User login

Petechial Rash on the Thighs in an Immunosuppressed Patient

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Strongyloidiasis

Strongyloidiasis is a parasitic infection caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. In the United States it is most prevalent in the Appalachian region. During the filariform larval stage of the parasite's life cycle, larvae from contaminated soil infect the human skin and spread to the intestinal epithelium,1 then the larvae mature into adult female worms that can produce eggs asexually. Rhabditiform larvae hatch from the eggs and are either excreted in the stool or develop into infectious filariform larvae. The latter can cause autoinfection of the intestinal mucosa or nearby skin; in addition, if the larvae enter the bloodstream, they can spread throughout the body and lead to disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.2 This often fatal progression most commonly occurs in immunosuppressed individuals.3 The mortality rate has been reported to be up to 87%.2,4

Fever, abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are clinically common in disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.5 Patients also may exhibit dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis.2 Cutaneous manifestations are rare and typically include pruritus and petechiae.6 Eosinophilia may be present but is not a reliable indicator.1

Our patient displayed several risk factors and an early clinical presentation for disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, which evolved over the course of hospitalization. Clues to the diagnosis included an immunosuppressed state; erythematous pruritic macules at presentation that later developed into reticulated petechial patches; and fever, general abdominal symptoms, and dyspnea. However, the patient's overall physical examination findings were subtle and nonspecific. Additionally, the patient did not display the classic larva currens for strongyloidiasis or the pathognomonic periumbilical thumbprint purpura of disseminated infection,6,7 which may indicate that the latter is a later-stage finding. Although graft-vs-host disease initially was suspected, a third skin biopsy revealed basophilic Strongyloides larvae, extravasated erythrocytes, and mild perivascular inflammation (Figure).

Subsequent gastric aspirates and stool cultures revealed S stercoralis. A bronchoalveolar lavage specimen and serum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for Strongyloides antibody were negative. The patient was treated with an extended 16-day course of ivermectin 12 mg daily until gastric aspirates and stool cultures were negative for the parasite. The rash receded by the end of the patient's 32-day hospital stay.

Because of the high mortality rate of untreated disseminated strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome, early diagnosis and initiation of anthelmintic treatment is vital in improving patient outcomes. As such, the diagnosis of disseminated strongyloidiasis should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with multisystemic symptoms and/or petechiae. The differential diagnosis includes graft-vs-host disease, drug-induced urticaria, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and other opportunistic parasites.6,8,9

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

- Concha R, Harrington W Jr, Rogers AI. Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management, and determinants of outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:203-211.

- Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8.

- Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-217.

- Chan FLY, Kennedy B, Nelson R. Fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in an immunocompetent adult with review of the literature. Intern Med J. 2018;48:872-875.

- Scowden EB, Schaffner W, Stone WJ. Overwhelming strongyloidiasis: an unappreciated opportunistic infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1978;57:527-544.

- von Kuster LC, Genta RM. Cutaneous manifestations of strongyloidiasis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1826-1830.

- Weiser JA, Scully BE, Bulman WA, et al. Periumbilical parasitic thumbprint purpura: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome acquired from a cadaveric renal transplant. Transpl Infect Dis. 2011;13:58-62.

- Berenson CS, Dobuler KJ, Bia FJ. Fever, petechiae, and pulmonary infiltrates in an immunocompromised Peruvian man. Yale J Biol Med. 1987;60:437-445.

- Ly MN, Bethel SL, Usmani AS, et al. Cutaneous Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(2 suppl case reports):S157-S160.

A 48-year-old woman from rural Virginia presented with centrifugally spreading, pruritic, blanchable macules over the lower abdomen and upper thighs noted 4 months after a pancreas transplant. After 3 weeks, the macules coalesced into reticulated nonblanching petechial patches. Fever, dyspnea, increasing xerosis, abdominal pain, and constipation were present. The patient had a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus requiring a pancreas transplant. Initial skin biopsy and fluorescence in situ hybridization to test for immune reaction to the XY-donor pancreas were negative. Mild transient eosinophilia was present at admission.

Painful Mouth Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

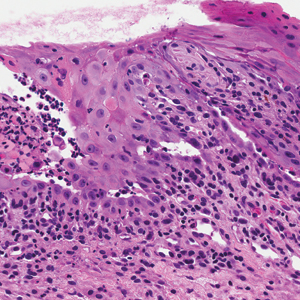

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

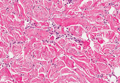

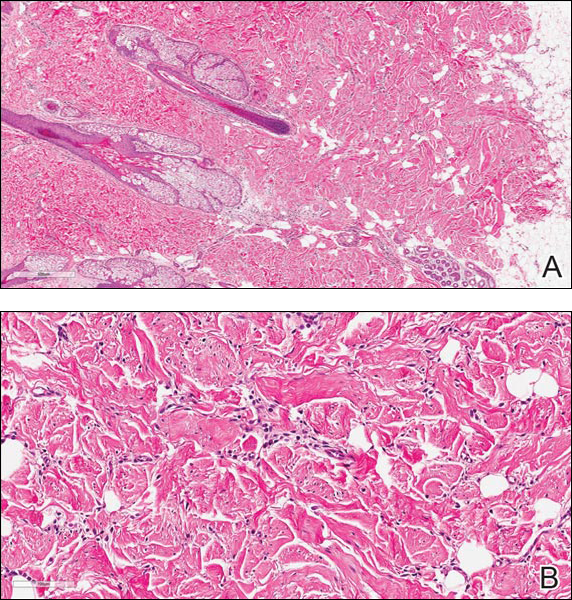

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

The Diagnosis: Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

A workup for infectious organisms and vasculitis was negative. The patient reported unintentional weight loss despite taking oral steroids prescribed by her pulmonologist for severe obstructive lung disease that appeared to develop around the same time as the mouth ulcers.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed an 8.1-cm pelvic mass that a subsequent biopsy revealed to be a follicular dendritic cell sarcoma. Biopsies of the mouth ulcers showed a mildly hyperplastic mucosa with acantholysis and interface change with dyskeratosis. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution (Figure 1). The pathologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP). Serologic testing via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, immunoblotting, and indirect immunofluorescence were not performed. The patient died within a few months after the initial presentation from bronchiolitis obliterans, a potentially fatal complication of PNP.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is an autoimmune blistering disease associated with neoplasia, particularly lymphoproliferative disorders and thymoma.1 Oral mucosal erosions and crusting along the lips commonly is seen along with cutaneous involvement. The main histologic features are interface changes with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate and variable acantholysis.2

Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin classically shows IgG and complement C3 in an intercellular distribution, usually in a granular or linear distribution along the basement membrane. This same pattern of direct immunofluorescence is seen in pemphigus erythematosus; however, pemphigus erythematosus is clinically distinct from PNP, lacking mucosal involvement and affecting the face and/or seborrheic areas with an appearance more similar to seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus, depending on the patient.3 Indirect immunofluorescence with rat bladder epithelium typically is positive in PNP and can be a helpful feature in distinguishing PNP from other autoimmune blistering diseases (eg, pemphigus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus).2

Immunoblotting assays via serology often detect numerous antigens in patients with PNP, including but not limited to plectin, desmoplakin, bullous pemphigoid antigens, envoplakin, desmoplakin II, and desmogleins 1 and 3.4 Some of these autoantibodies have been identified in tumors associated with paraneoplastic pemphigus, particularly Castleman disease and follicular dendritic cell sarcoma.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can have a similar histologic appearance to PNP with prominent dyskeratosis and characteristically shows satellite cell necrosis consisting of dyskeratosis with surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 2). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a feature of GVHD. Direct immunofluorescence typically is negative; however, nonspecific IgM and complement C3 deposition at the dermoepidermal junction and around the superficial vasculature has been reported in 39% of cases.5 Early chronic GVHD often shows retained lichenoid interface change, but late chronic GVHD has a sclerodermoid morphology that is easily distinguished histologically from PNP. Patients also have a history of either a bone marrow or solid organ transplant.6

Lichen planus also shows interface change with dyskeratosis and a lichenoid infiltrate; however, acantholysis typically is not seen and, there often is prominent hypergranulosis (Figure 3). Mucosal lesions often show more subtle features with decreased hyperkeratosis, more subtle hypergranulosis, and decreased interface change with plasma cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.6 Additionally, direct immunofluorescence is either negative or shows IgM-positive colloid bodies and/or an irregular band of fibrinogen at the dermoepidermal junction. The characteristic intercellular and granular/linear IgG positivity at the dermoepidermal junction of PNP is not seen.

Lupus erythematosus is an interface dermatitis with histologic features that can overlap with PNP, in addition to positive direct immunofluorescence, which has been seen in 50% to 94% of cases and can vary depending on previous steroid treatment and timing of the biopsy in the disease process.7 Unlike PNP, lupus erythematosus has a full-house pattern on direct immunofluorescence with IgG, IgM, IgA, and complement C3 deposition in a granular pattern at the dermoepidermal junction. While PNP also typically shows granular deposition of IgG and complement C3 at the dermoepidermal junction, there also is intercellular positivity without a full-house pattern. While both conditions show interface change, histologic features that distinguish lupus erythematosus from PNP are a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, and increased dermal mucin (Figure 4). Subacute lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus can have similar histologic features, and definitive distinction on biopsy is not always possible; however, subacute lupus erythematosus shows milder follicular plugging and milder to absent basement membrane thickening, and the inflammatory infiltrate typically is sparser than in discoid lupus erythematosus.7 Subacute lupus erythematosus also can show anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen A antibodies, which typically are not seen in discoid lupus eythematosus.8

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is on a spectrum with toxic epidermal necrolysis, with SJS involving less than 10% and toxic epidermal necrolysis involving 30% or more of the body surface area.5 Erythema multiforme also is on the histologic spectrum of SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis; however, erythema multiforme typically is more inflammatory than SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Stevens-Johnson syndrome typically affects older adults and shows both cutaneous and mucosal involvement; however, isolated mucosal involvement can be seen in children.5 Drugs, particularly sulfonamide antibiotics, usually are implicated as causative agents, but infections from Mycoplasma and other pathogens also may be the cause. There is notable clinical (with a combination of mucosal and cutaneous lesions) as well as histologic overlap between SJS and PNP. The density of the lichenoid infiltrate is variable, with dyskeratosis, basal cell hydropic degeneration, and occasional formation of subepidermal clefts (Figure 5). Unlike PNP, acantholysis is not a characteristic feature of SJS, and direct immunofluorescence generally is negative.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Camisa C, Helm TN. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a distinct neoplasia-induced autoimmune disease. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:883-886.

- Joly P, Richard C, Gilbert D, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of clinical, histologic, and immunologic features in the diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:619-626.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Acantholytic disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:151-179.

- Billet ES, Grando AS, Pittelkow MR. Paraneoplastic autoimmune multiorgan syndrome: review of the literature and support for a cytotoxic role in pathogenesis. Autoimmunity. 2006;36:617-630.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Lichenoid and interface dermatitis. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:219-255.

- Billings SD, Cotton J. Inflammatory Dermatopathology: A Pathologist's Survival Guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A. Idiopathic connective tissue disorders. McKee's Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2011:711-757.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

A 41-year-old woman presented with painful ulcers on the oral mucosa of 2 months' duration that were unresponsive to treatment with acyclovir. She had been diagnosed with a pelvic tumor a few weeks prior to the development of the mouth ulcers. Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional mucosa showed positive IgG and complement C3 with an intercellular distribution. A biopsy of an oral lesion was performed.

Thick Scaly Plaques on the Wrists, Knees, and Feet

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

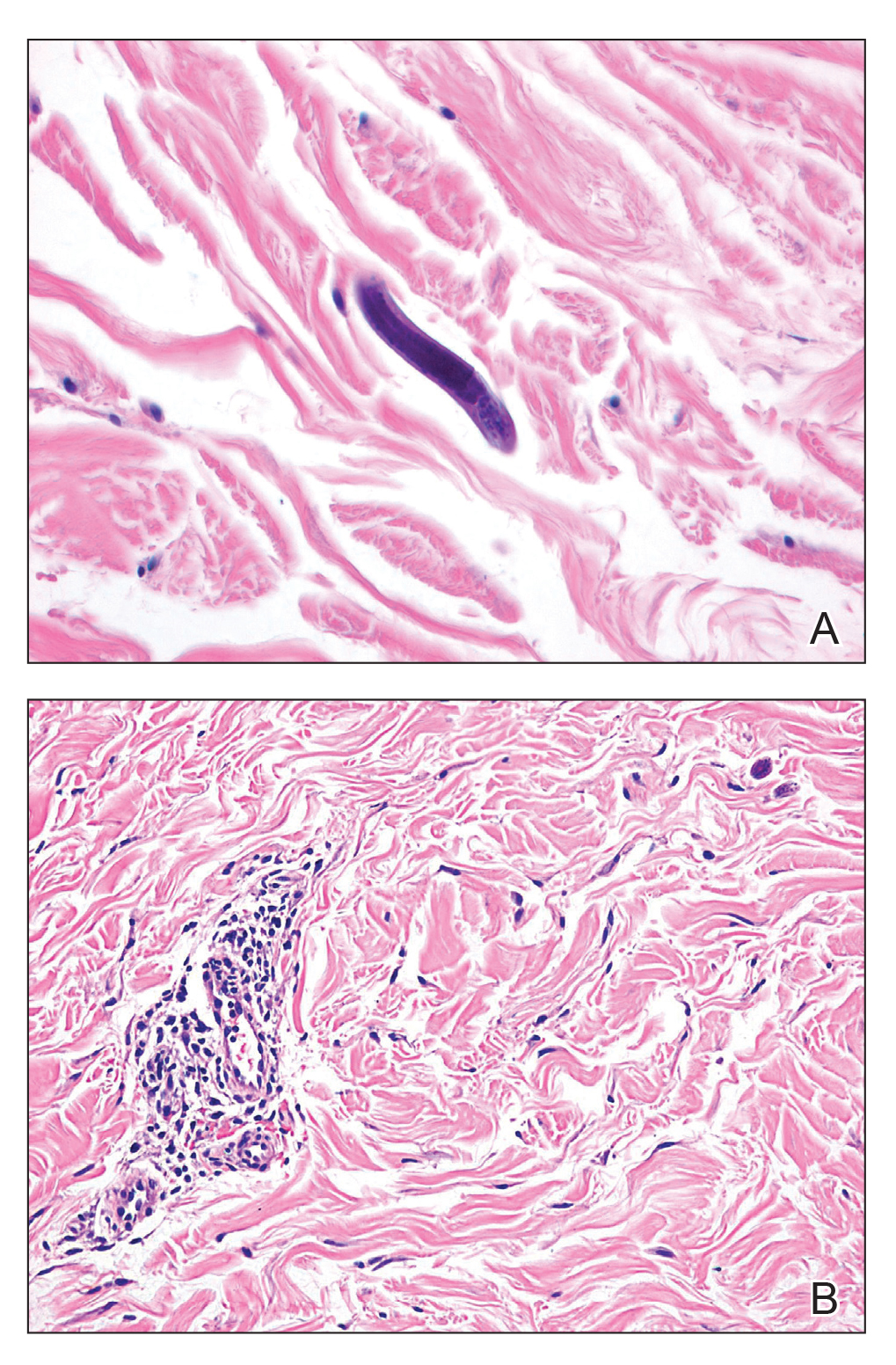

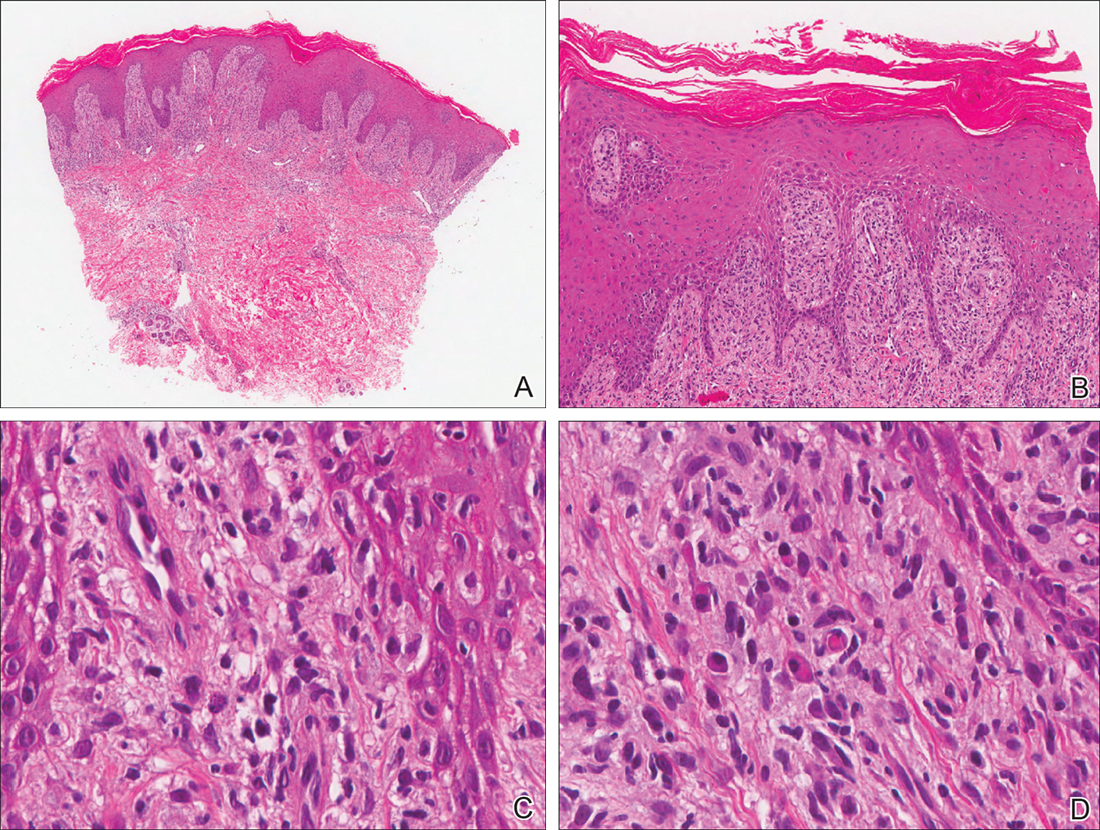

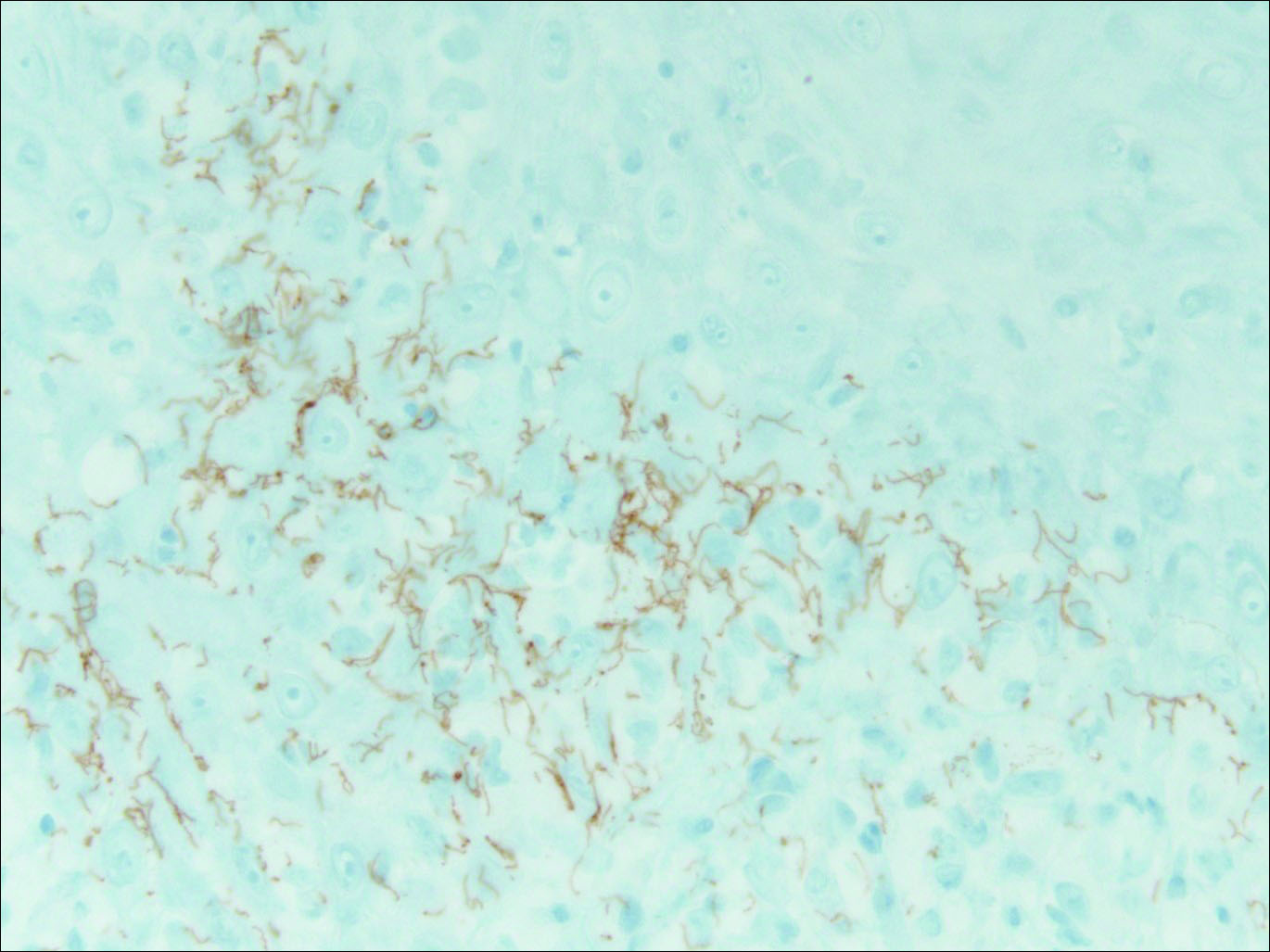

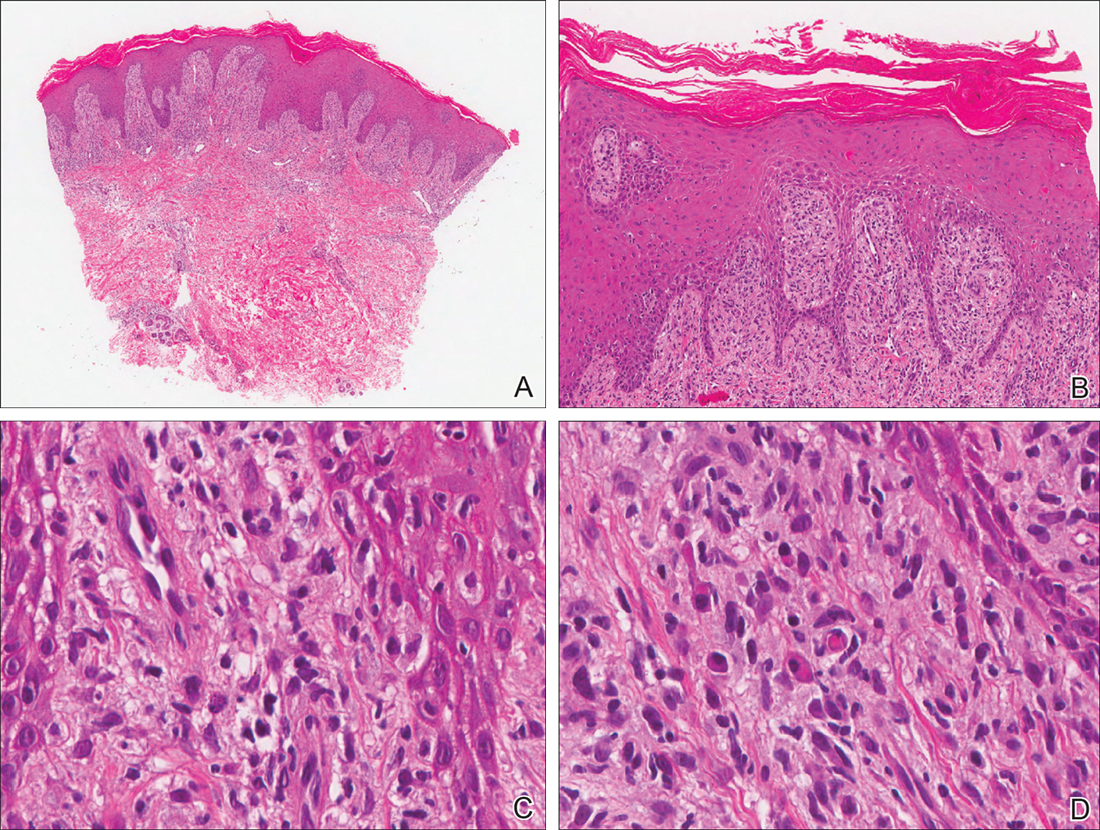

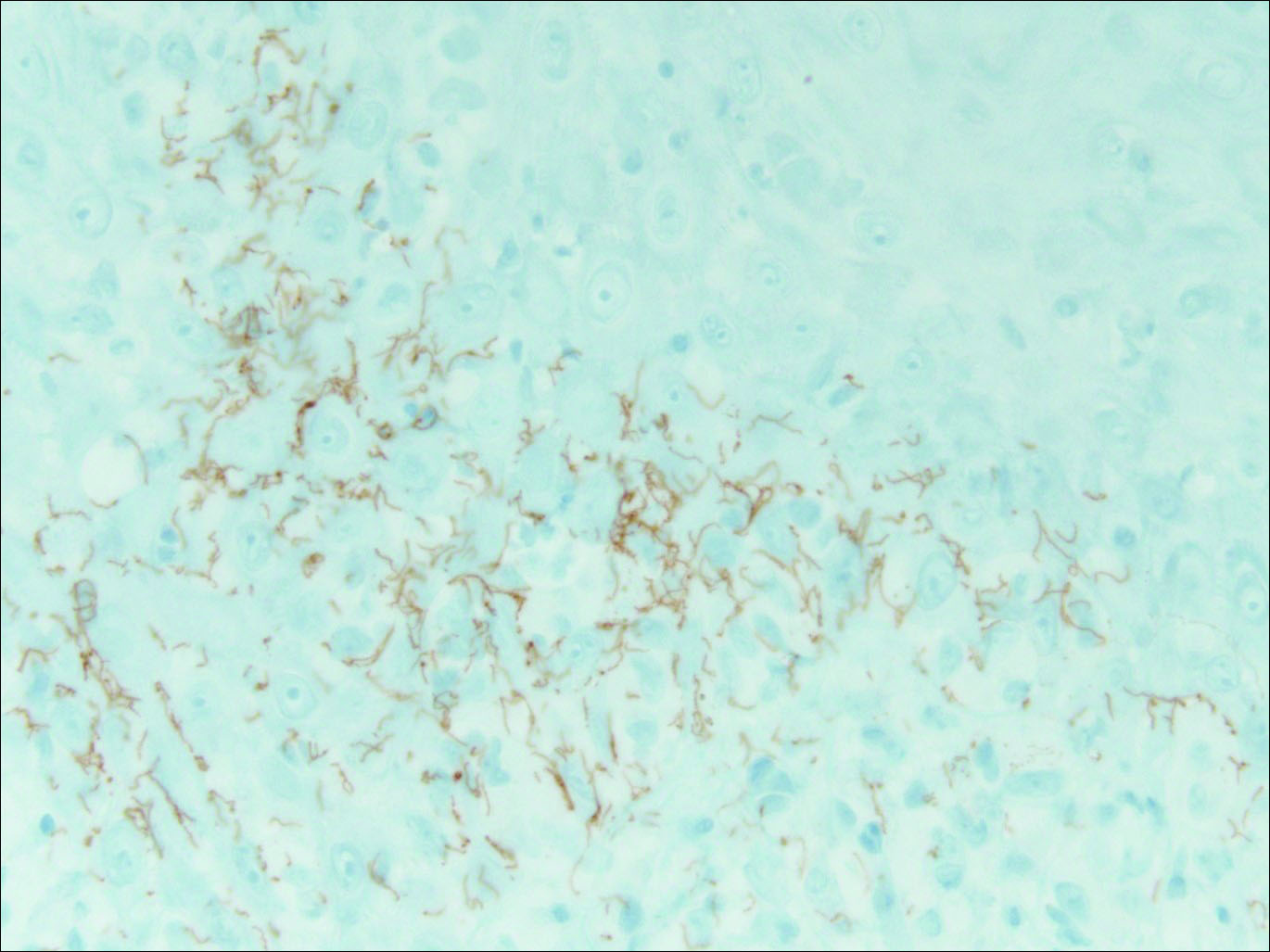

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Syphilis, known as the great mimicker, has a wide-ranging clinical and histologic presentation. There can be overlapping features with many of the entities included in the differential diagnoses. As our patient exemplifies, clinicians and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion, and any concerning features should lead to a more in-depth patient history, spirochete stains, and serologic testing.

Our patient was seen by several dermatologists over the course of 2 years and therapy with topical steroids failed. He was eager to pursue more aggressive therapy with methotrexate, and a punch biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of psoriasis prior to initiating treatment. Hematoxylin and eosin