User login

Recertification: The FPHM option

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

ABIM now offers increased flexibility

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

Everyone always told me that my time in residency would fly by, and the 3 years of internal medicine training really did seem to pass in just a few moments. Before I knew it, I had passed my internal medicine boards and practiced hospital medicine at an academic medical center.

One day last fall, I received notice from the American Board of Internal Medicine that it was time to recertify. I was surprised – had it already been 10 years? What did I have to do to maintain my certification?

As I investigated what it would take to maintain certification, I discovered that the recertification process provided more flexibility, compared with original board certification. I now had the option to recertify in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM). Beginning in 2014, ABIM offered hospitalists, or internists whose clinical practice is mainly in the inpatient setting, the option to recertify in internal medicine, but with the designation that highlighted their clinical practice in the inpatient setting.

The first step in recertification for me was deciding to recertify with the focus in hospital medicine or maintain the traditional internal medicine certification. I talked with several colleagues who are also practicing hospitalists and weighed their reasons for opting for FPHM. Ultimately, my decision to pursue a recertification with a focus in hospital medicine relied on three factors: First, my clinical practice since completing residency was exclusively in the inpatient setting. Day in and day out, I care for patients who are acutely ill and require inpatient medical care. Second, I wanted my board certification to reflect what I consider to be my area of clinical expertise, which is inpatient adult medicine. Pursuing the FPHM would provide that recognition. Finally, I wanted to study and be tested on topics that I could utilize in my day-to-day practice. Because I exclusively practiced hospital medicine since graduation, areas of clinical internal medicine that I did not frequently encounter in my daily practice became less accessible in my knowledge base.

The next step then was to enter the FPHM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program.

The ABIM requires two attestations to verify that I met the requirements to be a hospitalist. First was a self-attestation confirming at least 3 years of unsupervised inpatient care practice experience, and meeting patient encounter thresholds in the inpatient setting. The second attestation was from a “Senior Hospital Officer” confirming the information in the self-attestation was accurate.

Once entered into the program and having an unrestricted medical license to practice, I had to complete the remaining requirements of earning MOC points and then passing a knowledge-based assessment. I had to accumulate a total of 100 MOC points in the past 5 years, which I succeeded in doing through participating in quality improvement projects, recording CME credits, studying for the exam, and even taking the exam. I could track my point totals through the ABIM Physician Portal, which updated my point tally automatically for activities that counted toward MOC, such as attending SHM’s annual conference.

The final component was to pass the knowledge assessment, the dreaded exam. In 2018, I had the option to take the 10-year FPHM exam or do a general internal medicine Knowledge Check-In. Beginning in 2020, candidates will be able to sit for either the 10-year Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine exam or begin the Hospital Medicine Knowledge Check-In pathway. I had already decided to pursue FPHM and began to prepare to sit for an exam. I scheduled my exam through the ABIM portal at a local testing center.

The exam was scheduled for a full day, consisting of four sections broken up by a lunch break and section breaks. Specifically, the 220 single best answer, multiple-choice exam covered diagnosis, testing, treatment decisions, epidemiology, and basic science content through patient scenarios that reflected the scope of practice of a hospitalist. The ABIM provided an exam blueprint that detailed the specific clinical topics and the likelihood that a question pertaining to that topic would show up on the exam. Content was described as high, medium, or low importance and the number of questions related to the content was 75% for high importance, no more than 25% for medium importance, and no questions for low-importance content. In addition, content was distributed in a way that was reflective of my clinical practice as a hospitalist: 63.5% inpatient and traditional care; 6.5% palliative care; 15% consultative comanagement; and 15% quality, safety, and clinical reasoning.

Beginning 6 months prior to my scheduled exam, I purchased two critical resources to guide my studying efforts: the SHM Spark Self-Assessment Tool and the American College of Physicians Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program to review subject matter content and also do practice questions.

The latest version of SHM’s program, Spark Edition 2, provides updated questions and resources tailored to the hospital medicine exams. I appreciated the ability to answer questions online, as well as on my phone so I could do questions on the go. Moreover, I was able to track which content areas were stronger or weaker for me, and focus attention on areas that needed more work. Importantly, the questions I answered using the Spark self-assessment tool closely aligned with the subject matter I encountered in the exam, as well as the clinical cases I encounter every day in my practice.

While the day-long exam was challenging, I was gratified to receive notice from the ABIM that I had successfully recertified in internal medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine!

Dr. Tad-y is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and associate vice chair of quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado.

Hospital medicine resident training tracks: Developing the hospital medicine pipeline

The field of hospital medicine (HM) is rapidly expanding in the areas of clinical medicine, administration, and quality improvement (QI).1 Emerging with this growth is a gap in the traditional internal medicine (IM) training and skills needed to be effective in HM.1,2 These skills include clinical and nonclinical aptitudes, such as process improvement, health care economics, and leadership.1-3 However, resident education on these topics must compete with other required curricular content in IM residency training.2,4 Few IM residencies offer focused HM training that emphasizes key components of successful HM careers.3,5

Within the past decade, designated HM tracks within IM residency programs have been proposed as a potential solution. Initially, calls for such tracks focused on gaps in the clinical competencies required of hospitalists.1 Tracks have since evolved to also include skills required to drive high-value care, process improvement, and scholarship. Designated HM tracks address these areas through greater breadth of curricula, additional time for reflection, participation in group projects, and active application to clinical care.4 We conducted a study to identify themes that could inform the ongoing evolution of dedicated HM tracks.

METHODS

Programs were initially identified through communication among professional networks. The phrases hospital medicine residency track and internal medicine residency hospitalist track were used in broader Google searches, as there is no database of such tracks. Searches were performed quarterly during the 2015–2016 academic year. The top 20 hits were manually filtered to identify tracks affiliated with major academic centers. IM residency program websites provided basic information for programs with tracks. We excluded tracks focused entirely on QI6 because, though a crucial part of HM, QI training alone is probably insufficient for preparing residents for success as hospitalists on residency completion. Similarly, IM residencies with stand-alone HM clinical rotations without longitudinal HM curricula were excluded.

