User login

Who Will Guard the Guardians? Preventing Drug Diversion in Hospitals

The patient safety field rightly focuses on identifying and addressing problems with systems of care. From the patient’s perspective, however, underlying systems issues might be less critical than another unspoken question: can I trust the people who are taking care of me? Last year, a popular podcast1 detailed the shocking story of Dallas neurosurgeon Christopher Duntsch, who was responsible for the death of two patients and severe injuries in dozens of other patients over two years. Although fellow surgeons had raised concerns about his surgical skill and professionalism almost immediately after he entered practice, multiple hospitals allowed him to continue operating until the Texas Medical Board revoked his license. Duntsch was ultimately prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment, in what is believed to be the first case of a physician receiving criminal punishment for malpractice.

Only a small proportion of clinicians repeatedly harm patients as Duntsch did, and the harm they cause accounts for only a small share of the preventable adverse events that patients experience. Understandably, cases of individual clinicians who directly harm patients tend to capture the public’s attention, as they vividly illustrate how vulnerable patients are when they entrust their health to a clinician. As a result, these cases have a significant effect on the patient’s trust in healthcare institutions.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Fan and colleagues2 describe the problem of controlled-substance diversion in hospitals and review the contributors and potential solutions to this issue. Their thorough and insightful review highlights a growing problem that is probably invisible to most hospitalists. Diversion of controlled substances can happen at any stage of the medication use process, from procurement to disposal and drugs can be diverted by healthcare workers, nonclinical staff, patients, and caregivers. Perhaps most concerning to hospitalists, diversion at the prescribing and administration stages can directly affect patient care. Strategies used to individualize pain control, such as using flexible dose ranges for opioids, can be manipulated to facilitate diversion at the expense of the patient’s suffering.

The review presents a comprehensive summary of safeguards against diversion at each stage of the medication use process and appropriately emphasizes system-level solutions. These include analyzing electronic health record data to identify unusual patterns of controlled substance use and developing dedicated diversion investigation teams. These measures, if implemented, are likely to be effective at reducing the risk of diversion. However, given the complexity of medication use, eliminating this risk is unrealistic. Opioids are used in more than half of all nonsurgical hospital admissions;3 although this proportion may be decreasing due to efforts to curb opioid overprescribing, many hospitalized patients still require opioids or other controlled substances for symptom control. The opportunity to divert controlled substances will always be present.

Eliminating the problem of drug diversion in hospitals will require addressing the individuals who divert controlled substances and strengthening the medication safety system. The term “impaired clinician” is used to describe clinicians who cannot provide competent care due to illness, mental health, or a substance-use disorder. In an influential 2006 commentary,Leape and Fromson made the case that physician performance impairment is often a symptom of underlying disorders, ranging from short-term, reversible issues (eg, an episode of burnout or depression) to long-term problems that can lead to permanent consequences (ie, physical illness or substance-use disorders).4 In this framework, a clinician who diverts controlled substances represents a particularly extreme example of the broader problem of physicians who are unable to perform their professional responsibilities.

Leape and Fromson called for proactively identifying clinicians at risk of performance failure and intervening to remediate or discipline them before patients are harmed. To accomplish this, they envisioned a system with three key characteristics:

- Fairness: All physicians should be subject to regular assessment, and the same standards should be applied to all physicians in the same discipline.

- Objectivity: Performance assessment should be based on objective data.

- Responsiveness: Physicians with performance issues should be identified and given feedback promptly, and provided with opportunities for remediation and assistance when underlying conditions are affecting their performance.

Some progress has been made toward this goal, especially in identifying underlying factors that predispose to performance problems.5 There is also greater awareness of underlying factors that may predispose to more subtle performance deterioration. The recent focus on burnout and well-being among physicians is long overdue, and the recent Charter on Physician Well-Being6 articulates important principles for healthcare organizations to address this epidemic. Substance-use disorder is a recognized risk factor for performance impairment. Physicians have a higher rate of prescription drug abuse and a similar overall rate of substance-use disorders compared to the general population. While there is limited research around the risk factors for drug diversion by physicians, qualitative studies7 of physicians undergoing treatment for substance-use disorders found that most began diverting drugs to manage physical pain, emotional or psychiatric distress, or acutely stressful situations. It is plausible that many burned out or depressed clinicians are turning to illicit substances to self-medicate increasing the risk of diversion.

However, 13 years after Leape and Fromson’s commentary was published, it is difficult to conclude that their vision has been achieved. Objectivity in physician performance assessment is still lacking, and most practicing physicians do not receive any form of regular assessment. This places the onus on members of the healthcare team to identify poorly performing colleagues before patients are harmed. Although nearly all states mandate that physicians report impaired colleagues to either the state medical board or a physician rehabilitation program, healthcare professionals are often reluctant8 to report colleagues with performance issues, and clinicians are also unlikely9 to self-report mental health or substance-use issues due to stigma and fear that their ability to practice may be at risk.

Even when colleagues do raise alarms—as was the case with Dr. Duntsch, who required treatment for a substance-use disorder during residency—existing regulatory mechanisms either lack evidence of effectiveness or are not applied consistently. State licensing boards play a crucial role in identifying problems with clinicians and have the power to authorize remediation or disciplinary measures. However, individual states vary widely10 in their likelihood of disciplining physicians for similar offenses. The board certification process is intended to ensure that only fully competent physicians can practice medicine independently. However, there is little evidence that the certification process ensures that clinicians maintain their skills, and significant controversy has accompanied efforts to revise the maintenance of certification process. The medical malpractice system aims to improve patient safety by ensuring compensation when patients are injured and by deterring substandard clinicians from practicing. Unfortunately, the system often fails to meet this goal, as malpractice claims are rarely filed even when patients are harmed due to negligent care.11

Given the widespread availability of controlled substances in hospitals, comprehensive solutions must incorporate the systems-based solutions proffered by Fan and colleagues and address individual clinicians (and staff) who divert drugs. These clinicians are likely to share some of the same risk factors as clinicians who cannot perform their professional responsibilities for other reasons. Major system changes are necessary to minimize the risk of short-term conditions that could affect physician performance (such as burnout) and develop robust methods to identify clinicians with longer-term issues affecting their performance (such as substance-use disorders).

Although individual clinician performance problems likely account for a small proportion of adverse events, these issues strike at the heart of the physician-patient relationship and have a profound impact on patients’ trust in the healthcare system. Healthcare organizations must maintain transparent and effective processes for addressing performance failures such as drug diversion by clinicians, even if these processes are rarely deployed.

Disclosures

The author does not have any conflict of interest to report.

