User login

Assessing Hospitalist Communication

Effective communication between patients and physicians improves a number of important outcomes including patient adherence to treatment,1‐3 quality of the medical history4 and clinical outcomes.1, 5, 6 Recognizing the importance of physician communication skills, the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Council for Graduate Medical Education and The Joint Commission all identify communication as a core competency for physicians.7‐9 For hospitalists and their patients, building a therapeutic partnership is challenged by the lack of a preexisting relationship and potential lack of patient history information, particularly psychosocial history.10 Other factors that complicate the relationships between hospitalists and their patients include acuity of illness, limited time course, and absence of or lack of input from patients' primary physicians.11

As a rapidly increasing percentage of hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists,12, 13 communication skills need to be directly assessed and addressed. As of 2006, at least 37% of all Medicare claims for inpatient evaluation and management services by general internists were attributed to hospitalists, and more than half of hospitalized Medicare patients are seen by hospitalists.14 Yet, a search of the MEDLINE database for articles published between 1965 and September 2009, querying hospitalist AND patient AND communication within the article title and abstract, yielded only 2 studies assessing hospitalist‐patient communication. A 1998 study15 compared patient‐reported communication problems with hospitalists versus continuity physicians involved with hospital care, and found that patients whose continuity physicians remained involved with care during the hospitalization were less likely to report communication problems than those patients who were cared for by a hospitalist alone. A 2004 study16 utilized chart documentation to compare the end‐of‐life care and communication provided by continuity physicians and hospitalists. Hospitalists were found to document end‐of‐life care discussions more often than continuity physicians, and were more likely to be present for these meetings, which may suggest improved end‐of‐life care. Neither of these hospitalist‐patient communication studies directly assessed patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists.

We undertook this study to explore patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), a psychometrically validated instrument for patient assessment of physician communication skills.17 The CAT was initially field tested in outpatient offices, omitting the inpatient experience. A 2008 study18 successfully adapted the CAT tool for use in assessing emergency department (ED) teams. Given the importance of physician‐patient communication when patients are sickest and most vulnerable in the hospital setting, we sought to establish a baseline assessment of patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists in our group. Second, we compared results of our CAT implementation with published results examining communication in other physician groups.

Methods

Between September 2008 and August 2009 we performed a cross‐sectional study of patients admitted to the hospital medicine service at an urban, academic medical center with 873 beds. This busy service was responsible for 10,225 admissions in 2008. Patients of age 18 years or older and cared for by a hospitalist or teaching team led by a hospitalist were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included patient confusion, physiological instability, non‐English speaking, patient unable to communicate, or patient in isolation status. Interviews were conducted in the patient's private room with no other staff present.

Patient perception of communication with hospitalists was measured with the CAT.17 This 15‐item survey is written at a fourth grade reading level, and measures responses along a 5‐point scale (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent). The CAT was originally field tested with a convenience sample of 38 physicians from various regions within the US, across 6 specialties (Dermatology, Family Medicine, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, and Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation). Each physician's office recruited 25 patients to complete the CAT through a phone or Internet‐based system.

The 14 core items of the CAT, which focus on communication with the individual physician, were used in this study. The 15th item, The doctor's staff treated me with respect, was dropped as it does not reflect the inpatient setting. Results for each physician are reported as the percentage of excellent responses. This dichotomized scoring is consistent with the development study, where analysis with Andrich's rating scale model19, 20 indicated that excellent scores correspond to a yes response while poor through very good scores correspond to a no response. This method of reporting scores as a percentage of excellent responses was found to be more useful for summarizing physician scores than reporting mean scores, which are highly skewed towards positive performance.17

Interviews were conducted by trained research assistants during hospitalists' weekday shifts. Hospitalists were not told which patients would be recruited, but were aware that patients on the service were being interviewed to assess communication. A list of patient names, room numbers, dates of admission, and assigned hospitalists was obtained daily from the electronic medical record system. Patients were approached on the second or third day of the hospital admission, and only if they had been assigned to the same hospitalist for at least 2 consecutive days. After explaining the study to patients and receiving verbal consent, researchers verified that the patient recognized the hospitalist, providing a photo if necessary. Patients who were not confident of their hospitalist's identity were excluded.

The 14 core items of the CAT survey were read aloud to the patient, who was provided with a copy of the instrument's scale and asked to respond with a number or word description (1 = poor to 5 = excellent). Patients were allowed to skip any questions they did not wish to answer. At the conclusion of the survey, patients were asked if they had any further comments to add. Patient demographics as well as hospitalist service (general or teaching) and unit were recorded. Most interviews were completed in less than 5 minutes. Based on the recommendations of the original development and validation of the CAT,17 we collected 20 patient surveys for each hospitalist. For CAT items that the patients skipped, we did not impute values; rather the percentage of excellent responses was calculated based on the number of questions the patient answered. To examine basic psychometric characteristics, we assessed scale reliability and performed a factor analysis using the principal components method of extraction with Varimax rotation.

This project was determined exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 1,137 patients as potentially eligible for the study. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of patient exclusion. Of note, 107 patients consenting to participate (13% overall) were unable to identify their hospitalist by name or photo. More specifically, 70 teaching service patients (25% of 275 eligible patients) were unable to identify their hospitalist, compared to 37 patients on general service (7% of 553 eligible patients); (z = 7.58, P < 0.001). Another 21 (3%) declined to participate because they had not talked enough with their doctor to render an assessment.

