User login

The Chronic Effects of COVID-19 Hospitalizations: Learning How Patients Can Get “Back to Normal”

As our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 has progressed, researchers, clinicians, and patients have learned that recovery from COVID-19 can last well beyond the acute phase of the illness. As we see fewer fatal cases and more survivors, studies that characterize the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) are increasingly important for understanding how to help patients return to their normal lives, especially after hospitalization. Critical to investigating this is knowing patients’ burden of symptoms and disabilities prior to infection. In this issue, a study by Iwashyna et al1 helps us understand patients’ lives after COVID compared to their lives before COVID.

The study analyzed patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted during the third wave of the pandemic to assess for new cardiopulmonary symptoms, new disability, and financial toxicity of hospitalization 1 month after discharge.1 Many patients had new cardiopulmonary symptoms and oxygen use, and a much larger number had new limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs). The majority were discharged home without home care services, and new limitations in ADLs or iADLs were common in these cases. Most patients reported not having returned to their cardiopulmonary or functional baseline; however, new cough, shortness of breath, or oxygen use usually did not explain their new disabilities. Financial toxicity was also common, reflecting the effects of COVID-19 on both employment and family finances.

These results complement those of Chopra et al,2 who examined 60-day outcomes for patients hospitalized during the first wave of the pandemic. At 2 months from discharge, many patients had ongoing cough, shortness of breath, oxygen use, and disability, but at lower rates. This likely reflects continuing recovery during the extra 30 days, but other potential explanations deserve consideration. One possibility is improving survival over the course of the pandemic. Many patients who may have passed away earlier in the pandemic now survive to return home, albeit with a heavy burden of symptomatology. This raises the possibility that symptoms among survivors may continue to increase as survival of COVID-19 improves. However, it should be noted that neither study is representative of the national patterns of hospitalization by race or ethnicity.3 Iwashyna et al1 underrepresented Black patients, while Chopra et al2 underrepresented Hispanic patients. Given what we know about outcomes for these populations and their underrepresentation in PASC literature, the impact of COVID-19 for them is likely underestimated. As data from 3, 6, or 12 months become available, we may also see the effect sizes described in this early literature become even larger.

Consistent with the findings of Chopra et al,2 financial toxicity after COVID-19 hospitalization was high. The longer-term financial burden of COVID-19 will likely exceed what is described here, particularly for Black and Hispanic patients, who experienced a disproportionate drain on their savings. These populations are also more likely to be negatively impacted by the COVID economy4 and thus may suffer a “double hit” financially if hospitalized.

Iwashyna et al1 underscore the urgent need for progress in understanding COVID “long-haulers”5 and helping patients with physical and financial recovery. Whether the spectacular innovations identified by the medical community in COVID-19 prevention and treatment of acute illness can be found for long COVID remains to be seen. The fact that so many patients studied by Iwashyna et al did not receive home care services and experienced financial toxicity shows the importance of broader implementation of systems and services to support survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization. Developers of this support must emphasize the importance of physical and cardiopulmonary rehabilitation as well as financial relief, particularly for minorities. For our patients and their families, this may be the best strategy to get “back to normal.”

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for reviewing and advising on this manuscript.

1. Iwashyna TJ, Kamphuis LA, Gundel SJ, et al. Continuing cardiopulmonary symptoms, disability, and financial toxicity 1 month after hospitalization for third-wave COVID-19: early results from a US nationwide cohort. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(9):531-537. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3660

2. Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5661

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Updated July 16, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

4. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, NPR, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The impact of coronavirus on households by race/ethnicity. September 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/09/the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-households-across-america.html

5. Barber C. The problem of ‘long haul’ COVID. December 29, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-long-haul-covid/

As our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 has progressed, researchers, clinicians, and patients have learned that recovery from COVID-19 can last well beyond the acute phase of the illness. As we see fewer fatal cases and more survivors, studies that characterize the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) are increasingly important for understanding how to help patients return to their normal lives, especially after hospitalization. Critical to investigating this is knowing patients’ burden of symptoms and disabilities prior to infection. In this issue, a study by Iwashyna et al1 helps us understand patients’ lives after COVID compared to their lives before COVID.

The study analyzed patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted during the third wave of the pandemic to assess for new cardiopulmonary symptoms, new disability, and financial toxicity of hospitalization 1 month after discharge.1 Many patients had new cardiopulmonary symptoms and oxygen use, and a much larger number had new limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs). The majority were discharged home without home care services, and new limitations in ADLs or iADLs were common in these cases. Most patients reported not having returned to their cardiopulmonary or functional baseline; however, new cough, shortness of breath, or oxygen use usually did not explain their new disabilities. Financial toxicity was also common, reflecting the effects of COVID-19 on both employment and family finances.