1. “Dr. Death” (podcast). https://wondery.com/shows/dr-death/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

2. Fan M, Tscheng D, Hyland B, et al. Diversion of controlled drugs in hospitals: a scoping review of contributors and safeguards [published online ahead of printe June 12, 2019]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3228. PubMed

3. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2102. PubMed

4. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):107-115. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00008. PubMed

5. Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa1506137. PubMed

6. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

7. Merlo LJ, Singhakant S, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):349-353. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31829da074. PubMed

8. DesRoches CM, Fromson JA, Rao SR, et al. Physicians’ perceptions, preparedness for reporting, and experiences related to impaired and incompetent colleagues. JAMA. 2010;304(2):187-193. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.921. PubMed

9. Samuel L. Doctors fear mental health disclosure could jeopardize their licenses. STAT. October 16, 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/10/16/doctors-mental-health-licenses/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

10. Harris JA, Byhoff E. Variations by the state in physician disciplinary actions by US medical licensure boards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):200-208. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974. PubMed

11. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, et al. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. doi:10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002. PubMed

The patient safety field rightly focuses on identifying and addressing problems with systems of care. From the patient’s perspective, however, underlying systems issues might be less critical than another unspoken question: can I trust the people who are taking care of me? Last year, a popular podcast1 detailed the shocking story of Dallas neurosurgeon Christopher Duntsch, who was responsible for the death of two patients and severe injuries in dozens of other patients over two years. Although fellow surgeons had raised concerns about his surgical skill and professionalism almost immediately after he entered practice, multiple hospitals allowed him to continue operating until the Texas Medical Board revoked his license. Duntsch was ultimately prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment, in what is believed to be the first case of a physician receiving criminal punishment for malpractice.

Only a small proportion of clinicians repeatedly harm patients as Duntsch did, and the harm they cause accounts for only a small share of the preventable adverse events that patients experience. Understandably, cases of individual clinicians who directly harm patients tend to capture the public’s attention, as they vividly illustrate how vulnerable patients are when they entrust their health to a clinician. As a result, these cases have a significant effect on the patient’s trust in healthcare institutions.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Fan and colleagues2 describe the problem of controlled-substance diversion in hospitals and review the contributors and potential solutions to this issue. Their thorough and insightful review highlights a growing problem that is probably invisible to most hospitalists. Diversion of controlled substances can happen at any stage of the medication use process, from procurement to disposal and drugs can be diverted by healthcare workers, nonclinical staff, patients, and caregivers. Perhaps most concerning to hospitalists, diversion at the prescribing and administration stages can directly affect patient care. Strategies used to individualize pain control, such as using flexible dose ranges for opioids, can be manipulated to facilitate diversion at the expense of the patient’s suffering.

The review presents a comprehensive summary of safeguards against diversion at each stage of the medication use process and appropriately emphasizes system-level solutions. These include analyzing electronic health record data to identify unusual patterns of controlled substance use and developing dedicated diversion investigation teams. These measures, if implemented, are likely to be effective at reducing the risk of diversion. However, given the complexity of medication use, eliminating this risk is unrealistic. Opioids are used in more than half of all nonsurgical hospital admissions;3 although this proportion may be decreasing due to efforts to curb opioid overprescribing, many hospitalized patients still require opioids or other controlled substances for symptom control. The opportunity to divert controlled substances will always be present.

Eliminating the problem of drug diversion in hospitals will require addressing the individuals who divert controlled substances and strengthening the medication safety system. The term “impaired clinician” is used to describe clinicians who cannot provide competent care due to illness, mental health, or a substance-use disorder. In an influential 2006 commentary,Leape and Fromson made the case that physician performance impairment is often a symptom of underlying disorders, ranging from short-term, reversible issues (eg, an episode of burnout or depression) to long-term problems that can lead to permanent consequences (ie, physical illness or substance-use disorders).4 In this framework, a clinician who diverts controlled substances represents a particularly extreme example of the broader problem of physicians who are unable to perform their professional responsibilities.

Leape and Fromson called for proactively identifying clinicians at risk of performance failure and intervening to remediate or discipline them before patients are harmed. To accomplish this, they envisioned a system with three key characteristics:

- Fairness: All physicians should be subject to regular assessment, and the same standards should be applied to all physicians in the same discipline.

- Objectivity: Performance assessment should be based on objective data.

- Responsiveness: Physicians with performance issues should be identified and given feedback promptly, and provided with opportunities for remediation and assistance when underlying conditions are affecting their performance.

Some progress has been made toward this goal, especially in identifying underlying factors that predispose to performance problems.5 There is also greater awareness of underlying factors that may predispose to more subtle performance deterioration. The recent focus on burnout and well-being among physicians is long overdue, and the recent Charter on Physician Well-Being6 articulates important principles for healthcare organizations to address this epidemic. Substance-use disorder is a recognized risk factor for performance impairment. Physicians have a higher rate of prescription drug abuse and a similar overall rate of substance-use disorders compared to the general population. While there is limited research around the risk factors for drug diversion by physicians, qualitative studies7 of physicians undergoing treatment for substance-use disorders found that most began diverting drugs to manage physical pain, emotional or psychiatric distress, or acutely stressful situations. It is plausible that many burned out or depressed clinicians are turning to illicit substances to self-medicate increasing the risk of diversion.

However, 13 years after Leape and Fromson’s commentary was published, it is difficult to conclude that their vision has been achieved. Objectivity in physician performance assessment is still lacking, and most practicing physicians do not receive any form of regular assessment. This places the onus on members of the healthcare team to identify poorly performing colleagues before patients are harmed. Although nearly all states mandate that physicians report impaired colleagues to either the state medical board or a physician rehabilitation program, healthcare professionals are often reluctant8 to report colleagues with performance issues, and clinicians are also unlikely9 to self-report mental health or substance-use issues due to stigma and fear that their ability to practice may be at risk.

Even when colleagues do raise alarms—as was the case with Dr. Duntsch, who required treatment for a substance-use disorder during residency—existing regulatory mechanisms either lack evidence of effectiveness or are not applied consistently. State licensing boards play a crucial role in identifying problems with clinicians and have the power to authorize remediation or disciplinary measures. However, individual states vary widely10 in their likelihood of disciplining physicians for similar offenses. The board certification process is intended to ensure that only fully competent physicians can practice medicine independently. However, there is little evidence that the certification process ensures that clinicians maintain their skills, and significant controversy has accompanied efforts to revise the maintenance of certification process. The medical malpractice system aims to improve patient safety by ensuring compensation when patients are injured and by deterring substandard clinicians from practicing. Unfortunately, the system often fails to meet this goal, as malpractice claims are rarely filed even when patients are harmed due to negligent care.11

Given the widespread availability of controlled substances in hospitals, comprehensive solutions must incorporate the systems-based solutions proffered by Fan and colleagues and address individual clinicians (and staff) who divert drugs. These clinicians are likely to share some of the same risk factors as clinicians who cannot perform their professional responsibilities for other reasons. Major system changes are necessary to minimize the risk of short-term conditions that could affect physician performance (such as burnout) and develop robust methods to identify clinicians with longer-term issues affecting their performance (such as substance-use disorders).

