I couldn’t really picture doing anything else. I got a degree in psychology and loved counseling. Social work was a natural fit because of the social justice component and the look into larger systems. I knew I had the skill set for this, and for those most marginalized, to be a supportive person for someone who doesn’t have that.

I also have a family member with major mental illness and chronic suicidality who I supported for a very long time. In many ways, I was a personal social worker advocating on their behalf while growing up. I remember being in high school when they overdosed, and going to the ER in the middle of the night. The next morning, I was back at school. I was a total do-gooder—President of the student council and on top of my grades. I tried dealing with this while keeping up the appearance that everything was ok, even though it wasn’t.

As I got older, there were middle-of-the-night phone calls professing suicidality which were so painful. I learned a lot about compartmentalizing and resiliency. It has given me an incredible amount of empathy for family members of patients. I have learned that it’s not always simple, and decisions aren’t easy, and solutions are complicated and can feel incomplete. We often hear, “Why hasn’t the family stepped in?” Well these issues are hard for families too, I know from firsthand experience.

At the end of the day, as challenging as the work is, I get something from it. I feel honored to bear witness to some of people’s darkest moments and also some of the most beautiful moments—the joys of coming out the other side of their process and journey.

How much of your personal story do you reveal to your patients?

I rarely do. However, to some families that are particularly devastated, I do share some of my family story. I try to affirm their challenge and acknowledge that family and friends can’t always “solve this.”

We have a culture that reveres going above and beyond, however I really honor those family members who can set boundaries. Sometimes caregivers need space, that doesn’t make you a bad person. It’s actually brave and really hard to do. You can’t give from an empty well.

Laura, tell us about your typical day.

Well, it begins with responding to e-mails. Then I meet with patients and obtain collateral to prep for multidisciplinary rounds (with physicians, RNs, case managers). I usually consult on 20-30 patients a day. In the afternoon, it varies -- maybe three patients are leaving that may need my help with things like providing substance use information or shelter resources. Typically, I’ll have a few complicated long-term patients, who may have challenging family dynamics, ongoing goals of care discussions, or behavioral difficulties. These patients keep me just as busy, it’s not quite as time sensitive but I have to keep chipping away at the work.

Seems like a busy day. Do you get a break at all?

When possible, I take a walk in the woods behind the hospital on my lunch break. There’s a beautiful path, it’s an important part of my day -- getting outside and taking a step back. I bring my pager, so I am still connected.

I used to feel like I didn’t have time to take a break, and I would work through lunch. But now I find if I take a break, I am more productive the rest of the day because it makes me more mindful. It quiets me a little, gives me perspective on the stress and stressors of working in the hospital and allows me to better connect to my job and others around me.

What does a successful day look like?

Well, one involved a homeless gentleman and a search for his family. He was in his 40s, though he looked much older, and recently had been assaulted at a shelter. He presented to either the ER or was admitted to various hospitals 14 times over the past month – typically for intoxication and hypothermia. He kept saying “I just need to find my brother” though no one was taking this request too seriously. We spent a lot of time looking for his brother with the Office of Public Guardian’s help, and we actually found him! The patient hadn’t seen his brother in four years and as it turns out was searching for him too. The brother thought the patient had passed away. With his brother’s support, the patient is now housed, going to alcohol treatment, reunited with his family, and taking his medications. His whole life changed. So that was amazing, and a reminder of how rewarding this job can be.

What is most challenging about your work?

The biggest challenge is grappling with the limitations of the system, and discharging someone to the community when the community has limited resources for these patients.

Though it’s not just the limitation of resources, some patients have been through the system so many times that as a coping mechanism and to protect themselves they do everything possible to push you away. They have walls firmly up, because of prior negative experiences with providers. I am not fazed by being yelled at, but it’s hard trying to connect with someone who has learned not to let you in. These are often the patients that need the support the most, and yet I want to respect their ability to have control or to say no. It is a tough balance.

What’s fun about your job?

I love meeting new people. I met a woman a few weeks ago who was talking about being a hippie in the ‘60s in San Francisco, and how great it was and how soft millennials are. She actually put meth in her coffee because she needed a pick-me-up to clean her house. You can’t make this stuff up! It’s just really fascinating how people live their lives, and to have a window into their world and perspective is a privilege.

