User login

Clustered Vesicles on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

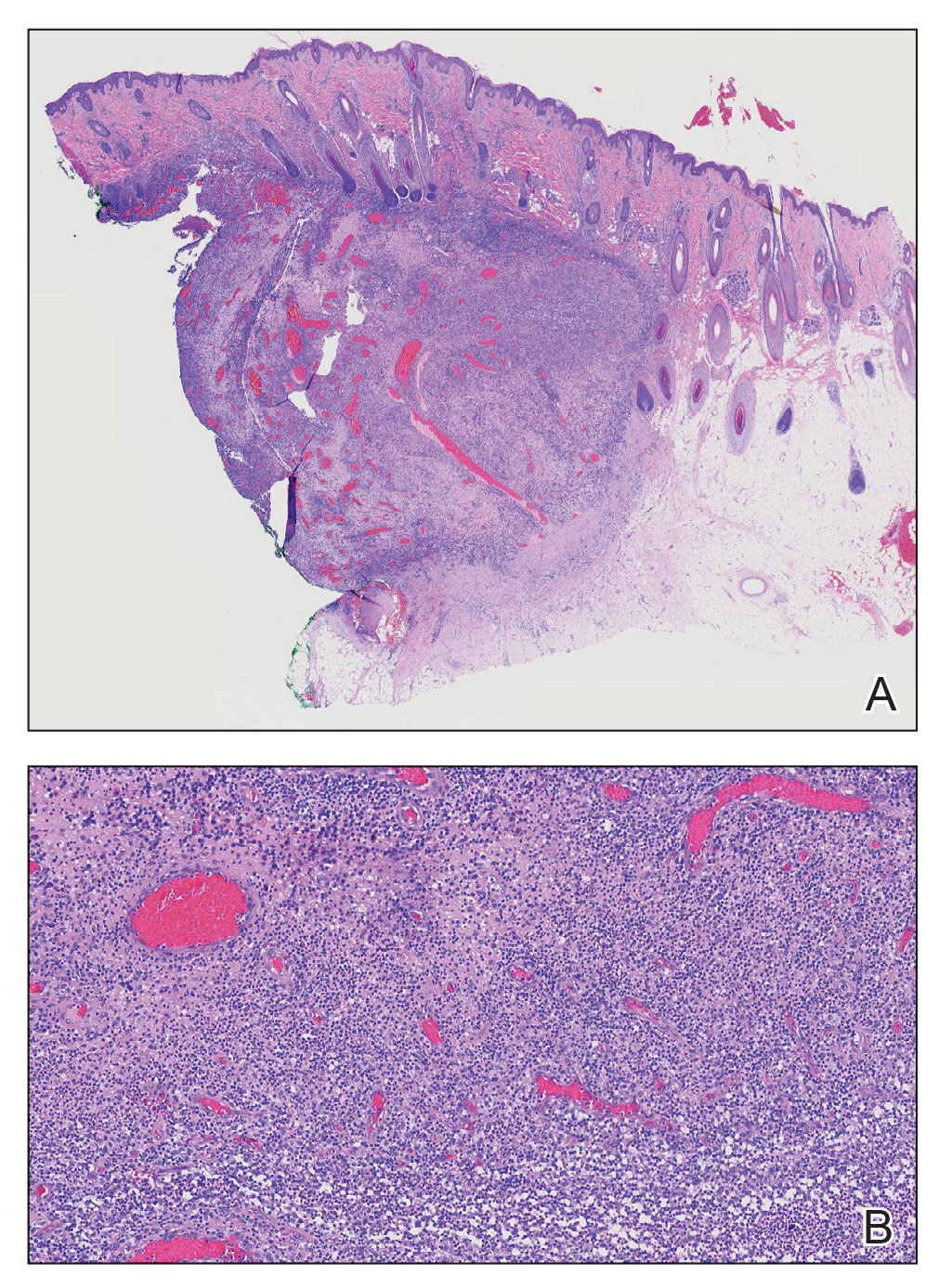

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

A 6-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the right side of the neck that was noted at birth as a small raised lesion but slowly increased over time in size and number of lesions. She reported pruritus and irritation, particularly when rubbed or scratched. There was no family history of similar skin abnormalities. Her medical history was notable for a left-sided cholesteatoma on tympanomastoidectomy. Physical examination revealed clustered vesicles on the right side of the neck with underlying erythema. The vesicles contained mostly clear fluid with a few focal areas of hemorrhagic fluid. Ultrasonography was unremarkable, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed superficial T2 hyperintense nonenhancing cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions overlying the right lateral neck with minimal extension into the superficial right supraclavicular soft tissues.