Although individual clinician performance problems likely account for a small proportion of adverse events, these issues strike at the heart of the physician-patient relationship and have a profound impact on patients’ trust in the healthcare system. Healthcare organizations must maintain transparent and effective processes for addressing performance failures such as drug diversion by clinicians, even if these processes are rarely deployed.

Disclosures

The author does not have any conflict of interest to report.

The patient safety field rightly focuses on identifying and addressing problems with systems of care. From the patient’s perspective, however, underlying systems issues might be less critical than another unspoken question: can I trust the people who are taking care of me? Last year, a popular podcast1 detailed the shocking story of Dallas neurosurgeon Christopher Duntsch, who was responsible for the death of two patients and severe injuries in dozens of other patients over two years. Although fellow surgeons had raised concerns about his surgical skill and professionalism almost immediately after he entered practice, multiple hospitals allowed him to continue operating until the Texas Medical Board revoked his license. Duntsch was ultimately prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment, in what is believed to be the first case of a physician receiving criminal punishment for malpractice.

Only a small proportion of clinicians repeatedly harm patients as Duntsch did, and the harm they cause accounts for only a small share of the preventable adverse events that patients experience. Understandably, cases of individual clinicians who directly harm patients tend to capture the public’s attention, as they vividly illustrate how vulnerable patients are when they entrust their health to a clinician. As a result, these cases have a significant effect on the patient’s trust in healthcare institutions.

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Fan and colleagues2 describe the problem of controlled-substance diversion in hospitals and review the contributors and potential solutions to this issue. Their thorough and insightful review highlights a growing problem that is probably invisible to most hospitalists. Diversion of controlled substances can happen at any stage of the medication use process, from procurement to disposal and drugs can be diverted by healthcare workers, nonclinical staff, patients, and caregivers. Perhaps most concerning to hospitalists, diversion at the prescribing and administration stages can directly affect patient care. Strategies used to individualize pain control, such as using flexible dose ranges for opioids, can be manipulated to facilitate diversion at the expense of the patient’s suffering.

The review presents a comprehensive summary of safeguards against diversion at each stage of the medication use process and appropriately emphasizes system-level solutions. These include analyzing electronic health record data to identify unusual patterns of controlled substance use and developing dedicated diversion investigation teams. These measures, if implemented, are likely to be effective at reducing the risk of diversion. However, given the complexity of medication use, eliminating this risk is unrealistic. Opioids are used in more than half of all nonsurgical hospital admissions;3 although this proportion may be decreasing due to efforts to curb opioid overprescribing, many hospitalized patients still require opioids or other controlled substances for symptom control. The opportunity to divert controlled substances will always be present.

Eliminating the problem of drug diversion in hospitals will require addressing the individuals who divert controlled substances and strengthening the medication safety system. The term “impaired clinician” is used to describe clinicians who cannot provide competent care due to illness, mental health, or a substance-use disorder. In an influential 2006 commentary,Leape and Fromson made the case that physician performance impairment is often a symptom of underlying disorders, ranging from short-term, reversible issues (eg, an episode of burnout or depression) to long-term problems that can lead to permanent consequences (ie, physical illness or substance-use disorders).4 In this framework, a clinician who diverts controlled substances represents a particularly extreme example of the broader problem of physicians who are unable to perform their professional responsibilities.

Leape and Fromson called for proactively identifying clinicians at risk of performance failure and intervening to remediate or discipline them before patients are harmed. To accomplish this, they envisioned a system with three key characteristics:

- Fairness: All physicians should be subject to regular assessment, and the same standards should be applied to all physicians in the same discipline.

- Objectivity: Performance assessment should be based on objective data.

- Responsiveness: Physicians with performance issues should be identified and given feedback promptly, and provided with opportunities for remediation and assistance when underlying conditions are affecting their performance.

Some progress has been made toward this goal, especially in identifying underlying factors that predispose to performance problems.5 There is also greater awareness of underlying factors that may predispose to more subtle performance deterioration. The recent focus on burnout and well-being among physicians is long overdue, and the recent Charter on Physician Well-Being6 articulates important principles for healthcare organizations to address this epidemic. Substance-use disorder is a recognized risk factor for performance impairment. Physicians have a higher rate of prescription drug abuse and a similar overall rate of substance-use disorders compared to the general population. While there is limited research around the risk factors for drug diversion by physicians, qualitative studies7 of physicians undergoing treatment for substance-use disorders found that most began diverting drugs to manage physical pain, emotional or psychiatric distress, or acutely stressful situations. It is plausible that many burned out or depressed clinicians are turning to illicit substances to self-medicate increasing the risk of diversion.

However, 13 years after Leape and Fromson’s commentary was published, it is difficult to conclude that their vision has been achieved. Objectivity in physician performance assessment is still lacking, and most practicing physicians do not receive any form of regular assessment. This places the onus on members of the healthcare team to identify poorly performing colleagues before patients are harmed. Although nearly all states mandate that physicians report impaired colleagues to either the state medical board or a physician rehabilitation program, healthcare professionals are often reluctant8 to report colleagues with performance issues, and clinicians are also unlikely9 to self-report mental health or substance-use issues due to stigma and fear that their ability to practice may be at risk.

Even when colleagues do raise alarms—as was the case with Dr. Duntsch, who required treatment for a substance-use disorder during residency—existing regulatory mechanisms either lack evidence of effectiveness or are not applied consistently. State licensing boards play a crucial role in identifying problems with clinicians and have the power to authorize remediation or disciplinary measures. However, individual states vary widely10 in their likelihood of disciplining physicians for similar offenses. The board certification process is intended to ensure that only fully competent physicians can practice medicine independently. However, there is little evidence that the certification process ensures that clinicians maintain their skills, and significant controversy has accompanied efforts to revise the maintenance of certification process. The medical malpractice system aims to improve patient safety by ensuring compensation when patients are injured and by deterring substandard clinicians from practicing. Unfortunately, the system often fails to meet this goal, as malpractice claims are rarely filed even when patients are harmed due to negligent care.11

Given the widespread availability of controlled substances in hospitals, comprehensive solutions must incorporate the systems-based solutions proffered by Fan and colleagues and address individual clinicians (and staff) who divert drugs. These clinicians are likely to share some of the same risk factors as clinicians who cannot perform their professional responsibilities for other reasons. Major system changes are necessary to minimize the risk of short-term conditions that could affect physician performance (such as burnout) and develop robust methods to identify clinicians with longer-term issues affecting their performance (such as substance-use disorders).