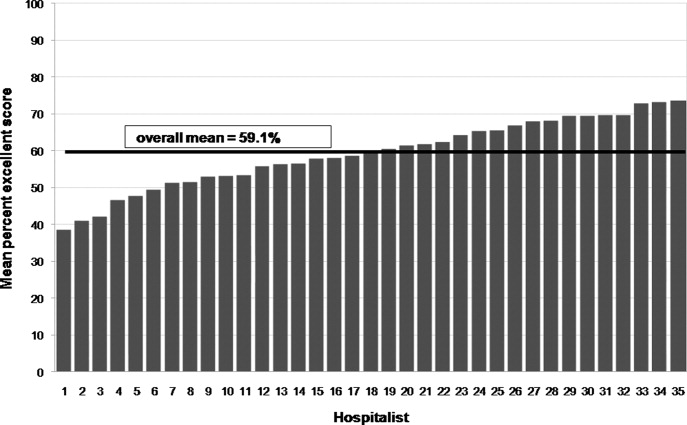

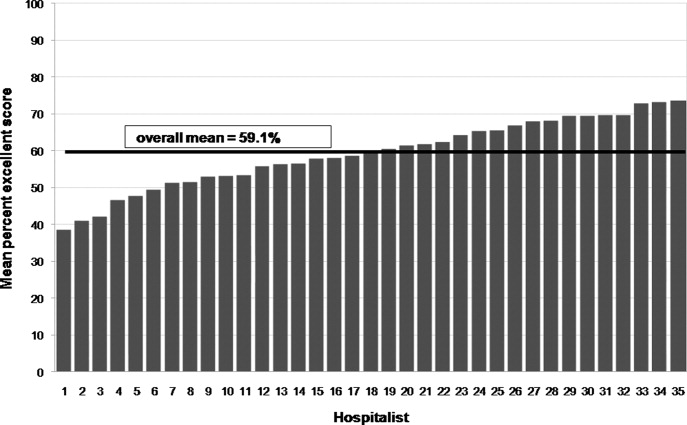

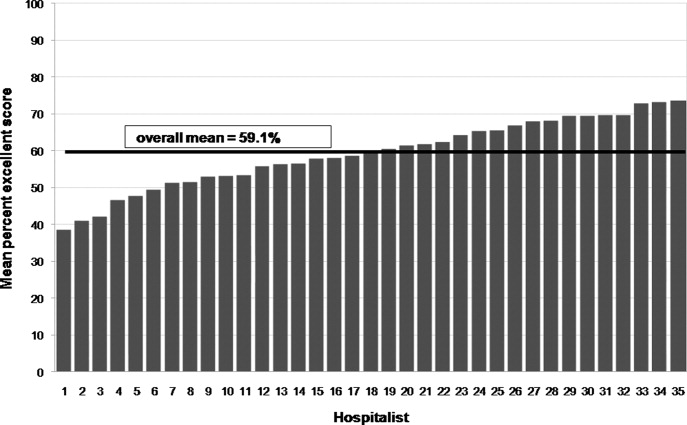

We analyzed 700 patient surveys (20 patients for each of 35 hospitalists; 62% of patients identified). Patient and hospitalist characteristics are presented in Table 1. The proportion of excellent ratings for each hospitalist ranged from 38.5% to 73.5% with an average of 59.1% excellent (standard deviation [SD] = 9.5). See Figure 2 for the distribution of hospitalist scores. For the group as a whole, highest ratings on individual CAT items were for treating the patient with respect (66% excellent), letting the patient talk without interruptions (66%), and talking in terms the patient can understand (64%). Lowest ratings were for involving the patient in decisions as much as he or she wanted (53%), encouraging the patient to ask questions (53%), and greeting the patient in a way that made him or her feel comfortable (55%). Table 2 contains a full ranking of individual item scores.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n =700), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 378 (54) |

| Age, years | |

| 44 and younger | 189 (27) |

| 45‐64 | 266 (38) |

| 65 and older | 245 (35) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 357 (51) |

| African American | 266 (38) |

| Hispanic | 49 (7) |

| Other | 28 (4) |

| Hospitalists (n = 35), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 18 (51) |

| Age, years | |

| Range | 3039 |

| Mean (SD) | 33 (2.4) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 14 (40) |

| South Asian | 11 (31) |

| Asian | 7 (20) |

| African American | 3 (9) |

| Non‐native English speaker | 5 (14) |

| Foreign medical graduate | 3 (9) |

| Communication Assessment Tool Item | Percent Excellent Scores |

|---|---|

| 1. Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable | 54.9 |

| 2. Treated me with respect | 66.3 |

| 3. Showed interest in my ideas about my health | 58.2 |

| 4. Understood my main health concerns | 57.4 |

| 5. Paid attention to me (looked at me, listened carefully) | 64.1 |

| 6. Let me talk without interruptions | 66.3 |

| 7. Gave me as much information as I wanted | 56.0 |

| 8. Talked in terms I could understand | 64.2 |

| 9. Checked to be sure I understood everything | 57.1 |

| 10. Encouraged me to ask questions | 53.2 |

| 11. Involved me in decisions as much as I wanted | 52.9 |

| 12. Discussed next steps including any follow‐up plans | 58.2 |

| 13. Showed care and concern | 63.8 |

| 14. Spent the right amount of time with me | 57.0 |

Overall scale reliability proved to be high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.97) in this sample. The factor analysis showed that scores for each of the 14 items load onto 1 factor. These results are consistent with the high reliability and single‐factor loading found in Makoul's original scale reliability and validity testing.17

The ad hoc comments made by patients at the conclusion of the CAT survey were categorized as positive or negative. Although many positive comments were made, they tended to be general in nature (eg, She is a great doctor). Negative comments were more explicit. A total of 110 patients (16%) made specific negative comments, which fell into 7 general domains: lack of information (35 comments), not enough time spent with the patient (27 comments), poor listening to the patient (24 comments), ineffective care delivery (7 comments), issues of care, concern, and respect (6 comments), ineffective communication with other staff (5 comments), and unclear role of physician (3 comments). Three patient comments were not related to these domains.

Patient age, race or gender did not correlate with CAT results. Hospitalist factors of age, race, gender, years of experience also were not associated with differences in ratings. However, race concordance between the patient and hospitalist was associated with improved CAT ratings. Patients of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist's communication significantly higher (M = 64.9%, SD = 39.1) than did patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist (M = 57.3%, SD = 40.3), P < 0.05. Gender concordance was not associated with improved CAT ratings. No score differences were found between patients cared for by a hospitalist on teaching service and direct care, and there were no differences between nursing units.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly measure patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists. The results yielded a wide distribution of scores for physicians within a single, large hospital medicine group. Comparing their own scores to those of peers may allow low‐scoring hospitalists to grasp the potential for improving their communication with patients. Our reliability testing matched the results of the original development study,17 indicating very high overall scale reliability. This suggests that the CAT could be streamlined by dropping some of the survey items. However we agree with Makoul et al.17 that it is best to keep the full set as it provides specific information for physicians without placing undue burden on patients (ie, the CAT takes only 1‐2 min to complete). Individual item scores for each of the 14 CAT items highlight specific communication tasks where intervention may be targeted for individual hospitalists and the group as a whole. It may be feasible to utilize CAT results as an individual report card for physicians. While program leaders should be aware that implementation of the CAT requires standardized data collection, it may be possible to build this into existing structures such as the discharge process.

Interestingly, many patients could not recognize the hospitalist caring for them by name or photo. More than 1 in 10 patients (107 of 828; 13%) were unable to identify their hospitalist. This was more than 3 times as common on the teaching service, where the hospitalist is accompanied by house staff and the intern or resident is the primary physician for patient contact, compared to the service on which hospitalists directly take care of patients without residents. It is also troubling that another 3% of patients (21 of 828) stated they hadn't talked enough with their hospitalist to answer basic communication questions, when approached 2 or 3 days into the relationship. It may be telling that Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable was one of the lowest‐rated survey items. Hospitalists should recognize that patients, in addition to facing their own physical and emotional stressors, see many hospital staff members throughout the day; all of whom may be strangers to them. Thus it becomes vital for hospitalists to not only establish an initial rapport with the patient, but to reintroduce themselves each time they enter the room.

An examination of the ad hoc negative comments made by survey respondents reinforces and extends findings related to the CAT items, particularly about those areas of communication valued by patients. The majority of comments fell into categories of failing to give enough information (eg, Sometimes I was left confused when the doctor was ready to leave), not spending enough time with the patient (eg, He was just in and out), and not listening to the patient's own ideas (eg, When giving my history, she cut me off at some points when I had more to say). The information and time categories may directly relate to scores on the CAT items Gave me as much information as I wanted and Spent the right amount of time with me, which are among the lowest‐scoring items. Listening to the patient may reflect broader issues of considering the patient's own experience, questions, concerns and goals.