Scalp Nodule Associated With Hair Loss

The Diagnosis: Alopecic and Aseptic Nodule of the Scalp

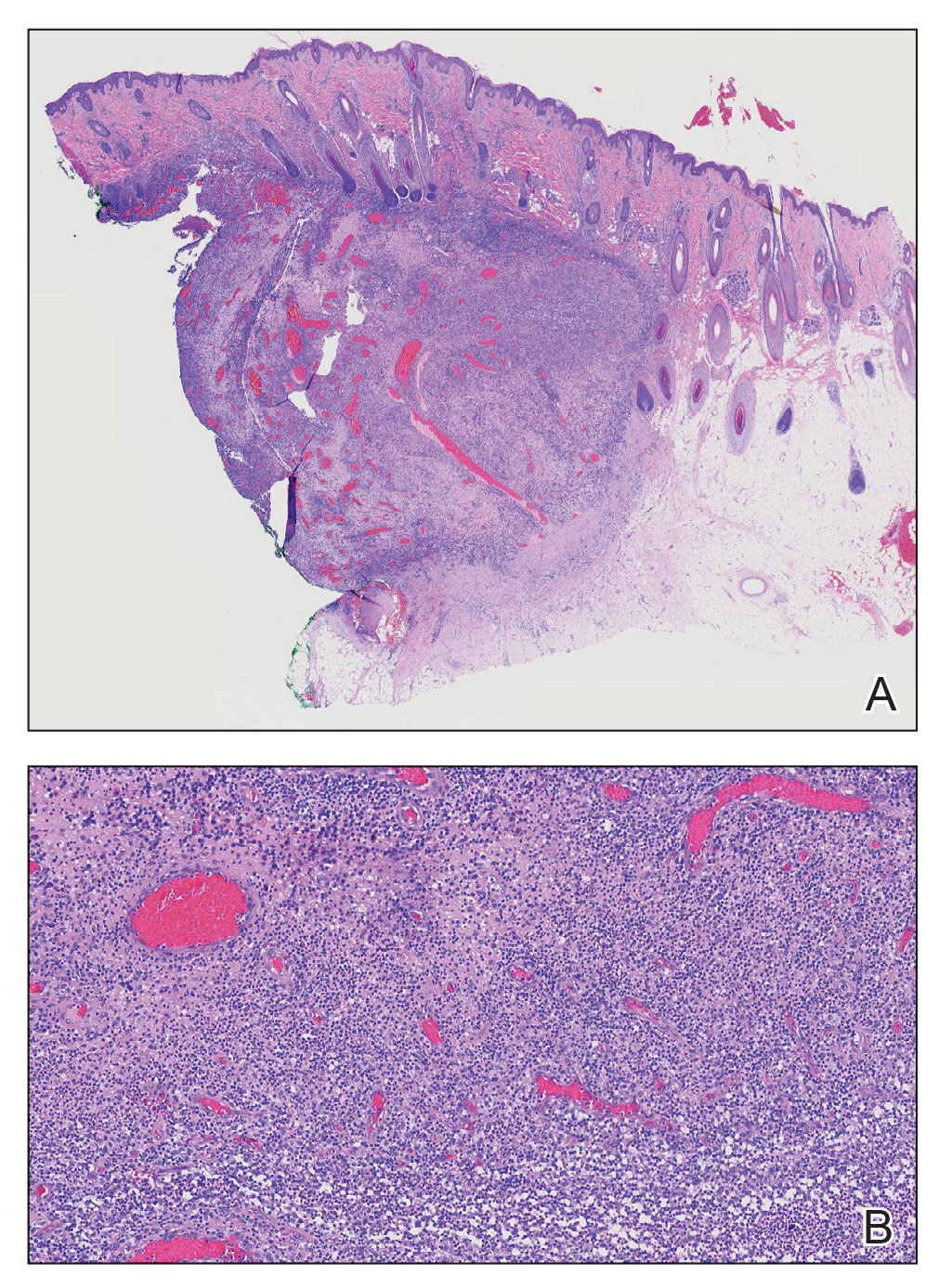

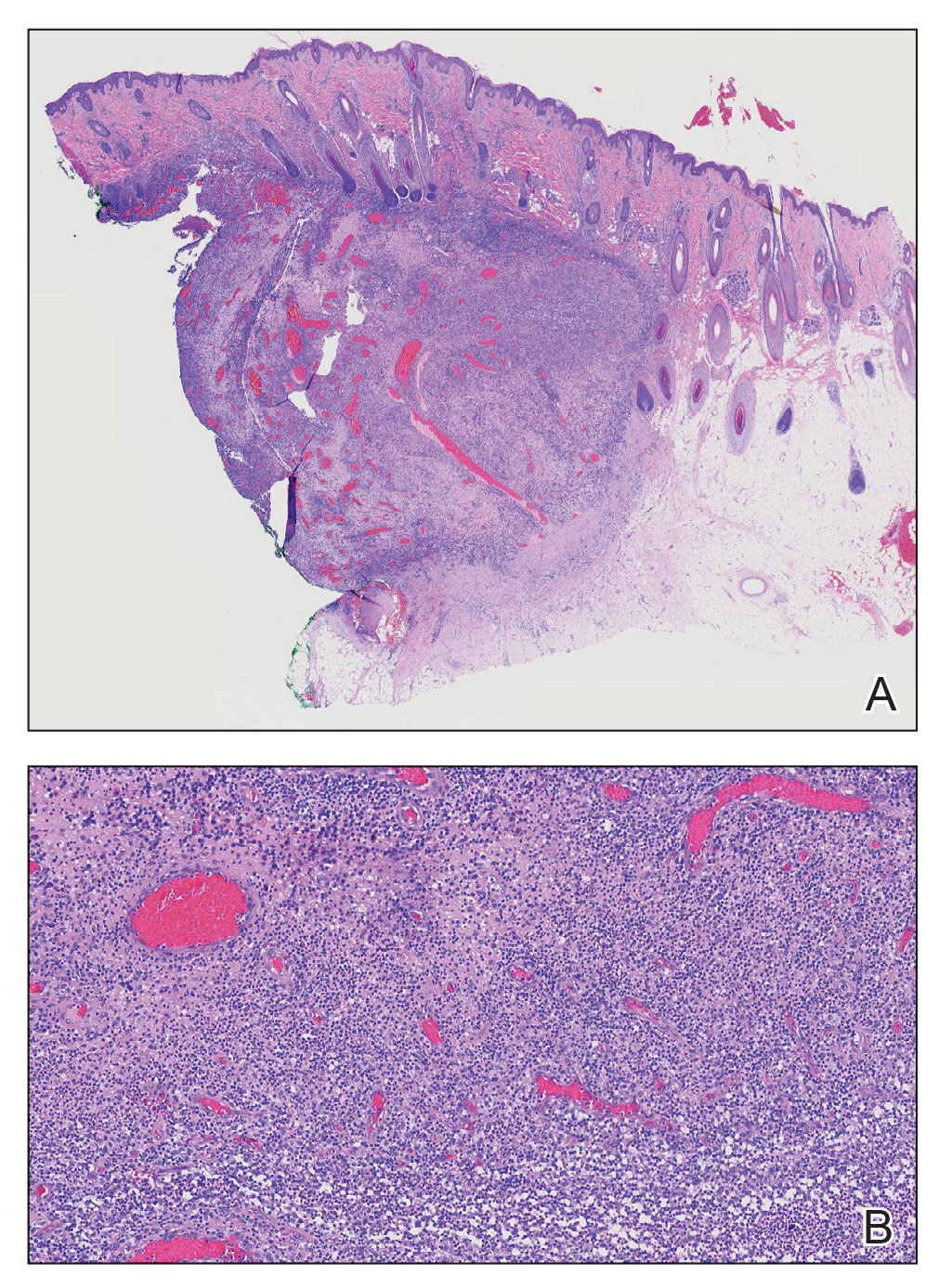

Alopecic and aseptic nodule of the scalp (AANS) is an underdiagnosed condition presenting with one or few inflammatory nodules on the scalp with overlying nonscarring alopecia. The nodules can be soft, fluctuant, or firm and are characterized by negative fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures.1 Trichoscopic features such as black or yellow dots, fine vellus hairs, and broken hairs have been reported.1-3 Dilated follicular openings may be seen and are termed the Eastern pancake sign, as they resemble the bubble cavities formed during the cooking of atayef.2 The histologic features of AANS often are nonspecific but show a nodular or pseudocystic, lymphohistiocytic to acute inflammatory component centered in the dermis.1 Granulomatous inflammation or isolated giant cells have been reported within the deep dermis.1,4 In our patient, histopathology revealed admixed acute and granulomatous inflammation within the deep dermis (Figure). Treatment of AANS includes oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids, or excision.1

Although the etiology of AANS currently is unclear, a process of follicular plugging or a deep folliculitis sparing the bulge stem cells has been theorized. Young males are disproportionately affected.1 It is uncertain how much overlap there is, if any, between AANS and pseudocyst of the scalp, the latter of which primarily is reported in the Japanese literature and demonstrates alopecic nodules between the forehead and vertex of the scalp with pseudocystic architecture and granulomatous infiltration on histopathology.4-7