Although individual clinician performance problems likely account for a small proportion of adverse events, these issues strike at the heart of the physician-patient relationship and have a profound impact on patients’ trust in the healthcare system. Healthcare organizations must maintain transparent and effective processes for addressing performance failures such as drug diversion by clinicians, even if these processes are rarely deployed.

Disclosures

The author does not have any conflict of interest to report.

1. “Dr. Death” (podcast). https://wondery.com/shows/dr-death/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

2. Fan M, Tscheng D, Hyland B, et al. Diversion of controlled drugs in hospitals: a scoping review of contributors and safeguards [published online ahead of printe June 12, 2019]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3228. PubMed

3. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2102. PubMed

4. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):107-115. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00008. PubMed

5. Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa1506137. PubMed

6. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

7. Merlo LJ, Singhakant S, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):349-353. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31829da074. PubMed

8. DesRoches CM, Fromson JA, Rao SR, et al. Physicians’ perceptions, preparedness for reporting, and experiences related to impaired and incompetent colleagues. JAMA. 2010;304(2):187-193. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.921. PubMed

9. Samuel L. Doctors fear mental health disclosure could jeopardize their licenses. STAT. October 16, 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/10/16/doctors-mental-health-licenses/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

10. Harris JA, Byhoff E. Variations by the state in physician disciplinary actions by US medical licensure boards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):200-208. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974. PubMed

11. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, et al. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. doi:10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002. PubMed

1. “Dr. Death” (podcast). https://wondery.com/shows/dr-death/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

2. Fan M, Tscheng D, Hyland B, et al. Diversion of controlled drugs in hospitals: a scoping review of contributors and safeguards [published online ahead of printe June 12, 2019]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3228. PubMed

3. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2102. PubMed

4. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):107-115. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00008. PubMed

5. Studdert DM, Bismark MM, Mello MM, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of physicians prone to malpractice claims. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):354-362. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa1506137. PubMed

6. Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PubMed

7. Merlo LJ, Singhakant S, Cummings SM, Cottler LB. Reasons for misuse of prescription medication among physicians undergoing monitoring by a physician health program. J Addict Med. 2013;7(5):349-353. doi: 10.1097/adm.0b013e31829da074. PubMed

8. DesRoches CM, Fromson JA, Rao SR, et al. Physicians’ perceptions, preparedness for reporting, and experiences related to impaired and incompetent colleagues. JAMA. 2010;304(2):187-193. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.921. PubMed

9. Samuel L. Doctors fear mental health disclosure could jeopardize their licenses. STAT. October 16, 2017. https://www.statnews.com/2017/10/16/doctors-mental-health-licenses/. Accessed May 16, 2019.

10. Harris JA, Byhoff E. Variations by the state in physician disciplinary actions by US medical licensure boards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26(3):200-208. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004974. PubMed

11. Studdert DM, Thomas EJ, Burstin HR, et al. Negligent care and malpractice claiming behavior in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):250-260. doi:10.1097/00005650-200003000-00002. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Training Residents in Hospital Medicine: The Hospitalist Elective National Survey

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Hospital medicine has become the fastest growing medicine subspecialty, though no standardized hospitalist-focused educational program is required to become a practicing adult medicine hospitalist.1 Historically, adult hospitalists have had little additional training beyond residency, yet, as residency training adapts to duty hour restrictions, patient caps, and increasing attending oversight, it is not clear if traditional rotations and curricula provide adequate preparation for independent practice as an adult hospitalist.2-5 Several types of training and educational programs have emerged to fill this potential gap. These include hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, early career faculty development programs (eg, Society of Hospital Medicine/ Society of General Internal Medicine sponsored Academic Hospitalist Academy), and hospitalist-focused resident rotations.6-10 These activities are intended to ensure that residents and early career physicians gain the skills and competencies required to effectively practice hospital medicine.

Hospital medicine fellowships, residency pathways, and faculty development have been described previously.6-8 However, the prevalence and characteristics of hospital medicine-focused resident rotations are unknown, and these rotations are rarely publicized beyond local residency programs. Our study aims to determine the prevalence, purpose, and function of hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs and explore the role these rotations have in preparing residents for a career in hospital medicine.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study involving the largest 100 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) internal medicine residency programs. We chose the largest programs as we hypothesized that these programs would be most likely to have the infrastructure to support hospital medicine focused rotations compared to smaller programs. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved this study.

Survey Development

We developed a study-specific survey (the Hospitalist Elective National Survey [HENS]) to assess the prevalence, structure, curricular goals, and perceived benefits of distinct hospitalist rotations as defined by individual resident programs. The survey prompted respondents to consider a “hospitalist-focused” rotation as one that is different from a traditional inpatient “ward” rotation and whose emphasis is on hospitalist-specific training, clinical skills, or career development. The 18-question survey (Appendix 1) included fixed choice, multiple choice, and open-ended responses.

Data Collection

Using publicly available data from the ACGME website (www.acgme.org), we identified the largest 100 medicine programs based on the total number of residents. This included programs with 81 or more residents. An electronic survey was e-mailed to the leadership of each program. In May 2015, surveys were sent to Residency Program Directors (PD), and if they did not respond after 2 attempts, then Associate Program Directors (APD) were contacted twice. If both these leaders did not respond, then the survey was sent to residency program administrators or Hospital Medicine Division Chiefs. Only one survey was completed per site.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize quantitative data. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions about the goals, strengths, and design of rotations were analyzed using thematic analysis.11 During analysis, we iteratively developed and refined codes that identified important concepts that emerged from the data. Two members of the research team trained in qualitative data analysis coded these data independently (SL & JH).

RESULTS

Eighty-two residency program leaders (53 PD, 19 APD, 10 chiefs/admin) responded to the survey (82% total response rate). Among all responders, the prevalence of hospitalist-focused rotations was 50% (41/82). Of these 41 rotations, 85% (35/41) were elective rotations and 15% (6/41) were mandatory rotations. Hospitalist rotations ranged in existence from 1 to 15 years with a mean duration of 4.78 years (S.D. 3.5).

Of the 41 programs that did not have a hospital medicine-focused rotation, the key barriers identified were a lack of a well-defined model (29%), low faculty interest (15%), low resident interest (12%), and lack of funding (5%). Despite these barriers, 9 of these 41 programs (22%) stated they planned to start a rotation in the future – of which, 3 programs (7%) planned to start a rotation within the year.