Semistructured interviews with track directors were conducted by e-mail or telephone for all tracks except one, the details of which are published.7 We tabulated data and reviewed qualitative information to identify themes among the different tracks. As this study did not involve human participants, Institutional Review Board approval was not needed.

RESULTS

We identified 11 HM residency training programs at major academic centers across the United States: Cleveland Clinic, Stanford University, Tulane University, University of California Davis, University of California Irvine, University of Colorado, University of Kentucky, University of Minnesota, University of New Mexico, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Wake Forest University (Table 1). We reviewed the websites of about 10 other programs, but none suggested existence of a track. Additional programs contacted reported no current track.

Track Participants and Structure

HM tracks mainly target third-year residents (Table 1). Some extend into the second year of residency, and 4 have opportunities for intern involvement, including a separate match number at Colorado. Tracks accept up to 12 residents per class. Two programs, at Colorado and Virginia, are part of IM programs in which all residents belong to a track (eg, HM, primary care, research).

HM track structures vary widely and are heavily influenced by the content delivery platforms of their IM residency programs. Several HM track directors emphasized the importance of fitting into existing educational frameworks to ensure access to residents and to minimize the burden of participation. Four programs deliver the bulk of their nonclinical content in dedicated blocks; 6 others use brief recurring sessions to deliver smaller aliquots longitudinally (Table 1). The number of protected hours for content delivery ranges from 10 to more than 40 annually. All tracks use multiple content delivery modes, including didactic sessions and journal clubs. Four tracks employ panel discussions to explore career options within HM. Several also use online platforms, including discussions, readings, and modules.

Quality Improvement

The vast majority of curricula prominently feature experiential QI project involvement (Table 2). These mentored longitudinal projects allow applied delivery of content, such as QI methods and management skills. Four tracks use material from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.8 Several also offer dedicated QI rotations that immerse residents in ongoing QI efforts.

Institutional partnerships support these initiatives at several sites. The Minnesota track is a joint venture of the university and Regions Hospital, a nonprofit community hospital. The Virginia track positions HM residents to lead university-wide interdisciplinary QI teams. For project support, the Colorado and Kentucky tracks partner with local QI resources—the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Efficiency at Colorado and the Office of Value and Innovation in Healthcare Delivery at Kentucky.

Health Care Economics and Value

Many programs leverage the rapidly growing emphasis on health care “value” as an opportunity for synergy between IM programs and HM tracks. Examples include involving residents in efforts to improve documentation or didactic instruction on topics such as health care finance. The New Mexico and Wake Forest tracks offer elective rotations on health care economics. Several track directors mentioned successfully expanding curricula on health care value from the HM track into IM residency programs at large, providing a measurable service to the residency programs while ensuring content delivery and freeing up additional time for track activities.

Scholarship and Career Development

Most programs provide targeted career development for residents. Six tracks provide sessions on job procurement skills, such as curriculum vitae preparation and interviewing (Table 2). Many also provide content on venues for disseminating scholarly activity. The Colorado, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Tulane programs feature content on abstract and poster creation. Leadership development is addressed in several tracks through dedicated track activities or participation in discrete, outside-track events. Specifically, Colorado offers a leadership track for residents interested in hospital administration, Cleveland has a leadership journal club, Wake Forest enrolls HM residents in leadership training available through the university, and Minnesota sends residents to the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy (Table 2).

Clinical Rotations

Almost all tracks include a clinical rotation, typically pairing residents directly with hospitalist attendings to encourage autonomy and mentorship. Several also offer elective rotations in various disciplines within HM (Table 2). The Kentucky and Virginia tracks incorporate working with advanced practice providers into their practicums. The Cleveland, Minnesota, Tulane, and Virginia tracks offer HM rotations in community hospitals or postacute settings.

HM rotations also pair clinical experiences with didactic education on relevant topics (eg, billing and coding). The Cleveland, Minnesota, and Virginia tracks developed clinical rotations reflecting the common 7-on and 7-off schedule with nonclinical obligations, such as seminars linking specific content to clinical experiences, during nonclinical time.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation into the current state of HM training found that HM track curricula focus largely on QI, health care economics, and professional development. This focus likely developed in response to hospitalists’ increasing engagement in related endeavors. HM tracks have dynamic and variable structures, reflecting an evolving field and the need to fit into existing IM residency program structures. Similarly, the content covered in HM tracks is tightly linked to perceived opportunities within IM residency curricula. The heterogeneity of content suggests the breadth and ambiguity of necessary competencies for aspiring hospitalists. One of the 11 tracks has not had any residents enroll within the past few years—a testament to the continued effort necessary to sustain such tracks, including curricular updates and recruiting. Conversely, many programs now share track content with the larger IM residency program, suggesting HM tracks may be near the forefront of medical education in some areas.

Our study had several limitations. As we are unaware of any databases of HM tracks, we discussed tracks with professional contacts, performed Internet searches, and reviewed IM residency program websites. Our search, however, was not exhaustive; despite our best efforts, we may have missed or mischaracterized some track offerings. Nevertheless, we think that our analysis represents the first thorough compilation of HM tracks and that it will be useful to institutions seeking to create or enhance HM-specific training.

As the field continues to evolve, we are optimistic about the future of HM training. We suspect that HM residency training tracks will continue to expand. More work is needed so these tracks can adjust to the changing HM and IM residency program landscapes and supply well-trained physicians for the HM workforce.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank track directors Alpesh Amin, David Gugliotti, Rick Hilger, Karnjit Johl, Nasir Majeed, Georgia McIntosh, Charles Pizanis, and Jeff Wiese for making this study possible.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1931]. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1110-1115. PubMed

2. Arora V, Guardiano S, Donaldson D, Storch I, Hemstreet P. Closing the gap between internal medicine training and practice: recommendations from recent graduates. Am J Med. 2005;118(6):680-685. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):436-441. PubMed

4. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

5. Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728. PubMed

6. Patel N, Brennan PJ, Metlay J, Bellini L, Shannon RP, Myers JS. Building the pipeline: the creation of a residency training pathway for future physician leaders in health care quality. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):185-190. PubMed

7. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, et al. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):646-649. PubMed

8. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. http://www.ihi.org. Accessed December 15, 2015.