There are several clinical and histologic differences between AANS and other diagnoses in the differential. Dermoid cysts tend to present at birth, with 70% of cases presenting before the age of 6 years, and without overlying skin changes.8 They represent a benign entrapment of ectoderm along embryonic closure lines during development.9 Histologic examination typically will show a squamous-lined cyst within the dermis with associated adnexal structures.10 Cylindromas are benign neoplasms of eccrine sweat glands named after the histologic presentation of cylinder-shaped basaloid cell populations when cross-sectioned.11,12 When cylindromas coalesce on the scalp, they form a distinctive morphology sometimes loosely resembling a turban, giving them the previously more common name turban tumors.11,13 Cylindromas appear as slow-growing protuberant tumors that are erythematous or flesh colored. Cylindromas are 9 times more common in females.13 Pilar cysts have a stratified squamous epithelium lining with a palisaded outer layer and are derived from the outer root sheath of hair follicles.14 Clinically, pilar cysts are smooth mobile cysts that favor skin with a dense concentration of hair follicles.14,15 On palpation, pilar cysts are firm due to their keratinous contents and typically are nontender unless inflamed.15 Lipomas are benign mesenchymal tumors with mature adipocytes that often appear as subcutaneous nodules without overlying skin changes, though they can involve deep fascia. On palpation, lipomas generally are soft, mobile, and nontender.16

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Colato C, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp: a new case with a systematic review of the literature [published online May 1, 2021]. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:E04153. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4153

- Lázaro-Simó AI, Sancho MI, Quintana-Codina M, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp with trichoscopic and ultrasonographic findings. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:515-518.

- Garrido-Colmenero C, Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros Fernández J, et al. Trichoscopy and ultrasonography features of aseptic and alopecic nodules of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:507-509. doi:10.1111/jdv.12903

- Seol JE, Park IH, Kim DH, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp/pseudocyst of the scalp: clinicopathological and therapeutic analyses in 11 Korean patients. Dermatology. 2016;232:165-170.

- Lee SS, Kim SY, Im M, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S267-S269.

- Eisenberg EL. Alopecia-associated pseudocyst of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E114-E116.

- Tsuruta D, Hayashi A, Kobayashi H, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Dermatology. 2005;210:333-335.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Julapalli MR, Cohen BA, Hollier LH, et al. Congenital, ill-defined, yellowish plaque: the nasal dermoid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:556-559.

- Reissis D, Pfaff MJ, Patel A, et al. Craniofacial dermoid cysts: histological analysis and inter-site comparison. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:349-357.

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Heard SC, McLaren B, et al. Cylindroma (dermal analog tumor) of the breast: a comparison with cylindroma of the skin and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:866-873.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Cylindroma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.107532

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 16. Kolb L, Yarrarapu SNS, Ameer MA, et al. Lipoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

The Diagnosis: Alopecic and Aseptic Nodule of the Scalp

Alopecic and aseptic nodule of the scalp (AANS) is an underdiagnosed condition presenting with one or few inflammatory nodules on the scalp with overlying nonscarring alopecia. The nodules can be soft, fluctuant, or firm and are characterized by negative fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures.1 Trichoscopic features such as black or yellow dots, fine vellus hairs, and broken hairs have been reported.1-3 Dilated follicular openings may be seen and are termed the Eastern pancake sign, as they resemble the bubble cavities formed during the cooking of atayef.2 The histologic features of AANS often are nonspecific but show a nodular or pseudocystic, lymphohistiocytic to acute inflammatory component centered in the dermis.1 Granulomatous inflammation or isolated giant cells have been reported within the deep dermis.1,4 In our patient, histopathology revealed admixed acute and granulomatous inflammation within the deep dermis (Figure). Treatment of AANS includes oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids, or excision.1

Although the etiology of AANS currently is unclear, a process of follicular plugging or a deep folliculitis sparing the bulge stem cells has been theorized. Young males are disproportionately affected.1 It is uncertain how much overlap there is, if any, between AANS and pseudocyst of the scalp, the latter of which primarily is reported in the Japanese literature and demonstrates alopecic nodules between the forehead and vertex of the scalp with pseudocystic architecture and granulomatous infiltration on histopathology.4-7

There are several clinical and histologic differences between AANS and other diagnoses in the differential. Dermoid cysts tend to present at birth, with 70% of cases presenting before the age of 6 years, and without overlying skin changes.8 They represent a benign entrapment of ectoderm along embryonic closure lines during development.9 Histologic examination typically will show a squamous-lined cyst within the dermis with associated adnexal structures.10 Cylindromas are benign neoplasms of eccrine sweat glands named after the histologic presentation of cylinder-shaped basaloid cell populations when cross-sectioned.11,12 When cylindromas coalesce on the scalp, they form a distinctive morphology sometimes loosely resembling a turban, giving them the previously more common name turban tumors.11,13 Cylindromas appear as slow-growing protuberant tumors that are erythematous or flesh colored. Cylindromas are 9 times more common in females.13 Pilar cysts have a stratified squamous epithelium lining with a palisaded outer layer and are derived from the outer root sheath of hair follicles.14 Clinically, pilar cysts are smooth mobile cysts that favor skin with a dense concentration of hair follicles.14,15 On palpation, pilar cysts are firm due to their keratinous contents and typically are nontender unless inflamed.15 Lipomas are benign mesenchymal tumors with mature adipocytes that often appear as subcutaneous nodules without overlying skin changes, though they can involve deep fascia. On palpation, lipomas generally are soft, mobile, and nontender.16

The Diagnosis: Alopecic and Aseptic Nodule of the Scalp

Alopecic and aseptic nodule of the scalp (AANS) is an underdiagnosed condition presenting with one or few inflammatory nodules on the scalp with overlying nonscarring alopecia. The nodules can be soft, fluctuant, or firm and are characterized by negative fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures.1 Trichoscopic features such as black or yellow dots, fine vellus hairs, and broken hairs have been reported.1-3 Dilated follicular openings may be seen and are termed the Eastern pancake sign, as they resemble the bubble cavities formed during the cooking of atayef.2 The histologic features of AANS often are nonspecific but show a nodular or pseudocystic, lymphohistiocytic to acute inflammatory component centered in the dermis.1 Granulomatous inflammation or isolated giant cells have been reported within the deep dermis.1,4 In our patient, histopathology revealed admixed acute and granulomatous inflammation within the deep dermis (Figure). Treatment of AANS includes oral antibiotics such as doxycycline, intralesional corticosteroids, or excision.1

Although the etiology of AANS currently is unclear, a process of follicular plugging or a deep folliculitis sparing the bulge stem cells has been theorized. Young males are disproportionately affected.1 It is uncertain how much overlap there is, if any, between AANS and pseudocyst of the scalp, the latter of which primarily is reported in the Japanese literature and demonstrates alopecic nodules between the forehead and vertex of the scalp with pseudocystic architecture and granulomatous infiltration on histopathology.4-7

There are several clinical and histologic differences between AANS and other diagnoses in the differential. Dermoid cysts tend to present at birth, with 70% of cases presenting before the age of 6 years, and without overlying skin changes.8 They represent a benign entrapment of ectoderm along embryonic closure lines during development.9 Histologic examination typically will show a squamous-lined cyst within the dermis with associated adnexal structures.10 Cylindromas are benign neoplasms of eccrine sweat glands named after the histologic presentation of cylinder-shaped basaloid cell populations when cross-sectioned.11,12 When cylindromas coalesce on the scalp, they form a distinctive morphology sometimes loosely resembling a turban, giving them the previously more common name turban tumors.11,13 Cylindromas appear as slow-growing protuberant tumors that are erythematous or flesh colored. Cylindromas are 9 times more common in females.13 Pilar cysts have a stratified squamous epithelium lining with a palisaded outer layer and are derived from the outer root sheath of hair follicles.14 Clinically, pilar cysts are smooth mobile cysts that favor skin with a dense concentration of hair follicles.14,15 On palpation, pilar cysts are firm due to their keratinous contents and typically are nontender unless inflamed.15 Lipomas are benign mesenchymal tumors with mature adipocytes that often appear as subcutaneous nodules without overlying skin changes, though they can involve deep fascia. On palpation, lipomas generally are soft, mobile, and nontender.16

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Colato C, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp: a new case with a systematic review of the literature [published online May 1, 2021]. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:E04153. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4153

- Lázaro-Simó AI, Sancho MI, Quintana-Codina M, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp with trichoscopic and ultrasonographic findings. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:515-518.

- Garrido-Colmenero C, Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros Fernández J, et al. Trichoscopy and ultrasonography features of aseptic and alopecic nodules of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:507-509. doi:10.1111/jdv.12903

- Seol JE, Park IH, Kim DH, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp/pseudocyst of the scalp: clinicopathological and therapeutic analyses in 11 Korean patients. Dermatology. 2016;232:165-170.

- Lee SS, Kim SY, Im M, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S267-S269.

- Eisenberg EL. Alopecia-associated pseudocyst of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E114-E116.

- Tsuruta D, Hayashi A, Kobayashi H, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Dermatology. 2005;210:333-335.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Julapalli MR, Cohen BA, Hollier LH, et al. Congenital, ill-defined, yellowish plaque: the nasal dermoid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:556-559.

- Reissis D, Pfaff MJ, Patel A, et al. Craniofacial dermoid cysts: histological analysis and inter-site comparison. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:349-357.

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Heard SC, McLaren B, et al. Cylindroma (dermal analog tumor) of the breast: a comparison with cylindroma of the skin and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:866-873.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Cylindroma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.107532

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 16. Kolb L, Yarrarapu SNS, Ameer MA, et al. Lipoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Colato C, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp: a new case with a systematic review of the literature [published online May 1, 2021]. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9:E04153. doi:10.1002/ccr3.4153

- Lázaro-Simó AI, Sancho MI, Quintana-Codina M, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp with trichoscopic and ultrasonographic findings. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:515-518.

- Garrido-Colmenero C, Arias-Santiago S, Aneiros Fernández J, et al. Trichoscopy and ultrasonography features of aseptic and alopecic nodules of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:507-509. doi:10.1111/jdv.12903

- Seol JE, Park IH, Kim DH, et al. Alopecic and aseptic nodules of the scalp/pseudocyst of the scalp: clinicopathological and therapeutic analyses in 11 Korean patients. Dermatology. 2016;232:165-170.

- Lee SS, Kim SY, Im M, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 2):S267-S269.

- Eisenberg EL. Alopecia-associated pseudocyst of the scalp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:E114-E116.

- Tsuruta D, Hayashi A, Kobayashi H, et al. Pseudocyst of the scalp. Dermatology. 2005;210:333-335.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Julapalli MR, Cohen BA, Hollier LH, et al. Congenital, ill-defined, yellowish plaque: the nasal dermoid. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:556-559.

- Reissis D, Pfaff MJ, Patel A, et al. Craniofacial dermoid cysts: histological analysis and inter-site comparison. Yale J Biol Med. 2014;87:349-357.

- Chauhan DS, Guruprasad Y. Dermal cylindroma of the scalp. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2012;3:59-61.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Heard SC, McLaren B, et al. Cylindroma (dermal analog tumor) of the breast: a comparison with cylindroma of the skin and adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:866-873.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Cylindroma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128. doi:10.4103/1947-2714.107532

- Al Aboud DM, Yarrarapu SNS, Patel BC. Pilar cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. 16. Kolb L, Yarrarapu SNS, Ameer MA, et al. Lipoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

A 9-year-old boy presented with a soft subcutaneous nodule with overlying alopecia on the right parietal scalp of 5 months’ duration that had grown in size, became increasingly alopecic, and was complicated by intermittent pain. An excisional biopsy of the nodule revealed deep dermal mixed inflammation with scattered granulomas. No foreign material, definitive cystic spaces, or cyst wall lining was identified. Special stains including periodic acid– Schiff, Fite acid-fast, and Twort Gram were negative for infectious organisms. His postoperative course was uneventful, and no recurrence of the nodule was reported.

Hyperpigmented Papules on the Tongue of a Child

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Fungiform Papillae of the Tongue

Our patient’s hyperpigmentation was confined to the fungiform papillae, leading to a diagnosis of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue (PFPT). A biopsy was not performed, and reassurance was provided regarding the benign nature of this finding, which did not require treatment.

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a benign, nonprogressive, asymptomatic pigmentary condition that is most common among patients with skin of color and typically develops within the second or third decade of life.1,2 The pathogenesis is unclear, but activation of subepithelial melanophages without evidence of inflammation has been implicated.2 Although no standard treatment exists, cosmetic improvement with the use of the Q-switched ruby laser has been reported.3,4 Clinically, PFPT presents as asymptomatic hyperpigmentation confined to the fungiform papillae along the anterior and lateral portions of the tongue.1,2

Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue typically is an isolated finding but rarely can be associated with hyperpigmentation of the nails (as in our patient) or gingiva.2 Three different clinical patterns of presentation have been described: (1) a single well-circumscribed collection of pigmented fungiform papillae, (2) few scattered pigmented fungiform papillae admixed with many nonpigmented fungiform papillae, or (3) pigmentation of all fungiform papillae on the dorsal aspect of the tongue.2,5,6 Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue is a clinical diagnosis based on visual recognition. Dermoscopic examination revealing a cobblestonelike or rose petal–like pattern may be helpful in diagnosing PFPT.2,5-7 Although not typically recommended in the evaluation of PFPT, a biopsy will reveal papillary structures with hyperpigmentation of basilar keratinocytes as well as melanophages in the lamina propria.8 The latter finding suggests a transient inflammatory process despite the hallmark absence of inflammation.5 Melanocytic neoplasia and exogenous granules of pigment typically are not seen.8

Other conditions that may present with dark-colored macules or papules on the tongue should be considered in the evaluation of a patient with these clinical findings. Black hairy tongue (BHT), or lingua villosa nigra, is a benign finding due to filiform papillae hypertrophy on the dorsum of the tongue.9 Food particle debris caught in BHT can lead to porphyrin production by chromogenic bacteria and fungi. These porphyrins result in discoloration ranging from brown-black to yellow and green occurring anteriorly to the circumvallate papillae while usually sparing the tip and lateral sides of the tongue. Dermoscopy can show thin discolored fibers with a hairy appearance. Although normal filiform papillae are less than 1-mm long, 3-mm long papillae are considered diagnostic of BHT.9 Treatment includes effective oral hygiene and desquamation measures, which can lead to complete resolution.10

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare genodermatosis that is characterized by focal hyperpigmentation and multiple gastrointestinal mucosal hamartomatous polyps. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome should be suspected in a patient with discrete, 1- to 5-mm, brown to black macules on the perioral or periocular skin, tongue, genitals, palms, soles, and buccal mucosa with a history of abdominal symptoms.11,12