These results complement those of Chopra et al,2 who examined 60-day outcomes for patients hospitalized during the first wave of the pandemic. At 2 months from discharge, many patients had ongoing cough, shortness of breath, oxygen use, and disability, but at lower rates. This likely reflects continuing recovery during the extra 30 days, but other potential explanations deserve consideration. One possibility is improving survival over the course of the pandemic. Many patients who may have passed away earlier in the pandemic now survive to return home, albeit with a heavy burden of symptomatology. This raises the possibility that symptoms among survivors may continue to increase as survival of COVID-19 improves. However, it should be noted that neither study is representative of the national patterns of hospitalization by race or ethnicity.3 Iwashyna et al1 underrepresented Black patients, while Chopra et al2 underrepresented Hispanic patients. Given what we know about outcomes for these populations and their underrepresentation in PASC literature, the impact of COVID-19 for them is likely underestimated. As data from 3, 6, or 12 months become available, we may also see the effect sizes described in this early literature become even larger.

Consistent with the findings of Chopra et al,2 financial toxicity after COVID-19 hospitalization was high. The longer-term financial burden of COVID-19 will likely exceed what is described here, particularly for Black and Hispanic patients, who experienced a disproportionate drain on their savings. These populations are also more likely to be negatively impacted by the COVID economy4 and thus may suffer a “double hit” financially if hospitalized.

Iwashyna et al1 underscore the urgent need for progress in understanding COVID “long-haulers”5 and helping patients with physical and financial recovery. Whether the spectacular innovations identified by the medical community in COVID-19 prevention and treatment of acute illness can be found for long COVID remains to be seen. The fact that so many patients studied by Iwashyna et al did not receive home care services and experienced financial toxicity shows the importance of broader implementation of systems and services to support survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization. Developers of this support must emphasize the importance of physical and cardiopulmonary rehabilitation as well as financial relief, particularly for minorities. For our patients and their families, this may be the best strategy to get “back to normal.”

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for reviewing and advising on this manuscript.

As our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 has progressed, researchers, clinicians, and patients have learned that recovery from COVID-19 can last well beyond the acute phase of the illness. As we see fewer fatal cases and more survivors, studies that characterize the postacute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) are increasingly important for understanding how to help patients return to their normal lives, especially after hospitalization. Critical to investigating this is knowing patients’ burden of symptoms and disabilities prior to infection. In this issue, a study by Iwashyna et al1 helps us understand patients’ lives after COVID compared to their lives before COVID.

The study analyzed patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection admitted during the third wave of the pandemic to assess for new cardiopulmonary symptoms, new disability, and financial toxicity of hospitalization 1 month after discharge.1 Many patients had new cardiopulmonary symptoms and oxygen use, and a much larger number had new limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental activities of daily living (iADLs). The majority were discharged home without home care services, and new limitations in ADLs or iADLs were common in these cases. Most patients reported not having returned to their cardiopulmonary or functional baseline; however, new cough, shortness of breath, or oxygen use usually did not explain their new disabilities. Financial toxicity was also common, reflecting the effects of COVID-19 on both employment and family finances.

These results complement those of Chopra et al,2 who examined 60-day outcomes for patients hospitalized during the first wave of the pandemic. At 2 months from discharge, many patients had ongoing cough, shortness of breath, oxygen use, and disability, but at lower rates. This likely reflects continuing recovery during the extra 30 days, but other potential explanations deserve consideration. One possibility is improving survival over the course of the pandemic. Many patients who may have passed away earlier in the pandemic now survive to return home, albeit with a heavy burden of symptomatology. This raises the possibility that symptoms among survivors may continue to increase as survival of COVID-19 improves. However, it should be noted that neither study is representative of the national patterns of hospitalization by race or ethnicity.3 Iwashyna et al1 underrepresented Black patients, while Chopra et al2 underrepresented Hispanic patients. Given what we know about outcomes for these populations and their underrepresentation in PASC literature, the impact of COVID-19 for them is likely underestimated. As data from 3, 6, or 12 months become available, we may also see the effect sizes described in this early literature become even larger.

Consistent with the findings of Chopra et al,2 financial toxicity after COVID-19 hospitalization was high. The longer-term financial burden of COVID-19 will likely exceed what is described here, particularly for Black and Hispanic patients, who experienced a disproportionate drain on their savings. These populations are also more likely to be negatively impacted by the COVID economy4 and thus may suffer a “double hit” financially if hospitalized.