Most programs with rotations (39/41, 95%) reported that their hospitalist rotation filled at least one gap in traditional residency curriculum. The most frequently identified gaps the rotation filled included: allowing progressive clinical autonomy (59%, 24/41), learning about quality improvement and high value care (41%, 17/41), and preparing to become a practicing hospitalist (39%, 16/41). Most respondents (66%, 27/41) reported that the rotation helped to prepare trainees for their first year as an attending.

DISCUSSION

The Hospital Elective National Survey provides insight into a growing component of hospitalist-focused training and preparation. Fifty percent of ACGME residency programs surveyed in this study had a hospitalist-focused rotation. Rotation characteristics were heterogeneous, perhaps reflecting both the homegrown nature of their development and the lack of national study or data to guide what constitutes an “ideal” rotation. Common functions of rotations included providing career mentorship and allowing for trainees to get experience “being a hospitalist.” Other key elements of the rotations included providing additional clinical autonomy and teaching material outside of traditional residency curricula such as quality improvement, patient safety, billing, and healthcare finances.

Prior research has explored other training for hospitalists such as fellowships, pathways, and faculty development.6-8 A hospital medicine fellowship provides extensive training but without a practice requirement in adult medicine (as now exists in pediatric hospital medicine), the impact of fellowship training may be limited by its scale.12,13 Longitudinal hospitalist residency pathways provide comprehensive skill development and often require an early career commitment from trainees.7 Faculty development can be another tool to foster career growth, though requires local investment from hospitalist groups that may not have the resources or experience to support this.8 Our study has highlighted that hospitalist-focused rotations within residency programs can train physicians for a career in hospital medicine. Hospitalist and residency leaders should consider that these rotations might be the only hospital medicine-focused training that new hospitalists will have. Given the variable nature of these rotations nationally, developing standards around core hospitalist competencies within these rotations should be a key component to career preparation and a goal for the field at large.14,15

Our study has limitations. The survey focused only on internal medicine as it is the most common training background of hospitalists; however, the field has grown to include other specialties including pediatrics, neurology, family medicine, and surgery. In addition, the survey reviewed the largest ACGME Internal Medicine programs to best evaluate prevalence and content—it may be that some smaller programs have rotations with different characteristics that we have not captured. Lastly, the survey reviewed the rotations through the lens of residency program leadership and not trainees. A future survey of trainees or early career hospitalists who participated in these rotations could provide a better understanding of their achievements and effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

We anticipate that the demand for hospitalist-focused training will continue to grow as more residents in training seek to enter the specialty. Hospitalist and residency program leaders have an opportunity within residency training programs to build new or further develop existing hospital medicine-focused rotations. The HENS survey demonstrates that hospitalist-focused rotations are prevalent in residency education and have the potential to play an important role in hospitalist training.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 – The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1009-1011. PubMed

2. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1110-1115. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008; 5:436-441. PubMed

4. Plauth WH 3rd, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists’ perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001; 15;111:247-254. PubMed

5. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, Harman S, Nallamshetty, S, Rogers A, Harrington R, Ahuja N. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11:646-649. PubMed

6. Ranji, SR, Rosenman, DJ, Amin, AN, Kripalani, S. Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1-7. PubMed

7. Sweigart JR, Tad-Y D, Kneeland P, Williams MV, Glasheen JJ. Hospital medicine resident training tracks: developing the hospital medicine pipeline. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:173-176. PubMed

8. Sehgal NL, Sharpe BA, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. Investing in the future: building an academic hospitalist faculty development program. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:161-166. PubMed

9. Academic Hospitalist Academy. Course Description, Objectives and Society Sponsorship. Available at: https://academichospitalist.org/. Accessed August 23, 2017.

10. Amin AN. A successful hospitalist rotation for senior medicine residents. Med Educ. 2003;37:1042. PubMed

11. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77-101.

12. American Board of Medical Specialties. ABMS Officially Recognizes Pediatric Hospital Medicine Subspecialty Certification Available at: http://www.abms.org/news-events/abms-officially-recognizes-pediatric-hospital-medicine-subspecialty-certification/. Accessed August 23, 2017. PubMed

13. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

14. Dressler DD, Pistoria MJ, Budnitz TL, McKean SC, Amin AN. Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006; 1 Suppl 1:48-56. PubMed

15. Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M. Updating the core competencies in hospital medicine – 2017 revision: introduction and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2017;4:283-287. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

PCP Communication at Discharge

Transitions of care from hospital to home are high‐risk times for patients.[1, 2] Increasing complexity of hospital admissions and shorter lengths of stay demand more effective coordination of care between hospitalists and outpatient clinicians.[3, 4, 5] Inaccurate, delayed, or incomplete clinical handoversthat is, transfer of information and professional responsibility and accountability[6]can lead to patient harm, and has been recognized as a key cause of preventable morbidity by the World Health Organization and The Joint Commission.[6, 7, 8] Conversely, when done effectively, transitions can result in improved patient health outcomes, reduced readmission rates, and higher patient and provider satisfaction.3

Previous studies note deficits in communication at discharge and primary care provider (PCP) dissatisfaction with discharge practices.[4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13] In studies at academic medical centers, there were low rates of direct communication between inpatient and outpatient providers, mainly because of providers' belief that the discharge summary was adequate and the presence of significant barriers to direct communication.[14, 15] However, studies have shown that discharge summaries often omit critical information, and often are not available to PCPs in a timely manner.[10, 11, 12, 16] In response, the Society of Hospital Medicine developed a discharge checklist to aide in standardization of safe discharge practices.[1, 5] Discharge summary templates further attempt to improve documentation of patients' hospital courses. An electronic medical record (EMR) system shared by both inpatient and outpatient clinicians should impart several advantages: (1) automated alerts provide timely notification to PCPs regarding admission and discharge, (2) discharge summaries are available to the PCP as soon as they are written, and (3) all patient information pertaining to the hospitalization is available to the PCP.

Although it is plausible that shared EMRs should facilitate transitions of care by streamlining communication between hospitalists and PCPs, guidelines on format and content of PCP communication at discharge in the era of a shared EMR have yet to be defined. In this study, we sought to understand current discharge communication practices and PCP satisfaction within a shared EMR at our institution, and to identify key areas in which communication can be improved.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

We surveyed all resident and attending PCPs (n=124) working in the Division of General Internal Medicine (DGIM) Outpatient Practice at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In June 2012, the outpatient and inpatient practices of UCSF transitioned from having separate medical record systems to a shared EMR (Epic Systems Corp., Verona, WI) where all informationboth inpatient and outpatientis accessible among healthcare professionals. The EMR provides automated notifications of admission and discharge to PCPs, allows for review of inpatient notes, labs, and studies, and immediate access to templated discharge summaries (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article). The EMR also enables secure communication between clinicians. At our institution, over 90% of discharge summaries are completed within 24 hours of discharge.[17]

Study Design and Analysis

We developed a survey about the discharge communication practices of inpatient medicine patients based on a previously described survey in the literature (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).[9] The anonymous, 17‐question survey was electronically distributed to resident and attending PCPs at the DGIM practice. The survey was designed to determine: (1) overall PCP satisfaction with current communication practices from the inpatient team at patient discharge, (2) perceived adequacy of automatic discharge notifications, and (3) perception of the types of patients and hospitalizations requiring additional high‐touch communication at discharge.

