User login

Shift to mental health model of care prescribed

Imagine a world where psychiatrists focus on mental health as much as they focus on mental illness. That is the challenge made by Dr. Dilip V. Jeste, former president of the American Psychiatric Association, current distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, La Jolla, and the leading proponent of positive psychiatry. With psychologist Barton W. Palmer, Ph.D., professor in the department of psychiatry at the university, Dr. Jeste writes and edits Positive Psychiatry (Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015) for practitioners to understand what positive psychiatry is and how it can be used to promote mental health in our patients. The pair assembled a group of experts on this topic to write chapters on all aspects of positive psychiatry.

As a psychiatrist, I appreciated their explanation of positive psychology, the precursor and motivation for putting forth a model for positive psychiatry. Positive psychiatry focuses on helping our patients with illness maximize their well-being, as opposed to positive psychology, which targets healthy individuals. Positive psychiatry fits very well into today’s holistic treatment of the patient, and urges that we focus on areas such as resilience, coping, optimism, wisdom, personal mastery, and spirituality. These areas are sources of strength for our patients that we frequently overlook.

As a geriatric psychiatrist, I also appreciated the chapter on how to apply positive psychiatry principles to geriatric patients to improve their quality of life. It cannot be understated how important social support, spirituality, resilience, optimism, and leisure activities are when treating the individual geriatric patient. There are similar chapters describing the application of positive psychiatry to other populations, such as children and minorities, and how to apply the approach to everyday clinical practice.

The book is organized into four parts. The first explains positive psychosocial factors including positive psychosocial traits, resilience, and positive social psychiatry. The second part describes positive outcomes, including the concepts of recovery and well-being, and includes a chapter about instruments for assessing positive mental health. The third part is very practical, covering psychotherapeutic, behavioral, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, and preventive interventions. The fourth part covers diverse topics such as the biology and bioethics of positive psychiatry, and deals with child and adolescent, geriatric, and cultural positive psychiatry.

It is difficult to mention all the concepts of positive psychiatry in a short review. Suffice it to say, Dr. Jeste, Dr. Palmer, and their authors have done an excellent job of explaining positive psychiatry and its relevance to improving the lives of our psychiatric patients. It is a book well worth adding to one’s library.

Dr. Lapid is an associate professor of psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., and has American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology certifications in psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, psychosomatic medicine, and hospice and palliative medicine.

Imagine a world where psychiatrists focus on mental health as much as they focus on mental illness. That is the challenge made by Dr. Dilip V. Jeste, former president of the American Psychiatric Association, current distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, La Jolla, and the leading proponent of positive psychiatry. With psychologist Barton W. Palmer, Ph.D., professor in the department of psychiatry at the university, Dr. Jeste writes and edits Positive Psychiatry (Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015) for practitioners to understand what positive psychiatry is and how it can be used to promote mental health in our patients. The pair assembled a group of experts on this topic to write chapters on all aspects of positive psychiatry.

As a psychiatrist, I appreciated their explanation of positive psychology, the precursor and motivation for putting forth a model for positive psychiatry. Positive psychiatry focuses on helping our patients with illness maximize their well-being, as opposed to positive psychology, which targets healthy individuals. Positive psychiatry fits very well into today’s holistic treatment of the patient, and urges that we focus on areas such as resilience, coping, optimism, wisdom, personal mastery, and spirituality. These areas are sources of strength for our patients that we frequently overlook.

As a geriatric psychiatrist, I also appreciated the chapter on how to apply positive psychiatry principles to geriatric patients to improve their quality of life. It cannot be understated how important social support, spirituality, resilience, optimism, and leisure activities are when treating the individual geriatric patient. There are similar chapters describing the application of positive psychiatry to other populations, such as children and minorities, and how to apply the approach to everyday clinical practice.

The book is organized into four parts. The first explains positive psychosocial factors including positive psychosocial traits, resilience, and positive social psychiatry. The second part describes positive outcomes, including the concepts of recovery and well-being, and includes a chapter about instruments for assessing positive mental health. The third part is very practical, covering psychotherapeutic, behavioral, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, and preventive interventions. The fourth part covers diverse topics such as the biology and bioethics of positive psychiatry, and deals with child and adolescent, geriatric, and cultural positive psychiatry.

It is difficult to mention all the concepts of positive psychiatry in a short review. Suffice it to say, Dr. Jeste, Dr. Palmer, and their authors have done an excellent job of explaining positive psychiatry and its relevance to improving the lives of our psychiatric patients. It is a book well worth adding to one’s library.

Dr. Lapid is an associate professor of psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., and has American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology certifications in psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, psychosomatic medicine, and hospice and palliative medicine.

Imagine a world where psychiatrists focus on mental health as much as they focus on mental illness. That is the challenge made by Dr. Dilip V. Jeste, former president of the American Psychiatric Association, current distinguished professor of psychiatry and neurosciences at the University of California, La Jolla, and the leading proponent of positive psychiatry. With psychologist Barton W. Palmer, Ph.D., professor in the department of psychiatry at the university, Dr. Jeste writes and edits Positive Psychiatry (Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2015) for practitioners to understand what positive psychiatry is and how it can be used to promote mental health in our patients. The pair assembled a group of experts on this topic to write chapters on all aspects of positive psychiatry.