Do you take work home with you or do you disconnect?

I try to disconnect, however there are days when something sticks with you and you really worry and wonder about a patient. As I mentioned, you can’t give from an empty well—so I try to acknowledge this. I find that trying to have a rich life outside of work is an important part of self-care as well. Social work is a big part of my identity but it’s not entirely who I am. I focus on friends, family, travel, yoga, and things that sustain me. I can’t do my job effectively if I am not taking a step back regularly.

What advice do you have for other providers and for patients?

The hospital is so overwhelming for our patients, more so than some providers realize. I could be in the room with a patient for 45 minutes and six different providers may come in. I try to maintain that this is the patient’s bedroom I’m walking into. It’s a private, and a sacred space for them. That’s where they sleep. This is where they are trying to recover and grapple with what brought them into the hospital.

Laura, thank you so much for telling us about your work. Anything else you’d like to share with us?

Some days I’ll go home completely exhausted and wiped out, and at first, I don’t feel like I did a single solitary thing. Some of the things that I’m trying to help people work through ...it never occurred to me that someone could, for whatever reason, find themselves in such challenging situations. I don’t have a magic wand to provide someone with housing or sobriety, but maybe in that moment I can begin to make a connection. When I just listen, I am beginning to build relationships – which for some patients is something they haven’t had in a long time. It’s in these moments of being present, without an agenda, walking with them in their challenges, that I feel most connected to the work.

Thanks, Laura.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Use of Smartphones and Mobile Devices

Over 90% of Americans own mobile phones, and their use for internet access is rising rapidly (31% in 2009, 63% in 2013).[1] This has prompted growth in mobile health (mHealth) programs for outpatient settings,[2] and similar growth is anticipated for inpatient settings.[3] Hospitals and the healthcare systems they operate within are increasingly tied to patient experience scores (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, Press Ganey) for both reputation and reimbursement.[4, 5] As a result, hospitals will need to invest future resources in a consumer‐facing digital experience. Despite these trends, basic information on mobile device ownership and usage by hospitalized patients is limited. This knowledge is needed to guide successful mHealth approaches to engage patients in acute care settings.

METHODS

We administered a 27‐question survey about mobile device use to all adult inpatients at a large urban California teaching hospital over 2 dates (October 27, 2013 and November 11, 2013) to create a cross‐sectional view of mobile device use at a hospital that offers free wireless Internet (WiFi) and personal health records (Internet‐accessible individualized medical records). Average census was 447, and we excluded patients for: age under 18 years (98), admission for neurological problems (75), altered mental status (35), nonEnglish speaking (30), or unavailable if patients were not in their room after 2 attempts spaced 30 to 60 minutes apart (36), leaving 173 eligible. We performed descriptive statistics and unadjusted associations ([2] test) to explore patterns of mobile device use.

RESULTS

We enrolled 152 patients (88% response rate): 77 (51%) male, average age 53 years (1992 years), 84 (56%) white, 115 (75%) with Medicare or commercial insurance. We found 85 (56%) patients brought a smartphone, and 82/85 (95%) used it during their hospital stay. Additionally, 41 (27%) patients brought a tablet, and 29 (19%) brought a laptop; usage was 37/41 (90%) for tablets and 24/29 (83%) for laptops. One hundred three (68%) patients brought at least 1 mobile computing device (smartphone, tablet, laptop) during their hospital stay. Overall device usage was highest among oncology patients (85%) and lowest among medicine patients (54%) (Table 1). Device usage also varied by age (<65 years old: 79% vs 65 years old: 27%), insurance status (private/Medicare: 70% vs Medicaid/other: 59%), and race/ethnicity (white: 73% vs non‐white: 62%), although only age was statistically significant (P<0.01; all others >0.05).

| Total, N=152 | Medicine, n=39 | Surgery, n=47 | Oncology, n=34 | All Others, n=32* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Average age, y (range) | 53.2 (1992) | 55.7 (2092) | 51.7 (1979) | 51.2 (2377) | 53.9 (2584) |

| Medicare or commercial insurance | 75% (115) | 64% (25) | 87% (41) | 76% (26) | 72% (23) |

| Medicaid, other, or no insurance | 25% (37) | 36% (14) | 13% (6) | 24% (8) | 28% (9) |

| Non‐white race/ethnicity | 44% (68) | 56% (22) | 36% (17) | 38% (13) | 50%(16) |

| Female gender | 49% (75) | 49% (19) | 45% (21) | 47% (16) | 59% (19) |

| Device ownership/usage | |||||

| Own smartphone | 62% (94) | 54% (21) | 66% (31) | 74% (25) | 53% (17) |

| Brought smartphone | 55% (83) | 41% (16) | 60% (28) | 71% (24) | 48% (15) |

| Brought laptop | 19% (29) | 18% (7) | 11% (5) | 41% (14) | 10% (3) |

| Brought tablet | 27% (41) | 18% (7) | 26% (12) | 50% (17) | 16% (5) |

| Brought 1 above devices | 68% (103) | 54% (21) | 68% (32) | 85% (29) | 68% (21) |

| Ever used an app | 63% (95) | 51% (20) | 72% (34) | 79% (27) | 45% (14) |

| Ever used an app for health purposes | 22% (34) | 18% (7) | 21% (10) | 24% (8) | 29% (9) |

| Accessed PHR with mobile device | 31% (47) | 26% (10) | 26% (12) | 47% (16) | 29% (9) |