We analyzed results of our survey using descriptive statistics. Differences in resident and attending responses were analyzed by 2tests.

RESULTS

Seventy‐five of 124 (60%) clinicians (46% residents, 54% attendings) completed the survey. Thirty‐nine (52%) PCPs were satisfied or very satisfied with communication at patient discharge. Although most reported receiving automated discharge notifications (71%), only 39% felt that the notifications plus the discharge summaries were adequate communication for safe transition of care from hospital to community. Fifty‐one percent desired direct contact beyond a discharge summary. There were no differences in preferences on discharge communication between resident and attending PCPs (P>0.05).

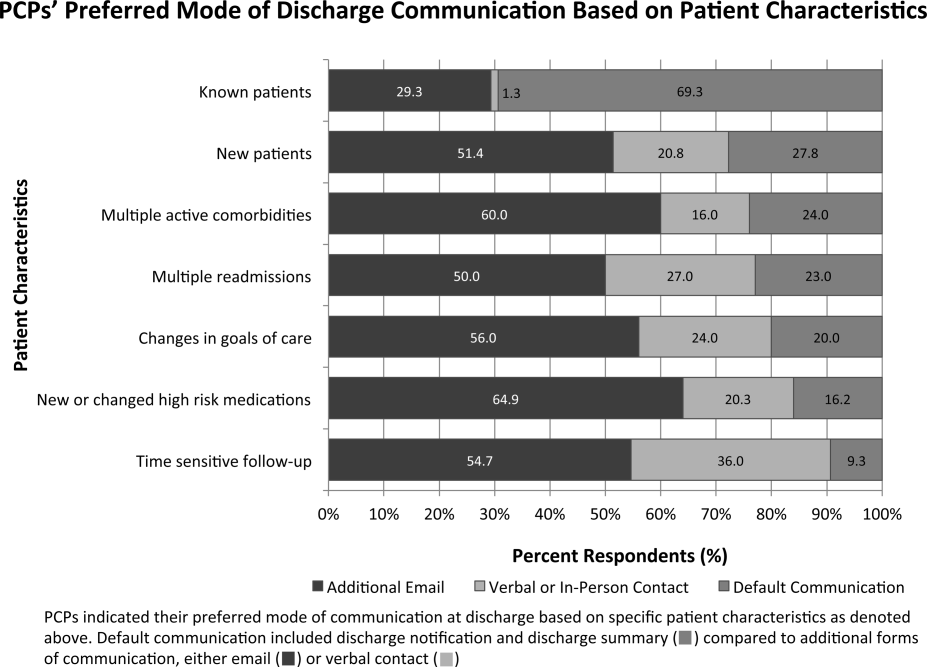

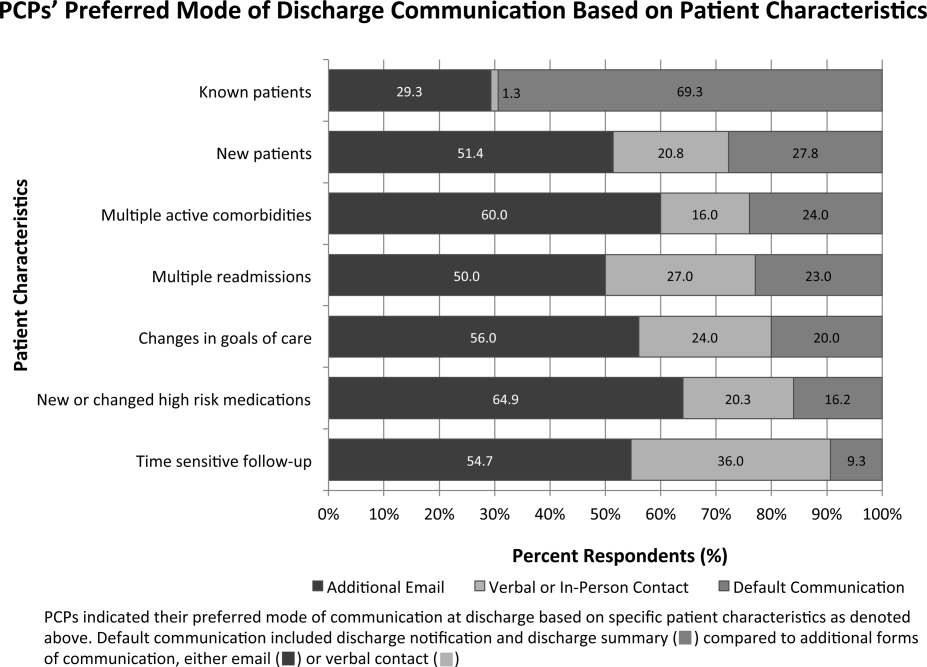

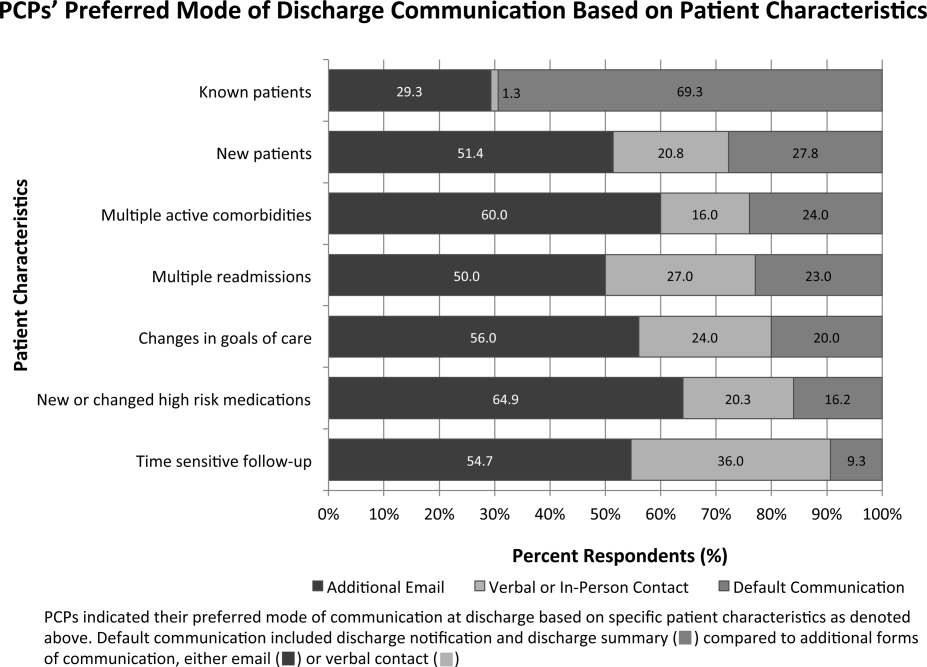

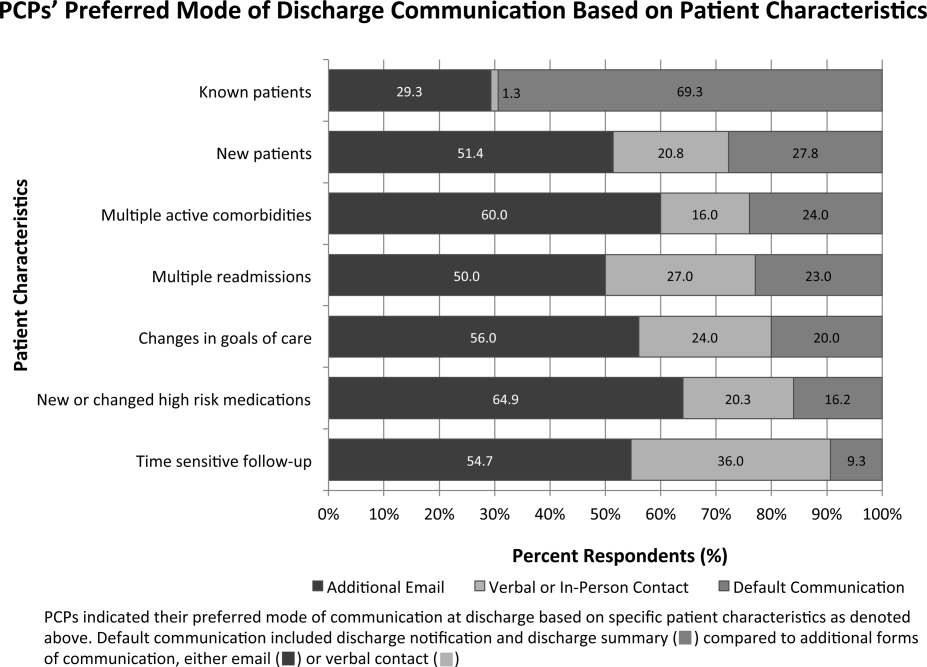

Over three‐fourths of PCPs surveyed preferred that for patients with complex hospitalizations (multiple readmissions, multiple active comorbidities, goals of care changes, high‐risk medication changes, time‐sensitive follow‐up needs), an additional e‐mail or verbal communication was needed to augment the information in the discharge summary (Figure 1). Only 31% reported receiving such communication.