In this study, patient‐physician race concordance was associated with CAT ratings. Patients who were of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist higher compared to patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist. This effect is consistent with previous research describing higher patient ratings of communication and care when the patient and physician are of the same race or ethnicity.21

A number of factors limit interpretation of the results of this study. The data were collected at a single site, thus limiting generalizability to other hospitalist practice environments. We used a retrospective, patient assessment of hospitalist communication which may have inherent biases different from a study using direct researcher observation or recording of patient‐hospitalist interactions to assess communication. This methodology allowed us to examine the patient's own perceptions and expectations of communication, but certainly leaves room for selection bias in recruitment and recall bias. Patients were interviewed on the second or third day of their admission. This controlled the length of exposure to the hospitalist, but the course of treatment might vary considerably; at the time of interview, some patients may not yet have had a clear diagnosis and plan while others may have been ready for discharge. Future work should examine how stage of evaluation and management might affect patients' perception of communication with hospitalists. Severity of condition is another factor that may affect patients' ratings, and was not examined in this study.

When compared to physicians from the CAT development study's field test, this study sample of hospitalists scored much lower, 59.1% excellent vs. 76.3% (P < 0.001). A number of factors may account for some of these differences. The majority of patients in the original field test had multiple interactions with their physician, and rated their health status as good or very good. In contrast, hospitalized patients usually lack previous exposure to the hospitalist, and likely have poorer health status. Also, physicians in the original field test volunteered to participate, and patients completed the CAT survey through the Internet or phone response system, rather than through a face‐to‐face interview by trained research assistants. Another key difference is that field‐test patients answered the CAT within 1 day of their outpatient visit, while in this study patients were interviewed in the midst of their hospital admission and prior to completion of their hospital course. Finally, patients commonly choose their outpatient physician and can select someone else if dissatisfied with their communication skills, while hospitalized patients are assigned hospitalists based on availability. Thus, given this potential selection bias, outpatients could be expected to rate their personal physician higher.

Another possibility is that hospitalists are on average less skilled in patient communication than outpatient physicians. Given the transient nature of the inpatient relationship, hospitalists may not value developing rapport with patients, and may not make this a goal of patient care or seek extensive training in communication skills. In future research, evaluating hospitalists' training in and attitudes towards patient communication could be paired with communication assessment results.

Although it is beyond the scope of this study to assess precisely how these environmental and survey implementation factors may affect CAT summary scores, their importance is evident. Another hospital‐based implementation of the CAT tool, an evaluation of ED teams,18 utilized face‐to‐face interviews with trained research assistants. The study yielded results similar to our findings: the average percent excellent score for ED teams was 62.3%, vs. 58.2% percent excellent for our hospitalist group. Taken together, these study comparisons between the original field‐test, our hospitalist implementation, and the ED team implementation support the argument that factors of setting (inpatient vs. outpatient), mode of survey administration (face‐to‐face interview vs. self‐administration through phone or Internet), and shorter duration or course of patient‐physician interaction may be important considerations when implementing the CAT tool to assess physician communication skills, or attempting to set standards of minimally acceptable or desired scoring.

More work must be done to establish norms and/or minimally acceptable scores for hospitalists. Numerous factors of specialty, practice setting, survey implementation, patient variables, and even the expertise of who is setting the communication standards22 may strongly influence comparisons between physician groups, even within a single institution. Organizations seeking to establish norms or minimally acceptable scores for physician‐patient communication should be aware of these factors. As the original development study points out, standard‐setting studies could establish specialty‐specific and country‐specific norms as well as norms or standards for level‐of‐training (eg, medical students versus attending physicians).17

Conclusion

The previously validated CAT instrument appears to have reliable test characteristics and can be used to gauge patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills. Comparative scores between physicians of different specialties and settings should be interpreted cautiously as there may be confounding variables. Within our single institution, comparative scores between hospitalists, along with an examination of the hospitalist's individual item scores, may offer useful feedback for efforts aimed at enhancing communication. Many hospitalists in this study may benefit from targeted training to improve patient communication skills, particularly in the areas of encouraging questions and involving patients in decision making. Future qualitative research in the context of hospital medicine could identify specific communication techniques used by highly‐rated physicians, with the goal of developing tools for targeted improvement and determining impact on outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christie Edwards, Rachel Grayer and Caitlin Lawes for assistance with data collection, and Jie Peng for help with the analysis.

- ,,.Is the quality of the patient‐provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV?J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(6):661–665.

- ,,,,.Does physician communication influence older patients' diabetes self‐management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS).J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.2007;62(12):1435–1442.

- ,.Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis.Med Care.2009;47(8):826–834.

- ,.The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data.Ann Intern Med.1984;101(5):692–696.

- ,,,,.Does physician‐patient communication that aims at empowering patients improve clinical outcome? A case study.Patient Educ Couns.2006;61(2):299–306.

- .Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review.CMAJ.1995;152(9):1423–1433.

- .Evaluation of clinical competencies: basic certification, subspecialty certification, and recertification.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2000;79(5):478–480.

- ,,,,.General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education.Health Aff (Millwood).2002;21(5):103–111.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission Standards supporting effective communication, cultural competence, and patient‐centered care.2009:44.

- .Rapport and the hospitalist.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):31S–35S.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335(7):514–517.

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians.Ann Intern Med.1999;130(4 Pt 2):343–349.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,,.Communication problems for patients hospitalized with chest pain.J Gen Intern Med.1998;13(12):836–838.

- ,.End‐of‐life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms.Am J Med.2004;116(10):669–675.

- ,,.Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool.Patient Educ Couns.2007;67(3):333–342.

- ,,, et al.Patient perspectives on communication with the medical team: pilot study using the Communication Assessment Tool‐Team (CAT‐T).Patient Educ Couns.2008;73(2):220–223.

- .Understanding resistance to the data‐model relationship in Rasch's paradigm: a reflection for the next generation.J Appl Meas.2002;3(3):325–359.

- ,.Conditional pairwise estimation in the Rasch model for ordered response categories using principal components.J Appl Meas.2003;4(3):205–221.

- ,,,,,.Patient‐centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race.Ann Intern Med.2003;139(11):907–915.

- ,,,.The impact of judge selection on standard setting for a patient survey of physician communication skills.Acad Med.2008;83(10 Suppl):S17–S20.

Effective communication between patients and physicians improves a number of important outcomes including patient adherence to treatment,1‐3 quality of the medical history4 and clinical outcomes.1, 5, 6 Recognizing the importance of physician communication skills, the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Council for Graduate Medical Education and The Joint Commission all identify communication as a core competency for physicians.7‐9 For hospitalists and their patients, building a therapeutic partnership is challenged by the lack of a preexisting relationship and potential lack of patient history information, particularly psychosocial history.10 Other factors that complicate the relationships between hospitalists and their patients include acuity of illness, limited time course, and absence of or lack of input from patients' primary physicians.11

As a rapidly increasing percentage of hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists,12, 13 communication skills need to be directly assessed and addressed. As of 2006, at least 37% of all Medicare claims for inpatient evaluation and management services by general internists were attributed to hospitalists, and more than half of hospitalized Medicare patients are seen by hospitalists.14 Yet, a search of the MEDLINE database for articles published between 1965 and September 2009, querying hospitalist AND patient AND communication within the article title and abstract, yielded only 2 studies assessing hospitalist‐patient communication. A 1998 study15 compared patient‐reported communication problems with hospitalists versus continuity physicians involved with hospital care, and found that patients whose continuity physicians remained involved with care during the hospitalization were less likely to report communication problems than those patients who were cared for by a hospitalist alone. A 2004 study16 utilized chart documentation to compare the end‐of‐life care and communication provided by continuity physicians and hospitalists. Hospitalists were found to document end‐of‐life care discussions more often than continuity physicians, and were more likely to be present for these meetings, which may suggest improved end‐of‐life care. Neither of these hospitalist‐patient communication studies directly assessed patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists.