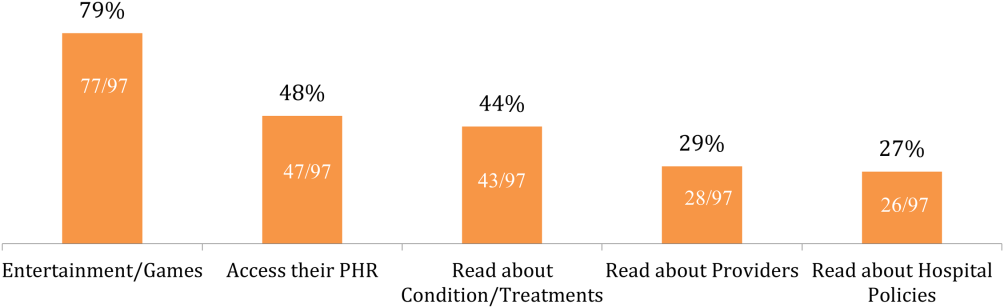

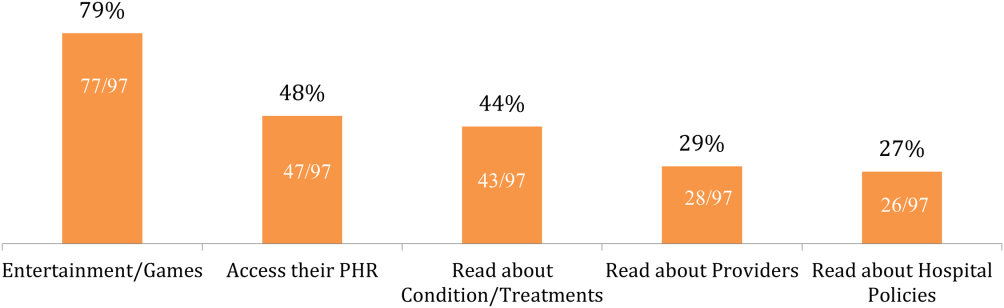

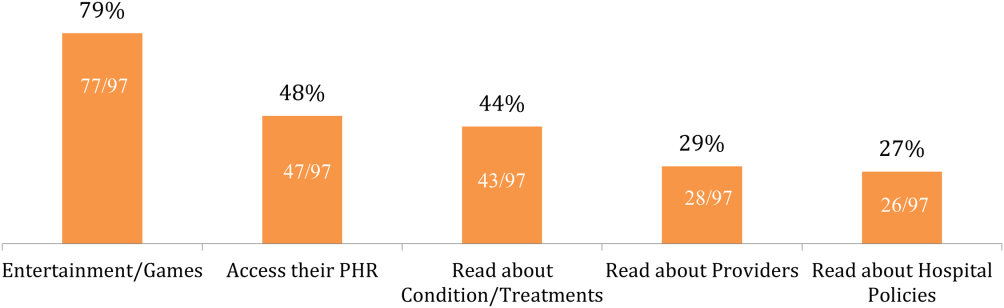

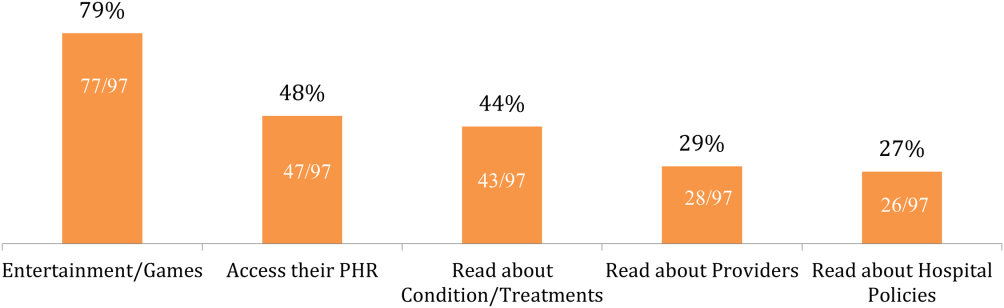

Of the patients with mobile devices (smartphone, tablet, laptop), 97/103 (94%) used them during their hospitalization and for a wide array of activities (Figure 1): 47/97 (48%) accessed their personal health record (PHR), and most of these patients (38/47, 81%) reported this improved their inpatient experience. Additionally, 43/97 (44%) patients used their mobile devices to search for information about doctors, conditions, or treatments; most of these patients (39/43, 91%) used Google to search for this information, and most 29/43 (67%) felt this information made them more confident in their care.

COMMENT

Over two‐thirds of patients in our study brought and used 1 or more mobile devices to the hospital. Despite this level of engagement with mobile devices, relatively few inpatients used their device to access their online PHR, which suggests information technology access is not the leading barrier to PHR access or mHealth engagement during hospitalization. In light of growing patient enthusiasm for PHRs,[6, 7] this represents an untapped opportunity to deliver personalized, patient‐centered care at the hospital bedside.

We also found that among the patients who did access their PHR on their mobile device, the vast majority (38/47, 81%) felt it improved their inpatient experience. Our PHR provides information such as test results and medications, but our survey suggests a number of patients look for health information, such as patient education tools, medication references, and provider information, outside of the PHR. For those patients, 29/43 (67%) felt these health‐related searches improved their experience. Although we did not ask patients why they used Web searches outside their PHR, we believe this suggests that patients desire more information than currently available via the PHR. Although this information might be difficult to incorporate into the PHR, at minimum, hospitals could develop mobile applications to provide patients with basic information about their providers and conditions. Beyond this, hospitals could develop or adopt mobile applications that align with strategic priorities such as improved physician‐provider communication, reduced hospital readmissions, and improved accuracy of medication reconciliation.

Our study has limitations. First, although we used a cross‐sectional, point‐in‐time approach to canvas the entire adult population in our hospital on 2 separate dates, our study was limited to 1 large urban hospital in California; device ownership and usage may vary in other settings. Second, although our hospital provides free WiFi, we did not assess whether patients experienced any connectivity issues that influenced their device usage patterns. Finally, we did not explore questions of access, ownership, and usage of mobile computing devices for family and friends who visited inpatients in our study. These questions are ripe for future research in this emerging area of mHeath.

In summary, our study suggests a role for hospitals to provide universal WiFi access to patients, and a role for both hospitals and healthcare providers to promote digital health programs. Our findings on mobile device use in the hospital are consistent with the growing popularity of mobile device usage nationwide. Patients are increasingly wired for new opportunities to both engage in their care and optimize their hospital experience through use of their mobile computing devices. Hospitals and providers should explore this potential for engagement, but may need to explore local trends in usage to target specific service lines and patient populations given differences in access and use.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge contributions by Christina Quist, MD, and Emily Gottenborg, MD, who assisted in data collection.