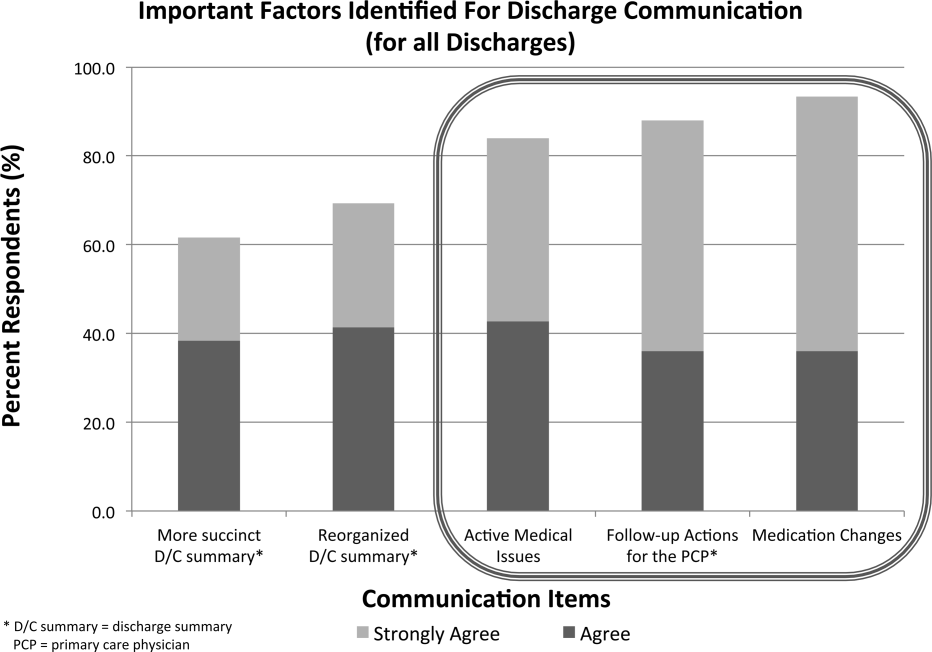

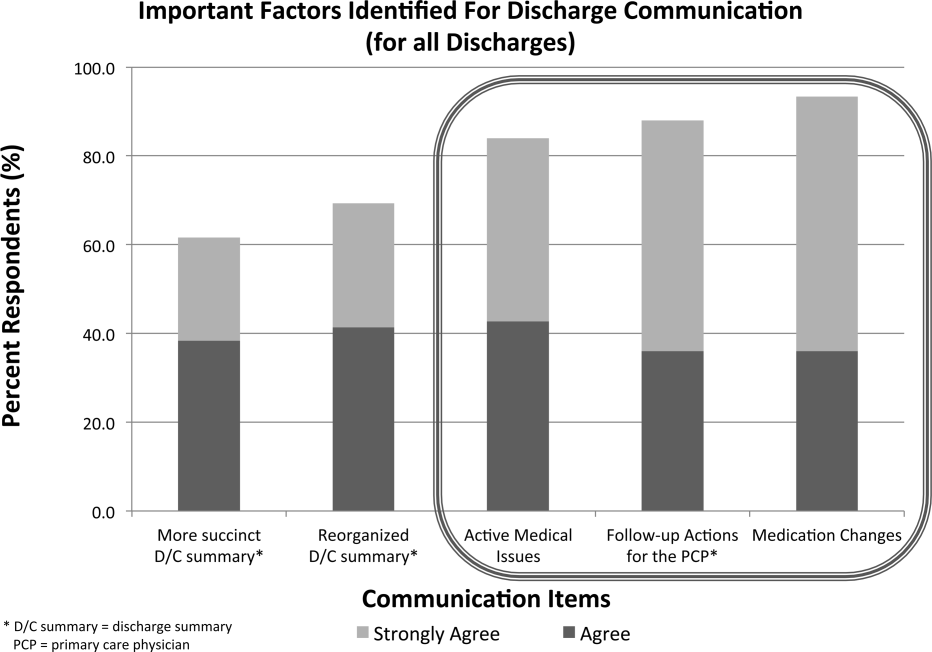

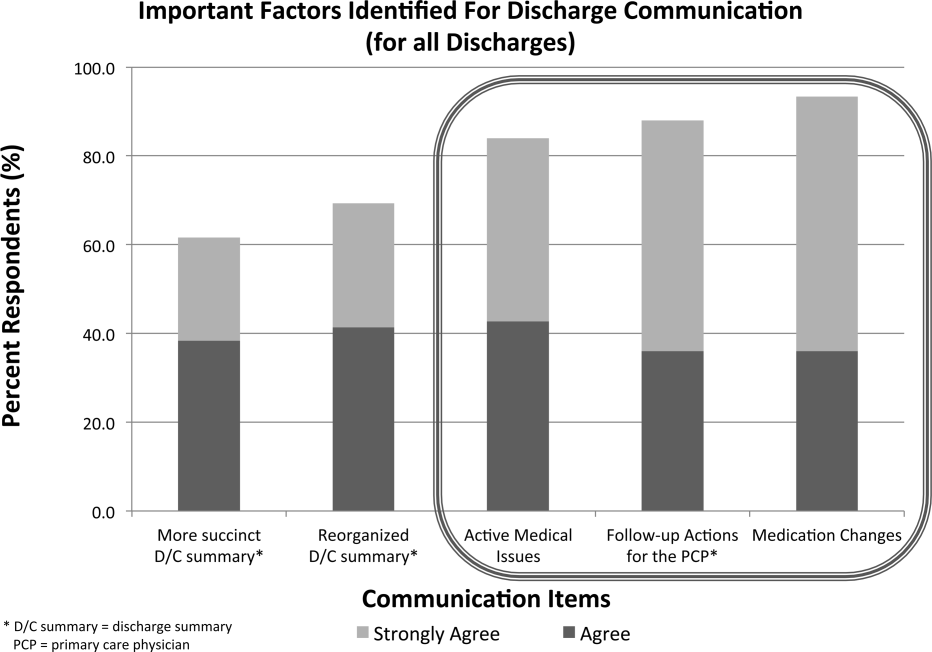

When asked about important items to communicate for safer transitions of care, PCPs reported finding the following elements most critical: (1) medication changes (93%), (2) follow‐up actions for the PCP (88%), and (3) active medical issues (84%) (Figure 2).

CONCLUSIONS

In the era of shared EMRs, real‐time access to medication lists, pending test results, and discharge summaries should facilitate care transitions at discharge.[18, 19] We conducted a study to determine PCP perceptions of discharge communication after implementation of a shared EMR. We found that although PCPs largely acknowledged timely receipt of automated discharge notifications and discharge summaries, the majority of PCPs felt that most discharges required additional communication to ensure safe transition of care.

Guidelines for discharge communication emphasize timely communication with the PCP, primarily through discharge summaries containing key safety elements.[1, 5, 10] At our institution, we have improved the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries according to guideline recommendations,[17] and conducted quality improvement projects to improve rates of direct communication with PCPs.[9] In addition, the shared EMR provides automated notifications to PCPs when their patients are discharged. Despite these interventions, our survey shows that PCP satisfaction with discharge communication is still inadequate. PCPs desired direct communication that highlights active medical issues, medication changes, and specific follow‐up actions. Although all of these topics are included in our discharge summary template (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article), it is possible that the templated discharge summaries lend themselves to longer documents and information overload, as prior studies have documented the desire for more succinct discharge summaries.[18] We also found that automated notifications of discharge were less reliable and useful for PCPs than anticipated. There were several reasons for this: (1) discharge summaries sometimes were sent to PCPs uncoupled from the discharge notification, (2) there were errors with the generation and delivery of automated messages at the rollout of the new system, and (3) PCPs received many other automated system messages, meaning that discharge notifications could be easily missed. These factors all likely contribute to PCPs' desire for high‐touch communication that highlights the most salient aspects of each patient's hospitalization. It is also possible that automated notifications and depersonalized discharge summaries create distance and a less‐collaborative feeling to patient care. PCPs want more direct communication, and desire to play a more active role in inpatient management, especially for complex hospitalizations.[18] This emphasis on direct communication resonates with previous studies conducted before shared EMRs existed.[9, 12, 19]