We undertook this study to explore patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), a psychometrically validated instrument for patient assessment of physician communication skills.17 The CAT was initially field tested in outpatient offices, omitting the inpatient experience. A 2008 study18 successfully adapted the CAT tool for use in assessing emergency department (ED) teams. Given the importance of physician‐patient communication when patients are sickest and most vulnerable in the hospital setting, we sought to establish a baseline assessment of patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists in our group. Second, we compared results of our CAT implementation with published results examining communication in other physician groups.

Methods

Between September 2008 and August 2009 we performed a cross‐sectional study of patients admitted to the hospital medicine service at an urban, academic medical center with 873 beds. This busy service was responsible for 10,225 admissions in 2008. Patients of age 18 years or older and cared for by a hospitalist or teaching team led by a hospitalist were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included patient confusion, physiological instability, non‐English speaking, patient unable to communicate, or patient in isolation status. Interviews were conducted in the patient's private room with no other staff present.

Patient perception of communication with hospitalists was measured with the CAT.17 This 15‐item survey is written at a fourth grade reading level, and measures responses along a 5‐point scale (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent). The CAT was originally field tested with a convenience sample of 38 physicians from various regions within the US, across 6 specialties (Dermatology, Family Medicine, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, and Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation). Each physician's office recruited 25 patients to complete the CAT through a phone or Internet‐based system.

The 14 core items of the CAT, which focus on communication with the individual physician, were used in this study. The 15th item, The doctor's staff treated me with respect, was dropped as it does not reflect the inpatient setting. Results for each physician are reported as the percentage of excellent responses. This dichotomized scoring is consistent with the development study, where analysis with Andrich's rating scale model19, 20 indicated that excellent scores correspond to a yes response while poor through very good scores correspond to a no response. This method of reporting scores as a percentage of excellent responses was found to be more useful for summarizing physician scores than reporting mean scores, which are highly skewed towards positive performance.17

Interviews were conducted by trained research assistants during hospitalists' weekday shifts. Hospitalists were not told which patients would be recruited, but were aware that patients on the service were being interviewed to assess communication. A list of patient names, room numbers, dates of admission, and assigned hospitalists was obtained daily from the electronic medical record system. Patients were approached on the second or third day of the hospital admission, and only if they had been assigned to the same hospitalist for at least 2 consecutive days. After explaining the study to patients and receiving verbal consent, researchers verified that the patient recognized the hospitalist, providing a photo if necessary. Patients who were not confident of their hospitalist's identity were excluded.

The 14 core items of the CAT survey were read aloud to the patient, who was provided with a copy of the instrument's scale and asked to respond with a number or word description (1 = poor to 5 = excellent). Patients were allowed to skip any questions they did not wish to answer. At the conclusion of the survey, patients were asked if they had any further comments to add. Patient demographics as well as hospitalist service (general or teaching) and unit were recorded. Most interviews were completed in less than 5 minutes. Based on the recommendations of the original development and validation of the CAT,17 we collected 20 patient surveys for each hospitalist. For CAT items that the patients skipped, we did not impute values; rather the percentage of excellent responses was calculated based on the number of questions the patient answered. To examine basic psychometric characteristics, we assessed scale reliability and performed a factor analysis using the principal components method of extraction with Varimax rotation.

This project was determined exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 1,137 patients as potentially eligible for the study. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of patient exclusion. Of note, 107 patients consenting to participate (13% overall) were unable to identify their hospitalist by name or photo. More specifically, 70 teaching service patients (25% of 275 eligible patients) were unable to identify their hospitalist, compared to 37 patients on general service (7% of 553 eligible patients); (z = 7.58, P < 0.001). Another 21 (3%) declined to participate because they had not talked enough with their doctor to render an assessment.

We analyzed 700 patient surveys (20 patients for each of 35 hospitalists; 62% of patients identified). Patient and hospitalist characteristics are presented in Table 1. The proportion of excellent ratings for each hospitalist ranged from 38.5% to 73.5% with an average of 59.1% excellent (standard deviation [SD] = 9.5). See Figure 2 for the distribution of hospitalist scores. For the group as a whole, highest ratings on individual CAT items were for treating the patient with respect (66% excellent), letting the patient talk without interruptions (66%), and talking in terms the patient can understand (64%). Lowest ratings were for involving the patient in decisions as much as he or she wanted (53%), encouraging the patient to ask questions (53%), and greeting the patient in a way that made him or her feel comfortable (55%). Table 2 contains a full ranking of individual item scores.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n =700), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 378 (54) |

| Age, years | |

| 44 and younger | 189 (27) |

| 45‐64 | 266 (38) |

| 65 and older | 245 (35) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 357 (51) |

| African American | 266 (38) |

| Hispanic | 49 (7) |

| Other | 28 (4) |

| Hospitalists (n = 35), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 18 (51) |

| Age, years | |

| Range | 3039 |

| Mean (SD) | 33 (2.4) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 14 (40) |

| South Asian | 11 (31) |

| Asian | 7 (20) |

| African American | 3 (9) |

| Non‐native English speaker | 5 (14) |

| Foreign medical graduate | 3 (9) |

| Communication Assessment Tool Item | Percent Excellent Scores |

|---|---|

| 1. Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable | 54.9 |

| 2. Treated me with respect | 66.3 |

| 3. Showed interest in my ideas about my health | 58.2 |

| 4. Understood my main health concerns | 57.4 |

| 5. Paid attention to me (looked at me, listened carefully) | 64.1 |

| 6. Let me talk without interruptions | 66.3 |

| 7. Gave me as much information as I wanted | 56.0 |

| 8. Talked in terms I could understand | 64.2 |

| 9. Checked to be sure I understood everything | 57.1 |

| 10. Encouraged me to ask questions | 53.2 |

| 11. Involved me in decisions as much as I wanted | 52.9 |

| 12. Discussed next steps including any follow‐up plans | 58.2 |

| 13. Showed care and concern | 63.8 |

| 14. Spent the right amount of time with me | 57.0 |

Overall scale reliability proved to be high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.97) in this sample. The factor analysis showed that scores for each of the 14 items load onto 1 factor. These results are consistent with the high reliability and single‐factor loading found in Makoul's original scale reliability and validity testing.17

The ad hoc comments made by patients at the conclusion of the CAT survey were categorized as positive or negative. Although many positive comments were made, they tended to be general in nature (eg, She is a great doctor). Negative comments were more explicit. A total of 110 patients (16%) made specific negative comments, which fell into 7 general domains: lack of information (35 comments), not enough time spent with the patient (27 comments), poor listening to the patient (24 comments), ineffective care delivery (7 comments), issues of care, concern, and respect (6 comments), ineffective communication with other staff (5 comments), and unclear role of physician (3 comments). Three patient comments were not related to these domains.