Disclosures: Data from this project were presented at the 2014 Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine, March 25, 2014 in Las Vegas, Nevada. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relative to this study. Dr. Ludwin, MD had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project by Drs. Ludwin and Greysen was supported by grants from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Partners in Care (Ronald Rankin Award) and the UCSF Mount Zion Health Fund. Dr. Greysen is also funded by a Pilot Award for Junior Investigators in Digital Health from the UCSF Dean's Office, Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (REAC). Additionally, Dr. Greysen receives career development support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)National Institute of Aging (NIA) through the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at UCSF Division of Geriatric Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA), a Career Development Award (1K23AG045338‐01), and the NIH‐NIA Loan Repayment Program.

- Device ownership over time. Pew Research Center. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/data‐trend/mobile/device‐ownership. Accessed April 3, 2014.

- , , , et al. The effectiveness of mobile‐health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(1):e1001363.

- , , . Can mobile health technologies transform health care? JAMA. 2013;310(22):2395–2396.

- Look ahead to succeed under VBP. Hosp Case Manag. 2014;22(7):92–93.

- , , , . The relationship between commercial website ratings and traditional hospital performance measures in the USA. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(3):194–202.

- , , , , . Consumers' perceptions of patient‐accessible electronic medical records. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e168.

- , , , et al. Access, interest, and attitudes toward electronic communication for health care among patients in the medical safety net. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(7):914–920.

Over 90% of Americans own mobile phones, and their use for internet access is rising rapidly (31% in 2009, 63% in 2013).[1] This has prompted growth in mobile health (mHealth) programs for outpatient settings,[2] and similar growth is anticipated for inpatient settings.[3] Hospitals and the healthcare systems they operate within are increasingly tied to patient experience scores (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, Press Ganey) for both reputation and reimbursement.[4, 5] As a result, hospitals will need to invest future resources in a consumer‐facing digital experience. Despite these trends, basic information on mobile device ownership and usage by hospitalized patients is limited. This knowledge is needed to guide successful mHealth approaches to engage patients in acute care settings.

METHODS

We administered a 27‐question survey about mobile device use to all adult inpatients at a large urban California teaching hospital over 2 dates (October 27, 2013 and November 11, 2013) to create a cross‐sectional view of mobile device use at a hospital that offers free wireless Internet (WiFi) and personal health records (Internet‐accessible individualized medical records). Average census was 447, and we excluded patients for: age under 18 years (98), admission for neurological problems (75), altered mental status (35), nonEnglish speaking (30), or unavailable if patients were not in their room after 2 attempts spaced 30 to 60 minutes apart (36), leaving 173 eligible. We performed descriptive statistics and unadjusted associations ([2] test) to explore patterns of mobile device use.

RESULTS

We enrolled 152 patients (88% response rate): 77 (51%) male, average age 53 years (1992 years), 84 (56%) white, 115 (75%) with Medicare or commercial insurance. We found 85 (56%) patients brought a smartphone, and 82/85 (95%) used it during their hospital stay. Additionally, 41 (27%) patients brought a tablet, and 29 (19%) brought a laptop; usage was 37/41 (90%) for tablets and 24/29 (83%) for laptops. One hundred three (68%) patients brought at least 1 mobile computing device (smartphone, tablet, laptop) during their hospital stay. Overall device usage was highest among oncology patients (85%) and lowest among medicine patients (54%) (Table 1). Device usage also varied by age (<65 years old: 79% vs 65 years old: 27%), insurance status (private/Medicare: 70% vs Medicaid/other: 59%), and race/ethnicity (white: 73% vs non‐white: 62%), although only age was statistically significant (P<0.01; all others >0.05).

| Total, N=152 | Medicine, n=39 | Surgery, n=47 | Oncology, n=34 | All Others, n=32* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Average age, y (range) | 53.2 (1992) | 55.7 (2092) | 51.7 (1979) | 51.2 (2377) | 53.9 (2584) |

| Medicare or commercial insurance | 75% (115) | 64% (25) | 87% (41) | 76% (26) | 72% (23) |

| Medicaid, other, or no insurance | 25% (37) | 36% (14) | 13% (6) | 24% (8) | 28% (9) |

| Non‐white race/ethnicity | 44% (68) | 56% (22) | 36% (17) | 38% (13) | 50%(16) |

| Female gender | 49% (75) | 49% (19) | 45% (21) | 47% (16) | 59% (19) |

| Device ownership/usage | |||||

| Own smartphone | 62% (94) | 54% (21) | 66% (31) | 74% (25) | 53% (17) |

| Brought smartphone | 55% (83) | 41% (16) | 60% (28) | 71% (24) | 48% (15) |

| Brought laptop | 19% (29) | 18% (7) | 11% (5) | 41% (14) | 10% (3) |

| Brought tablet | 27% (41) | 18% (7) | 26% (12) | 50% (17) | 16% (5) |

| Brought 1 above devices | 68% (103) | 54% (21) | 68% (32) | 85% (29) | 68% (21) |

| Ever used an app | 63% (95) | 51% (20) | 72% (34) | 79% (27) | 45% (14) |

| Ever used an app for health purposes | 22% (34) | 18% (7) | 21% (10) | 24% (8) | 29% (9) |

| Accessed PHR with mobile device | 31% (47) | 26% (10) | 26% (12) | 47% (16) | 29% (9) |

Of the patients with mobile devices (smartphone, tablet, laptop), 97/103 (94%) used them during their hospitalization and for a wide array of activities (Figure 1): 47/97 (48%) accessed their personal health record (PHR), and most of these patients (38/47, 81%) reported this improved their inpatient experience. Additionally, 43/97 (44%) patients used their mobile devices to search for information about doctors, conditions, or treatments; most of these patients (39/43, 91%) used Google to search for this information, and most 29/43 (67%) felt this information made them more confident in their care.

COMMENT

Over two‐thirds of patients in our study brought and used 1 or more mobile devices to the hospital. Despite this level of engagement with mobile devices, relatively few inpatients used their device to access their online PHR, which suggests information technology access is not the leading barrier to PHR access or mHealth engagement during hospitalization. In light of growing patient enthusiasm for PHRs,[6, 7] this represents an untapped opportunity to deliver personalized, patient‐centered care at the hospital bedside.

We also found that among the patients who did access their PHR on their mobile device, the vast majority (38/47, 81%) felt it improved their inpatient experience. Our PHR provides information such as test results and medications, but our survey suggests a number of patients look for health information, such as patient education tools, medication references, and provider information, outside of the PHR. For those patients, 29/43 (67%) felt these health‐related searches improved their experience. Although we did not ask patients why they used Web searches outside their PHR, we believe this suggests that patients desire more information than currently available via the PHR. Although this information might be difficult to incorporate into the PHR, at minimum, hospitals could develop mobile applications to provide patients with basic information about their providers and conditions. Beyond this, hospitals could develop or adopt mobile applications that align with strategic priorities such as improved physician‐provider communication, reduced hospital readmissions, and improved accuracy of medication reconciliation.

Our study has limitations. First, although we used a cross‐sectional, point‐in‐time approach to canvas the entire adult population in our hospital on 2 separate dates, our study was limited to 1 large urban hospital in California; device ownership and usage may vary in other settings. Second, although our hospital provides free WiFi, we did not assess whether patients experienced any connectivity issues that influenced their device usage patterns. Finally, we did not explore questions of access, ownership, and usage of mobile computing devices for family and friends who visited inpatients in our study. These questions are ripe for future research in this emerging area of mHeath.

In summary, our study suggests a role for hospitals to provide universal WiFi access to patients, and a role for both hospitals and healthcare providers to promote digital health programs. Our findings on mobile device use in the hospital are consistent with the growing popularity of mobile device usage nationwide. Patients are increasingly wired for new opportunities to both engage in their care and optimize their hospital experience through use of their mobile computing devices. Hospitals and providers should explore this potential for engagement, but may need to explore local trends in usage to target specific service lines and patient populations given differences in access and use.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge contributions by Christina Quist, MD, and Emily Gottenborg, MD, who assisted in data collection.

Disclosures: Data from this project were presented at the 2014 Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine, March 25, 2014 in Las Vegas, Nevada. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relative to this study. Dr. Ludwin, MD had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project by Drs. Ludwin and Greysen was supported by grants from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Partners in Care (Ronald Rankin Award) and the UCSF Mount Zion Health Fund. Dr. Greysen is also funded by a Pilot Award for Junior Investigators in Digital Health from the UCSF Dean's Office, Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (REAC). Additionally, Dr. Greysen receives career development support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)National Institute of Aging (NIA) through the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at UCSF Division of Geriatric Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA), a Career Development Award (1K23AG045338‐01), and the NIH‐NIA Loan Repayment Program.

Over 90% of Americans own mobile phones, and their use for internet access is rising rapidly (31% in 2009, 63% in 2013).[1] This has prompted growth in mobile health (mHealth) programs for outpatient settings,[2] and similar growth is anticipated for inpatient settings.[3] Hospitals and the healthcare systems they operate within are increasingly tied to patient experience scores (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, Press Ganey) for both reputation and reimbursement.[4, 5] As a result, hospitals will need to invest future resources in a consumer‐facing digital experience. Despite these trends, basic information on mobile device ownership and usage by hospitalized patients is limited. This knowledge is needed to guide successful mHealth approaches to engage patients in acute care settings.

METHODS

We administered a 27‐question survey about mobile device use to all adult inpatients at a large urban California teaching hospital over 2 dates (October 27, 2013 and November 11, 2013) to create a cross‐sectional view of mobile device use at a hospital that offers free wireless Internet (WiFi) and personal health records (Internet‐accessible individualized medical records). Average census was 447, and we excluded patients for: age under 18 years (98), admission for neurological problems (75), altered mental status (35), nonEnglish speaking (30), or unavailable if patients were not in their room after 2 attempts spaced 30 to 60 minutes apart (36), leaving 173 eligible. We performed descriptive statistics and unadjusted associations ([2] test) to explore patterns of mobile device use.

RESULTS

We enrolled 152 patients (88% response rate): 77 (51%) male, average age 53 years (1992 years), 84 (56%) white, 115 (75%) with Medicare or commercial insurance. We found 85 (56%) patients brought a smartphone, and 82/85 (95%) used it during their hospital stay. Additionally, 41 (27%) patients brought a tablet, and 29 (19%) brought a laptop; usage was 37/41 (90%) for tablets and 24/29 (83%) for laptops. One hundred three (68%) patients brought at least 1 mobile computing device (smartphone, tablet, laptop) during their hospital stay. Overall device usage was highest among oncology patients (85%) and lowest among medicine patients (54%) (Table 1). Device usage also varied by age (<65 years old: 79% vs 65 years old: 27%), insurance status (private/Medicare: 70% vs Medicaid/other: 59%), and race/ethnicity (white: 73% vs non‐white: 62%), although only age was statistically significant (P<0.01; all others >0.05).

| Total, N=152 | Medicine, n=39 | Surgery, n=47 | Oncology, n=34 | All Others, n=32* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Average age, y (range) | 53.2 (1992) | 55.7 (2092) | 51.7 (1979) | 51.2 (2377) | 53.9 (2584) |

| Medicare or commercial insurance | 75% (115) | 64% (25) | 87% (41) | 76% (26) | 72% (23) |

| Medicaid, other, or no insurance | 25% (37) | 36% (14) | 13% (6) | 24% (8) | 28% (9) |

| Non‐white race/ethnicity | 44% (68) | 56% (22) | 36% (17) | 38% (13) | 50%(16) |

| Female gender | 49% (75) | 49% (19) | 45% (21) | 47% (16) | 59% (19) |

| Device ownership/usage | |||||

| Own smartphone | 62% (94) | 54% (21) | 66% (31) | 74% (25) | 53% (17) |

| Brought smartphone | 55% (83) | 41% (16) | 60% (28) | 71% (24) | 48% (15) |