As a psychiatrist, I appreciated their explanation of positive psychology, the precursor and motivation for putting forth a model for positive psychiatry. Positive psychiatry focuses on helping our patients with illness maximize their well-being, as opposed to positive psychology, which targets healthy individuals. Positive psychiatry fits very well into today’s holistic treatment of the patient, and urges that we focus on areas such as resilience, coping, optimism, wisdom, personal mastery, and spirituality. These areas are sources of strength for our patients that we frequently overlook.

As a geriatric psychiatrist, I also appreciated the chapter on how to apply positive psychiatry principles to geriatric patients to improve their quality of life. It cannot be understated how important social support, spirituality, resilience, optimism, and leisure activities are when treating the individual geriatric patient. There are similar chapters describing the application of positive psychiatry to other populations, such as children and minorities, and how to apply the approach to everyday clinical practice.

The book is organized into four parts. The first explains positive psychosocial factors including positive psychosocial traits, resilience, and positive social psychiatry. The second part describes positive outcomes, including the concepts of recovery and well-being, and includes a chapter about instruments for assessing positive mental health. The third part is very practical, covering psychotherapeutic, behavioral, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, and preventive interventions. The fourth part covers diverse topics such as the biology and bioethics of positive psychiatry, and deals with child and adolescent, geriatric, and cultural positive psychiatry.

It is difficult to mention all the concepts of positive psychiatry in a short review. Suffice it to say, Dr. Jeste, Dr. Palmer, and their authors have done an excellent job of explaining positive psychiatry and its relevance to improving the lives of our psychiatric patients. It is a book well worth adding to one’s library.

Dr. Lapid is an associate professor of psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn., and has American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology certifications in psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, psychosomatic medicine, and hospice and palliative medicine.

Munchausen Syndrome by Adult Proxy

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

Asher first described Munchausen syndrome by proxy over 60 years ago. Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always traveled widely; and their stories like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful.[1] Munchausen syndrome is a psychiatric disorder in which a patient intentionally induces or feigns symptoms of physical or psychiatric illness to assume the sick role. In 1977, Meadow described the first case in which a caregiverperpetrator deliberately produced physical symptoms in a child for proxy gratification.[2] Unlike malingering, in which external incentives drive conscious symptom falsification, Munchausen syndrome by proxy (MSBP) is associated with fulfillment of the abuser's own psychological need for garnering praise from medical staff for devoted care given a sick child.[3, 4]

MSBP was once considered vanishingly rare. Many experts now believe it is more common, with a reported annual incidence of 0.4/100,000 in children younger than 16 years, and 2/100,000 in children younger than 1 year.[5] It is a disorder in which a parent, often the mother (94%99%)[6] and often with training or interest in the medical field,[5] is the perpetrator. The medical team caring for her child often views her as unusually helpful, and she is frequently psychiatrically ill with disorders such as depression, personality disorder, or prior personal history of somatoform or factitious disorder.[7, 8] The perpetrator typically inflicts physical harm, although occasionally she may simply lie about symptoms or tamper with laboratory samples.[5] The most common methods of inflicting harm are poisoning and suffocation. Overall mortality is 6% to 9%.[6, 9]

Although a large body of literature addresses pediatric cases, there is little to guide clinicians when victims are adults. An obvious reason may be that MSBP with adult proxies (MSB‐AP) has been reported so rarely, although we believe it is under‐recognized and more common than thought. The primary objective of this review was to identify all published cases of MSB‐AP, and synthesize them to characterize victims and perpetrators, modes of deceit, and relationships between victims and perpetrators so that clinicians will be better equipped to recognize such cases or at least include MSB‐AP in the differential of possibilities when symptoms and history are inconsistent.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Rochester Institutional Review Board approved this study. The databases of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Knowledge, and PsychINFO were searched from inception through April 2014 to identify all published cases of Munchausen by proxy in patients 18 years or older. The following search terms were used: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, factitious disorder by proxy, Munchausen syndrome, and factitious disorder. Reports were included when they described single or multiple cases of MSBP with victims aged at least 18 years. The search was not limited to articles published in English. Bibliographies of selected articles were reviewed for reports identifying additional cases.

RESULTS

We found 10 reports describing 11 cases of MSB‐AP and 1 report describing 2 unique cases of MSB‐AP (Tables 1 and 2). Two case reports were published in French[10, 11] and 1 in Polish.[12] Sigal et al.[13] describes 2 different victims with a common perpetrator, and another report[14] describes the same perpetrator with a third victim. One case, though cited as MSB‐AP in the literature was excluded because it did not meet the criteria for the disorder. In this case, the wife of a 28‐year‐old alcoholic male poured acid on him while he was inebriated, ostensibly to vent frustration and coerce him into sobriety.[15, 16]