staining results on low power can be seen in Figure 1A. Medium-power view demonstrated vacuolar interface dermatitis (Figure 1B) with psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with slender elongation of rete ridges; neutrophils in the stratum corneum; endothelial cell swelling (Figure 1C); and mixed infiltrate with high plasma cells (Figure 1D), lymphocytes, and histiocytes. Although the biopsy results were psoriasiform, there was high suspicion for syphilis in this case. Additional staining for spirochetes was performed with syphilis immunohistochemical stain1 (Figure 2), which revealed spirochetes present on the patient's biopsy, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis. Warthin-Starry stain also can be performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Based on histologic features, the differential diagnosis includes psoriasis vulgaris, eczema, lichen planus, or lichenoid drug eruption. Psoriasis vulgaris displays regular psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with hypergranulosis and confluent parakeratosis. The elongated rete pegs are broad rather than slender.2 Neutrophils are present in the stratum corneum. In contrast, eczematous dermatitis is characterized by epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils. Lichen planus classically displays a brisk bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate that closely abuts or obscures the dermoepidermal junction. Parakeratosis, neutrophils, and eosinophils should be absent. The rete pegs taper to a point, similar to a sawtooth, while they are long and slender with syphilis, similar to an ice pick. Although lichenoid drug eruption presents with interface dermatitis, parakeratosis, and eosinophils, the epidermis is hyperplastic without the slender elongation of rete pegs seen in syphilis.

Further workup with serologic testing demonstrated that the patient had a syphilis IgG titer of greater than 8.0 (reactive, >6.0), indicating the patient had been infected.3 Reactive syphilis IgG, a specific treponemal test, should be followed with a nontreponemal assay of either rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or VDRL test to confirm disease activity, according to recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 which represents a change to the traditional algorithm that called for screening with a nontreponemal test and confirming with a specific treponemal test. The patient had a positive RPR and quantitative RPR titer was found as 1:2048, indicating that syphilis was active or recently treated. Testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) revealed a quantitative RNA polymerase chain reaction of 145,000 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 18 cells/µL (reference range, 533-1674 cells/µL).

The patient initially was treated for latent syphilis with 3 doses of intramuscular penicillin G benzathine 2.4 million U once weekly for 3 weeks. Due to his high RPR titers and low CD4 count, a lumbar puncture was later pursued, which revealed positive results from a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-VDRL test, confirming a diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Although a positive CSF-VDRL test is specific for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, the sensitivity of the CSF-VDRL test against clinical diagnosis is only 30% to 70%.5 Intravenous aqueous penicillin G 4 million U every 4 hours was started for 14 days for neurosyphilis. One month following the completion of the intravenous penicillin, the rash completely resolved. The patient was in a 10-year monogamous relationship with a man and did not use condoms. Typically, signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis begin 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of a chancre. However, the classic chancre of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men may go unnoticed in those who may not be able to see anal lesions.6 Also, infection with syphilis increases the likelihood of acquiring and transmitting HIV. All patients diagnosed with syphilis should have additional testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.

For patients with a history of thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet resistant to topical steroid therapy, dermatologists should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

- Toby M, White J, Van der Walt J. A new test for an old foe... spirochaete immunostaining in the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89:391.

- Nazzaro G, Boneschi V, Coggi A, et al. Syphilis with a lichen planus-like pattern (hypertrophic syphilis). J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:805-807.

- Yen-Lieberman B, Daniel J, Means C, et al. Identification of false-positive syphilis antibody results using a semiquantitative algorithm. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18:1038-1040.

- Pope V. Use of syphilis test to screen for syphilis. Infect Med. 2004;21:399-404.

- Larsen S, Kraus S, Whittington W. Diagnostic tests. In: Larsen SA, Hunter E, Kraus S, eds. A Manual of Tests for Syphilis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1990:2-26.

- Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290:1510-1514.

A 34-year-old man presented with thick scaly plaques on the wrists, knees, and feet of 2 years' duration. He had seen several dermatologists, and despite the use of topical steroids, he had no improvement.

Benign Lesion on the Posterior Aspect of the Neck

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

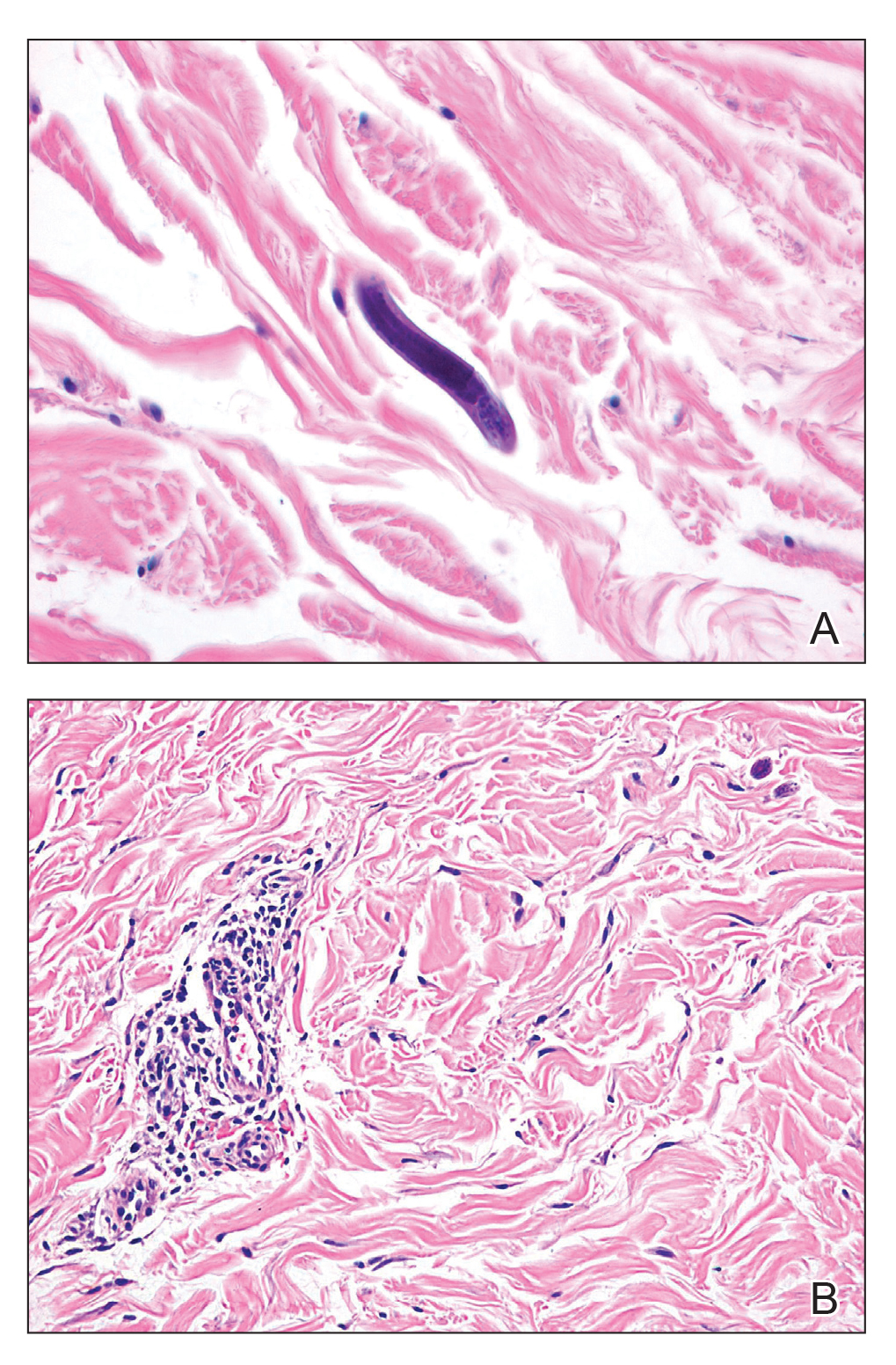

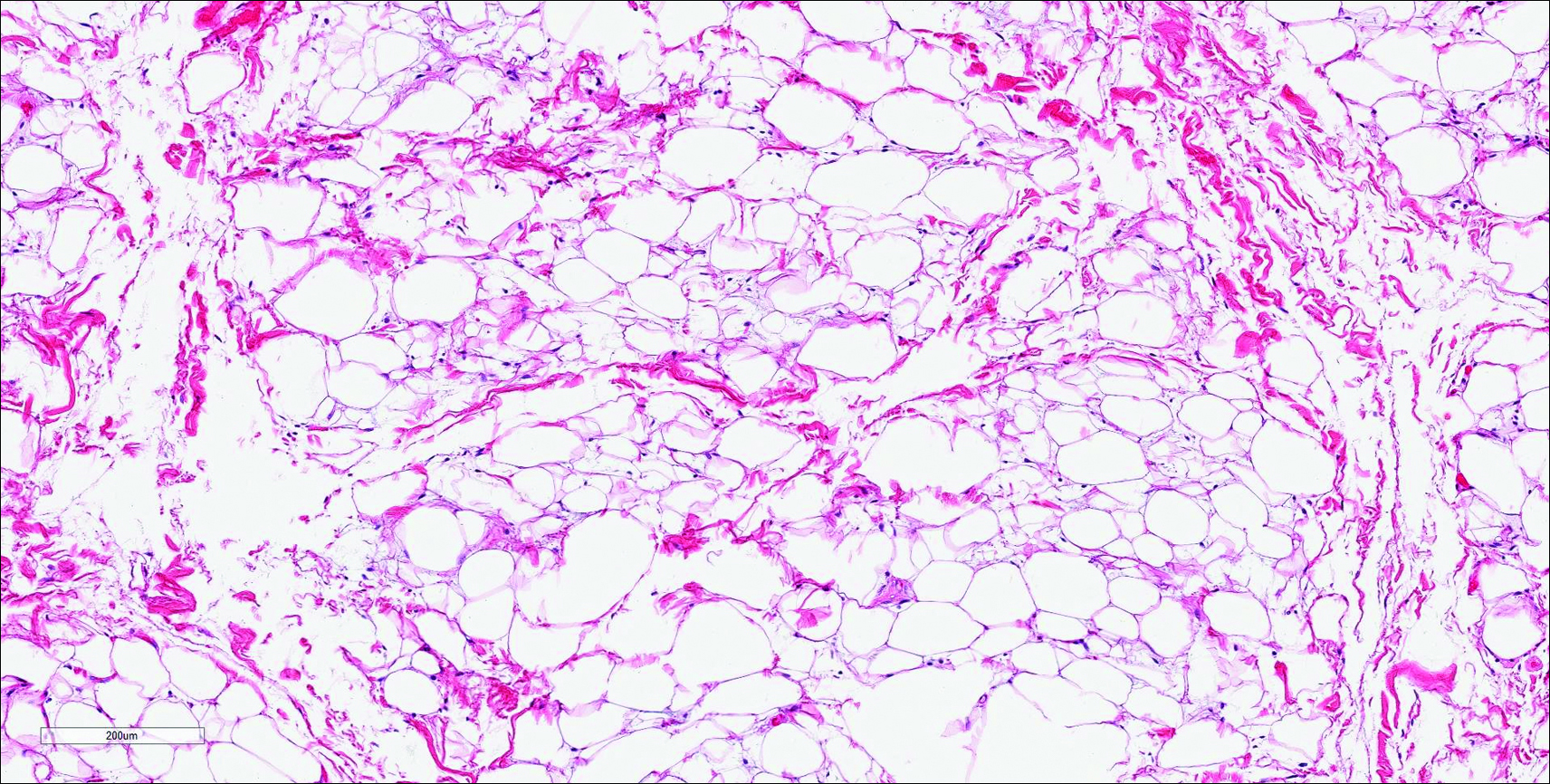

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

Nuchal-Type Fibroma

Nuchal-type fibroma (NTF) is a rare benign proliferation of the dermis and subcutis associated with diabetes mellitus and Gardner syndrome.1,2 Forty-four percent of patients with NTF have diabetes mellitus.2 The posterior aspect of the neck is the most frequently affected site, but lesions also may present on the upper back, lumbosacral area, buttocks, and face. Physical examination generally reveals an indurated, asymptomatic, ill-defined, 3-cm or smaller nodule that is hard and white, unencapsulated, and poorly circumscribed.

Histopathologic examination of NTF typically reveals a nodular paucicellular proliferation of thick collagen bundles with inconspicuous fibroblasts, radiation of collagenous septa into the subcutaneous fat, and entrapment of mature adipose tissue and small nerves (quiz image A). Collagen bundles are thickened with entrapment of adipose tissue without increased cellularity (quiz image B). S-100 staining can show the entrapped nerves.

Similar to NTF, sclerotic fibroma is a firm dermal nodule with histologic examination usually demonstrating a paucicellular collagenous tumor. In sclerotic fibromas, the collagen pattern resembles Vincent van Gogh’s painting “The Starry Night” and may be a marker for Cowden disease (Figure 1).3 Solitary fibrous tumors are distinguished by more hypercellular areas, patternless pattern, and staghorn-shaped blood vessels (Figure 2).4 Spindle cell lipoma classically demonstrates a mixture of mature adipocytes and bland spindle cells in a mucinous or fibrous background with thick collagen bundles with no storiform pattern (Figure 3). Some variants of spindle cell lipoma have minimal or no fat.5 All of these conditions have positive immunohistochemical staining for CD34.

However, dermatofibroma is CD34‒. Dermatofibroma is characterized by an interstitial spindle cell proliferation with a loose storiform pattern, collagen trapping at the outer edges of the tumor, overlying platelike acanthosis, and sometimes follicular induction (Figure 4).

Nuchal-type fibroma also can resemble scleredema. Both lesions can show increased and thickened collagen bundles without notable fibroblast proliferation; the difference is the occurrence of mucin in scleredema. However, incases of late-stage scleredema, mucin is not always demonstrated. Therefore, one can conclude that histologically NTF is closely associated with late-stage scleredema.6

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

- Dawes LC, La Hei ER, Tobias V, et al. Nuchal fibroma should be recognized as a new extracolonic manifestation of Gardner-variant familial adenomatous polyposis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2000;70:824-826.

- Michal M, Fetsch JF, Hes O, et al. Nuchal-type fibroma: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Cancer. 1999;85:156-163.

- Pernet C, Durand L, Bessis D, et al. Solitary sclerotic fibroma of the skin: a possible clue for Cowden syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:278-279.

- Omori Y, Saeki H, Ito K, et al. Solitary fibrous tumour of the scalp. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:539-541.

- Billings SD, Folpe AL. Diagnostically challenging spindle cell lipomas: a report of 34 “low-fat” and “fat-free” variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:437-442.

- Banney LA, Weedon D, Muir JB. Nuchal fibroma associated with scleredema, diabetes mellitus and organic solvent exposure. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:39-41.

The best diagnosis is:

a. dermatofibroma

b. nuchal-type fibroma

c. sclerotic fibroma

d. solitary fibrous tumor

e. spindle cell lipoma

Continue to the next page for the diagnosis >>