Addison disease, or primary adrenal insufficiency, may present with brown hyperpigmentation on chronically sun-exposed areas; regions of friction or pressure; surrounding scar tissue; and mucosal surfaces such as the tongue, inner surface of the lip, and buccal and gingival mucosa.13 Addison disease is differentiated from PFPT by a more generalized hyperpigmentation due to increased melanin production as well as the presence of systemic symptoms related to hypocortisolism. The pigmentation seen on the buccal mucosa in Addison disease is patchy and diffuse, and histology reveals basal melanin hyperpigmentation with superficial dermal melanophages.13

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disorder featuring telangiectasia and generally appears in the third decade of life.14 Telangiectases classically are 1 to 3 mm in diameter with or without slight elevation. Dermoscopic findings include small red clots, lacunae, and serpentine or linear vessels arranged in a radial conformation surrounding a homogenous pink center.15 These telangiectases typically occur on the skin or mucosa, particularly the face, lips, tongue, nail beds, and nasal mucosa; however, any organ can be affected with arteriovenous malformations. Recurrent epistaxis occurs in more than half of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia.14 Histopathology reveals dilated vessels and lacunae near the dermoepidermal junction displacing the epidermis and papillary dermis.15 It is distinguished from PFPT by the vascular nature of the lesions and by the presence of other characteristic symptoms such as recurrent epistaxis and visceral arteriovenous malformations.

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

- Romiti R, Molina De Medeiros L. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:398-399. doi:10.1111/j .1525-1470.2010.01183.x

- Chessa MA, Patrizi A, Sechi A, et al. Pigmented fungiform lingual papillae: dermoscopic and clinical features. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:935-939. doi:10.1111/jdv.14809

- Rice SM, Lal K. Successful treatment of pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue with Q-switched ruby laser. Dermatol Surg. 2022;48:368-369. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003371

- Mizawa M, Makino T, Furukawa F, et al. Efficacy of Q-switched ruby laser treatment for pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2022;49:E133-E134. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16270

- Holzwanger JM, Rudolph RI, Heaton CL. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a common variant of oral pigmentation. Int J Dermatol. 1974;13:403-408. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1974. tb05073.x

- Mukamal LV, Ormiga P, Ramos-E-Silva M. Dermoscopy of the pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue. J Dermatol. 2012;39:397-399. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01328.x

- Surboyo MDC, Santosh ABR, Hariyani N, et al. Clinical utility of dermoscopy on diagnosing pigmented papillary fungiform papillae of the tongue: a systematic review. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2021;11:618-623. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2021.09.008

- Chamseddin B, Vandergriff T. Pigmented fungiform papillae of the tongue: a clinical and histologic description [published online September 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. 2019;25:13030/qt8674c519.

- Jayasree P, Kaliyadan F, Ashique KT. Black hairy tongue. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5314

- Schlager E, St Claire C, Ashack K, et al. Black hairy tongue: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:563-569. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0268-y

- Sandru F, Petca A, Dumitrascu MC, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: skin manifestations and endocrine anomalies (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:1387. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10823

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189.e1-210. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.10.037

- Lee K, Lian C, Vaidya A, et al. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:993-995. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.08.013

- Haitjema T, Westermann CJ, Overtoom TT, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu disease): new insights in pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:714-719.

- Tokoro S, Namiki T, Ugajin T, et al. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber’s disease): detailed assessment of skin lesions by dermoscopy and ultrasound. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:E224-E226. doi:10.1111/ijd.14578

A 9-year-old Black boy presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of dark spots on the tongue. The family first noted these spots 5 months prior and reported that they remained stable during that time. The patient’s medical history was notable for autism spectrum disorder and multiple food allergies. His family history was negative for similar oral pigmentation or other pigmentary anomalies. A review of systems was positive only for selective eating and rare nosebleeds. Physical examination revealed numerous dark brown, pinpoint papules across the dorsal aspect of the tongue. No hyperpigmentation of the buccal mucosae, lips, palms, or soles was identified. Several light brown streaks were present on the fingernails and toenails, consistent with longitudinal melanonychia. A prior complete blood cell count was within reference range.