The field of hospital medicine (HM) is rapidly expanding in the areas of clinical medicine, administration, and quality improvement (QI).1 Emerging with this growth is a gap in the traditional internal medicine (IM) training and skills needed to be effective in HM.1,2 These skills include clinical and nonclinical aptitudes, such as process improvement, health care economics, and leadership.1-3 However, resident education on these topics must compete with other required curricular content in IM residency training.2,4 Few IM residencies offer focused HM training that emphasizes key components of successful HM careers.3,5

Within the past decade, designated HM tracks within IM residency programs have been proposed as a potential solution. Initially, calls for such tracks focused on gaps in the clinical competencies required of hospitalists.1 Tracks have since evolved to also include skills required to drive high-value care, process improvement, and scholarship. Designated HM tracks address these areas through greater breadth of curricula, additional time for reflection, participation in group projects, and active application to clinical care.4 We conducted a study to identify themes that could inform the ongoing evolution of dedicated HM tracks.

METHODS

Programs were initially identified through communication among professional networks. The phrases hospital medicine residency track and internal medicine residency hospitalist track were used in broader Google searches, as there is no database of such tracks. Searches were performed quarterly during the 2015–2016 academic year. The top 20 hits were manually filtered to identify tracks affiliated with major academic centers. IM residency program websites provided basic information for programs with tracks. We excluded tracks focused entirely on QI6 because, though a crucial part of HM, QI training alone is probably insufficient for preparing residents for success as hospitalists on residency completion. Similarly, IM residencies with stand-alone HM clinical rotations without longitudinal HM curricula were excluded.

Semistructured interviews with track directors were conducted by e-mail or telephone for all tracks except one, the details of which are published.7 We tabulated data and reviewed qualitative information to identify themes among the different tracks. As this study did not involve human participants, Institutional Review Board approval was not needed.

RESULTS

We identified 11 HM residency training programs at major academic centers across the United States: Cleveland Clinic, Stanford University, Tulane University, University of California Davis, University of California Irvine, University of Colorado, University of Kentucky, University of Minnesota, University of New Mexico, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Wake Forest University (Table 1). We reviewed the websites of about 10 other programs, but none suggested existence of a track. Additional programs contacted reported no current track.

Track Participants and Structure

HM tracks mainly target third-year residents (Table 1). Some extend into the second year of residency, and 4 have opportunities for intern involvement, including a separate match number at Colorado. Tracks accept up to 12 residents per class. Two programs, at Colorado and Virginia, are part of IM programs in which all residents belong to a track (eg, HM, primary care, research).

HM track structures vary widely and are heavily influenced by the content delivery platforms of their IM residency programs. Several HM track directors emphasized the importance of fitting into existing educational frameworks to ensure access to residents and to minimize the burden of participation. Four programs deliver the bulk of their nonclinical content in dedicated blocks; 6 others use brief recurring sessions to deliver smaller aliquots longitudinally (Table 1). The number of protected hours for content delivery ranges from 10 to more than 40 annually. All tracks use multiple content delivery modes, including didactic sessions and journal clubs. Four tracks employ panel discussions to explore career options within HM. Several also use online platforms, including discussions, readings, and modules.

Quality Improvement

The vast majority of curricula prominently feature experiential QI project involvement (Table 2). These mentored longitudinal projects allow applied delivery of content, such as QI methods and management skills. Four tracks use material from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.8 Several also offer dedicated QI rotations that immerse residents in ongoing QI efforts.

Institutional partnerships support these initiatives at several sites. The Minnesota track is a joint venture of the university and Regions Hospital, a nonprofit community hospital. The Virginia track positions HM residents to lead university-wide interdisciplinary QI teams. For project support, the Colorado and Kentucky tracks partner with local QI resources—the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Efficiency at Colorado and the Office of Value and Innovation in Healthcare Delivery at Kentucky.

Health Care Economics and Value

Many programs leverage the rapidly growing emphasis on health care “value” as an opportunity for synergy between IM programs and HM tracks. Examples include involving residents in efforts to improve documentation or didactic instruction on topics such as health care finance. The New Mexico and Wake Forest tracks offer elective rotations on health care economics. Several track directors mentioned successfully expanding curricula on health care value from the HM track into IM residency programs at large, providing a measurable service to the residency programs while ensuring content delivery and freeing up additional time for track activities.

Scholarship and Career Development

Most programs provide targeted career development for residents. Six tracks provide sessions on job procurement skills, such as curriculum vitae preparation and interviewing (Table 2). Many also provide content on venues for disseminating scholarly activity. The Colorado, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Tulane programs feature content on abstract and poster creation. Leadership development is addressed in several tracks through dedicated track activities or participation in discrete, outside-track events. Specifically, Colorado offers a leadership track for residents interested in hospital administration, Cleveland has a leadership journal club, Wake Forest enrolls HM residents in leadership training available through the university, and Minnesota sends residents to the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy (Table 2).

Clinical Rotations

Almost all tracks include a clinical rotation, typically pairing residents directly with hospitalist attendings to encourage autonomy and mentorship. Several also offer elective rotations in various disciplines within HM (Table 2). The Kentucky and Virginia tracks incorporate working with advanced practice providers into their practicums. The Cleveland, Minnesota, Tulane, and Virginia tracks offer HM rotations in community hospitals or postacute settings.

HM rotations also pair clinical experiences with didactic education on relevant topics (eg, billing and coding). The Cleveland, Minnesota, and Virginia tracks developed clinical rotations reflecting the common 7-on and 7-off schedule with nonclinical obligations, such as seminars linking specific content to clinical experiences, during nonclinical time.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation into the current state of HM training found that HM track curricula focus largely on QI, health care economics, and professional development. This focus likely developed in response to hospitalists’ increasing engagement in related endeavors. HM tracks have dynamic and variable structures, reflecting an evolving field and the need to fit into existing IM residency program structures. Similarly, the content covered in HM tracks is tightly linked to perceived opportunities within IM residency curricula. The heterogeneity of content suggests the breadth and ambiguity of necessary competencies for aspiring hospitalists. One of the 11 tracks has not had any residents enroll within the past few years—a testament to the continued effort necessary to sustain such tracks, including curricular updates and recruiting. Conversely, many programs now share track content with the larger IM residency program, suggesting HM tracks may be near the forefront of medical education in some areas.