Iwashyna et al1 underscore the urgent need for progress in understanding COVID “long-haulers”5 and helping patients with physical and financial recovery. Whether the spectacular innovations identified by the medical community in COVID-19 prevention and treatment of acute illness can be found for long COVID remains to be seen. The fact that so many patients studied by Iwashyna et al did not receive home care services and experienced financial toxicity shows the importance of broader implementation of systems and services to support survivors of COVID-19 hospitalization. Developers of this support must emphasize the importance of physical and cardiopulmonary rehabilitation as well as financial relief, particularly for minorities. For our patients and their families, this may be the best strategy to get “back to normal.”

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr Vineet Arora for reviewing and advising on this manuscript.

1. Iwashyna TJ, Kamphuis LA, Gundel SJ, et al. Continuing cardiopulmonary symptoms, disability, and financial toxicity 1 month after hospitalization for third-wave COVID-19: early results from a US nationwide cohort. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(9):531-537. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3660

2. Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5661

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Updated July 16, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

4. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, NPR, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The impact of coronavirus on households by race/ethnicity. September 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/09/the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-households-across-america.html

5. Barber C. The problem of ‘long haul’ COVID. December 29, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-long-haul-covid/

1. Iwashyna TJ, Kamphuis LA, Gundel SJ, et al. Continuing cardiopulmonary symptoms, disability, and financial toxicity 1 month after hospitalization for third-wave COVID-19: early results from a US nationwide cohort. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(9):531-537. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3660

2. Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(4):576-578. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5661

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Updated July 16, 2021. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

4. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, NPR, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The impact of coronavirus on households by race/ethnicity. September 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/09/the-impact-of-coronavirus-on-households-across-america.html

5. Barber C. The problem of ‘long haul’ COVID. December 29, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-problem-of-long-haul-covid/

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Defining Potential Overutilization of Physical Therapy Consults on Hospital Medicine Services

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

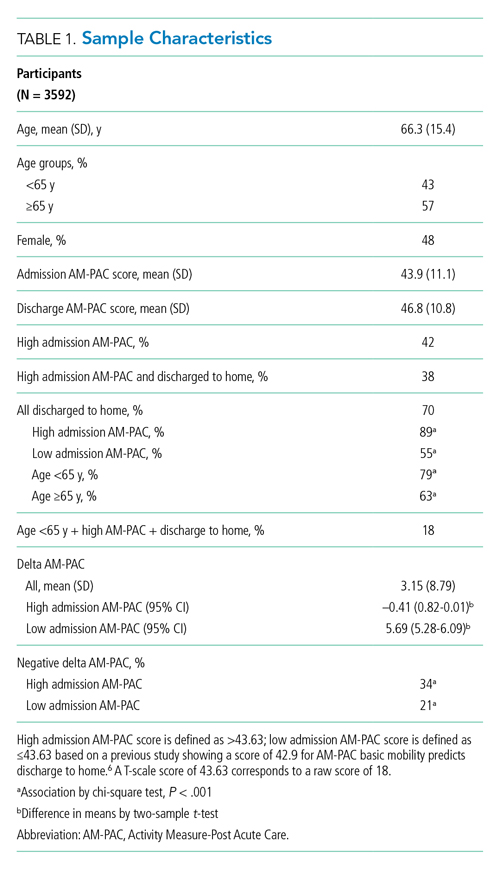

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

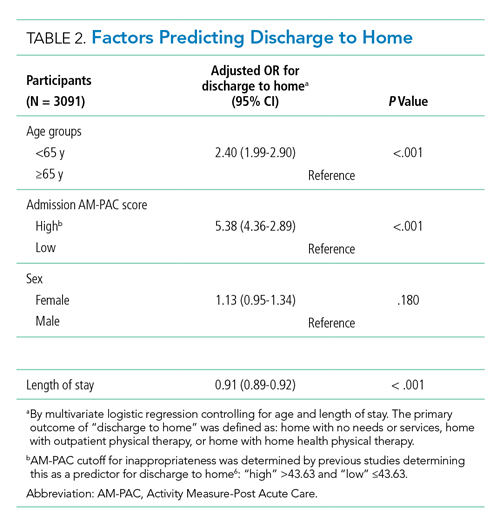

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

During hospitalization, patients spend 87% to 100% of their time in bed.1 This prolonged immobilization is a key contributor to the development of hospital-associated disability (HAD), defined as a new loss of ability to complete one or more activities of daily living (ADLs) without assistance after hospital discharge. HAD can lead to readmissions, institutionalization, and death and occurs in approximately one-third of all hospitalized patients.2,3 The most effective way to prevent HAD is by mobilizing patients early and throughout their hospitalization.4 Typically, physical therapists are the primary team members responsible for mobilizing patients, but they are a constrained resource in most inpatient settings.