Patient age, race or gender did not correlate with CAT results. Hospitalist factors of age, race, gender, years of experience also were not associated with differences in ratings. However, race concordance between the patient and hospitalist was associated with improved CAT ratings. Patients of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist's communication significantly higher (M = 64.9%, SD = 39.1) than did patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist (M = 57.3%, SD = 40.3), P < 0.05. Gender concordance was not associated with improved CAT ratings. No score differences were found between patients cared for by a hospitalist on teaching service and direct care, and there were no differences between nursing units.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly measure patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists. The results yielded a wide distribution of scores for physicians within a single, large hospital medicine group. Comparing their own scores to those of peers may allow low‐scoring hospitalists to grasp the potential for improving their communication with patients. Our reliability testing matched the results of the original development study,17 indicating very high overall scale reliability. This suggests that the CAT could be streamlined by dropping some of the survey items. However we agree with Makoul et al.17 that it is best to keep the full set as it provides specific information for physicians without placing undue burden on patients (ie, the CAT takes only 1‐2 min to complete). Individual item scores for each of the 14 CAT items highlight specific communication tasks where intervention may be targeted for individual hospitalists and the group as a whole. It may be feasible to utilize CAT results as an individual report card for physicians. While program leaders should be aware that implementation of the CAT requires standardized data collection, it may be possible to build this into existing structures such as the discharge process.

Interestingly, many patients could not recognize the hospitalist caring for them by name or photo. More than 1 in 10 patients (107 of 828; 13%) were unable to identify their hospitalist. This was more than 3 times as common on the teaching service, where the hospitalist is accompanied by house staff and the intern or resident is the primary physician for patient contact, compared to the service on which hospitalists directly take care of patients without residents. It is also troubling that another 3% of patients (21 of 828) stated they hadn't talked enough with their hospitalist to answer basic communication questions, when approached 2 or 3 days into the relationship. It may be telling that Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable was one of the lowest‐rated survey items. Hospitalists should recognize that patients, in addition to facing their own physical and emotional stressors, see many hospital staff members throughout the day; all of whom may be strangers to them. Thus it becomes vital for hospitalists to not only establish an initial rapport with the patient, but to reintroduce themselves each time they enter the room.

An examination of the ad hoc negative comments made by survey respondents reinforces and extends findings related to the CAT items, particularly about those areas of communication valued by patients. The majority of comments fell into categories of failing to give enough information (eg, Sometimes I was left confused when the doctor was ready to leave), not spending enough time with the patient (eg, He was just in and out), and not listening to the patient's own ideas (eg, When giving my history, she cut me off at some points when I had more to say). The information and time categories may directly relate to scores on the CAT items Gave me as much information as I wanted and Spent the right amount of time with me, which are among the lowest‐scoring items. Listening to the patient may reflect broader issues of considering the patient's own experience, questions, concerns and goals.

In this study, patient‐physician race concordance was associated with CAT ratings. Patients who were of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist higher compared to patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist. This effect is consistent with previous research describing higher patient ratings of communication and care when the patient and physician are of the same race or ethnicity.21

A number of factors limit interpretation of the results of this study. The data were collected at a single site, thus limiting generalizability to other hospitalist practice environments. We used a retrospective, patient assessment of hospitalist communication which may have inherent biases different from a study using direct researcher observation or recording of patient‐hospitalist interactions to assess communication. This methodology allowed us to examine the patient's own perceptions and expectations of communication, but certainly leaves room for selection bias in recruitment and recall bias. Patients were interviewed on the second or third day of their admission. This controlled the length of exposure to the hospitalist, but the course of treatment might vary considerably; at the time of interview, some patients may not yet have had a clear diagnosis and plan while others may have been ready for discharge. Future work should examine how stage of evaluation and management might affect patients' perception of communication with hospitalists. Severity of condition is another factor that may affect patients' ratings, and was not examined in this study.

When compared to physicians from the CAT development study's field test, this study sample of hospitalists scored much lower, 59.1% excellent vs. 76.3% (P < 0.001). A number of factors may account for some of these differences. The majority of patients in the original field test had multiple interactions with their physician, and rated their health status as good or very good. In contrast, hospitalized patients usually lack previous exposure to the hospitalist, and likely have poorer health status. Also, physicians in the original field test volunteered to participate, and patients completed the CAT survey through the Internet or phone response system, rather than through a face‐to‐face interview by trained research assistants. Another key difference is that field‐test patients answered the CAT within 1 day of their outpatient visit, while in this study patients were interviewed in the midst of their hospital admission and prior to completion of their hospital course. Finally, patients commonly choose their outpatient physician and can select someone else if dissatisfied with their communication skills, while hospitalized patients are assigned hospitalists based on availability. Thus, given this potential selection bias, outpatients could be expected to rate their personal physician higher.

Another possibility is that hospitalists are on average less skilled in patient communication than outpatient physicians. Given the transient nature of the inpatient relationship, hospitalists may not value developing rapport with patients, and may not make this a goal of patient care or seek extensive training in communication skills. In future research, evaluating hospitalists' training in and attitudes towards patient communication could be paired with communication assessment results.

Although it is beyond the scope of this study to assess precisely how these environmental and survey implementation factors may affect CAT summary scores, their importance is evident. Another hospital‐based implementation of the CAT tool, an evaluation of ED teams,18 utilized face‐to‐face interviews with trained research assistants. The study yielded results similar to our findings: the average percent excellent score for ED teams was 62.3%, vs. 58.2% percent excellent for our hospitalist group. Taken together, these study comparisons between the original field‐test, our hospitalist implementation, and the ED team implementation support the argument that factors of setting (inpatient vs. outpatient), mode of survey administration (face‐to‐face interview vs. self‐administration through phone or Internet), and shorter duration or course of patient‐physician interaction may be important considerations when implementing the CAT tool to assess physician communication skills, or attempting to set standards of minimally acceptable or desired scoring.

More work must be done to establish norms and/or minimally acceptable scores for hospitalists. Numerous factors of specialty, practice setting, survey implementation, patient variables, and even the expertise of who is setting the communication standards22 may strongly influence comparisons between physician groups, even within a single institution. Organizations seeking to establish norms or minimally acceptable scores for physician‐patient communication should be aware of these factors. As the original development study points out, standard‐setting studies could establish specialty‐specific and country‐specific norms as well as norms or standards for level‐of‐training (eg, medical students versus attending physicians).17

Conclusion

The previously validated CAT instrument appears to have reliable test characteristics and can be used to gauge patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills. Comparative scores between physicians of different specialties and settings should be interpreted cautiously as there may be confounding variables. Within our single institution, comparative scores between hospitalists, along with an examination of the hospitalist's individual item scores, may offer useful feedback for efforts aimed at enhancing communication. Many hospitalists in this study may benefit from targeted training to improve patient communication skills, particularly in the areas of encouraging questions and involving patients in decision making. Future qualitative research in the context of hospital medicine could identify specific communication techniques used by highly‐rated physicians, with the goal of developing tools for targeted improvement and determining impact on outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christie Edwards, Rachel Grayer and Caitlin Lawes for assistance with data collection, and Jie Peng for help with the analysis.