Our study had several limitations. As we are unaware of any databases of HM tracks, we discussed tracks with professional contacts, performed Internet searches, and reviewed IM residency program websites. Our search, however, was not exhaustive; despite our best efforts, we may have missed or mischaracterized some track offerings. Nevertheless, we think that our analysis represents the first thorough compilation of HM tracks and that it will be useful to institutions seeking to create or enhance HM-specific training.

As the field continues to evolve, we are optimistic about the future of HM training. We suspect that HM residency training tracks will continue to expand. More work is needed so these tracks can adjust to the changing HM and IM residency program landscapes and supply well-trained physicians for the HM workforce.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank track directors Alpesh Amin, David Gugliotti, Rick Hilger, Karnjit Johl, Nasir Majeed, Georgia McIntosh, Charles Pizanis, and Jeff Wiese for making this study possible.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

The field of hospital medicine (HM) is rapidly expanding in the areas of clinical medicine, administration, and quality improvement (QI).1 Emerging with this growth is a gap in the traditional internal medicine (IM) training and skills needed to be effective in HM.1,2 These skills include clinical and nonclinical aptitudes, such as process improvement, health care economics, and leadership.1-3 However, resident education on these topics must compete with other required curricular content in IM residency training.2,4 Few IM residencies offer focused HM training that emphasizes key components of successful HM careers.3,5

Within the past decade, designated HM tracks within IM residency programs have been proposed as a potential solution. Initially, calls for such tracks focused on gaps in the clinical competencies required of hospitalists.1 Tracks have since evolved to also include skills required to drive high-value care, process improvement, and scholarship. Designated HM tracks address these areas through greater breadth of curricula, additional time for reflection, participation in group projects, and active application to clinical care.4 We conducted a study to identify themes that could inform the ongoing evolution of dedicated HM tracks.

METHODS

Programs were initially identified through communication among professional networks. The phrases hospital medicine residency track and internal medicine residency hospitalist track were used in broader Google searches, as there is no database of such tracks. Searches were performed quarterly during the 2015–2016 academic year. The top 20 hits were manually filtered to identify tracks affiliated with major academic centers. IM residency program websites provided basic information for programs with tracks. We excluded tracks focused entirely on QI6 because, though a crucial part of HM, QI training alone is probably insufficient for preparing residents for success as hospitalists on residency completion. Similarly, IM residencies with stand-alone HM clinical rotations without longitudinal HM curricula were excluded.

Semistructured interviews with track directors were conducted by e-mail or telephone for all tracks except one, the details of which are published.7 We tabulated data and reviewed qualitative information to identify themes among the different tracks. As this study did not involve human participants, Institutional Review Board approval was not needed.

RESULTS

We identified 11 HM residency training programs at major academic centers across the United States: Cleveland Clinic, Stanford University, Tulane University, University of California Davis, University of California Irvine, University of Colorado, University of Kentucky, University of Minnesota, University of New Mexico, Virginia Commonwealth University, and Wake Forest University (Table 1). We reviewed the websites of about 10 other programs, but none suggested existence of a track. Additional programs contacted reported no current track.

Track Participants and Structure

HM tracks mainly target third-year residents (Table 1). Some extend into the second year of residency, and 4 have opportunities for intern involvement, including a separate match number at Colorado. Tracks accept up to 12 residents per class. Two programs, at Colorado and Virginia, are part of IM programs in which all residents belong to a track (eg, HM, primary care, research).

HM track structures vary widely and are heavily influenced by the content delivery platforms of their IM residency programs. Several HM track directors emphasized the importance of fitting into existing educational frameworks to ensure access to residents and to minimize the burden of participation. Four programs deliver the bulk of their nonclinical content in dedicated blocks; 6 others use brief recurring sessions to deliver smaller aliquots longitudinally (Table 1). The number of protected hours for content delivery ranges from 10 to more than 40 annually. All tracks use multiple content delivery modes, including didactic sessions and journal clubs. Four tracks employ panel discussions to explore career options within HM. Several also use online platforms, including discussions, readings, and modules.

Quality Improvement

The vast majority of curricula prominently feature experiential QI project involvement (Table 2). These mentored longitudinal projects allow applied delivery of content, such as QI methods and management skills. Four tracks use material from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.8 Several also offer dedicated QI rotations that immerse residents in ongoing QI efforts.

Institutional partnerships support these initiatives at several sites. The Minnesota track is a joint venture of the university and Regions Hospital, a nonprofit community hospital. The Virginia track positions HM residents to lead university-wide interdisciplinary QI teams. For project support, the Colorado and Kentucky tracks partner with local QI resources—the Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Efficiency at Colorado and the Office of Value and Innovation in Healthcare Delivery at Kentucky.

Health Care Economics and Value

Many programs leverage the rapidly growing emphasis on health care “value” as an opportunity for synergy between IM programs and HM tracks. Examples include involving residents in efforts to improve documentation or didactic instruction on topics such as health care finance. The New Mexico and Wake Forest tracks offer elective rotations on health care economics. Several track directors mentioned successfully expanding curricula on health care value from the HM track into IM residency programs at large, providing a measurable service to the residency programs while ensuring content delivery and freeing up additional time for track activities.

Scholarship and Career Development

Most programs provide targeted career development for residents. Six tracks provide sessions on job procurement skills, such as curriculum vitae preparation and interviewing (Table 2). Many also provide content on venues for disseminating scholarly activity. The Colorado, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Tulane programs feature content on abstract and poster creation. Leadership development is addressed in several tracks through dedicated track activities or participation in discrete, outside-track events. Specifically, Colorado offers a leadership track for residents interested in hospital administration, Cleveland has a leadership journal club, Wake Forest enrolls HM residents in leadership training available through the university, and Minnesota sends residents to the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Leadership Academy (Table 2).

Clinical Rotations

Almost all tracks include a clinical rotation, typically pairing residents directly with hospitalist attendings to encourage autonomy and mentorship. Several also offer elective rotations in various disciplines within HM (Table 2). The Kentucky and Virginia tracks incorporate working with advanced practice providers into their practicums. The Cleveland, Minnesota, Tulane, and Virginia tracks offer HM rotations in community hospitals or postacute settings.

HM rotations also pair clinical experiences with didactic education on relevant topics (eg, billing and coding). The Cleveland, Minnesota, and Virginia tracks developed clinical rotations reflecting the common 7-on and 7-off schedule with nonclinical obligations, such as seminars linking specific content to clinical experiences, during nonclinical time.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation into the current state of HM training found that HM track curricula focus largely on QI, health care economics, and professional development. This focus likely developed in response to hospitalists’ increasing engagement in related endeavors. HM tracks have dynamic and variable structures, reflecting an evolving field and the need to fit into existing IM residency program structures. Similarly, the content covered in HM tracks is tightly linked to perceived opportunities within IM residency curricula. The heterogeneity of content suggests the breadth and ambiguity of necessary competencies for aspiring hospitalists. One of the 11 tracks has not had any residents enroll within the past few years—a testament to the continued effort necessary to sustain such tracks, including curricular updates and recruiting. Conversely, many programs now share track content with the larger IM residency program, suggesting HM tracks may be near the forefront of medical education in some areas.

Our study had several limitations. As we are unaware of any databases of HM tracks, we discussed tracks with professional contacts, performed Internet searches, and reviewed IM residency program websites. Our search, however, was not exhaustive; despite our best efforts, we may have missed or mischaracterized some track offerings. Nevertheless, we think that our analysis represents the first thorough compilation of HM tracks and that it will be useful to institutions seeking to create or enhance HM-specific training.

As the field continues to evolve, we are optimistic about the future of HM training. We suspect that HM residency training tracks will continue to expand. More work is needed so these tracks can adjust to the changing HM and IM residency program landscapes and supply well-trained physicians for the HM workforce.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank track directors Alpesh Amin, David Gugliotti, Rick Hilger, Karnjit Johl, Nasir Majeed, Georgia McIntosh, Charles Pizanis, and Jeff Wiese for making this study possible.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1931]. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1110-1115. PubMed

2. Arora V, Guardiano S, Donaldson D, Storch I, Hemstreet P. Closing the gap between internal medicine training and practice: recommendations from recent graduates. Am J Med. 2005;118(6):680-685. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):436-441. PubMed

4. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

5. Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728. PubMed

6. Patel N, Brennan PJ, Metlay J, Bellini L, Shannon RP, Myers JS. Building the pipeline: the creation of a residency training pathway for future physician leaders in health care quality. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):185-190. PubMed

7. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, et al. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):646-649. PubMed

8. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. http://www.ihi.org. Accessed December 15, 2015.

1. Glasheen JJ, Siegal EM, Epstein K, Kutner J, Prochazka AV. Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists’ needs [published correction appears in J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1931]. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1110-1115. PubMed

2. Arora V, Guardiano S, Donaldson D, Storch I, Hemstreet P. Closing the gap between internal medicine training and practice: recommendations from recent graduates. Am J Med. 2005;118(6):680-685. PubMed

3. Glasheen JJ, Goldenberg J, Nelson JR. Achieving hospital medicine’s promise through internal medicine residency redesign. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):436-441. PubMed

4. Wiese J. Residency training: beginning with the end in mind. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1122-1123. PubMed

5. Glasheen JJ, Epstein KR, Siegal E, Kutner JS, Prochazka AV. The spectrum of community-based hospitalist practice: a call to tailor internal medicine residency training. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):727-728. PubMed

6. Patel N, Brennan PJ, Metlay J, Bellini L, Shannon RP, Myers JS. Building the pipeline: the creation of a residency training pathway for future physician leaders in health care quality. Acad Med. 2015;90(2):185-190. PubMed

7. Kumar A, Smeraglio A, Witteles R, et al. A resident-created hospitalist curriculum for internal medicine housestaff. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):646-649. PubMed

8. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. http://www.ihi.org. Accessed December 15, 2015.

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Society of Hospital Medicine's 2015 Annual Meeting Adds Focus on Early Career Hospitalists

I recall my first time at a national physicians conference. Moving from room to room amongst a sea of medical professionals from across the nation, I felt a bit lost. Which sessions should I attend? How could I maximize learning in my limited time there? Should I enter the cavernous hall for the plenary session?

There were so many offerings, and who knew what might be relevant for me at that early stage of training? (I remember thinking, what the heck is an “RVU”?)

Fear not, future and early career hospitalists: SHM has created a dedicated track and special sessions at HM15 with your issues and concerns in mind.

For the first time, SHM’s annual meeting is offering an educational track specifically tailored to medical students, residents, and early career hospitalists. The “Young Hospitalist” track will be delivered by speakers from the Physicians in Training Committee and will be enhanced by a special luncheon for students and residents, followed by the afternoon Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes abstract presentations.

This month’s “Future Hospitalist” column provides a sneak peek at all of the content in this track. All sessions will be on Monday, March 30, at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. (www.hospitalmedicine2015.org).

“Career Pathways in Hospital Medicine: Getting Your Ideal Job–One Job at a Time”

10:35 a.m. to 11:15 a.m.

This session will explore the many avenues a hospitalist’s career may take, including clinical medicine, administration, hospital leadership, and academic hospital medicine. It will highlight the value of being open to different opportunities and explain how such opportunities can ignite and shape one’s career over the long term.

Through the stories and career trajectories of real hospitalists, the faculty will demonstrate how teaching students and residents, getting involved in patient-related projects, and joining local or national committees can open the door to further opportunities.

Discussion will highlight the ways in which incorporating any one or more of these hospital medicine “extras” into your ongoing responsibilities might be the crucial ingredient to help you find, achieve, and/or create your ideal job.

“How to Stand Out: Being the Best Applicant You Can Be”

11:20 a.m. to noon

This session will focus on the practical skills and information needed to embark on a fulfilling career in hospital medicine. Topics covered in this session will include effective ways to search for a job and maximize the impression you make on potential employers. We will help you identify which mentors can guide you through this process. You will learn how to leverage what you’ve done in training, or just out of training, to make yourself an attractive applicant. We will cover the do’s and don’ts of correspondence with prospective employers and essential questions to ask during interviews.

“Getting to the Top of the Pile: How to Write the Best CV”

1:10 p.m. to 1:50 p.m.

A good CV can be a gateway to a great career in hospital medicine, but a poorly formatted CV can underrepresent a strong future hospitalist, limiting opportunities. This session will provide detailed information about what hospitalist leaders look for in a CV, and dissect good and bad CVs. You will hear strategies for ensuring that your CV will be both attention grabbing and effective.

“Quality and Patient Safety for Residents and Students”

1:55 p.m. to 2:25 p.m.

Students and residents are required to have at least some quality and patient safety exposure during their training; however, it is often not until they embark upon their own careers that they realize the critical role quality and safety play in both hospital operations and patient care. In this session, we will use interactive methods and case studies to help students, residents, and early career hospitalists learn how to make the most of opportunities in quality and safety. Through these methods, we will illustrate how hospitalists can effect change within these realms even when they are just starting their careers.

“Time Management”

2:45 p.m. to 3:25 p.m.

Time management can be a challenge for any hospitalist, but it’s especially challenging early in one’s career. This session is taught by experienced hospitalists who have learned how to succeed and thrive in various venues. Presenters will examine a typical hospitalist workday and review clinical practices that help enhance efficiency and organization on the wards.

In addition, presenters will walk through different patient care scenarios and discuss strategies for maximizing the face time spent with patients and our workflow outside the patient’s room. Faculty will use examples but will leave time at the end of the session for Q&A and for sharing of techniques.

“Making the Most of Mentorship”

3:30 p.m. to 4:10 p.m.

A great mentor/mentee relationship can be a springboard to a promising career in hospital medicine. This session will help attendees to understand the importance and impact of mentorship. We will demonstrate how to identify and approach mentors—including project mentors—and to create meaningful relationships that can be both personally and professionally rewarding. Areas of focus will include choosing and planning academic, operational, or clinical projects, as well as evaluating career choices.

In addition to the above session offerings, a cornerstone of our student/resident track will be the special luncheon for medical students and residents. We will have assembled some of the best and the brightest within the field to sit with you and provide career mentoring and advice. Students and residents will have the chance to chat informally with nationally recognized leaders in diverse realms such as HM administration, academia, quality, information technology, and more.

Act now if you are interested in attending; space will be limited, and we ask that you register in advance at www.hospitalmedicine2015.org/program.

We also encourage you to attend the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract competition. Many of the concepts presented in the “Young Hospitalists” track will be illustrated in the work displayed here, and it’s a great chance to see these themes and possibilities played out in more detail. Moreover, this year you can show support for your colleagues who have achieved the new Trainee Award, which will recognize resident and student authors within each category.

The first day of HM15 promises to be an exciting opportunity for budding hospitalists to connect with each other and learn a bit about the job application process and career development. We hope you can join us next month.

Dr. Tad-y is assistant professor of medicine, associate program director of the internal medicine residency program, and associate program director of the hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Dr. Steinberg is associate professor of medicine, associate chair for education, and residency program director in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Icahn School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Donahue is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Boston. Debra Beach is SHM’s manager of membership outreach programs.

All three authors are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee. Other members of the committee also contributed to this report.

I recall my first time at a national physicians conference. Moving from room to room amongst a sea of medical professionals from across the nation, I felt a bit lost. Which sessions should I attend? How could I maximize learning in my limited time there? Should I enter the cavernous hall for the plenary session?

There were so many offerings, and who knew what might be relevant for me at that early stage of training? (I remember thinking, what the heck is an “RVU”?)

Fear not, future and early career hospitalists: SHM has created a dedicated track and special sessions at HM15 with your issues and concerns in mind.

For the first time, SHM’s annual meeting is offering an educational track specifically tailored to medical students, residents, and early career hospitalists. The “Young Hospitalist” track will be delivered by speakers from the Physicians in Training Committee and will be enhanced by a special luncheon for students and residents, followed by the afternoon Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes abstract presentations.

This month’s “Future Hospitalist” column provides a sneak peek at all of the content in this track. All sessions will be on Monday, March 30, at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. (www.hospitalmedicine2015.org).

“Career Pathways in Hospital Medicine: Getting Your Ideal Job–One Job at a Time”

10:35 a.m. to 11:15 a.m.

This session will explore the many avenues a hospitalist’s career may take, including clinical medicine, administration, hospital leadership, and academic hospital medicine. It will highlight the value of being open to different opportunities and explain how such opportunities can ignite and shape one’s career over the long term.

Through the stories and career trajectories of real hospitalists, the faculty will demonstrate how teaching students and residents, getting involved in patient-related projects, and joining local or national committees can open the door to further opportunities.

Discussion will highlight the ways in which incorporating any one or more of these hospital medicine “extras” into your ongoing responsibilities might be the crucial ingredient to help you find, achieve, and/or create your ideal job.

“How to Stand Out: Being the Best Applicant You Can Be”

11:20 a.m. to noon

This session will focus on the practical skills and information needed to embark on a fulfilling career in hospital medicine. Topics covered in this session will include effective ways to search for a job and maximize the impression you make on potential employers. We will help you identify which mentors can guide you through this process. You will learn how to leverage what you’ve done in training, or just out of training, to make yourself an attractive applicant. We will cover the do’s and don’ts of correspondence with prospective employers and essential questions to ask during interviews.

“Getting to the Top of the Pile: How to Write the Best CV”

1:10 p.m. to 1:50 p.m.

A good CV can be a gateway to a great career in hospital medicine, but a poorly formatted CV can underrepresent a strong future hospitalist, limiting opportunities. This session will provide detailed information about what hospitalist leaders look for in a CV, and dissect good and bad CVs. You will hear strategies for ensuring that your CV will be both attention grabbing and effective.

“Quality and Patient Safety for Residents and Students”

1:55 p.m. to 2:25 p.m.

Students and residents are required to have at least some quality and patient safety exposure during their training; however, it is often not until they embark upon their own careers that they realize the critical role quality and safety play in both hospital operations and patient care. In this session, we will use interactive methods and case studies to help students, residents, and early career hospitalists learn how to make the most of opportunities in quality and safety. Through these methods, we will illustrate how hospitalists can effect change within these realms even when they are just starting their careers.

“Time Management”

2:45 p.m. to 3:25 p.m.

Time management can be a challenge for any hospitalist, but it’s especially challenging early in one’s career. This session is taught by experienced hospitalists who have learned how to succeed and thrive in various venues. Presenters will examine a typical hospitalist workday and review clinical practices that help enhance efficiency and organization on the wards.

In addition, presenters will walk through different patient care scenarios and discuss strategies for maximizing the face time spent with patients and our workflow outside the patient’s room. Faculty will use examples but will leave time at the end of the session for Q&A and for sharing of techniques.

“Making the Most of Mentorship”

3:30 p.m. to 4:10 p.m.

A great mentor/mentee relationship can be a springboard to a promising career in hospital medicine. This session will help attendees to understand the importance and impact of mentorship. We will demonstrate how to identify and approach mentors—including project mentors—and to create meaningful relationships that can be both personally and professionally rewarding. Areas of focus will include choosing and planning academic, operational, or clinical projects, as well as evaluating career choices.

In addition to the above session offerings, a cornerstone of our student/resident track will be the special luncheon for medical students and residents. We will have assembled some of the best and the brightest within the field to sit with you and provide career mentoring and advice. Students and residents will have the chance to chat informally with nationally recognized leaders in diverse realms such as HM administration, academia, quality, information technology, and more.

Act now if you are interested in attending; space will be limited, and we ask that you register in advance at www.hospitalmedicine2015.org/program.

We also encourage you to attend the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract competition. Many of the concepts presented in the “Young Hospitalists” track will be illustrated in the work displayed here, and it’s a great chance to see these themes and possibilities played out in more detail. Moreover, this year you can show support for your colleagues who have achieved the new Trainee Award, which will recognize resident and student authors within each category.

The first day of HM15 promises to be an exciting opportunity for budding hospitalists to connect with each other and learn a bit about the job application process and career development. We hope you can join us next month.

Dr. Tad-y is assistant professor of medicine, associate program director of the internal medicine residency program, and associate program director of the hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Dr. Steinberg is associate professor of medicine, associate chair for education, and residency program director in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Icahn School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Donahue is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Boston. Debra Beach is SHM’s manager of membership outreach programs.

All three authors are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee. Other members of the committee also contributed to this report.

I recall my first time at a national physicians conference. Moving from room to room amongst a sea of medical professionals from across the nation, I felt a bit lost. Which sessions should I attend? How could I maximize learning in my limited time there? Should I enter the cavernous hall for the plenary session?

There were so many offerings, and who knew what might be relevant for me at that early stage of training? (I remember thinking, what the heck is an “RVU”?)

Fear not, future and early career hospitalists: SHM has created a dedicated track and special sessions at HM15 with your issues and concerns in mind.

For the first time, SHM’s annual meeting is offering an educational track specifically tailored to medical students, residents, and early career hospitalists. The “Young Hospitalist” track will be delivered by speakers from the Physicians in Training Committee and will be enhanced by a special luncheon for students and residents, followed by the afternoon Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes abstract presentations.

This month’s “Future Hospitalist” column provides a sneak peek at all of the content in this track. All sessions will be on Monday, March 30, at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. (www.hospitalmedicine2015.org).

“Career Pathways in Hospital Medicine: Getting Your Ideal Job–One Job at a Time”

10:35 a.m. to 11:15 a.m.

This session will explore the many avenues a hospitalist’s career may take, including clinical medicine, administration, hospital leadership, and academic hospital medicine. It will highlight the value of being open to different opportunities and explain how such opportunities can ignite and shape one’s career over the long term.

Through the stories and career trajectories of real hospitalists, the faculty will demonstrate how teaching students and residents, getting involved in patient-related projects, and joining local or national committees can open the door to further opportunities.

Discussion will highlight the ways in which incorporating any one or more of these hospital medicine “extras” into your ongoing responsibilities might be the crucial ingredient to help you find, achieve, and/or create your ideal job.

“How to Stand Out: Being the Best Applicant You Can Be”

11:20 a.m. to noon

This session will focus on the practical skills and information needed to embark on a fulfilling career in hospital medicine. Topics covered in this session will include effective ways to search for a job and maximize the impression you make on potential employers. We will help you identify which mentors can guide you through this process. You will learn how to leverage what you’ve done in training, or just out of training, to make yourself an attractive applicant. We will cover the do’s and don’ts of correspondence with prospective employers and essential questions to ask during interviews.

“Getting to the Top of the Pile: How to Write the Best CV”

1:10 p.m. to 1:50 p.m.

A good CV can be a gateway to a great career in hospital medicine, but a poorly formatted CV can underrepresent a strong future hospitalist, limiting opportunities. This session will provide detailed information about what hospitalist leaders look for in a CV, and dissect good and bad CVs. You will hear strategies for ensuring that your CV will be both attention grabbing and effective.

“Quality and Patient Safety for Residents and Students”

1:55 p.m. to 2:25 p.m.

Students and residents are required to have at least some quality and patient safety exposure during their training; however, it is often not until they embark upon their own careers that they realize the critical role quality and safety play in both hospital operations and patient care. In this session, we will use interactive methods and case studies to help students, residents, and early career hospitalists learn how to make the most of opportunities in quality and safety. Through these methods, we will illustrate how hospitalists can effect change within these realms even when they are just starting their careers.

“Time Management”

2:45 p.m. to 3:25 p.m.

Time management can be a challenge for any hospitalist, but it’s especially challenging early in one’s career. This session is taught by experienced hospitalists who have learned how to succeed and thrive in various venues. Presenters will examine a typical hospitalist workday and review clinical practices that help enhance efficiency and organization on the wards.

In addition, presenters will walk through different patient care scenarios and discuss strategies for maximizing the face time spent with patients and our workflow outside the patient’s room. Faculty will use examples but will leave time at the end of the session for Q&A and for sharing of techniques.

“Making the Most of Mentorship”

3:30 p.m. to 4:10 p.m.

A great mentor/mentee relationship can be a springboard to a promising career in hospital medicine. This session will help attendees to understand the importance and impact of mentorship. We will demonstrate how to identify and approach mentors—including project mentors—and to create meaningful relationships that can be both personally and professionally rewarding. Areas of focus will include choosing and planning academic, operational, or clinical projects, as well as evaluating career choices.

In addition to the above session offerings, a cornerstone of our student/resident track will be the special luncheon for medical students and residents. We will have assembled some of the best and the brightest within the field to sit with you and provide career mentoring and advice. Students and residents will have the chance to chat informally with nationally recognized leaders in diverse realms such as HM administration, academia, quality, information technology, and more.

Act now if you are interested in attending; space will be limited, and we ask that you register in advance at www.hospitalmedicine2015.org/program.

We also encourage you to attend the Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract competition. Many of the concepts presented in the “Young Hospitalists” track will be illustrated in the work displayed here, and it’s a great chance to see these themes and possibilities played out in more detail. Moreover, this year you can show support for your colleagues who have achieved the new Trainee Award, which will recognize resident and student authors within each category.

The first day of HM15 promises to be an exciting opportunity for budding hospitalists to connect with each other and learn a bit about the job application process and career development. We hope you can join us next month.

Dr. Tad-y is assistant professor of medicine, associate program director of the internal medicine residency program, and associate program director of the hospitalist training program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Dr. Steinberg is associate professor of medicine, associate chair for education, and residency program director in the Department of Medicine at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Icahn School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Donahue is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Boston. Debra Beach is SHM’s manager of membership outreach programs.

All three authors are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee. Other members of the committee also contributed to this report.

What Is the Best Approach for the Evaluation and Management of Endocrine Incidentalomas?

Case

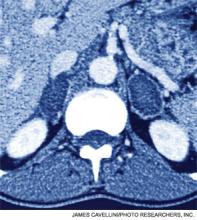

A 54-year-old man with a history of hypertension treated with hydrocholorothiazide and Type 2 diabetes mellitus is admitted with abdominal pain and found to have an incidental 2.1-cm left adrenal mass on CT scan of the abdomen. He denies symptoms of headache, palpitations, weight gain, or muscle weakness. His exam is significant for mildly elevated blood pressure. What is the best approach for evaluation and management of this incidental finding?

Overview

Incidentalomas are mass lesions that are inadvertently discovered during radiolographic diagnostic testing or treatment for other clinical conditions that are unrelated to the incidental mass. In recent decades, improvements in radiographic diagnostic techniques and sensitivity have led to increasing discovery of incidental lesions that are often in the absence of clinical signs or symptoms.1 Three commonly discovered lesions by hospitalists are pituitary, thyroid, and adrenal incidentalomas.2 The concerns associated with these findings relate to the potential for dysfunctional hormone secretion or malignancy.

Patients found with pituitary incidentalomas can be susceptible to several types of adverse outcomes: hormonal hypersecretion, hypopituitarism, neurologic morbidity due to tumor size, and malignancy in rare cases. Thyroid incidentalomas are impalpable nodules discovered in the setting of ultrasound or cross-sectional neck scans, such as positron emission tomography (PET) scans. Discovery of a thyroid incidentaloma raises concern for thyroid malignancy.3 The increased use of abdominal ultrasound, CT scans, and MRI has fueled the growing incidence of adrenal incidentalomas (AIs).

The discovery of an endocrine incidentaloma in the inpatient setting warrants a systematic approach that includes both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic management. A hospitalist should consider an approach that includes (see Table 1):

- Characterization of the incidentaloma, including clinical signs and symptoms, size, hormonal function, and malignant potential;

- Immediate management, including medical versus surgical treatment; and

- Post-discharge management, including monitoring.

Review of the Data

Pituitary incidentalomas. The prevalence of pituitary incidentalomas found by CT ranges from 3.7% to 20%, while the prevalence found by MRI approximates 10%. Autopsy studies have revealed a prevalence ranging from 1.5% to 26.7% for adenomas less than 10 mm, considered to be microadenomas. Broad categories of etiologies should be considered: pituitary adenoma, nonpituitary tumors, vascular lesions, infiltrative disorders, and others (see Table 2). The majority of pituitary adenomas secrete prolactin (30% to 40%) or are nonsecreting (30% to 40%). Adenomas secreting adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH, 2% to 10%), growth hormone (GH, 2% to 10%), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH, <1%), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH) are much less common.2 Significant morbidity and premature mortality are associated with hyperprolactinemia, acromegaly (growth hormone excess), Cushing’s syndrome, and hyperthyroidism. Additionally, up to 41% of patients with macroadenomas were found to have varying degrees of hypopituitarism due to compression of the hypothalamus, the hypothalamic-pituitary stalk, or the pituitary itself.4

Recently, the Endocrine Society released consensus recommendations to guide the evaluation and treatment of pituitary incidentalomas, which are included in the approach outlined below.5 A detailed history and physical examination should be obtained with specific inquiry as to signs and symptoms of hormonal excess and mass effect from the tumor. Examples of symptoms of hormone excess can include:

- Prolactin: menstrual irregularity, anovulation, infertility, decreased libido, impotence, osteoporosis;

- Growth hormone: high frequency of colonic polyps and colon cancer (chronic excess);

- TSH: thyrotoxicosis, atrial fibrillation; and

- ACTH: hypertension, osteoporosis, accelerated vascular disease.

Symptoms related to the mass effect of the tumor include visual field defects and hypopituitarism related to the deficient hormone, including:

- FSH/LH: oligomenorrhea, decreased libido, infertility;

- TSH: hypothyroidism (weight gain, constipation, cold intolerance);