The Activity Measure-Post Acute Care Inpatient Mobility Short Form (AM-PAC IMSF) is a validated tool for measuring physical function.5 The AM-PAC score has been used to predict discharge destination within 48 hours of admission6 and as a guide to allocate inpatient therapy referrals on a medical and a neurosurgical service.7,8 To date, however, no studies have used AM-PAC scores to evaluate overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services. In this study, we aimed to assess the potential overutilization of physical therapy consults on direct care hospital medicine services using validated AM-PAC score cutoffs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We analyzed a retrospective cohort of admissions from September 30, 2018, through September 29, 2019, on all direct care hospital medicine services at the University of Chicago Medical Center (UC), Illinois. These services included general medicine, oncology, transplant (renal, lung, and liver), cardiology, and cirrhotic populations at the medical-surgical and telemetry level of care. All patients were hospitalized for longer than 48 hours. Patients who left against medical advice; died; were discharged to hospice, another hospital, or an inpatient psychiatric facility; or received no physical therapy referral during admission were excluded. For the remaining patients, we obtained age, sex, admission and discharge dates, admission and discharge AM-PAC scores, and discharge disposition.

Mobility Measure

At UC, the inpatient mobility protocol requires nursing staff to assess and document AM-PAC mobility scores for each patient at the time of admission and every nursing shift thereafter. They utilize the original version of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” Basic Mobility score, which includes three questions assessing difficulty with mobility and three questions assessing help needed with mobility activities. It has high interrater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.85.9

Outcomes and Predictors

The primary outcome was “potential overutilization.” Secondary outcomes were discharge disposition and change in mobility. Our predictors included admission AM-PAC score, age, and sex. Based on previous studies that validated an AM-PAC score of 42.9 (raw score, 17) as a cutoff for predicting discharge to home,6 we defined physical therapy consults as “potentially inappropriate” in patients with admission AM-PAC scores >43.63 (raw score, 18) who were discharged to home. Likewise, in the UC mobility protocol, nursing staff independently mobilize patients with AM-PAC scores >18, another rationale to use this cutoff for defining physical therapy consult inappropriateness. “Discharge to home” was defined as going home with no additional needs or services, going home with outpatient physical therapy, or going home with home health physical therapy services, since none of these require inpatient physical therapy assessment for the order to be placed. Discharge to long-term acute care, skilled nursing facility, subacute rehabilitation facility, or acute rehabilitation facility were considered “discharge to post–acute care.” Loss of mobility was calculated as: discharge AM-PAC − admission AM-PAC, termed delta AM-PAC.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize age (mean and SD) and age categorized as <65 years or ≥65 years, sex (male or female), admission AM-PAC score (mean and SD) and categorization (≤43.63 or >43.63), discharge AM-PAC score (mean and SD), and discharge destination (home vs post–acute care). Chi-square analysis was used to test for associations between admission AM-PAC score and delta AM-PAC. Two-sample t-test was used to test for difference in mean delta AM-PAC between admission AM-PAC groups. Multivariable logistic regression was used to test for independent associations between age, sex, and admission AM-PAC score and odds of being discharged to home, controlling for length of stay. P values of <.05 were considered statistically significant for all tests. Analyses were performed using Stata statistical software, release 16 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, 3592 admissions with physical therapy consults occurred on the direct care hospital medicine services (58% of all admissions). Mean age was 66.3 years (SD, 15.4 years), and 48% of patients were female. The mean admission AM-PAC score was 43.9 (SD, 11.1), and the mean discharge AM-PAC score was 46.8 (SD, 10.8). In our sample, 38% of physical therapy consults were for patients with an AM-PAC score >43.63 who were discharged to home and were therefore deemed “potential overutilization.” Of those, 40% were for patients who were 65 years or younger (18% of all physical therapy consults) (Table 1).

A higher proportion of patients with AM-PAC scores >43.63 were discharged to home compared with those with AM-PAC scores ≤43.63 (89% vs 55%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 396.5; P < .001). More patients younger than 65 years were discharged to home compared with those 65 years and older (79% vs 63%; χ2 [1, N = 3099], 113.6; P < .001). Additionally, for all patients younger than 65 years, those with AM-PAC score >43.63 were discharged to home more frequently than those with AM-PAC ≤43.63 (92% vs 66%, χ2 [1, N = 1,354], 134.4; P < .001). For 11% (n = 147) of the high-mobility group, the patient was not discharged home but was sent to post–acute care. Reviewing these patient charts showed the reasons for discharge to post–acute care were predominantly personal or social needs (eg, homelessness, need for 24-hour supervision with no family support, patient request) or medical needs (eg, intravenous antibiotics or new tubes, lines, drains, or medications requiring extra nursing support or management). Only 16% of patients in this group (n = 23) experienced deconditioning necessitating physical therapy consult during hospitalization, per their record.