Effective communication between patients and physicians improves a number of important outcomes including patient adherence to treatment,1‐3 quality of the medical history4 and clinical outcomes.1, 5, 6 Recognizing the importance of physician communication skills, the American Board of Medical Specialties, American Council for Graduate Medical Education and The Joint Commission all identify communication as a core competency for physicians.7‐9 For hospitalists and their patients, building a therapeutic partnership is challenged by the lack of a preexisting relationship and potential lack of patient history information, particularly psychosocial history.10 Other factors that complicate the relationships between hospitalists and their patients include acuity of illness, limited time course, and absence of or lack of input from patients' primary physicians.11

As a rapidly increasing percentage of hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists,12, 13 communication skills need to be directly assessed and addressed. As of 2006, at least 37% of all Medicare claims for inpatient evaluation and management services by general internists were attributed to hospitalists, and more than half of hospitalized Medicare patients are seen by hospitalists.14 Yet, a search of the MEDLINE database for articles published between 1965 and September 2009, querying hospitalist AND patient AND communication within the article title and abstract, yielded only 2 studies assessing hospitalist‐patient communication. A 1998 study15 compared patient‐reported communication problems with hospitalists versus continuity physicians involved with hospital care, and found that patients whose continuity physicians remained involved with care during the hospitalization were less likely to report communication problems than those patients who were cared for by a hospitalist alone. A 2004 study16 utilized chart documentation to compare the end‐of‐life care and communication provided by continuity physicians and hospitalists. Hospitalists were found to document end‐of‐life care discussions more often than continuity physicians, and were more likely to be present for these meetings, which may suggest improved end‐of‐life care. Neither of these hospitalist‐patient communication studies directly assessed patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists.

We undertook this study to explore patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists using the Communication Assessment Tool (CAT), a psychometrically validated instrument for patient assessment of physician communication skills.17 The CAT was initially field tested in outpatient offices, omitting the inpatient experience. A 2008 study18 successfully adapted the CAT tool for use in assessing emergency department (ED) teams. Given the importance of physician‐patient communication when patients are sickest and most vulnerable in the hospital setting, we sought to establish a baseline assessment of patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists in our group. Second, we compared results of our CAT implementation with published results examining communication in other physician groups.

Methods

Between September 2008 and August 2009 we performed a cross‐sectional study of patients admitted to the hospital medicine service at an urban, academic medical center with 873 beds. This busy service was responsible for 10,225 admissions in 2008. Patients of age 18 years or older and cared for by a hospitalist or teaching team led by a hospitalist were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included patient confusion, physiological instability, non‐English speaking, patient unable to communicate, or patient in isolation status. Interviews were conducted in the patient's private room with no other staff present.

Patient perception of communication with hospitalists was measured with the CAT.17 This 15‐item survey is written at a fourth grade reading level, and measures responses along a 5‐point scale (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent). The CAT was originally field tested with a convenience sample of 38 physicians from various regions within the US, across 6 specialties (Dermatology, Family Medicine, Neurosurgery, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, and Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation). Each physician's office recruited 25 patients to complete the CAT through a phone or Internet‐based system.

The 14 core items of the CAT, which focus on communication with the individual physician, were used in this study. The 15th item, The doctor's staff treated me with respect, was dropped as it does not reflect the inpatient setting. Results for each physician are reported as the percentage of excellent responses. This dichotomized scoring is consistent with the development study, where analysis with Andrich's rating scale model19, 20 indicated that excellent scores correspond to a yes response while poor through very good scores correspond to a no response. This method of reporting scores as a percentage of excellent responses was found to be more useful for summarizing physician scores than reporting mean scores, which are highly skewed towards positive performance.17

Interviews were conducted by trained research assistants during hospitalists' weekday shifts. Hospitalists were not told which patients would be recruited, but were aware that patients on the service were being interviewed to assess communication. A list of patient names, room numbers, dates of admission, and assigned hospitalists was obtained daily from the electronic medical record system. Patients were approached on the second or third day of the hospital admission, and only if they had been assigned to the same hospitalist for at least 2 consecutive days. After explaining the study to patients and receiving verbal consent, researchers verified that the patient recognized the hospitalist, providing a photo if necessary. Patients who were not confident of their hospitalist's identity were excluded.

The 14 core items of the CAT survey were read aloud to the patient, who was provided with a copy of the instrument's scale and asked to respond with a number or word description (1 = poor to 5 = excellent). Patients were allowed to skip any questions they did not wish to answer. At the conclusion of the survey, patients were asked if they had any further comments to add. Patient demographics as well as hospitalist service (general or teaching) and unit were recorded. Most interviews were completed in less than 5 minutes. Based on the recommendations of the original development and validation of the CAT,17 we collected 20 patient surveys for each hospitalist. For CAT items that the patients skipped, we did not impute values; rather the percentage of excellent responses was calculated based on the number of questions the patient answered. To examine basic psychometric characteristics, we assessed scale reliability and performed a factor analysis using the principal components method of extraction with Varimax rotation.

This project was determined exempt by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Results

We identified 1,137 patients as potentially eligible for the study. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of patient exclusion. Of note, 107 patients consenting to participate (13% overall) were unable to identify their hospitalist by name or photo. More specifically, 70 teaching service patients (25% of 275 eligible patients) were unable to identify their hospitalist, compared to 37 patients on general service (7% of 553 eligible patients); (z = 7.58, P < 0.001). Another 21 (3%) declined to participate because they had not talked enough with their doctor to render an assessment.

We analyzed 700 patient surveys (20 patients for each of 35 hospitalists; 62% of patients identified). Patient and hospitalist characteristics are presented in Table 1. The proportion of excellent ratings for each hospitalist ranged from 38.5% to 73.5% with an average of 59.1% excellent (standard deviation [SD] = 9.5). See Figure 2 for the distribution of hospitalist scores. For the group as a whole, highest ratings on individual CAT items were for treating the patient with respect (66% excellent), letting the patient talk without interruptions (66%), and talking in terms the patient can understand (64%). Lowest ratings were for involving the patient in decisions as much as he or she wanted (53%), encouraging the patient to ask questions (53%), and greeting the patient in a way that made him or her feel comfortable (55%). Table 2 contains a full ranking of individual item scores.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Patients (n =700), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 378 (54) |

| Age, years | |

| 44 and younger | 189 (27) |

| 45‐64 | 266 (38) |

| 65 and older | 245 (35) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 357 (51) |

| African American | 266 (38) |

| Hispanic | 49 (7) |

| Other | 28 (4) |

| Hospitalists (n = 35), n (%) | |

| Sex, female | 18 (51) |

| Age, years | |

| Range | 3039 |

| Mean (SD) | 33 (2.4) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 14 (40) |

| South Asian | 11 (31) |

| Asian | 7 (20) |

| African American | 3 (9) |

| Non‐native English speaker | 5 (14) |

| Foreign medical graduate | 3 (9) |

| Communication Assessment Tool Item | Percent Excellent Scores |

|---|---|

| 1. Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable | 54.9 |

| 2. Treated me with respect | 66.3 |

| 3. Showed interest in my ideas about my health | 58.2 |

| 4. Understood my main health concerns | 57.4 |

| 5. Paid attention to me (looked at me, listened carefully) | 64.1 |

| 6. Let me talk without interruptions | 66.3 |

| 7. Gave me as much information as I wanted | 56.0 |

| 8. Talked in terms I could understand | 64.2 |

| 9. Checked to be sure I understood everything | 57.1 |

| 10. Encouraged me to ask questions | 53.2 |

| 11. Involved me in decisions as much as I wanted | 52.9 |

| 12. Discussed next steps including any follow‐up plans | 58.2 |

| 13. Showed care and concern | 63.8 |

| 14. Spent the right amount of time with me | 57.0 |

Overall scale reliability proved to be high (Cronbach's alpha = 0.97) in this sample. The factor analysis showed that scores for each of the 14 items load onto 1 factor. These results are consistent with the high reliability and single‐factor loading found in Makoul's original scale reliability and validity testing.17

The ad hoc comments made by patients at the conclusion of the CAT survey were categorized as positive or negative. Although many positive comments were made, they tended to be general in nature (eg, She is a great doctor). Negative comments were more explicit. A total of 110 patients (16%) made specific negative comments, which fell into 7 general domains: lack of information (35 comments), not enough time spent with the patient (27 comments), poor listening to the patient (24 comments), ineffective care delivery (7 comments), issues of care, concern, and respect (6 comments), ineffective communication with other staff (5 comments), and unclear role of physician (3 comments). Three patient comments were not related to these domains.

Patient age, race or gender did not correlate with CAT results. Hospitalist factors of age, race, gender, years of experience also were not associated with differences in ratings. However, race concordance between the patient and hospitalist was associated with improved CAT ratings. Patients of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist's communication significantly higher (M = 64.9%, SD = 39.1) than did patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist (M = 57.3%, SD = 40.3), P < 0.05. Gender concordance was not associated with improved CAT ratings. No score differences were found between patients cared for by a hospitalist on teaching service and direct care, and there were no differences between nursing units.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly measure patient perceptions of communication with hospitalists. The results yielded a wide distribution of scores for physicians within a single, large hospital medicine group. Comparing their own scores to those of peers may allow low‐scoring hospitalists to grasp the potential for improving their communication with patients. Our reliability testing matched the results of the original development study,17 indicating very high overall scale reliability. This suggests that the CAT could be streamlined by dropping some of the survey items. However we agree with Makoul et al.17 that it is best to keep the full set as it provides specific information for physicians without placing undue burden on patients (ie, the CAT takes only 1‐2 min to complete). Individual item scores for each of the 14 CAT items highlight specific communication tasks where intervention may be targeted for individual hospitalists and the group as a whole. It may be feasible to utilize CAT results as an individual report card for physicians. While program leaders should be aware that implementation of the CAT requires standardized data collection, it may be possible to build this into existing structures such as the discharge process.

Interestingly, many patients could not recognize the hospitalist caring for them by name or photo. More than 1 in 10 patients (107 of 828; 13%) were unable to identify their hospitalist. This was more than 3 times as common on the teaching service, where the hospitalist is accompanied by house staff and the intern or resident is the primary physician for patient contact, compared to the service on which hospitalists directly take care of patients without residents. It is also troubling that another 3% of patients (21 of 828) stated they hadn't talked enough with their hospitalist to answer basic communication questions, when approached 2 or 3 days into the relationship. It may be telling that Greeted me in a way that made me feel comfortable was one of the lowest‐rated survey items. Hospitalists should recognize that patients, in addition to facing their own physical and emotional stressors, see many hospital staff members throughout the day; all of whom may be strangers to them. Thus it becomes vital for hospitalists to not only establish an initial rapport with the patient, but to reintroduce themselves each time they enter the room.

An examination of the ad hoc negative comments made by survey respondents reinforces and extends findings related to the CAT items, particularly about those areas of communication valued by patients. The majority of comments fell into categories of failing to give enough information (eg, Sometimes I was left confused when the doctor was ready to leave), not spending enough time with the patient (eg, He was just in and out), and not listening to the patient's own ideas (eg, When giving my history, she cut me off at some points when I had more to say). The information and time categories may directly relate to scores on the CAT items Gave me as much information as I wanted and Spent the right amount of time with me, which are among the lowest‐scoring items. Listening to the patient may reflect broader issues of considering the patient's own experience, questions, concerns and goals.

In this study, patient‐physician race concordance was associated with CAT ratings. Patients who were of the same race as their hospitalist rated the hospitalist higher compared to patients who were of a different race than their hospitalist. This effect is consistent with previous research describing higher patient ratings of communication and care when the patient and physician are of the same race or ethnicity.21

A number of factors limit interpretation of the results of this study. The data were collected at a single site, thus limiting generalizability to other hospitalist practice environments. We used a retrospective, patient assessment of hospitalist communication which may have inherent biases different from a study using direct researcher observation or recording of patient‐hospitalist interactions to assess communication. This methodology allowed us to examine the patient's own perceptions and expectations of communication, but certainly leaves room for selection bias in recruitment and recall bias. Patients were interviewed on the second or third day of their admission. This controlled the length of exposure to the hospitalist, but the course of treatment might vary considerably; at the time of interview, some patients may not yet have had a clear diagnosis and plan while others may have been ready for discharge. Future work should examine how stage of evaluation and management might affect patients' perception of communication with hospitalists. Severity of condition is another factor that may affect patients' ratings, and was not examined in this study.

When compared to physicians from the CAT development study's field test, this study sample of hospitalists scored much lower, 59.1% excellent vs. 76.3% (P < 0.001). A number of factors may account for some of these differences. The majority of patients in the original field test had multiple interactions with their physician, and rated their health status as good or very good. In contrast, hospitalized patients usually lack previous exposure to the hospitalist, and likely have poorer health status. Also, physicians in the original field test volunteered to participate, and patients completed the CAT survey through the Internet or phone response system, rather than through a face‐to‐face interview by trained research assistants. Another key difference is that field‐test patients answered the CAT within 1 day of their outpatient visit, while in this study patients were interviewed in the midst of their hospital admission and prior to completion of their hospital course. Finally, patients commonly choose their outpatient physician and can select someone else if dissatisfied with their communication skills, while hospitalized patients are assigned hospitalists based on availability. Thus, given this potential selection bias, outpatients could be expected to rate their personal physician higher.

Another possibility is that hospitalists are on average less skilled in patient communication than outpatient physicians. Given the transient nature of the inpatient relationship, hospitalists may not value developing rapport with patients, and may not make this a goal of patient care or seek extensive training in communication skills. In future research, evaluating hospitalists' training in and attitudes towards patient communication could be paired with communication assessment results.

Although it is beyond the scope of this study to assess precisely how these environmental and survey implementation factors may affect CAT summary scores, their importance is evident. Another hospital‐based implementation of the CAT tool, an evaluation of ED teams,18 utilized face‐to‐face interviews with trained research assistants. The study yielded results similar to our findings: the average percent excellent score for ED teams was 62.3%, vs. 58.2% percent excellent for our hospitalist group. Taken together, these study comparisons between the original field‐test, our hospitalist implementation, and the ED team implementation support the argument that factors of setting (inpatient vs. outpatient), mode of survey administration (face‐to‐face interview vs. self‐administration through phone or Internet), and shorter duration or course of patient‐physician interaction may be important considerations when implementing the CAT tool to assess physician communication skills, or attempting to set standards of minimally acceptable or desired scoring.

More work must be done to establish norms and/or minimally acceptable scores for hospitalists. Numerous factors of specialty, practice setting, survey implementation, patient variables, and even the expertise of who is setting the communication standards22 may strongly influence comparisons between physician groups, even within a single institution. Organizations seeking to establish norms or minimally acceptable scores for physician‐patient communication should be aware of these factors. As the original development study points out, standard‐setting studies could establish specialty‐specific and country‐specific norms as well as norms or standards for level‐of‐training (eg, medical students versus attending physicians).17

Conclusion

The previously validated CAT instrument appears to have reliable test characteristics and can be used to gauge patient perceptions of hospitalist communication skills. Comparative scores between physicians of different specialties and settings should be interpreted cautiously as there may be confounding variables. Within our single institution, comparative scores between hospitalists, along with an examination of the hospitalist's individual item scores, may offer useful feedback for efforts aimed at enhancing communication. Many hospitalists in this study may benefit from targeted training to improve patient communication skills, particularly in the areas of encouraging questions and involving patients in decision making. Future qualitative research in the context of hospital medicine could identify specific communication techniques used by highly‐rated physicians, with the goal of developing tools for targeted improvement and determining impact on outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Christie Edwards, Rachel Grayer and Caitlin Lawes for assistance with data collection, and Jie Peng for help with the analysis.

- ,,.Is the quality of the patient‐provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV?J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(6):661–665.

- ,,,,.Does physician communication influence older patients' diabetes self‐management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS).J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.2007;62(12):1435–1442.

- ,.Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis.Med Care.2009;47(8):826–834.

- ,.The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data.Ann Intern Med.1984;101(5):692–696.

- ,,,,.Does physician‐patient communication that aims at empowering patients improve clinical outcome? A case study.Patient Educ Couns.2006;61(2):299–306.

- .Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review.CMAJ.1995;152(9):1423–1433.

- .Evaluation of clinical competencies: basic certification, subspecialty certification, and recertification.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2000;79(5):478–480.

- ,,,,.General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education.Health Aff (Millwood).2002;21(5):103–111.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission Standards supporting effective communication, cultural competence, and patient‐centered care.2009:44.

- .Rapport and the hospitalist.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):31S–35S.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335(7):514–517.

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians.Ann Intern Med.1999;130(4 Pt 2):343–349.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,,.Communication problems for patients hospitalized with chest pain.J Gen Intern Med.1998;13(12):836–838.

- ,.End‐of‐life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms.Am J Med.2004;116(10):669–675.

- ,,.Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool.Patient Educ Couns.2007;67(3):333–342.

- ,,, et al.Patient perspectives on communication with the medical team: pilot study using the Communication Assessment Tool‐Team (CAT‐T).Patient Educ Couns.2008;73(2):220–223.

- .Understanding resistance to the data‐model relationship in Rasch's paradigm: a reflection for the next generation.J Appl Meas.2002;3(3):325–359.

- ,.Conditional pairwise estimation in the Rasch model for ordered response categories using principal components.J Appl Meas.2003;4(3):205–221.

- ,,,,,.Patient‐centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race.Ann Intern Med.2003;139(11):907–915.

- ,,,.The impact of judge selection on standard setting for a patient survey of physician communication skills.Acad Med.2008;83(10 Suppl):S17–S20.

- ,,.Is the quality of the patient‐provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV?J Gen Intern Med.2006;21(6):661–665.

- ,,,,.Does physician communication influence older patients' diabetes self‐management and glycemic control? Results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS).J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci.2007;62(12):1435–1442.

- ,.Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis.Med Care.2009;47(8):826–834.

- ,.The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data.Ann Intern Med.1984;101(5):692–696.

- ,,,,.Does physician‐patient communication that aims at empowering patients improve clinical outcome? A case study.Patient Educ Couns.2006;61(2):299–306.

- .Effective physician‐patient communication and health outcomes: a review.CMAJ.1995;152(9):1423–1433.

- .Evaluation of clinical competencies: basic certification, subspecialty certification, and recertification.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2000;79(5):478–480.

- ,,,,.General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education.Health Aff (Millwood).2002;21(5):103–111.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission Standards supporting effective communication, cultural competence, and patient‐centered care.2009:44.

- .Rapport and the hospitalist.Am J Med.2001;111(9B):31S–35S.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335(7):514–517.

- ,,,.Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians.Ann Intern Med.1999;130(4 Pt 2):343–349.

- ,,,.The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States.J Hosp Med.2006;1:75–80.

- ,,,.Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States.N Engl J Med.2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- ,,,,.Communication problems for patients hospitalized with chest pain.J Gen Intern Med.1998;13(12):836–838.

- ,.End‐of‐life care in a voluntary hospitalist model: effects on communication, processes of care, and patient symptoms.Am J Med.2004;116(10):669–675.

- ,,.Measuring patient views of physician communication skills: development and testing of the Communication Assessment Tool.Patient Educ Couns.2007;67(3):333–342.

- ,,, et al.Patient perspectives on communication with the medical team: pilot study using the Communication Assessment Tool‐Team (CAT‐T).Patient Educ Couns.2008;73(2):220–223.

- .Understanding resistance to the data‐model relationship in Rasch's paradigm: a reflection for the next generation.J Appl Meas.2002;3(3):325–359.

- ,.Conditional pairwise estimation in the Rasch model for ordered response categories using principal components.J Appl Meas.2003;4(3):205–221.

- ,,,,,.Patient‐centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race.Ann Intern Med.2003;139(11):907–915.

- ,,,.The impact of judge selection on standard setting for a patient survey of physician communication skills.Acad Med.2008;83(10 Suppl):S17–S20.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine

Continuing Medical Education Program in

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, which begins on the next page, please refer to the website: www. blackwellpublishing.com/cme.

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this educational activity for a 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

Continuous participation in the Journal of Hospital Medicine CME program will enable learners to be better able to:

-

Interpret clinical guidelines and their applications for higher quality and more efficient care for all hospitalized patients.

-

Describe the standard of care for common illnesses and conditions treated in the hospital; such as pneumonia, COPD exacerbation, acute coronary syndrome, HF exacerbation, glycemic control, venous thromboembolic disease, stroke, etc.

-

Discuss evidence‐based recommendations involving transitions of care, including the hospital discharge process.

-

Gain insights into the roles of hospitalists as medical educators, researchers, medical ethicists, palliative care providers, and hospital‐based geriatricians.

-

Incorporate best practices for hospitalist administration, including quality improvement, patient safety, practice management, leadership, and demonstrating hospitalist value.

-

Identify evidence‐based best practices and trends for both adult and pediatric hospital medicine.

Instructions on Receiving Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing medical education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

This activity is designed to be completed within the time designated on the title page; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity during the valid credit period that is noted on the title page.

Follow these steps to earn credit:

-

Log on to www.blackwellpublishing.com/cme.

-

Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

-

Read the article in print or online format.

-

Reflect on the article.

-

Access the CME Exam, and choose the best answer to each question.

-

Complete the required evaluation component of the activity.

If you wish to receive credit for this activity, which begins on the next page, please refer to the website: www. blackwellpublishing.com/cme.

Accreditation and Designation Statement

Blackwell Futura Media Services designates this educational activity for a 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Blackwell Futura Media Services is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Educational Objectives

Continuous participation in the Journal of Hospital Medicine CME program will enable learners to be better able to:

-

Interpret clinical guidelines and their applications for higher quality and more efficient care for all hospitalized patients.

-

Describe the standard of care for common illnesses and conditions treated in the hospital; such as pneumonia, COPD exacerbation, acute coronary syndrome, HF exacerbation, glycemic control, venous thromboembolic disease, stroke, etc.

-

Discuss evidence‐based recommendations involving transitions of care, including the hospital discharge process.

-

Gain insights into the roles of hospitalists as medical educators, researchers, medical ethicists, palliative care providers, and hospital‐based geriatricians.

-

Incorporate best practices for hospitalist administration, including quality improvement, patient safety, practice management, leadership, and demonstrating hospitalist value.

-

Identify evidence‐based best practices and trends for both adult and pediatric hospital medicine.

Instructions on Receiving Credit