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Presenting Features | Occupation/Education | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | F | 20s | Abscesses (skin) | NP | Death |

| F | 21 | Abscesses (skin) | Child care | Paraplegia | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | NP | Rash | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | M | 69 | None | Retired businessman | Continued fabrication |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | M | 40s | Coma | Businessman | Abuse stopped |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | 73 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | 21 | NP | Developmental delay | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | 80 | Syncope | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | F | 82 | None | NP | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | M | 71 | Coma | NP | Abuse stopped |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | 23 | Rash | High school graduate | Continued abuse |

| F | 21 | Recurrent bacteremia | College student | Death | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | F | 79 | Fluid overload/false symptom history | Retired | Continued |

| Author | Gender | Age, y | Relationship | Occupation | Mode of Abuse | Outcome When Confronted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Sigal M et al. (1986)[13] | M | 26 | Husbanda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration |

| M | 29 | Boyfrienda | Businessman | Poisoningb followed by subcutaneous gasoline injection | Confession and incarceration | |

| Sigal MD et al. (1991)[14] | M | 34 | Cellmatea | Worked in medical clinic where incarcerated | Poisoningc followed by subcutaneous turpentine injection | Confession and attempted murder conviction |

| Smith NJ et al. (1989)[19] | F | 55 | Companion | Nurse | False history of hematuria, weakness, headaches | Denial |

| Krebs MO et al. (1996)[10] | F | 47 | Wife | Nurse | Tranquilizer injections | Confession and placed on probation |

| Ben‐Chetrit E et al. (1998)[20] | F | NP | Daughter | Nurse | Insulin injections | Denial |

| Feldman KW et al. (1998)[8] | F | NP | Mother | Business woman | False history of Batten's disease | NP |

| Chodorowsk Z et al. (2003)[12] | F | NP | Granddaughter | NP | Poisoningb | Denial |

| Strubel D et al. (2003)[11] | M | NP | Son | NP | False history of memory loss | NP |

| Granot R et al. (2004)[21] | F | NP | Wife | Hospital employee | Poisoningb | Confession |

| Deimel GW et al. (2012)[17] | F | NP | Mother | Unemployed chronic medical problems | Toxin application to skin | Denial |

| F | NP | Mother | Medical office receptionist | Intravenous injection unknown substance | Denial | |

| Singh A et al. (2013)[22] | M | NP | Son | NP | Fluid administration in context of fluid restriction/erratic medication administration/falsifying severity of symptoms | Denial |

Of the 13 victims, 9 (69%) were women and 4 (31%) were men. Of the ages reported, the median age was 69 years and the mean age was 51 (range, 2182 years). Exact age was not reported in 3 cases. Lying about signs and symptoms, but not actually inducing injury, occurred in 3 cases (23%), whereas in 10 cases (77%), the victims presented with physical findings, including coma (3), rash (2), skin abscesses (2), syncope (1), recurrent bacteremia (1), and fluid overload (1). Seven (54%) of the victims were poisoned, 2 via drug injection and 5 by beverage/food contamination. A perpetrator sedated 3 victims and subsequently injected them, 2 with gasoline and another with turpentine. Two of the victims were involved in business, 1 worked in childcare, 1 attended beauty school after graduating from high school, 1 attended college, and 1 was developmentally delayed. Victim education or occupation was not reported in 7 cases.

Of the 11 perpetrators, 8 (73%) were women, and 3 (27%) were men (note that the same male perpetrator had 3 victims). Median age was 34 years (range, 2655 years), although exact age was not reported in 4 cases. The perpetrator was the victim's mother in 3 cases, wife in 2 cases, son in 2 cases, and daughter, granddaughter, husband, companion, boyfriend, or prison cellmate in 1 case each. Five (38%) worked in healthcare.

All of the perpetrators were highly involved, even overly involved, in the care of their victims, frequently present, sometimes hovering, in hospital settings, and were viewed as generally helpful, if not overintrusive, by hospital staff. When confronted, 3 perpetrators confessed, 3 denied abuse that then ceased, and 4 more denied abuse that continued, culminating in death in 1 case. In 1 case, the outcome was not reported.[8] At least 3 victims remained with their perpetrators. Two perpetrators were criminally charged, 1 receiving probation and the other incarceration. The latter began abusing his cellmate, behavior that did not stop until he was confronted in prison.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to locate and review all published cases of MSB‐AP. Our secondary aim was to describe salient characteristics of perpetrators, victims, and fabricated diseases in hopes of helping clinicians better recognize this disorder.

Our review shows that perpetrators were exclusively the victims' caregivers, including mothers, wives, husbands, daughters, granddaughters, or companions. These perpetrators, many with healthcare backgrounds, were attentive, helpful, and excessively present. In the majority of cases, hidden physical abuse yielded visible disease. Less commonly, perpetrators lied about symptoms rather than actually creating signs of disease. The most common mode of disease instigation involved poisoning through beverage/food contamination or subcutaneous injection. Geriatric and developmentally delayed persons appeared particularly vulnerable to victimization. Of the 13 victims, 5 were geriatric and 1 was developmentally delayed.

The adult cases we report are similar to child cases in that the perpetrators are caregivers; however, the caregivers of the adults are a more diverse group. Other similarities between adult and child cases are that physical signs occur more often than simply falsifying information, and poisoning is the most common method of disease fabrication. Suffocation, although common in child cases, has not been reported in adults. Though present in only a minority of cases, another feature distinguishing these cases from those reported in the pediatric literature is the presence of collusion between the perpetrator and victim. When MSBP was first described, Meadow believed that victims would reach an age at which the disorder would cease because they would fight back or report the abuse.[2] In 7 of the adult cases, the victims were unknowingly poisoned; however, in 2 cases,[17] the victims knew what their mothers were doing to them and yet denied that they were harming them. To explain this collusion, Deimel et al. proposed Stockholm syndrome, a condition in which a victim holds a perpetrator in high regard, despite experiencing at their hands what others might consider brainwashing and torture.

The data from the individual cases are sometimes frustratingly incomplete, with inconsistent reporting of dyad demographics and outcomes across the 13 cases, which compromises efforts to compare and contrast them. However, because no published studies have thoroughly reviewed all existing cases of MSB‐AP, we believe our review provides important insights into this condition by consolidating available information. It is our hope that by characterizing perpetrators, victims, and common presentations, we will raise awareness about this condition among healthcare providers so that it may be included in the differential diagnosis when they encounter this dyad: a patient's medical problems do not respond as expected to therapy and a caregivers appears overly involved or attention seeking.

The diagnosis of a factitious disorder often presents an immense clinical challenge and generally involves a multidisciplinary approach.[18] In addition to the incomplete data for existing cases in the literature, we recognize the ongoing difficulties in precise diagnosis of this disorder. Because a hallmark of pathology is secrecy at the outset and often denial, and even abrupt transition of care, upon confrontation, it is often very difficult, especially early on, to uncover patterns of perpetration, let alone posit a motive. We recognize that there may be some perpetrators who are motivated by something other than purely psychological end points, such as financial reward or even sexual victimization. And when alternate care venues are sought, clinicians are often left wondering. Further, the damage that may come to a therapeutic relationship by prematurely diagnosing MSB‐AP is important to keep in mind. Hospitalists who suspect MSB‐AP should consult psychiatry. Although MSB‐AP is a diagnosis of exclusion and often based on circumstantial evidence, psychiatry can assist in diagnosing this disorder and, in the event of a confession, provide immediate therapeutic intervention. Social services can aid in a vulnerable adult investigation for patients who do not have capacity.

When Meadow first described MSBP, he ended his article by asking Is this degree of falsification rare or is it under‐recognized? Time has answered Meadow's question. Now we ask the same question with regard to MSB‐AP, is it rare or under‐recognized? We must remain vigilant for this disorder. Early recognition can prevent healthcare providers from unknowingly perpetuating victimization by treating caregiver‐induced pathology as if legitimate, thereby satisfying the perpetrator's psychological needs. Despite Meadow's assertion that proxies outgrow their victimization, our review warns that advanced age does not preclude vulnerability and in some cases, may actually increase it. In the future, the incidence and prevalence of MSB‐AP is likely to increase as medical technology allows greater survival of cognitively impaired populations who are dependent on others for care. The elderly and developmentally delayed may be especially at risk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.C.B., M.B.W., and M.I.L. report no conflicts of interest. J.M.B. receives payment for lectures, including service on speakers bureaus, from nonprofit continuing medical education organizations and universities for occasional lectures; however, this funding is not relevant to this review.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

- . Munchausen syndrome. Lancet. 1951(1):339–341.

- . Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The hinterland of child abuse. Lancet. 1977;2(8033):343–345.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000.

- , , , et al. Position paper: definitional issues in Munchausen by proxy. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(2):105–111.

- , , , . Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non‐accidental poisoning, and non‐accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75(1):57–61.

- . Web of deceit: a literature review of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. Child Abuse Negl. 1987;11(4):547–563.

- , . Psychopathology of perpetrators of fabricated or induced illness in children: case series. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(2):113–118.

- , . The central venous catheter as a source of medical chaos in Munchausen syndrome by proxy. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(4):623–627.

- , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: diagnosis and prevalence. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993;63(2):318–321.

- , , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy between two adults [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25(12):583–586.

- , , . Munchhausen syndrome by proxy in an old woman [in French]. Revue Geriatr. 2003;28:425–428.

- , , , . Consciousness disturbances: a case report of Munchausen by proxy syndrome in an elderly patient [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2003;60(4):307–308.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy: a perpetrator abusing two adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174(11):696–698.

- , , . Munchausen syndrome by adult proxy revisited. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1991;28(1):33–36.

- , , , , , . Otolaryngology fantastica: the ear, nose, and throat manifestations of Munchausen's syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(1):51–57.

- . Witchcraft's syndrome: Munchausen's syndrome by proxy. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37(3):229–230.

- , , , , , . Munchausen syndrome by proxy: an adult dyad. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):294–299.

- , . Factitious disorders and malingering: challenges for clinical assessment and management. Lancet. 2014;383(9926):1422–1432.

- , . More in sickness than in health: a case study of Munchausen by proxy in the elderly. J Fam Ther. 1989;11(4):321–334.

- , . Recurrent hypoglycaemia in multiple myeloma: a case of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in an elderly patient. J Intern Med. 1998;244(2):175–178.

- , , , , . Idiopathic recurrent stupor: a warning. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):368–369.

- , , . Munchausen by proxy in older adults: A case report. Maced J Med Sci. 2013;6(2):178–181.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine

Alcohol Withdrawal Admissions

Many patients are admitted and readmitted to acute care hospitals with alcohol‐related diagnoses, including alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS), and experience significant morbidity and mortality. In patients with septic shock or at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), chronic alcohol abuse is associated with increased ARDS and severity of multiple organ dysfunction.1 Among intensive care unit (ICU) patients, those with alcohol dependence have higher morbidity, including septic shock, and higher hospital mortality.2 Patients who experience AWS as a result of alcohol dependence may experience life‐threatening complications, such as seizures and delirium tremens.3,4 In‐hospital mortality from AWS is historically high,5 but with benzodiazepines used in a symptom‐driven manner to treat the complications of alcohol use, hospital mortality rates are more recently reported at 2.4%.6

As inpatient outcomes1,2,7 and hospital mortality810 are negatively affected by alcohol abuse, the post‐hospital course of these patients is also of interest. Specifically, patients are often admitted and readmitted with alcohol‐related diagnoses or AWS to acute care hospitals, but relatively little quantitative data exist on readmission factors in this population.11 Patients readmitted to detoxification units or alcohol and substance abuse units have been studied, and factors associated with readmission include psychiatric disorder,1217 female gender,14,15 and delay in rehabilitation aftercare.18

These results cannot be generalized to patients with AWS who are admitted and readmitted to acute‐care hospitals. First, patients hospitalized for alcohol withdrawal symptoms are often medically ill with more severe symptoms, and more frequent coexisting medical and psychiatric illnesses, that complicate the withdrawal syndrome. Detoxification units and substance abuse units require patients to be medically stable before admission, because they do not have the ability to provide a high level of supervision and treatment. Second, much of what we know regarding risk factors for readmission to detoxification centers and substance abuse units comes from studies of administrative data of the Veterans Health Administration,12,13 Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file,16 privately owned outpatient substance abuse centers,14 and publicly funded detoxification centers.18 These results may be difficult to generalize to other patient populations. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to identify demographic and clinical factors associated with multiple admissions to a general medicine service for treatment of AWS over a 3‐year period. Characterization of these high‐risk patients and their hospital course may help focus intervention and reduce these revolving door admissions.

METHODS

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt.

Patient Selection

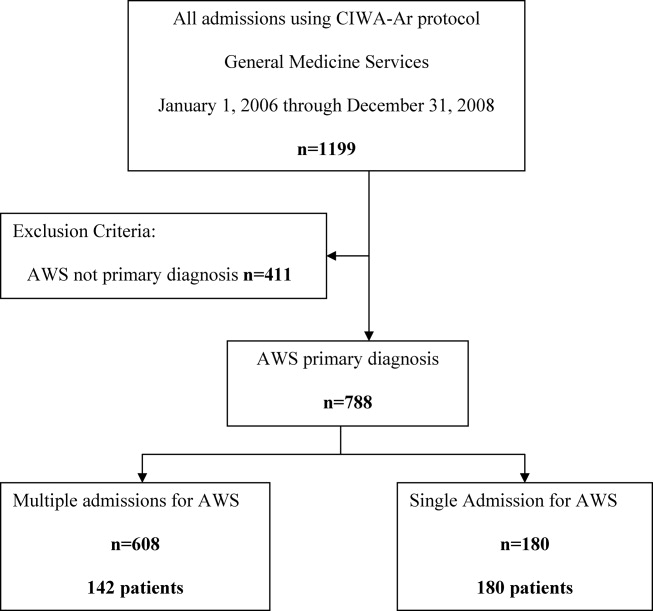

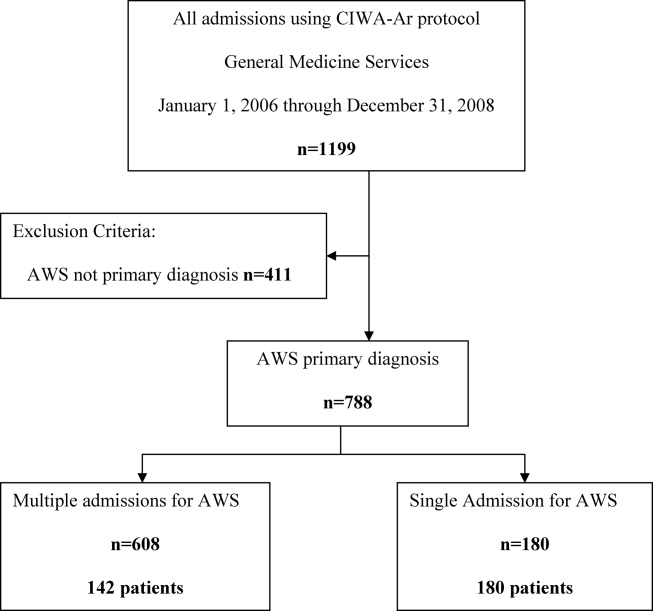

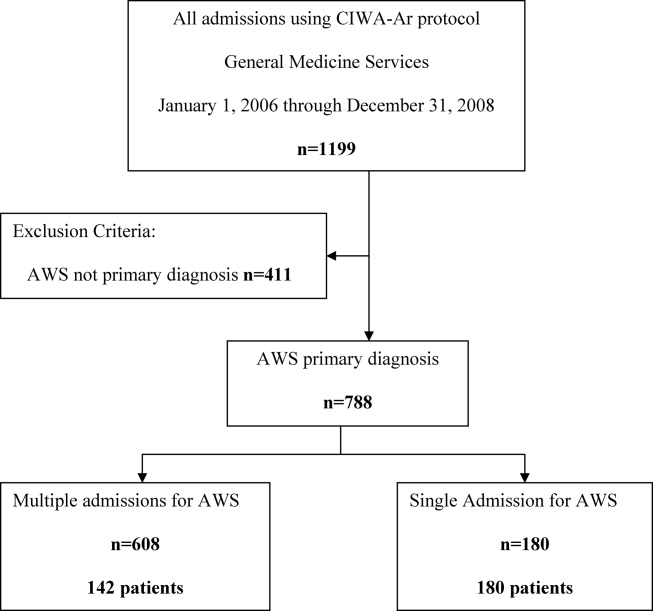

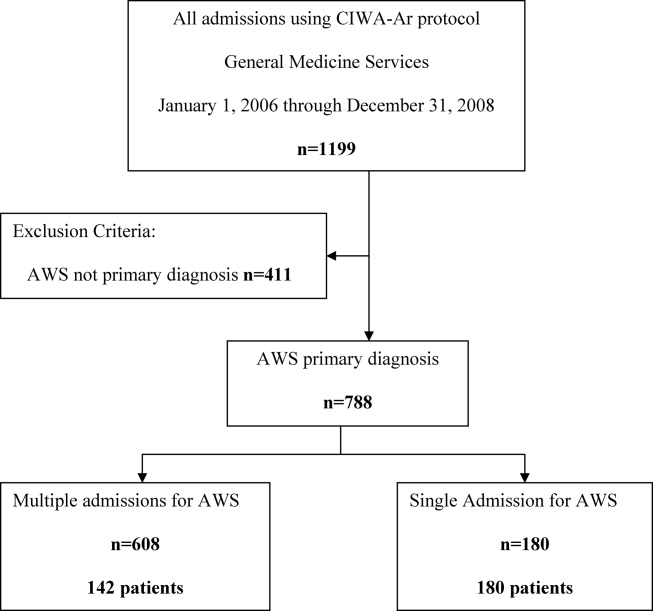

The study was conducted at an 1157‐bed academic tertiary referral hospital, located in the Midwest, that has approximately 15,000 inpatient admissions to general medicine services annually and serves as the main referral center for the region. Patients included in this study were adults admitted to general medicine services and treated with symptom‐triggered Clinical Institute Withdrawal AssessmentAlcohol Revised (CIWA‐Ar) protocol19 between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2008. Patients were identified using the Mayo Clinic Quality Improvement Resource Center database, as done in a previous CIWA‐Ar study.20 Patients were excluded if the primary diagnosis was a nonalcohol‐related diagnosis (Figure 1).

Patients were placed in 1 of 2 groups based on number of admissions during the study period, either a single‐admission group or a multiple‐admissions group. While most readmission studies use a 30‐day mark from discharge, we used 3 years to better capture relapse and recidivism in this patient population. The 2 groups were then compared retrospectively. To insure that a single admission was not arbitrarily created by the December 2008 cutoff, we reviewed the single‐admission group for additional admissions through June of 2009. If a patient did have a subsequent admission, then the patient was moved to the multiple‐admissions group.

Clinical Variables

Demographic and clinical data was obtained using the Mayo Data Retrieval System (DRS), the Mayo Clinic Life Sciences System (MCLSS) database, and electronic medical records. Clinical data for the multiple‐admissions group was derived from the first admission of the study period, and subsequently referred to as index admission. Specific demographic information collected included age, race, gender, marital status, employment status, and education. Clinical data collected included admitting diagnosis, comorbid medical disorders, psychiatric disorders, and CIWA‐Ar evaluations including highest total score (CIWA‐Ar score [max] and component scores). The CIWA‐Ar protocol is a scale to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal, based on 10 symptoms of alcohol withdrawal ranging from 0 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe). The protocol requires the scale to be administered hourly, and total scores guide the medication dosing and administration of benzodiazepines to control withdrawal symptoms. Laboratory data collected included serum ammonia, alanine aminotransferase(ALT), and admission urine drug screen. For the purposes of this study, a urine drug screen was considered positive if a substance other than alcohol was present. Length of stay (LOS) and adverse events during hospitalization (delirium tremens, intubations, rapid response team [RRT] calls, ICU transfers, and in‐hospital mortality) were also collected.

Medical comorbidity was measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).21 The CCI was scored electronically using diagnoses in the institution's medical index database dating back 5 years from patient's first, or index, admission. Originally validated as a prognostic tool for mortality 1 year after admission in medical patients, the CCI was chosen as it accounts for most medical comorbidities.21 Data was validated, by another investigator not involved in the initial abstracting process, by randomly verifying 5% of the abstracted data.

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics and demographics. Comparing the multiple‐admissions group and single‐admission group, categorical variables were evaluated using the Fisher exact test or Pearson chi‐square test. Continuous variables were evaluated using 2‐sample t test. Multivariate logistic model analyses with stepwise elimination method were used to identify risk factors that were associated with multiple admissions. Age, gender, and variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis were used in stepwise regression to get to the final model. A P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The CIWA‐Ar protocol was ordered on 1199 admissions during the study period. Of these, 411 (34.3%) admissions were excluded because AWS was not the primary diagnosis, leaving 788 (65.7%) admissions for 322 patients, which formed the study population. Of the 322 patients, 180 (56%) had a single admission and 142 (44%) had multiple admissions.

Univariate analyses of demographic and clinical variables are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Patients with multiple admissions were more likely divorced (P = 0.028), have a high school education or less (P = 0.002), have a higher CCI score (P < 0.0001), a higher CIWA‐Ar score (max) (P < 0.0001), a higher ALT level (P = 0.050), more psychiatric comorbidity (P < 0.026), and a positive urine drug screen (P < 0.001). Adverse events were not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 2).

| Variable | Single Admission N = 180 | Multiple Admissions N = 142 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, years (SD) | 47.85 (12.84) | 45.94 (12) | 0.170 |

| Male, No. (%) | 122 (68) | 109 (77) | 0.080 |

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | 0.270 | ||

| White | 168 (93) | 132 (93) | |

| African American | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 3 (2) | 6 (4) | |

| Relationship status, No. (%) | 0.160 | ||

| Divorced | 49 (27) | 55 (39) | 0.028* |

| Married | 54 (30) | 34 (24) | 0.230 |

| Separated | 9 (5) | 4 (3) | 0.323 |

| Single | 59 (33) | 38 (27) | 0.243 |

| Widowed | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 0.703 |

| Committed | 4 (2) | 7 (5) | 0.188 |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.259 |

| Education, No. (%) | 0.002* | ||

| High school graduate, GED, or less | 49 (28) | 67 (47) | |

| Some college or above | 89 (49) | 60 (42) | |

| Unknown | 41 (23) | 15 (11) | |

| Employment, No. (%) | 0.290 | ||

| Retired | 26 (14) | 12 (8) | |

| Employed | 72 (40) | 51 (36) | |

| Unemployed | 51 (28) | 51 (36) | |

| Homemaker | 9 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Work disabled | 20 (11) | 23 (16) | |

| Student | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Variable | Single Admission N = 180 | Multiple Admissions N = 142 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| LOS, mean (SD) | 3.71 (7.10) | 2.72 (3.40) | 0.130 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.7 (2.23) | 2.51 (2.90) | 0.005* |

| Medical comorbidity, No. (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (3) | 16 (11) | 0.005* |

| Cardiovascular disease | 6 (3) | 15 (11) | 0.050* |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.009* |

| Hypertension | 53 (30) | 36 (25) | 0.400 |

| Cancer | 17 (7) | 10 (9) | 0.440 |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, No. (%) | 97 (54) | 94 (66) | 0.026* |

| Adjustment disorder | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | 0.005* |

| Depressive disorder | 85 (47) | 76 (54) | 0.260 |

| Bipolar disorder | 6 (3) | 10 (7) | 0.130 |

| Psychotic disorder | 4 (2) | 6 (4) | 0.030* |

| Anxiety disorder | 30 (17) | 25 (18) | 0.820 |

| Drug abuse | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 0.730 |

| Eating disorder | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0.050* |

| CIWA‐Ar scores | |||

| CIWA‐Ar score (max), mean (SD) | 15 (8) | 20 (9) | <0.000* |

| Component, mean (SD) | |||

| Agitation | 20 (11) | 36 (25) | 0.001* |

| Anxiety | 23 (13) | 38 (27) | 0.001* |

| Auditory disturbance | 4 (2) | 9 (6) | 0.110 |

| Headache | 11 (6) | 26 (18) | 0.001* |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (3) | 17 (12) | 0.003* |

| Orientation | 52 (29) | 72 (51) | 0.001* |

| Paroxysm/sweats | 9 (5) | 17 (12) | 0.023* |

| Tactile disturbance | 25 (14) | 54 (38) | 0.001* |

| Tremor | 35 (19) | 47 (33) | 0.004* |

| Visual disturbance | 54 (30) | 77 (54) | 0.001* |

| ALT (U/L), mean (SD) | 76 (85) | 101 (71) | 0.050* |

| Ammonia (mcg N/dl), mean (SD) | 25 (14) | 29 (29) | 0.530 |

| Positive urine drug screen, No. (%) | 25 (14) | 49 (35) | <0.001* |

| Tetrahydrocannabinol | 14 (56) | 19 (39) | |

| Cocaine | 8 (32) | 8 (16) | |

| Benzodiazepine | 6 (24) | 11 (22) | |

| Opiate | 4 (16) | 13 (26) | |

| Amphetamine | 2 (8) | 2 (4) | |

| Barbiturate | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Adverse event, No. (%) | |||

| RRT | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.866 |

| ICU transfer | 32 (18) | 20 (14) | 0.550 |

| Intubation | 12 (7) | 4 (3) | 0.890 |

| Delirium tremens | 7 (4) | 4 (3) | 0.600 |

| In‐hospital mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Multivariate logistic model analysis was performed using the variables age, male gender, divorced marital status, high school education or less, CIWA‐Ar score (max), CCI score, psychiatric comorbidity, and positive urine drug screen. With a stepwise elimination process, the final model showed that multiple admissions were associated with high school education or less (P = 0.0071), higher CCI score (P = 0.0010), higher CIWA‐Ar score (max) (P < 0.0001), a positive urine drug screen (P = 0.0002), and psychiatric comorbidity (P = 0.0303) (Table 3).

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| High school education or less | 2.074 (1.219, 3.529) | 0.0071* |

| CIWA‐Ar score (max) | 1.074 (1.042, 1.107) | <0.0001* |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.232 (1.088, 1.396) | 0.0010* |

| Psychiatric comorbidity | 1.757 (1.055, 2.928) | 0.0303* |

| Positive urine drug screen | 3.180 (1.740, 5.812) | 0.0002* |

DISCUSSION

We provide important information regarding identification of individuals at high risk for multiple admissions to general medicine services for treatment of AWS. This study found that patients with multiple admissions for AWS had more medical comorbidity. They had more cases of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular disease, and their CCI scores were higher. They also had higher CIWA‐Ar (max) scores, as well as higher CIWA‐Ar component scores, indicating a more severe withdrawal.

Further, psychiatric comorbidity was also associated with multiple admissions. Consistent with the high prevalence in alcoholic patients, psychiatric comorbidity was common in both patients with a single admission and multiple admissions. We also found that a positive urine drug screen was associated with multiple admissions. Interestingly, few patients in each group had a diagnosis recorded in the medical record of an additional substance abuse disorder, yet 14% of patients with a single admission and 29% of patients with multiple admissions had a positive urine drug screen for a non‐alcohol substance. Psychiatric comorbidity, including additional substance abuse, is a well‐established risk factor for readmission to detoxification centers.1215, 17,22,23 Also, people with either an alcohol or non‐alcohol drug addiction, are known to be 7 times more likely to have another addiction than the rest of the population.24 This study suggests clinicians may underrecognize additional substance abuse disorders which are common in this patient population.

In contrast to studies of patients readmitted to detoxification units and substance abuse units,14,15,18,22 we found level of education, specifically a high school education or less, to be associated with multiple admissions. In a study of alcoholics, Greenfield and colleagues found that lower education in alcoholics predicts shorter time to relapse.25 A lack of education may result in inadequate healthcare literacy. Poor health behavior choices that follow may lead to relapse and subsequent admissions for AWS. With respect to other demographic variables, patients in our study population were predominantly men, which is not surprising. Gender differences in alcoholism are well established, with alcohol abuse and dependence more prevalent in men.26 We did not find gender associated with multiple admissions.

Our findings have management and treatment implications. First, providers who care for patients with AWS should not simply focus on treating withdrawal signs and symptoms, but also screen for and address other medical issues, which may not be apparent or seem stable at first glance. While a comorbid medical condition may not be the primary reason for hospital admission, comorbid medical conditions are known to be a source of psychological distress27 and have a negative effect on abstinence. Second, all patients should be screened for additional substance abuse. Initial laboratory testing should include a urine drug screen. Third, before discharging the patient, providers should establish primary care follow‐up for continued surveillance of medical issues. There is evidence that primary care services are predictive of better substance abuse treatment outcomes for those with medical problems.28,29

Finally, inpatient psychiatric consultation, upon admission, is essential for several reasons. First, the psychiatric team can help with initial management and treatment of the alcohol withdrawal regardless of stage and severity, obtain a more comprehensive psychiatric history, and assess for the presence of psychiatric comorbidities that may contribute to, aggravate, or complicate the clinical picture. The team can also address other substance abuse issues when detected by drug screen or clinical history. The psychiatric team, along with chemical‐dependency counselors and social workers, can provide valuable input regarding chemical‐dependency resources available on discharge and help instruct the patient in healthy behaviors. Because healthcare illiteracy may be an issue in this patient population, these instructions should be tailored to the patient's educational level. Prior to discharge, the psychiatry team, social workers, or chemical‐dependency counselors can also assist with, or arrange, rehabilitation aftercare for patients. Recent work shows that patients were less likely to be readmitted to crisis detoxification if they entered rehabilitation care within 3 days of discharge.18

Our study has significant limitations. This study was performed with data at a single academic medical center with an ethnically homogeneous patient population, limiting the external validity of its results. Because this is a retrospective study, data analyses are limited by the quality and accuracy of data in the electronic medical record. Also, our follow‐up period may not have been long enough to detect additional admissions, and we did not screen for patient admissions prior to the study period. By limiting data collection to admissions for AWS to general medical services, we may have missed cases of AWS when admitted for other reasons or to subspecialty services, and we may have missed severe cases requiring admission to an intensive care unit. While we believe we were able to capture most admissions, we may underreport this number since we cannot account for those events that may have occurred at other facilities and locations. Lastly, without a control group, this study is limited in its ability to show an association between any variable and readmission.