Our study had several limitations. First, because this is a single‐institution study at a tertiary care academic setting, the results may not be generalizable to all shared EMR settings, and may not reflect all the challenges of communication with the wider community of outpatient providers. One can postulate that inpatient and outpatient clinician relationships are stronger in an academic setting than in other more disparate environments, where direct communication may happen even less frequently. Of note, our low rates of direct communication are consistent with other single‐ and multi‐institution studies, suggesting that our findings are generalizable.[14, 15] Second, our survey is limited in its ability to distinguish those patients who require high‐touch communication and those who do not. Third, although we have used the survey to assess PCP satisfaction in previous studies, it is not a validated instrument, and therefore we cannot reliably say that increasing direct PCP communication would increase their satisfaction around discharge. Last, the PCP‐reported rates of discharge communication are subjective and may be influenced by recall bias. We did not have a systematic way to confirm the actual rates of communication at discharge, which could have occurred through EMR messages, e‐mails, phone calls, or pages.

Although a shared EMR allows for real‐time access to patient data, it does not eliminate PCPs' desire for direct 2‐way dialogue at discharge, especially for complex patients. Key information desired in such communication should include active medical issues, medication changes, and follow‐up needs, which is consistent with prior studies. Standardizing this direct communication process in an efficient way can be challenging. Further elucidation of PCP preferences around which patients necessitate higher‐level communication and preferred methods and timing of communication is needed, as well as determining the most efficient and effective method for hospitalists to provide such communication. Improving communication between hospitalists and PCPs requires not just the presence of a shared EMR, but additional, systematic efforts to engage both inpatient and outpatient clinicians in collaborative care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , et al. Development of a checklist of safe discharge practices for hospital patients. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):444–449.

- , , , , The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Improving patient handovers from hospital to primary care: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(6):417–428.

- , , , , “Did I do as best as the system would let me?” Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354−660.

- , , , , Improving measurement in clinical handover. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:272–277.

- World Health Organization. Patient safety: action on patient safety: high 5s. 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Hand‐off communications. 2012. Available at: http://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/projects/detail.aspx?Project=1. Accessed January 28, 2015.

- , , , et al. The effect of a resident‐led quality improvement project on improving communication between hospital‐based and outpatient physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(6):472–479.

- , , , Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , , , , , Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9B):15S–20S.