Compared with patients with admission AM-PAC score >43.63, patients with admission AM-PAC ≤43.63 had significantly different changes in mobility as measured by mean delta AM-PAC score (delta AM-PAC, –0.41 for AM-PAC >43.63 vs +5.69 for AM-PAC ≤43.63; t (3097) = –20.3; P < .001) (Table 1).

In multivariate logistic regression, AM-PAC >43.63 (OR, 5.38; 95% CI, 4.36-2.89; P < .001) and age younger than 65 years (OR, 2.40; 95% CI, 1.99-2.90; P < .001) were associated with increased odds of discharge to home (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that physical therapists may be unnecessarily consulted on direct care hospitalist services as much as 38% of the time based on AM-PAC score. We also demonstrated that patients admitted with high mobility by AM-PAC score are more than five times as likely to be discharged to home. When admitted with high AM-PAC scores, patients had virtually no change in mobility during hospitalization, whereas patients with low AM-PAC scores gained mobility during hospitalization, underscoring the benefit of physical therapy referrals for this group.

Given resource scarcity and cost, achieving optimal physical therapy utilization is an important goal for healthcare systems.10 Appropriate allocation of physical therapy has the potential to improve outcomes from the patient to the payor level. While it may be necessary to consult physical therapy for reasons other than mobility later in the hospitalization, identifying patients who will benefit from skilled physical therapy at the time of admission can help prevent disability and institutionalization and shorten length of stay.5,6 Likewise, decreasing physical therapy referrals for low-risk patients can increase the amount of time spent rehabilitating at-risk patients.

There are limitations of our study worth considering. First, our analyses did not consider whether physical therapy contributed to patients’ ability to return home after discharge. However, in our hospital, patients with AM-PAC >43.63 who cannot safely ambulate independently do progressive mobility with nursing staff. Our physical therapy leadership has also observed that the vast majority of highly mobile patients who are referred for physical therapy ultimately receive no treatment. Second, we did not consider discharge diagnosis, but our patient populations present with a wide variety of conditions, and it is impossible to predict their discharge diagnosis. By not including discharge diagnosis, we assess how AM-PAC performs on admission regardless of the medical condition for which someone is treated. Our hospital treats a high proportion of African American and a low proportion of White, Hispanic, and Asian American patients, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” score has been shown to have high interrater reliability among physical therapists, our AM-PAC scores are assessed and documented by our nursing staff, which might decrease accuracy. However, one single-center study noted an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.96 between nurses and physical therapists for the AM-PAC “6-Clicks.”11Despite these limitations, this study underscores the need to be more judicious in the decision to refer a patient for inpatient physical therapy, especially at the time of admission, and demonstrates the utility of using standardized mobility assessment to help in that decision-making process.

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

1. Fazio S, Stocking J, Kuhn B, et al. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl Nurs Res. 2020;51:151189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2019.151189

2. Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660-1665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02393.x

3. Brown C.J, Friedkin RJ, Inouye SK. Prevalence and outcomes of low mobility in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1263-1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52354.x

4. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:55-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13193

5. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94(3):379-391. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130199

6. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek SD, Frost FS, Jette AM. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94(9):1252-1261. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130359

7. Probasco JC, Lavezza A, Cassell A, et al. Choosing wisely together: physical and occupational therapy consultation for acute neurology inpatients. Neurohospitalist. 2018;8(2):53-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941874417729981

8. Young DL, Colantuoni E, Friedman LA, et al. Prediction of disposition within 48 hours of hospital admission using patient mobility scores. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9);540-543. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3332

9. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, Passek S, Frost FS, Jette AM. Interrater reliability of AM-PAC “6-Clicks” basic mobility and daily activity short forms. Phys Ther. 2015;95(5):758-766. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140174

10. Juneau A, Bolduc A, Nguyen P, et al. Feasibility of implementing an exercise program in a geriatric assessment unit: the SPRINT program. Can Geriatr J. 2018;21(3):284-289. https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.21.311

11. Hoyer EH, Young DL, Klein LM, et al. Toward a common language for measuring patient mobility in the hospital: reliability and construct validity of interprofessional mobility measures. Phys Ther. 2018;98(2):133-142. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzx110

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine